1. Introduction

In today’s digital age, protecting data is paramount because it can be accessed by anyone, anywhere. Several studies have demonstrated that vulnerabilities in communication systems can lead to significant disruptions, including data loss and disorganization, as well as the compromise of the integrity of organizational and personal data [

1]. These risks have made data security a central priority for organizations that rely heavily on computer systems for business operations and data handling. A consistent risk in computer systems is the possibility of unauthorized individuals accessing sensitive data. Since this risk is always present, securing database access must be a top priority [

2].

Encryption is a technology that provides a cryptosystem for transmitting data from the source to the destination in secret. Many vendors have implemented various data security methods, one of which is Transparent Data Encryption (TDE). TDE is applied to data at rest, primarily to encrypt files and logs in real time at the disk level [

3]. This study analyzes the performance impact of TDE on databases by measuring execution times and system resource usage, including the central processing unit (CPU), random-access memory (RAM), and disk activity. We used the TPC-H benchmark to measure the impact of encryption overhead because its dataset and queries simulate typical data-intensive operations [

4].

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) was chosen as the primary encryption algorithm due to its widespread implementation and access to native encryption in different databases. Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recognize AES as a reliable and efficient encryption standard. Its widespread use in various industries reinforces its reliability and trusted status [

5].

This study evaluates the performance of the three most popular relational database management systems: Oracle 19c Enterprise Edition, version 19.3.0.0.0; MySQL versions community v8.0.38 and Enterprise 9.2; and SQL Server 2022 version 16.0.1130.5 (X64)—RTM-GDR (KB5046057). According to the official documentation, MySQL primarily supports the AES-256 encryption standard, while SQL Server allows the use of AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256. The TPC-H benchmark was used to query the three databases with three Scale Factors (0.1, 1, and 10), in order to measure query execution time, CPU usage, RAM consumption, and disk utilization under different encryption configurations.

The main contributions of this paper are the following:

Evaluation of the impact of applying the AES algorithm to encrypt Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server databases;

A comparison of different existing encryption algorithms.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the related work, focusing on related studies that evaluate database performance encryption impact, more specifically, those that use Transparent Data Encryption with the AES.

Section 3 describes the materials, environments, and methods used for the experiments.

Section 4 presents and analyzes the results. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusions and ideas for potential extensions of this research.

2. Related Work

Many papers have been written about transparent data encryption and its impact on database performance. This section aims to describe some existing studies that evaluate the impact of AES encryption on query read performance across Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server databases. It also provides insights into relevant studies related to this topic.

Moulianitakis et al. in [

6] present a benchmarking framework created to evaluate how Transparent Data Encryption (TDE) affects database performance. The study tested SQL Server 2019 and MySQL 8.0 using different encryption algorithms (AES and Triple Data Encryption Algorithm (3DES)) and key lengths, focusing on metrics like execution time, CPU usage, throughput, and storage impact. Results showed that TDE adds only a small performance overhead, especially during insert operations in MySQL. AES performed better than 3DES thanks to hardware-level support, and overall, SQL Server 2019 delivered better results than MySQL in terms of speed, efficiency, and resource use when TDE was enabled.

Santos et al. [

7] analyze the performance impact of Oracle TDE using AES and 3DES in data warehouses. Based on TPC-H benchmarks at 1 GB and 10 GB, it was found that encryption significantly increased query response times. Overall overhead ranged from 30% to 163%, while individual query response time increased by 100% to 1000%. These figures far exceed Oracle’s claimed average overhead of 5–10%.

Madyatmadja et al. in [

3] aimed to compare the performance impact of Transparent and Non-Transparent Data Encryption on hardware usage. It found no major differences between the two in terms of CPU and memory consumption. TDE caused only a slight increase of about 8% in CPU usage and 2% to 4% in memory. However, during backup operations, TDE introduced a performance overhead of around 10% to 18%.

In [

8], Lukaj et al. explore a Cloud/Edge computing approach, where data is offloaded from edge devices to the cloud to overcome local storage limitations. To protect the data during transfer, TDE is used to encrypt it at the edge before sending it to a cloud-based distributed database. The study highlights how TDE can be effectively applied in various scenarios where data security and privacy are essential.

The study conducted by Istifan et al. [

9] compared the performance of AES encryption (128, 192, and 256-bit) in MariaDB and MySQL using Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) tests. In MariaDB, the results showed no significant difference in transaction throughput between key lengths (

p-value = 0.5781). The average transaction per minute remained consistent and was slightly higher than the unencrypted baseline. In contrast, MySQL’s results showed statistically significant differences (

p-value = 0.0002915), with AES-256 causing a small drop in performance. Overall, MariaDB handled encryption with minimal impact, while MySQL showed a slight slowdown with AES-256, and MariaDB consistently processed nearly twice as many transactions per minute as MySQL.

In [

10], Hussein focuses on performing comparative analysis of Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server databases. The findings show that all three databases are well-suited for analytical and data science queries. However, Oracle and SQL Server proved to be the most efficient databases when running group functions over large sets of data, compared to MySQL, which was only proficient in handling simple aggregations. In addition, Oracle and SQL Server offer more robust security than MySQL. They are better choices for systems that require more complex data processing, demanding security, scaling, and integration with non-relational or unstructured data. MySQL can be used for lighter applications that do not require advanced features.

AbdAllah et al. explain in [

11] how Advanced Encryption Standard New Instructions (AES-NI), a set of hardware instructions, speeds up key parts of the AES algorithm, like SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, and AddRoundKey, by running them directly on the processor. This reduces the number of instructions needed and leads to significant performance gains. Tests show that AES-NI can be up to 13.5 times faster than traditional (non-accelerated) AES and uses about 90% less energy.

The work carried out in [

12] offers a preliminary evaluation of the encryption features in Oracle, MySQL, and PostgreSQL, focusing on encryption-at-rest and Transparent Data Encryption (TDE). It highlights that MySQL supports AES-256 for data-at-rest encryption. PostgreSQL, however, lacks built-in TDE support—except through EnterpriseDB—and relies on third-party tools like pgsql-hackers TDE, which require users to handle setup and maintenance themselves. The study also provides practical recommendations for initial implementation.

Dzer [

13]’s study focuses on enhancing query performance and privacy in relational cloud databases. This study introduces SecureSQL, a framework that combines AES-128 encryption with hash map indexing to optimize query execution on encrypted data. SecureSQL uses 20 of the 22 TPC-H benchmark queries efficiently and it outperforms conventional encrypted databases by reducing execution time without modifying the DBMS structure. The study enhances privacy-preserving database outsourcing while ensuring fast and scalable query execution for real-world applications.

Say and Dodla [

14] conducted a comparative analysis of Oracle and MySQL databases. They measured query execution times and scalability under TPC-H workloads using Apache JMeter to simulate transactional workloads. The study found that Oracle has lower and more consistent response times compared to MySQL, which shows high variability in response time. MySQL, while effective in lightweight and read-heavy scenarios, did not show the same consistency as Oracle, and therefore Oracle is considered to be more suitable for high-throughput and critical environments.

In [

15], Katsadouris examines encryption for secure databases. He compares order-preserving encryption (OPE) and fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), as well as searchable encryption, and discusses their implications for query efficiency and execution. The work examines secure designs for databases, including CryptDB, and mentions efficiency of trade-offs for encrypting queries. Results demonstrate the impact of encryption for storing, retrieving, and indexing data, where efficiency and security need to be balanced. This work uses the TPC-H benchmark to assess how encryption affects query performance in practical scenarios.

In [

16], Ansmink studies encrypted query processing in DuckDB by analyzing how encryption affects query execution time and storage efficiency and system performance. The research integrates Intel SGX with column-level encryption in DuckDB’s architecture, which produces an average 22% performance overhead. The system achieves a maximum compression benefit of 2.12× by implementing compression techniques. The study demonstrates that stronger encryption can affect performance and storage requirements.

Sidorov and Ng [

17] propose an improved Transparent Data Encryption mechanism for cloud-based DBMS, securing data in use and at rest. It improves security by encrypting active data during query execution. Unlike other encryption methods, this approach allows normal Structured Query Language (SQL) queries without modifications, ensuring usability, which is one of the goals of this study. Findings show that data-in-use encryption introduces minimal performance overhead, making it an effective security and usability solution.

The primary objective of the research conducted by Natarajan and Shaik [

18] is to evaluate the impact of Transparent Data Encryption (TDE) on the performance of CPU, RAM, and Input/Output (I/O) in Oracle databases (versions 19c, 18c, and 12c). The results of the study show that TDE uses nine times the amount of RAM compared to non-encrypted database configurations. In terms of percentage, non-TDE databases used between 10% and 16% of RAM, while TDE databases used between 83% and 90%, regardless of the Oracle version. The results show a clear trade-off between security and system efficiency, which is important when deploying TDE in production environments.

Hu and Klein [

19] applied an experimental benchmark using application-layer AES-256 encryption via Hibernate and Jasypt, migrating an e-commerce application (Business-to-Business marketplace) to the cloud. They measured the performance overhead of database transactions (insert, read, update, and delete), revealing significant penalties. Insert operations added a 4.5-fold increase in execution time, while read, update, and delete operations increased from 2 to 2.85 times. The main contributions include detailed evidence of TDE performance impact, guidance when selecting critical columns to minimize the overhead, and recommendations for adjusting service-level agreements (SLAs) and quality-of-service (QoS) parameters according to the cloud environments.

In [

20], Mattsson acknowledges TDE as a database-level encryption method, suitable for protecting data at rest by encrypting and decrypting data transparently within the DBMS. However, there are some limitations highlighted: TDE provides no protection against application-level attacks, since encryption occurs only at storage layer and decrypted data is exposed once accessed by the database engine. The paper also adds that TDE lacks support on accelerated index-search on encrypted columns, making it not optimal when query performance is required. These limitations are faced with hybrid solutions that combine software-level encryption with hardware-based key protection, which the author finds to be more flexible and better performing.

Some work has been performed using transparent data encryption features. Shmueli et al. [

21] analyzed five database encryption architectures and identified the trade-offs between performance, transparency, and security. The authors proposed a novel “above-cache”, which takes place at the encryption module inside the DataBase Management System (DBMS), just above the cache layer. This approach allows cell-level encryption with minimal performance overhead and transparency to the application layer. Four different encryption models were implemented and tested, including this new approach, and when comparing them to each other it was found that above-cache model outperformed others in realistic cache scenarios. The study proves that strong security and performance can coexist through strategic DBMS-layer integration.

Another relevant study carried out by Colbert and Juliano [

22] compares the performance of Transparent Data Encryption (TDE) in SQL Server and Encryptionizer from NetLib, both of which use AES-128. Tests were run on three environments—including virtual and non-virtual machines—evaluating five key operations like insert, update, and backup. Results showed that Encryptionizer outperformed TDE, especially in non-virtual setups, with 17.2% faster execution, while TDE showed an average 25.2% slowdown compared to unencrypted systems. Although it did not use standard benchmarks like TPC-C or TPC-H, the study relied on a custom method to reduce noise and provide balanced results. It highlights how the choice of encryption tool can significantly affect performance in enterprise settings.

A recent study by Bărbulescu et al. [

23] compares the performance of Oracle Database Server and Microsoft SQL Server, particularly focusing on encryption performance. The study examined the execution times of AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256 on both platforms. The study revealed that, when using AES-128, SQL Server outperforms Oracle Database Server in encryption and decryption operations. Additionally, the study revealed that selecting the AES-128 encryption algorithm resulted in performance overheads of approximately 22% for Oracle and 28% for SQL Server.

Our study uses the TPC-H benchmark to simulate realistic query loads with different key lengths to perform a direct comparative analysis of AES encryption performance across Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server.

Table 1 summarizes the key findings from the related work mentioned earlier. It lists the databases and algorithms used, as well as the main findings and citation number. The table highlights how encryption impacts performance across different DBMS.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the tools used to evaluate the impact of encryption on databases, including the experimental environment, the TPC-H benchmark, the databases, the performance metrics, the AES encryption algorithm, and the TDE process.

3.1. Experimental Environment

Three virtual machines were used in the experiments. Each virtual machine had its own operating system, Windows 10 Pro, which had 16GB of RAM, an Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2660 v2 @ 2.20GHz, and at least 100GB of storage. For this study, Microsoft SQL Server 2022 (version 16.0.1130.5 (X64)—RTM-GDR (KB5046057)) was installed in Developer Edition on one of the virtual machines. The 8.0.38 community version and the 9.2.0 enterprise version of MySQL were installed on another virtual machine. To evaluate Oracle, the 19c Enterprise Edition, version 19.3.0.0.0, was installed on one of the three machines. The purpose of these virtual machines was to isolate noise from other processes and produce clearer results, creating a dedicated testing environment. The virtual machines ran on a VMware ESXi cluster consisting of three Dell servers with identical hardware. Each host was equipped with an Intel® Xeon® E5-2670 v3 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 64 GB of RAM, and enterprise-grade storage. The E5-2670 v3 supports AES-NI, which provides hardware acceleration for AES. This ensured that all TDE and decryption operations in our experiments were executed with native hardware support.

3.2. TPC-H

The popular TPC-H benchmark was selected to evaluate the performance of algorithms executed on different database platforms. It is widely used for database and query performance comparisons [

24]. We performed a performance evaluation using TPC-H with different Scale Factors (SF) [

25]. We evaluated the scalability of 100 MB (SF = 0.1), 1 GB (SF = 1), and 10 GB (SF = 10) datasets by executing all TPC-H queries. This allowed us to assess the performance of the selected databases and encryption algorithms. Three executions were run: the first used a baseline without concurrent workloads to avoid potential variations in execution time and measure query execution under optimal conditions. This execution is called Powertest [

24]. The following two executions are called Throughput [

24], which evaluates the system’s performance by simulating a more realistic workload. This provides insight into the system’s scalability and whether it can maintain the same performance without significant variations in execution time or system resource usage. The Powertest is the cold start, which has no data plans or execution plans in memory, so it does not have any record of any past execution to make sure the execution times are unaffected by cache, reflecting the raw I/O and optimization costs, without any variation. The Throughput is defined by two executions with different query orders, which inherit the warm plan cache from the Powertest. By changing the order of the query executions, it avoided the repeated hot-spot contention, reducing time variations, reflecting realistic, concurrent workloads, minimizing the cache-induced noise, taking advantage of I/O and CPU parallelism [

26].

3.3. Databases Used

This paper evaluates the encryption performance of the top three databases, as rated by the DB-Engines 2025 ranking: Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server. The ranking provides an evaluation of databases according to their popularity, reflecting robustness, support, and widespread adoption in enterprise organizations and academic environments [

27,

28,

29]. These databases were also chosen due to their support of TDE and the same encryption algorithms [

30,

31] as well as their recognition across different industries and academic research [

32,

33].

The Oracle Corporation created the Oracle database in 1979. According to the DB-Engines 2025 ranking, it is the leading relational database management system [

27]. The database system supports SQL and Procedural Language/SQL (PL/SQL) programming languages and provides strong reliability features and extensive scalability options [

34]. The system provides robustness and scalability features with support and advanced features. Oracle provides multiple editions which differ in their licensing requirements. The Oracle Database Express is free, while the Oracle Personal Edition requires a license, and the Enterprise Edition and Standard Edition 2 require a license for their use [

34]. The Express Edition supports only one CPU, 1 GB of RAM, and up to 11 GB of user data, without access to advanced features or security options. Standard Edition 2 is a licensed edition for small to medium applications, limited to two CPU sockets and 16 threads, and excludes most enterprise features like TDE or Oracle Data Guard. Enterprise Edition is the most complete and scalable edition, supporting all advanced database options, security features (e.g., TDE, Data Redaction, Database Vault), Real Application Clusters, and Oracle Management Packs. Personal Edition is a single-user licensed edition intended for development use, with the same features as Enterprise Editions, except for Real Application Clusters (RAC) and management packs, and is available only for Windows and Linux. In this project we used Oracle Database 19c Enterprise Edition Version 19.3.0.0.0.

MySQL is an RDBMS that allows for storing, managing and accessing large volumes of data efficiently. It was developed originally by MySQL in 1995 and is the property of the Oracle Corporation. MySQL uses SQL, which is the common language used to interact with relational databases [

14]. In this project, MySQL version 8.0.38 Community Server and MySQL version 9.2.0 Enterprise Server were used. MySQL has a free version called Community Edition, which has an Enterprise Edition with additional functionalities and support, but it requires a commercial license, although it is free for students to use. Additionally, MySQL offers Cluster Carrier Grade Edition (CGE), a highly available version designed for telecom and real-time applications, which is also commercially licensed. MySQL can be used in different operating systems, such as Linux, Windows and macOS, making it flexible and easily implemented [

14,

35,

36]. Both MySQL 8.0 Community and 9.2 Enterprise editions support Transparent Data Encryption (TDE) using AES-256 through InnoDB tablespace encryption. The Community Edition relies on the keyring_file plugin for local key storage, while the Enterprise Edition introduces the component-based keyring architecture (component_keyring_file.dll) with improved key rotation and management integration. We have included both editions in order to compare these implementations and assess the impact of the enhanced keyring management in the Enterprise Edition on performance.

Microsoft Corporation developed SQL Server, which is an RDBMS. SQL Server is a product that can be run on Windows and Linux operating systems, and you can also integrate it with Azure Services. It supports SQL and other advanced data security features, such as encryption, data masking, and row-level security. SQL Server is used for academic purposes or enterprise applications with Enterprise, Standard, Web, Developer, and Express versions [

37]. In this project, SQL Server version 2022 Developer Edition was used.

3.4. Performance Metrics

Performance metrics were collected using Performance Monitor, used to track and analyze real-time statistics. Within this tool, we specifically used the “% Processor Time” counter, which tracks the percentage of time the CPU spends executing active (non-idle) threads. Memory usage was analyzed using the “Available Mbytes” counter, reflecting the amount of free physical memory, which helped to identify memory pressure during query execution. Disk activity was recorded using the “% Disk Time” counter, indicating how busy the disk was during the query execution. The Windows Performance Monitor counters used (e.g., % Processor Time, Available Mbytes, and % Disk Time) provide only a rough estimate and can overstate utilization on multicore systems. This is because they occasionally report values above 100% due to overlapping or aggregated I/O operations.

3.5. Advanced Encryption Standard

There was a need to substitute the DES and 3DES in 1997 to create an algorithm with better security and efficiency, and the AES was the next in line. Rijndael is a family of ciphers developed by Vincent Rijmen and Joan Daemen that was selected by NIST as the official Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) in 2001 [

38].

AES is a symmetric key, meaning the sender and receiver use the same key on the Symmetric Key to encrypt and decrypt. The Symmetric Key, also known as Secret Key Encryption, is easy to use but lacks security when the key is shared between the sender and receiver. The message can be decrypted if someone intercepts the key [

39].

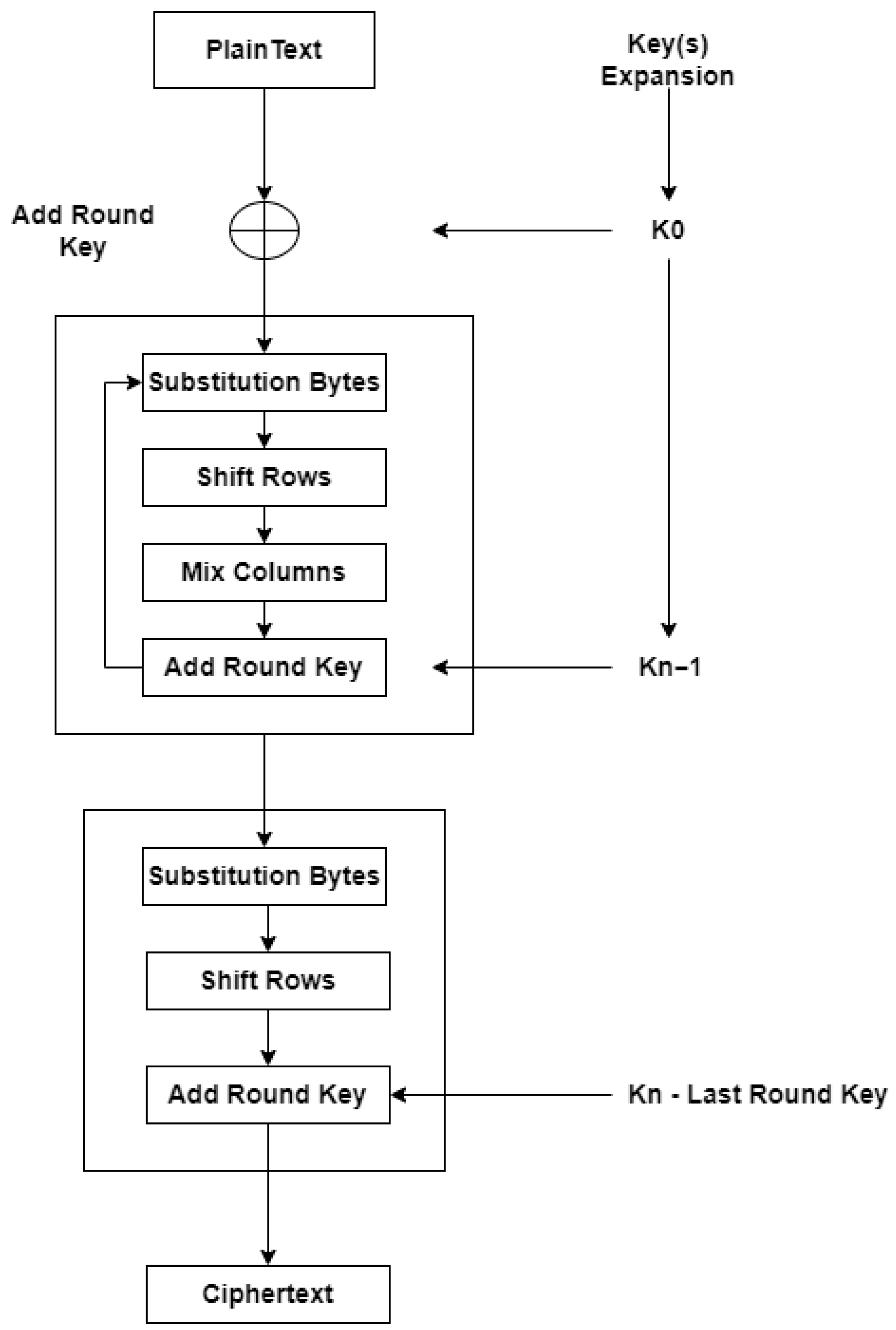

The key length can be 128 bits, 192 bits, or 256 bits, and the number of rounds will depend on the number of bits. If the key length is 128 bits, it will have ten rounds; if it is 192 bits, it will be twelve rounds; and if it is 256 bits, the number of rounds is fourteen. All sub-processes in the encryption process use a matrix of 4 × 4, and instead of working with bits, AES works with bytes, so that 128 bits make up 16 bytes in a matrix of 4 × 4. AES has four steps, except in the last round, where the mix columns are unnecessary [

5,

40], as stated in

Figure 1.

3.6. Transparent Data Encryption (TDE)

Transparent data encryption is a security feature to ensure data-at-rest security in database platforms. TDE works automatically when enabling TDE, encrypting the data stored in the database files, such as tablespaces or data files, without requiring any function to decrypt the information when accessing or any function to encrypt when inserting. This process is called “transparent” because it does not require any changes to SQL queries or database schema, making the user experience seamless for users and developers. This encryption guarantees that the data files will remain protected if they are stolen or accessed [

3]. TDE is present in many database platforms, offering different encryption algorithms to be used with TDE.

TDE was introduced by different DBMSs to address the requirements associated with public and private privacy and security mandates such as Payment Card Industry (PCI) [

41]. TDE was built in different DBMSs individually, as each of the vendors created their transparent data encryption separately as a feature. Oracle introduced TDE in Oracle Database 10g Release 2, initially focusing on column-level and later expanding to tablespace-level encryption in Oracle Database 11g Release 1 [

41]. Microsoft incorporated TDE into SQL Server 2008, providing full database capabilities. Microsoft has not publicly given credit for the creation of TDE to specific individuals. Its development was part of new developments in SQL Server 2008 to improve data security and compliance [

31,

42]. MySQL transparent data encryption version was introduced as part of the MySQL Enterprise Edition in version 5.7.12 by the MySQL team at Oracle [

43].

In SQL Server it is possible to enable and disable the transparent data encryption [

31]; in MySQL the tablespace itself is encrypted, meaning that everything stored in the tablespace is encrypted and disabling and enabling is not allowed [

30]; and in Oracle the tablespace is encrypted and it is possible to rotate the algorithm encryption on the tablespace, so in this case it is possible to change AES among the available key sizes, and once a table is moved inside the encrypted tablespace, the table is automatically encrypted [

44]. Each DBMS implements AES differently. For example, SQL Server uses AES in CBC mode with a random initialization vector per page, while Oracle TDE uses either AES-CBC or AES-OFB, depending on the version and wallet configuration. MySQL InnoDB tablespace encryption, on the other hand, uses AES-256 in CBC mode with per-page IVs and key rotation support. Differences in padding and page-level encryption may influence I/O and caching behavior, which can contribute to variations in performance.

3.7. Encryption Process

In this section, we present the encryption processes of Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server that secure the data. All databases support TDE, which was used in the experiment to avoid changing the application layer by ensuring the data is encrypted at rest.

3.7.1. Encryption in MySQL Using Tablespace Encryption

MySQL supports TDE at the tablespace level, which is available with MySQL Enterprise Edition and the Community Edition. This experiment used tablespace encryption to encrypt data in MySQL’s InnoDB tables. To enable encryption, the following steps have been followed:

For MySQL Community Edition version 8.0.38, first, it was necessary to enable the keyring plugin, in this case the plugin keyring_file, which stores the encryption keys outside of the database tables, “early-plugin-load=keyring_file.dll keyring_file_data=‘place where keyring is installed’”; these commands are being executed in the my.cnf file, during server startup, which is in the installation folder and is executed to make the plugin available for the user to apply encryption to a tablespace.

Second, when wanting to encrypt a tablespace, this is the command to apply: “CREATE TABLESPACE tpch_tde ADD DATAFILE ‘tpch_tde.ibd’ ENCRYPTION=‘Y’;”. When creating a table under this tablespace, the table will automatically inherit the encryption settings from the tablespace. However, it is necessary to mention the tablespace name during table creation, where the user must use this command “TABLESPACE ‘tpch_tde’”.

In MySQL Enterprise Edition version 9.2.0, encryption is not enabled using the traditional my.cnf configuration file, as it is in the MySQL Community Edition. Instead, a manifest.json file is created to define which components should be loaded, for example, component_keyring_file.dll, which is located in the data folder under the MySQL folder in the ProgramData directory:“{“components”:”C:\Program Files\MySQL\mysql-commercial-9.2.0-winx64\lib\plugin\component_keyring_file.dll”}”. After that, two other files are created, one in the plugin folder, which is responsible for giving the path to where the component keyring will be placed, which is called the local file and has this content: “{“path”: “/usr/local/mysql/keyring/component_keyring_file”, “read_only”: false}”. The other file is the global file that tells the system to read the local manifest: “{“read_local_manifest”: true}”.

In the shared environment, encryption may burden the system more under high I/O load conditions. Therefore, benchmarks have been repeated to measure performance degradation due to encryption under various system conditions. Although AES supports multiple key sizes, MySQL’s tablespace encryption and TDE configuration only expose AES-256, with no available or documented support for AES-128 and AES-192 in the tested versions.

3.7.2. Encryption in SQL Server Using TDE

In SQL Server, TDE performs encryption on a whole-database level. TDE allows for the encryption of not only data files but also log files. This way, all information that rests on the disk will remain encrypted. Encryption in SQL Server takes place in the following steps:

In this experiment, TDE was applied to SQL Server to encrypt the whole database. This means that the data at rest is kept safe. The establishment and configuration of TDE involve a few essential steps that establish and secure a hierarchy of encryption mechanisms. This makes the data in the database and transaction logs encrypted, and none of this sensitive information can be accessed by unauthorized sources, even in those cases where the physical files are compromised.

First, encryption starts with master key creation. This master key becomes pivotal in securing the encryption infrastructure of SQL Server. The master key is stored in the master database and encrypted by a password. It plays a highly protective role in safeguarding the other components of encryption that come afterwards. Without this master key, the initialization of the database encryption mechanism cannot be performed.

Once the master key is created, the following procedure creates a certificate. The certificate also resides within the master database. It encrypts the Data Encryption Key (DEK), which will encrypt the database’s actual data. The certificate protects the DEK so that even though the database files are accessed, the data therein remains unreadable without the certificate.

Once the certificate is obtained, a Database Encryption Key (DEK) is generated within the database, which encrypts the actual database, including the main data files and the transaction logs. The DEK uses the AES encryption algorithm, one of today’s most robust and used standards, since it presents the best balance between security and performance. Once the DEK is generated, it is wrapped by the previously created certificate, adding an extra level of protection.

Finally, encryption is activated at the database level as TDE with the DEK in place. TDE is activated by informing the SQL Server to SET ENCRYPTION ON for the database.

From now on, any data written to disk in the main database file or the transaction logs is encrypted using the DEK. Encryption is transparent, requiring no changes to the application or user queries. Data are automatically encrypted as they are written to disk and decrypted as they are read into memory.

Along with encrypting the database, TDE also encrypts the log files. Any backups created from this encrypted database will also be automatically encrypted. This becomes an important security measure for those scenarios where the backups may need to be stored off-site or in environments where unauthorized access could be an issue. If compromised, these encrypted backups ensure the data remains protected. Performing steps in reverse when turning encryption off may be necessary, including the removal of the associated keys and certificates. In this case, encryption needs to be turned off first, which will already accomplish turning TDE off and stop automatic data encryption. Once encryption is turned off, the DEK can safely be dropped from the database. Once the DEK is removed, the self-signed certificate used to protect the DEK is no longer needed and can be dropped from the master database. Finally, once the certificate has been dropped, the master key can be removed, entirely removing the encryption infrastructure.

3.7.3. Encryption in Oracle Using TDE

TDE is a feature that encrypts data at rest, thereby protecting sensitive information stored in tablespaces and columns. This ensures that, even if the database files are accessed outside the Oracle environment, the data remains unreadable.

To encrypt a tablespace, it was first necessary to follow some steps to make it possible to have encryption ready to use in the database engine.

Oracle requires a wallet, which is a secure location for storing the TDE master encryption key. Before that, it is necessary to set the environment variables, initialize the keystore, and create it. Once this setup is complete, it becomes possible to create an encrypted tablespace and to rotate the encryption key periodically, replacing the existing key with a new one. This improves cryptographic security and, if desired, allows us to apply a new AES key size during the rekeying process. First, it is necessary to specify the directory in which the Oracle database binaries are installed by setting the environment variable ORACLE_HOME in the command line (e.g., set ORACLE_HOME=C:\oracle19c). Normally, Oracle uses a binary “spfile” to read the settings at startup, so we created a pfile “CREATEPFILE=‘…/admin/orcl/pfile/orcl-2023-08-14.ora’”; this file had all parameters in the settings. This step is not required for TDE, but it is good Database Administrator (DBA) practice. After this we are ready to create the wallet, a secure container for the master encryption key “ADMINISTER KEY MANAGEMENT CREATE LOCAL AUTO_LOGIN KEYSTORE FROM KEYSTORE ‘C:\oracle19c\admin\orcl\WALLET\TDE’ IDENTIFIED BY “your_wallet_password”;”, and then it is ready to create encrypted tablespaces “CREATE TABLESPACE tde_secure_tbsp DATAFILE ‘…\oradata\ORCL\tde_secure1.dbf’ SIZE 15G ENCRYPTION USING ‘encryption_algorithm’ DEFAULT STORAGE(ENCRYPT);”. If we want to change the encryption key of the tablespace, it is necessary to rotate the encryption key on the tablespace, using the alter command, ALTER TABLESPACE tde_secure_tbsp ENCRYPTION ONLINE USING ‘encryption_algorithm’ REKEY.

3.8. Automated Data Extraction and Multi-Query Execution Management with Python

This sub-chapter explains the Python 3.13.7 script created to generate a script to be executed in each of the database platforms and the data extraction script to cycle through the execution times extracted from the respective database platforms’ console output and convert them into a Comma-Separated Values file (CSV).

The TPC-H already has a list of execution queries arranged in specific orders for testing purposes. To maintain consistency, these functions are already prepared to rearrange the order to match the values to the respective query number. However, the queries must be executed in the exact order specified by the TPC-H benchmark.

3.8.1. Multi-Query Execution Management with Python

To execute multi-query executions, it was necessary to build functions which could return a script that could execute the queries in one execution called Powertest and run multiple executions called Throughput. We built scripts for MySQL, SQL Server, and Oracle because the syntax in either one or another is different, and some changes are necessary to run without errors. The functions for SQL Server were ReturnThroughputTest() and ReturnPowerTest(). The functions for MySQL were ReturnMySQLThroughputTest() and ReturnPowerTestMySql(). The functions for Oracle were ReturnThroughputTestOracle() and ReturnPowerTestOracle(). These functions can be found in

https://github.com/marcioaccarvalho/aes-encryption-db-query-performance.git (accessed on 30 September 2025) for reference.

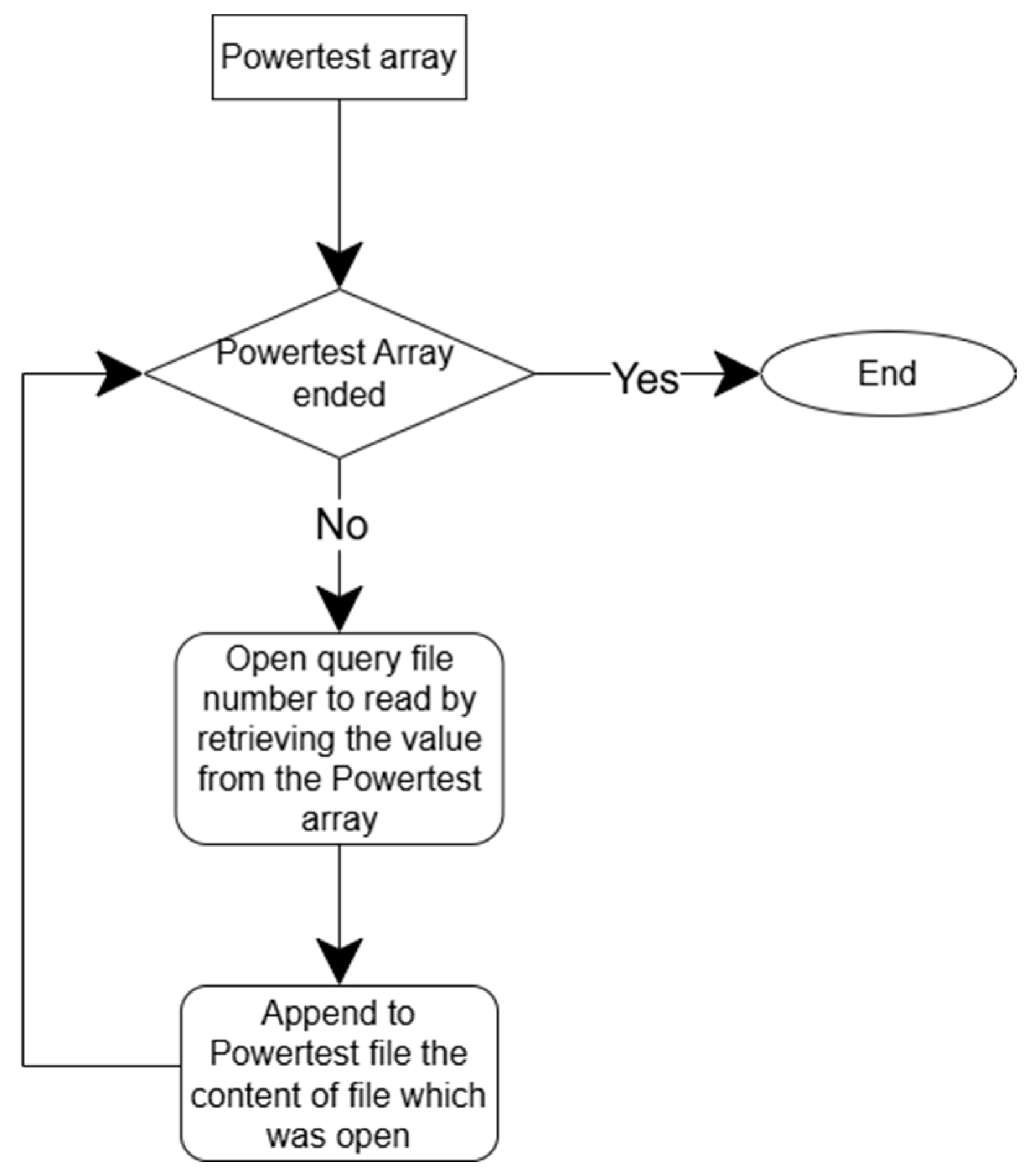

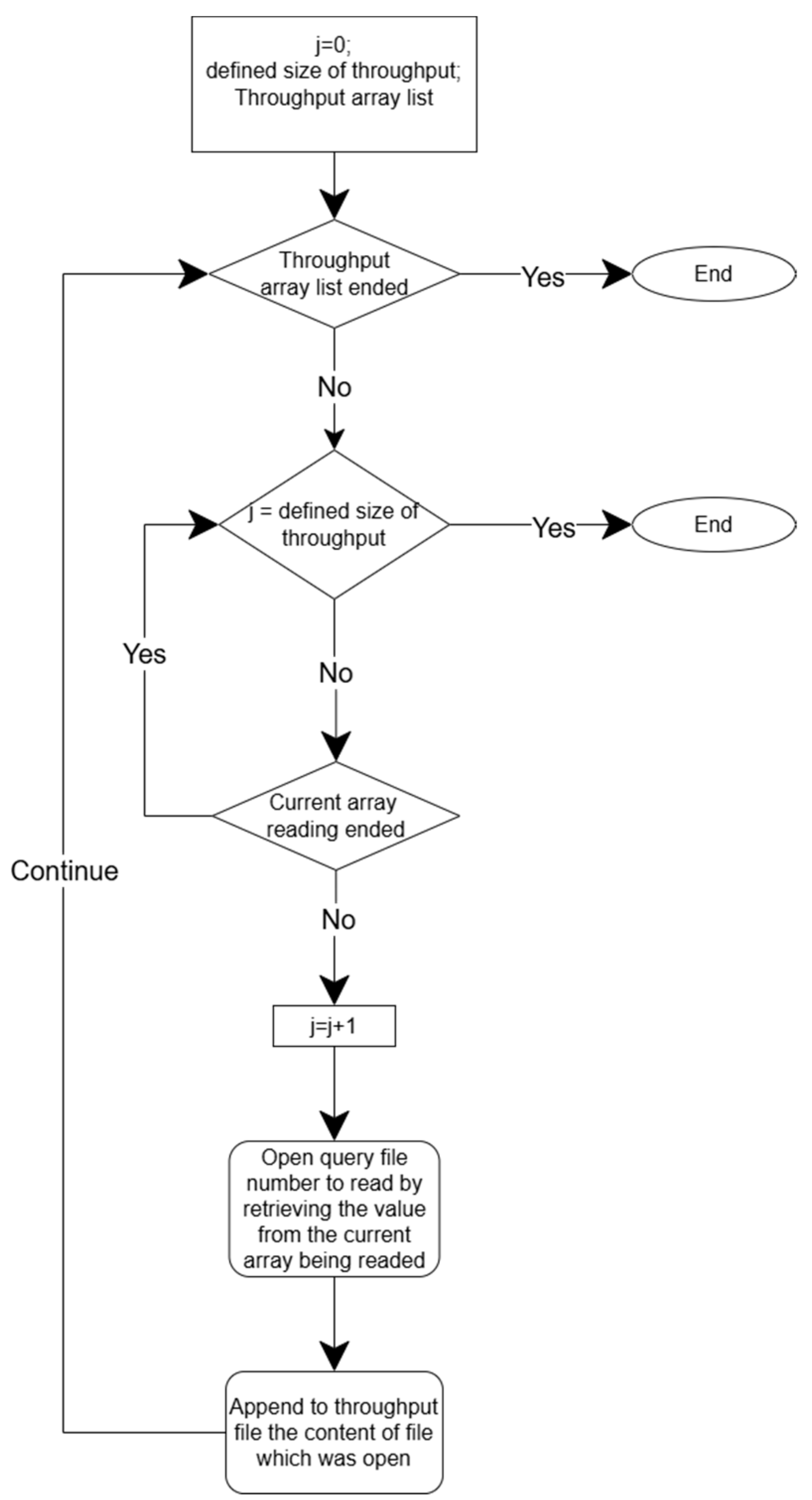

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show a generalized fluxogram that illustrates how the developed code works, respectively, to build the Powertest script with the correct order of queries and to build the Throughput script with the correct order by execution array number and by query number.

ReturnThroughputTest() prints at the beginning “SET STATISTICS TIME ON;” to activate printing to the console of the elapsed time of each query. To disable it, “SET STATISTICS TIME OFF;” is printed at the end of the script. To make it possible when performing data extraction to see when an execution of 22 queries starts, “ThroughputTest-X-begin” is printed, and when an execution finishes, “ThroughputTest-X-end”. This occurs for each execution cycle. To identify the extracted query number, the query “Query X-Begin” is printed before the execution, and after the execution of the query, “Query X-End” is printed (the X indicates the query number).

ReturnPowerTest() is the same as ReturnThroughputTest(), where it prints the line of code to enable printing to the console of the elapsed time of each query, and at the end of the script, it disables the printing of the elapsed time for each new execution. To start the Powertest and to identify when the data extraction of the Powertest result begins, “PowerTest-X-begin” is printed. To identify each query to extract the elapsed time, “Query X-Begin” is printed before the query execution, and after the execution, “Query X-End” is printed. The Powertest script finishes with “PowerTest-End”, and the statistics are disabled.

ReturnMySQLThroughputTest() does not do prints; it uses comment markers to organize and label the script for readability. This function’s purpose is to create a MySQL script containing the specified number of executions, where in each execution, there are 22 queries in the respective order for the respective execution number.

ReturnPowerTestMySql() is the same as ReturnMySQLThroughputTest(). However, it just appends to the script the first execution, with the 22 queries in their respective order and the comment markers used to organize and label the script for readability.

ReturnThroughputTestOracle() prints at the beginning the variable setOracleStatis-ticsOn, which contains the code to print the elapsed times of each query, the code to redirect the execution times to a text file, and the date time of when the script execution started. To disable and close the printing to a text file, the setOracleStatisticsOff variable is printed. This function also appends the queries to the specified number of executions, which in each execution is 22 queries in the order corresponding to the respective execution number.

ReturnPowerTestOracle() is the same as ReturnThroughputTestOracle(). However, it just appends to the script the first execution, with the 22 queries in their respective order and the comment markers used to organize and label the script for readability.

3.8.2. Automated Data Extraction with Python

To extract the execution data times from the text file (first, there was the need to copy the output from the console to a text file), a script was developed to handle Powertest and Throughput files. The function to extract the Powertest and Throughput from SQL Server were ConvertValuesToExcelPowertest() and ConvertValuesToExcel(), respectively; the function to extract MySQL Powertest and Throughput were ConvertValuesMySQLToExcelPowertestTeeVersion() and ConvertValuesMySQLToExcelThroughputTeeVersion(), respectively; and the function to extract Oracle Powertest and Throughput were ConvertValuesOracleToExcelPowertest() and ConvertValuesOracleToExcelThroughput(). These functions can be found in

https://github.com/marcioaccarvalho/aes-encryption-db-query-performance.git (accessed on 30 September 2025) for reference.

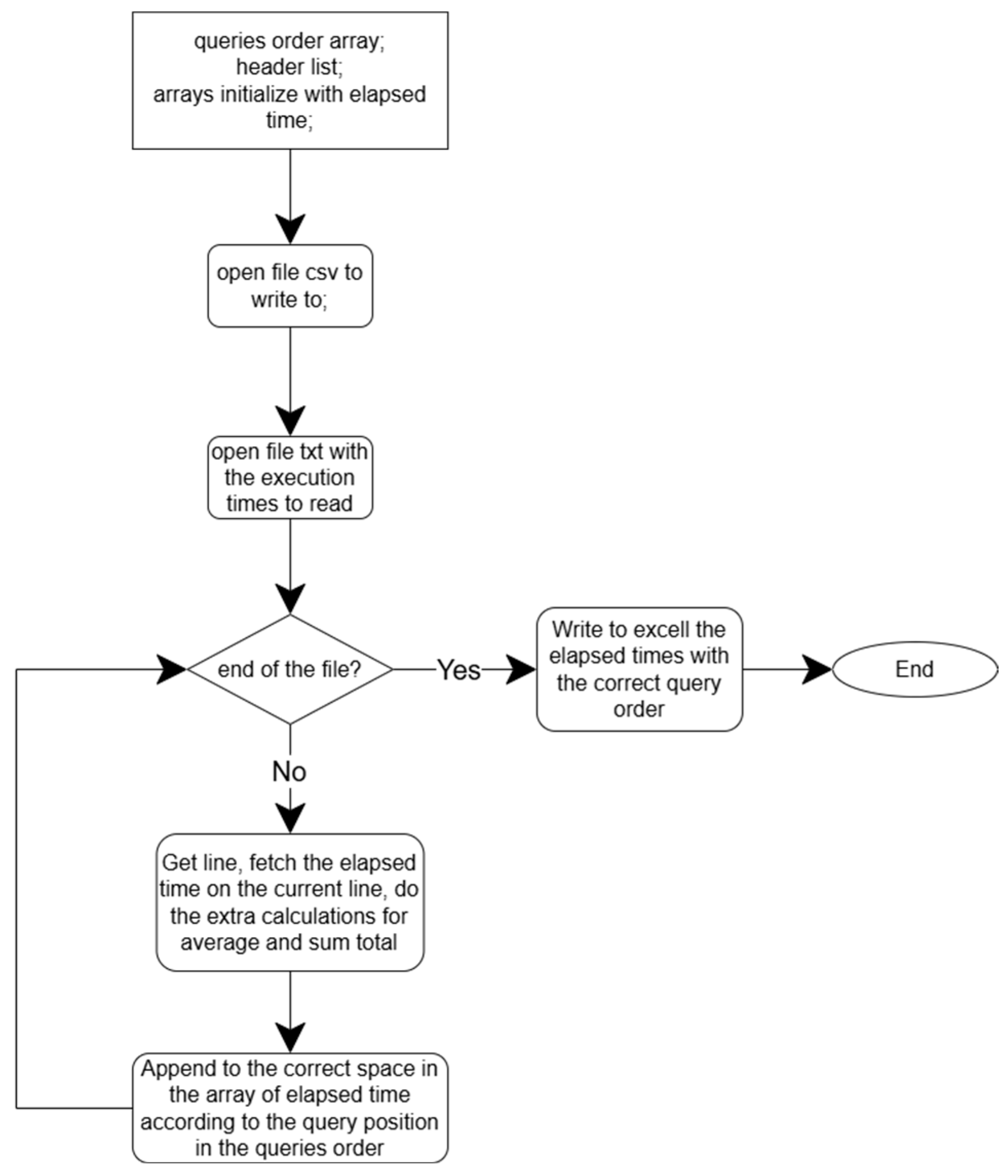

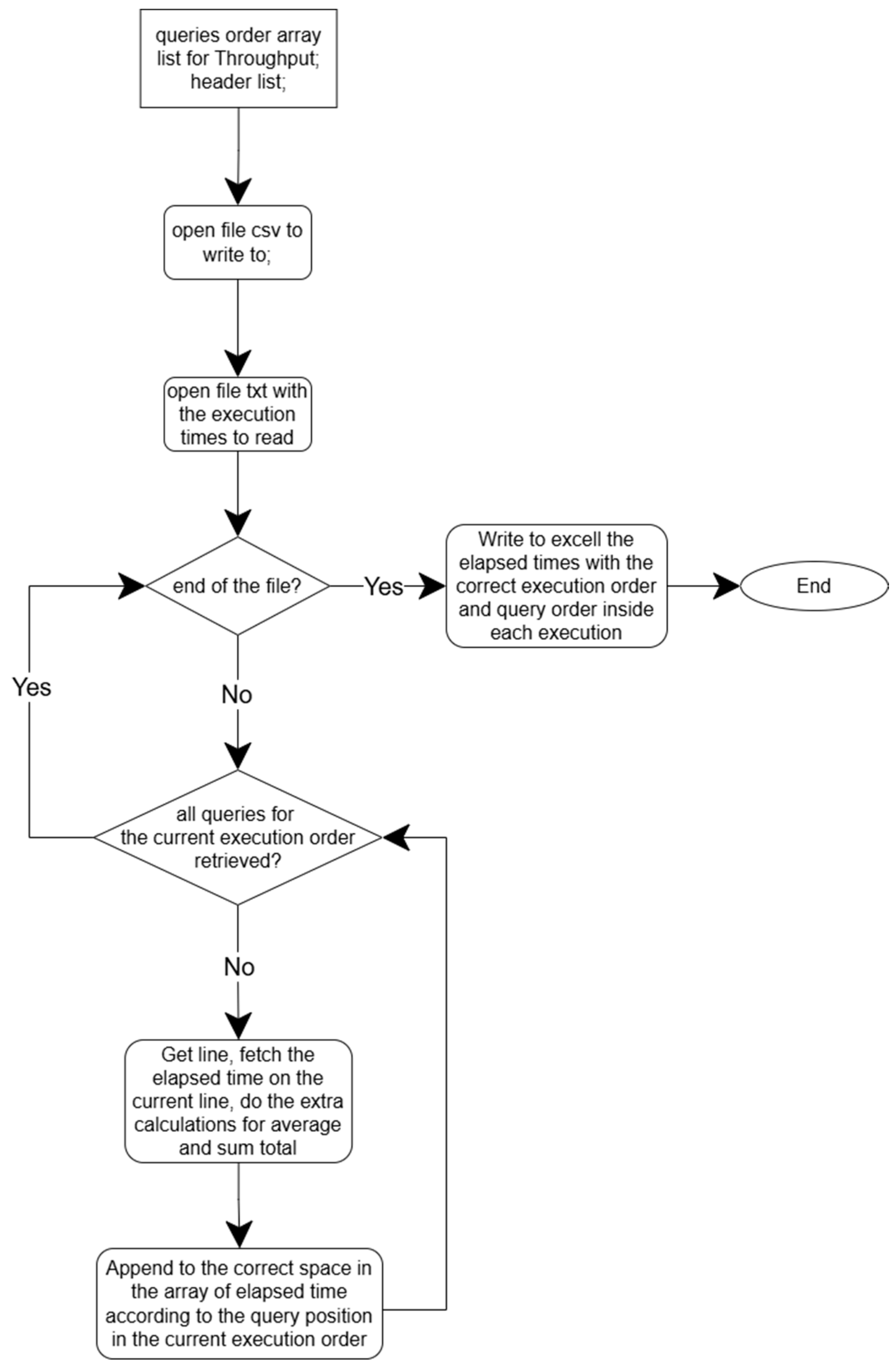

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show a generalized fluxogram that illustrates how the code works to convert the Powertest and Throughput text files to Excel with the correct order of elapsed times by execution array number and query number, respectively, as designed by TPC-H [

24].

ConvertValuesToExcel() processes the Throughput Test results from the SQL Server console. It reads line by line, looking for “throughputtest”, which indicates a new execution is starting, extracting the elapsed time for each query from Query 1 to Query 22. After finishing each execution, there is a calculation for the total and average of the respective execution. After obtaining all the arrays with each execution, they are written in the CSV file for each array.

ConvertValuesToExcelPowertest() processes the Powertest results from the SQL Server console by reading line per line as the function to extract the Throughput Test; the difference is that it will read only one execution of 22 queries. When reading line per line, it looks for “powertest” and “begin” to know when the execution starts and extracts the elapsed times until it finds “end”, which means that the execution is finished.

ConvertValuesMySQLToExcelPowertestTeeVersion() processes the Powertest results from the MySQL console by reading line per line trying to find “row in set”, “rows in set”, or “Empty set”, which indicates that there is a line to extract elapsed time, or in the event of it being an empty set, it is because there was no time to be extracted. When the script extracts an execution time from that line, it converts the time from seconds to milliseconds (ms). The specific position is inserted in an array of the respective query to have an exact order in Excel according to the query number. At the end of cycling through the text file, the total and average for all queries are calculated, providing a summary of execution times.

ConvertValuesMySQLToExcelThroughputTeeVersion() processes the throughput test results from the MySQL console by reading line per line, using the same formula as ConvertValuesMySQLToExcelPowertestTeeVersion(). However, in this case, it creates additional arrays that handle multiple query executions.

ConvertValuesOracleToExcelPowertest() processes the Powertest results from the Oracle console by reading line per line trying to find the “Elapsed“: extracting times in the format hh:mm:ss. When the script extracts an execution time from that line, it converts the time to ms using this formula “elapsed_time_ms = (hours * 3600 + minutes * 60 + seconds) * 1000”. It is inserted in an array in the specific position of the respective query to have an exact order in Excel according to the query number. At the end of cycling through the text file, the total and average for all queries are calculated, providing a summary of execution times.

ConvertValuesOracleToExcelThroughput() processes the throughput test results from the MySQL console by reading line per line, using the same formula as ConvertValuesOracleToExcelPowertest(). However, in this case, it creates additional arrays that handle multiple query executions.

4. Results

Table 2 summarizes the experiments and metrics used to compare the performance of the queries, including the total execution time of the 22 queries and resource usage. The Scale Factor represents the size of the dataset used in the benchmark, with “S0.1” corresponding to 100 MB and “S1” to 1 GB. The database platform refers to the environment where the queries were executed. At the same time, the test number indicates the iteration of the query executions. The encryption algorithm column specifies which algorithm was applied in each case.

Execution time is measured as the cumulative time, in milliseconds (ms), to run all 22 queries. CPU usage is monitored using the Windows Performance Monitor, specifically the “% Processor Time” counter, which tracks the proportion of time the CPU spends executing non-idle threads. Memory usage is observed using the “Available Mbytes” counter, reflecting the amount of physical memory available for system use, helping to determine if additional memory might be required. Disk usage is recorded using the “Disk Time Percentage” counter, indicating how busy the disk is during the query executions.

This detailed evaluation provides a thorough understanding of the relationship between encryption performance and the database management system’s underlying resource usage.

The following is a breakdown of the results based on different factors and encryption configurations.

SQL Server for Scale Factor 0.1 shows that AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256 perform better than the no-encryption option. This may suggest inefficient memory management for the no-encryption setup or reflect the high variability often observed at small factors like 0.1.

Table 2 shows that non-encryption requires 27.37% more memory than the average of encrypted results. Future studies could investigate Disk, CPU, and RAM usage on a per-query basis to identify which queries could have caused the non-encryption setup to underperform. This can give another perspective on how the system deals with multiple queries and which ones can impact the execution time performance.

At Scale Factor 1, no-encryption execution took 19,035 ms, which represents a 2.45-fold increase, or a 145.17% increase compared to Scale Factor 0.1, along with a decrease in RAM usage of about 8.45%. The disk usage remains consistent on average across the Scale Factor, with a decrease of 36% compared to Scale Factor 0.1. Calculating the execution query time overhead when moving from Scale Factor 0.1 to Scale Factor 1 gives a 2.45-fold increase in the non-encrypted database. The expected result was a 10-fold increase, because the size from Scale Factor 0.1 to 1 increases 10-fold, indicating that the performance remains relatively efficient and does not degrade when scaling.

At Scale Factor 10, in terms of total execution times, the Encryption algorithms underperformed against no-encryption as expected, but AES-192 slightly outperformed AES-128 by 0.95% overhead, which was not expected to happen, and likely reflects a combination of hardware-level optimizations and resource management differences at higher loads. Calculating the execution times overhead when moving from Scale Factor 1 to Scale Factor 10 gives an increase of 8.37-fold in the non-encrypted database, aligning with expectations. This increase suggests that, although performance scales with data size, it begins to stabilize as the scale grows, with potential for underperformance, taking much more time than expected to query from Scale Factor 10 to Scale Factor 1, for example. Future studies with a higher Scale Factor, such as Scale Factor 100, could explore this affirmation and explore the impact on system resources.

In conclusion, the analysis of the SQL Server results shows that the overhead between Scale Factors was expected when scaling. There is better performance when comparing Scale Factor 1 to Scale Factor 0.1. More scaling is needed to see proper results, because unexpected results can be seen when comparing encryption algorithms against a no-encryption baseline. This could suggest a lower Scale Factor for comparison or poor memory management, as well as CPU and RAM usage, as seen in the Scale Factor where no encryption needs 27.37% more memory to query. When assessing performance among Scale Factors, AES-192 shows the most consistent performance at Scale Factor 0.1 and Scale Factor 10, but AES-128 is slightly better at Scale Factor 1. Overall, AES-192 is the recommended choice for SQL Server because it shows to be efficient across the different Scale Factors.

For MySQL at Scale Factor 0.1, AES-256 was approximately 2× faster than the no-encryption setup, meaning that no-encryption takes twice as long to execute AES-256. This can be attributed to high disk usage in the no-encryption setup, which used approximately 529.7% more disk time than AES-256. As disk usage increases, the system spends more time on disk reads, creating I/O bottlenecks that likely slow down query performance.

At Scale Factor 1, AES-256 takes slightly longer to execute than the no-encryption setup. With an overhead of 1.04×, meaning 4.22%. Scaling makes it possible to see a more stable performance when querying encrypted databases. Testing at even higher Scale Factors could reveal whether encryption performance improves compared to no-encryption.

Overall, SQL Server seems better equipped to handle complex queries and large datasets across different Scale Factors. At the same time, MySQL, using TDE AES-256, tends to underperform at higher Scale Factors compared to the no-encryption baseline, although it might outperform no-encryption in smaller Scale Factors. Based on the results, TDE AES-256 in MySQL may not be recommended for optimal performance. At a small scale, factors such as a scale of 0.1 sometimes resulted in encryption appearing faster than non-encryption. These results are probably due to caching effects and low I/O contention. Such cases do not represent genuine cryptographic acceleration but rather transient cache and I/O noise. Larger Scale Factors, such as Scale Factor 1 and Scale Factor 10, exhibit the expected patterns of encryption overhead.

For Oracle at Scale Factor 0.1, no-encryption had slightly better execution time compared to AES-192 with 8903 ms of execution time and AES-256 with 9017 ms of execution time, and showed significantly lower disk usage. AES-192 used approximately 4261% more disk, and AES-256 about 213% more, compared to no-encryption. While no-encryption had a lower disk usage, it consumed more RAM than both AES-192 and AES-256, showing potential inefficiencies in memory handling. AES-192, despite offering stronger encryption and being slightly better than the rest of the key sizes, showed a heavy dependency on disk I/O, which can negatively affect the performance under heavier workloads.

For Oracle at Scale Factor 1, AES-256 showed better performance than the other encryption algorithms and AES key sizes, reducing execution time by 19.93% compared to AES-192 and by 24.07% compared to AES-128. Even though no-encryption had the best performance overall compared to the encrypted test cases, it showed a higher disk usage with an average of 73.19% compared to only 31.02% with AES-256. CPU utilization was most used under AES-128 with 32.21%, close to the no-encryption scenario with 31.88%, whereas AES-192 required less CPU, with 19.06% usage. AES-256 was the best encryption algorithm key size, balancing the resource usage and offering strong encrypted data and a stable performance under Scale Factor 1.

For Oracle at Scale Factor 10, no-encryption outperformed AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256, as expected, showcasing that when scaling the database size, it is possible to see more stable results when looking at the total execution time by the same order of key size of the encryption algorithms used. AES-128 outperformed AES-192, and AES-256. AES-192, compared to AES-128, took 21.83% longer to query, and AES-256, compared to AES-128, took 427.34% longer to query. In terms of system resources, AES-192 shows improved RAM efficiency but relies on disk 3.35% more than AES-128. AES-256, while the most secure, suffers from significant computational overhead, utilizing 21.89% more RAM than no-encryption, but no-encryption requires 29.36% more disk compared to AES-256′s disk usage. AES-128 is shown to be a solution for larger databases, as it outperformed the rest of the encryption algorithms by either operating system performance or execution time performance, making it an optimal choice for Scale Factor 10.

In MySQL Enterprise v9.2, the no-encryption outperforms AES-256 in terms of total execution time at both Scale Factors. At Scale Factor 0.1, AES-256 was 9.2% slower, and at Scale Factor 1, it was 21.5% slower. At Scale Factor 0.1, AES-256 used less CPU and RAM compared to no-encryption. However, at Scale Factor 1, it used slightly more system resources, indicating system inefficiency when querying larger datasets. The analysis presented in this paper is descriptive and uses averages and standard deviations to illustrate overall performance trends. As the focus was on comparative tendencies rather than inferential testing, statistical significance across configurations was not formally assessed. However, future research could include a formal significance analysis to better quantify the strength of the observed differences.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper explores the impact of various encryption algorithms on performance metrics across different database platforms (Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server) and under different load factors. Our findings show that the choice of encryption algorithm affects execution time, CPU usage, RAM consumption, and disk time. Simultaneously, we analyzed the effect on hardware using performance metrics such as CPU usage, RAM consumption, and disk time.

The Oracle system showed that AES-192 had a better performance at Scale Factor 0.1. However, at Scale Factor 1, AES-256 showed the best execution time, while AES-128 delivered a better performance than AES-192 and AES-256 when the workload reached Scale Factor 10, which shows that AES-128 may scale more efficiently. The no-encryption configuration in Oracle had a positive performance compared to encrypted setups during Scale Factor 0.1, Scale Factor 1, and Scale Factor 10, as expected, showing that encryption can impact the query results compared to no-encryption executions. From Scale Factors 1 to 10, AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256 took 1.55×, 1.99×, and 10.76× more time to query in Scale Factor 10, showing a stabilization when scaling, though only AES-256 matches the expected 10× increase. The execution time stabilized when the workload reached Scale Factor 10; AES-128 and AES-192 grew steadily as expected, but AES-256 showed a jump in overhead at Scale Factor 10, showing that it does not handle larger workloads efficiently.

For SQL Server, AES-192 showed linear performance across most Scale Factors, except for Scale Factor 1, where AES-128 performed slightly better, with an average of 18,151 ms compared to AES-192′s execution time average of 19,293 ms and AES-256’s average of 20,393 ms. AES-256, while being the strongest in terms of key size, as expected, had higher execution times and moderately higher disk times, contributing to a slower performance. At Scale Factor 1, execution times and resource usage increased compared to Scale Factor 0.1, but the rise in CPU and RAM varied by encryption algorithm. Disk time increased when Scale Factor 10 was reached, with disk usage reaching 107.50% among the encryption algorithms. Though AES-256 did not have the highest disk usage, it showed the slowest execution time, indicating that encryption complexity can impact the execution time. The execution time overhead from Scale Factor 0.1 to 1 increased 2.45-fold in the non-encrypted database, which is favorable compared to the expected 10-fold increase, indicating stable performance with scaling. At Scale Factor 10, encryption algorithms performed slower than no-encryption, as expected; however, AES-192 was slightly faster than AES-128 with 0.95% lower average execution time, likely due to hardware optimizations and resource management at high loads. The execution time overhead moving from Scale Factor 1 to 10 is 8.37-fold, in the non-encrypted database, indicating that performance stabilizes as data size grows, with potential underperformance as scale increases.

AES-256 was the only encryption algorithm for MySQL, as AES-128 and AES-192 are not implemented. At Scale Factor 0.1, AES-256 was faster than no-encryption, with a performance gain of 51.87%. However, at Scale Factor 1, the performance reversed, with AES-256 taking slightly longer than the no-encryption setup, showing an overhead of 4.22%. This suggests that as the data size increases, MySQL’s performance with AES-256 degrades, suggesting potential instability when scaling.

In the MySQL experiments, MySQL Enterprise v9.2 can manage encryption overhead more stably in both Scale Factors compared to MySQL Community version 8.0.38, which shows significant variability and occasional spikes in overhead. MySQL Enterprise v9.2 includes a more recent and modern method of encryption, using component_keyring_file.dll, which can contribute to better integration and performance consistency.

SQL Server consistently shows a strong capacity to handle complex queries and larger datasets across different Scale Factors. While MySQL AES-256 tends to have a better performance compared to no-encryption at smaller scales, when scaling, it tends to stabilize or underperform. MySQL AES-256 may be better prepared to execute basic queries on smaller datasets. SQL Server is more capable of handling larger performance data workloads. At Scale Factor 10, a more stable factor with a more realistic workload, SQL Server outperformed Oracle, in the three different key sizes of AES, as Oracle’s AES-128 and AES-192 total execution time were approximately 8.7× and 10.7× slower, respectively, than in SQL Server, and Oracle’s AES-256 was nearly forty times slower than in SQL Server, based on total execution time average. No-encryption performance for Oracle was slower than SQL Server’s no-encryption. SQL Server may benefit from caching mechanisms and the query optimizer, and Oracle may have an inefficient query plan adaptation. SQL Server showed consistent performance, regardless of the encryption level, whereas Oracle’s performance was negatively impacted across all configurations, showing that SQL Server’s performance is much more efficient than Oracle’s performance in terms of scalability. That being said, it is possible to claim that SQL Server is the best database to use, followed by Oracle, while MySQL had higher variations in terms of results, and a poor performance compared to Oracle and SQL Server. The author in [

10] concludes by saying that Oracle and SQL Server are much faster and a safer option to use when compared to MySQL. This is consistent with the findings in this thesis, where Oracle and SQL Server outperformed and showed more consistency than MySQL Community v8.0.38. However, MySQL v9.2 showed improved consistency over MySQL Community v8.0.38, though execution times remained higher when compared to Oracle and SQL Server.

In several cases, especially with SQL Server and MySQL Enterprise v9.2, encryption introduced minimal overhead, maintaining the transparent nature of TDE [

6]. However, Oracle exhibited more variable results, with higher execution times under encryption, especially with AES-256 at a larger scale.

In future research we intend to increase the Scale Factors to analyze how encryption affects Oracle, MySQL, and SQL Server performance through system resource monitoring and execution time measurement. SQL Server showed stabilization at Scale Factor 10, while Oracle had some variations, particularly under AES-256. MySQL showed inconsistency between Scale Factor 0.1 and Scale Factor 1, showing that higher Scale Factors can reveal consistency in terms of expectations or highlight scaling inefficiencies. A dedicated machine combined with background process isolation would produce more precise and consistent results, because background processes create variations in the results. This analysis would provide a better understanding of how encryption strength affects system performance and efficiency. This study focuses exclusively on analytical read queries from the TPC-H benchmark. Data refresh streams, maintenance tasks such as inserts, updates and index rebuilds, key rotation, re-encryption, and backup or restore operations were not evaluated, even though they are usually more sensitive to encryption overhead. The experiments were also carried out in a modest academic environment with limited hardware, which means that the results cannot be directly compared with those expected in larger and more powerful systems. Topics such as a clear security model, attacker assumptions, exposure windows, and comparisons with other encryption approaches were also outside the scope of this work. The next phase of this research will involve extending the tests to stronger hardware, addressing these aspects and improving data presentation with visual summaries, while addressing these aspects. Additionally, different encryption algorithms should be analyzed to evaluate their performance characteristics, with the results being compared to those of other algorithms. Furthermore, real-world scenarios should be conducted in cloud environments to evaluate the performance of on-premises and cloud setups using contemporary tools.