Abstract

Selecting national emblems is crucial for the development of a national identity. This paper presents all official proposals for the coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia, starting in 1992, with the proposals of the public competition for the selection of the coat of arms, flag, and anthem of the Republic of Macedonia, and finishing with the last Government proposal in 2014. All of the proposals are categorized according to their main symbol, a sun or a lion. The long and complex process of creating national symbols shows that there is a deep division regarding which one to use.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to present and discuss all the official proposals for the coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia, starting with the proposals of the public competition for the selection of the coat of arms, flag, and anthem of the Republic in 1992, and going up to the latest Government proposal in 2014. The documents of the process of the Assembly (Parliament) of the Republic of Macedonia on creating national emblems, that occurred in 1992, are found in the State Archive of the Republic of Macedonia, Fundus 1304: “Sobranie 1990–1994”, Materials for 41 session, held on 11 August 1992, points 2, 3, and 4, box 46. It contains the proposals of the Law on the Coat of Arms, Flag and Anthem of the Republic Macedonia, and the amendments starting from 1 June until 22 October 1992.

Unfortunately, the original images of the proposals have not been preserved. Therefore, this document presents reconstructions based on published photographs and the descriptions given in those proposals. The daily newspaper “Nova Makedonija” completely covered the entire process and published photos of the proposals. Interviews with Todor Petrov, an independent MP very active in this process, provide additional information on his proposals, as well as those of others. Also, there is input from some of the participants in the process. The reconstructions of the coat and flag proposals are by Jovan Jonovski.

Macedonia is situated in the Balkan peninsula in south east Europe. The oldest heraldic symbol associated to a territorial entity in the northern part of Macedonia is the banner over the city of Skopje. It is found on a naval map, dated 1339, by Italian cartographer Angelino de Dulcherto. On this map showing main ports, Skopje is depicted with a banner over a fort and the inscription “Scopi” next to it. The banner is Or a double-headed eagle Gules.1 Reflections on European heraldic practices could be seen in the Balkans below the Danube River, where just a few rulers used arms. This as (Ацовић 2008) notes, was “heraldry of emblems, not heraldry on rules”. Just half a century later, Skopje came under the administration of the Ottoman Empire. This started a period in which there was no real possibility for bearing arms due to the Islamic view of the use of images.

However, at the end of the 16th century, several wealthy families from the Republic of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) had an armorial created containing around 160 family arms, and 9 so-called “land” coat of arms.2 This armorial, with its copies and versions, are known as Illyrian Armorials, and, the coat of arms they contained, as Illyrian arms or Illyrian heraldry. Later, at the beginning of the 18 century another heraldic work, known as Stematographia, appeared, containing the Illyrian land arms and many other territorial arms.3 These heraldic works will later influence the ideas for symbolic design of the new developing nations in the Balkans.

In 1919, following the Balkan wars (1912–1913) and WWI, the territory of the modern-day Republic of Macedonia was incorporated into the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later named Yugoslavia). The first ideas about the existence of a historical Macedonian coat of arms appeared in 1968. This became public with the publishing of the book “The Coats of Arms of Macedonia,” written by Aleksandar Matkovski in 1970. The book presents two dozen Illyrian Armorials, where the land arms of Macedonia were present. The author concluded that the “real” coat of arms of Macedonia is Gules, a lion queued forchee, crowned Or. This idea reappeared in 1990, with the second edition of Matkovski’s book, gaining great popularity.

The choice of an emblem sends a message, both through its form and its content. The design of a symbol to represent a national identity is a product of specific, socio-political events that surround its adoption, as a process of wider social forces that go beyond national borders (Cerulo 1995, p. 2). The choice of national symbols is a process in which a symbol or a symbolic composition is selected from a multitude of possible symbols. Through their application, promotion, the construction of the story of their occurrence, continuity, and significance, they are further built as national symbols, being crucial for building the identity of a political nation.

The choice of the symbols for the coat of arms and the flag is not unambiguous, in the sense that there is not only one symbol, or one symbolic composition, alone, which perfectly represents the armiger. It requires a process for selecting not only a symbol but, also, a specific design. Symbols may be chosen or designed in a closed process where work is given to one designer, a small team of experts (the traditional approach), or through a public competition. When selecting a symbol, the primary message that needs to be communicated is considered the most important.

Laswell et al. (1952, p. 15) distinguishes three categories of national symbols, i.e., emblems: (a) symbols of identification—with traditional or historical heritage; (b) symbols of preference—freedom, independence, fraternity, justice, etc.; and (c) symbols of aspirations or expectations—progress, the inevitability of a world revolution, the proletariat (an icon of an economic class), and so on.

In Europe, most state coats of arms fall into the first category, with all national emblems until 1948, being selected in the traditional way. Until 1990, the same was for the coats of arms of the Balkan states, with the exception of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia having the only emblem from the second category—symbols of preferences—those of the brotherhood and unity of its peoples. The coats of arms of Serbia4, Bulgaria5, and Albania6, are taken from historic Illyrian arms. The coat of arms of Greece underwent several changes, from an ancient composition to a simple cross.7

But, there are situations where it is desirable for historical continuity to be avoided. In that case, there could be a public competition where artists have the opportunity to “invent” a new emblem.8 The first such example is the emblem of Italy.9 Public competition for a state emblem is usually conducted in countries with internal conflict, as a way to create new symbols without historical reference to the related sides of the conflict.10

The flag of Cyprus was adopted in 1960 after a public competition, in which the condition was that it not contain blue, red, a cross or a crescent, as these were symbols of the opposite parties. The design, with the contours of the island and olive branches, was by Ismet Gunei, a Turkish Cypriot.

The choice of state symbols in Kosovo followed the pattern of conflict symbols.11 Albanians in Kosovo used the flag, coat of arms, and anthem of the Republic of Albania, which they regarded as national, rather than state, symbols. Therefore, new symbols, other than those perceived as national ones, needed to be created. The flag of the Republic of Kosovo was adopted immediately after the proclamation of independence on 17 February 2008. The flag’s design was a result of an international public competition, organized by UNMIK,12 and attracted nearly a thousand proposals. In these circumstances, the use of symbols used by the conflicting entities in Kosovo was banned. The winning design was by Muhamer Ibrahimi, and it is also was displayed on the emblem of Kosovo. The flag of Kosovo has a blue background, bearing the outline of Kosovo, on which six golden stars are placed in an arch. The stars officially symbolize the six main ethnic groups in Kosovo.13

2. The Choice of Symbols of the Republic of Macedonia

Independence in 1991 found Macedonia “symbolically” and “emblematically” unprepared. The People’s Republic/Socialist Republic of Macedonia used three symbols for forty years: the star from the flag, the mountain, and the sun from the state emblem (Figure 1).14 During the last decades of the 20th century, two symbols—the golden lion, and the golden sixteen-rayed sun on a red field—were slowly introduced. These symbols, previously used by the Macedonian diaspora, were slowly introduced to the public space inside Macedonia. An example of this would be the rally in Skopje for the proclamation of the results of the Referendum on 8 September 1991 (Референдум во Македонија 1991).

Figure 1.

The Soviet style emblem of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, officially called “Coat of Arms”15 from 1970 book “The Coats of Arms of Macedonia” by Aleksandar Matkovski.

Towards the end of 199116, the political parties represented in the Assembly were in favor of a public competition to select the state symbols, without mentioning any specific symbol. The political Party VMRO-NP17, although supporting the public competition, advocated a specific proposal for a coat of arms with a lion (Чангова 1991).

On 26 December 1991, the Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia established the Commission for Constitutional Affairs to assume the role of carrying out the activities for the preparation and adoption of the Law on the Coat of Arms, the Flag, and the Anthem of the Republic of Macedonia. The commission formed a working group, led by Tito Petkovski, which adopted the schedule according to which a public competition should be held, and the Law should be enacted no later than 20 May 1992, in accordance to the Constitutional Law (Петров 1992).

The competition lasted from 25 March until 10 April 1992. Article 3 of the document reads (Службен 1992):

“The proposals for the coat of arms, flag and anthem of the Republic of Macedonia should express the statehood, independence and sovereignty of the Republic, its historical traditions, cultural heritage, the aspiration for social and spiritual progress, the natural characteristics of the Republic, unity and coexistence and the modern aspirations for a democratic society and European and World Integration.”

A total of 275 proposals with many variants were submitted in the contest, of which 239 were for the coat of arms and the flag, and 36 for the anthem (Стенографски 1992, p. I/7). The majority of the proposals included different designs of suns and lions. The Commission chose three sets of designs bearing code names Feniks 92, MAKO, and 5522, which were publicly presented on 5 June 1992, from which the final proposals had to be selected (З. Д. 1992).

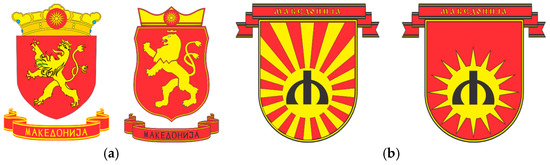

The code name “FENIKS 92” proposed a coat of arms with a lion in several color combinations: Gules a crowned lion Or, Sable crowned lion Or, and Gules crowned lion Sable (Figure 2a). All resemble, too closely, the arms of existing states, while the third violates the rule of tincture of arms. The code name “MAKO” proposed coat of arms with the sun from the current state emblem, but represented it with 16 thin divergent rays, (as popularly perceived (Jonovski 2015, p. 168)), and one proposal with Or lion Gules (Figure 2b). The code name “5222” proposed a red shield with a yellow sunrise over blue waves. There was also a version with a black sun and waves on red and on a yellow shield, both breaking the heraldic rule of tinctures. Under the shield, there is a red ribbon with the text “Makedonija” (Figure 3a) (З. Д. 1992).

Figure 2.

(a) Proposals by “FENIKS 92”18; (b) Proposals by “MAKO”.

Figure 3.

(a) Proposals by “5522”; (b) The requested proposals by “FENIKS 92” for the arms and the flag.

In the end, the Commission asked the selected designers to submit a further proposal with the same new golden sun on a red field for the arms and for the flag. The proposal submitted under the code “FENIKS 92” (Figure 3b) was accepted and included in the commission’s official Draft Law on the Coat of Arms submitted by the MPs Tito Petkovski, Zoran Krstevski, and Kiro Popovski on 20 June 1992, as well as a proposal for a flag with the same sun. The draft proposal states:

“The coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia is a shield with a red field enclosed with a yellow (golden) edge. In the middle of the shield is a yellow (golden) sun. The sun has 16 primary rays that break in 32 rays, 16 of which are at the top of the primary, and the other 16 are in the middle between the two primary rays. Under the shield is a ribbon on which is written “Republika Makedonija.”

The explanation on the proposal for a coat of arms and a flag with a 32-ray sun, and explanation of the whole process, was given by the Chairman of the Working Group of the Commission on Constitutional Affairs, Tito Petkovski. The only mention of significance or symbolism is the historical continuity of the golden yellow and red colors associated with the flags of the uprisings. These colors are present in the symbols of the Albanians and Turks who, for centuries, lived together with the Macedonians in these areas. Also, those are symbols that our citizens did not perceive as representing an enemy, an occupier, or slavery (Стенографски 1992, p. I/12).

The sun as a symbol, and its meanings are not mentioned at all, but defensive statements follow that these symbols are free from the claims of renewal of great kingdoms from the past. Also, that these symbols do not offend other nations and citizens of other states, that no foreign symbol is adopted, and that they are not symbols that will have widespread harmful associations among certain nations and states. Finally, the Commission “considers that they have historical understanding and are an expression of the state-legal continuity of the Republic of Macedonia” (Стенографски 1992, p. I/12).

This is probably the only explanation of a state emblem in the world where the emphasis is on the inoffensiveness of the symbols to other states and nations, while the symbols themselves, and their intended meanings, are not mentioned at all.

Regardless of this process, the MPs made many proposals and, very often, after being rejected, the same proposals were resubmitted. The first proposal for the coat of arms included a lion derived from the land arms of Macedonia from the 1620 Belgrade Illyrian Armorial, with a blazon Gules, a lion Or, queued forchee, crowned with a ducal crown. Above the shield, the same crown with the name “Makedonija” on a scroll (Figure 4a). The inclusion of a name is not strictly permitted in an armorial achievement (Петров 1992).

Figure 4.

(a) Generic proposal of the “Macedonian lion”; (b) The proposals by Todor Petrov based on the design of the flag.

This coat of arms, Gules crowned lion Or, was the one most often suggested in the process of choosing the arms, accompanied with different inscriptions on the ribbon under the shield:

- With the text “Makedonija”, in the proposals of Todor Petrov of 1 June 1992; Blagoj Toshev of 31 July 1992; Vladimir Golubovski of 12 August 1992; and, again, Todor Petrov of 17 August 1992.

- With the text “Republika Makedonija”, in the proposal of Dragi Arsov of 20 June 1992; Aleksandar Florovski et al. of 22 July 1992; and Dragi Arsov of 12 August 1992.

- With “Macedoniae” in the proposal of Vladimir Golubovski of 7 August 1992.

- Without any text in the proposal of Todor Petrov of 8 June 1992.

The first proposal by Todor Petrov for the flag had a sixteen-rayed sun, now known as the Kutlesh/Star of Vergina, which eventually received the support of the majority. Then, following the initiative of Todor Petrov on 30 July 1992, an agreement was reached between the political parties for a coat of arms with the same sun with a description (Figure 4b):

The coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia is a quadrilateral shield with a red field enclosed with a golden-yellow edge. In the middle of the shield there is a golden-yellow sun with eight primary and eight secondary rays, slightly thickened in the first half, intermittently and symmetrically arranged around the solar disk. The basic solar rays are directly detached from the solar disk, and the final outer length of all sixteen sun rays coincides with the outer periphery of the sun.

The diameter of the solar disk is one-sixth of the length of the shield. The ratio of the diameter of the solar disk to the length of the basic solar rays is one to two, and the ratio of the length of the secondary and basic sun rays is seven to eight.

Under the shield there is a red ribbon with a golden-yellow edge on which word “Makedonija” is written with golden-yellow letters.

The existing national anthem, “Today over Macedonia”19, and the flag, was voted on during the 41st session on 11 August 1992. The flag is described as “The diameter of the solar disk is one-seventh of the width of the flag. The ratio of the diameter of the solar disk to the length of the primary solar rays is one to two, and the ratio of the length of the secondary and primary rays is seven to eight.The center of the sun coincides with the point at which the diagonals of the flag intersect. The ratio of the width and length of the flag is one to two (Figure 4b)” (Службен 1992).

However, no agreement was reached on the arms because VMRO-DPMNE, again, returned to the proposal for a coat of arms where a lion is a charge. Then, two “compromise proposals” were proposed with a lion and a sun: by Todor Petrov on 17 August 1992 (Figure 5a left), and by Tomislav Stefkovski and Gorgi Kotevski on 18 August 1992 (Figure 5a right), where the sun is set on the disc on the crown. The sun in the crown, heraldically, is only a decoration that does not change the arms which, in this case, is a Gules lion, queue forchee crowned Or. This proposal was not supported by the Constitutional Commission.

Figure 5.

(a) Left: “Compromise” proposal by Todor Petrov, right: by Tomislav Stefkovski and Gjorgi Kotevski; (b) Proposals by Dimitar Dimitrovski.

The Government of Nikola Kljusev actively participated in the process and expressed its opinion on all proposals. Nevertheless, in this period, there was a political crisis leading to a change of government in September 1992. The new government led by Branko Crvenkovski no longer considered the adopting of a state emblem to be a priority.

However, by the end of the year, there were several more proposals for the emblem, including the sun. Dimitar Dimitrovski’s proposal of 25 August 1992 presents the sun with 16 thin divergent rays from the code name “MAKO”, that could be blazoned Gyronny of thirty-two, Or and gules, a sun-disc of the first. The coat of arms is displayed on a Spanish-style shield, where a yellow sun is charged with the “first letter of Glagolitic script, AZ” (meaning “I”). Under the shield, there is a “ribbon with “Makedonija” in stylized Old Slavic letter (Figure 5b).

In the second proposal of Dimitar Dimitrovski, of 18 September 1992, and reaffirmed on 7 October 1992, the central sun with 16 rays was used from Tito Petkovski’sproposal. As in the first, the letter “AZ” in black is placed on the sun and, in the description, an explanation of the dimensions of the elements is given (Figure 5b).

The last proposal was from a group of MPs led by Bozho Rajchevski, dated 22 October 1992. The letter “M” is set on the sun disc, and three wavy lines on the lower rays were added to the proposal Todor Petrov (Figure 6). The Commission took a positive view of this proposal, but a dispute with Greece over the use of sixteen-rayed sun had already begun and its use was no longer an option.

Figure 6.

Proposal by Bozho Rajchevski.

In the process of determining the flag, the sun is presented as a symbol in two forms, both with convergent types, one with 16 rays and the other with 32 rays. The colors remained constant: a golden sun on a red field. There is still a difference in interpretation, whereby the sixteen-rayed sun is interpreted as expressing continuity with the ancient Macedonian dynasty of Philip and Alexander20, while the 32-ray sun is a completely new, so far unknown design, which should be used for the future.

For the coat of arms, there was a “struggle” between the symbols of the sun as in the flag described above, and a crowned lion. In the debate, nobody challenged the historicity of the lion as a symbol of Macedonia, but questioned its appropriateness in modern times. Only the MPs of VMRO-DPMNE, VMRO-NP, as well as the three independent MPs, advocated the lion. The other two-thirds of the MPs were against it.

The proposal for the coat of arms that received the greatest level of support during the process was that with a sixteen-rayed sun, just like that on the adopted flag. VMRO-DPMNE initially supported it, but later withdrew their support and returned to the initial proposal, for a coat of arms with a lion. By doing so, the process of selecting the coat of arms was postponed until further agreement was reached.

3. Proposals with the Sun after 1992

The flag with a sixteen-rayed sun was met with huge hostility by the Hellenic Republic21, leading to an embargo lasting 3 years, and ending with the Interim Accord, prescribing changing the flag. The proposals for the new flag were undertaken by Miroslav Grchev (Grchev 2011).

For all variations of the flags created during this secret process of designing the new national flag, matching designs for the coats of arms were made with the matching designs for the sun (Figure 7). All shields were red, with a golden general shape of the crown atop. The crown was the adaptation of a crown designed by Miroslav Sutej for the achievement of the Republic of Croatia (Stančić 2007), thus immediately associating it with the Croatian arms. In the following period, only the designs for the flag were published, while the draft proposals of the arms were kept secret. The flag was finally adopted on 5 October 1995, but the proposals for the coat of arms did not find a place in the parliamentary procedure (Grchev 2011, p. 3).

Figure 7.

Proposals by Miroslav Grchev.

The state leadership held that only minimal concessions under the Interim Agreement should be given. Changing the arms could have opened the door for changing the national anthem, perceived at that time as an internal affair.22

Proposals for preserving the sun on the existing coat of arms then followed. One was the process of “heraldization” of the existing state emblem, through the so-called Slovenian solution. Elements of the coat of arms: the sun, the mountain, and the river should be placed on the shield, along with removing the wreath and the ribbon. In 1998, this was proposed by Jovan Jonovski (1998). Later, several others made similar proposals (Figure 8).23

Figure 8.

“Slovenian solution” by Darko Gavrovski (Гавровски 2001).

A second solution was the preservation of the existing state emblem, but with the removal of the five-pointed red star. The initial proposal was by Faik Abdi on 30 July 1992. The proposal for the flag was to replace the red star with the emblem. This proposal was repeated by the Social Democrat MP, Nikola Popovski, several times, in 1995 (А.Х. 1995) and in 1998 (Војновска 1998). The proposal was again repeated in 2000 and 2007, by the then-Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski.

Finally, on 16 November 2009, without a public and parliamentary debate, the new Law on the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia was adopted, with the old-new design of the state coat of arms (Војновска 2009). In place of the red star, the stalks were joined (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia, 2009.

Article 2 of the Law on the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia describes it this way (Службен 2009):

- (1)

- The coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia is a field surrounded by stalks of wheat that connect to the top, intertwined with fruits of poppy and tobacco leaves, which are connected to the bottom with a ribbon embroidered with folk motifs.

- (2)

- In the middle of the field there is a mountain, and in the foothills a river flows, and the sun rises behind the mountain.

This solution, announced as an interim solution that could be later explored and lead to another coat of arms, produced many negative reactions from the heraldicallyinformed members of the public. One major reason for this was they considered the removal of the red star as not solving the problem of removing the ideological connotation of the arms. They also thought they should wait for the result of the scheduled referendum on a Law for the coat of arms with a lion. (This was an initiative of the VMRO-NP who organized the collecting of signatures.)

4. Proposals with a Lion

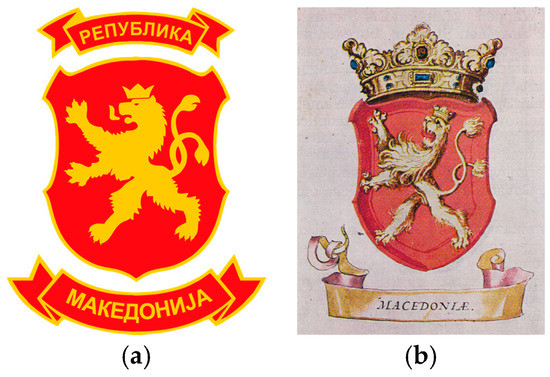

The first attempt for an agreement on adopting a new coat of arms with a lion was in 199424, on the initiative of Todor Petrov who, as an independent MP, managed to obtain the initial consent of the two major parties on a proposal for the Coat of Arms design of Social Democrat Miroslav Grchev. The Gules, a Lion queue forchée Or (crown in the chief Or) received approval to enter the Assembly procedure (Figure 10). Unfortunately, before the session on which this proposal was to be considered, there was a misunderstanding between the parties over a completely different point of the agenda. As a result, the proposal failed to enter the Assembly session.25 The same proposal, in 2000, was part of the initiative of the World Macedonian Congress to collect 10,000 signatures for passing a package of laws,26 including the Law of the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia. (До средствата 2000).

Figure 10.

Proposal with lion by Miroslav Grchev.

In February 2001, Jovan Pavlovski, in an interview with “Start”, gave the proposal for the coat of arms Or, a lion Gules, which appeared on the flag of the Razlog Uprising of 1876 and in the Zefarovic’s Stematographia (Figure 11). This coat of arms was applied to the flag, resulting in the first real use of the national flag under which the Macedonians fought for freedom. On the other hand, in the narrative of the land arms of Macedonia from the Illyrian arms (Gules, a lion Or), is perceived as the “forgery” by don Pedro Ohmuchevic (Шаровски 2001).

Figure 11.

Lion form the Razlovci Uprising flag.

The next proposal was from the VMRO-Vistinska party in August 2001, during the conflict in Macedonia. The proposal was based on the coat of arms of the party itself, with the same Gules lion queued forchee crowned Or, but with the difference that there are two red ribbons above and below the shield on which “Republika Makedonija” is written in gold letters (Figure 12a) (Панов 2001).

Figure 12.

(a) Proposal by VMRO-Vistinska; (b) Land arm of Macedonia from Belgrade Armorial of 1620.

In 2009, VMRO-NP conducted an initiative to collect 10,000 signatures for a referendum on the acceptance of the Coat of Arms drawn from the land arms of Macedonia from the Belgrade Illyrian Armorial of 1620 for the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia. In this campaign, a specific drawing was not made, but, rather, an image taken from the book by Matkovski was used (Figure 12b).27

In 2014, the Government proposed a coat of arms: Or, a lion Gules, and above the shield a mural crown.28 The lion Gules with no crown, and with a single (not forchée) tail, overcame the two problems that other proposals with a lion had faced. It differed in three heraldic ways from the coat of arms of VMRO-DPMNE, and the Coat of Arms of Bulgaria, and more importantly, the Bulgarians had never felt it was their own (Лажна 2014).

For the basis of the concrete graphic illustration, the work of Jerome de Bara from1581 was adopted, with small changes in order to avoid an anthropomorphic appearance of the head, and to strengthen the torso. A golden mural crown with five towers placed on a golden diadem was also added to crown the shield. This crown was also adorned with rubies and pearls from Macedonia.29 The blazon of this coat of arms was changed to read Or, a lion Gules (Figure 13). The vector drawing is by Jovan Jonovski and Kosta Stamatovski from the Macedonian Heraldry Society.

Figure 13.

Government proposal, 2014.

The adoption of this coat of arms required a 2/3 majority, as well as the Badinter majority30, which was secured with the consent of the leader of ethnic Albanian party DUI, Alija Ahmeti. The lion is not unknown as a symbol in the heraldry of Albania, and is present on the coats of arms of many families and cities. In addition, the lion, as a symbol of Alexander the Great, is acceptable for the contemporary perception of the Albanians who consider that Olympia, the mother of Alexander who was from Northern Epirus, is Illyrian, and, according to their beliefs, therefore Albanian.

The final and confirmed proposal was submitted to the Government of the Republic of Macedonia on 29 November 2014. On 5 December 2014, the Government adopted the proposal for the Law on the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Macedonia. A public debate was opened at the Faculty of Philosophy, the Institute for National History, and the Centre for Spiritual Culture of the Albanians. The participants emphasized the significance of the lion as a symbol applied on the arms. However, the discussions suggested that the Or lion Gules is an element deeply embedded in the culture of the citizens of Macedonia. The proposal was to enter the parliamentary procedure where a two-thirds majority was needed for its election.

According to a government statement for the media:

The proposal for the coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia is based on the tradition of coats of arms connected with Macedonia, starting with the illustrations by Willem Verland (+1481) and the Jerome de Bara of 1581, which, through the Stematographias of Vitezovicof 1694 and Zhefarovic of 1741, will become the land arms of Macedonia. In the European armorials, the most consistent representation is the Or lion Gules. The most famous representations are in the armorial of Jerome de Bara of1581 and Jean Roben of 1639, which preceded the Illyrian and originated in European countries with a developed heraldic tradition.

The mural crown on the arms represents the republican arrangement of the state. The towers of the crown represent the graphic expression of the number five which, in turn, is a symbol of statehood. With this, it aims to emphasize and show the sovereignty and integrity of the state. Ruby and pearls are symbols that connect the country with the earth as a natural soil. The lion as a symbol can be seen as unifying by all communities and citizens, because it is a symbol of Macedonians, Albanians, Serbs, Turks, Vlachs, Roma, and other communities, and it represents the land symbol of the country, the territory, the state of Macedonia. It has its own tradition but, also, the present and future of a European Macedonia, which takes care of its past, and also its future, through a symbol that promotes unity and creates unity for all who live in this region, a symbol that brings no division.(Government Communication 2014)

The proposal was, for the most part, publicly supported. There were various illustrations of the possible application of the arms found on social media, such as on passports. One of the critiques came from a public perception, existing for nearly forty years, about the colors of the lion and the shield. From the opponents of the proposal, the main critique was that the lion was too similar to the symbol of the ruling party and, therefore, the party’s coat of arms was being made into the state one. Heraldically, this is not true, because the proposed coat of arms differs in three fundamental ways: (1) the colors of the lion and the shield differ from that of VMRO-DPMNE; (2) the lion has one tail; and (3) the lion is not crowned. But the perception and, thus, critique, was that if it is a lion, then it must be “VMRO”. However, more common were the comments from the practical side: whether this would require additional funds for individuals needing to change personal documents.

Although, initially, there was agreement from the Albanian parties, later, some of the Albanian MPs announced they would not vote for this arms (Интервју—ДУИ 2014) Аs a result, the Badinter majority was lost, and the proposal did not enter the parliamentary procedure. Unfortunately, due to the beginning of a political crisis in Macedonia, the adoption of the coat of arms was no longer a priority.

This proposal is a result of research in heraldic sources over the last 10 years. The discovery of the presence of coats of arms, connected with Macedonia and a whole new world of the attributed coats of Alexander the Great in European armorials completely independent of the Illyrian armorials, began to give another perspective. It is expected this will slowly find its place in this debate, in addition to the established interpretation, as the existing perception begins to change.31 With the increasing availability of digitized armorials of world libraries in recent years, many people have been able to explore these armorials from the comfort of their own homes. Numerous discussions on this topic are being developed at the forum “Kajgana”.32

A high proportion of the arms attributed to Alexander the Great are Or, a lion Gules, as well as the reversed combination of colors (Nacevski 2016). This will lead to a critical re-reading of the book “The Coats of Arms of Macedonia”. Matkovski, himself, included 24arms in the book with the known colors, 13 are with Or, a lion Gules, and 11 Gules, a lion Or. After the publication of the Zetarovic’s Stematographia of a total of 10 sources, mentioned by Matkovski, eight are with a lion Gules, which confirm the actual rule of Stematographia in the heraldic awareness of a coat of arms connected to Macedonia. Thus, the strict understanding is that only Gules, a lion Or is the real and only Macedonian land arms, while Or, a lion Gules is a product of a conspiracy and a series of errors, has no factual or scientific basis (Nacevski 2015).

5. Conclusions

After declaring independence in 1991, all political parties in the Republic of Macedonia were for changing the state emblem and the flag through the competition mechanism, which is closer to the choosing/designing symbols in conflicting countries where two or more parties cannot agree on a symbol, or that the symbol is perceived as belonging to one of the parties.

The basic suggestions for the coat of arms were two-fold: (1) a lion connected with the Land arms of Macedonia taken from the Illyrian arms, and (2) a new design for the sun, free from any claims for the renewal of larger kingdoms and, thus, not offending other nations and members of other states, not being an imported foreign symbol, and not being a symbol that will cause widespread harmful associations among certain nations and states.

One of the reasons for not accepting the arms with the lion lay in the thesis submitted by Matkovski, that the Macedonian coat of arms is Gules, a lion Or, while the Or, a lion Gules is Bulgarian, and wherever it is shown as Macedonian, it is by mistake. Thus, according to Matkovski, Mavro Orbini failed, while Vitezovic swapped the red and the golden lion. That mistake has been repeated in every case where the lion Gules appears as Macedonia’s coat of arms. This became a widely accepted interpretation for 40 years. The situation became more complicated when the party VMRO-DPMNE took the land arms as the arms of the party, making the Gules, a lion Or to be perceived primarily as a party symbol.

The coat of arms with Or, a lion Gules from the attributed coat of arms of Alexander of Macedon from the European armorials, and from the Stematographia, is one of the opportunities to get closer to European countries of the first category of Laswell, and to neutralize conflicts characteristic of the other proposals for the coat of arms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Note

- А.Х. 1995. За грбот Оoслободен од идеолошки симболи…. Дело, April 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ацовић, Драгомир. 2008. Хералдика и Срби. Београд: Завод за уџбенике. [Google Scholar]

- Војновска, Оливера. 1998. Ќе биде ли избран новиот грб. Нова Македонија, April 4. [Google Scholar]

- Војновска, Оливера. 2009. Падна петокраката од државниот грб. Утрински весник, November 17. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, Karen A. 1995. Identity Designs, the Sight and Sound of a Nation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ćosić, Stjepan. 2015. Ideologija rodoslovlja, Korenić-Neorićev grbovnik iz 1595. Zagreb-Dubrovnik: HAZU, Zavod za povjesne znanosti u Dubrovniku, Nacionalna I sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu. [Google Scholar]

- Службен. 1992. Службен весник на Република Македонија. Skopje: Official Gazette of the Republic of Macedonia, # 19. [Google Scholar]

- Службен. 2009. Службен весник на Република Македонија. Skopje: Official Gazette of the Republic of Macedonia, # 138. [Google Scholar]

- Стенографски. 1992. Стенографски белешки од Првото продолжение на Четириесет и првата седница на Собранието на Република Македонија. одржана на 11 август 1992 година. [Stenographic notes]. [Google Scholar]

- Government Communication. 2014. Available online: http://heraldika.org.mk/heraldry/heraldry-arms/state-coat-of-arms/predlog-nov-grb-republika-macedonia/ (accessed on 6 December 2014).

- Grchev, Miroslav. 2011. In Search of the New Flag. In Macedonian Herald 5. Skopje: Macedonian heraldry Society. [Google Scholar]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 1998. Грб—ослободен од идеолошки елементи. Нова Македонија, April 29. [Google Scholar]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2009. Coat of arms of Macedonia. In Macedonian Herald 3. Skopje: Macedonian heraldry Society. [Google Scholar]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2013. Грбот на Република Македонија—тема за дилема. October 18. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=7&v=BSPDqgLqNTw (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2015. Симболите на Македонија. Скопје: Силсон. [Google Scholar]

- Laswell, Harold D., Daniel Lerner, and Ithiel de Sola Pool. 1952. The Comparative Study of Symbols. An Introduction. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nacevski, Ivan. 2015. The relation between the red and the golden lion in the work “Coats of Arms of Macedonia” by Academician Aleksandar Matkovski. In Macedonian Herald 9. Skopje: Macedonian heraldry Society. [Google Scholar]

- Nacevski, Ivan. 2016. Blason of the lion in the attributed arms of Alexander III of Macedonia. In Macedonian Herald 10. Skopje: Macedonian heraldry Society. [Google Scholar]

- Референдум во Македонија. 1991. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvgyAaJjI0E (accessed on 27 February 2017).

- Stančić, Nikša. 2007. How the Coat of Arms of the Republic of Croatia Was Created? In Grb and Zastava 1. Zagreb: HGDZ. [Google Scholar]

- Гавровски, Дарко. 2001. Новиот државен грб на Република Македонија.

- До средствата за јавно информирање. Светски македонски конгрес, December 29. 2000

- З. Д. 1992. Конечни предлози за државните симболи. Нова Македонија, June 5. [Google Scholar]

- Интервју—ДУИ. 2014. “Интервју—ДУИ ќе понуди свој предлог за грб.”. Република. Available online: http://www.utrinski.mk/?ItemID=18F027D26A9EDE4DAAEEA6D01B459189&commentID=630474&pLikeVote=0 (accessed on 16 March 2017).

- Лажна. 2014. Лажна политичка пропаганда на бугарскиот “Телеграф”-Ексклузивно за Република, Стојан Антонов, претседател на бугарските хералдичари. Република. December 8. Available online: http://republika.mk/356404 (accessed on 5 January 2017).

- Панов, Игор. 2001. Расположение има, но погрешен е тајмингот. Дневник, August. [Google Scholar]

- Петров, Тодор. 1992. Предлог за донесување Закон за грб, знаме и химна на Република Македонија со Предлог-закон, June 1, (ДАРМ, Фонд 1304).

- Чангова, Катица. 1991. Корени и визии. Нова Македонија, December 14. [Google Scholar]

- Шаровски, Стеван. 2001. Петокраката не е само симбол на комунизмот. Старт, February 2, # 106. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This symbol is often credited as the Arms of Serbia, with no critical observation, since the arms of Serbia is Gules a double-headed eagle Argent, being quite different from the heraldic coat of arms. |

| 2 | For a long time, the first Illyrian Armorial was attributed to don Pedro Ohmucevic(died in 1599). The armorial contained some 160 family arms, including arms of his close friends and relatives (Korenic-Neoric, Taskovic etc.), in order to prove his noble ancestry and to obtain noble status in Spain, where he reached the status of vice admiral. The armorial contained both real and imaginary arms, as well as dozens of arms attributed to the nobility during the time of medieval Serbian Czar Dushan the Great (died in 1346). It also contains “Land” arms of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Serbia. Those are called “Land arms” (from slavic Zemja/zemlja meaning land) to distinguish from territorial arms, because the armiger is not a real administrative entity, but simply an undefined land (see Ćosić 2015). |

| 3 | First Stematographia by Vitezovic was published in Vienna in 1701. It was in Latin, containing 56 territorial arms of “all Slavic” lands from the Adriatic to the Baltic Sea, including the 9 Illyrian Land arms. The same book, translated into Church Slavonic by Hristofor Zefarovic, was published in Vienna in 1741. This book, and its 4 editions, was the only heraldic printed work available for Slavic-speaking peoples in the Balkans for centuries. |

| 4 | The armorial achievement of the Principality of Serbia was adopted in 1835, and was taken from the Stematographia of Vitezovic of 1701. It was Stojan Novakovic’s idea to establish a symbolic connection, showing continuity with the medieval Serbian state of Tzar Dushan, in the arms of the new Kingdom of Serbia. In 1882, the two-headed white eagle from the coat of arms of the noble family of Nemanjic from the Illyrian armorials was added and, also, the arms of the Principality of Serbia were placed on the eagle’s chest. The design is by Austrian Ernst Khral, and was later reintroduced in 2009. |

| 5 | The armorial achievement of Bulgaria in 1879 is also taken from Stematographia. In 1997, the design of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Bulgaria, from 1927 to 1946, was restored, with minimal changes to the crown, in an interpretation by Kiril Gogov and Georgi Chapkanov. |

| 6 | The coat of arms and flag of Albania are derived from the arms of the Kastrioti family from the Illyrian armorial. The flag (actually a heraldic banner) was adopted on 28 November 1912, following a proposal by Ismail Qamil. In 1992, the Republic of Albania restored the small arms of 1930 and, in 1998, the Skanderbeg golden helmet was placed in the chief of the shield. |

| 7 | In 1822, the emblem depicted the goddess Athena with an owl. In 1828, there was a phoenix, born again from the ashes, with a cross above and the date 1821 below. The latter was also used from 1967 to 1975. Between these periods a coat of arms—Azure a cross Argent—was used, with additional dynastic elements from the coats of arms of the ruling dynastieson a large inescutcheon with up to two layers of inner inescutcheons. On 7 June 1975, the outer elements of the achievement (supporters, compartment, mantle, and crown)were replaced by a wreath of laurel leaves. This design was by Costas Gramatopoulos. |

| 8 | This new symbol always relies on “old” or universal symbols but, as a symbolic composition, it appears for the first time in the public arena. |

| 9 | After the Second World War, a public competition was held to choose a new symbol of the state, one which was to break with the old symbols associated with fascism. A condition of the public competition was that the design of the new emblem should have the Italian star, an old symbol of Italy, without political and “historical” connotations. The emblem, with a socialist connotation, was accepted in May 1948. The design is by Paolo Paschetto. |

| 10 | The case of the Republic of Slovenia is different. In May 1991, Slovenia decided to obtain its emblem through a public competition. Slovenia, then part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Serbs, (SCS) had a real coat of arms which was represented on the marshalled arms of the Kingdom: Azure, three mullets of six points Argent over crescent Or. Slovenia also has a “land” coat of arms—the traditional coat of arms of Kranjska, with an eagle. The new emblem of Slovenia is, in fact, an heraldic representation of the socialist arms by removing the ideological elements and inserting new charges—a triple mountain with waves in the base on a shield, and with the addition of three stars from the coat of arms used within the Kingdom of the SCS, and without elements of the “Land Arms”. The coat of arms designed by Marko Pochachnik was adopted on June 2nd, the day before the independence vote. This example is the so-called “Slovenian solution”, where the artist edits the design of already-present elements. |

| 11 | In Bosnia and Herzegovina, when the two constituents failed to agree on the state symbols, the High International Representative suggested a blue design with a yellow triangle (representing the simplified contour of the territory of Bosna and Hercegovina), as well as nine amulets of Argent, following the example of the Cyprus flag (the use of the contours of the country) as a national symbol. |

| 12 | UnitedNation Mission in Kosovo. |

| 13 | Albanians, Serbs, Turks, Gorani, Roma, and Bosniaks. |

| 14 | According to the description of the Law, a mountain contour is in the field of the People’s Republic of Macedonia’s arms and, at the end, it mentions the rising sun. |

| 15 | The Macedonian term “грб” (grb) is translated into English as “coat of arms”. Although the word has heraldic connotation, it is used to denote an official emblem regardless of its heraldicity. |

| 16 | With the Declaration of Sovereignty of 25 January 1991, Article 3 states: “a new Constitution will be adopted by which, among other things, the social order and the future symbols of the state of Macedonia will be determined”. The Constitution of 17 November 1991 in Article 5 determines the state symbols to be determined by Law, and the Constitutional Law prescribes that Law to be adopted no later than six months. |

| 17 | Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization—People’s Party. |

| 18 | All reconstruction of the proposals by Jovan Jonovski. |

| 19 | The first twoline read: Today over Macedonia, new sun of freedom rises. |

| 20 | Although present in the wider region, the sixteen-rayed sun, later named Sun of Kutlesh/Star of Vergina, only became popular after the discovery of the Royal Tombs in Vergina (Slavic name-Kutlesh) in 1977. |

| 21 | The Province of Macedonia in Greece (a name used only since 1987, and previously called North Greece) started using a blue flag with a golden or silver sixteen-rayed sun as a symbol of “Greek Macedonia”. Even though, heraldically, this is not a problem, since both flags have different colors, the Greek government viewed the Republic of Macedonia’s use of this symbol as stealing one of its symbols. |

| 22 | Stojan Andov, President of the Constitutional Commission, later Speaker of the Assembly, in a private conversation with the author on 23 December 2017. |

| 23 | In the “Start” in 2001, illustrations for “Slovenian solutions” on the arms of the Republic of Macedonia by Niko Tozi and Aleksov are shown, without any additional information (Шаровски 2001). |

| 24 | Todor Petrov, in his memories, mentions 1993, while Miroslav Grchev, in his book, mentions 1994. No further information has been released, so far, that can confirm one date or the other. |

| 25 | Talk with Todor Petrov, unknown date. |

| 26 | The Law on the Macedonian Orthodox Church, the Law on the World Macedonian Congress, the Law on the Proclamation of a Part of the Shar Planina for a National Park, the adoption of a Declaration on the Name of Macedonia, the adoption of a Declaration on the Status and Rights of the Macedonians with Islamic Religion, and the adoption of a Declaration the position and rights of the Goranians, with a proposal of the Declaration. |

| 27 | http://vecer.mk/makedonija/petokrakata-i-lavot-zaedno-vo-sobranie. Visited 26 June2017. |

| 28 | In May 2014, Jonovski was invited to the government to present the possibilities for finally resolving the proposal for the coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia. At that moment, the exact design of the arms was not determined, except that it should be sought between the historical coats of arms with Or, a lion Gules. |

| 29 | In accordance with the civic heraldic system of the Macedonian Heraldry Society where, according to the hierarchy of the territorial units, three towers are for a city, four for the capital, and five for the state. |

| 30 | Which requiresa simple majority of the ethnic Albanian MPs. |

| 31 | Jonovski (2009, 2013). |

| 32 | http://forum.kajgana.com/threads/Grabovi-na-Makedonija-Makedonska-Hereldika.26652/. Visit 27 July 1992. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).