1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the Internet of Things (IoT), from smart cards [

1] and mobile phones [

2] to smart home devices [

3], Public-Key Cryptosystems (PKCs) like RSA [

4] and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) [

5,

6] are foundational to securing embedded IoT devices. However, their physical implementations are vulnerable to Side-Channel Analysis (SCA) [

7], where attackers exploit physical leakages to recover secret keys [

8]. In PKCs, the executed sequence of fundamental operations depends on secret key bits. For example, ECC scalar multiplication iteratively performs point doubling and point addition [

9], while RSA modular exponentiation alternates between modular squaring and modular multiplication. Because these operations have different computational characteristics, they produce distinct and observable signatures in power or electromagnetic leakages. Simple Power Analysis (SPA) is a foundational horizontal attack that exploits this phenomenon. By inspecting a single trace, an attacker can visually distinguish operation patterns and reconstruct the operation sequence, thereby deducing the key. Horizontal analysis [

10] is therefore particularly important because it enables single-trace key recovery, which is often the only feasible option against protected assets such as TLS private keys or ECDSA scalars

k [

11] Its success hinges on distinguishing the unique trace signatures of key-dependent operations.

This recovery process typically involves segmenting the trace to locate operations, extracting distinguishing features from each segment, and classifying those features to reconstruct the secret key. Prior research has implemented this in various ways. For instance, Kabin et al. [

12] leveraged register addressing behaviors for a horizontal Differential Power Analysis (DPA) attack, while Shi et al. [

13] employed a Hilbert–Huang transform for feature extraction and denoising to achieve high accuracy in RSA key recovery.

A significant challenge, however, is that real-world traces are corrupted by noise. This, combined with countermeasures like random delays, hinders feature separation and creates low-confidence, ambiguous samples near the classification boundary. Misclassifying these samples disrupts the operation sequence, causing key recovery to fail. While Nascimento et al. [

14] and Perin et al. [

15] addressed this by replacing such outliers with a median value, this approach risks significant information loss by discarding potentially useful data.

To avoid this information loss, Wang et al. [

16] proposed a DBSCAN-CNN approach where density clustering identifies outliers [

17], which are then reclassified by a CNN. While effective, this method relies on DBSCAN, which has critical limitations for this task. Specifically, DBSCAN cannot be constrained to a specific cluster count and may partition data into more clusters than the actual operation types, necessitating a brute-force search of cluster combinations to find the key. To overcome these limitations and achieve robust, fully unsupervised key recovery, we propose that simply dividing data into outlier and non-outlier categories is too absolute, and DBSCAN itself has drawbacks such as being unable to specify the number of clusters.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in unsupervised SCA.

Section 3 describes the preliminaries for our proposed approach, including GMM and the application of CNNs.

Section 4 provides a detailed description of the proposed STAR framework. In

Section 5, we present the experimental results and analysis on different datasets. Finally, we draw conclusions and discuss future work in

Section 6.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we present an unsupervised clustering-correction framework for SCA that integrates self-training with deep neural networks. The proposed approach maximizes the utility of all collected traces by reclassifying low-confidence samples generated by traditional clustering algorithms through iterative refinement. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We introduce a novel framework, Self-Training Assisted Refinement (STAR), designed for unsupervised classification correction in side-channel analysis. STAR effectively combines clustering and self-training neural networks to identify key-dependent operations in public-key cryptographic algorithms without the need for any pre-labeled data.

The framework adopts a confidence-driven sample selection strategy. High-confidence samples obtained from the initial clustering serve as the initial training set for a neural network, which subsequently reclassifies low-confidence samples. Through iterative expansion of the training set, STAR progressively improves both classification accuracy and model stability.

We evaluate STAR on three datasets derived from public-key cryptographic implementations. On the ECC dataset protected with random delay countermeasures, STAR achieves a complete recovery of key-dependent operation sequences with 100% accuracy. Compared to state-of-the-art methods [

16,

18], the proposed framework improves overall accuracy by 12% to 48% and substantially reduces the search complexity associated with unknown cluster combinations.

2. Related Work

Unsupervised operation classification in SCA for PKC constitutes a significant challenge, driving foundational and hybrid research efforts. Early studies by Heyszl et al. [

19] and Perin et al. [

15] in 2014 established the viability of using elementary clustering techniques, such as K-Means and its variants, to distinguish cryptographic operations directly from single-execution traces. However, these purely clustering-based methods proved highly susceptible to real-world factors like noise, high dimensionality, and sophisticated countermeasures, frequently resulting in ambiguous classification boundaries and placing a burdensome requirement on post-clustering enumeration to recover the key. In parallel to the DL-based methods described next, another line of research sought to improve accuracy by replacing elementary clustering with more advanced techniques. For instance, Qian et al. [

18] proposed the UMAP-HC framework, which applied manifold learning and hierarchical clustering to achieve high fidelity classification, though still falling short of perfect accuracy on some countermeasure-protected traces. To overcome these limitations, the field progressively moved toward hybrid approaches by integrating Deep Learning (DL). CNNs, as demonstrated by Cagli et al. [

20] in 2017, possess intrinsic capabilities for robust feature extraction that counteract trace desynchronization, prompting their combination with clustering schemes. Perin et al. [

15] in 2021 advanced the semi-supervised domain by introducing an iterative learning framework where a CNN progressively corrected misclassifications generated by initial K-Means clustering. Further efforts, exemplified by the DBSCAN-CNN scheme introduced by Wang et al. [

16] in 2022, employed density-based clustering to isolate high-confidence samples for training a CNN model specifically designed to reclassify outliers. Despite their improved efficacy against noisy data, these sophisticated hybrid models retain a critical operational limitation: clustering methods like DBSCAN often yield a non-deterministic number of clusters, which then reintroduces the computationally expensive requirement for brute-force searching to map the resulting clusters to the true cryptographic operation classes. The proposed STAR framework fundamentally resolves this deficiency by initiating with a fixed-component GMM to generate high-purity pseudo-labels, which are subsequently refined through a confidence-driven self-training CNN loop. This novel combination ensures the initial classification aligns deterministically with the expected number of operation classes, thereby delivering a robust operation classification while entirely eliminating the complex and computationally demanding need for cluster enumeration.

4. Self-Training Assisted Refinement for SCA

The central challenge of SCA on public-key cryptography lies in identifying key-dependent operations from a single trace. In practical measurements, noise and high dimensionality hinder standard unsupervised algorithms from achieving sufficient classification accuracy.

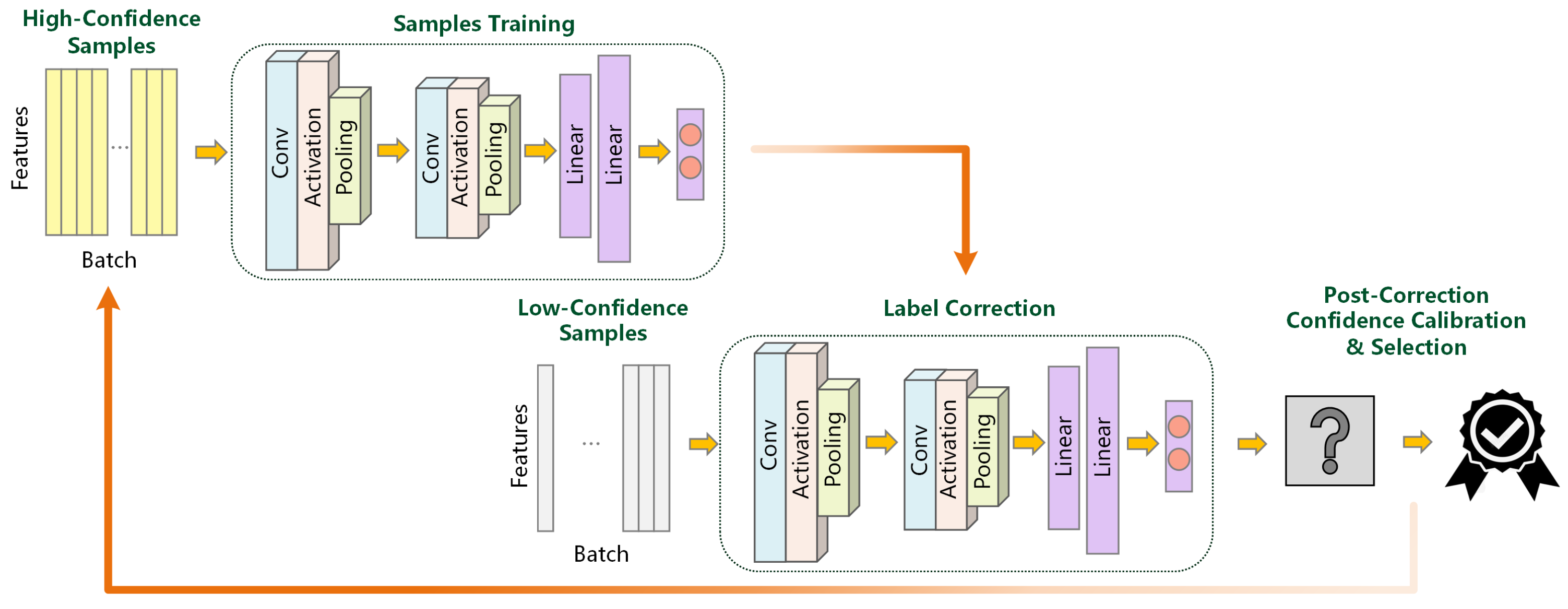

To overcome these limitations, we introduce STAR, a two-stage unsupervised classification correction framework. The overall workflow for executing a SCA is illustrated in

Figure 1. When the chip performs cryptographic operations, it produces various side-channel leakage signals, such as timing [

25], power [

26], electromagnetic radiation [

27], illumination [

28], and sound [

29]. In this paper, we focus on analyzing the most common of these, power traces, as they clearly reflect the cryptographic operations. Then, they are captured by high-precision physical probes and an oscilloscope. We subsequently use our proposed STAR to analyze these power traces. This acquisition stage produces a set of operation-related physical measurement traces. We then analyze these traces using our proposed STAR, leveraging their statistical correlation with the secret key.

The proposed framework STAR incorporates a label-free annotation mechanism based on self-training, enabling it to automatically refine the clustering of key-dependent operations. As STAR is designed for horizontal, single-trace analysis, the entire process operates on the segments derived from this one trace. By iteratively correcting low-confidence samples generated in the initial unsupervised stage, the framework enhances classification reliability and improves the overall accuracy of operation identification.

STAR operates in two sequential stages. In the first stage, GMM clustering is applied to generate pseudo-labels, where high-confidence samples serve as initial supervision. In the second stage, a CNN refines the classification by iteratively correcting and expanding the training set with newly identified samples. This two-stage process enables STAR to transform unsupervised clustering results into accurate operation classifications.

4.1. GMM-Based Pseudo-Label Generation

The goal of this stage is to automatically extract a reliable subset of labeled samples from fully unlabeled trace segments. Side-channel trace is divided into operation-level segments, and a feature vector is computed for each segment . Before fitting the GMM, each operation segment is mapped to a low-dimensional representation that suppresses noise and preserves discriminative structure.

The feature distribution is modeled by a Gaussian Mixture Model with parameters

As defined in Equation (

2), the posterior responsibility for segment

i and component

k is

which quantifies the probability that

belongs to component

k. In this work, the number of components is fixed to

, matching the two key-dependent operation types in the target ECC or RSA implementation. The model is initialized and trained with a standard E-M procedure using conventional parameter settings to ensure stable convergence without manual tuning.

To assess clustering reliability, a confidence margin is computed from the posterior probabilities as

where

and

are the two posteriors. Segments with

are regarded as high-confidence and assigned pseudo-labels

, while low-confidence samples are deferred to the subsequent correction stage. The resulting high-confidence subset and their soft targets form the initial training set for self-training refinement. Using soft labels provides probabilistic targets that encode uncertainty for boundary samples, thereby mitigating early label noise, improving the calibration of network posteriors, and stabilizing the self-training loop for faster convergence.

4.2. CNN-Based Iterative Correction and Augmentation

This stage refines the classification results obtained in Stage 1 through an iterative self-training process. As illustrated in

Figure 2, a one-dimensional CNN is employed to process trace segments. The network is composed of several convolution–activation–pooling modules followed by fully connected layers, enabling hierarchical extraction of temporal features and mapping them to operation classes. The model is first trained using the high-confidence samples and their corresponding soft targets generated in the previous stage. By training on these probabilistic labels rather than hard 0/1 assignments, the initial CNN learns directly from the GMM’s confidence distribution, which is a key aspect of using soft labels. Owing to the reliability of these pseudo-labels, the initial CNN already possesses a basic ability to distinguish between key-dependent operations.

The CNN-based iterative correction and augmentation stage uses a one-dimensional CNN designed to discriminate features in high-dimensional side-channel trace segments. The network begins with a batch normalization layer that standardizes the input features and stabilizes training in the subsequent self-training iterations. Feature extraction is carried out by two convolutional blocks with a kernel size of seven, which is chosen to capture local temporal dependencies and leakage patterns within each trace segment. ReLU activations are applied after the convolutional layers. The convolutional backbone is followed by three fully connected layers that map the extracted high-level features to the final classification space, and the output layer contains one neuron per cryptographic operation class. For training, the model is optimized using Adam. The hyperparameters are chosen to maintain stability and limit overfitting when learning from noisy pseudo-labels. The initial learning rate is set to of the self-training. A batch size of 16 is used, providing sufficient stochasticity during optimization while preserving reliable gradient estimates on low-confidence or previously unseen samples.

After initial training, the CNN predicts class probabilities for low-confidence samples. Let

denote the output probability vector of sample

i, and let

and

be its two largest elements. The confidence margin is defined as

which follows the same concept as the confidence measure in Equation (

8) but operates on network posteriors. Samples whose

exceeds a predefined threshold

are regarded as reliable and added to the training set with predicted labels

. The model is then retrained on this expanded dataset, and the process iterates with new predictions on the remaining low-confidence samples. The iteration continues until no additional samples satisfy the threshold or the validation accuracy converges.

Through this iterative correction and augmentation mechanism, the CNN progressively learns from initially uncertain data, gradually enhancing its discriminative capacity. This process transforms previously unlabeled or ambiguous segments into confidently classified samples, ultimately yielding a model capable of high-precision identification of key-dependent operations across the entire dataset.

This stage lies in transforming a conventionally supervised CNN into a self-supervised model that autonomously expands its knowledge through iterative learning. The CNN alternates between inferring pseudo-labels and refining model parameters. Each iteration effectively maximizes the likelihood of the data under the model’s evolving decision boundaries. This dynamic expansion allows the CNN to gradually learn from unlabeled samples with increasing reliability, improving both generalization and predictive precision. Through this self-reinforcing mechanism, the network transitions from limited supervision to comprehensive understanding, ultimately achieving accurate classification across the entire trace dataset.

5. Experiments Results and Analysis

This section evaluates the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage clustering-correction framework STAR. We first describe the experimental environment, datasets, and evaluation metrics. Subsequently, we assess the framework’s capability to correct misclassified samples and improve overall accuracy across multiple public-key algorithm datasets. Comparative results against representative baseline methods are also presented to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed approach in terms of classification precision and robustness.

The experimental evaluation of the STAR framework utilizes power traces derived from three distinct public-key cryptographic implementations. Crucially, the analysis focuses on single-trace analysis, where only one physical measurement trace is collected for each algorithm, making the challenge of operation classification significantly more difficult than multi-trace profiling.

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the datasets employed. The datasets encompass diverse cryptographic settings and countermeasures. The ECC-RD dataset features an Elliptic Curve Cryptography implementation on the SAKURA-G development board with random delay (RD) countermeasures, targeting a 255-bit key and resulting in 387 cryptographic operations. The RSA dataset involves a 1024-bit key implemented on a commercial smart card using a co-design approach, yielding 1561 fundamental modular operations. Finally, the SM2 dataset, based on China’s national standard cryptographic algorithm with a 256-bit key, was also collected from a smart card using a co-design implementation, resulting in 372 key-dependent operations.

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Experimental Environment and Datasets

We conduct the experiments using the PyTorch library in Python 3.12 on a workstation equipped with an Nvidia GTX 4090 GPU. To assess effectiveness and generalization, we evaluate on three representative public key cryptography datasets: ECC with random delay countermeasures, RSA, and SM2. These datasets span distinct algorithms and implementations, exposing the method to heterogeneous leakage and countermeasure conditions and enabling evaluation across varied scenarios.

For all experiments, power traces were acquired using a PicoScope 3403D oscilloscope. For the ECC-RD dataset, the sampling rate was set to 62.5 M/s, with a total of 1,920,000 sample points collected for the single trace. For the RSA dataset, the sampling rate was set to 1 M/s, with a total of 4,800,000 sample points collected. For the SM2 dataset, the sampling rate was set to 125 M/s, with a total of 4,000,000 sample points collected. These high-resolution traces capture the fine-grained leakage characteristics necessary for distinguishing between subtle cryptographic operations.

5.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

Performance is evaluated using two metrics:

Accuracy: The ratio of the number of correctly classified operations to the total number of operations. In this paper, since the initial data is unlabeled, our main focus is on the final classification accuracy obtained after the complete correction process, by comparing the results against the known ground truth sequence of operations.

Traversal Count: After clustering yields K clusters while the ground truth contains two operation classes, we must decide which clusters correspond to each class. Traversal count is the number of candidate cluster to class assignments that need to be examined, in a fixed and deterministic order, until the correct mapping is identified. A smaller traversal count indicates lower search effort and higher practical usability.

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

This section details the experimental procedures and results of validating the proposed framework on three distinct datasets.

5.2.1. Experimental Results on the ECC with Random Delay

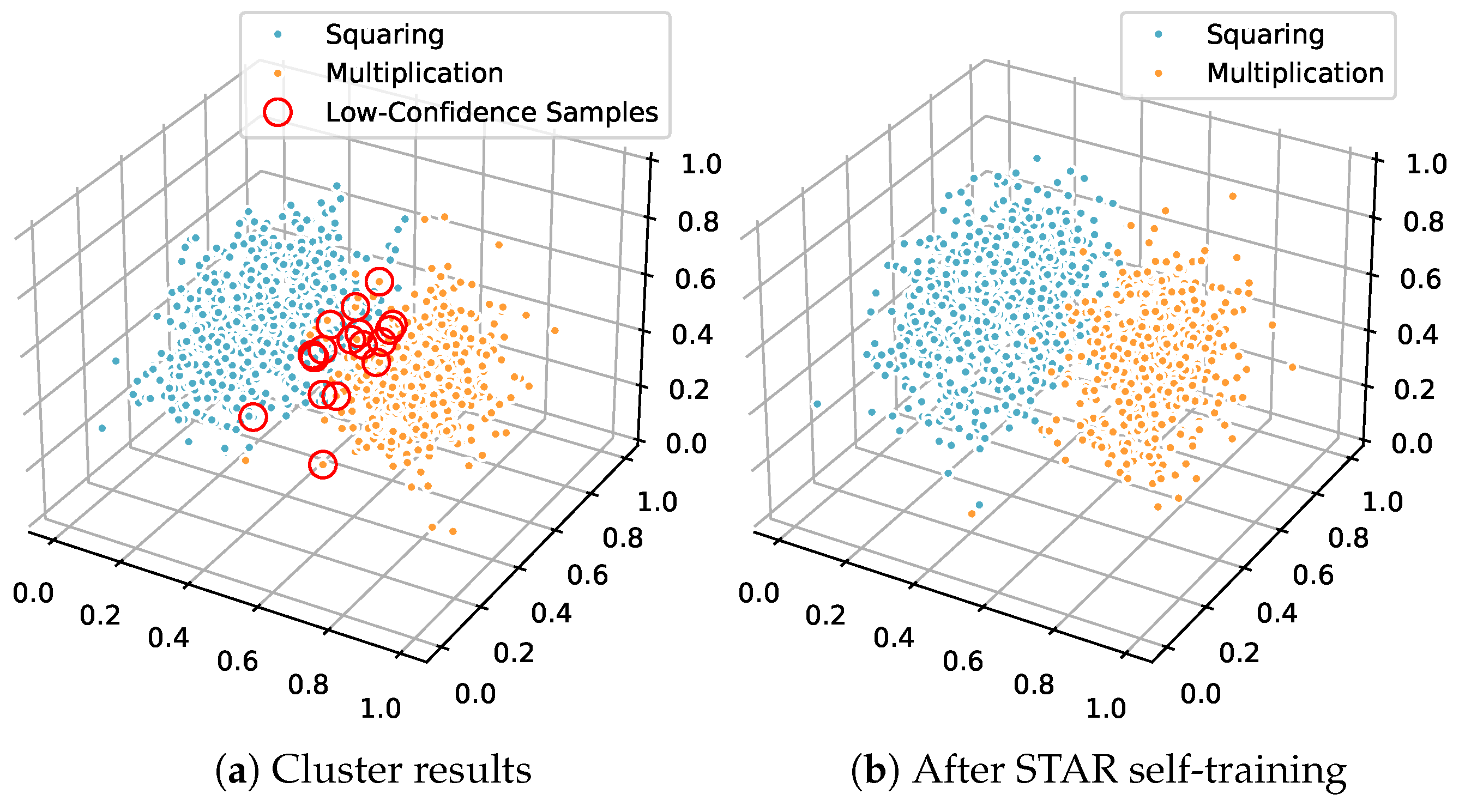

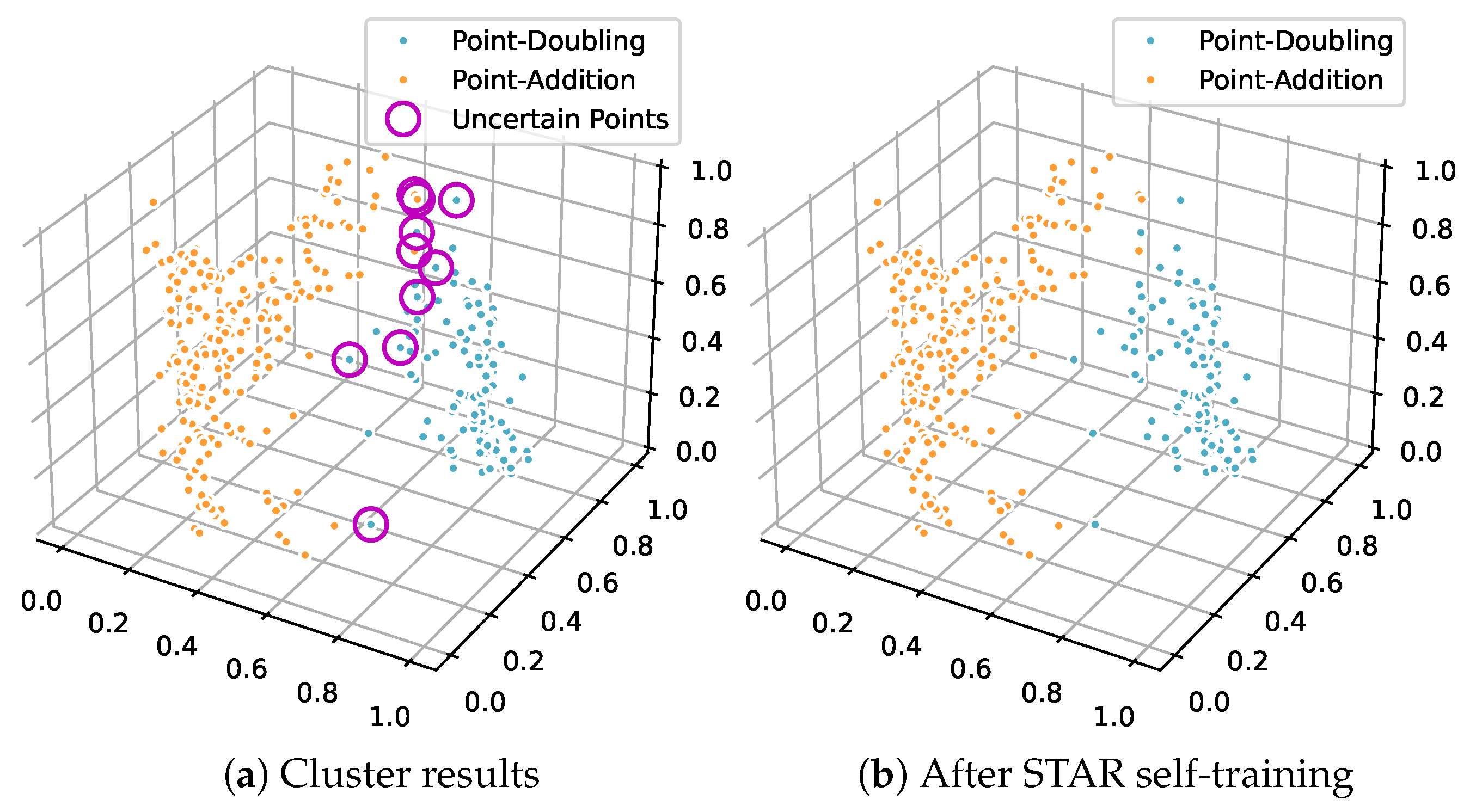

For the ECC dataset protected by random delay countermeasures, features were embedded into a three-dimensional space by PCA and clustered by GMM with a confidence threshold of

. As shown in

Figure 3a, 357 segments were identified as high-confidence, while 27 segments near the cluster interface remained uncertain. A CNN trained on the high-confidence seed set then entered the self-training loop. Within 15 iterations, all uncertain segments exceeded the margin threshold in Equation (

8) and were promoted with consistent labels, the result was shown in

Figure 3b, yielding

final accuracy by comparing against the known ground-truth labels. The improvement reflects the CNN’s ability to learn shift-robust features that counteract misalignment introduced by random delays, which increases posterior margins on boundary samples. No enumeration of cluster–class assignments was required, so the traversal count is 0.

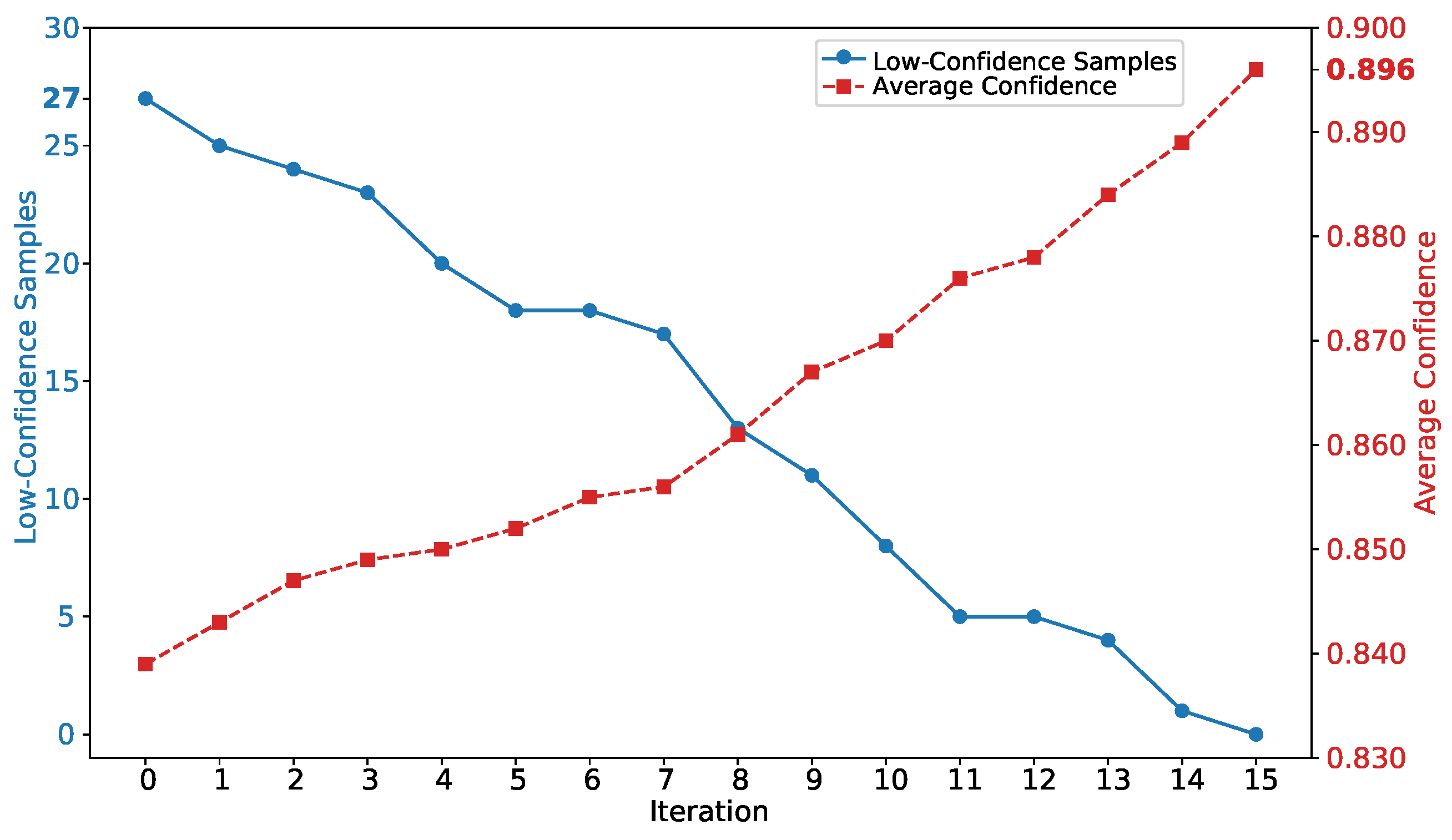

To illustrate the self-training dynamics,

Figure 4 plots the number of low-confidence samples and their mean confidence across iterations. The blue curve decreases monotonically from 27 to 0 by iteration 15, indicating that initially ambiguous samples are progressively reclassified and their uncertainty resolved in each training cycle. In parallel, the red curve rises steadily, showing increasing average confidence among the remaining low-confidence samples as newly labeled (pseudo-labeled) data is incorporated. The strong negative correlation between these two metrics provides clear evidence of convergence of the self-training loop. By iteratively augmenting the training set with high-confidence samples, the mechanism refines model weights and ultimately enables accurate predictions for all samples.

5.2.2. Experimental Results on the RSA

For RSA, ISOMAP provided the low-dimensional embedding, reducing the feature space to three dimensions. With a threshold of

, initial GMM clustering produced 17 low-confidence segments (

Figure 5a). Self-training proceeded for 29 iterations until no low-confidence samples remained. The final distribution in

Figure 5b matches ground truth with

accuracy. The larger number of iterations compared with ECC suggests stronger local overlap between mixture components, yet the confidence-driven promotion prevents error accumulation by admitting only high-margin predictions.

5.2.3. Experimental Results on the SM2

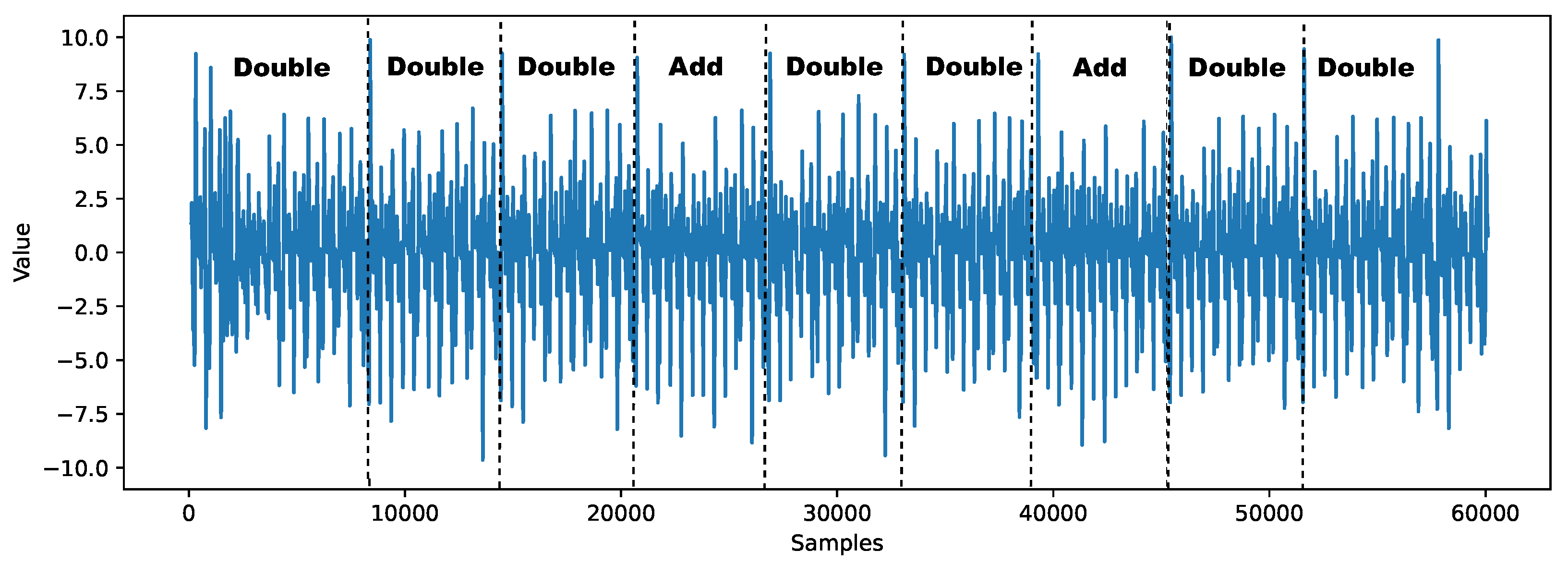

The power consumption trace for a scalar multiplication operation, executed by our implementation of SM2 on a commercial smart card, is depicted in

Figure 6. Power analysis of the traces indicates that this cryptographic operation is composed of a series of periodic segments. Notably, the core operations of elliptic curve point doubling (represented by “Double”) and point addition (represented by “Add”) present distinct patterns on the traces.

The complete scalar multiplication comprises 372 key-dependent operations. PCA was used for dimensionality reduction, transforming the high-dimensional feature vectors into a three-dimensional space. With a threshold of

, GMM produced 362 high-confidence segments and 10 low-confidence segments located at the boundary between two clusters (

Figure 7a). After 25 iterations of self-training, all remaining samples crossed the margin threshold and were promoted, the result was shown in

Figure 7b, leading to

accuracy by comparing against the known ground-truth labels. The behavior mirrors an E-M like refinement: pseudo-label inference followed by parameter updating contracts decision uncertainty each round. Traversal count is 0.

5.2.4. Summary

Across ECC, RSA, and SM2, the low-confidence samples shrinks to zero and the posterior margin increases on previously ambiguous samples. This pattern supports the intended mechanism of STAR: GMM provides a high-purity seed set, and the CNN enlarges it through confidence-guided promotion until convergence, delivering perfect classification without any cluster–class enumeration.

5.3. Quantitative Validation with Confusion Matrices

To address the concern for rigorous quantitative evidence, we provide confusion matrices for the final classification results of the STAR framework. These matrices are generated by comparing STAR’s final predictions against the known ground-truth operation labels for each trace.

For the ECC-RD dataset, the confusion matrix shown in

Table 2 clearly demonstrates a perfect classification. The framework achieved 256 True Positives (TP) and 128 True Negatives (TN), with zero False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN). This confirms 100% accuracy, precision, and recall, quantitatively verifying the complete recovery of the operation sequence.

For the RSA dataset, the result was shown in

Table 3, the framework achieved 1041 TP and 520 TN. The absence of any misclassifications results in a 100% overall accuracy, supporting the framework’s ability to maintain perfect discriminative capacity.

For the SM2 dataset, the result was shown in

Table 4, the results confirm 100% classification accuracy with 252 TP and 120 TN. Crucially, the 0 value for FPs and FNs demonstrates that the self-training correction mechanism successfully resolved all initial boundary uncertainties to yield a flawless final classification.

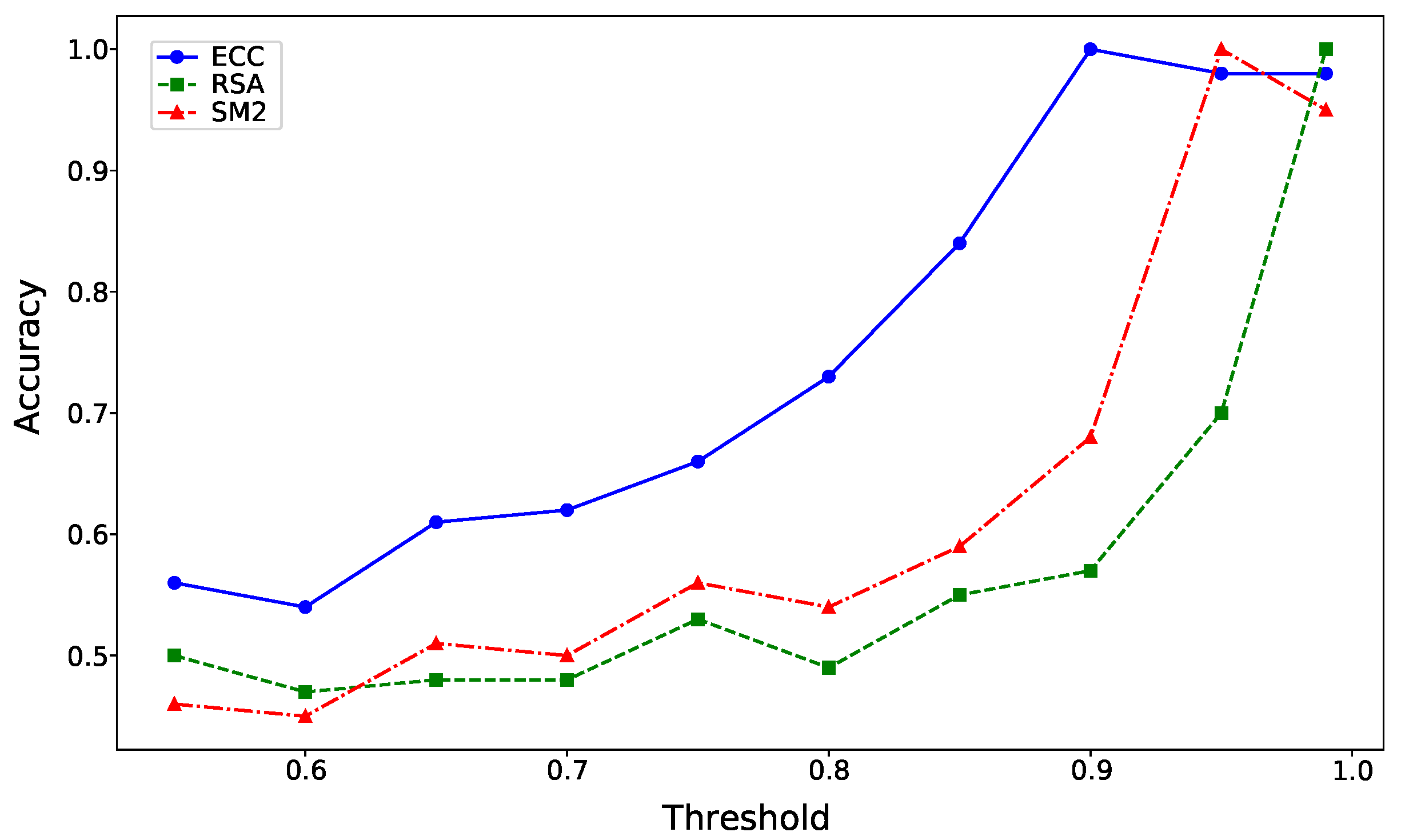

5.4. Influence of Confidence Threshold

We further examined the impact of the confidence threshold on the performance of our proposed framework. As illustrated in

Figure 8, experimental results on the ECC dataset reveal that a confidence threshold of

yielded a perfect classification accuracy of

. However, when the threshold was lowered to

, accuracy significantly decreased to

. Similarly, increasing the threshold to

resulted in a slight drop to

. These observations highlight the importance of selecting an optimal threshold. A too permissive threshold allows low-confidence samples to be incorrectly incorporated into the initial training set, diminishing the overall quality of the labeled data. Conversely, an overly restrictive threshold reduces the number of high-confidence samples available for training, limiting the model’s ability to generalize effectively. The results emphasize that the threshold of

strikes a balance, ensuring both the quality and quantity of the initial high-confidence training set. This enables our STAR framework to classify the entire sample set with complete accuracy.

Similarly, on the RSA dataset, as shown in

Figure 5a,b, a threshold of

resulted in

accuracy. However, when the threshold was relaxed to

, the accuracy plummeted to

. This further underscores the significance of high-confidence pseudo-labels in ensuring model convergence. Inadequate confidence thresholds lead to a mix of incorrect labels, undermining the self-training loop’s ability to refine the model.

On the SM2 dataset, shown in

Figure 7a,b, a threshold of

yielded perfect accuracy. Reducing the threshold to

resulted in a substantial accuracy drop to

, reinforcing the conclusion that too lenient a threshold fails to provide sufficient high-confidence labels for effective training.

These findings across all datasets highlight the pivotal role of the confidence threshold in optimizing the self-training phase. The results also suggest that our framework is highly sensitive to the initial training set’s quality, which can dramatically influence its final performance. By selecting an optimal threshold, such as for ECC, for RSA, and for SM2, we ensure that the model is trained on a sufficiently reliable set of pseudo-labeled data, allowing it to reach optimal classification accuracy.

These findings also address the critical question of how to select

in a practical, unsupervised setting. The choice of

represents a well-known trade-off between the purity and the quantity of the initial seed set. If

is set too low, the seed set quantity is high, but its purity is low, it is “polluted” with misclassified samples. As

Figure 8 shows, this causes the self-training to fail. If

is set too high, the seed set purity is perfect, but its quantity is too small for the CNN to train effectively. Therefore, by generating a sample confidence distribution plot, we identify a candidate threshold interval. For each threshold within this interval, we then calculate the corresponding high-confidence sample coverage rate and the average confidence. We select a threshold where both of these metrics are determined to be high. The goal is to choose a value that is high enough to ensure purity while still retaining a sufficient quantity of high-confidence samples to form a robust initial training set. The STAR framework is robust to values within this high-purity plateau.

5.5. Comparative Experiments

We benchmark STAR against K-Means, DBSCAN, GMM, and the DBSCAN-CNN scheme [

16] on three datasets. We also include a comparison with a recent state-of-the-art unsupervised method, UMAP-HC [

18], which employs UMAP for dimensionality reduction and Hierarchical Clustering (HC) for classification.

Table 5 reports classification accuracy. For ECC-RD, we also discuss the traversal count that measures the search effort to map clusters to operation classes.

On ECC-RD, STAR reaches

accuracy with a traversal count of 0. The gain comes from two design choices. First, Stage 1 fixes the mixture to two components, which matches the two operation types and removes the need for cluster–class enumeration. Second, GMM posteriors provide soft labels that seed a high-purity training set, after which the CNN promotes confident predictions and shrinks the uncertain samples through iterative augmentation. In contrast, DBSCAN yields five clusters on ECC-RD. The DBSCAN-CNN approach [

16] achieves

accuracy only after resolving the cluster–class mapping by search, which requires 50 traversals. GMM attains

accuracy without traversal, while K-Means performs worst at

due to its sensitivity to nonconvex structure and misalignment in side-channel features.

Generalization results on RSA and SM2 further distinguish the methods. DBSCAN-CNN degrades to on RSA and on SM2. GMM remains strong at on both datasets because calibrated posteriors handle boundary uncertainty better than hard assignments. STAR attains accuracy on RSA and SM2 as well, indicating that using probabilistic soft labels, and expanding the training set by confidence-guided self-training together provide stable decision boundaries.

UMAP-HC attains an accuracy of 1.00 on SM2 and 0.98 on RSA, but only 0.99 on the more challenging ECC-RD dataset. This indicates that even advanced manifold learning and clustering techniques are insufficient to perfectly resolve all boundary samples in the presence of strong countermeasures like random delay.

In contrast, STAR attains 1.00 accuracy across all three datasets. This demonstrates the unique advantage of our hybrid approach: GMM provides a robust initial clustering, but it is the CNN-based iterative self-training that successfully corrects the most difficult low-confidence samples that other unsupervised methods misclassify. STAR’s ability to achieve perfect classification where UMAP-HC falters highlights the necessity and superiority of our self-training refinement stage.

In summary, STAR improves accuracy across all datasets and eliminates cluster–class enumeration on ECC-RD. Compared with the DBSCAN-CNN pipeline of [

16], STAR offers a simpler mapping process and stronger stability while preserving perfect classification on ECC-RD.

5.6. Computational Cost and Efficiency

The computational cost of the self-training process was quantified across all three datasets to establish the framework’s practical efficiency.

Table 6 shows the experimental overhead of different algorithms. The training time, measured as the duration required for the iterative self-training to achieve convergence, varied by dataset complexity. The ECC-RD model achieved the fastest training time at

min. The SM2 model required

min, and the RSA model exhibited the longest convergence time at

min.

Resource utilization metrics, assessed during the most resource-intensive training periods, demonstrated consistent and near-maximum utilization of the central processing unit across all experimental runs. CPU utilization registered for ECC-RD, for RSA, and for SM2. GPU memory utilization, quantified in Gigabytes of usage, was observed to be highest for the RSA model at GB, followed by GB for both the ECC-RD and SM2 models. System memory utilization showed high consistency across datasets, with consumption rates of for ECC-RD, for RSA, and for SM2.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented a solution to the critical problem of classification accuracy in unsupervised SCA, where noisy, high-dimensional data often confounds traditional methods. We introduced the STAR framework, a novel two-stage methodology. This approach effectively synergizes the initial grouping capabilities of clustering algorithms with the sophisticated pattern recognition of a self-training neural network, creating a robust system that operates without any need for pre-labeled data.

The core of our method lies in a dynamic correction loop. It begins by identifying high-confidence samples from an initial clustering phase to create a reliable pseudo-labeled training set. A neural network trained on this set then re-evaluates and corrects low-confidence samples. This process is iterated, progressively expanding the training data and enhancing the model’s accuracy and convergence speed.

Our experimental validation on three distinct real-world datasets from public-key algorithms confirms the efficacy of this framework. We achieved a 100% accuracy in recovering cryptographic operation types. This result not only demonstrates a significant performance increase of 12% to 48% over current state-of-the-art techniques but also simplifies the analytical process by reducing the search complexity for unknown clusters. Future work will focus on making STAR easier to use in practice. We plan to add an automatic rule that sets the confidence threshold from validation feedback.