Abstract

Construction work is fundamentally hazardous. Traditional risk assessment tools (e.g., checklists and audits) are static in essence and hard to make evolve. In this paper, we demonstrate how to get experts dynamically in the loop thanks to machine learning. Namely, we discussed the design of a prototype risk assessment dashboard dedicated to fall accidents. The interactive graphical user interface allows professionals to generate construction scenarios and compare their evaluation of risks with that of the dashboard. The latter continuously learns from expert feedback. The proof-of-concept we present here shows that it is possible to capitalize on expert knowledge in a dynamic and user-friendly way. Thanks to its neural network architecture, not only does the dashboard learn from the experts, but professionals also learn from the dashboard.

1. Introduction

The construction sector is well known as one of the most hazardous workplaces worldwide, accounting for a significant proportion of workplace injuries and deaths annually. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that there are some 60,000 fatal accidents on construction sites worldwide each year, with more than 160 deaths every working day [1]. This is even more challenging, particularly due to the increasing complexity of construction work, accelerated urbanization, fragmented subcontracting, and relatively limited implementation of sophisticated digital safety systems, with a tendency for addressing safety in a reactive mode rather than being proactive [2]. Not only do these accidents have a human cost, but they also lead to significant economic damage in terms of medical costs, compensation requests, lawsuits, and losses resulting from project delays [3]. The risk profile of construction work is multifaceted, with a broad range of risks including but not limited to falls from height, struck-by, electrocution, machinery-related accidents, and exposure to hazardous substances, and all these categories of accidents are caused by the synergistic effects of interacting with multiple risk factors [4,5].

While the development of construction safety has continued, accidents and losses still occur. This implies that other risk assessment methods, based on static checklists and site inspection reports, have room for improvement, as they may not fully capture the dynamic aspects of construction environments [6]. Such traditional methods may be limited in providing insights rapidly regarding operational conditions at the site [7]. Recent studies have increasingly relied on digital technologies to enhance safety management, including Building Information Modeling (BIM), Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based systems [8,9,10]. Such tools have the potential to enhance hazard recognition, provide monitoring in real time, and support predictive safety modeling [11,12,13]. Machine learning (ML) methods such as neural networks, decision trees, and support vector machines are effective in capturing non-linear patterns between site features and accident potential [14,15]. Moreover, recent work has examined the use of computer vision for the detection of unsafe behaviors and the magnitude of prospective risk with reference to past safety data [16,17]. On the other hand, many of these models are ‘black boxes’, which may limit their interpretability and adaptability. Hence, there is an opportunity to leverage the domain expertise of safety managers and engineers [18]. One key area for further exploration is the establishment of integrated frameworks that bring together the computational power of machine learning with the transparency of fuzzy linguistic mapping and the ability to absorb context that comes from human feedback [19].

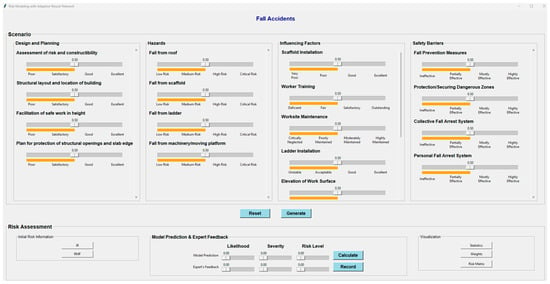

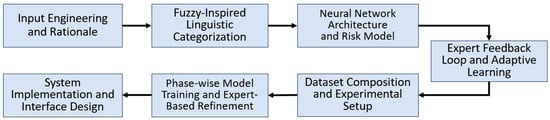

Despite the growing number of studies exploring machine learning for construction safety, several important avenues remain largely untrodden [20]. While machine learning models excel at discerning patterns within data, they typically struggle to assimilate specialist feedback unless systematically retrained. However, many analyses center on operational or real-time hazard states (e.g., sensor readings, weather, site layout), often neglecting the preventive potential held within early design choices like structural configuration or slab edge shielding [21]. Furthermore, when different rule-based techniques are applied, studies do not exhibit results in a form aligned with practitioners’ understanding of knowledge capitalization [22]. These voids imply a need for a hybrid system fusing the forecasting capacity of neural networks with the interpretability of fuzzy linguistic mapping and adaptability to expert feedback [23]. To bridge these gaps, this study pulls off a human-in-the-loop approach for fall-oriented risk estimation methodology, which utilizes neural network-based prediction and expert input for further learning and improving the model. A user interface is designed to enable field experts to inspect predicted risk levels, validate or correct outputs of the system, and retrain the model with a feedback mechanism. The schematic diagram of the proposed model and the graphical user interface (GUI) of the system are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Both figures attempt to capture the main elements of the proposed framework by combining computational intelligence with human expertise for proactive construction hazard management. Figure 1 represents the hybrid neural network framework and its retraining loop based on feedback. However, Figure 2 illustrates the interactive GUI where safety practitioners can see the risks visually, confirm the predicted risks, and refine the model instantaneously, thereby linking advanced AI techniques with practical knowledge capitalization.

Figure 1.

Proposed schematic diagram for neural network training architecture with a human-in-the-loop feedback mechanism.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the graphical user interface (GUI) of the construction fall risk assessment tool, demonstrating the systemic evaluation process.

The goal of this study is to develop a hybrid, interpretable, and adaptable risk assessment structure that joins neural network-based prediction, fuzzy linguistic mapping, and an expert-in-the-loop feedback mechanism. The framework is intended to support safety administrators, engineers, and planners in making informed judgments during both the planning and operational phases of construction ventures. The key contribution of this study is threefold:

- Proposing a conceptual framework to foster a tool for comprehensively addressing accident risks from planning through execution.

- Developing an adaptive hybrid model that couples a regression-based neural network with a fuzzy linguistic mapping-based interpretation layer and a human-in-the-loop feedback mechanism

- Integrating an interactive graphical user interface (GUI) that enables domain experts to validate and direct model predictions through structured feedback, allowing for continuous system improvement over time.

Briefly, the paper proposes a pragmatic answer to the assessment of fall risk by employing machine capability with human expertise and site-specific needs. The system the paper proposes operates on both the technical and organizational aspects of construction safety, contributing one step further toward continually improving safe working practices where construction hazards persist. Hence, Section 2 provides a context review, including the methods explored by different researchers for risk assessment of construction safety, and describes the research gaps identified and which encouraged this research work to proceed. Section 3 depicts the proposed methodology in a detailed manner, and Section 4 portrays the results and evaluation of the developed system performance with fall hazard scenarios as a representative use case. Section 5 discusses the findings from methodological, practical, and theoretical perspectives. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary of the main contributions of this paper with an overview of future research directions.

2. Background

A multitude of accidents, ranging from falls to electrocutions to being caught or struck, continue threatening worker health and disrupting project timelines [24]. Rarely is a single cause to blame; instead, numerous interacting risk factors usually are at play, such as deficient planning, unpredictable environments, insufficient preparation, improper equipment handling, and communication breakdowns [25]. While safety guidelines and codes exist in many locales, inconsistent enforcement and the absence of proactive risk identification are common. Traditional construction safety risk assessments heavily rely on manual processes, such as Job Hazard Analysis (JHA), periodic inspections, checklists, and expert intuition [26]. However, these fundamental approaches have restrictions in dynamically changing construction surroundings. They consume much time, depend greatly on subjective human judgment, and often fail to detect emerging dangers in real time [27]. Conventional safety systems typically are reactive, addressing risks only after manifestation instead of anticipating them in advance. Moreover, static safety protocols and checklist-based evaluations lack the flexibility required to oversee high-risk activities in complex construction projects where site conditions, workforce behaviors, and external environmental factors rapidly change.

For instance, falls from certain heights are still one of the leading causes of death in construction and continue to be a source of repeated concern. Falls are the only hazard that has been in OSHA’s “Fatal Four” every year since 2003, with fatalities totaling about one-third of all construction deaths [28]. These accidents mostly happen from scaffolds, ladders, or roofs, as well as unprotected edges, and are usually due to a lack of fall protection systems being used, poor training, or inadequate warning of hazards. On a global scale, there are similar trends with falls as one of the major contributors to fatal and serious injuries in construction. To deal with this ongoing challenge, more proactive safety management strategies informed by data are needed that shift away from reactive audits and move instead of predictive interventions. As such, the current work is rooted in the development and pilot of an adaptive, expert-in-the-loop framework for predicting risks specifically related to fall-related risks, to show both practical and methodological promise.

The restrictions of conventional ways have led to amplified attention to data-driven techniques and synthetic knowledge for hazard risk prediction. Over the past decade, a developing mass of research has displayed the use of machine learning to model and foresee safety dangers using accident data, sensor feeds, and site activity logs. For example, Erkal et al. found that multiple-layer perceptrons exceed baseline models of serious injury or fatality exposure and routine site conditions, typically in the presence of nonlinearities in the data [29]. Meanwhile, methods based on Random Forests incorporated with model-agnostic interpretable tools such as Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) delivered both high prediction accuracy and insight into the site-specific contributors to fatalities, marking a type of process template to enable scalable, transparent, and data-driven safety management [30]. Furthermore, ensemble designs combining both traditional forms of modeling and deep model architectures, such as XGBoost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and multiple-layer perceptron, improved accident type and severity classification, although the equitable representation of minority classes in the outputs, and whether these outputs could be explained, remain research concerns [31]. Conversely, the integration of real-time sensor feeds, wearable monitors, and computer vision is becoming increasingly popular, as reported, facilitating the identification of unsafe behaviors or precursors to accidents that directly influence on-site practical applications [32]. However, they rely on large, labeled information sets, which are regularly complex to obtain in the development setting. Even though assorted examinations have employed designs like Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and collection methods to boost predictive functionality, the incorporation of these into useful site-level decision-making remains confined. While machine learning approaches, including Random Forests, SVMs, and ensemble strategies, have demonstrated improved predictive performance, their translation into actionable site-level decisions has yet to be widely realized [33]. Most high-performing deep learning models remain “black boxes”. Therefore, recent efforts are focused on explainable AI approaches to bridge this gap and make outputs actionable in safety management [34]. Additionally, most present works deal with ML yields as definitive, with nominal extent for specialist reinterpretation or alteration.

Recently, researchers explored the concept of introducing human intervention in machine-driven risk assessment tools to improve adaptability and trustworthiness. Therefore, interactive systems, especially those with graphical user interfaces, are increasingly being implemented to give engineers and safety managers the capacity to observe risk levels and participate. In a study conducted by Okpala et al., a comprehensive safety risk assessment tool was created for human–robot interaction (HRI) in the construction industry. The tool was created across sequential steps involving expert panels, literature reviews, and industrial interviews that enabled the determination of primary HRI hazards and mitigation methods [35]. Comparably, ongoing work by Lin et al. is exploring the coupled risk assessment of unsafe behaviors of workers under HRI. Their research is developing a multi-level indicator system to assess both external and internal risk factors, combining surveys of experts with hierarchical assessment and fuzzy evaluation [36]. Human–computer interaction (HCI) practices and designs are also being academically studied in this context, as shown in the recent reviews into HCI’s empowering role in construction safety management [37]. The studies suggest that HCI systems, enhanced using GUIs and feedback systems, can empower users to understand HRI-associated risk outputs better through clearer information provision. HCI systems also allow for two-way communication to enhance model learning, allowing for continuous incorporation of new inputs, and trust establishment between practitioners and technology [37]. However, in response to experts’ disagreement, most of these systems did not establish a closed loop to support model retraining or adjustment. Hence, this does not provide for continuous learning and evolution of systems according to existing realities in the field.

There are still key gaps identified despite the growing literature on AI applications in construction safety: first, most predictive models operate as stand-alone systems with minimal interaction with humans. They do not exhibit the ability to incorporate expert judgment within the prediction loop to allow for retraining or adjustment of the prediction models in the long run. Second, there has been limited work in the provision of an integrated solution involving neural network-based prediction and a user-friendly graphical interface for real-time assessment and decision support. Furthermore, the majority of current systems are based on objective, sensor-based, or statistical metrics of risk, whereas real-world construction safety is often based on subjective, experience-based interpretations that cannot necessarily be encompassed in wholly quantitative inputs. Motivated by such gaps, this work advocates for a subjective human-centric risk modeling approach and presents an integrated platform that takes both the fuzzy-interpretivity aware neural network (NN) for quantitative prediction of events by embedding an expert-driven learning trajectory. The model can be used for linguistic and perception-based inputs coupled with a GUI, through which the expert feedback can update and retrain the model continuously. The hybrid system also demonstrates a practical safety-risk assessment tool subjectively and interpretably, which works as an early warning dashboard for proactive safety management by human–machine cooperation. Thus, the study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: How does a multilayer neural network model contribute to the prediction of multi-factor construction risks?

RQ2: To what extent can the incorporation of expert feedback, through a GUI, improve the accuracy and reliability of the model over time?

RQ3: Could an interactive, dynamic, and interpretable risk prediction tool assist in the proactive management of construction site safety?

3. Methodology

The research presented is a structured hybrid modeling innovation for frontline consideration of construction risks. The study was undertaken to embrace the dynamic, complex, and non-linear aspects of risk in construction work while achieving transparency, adaptability, and usability at the field level. The multi-layered approach to modeling methodology consisted of eight integrated components being (1) research design and conceptual framework, (2) input engineering and rationale, (3) fuzzy-inspired linguistic categorization (4) neural network architecture and risk model, (5) expert feedback loop and adaptive learning (6) dataset composition and experimental setup (7) phase-wise model training and expert-based refinement, (8) system implementation and interface design.

3.1. Research Design and Conceptual Framework

In this study, a risk assessment model has been developed for fall-related hazards in construction sites. The architecture is built on a staged modular model of the system to allow for interpretability and iterative improvement throughout various operational phases. The risk assessment starts with the acquisition of structured input values to describe crucial factors, which might be causative for fall-related hazards. The factors are fed into a neural network model that outputs continuous numbers as the likelihood and severity of possible risks. The resulting values are translated into fuzzy-inspired linguistic categories that extend the notion of distinct cutoff points to exploit the gradual risk. The fuzzy-inspired nature of this approach allows the model to state risk assessments in understandable linguistic terms, which is vital for the formalization of rational reasoning from experts through the computational output. The classified results are displayed to the user using an interactive graphical user interface (GUI). Hence, a safety specialist validates or corrects the model’s risk assessment. This expert feedback is recorded systematically and fed back to the training of the model, in a continuous learning loop [38]. As the system learns through iterative rounds, it steadily improves upon its internal risk representation to make increasingly domain-expert-like inferences.

The stage-wise breakdown increases modularity and transparency, which makes it easier for practitioners to pinpoint specific factors or phases in the project to study while supporting their corrections with minimal disturbance to the whole system [39]. This type of approach also increases traceability and user trust, serving as key considerations in a high-stakes construction safety environment where liability and operational accountability are major factors [40]. The block diagram of the overall methodology is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Workflow diagram of the overall methodology.

3.2. Input Engineering and Rationale

To acknowledge the multifactorial nature of construction risk, the model assumes four principal input categories: (i) Design and Planning Inputs, (ii) Hazard Inputs, (iii) Influential Inputs (iv) Safety Barriers, as shown in Table 1. Each input is recorded in numerical format, but the inputs are also associated with predefined fuzzy linguistic labels to increase the perception value [41]. The design and planning inputs included are assessment of risk and constructability, structural layout and location of the project site, safe working conditions during work at height, and planned provisions for protection of slab edges and structural openings.

Table 1.

Input Parameters and Fuzzy-inspired Linguistic Category.

These inputs are mostly completed through the early design phase and are particularly useful for hazard mitigation or prevention [42]. Each item is also tagged with qualitative descriptors for comparison, like “Poor”, “Satisfactory”, “Good”, and “Excellent”. The hazard inputs reflect specific strata of fall types, such as from roofs, scaffolds, ladders, and from machinery or moving platforms. These factors approximate the base risk of inherent conditions at the site and are also grouped into levels of risk labeled as “Low”, “Medium”, “High”, and “Critical”. The model consists of 20 unique inputs, which are mapped to linguistic labels for semantic interpretability (Table 1). All inputs are normalized to the [0, 1] scale prior to inputting into the neural network. Layered classification of the inputs allows the model to represent the complete causal chain of risks from planning to mitigation. In general, any planning error creates a potential for increased exposure to hazard, influenced by behavioral choices/client preferences, and even if there is a safe practice presence in the form of safety systems or processes, it would still not provide error-free safe work [43].

The current twenty-input model reflects structural, procedural, and preventive fall-risk, but neglects highly variable operational contexts, including equipment motion, environmental transiency, and human–machine interaction. The fact that such differences in learning rates were already found at an early level of model testing might indicate underrepresentation of some latent variables, particularly those associated with time- and force-related dynamics. To overcome this limitation, the next phase of model development will consider further inputs describing machinery operational data (e.g., lifting operations frequency, moving equipment proximity to elevated edges), temporal and environmental indicators (duration of shift, surface wetness state, visibility conditions or weather stationarity), and human–organizational factors such as density of supervision ratio, intensity in coordination effort among operators and overlap in task sequencing. Incorporating such dynamic inputs is anticipated to facilitate a more robust representation of on-demand site conditions and enhance the model’s foundation for generalization across diverse site conditions.

3.3. Fuzzy-Inspired Linguistic Categorization

Safety data in construction domains is qualitative and depends on context, with imprecise quantification of “poor maintenance,” for example. To deal with this linguistic vagueness, a fuzzy-inspired linguistic categorization approach is used. Different from complete fuzzy inference systems based on mathematical membership functions, in this scheme, the fuzzy-inspired mappings are used to capture the linguistic interpretability of fuzzy logic, and yet keep computation simple. This design decision is deliberate; it enables a simple and lightweight implementation that can be effectively incorporated into neural learning and expertise feedback loops without adding the extra level of rule-based fuzzification. All input features (i.e., Influencing Factors, Hazards, Safety Barriers) are mapped to a finite set of fuzzy-inspired linguistic terms that can capture qualitative distinctions of risk gradation. For example, training quality could be linguistically determined as “Deficient,” “Fair,” “Satisfactory,” or “Outstanding,” with scoring criteria from experts. Output from models, as simple numerical values, are continuous values (on a [0, 1] scale) and expressed in fuzzy-inspired risk categories defined as:

(a) Values at ≤0.25 outputs are ‘Low Risk’

(b) Values between 0.26 and 0.50 are ‘Medium Risk’

(c) Values between 0.51 and 0.75 are ‘High Risk’

(d) Values above 0.75 are ‘Critical Risk’

Accordingly, the focus here is given in human-oriented interpretability rather than numerical fuzzification, so that it ensures the transparency and accessibility of the system to practitioners at early development and pilot implementation steps. The categories for inputs and outputs are in the system’s graphical interface, where numbers are flanked by their words. This dual representation supports interpretability, particularly for safety engineers and others in the domain of expertise, by enabling users to understand model output without delving into the mathematics behind it, thus furthering the explainability and usability of the AI-safety risk model.

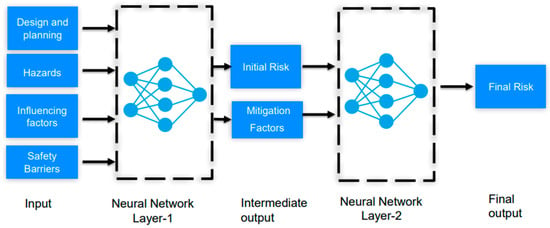

3.4. Neural Network Architecture and Risk Model

The key analysis engine of the proposed risk prediction system is a two-stage multilayer neural network (MLNN), built to approximate the risk assessment and mitigation logic in two stages (Figure 4). The benefit of this architecture is that it allows for a modular and interpretable flow of safety information, from raw input to actionable outputs [44]. The architecture consists of an input layer with 20 neurons, followed by two hidden layers—one with 16 neurons and one with 8 neurons. The model’s first stage outputs two intermediate variables called an ‘initial risk score’ and ‘mitigation effectiveness score’. The initial risk score reflects the estimated level of risk (before any intervention), whereas the mitigation effectiveness score reflects the amount of influence of safety barriers that have been planned to be put in place. Hence, the two outputs from the first stage will be concatenated and input into the second stage of the neural network, which predicts risk severity and risk likelihood, generating a complete post-mitigation risk profile. The architecture creates a separation between hazard assessment and mitigation, implementing a method that aligns with the hierarchy of risk control principles and the principles of systems thinking. It allows risk to be computed not as a final decision, but as a stage-wise process [45].

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the proposed neural network model for construction safety risk evaluation.

Due to its smooth non-linear properties and bounded output between [0, 1], Sigmoid was the function of choice for the hidden and output layers for probabilities of risks and fuzzy set boundaries. The sigmoid function is defined as:

The model is trained with the goal of minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between the predictions and the target values. The error function is defined as:

N = Total number of training samples.

= Actual risk likelihood (ground truth) for sample i, based on expert annotation or known outcomes.

= Predicted likelihood by the model for sample i.

= Actual risk severity (ground truth) for sample i.

= Predicted severity by the model for sample i.

Each squared term measures the quality of the predictions (predicted values and actual values). Both outputs (likelihood and severity) errors are summed within each damage, and then all damage errors are averaged, resulting in the final MSE, which will penalize larger errors more heavily, which in risk modeling is desirable, because a large error (i.e., predicting a high risk as low) could be very costly. Likelihood and severity are treated as continuous variables in the range [0, 1] with the same sigmoidal output, and MSE, which is continuous, smooth, and differentiable, and is easy to minimize using stochastic gradient descent.

3.5. Expert Feedback Loop and Adaptive Learning

The system employs a human-in-the-loop (HITL) feedback process to entangle domain experts in assessments (Figure 3). After the model makes its predictions and fuzzy labels, the expert can either confirm the system assessment or offer different values. This feedback is captured in a structured log, which documents the original input vector, model predictions, expert feedback, whether the model predictions agreed, and the timestamp. When an expert disagrees with one of the model outputs, the new values are also saved and entered into the retraining dataset. When the experts have provided adequate feedback, the system will automatically call a retraining routine to update the model based on the extended dataset. This process enables the model to adapt over time to real-world conditions and expert expectations without the full redevelopment of the model [46,47].

All feedbacks will be logged into an Excel file using the Python (version 3.11.5) to ensure traceability in the design decisions we make [48]. Use of expert judgment at model deployment will correct the context and avoid model drift. Past work in safety-critical systems has shown that HITL has been shown to enhance accuracy and benefits the adoption of practitioners. The novelty in this study is that an HITL feedback loop is created that corrects the original model output in sequence with expert judgment and adjusted neural weights. Feedback from experts regarding model predictions allows the network to engage in online retraining that reduces the error between predicted and expert-licensed risk scores. Over time, the system incorporates knowledge capitalization, allowing for contextual calibration of the output of its predictions.

During this pilot phase, five experts were involved in the project, and among them, there were three senior professors who worked on the areas of safety and digitalization, and two researchers with experience in safety management and data-driven modeling. These specialists jointly reviewed the prediction logic of the system, linguistic mappings, and practical usefulness of the proposed methodology. After this internal assessment, an interactive workshop was held with partners from the Norwegian construction industry. Workshop attendees were taken through the functionality of the prototype and asked to provide qualitative feedback on its usability, and potential indicating a strong interest in the prototype’s future integration into digital safety workflows. Based on this engagement, formal collaboration with these partners for scaling and field-testing the system in real-life industrial scenarios is in progress.

3.6. Dataset Composition and Experimental Setup

The dataset used in this work was prepared as the pilot-scale dataset for testing the validity of the proposed human-in-the-loop neural–fuzzy framework. It consisted of a total of 100 expert-populated examples based on simulated fall-related construction situations. Every occurrence of the task was highly multi-attributed. The dataset was synthetically enlarged by variations in the controlled parameters, providing diversity to hazard situations with integrity and validated by domain experts. The output target variable was a composite ‘Risk Level’ coded on an ordinal scale, which represented the probability and severity of fall occurrences. Iterative incorporation of expert feedback was used to refine label accuracy and boundary definitions between the severity levels. As this phase was only exploratory and being defined abstractly, the dataset had to be small enough that it could be feasibly retrained iteratively and tested for interpretability within the GUI-based prototype. Five-fold cross-validation was applied to assess internal consistency and mitigate the potential for model overfitting, showing that consistent performance trends were observed across folds. Finally, external validation on multi-project/multi-factorial large-scale datasets from industry will be part of one upcoming industrial collaboration phase to guarantee the generalisability of the model for prediction.

The whole system is implemented in Python using standard scientific libraries. The learning process is based on training the model on labeled input samples, rating the outputs, and incorporating expert feedback, allowing for an incremental learning process based on the chains of experience. Data persistence is made possible through logged information in Excel, thus documenting and allowing for the polished feedback loop to be reviewed for quality control during any review. All experimental runs were archived with the model version and feedback given for a possible future audit of feedback implemented in the model and consequent performance testing with cited references. The system was tested on a local workstation with a few safety experts.

3.7. Phase-Wise Model Training and Expert-Based Refinement

The neural network (NN) model was trained in three progressive phases, which are stated below:

- ○

- Phase 1: The base model was self-trained on a simulated dataset with 1000 randomized input ensembles over the 20 features. This dataset represented hypothetical fall-risk conditions that allowed the NN to determine starting weights and approximate first-order risk–mitigation relationships over 500 epochs of self-learning.

- ○

- Phase 2: After the pretraining, a pilot presentation was carried out with two domain experts in the project consortium. Analysts examined 200 manually developed scenarios in which the model generated predictions of initial and final risk. Their corrections were added to the Excel-type feedback log, which was employed as an augmented training dataset used for retraining. In this way, the model was able to learn from expert reasoning patterns and recalibrate its internal weight structures.

- ○

- Phase 3: After that, the model was presented to five domain experts, with 100 scenarios, and of them, the last 20 test cases of four fall accident types are highlighted in this paper. The improved model was subsequently also demonstrated to four leading Norwegian construction companies in a day-long workshop where ten domain experts were present through an ongoing industrial collaboration with the NTNU-DiSCo project. This stage was aimed at validating the model’s applicability to real-life building projects and incorporating their feedback into the model.

Through this staged approach, the system progressed from a synthetically trained starting point to an expert-calibrated adaptive model that was learning continuously from human input and increasingly matching its output with field-derived pragmatic safety logic.

3.8. System Implementation and Interface Design

To build a user-friendly GUI, basic Python libraries are utilized, where users are able to input values for all twenty parameters by using slider controls. Each slider is labeled with the appropriate fuzzy terms, making it intuitive to select an input. The GUI further includes a real-time prediction display of the computed severity and likelihood values represented as both progress bars and textual identification. The user is then presented with the option to agree or disagree with the model’s prediction. This interactive GUI is the main interface that experts will interact with, supporting automated predictions while leveraging human involvement (Figure 2). It allows field engineers and safety officers to engage with the model without any programming knowledge. The current GUI presents the following:

- Scenario development through the collection of slider data

- Risk prediction display

- Expert feedback and correction

- Visualizing statistics and associated feature weights of the neural network

4. Results

4.1. Scenario-Based Hazard Simulation

A structured set of simulations based on scenario analysis was conducted to test the performance and context-specific nature of the proposed predictive model. The simulations included a range of construction site scenarios associated with elevated fall accidents, which were developed for the four primary classes of fall hazards: falling from a roof, falling from a scaffold, falling from a ladder, and falling from equipment or a moving platform. Four input domains were included in each design scenario as follows: Design and Planning (DP), Hazard Intensity (HI), Influencing Factors (IF), and Safety Barriers (SB). Values of these inputs were subjectively assessed and ranked on a four-point scale (Low, Medium, High, and Critical) and were translated into numerical figures ranging from 0.0 to 1.0 in 0.25 increments for the model processing. Importantly, in each hazard-specific simulation set, the target hazard level was different in left-out cases. In the other three hazard types, the corresponding hazards were fixed at zero to isolate the model sensitivity to specific fall conditions. Twenty test cases were implemented, five for each hazard category that capture a balanced mix of high-risk, low-risk, and intermediate safety levels. A concise qualitative description was attributed to each situation, setting the stage for the inputs and explaining the type of simulation setting. The five scenarios of ‘fall from roof’ are shown in Table 2, from a presumably hazardous-in-control task (Case 001) to both well-designed and well-protected cases that describe less dangerous scenarios (Case 004). However, Table 3 describes some ‘fall from scaffold’ whereas Table 4 shows the ‘fall from ladder’ situations, followed by Table 5, which focuses on ‘fall from machinery or moving platforms’.

Table 2.

Test scenarios for ‘fall from roof’.

Table 3.

Test scenarios for ‘fall from scaffold’.

Table 4.

Test scenarios for ‘fall from ladder’.

Table 5.

Test scenarios for ‘fall from machinery/moving platform.

4.2. Initial Model Performance Evaluation

To test the robustness and content relevance of the predictive model in its early stage, its performance was compared with expert feedback on the test scenarios that were described in the previous section. A baseline assessment was conducted to evaluate the model’s ability to estimate the likelihood, severity, and risk associated with different types of fall hazards, without requiring retraining based on expert input. The prediction model was built for the three major dimensions for each test case as follows: Likelihood (L), Severity (S), and Risk (R). These model-produced values were directly compared to expert feedback (EF) on the same dimensions. The absolute difference between the model’s prediction (MP) and the expert risk was defined as the Risk Difference (RD), which calculated the tightness of alignment of the machine prediction with the expert decision. The comparison is demonstrated in Table 6 under the ‘fall from roof’ case for the five test cases.

Table 6.

Model prediction and expert feedback integration for the test scenario of ‘fall from roof’.

Preliminary results show moderate differences in some cases. Case 001, for example, had a risk difference of 0.15, which suggests a difference between the model’s low risk estimate and the expert’s more pessimistic estimate. Conversely, Case 004, where the situation is well organized, the hazard is low, and the safety system is strong, has a somewhat lower RD of 0.10 or thereabout, indicating a good agreement here. These findings indicate that the model has a better performance in homogeneous conditions and under a low-risk level, and underestimates risk for more complex and higher-hazard scenarios. However, Table 7 summarizes model performance for fall from scaffold scenarios. This hazard type now has a slightly better rate of successful estimations than the roof cases. For example, Case 008, despite solid planning and safety infrastructure, yielded an RD of 0.10, revealing a good fit to expert judgment. For Case 006, with high hazard and low protection level, the difference was 0.28, once again indicating underestimation of the model in high-risk scenarios. These results further support the observation that the initial model state struggles in depicting the enhanced hazard complexities correctly.

Table 7.

Model prediction and expert feedback integration for the test scenario of ‘fall from scaffold’.

The comparative performance of the base model over five different ladder-related test scenarios is shown in Table 8. The model shows uneven consistency with expert judgements across cases, with risk differences between 0.08 and 0.14. The biggest difference is noticed in Case 011, in which the model underestimates the risk (MP = 0.27) compared with the high-risk (EF 0.41) human expert decision, and the difference is 0.14. This case was related to the unsafe work on the ladder and lack of planning, which may indicate that the initial model had difficulty accurately assessing deficits in design and planning. In contrast, Case 012 demonstrates a relatively higher covariance (minimal RD = 0.08) that shows the model has an enhanced capacity to estimate risk under well-planned and moderately hazardous ladder tasks. It should be mentioned that when dealing with well-defined safety barriers, Case 013, the performance of the model was satisfactory in terms of overall risk (MP = 0.49, EF = 0.37). Yet, small overpredictions in these cases show that the model can slightly tend toward conservative predictions when the safety control is stringent, but the safety scope complexity is moderate. Taken together, these results underscore the importance of nuance in factors that influence planning attributes that serve as the model during learning.

Table 8.

Model prediction and expert feedback integration for the test scenario of ‘fall from ladder’.

Table 9 demonstrates the performance on scenarios for the cases of ‘fall from machinery or rotating platform’. These are characterized by a more structured working space but can become highly hazardous if the controls are not effective, i.e., the assessed risk is high. Case 016 is the most discrepant model with the highest RD (0.16) in this risk category, where the model severely underestimated risk (MP = 0.40 vs. EF = 0.56). In this case, the risk was the use of hazardous machinery without proper training, so the model appeared to underestimate latent risks based upon poor design and lack of anticipation of hazards. On the contrary, it is depicted that Case 020, with a very low RD of 0.03, corresponds to a reliable prediction of 0.06. Intermediate performance is observed in Cases 017 to 019, where the distance between predicted and risk-based RDs is moderate, ranging from 0.09 to 0.13, which could be related to how accurately the machine learning model interprets extended subtle relationships between hazard exposure and mitigation factors. These findings serve to illustrate model performance in very high-design clarity, high-controllability settings (e.g., planned machinery platforms), but the model can benefit significantly from further development before the model can correctly infer risk from dynamic, underprepared machinery scenarios. The underestimation of risk within high-risk or low-structure environments highlights the need to incorporate expert knowledge in future model calibration.

Table 9.

Model prediction and expert feedback integration for the test scenario of ‘fall from machinery/moving platform’.

Across the hazards, a pattern emerges that model predictions align more closely with expert feedback in well-defined, low-to-moderate risk scenarios, but begin to diverge when the environment becomes more ambiguous or when multiple influencing factors interact. This limitation in generalization highlights the necessity for expert-informed retraining and suggests the potential for adaptive feedback integration to fine-tune the model’s behavior. Hence, the results of cross-table comparisons across Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 indicate that the model tends to conservative alignments, whilst where uncertainty and interdependency among influences is high, it tends towards risk underestimation. This pattern is also consistent with the theoretical expectations in that although the neural architecture captures well linear hazard–barrier relationships, it has difficulty with non-linear and complex site dynamics. They further suggest that the model’s generalization ability is better for explicit safety controls (revealing its current reliance on barrier effectiveness as a critical predictor). The differences in observed risk difference (RD) for the different levels of hazard show that it is necessary to increase knowledge derived from domain experts to ensure a better contextual interpretation and weighting of the planning parameters. These results thus confirm that the human-in-the-loop retraining strategy is required, as manual corrections by experts would be anticipated to iteratively alleviate the underestimation bias of model prediction and further improve its generalization to diverse construction sites.

4.3. Model Retraining and Feedback Integration

To further improve the fitness between model predictions and expert opinion, a total of 100 additional training samples were used after being expert augmented. This iteration attempted to improve the model’s comprehension of risk profiles, specifically for underperforming districts that were found during the first step of evaluation. The retrained model (MP2) was also evaluated on the same original five scenarios for each category of hazard. Performance was re-evaluated with new predictions on new expert feedback using an adjusted risk difference (RD2), which measures the absolute difference between the expert’s risk score and the second iteration of the retrained model.

In Table 10, the retrained model showed better approximation against the expert risk assessments in all five of the roof-related scenarios. The average RD values before retraining (RD1) ranged from 0.10 to 0.15, but the post-retraining differences (RD2) decreased consistently (between 0.02 and 0.07). In Case 002, the risk estimation changed from 0.53 to 0.44 while the risk difference was reduced from 0.11 to 0.02. For case 004, with the retrained model, the predicted risk value (0.13) was a lot closer to that given by the expert (0.17), reducing the RD from 0.10 to 0.04. This decrease in RD means that retraining helped the model get a better hang of the risk threshold values as well as how to make use of context given by the experts, even when planning and control variables are nuanced.

Table 10.

Comparison of risk after retraining for the test scenario of ‘fall from roof’.

Of the four risk types, scenarios regarding scaffolding resulted in the greatest reduction after retraining. Table 11 shows that the original model has large relative deviations, which significantly decreased to 0.11 and 0.03 after post-retraining. For instance, for Case 006, the model’s risk estimate was enhanced from 0.20 to 0.37, which is closer to the expert’s risk judgment (0.48). The average RD2 among the cases decreased by more than half, proving that the retrained model successfully learned the hidden risk factors and design weaknesses that were underestimated by the original model.

Table 11.

Comparison of risk after retraining for the test scenario of ‘fall from scaffold’.

Retraining also resulted in quantifiable improvements in ladder-based predictions, although with less magnitude. As presented in Table 12, RD1 values were between 0.08 and 0.15 before retraining and ranged between 0.03 and 0.09 for RD2 values after retraining. The largest decrease was observed in Case 011, where the risk difference went down from 0.14 to 0.09, and in Case 012, where it decreased from 0.08 to 0.06.

Table 12.

Comparison of risk after retraining for the test scenario of ‘fall from ladder’.

Retraining for ‘fall from machinery or rotating platform’ also resulted in an improvement in model performance for all test instances. In Table 13, we can observe that RDs are decreasing, RD2 values falling to 0.02 in Case 020, against pre-retraining RD1 values of 0.16 in Case 016. The largest amount of improvement was observed in Case 017, by which the RD decreased 0.08, further indicating that the mechanical complexity model and control strategy were better recognized post feedback integration. However, Cases 018 and 019 also risk differences of 0.09 and 0.03, respectively, indicating that the retrained model was better able to consider the feedback on these high-risk rising platform hazards, and the risk weighting was more accurate given operational and planning variables.

Table 13.

Comparison of risk after retraining for the test scenario of ‘fall from machinery/moving platform’.

4.4. Comparative Risk Difference Analysis Across Hazards

Table 14 compares four hazard types and their corresponding risk reduction in ‘before retraining’ and ‘after retraining’. All hazard types demonstrated that risk was decreased after retraining with an integration of expert opinion (Figure 5). Significant improvement was witnessed in falls from ladders at 55.74%, followed by falls from roofs with 52.54%, and falls from scaffolds at 45.33%, and falls from machinery at 27.91% depicted the least amount of improvement. Hence, retraining can reduce workplace hazards, specifically in high-risk situations associated with elevation.

Table 14.

Summary of Mean Risk Differences Before and After Retraining.

Figure 5.

Comparison of mean risk difference (RD) values before and after safety retraining intervention across four fall hazard categories.

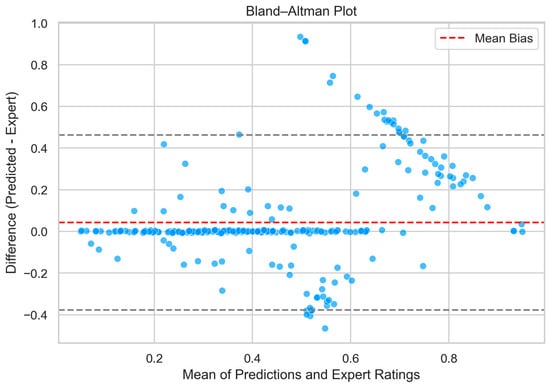

4.5. Performance Validation

The current performance validation demonstrates the results from the three-phase progressive training framework described above in Section 3.7 and signifies the development in the maturity of the proposed expert-feedback neural network model. Initially, the model was trained in a purely self-supervised fashion on simulated datasets to provide an anchor weight and degree of sensitivity to internal features. Following self-training, the model was sequentially refined through two cycles of expert-augmented learning, in which domain specialists provided corrections and guided the system’s predictions of fall risk across various scenarios. The current validation results are based on the most recent 300 paired samples, corresponding to the model’s predictions and expert predictions on these same model outputs. This group of data reflects the synthesized learning and cognitive scaffolding acquired through purposeful and structured expert engagement. Given the incremental development of this model, the current results need to be considered an evolving snapshot of a learning system, but not necessarily an endpoint in performance. As more expert feedback and context-specific data become available, the model is expected to deepen its interpretability, predictive consistency, and human-aligned reasoning.

To assess the proposed expert-feedback neural network’s prediction and cognitive alignment ability, a variety of quantitative performance metrics were employed [49]. These complementary metrics evaluate accuracy, bias, consistency, calibration, and distributional similarity between the expert-assigned risk score and system predictions across the data instances. For instance, Mean Bias Error (MBE) refers to the average signed error, highlighting the system’s overestimation or underestimation trend. Small and positive numbers indicate there was a slight conservative bias (overconfidence), which is advantageous in cases where predictions are safety-critical.

On the other hand, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average unsigned error, and thus it gives an interpretable result of how accurate the method was in evaluating overall accuracy. However, the Root Mean Squared Error was also calculated, which emphasizes larger differences more strongly since larger differences are penalized more than smaller ones based on squared error values.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is another measure; however, it measures the linear association between expert risk and predicted risk scores. The Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) overcomes limitations of Pearson correlations because the Concordance Correlation Coefficient measures both linear relationships and means or variance discrepancy [50]. Higher values of the Concordance Correlation Coefficient indicate predictions not only had a correlation but were also concordant in scale and mean.

Furthermore, the Expected Calibration Error (ECE) measures the degree of concordance between predicted and observed risk frequencies, quantifying the correspondence between predicted probabilities and true expert evaluations, where K is the number of probability bins [51].

To investigate distributional similarity, two additional but complementary metrics were employed: the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD), a symmetric measure of information distance between predicted and expert probability distributions, and the Wasserstein (Earth Mover’s) Distance (WASS) metric, which represents the minimum “cost” associated with transforming one distribution into another. Both metrics provide insights into how closely the system’s probability outputs resemble the shape and variability of expert-derived risk profiles [52]. Finally, directional error metrics such as over- and under-prediction errors, and the Symmetry Index (SI) metrics, summarize behavioral tendencies of the model. A positive SI indicates that the one model is conservative in its bias toward overprediction, which, honestly, is an optimal quality in modeling safety dilemmas proactively.

Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive framework to assess both numerical performance and cognitive fidelity of the model’s outputs reflect expert risk perception, allowing for evaluation that extends beyond statistical validation, to evaluate the structure and how effectively the model reflects human safety thinking. The quantitative evaluation results are presented in Table 15.

Table 15.

Summary of performance metrics.

In this pilot case, the Mean Bias Error (MBE) equals 0.043, indicating a small positive bias, and suggests that the system is slightly overestimating the experts’ ultimate risk ratings. This behavior is not necessarily a weakness in a safety-critical domain where conservative estimates serve as a protective buffer for proactive risk identification. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.1148 and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.2188 indicate there is moderate absolute and squared deviation between the model’s predicted risk and expert assessment, which are both reasonable given the nature of risk data derived from subjective experts and the non-linear mapping of cognitive judgment to tangible features. Within this narrow probability range, the variation in magnitude stays within a cognitive threshold associated with subjective judgment, establishing a premise that this system retains more of the behavioral tendencies of the experts than simple adherence to numeric rigor.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.567) and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC = 0.538) show a moderate-to-strong linear and concordant relationship between expert and system judgments. By establishing concordance above an acceptable threshold of 0.5, these results further establish the capability of the system to retain the constructs of domain knowledge and articulate through iterative feedback of experts. The concordance above 0.5 is notable considering the data was completed and collected as part of a small pilot initiative, suggesting the system has realizable scalability as well as reliability once exposed to a larger and more heterogeneous sample of data. However, from a calibration standpoint, the Expected Calibration Error (ECE = 0.0996) communicates that risk probabilities predicted by the system were typically aligned with the expert observations, showing just less than 10% average differences across bins of probability. The low ECE values further reinforce the argument that the neural network (NN) can create interpretable and human-aligned confidence scores as opposed to simply producing arbitrary probabilities.

On the other hand, the Jensen-Shannon Divergence (0.0936) and Wasserstein Distance (0.0475) illustrate close similarities in the distributions of predicted risk profiles with expert risk profiles, indicating that our model preserves the structural shape of the risk landscape designed by its experts. The small divergences suggest that our model not only correctly predicts risk magnitude but also does a better job of capturing the cognitive distribution found in expert decision-making, which indicates successful knowledge capitalization.

Figure 6 shows the Bland–Altman plot to evaluate agreement between system and expert risk-score ratings. The scatter plot shows that most data points fall within the 95% limits on agreement, indicating the two risk ratings were reasonably aligned. The mean bias (red dashed line) is close to zero, demonstrating little systematic bias and an overall unbiased assessment of subjective risk rating, with slight conservative overestimation consistent with the safety-critical context.

Figure 6.

Bland–Altman plot comparing expert-assigned and system-predicted risk scores.

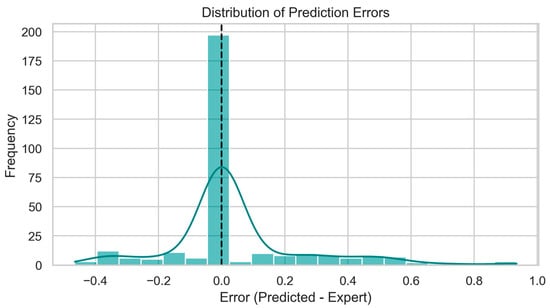

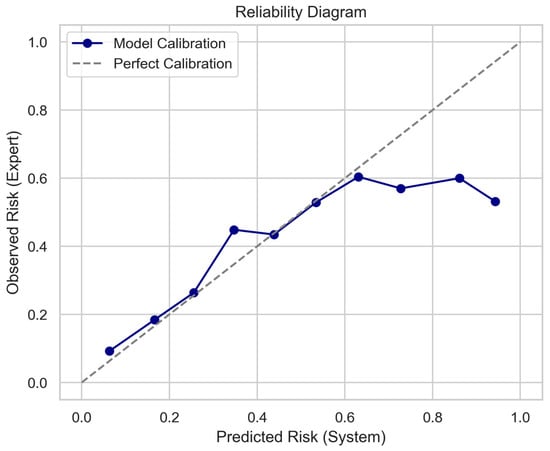

Figure 7 shows the distribution of prediction errors, suggesting the predicted scores exhibit a near-normal distribution centered around zero. The limited spread of deviations indicates a sharp peak at zero and light tails on both sides, suggesting that most predictions were close to expert ratings. This evidence supports reliability and consistency for the model’s subjective risk estimation across diverse input conditions. Figure 8 illustrates the reliability diagram that evaluates the calibration of predicted risk probabilities. The model calibration curve tracks closely to the ideal line, with few deviations from the diagonal, demonstrating good agreement between predicted risk estimates and the observed (expert) risk estimates. The overall close adherence to the calibration line indicates that the model is well-specified from the subjective probability distribution of risk, obtaining predicted risk levels corresponding with expert risk evaluation across all safety conditions.

Figure 7.

Distribution of prediction errors between model outputs and expert ratings.

Figure 8.

Reliability diagram illustrating the calibration of predicted and expert-observed risks.

In summary, the symmetry shows that the model predictions are 59.3% overestimations and 40.7% underestimations, giving a Symmetry Index of +0.186. This indicates a slight positive skew consistent with the intended conservative bias in the learning framework, which made errors in terms of a prior of safety, as overestimation may be believed would be safer. In practical safety applications, a bias in retribution is preferable; the operational risk associated with underestimating hazards is higher than if we were to overestimate. Overall, the findings suggest that the model has a promising level of predictive reliability and learned subjective construction risk tendencies from a small but representative expert-informed sample.

4.6. Usability, Compatibility, and Prospects of the Graphical User Interface

The GUI developed during this study is a pivotal component in the transition from a concept-based machine learning model to a real, safe, and user-friendly way to monitor for safety in construction. As Figure 4 shows, the GUI was designed to allow users to easily access and receive succinct information about fall accidents, which encompass design problems, types of hazards, what impacts them, and safety actions. The basic design structure means each component can be utilized independently, which simplifies creating a particular risk and evaluating its respective hazard level. The strength of the GUI is that it is so user-friendly. Individuals can input what their respective occupation requires, alter the risk scenarios by shifting sliders or selecting from a list, and review what the associated risk denotes as it exists, simultaneously. The GUI includes steps described by the model and expert decision, which reinforces how the output arrived at its decision, whether it is preferable or worse. Its construction also means that it can store what the individual has modified, which aids in reviewing each time, engaging in a learning activity, and generating a record. The most important thing about how the GUI is configured is that it can be modified and tuned. It can represent more hazard types and different ways of achieving safety without having to be constructed from scratch again. In the event there is more data, or the rules of safety have changed, the GUI can be modified to include additional variables, retrain models, or change what it is evaluating from. This allows it to expand and apply other risks and hazards in work sites in addition to falls.

From a systems perspective, the GUI is interfaceable with a digital twin, tools that observe whether hazards exist on a work site, and ways to identify hazardous risk in real time. Being small, with an uncomplicated means of gleaning what people want, it can be deployed on a myriad of computers. It can be deployed by itself on a work desk or as part of a more robust safety management system in the cloud. In short, the GUI can help speed risk check-ups, be accurate, and also be a way to apply modeling into something that can be done at a work site. Its flexibility, simplicity, and clarity make it a good way to help individuals make decisions to plan safety and mitigate risk in real time. It can be applied to safety for a whole work site in the building sector.

5. Discussion

5.1. Positioning the Proposed Model Against Mainstream Approaches

The results of this study reveal quantifiable enhancements in accuracy, adaptability, and interpretability of the hybrid neural network approach with expert-in-the-loop modification. Firstly, the estimation of risk severity and risk likelihood made by the fuzzy-coded inputs of the model exhibits a potentially reasonable estimation that can further be corrected by experts. When the adaptive feedback mechanism was applied, there was noticeable convergence between predicted and expert-rated risk levels across iterations, thus affirming the central hypothesis that human corrective input would improve the learning trajectory of the model. Different from classical static risk matrices or rule-based methods, the dynamic learning property that is achievable through neural network systems can improve the generalizability of complex interactions among the input variables, including design and planning parameters, hazards, influencing factors, and the effectiveness of safety barriers. For instance, risk scenarios that involved simultaneous failures of scaffolding systems and personal fall arrest systems were assessed with greater strictness after the feedback iterations, which is an outcome not easy to achieve by using fixed-threshold methods.

Table 16 demonstrates two prevalent paradigms in today’s construction-safety research: (a) static, high-performance predictors such as RF, SVM, deep nets which can learn promising patterns from large labeled examples but are not easily adaptive to new knowledge, and (b) Rule or fuzzy systems providing human interpretability and alignment at the cost of limited capacity for scalable learning from data. Most of the studies either improve predictive accuracy or interpretability and domain alignment, but do not offer a functional approach for in-field, continuous expert-driven model adaptation. This methodological shortfall motivated our proposed hybrid architecture, a two-stage neural estimator for the non-linear dependencies in region-specific data, and a fuzzy mapping layer to present output in practitioner-oriented language, in addition to an explicit human-in-the-loop retraining mechanism that is logged through the GUI.

Table 16.

Comparative analysis of existing AI-based safety risk models and the proposed study.

5.2. Methodological Impact

The methodology offers a new human-centric learning loop to the risk modeling space. The model acts more like a co-learning instrument than a black-box predictor when the input teacher correction is interpreted as part of the neural network weight update process. This is consistent with the trends in explainable AI and trustworthy machine learning, especially in high-stakes situations such as construction safety. However, the use of fuzzy linguistic input encoding, where the non-technical user can encode with domain-related language (e.g., “Poor”, “Satisfactory”, “Highly Effective”), which is transformed into numeric values for computational processing, lowers the barrier to adoption, requiring less complex input from the user, which is especially important in lower resource contexts. On the other hand, the two-stage neural network architecture, where the transformation of scenario inputs took the form of initial and refined risk outputs, demonstrates a conceptual development, mirroring how safety practitioners assess raw risk and then build mitigation layers to reach a final decision, ultimately aligning the machine logic with human logic, which answers RQ1.

5.3. Practical Implications

The proposed adaptive risk assessment model can revolutionize decision-making and real-time risk assessment and management in construction safety. By fusing neural networks with expert feedback circuits, it empowers site engineers and safety personnel to continuously assess and respond to risks on dynamic construction sites. This is beneficial in very high-risk environments where safety is volatile and static plans and formal checklists, or event-matrix approaches, often fail to account for real-time changes. However, the fuzzy linguistic input features drastically lower the technical knowledge and expertise barrier for end-users. Construction site supervisors and foremen can use the GUI to manipulate scenarios and see how their adjustments impact the risk, without needing to have an education in data science. Thus, RQ3 is addressed by showing that an interactive, dynamic, and interpretable tool supported proactive construction site safety management by enabling domain experts to use the system in a meaningful and intuitive way. Hence, it will provide the potential for widespread acceptance and adoption both in large and small construction firms and in a developing context where technological acceptance and literacy may vary significantly. Moreover, the proposed model acts as an assessment but also as a training tool to continually adapt the knowledge of risk assessments and control measures. In this way, practitioners can change and correct the errors made by the model, capturing the tacit knowledge or safety heuristics that often go unnoticed by standardized protocols. Through this feedback mechanism, RQ2 is also addressed, as the model demonstrates significant improvements in the prediction of risk and reliability over time by incorporating expert corrections via GUI. In this sense, risk assessment acts as both an assessment and a knowledge reinforcement tool, which provides an opportunity for organizational learning, auditing, and accident investigation. Although the GUI was tested against scenarios related to falls, the model can be applied to several other construction hazards. Organizations can also modify the various input fields and categories to match site-specific characteristics or legislative requirements.

5.4. Theoretical Implications

This research furthers the human-in-the-loop machine learning space and proposes a hybrid framework where domain experts not only provide data but also make decision corrections on the system. The framework allows for better reliability of predictions while aligning machine learning outputs with expert intuition, which appears to be an area of research that is not well developed in the construction safety modeling literature. This demonstrates that expert feedback loops enhance model learning and theoretical soundness when incorporated into model architecture, hence supporting RQ2. The contribution of this work lies primarily in the introduction of a multi-layered neural network architecture that decomposes overall risk into intermediate outputs (initial risk and mitigation factors). This is a novel modeling approach to safety risk, and it allows safety professionals to think through the division of inherent and residual risk in ways that mimic the intuitive distinctions. This new perspective opens a new way to represent risk theoretically. The fact that fuzzy linguistic scales were used as the inputs to neural networks helps provide a suitable bridge between qualitative assessments of safety and the quantitative models of machine learning. According to RQ3, this method makes it possible to create an understandable and transparent model that captures the complexity of actual safety decision-making. This work exemplifies the emerging trend in the literature exploring connections between human thinking, reasoning, and ambiguity, with traditional, rigid computational models. Of the many criticisms of traditional neural network models, many have been accused of possessing a ‘black-box’ trait. By incorporating transparent, graphical user interface (GUI) visualizations of weight adjustments and the ability for users to observe changing weights, this work offered innovative practices in relation to explainability and transparency of artificial intelligence (AI) models in critical domains like construction safety.

5.5. Limitations

Although satisfactory results are obtained, this study has its limitations. In general, the system currently only accommodates prescribed input categories, i.e., structured data types, and does not accommodate unstructured data types (e.g., text logs, real-time sensor feeds). Also, adding feedback from more experts, while extremely valuable, creates variability based on the scoring and ruggedness of the individual’s cognitive judgment and risk tolerance, which may add inconsistency in deployment delivery. Additionally, the pilot model was trained by a small group of safety experts in a controlled environment and needs to be trained in a large-scale industry setup, which will ensure more generalizability, credibility, and reliability of the model. Moreover, this paper has been carried out using a pilot-scale proof-of-concept testbed setup as part of the NTNU DiSCo initiative, and thus, full-size testing in a real-world environment was beyond scope for the present phase. Because of the dynamic and data-driven nature of the construction industry, validation should be based on long-term industrial relation-building and data-collection efforts that are already taking place through ongoing research. Finally, as it is a conceptual prototype at an early stage and the purpose of this study does not cover developing standardization for benchmarking AI safety systems, enabling the standardized metrics is left as future work. Standard protocols for the evaluation of hybrid AI models specific to the construction safety domain are still lacking, and practically, this will require multi-year, cross-sectoral cooperation.

6. Conclusions

Considering the complexity of construction risk in multiple layers, this study developed and demonstrated a modular, human-centered, multi-layer neural network-based model that incorporates design planning parameters, hazard identification, influencing factors, and safety barriers into an expert-feedback-guided learning architecture. The essence of this paper is a hypothesis by which early-phase data-informed and feedback-driven safety predication models can offer substantial enhancement on the process of construction risk identification and mitigation in comparison to the traditional static assessment. The two-layer design of the model, which can produce risk scores both at the intermediate and residual levels, is a real-world analogy of the way safety decisions are taken—initially by estimating predictive risk and later adding some value due to disease-inducing conditions and mitigation activities. Most importantly, incorporating expert feedback into the iterative training process provided a new approach to adaptive learning to improve model accuracy and encourage convergence to reality. The results highlight the following key contributions:

- ○

- ‘Integral input modeling’ where the comprehensive settings of planning, hazard, contextual, and control inner parameters contribute to mimic the construction risk landscape. This directly addresses RQ1 by demonstrating how the hybrid neural network–fuzzy logic framework enables the prediction of multi-factor construction risks in a structured and interpretable manner.

- ○

- ‘Enhanced predictive performance’ where the neural network exhibited potential development of accuracy during the expert interactions, implying a possible path to ongoing model improvement with human-in-the-loop processes. This finding answers RQ2 by showing that expert feedback, captured through the GUI, systematically improves both the accuracy and reliability of the model over time.

- ○

- ‘Usability and interpretability’ as the incorporation of a graphical user interface (GUI) allows on-ground engineers and planners to interact with the model in real time and serves as an interface between the AI-driven analytics and on-ground decision-making. This directly addresses RQ3 by demonstrating that an interactive, dynamic, and interpretable risk prediction tool can effectively support proactive management of construction site safety.

From a theoretical viewpoint, this paper extends current smart risk decision-making systems by proposing an AI model that includes the modularized, explainable, and adaptive multi-source risk logic for a smart environment. Operationally, it provides a pilot prototype system to show how such systems can be integrated with pre-existing construction planning or digital safety audit systems for the aid of early-warning decision-making for safety. However, there are restrictions since the present model is based on a manually selected dataset and simulated feedback, and further field validation for a variety of project types and geographies would be required.

In practice, it would need to be integrated into current digital construction management systems (e.g., BIM platforms) and consider continuous data sharing pipelines from site sensors, inspection logs, and safety reports. Training programs would also be needed to ensure that safety officers and engineers can understand what the model is showing and then act based on it. But there are many challenges along the way, such as data sharing between organizations, reluctance to use AI because of issues around trust and accountability, and meeting transparency requirements in regulations. To address these issues, gradual adoption via pilot implementations and co-development with the industry partners is recommended. Working with regulators can be an additional way to demonstrate adherence and promote adoption.

Finally, this paper makes a case for an alternate approach to addressing safety in construction—away from reactive auditing and toward proactive, data-driven systems that learn at their core. The proposed approach sets the stage for future safety intelligence tools leveraging AI adaptability coupled with experts’ contextual knowledge. Although the full on-site integration remains as a future goal, this could be considered one more stepping stone towards the operationalization of predictive human-centered safety systems in construction practice. The first point is that safety will not be achieved just through inspection; safety has to be learned, adapted, and institutionalized through continuous data-driven actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.N. and A.R.; methodology, M.M.N. and A.R.; validation, M.M.N. and A.R.; formal analysis, M.M.N., A.R. and N.O.E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.N., A.R. and N.O.E.O.; writing—review and editing, M.M.N., A.R. and N.O.E.O.; Supervision, A.R. and N.O.E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (Grant no. 328833).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper is written within the project «Sustainable value creation by digital predictions of safety performance in the construction industry» (DiSCo).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Statistics on Safety and Health at Work. 2022. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Bria, T.A.; Chen, W.T.; Muhammad, M.; Rantelembang, M.B. Analysis of Fatal Construction Accidents in Indonesia—A Case Study. Buildings 2024, 14, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, D.R.V.; Boojhawon, R.; Bhagwant, S.; Levy, L. Factors affecting the occupational safety and health of small and medium enterprises in the Construction Sector of Mauritius. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueblood, A.B.; Yohannes, T. Fatal Injury Trends in the Construction Industry, 2011–2022. Data Bull. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.-M.; Won, J.-H.; Jeong, H.-J.; Shin, S.-H. Identifying Critical Factors and Trends Leading to Fatal Accidents in Small-Scale Construction Sites in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Rotimi, J.O.; Shahzad, W.; Bamgbade, J. Infrastructure digital twin technology: A new paradigm for future construction industry. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Pedrycz, W.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Chen, Z.-S. Artificial intelligence for production, operations and logistics management in modular construction industry: A systematic literature review. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzano, A.; Cascone, S.; Zitiello, E.P.; Nicolella, M. Construction Safety and Efficiency: Integrating Building Information Modeling into Risk Management and Project Execution. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrifaee, M.; Zayed, T.; Ali, E.; Ali, A.H. IoT contributions to the safety of construction sites: A comprehensive review of recent advances, limitations, and suggestions for future directions. Internet Things 2024, 31, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]