Abstract

This article formulates and evaluates historical hypotheses on the origin and formation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo (León) within the broader dynamics that connected the urban patriciate and the rural hidalguía (minor nobility) of late medieval and early modern Castile. Through an integrated examination of population registers, parish records, hidalguía lawsuits, and notarial protocols, the study reconstructs the family’s trajectory and its institutional anchoring in the concejo and parish. The evidence suggests an urban origin on León’s Rúa through Doña Elena de Villafañe y Flórez, whose marriage to Ares García—an hidalgo from the Ordás area—established the local house and the compound surname “García de Villafañe” as both an identity marker and a patrimonial device. The consolidation of the lineage resulted from deliberate family strategies, including selective alliances with neighboring lineages (Quiñones, Gavilanes, Rebolledo), participation in municipal and ecclesiastical offices, and the symbolic use of heraldry and memory. The migration of Lázaro de Villafañe to colonial La Rioja and Cordova in the seventeenth century extended this social status across the Atlantic while maintaining Leonese continuity. Although the surviving evidence is fragmentary, convergent archival, onomastic, and heraldic indicators support interpreting the Molinillo branch as a legitimate and adaptive extension of the urban lineage. By combining genealogical and microhistorical analysis with interdisciplinary perspectives—particularly gender and genetics—this article proposes a transferable framework for testing historical hypotheses on lineage continuity, social mobility, and identity formation across early modern Castile and its transatlantic domains.

1. Introduction

This article proposes and evaluates historical hypotheses regarding the origin and formation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo (León), presenting it as a case study within the broader context of rural social history in the Kingdom of León. Rather than understanding genealogy as a simple enumeration of kinship ties, this study employs it as an analytical tool to explore how families made strategic decisions—whom to marry, which municipal offices to pursue, and how to preserve memory and assets across generations. Within this framework, figures such as Elena de Villafañe (or Villafañe y Flórez), Ares García, and Lázaro de Villafañe serve as focal nodes for analyzing the intersection of kinship, office-holding, and social reproduction from the late Middle Ages to the eighteenth century.

The analysis centers on Santiago del Molinillo and its surrounding territory, covering a chronological span from the first appearance of the surname in local records during the late Middle Ages to the eighteenth century. Particular emphasis is placed on the sixteenth century, when the lineage becomes fully traceable in notarial and ecclesiastical documentation. By reconstructing the ancestry of Doña Elena de Villafañe and Ares García, the study investigates how their household was structured, how it interacted with local institutions (such as the concejo and parish), and how it ensured continuity through privileges, municipal participation, and alliances with neighboring lineages such as the Quiñones, Gavilanes, and Rebolledo.

Tracing these origins illuminates the later trajectory of their descendants—most notably Lázaro de Villafañe, who migrated to the Indies—revealing how local rootedness and external mobility coexisted within a single family strategy. These practices exemplify the adaptive mechanisms of the minor nobility (hidalguía), who relied on kinship, reputation, and office-holding to sustain social status in a changing political and economic landscape. For clarity, hidalguía refers to the non-titled hereditary nobility of Castile. Unlike titled lords, hidalgos enjoyed legal and fiscal privileges by birth (hijosdalgo de sangre), often linked to a recognized ancestral house (solar conocido), although they did not necessarily exercise jurisdictional authority (ARChV 1677).

The Villafañe surname, originally of Leonese origin, gained early prominence in urban government through members such as Nuño González de Villafañe (judge, 1351), Álvaro González de Villafañe (judge, 1386), and Pedro Núñez de Villafañe (councillor, 1391). Over the following centuries, branches of the family spread across León—in Almanza, Renedo de Valdetuéjar, Cuadros, the upper Bernesga, Navatejera, and other settlements—retaining their status as hidalgos notorios, holding local offices, and defending their nobility before royal and municipal jurisdictions (Sánchez Badiola 2019).

In Santiago del Molinillo, the local casa solar (ancestral seat) appears in the 1761 padrón of Ordás and in earlier genealogical declarations by Ramiro de Villafañe y Guzmán (1618) and Luis de Villafañe y Barba de Guzmán (Serrano Redonnet 1944). Among its members, Ares García served in municipal offices and held parish privileges, including a distinguished burial (Serrano Redonnet 1967). His son, Lázaro de Villafañe, described as an “hijodalgo notorio de solar conocido,” emigrated to the Indies in 1610, where he served as encomendero and Lieutenant Governor in Todos los Santos de la Nueva Rioja (Villafañe 2022).

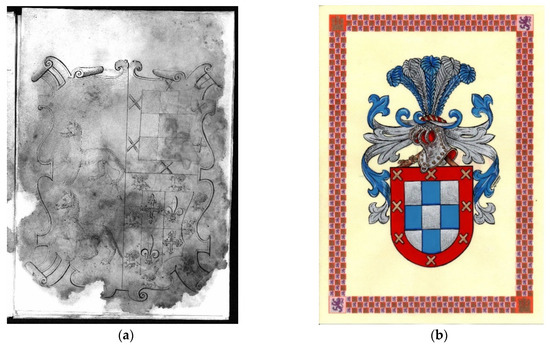

The trajectory of Lázaro and his relatives exemplifies the articulation between local networks and overseas mobility that characterized numerous rural lineages in the early modern period (Boixadós 2003, 2004, 2011; Farberman and Boixadós 2006; Moyano Aliaga 2003; Villafañe 2023, 2024, 2025). The persistent use of the compound surname “García de Villafañe”, combined with continued participation in civic and religious offices, demonstrates a deliberate strategy of identity preservation. The lineage’s heraldic coat of arms—chequy argent and azure with a bordure gules charged with eight saltires Or—first attested in the mid-sixteenth century and officially certified in Segovia in 2023, further reinforced its symbolic legitimacy (ARChV 1546; Serrano Redonnet 1944; Toranzo 2018). This description was officially certified in Segovia in 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Arms for the grille of Francisca de Villafañe, 1546. ARCHV, Pleitos Civiles, Varela (O), C. 1051-1; (b) Certification of arms for the Villafañe lineage, Segovia, 2023.

Beyond its local significance, the study of the Villafañe lineage sheds light on broader processes of transmission and adaptation of Castilian social models in colonial settings. The documented connections between Santiago del Molinillo, colonial La Rioja, and Cordova (Argentina) illustrate how hidalguía, kinship, and municipal governance practices were transplanted and reconfigured in the Americas, contributing to the formation of colonial elites (Moxó and de Villajos 1968; Ortiz and Palomeque 2008).

What makes the Villafañe lineage particularly suitable for this analysis is the exceptional continuity and abundance of archival documentation that allows the reconstruction of its trajectory across several centuries. Few lineages of minor hidalguía display such a consistent presence in notarial, judicial, and ecclesiastical records—from fifteenth-century León to seventeenth-century La Rioja—which makes it possible to test hypotheses over time regarding origin, adaptation, and mobility. This depth of evidence transforms the Villafañe family into a uniquely traceable case, offering a reliable empirical foundation to explore the mechanisms through which rural nobility articulated identity, power, and social reproduction from medieval Castile to the colonial Andes. The study’s relevance thus lies not only in its local specificity but also in its capacity to model how genealogical microhistory can illuminate wider processes of continuity and transformation within the early modern Hispanic world (Boixadós 2003, 2004, 2011; Farberman and Boixadós 2006; Moyano Aliaga 2003; Quiroga 2012; Villafañe 2023, 2024, 2025).

Methodologically, the study integrates historical genealogy, social history, and microhistory to examine the Villafañe lineage not as a biology but as a social construction that articulates memory, status, and power across generations. This interdisciplinary approach enables a reconstruction of kinship networks and patrimonial strategies that illuminate how rural elites articulated their position within broader institutional and territorial frameworks. In the local context of Santiago del Molinillo, the surname “Villafañe” operated as an instrument of social distinction—organizing alliances, legitimizing access to municipal and ecclesiastical offices, and perpetuating symbolic capital through heraldic and documentary representation. Concepts such as hidalguía, patronymic continuity, and succession practices—often inspired by the logic of mayorazgo even in the absence of formal entail—help explain how intergenerational reproduction and social mobility functioned among minor rural nobility in the Kingdom of León.

The main objective of this article is to formulate and assess plausible hypotheses regarding the origin and formation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo, while situating it within the broader dynamics of Castilian and transatlantic nobility. By analyzing the transmission of the surname, marriage strategies, social and institutional ties, and the Atlantic mobility that connected León with colonial La Rioja and Cordova, the study seeks to reveal how a local noble house adapted to changing historical contexts while maintaining its social prestige. This exploratory and comparative approach contributes to understanding the mechanisms through which rural lineages from northern Castile projected their identity and institutional models to the New World, shaping the foundations of colonial elites and offering a transferable framework for future studies on social reproduction, mobility, and family strategies in early modern societies.

State of the Art

Research on the Villafañe lineage remains fragmentary and dispersed, with a predominant focus on branches of higher nobiliary visibility linked to the eponymous solar in the province of León. Classic genealogical work—most notably by Serrano Redonnet and members of the Instituto Argentino de Ciencias Genealógicas—has traced the surname’s trajectory in the Americas, particularly in the Río de la Plata sphere (Serrano Redonnet 1944). However, this emphasis on prominent lines leaves little systematic analysis of local origins in small rural nuclei such as Santiago del Molinillo.

Traditional reconstructions lean heavily on proofs of nobility, service records to the Crown, and printed genealogies, privileging legitimate male lines and recognized titles. This perspective has tended to eclipse minor or rural branches, especially cases—like the Villafañe of Santiago del Molinillo—whose identity was shaped through local kin networks, municipal office-holding (concejo), and under-documented strategies of social reproduction.

For Santiago del Molinillo specifically, there is no monographic study that addresses the presence and evolution of the Villafañe in the locality. Mentions appear sporadically in seventeenth-century population registers (padrones), parish records, and hidalguía suits, but their interpretation requires a systematic approach integrating genealogical, socioeconomic, and territorial dimensions.

Regional historiography on the Montaña de León has tended to prioritize ecclesiastical, agrarian, or demographic perspectives, often sidelining family dynamics as a structuring principle of local power. This gap is striking given the long durée role of rural hidalguía in reproducing social hierarchies and stabilizing small settlements in the early modern period.

Studying rural lineages also entails methodological challenges: discontinuous documentation; onomastic mobility (e.g., Villafañe used as first or second surname, or transmitted through maternal lines); and the need to reconstruct trajectories from scattered, fragmentary clues. These constraints demand attention to local naming practices, logics of succession, and concrete territorial anchoring.

Despite these difficulties, documentary indicators allow for grounded hypotheses regarding the projection and consolidation of the Villafañe in Santiago del Molinillo. The recurrent presence of the surname since the sixteenth century; its association with municipal offices; participation in hidalguía suits; and its linkage with neighboring lineages—García, Ordás, Quiñones, Gavilanes, Rebolledo—suggest a family network that operated as a mechanism of transmission of status, power, and resources in the Leonese rural milieu.

Taken together, the literature reveals a notable absence of microhistorical studies that situate the Villafañe within local dynamics of hidalguía, social mobility, and Atlantic expansion. Addressing this lacuna, the present article proposes an exploratory, family-centered analysis to understand how minor rural lineages in the Kingdom of León articulated urban connections, kin alliances, and migration to the Indies within broader patterns of intergenerational social reproduction.

2. Materials and Methods

This study on the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo draws on a diversified corpus of primary sources selected for their genealogical relevance and their capacity to illuminate the lineage’s social, familial, and patrimonial configuration. The materials comprise municipal population registers, parish registers (baptisms, marriages, burials), hidalguía lawsuits, notarial records, and archival documentation preserved in the Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (ARCHV), the Archivo Histórico Provincial de León (AHPL), and, for Atlantic connections, the Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de Córdoba (AHPC, Argentina).

2.1. Primary Sources

Population registers: Especially the 1614 and 1761 enumerations for the Ordás area and Santiago del Molinillo, used to reconstruct the continuous presence of the Villafañe surname, kin ties, property holdings, and local officeholding.

- Hidalguía lawsuits: Proceedings before the Royal Chancery of Valladolid documenting claims to nobility, kin networks, patrimonial assets, and local bonds of fidelity.

- Parish registers: Baptism, marriage, and burial books essential for tracing lines of descent, marital patterns, and social/territorial mobility.

- Notarial documentation: Deeds of sale, wills, donations, and pious foundations that reflect economic strategies and mechanisms of family memory preservation.

- Archival holdings: Targeted searches in civil litigation series, final judgments (ejecutorias), and related fonds at ARCHV and AHPL; AHPC is consulted to trace migration trajectories to the Americas.

2.2. Document Selection Criteria

Priority was given to documents meeting one or more of the following:

- Direct mention of the surname Villafañe, whether as first or second surname;

- Explicit references to kinship (filial links, marriages, wills);

- Indicators of social status, such as hijodalgo condition, municipal offices, or notable property;

- Territorial belonging to Santiago del Molinillo or its immediate area of influence (Ordás, Cuadros, Montaña de León).

2.3. Limitations and Methodological Challenges

The analysis faces constraints inherent to fragmentary historical series:

- Discontinuity of records, notably in parish registers prior to the eighteenth century, due to losses and gaps in population rolls;

- Underrepresentation of female lines, which hinders the reconstruction of marital alliances and patrimonial transmission through women;

- Patronymic ambiguities and surname variability, including the strategic use of “Villafañe” as a second surname to bolster local prestige.

2.4. Analytical Approach

The methodological framework combines historical genealogy and microhistory:

- Cross-source triangulation: Systematic confrontation of disparate document types to validate filiations, kin relations, and geographic localization;

- Hypothesis building: Formulation of reasoned genealogical hypotheses from convergences in onomastics, space, and status;

- Onomastic and residential patterning: Analysis of the persistence of given names, compound surnames, and residential clustering as indicators of lineage continuity;

- Identity-transmission strategies: Attention to the adoption and conservation of illustrious surnames in rural contexts as a means to maintain or reinforce symbolic capital.

This combined strategy mitigates, in part, the fragmentary nature of the sources and enables plausible interpretations of the configuration of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo, while maintaining interpretive caution and openness to future research. Embracing historical genealogy as the analytical frame entails acknowledging documentary limits typical of lesser rural lineages and prioritizing plausible hypotheses over closed, fully resolved genealogical trees. In this sense, the exploratory and hypothetical stance aligns with microhistorical principles, privileging close analysis of local, peripheral family dynamics as a lens onto broader social processes.

3. Results

3.1. Hypotheses on the Origin of the Surname Villafañe

Provenance from the Patrician House on the Rúa of León

One of the most robust hypotheses regarding the origin of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo posits a direct descent from the patrician house established on the Rúa of León, one of the city’s oldest and most prestigious thoroughfares. From the fourteenth century onward, the family is documented as holding high-ranking offices in municipal government: Nuño González de Villafañe, judge in 1351; Pedro Núñez de Villafañe, councillor (regidor) in 1391; his son Juan, also councillor and warden (alcaide) of the Towers; and Diego and Rodrigo de Villafañe, delegates (procuradores) to the Cortes in 1442 and 1449. Members of the lineage also held lordships over various jurisdictions—such as the Torío valley, Villaverde de Arriba, Almanza, and Buiza—evidence of the family’s enduring prestige across the centuries (Sánchez Badiola 2019).

The Rúa of León, where the Villafañe family is recorded as residing between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, was historically one of the city’s most significant urban spaces. In the last third of the fourteenth century, under the reign of Henry II (1369–1379), the new Royal Palaces were erected there, replacing the older complex located near San Isidoro. This transformation entailed not only a functional shift but also a symbolic re-signification: the new palaces, designed with clear Mudéjar influences, incorporated gardens, reflecting pools, stucco decoration, and towers, evoking the aesthetic of Islamic alcázares. The water supply for these buildings was secured through a sophisticated system of weirs and channels drawing from San Isidoro (Sánchez-Bordona et al. 2003).

The Rúa of León, incorporated within the city’s second walled circuit and closely connected to the Camino de Santiago, experienced notable growth from the twelfth century onward as a commercial and residential axis (Menéndez Pidal 1962). Its buildings housed merchants, artisans, and members of the urban patriciate, while many of its properties belonged to the cathedral chapter (Fernández 2002), underscoring the economic and symbolic weight of this urban artery. Among its most notable structures was the Conceptionist convent, installed in the former palace of the Quiñones family (Sánchez-Bordona et al. 2003). Despite the progressive deterioration of the Royal Palaces during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Rúa retained its prestige, remaining associated with the administrative, commercial, and residential activities of León’s elites (Sánchez-Bordona et al. 2003). Enlightenment reforms in the mid-eighteenth century prompted the relocation of prison functions and the public granary to new buildings, transforming the old royal precinct into a textile factory and, later, a barracks; nevertheless, the Rúa preserved its standing as one of León’s oldest and most emblematic historic districts.

This concentration of economic, political, and symbolic power around the Rúa of León reinforces the hypothesis that the Villafañe settled on that street belonged to the highest strata of urban society, closely tied to the kinship and clientage networks that structured municipal and ecclesiastical power (Fernández 2002).

The geographic and social linkage between the Villafañe of the Rúa and the mechanisms for reproducing urban and rural prestige in León helps explain the capacity of later branches of the lineage—such as the one established in Santiago del Molinillo—to sustain and legitimize their status as acknowledged hidalgos. The Villafañe trajectory thus reveals a continuity in the articulation of urban status, patrimonial networks, and mobility into new spheres of influence, both within the Leonese rural hinterland and across to the Indies.

The principal support for this hypothesis is Doña Elena de Villafañe, probably born between 1520 and 1530, who was likely a descendant of the urban branch of the Villafañe based on the Rúa of León (Sánchez Badiola 2019). Doña Elena entered into a second marriage with Don Ares García, a hidalgo resident in Santiago del Molinillo, widower of Doña Beatriz de Lorenzana [Quiñones]1, who likewise belonged to the Leonese patriciate.

In several lawsuits concerning the Luna mayorazgo (entailed estate)—particularly those litigated between 1577 and 1612 (AHN 1577; ARChV 1577, 1580b, 1582, 1596, 1612)—Doña Elena de Villafañe, a resident of Santiago del Molinillo, appears acting both in her own right and as mother and guardian of her son, Lázaro de Villafañe. Elena is identified as the wife of Ares García, who had died by that time, although he is still documented as living on 30 August 1554. In the creditors’ proceeding over the mortgaged assets of the entail, Elena and her son Lázaro held a prominent position, since Ares García had been a creditor or beneficiary of obligations linked to that mayorazgo—rights that his son inherited under maternal guardianship around 1571.

The family’s establishment in Santiago del Molinillo places them squarely within the Leonese landscape shaped by patrimonial claims, reinforcing the hypothesis that the Villafañe lineage was embedded in the region’s rural networks of interest. The active participation of Elena and Lázaro in these suits reflects not only the defense of specific economic rights but also the preservation of an inherited social standing, confirming the continuity of the lineage as a legitimate extension of León’s patrician house.

A key element reinforcing this hypothesis is the suit concluded by a final, enforceable judgment in 15292 between Buenaventura de Lorenzana and Martín de Villafañe3 concerning the partition of the estate of Alonso de Lorenzana and Beatriz de Quiñones. The assets in dispute included:

- Two houses in the city of León4, one on Frenería Street, near the sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Camino, and another on the Rúa Cabolas, in the sector known as the “casas del rey.”

- Meadows at Puente del Castro, awarded to Martín de Villafañe, to Buenaventura de Lorenzana, and to the heirs of Gonzalo and Rodrigo de Lorenzana.

- Hereditary rights over properties located in Villa Belderro, Villa Rosace, and Valencia de Don Juan.

This litigation reveals not only the existence of a shared patrimony—including urban houses and rural properties—but also the intertwining of the lineages through kinship ties. Rodrigo de Villafañe appears as guardian of the Lorenzana minors, while Gómez de Villafañe “the Elder” acted as estate divider, being referred to as “uncle” of the heirs—an indication of close consanguinity (ARChV 1529).

Additionally, other suits related to the estate of Doña Beatriz de Lorenzana y Quiñones—first wife of Ares García—reinforce this connection. Proceedings conducted between 1571 and 1578 (ARChV 1576, p. 44; 1577; 1580a), concluded by final judgments issued by the Royal Chancery of Valladolid, document disputes over properties located in León, San Román, Llamas, and Santiago del Molinillo. These assets, grounded in a pious endowment established by Beatriz, were claimed by her niece Beatriz de Quiñones Lorenzana and her husband, Licentiate Diego de Vaca, while Elena de Villafañe defended the interests of her son Lázaro—thereby consolidating the link between the urban and rural branches of the lineage (ARChV 1576, p. 44; 1577; 1580a).

It is also worth noting another Elena de Villafañe5, second wife of Pedro Gómez de Sevilla, who in 1495 litigated over properties situated on the Rúa de los Francos, including a fortified tower (ARChV 1495; Quesada 1989; Vasallo Toranzo 2003). A deed of gift executed by this same Elena, already widowed, in favor of her niece María de Villafañe, daughter of Cristóbal de Villafañe, concerning a holding in Villagodio (Zamora), is also preserved (AHN 1514). Taken together, these records suggest the continuity of the lineage’s patrimony and onomastics in León since the late fifteenth century6.

In this context, it is plausible that Doña Elena de Villafañe descended from the branch consolidated in León, probably connected to Gómez de Villafañe “the Elder”. Although a documentary-proof filiation cannot be established, several hypotheses are reasonable:

- That she was the daughter or niece of Rodrigo de Villafañe, guardian of the Lorenzana minors (ARChV 1529).

- That she was the granddaughter or great-granddaughter of Gómez de Villafañe “the Elder” (ARChV 1529).

- Or that she descended from Cristóbal de Villafañe7, brother of the aforementioned Elena, who litigated in 1495 (AHN 1514; ARChV 1495).

The settlement of this branch in Santiago del Molinillo—held as a lordship by the García de Villafañe since the sixteenth century—and the marriage of Lázaro de Villafañe to doña María de Gavinales y Quiñones (or Benavides y Gavilanes or Gavinales y Guzmán)8, a kinswoman of Luis Quiñones Osorio, strengthen the hypothesis of a strategic insertion aimed at consolidating patrimony and status. Lázaro’s transatlantic reach—he accompanied Governor Quiñones Osorio to Tucumán in 1610 and was appointed deputy governor (teniente de gobernador) of Nueva Rioja in 1611—illustrates this noble mobility strategy (Villafañe 2022, 2025).

The adoption of the compound surname “García de Villafañe” expresses a deliberate intention to perpetuate the memory of the urban lineage and to preserve maternal social legitimacy within a peripheral rural setting. Taken together, the assembled evidence supports the view that the Villafañe of Santiago del Molinillo constitute an active and legitimate offshoot of the Leonese patriciate, adapted to new arenas without relinquishing their symbolic standing (Serrano Redonnet 1967).

3.2. Hypotheses on the Formation of the Lineage in Santiago del Molinillo

Ares García: Possible Origin in the Local Hidalguía Linked to Ordás

A plausible hypothesis regarding the formation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo suggests that Ares García, direct forebear of the García de Villafañe, came from the local hidalguía established around the headwaters of the Órbigo River, tied to the house and tower of Ordás. This hypothesis rests on statements presented in 1618 by Ramiro de Villafañe y Guzmán in Santiago del Molinillo, which indicate a common descent among several García families settled in the region (Serrano Redonnet 1944).

The house of Ordás, based in Santa María de Ordás and its environs, is documented from the fifteenth century as an hidalgo ancestral seat of notable regional influence. Notable members include Gonzalo García de Ordás of Borga (lawsuit, 1520) (ARChV 1520), Francisco García de Callejo (lawsuit in 1514) (ARChV 1514), and Jerónimo García de Ordás, deputy magistrate (teniente de corregidor) in 1739 (AHN 1727). Likewise, Captain Juan García de Ordás, a native of Rioseco de Tapia and participant in pacification campaigns in New Granada around 1588 (ARChV 1626a, 1626b), illustrates the overseas projection of this rural nobility.

Documentation reveals a kinship network among the García, Ordás, Gavilanes, and Quiñones lineages, sustained through marriage alliances designed to consolidate patrimony and prestige. Among these, Pedro García Gavilanes y Quiñones (ARChV 1614, 1794) appears as a close relative of Luis García de Villafañe y Barba de Guzmán, descendant of Lázaro de Villafañe and María de Gavilanes Guzmán—herself a descendant of Ares García and Elena de Villafañe (Sánchez Badiola 2019).

On 30 August 1554, Ares García appears as a creditor for a substantial sum in the context of the Luna mayorazgo, confirming his active insertion into economic networks of considerable scope. His son, Lázaro de Villafañe, together with his mother Elena de Villafañe, subsequently pursued legal actions to defend the family estate into the early seventeenth century (AHN 1577; ARChV 1612).

The 1608 census describes Lázaro de Villafañe as an “hidalgo notorio de solar conocido” in Santiago del Molinillo. This status—confirmed through chancery judgments and parish patronage rights—secured the lineage’s noble legitimacy. A royal service declaration further defines him as:

“knight and nobleman (caballero hijodalgo)… and lord of the village called Santiago del Molinillo, on the banks of the Órbigo River, in the Kingdom of León”.(AGI 1619)

Additional evidence from a pleito de hidalguía highlights the family’s ecclesiastical prestige and burial privileges, indicating long-standing recognition within the community. As one witness testified:

“…the main chapel of the church in the said village of Santiago belongs to the Garcías de Villafañe, and never, in his time, had the witness seen or heard of any person being buried there who was not of that lineage and surname…”.(ARChV 1677)

In this context, the expression “señor del pueblo” refers not to a jurisdictional lordship (señorío jurisdiccional), but rather to his position as principal landholder and head of the ancestral house (casa solar), exercising patrimonial and symbolic authority within the locality. No evidence indicates that Santiago del Molinillo functioned as a legally constituted señorío de vasallos. Instead, his status aligns with that of a rural hereditary noble (hidalgo de sangre) holding property, patronage rights, and local precedence.

The adoption of the compound surname “García de Villafañe” following the marriage of Ares García to Elena de Villafañe reflects a deliberate strategy of symbolic continuity, combining urban and rural noble capital within a locally adapted family structure. Lázaro’s subsequent career—travelling to Tucumán with Luis Quiñones Osorio in 1610 and serving as deputy governor of Nueva Rioja in 1611—demonstrates the family’s ascent and transatlantic projection.

Regarding kin networks, María de Gavinales y Quiñones, Lázaro’s wife, reinforced the family’s integration into leading hidalgo houses of the region through her paternal line, as daughter of Lope Rodríguez de Gavilanes and granddaughter of Hernando de la Vecilla, while her great-grandmother, Doña Leonor de Quiñones, held the title of señora de Alcedo. This ancestry not only consolidated ties with the Gavilanes and Vecilla families but also traced back to the Casa de Alcedo of the Quiñones, a branch descending from the renowned Paso Honroso lineage and the Counts of Luna. The presence of the Benavides surname in her lineage further suggests collateral links with the noble house of Santisteban del Puerto. Documentary testimony provides additional weight: according to the statements of Ana María de Pimentel (a nun) and María Magdalena de Pimentel (Marchioness of Viana), daughters of the 7th Count of Benavente, María de Gavinales y Quiñones was acknowledged as belonging to the Luna comital family, thereby confirming the Villafañe lineage’s insertion into wider noble networks (ARChV 1677).

The 1761 census rolls for the township of Ordás record the continued presence of numerous García hidalgos—acknowledged as hidalgos of a known ancestral seat—including, notably, Juan Manuel García, Jerónimo García de Ordás, and several clerics and litigants in pleitos de hidalguía.

The heraldry associated with these lineages comprises an eighteenth-century shield—per pale with a demi-chief—whose variants display fleurs-de-lis, a bordure of saltires, a chequy field, and a bordure charged with lions and castles. Taken together, these devices point to Ordás, Quiñones, and possibly García or Quijada.

Finally, the 1625 census of Santiago del Molinillo formally confirms that Don Antonio de Villafañe Gavilanes, Don Isidro de Gavilanes, and Don Manuel de Villafañe—sons of Lázaro de Villafañe and María de Gavilanes Guzmán—were “all four are hidalgos of a recognized ancestral house from the García and Ordás lineages”9, thereby consolidating the nobiliary legitimacy of their descendants. This official declaration corroborates the lineage’s successful integration into local power networks and reinforces the hypothesis of a hidalgo de solar conocido formation rooted in the house of Ordás and projected into new spheres of influence in both León and the Americas (ARChV 1677).

In this context, it is reasonable to consider that Ares García may have descended from the local hidalguía linked to the house of Ordás. Although a documentary-proof filiation cannot be established, several hypotheses are plausible:

- He was a direct member of the Santa María de Ordás house, as a hidalgo descending from Gonzalo García or Francisco García de Ordás.

- He stemmed from a marital alliance between the García and Ordás houses, perhaps through a branch established in Rioseco de Tapia or Callejo.

4. Discussion

This article is explicitly hypothesis-formulating: it interprets convergent documentary signals to propose plausible mechanisms for the origin and consolidation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo, rather than to close filiations with definitive proof. Read in this key, the case illuminates how an urban patrician identity centered on León’s Rúa could be recomposed as rural authority in the Montaña de León through deliberate household strategies, marital brokerage, and institutional anchoring in concejo and parish arenas (cf. Fernández 2002; Sánchez-Bordona et al. 2003; Menéndez Pidal 1962; Sánchez Badiola 2019).

4.1. Mechanisms of Lineage Consolidation

Onomastics operated as a technology of memory and legitimacy. The adoption and sustained use of the compound surname “García de Villafañe” signaled provenance and sutured maternal and paternal claims across jurisdictions, consistent with Iberian strategies whereby illustrious urban surnames bolstered authority in rural settings absent formal mayorazgo or under partial entail (Sánchez Badiola 2019). Kinship networks functioned as infrastructure, translating reputational capital into durable access to offices, parish preeminences, and credit circuits. Local institutions were arenas of socio-legal performance in which privileges, chaplaincies, and officeholding formalized precedence and archived it, stabilizing status intergenerationally (Fernández 2002; Sánchez-Bordona et al. 2003).

4.2. Evidentiary Gradient: From Robust to Tentative

Because the argument builds hypotheses from fragmentary series, it is useful to distinguish claims by confidence level:

- More robust (multi-source convergence): continuous local presence of the surname; institutional footprints in municipal and parish spheres; involvement in litigation and credit networks; recognition as hidalgo notorio de solar conocido; deliberate, persistent compound onomastics; and documented transatlantic projection maintaining linkage to the Leonese solar (Villafañe 2022, 2025).

- More tentative (working hypotheses pending linkage): the precise placement of Doña Elena de Villafañe within the urban branch on the Rúa, and the exact pathway by which Ares García relates to the Ordás milieu (direct descent versus alliance line). These remain open to refinement through targeted record linkage.

This gradient clarifies that the discussion advances a structured interpretive model rather than asserting closed genealogical trees.

4.3. Gendered Mediation and Archival Asymmetries

Doña Elena de Villafañe is central not by biographical exceptionality but because her documented managerial and litigating roles make visible channels—inheritances, pious endowments, guardianships—through which property and identity circulated when agnatic lines dominate surviving narratives (ARChV 1529; AHN 1514). Recognizing these gendered asymmetries is methodologically consequential: it cautions against over-reliance on male-line proofs and underscores women’s agency in sustaining patrimony and memory under conditions of partial documentation.

4.4. Methodological Implications

The contribution is as much methodological as substantive. Cross-reading heterogeneous series—population rolls, parish books, hidalguía suits, and notarial protocols—supports inference by triangulation (spatial co-localization, persistence of names, institutional footprints, and recurrent association with specific kin networks). This microhistorical stance privileges density and mechanism over completeness, aligning with work on hidalguía that emphasizes practice (what households did) over formal rank (what titles they held), while remaining explicit about limits imposed by pre-eighteenth-century gaps, underdocumentation of female kin, and strategic surname variability.

4.5. Comparative and Historiographical Significance

The case refines how urban prestige could be transferred and stabilized in peripheral rural settings without rupture, and how such recomposed authority subsequently traveled across the Atlantic. It invites comparative testing among other Leonese houses exhibiting similar urban-to-rural transfers followed by overseas projection, contributing to a broader historiography of social reproduction outside major titled elites.

4.6. Genetics and Interdisciplinary Perspectives

Although this research is based primarily on documentary, heraldic, and archival evidence, the potential contribution of genetics to historical genealogy deserves consideration. Advances in molecular genealogy offer new possibilities for testing hypotheses of biological continuity that complement written records. In this context, the Villafañe surname—of likely Germanic or northern European origin, rather than strictly peninsular—shows remarkable consistency across centuries. Preliminary genetic data from contemporary South American descendants of the lineage have identified HFE gene variants (C282Y and H63D) associated with hereditary hemochromatosis, a condition historically prevalent among northern European populations (Feder et al. 1996). While no ancient-DNA evidence is yet available, these findings suggest ancestral roots consistent with the onomastic and historical record. Future interdisciplinary research integrating genetic, documentary, and geographical evidence could refine our understanding of lineage continuity, migration patterns, and adaptation across the Atlantic world.

In this sense, the Villafañe lineage constitutes a valuable case for understanding the articulation between rural social reproduction and the broader processes of mobility and adaptation within the Castilian and transatlantic nobility. Its study not only illuminates the strategies through which minor hidalguía families perpetuated their influence in changing historical contexts but also underscores the potential of interdisciplinary approaches—combining documentary, institutional, and genetic evidence—to redefine the scope of genealogical research in early modern studies.

5. Conclusions

This study advances a comprehensive interpretive model for the origin and consolidation of the Villafañe lineage in Santiago del Molinillo, situated at the intersection of the Leonese urban patriciate and the rural hidalguía menor. Through systematic triangulation of censuses, parish registers, hidalguía suits, and notarial protocols, the analysis demonstrates how household strategies, marriage alliances, and institutional anchoring in the concejo and parish sustained lineage status from the late medieval to the early modern period.

The evidence is most consistent with an urban origin on the Rúa of León channelled through Doña Elena de Villafañe, whose active role as litigant, guardian, and administrator of patrimony reveals the crucial function of women in preserving noble memory and property continuity. Her marriage to Ares García, a hidalgo linked to the Ordás milieu, fused urban and rural assets, generating the compound surname “García de Villafañe” as both an onomastic marker of provenance and a symbolic mechanism of social distinction. These strategies were consolidated through kin alliances with the Quiñones, Gavilanes, and Rebolledo families, participation in municipal and ecclesiastical offices, and the persistent use of the surname as a vehicle of identity transmission.

The trajectory of Lázaro de Villafañe illustrates how lineage prestige could expand across the Atlantic while maintaining continuity with the Leonese solar. His mobility toward colonial La Rioja and Cordova demonstrates the transfer and adaptation of Castilian social and institutional models to new colonial hierarchies. The Villafañe lineage thus exemplifies how rural nobility operated as a bridge between local and imperial frameworks, projecting its legitimacy beyond Iberia and contributing to the formation of new American elites.

From a historiographical standpoint, this study contributes to the understanding of early modern social reproduction by integrating the perspectives of social and gender history. It shows how compound surnames, kinship networks, and municipal service operated as durable mechanisms of lineage perpetuation even in the absence of major titles or formal entails. The expanded discussion of gendered mediation highlights women’s agency within family economies, while the inclusion of a genetic perspective—suggesting northern European origins supported by HFE gene variants (C282Y, H63D)—opens promising interdisciplinary avenues for future research linking molecular evidence with historical genealogy.

Ultimately, the Villafañe lineage provides a model case for exploring the dynamics of identity, mobility, and adaptation in early modern Castile and its transatlantic extensions. The integration of documentary, institutional, and genetic evidence underscores the potential of genealogical microhistory to connect local family histories with the broader processes of social and imperial transformation that shaped the early modern world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Beatríz de Lorenzana was the daughter of Rodrigo de Lorenzana and the granddaughter of Alonso de Lorenzana and Beatriz de Quiñones. |

| 2 | Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid, Ejecutoria del pleito litigado por Buenaventura de Lorenzana contra Martín de Villafañe, residents of León, concerning a claim of boasting (jactancia) over the possession of certain properties, Registro de Ejecutorias, Caja 416, no. 14, 5 June 1529. |

| 3 | Martín de Villafañe was the son of María de Lorenzana and Hernand Álvarez, and the grandson of Alonso de Lorenzana and Beatriz de Quiñones, as recorded in the ejecutoria of the lawsuit with Buenaventura de Lorenzana (ARChV 1529, Caja 416, nº 14). |

| 4 | Frenería Street was a commercial thoroughfare where artisans specialized in the manufacture of bits and iron fittings were concentrated. It was located near the sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Camino, in an area frequently traversed by pilgrims. The “Casa del Rey” or “Casas del Rey” referred to a set of buildings linked either to royal administration or to properties of the León municipal council. Its location near the market indicates that the second house stood in a central sector of high symbolic and economic value in sixteenth-century León. |

| 5 | In 1495, Doña Elena de Villafañe, the second wife of Pedro Gómez de Sevilla, appears in a lawsuit concerning properties located on the Rúa de los Francos, among them a fortified tower built by her husband before 1470. This litigation, documented in the Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (AChVa, Reales Ejecutorias, C. 80-4), highlights not only the patrimonial importance of the Gómez de Sevilla family but also Doña Elena’s insertion into a milieu of significant social and economic standing. |

| 6 | The 1495 lawsuit, recorded in the protocols of the Real Chancillería de Valladolid, attests to the possession of strategically located urban assets and to the active defense of family property by the Villafañe lineage. The subsequent transmission of these holdings to her son, Lázaro Gómez de Sevilla, underscores both patrimonial continuity and onomastic strategy, as the name Lázaro reappears in the descendants of another Elena de Villafañe—Elena de Villafañe y Flórez—consolidating a mechanism of preserving family memory through both property and naming practices. |

| 7 | Cristóbal de Villafañe is documented as the father of María de Villafañe and as the brother of an Elena de Villafañe, who married Pedro Gómez de Sevilla. This double family connection reveals that Cristóbal belonged to a collateral branch of the Villafañe lineage, integrated into León’s urban elite through marital strategies. |

| 8 | Archivo Diocesano de León, 1580, Marriages 1, Santa Marina, fol. 47. |

| 9 | (Cross). Likewise, they further declared that Don Antonio de Villafañe Gavilanes, son of the late Lázaro García de Villafañe and Doña María de Gavilanes Guzmán, his deceased parents, who serves as corregidor of the town of Laguna de Negrillos and its jurisdiction on behalf of His Excellency the Count of Benavente and Luna, and Don Isidro de Gavilanes, cleric, absent, all three, and Don Manuel de Villafañe, their brother, likewise absent, are all four nobles of a recognized ancestral estate of the Garcías and Ordases, and thus they unanimously declared (AChVa, Sala de Hijosdalgo, C. 570-6). |

References

- AGI. 1619. CHARCAS, 101, N.18. Sevilla: Archivo General de Indias (Charcas). [Google Scholar]

- AHN. 1514. LUQUE, C.410, D.48. Toledo: Archivo Histórico de la Nobleza (LUQUE). [Google Scholar]

- AHN. 1577. OSUNA, C.3364, D.19. Toledo: Archivo Histórico de la Nobleza (OSUNA). [Google Scholar]

- AHN. 1727. OSUNA, C.3321, D.5. Toledo: Archivo Histórico de la Nobleza (OSUNA). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1495. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 80,4. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1514. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 292,12. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1520. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 343,22. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1529. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 416,14. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1546. PL CIVILES, VARELA (O), C. 1051-1. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (PL CIVILES). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1576. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1341,44. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1577. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1345,1. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1580a. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1416,51. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1580b. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1422,14. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1582. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1463,40. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1596. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 1754,6. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1612. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 2119,63. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1614. PROTOCOLOS Y PADRONES, CAJA 37,1. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (PROTOCOLOS Y PADRONES). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1626a. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 2446,2. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1626b. REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS, CAJA 2449,53. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (REGISTRO DE EJECUTORIAS). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1677. SALA DE HIJOSDALGO, CAJA 570,6. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (SALA DE HIJOSDALGO). [Google Scholar]

- ARChV. 1794. PROTOCOLOS Y PADRONES, CAJA 154,3. Valladolid: Archivo de la Real Chancillería de Valladolid (PROTOCOLOS Y PADRONES). [Google Scholar]

- Boixadós, Roxana. 2003. Parentesco e Identidad en las Familias de la Élite Riojana Colonial (Siglos XVII y Comienzos del XVIII). Master’s thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Boixadós, Roxana. 2004. Asuntos de familia, cuestiones de poder: La” concordia” en el cabildo de La Rioja, gobernación del Tucumán, 1708. Colonial Latin American Historical Review 13: 147. [Google Scholar]

- Boixadós, Roxana. 2011. El fin de las Guerras Calchaquíes. La Desnaturalización de la Nación Yocavil a La Rioja (1667) [The end of Calchaquíes wars. The deportation of the Yocavil nation to La Rioja]. Corpus. Archivos Virtuales de la Alteridad Americana 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farberman, Judith, and Roxana Boixadós. 2006. Sociedades indígenas y encomienda en el Tucumán colonial. Un análisis comparado de la visita de Luján de Vargas. Revista de Indias 66: 601–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, John N., Andreas Gnirke, William Thomas, Zenta Tsuchihashi, David A. Ruddy, Anil Basava, Farzam Dormishian, Roberto Domingo, Jr., Melvin C. Ellis, Alan Fullan, and et al. 1996. A novel MHC class I–like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nature Genetics 13: 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, Ana Isabel Arias. 2002. Tradiciones y Celebraciones en León: 1600–700. León: Universidad de León, Secretariado de Publicaciones, vol. 1, pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Pidal, Luis. 1962. Conjunto histórico artístico de la ciudad de León. Academia: Boletín de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando 14: 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Moxó, Salvador, and Ortiz de Villajos. 1968. La nobleza castellano-leonesa en la Edad Media. Problemática que suscita su estudio en el marco de la historia social. Hispania: Revista Española de Historia 30: 5–114. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano Aliaga, Alejandro. 2003. Don Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera 1528–1574. Origen y Descendencia. Córdoba: Alción. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, María Laura, and Silvia Palomeque. 2008. Ciudad Colonial y Economía: Córdoba, 1573 a 1620. Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, Manuel Fernando Ladero. 1989. La remodelación en el espacio urbano de Zamora en las postrimerías de la Edad Media (1480–1520). Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie III, Historia Medieval 2: 161–88. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga, Laura. 2012. Las granjerías de la tierra: Actores y escenarios del conflicto colonial en el valle de Londres (gobernación del Tucumán, 1607–1611). Surandino Monográfico 2: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Badiola, Juan José. 2019. Nobiliario de la Montaña Leonesa. Granada: Torres Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bordona, María Dolores Campos, and Javier Pérez Gil. 2003. De recinto regio a fábrica textil. Las transformaciones de los Palacios Reales de León en el siglo XVIII. De Arte: Revista de Historia Del Arte 2: 165–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Redonnet, Jorge A. 1944. Introducción al Estudio de la Casa de Villafañe y Guzmán. Genealogía, Revista Del Instituto Argentino de Ciencias Genealógicas 2: 103–70. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Redonnet, Jorge A. 1967. Poético elogio de los linajes leoneses y «generaciones» de la casa de la Vecilla. Hidalguía 84: 605–40. [Google Scholar]

- Toranzo, Luis Vasallo. 2018. La capilla de Francisca de Villafañe, un ejemplo de patronato artístico a mediados del siglo XVI en Valladolid. Boletín. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de La Purísima Concepción 53: 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vasallo Toranzo, Luis. 2003. Juan de Álava y Pedro de Ibarra al servicio de los condes de Alba y Aliste. Boletín Del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: Buenos Aires 69–70: 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- Villafañe, Jorge Hugo. 2022. Movilidad social e hidalguía en Castilla y América (1580–1937): In saecula saeculorum. Historia 396 12: 249–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafañe, Jorge Hugo. 2023. Family Dynamics in Colonial La Rioja: A Case Analysis of Five Generations. Genealogy 7: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafañe, Jorge Hugo. 2024. The Social Mobility and “Hidalguía” of the Villafañe y Guzmán Family Reflect the Intricacies of Social and Colonial Dynamics over Five Centuries. Histories 4: 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafañe, Jorge Hugo. 2025. Dynasties, legacies, and strategies of heritage preservation: Elite patrimonial practices in colonial La Rioja (17th–early 18th century). Histories 5: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).