Abstract

In this paper, we describe the developmental process of a culturally grounded Moombaki virtual reality (VR) game. We share how Aboriginal children’s drawings have informed the creation of an interactive learning platform for primary school-aged children attending schools in Wadjuk Boodja. The project focused on connecting students to cultural knowledge through immersive storytelling, creative exploration, and collaborative design by using small group yarning circles and game development activities. The aim of the yarning sessions was to identify, explore, and understand the knowledge Aboriginal children had of Aboriginal identity and culture, including protocols, ceremonies, stories, Dreamtime, languages, and traditional practices, and how best to represent these concepts in the cultural learning journey using virtual reality.

- Noongar karnarn has its own traditional customs employed with contemporary current practice. This is because the Noongar karnarn is undergoing a significant revival from its traditional roots in oral practice to a written karnarn. In terms of Noongar words appearing in this paper, the rules for capitalisation are still evolving. These rules vary depending on context, speaker, and the purpose of the writing. To honour Noongar people and karnarn we will be capitalising terms that are of significant cultural or spiritual importance as this is the respectful and consistent practice (Australian Government, Wheatbelt Natural Resources Management, Northam 2013).

- Noongar can be spelled in several customs, and we are using this convention to refer to the group of Aboriginal traditional peoples whose 14 groups occupy the southwest of Western Australia, including Boorloo (Perth).

- Moort is part of the Noongar karnarn and refers to family and kin.

- Boodja is part of the Noongar karnarn and refers to land or traditional ‘country’.

- Karnarn is part of the Noongar karnarn and refers to speaking truly and is used in this paper to refer to traditional karnarn.

1. Introduction

ngan kaditj-djinang koora-koora, yey, kidji mila boola norerl, ngalak nyin yey moorditj kadjan wadjuk Boodja jinang-iny.Ngala mia koorda Boodja moort koondarmWe pay respect to all the past, present and future Elders. We acknowledge their power, passion and good spirit that allow us to be on Wadjuk Boodja.Our place is in country, moort, kin & culture.(Kickett-Tucker and Winmar 2016)

Kany (First)

Imagine stepping into the shoes of a koorlangka (young Noongar child), eager to learn about their rich cultural heritage. They are surrounded by modern technology, but their connection to their ancestral traditions feels distant, untouched, and unexplored. Moombaki means “where the rivers meet the horizon”, and participation in the Moombaki Noongar Cultural Digital Quest “power ups and challenges” gamers. Through this innovative platform, the koorlangka embarks on a journey unlike any other. They are transported to the ancient lands of the Noongar people, where spirits whisper tales of resilience and wisdom.

As they navigate through immersive virtual reality landscapes, they encounter Elders who share stories passed down through generations. They learn the rhythm of traditional dances, hear the melodic heart of Noongar language, and witness the intricate artistry of Dreamtime legends.

With each interactive experience, the young learner not only absorbs knowledge but also feels a deep sense of pride and belonging. They realise that their cultural identity is not just a relic of the past, but a vibrant tapestry woven into the fabric of their present and future.

Through Moombaki, we empower future generations to reclaim their heritage, fostering a renewed sense of connection and respect for Noongar culture. This is not just about solving a problem—it is about revitalising a legacy, ensuring that the flame of Noongar heritage continues to burn bright for generations to come.

Moombaki cultural learnings is a research project that aims to strengthen Aboriginal children’s wellbeing and educational outcomes by connecting urban children to identity, culture, country, and kin. The importance of this objective is supported by Fatima et al. (2022), who found in their study of Indigenous Australian children that a strong cultural identity and knowledge are protective factors for social and emotional wellbeing. Other studies have found that Aboriginal children’s connection to their country and culture enables pride in their Aboriginal identity (Brown and Shay 2021; Shay et al. 2023).

There is a connection between culture, health, and wellbeing, especially with relation to brain development and cognitive function. More specifically, neuroscience has shown that repetitive familiar experiences and learning of language and culture at an early age are catalysts for peak brain and thinking skill development (Perry 2009; Gee 2016). In addition, Kickett-Tucker (2021) reported that environments that are culturally safe and responsive have a positive impact on an individual’s sense of identity and belonging. A positive cultural environment helps a person develop resilience, which, according to Dudgeon et al. (2014), is impactful to wellbeing. Furthermore, emotional regulation, social connection, and a strong sense of self are strengthened with consistent and appropriate cultural and language experiences (Perry 2009).

The importance of language cannot be underestimated as a proactive factor of wellbeing, as found in studies of 6350 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults by Dinku et al. (2025) and 9149 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by Wilkes et al. (2024). In fact, Wilkes et al. (2024) state that participation in a language program is “associated with higher prevalence of good to excellent general health, high happiness, high life satisfaction, and never feeling disconnected from culture” (p. 3).

We recognise that Noongar children may speak Aboriginal English at home, and yet, from our interactions in the Moombaki study, they are eager to learn traditional dialects of the Noongar language. Biddle and Swee (2012) and Cummins (2000) report that learning traditional language (via songs, yarning, storytelling, dance and art forms) strengthens the cultural heartbeat that motivates a sense of belonging, critical thinking, and the skills needed for the transition and transfer of learning and literacy. When children’s language and culture are front and centre in their learning environments, the message to them is: you matter here—in this classroom; in this school. A consistent positive reinforcement such as this is a foundational motivation to positive identity and educational engagement.

The Moombaki “where the rivers meet the horizon” project aims to honour the revitalisation of the traditional dialects of Noongar language and place it in our holistic learning framework to not only use it as a tool to communicate with one another but also as resource to be held and kept by children who are the knowledge keepers for the future legacies yet to be born.

For stage 3 of the Moombaki research project, the research team developed, implemented, and evaluated the impact of a suite of novel cultural learning programs and school cultural safety plans that aim to strengthen Aboriginal primary school students’ wellbeing (Study 3). In this paper, we present the yarning circles where Noongar primary school children illustrated and described culture for inclusion into the design and development of Moombaki Noongar Quest—a virtual reality game of culture.

Moombaki is a multimodal learning platform comprising of weekly curriculum, resources, mobile games (using an iPad), and a VR game. The use of technology is innovative in engaging an interactive experience that provides an additional learning platform for Aboriginal school children to explore cultural knowledge and language. This is particularly pertinent in Australia today as the Commonwealth Government’s Close the Gap (CTG) initiatives are failing our Aboriginal children. Aboriginal children continue to suffer the consequences of attending culturally unsafe schools, resulting in high rates of disengagement (Productivity Commission 2024; Thackrah et al. 2021). The systemic and institutional barriers are compounded by the denial of Aboriginal children’s rights to identity and cultural freedom, thus having a major impact on their sense of self and wellbeing (Australian Human Rights Commission 2020; Kickett-Tucker and Shahid 2019).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Koorlangka Mart (Group of Children)

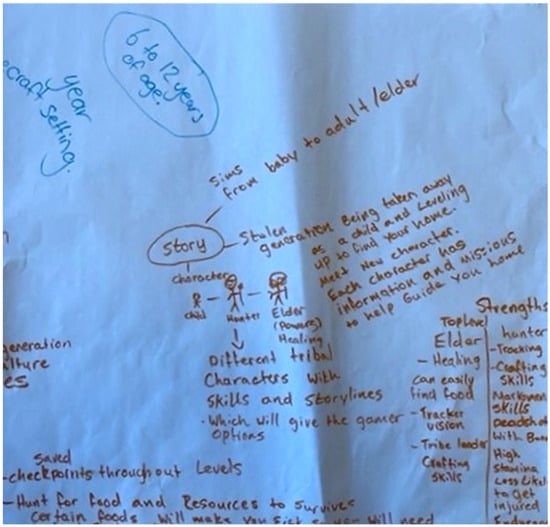

Forty Aboriginal koorlangka children (mostly Noongar), aged 9–12, from three primary schools in Boorlo (Perth), Western Australia, shared their ideas (via illustrations and text) about culture and language for inclusion in the Moombaki Noongar Quest VR game design. Fourteen (14) yarning groups were organised, which were comprised of 4–6 koorlangka, 1–2 Aboriginal carers, and one undergraduate university gaming and animation student per group. The combined session was conducted over a day, koorlangka ideas were transformed into drawings on butcher’s paper using coloured markers. The children’s drawings often serve as a direct representation of their imagination, cultural knowledge, and lived experiences (Farokhi and Hashemi 2011). Drawing also enables children to make meaning of the world they live in and can also contribute to critical thinking skills (Brooks 2009).

Aboriginal parents and carers joined the creative yarning circles and offered cultural guidance to koorlangka. These circles are spaces for respectful sharing, listening, and co-creation. By using this method, the development team ensures that the game is not only a reflection of traditional culture but also a novel vehicle for empowering young people to engage with their ancestral ties to land and community. Gaming and Animation University students provided a game design structure to the conversations. The aim was to explore, present, discuss, and decide on koorlangka-focused ideas of items of culture and language that were important and vital to creative cultural learning using virtual reality (VR) technology.

2.2. Warniny (Process of Doing)

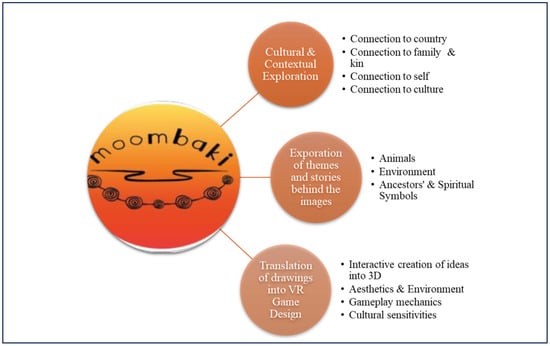

The lead researcher, a local Boorloo Wadjuk (Noongar) traditional owner, used the following framework to interpret koorlangka drawings of culture and language for VR game inclusion (see Figure 1). The lead researcher’s knowledge has influenced the lens and subsequent analysis of children’s illustrations of their connection to Noongar culture. Her knowledge is gained from various sources, including individual experiences and, importantly, the teachings from parents and Elders. She is also guided by her consistent active living of Noongar cultural protocols. These have shaped her lens of the interconnectedness of all things from the past, present, and future. Also, the framing of the lead researcher’s lens and analysis is rooted in the concept of social-emotional wellbeing and how these functions within Aboriginal cultures (Commonwealth of Australia 2017).

Figure 1.

Framework for the interpretation of Noongar culture and language for VR game development.

“Wellbeing” in the Noongar world is deeply rooted through intricate connections to boodja (land), moort, kin, culture, and self. It is a woven fabric of threads that comforts, strengthens, sustains, and nourishes the individual, moort, kin, and community. Through these connections are the relationships with self, land, and others that enable us to practice culture, which, in turn, creates the journey to a sense of belonging, purpose, and balance.

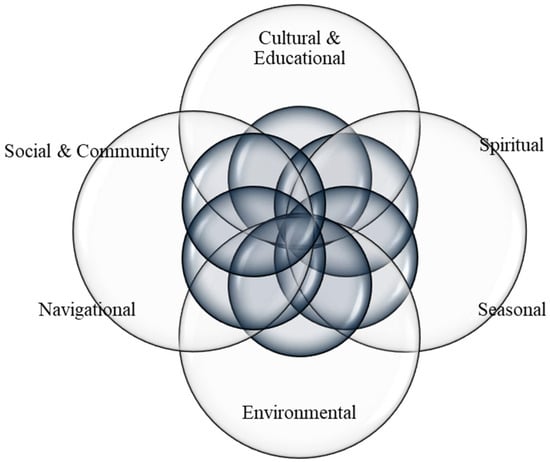

There is a rich and intricate Noongar worldview, and the lens we use will reveal the complexities of the relationship of self, country, culture, moort, and kin woven into koorlangka creations. There are tangible and intangible interconnected aspects which we can understand through the foundations of significance, including 1. cultural and educational, 2. spiritual, 3. environmental, and 4. social and community. These pillars of significance are relevant to both daily life and the wider ether and reflect a holistic understanding of a world where knowledge, identity, and place are deeply intertwined. What this means is that the Noongar worldview sees everything as relational and connected—what we know, who we are, and where we come from. A Noongar learning framework is rooted in the worldview which grounds culture, Country, community, and kinship in the learning experience and encourages relational, experiential, and deeply connected learning with identity and belonging (Kickett-Tucker 2021; Wright and Kickett-Tucker 2017). Using Figure 2 below, the pillars of significance offer a glimpse into koorlangka creations of the Noongar worldview and journey to thriving.

Figure 2.

Noongar worldview of elements of significance.

These interconnected lenses help us to “see” the unique koorlangka creations of their stories and the practices of the Aboriginal language and culture with the aim of integrating them into virtual reality game design and development. By approaching the world’s oldest living culture in this way, we aim to preserve, share Noongar culture to maintain authenticity, accessibility, and relevance for generations to come.

Moombaki is comprised of pillars of strength that help our understanding of Aboriginal identity and the deeply rooted connections to self, life, and living. These pillars are the (1) connection to Country, (2) connection to moort and kin, (3) connection to self, and (4) connection to culture. They act as a riverbed—our guiding metaphor to explain life’s ebbs and flows. Just like water in a river system that flows back and forth and produces energy when it reacts to the elements in the riverbed. The sustained journey of the kep (water) shapes and contours the riverbed. This is the same for the pillars of self, life, and living, which are contoured by the energy flowing in the spaces between. We will use this philosophy to explore koorlangka creations and, in doing so, observe and understand the interrelations between the pillars of self, life, and living. The expressions of self, life, and living, as depicted in the drawings, illuminate the separateness and the togetherness, which spotlights the spaces of the flow of energy, values, and beliefs, which all form the bedrock of wellbeing in Noongar society.

Drawing from the lead Chief Investigator’s Noongar Wadjuk’s lens (Kickett-Tucker 2025), we explored koorlangka creations, which revealed common threads of significance: 1. cultural and educational, 2. spiritual, 3. seasonal, 4. environmental, 5. navigational, and 6. social and community. See Figure 2 below.

The overlay of lenses is used to explore and understand koorlangka creations of Aboriginal culture and language for the purpose of VR game design and development. The Moombaki foundations included 1. connection to country, 2. connection to moort and kin, 3. connection to self, and 4. connection to culture, forming the core elements. We describe these elements as we explore the koorlangka illustrations.

3. Findings from Yarning Circles Koorlangka Katitjin (Children’s Knowledge)

3.1. Connection to Boodja

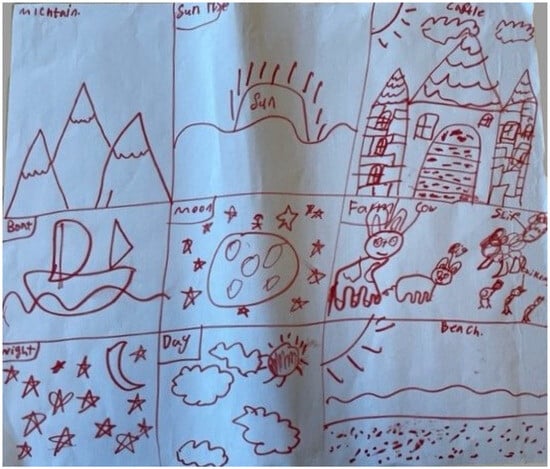

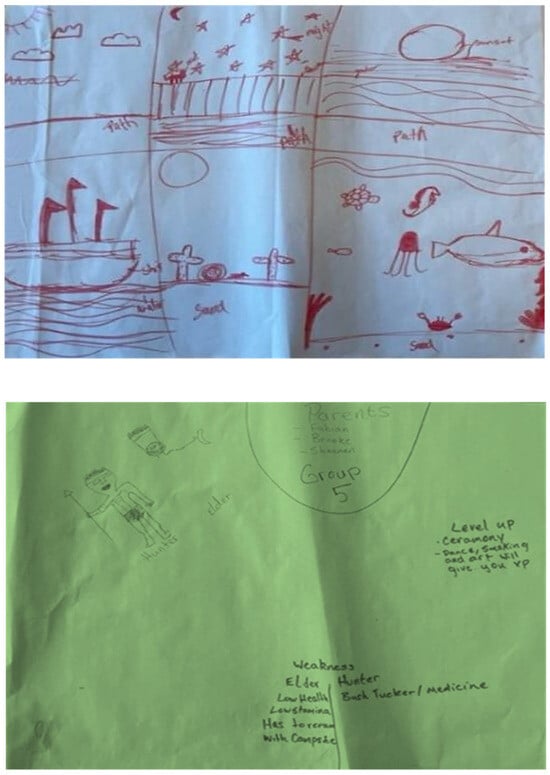

Yarning Circle 1 symbolises the connections to boojda (country). In this creation, koorlangka depicts their ideas of country, which is shown by geography (mountains), beach, sunrise, and daytime, with the sun and clouds, and the night sky with the moon and stars.

The ideas depicted in Figure 3 above show the cultural significance and importance of seasonal change. The koorlangka connection is visually seen in their environment and how these are connected to each other and to them. These elements have a significant and interconnected role in the lifecycle of the land and its people. For instance, the sun and moon are central elements to the Noongar worldview and connection to the land. They serve as catalysts of the natural world and are uniquely connected to Noongar’s six seasons, the timing of ceremonies, and daily life activities. The moon and sun help guide life, living, and cultural protocols in ways that strengthen the connections Noongar people have with themselves, the land, and beyond.

Figure 3.

Connection to country: Yarning Circle 1.

Sunrise and sunsets are indicators of a changing environment that is connected to the cycle of life, the land, and our spirit world. The sun rises to show a new day and thus is a symbolic gesture of the renewal of our koordoormitj (essence of spirit).

The moon and stars are celestial elements of grave importance to the Noongar peoples, which are uniquely tied to Boodja, beliefs, cultural continuity, time, and seasonal cycles. The moon helps to track time, such that it signifies the timing of ceremonial business. The moon is also vital in understanding the seasons and the proper timing for cultural practices such as hunting and fishing.

The Noongar peoples have a deeply interconnected relationship with the boodja (land), worl (sky), moort (family and kin), and katitjin (knowledge) of the cycles of life. These elements are not objects just to be seen by the eye but rather felt, understood, relied upon, respected, and honoured. It is the trilogy of Noongar theory (Collard et al. 2004) articulated by Professor Len Collard, who refers to the interconnected pillars of koorliny (moving forward), keny (becoming one), and kadadjiny (deep learning or knowing). This is a framework for how Noongar learn from, grow, and relate not only to one another but to the country. It is a continuous flow of energy that is relational and transitional for the individual’s transformation of their sense of self, belonging, and acceptance.

The stars are the heartbeat of our Ancestors and the eyes of our Elders, who map our physical and spiritual navigation in life. The night sky is our road map of stories past, present, and future. The Noongar cosmology was created during the Dreamtime, along with stories that guide the Noongar’s life compass (Kickett-Tucker 2025).

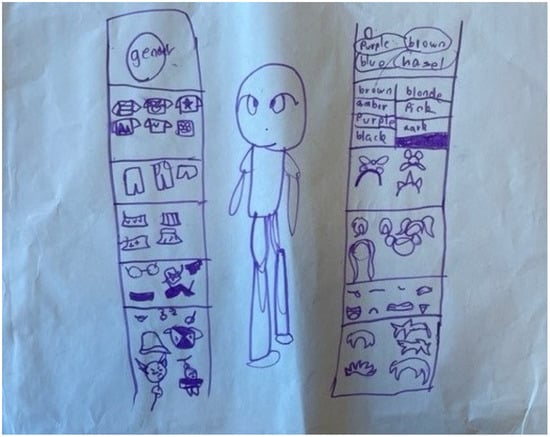

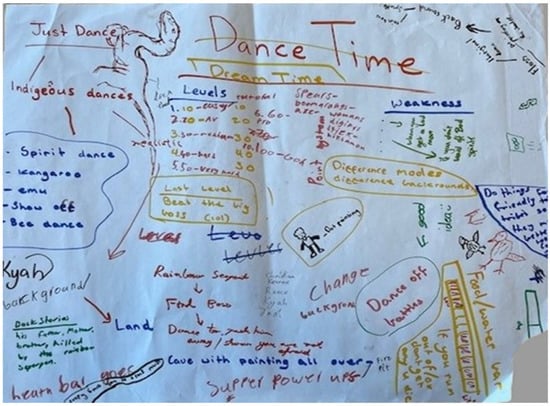

3.2. Connection to Self

Yarning Group 5’s creations in Figure 4 show the connection of self via internal personal attributes and the interconnection with external elements such as hair, clothes, colour, and accessories. The drawing weaves external decorative items with broader cultural values that are uniquely tied to the identity of the Aboriginal self. For instance, the drawing of the person in the middle of the illustration has well-defined eyes. In Noongar culture, the eyes are not merely for seeing realities but are also the receptors to the soul. The way in which a child sees the world and how she/he belongs is reflected in their gaze, be it curiosity, fear, acceptance, hope, or distrust.

Figure 4.

Connection to self: Yarning Circle 5.

Colour labels are written in the piece above, and this is a deeply symbolic nuance for a child’s understanding of their connection to the world, to the soul, spirit, identity, and to others. For example, the vibrant colour chosen for clothing and accessories reflects a personal connection to Noongar culture and what they consider valuable. For example, red, black, and gold symbolise identity with the Aboriginal flag. In doing so, the child makes the association of identity to Aboriginal people and the community in which they identify, are accepted, and belong.

In the illustration above, clothes can symbolise storytelling and knowledge transfer from Elders, thus the sharing of cultural practices. For instance, traditional clothing and traditional symbols show identification with specific communities, clans, and skin groups.

The accessories depicted may be from contemporary society, but their inclusion may show that they are important as part of traditional Noongar knowledge systems. For example, a child wearing a kangaroo pendant might be expressing a connection to a family totem, symbolising ties to kinship, spiritual identity, and responsibility to country. For example, the adornment of items represents a connection to ceremonial practices such as the rites of passage. In other cases, adornments may be connected to land or status in the community and spiritual connections (i.e., totem). These are external embellishments that serve to connect identity and place in the world in relation to self, moort, kin, country, community, and culture.

3.3. Connection to Moort and Kin

In the illustration below (Figure 5), the progression of the Child, Hunter, and Elder is depicted. Noongar people hold sincere, deep connections to one another, including relationships from the past, present, and future. The moort and kin relationships are central to being, doing, and knowing. The connection with others defines koorlangka identity, shapes values, and orients their sense of belonging.

Figure 5.

Connection to moort and kin: Yarning Circle 8.

In Noongar society, moort is a collective of bloodline relationships that extend beyond immediate blood relations to intricate kinships and include Ancestors, Elders, and seniors. In the illustration below, the lines between Child, Hunter, and Elder are integral symbols depicting lineage and cultural continuity. Noongar stories of life and living, traditions, and knowledge are passed from Elder to Child.

The place of an Aboriginal child within a moort and extended kinship is taught at an incredibly early age. Their inheritance is the role and responsibilities that are bestowed upon children by Elders, and which are overseen by senior moort members. The way a child sees themselves in relation to their moort, kin, Elders, and Ancestors provides a central source of the interconnectedness of learning about the intricacies of self, moort, kin, country, and culture.

Strengthening connections to ancestors and community is depicted by children in their drawings of totem and skin groups, which are often represented by animals, natural elements, plants, and patterns. These images reflect the strengthening connection koorlangka to moort, kin, local community, wider community, and Ancestors (Kickett-Tucker 2008, 2025).

3.4. Connection to Katitjin (Culture)

Children’s depictions of culture show their understanding of their sense of place within the Noongar worldview. Culture is passed down through the generations and relies on the strong connections to country, moort, kin, and self.

The symbols used in Yarning Circles 4, 9, and 10 (illustrated below) in Figure 6, hold unique meanings of culture. The expressions of connection to land and identity are represented in Yarning Circle four by images of history (ships and death), totems (animals), cultural practices and ceremonies (pathway/journey), and Dreamtime stories (celestial objects).

Figure 6.

Connection to Katitjin: Yarning Circles 4, 9, and 10, respectively.

In Yarning Circle nine, the Hunter and Elder are depicted with text describing ceremony, dances, art, smoking rituals, and daily cultural practices, such as bush tucker (hunting) and medicines.

Yarning Circle ten is a word cloud about culture and includes dances (spirit dance, kangaroo dance, emu dance, “show off” dance, bee dance), Dreamtime stories, art, lands (cave), and hunting tools (spears, boomerang, axe, women’s digging sticks).

The assertion of culture in the images above provides a platform for children to celebrate their knowledge, reaffirm their connections to culture, and strengthen their identity. In fact, they have an innate “expertise” in which they know intimately about their culture and connection to self and identity in ways “others (non-Aboriginal)” can only “see” in a superficial way. This expertise is part of Aboriginal children’s ‘essence’ in a vital way that supersedes the other ways in which they may be positioned or identified by others. It is like an aura that is invisible to others who may see but cannot or do not hear or feel. It is much like armour or, in the parlance of health promotion, a ‘protective factor’ for the environments and spaces where Aboriginal children are often not culturally safe. In doing this, koorlangka travel forward in life, secured with a personal conviction of truth, tradition, and tales about themselves and the world around them. Their creations serve as a living reminder of the strength of Noongar children in their exploration of self, country, culture, and kin.

In the Noongar world, children are not passive in their life journey nor in their learning along the path. They are keen, active contributors who not only receive knowledge but are also keepers of knowledge who, in turn, model the learning behaviours from adults, i.e., parents, kin, and Elders. They reciprocate the ways of learning and, importantly, pass on the knowledge they have received. They, in turn, pass this on to their siblings, kin, and wider social circle. This continuous cyclic exchange is part of our ways of knowing and doing. Children are active agents whose roles, responsibilities, and obligations are taught and modelled from a young age. Yet, this cultural way of knowing, learning, and doing is in direct contrast with the Western system of education, where compliance, rigidity, and standardisation are the expected and enforced norm. Conflict for the child arises in relation to ways of doing and expectations. Acknowledgement by the school system and leaders of this stark difference is not good enough. What is needed is a more culturally responsive and empowered approach that actively respects and honours the agency, rights, and identity of Aboriginal children in schools so that their full humanity flourishes.

4. Translation of Drawings into VR Game Elements

Guided by the Noongar lead researcher, a process was developed that enabled the deep integration of traditional and contemporary knowledges, mixed with stories shared in yarning and storytelling with Aboriginal students, Elders, and parents and carers. Moombaki staff and carers teased out ideas with animation and game design undergraduate students supported by their expert lecturer. This back-and-forth process occurred over a 2-year period to ensure that connections to Noongar culture, country, moort, kin, and self are woven into the fabric of immersive virtual technology.

4.1. Connection to Katitjin

The heartbeat of the start and end of this project was Noongar katitjin. Noongar students stated that culture is “what you represent” and “is all around you” (S1/YC8–9, p. 2). The yarning circles and game development activities showed that Noongar protocols, ceremonies, stories, dreamtime, languages, and traditional practices are the sacred concentric connections to living and thriving. These elements were incorporated into Moombaki Noongar 3D Quest gameplay via quests appropriately named by Noongar students as “boss battles”, such as the three-headed Emu boss battle. Culture was also portrayed by the game characters, such as the totems, i.e., pindi pindi, the butterfly that changes to a bright colour when the player finds the bush food and feeds the butterfly. Other characters included in the game were the hunter who used his spear to fish.

4.2. Connection to Moort and Kin

Koorlangka illustrations showed interactions with moort and kin (i.e., child–hunter–Elder as depicted in YCs 8 and 9) and, hence, their awareness of moort and kin connections, including protocols for communication, respect, roles, and responsibilities. One of the activities in the Moombaki Noongar Quest 3D gameplay involved the gamer finding the mia mia (home) for the totem that they were bestowed. More specifically, the gamer must explore identical totems and nurture them by placing them in their rightful campsite home. The gamer is encouraged to explore their role as carer and ensure the moort and kin have safely journeyed home.

4.3. Connection to Boodja and Self

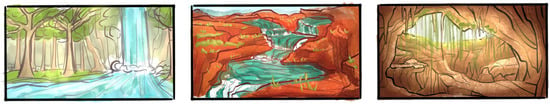

“Land is your blood” (S1, YC9/1, p. 2), according to Noongar students aged 10–11 years; hence, Wadjuk Boodja is sacred; therefore, the game is created around Noongar landscapes, including gum trees, brown earth, wildflowers, rocks, and waterholes, for instance. The use of a familiar environment for students is integral to reflecting the real landscapes of Noongar territory. The interactions that occur on Boodja teach gamers about the holistic connection they have with themselves, their people, and the environment. The connection of self and country was translated into the 3D game through the main game objective, whereby gamers were bestowed an animal totem that needed care and protection in the environment, such as the kangaroo (yonga) in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional game development of the Yonga (kangaroo) Totem.

5. Pathway to Noongar Thriving—VR Style

When interactive game elements are opened in the Moombaki Noongar Quest, the gamer is connected to a knowledge balloon that explains the importance of the design, character, or feature in Noongar culture. Through this way, koorlangka are proactively learning Noongar culture and language, in a fun, self-directed, relaxed, and self-paced virtual environment that provides a highly immersive 3D experience.

5.1. Characters

Animals, totems, Ancestors, hunters, and children are depicted in koorlangka illustrations, and these have been transformed into interactive figures. They pursue their quest, hunt, perform a dance, prepare the mia mia, create sand markings, and look after their totem, and this is all based on the symbolic meanings attributed by the co-creators.

5.2. Environment

Creations made by the children commonly featured environmental landscapes (see Figure 8) as well as celestial objects. The VR game allowed for terrains and times in which the gamer navigated the VR world.

Figure 8.

Early game development illustrations of the environment.

5.3. Ancestors and Spiritual Symbols

Key characters such as Elders and woodatji (spirit being) were incorporated into the VR game to uphold the generational Dreamtime stories and contemporary learnings of Noongar culture and storytelling.

5.4. Interactive Components and Gameplay Design

Hunting tools such as spears, digging sticks, and a kodja (axe) were featured in the koorlangka yarning circles. These tools have been included as interactive elements in the VR game. Similarly, Elders are the guiding characters who teach the Noongar language and culture along the 3D journey.

The design of Moombaki Noongar Quest 3D mirrors the protocols of Noongar culture, and, therefore, quests and storytelling are prominent features of the game. Quests involve finding the appropriate bush food, solving puzzles using traditional knowledge, and understanding Aboriginal history, for instance.

Moombaki Noongar Quest 3D is more than a tool for fun. It is part of a dynamic multimodal learning platform for Noongar cultural education that encourages children to deeply connect with their culture, country, moort, kin, and self in an immersive, interactive way. Blending traditional knowledge and language with innovative technology, Noongar children can thrive, remaining grounded in their roots and learning and understanding about themselves, their people, and their culture in a meaningful way.

6. Discussion

Moombaki has played an enabling role in supporting Aboriginal children, particularly Noongar children, to express their identity and knowledge of their culture. Moombaki has helped students to connect and, in some cases, re-reconnect cultural knowledge; moreover, it has provided a bridge for growing a sense of belonging and acceptance in which critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity are supported.

Moombaki Noongar Quest 3D represents an opportunity for school leaders to adopt an expertly designed, place-based classroom resource that the local community has been directly involved in developing and which represents and speaks meaningfully to Aboriginal children. It is a culturally appropriate resource which provides the opportunity for Aboriginal children to be expert gamers in an immersive and interactive 3D experience comprising content and quests that are deeply relevant to them and their families. These findings mirror the key outcomes from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework and Education Australian Government in tackling declining students’ education outcomes, such that

improving school attendance in Indigenous communities requires concerted action between well-resourced schools and communities to create local strategies that are context sensitive, culturally appropriate, collaborative, and foster lifelong learning … School engagement, including self-identity … connectedness … culturally inclusive practices in schools; and the wider environment, including parental and community involvement.(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and National Indigenous Australians Agency 2024)

In addition, it is vitally important that the interrelated connections Aboriginal children feel toward their moort, kin, country, and culture are supported in schools. For the Noongar koorlangka in this study, the VR game represented more than just entertainment. It was an active tool through which they could learn their culture and language. Aboriginal students can journey into and out of natural, familiar landscapes, be active actors in the Dreamtime stories and advance in quest adventures.

The Moombak Noongar VR Quest is part of a 5-year project that complements a multimodal suite of resources, such as curriculum lessons, activity sheets, PowerPoint presentations, cultural excursions, and a cultural integrity audit called ngalang moombaki kadjininy warniny, which means “Our Moombaki way of active listening, understanding, knowing, feeling & doing”. The next phase is to work with the Moombaki Aboriginal Community Controlled Partner to deliver the program and then to scale up for development across other regions in metropolitan Boorloo for primary schools. Following this, we aim to design and build a version of Moombaki with and for Aboriginal secondary students.

In sum, the Moombaki program supported Aboriginal students by helping them to stay connected to their roots of moort, kin, country, and culture while learning about themselves in a contemporary world. The future, present, and past can thrive as evidenced by the futuristic modernity Moombaki VR game, which has successfully bridged the past and present in a digital world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.K.-T., D.J. and J.D.; methodology, C.S.K.-T.; formal analysis, C.S.K.-T., J.D., D.J. and D.C.; writing—C.S.K.-T. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, C.S.K.-T., J.D., D.J. and D.C.; project administration, C.S.K.-T.; funding acquisition, C.S.K.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study and related research activities were funded through an Australian Research Council Discovery Indigenous Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Office, Curtin University (HRE2020-0277) and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (Ref 984) was granted before recruiting participants. Confirmation to conduct the study at the schools was also required and obtained from the Department of Education WA (D20/0643193).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the research.

Data Availability Statement

The data cannot be shared publicly in compliance with the ethics approval received.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, and National Indigenous Australians Agency. 2024. Education Outcomes for Young People (Measure 2.05). Available online: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-05-education-outcomes-for-young-people (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Australian Government, Wheatbelt Natural Resources Management, Northam. 2013. Nyungar Budjara Wangany: Nyungar NRM Wordlist & Language Collection Booklet of the Avon Catchment Region. Available online: https://www.noongarculture.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/nyungar-dictionary.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2020. The Rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Australia: A Report on Cultural Safety and Identity. Melbourne: Australian Human Rights Commission. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/australia#:~:text=Australia's%20indigenous%20people.-,Children's%20Rights,of%20children%20and%20young%20people (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Biddle, Nicholas, and Hannah Swee. 2012. The Relationship Between Wellbeing and Indigenous Language Use. Australian Geographer 43: 215–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Margaret. 2009. Drawing, visualisation, and young children’s exploration of “big ideas”. International Journal of Science Education 31: 319–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Ceri, and Marnee Shay. 2021. Context and Implications Document for: From resilience to wellbeing: Identity-building as an alternative framework for schools’ role in promoting children’s mental health. Review of Education 9: 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, Len, Sandra Harben, and S. Van Den Berg. 2004. Nidja Beeliar Boodjar Noonookurt Nyininy: A Nyungar Interpretive History of the Use of Boodjar (Country) in the Vicinity of Murdoch University. Murdoch: Murdoch University. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing. Barton: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2000. Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. London: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Dinku, Yonatan, Francis Markham, Denise Angelo, and Jane Simpson. 2025. The connection between social and emotional wellbeing and Indigenous language use varies across language ecologies in Australia. Social Science & Medicine 364: 117547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, Pat, Helen Milroy, and Roz Walker, eds. 2014. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Farokhi, Masoumeh, and Masoud Hashemi. 2011. The analysis of children’s drawings: Social, emotional, physical, and psychological aspects. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences 30: 2219–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Yaqoot, Anne Cleary, Stephanie King, Shaun Solomon, Lisa McDaid, Md Mehedi Hasan, Abdullah Al Mamun, and Janeen Baxter. 2022. Cultural Identity and Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children. In Moort Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies. Edited by Janeen Baxter, Jack Lam, Jenny Povey, Rennie Lee and Stephen R. Zubrick. Cham: Springer, vol. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, Graham John. 2016. Resilience and recovery from trauma among Aboriginal help-seeking clients in an urban Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation. Australian Psychologist 51: 436–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickett-Tucker, Cheryl S. 2008. Children’s Self-Identity and Self-Esteem in the Context of Cultural and Community Connections: A Study of Urban Aboriginal Children in Western Australia. Doctoral dissertation, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia. Available online: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/196 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Kickett-Tucker, Cheryl S. 2021. Cultural learnings: Foundations for Aboriginal student wellbeing. In Indigenous Education in Australia: Learning and Teaching for Deadly Futures. Edited by Marnee Shay and Rhonda Oliver. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kickett-Tucker, Cheryl S. 2025. School of Education, Curtin University, Bentley, WA, Australia. Noongar Wadjuk Cultural Knowledge Shared During Project Development. Unpublished cultural knowledge/Personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- Kickett-Tucker, Cheryl S., and Roma Winmar. 2016. Noongar Welcome [Performance]. Perth: Governor Stirling Senior High School, NAIDOC Week. [Google Scholar]

- Kickett-Tucker, Cheryl S., and Shaouli Shahid. 2019. In the Nyitting Time: The Journey of Identity Development for Western Australian Aboriginal Children and Youth and the Interplay of Racism. In Handbook of Children and Prejudice. Edited by Hiram E. Fitzgerald, Deborah J. Johnson, Desiree Baolian Qin, Francisco A. Villarruel and John Norder. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Bruce D. 2009. Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma 14: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. 2024. Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report. Canberra: Productivity Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, Marnee, Grace Sarra, and Jo Lampert. 2023. Indigenous Education Policy, Practice and Research: Unravelling the Tangled Web. Australian Educational Researcher 50: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackrah, Rosalie D., Dawn Bessarab, Lenny Papertalk, Samantha Bentink, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2021. Respect, Relationships, and “Just Spending Time with Them”: Critical Elements for Engaging Aboriginal Students in Primary School Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, Bronwyn, Masud Hasan, Emily Colonna, Makayla-May Brinckley, Siena Montgomery, Mikala Sedgwick, Katherine A. Thurber, and Raymond Lovett. 2024. Exploring Links between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Language Use and Wellbeing [Research Update]. Canberra: National Centre for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing Research, Australian National University. Available online: https://mkstudy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Summary_MKFLA_language-wellbeing_240829.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Wright, Michael, and Cheryl S. Kickett-Tucker. 2017. Djinangingy kaartdijin: Seeing and understanding our ways of working. In Mia Mia: Aboriginal Community Development–Fostering Cultural Security. Edited by Cheryl Kickett-Tucker, Dawn Bessarab, Juli Coffin and Michael Wright. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).