Appendix A. IAP Collections

The following is an annotated bibliography of the current record collections contained in the

Immigrant Ancestors Project. These collection descriptions come directly from those included on the website,

http://immigrants.byu.edu.

Appendix A.1. Passenger Lists

• “Embarquements”

A French record of immigrants leaving from Bordeaux between 1713 and 1787, this collection contains attestations of religion which were required of all travel applicants before being allowed to board the vessel. At each departure, a list containing information about passengers’ identity and destination was created. Documents included in this collection are identity and Catholic certificates, as well as passport submissions concerning the departed passengers from Bordeaux.

• “Patrick Henderson & Co. Passenger Lists 1871–1880”

This collection includes information about passengers on voyage from Scotland to New Zealand between September 1871 and October 1880. The transcriptions were extracted from photographs of the original manuscripts housed at the Glasgow City Archives.

• “Passenger lists from British Isles to New Zealand, 1871–1888”

These passenger lists cover much of the period from November 1871 to September 1888, though gaps in the information exist. The original documents are on microfilm in the Family History Library collection in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States.

• “Agincourt to Australia”

The entries in this source originated from the passenger list for the Agincourt, which arrived in Sydney 6 October 1848. This collection is accompanied by an insert documenting passengers of vessels that sailed to South Africa in 1820.

• “Batavia: Ship’s Lists 1810–1820”

These lists include prisoners of war, officers, and ship logs. Most of these records include the first and last name of the passenger, the person’s station, remarks (often including death dates), and sometimes the person’s departure and arrival dates.

• “Ships’ Lists found in the East India Company Ships’ Journals 1605–1856”

This collection contains transcriptions extracted from original manuscripts housed at the British Library. After each East India Company voyage, a ship’s commander would deliver a copy of his ship’s journal to the East India House. In the 3,822 journals that are held at the British Library, ships’ lists of the crew, passengers, prisoners, soldiers, and other travelers are often included. The original manuscripts include the ship’s name, date and place of departure and arrival, first and last name, relationships, occupations, purpose aboard, and possibly additional remarks such as birth, death, and age. The ships’ lists are the only part of a ship’s journal extracted. The actual journal may contain more genealogical information.

• “New Zealand Co Cabin Passengers 1839–1850”

This register of cabin passengers includes information about the ship, the captain, the date sailed, and the names and descriptions of passengers, including gender, a residence, and where they sailed to. Some entries include where the individuals originated.

• Miscellaneous passenger lists

Other collections containing passenger lists include “Dutch Immigrants in United States Ship Passenger Manifests, 1820–1880”; “Vessels to South Africa”; and “Passenger Lists of Steam Packets to the Mediterranean Area, 1831–1834.”

Appendix A.2. Emigration Approvals

• “Permisos de Emigración por Municipios”

This is a collection of emigration permits provided at a municipal level. The permits include information about the emigrant and his or her family. For a person to be permitted to emigrate, a relative had to appear before a government representative and formally give permission.

• “Expedientes de emigración”

These records include the residence of the potential emigrant, including his or her parish. Birth dates are sometimes included.

• Miscellaneous emigration approvals

Other emigration approvals include the Spanish collection “Permisos de Embarque,” as well as the French collections “Bayonne Immigrant Records” and “Haut-Rhin Passeports d’Immigration 1817–1866.”

Appendix A.3. Passport Files

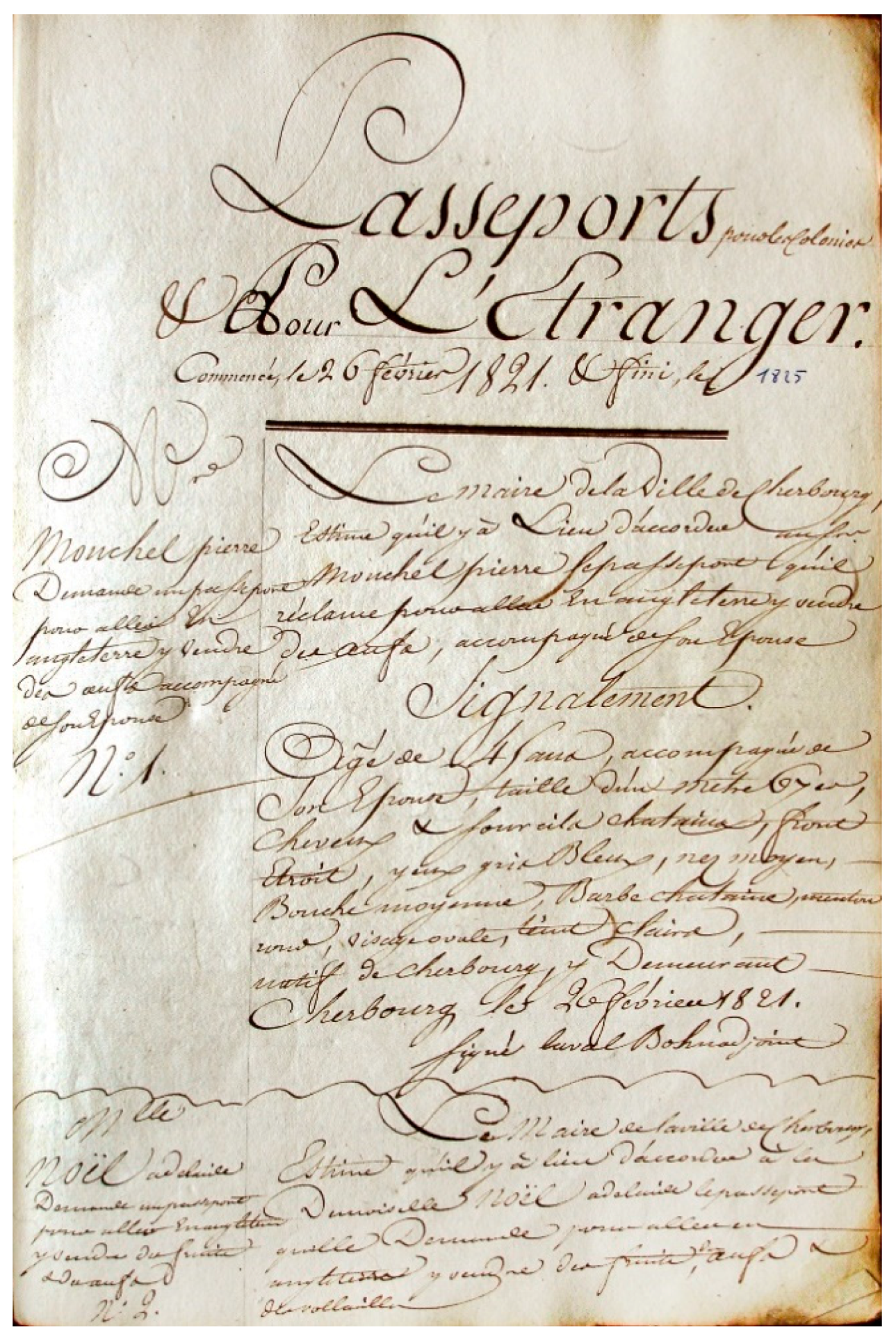

• “Passeports de l’Intérieur”

A collection of passports from 1844 to 1845 that allowed people to travel throughout France. Most, if not all, come from Dunkerque, a commune in the Nord department (in the far north of France).

• “Passeports” (from Bordeaux, France)

Contains passports delivered in Gironde, France, between 1800 and 1890. These records contain a physical description of the emigrant as well as the intended, international destination.

• “Governo Civil” (from Coimbra, Portugal)

This collection includes passport requests from 1835 to 1929. The index is created from entries of varied lengths, some of which are a single page and others of which contain 10 or even 30 pages. Most of the entries provide personal information about the individual applying to emigrate, as well as information about any accompanying individuals.

• “Torre de Tombo”

A collection of passport requests from 1752 to 1848. Each request is typically 3–5 pages long and contains information about the applying emigrant as well as accompanying individuals. The potential emigrant’s record number is also included.

• “Torino Passport Request 1903–1905”

This is a collection of documentation required to obtain a passport. Due to the great number of emigrants and the different locations in which the documents were issued, their format and content may vary. This collection covers the years 1903–1905.

• “Gobierno Civil, Registros de Pasaportes”

An index of emigration passport requests from 1824 to 1856 (with some missing years). The majority of the entries are short, as at least four entries are listed on each page of the original documents. In each entry is found information about the applicant and any accompanying individuals.

• Miscellaneous passport files

Other passport files for which indexes exist on the IAP website are the French collections “Registres d’inscriptions des passeports délivrés en Charente-Maritime,” “Haute-Marne: Passeports à l’Étranger,” “Loire-Atlantique Passeports,” “Passeports à l’Étranger,” “Demandes de passeports,” and “Passeports d’étranger de la Sarthe”; the Spanish collections “Gobierno Civil, Expedientes de Solicitudes de Pasaporte,” “Solicitudes de Pasaportes,” “Vegadeo Solicitudes de Pasaportes,” “España, Provincia de Cádiz, pasaportes, 1810–1866,” and “Solicitudes de Pasaporte”; the Italian collections “Napoli Passport Requests 1888–1901” and “Prefecture of Genoa 1858–1872”; the English collection “Passport Applications 1815–1922”; and the Portuguese collection “Coimbra Governo Civil.”

Appendix A.4. Arrival Lists

• “Arrival Records”

An index of images from the Consulado Geral de Portugal in Hawaii. These represent the passport registers that contain data regarding those who arrived in Hawaii from 1878 through 1913. The books are rather consistent in form and layout; most of them contain about 35 persons per page. Most entries provide personal information about the individual arriving to Honolulu, Hawaii, and some information about any accompanying individuals.

• “German Immigrants, List of Passengers Bound from Bremen to New York, 1847–1871”

This information is derived from passenger lists of immigrants who traveled from Bremen to New York City between the years 1847 to 1871. The data comes directly from the publication German Immigrants: Lists of Passengers Bound from Bremen to New York (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1985–1993). The authors, Gary Zimmerman and Marion Wolfert, extracted the facts contained in the IAP database from microfilms of original or U.S. State Department copies available at the National Archives and its branches. Wolfert and Zimmerman included only those passenger lists in which a place of residence was given. As a result, this compilation includes about 25% of passenger lists available for the years 1847–1871. Copies of the passenger lists can be browsed on FamilySearch.org and searched on Ancestry.com. Sometimes additional information not found here may be found on the original passenger list.

• Miscellaneous arrival lists

Other arrival lists included in the IAP database are in “Collection des Personnes Arrivées à Jersey” and “Einwanderung aus Polen, Einzelne Einbürgerungsanträge.”

Appendix A.5. Emigration Records

• “Landverhuizerslijsten—Groningen” and “Landverhuizerslijsten—Groningen Digital”

Indexes created from official lists of emigrants in the Netherlands for the years 1848–1877. Provinces listed the number of emigrants per municipality in yearly reports and sent these to the Hague. It was not until 1879 that the province of Groningen recorded this data in separate Landverhuizerslijsten instead of in the provincial census. These lists include place of residence, given name, last name, gender, age, occupation, religion, class according to income, reason for departure, and destination.

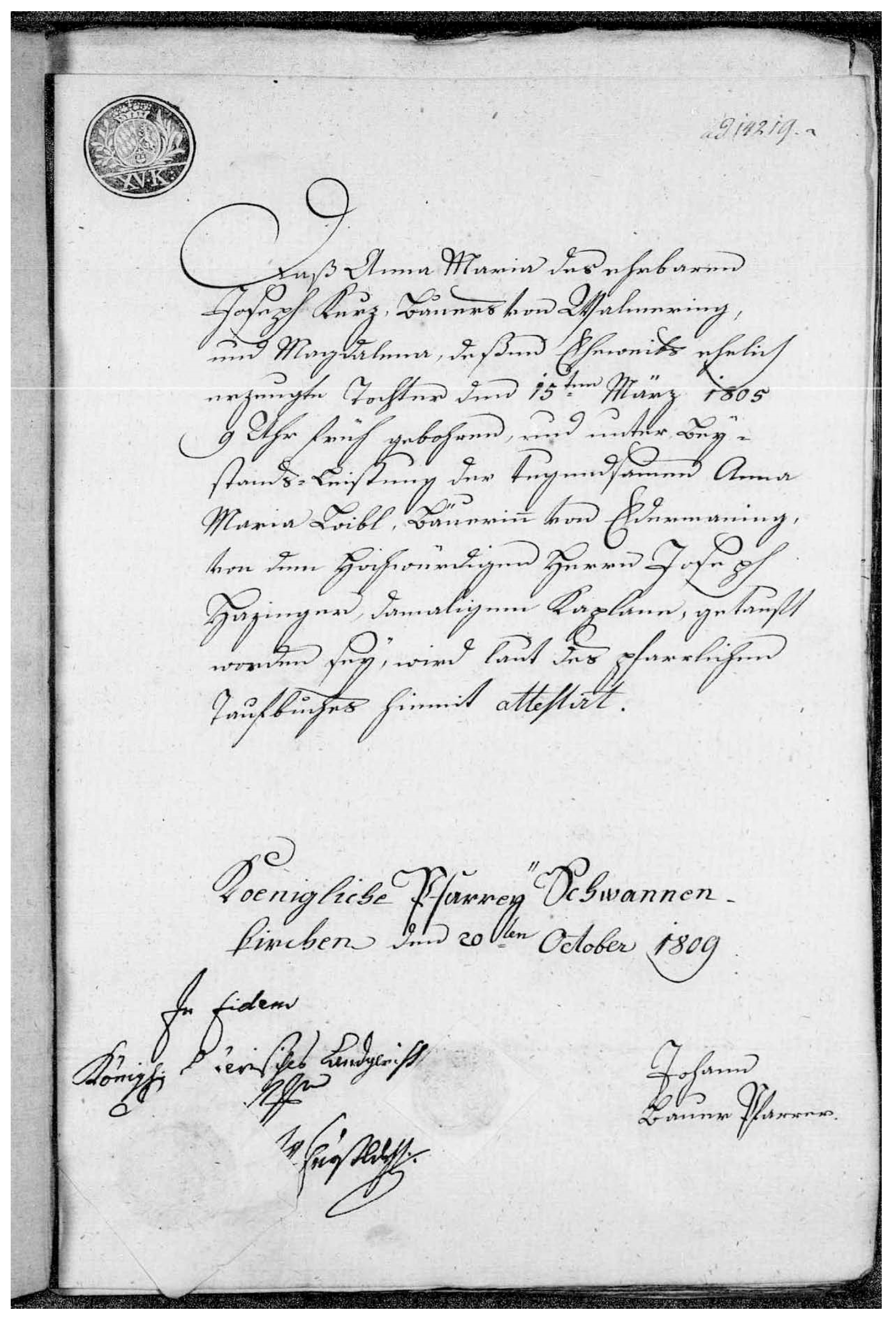

• “Germany, Bavaria, Fürth, Emigration and City Directories, 1805–1913”

An index of emigration records that were created in Fürth, Germany. Images can be viewed online at FamilySearch. In the collection on FamilySearch, click on “Auswanderungsakten” and then find the image based on the image source code.

• “Auswanderung nach Nordamerika Namens-Kartei”

A handwritten, alphabetical name-card index of emigrations to North America.

• “Namenskartei aus den Bremer Schiffslisten 1904–1914”

A name index from the Bremen, Germany, ships’ passenger lists for 1907–1908 and 1913–1914. This is a collection of index cards for German emigrants listed on Bremen passenger lists and arranged alphabetically by province, then by surname. The index includes passenger name, gender, age, marital status, occupation, place of last residence, departure date, ship name, shipping company (i.e., ticketing agency), destination, and nationality. This project was done in cooperation with FamilySearch Indexing and Die Maus, a genealogical society in Bremen, Germany.

• “Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo”

The original documents of this collection are copies of the official bulletins of the province of Oviedo (now called Asturias). It is divided into annual volumes. Between 1858 and 1862, the government of the province of Oviedo published the names of all persons who intended to emigrate, allowing any pending issues to be resolved before departure. The name lists were sent to the provincial government by the mayors of each population. Depending on the years, these lists contain given names, surnames, place of birth, place of residence, place of destination, age, and names of the parents. The number of individuals per list varies from 1 to about 80 individuals.

• “Westminster Child Migrants 1874–1928”

This collection contains emigration information (name, age, date, home parish—union or branch—and where placed) of poor Catholic children who emigrated from the Westminster Diocese to Canada between 1874 and 1928. The Canadian Catholic Emigration Committee was formed in 1874 to make provision for poor Catholic children of this diocese to travel to Canada. In 1902, the committee’s name was changed to the Catholic Emigration Society, and in 1903, the name was changed to the Catholic Emigration Association.

• “Blean Union Poor Law Children”

Records describing the emigration of orphan, deserted, or destitute children in the Blean Union of Kent County, England. The information regarding these children was found in emigration agreements of the Guardians of the Poor Union. These agreements were a standard procedure, which meant that they followed a specific form. Typically, they included a schedule containing names, ages, and occupations of the emigrants, as well as details of the voyage, such as food rations each individual would receive.

• “Castlecomer Poor Law Union Assisted Emigrants 1847–1853”

These registers were recorded by year and township. Names were recorded, and information about how much money each parish gave to the families to emigrate was listed. The destination of most of the individuals was Upper Canada.

• “Vestry Book Glemsford emigration 1833–1839”

This collection concerns the 1833 issue of raising money to assist and support the families of expatriates in their journey to join their husbands and fathers. It was unanimously agreed to borrow £70 to pay for the maintenance and conveyance of Thomas Pettit’s wife and eight children to their father in New York. At a vestry meeting, it was also considered whether to send James Parman’s family to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania, in Australia) at the expense of the parish.

• “Suffolk Parish Assisted Emigration”

The records extracted for this collection come from various files found in the Assisted Emigration files in the Ipswich Suffolk Record office. Guardians of the poor in the parish of Suffolk raised money to help individuals emigrate from the 1830s to the 1850s. Entries include the name and location of the potential migrant as well as the date of the petition and other genealogical data.

• “Emigrants from Scotland to America, 1774–1775”

These transcriptions were taken from Emigrants from Scotland to America 1774–1775 and copied from a loose bundle of treasury papers in the Public Record Office in London, England.

• “St. Helena to England and Other Locations”

An index of passengers traveling from St. Helena to England between 1807 and 1812. The list includes passengers passing through St. Helena from India and China on their way to England.

• “Cyclopedia of New Zealand”

Extractions from the Cyclopedia of New Zealand. The index includes name, birth date and place, date of emigration, occupation, port of arrival, ship, year of arrival, and volume number.

• “Convict’s Families 1848–1873”

This is a register of applications for passages to the colonies for convicts’ families. These particular documents are registers of families from the British Isles who applied to immigrate to Australian colonies in order to join a family member who was exiled as a convict. Although only personal and emigration information was extracted, some documents also contain additional information, such as notes about letters of referral and specific residential addresses.

• “Australia Forms 1831–1833”

The original document from which this information was extracted is a collection called “Colonial Office Records: Australia. Registers of forms and circulars sent to intending emigrants 1831–1833.” The collection is comprised of books from The National Archives of England, Wales, and the United Kingdom. The books list names of intending emigrants to Australia involved in the transaction of emigration forms. The collection does not specify whether the individual actually emigrated.

• “Suffolk Poor Law Collection: Hoxne 437. 1836”

This index gives a list of poor individuals and families in Wingfield, Stradbroke, Fressingfield, and Horham who received parish assistance to emigrate. Name, age, gender, marital status, occupation, amount of parish relief received during the last year, place of residence, place of immigration, and remarks are included.

• “Weekly Emigration Returns 1773–1776”

The original document this information was extracted from is a collection of treasury papers containing information about individuals who requested emigration between 1773 and 1776. For each head of household, the documents list the name, date, age, children’s age (or age range), former residence (i.e., estate), destination (port and/or place), occupation, parish, county, purpose for emigrating, and port of departure. For some individuals, there are multiple pages of information. Background information is included for groups traveling together.

• “Irish to Canada 1824–1825”

This index is based on information about Cowrie immigrants, Irish immigrants, and Canadian immigrants as found in the book collection. The focus is on emigrants from Ireland who are traveling to Colonel Bay, Canada. The record contains the signature of the head of household immigrating to Canada. It gives the county, parish, and town (or village) of the family’s origin. The record indicates how many males and females and total members of the family are emigrating along with the head of household. Following each family’s information are descriptions about the family, which may include who they were meeting in Canada.

• “Halifax Orphans to Canada”

On 7 May 1896, the guardians of the Halifax Poor Union decided to recommend four orphan children to immigrate to Canada through the Liverpool Children Protection Society. The children were set to sail from Liverpool on May 28; however, they needed to be cleared by a medical officer before emigrating. These records include the first and last name of the child, as well as his or her age, departure date, and medical health.

• Miscellaneous emigration records

Other emigration records in the IAP database are “Landverhuizerslijsten–Gelderland,” “Landverhuizerslijsten–Zeeland,” “Napoli Illegal Emigration,” “Zentralkartei der Deutschen Wanderung, 1750–1943,” “Auswandererkartei mit Familienangehörigen, 1750–1943,” “Expedientes de Prófugos,“ “Expedientes de Embarque,“ “Oñate - Permisos de Embarque,“ “Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Cantabria,“ “Comendaticias de Embarque,” “Emigración a América,” “Emigración navarra del Valle de Baztán a América en el siglo XIX,” “Patagonia Relatives 1875,“ “Norfolk Overseers’ Accounts 1826–1835,“ and “Wiltshire Emigration Association Register of Emigrants.”

Appendix A.6. Naturalizations

• Miscellaneous naturalizations

Naturalization records indexed in the IAP database include the German collections “Einbürgerung ehemaliger Deutscher mit jetziger Niederlassung im Inland,” “Einbürgerung von Kriegsgefangenen (Einzelsachen),” “Einzelverzeichnisse der von Preußen beabsichtigen Einbürgerungen von Kriegsfreiwilligen usw,” and “Einzelverzeichnisse über Einbürgerungen in Preußen.”

Appendix A.7. Immigration Records

• “Speculum Gregisor Croydon 1844”

This index is based on an account of all the inhabitants of the parish of Croydon in the county of Cambridgeshire from 1 January 1843 through 1844. The information is contained in a book written by the parish rector about the inhabitants of his parish.

• Miscellaneous immigration records

Other immigration records in the IAP database are the collections “Certificación de Residencia,” “Extranjeros Residentes en Málaga, 1863,” and “Mormon Immigrants.”

Appendix A.8. Emigration Letters

• “Wood Family Letters 1853–1859”

This index is based on two letters from John and Hannah Wood of Sykehouse written to a brother, Wheatley Wood, of Morgan County, Illinois, United States, dated 30 January 1853 and 7 August 1859. The original letters speak of the death of a sister and give information regarding their stock, their crops, produce prices, and the curse of slavery in America. Hannah writes about family squabbles, financial problems, neighbors, etc.

• “Letters from James Horrocks”

This index is taken from My Dear Parents: An Englishman’s letters home from the American Civil War by James Horrocks (edited by A.S. Lewis; London: Victor Gollancz LTD, 1982). This is a published book of the transcription of James’s letters from America back to his family in England.

• “McClure Family Letters 1817–1877”

This index is based on 22 letters and documents of the McClure family.

• “McCleland Family Letters to NZ 1840–1870”

This index is from eighteen documents, including letters from the McCleland family in Londonderry, Ireland, to their daughter, Ann McCleland, an immigrant to New Zealand. Ann later married Yohan August in Wellington. Ann and John August were later in Chile, where two daughters were baptized. The family subsequently sailed from Chile via Ecuador to Liverpool. Seven children of Anne and John A. Heldt were baptized in Londonderry. In 1859, John A. Heldt and his family sailed from Liverpool to Auckland, New Zealand.

• “Hawgood Family Letters”

Names were extracted from letters of the Hawgood family, who emigrated from Pembroke Dock to the United States between 1856 and 1870. The letters describe the family in America and family and friends in Wales.

• Miscellaneous emigration letters

Other emigration letter collections are the “Irish Emigrant Letters 1842–1910” and “Convicts & Emigrant Letters 1840–46.”

Appendix A.9. Convict Records

• “Bath Convict Hulk to New South Wales 1848–1855”

This record contains information about the convicts aboard the hulk, a few of whom were eventually transported to New South Wales. The record lists each convict’s name, age, conviction, family (marital status and number of children), literacy level, occupation, crime committed (including date and location), the sentence, when and where the convict was received, when and to where the convict was transported, and additional notes.

• “Quarterly Returns of Prisoners in Convict Hulks”

This collection consists of sworn lists of convicts on board the convict hulks (until 1861) and in the convict prisons (from 1848). Criminal lunatic asylums were included starting in 1862. Some returns for hulks at Bermuda were included. The records include the first and last name, age, offense, sentence, bodily state, behaviors, conviction date and place, and other remarks about each convict.

• “Dolphin/Cumberland Descriptions 1819–1834”

This index contains names of the convicts for the ship Dolphin and includes birth locations and physical characteristics for each convict. Remarks for the convicts often contain descriptions of tattoos, injuries, and other unusual physical characteristics.

• “Convict Tickets of Leave”

This information was extracted from a register of 19th-century British convict passengers who were transported to New South Wales (in Australia) between 1820 and 1840. The convicts came from England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and occasionally other British colonies. A prisoner’s sentence was typically for seven years, fourteen years, or life. The register book was created in New South Wales and sent to the governor, Sir George Gipps, in 1843. It included a statement of the prisoners’ original sentences and of the circumstances surrounding them.

• “Mutiny of convicts under transportation”

This collection covers November 1838 to May 1841. Explanations regarding the convicts on board the Brig Catherine are included. Original manuscripts often include the date the letter was written, the name of the person writing the letter, and the residence of the person writing the letter. Lists of convicts included in these letters consist of all or some of the following: the convict’s name, gender, letter number, age, occupation, committed crime, sentence (including the date of the sentence), marital status, height, complexion, hair color, eye color, particular marks, and country of origin.

• “Calendars of Prisoners”

This is a collection of Warwickshire quarter sessions’ calendars of prisoners for 1801–1850, held in the Warwickshire County Record Office in England. Individuals guilty of a capital offense or other serious crime were often sentenced to transportation to penal colonies. Sentencing did not automatically lead to transport, however, as the transport ships were often full and unable to take the criminals away as quickly as they were sentenced. During the interim (anywhere from a few weeks to years), the criminals served time either in gaols (jails) or on hulks (ships anchored in a harbor where the inmates were sentenced to hard labor). Due to the conditions of gaols and hulks, many inmates lost their lives before they were transported to the new colony.

• “Essex Indictment Books”

Entries often give the name, abode, and occupation of the defendant, as well as the offense, plea, verdict, and sentence (such as whipping, branding, a fine, imprisonment, transportation, removal to a higher court, respite to the following session, cessation of the process, or discharge).

• “Penitentiary Register of Prisoners, 1841–1844”

The original document from which this information was extracted is located at the Gloucester Record Office. The only names that are included are 230 people who were sentenced to be transported. Most of the records include the first and last name of the prisoner as well as the prisoner’s age, trial, sentence, crime, and occupation. Additional remarks may be listed.

• “Transportation Bonds”

This is a collection of court proceedings that contain data regarding persons who were convicted to be transported to America between 1759 and 1775. Convicts were tried at the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace in Bristol, England. The transportation sentences include name of convict, term of transportation, and trial date. Other information such as the felony committed and/or why they were convicted is also recorded in the originals, a copy of which may be ordered from the repository.

Appendix A.10. Orphan and Poor Folk Records

• “Hoxne Union Poor Law Ministry of Health 1838–1842”

Names of some guardians of the poor are given, though not many other individuals’ names are listed. On occasion, the record includes names of people who were thought to need financial help. For the years 1840 and 1841, additional questions were asked of those applying for financial relief, thus more names and ages were listed. Otherwise, the focus was on correspondence by year, dealing with property sales, poor rates, the workhouse, and other items relating to governing the poor, including the meeting dates of the union.

• “Consent to Expenditure Letters”

This information was extracted from a collection called “Consent to Expenditure Letters,” which is comprised of books from the National Archives of the United Kingdom, under the call number MH 64. The books contain letters from the local government and the Ministry of Health, authorizing the expenditure of funds for the emigration of poor individuals and families. The records list the names of individuals who were receiving assistance to emigrate from England. Each document contains the name of the poor law union or parish that authorized the expenditure of funds, the amount of money given, the date on which the funds were authorized, and the country to which the individuals were migrating.

Appendix A.11. Military Service Records

• “Royal Chelsea and Kilmainham Hospitals Pensioners H1 1834”

This collection includes regiment, name, date of admission, age, statement of service, rate per day, complaint or cause of discharge, description of the pensioner (height, hair, eyes, complexion, and occupation), and intended place of residence. Remarks about the pensioner are given as well. These lists are specifically for people stationed in Great Britain.

• “Examination of Invalid Soldiers”

This information is from a book listing invalid soldiers (most of whom were born in England) who were given permission to stay in particular colonies. It provides descriptions of the soldier, the amount of pension, and the soldier’s birthplace, regiment, and injuries. The original documents also contain information on years of service at each rank, which in some cases has not been extracted. The records vary depending on the year when they were created; the records cover 1817–1875 but include gaps.

• “Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de La Coruña”

The documents indexed in this collection contain lists of soldiers being sent out, as published in the Official Bulletin of the Province. “Austent” soldiers were registered in the Americas.

• Miscellaneous military service records

“Alphabetical List of Noncommissioned Officers, Privates, and Foreigners of the Woolwich Division of the Royal Marines for Limited Service, 1812” and “Bonds and Agreements: Overseas Servants 1801.”

Appendix A.12. Other Records

• “Regierung von Niederbayern Repertorium 168, FZ 2321–2335, Aus- und Einwanderungsakten”

This is a collection of emigration and immigration petitions, releases from citizenship, and supporting documentation. Records date primarily from the 19th century and are mostly in essay form (i.e., letters), though some are in table form. The records were created by the provincial administration of lower Bavaria and are kept at the Bavarian State Archives in Landshut. Microfilm images of the originals can be viewed at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States.

• “Consulado de España en Trieste (Italia): Matrículas de españoles”

These documents contain the personal information of the Spaniards residing in Trieste, Italy, enrolled in the years 1886 to 1917. Their respective places of origin and other particulars are included.

• “Expedientes Jurídicos” and “Expedientes de Cargos Municipales”

These collections contain some of the largest sets of documents within the municipalities of the province of Pontevedra, with abundant documentation.

• “Essex Estate/Fam Records”

This is a collection of estate and family records relating to Maldon and East and South East Essex. These records include an 1878 letter of attorney from Issac George Foster of Kelvedon, deeds from 1820 to 1834, and Stanford and Hughes family letters.

• “Essex Overseers Accounts”

This collection includes miscellaneous overseer accounts from the Essex County Record Office, including letters and property information records.

• “East India College Writers Petitions”

Applications of persons seeking admittance to the East India College located at Haileybury, an estate in Hertfordshire. Applicants who were accepted most likely immigrated to India for a period of time, but not all applicants were accepted. Documents include information about the parents, birth, and residence of the applicants.

• “New Zealand Company Correspondence 1841”

A book of correspondence of the New Zealand Company about why, when, and how emigrants could or did apply. Much of the book concerns logistics of and planning for emigration but does not contain names of individual emigrants.

• “Register of Vagrants Deported from the Port of Liverpool to Ireland, 1801–1835”

Records from the Royal Chelsea Hospital created by the War Office. They list invalid soldiers (most born in England) who were given permission to stay in specific colonies. Provided are the soldier’s description as well as his birthplace, regiment, injuries, and place of residence. This collection is known as “Admission book: pensions payable in the colonies” at The National Archives.

• “Fallecidos en el Extranjero”

This index contains information about people who were deceased abroad.

• “Antwerpen: Vreemdelingendossiers 1840–1930”

Index lists and the corresponding dossiers they are stored under in the city archive of Antwerp, Belgium. These lists were kept by the Antwerp (Belgium) City Police on foreign nationals residing in their city 1840–1930, though the collection may contain documents from a later period as well. Included in the index lists are given name, family name, birth date, residence, and nationality.

• Miscellaneous records

Other records contained in the IAP database are the following:

The English collections “Irish Emigrant Personal Accounts 1838–1901,” “Europeans residing at Madras,” “Register of Girls’ Friendly Society 1890–1921,” “Quarter Session Calendars, House of Correction, Preston. Change,” “Industrial School Children 1893–1895,” “Free Passage to New Zealand 1839–1842,” “Land and Emigration Commission: Certificates Numbers: 1–3360, 1836–1838: 386/149,” and “Original Certificates of Baptisms and Marriages of British Subjects Abroad” (i.e., expatriates).

The German collections “Spezialien in Bezug auf die Erwerbung und den Verlust des Indigenats,” “Fürsorgeverein für deutsche Rückwanderer in Berlin,” “Gesuche preußischer Untertanen um Erlaubnis zur Auswanderung ins Ausland überhaupt,” “Zentrale Sippenkartei, 1750–1943,” and “Kartei von Deutschen Jugendbund Chiles 1910–1935” (a record of expatriates).

The Spanish collections “Registros de Bajas,”“Listas Pasajeros y Tripulación” (about the passengers and crew), “Partida de nacimiento, certificado de naturalización Norteamericana y pasaporte Norteamericano,”“Rectificación al Padrón de Habitantes,” and “Padrones de Extranjeros” (a list of foreigners).