Abstract

Searchable Encryption (SE) schemes enable data users to securely search over outsourced encrypted data stored in the cloud. To support fine-grained access control, Attribute-Based Encryption with Keyword Search (ABKS) extends SE by associating access policies with user attributes. However, existing ABKS schemes often suffer from limited security and functionality, such as lack of verifiability, vulnerability to collusion, and insider keyword-guessing attacks (IKGA), or inefficiency in multi-authority and post-quantum settings, restricting their practical deployment in real-world distributed systems. In this paper, we propose a verifiable ciphertext-policy multi-authority ABKS (MA-CP-ABKS) scheme based on the Module Learning with Errors (MLWE) problem, which provides post-quantum security, verifiability, and resistance to both collusion and IKGA. Moreover, the proposed scheme supports multi-keyword searchability and forward security, enabling secure and efficient keyword search in dynamic environments. We formally prove the correctness, verifiability, completeness, and security of the scheme under the MLWE assumption against selective chosen-keyword attacks (SCKA) in the standard model and IKGA in the random oracle model. The scheme also maintains efficient computation and manageable communication overhead. Implementation results confirm its practical performance, demonstrating that the proposed MA-CP-ABKS scheme offers a secure, verifiable, and efficient solution for multi-organizational cloud environments.

1. Introduction

With the exponential growth of data and the increasing complexity of its storage and management, outsourcing data to cloud servers (CS) has become a common practice among data owners (DO). To preserve confidentiality, data is typically encrypted before outsourcing. However, this encryption complicates efficient retrieval by data users (DU). Searchable encryption (SE) schemes have been proposed to enable secure search operations over encrypted data. These schemes are generally classified into two main categories: symmetric and asymmetric types [1,2]. In symmetric SE, the DO and DU share a common secret key, requiring a secure channel for key exchange. This limitation has spurred the development of asymmetric schemes, such as public-key encryption with keyword search (PEKS), in which the DO encrypts data using the DU’s public key and the DU performs searches using a private key. However, PEKS schemes become inefficient in multi-user settings, as they require encrypting data for each DU individually under individual public keys. To achieve fine-grained access to encrypted data in cloud environments, Attribute-based Encryption with Keyword Search (ABKS) schemes have been introduced [3]. These schemes are categorized into Key-Policy (KP-ABKS) and Ciphertext-Policy (CP-ABKS). Further enhancements have introduced key features such as multi-authority support [4], collusion resistance [5], forward security [6], multi-keyword search, and resistance to insider keyword guessing attacks (IKGA) [7].

In Multi-Authority ABKS (MA-ABKS), attribute management is distributed across independent authorities, each handling a specific subset of attributes. This decentralized structure enhances scalability, fault tolerance, and DU privacy, making it ideal for multi-organizational environments like cross-institutional healthcare systems.

A practical application of MA-ABKS is the secure sharing of sensitive medical data across healthcare institutions, including hospitals, clinics, and research centers. In such settings, patient records, such as medical histories or laboratory results, must be accessible only to authorized personnel with specific attributes, such as medical specialization or institutional affiliation. MA-ABKS provides fine-grained attribute-based access control while preserving DU privacy, as it does not reveal DU identities. It also allows authorized DUs to perform keyword-based searches over encrypted medical data, ensuring that only legitimate DUs can retrieve relevant information. Moreover, each institution can operate as an independent attribute authority, managing its own attribute domain, thereby reducing dependence on a single trusted authority (TA) and enhancing both scalability and privacy. These features make MA-ABKS particularly suitable for distributed, multi-organizational environments where data confidentiality and controlled access are essential.

Quantum computing threatens classical schemes based on the discrete logarithm problem via Shor’s algorithm [8]. Consequently, lattice-based cryptography has emerged as a promising foundation for post-quantum secure designs. The first lattice-based ABKS scheme was proposed in [9], followed by works incorporating multi-authority support and collusion resistance [10], and multi-keyword search with IKGA resistance [11].

Despite these advancements, combining these features in a lattice-based multi-authority CP-ABKS (MA-CP-ABKS) framework remains a challenge. Specifically, achieving verifiability, full security against collusion and IKGA, forward security, and efficient multi-keyword search simultaneously has yet to be addressed.

This work aims to provide a secure, efficient, and verifiable MA-CP-ABKS solution for distributed cloud environments involving multiple independent organizations.

1.1. Our Contribution

In this paper, we propose a lattice-based MA-CP-ABKS scheme based on the Module-LWE (MLWE) problem, improving efficiency. The scheme enables a DU to generate a search trapdoor through interaction with the TA. We integrate verifiability, completeness, and collusion resistance into the ABKS framework. Inspired by [12], the scheme also supports multi-keyword search and introduces methods for forward security and IKGA security. Formal security proofs are provided against Selective Chosen Keyword Attacks (SCKA) and IKGA in the standard and Random Oracle (RO) models, respectively.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Lattice-based MA-CP-ABKS scheme: We propose a novel scheme based on the MLWE problem, enhancing both efficiency and security.

- Verifiability and completeness: We achieve verifiability and completeness by embedding proof components into the searchable ciphertext, derived from the keyword, the DO’s private key, and a shared secret between the DO and authorized DUs.

- Collusion resistance: We prevent collusion by binding each DU’s trapdoor to its global identity (GID), ensuring that trapdoors cannot be combined to gain unauthorized search capabilities.

- Post-quantum security: We prove that the scheme is secure against SCKA through a formal reduction from the MLWE problem.

- TA Dependency: As the DU needs a private key for trapdoor generation and does not receive the key, each DU must interact with the TA for each trapdoor.

- Multi-keyword search: We propose a method enabling DUs to perform simultaneous multi-keyword searches.

- Forward security: We propose a method to integrate forward security into our scheme.

- IKGA resistance: We enhance IKGA resistance by incorporating the DO’s private key into keyword encryption and the DO’s public key into trapdoor generation.

- Efficiency: We leverage the structured properties of the MLWE problem to achieve efficient computation. The implementation results confirm practical execution times and manageable communication overhead under realistic parameter settings.

1.2. Roadmap

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work. Section 3 presents the problem statement. Section 4 introduces the required definitions and concepts. In Section 5, we propose a verifiable ABKS scheme based on the MLWE problem, analyzing its correctness, verifiability, completeness, and collusion resistance, along with a formal security proof. We extend the scheme to support multi-keyword search and IKGA resistance. Section 6 discusses implementation results and efficiency evaluation. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and suggests future research directions.

2. Related Work

Many ABKS schemes have been proposed, incorporating features such as verifiability [13,14], revocation [4,13,15,16], multi-authority support [4,5,17], multi-keyword search [13,18], forward security [6], dual policies [19], policy hiding [20], and anonymity [21]. Since centralized TAs generate key pairs for each DU, creating a single point of failure, MA-ABKS schemes have been proposed to address this issue [4,5,10,16,22].

When the CS behaves maliciously, it may return incorrect or incomplete results. Verifiable ABKS schemes [14,23,24] address this by embedding proofs generated by the DO, enabling DUs to verify result correctness. Forward-secure SE [6,25,26] further protects past data by periodically updating keys, limiting the impact of key exposure.

The KGA, introduced by Byun et al. [27], enables adversaries to identify searched keywords by testing encrypted candidates against a trapdoor. To mitigate this threat, several countermeasures have been proposed [28,29], with the most effective ensuring that the encrypted keyword depends on the DO’s private key [29,30,31].

Collusion attacks are another threat to ABKS schemes, where multiple DUs collaborate maliciously to gain unauthorized access. Such attacks are prevented by deriving DUs’ specific cryptographic information from their unique identifiers, ensuring that one DU’s information cannot be utilized by others and thus effectively preventing collusion.

With the emergence of quantum computers, classical cryptographic algorithms based on the discrete logarithm problem have become vulnerable. Consequently, post-quantum cryptography has gained significant attention [8], with lattice-based cryptography standing out for its simple structure, linear computations, and provable security

The first lattice-based ABKS scheme, proposed in 2017 [9], employed multiple CS to generate partial search results that are combined to obtain the final output. However, this approach suffers from low efficiency due to the computation being distributed across multiple CSs. In 2019, a lattice-based ABKS scheme [32] combined attribute-based encryption (ABE) with PEKS, where the DU must contact the TA to obtain a trapdoor for each keyword. However, it allowed unauthorized access to encrypted documents. A lattice-based KP-ABKS scheme introduced in 2020 [33] addressed some of these issues but lacked verifiability, remained vulnerable to IKGA, and relied on the RO model. In 2021, a CP-ABKS scheme [34] was proposed using linear secret sharing (LSSS), but it lacked correctness, formal reduction from LWE to the scheme, and collusion resistance. In 2023, another KP-ABKS scheme was introduced [35]; it improved resistance to KGAs and provided a security proof in the RO model. Nevertheless, it fails to ensure correctness, often retrieving irrelevant documents. In 2024, a CP-MA-ABKS scheme [10] based on the LWE problem extended MA-ABE with searchability and revocation, allowing any DU to perform searches. In 2025, a revocable and authenticated ABKS scheme based on LWE was proposed [11], supporting multi-keyword search. The scheme has proven to be secure against CKA and IKGA in the RO model. However, it still lacks verifiability and remains vulnerable to collusion attacks, which undermines its security and applicability in multi-user scenarios.

Most existing lattice-based ABKS schemes that rely on LWE are inefficient due to high matrix dimensionality. To address this, structured variants of the LWE problem have been proposed [36,37,38]. In this work, we adopt the MLWE problem [38] aligned with the assumptions underlying the NIST-standardized Kyber scheme [39,40].

Despite advances, existing lattice-based ABKS schemes still lack key features like verifiability, forward security, IKGA and collusion resistance, and multi-keyword search. Integrating the MLWE assumption into a verifiable MA-ABKS framework with strong security guarantees remains largely unexplored. This work addresses these gaps, advancing practical post-quantum searchable encryption for distributed cloud environments.

3. Problem Statement

3.1. ABKS Scheme

A CP-ABKS scheme consists of five algorithms [23,24]:

- 1.

- : The TA takes a security parameter as input and outputs the public parameters and a master secret key .

- 2.

- : The TA uses the master secret key and the DU’s Attribute set to generate the DU’s private key , which is then sent to the DU.

- 3.

- : The DO uses access policy to generate an ABKS corresponding to the keyword , which is uploaded to the CS.

- 4.

- : The DU uses to generate a trapdoor for the searched keyword , which is then sent to the CS.

- 5.

- : The CS verifies . If this is the case, using the trapdoor for each encrypted keyword , the CS checks if . If so, it returns 1 and sends the encrypted documents corresponding to the ABKS that passed the search to the DU.

In MA-ABKS schemes, each authority manages a subset of attributes and generates corresponding public and private keys within its domain.

3.1.1. Correctness

The correctness of a CP-ABKS scheme is defined as follows [23]:

Given , , , , the search algorithm outputs 1 when and , and 0 otherwise.

3.1.2. Security Against SCKA

The security of a CP-ABKS scheme is defined through the SCKA game between a challenger and an adversary , as follows [23]:

- 1.

- outputs a challenge access policy

- 2.

- runs the algorithm, obtaining and , and sends to .

- 3.

- adaptively queries the following oracles a polynomial number of times.

- (a)

- Oracle: Given attribute set , if , the oracle aborts; otherwise, it returns to .

- (b)

- Oracle: Given , it returns . If , the keyword is added to .

- 4.

- outputs the challenge keyword such that .

- 5.

- randomly selects and sends the ciphertext, either random if or if , to .

- 6.

- can query both oracles, but cannot be queried if .

- 7.

- Finally, returns a bit . The adversary wins if , distinguishing the challenge ciphertext from random one.

The adversary’s advantage is defined as .

An ABKS scheme achieves SCKA security if, for every probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) adversary , the advantage is negligible in the security parameter .

3.2. Verifiability

In searchable encryption, a malicious CS may return incomplete or tampered search results. To ensure integrity, the DU verifies that all retrieved documents were encrypted by the DO and that no documents are omitted. The DO generates a proof for the presence of each keyword in the documents using its private key. The CS returns the encrypted documents along with the proof, which the DU verifies before decryption.

We propose two algorithms, and .

: The DO generates a proof for a keyword and the documents using its keys , then sends it to the CS.

: The DU verifies upon receiving the results. If the verification fails, the DU requests a research.

In this paper, a verification method similar to [24] is adopted to ensure verifiability.

3.3. Collusion Attack

In a collusion attack, DUs may share private keys to gain unauthorized access. In CP-ABKS, this occurs when DUs combine key components to emulate another DU with a different attribute set, deceiving the system into granting access to restricted documents.

To prevent collusion, each private key component must be cryptographically bound to the DU’s global identifier (GID), preventing independent use. This method, introduced in an ABE scheme [41], can be adapted for ABKS schemes to ensure collusion resistance.

In lattice-based collusion-resistant ABKS, the private key, derived from the master secret key, serves as the basis for trapdoor generation. This ensures that only authorized entities can generate valid trapdoors. A legitimate DU can solve a hard lattice problem, proving key possession and enabling trapdoor generation. Since the private key is GID-bound, the corresponding lattice is also GID-dependent. To ensure compatibility with trapdoors, the DO must generate distinct encrypted keywords for each GID, affecting the multi-user functionality of ABKS. To preserve collusion-resistance, the DU must interact with the TA for each trapdoor generation. The TA, using the master secret key as a good lattice basis, solves a preimage-finding problem for a function of the DU’s GID.

3.4. Keyword Guessing Attack

The KGA, first identified by Byun et al. in 2006 [27], is a common threat in asymmetric SE, where an adversary, often an insider like the CS, tests candidate keywords against the trapdoor. The IKGA is more severe, as it exploits both trapdoors and a known keyword set . In this attack, the adversary encrypts each keyword in with the public key, creating a keyword–ciphertext mapping. Upon receiving a trapdoor, the adversary runs the search algorithm on each mapping entry. If a match is found, the queried keyword is revealed. Hence, with access to both the trapdoor and the keyword space, the adversary can recover the searched term through exhaustive trials. To mitigate IKGA, countermeasures such as covert keyword-to-index mappings [28], authenticated searchable encryption, and fuzzy keyword search mechanisms have been proposed. Among these, encrypting keywords with the DO’s private key is the most effective [29], as it prevents adversaries from constructing a keyword–ciphertext dictionary and ensures only keywords encrypted by the DO match trapdoors generated with the corresponding public key.

The security of an ABKS scheme against IKGA is modeled as a game between a challenger and an adversary , as described in the following steps [27]:

- 1.

- outputs the attribute set

- 2.

- runs the algorithm, obtaining and , and sends to .

- 3.

- can adaptively query the following oracles a polynomial number of times:

- (a)

- Oracle: Given access policy the oracle returns . If , is added to .

- (b)

- Oracle: Given , it returns .

- 4.

- outputs the challenge keyword such that .

- 5.

- selects a random bit . If , samples a trapdoor randomly. If , computes the trapdoor as . sends the trapdoor to .

- 6.

- may query both oracles, except that for any satisfying , cannot be queried to the ABKS Oracle.

- 7.

- returns a bit . wins if .

The advantage of adversary is defined as .

An ABKS scheme is secure against IKGA if, for every PPT adversary , the advantage is negligible in the security parameter .

In this work, we adopt a strategy similar to [30,31], with improved efficiency.

3.5. Multi-Keyword Search

In conventional SE, a DU generates separate trapdoors for each keyword, causing inefficiency in multi-keyword queries. To address this, multi-keyword SE schemes allow the DU to search a set of keywords with a single trapdoor, enabling the CS to retrieve all matching documents. Common query types include conjunctive (AND) and disjunctive (OR) searches. Advanced schemes support arbitrary Boolean expressions.

The proposed scheme integrates multi-keyword search as introduced in [12].

3.6. Forward Security

In some SE schemes, trapdoors valid for one time interval may be misused across others. Forward-secure SE mitigates this by binding the private keys and the trapdoors to specific time intervals, ensuring validity only within designated periods.

The proposed scheme adopts this mechanism to enhance long-term key security.

4. Preliminaries

This section presents the fundamental definitions and concepts essential for the development of this paper.

4.1. Notation

In this section, vectors and polynomials are denoted by lowercase letters, while matrices are represented by uppercase letters. The finite field of integers modulo a prime is denoted by , and denotes the polynomials with coefficients in . The notation refers to the infinity norm of a polynomial , defined as the largest coefficient magnitude, and denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to . The distribution represents a discrete Gaussian distribution over with zero mean and standard deviation . A function is negligible if there exists an integer such that for all , it is smaller than the inverse of any polynomial in . Let be a distribution over ; the notation denotes sampling a random matrix from with independent entries. Similarly, denotes a uniform sampling from . The notation indicates column-wise concatenation of and . For an integer , . For the two functions and , means there exist constants and such that for all , and if .

4.2. Lattice

Definition 1

(Lattice [42]). Let be linearly independent vectors. The m-dimensional lattice generated by the basis is defined as:

Definition 2

(q-ary lattices [43]). Let be an integer, be a matrix, and be a vector. The q-ary lattices are defined as follows:

4.3. Gaussian Distribution

Definition 3

(Gaussian distribution [44]). Let , and . The discrete Gaussian distribution over a lattice , denoted as , is defined as follows:

4.4. Module-LWE

Let be a prime and a power of 2. Define the rings and , where is a cyclotomic polynomial of order . We introduce two problems, Module Short Integer Solution (MSIS) and MLWE. Here, is the module rank, and is the module lattice dimension. Their hardness has been established through worst-case to average-case reduction on module lattices [38,45].

Definition 4

(MSIS problem [46]). Given a matrix and a bound , the goal is to find a vector such that and .

Definition 5

(MLWE problem [46]). Let and , where and . The decision MLWE problem is to distinguish between pairs , generated as above and those drawn uniformly from .

Trapdoors for MLWE

We present two trapdoor algorithms for MLWE-based schemes:

- 1.

- : Given integers , , , , this algorithm takes a tag as input. It outputs a matrix and its trapdoor , where is indistinguishable from the a uniformly random matrix and is sampled from the discrete Gaussian distribution , ensuring a small norm [46,47,48]. If not specified, assume .

- 2.

- : Given a trapdoor for matrix with tag , vector and Gaussian parameters and , the algorithm outputs a vector , such that and [46].To guarantee correctness and security, the parameters must satisfy [46]:where is the spectral norm of , and is the smoothing parameter.

4.5. Linear Secret Sharing Scheme

A secret sharing scheme over , with users (or attributes) , is linear [49] if: (1) Each user’s share is a vector over . (2) There is a share-generating matrix , where each row is labeled by a mapping , from to .

To share a secret , the dealer forms with random . Each share is the row of . For an authorized set of DUs (or attributes), define . The vector lies in the span of the rows of indexed by , so there exist coefficients such that, . These coefficients can be computed in polynomial time with respect to the size of [49].

Access structures are represented as monotonic Boolean formulas with the upward-closure property, where any superset of an authorized set is also authorized. To construct an LSSS share-generating matrix, the formula is converted into a tree with leaf nodes for attributes and internal nodes for AND/OR gates [41]. The construction is as follows:

- 1.

- The root node is initialized with the label vector , and the counter .

- 2.

- Each internal node derives its label from its parent based on the Boolean gate:

- OR gate: Children inherit the parent’s label and the counter remains unchanged.

- AND gate: For a label as a parent label, zeros are appended to to match the length . One child is assigned the label , and the other is labeled , where is a zero vector of length . The counter is incremented by one. Notably, the sum of these vectors is , preserving linear consistency.

- 3.

- This process continues recursively until all leaf nodes are labeled.

The rows of matrix are obtained by zero-padding the leaf label vectors to make them equal in length, forming the final access policy representation.

In this work, we adopt the LSSS construction of [41] for monotone access structures consisting of AND and OR gates, where .

5. Our Scheme

In this section, we propose a verifiable CP-MA-ABKS scheme based on MLWE problem. We introduce two MLWE-based trapdoor algorithms, followed by the CP-MA-ABKS construction, formal proofs of correctness, verifiability, and collusion resistance. Security against SCKA is proven via a reduction from the MLWE problem in the standard model. The scheme is then extended to support multi-keyword queries and resist IKGA.

5.1. Two Trapdoor Functions for MLWE

Let be a prime modulus and a power of 2. Define the rings and , where is the cyclotomic polynomial of order . Let denote the module rank so that the underlying module lattice has dimension . Given integers , , , and standard deviations of the corresponding discrete Gaussian distributions, and a trapdoor generation algorithm , we present and algorithms, in accordance with the methodology proposed in [50], as follows:

- 1.

- : The algorithm first samples , then computes and finally outputs . So, we have . Moreover, by Theorem 3 and 4 in [51], the distribution of is statistically close to .

- 2.

- : Let . The algorithm first constructs a matrix , containing linearly independent short vectors from following [50]. It then computes , where the distribution of is statistically close to and [50]. According to [46]:where is the spectral norm of , and is the smoothing parameter.

5.2. MLWE-Based VABKS Scheme

In this section, we present our proposed CP-ABKS scheme. Let and , where is a prime and a power of two. Let with . The discrete Gaussian distribution samples coefficients independently with standard deviation and rounds to the nearest integer. Let be the universal attribute set. We assume a hash function that outputs values uniformly distributed over . Additionally, we assume hash functions: and are one-way and collision-resistant. The proposed scheme is described as follows.

- 1.

- : Given the security parameter , each TA generates the public parameters and the master secret key for its assigned attributes and publishes .

- 2.

- : Given the security parameter , the TA generates the DO’s key pair and sends them to the DO:

- 3.

- : To encrypt a keyword under policy , the DO first converts into a share-generating matrix using an LSSS [49]. For each , the DO samples and , and computes:For any authorized set , there exists a set of coefficients , where such that and .

The DO computes , where denotes the component of . Next, the DO samples and . It then computes the encrypted keyword , as follows, and sends and to the CS:

- 4.

- : To prove the existence of a keyword in the corresponding documents , the DO concatenates with and computes , where . Then, the DO, using its key pair, computes the proof , such that . Finally, for each , the DO sends , and to the CS publicly.

- 5.

- : To search for a keyword , the DU computes . The DU then submits and its attribute set to the corresponding TAs. Each TA, using , , and the master secret key , computes the trapdoor , satisfying , as follows:The generated trapdoor is sent securely to the DU and then forwarded with to the CS.

- 6.

- : Upon receiving from the DU, and given , attribute set and access policy , the CS first verifies whether satisfies . If so, it computes and determines coefficients such that , where is the row of . For each , the CS computes:If for all , the search algorithm outputs 1, indicating a keyword match. The CS then sends the associated encrypted documents and verification proof to the DU.

- 7.

- : Upon receiving the encrypted documents , with the proof , the DU first verifies that holds. If satisfied, it decrypts to recover and computes . The verification succeeds if . Otherwise, the DU rejects the results and may reissue the query.

If the CS is assumed honest, the DO’s key generation, proof generation, and verification algorithm in steps 2, 4, and 7, respectively, may be omitted from the initial analysis.

5.2.1. Correctness

We analyze the correctness for , considering two cases based on whether the attribute set satisfies the access policy (i.e., ) or not.

- Case 1: and

- Case 2: and

To state Theorem 1, we first establish Lemmas 1 and 2, presented below.

Lemma 1.

Let and be independent, where is an arbitrary distribution. Then is uniformly distributed over .

Proof.

For any , we have:

□

Lemma 2.

Let and be independent, where is an arbitrary distribution. Then is uniformly distributed over .

Proof.

For any we have:

Let and with . Hence, there exists such that . Let denote the event that for all . Conditioning on this event, we obtain:

□

Theorem 1.

Let and be independent, where is an arbitrary distribution. Then, the coefficients of are uniformly distributed over .

Proof.

Let and , so that . Since , there exists with . Since are independent for , it suffices to show that has uniformly distributed coefficients. By Lemma 1, then also has uniformly distributed coefficients. Assume and . By defining and , we obtain:

Since is uniformly distributed and , Lemma 2 implies that is uniformly distributed over . Thus, by Lemma 1, has uniformly distributed coefficients. □

5.2.2. Verifiability and Completeness

We show that the scheme satisfies completeness and verifiability: Valid proofs are accepted by the algorithm with overwhelming probability, while there is a negligible probability that any PPT adversary could forge or reuse a valid proof.

When the DU searches for a keyword and receives from the CS, it decrypts , computes , and checks whether and . These conditions hold with overwhelming probability for correct documents, since .

Assume a PPT adversary forges a valid proof for a keyword and document set , such that verification succeeds with non-negligible probability. Since satisfies and , the adversary finds a short preimage of , contradicting the MSIS hardness assumption [38]. Hence, no PPT adversary can forge a valid proof, except with negligible probability.

If the CS reuses a valid proof for a different keyword or different document set , it must hold that . This contradicts the collision resistance of and . Thus, each proof is bound to its keyword and document set and cannot be reused.

The one-way nature of ensures that revealing does not expose or the documents containing the keyword from . Similarly, even if the DU discloses , , and the encrypted documents to prove the CS misbehavior, the one-way nature of prevents the recovery of . Moreover, since is known only to the DO and authorized DUs, an attacker, even with access to the corresponding encrypted documents and , cannot determine the underlying searched keyword.

Remark 1.

In the proposed verifiability framework, adding or deleting a file requires updating only the proofs linked to its keywords. To enable parallelization, the scheme generates separate proofs for each keyword-file pair. Although this increases the total number of verifiability proofs, completeness proofs remain unaffected and each verifiability proof can be generated in parallel.

5.2.3. Resistance to Collusion Attack

In this section, we demonstrate that the proposed scheme is collusion-resistant.

Suppose Alice and Bob collude to access documents they are not individually authorized to view. Alice holds the attribute set and identifier , while Bob holds and . Each independently requests a trapdoor for from TAs:

Now, they try to impersonate Carl by forging a trapdoor for an authorized attribute set , where , , and . They compute a collusion trapdoor for , as , where . Now, this trapdoor along with is sent to the CS. Upon receipt, the CS first verifies whether is authorized. Since is valid, there exists an index set , and coefficients such that , where denotes the row of the matrix . Assume with , and . The CS then proceeds with the search as follows:

Since is valid and partitioned into two disjoint subsets and , it follows that:

By substituting the above expression into the original equation, we obtain:

Since is unauthorized, any linear combinations of for satisfies . By Theorem 1, the coefficients of are uniformly distributed, since has uniform distribution. Therefore, by Lemma 1 and the independence of terms, the coefficients of are uniformly distributed.

Therefore, the probability that for all is , which is negligible in when . Hence, in the presence of collusion, the search algorithm outputs zero with overwhelming probability.

5.2.4. SCKA Security

In this section, we prove SCKA security in the standard model under the MLWE assumption. As each DU interacts with TAs to obtain a trapdoor for a specific keyword, the adversary is restricted to trapdoor queries for authorized attributes and that keyword.

Definition 6

(Multi-MLWE Problem). Given samples for and , where , and are computed as , the Multi-MLWE problem is to distinguish between these two distributions with a non-negligible advantage.

The Multi-MLWE problem directly reduces from the standard MLWE problem.

Theorem 2.

The proposed scheme achieves indistinguishability-based security against SCKA in the standard model, assuming the hardness of the Multi-MLWE problem.

Proof.

Here, is the probability of not aborting the challenge. Hence, any PPT adversary breaking semantic security of the scheme with non-negligible advantage implies a distinguisher breaking the Multi-MLWE assumption, contradicting its assumed hardness.

We define a sequence of games, each computationally indistinguishable from the previous for any PPT adversary. Let denote the adversary’s advantage in Game . The games are defined as follows:

Game 0: This game is identical to the IKGA game. Thus: .

Game 1: This game is identical to Game 0, except , instead of chosen uniformly. By Lemma 13 in [50]: .

Game 2: This game is identical to Game 1, except and . When the adversary requests a trapdoor for and , the challenger verifies , where with denoting the abort-resistant hash functions [50]. Let . The challenger computes:

Analogous to the original scheme, we also have:

The adversary keeps a of keywords associated with the attribute set , satisfying . Based on Lemma 28 in [50]: .

Game 3: This game is identical to Game 2, except that the encrypted challenge keyword is replaced with a random value, yielding: .

Reduction from Multi-MLWE: Assume a PPT adversary distinguishes Game 2 and Game 3 with a non-negligible advantage. Then, a PPT challenger can employ to distinguish Multi-MLWE samples from uniform with non-negligible advantage, contradicting the Multi-MLWE hardness assumption. The challenger proceeds as follows:

Upon receiving the samples , for , selects and sets and . It then generates and with trapdoors as in Game 2 and sends to . Then answers the trapdoor queries as in Game 2.

Upon receiving the challenge keyword from , checks and . By Lemma 27 in [50], holds with a probability of at least for fewer than queries. Subsequently, to encrypt the challenge keyword, constructs the share-generating matrix for , selects , and computes the following, where denotes the column of .

also computes the following by sampling :

then computes the values for all , , and by summing the corresponding rows, yielding:

Thus, based on the above computations, derives the encrypted challenge as follows:

Analogous to the original scheme, the following relation holds for :

Given for , we have .

- Thus, if ’s input samples follow the Multi-MLWE distribution, the adversary’s view corresponds to Game 2; otherwise, if the samples are uniform, interacts with random values as in Game 3. Therefore, sets its output to that of , i.e., . Thus:

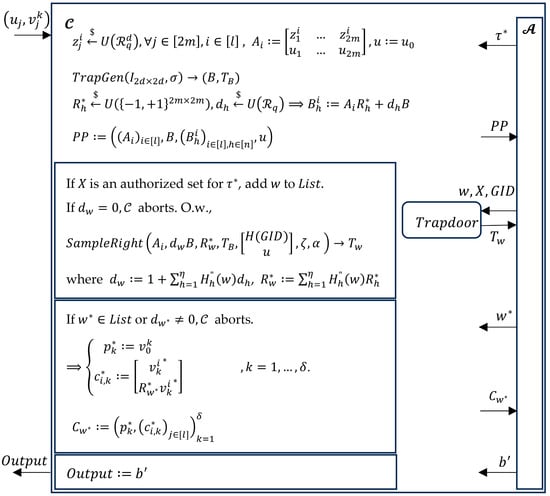

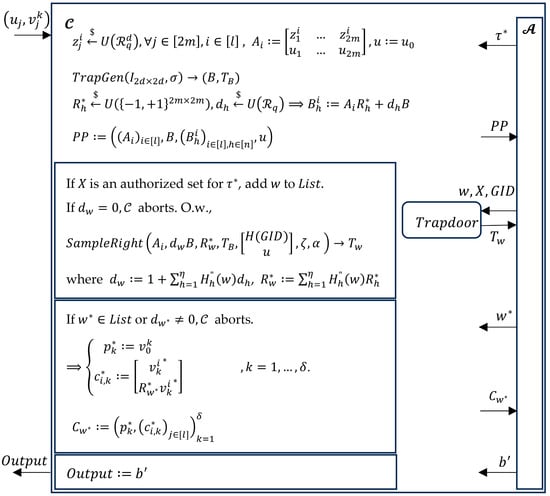

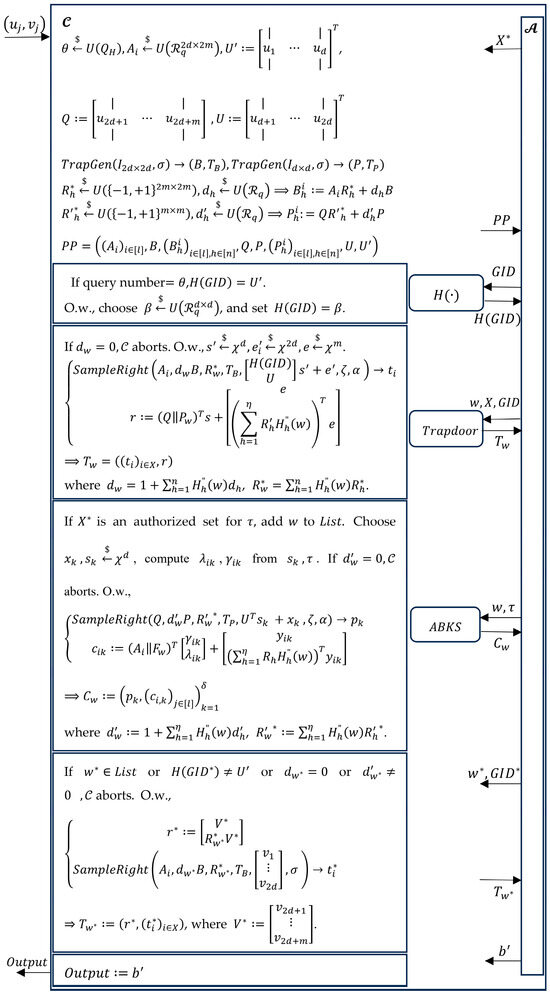

- We summarize the security proof through the security game illustrated in Figure 1.

□

Figure 1.

Semantic security against SCKA for ABKS scheme.

5.2.5. Multi-Keyword Search

In this section, we present a multi-keyword search method adapted from [12]. First, the DO encrypts each keyword of document using Step 3 from Section 5.2 (ABKS) and sends them to the CS. The DU then computes the leaf node values for each in the search policy , using Search Tree Labeling Algorithm [12]:

Search Tree Labeling Algorithm [12]: Until all leaf nodes receive label vectors :

- Assign the identity matrix to the root node.

- OR gates: Each child node inherits the parent’s label.

- AND gates: Split the parent’s label into child labels from whose sum equals the parent’s label.

Subsequently, for each , the DU computes and sends it to the TAs. Each TA computes the trapdoor components . The DU then forwards and to the CS. Upon receiving the trapdoor and accessing the encrypted keywords , the CS executes Step 6 of Section 5.2 (Search). It first checks whether the DU’s attribute set satisfies the access policy . If so, it computes coefficients , satisfying . For each keyword set matching the search policy , it computes . If for all , the search algorithm outputs 1. In this case, the correctness of the scheme is established as follows:

As shown in Section 5.2.1, Case 1, has a low norm. Hence, the search algorithm returns 1 with overwhelming probability.

If the keyword set does not satisfy , then , and so:

By Theorem 1, has uniformly distributed coefficients, since with overwhelming probability and is uniform and independent of other components. Thus, by Lemma 1, each has uniformly distributed coefficients, and the search algorithm outputs 1 with negligible probability.

The security analysis follows the same approach as the original scheme in Section 5.2.4.

5.2.6. Forward Security

To incorporate forward security into an ABKS scheme, each attribute is assigned a temporal tag specifying its validity period. When a DU requests a trapdoor, the TA verifies the attribute is valid for the given time interval. If so, the TA issues a trapdoor embedding both the attribute and its temporal tag. Simultaneously, the DO encrypts keywords under an access structure binding attributes to their temporal tags, preventing trapdoor reuse across different time intervals and ensuring temporal access control.

Alternatively, forward security can be achieved by periodically refreshing each TA’s keys via for all and at each predefined time interval. In this construction, a trapdoor generated for one time interval cannot be used for others, as encrypted keywords are bound to the public parameters and incompatible with trapdoors derived from .

5.2.7. Resistance to IKGA

To strengthen against IKGA, we propose two countermeasures. The first employs a Non-Interactive Key Exchange (NIKE) protocol based on the MLWE assumption [53], where each keyword is XORed with a shared secret established between the DO and the DU before the ABKS and Trapdoor algorithms. Since insider adversaries lack this secret, they cannot forge valid keywords, thereby preventing IKGA. This method imposes low overhead, as the secret can be established in advance, and it can be readily integrated into existing schemes. Nevertheless, it relies on a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) for secret establishment, scales poorly to multi-user settings, and requires prior coordination between parties, limiting its applicability in dynamic or large-scale environments.

The second approach binds the searchable encrypted keywords to the DO’s private key, while the trapdoor generation relies on the DO’s public key. This prevents insider adversaries from generating valid searchable ciphertexts without the DO’s private key, thus mitigating IKGA. However, this approach depends on a PKI, posing challenges analogous to those in verifiability mechanisms. Specifically, the DO’s public key must be accessible to all DUs, resulting in trapdoors that are unique to each DO’s document set.

Below, we present the modified algorithms of the baseline ABKS scheme (Section 5.2) to achieve IKGA resistance. Let be a hash function with uniform output.

- 1.

- : In this algorithm, the only modifications involve the matrix selection: and for .

- 2.

- : In this algorithm, only the first ciphertext component is modified as here and . Thus: .

- 3.

- : In this algorithm, the DU samples , and , then computes as follows:

- 4.

- : In this algorithm, the CS computes .

Next, we examine the correctness of the scheme. For and :

where . By Section 4.4 of [52] and Lemma 24 of [50], we have:

According to [46], the parameters must satisfy and , ensuring sufficiently large standard deviations in the and algorithms. Moreover, is required to keep the error term negligible.

Furthermore, we analyze the security of the IKGA-secure ABKS scheme against two attacks: IKGA (trapdoor indistinguishability) and SCKA (ciphertext indistinguishability). First, we define the Multi-Short Secret MLWE problem (Multi-ssMLWE), analogous to Definition 6 except that , where is as in [54].

Theorem 3.

The IKGA-secure scheme achieves semantic security against SCKA in the standard model, under the hardness assumption of the Multi-ssMLWE problem.

Proof.

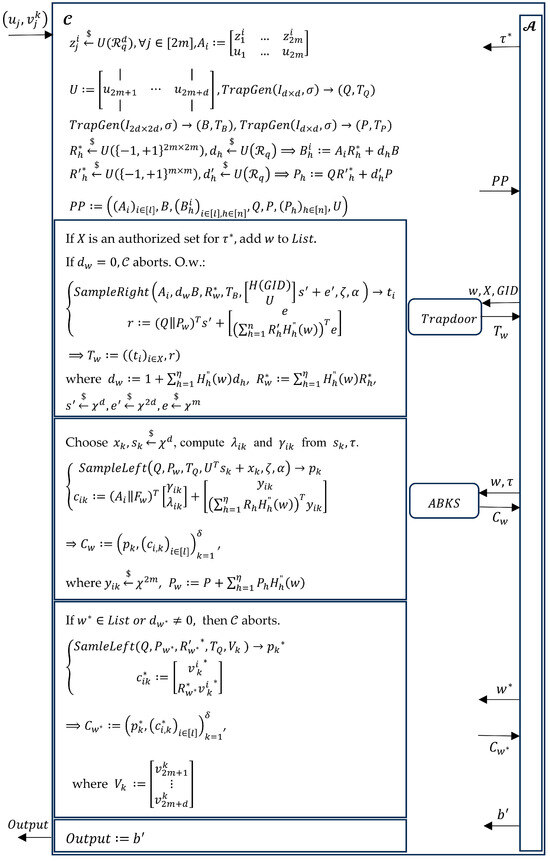

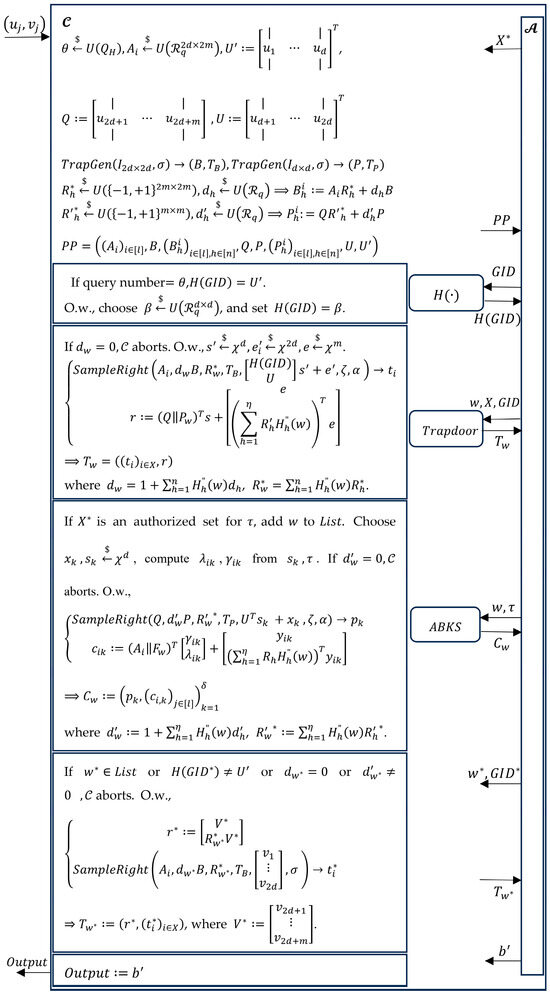

The proof follows the methodology of Theorem 2, summarized in Figure 2. □

Figure 2.

Semantic security against SCKA for IKGA-secure ABKS scheme.

Theorem 4.

The IKGA-secure scheme achieves semantic security against IKGA in the random oracle model, under the hardness assumption of the ssMLWE problem.

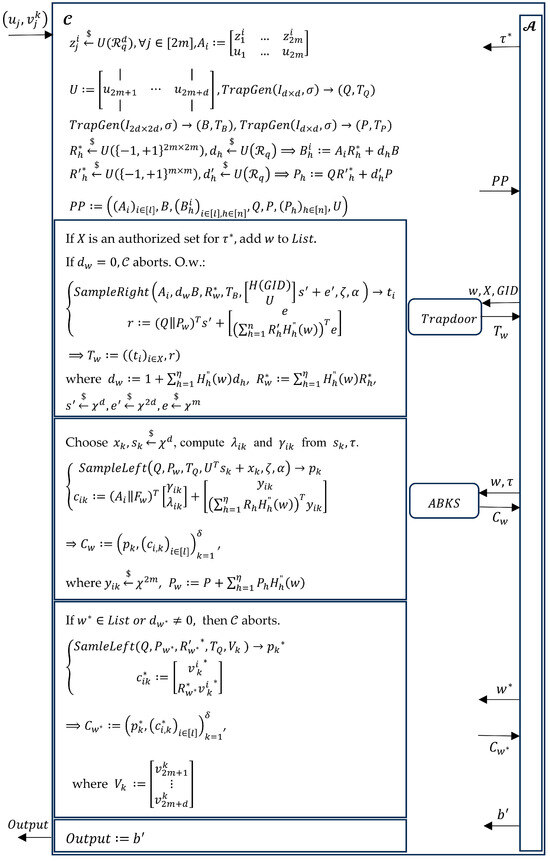

Proof.

The proof follows the methodology of Theorem 2, summarized in Figure 3. □

Figure 3.

Semantic security against IKGA for IKGA-secure ABKS scheme.

6. Efficiency and Experimental Evaluation

This section first presents a qualitative comparison of the features of our scheme with existing ones. Then, it analyzes the computational overhead and communication complexity of the proposed scheme. Table 1 compares the proposed scheme with recent ABKS schemes across ten key aspects: hardness, security model, collusion resistance, IKGA resistance, forward security, fine grained access control, verifiability, multi-authority, multi-keyword searchability and secret sharing mechanisms.

Table 1.

Comparison between ABKS schemes in terms of security and features.

Let be the security parameter (a power of two), a prime, with , the total number of attributes, and the keyword vector length. Sampling from and evaluating hash functions are assumed to have negligible complexity. Since the error probability is negligible, must hold. Given these parameters, the communication overhead of our schemes is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Communication overheads.

The computational complexity of our schemes is summarized in Table 3, where , , and denote the complexities of the , , and algorithms, respectively.

Table 3.

Computational complexity.

The proposed scheme was implemented on a workstation running Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS with an Intel® Core™ i7-12700H processor (4 cores), 8 GB of RAM, and a 60 GB hard disk, and the source code was developed using Visual Studio Code (version 1.104.2). The scheme described in Section 5.2 was executed 100 times, and the average runtime was recorded to minimize fluctuations. Following the methodology of [46], Table 4 summarized the computational complexity of the core algorithms per attribute for each keyword under the parameters: , corresponding to a 128-bit security level.

Table 4.

Computational complexity (ms).

The schemes demonstrate practical computation complexities, as shown in Table 4. Setup is relatively slower (~200 ms) but is performed only once by the TA. is fast (~6 ms), while encryption is the most time-consuming operation (~291–333 ms), yet it can be executed offline. generation (~16–18.5 ms) and (~6.2–6.5 ms) are efficient, whereas (<1 ms) and (~0.025 ms) are extremely fast, which is crucial for frequent and real-time access by the DU. The storage and communication overheads are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Storage and communication overheads (KB).

The storage and communication overheads of our schemes are practical, as shown in Table 5. The public parameters (~7.2–7.9 MB) can also be derived from a seed via a pseudorandom function to further reduce storage and transmission costs. The master secret key is securely held by the TA and the DO’s keys remain compact (~120–225 KB), making the scheme suitable for real-world cloud deployments. Encrypted keywords (~17–18 MB) are stored only on the server, while trapdoors (~240–360 KB) are transmitted on demand and proofs (~60 KB) impose minimal overhead. Overall, these are reasonable and provide a balanced trade-off between security and efficiency in multi-organizational settings.

Remark 2.

A direct numerical comparison with the most relevant lattice-based CP-ABKS schemes [11,34] is not feasible. The scheme in [34] lacks correctness and a formal reduction from the LWE problem, while [11] reports performance only for , which does not achieve the 128-bit security level. Also, it is not collusion resistant. Moreover, neither [34] nor [11] support several essential features provided by our scheme, such as verifiability, forward security, and multi-authority support. Other works in Table 1 are not lattice-based ABKS schemes and differ fundamentally in structure and functionality. Therefore, a numerical comparison would be misleading.

Finally, it is worth noting that structured LWE-based schemes, particularly MLWE-based constructions, offer inherent efficiency advantages over standard LWE-based designs. Their underlying ring/module structure enables polynomial multiplications to be computed efficiently via the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) [40]. This efficiency has led to their adoption in NIST post-quantum standards such as Kyber [40].

7. Conclusions

Attribute-Based Encryption with Keyword Search (ABKS) schemes enable authorized DUs to search over encrypted data using attribute sets. To counter quantum threats, post-quantum ABKS schemes have been developed, primarily leveraging the LWE problem. However, some existing schemes exhibit limitations, such as missing correctness proofs, verifiability, formal security proofs, and collusion resistance.

In this paper, we introduce a verifiable multi-authority ABKS scheme based on the MLWE problem. We formally prove the scheme is correct, verifiable, complete, and robust against collusion attacks. Additionally, we propose mechanisms to support multi-keyword search, forward security, and resistance to IKGA. After providing a rigorous security analysis, we evaluate the efficiency of the proposed scheme through both parametric analysis and an experimental implementation. The evaluation considers the computational complexity of Setup, KeyGen, ABKS, ProofGen, Trapdoor, Search, and Verify algorithms as well as communication overhead. Overall, the proposed scheme highlights the growing need for verifiable multi-authority encryption in real-world cloud infrastructures where sensitive records, such as medical, legal, and governmental datasets, must remain both confidential and searchable over long periods of time. The broader implications of this research extend to inter-organizational collaboration, reduced trust centralization, and sustainable cloud security in the presence of emerging quantum threats.

As a direction for future work, and while preserving all current security and functionality properties of the proposed scheme, private keys may be issued directly to DUs to eliminate reliance on TA interaction during trapdoor generation. Furthermore, incorporating mechanisms to conceal access policies represents a promising enhancement that could further strengthen the overall security and privacy guarantees of the scheme.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://github.com/SabaKarimani/MLWE_ABKS_2025 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology and formal analysis, S.K.; validation and investigation, S.K. and T.E.; resources, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and scientific editing, T.E.; supervision and project administration, T.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated in this study. The source code implementing the proposed cryptographic schemes, along with the complexity evaluation, is provided as Supplementary Materials and is available at: https://github.com/SabaKarimani/MLWE_ABKS_2025 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mohammad Sadegh Ahmadi for his valuable assistance in implementing the proposed scheme. OpenAI tools were utilized solely to assist with text editing during the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, D.X.; Wagner, D.; Perrig, A. Practical techniques for searches on encrypted data. In Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, S&P 2000, Berkley, CA, USA, 14–17 May 2000; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh, D.; Crescenzo, G.D.; Ostrovsky, R.; Persiano, G. Public key encryption with keyword search. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2004, Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Interlaken, Switzerland, 2–6 May 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 506–522. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, X. A ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption scheme supporting keyword search function. In Proceedings of the Cyberspace Safety and Security, 5th International Symposium, CSS 2013, Zhangjiajie, China, 13–15 November 2013; Springer: Cham, Swizterland, 2013; pp. 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Guo, H.; Zhong, F.; Cheng, W. An efficient revocable and searchable MA-ABE scheme with blockchain assistance for C-IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 2754–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Deng, R.H.; Liu, X.; Choo, K.K.R.; Wu, H.; Li, H. Multi-authority attribute-based keyword search over encrypted cloud data. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2019, 18, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghopur, D. Attribute-based searchable encryption with forward security for cloud-assisted IoT. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 90840–90852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yan, G.; Wei, Q. Attribute-based expressive and ranked keyword search over encrypted documents in cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2022, 16, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–22 November 1994; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchta, V.; Markowitch, O. Multi-authority distributed attribute-based encryption with application to searchable encryption on lattices. In Paradigms in Cryptology–Mycrypt 2016, Proceedings of the Malicious and Exploratory Cryptology: Second International Conference, Mycrypt 2016, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1–2 December 2016; Revised Selected Papers 2; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 409–435. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Li, X.; Yin, H.; Cao, C.; Zhang, L. Lattice-based multi-authority ciphertext-policy attribute-based searchable encryption with attribute revocation for cloud storage. Comput. Netw. 2024, 250, 110559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, G.; Chen, X.B.; Chen, Y.; Yiu, S.M. Privacy-Preserving in Cloud Networks: An Efficient, Revocable and Authenticated Encrypted Search Scheme. Comput. Netw. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, E.S.; Fan, C.I. Multi-keyword searchable identity-based proxy re-encryption from lattices. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhou, J.; Wu, G.; Zhang, M. Multi-keywords searchable attribute-based encryption with verification and attribute revocation over cloud data. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 139715–139727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Rao, Y.S. Searchable Attribute-Based Proxy Re-encryption: Keyword Privacy, Verifiable Expressive Search, and Outsourced Decryption. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhong, H.; Xu, Y. AKSER: Attribute-based keyword search with efficient revocation in cloud computing. Inf. Sci. 2018, 423, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Yang, F.; Liao, X. A novel search approach for secure and flexible sharing of hierarchical EHR based on blockchain. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; He, Q.; Zhao, B.; Guo, B.; Zhai, Z. Efficient Multi-Authority Attribute-Based Searchable Encryption Scheme with Blockchain Assistance for Cloud-Edge Coordination. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 76, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, F.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Practical attribute-based multi-keyword ranked search scheme in cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2019, 15, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, M. Dual-Policy Attribute-Based Searchable Encryption with Secure Keyword Update for Vehicular Social Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, W.; Zhang, F.; Ning, J. Efficient Attribute-Based Searchable Encryption with Policy Hiding over Personal Health Records. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 22, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehla, R.; Garg, R. Anonymous Attribute-Based Searchable Encryption for Smart Health System. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, B.; Chen, W.; Wang, H. Attribute-based searchable encryption with decentralized key management for healthcare data sharing. J. Syst. Archit. 2024, 148, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Xu, S.; Ateniese, G. VABKS: Verifiable attribute-based keyword search over outsourced encrypted data. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2014-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Toronto, ON, Canada, 27 April–2 May 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 522–530. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, L.; Xu, C.; Xu, L.; Yu, X.; Zuo, C. Verifiable Identity-Based Encryption with Keyword Search for IoT from Lattice. CMC-Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 68, 2299–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yiu, S.M.; Cheng, X. Lattice-based Forward Secure Multi-user Authenticated Searchable Encryption for Cloud Storage Systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefipoor, V.; Eghlidos, T. An efficient, secure and verifiable conjunctive keyword search scheme based on rank metric codes over encrypted outsourced cloud data. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 105, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.W.; Rhee, H.S.; Park, H.A.; Lee, D.H. Off-line keyword guessing attacks on recent keyword search schemes over encrypted data. In Workshop on Secure Data Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Chen, L. Public-key encryption with registered keyword search. In European Public Key Infrastructure Workshop; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Li, H. An efficient public-key searchable encryption scheme secure against inside keyword guessing attacks. Inf. Sci. 2017, 403, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Li, F. A new construction of public key authenticated encryption with keyword search based on LWE. Telecommun. Syst. 2024, 86, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Meng, F. Public key authenticated encryption with keyword search from LWE. In European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; He, B.; Zhang, D. A keyword-searchable ABE scheme from lattice in cloud storage environment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109038–109053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, M.; Zhang, J.; Fan, S.; Li, S. Attribute-based keyword search from lattices. In Infomration Security and Cryptology, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, Inscrypt 2019, Nanjing, China, 6–8 December 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Varri, U.S.; Pasupuleti, S.K.; Kadambari, K.V. CP-ABSEL: Ciphertext-policy attribute-based searchable encryption from lattice in cloud storage. Peer—Peer Netw. Appl. 2021, 14, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, H.; Lin, C.; Yan, X. ABAEKS: Attribute-Based Authenticated Encryption with Keyword Search Over Outsourced Encrypted Data. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 4970–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubashevsky, V.; Peikert, C.; Regev, O. On ideal lattices and learning with errors over rings. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2010, Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, French Riviera, France, 30 May–3 June 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Roşca, M.; Sakzad, A.; Stehlé, D.; Steinfeld, R. Middle-product learning with errors. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2017, Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 20–24 August 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, A.; Stehlé, D. Worst-case to average-case reductions for module lattices. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2015, 75, 565–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.; Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schanck, J.M.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehlé, D. CRYSTALS-Kyber: A CCA-secure module-lattice-based KEM. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), London, UK, 24–26 April 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Alagic, G.; Dang, Q.; Moody, D.; Robinson, A.; Silberg, H.; Smith-Tone, D. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lewko, A.; Waters, B. Decentralizing attribute-based encryption. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2011, Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tallinn, Estonia, 15–19 May 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 568–588. [Google Scholar]

- Micciancio, D.; Goldwasser, S. Complexity of Lattice Problems: A Cryptographic Perspective; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 671. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.J. Introduction to post-quantum cryptography. In Post-Quantum Cryptography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Micciancio, D.; Regev, O. Worst-case to average-case reductions based on Gaussian measures. SIAM J. Comput. 2007, 37, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. J. ACM 2009, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, P.; Eberhart, G.; Prabel, L.; Roux-Langlois, A.; Sabt, M. Implementation of lattice trapdoors on modules and applications. In Post-Quantum Cryptography: 12th International Workshop, PQCrypto 2021, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 20–22 July 2021; Proceedings 12; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Micciancio, D.; Peikert, C. Trapdoors for Lattices: Simpler, Tighter, Faster, Smaller. Eurocrypt 2012, 7237, 700–718. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C.; Peikert, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Trapdoors for hard lattices and new cryptographic constructions. In Proceedings of the Fortieth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Victoria, BC, Canada, 17–20 May 2008; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Beimel, A. Secret sharing and non-Shannon information inequalities. Ph.D. Thesis, Israel Institute of Technology, Technion, Haifa, Israel, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, S.; Boneh, D.; Boyen, X. Efficient lattice (h) ibe in the standard model. Eurocrypt 2010, 6110, 553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D.; Hofheinz, D.; Kiltz, E. How to Delegate a Lattice Basis, Report 2009/351;Cryptology ePrint Archive: 2009.

- Bert, P.; Fouque, P.A.; Roux-Langlois, A.; Sabt, M. Practical implementation of ring-SIS/LWE based signature and IBE. In Post-Quantum Cryptography: 9th International Conference, PQCrypto 2018, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 9–11 April 2018; Proceedings 9; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 9–11 April 2018, Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Gajland, P.; de Kock, B.; Quaresma, M.; Malavolta, G.; Schwabe, P. SWOOSH: Efficient Lattice-Based Non-Interactive Key Exchange. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; pp. 487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Boudgoust, K.; Jeudy, C.; Roux-Langlois, A.; Wen, W. On the hardness of module learning with errors with short distributions. J. Cryptol. 2023, 36, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Shao, H.; Wang, C. Attribute-based searchable encryption in edge computing for lightweight devices. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 3503–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).