Abstract

Organic acid disorders (OADs) are inherited metabolic defects in the enzymes and cofactors involved in metabolic pathways. This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the incidence and regional differences in OADs between the northern and southern regions of China. Searches of the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Chinese databases (CNKI, Veipu, and Wanfang) revealed 1784 studies indexed between January 2002 and December 2024. After quality assessment and data extraction, the meta-analysis was conducted on OAD screening data from 57 studies involving 13,314,056 newborns and 1501 OAD cases in China. The seven most prevalent OADs were methylmalonic acidemia (MMA), 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency, glutaric acidemia type I, isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, isovaleric acidemia, 2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (2-MBD), and propionic acidemia. The meta-analysis revealed an OAD prevalence of 112.38 (95% confidence interval 106.70–118.07) per 1,000,000 newborns. The incidence of OADs and MMA was significantly higher in northern China than in southern China, whereas the incidence of 2-MBD was significantly lower in northern China than in southern China (p < 0.0001). Additionally, the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA was higher in northern China than in southern China (p < 0.05). These results provide valuable epidemiological insights and guidance for newborn screening for OADs in China.

1. Introduction

Organic acid disorders (OADs) are a group of genetic disorders that result from defects in the enzymes and cofactors involved in metabolic pathways. Due to the accumulation of toxic substrates or intermediate metabolites and insufficiency of terminal products, patients with OAD can present with clinical manifestations such as irreversible intellectual impairment, physical disabilities, and even death [1]. However, the clinical manifestations in affected babies are usually asymptomatic at birth or complex and often non-specific. Thus, early diagnosis and timely intervention for many OADs are crucial for preventing adverse complications in affected individuals.

Newborn screening (NBS) for inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) is an essential public health program that enables early diagnosis, and it is both effective and cost-efficient. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) offers high sensitivity and specificity, along with a low sample volume (a single blood spot); thus, this tool has been widely employed in NBS for the detection of IEMs, including OADs, amino acid disorders, fatty acid oxidation disorders, and urea circulatory disorders.

In mainland China, MS/MS-based NBS was first implemented in 2002, with a pilot study reporting an average incidence of OADs of 1 in 8071 newborns [2]. However, subsequent studies have shown that the incidence and disease spectrum of OADs vary significantly across regions in China, particularly between the southern and northern regions, with rates ranging from 1:50,000 to 1:2300 in newborns [3,4,5]. Determining the overall and varying incidence of OADs in the Chinese population is crucial for guiding NBS policies and healthcare planning, particularly considering the potential regional disparities across the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River Line. This north–south divide is associated with differences in genetic background, environment, geography, and lifestyle, all of which may influence disease incidence.

Therefore, the present meta-analysis comprehensively investigated the epidemiological characteristics of OADs in Chinese populations, analyzed the nationwide incidence rate of OADs, and elucidated the differences in the incidence and disease spectrum of OADs between the northern and southern regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [6], and the protocol was registered with PROspective Systematic Review PROtocols (ID: CRD420251132929; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251132929, accessed on 31 August 2025). Three independent researchers (J.Z., J.L., and Y.Z.) systematically searched observational research databases on NBS for OADs between January 2002 and December 2024. The search included English databases such as PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, as well as Chinese databases, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Veipu, and Wanfang. The search terms were (“organic acid disorders” OR “organic acid metabolic disorders” OR “inborn errors of metabolism”) AND (“newborn screening”) AND (“China” OR “Chinese”).

2.2. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the current review if they met the following criteria: (1) original observational studies; (2) studies reporting results of NBS for OADs in different cities, provinces, and autonomous regions of China; (3) study periods between 2002 and 2024; and (4) studies of relatively high quality.

Studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded. Additionally, (1) duplicate publications; (2) studies with overlapping screening regions or times (the study with more participants was included); (3) studies reporting only solo diseases of OADs; (4) studies of hospitalized newborns; and (5) studies not published in English or Chinese were also excluded.

All cases of organic acidemias showed abnormal results via MS/MS-based NBS and were further confirmed by genetic testing.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two researchers (S.H. and Q.Y.) independently extracted the data into an extraction table. The information obtained from the original publications included the first author, publication year, time period, geographic region, number of NBS participants, disease spectrum of the OADs, and the number of cases diagnosed with OADs. The estimated incidence rates of OADs were calculated using these extracted data. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions with another investigator (J.Z.). Since all data were based on previously published studies, ethical approval or patient consent was not required.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of observational studies included in this meta-analysis was independently evaluated by two investigators (S.H. and Q.Y.) using the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ) criteria (Table S1). Studies meeting each criterion were scored as 1, whereas those not meeting or having uncertain criteria were scored as 0, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 11. Higher scores denoted superior quality, with studies with scores of 8–11, 4–7, and 0–3 points classified as high, moderate, or low quality, respectively. Any inconsistencies were discussed comprehensively and resolved by another reviewer (J.Z.).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

We performed a meta-analysis to estimate the pooled incidence and 95% confidence interval (CI) of OADs in China. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan version 5.3 (Update Software Ltd., Oxford, UK). The chi-square test and I2 statistic were used to evaluate the statistical heterogeneity among the studies. For comparisons with I2 values < 50% and p-values > 0.10, a fixed-effects model using the Mantel–Haenszel method was used to calculate the pooled incidence along with the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs. Otherwise, a random-effects model using the Der Simonian and Laird method was used.

We also performed a subgroup analysis to assess the effects of geographic region across studies. Significant differences in subgroup comparisons and disparities were defined as those with p < 0.05.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by systematically excluding individual studies to assess their impact on the pooled ORs. Publication bias was visually assessed using a funnel plot and quantitatively evaluated using Begg’s test, with p < 0.1 indicating publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

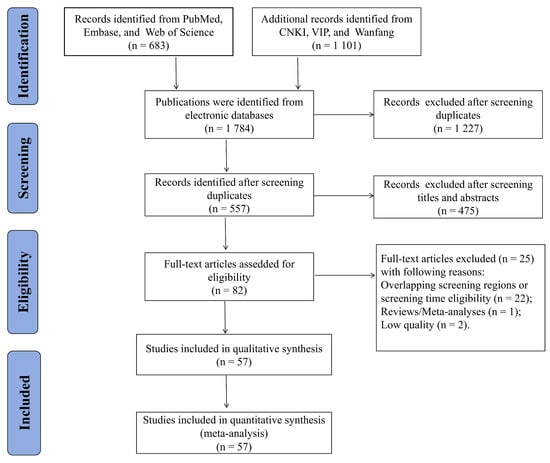

The initial database searches identified 1784 articles from the six databases, including 683 in Chinese and 1101 in English. After screening for duplicates, 1227 articles were excluded, and 557 articles remained. An additional 475 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria after a review of their titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 82 articles were considered potentially eligible and underwent a thorough full-text review. Overall, 25 articles were excluded for overlapping screening or screening time eligibility regions (22 articles), study design (one meta-analysis), and low quality (two articles). Finally, the meta-analysis included 57 eligible studies. A flowchart of the literature search and processing is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

3.2. Study Characteristics

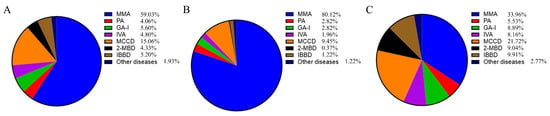

The 57 included studies involved 13,314,056 newborns, 1501 of whom were diagnosed with OADs (Table 1). Notably, 67.11% (8,935,954/13,314,056) of screened newborns resided in southern China. Among the 1501 patients with OADs, the seven most prevalent diseases accounted for 98.07% of the total number; these OADs included methylmalonic acidemia (MMA; 59.03%, 886/1501), 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency (MCCD; 15.06%, 226/1501), glutaric acidemia type I (GA-I; 5.60%, 84/1501), isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (IBDD; 5.20%, 78/1501), isovaleric acidemia (IVA; 4.80%, 72/1501), 2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (2-MBD; 4.33%, 65/1501), and propionic acidemia (PA; 4.06%, 61/1501; Figure 2A). The remaining 29 cases of OADs included 11 cases of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency, three cases of biotinidase deficiency, three cases of 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type I, nine cases of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency, two cases of ethyl malonic encephalopathy, and one case of malonic acidemia. MMA accounted for up to 80.12% (653/815) of all OADs in northern China, whereas the proportions of MMA and MCCD in northern China were 33.96% (223/686) and 21.72% (149/686), respectively (Figure 2B,C). Of the 669 cases of MMA for which subtype data were available, 95 were isolated MMA and 574 were MMA combined with homocystinuria.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Disease spectrum of OADs in Chinese newborns. (A) All regions. (B) Northern region. (C) Southern region. OAD, organic acid disorder.

3.3. The Result of Quality Assessment

According to AHRQ assessment items, articles with scores ≥ 4 were classified as moderate or high quality. The average score was 7.73, indicating minimal risk of bias (Table 1).

3.4. Meta-Analysis Results

3.4.1. OAD Incidence

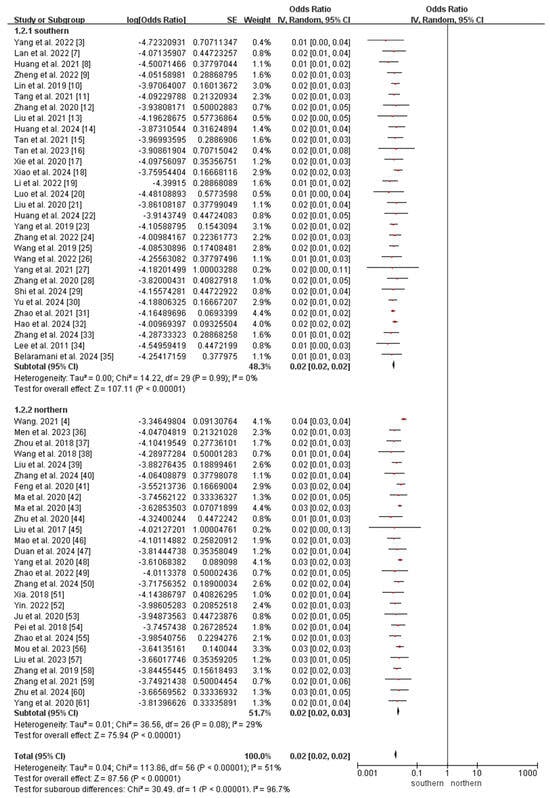

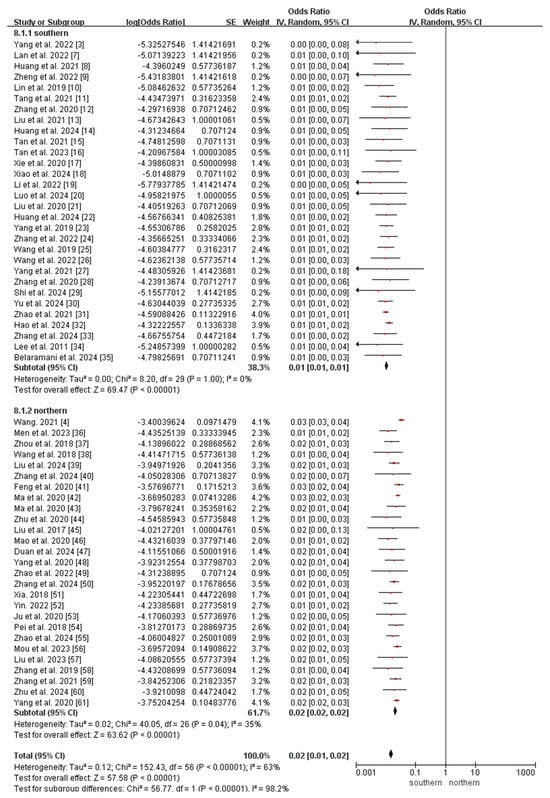

All included studies reported the incidence of OADs. Owing to the significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 51%, p < 0.05), a random-effects model was used to analyze the incidence of OADs in China. The meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of OADs was 112.38 (95% CI 106.70–118.07) per 1,000,000 newborns in China (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of OADs between southern and northern China. OAD, organic acid disorder [3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

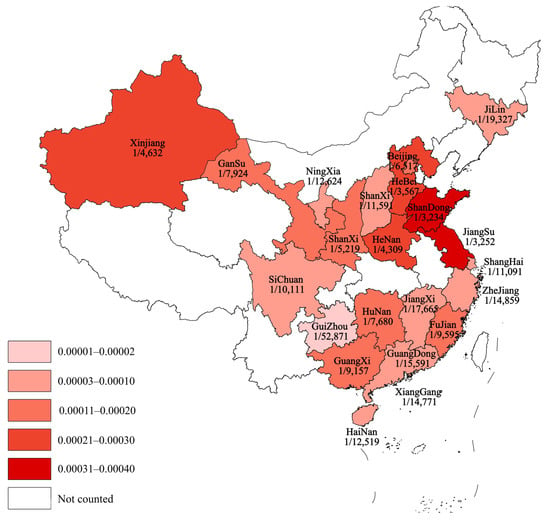

Subgroup analyses of regional incidence of OADs revealed a significantly higher incidence in northern China (184.40 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 171.74–197.06) than in southern China (76.77 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 71.02–82.51; p < 0.0001; Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing the prevalence of OADs in different provinces of China. OAD, organic acid disorder.

3.4.2. Incidence of OAD Disease Spectrum

We also performed a meta-analysis of the seven most prevalent OADs, including MMA, MCCD, GA-I, IBDD, IVA, 2-MBD, and PA. As significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 = 63%, p < 0.001), we used a random-effects model to analyze the incidence of MMA. No significant heterogeneity was identified in the incidence of the other six diseases (I2 = 0%, p > 0.05); therefore, we applied a fixed-effects model for further analysis. The meta-analysis results showed incidences of MMA, MCCD, GA-I, IBDD, IVA, 2-MBD, and PA of 66.34 (95% CI 61.97–70.71), 16.92 (95% CI 14.72–19.13), 6.29 (95% CI 4.94–7.93), 5.84 (95% CI 4.54-7.14), 5.39 (95% CI 4.15–6.64), 4.87 (95% CI 3.68–6.05), and 4.57 (95% CI 3.42–5.71) per 1,000,000, respectively.

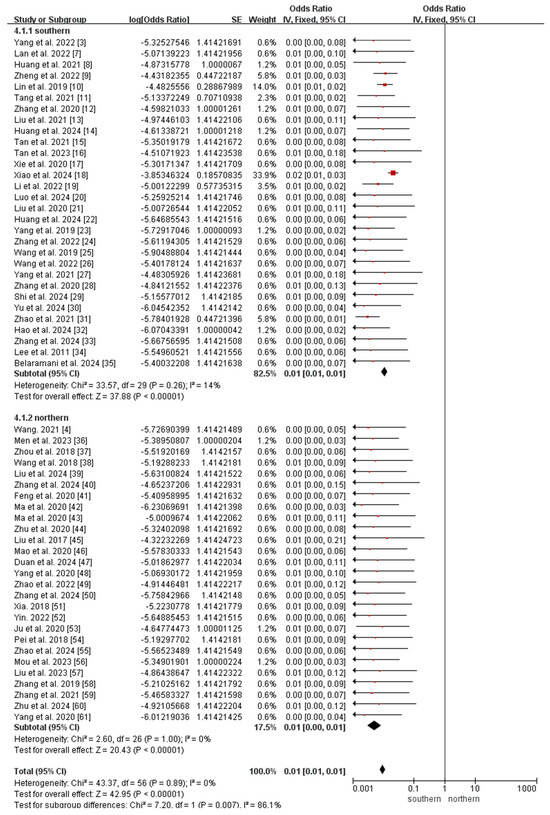

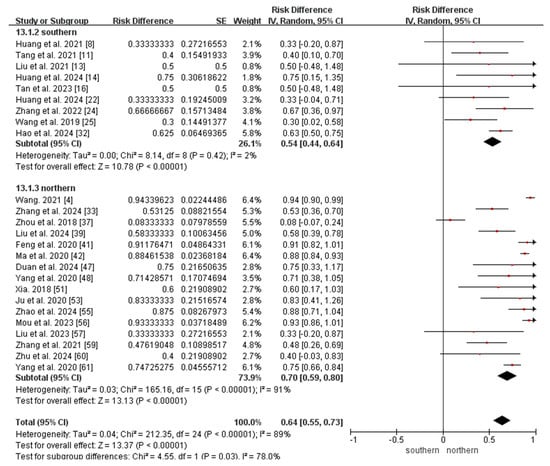

The subgroup analyses revealed that the incidence of MMA in northern China (147.74 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 136.41–159.08) was significantly higher than that in southern China (26.07 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 22.73–29.42; p < 0.0001; Figure 5), whereas the incidence of 2-MBD in northern China (0.68 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 0.09–1.45) was significantly lower than that in southern China (6.94 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 5.21–8.67; p < 0.0001; Figure 6). The incidence of the other diseases did not differ significantly between southern and northern China (Figures S1–S5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of MMA between southern and northern China. MMA, methylmalonic acidemia [3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of 2-MBD between southern and northern China. 2-MBD, 2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency [3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Finally, the meta-analysis of the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA included 25 studies (9 from southern China and 16 from northern China). Owing to the substantial heterogeneity observed among the included studies (I2 = 89%, p < 0.05), a random-effects model was applied. The result showed that the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA was 0.64 (95% CI 0.55–0.73). The results of the subgroup analyses revealed that the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA in northern China (0.70, 95% CI 0.59–0.80) was higher than that in southern China (0.54, 95% CI 0.44–0.64; p < 0.05; Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA between southern and northern China. MMA, methylmalonic acidemia [4,8,11,13,14,16,22,24,25,32,33,37,39,41,42,47,48,51,53,55,56,57,59,60,61].

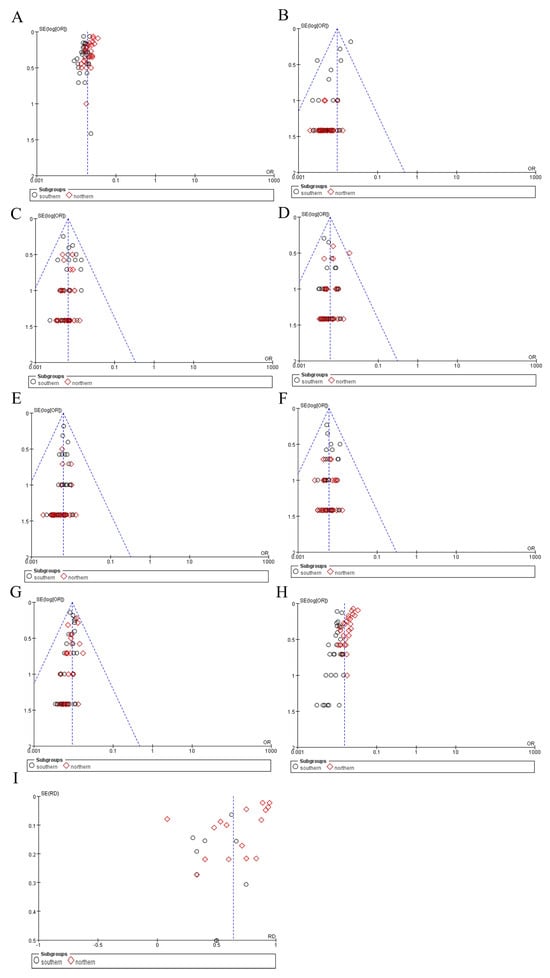

3.4.3. Publication Bias

A funnel plot, a scatterplot commonly used in meta-analyses, was generated to visually assess the presence of publication bias and other small-study effects. The funnel plots regarding the incidence of OADs were generally symmetrical, indicating no significant publication bias (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Funnel plots for publication bias. (A) OAD incidence. (B) 2-MBD incidence. (C) GA-I incidence. (D) PA incidence. (E) IBBD incidence. (F) IVA incidence. (G) MCCD incidence. (H) MMA incidence. (I) Ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA. OAD, organic acid disorder; 2-MBD, 2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency; GA-I, glutaric acidemia type I; PA, propionic acidemia; IBBD, isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency; IVA, isovaleric acidemia; MCCD, 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency; MMA, methylmalonic acidemia.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis included 57 studies spanning the past 20 years, covering over 13 million newborns screened for neonatal OADs across 22 provinces (municipalities) in China. To date, this is the most comprehensive systematic review of OAD screening in China. Our study revealed an OAD incidence of 112.38 (95% CI 106.70–118.07) per 1,000,000 newborns in China, with a notably higher occurrence in northern China (184.40 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 171.74–197.06) than in southern China (76.77 per 1,000,000, 95% CI 71.02–82.51). Owing to the large sample size and representative regional population distribution, coupled with the lack of publication bias in the literature, our results provide an objective and reliable assessment.

Timely identification, diagnosis, and intervention for OADs via NBS are essential for reducing severe clinical consequences in affected individuals. The widespread application of MS/MS worldwide and improvements in genetic testing technology have enabled prompt OAD detection, diagnosis, and management.

Globally, the incidence of OADs in newborns via NBS varies across regions and is estimated to be 1:16,000 in the United States [62], 1:8000 in the United Kingdom [63], 1:10,000 in Germany [64], 1:3400 in Saudi Arabia [65], and 1:2500 in Iran [66]. In East Asian countries, the estimated incidence rate of OADs in Japan and South Korea is 1:22,000 and 1:31,000, respectively [64]. A nationwide cross-sectional survey of 7 million newborns in mainland China reported an OAD incidence of approximately 1:8000 via NBS [2], consistent with the findings in the present meta-analysis.

Differences in genetic backgrounds between northern and southern China are jointly caused by population migration and environmental factors, as well as genetic drift resulting from geographical isolation [67,68,69]. The genetic differences among the Han Chinese in China show a continuous gradient, following a migration and admixture model from south to north [67]. The hot and humid climate in southern China makes it a high-incidence area for malaria, which has led to a higher gene frequency of G6PD deficiency (favism) as a genetic adaptation to resist malaria [69]. Subgroup analysis in this study demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of OADs in northern China, particularly in the Shandong, Henan, and Hebei provinces, suggesting a geographical trend of higher incidence in northern versus southern China.

Elucidating the local disease spectrum of OADs is important for reproductive counseling, diagnosis, treatment management, integration, and allocation of healthcare resources. Specific disease spectrums of OADs have been identified in different regions and populations. For instance, hydroxymethylglutaric aciduria is predominant in the United Arab Emirates [70], MCCD is prevalent in Austria [71] and Singapore [72], and MMA is prevalent in Japan [64].

In this study, the seven most common diseases—MMA, MCCD, GA-I, IBDD, IVA, PA, and 2-MBD—accounted for 98.07% of all cases. This provides strong evidence for the rapid identification of specific diseases within OADs in the Chinese population. Affected children with MMA and PA suffer from poor feeding, vomiting, and recurrent metabolic decompensation [73]. If not adequately treated, this condition can lead to metabolic acidosis and hyperammonemia, and, in severe cases, may progress to coma or even death. The clinical manifestations of MCCD can vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic individuals to those experiencing acute metabolic crises, including hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and neurological abnormalities [74]. Without medical management, most patients with GA1 experience an acute encephalopathic crisis in the first 3–36 months following an intercurrent febrile illness or surgical intervention, resulting in bilateral striatal damage. Patients with IBDD are either asymptomatic, or symptomatic with variable clinical features, including failure to thrive, seizures, anemia, muscular hypotonia, and developmental delay [75]. The clinical manifestations of IVA include paroxysmal vomiting, lethargy or altered mental status, epilepsy, poor feeding, developmental delay, severe metabolic acidosis, hyperammonemia, ketosis, hyper- or hypoglycemia, and cytopenia [76]. Symptomatic patients of 2-MBD present with developmental abnormalities, intellectual disturbance, seizures, muscular atrophy, and even failure to thrive [77].

Furthermore, subgroup analysis revealed a notably higher incidence of MMA and 2-MBD in northern and southern China, respectively, highlighting regional disparities. Additionally, the proportion of patients with MMA combined with homocystinuria was significantly higher in the northern region than in the southern region. Finally, the highest incidence of the disease varied across geographical regions, with 2-MBD predominant in Hunan and Fujian provinces and MMA most prevalent in Shandong, Hebei, Henan, and Gansu Provinces.

This study also has several limitations. First, although our analysis includes studies from 22 provincial-level regions (autonomous regions or municipalities), underreporting persists in regions outside these areas. In addition, the number of newborns included in the studies was also quite limited within some provinces, such as Xinjiang, Beijing, and Shanxi. Second, heterogeneity between studies might reduce the precision of our pooled effect size estimates; thus, caution is required when interpreting our results. Third, our study included only published studies. The exclusion of preprints, conference abstracts, and non-peer-reviewed local or government reports may have introduced publication bias. Finally, all cases of organic acidemias included in the studies demonstrated abnormal results on MS/MS-based NBS and were further confirmed by genetic testing. However, cut-off thresholds for the biochemical markers used in MS/MS-based NBS may vary across laboratories, potentially leading to inconsistent detection of mild cases.

5. Conclusions

Our results yielded a comparatively accurate incidence of 112.38 (95% CI 106.70–118.07) per 1,000,000 newborns, highlighting a significantly higher incidence of OADs and MMA in northern China, and a significantly higher incidence of 2-MBD in southern China. Additionally, we confirmed that the ratio of MMA combined with homocystinuria to MMA was higher in northern China than in southern China. Our findings provide valuable epidemiological insights into OADs in the Chinese population, guiding future NBS endeavors for OADs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijns11040113/s1: Figure S1: Meta-analysis of the prevalence of GA-I between southern and northern China; Figure S2: Meta-analysis of the prevalence of IBBD between southern and northern China; Figure S3: Meta-analysis of the prevalence of IVA between southern and northern China; Figure S4: Meta-analysis of the prevalence of MCCD between southern and northern China; Figure S5: Meta-analysis of the prevalence of P between southern and northern China. Table S1: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology checklist.

Author Contributions

J.Z., J.L., and L.X. conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. S.H., Q.Y., and F.K. data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. M.W., X.Q., P.Z., and Y.Z. supervision, methodology. S.H., Q.Y., and F.K. contributed equally as first authors. J.Z., J.L., and L.X. contributed equally as co-corresponding authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2024J011043) and the Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project (Grant No. 2024CXA038).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OADs | Organic acid disorders |

| NBS | Newborn screening |

| MS/MS | Tandem mass spectrometry |

| MMA | Methylmalonic acidemia |

| MCCD | 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency |

| GA-I | Glutaric acidemia type I |

| IBDD | Isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| IVA | Isovaleric acidemia |

| 2-MBD | 2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| PA | Propionic acidemia |

| HCS | Holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency |

| BTD | Biotinidase deficiency |

References

- Ramsay, J.; Morton, J.; Norris, M.; Kanungo, S. Organic acid disorders. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Zhu, J.; Yu, E.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Incidence of inborn errors of metabolism detected by tandem mass spectrometry in China: A census of over seven million newborns between 2016 and 2017. J. Med. Screen 2021, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, X. Analysis of screening results of neonatal genetic metabolic diseases by tandem masss-spectrometric technique in Guiyang Area. Chin. J. Fam. Plan. 2022, 30, 1404–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Application analysis of tandem mass spectrometry in screening and diagnosis of neonatal genetic and metabolic diseases. J. Heze Med. Coll. 2021, 33, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; He, L.; Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zeng, Y.; He, J. Analysis of Screening Results for Genetic Metabolic Diseases among 352 449 Newborns from Changsha. Chin. J. Med. Genet. 2023, 40, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Liao, Z.; Yuan, L. Analysis on tandem mass spectrometry-based screening results for inherited metabolic diseases in neonates in Longyan City. China Med. Pharm. 2022, 12, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, Q.; Fan, C.; Xue, F.; Guo, F. Analysis of newborn disease screening results from Nanping City in China. Exp. Lab. Med. 2021, 39, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Ye, S.; Song, W. Analysis of 135 148 cases of neonatal tandem mass spectrometry screening in East Fujian. Syst. Med. 2022, 7, 166–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, W.; Fu, Q. Expanded newborn screening for inherited metabolic disorders and genetic characteristics in a southern Chinese population. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 494, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Tan, M.; Xie, T.; Tang, F.; Liu, S.; Wei, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y. Screening for neonatal inherited metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry in Guangzhou. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2021, 50, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zeng, Y. Expanded newborn screening for inherited metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry in Huizhou City in China. Lab. Med. Clin. 2020, 17, 411–413. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Shi, L. Analysis of tandem mass spectrometry screening and follow-up results of neonatal genetic metabolic disorders in Meizhou. Youjiang Med. J. 2021, 49, 834–838. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Liao, J.; Yan, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Retrospective analysis of screening status, genes and clinical phenotypes of genetic metabolic diseases in 220,000 newborns in Zhongshan City. Chin. J. Birth Health Hered. 2024, 32, 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Chen, D.; Chang, R.; Pan, L.; Yang, J.; Yuan, D.; Huang, L.; Yan, T.; Ning, H.; Wei, J.; et al. Tandem mass spectrometry screening for inborn errors of metabolism in newborns and high-risk infants in southern China: Disease spectrum and genetic characteristics in a Chinese population. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 631688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Kuang, J.; Lan, G.; Zeng, G.; Gu, Y.; Shi, X. Disease spectrum and genetic profiles of neonatal inborn errors of metabolism in selected areas of Nanning City. Chin. J. Neonatol. 2023, 38, 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Luo, H.; Hu, L.; Yang, C. Analysis of diagnostic value of blood tandem mass spectrometry in neonatal hereditary metabolic diseases. Chin. J. Birth Health Hered. 2020, 28, 729–731. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Feng, Z.; Xu, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, S.; Shen, Y.; et al. 206,977 Newborn screening results reveal the ethnic differences in the spectrum of inborn errors of metabolism in Huaihua, China. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1387423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, J.; He, L.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y. Spectrum analysis of inherited metabolic disorders for expanded newborn screening in a central chinese population. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 763222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Yi, H.; Yang, X.; Peng, Y.; Ni, L.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Huang, H. Prevalence of inherited metabolic disorders among newborns in Zhuzhou, a southern city in China. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1197151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, B.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ji, X.; Qin, W.; Cao, A. Combined application of tandem mass spectrometry and high-throughput sequencing in neonatal screening. Mod. Prev. Med. 2020, 47, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Gu, H. retrospective analysis of tandem mass spectrometry screening for newborn genetic metabolic diseases in 41058 Newborns. Guide China Med. 2024, 22, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Wang, T. Application of next-generation sequencing following tandem mass spectrometry to expand newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism: A multicenter study. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, C. Expanded newborn screening for inherited metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry in a northern Chinese population. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 801447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B. Expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism by tandem mass spectrometry in Suzhou, China: Disease spectrum, prevalence, genetic characteristics in a Chinese population. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Guan, H.; Wang, F.; Huang, S.; Yang, B. 126,111 Newborn screening results of inborn errors of metabolism in Jiangxi, China. Jiangxi Med. J. 2022, 57, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Pan, S. Newborn screening and diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism A 2-year study in Shangrao City, China. Lab. Med. Clin. 2021, 18, 3030–3033. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, X.; Li, T.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of screening for neonatal inherited metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry in parts of Sichuan Province. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2020, 28, 809–812. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, A.; Long, Q.; Yang, S.; He, D. Newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in Yibin City from 2019 to 2021, China. Pract. Prev. Med. 2024, 31, 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Meng, C.; Chen, Y. Newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in Ningbo City from 2014 to 2023, China. Mod. Pract. Med. 2024, 36, 763–766. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Zhou, D.; Huang, X.; Dong, H. Newborn screening for inherited metabolic diseases using tandem mass spectrometry in China: Outcome and cost–utility analysis. J. Med. Screen 2021, 29, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Liang, L.; Gao, X.; Zhan, X.; Ji, W.; Chen, T.; Xu, F.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, H.; Gu, X.; et al. Screening of 1.17 million newborns for inborn errors of metabolism using tandem mass spectrometry in Shanghai, China: A 19-year report. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 141, 108098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, J.; Tian, G. Comparative analysis of inherited metabolic diseases in normal newborns and high-risk children: Insights from a 10-year study in Shanghai. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 558, 117893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.H.; Mak, C.M.; Lam, C.W.; Yuen, Y.P.; Chen, A.O.K.; Shek, C.C.; Siu, T.S.; Lai, C.K.; Ching, C.K.; Siu, W.K.; et al. Analysis of inborn errors of metabolism: Disease spectrum for expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaramani, K.M.; Chan, T.C.H.; Hau, E.W.L.; Yeung, M.C.W.; Kwok, A.M.K.; Lo, I.F.M.; Law, T.H.F.; Wu, H.; Wong, S.S.N.; Lam, S.W.; et al. Expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in Hong Kong: Results and outcome of a 7 year journey. Int. J. Neonatal Screen 2024, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, S.; Liu, S.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, S.; Mao, H.; Wang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, L. Incidence and genetic variants of inborn errors of metabolism identified through newborn screening: A 7-year study in eastern coastal areas of China. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Gu, M. The clinical application of tandem mass spectrometry for newborn screening in Xuzhou. Int. J. Genet. 2018, 41, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Liu, F.; Hao, S. Application of tandem mass spectrometry in expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in Gansu Province, China. Matern. Child Health Care China 2018, 33, 861–863. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Hui, L.; Hao, S. Disease spectrum and gene variation analysis of neonatal inherited metabolic diseases in Gansu region. J. Int. Reprod. Health/Fam. Plan. 2024, 43, 378–383. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Hui, L.; Zhou, B.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Hao, S.; Da, Z.; Ma, Y.; Guo, J.; Cao, Z.; et al. Disease spectrum and pathogenic genes of inherited metabolic disorder in gansu province of China. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2024, 26, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Jia, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Feng, L. Screening results of 128,399 cases of neonatal genetic metabolic diseases in Shijiazhuang by tandem mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020, 38, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Zhao, D.; Ma, K.; Ni, M.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Retrospective analysis on screening of neonates inherited metabolic diseases from 2013 to 2019 in Henan Province. Lab. Med. Clin. 2020, 17, 1965–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Yue, A.; Song, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, R. Expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism by tandem mass spectrometry in newborns from Xinxiang City in China. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Song, P.; Hao, P.; Zheng, C. The results of 105,437 newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism. Matern. Child Health Care China 2020, 35, 3837–3839. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Lian, H. Retrospective analysis of inherited metabolic diseases screening in Liaoyuan area from 2011 to 2016. China Health Stand. Manag. 2017, 8, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Jing, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, M.; Miao, T.; Liu, J. Ethnic preference distribution of inborn errors of metabolism: A 4-Year study in a multi-ethnic region of China. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 511, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Analysis of tandem mass spectrometry screening results of neonatal genetic metabolic diseases in Jining City. Med. Lab. Sci. Clin. 2024, 35, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, C.; Xu, P.; Jin, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Huang, C.; Jiang, M.; Chen, X. Newborn screening and diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism: A 5-year study in an Eastern Chinese population. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 502, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, J.; Li, X. The Results of 41,062 newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in Langfang City, China. Chin. J. Birth Health Hered. 2022, 33, 503–507. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Yu, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Hou, H. Application value of tandem mass spectrometry combined with high-throughput 22 457 neonates in Liaocheng Region. Matern. Child Health Care China 2024, 39, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, F. Analysis of the role and significance of tandem mass spectrometry in the screening and diagnosis of neonatal inherited metabolic diseases. Chin. J. Birth Health Hered. 2018, 26, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F. Analysis of the incidence rate and gene mutation status of neonatal genetic metabolic diseases in the Tai’an Region, China. Matern. Child Health Care China 2022, 37, 4516–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, C.; Lan, X. Application analysis of tandem mass spectrometry in neonatal inherited metabolic diseases in Weihai Region, China. Med. Lab. Sci. Clin. 2020, 31, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, W.; Lu, X.; Tian, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Analysis of screening results of tandem mass spectrometry for neonatal genetic metabolic diseases in Weifang Region. Chin. Pediatr. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 2018, 10, 452–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, L.; Gan, X. Screening results of tandem mass spectrometry for neonatal genetic metabolic diseases in Zaozhuang. Chin. J. Birth Health Hered. 2024, 32, 2659–2662. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, K.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Dong, L.; Liu, N. Screening Results of 223 368 Cases of Neonatal Genetic Metabolic Diseases in Zibo by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Clin. Med. Pract. 2023, 27, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y. Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism in a Northern Chinese Population. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 36, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Yan, Y.; Mu, W.; Yu, J.; Yu, L.; Liang, Q. Retrospective analysis on screening of 81,138 neonates inherited metabolic diseases. J. Chin. Physician 2019, 21, 1081–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Qiang, R.; Song, C.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, R.; Yu, W.; Feng, M.; Yang, L.; et al. Spectrum analysis of inborn errors of metabolism for expanded newborn screening in a northwestern Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Han, L.; Yang, P.; Feng, Z.; Xue, S. Spectrum analysis of inborn errors of metabolism for expanded newborn screening in Xinjiang, China. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Gong, L.F.; Zhao, J.Q.; Yang, H.H.; Ma, Z.J.; Liu, W.; Wan, Z.H.; Kong, Y.Y. Inborn errors of metabolism detectable by tandem mass spectrometry in Beijing. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 33, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, D.M.; Millington, D.S.; McCandless, S.E.; Koeberl, D.D.; Weavil, S.D.; Chaing, S.H.; Muenzer, J. The tandem mass spectrometry newborn screening experience in North Carolina: 1997–2005. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.; Green, A.; Preece, M.A.; Burton, H. The incidence of inherited metabolic disorders in the West Midlands, UK. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yamada, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Purevsuren, J.; Yang, Y.; Dung, V.C.; Khanh, N.N.; Verma, I.C.; Bijarnia-Mahay, S.; et al. Diversity in the incidence and spectrum of organic acidemias, fatty acid oxidation disorders, and amino acid disorders in Asian countries: Selective screening vs. expanded newborn screening. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2018, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moammar, H.; Cheriyan, G.; Mathew, R.; Al-Sannaa, N. Incidence and patterns of inborn errors of metabolism in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, 1983–2008. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarian, L.; Ilkhanipoor, H.; Amirhakimi, A.; Afshar, Z.; Nahid, S.; Moradi Ardekani, F.; Rahimi, N.; Yazdani, N.; Nikravesh, A.; Beyzaei, Z.; et al. Epidemiology of inherited metabolic disorders in newborn screening: Insights from three years of experience in southern Iran. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.W.K.; Mangul, S.; Robles, C.; Sankararaman, S. A comprehensive map of genetic variation in the world’s largest ethnic group-Han Chinese. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 2736–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, H.; Bei, J.-X.; Sun, L.; Jia, W.; Li, T.; Zhang, F.; Seielstad, M.; Zeng, Y.-X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Genetic structure of the Han Chinese Population revealed by genome-wide SNP variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 85, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Peng, Y.; Luo, L.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Yi, H. Human genetic variations conferring resistance to malaria. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hosani, H.; Salah, M.; Osman, H.M.; Farag, H.M.; El-Assiouty, L.; Saade, D.; Hertecant, J. Expanding the comprehensive national neonatal screening programme in the United Arab Emirates from 1995 to 2011. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2014, 20, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, D.C.; Ratschmann, R.; Metz, T.F.; Mechtler, T.P.; Möslinger, D.; Konstantopoulou, V.; Item, C.B.; Pollak, A.; Herkner, K.R. The National Austrian Newborn Screening Program—Eight years experience with mass spectrometry. Past, present, and future goals. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2010, 122, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Tan, E.S.; John, C.M.; Poh, S.; Yeo, S.J.; Ang, J.S.M.; Adakalaisamy, P.; Rozalli, R.A.; Hart, C.; Tan, E.T.; et al. Inborn error of metabolism (IEM) screening in Singapore by electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI/MS/MS): An 8 Year journey from pilot to current program. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 113, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forny, P.; Hörster, F.; Ballhausen, D.; Chakrapani, A.; Chapman, K.A.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Dixon, M.; Grünert, S.C.; Grunewald, S.; Haliloglu, G.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic acidaemia and propionic acidaemia: First revision. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 566–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, Y. Newborn screening and genetic diagnosis of 3-methylcrotonyl-coa carboxylase deficiency in Quanzhou, China. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2024, 40, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Chen, Q.X.; Shu, Q.; Jiang, P.; Tong, F. phenotype, genotype and long-term prognosis of 40 Chinese patients with isobutyryl-coa dehydrogenase deficiency and a review of variant spectra in ACAD8. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Lei, M.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Li, D. Analysis of the genotype-phenotype correlation in isovaleric acidaemia: A case report of long-term follow-up of a Chinese patient and literature review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 928334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensenauer, R.; Niederhoff, H.; Ruiter, J.P.N.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Schwab, K.O.; Brandis, M.; Lehnert, W. Clinical variability in 3-hydroxy-2-methylbutyryl-coa dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 51, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).