Abstract

This article examines the evolution of heraldic memory and genealogical consciousness within the Czerny family from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Focusing on this single lineage makes it possible to trace, in a longue durée perspective, how heraldic narratives emerged, were transformed, and became embedded in family identity. The study employs a mixed methodology combining historical and genealogical analysis of municipal and noble registers, heraldic artefacts, epitaphs, and family archives with critical interpretation of early modern panegyrics and oral traditions. This approach enables reconstruction of both material and symbolic aspects of heraldic memory and its adaptation to changing political and social contexts. The findings reveal three major patterns. First, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Czerny (Szwarc/Czarny) family consolidated its noble status by linking the Nowina coat of arms to heroic myths, especially after the death of Mikołaj Czerny at Pskov. Second, in the 17th century, Michał Czerny introduced the “Szwarcenberg” element to the surname, signifying aspirations to aristocratic prestige rather than actual heraldic adoption. Third, these narratives persisted in epitaphs, literary texts, and oral tradition into the modern period. The case illustrates how heraldic memory operated as a dynamic instrument of symbolic self-legitimation among the Polish nobility.

1. Introduction

The aim of this article is to outline the formation of heraldic consciousness and memory within the Czerny family in a longue durée perspective. They represent an intriguing example of the evolution of a heraldic narrative associated with a noble lineage. In the Middle Ages, sources record them as Szwarc (German for Czarny); from the early 16th century they appear as Czarny, bearing the Nowina coat of arms, while the form Czerny became established in the mid-16th century. From the late 17th century, they added the element “Schwarzenberg” to their surname, thereby creating the myth of heraldic adoption by the German-Czech aristocratic family of Schwarzenberg.

In this article, I will trace successive transformations in the family’s identity across the centuries, together with the legend that accompanied these changes and has survived in the family’s oral tradition to the present day. Studies devoted to heraldic memory have been undertaken only sporadically (Rogulski 2017) and usually concerned royal or princely families (Coss 2002), which is not surprising, since it was the aristocratic class that for a long time supported collective memory (Halbwachs 1992). This results from the limited source material available to us, and consequently from the difficulties in reconstructing and tracing the changes in the formation of family consciousness.

Contemporary research indicates that as human memories accumulate, there arises a need to consolidate and transmit them (Assmann 2005). In the case of the Polish nobility, and not only them, a kind of memory policy was carried out, which involved enriching their own past (Rogulski 2019; Broadway 2013; Evans 2011; Bouchard 2001; Fox 1999). The attempts made by the Czerny family to ennoble their own history correspond to practices undertaken by medieval families, for example, French ones (Bouchard 2001). One may therefore point to the universality of such phenomena as seeking to emphasize the antiquity of a family or to assert princely origins. This case study illustrates the universality and repetitiveness of these mechanisms not only across time (Middle Ages–Early Modern period–the present) but also across regions (the broadly understood Western Europe as well as Central and Eastern Europe). In this context, it is important to note that the Czerny family did not belong to the elite of the Kingdom of Poland, and their aspirations found an outlet in the creation of legends about their origins.

The article also addresses issues related to heraldry, which is an inseparable element of European genealogy. It is worth noting that in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, bearing a particular coat of arms was associated with belonging to a so-called heraldic clan (Bieniak 2002), just as a territorial coat of arms served as a sign of regional affiliation (Damen and Meer 2022). In the noble Commonwealth, beginning in the Middle Ages, this was also linked to tangible material benefits and social standing: when offices were granted, membership in a heraldic community was often taken into account, meaning that not only blood relatives but also those who bore the same coat of arms were selected (Bieniak 2002). For a genealogist, a coat of arms constitutes an extremely important clue indicating stable family affiliation. In the case of the Czerny family, their coat of arms—Nowina—provided the basis for creating a family legend rooted in the heraldic narrative. It was then expanded with additional elements and passed down from generation to generation.

The article is divided into two main parts. First, it briefly outlines the history of three distinct families: the Szwarc family bearing the Bożezdarz coat of arms, the Czerny family bearing the Nowina coat of arms, and the German-Austrian princes of Schwarzenberg with their own coat of arms, with particular focus on the main protagonists—the Czerny family. The second part discusses the mechanism by which the Czernys’ genealogical consciousness developed, based largely on literary accounts. The basis for such claims lies in linking families on the grounds of the sound of their surnames: Szwarc in German means Czarny/Czerny (“black”), and the surname Schwarzenberg also contains this element. Aspiring to enter the circles of wealthy nobility as quickly as possible, the Czerny family drew upon the ‘antiquity’ of the Szwarc family and the ‘princeliness’ of the Schwarzenbergs over the course of two centuries in order to construct their own legend.

2. From Szwarc to Szwarcenberg Czerny

2.1. The Szwarc Family of the Bożezdarz Coat of Arms in the 15th and 16th Centuries

In the 15th century, Kraków was both a commercial city and the capital of Poland. Owing to the opportunities for rapid advancement within municipal structures, it was also among the most frequently chosen destinations for merchants. Among the newcomers who settled permanently in Kraków at that time, the surname Szwarc was particularly common. This was an appellative surname, derived from an adjective designating hair color (Kowalik-Kaleta 2007). Its Polish equivalent was Czarny, while in Latin it corresponded to Niger. The municipal admission registers of Kraków record more than twenty individuals bearing the name Szwarc (Kaczmarczyk 1913). Moreover, the overwhelming majority of them bore the forename Jan.

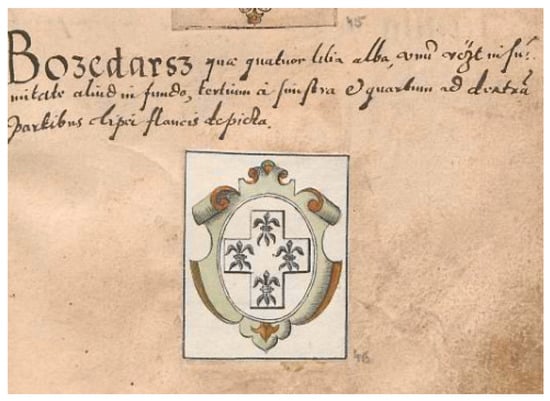

Of all these individuals, the most interesting are two wealthy merchant families: the Szwarc family of the Bożezdarz coat of arms and the Czarny family of the Nowina coat of arms. The progenitor of the Szwarc family was Jerzy, who was admitted to Kraków municipal citizenship in 1414 (Kaczmarczyk 1913), most likely originating from Bardejov or Košice, now in Slovakia (Slezáková 2011). He primarily traded in textiles, and his mercantile company extended its activity to Bruges, Antwerp, Nuremberg, and Lviv (Brzegowy 2024). The wealth thus acquired he invested, for instance, in real estate—he owned two houses on the Kraków market square (ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 428). In time, he also turned his attention to saltworks and ores, including mines in Trzebinia (Kutrzeba 2009). As one of the wealthiest merchants in Kraków, he granted loans to King Władysław of Varna. Presumably as a reward for such services, in 1442 he obtained ennoblement (a formal legal act by which a non-noble person was elevated into the noble estate) in Buda and the Bożezdarz coat of arms, which he and his descendants were thereafter entitled to use (Długosz 1887) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Bożezdarz Coat of Arms from Arma baronum Regni Poloniae by Jan Długosz.

Two years later, on 10 November 1444, King Władysław III perished at the Battle of Varna. Jerzy, who had set out with the king, was already back in Kraków by November (Kuraś 1969). It may thus be assumed that, as a knight with a relatively recent patent of nobility, he was obliged to accompany the young monarch on campaign, yet he rather quickly abandoned the military contingent, likely invoking his advanced age as justification—he was around sixty at the time. He died in 1451, leaving behind an estate that included, among other holdings, four townhouses in Kraków, two in Košice, and shares in saltworks. These assets were inherited by his sons (ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 429). None of them, however, inherited his commercial acumen, and the family never again attained the financial and social standing it had enjoyed in the first half of the 15th century under Jerzy’s leadership. The male line of the family soon died out: Jerzy’s grandsons Erazm and Stanisław died in 1527 and 1543, respectively, leaving only daughters (Wysmułek 2017).

The Szwarc family were not related to the Czerny (or Czarny) family of the Nowina coat of arms. Nevertheless, owing to their status, they are significant in considerations of genealogical memory: from the 16th century onward, the Czerny regarded Jerzy and the Szwarc family as their own progenitors. The Czerny family readily referred to him (Jerzy) as their progenitor for several reasons: the identical surnames (Szwarc in Polish means Czarny/Czerny), their similar origins as merchants in Kraków, and the fact that Jerzy had rendered notable service to Polish kings and possessed documented ennoblement. This last point was particularly important for the Czerny family, whose noble status was being questioned in the early 16th century—a point to which I shall return later in this discussion.

2.2. The Czerny Family of the Nowina Coat of Arms in the 15th and 16th Centuries

The earliest surviving references to the Czerny family date to the mid-15th century, when Jan, an impoverished nobleman, embarked upon a mercantile career in Kraków (Kaczmarczyk 1913) and attained the office of municipal juror (Wysmułek 2017). In the preserved archival materials, the family most often appears as Szwarc or Czarny. This variation stemmed from the language of the sources: in Latin texts they were recorded as Czarny, and in German as Szwarc. On the basis of the extant documents and Jan’s network of contacts, it can be established that he was Polish, yet owing to his numerous business ventures and commercial partnerships with burghers of German origin, he spoke German, as did his sons, and thus used the German form of his surname (ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 430).

Jan had two sons: Adam and Paweł. Until the 1490s, they pursued trade, primarily in cloth, much as their father had done. Later, they turned to investments in ores, and especially salt. Thanks to loans extended by Paweł, the younger of the two brothers, to successive monarchs of the Jagiellonian dynasty, he was granted a lease of the Kraków saltworks and the office of saltmaster (żupnik), which carried with it considerable remuneration (AGAD MK sig. 17). Paweł soon began acquiring landed estates in Lesser Poland, including Brzesko with its surrounding villages (approximately 40 km southeast of Kraków), and later in the Lublin region (Urzędów and villages around city of Lublin), simultaneously holding local offices (Brzegowy 2024). The elder brother, Adam, remained in the city of Krakow, pursuing a career as a councillor (Starzyński 2014). The trajectories of Jerzy Szwarc and the Czerny brothers were strikingly similar in manner: both began as cloth merchants along the eastern trade route and gradually expanded their ventures westward. With increasing wealth, they invested in salt and metals, often obtaining royal grants in salt or lead mines. It should be noted, however, that in the 15th century most affluent Kraków families accumulated wealth in precisely this manner, such as the Boner and Bethmann families (Ptaśnik 1905).

Interestingly, the social standing of the Czerny as nobles was not firmly established at this time. As late as the 1520s, Spytek Tarnowski accused Paweł’s sons of being nobles in name only, their position deriving merely from the fortune inherited from their father, who had “made his money” in commerce (ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 39). Although the dispute was resolved amicably, it is difficult to deny that the family’s mercantile origins were not a source of pride for aspiring nobles. In order to sanction their status, they began the process of associating their name with a coat of arms.

At this time, the Czerny family bore the Nowina coat of arms. This is attested by surviving material evidence: coats of arms displayed on the finial of the Gethsemane Chapel at St. Barbara’s Church in Kraków (Figure 2), and above the southern portal of the parish church in Brzesko (Figure 3). The chapel in Kraków served as a kind of family necropolis, where members of the Czerny were buried. The church in Brzesko, by contrast, was the principal place of worship within the landed complex held by the Czerny for more than 250 years (from the late 15th to the early 18th century).

Figure 2.

The Nowina coat of arms in the wimperg of the Chapel of the Agony (Kaplica Ogrojcowa) at St. Barbara’s Church in Kraków.

Figure 3.

The Nowina coat of arms above the south portal of St. James’ Church in Brzesko.

The Nowina coat of arms was linked to an old legend, recounted in the 16th century by the Polish heraldist Bartosz Paprocki (Paprocki 1584). According to the story, during a battle with the Ruthenians in 1121, the son of a cauldron-maker, Captain (rotmistrz) Nowina, serving under Bolesław the Wrymouth, saved the prince by yielding him his horse. In gratitude, Bolesław granted him a coat of arms depicting a cauldron handle, alluding to the trade of the brave captain’s father (Paprocki 1578). Paprocki further noted that the family’s progenitors derived from a German family of Szwarcs (Paprocki 1584).

Despite this heraldic association with military valor, the family lacked a martial tradition—none of its members took part in the campaigns of Kings Sigismund the Old or Sigismund Augustus (Brzegowy 2024). This situation changed in the late 1570s and early 1580s, with the outbreak of the Polish–Muscovite War (1577–1582). Among the troops led by Hetman Jan Zamoyski was Mikołaj, one of the three sons of Piotr Czerny, the future castellan of Lublin (APL Castr. Lub. sig. 29). In September 1581, during a reconnaissance near Pskov, Mikołaj was struck in the heel by cannon fire. He died a few days later from his wounds (Urwanowicz 1996). His body was brought back to his homeland, where a funeral—likely in Lublin—was held (Janicki 2001).

From the moment of Mikołaj’s death at Pskov, the family began to place explicit emphasis on its military valor—an emphasis that corresponded closely with the aforementioned heraldic legend of the Nowina clan. The loss of the eldest son at Pskov became a turning point for the family, an event commemorated by Renaissance poets such as Jan Kochanowski (Kochanowski 1883), Samuel Wolff (Paprocki 1584), and Sebastian Klonowic. The latter, in his Funerary Laments, wrote of the Czerny in the following terms: “you send your sons as offerings to the Commonwealth, begrudging neither labors, children, goods, nor even yourselves” (Wiśniewska 2006).

Significantly, the political career of Mikołaj’s father, Piotr, accelerated in the aftermath of his son’s death. Barely five years later, he was appointed castellan of Lublin, thereby becoming the first senator in the Czerny family—a development that undoubtedly reinforced the narrative of the family’s service to the homeland (Brzegowy 2024).

Equally noteworthy is that the preserved literary works reveal the family’s deliberate effort at this time to intertwine Mikołaj’s fate at Pskov with the heraldic legend. In 1609 Jan Achacy Kmita, a Lesser Poland poet and friend of the Czerny, published a work entitled Phoenix, dedicated to the family (Kmita 1609). In the dedication, he presented a literary version of the heraldic legend, interwoven with the death of Mikołaj. The text, composed shortly after the Polish–Muscovite War, reflects how vivid the memory of Mikołaj still was. Referring to a severed leg, the author pointed to an expanded version of the legend explaining why the crest of the Nowina arms contained a golden shin. According to this variant, after rescuing Bolesław the Wrymouth, Nowina continued to fight. During a skirmish with the Czechs, he was captured together with his commander. Shackled to his leader, Nowina cut off his own leg, enabling the commander’s escape. Only three days later, when the commander was already far away, did Nowina reveal the event to the guards. Impressed by the captain’s bravery, the Czechs treated his wounds and sent him back to Poland, where in recognition of his sacrifice the “golden shin,” that is, a leg clad in armor, was added to his coat of arms (Niesiecki 1841).

This version of the legend resonated perfectly with the fate of Mikołaj, who had been struck in the heel by cannon fire. Subsequent verses underscored that the memory of the valiant Nowina had endured through the centuries, and that the family continued Nowina’s illustrious martial deeds. In the context of the heraldic legend emphasizing the bravery of those who bore the Nowina coat of arms, the figure of Mikołaj was crucial—he was the first member of the family who actually took part in military actions and died, giving his life for the Fatherland. It is therefore not surprising that the family placed strong emphasis on commemorating him.

2.3. Toward Vienna and the Schwarzenbergs in the 17th Century

The 17th century brought no major changes in the functioning of the family. As with other nobles, the continuous wars of the century in Poland had adverse effects on the Czerny’s financial standing. Yet their impoverishment did not progress rapidly, and they managed to retain their estates. The next family member to gain renown on the battlefield was Michał Czerny (1640–1697) (Ziemierski 2014). Privately, he was a close friend of Jan Sobieski, who, at the election of 1674, was chosen King of Poland. This friendship had a decisive influence on Michał’s career, though before his later advancement, he took part in the expedition to Vienna and later famous battle of Vienna (Odrowąż-Pieniążek 1933). Before proceeding to the analysis, it is worth recalling the key events that culminated in the siege of Vienna and the subsequent relief operation carried out by the Polish forces.

The imminent threat of war with the Ottoman Empire, coupled with limited Habsburg enthusiasm, prompted papal legate Marco d’Aviano to negotiate a treaty signed in March 1683 between Emperor Leopold I and King Jan III Sobieski (Jasienica 1982). According to its terms, in the event of a Turkish attack on Kraków or Vienna, the allies were obliged to provide mutual assistance, with their armies financed jointly by the Polish king, the emperor, and the pope (Pajewski 1978). The opportunity to act on the treaty soon arose. Early in 1683, the Turks began to assemble their forces, which set out from Adrianople in January and joined reinforcements at Belgrade in March. Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa was appointed commander of the expedition, leading an army numbering between 140,000 and 300,000 men (Drane 1858). Advancing rapidly, the Ottoman forces reached Vienna on 14 July and commenced a two-month siege. The city’s defense was entrusted to General Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg (Jasienica 1982). In early September, only days before the arrival of the Polish army, the Turks were already dangerously close to the imperial palace. The decisive battle, beginning on 12 September, lasted about twelve hours and was concluded by the charge of the Polish hussars under the command of Hetmans Stanisław Jabłonowski and Mikołaj Sieniawski (Jasienica 1982).

Despite the victory and the salvation of Vienna, Leopold I did not meet with the Polish king until 15 September, in Schwechat. Owing to the emperor’s rather cold reception of Sobieski, the Polish army pressed onward in pursuit of the Turks. The consequence was another triumph at Parkany in Hungary. In December 1683, the king and his forces returned to Kraków (Wójcik 1991).

Little is known about Michał’s specific role in the campaign, though he likely remained among Sobieski’s trusted entourage. He unquestionably accompanied the king to Vienna (Odrowąż-Pieniążek 1933), and following the victory, from 13 September he stayed with Sobieski and Kraków vice-starost Andrzej Żydowski at the Viennese Hofburg (Piekosiński and Krzyżanowski 1910). He later joined the king on campaign in Hungary and returned with him to Kraków in December 1683 (ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 316).

Michał’s political ascent was swift: less than two years after the battle of Vienna, he was appointed the castellan of Oświęcim, a dignity that conferred a seat in the Senate of the Polish Crown. For the Czerny, this marked a significant advancement, for no family member had sat in the Senate for a century. Notably, four years later, on 23 July 1689, during the drafting of an agreement with Karol Radziwiłł—represented by Bishop of Płock Ludwik Załuski of the Junosza coat of arms, chancellor to Queen Maria Kazimiera—Michał Czerny appeared for the first time with the epithet Szwarcenberg (rendered in the source as Szwarczemburg, ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 324). From that time onward, not only Michał but the entire family styled themselves as Szwarcenberg Czerny of Witowice, Nowina coat of arms.

According to a later family legend, discussed in detail below, Michał’s stay in Vienna was the occasion of a heraldic adoption of the Czerny by the Schwarzenbergs. Several facts, however, contradict this tradition.

As mentioned above, Michał began using this epithet only seven years after the Battle of Vienna, following his appointment as castellan of Oświęcim. At first, he did not even employ it consistently: between 1689 and 1694—that is, until he received the castellany of Sącz—he appeared under the name Szwarcenberg Czerny only once, in 1691 (ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 327). It should also be emphasized that during this same period, all members of the Czerny family began adopting Szwarcenberg as part of their surname. If a heraldic adoption had in fact taken place, only Michał and his descendants would have been entitled to bear the altered coat of arms and surname. Yet from the beginning of the 18th century, the entire family—descendants of Andrzej, Michał’s brother, as well as the children of Bernard’s line—was already known as Szwarcenberg Czerny.

It was only Michał’s sons who consolidated the new form of the name, though even the family itself remained uncertain as to the correct orthography of the epithet they employed. As late as the end of the 18th century, alternative spellings can be found, such as Szwatzemberg (CDIAUL, f. 165). In the 18th century, on most of the Czerny foundations, alongside the Nowina coat of arms, the Schwarzenberg arms were also displayed—yet in a modified form, as will be discussed later. This may have been due either to the patrons’ lack of knowledge of the true design of the arms, or perhaps to the shortcomings of the craftsmen executing the commissions.

In summary, the Battle of Vienna and Michał Czerny’s participation in it became a pretext for the expansion of the family legend. It is worth noting that Czerny stayed abroad only briefly and was already recorded in Kraków sources by the end of 1683. Did he in fact save Prince Schwarzenberg at Vienna? To verify the family legend, it is necessary to examine the princely Schwarzenberg family more closely.

2.4. The Princes of Schwarzenberg

The Schwarzenbergs, as a German-Czech princely family, played a major role not only in the history of Vienna but also in that of the entire empire. They were an ancient lineage: the earliest references to the family’s progenitors date back to the 10th century, specifically to the year 917, when Duke Erchanger of Alemannia from the Seinsheim line was executed. Among his descendants was Erkinger I, who in 1405 acquired the Franconian lordship of Schwarzenberg together with the castle of the same name, and in 1435 purchased the castle of Hohenlandsberg. In 1422 King Sigismund pledged to him the estate of Libenice along with the town of Grunta. Erkinger bore the title of Baron of Schwarzenberg and Hohenlandsberg (von Wurzbach 1877). From that time onward, the family became firmly embedded in the political and social mosaic of the Austrian nobility.

The family bore the Schwarzenberg coat of arms, described as follows: a shield divided vertically into seven alternating fields of argent and azure; upon a helmet with mantling of azure and argent is placed the bust of a bearded man clad in a red tunic with a silver collar and wearing a red, pointed crown with a turned-back silver rim, adorned with three natural peacock feathers; this crest is set between two buffalo horns, each divided vertically into seven fields of azure and argent, within the openings of which are three natural peacock feathers, with seven more feathers along the outer edges (Adelslexikon 2002).

During the Austro-Turkish War, the most prominent representative of the Schwarzenberg family was Prince Ferdinand. Born in 1652 as the eldest son of Prince Johann Adolf and Maria Justina of the Starhemberg family, he remained in Vienna during the great plague of 1679, when he was charged with maintaining order in the city. He fulfilled this task admirably, earning the sobriquet “the plague king.” Austrian accounts emphasize that he was responsible for establishing lazarettos, financing medical care for the sick, and sustaining the morale of the common people.

In 1683, during the Ottoman siege of Vienna, Ferdinand was not in the city but rather in Hungary with the Primate of Hungary, Count György Széchényi. Nevertheless, he did not forget Vienna: in July he donated a substantial sum to support its defenders. His generosity gave rise to a Viennese saying: “Both saved Vienna: Schwarzenberg with gold, and Starhemberg with the sword.” It is worth noting that Ferdinand was related to the commander of the defense, Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, through his mother, who came from the Starhemberg family (von Wurzbach 1877). In 1685, the Emperor appointed him Obersthofmarschall; in 1688 the King of Spain admitted him to the Order of the Golden Fleece; and in 1692 he became Obersthofmeister of the reigning Empress Eleonore Magdalene of Neuburg. He died at the relatively young age of 51 in 1703. It should be emphasized that contemporary sources concerning the defense of Vienna and the relief of 1683 make no mention of a Schwarzenberg participating in these events.

At this point, it must be noted that within the Czerny family there survives a legend, still current among their descendants, according to which Michał—participant in the Battle of Vienna—saved a Schwarzenberg prince during the fighting beneath the city walls. According to tradition, Michał served in the ranks of the hussars. During the final assault on 12 September 1683, he is said to have spotted a Schwarzenberg prince (whose name is not preserved in the family narrative) who had fallen from his horse after being struck in the leg by enemy fire. Michał allegedly dragged him from the chaos of battle and offered him his own horse. Following the victory, the prince, wishing to repay Michał, invited him to his estates in Germany (the Schwarzenberg principality), where he hosted him for several months. During this time, the Polish nobleman and the German prince are said to have become close friends, an association culminating in Michał’s adoption into the Schwarzenberg coat of arms (Materials from the Czerny family archives 1993).

It is also worth noting the striking resemblance of this family legend to the story of the granting of the Nowina coat of arms as recorded by Paprocki. According to his account, Nowina, a captain in the service of Bolesław the Wrymouth and the son of a coppersmith, gave up his horse to the prince during a battle with the Rus’ in 1121. In gratitude for this act of rescue, Bolesław is said to have conferred upon him a coat of arms depicting a cauldron’s handle—an allusion to Nowina’s paternal trade—together with a sword. Paprocki was an immensely popular author among the Polish nobility, and the Czerny family undoubtedly knew the history of their own heraldic tradition.

When the family’s narrative is compared with established historical fact, it becomes clear that no meeting between Michał and a Schwarzenberg prince could have taken place beneath the walls of Vienna. No traces of contact between the Czerny family and the Schwarzenbergs exist either in Polish archival sources or in the Schwarzenberg family archives (Humphreys and Burger 2018). No charter or document survives that would testify not only to an adoption but to any form of connection at all (van Eycken 2011). Moreover, as noted above, had Michał truly been adopted by a Schwarzenberg, he would certainly have begun styling himself Szwarcenberg Czerny immediately. The fact that all members of the family simultaneously began to use “Szwarcenberg” as part of their surname strongly suggests a deliberate effort to ennoble their lineage in the wake of Michał’s social advancement. If an adoption had taken place, the right to bear the altered coat of arms and name would have extended solely to Michał and his descendants. Yet from the early 18th century onward the entire family was known as Szwarcenberg Czerny.

On these grounds, one may hypothesize that Michał Czerny, upon achieving significant social promotion and finding himself compelled to operate within circles of the Polish magnate elite—most of whom belonged to princely houses—sought to elevate his own lineage. During his short stay in Vienna, he was almost certainly exposed to the renowned Schwarzenberg name. Familiar with the story of his family’s heraldic origins transmitted through Paprocki (Paprocki 1584), Michał appears to have drawn a simple association between the two surnames, linked by the root Szwarc (Szwarc–Schwarzenberg). It is therefore unsurprising that he began to style himself a Schwarzenberg only after his promotion, while at the same time betraying no knowledge of the proper spelling of the name or of the exact form of the Schwarzenberg arms (without the errors that occurred earlier).

This interpretation accords well with the testimony of the 19th-century historian and bishop Ludwik Łętowski. Having encountered Cardinal Friedrich Joseph of Schwarzenberg, Prince-Bishop of Prague, Łętowski inquired about possible kinship with the Polish Szwarcenbergs. The cardinal, however, denied any familial connection (Łętowski 1852).

When then did the story of the heraldic adoption by Prince Schwarzenberg arise?

3. The Genealogical Consciousness of the Czerny Family from the 15th Century to the Present

In his study of the medieval nobility of the Land of Sandomierz, Jan Wroniszewski analyzed phenomena associated with the concept of genealogical consciousness. He distinguished genealogical memory, a sense of common descent, and, among other aspects, representations of a family’s past. The emphasis placed on the antiquity of a lineage, its significance, and the celebrated deeds of its ancestors reflected contemporary social aspirations (Wroniszewski 2001).

In the case of the Czerny family, one may trace several stages in the development and transformation of genealogical consciousness. At the turn of the fifteenth and 16th centuries, the family’s identity underwent its first significant change. Until the 1490s, Paweł most often appeared with the predicate famosus and the surname Szwarc or Czarny (ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 429). With the assumption of further offices, he began to be designated as dominus, and from the beginning of the 16th century as generosus. At this time, as noted above, he acquired Witowice and initiated the process of withdrawing from the urban milieu. Moreover, owing to his wealth, he established connections with the royal court, extending numerous loans—certainly to King Alexander, and possibly also to John Albert.

Here lies the key to the question of whether Paweł and his ancestors belonged to the petty nobility settled in Kraków, or whether they were townsmen who, through significant material advancement, claimed noble status. Paweł’s career path closely resembles that of Jerzy Szwarc, who had risen more than fifty years earlier by enriching himself through mercantile expeditions, thereby strengthening his influence and attaining offices (Jerzy as a Kraków councillor, Paweł as Bachmistrz and żupnik). For both, the next step was linking themselves to the royal court by extending loans to the monarch.

Jerzy succeeded in securing ennoblement for himself and his descendants. Nevertheless, the Szwarc family remained in the city, continued their mercantile pursuits, and the tenuous reminder of their “ennoblement” was the coat of arms, which they appear to have used inconsistently. In the case of Paweł Czarny, there is no evidence of formal ennoblement (Wajs 1995). Upon acquiring Witowice, he merely “changed” his predicate and the form of his surname (from Szwarc to Czarny), styling himself “generosus Paulus Czarny de Withowice.” For the record, before these events Paweł was most often recorded as Szwarc, though numerous entries refer to him as Czarny or even Niger. As noted, this largely depended on the language in which a given source was written.

This does not alter the fact that the Czerny family belonged to the petty nobility, most likely originating from the Proszowice district (Strzelce Wielkie) or from the Książ area. One of their members, probably at the beginning of the 15th century, came to Kraków to engage in commerce, thereby securing a stable income. This would constitute the first shift in status. The second occurred several decades later, when the family transformed from an urban merchant household into a noble one.

A further change came in the mid-16th century, when the family began to write themselves as Czerny rather than Czarny, as had previously been the case (AGAD, Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego, Div. IV [Books of Recognition], sig. 4).

More than a century later, another change occurred in the identification of the Czerny family. As mentioned earlier, Michał, castellan of Oświęcim and Sącz, starost of Parnawa, and participant in the Vienna campaign, began to use the byname Schwarzenberg. Other members of the family soon adopted this practice as well, practically within the same year, and by the 18th century they appeared as the Schwarzenberg-Czerny family of Witowice, bearing the Nowina coat of arms. In the 18th century they also began to append the Schwarzenberg coat of arms to their Nowina, in order to emphasize more strongly their connection with this princely house. Examples include the epitaph of Salomea Czerny, widow of Stanisław Czerny, in the Church of St. Casimir of the Franciscan Reformers in Kraków (Figure 4), as well as the epitaph of Franciszek Ksawery, castellan of Wojnicz, in the Church of the Stigmata of St. Francis of Assisi in Alwernia. The Schwarzenberg arms were represented somewhat incorrectly, but there is no doubt that they were intended. The error may have arisen either from the lack of skill of the artisan or from the ignorance of the patron. It is noteworthy, however, that in every Czerny foundation the Schwarzenberg arms were depicted in the same manner—first a white band, then a black one—whereas in the authentic Schwarzenberg arms the alternation is reversed, with black (or, more often, blue) preceding white.

Figure 4.

The Abdank, Nowina, and Schwarzenberg coats of arms on the epitaph of Salomea of Nielepce in the Reformed Franciscan Church in Kraków.

From the 18th century also survives an interesting literary work: Herculeum non plus ultra by Romuald Fludziński, professor at the University of Kraków. In its dedication, a detailed genealogy of the Czerny family is presented, beginning with Paweł Czerny, the Kraków’s saltmaster (żupnik) living at the turn of the fifteenth and 16th centuries, and carefully tracing the successive generations of the family (Fludziński 1751). The entire work was conceived as an apotheosis of the heroic deeds of successive members of the family on the battlefield. Through comparisons to ancient heroes and gods, the author sought to highlight their merits for the homeland. It is worth noting that relatively few errors were committed in this account, which suggests that genealogical memory at this time was exceptionally resilient (Brzegowy 2023). This observation accords with the broader pattern among noble families in the early modern period, who devoted much care to preserving family memory.

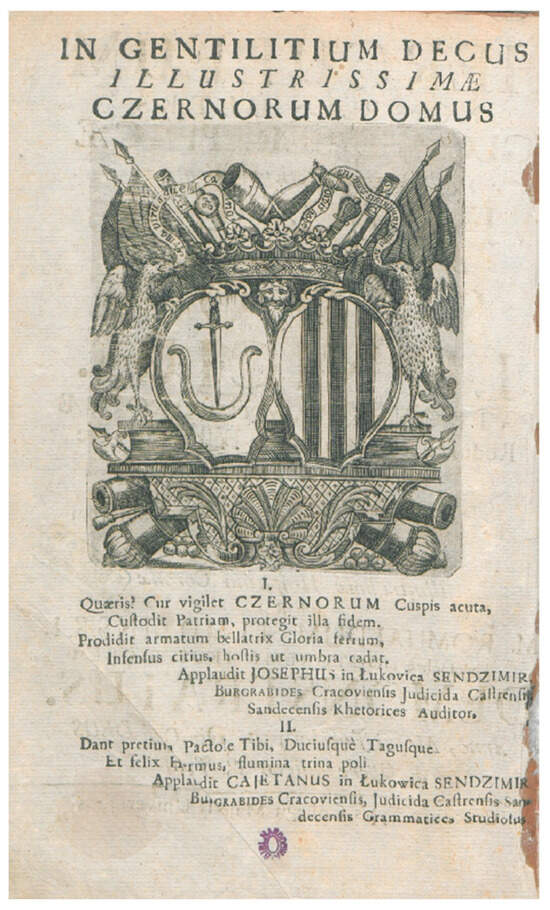

As mentioned earlier, despite persistent efforts, the family lacked an abundance of military heroes. Hence, in Herculeum considerable space is devoted to Mikołaj, who fell at Pskov and was compared to Achilles (the mythological motif of the vulnerable heel corresponded aptly with Mikołaj’s death, caused by a shot to his heel). The second hero celebrated was Michał Czerny, participant in the victory at Vienna. Interestingly, in the passage devoted to him, no mention was made of heraldic adoption by the Schwarzenbergs. Although the princely coat of arms was placed on the title page, the text offered no explanation as to how it entered the family’s tradition (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The dedication page of Herculeum non plus ultra by Romuald Fludziński.

In the 19th century, following the partitions of Poland and the loss of statehood, the Czerny family—like many other Polish noble families—focused less on the apotheosis of their ancestors and more on ensuring their livelihood within the new legal framework. The partitioning powers required nobles to provide proof of their descent. Compelled by this obligation, the Czerny family also attested to their lineage: in 1844 Piotr Paweł Czerny confirmed his nobility in the Kingdom of Poland, that is, in the Russian partition (Boniecki 1900), omitting entirely the byname Schwarzenberg.

The issue resurfaced during the First World War. In 1915 Dr. Bolesław Schwarzenberg-Czerny submitted an inquiry to the National Department in Lwów regarding the ancestry of his family (CDIAUL, f. 165). In its reply, the Department confirmed no ties with the Schwarzenbergs but did recall the noble certification of Czerny from 1844. After the rebirth of the Polish Republic in 1918, descendants of nobles from the era of the First Commonwealth began to seek out their ancestors, tracing glorious deeds and heroic conduct. It was most likely at this time that the Czerny family legend emerged, suggesting that Michał Czerny had saved Prince Schwarzenberg at Vienna and that, in gratitude, he was adopted into the family’s coat of arms.

Living descendants point unambiguously to Maria Stokłosa, née Schwarzenberg-Czerny (born in 1920), as the person who, in her youth, told them of the heroic Michał. She herself cited the stories of her father, who was said to have recalled the great achievements of his forebears (Materials from the Czerny family archives 1993). It may therefore be concluded that the family legend arose in the context of Poland’s regained independence in the early 20th century, as a reworking of the older heraldic legend recorded in the works of Bartosz Paprocki (Figure 6).

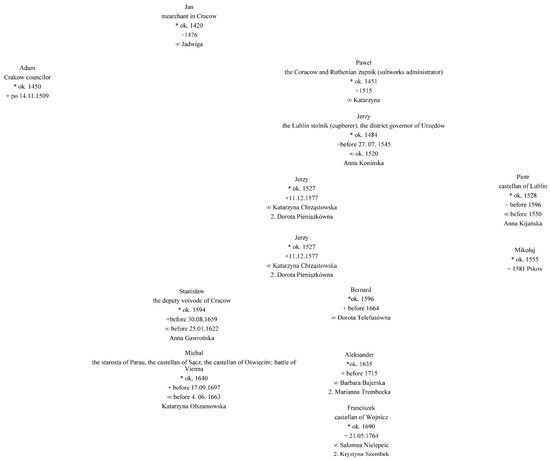

Figure 6.

Simplified genealogy of the Czerny family (Nowina coat of arms) (*—born).

4. Materials and Methods

The article applies the method of historical analysis, involving a critical interpretation of written sources and their comparison across the longue durée. The author employed the genealogical method, tracing the lineage of the Czerny family on the basis of municipal registers, wills, and other records. A prosopographical approach was also used, juxtaposing the careers of family members with those of other representatives of the Kraków urban and noble elites. Elements of narrative analysis allowed for the reconstruction and interpretation of heraldic legends preserved in family memory. The research drew on archival materials from the National Archives in Kraków, including municipal and court books, as well as records preserved in the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw and the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv. Printed sources were also utilized, such as the “Books of Admission to Kraków’s Municipal Law,” diaries, and panegyric works from the sixteenth to 18th centuries. A key point of reference was the oeuvre of heraldists, particularly Bartosz Paprocki and Kasper Niesiecki. The bibliography further includes modern historical studies (e.g., Wroniszewski, Kutrzeba, Jasienica) alongside editions of genealogical and heraldic records. Valuable material was also provided by testimonies of family memory, preserved in oral tradition and 19th- and 20th-century literature. Overall, the study is based on the triangulation of sources, combining archival, literary, and genealogical evidence with the social and political context of successive epochs.

5. Conclusions

This article presents the Czerny family as an instructive example of the formation and transformation of heraldic memory, and of the evolution of heraldic legends across the longue durée—from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. The analysis demonstrates that the genealogical memory of this family was exceptionally enduring, though subject to gradual reinterpretation, adapted to shifting social and political conditions.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Czerny family (also known as Czarny) sought to consolidate their noble status by combining mercantile activity with the use of the Nowina coat of arms. The legend of this coat of arms, allegedly granted by Bolesław the Wrymouth, soon became linked to the fates of the family’s members—particularly to Mikołaj Czerny, who died at Pskov—thus reinforcing the narrative of hereditary heroism. Heraldic tradition was thereby enriched with new motifs corresponding to the family’s representational needs.

The next stage of reinterpretation came in the 17th century. Michał Czerny, participant in the relief of Vienna, introduced the element “Schwarzenberg” into his name, and soon the entire family adopted both the designation and the Schwarzenberg arms. This practice expressed aspirations to elevate the family’s prestige, though no evidence survives of any genuine heraldic adoption by the Austrian princes. Over time, the narrative transformed into a family myth, preserved in oral tradition into the 20th century. In this sense, it exemplifies the creative reconstruction of heraldic memory, built upon analogies to earlier tales (such as that of Nowina), yet firmly anchored in family identity.

In the early modern period and beyond, these legends underwent further reinterpretations—from baroque apotheoses in panegyrical literature, through 19th-century processes of noble legitimization, to the revival of the “Viennese adoption” narrative during the First World War and the Second Republic. This mechanism demonstrates that the heraldic memory of the Czerny family functioned as a dynamic cultural construct: preserved in material evidence (epitaphs, heraldic emblems on foundations), in the literature, and in oral traditions, while being continually reshaped in accordance with contemporary aspirations to prestige.

In summary, the history of the Czerny family illustrates how heraldic memory could serve as a tool of legitimization and self-presentation. The evolution of their heraldic legends—from the tale of Nowina’s heroism to the myth of adoption by the Schwarzenbergs—points both to the continuity of memory and to its susceptibility to transformation, shaped by the logic of social ambition and symbolic strategy. The findings of this study position the Czerny family as a revealing case within wider European research on the construction, transmission, and reinvention of noble memory. By tracing the longue-durée evolution of heraldic legends in a Central European milieu, the article contributes to comparative inquiries into how aristocratic and patrician families across Europe—whether in France, the German lands, or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—mobilized genealogical narratives to assert status and continuity. The mechanisms observed in the Czerny case, including the creative adaptation of coats of arms, the strategic incorporation of prestigious lineages, and the reliance on both written and oral traditions, parallel dynamics documented in Western European heraldic cultures. In this sense, the study reinforces the growing recognition that heraldic memory operated as a shared European cultural practice: at once locally rooted and structurally analogous across regions. By bringing forward material from Central and Eastern Europe, the article not only broadens the geographical scope of current debates but also demonstrates the methodological value of microhistorical case studies for understanding the universal, yet locally inflected, processes of genealogical self-fashioning.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

(AGAD, Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego, Div. IV [Books of Recognition], sig. 4) Central Archives of Historical Records. Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego. Div. IV [Books of Recognition], sig. 4. pp. 309–10.(AGAD MK sig. 17) Central Archives of Historical Records. Metryka Koronna. sig. 17. p. 356.(ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 316) National Archive in Krakow. Castrensia Cracoviensia. sig. 316. pp. 2333–35.(ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 324) National Archive in Krakow. Castrensia Cracoviensia. sig. 324. pp. 1951–54.(ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 327) National Archive in Krakow. Castrensia Cracoviensia. sig. 327. pp. 2549–53.(ANK Castr. Crac. sig. 39) National Archive in Krakow. Castrensia Cracoviensia. sig. 39. pp. 325–26.(ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 428) National Archive in Krakow. Consularia Cracoviensia. sig. 428. p. 273.(ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 429) National Archive in Krakow. Consularia Cracoviensia. sig. 429. pp. 171, 659–60.(ANK Cons. Crac. sig. 430) National Archive in Krakow. Consularia Cracoviensia. sig. 430. p. 369.(APL Castr. Lub. sig. 29) State Archive in Lublin. Castrensia Lublinensia. sig. 29. pp. 333–34.(CDIAUL, f. 165) Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv. f. 165. op. 3. Vol., 5046. pp. 11, 20–21.(Materials from the Czerny family archives 1993) Materials from the Czerny family archives. 1993. Held by the Sekutowicz family. p. 79.Secondary Sources

- Adelslexikon. 2002. Limburg an der Lahn: Starke, vol. 13, p. 202.

- Assmann, Johann. 2005. Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Munich: CH Beck, p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniak, Janusz, ed. 2002. Rody rycerskie jako czynnik struktury społecznej w Polsce XIII–XV wieku (uwagi problemowe). Polskie rycerstwo średniowieczne. Kraków: Societas Vistulana, pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boniecki, Adam. 1900. Herbarz polski. Warszawa: Gebethner and Wolff, vol. 3, pp. 378–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, Constance Brittain. 2001. Those of My Blood: Creating Noble Families in Medieval Francia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 4–13, 14–50. [Google Scholar]

- Broadway, Jan. 2013. Symbolic and Self-Consciously Antiquarian: The Elizabethan and Early Stuart Gentry’s Use of the Past. Huntington Library Quarterly 76: 541–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brzegowy, Joanna. 2023. Kanonik krakowski Franciszek Szwarcenberg Czerny (1710-1775) i jego wywód przodków. Studia z dziejów katedry na Wawelu. Edited by Ewelina Zych. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka, pp. 203–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brzegowy, Joanna. 2024. Rodzina Czernych herbu Nowina w średniowieczu i czasach nowożytnych stadium kariery. Warszawa: Tadeusz Manteuffel Insitut of History. Polish Academy of Sciences, pp. 30–56, 70–80, 270–72. [Google Scholar]

- Coss, Peter R. 2002. Knighthood, Heraldry and Social Exclusion in Edwardian England. In Heraldry, Pageantry, and Social Display in Medieval England. Edited by Peter R. Coss and Maurice Keen. Martlesham: Boydell Press, pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Damen, Mario, and Marcus Meer. 2022. Heraldry and Territory: Coats of Arms and the Representation and Construction of Authority in Space. In Constructing and Representing Territory in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Mario Damen and Kim Overlaet. London: Routledge, pp. 243–76. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, Jan. 1887. Insignia seu clenodia. Poznań: Biblioteka Kórnicka, p. 569. [Google Scholar]

- Drane, Augusta. 1858. The Knights of st. John: With The battle of Lepanto and Siege of Vienna. London: Burns and Oates, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Tanya. 2011. Secrets and Lies: The Radical Potential of Family History. History Workshop Journal 71: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fludziński, Romuald. 1751. Herculeum non plus ultra […]. Kraków: Jagiellonian Library, sig. St. Dr.220023 III. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Adam. 1999. Remembering the Past in Early Modern England: Oral and Written Tradition. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 9: 233–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. The Social Frameworks of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 54–84. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Humphreys, Nicola, and Daniel Burger. 2018. Highlights aus dem Schwarzenberg-Archiv: Eine Ausstellung des Staatsarchivs Nürnberg im Knauf-Museum Iphofen. Munich: Generaldirektion der Staatlichen Archive Bayerns. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Janicki, Marek. 2001. Pochówki i pamięć poległych: XVI–XVII w. Napis. Pismo poświęcone literaturze i okolicznościowej, i użytkowej 7: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasienica, Paweł. 1982. Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów. Calamitatis regnum. Warszawa: PIW, pp. 66, 367–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk, Kazimierz, ed. 1913. Księgi przyjęć do prawa miejskiego w Krakowie 1392–1506. Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press, nr 2605, 3197, 3569, 4058, 4383, 4780, 5583, 5623, 5826, 6194, 6506. [Google Scholar]

- Kmita, Jan Achacy. 1609. Phoenix. k. 1v. Kraków: Czartoryski Library, sig. 38130. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanowski, Jan. 1883. Nagrobek dwiema braciej. Fraszki. Księgi trzecie. Kraków: Bartoszwicz Press, p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalik-Kaleta, Zofia. 2007. Historia nazwisk polskich na tle społecznym i obyczajowym (XII–XV wiek). Kraków: Wydawnictwo I Drukarnia Kurii Prowincjonalnej Zakonu Pijarów, vol. 1, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Kuraś, Stanisław, ed. 1969. Zbiór dokumentów małopolskich. Vol. 3: Dokumenty z lat 1442–1450. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków: Polish Academy of Sciences, p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Kutrzeba, Stanisław. 2009. Finanse i handel średniowiecznego Krakowa. Edited by Warszawa Rehman. Warszawa: Avalon, pp. 223–24. [Google Scholar]

- Łętowski, Ludwik. 1852. Katalog biskupów, prałatów i kanoników krakowskich. Kraków: Jagiellonian Univeristy Press, vol. 2, p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Niesiecki, Kasper. 1841. Herbarz polski. Edited by Jan Nepomucen Bobrowicz. Lipsk: Breitkopf and Haertel Press, vol. 6, p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Odrowąż-Pieniążek, Jerzy, ed. 1933. Rycerstwo polskie w wyprawie wiedeńskiej pod wodzą króla Jana III Sobieskiego w roku 1683 roku. Warszawa: Sekcja Rodowa Komitetu Obchodu 250-lecia odsieczy Wiednia, p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Pajewski, Janusz. 1978. Buńczuk i koncerz: Z dziejów wojen polsko-tureckich. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, pp. 258–62. [Google Scholar]

- Paprocki, Bartosz. 1578. Gniazdo cnoty skąd herby rycerstwa sławnego Królestwa Polskiego, Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, Ruskiego, Pruskiego, Mazowieckiego, Żmudzkiego i inszych państw do tego królestwa należących książąt i panów początek swój mają. Kraków: Andrzej Piotrkowczyk. [Google Scholar]

- Paprocki, Bartosz. 1584. Herby rycerstwa polskiego. Kraków: Maciej Garwolczyk. [Google Scholar]

- Piekosiński, Franciszek, and Stanisław Krzyżanowski, eds. 1910. Akta historyczne do objaśnienia rzeczy polskich służące. Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, vol. 12, pp. 1372–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ptaśnik, Jan. 1905. Bonerowie. Rocznik Krakowski 7: 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rogulski, Jakub. 2017. Memory of Social Elites. What Should Not Be Forgotten: The Case of the Lithuanian Princes in the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. The Court Historian 22: 189–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogulski, Jakub. 2019. Genealogia rodu Sanguszków księcia Symeona Samuela Sanguszki. Studia Źródłoznawcze. Commentationes 56: 155–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Slezáková, Miroslava. 2011. Members of the Merchant Guild in Košice in the Middle Ages. Contribution to the Research of Town Elites in Košice in the Middle Ages. Mesto a Dejiny 1: 16–25. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Starzyński, Marcin. 2014. Szwarc Adam. Polski Słownik Biograficzny 49: 436–37. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Urwanowicz, Jerzy. 1996. Diariusz oblężenia Pskowa. In Zeszyt Naukowy Muzeum Wojska w Białymstoku. Białystok: Muzeum Wojska, vol. 10, p. 144. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- van Eycken, Katherina. 2011. Die Schwarzenbergs. Ein fränkisch-böhmisches Adelsgeschlecht. Chisinau: Doyen Verlag. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wajs, Anna, ed. 1995. Materiały genealogiczne, nobilitacje, indygenaty w zbiorach Archiwum Głównego Akt Dawnych w Warszawie. Warszawa: DiG. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wiśniewska, Halina. 2006. Renesansowe życie i dzieło Sebastiana Fabiana Klonowica. Lublin: Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej, pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wójcik, Zbigniew. 1991. Jan III Sobieski. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo zamku Królewskiego, pp. 11, 34, 37, 50–51. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wroniszewski, Jan. 2001. Szlachta ziemi sandomierskiej w średniowieczu. Zagadnienia społeczne i gospodarcze. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Historyczne, pp. 187–88. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- von Wurzbach, Constanti. 1877. Das Fürstenhaus Genealogie. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich. New York: Legare Street Press, vol. 33, pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wysmułek, Jakub, ed. 2017. Katalog testamentów z krakowskich ksiąg miejskich do 1550 roku. Warszawa: Neriton, nr 418, 436, 1280. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ziemierski, Maciej. 2014. Szwarcenberg Czerny Michał. Polski Słownik Biograficzny 49: 455–56. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).