Abstract

Many Japanese special needs schools have adopted the School Management Council (SMC), involving residents and other stakeholders in school management. However, its influence on disaster preparedness remains unclear. We used a cross-sectional design to clarify the relationship between SMC adoption and disaster preparedness among 537 special needs schools across Japan. Data were collected using a self-administered survey conducted between November and December 2020. Chi-square tests were carried out for each item addressing adoption and preparedness. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the overall relationship between the SMC and shelter and equipment readiness, revealing significant associations for two items: having decided the division of roles in case of disaster with the municipality’s disaster prevention department (shelter preparedness) and the presence of a stockpile warehouse on the school premises (equipment preparedness). The SMC may support three key aspects of disaster preparedness: compensating for the lack of shelter experience among school staff, strengthening support for disaster victims through local community–municipal authority collaboration, and enhancing preparedness for unforeseen events. The SMC could thus be an effective strategy for strengthening disaster preparedness in special needs schools.

1. Introduction

In the event of natural disasters in Japan, such as earthquakes and floods, local residents often seek refuge in public facilities, including schools. The Sphere Handbook’s Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response identifies schools as essential shelter facilities [1]. The World Bank, through the Global Program for Safer Schools, seeks to enhance government capacity and promote investments in school infrastructure for disaster preparedness [2]. This is achieved through a comprehensive approach that includes technical assistance, knowledge sharing, and analytical support [2]. Schools thus play a critical role as emergency shelters during disasters, particularly because of their stockpiles and equipment.

In Japan, older adults, persons with disabilities, and infants, among other vulnerable populations, are legally designated as “persons requiring special consideration,” and the government is mandated to take appropriate disaster prevention measures for them [3]. Welfare evacuation centers for these individuals are secured by each municipality according to government guidelines. Examples include elder care facilities, support centers for persons with disabilities, child welfare institutions, health centers, and special needs schools [4]. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies emphasizes that when people with disabilities use facilities such as schools or hospitals as shelters, these must meet certain accessibility and sanitation standards [5]. In Japan, “welfare shelters” fulfill this role.

Special needs schools are institutions attended by children with disabilities. In line with the needs of their students, many such schools are equipped with emergency power supplies and medical devices such as bag-valve masks. According to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Disaster Prevention Guidebook, special needs schools may be used as welfare evacuation centers during disasters [6]. However, these facilities were originally equipped to support education, not disaster relief. During a disaster, if such schools serve as evacuation centers, staff must coordinate with local residents to operate medical equipment and prepare classrooms for evacuees. This points to an underlying assumption that teachers possess the capacity to respond during a disaster. Herein lies a critical issue in disaster response, as teachers typically lack shelter management expertise. This discrepancy between the designated role of the school and the professional training of its staff must not be overlooked. Cooperation with parents of children with disabilities is also necessary during such emergencies [7]. Indeed, children and persons with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to disasters [8,9].

To facilitate collaboration with local residents, including parents, the existing School Management Council (SMC; commonly known in Japan as the “Community School” system) can be utilized [10]. This system enables the implementation of inclusive educational activities by opening up schools, which they traditionally cannot access, to local residents. Education is self-contained within schools; however, allowing it to reflect the opinions of local residents has the potential to enrich educational content. This allows for a transformation from conventional “closed schools” to “open schools” and can be particularly effective during disasters. The SMC is a group of parents/guardians and community representatives appointed by law to discuss the management and operation of the school as well as the resources required thereof [10]. Similar initiatives can be observed in other countries. In the United States, for instance, “charter schools” are public schools run by individuals or organizations that have identified needs in the education system that are not being met by the current system and have applied to operate them [11]. Meanwhile, in South Korea, schools are required by law to establish a “school governing board” composed of teachers, parents, and community leader representatives [12]. Sharing the responsibility of managing welfare shelters through SMC meetings could reduce the burden on school staff, allowing them to prioritize the safety of enrolled children.

Disaster preparedness in special needs schools can be enhanced through disaster education programs [13]. Although preparedness improves when schools are designated as welfare shelters [14], to our knowledge, neither has a prior study assessed the effectiveness of the SMC in enhancing disaster preparedness in special needs schools nor has this relationship been examined from a disaster risk reduction perspective.

In Japan, guidelines indicate that special needs schools should also function as welfare evacuation shelters. However, when a disaster occurs, school faculty and staff alone cannot protect the lives of children with disabilities, who are highly vulnerable. Furthermore, it is extremely difficult for schools to maintain their function as welfare evacuation shelters. Collaboration with local residents offers a potential solution to this challenge, yet the effectiveness of community collaboration for disaster risk reduction has not been verified. The SMC is a system for such collaboration. Therefore, we aim to clarify the relationship between this system and the state of disaster preparedness by focusing on the SMC, which embodies community collaboration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A cross-sectional design was used to clarify the relationship between SMC adoption and disaster preparedness in special needs schools in Japan.

2.2. Survey

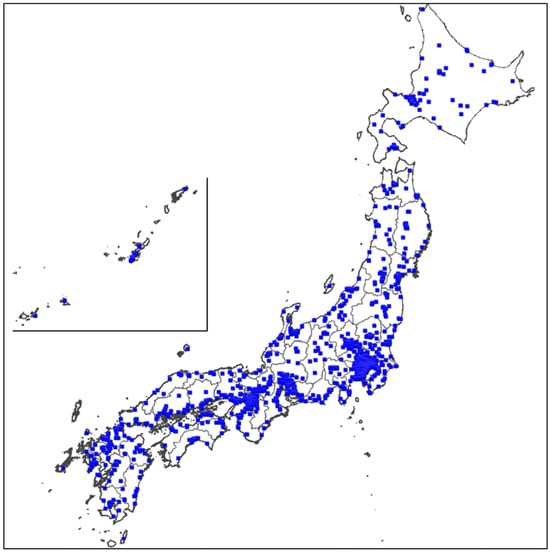

To examine the relationship between the implementation of the SMC and the level of shelter and equipment preparedness and stockpiled resources, a self-administered questionnaire was mailed to all special needs schools in Japan. The survey targets were determined according to a publicly available list of special needs schools in 2020, totaling 1310 (Figure 1). The survey was conducted from November to December 2020, with responses requested to be anonymous. Of the 1310 schools to which the questionnaire was mailed, 605 responded (response rate: 46.2%). Among these, 539 responses (89.1%) were valid, and the 537 schools (88.8%) that had completed all questionnaire items were included in the analysis. The return of a questionnaire was considered consent to participate in the survey. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Epidemiology of Hiroshima University (approval number: E-2224; date of approval: 12 October 2020).

Figure 1.

Special needs schools in Japan. Special needs schools from the 2020 list published by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), which served as the basis for selecting the survey targets, are shown as blue dots [15]. A blank map provided by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, GSI Tiles, was used as the background, and the locations of the special needs schools were plotted [16].

The survey instrument was a 22-item self-administered questionnaire. To ensure content validity, the questionnaire items were developed and refined through discussions among all authors. The items were classified into three categories: (1) personal factors (e.g., years of service at a special needs school, personal disaster experience), (2) school disaster countermeasures (e.g., involvement with local residents, implementation of drills assuming shelter use), and (3) facility-related preparedness (e.g., presence of a stockpile warehouse for emergency supplies, availability of toilets during a water outage). Each item included response options of “Yes,” “No,” and “Don’t know,” and some items also permitted free-text responses. The personal factors were designed to identify the respondents’ characteristics. The inclusion of items on school disaster countermeasures and facility preparedness made it possible to analyze their association with the implementation of the SMC.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the distribution of respondent characteristics by the presence or absence of the SMC. Chi-square tests were performed to assess the relationship between each type of disability supported by the school and the adoption of the SMC. Additional chi-square tests were conducted to examine associations between the adoption of the SMC and individual items related to shelter and facility preparedness. Descriptive statistics were used to provide a basic summary of the sample. The chi-square test was chosen as it is a suitable method for analyzing associations among variables (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). Two groups were used to simplify the analysis and clearly distinguish between affirmative and negative responses. For shelter preparedness items, all responses of “Not sure” were grouped with “No.” This was based on the rationale that, from a disaster preparedness perspective, a state of uncertainty (“Not Sure”) is functionally equivalent to a lack of preparedness (“No”). For the question on interaction with local residents, all frequencies of contact (“Once a year,” “Twice a year,” “Three times a year,” “Four times a year,” and “Five or more times a year”) were grouped as “Yes.” For the question about considering challenges when enrolled children are mixed with temporary evacuees, the response “Never considered” was grouped with “No.” Regarding local residents’ understanding of enrolled children, “Fully understand” and “Understand” were combined as “Understand,” while “Do not understand well” and “Hardly understand” were combined as “Do not understand.”

For equipment and supply-related items, all responses of “Not sure” were grouped with “No.” For the question “Is there a storage warehouse for supplies on the school premises?,” the response “Located off school premises” was considered “Yes.” For the question “Is there a stockpile of drinking water?,” the responses “Bottled water available,” “Seismic-resistant water tanks or pool purification systems available,” “Well available,” and “Drinking water secured through agreements, etc.” were considered “Yes.” For the question “Is power secured in the event of a blackout?,” the responses “Own power generation equipment available” and “Priority use of power generation equipment through agreements, etc.” were grouped as “Yes.” For the question “Is communication secured in case of communication failure?,” the responses “Equipment capable of two-way communication available” and “Equipment capable of one-way communication only available” were combined as “Yes.” For the question “Is toilet availability secured during water outage?,” the responses “Portable toilets available,” “Manhole toilets available,” and “Toilets that can use pool or rainwater for flushing during water outage secured” were grouped as “Yes.” For the question “Is equipment such as liquefied petroleum (LP) gas available for use during disasters?,” the responses “Priority use of LP gas equipment, etc.” and “Equipment using cassette stoves, firewood, pellets, or other fuels available” were grouped as “Yes.”

To comprehensively evaluate the relationship between adoption of the SMC and shelter and facility preparedness, a backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed using SMC as the dependent variable and the 14 items in Table 4 and Table 5 as the independent variables. The dependent variable was defined as “adoption of SMC,” and the forced entry method was used to assess the influence of all selected variables. Chi-square tests and logistic regression analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with the significance level set at 5%. This statistical model was selected because the dependent variable was binary (i.e., implementation or non-implementation of the SMC). First, the stepwise method (backward elimination) was used to select significant variables. Next, these selected variables were entered into the final model using the forced entry method, and their overall influence was analyzed (Table 6).

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Attributes

As summarized in Table 1, 71.3% of the respondents were principals or vice-principals, 78.6% were men, and 63.9% reported no prior disaster experience (a figure that rose to 87.9% when combined with those who had experienced a disaster without evacuating). The mean length of service at special needs schools was 21.09 years.

Table 1.

Respondents’ sociodemographic and disaster background.

Table 1.

Respondents’ sociodemographic and disaster background.

| Question | Response | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your job title? | Principal | 216 | 40.2 |

| Vice-principal | 167 | 31.1 | |

| Chief of education | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Chief teacher | 36 | 6.7 | |

| Chief health officer | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Chief of disaster prevention/teacher | 54 | 10.1 | |

| Teacher | 26 | 4.8 | |

| School health teacher | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Sub-principal | 27 | 5.0 | |

| Other than those above | 4 | 0.7 | |

| What is your gender? | Man | 422 | 78.6 |

| Woman | 115 | 21.4 | |

| Have you ever experienced the effects of a natural disaster? | I have never had to evacuate | 343 | 63.9 |

| Despite the disaster, I have never been evacuated | 129 | 24.0 | |

| I have temporarily evacuated to an evacuation center | 23 | 4.3 | |

| I have lived in an evacuation center | 6 | 1.1 | |

| I have experience with shelter management at my school | 36 | 6.7 |

3.2. Relationship Between SMC Adoption and Disaster Preparedness

Students ranged from kindergarten to high school students, with intellectual and physical disabilities being the most commonly supported types (Table 2). Regarding the adoption of the SMC, 23.1% of the schools reported having implemented it (Table 2).

Table 2.

School profile and SMC adoption status.

Table 2.

School profile and SMC adoption status.

| Question | Response | Frequency | Percentage of Responses (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the current status of the infants and students enrolled at the school where you work? 1 | Kindergarten | 96 | 17.9 |

| Elementary school | 459 | 85.5 | |

| Junior high school | 453 | 84.4 | |

| High school | 470 | 87.5 | |

| What type of disability do students enrolled at your current school have? 1 | Visual impairment | 65 | 12.1 |

| Hearing impairment | 73 | 13.6 | |

| Intellectual disability | 371 | 69.1 | |

| Physical handicap | 176 | 32.8 | |

| Valetudinarian/physical weakness | 82 | 15.3 | |

| Other | 4 | 0.7 | |

| Has your school adopted the SMC? | Yes | 124 | 23.1 |

| No | 413 | 76.9 |

1 Multiple responses available. Percentages are based on the total number of respondents (N = 537).

No significant differences were found between the types of disabilities supported and adoption of the SMC. This may be because some special needs schools accommodate multiple disability types, while others do not (Table 3).

Table 3.

SMC adoption by disability type.

Table 3.

SMC adoption by disability type.

| Response | Total | Yes | No | χ2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual impairment | 65 | 100.0% | 16 | 24.6% | 49 | 75.4% | 0.097 | 0.756 |

| Hearing impairment | 73 | 100.0% | 21 | 28.8% | 52 | 71.2% | 1.533 | 0.216 |

| Intellectual disability | 371 | 100.0% | 90 | 24.3% | 281 | 75.7% | 0.921 | 0.337 |

| Physical handicap | 176 | 100.0% | 48 | 27.3% | 128 | 72.7% | 2.578 | 0.108 |

| Valetudinarian/physical weakness | 82 | 100.0% | 17 | 20.7% | 65 | 79.3% | 0.303 | 0.582 |

3.2.1. Shelter Preparedness Measures

Significant differences were observed for the following items (Table 4):

- Whether the current school is designated as a welfare evacuation shelter (p = 0.003);

- Whether preparations have been made to accept primary evacuees other than infants, children, and students (p = 0.002);

- Whether drills or training exercises assuming shelter use have been conducted (p < 0.001);

- Whether roles and responsibilities have been established with the municipal disaster management department (p < 0.001);

- Whether challenges associated with mixing enrolled children and temporary evacuees have been considered (p = 0.014).

Table 4.

Association between SMC adoption and disaster preparedness status.

Table 4.

Association between SMC adoption and disaster preparedness status.

| Question | Response | Frequency N = 537 | Yes n = 124 | No n = 413 | χ2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. Is your current school designated as a welfare evacuation shelter? | Yes | 167 | 52 | 41.9% | 115 | 27.8% | 8.836 | 0.003 |

| No | 370 | 72 | 58.1% | 298 | 72.2% | |||

| Q2. Are you prepared to accept primary evacuees other than infants, children, and students (e.g., local residents)? | Yes | 204 | 62 | 50.0% | 142 | 34.4% | 9.874 | 0.002 |

| No | 333 | 62 | 50.0% | 271 | 65.6% | |||

| Q3. Do you have interactions or exchanges with local residents? | Yes | 472 | 103 | 83.1% | 369 | 89.3% | 3.537 | 0.060 |

| No | 65 | 21 | 16.9% | 44 | 10.7% | |||

| Q4. Do you conduct drills or training exercises assuming the school becomes an evacuation shelter? | Yes | 84 | 32 | 25.8% | 52 | 12.6% | 12.623 | <0.001 |

| No | 453 | 92 | 74.2% | 361 | 87.4% | |||

| Q5. Have you established roles and responsibilities with the municipal disaster management department for emergencies? | Yes | 178 | 57 | 46.0% | 121 | 29.3% | 11.959 | <0.001 |

| No | 359 | 67 | 54.0% | 292 | 70.7% | |||

| Q6. Have you considered challenges that may arise when enrolled children are mixed with temporary evacuees? | Yes | 247 | 69 | 55.6% | 178 | 43.1% | 6.043 | 0.014 |

| No | 290 | 55 | 44.4% | 235 | 56.9% | |||

| Q7. To what extent do you think local residents understand the enrolled children? | Yes | 304 | 68 | 54.8% | 236 | 57.1% | 0.206 | 0.650 |

| No | 233 | 56 | 45.2% | 177 | 42.9% | |||

3.2.2. Equipment and Resource Preparedness

Significant differences were found for having a storage warehouse for supplies on school premises and securing toilet facilities during water outages (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between SMC adoption and equipment preparedness status.

Table 5.

Association between SMC adoption and equipment preparedness status.

| Question | Response | Frequency N = 537 | Yes n = 124 | No n = 413 | χ2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8. Is there a storage warehouse for stockpiles on the school premises? | Yes | 290 | 95 | 76.6% | 195 | 47.2% | 33.179 | <0.001 |

| No | 247 | 29 | 23.4% | 218 | 52.8% | |||

| Q9. Is there a stockpile of drinking water? | Yes | 492 | 117 | 94.4% | 375 | 90.8% | 1.571 | 0.210 |

| No | 45 | 7 | 5.6% | 38 | 9.2% | |||

| Q10. Is power supply secured in the event of a blackout? | Yes | 359 | 82 | 66.1% | 277 | 67.1% | 0.038 | 0.845 |

| No | 178 | 42 | 33.9% | 136 | 32.9% | |||

| Q11. Is communication ensured in case of communication failures? | Yes | 176 | 47 | 37.9% | 129 | 31.2% | 1.925 | 0.165 |

| No | 361 | 77 | 62.1% | 284 | 68.8% | |||

| Q12. Are toilet facilities secured during water outages? | Yes | 298 | 85 | 68.5% | 213 | 51.6% | 11.126 | <0.001 |

| No | 239 | 39 | 31.5% | 200 | 48.4% | |||

| Q13. Are facilities such as LP gas available for use during disasters? | Yes | 272 | 69 | 55.6% | 203 | 49.2% | 1.608 | 0.205 |

| No | 265 | 55 | 44.4% | 210 | 50.8% | |||

| Q14. Are food and supplies stocked for all enrolled infants, children, and students to stay overnight at school, assuming a situation with power outage, water outage, and communication failures from after school until breakfast the next day? | Yes | 373 | 94 | 75.8% | 279 | 67.6% | 3.061 | 0.080 |

| No | 164 | 30 | 24.2% | 134 | 32.4% | |||

3.3. Logistic Regression Results on Preparedness Factors

Two items—establishing roles and responsibilities with the municipal disaster management department (Q5) and having a storage warehouse for supplies on school premises (Q8)—were strongly associated with SMC adoption (Table 6). The odds ratio indicated that schools with an SMC were 3.321 times more likely to have a storage warehouse for supplies on the premises (Q8) and 1.714 times more likely to have established roles and responsibilities with the municipal disaster management department (Q5), compared to schools without an SMC.

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of SMC adoption and disaster preparedness.

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of SMC adoption and disaster preparedness.

| Question | Β | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits of Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Q4. Do you conduct drills or training exercises assuming the school becomes an evacuation shelter? | 0.361 | 0.212 | 1.434 | 0.814 | 2.528 |

| Q5. Have you established roles and responsibilities with the municipal disaster management department for emergencies? | 0.539 | 0.022 | 1.714 | 1.080 | 2.721 |

| Q8. Is there a storage warehouse for stockpiles on the school premises? | 1.200 | <0.001 | 3.321 | 2.033 | 5.425 |

| Q10. Is power supply secured in the event of a blackout? | −0.420 | 0.077 | 0.657 | 0.413 | 1.046 |

| Q12. Are toilet facilities secured during water outages? | 0.275 | 0.257 | 1.317 | 0.818 | 2.118 |

| Constants | −2.111 | <0.001 | 0.121 | ||

Model: χ2 = 49.343, p < 0.001; Hosmer–Lemeshow test: chi-square = 3.461, p-value = 0.839; accuracy rate: 76.5%.

4. Discussion

Although only 23.1% of special needs schools have implemented the SMC, the results suggest its effectiveness in disaster risk reduction. If the MEXT were to adopt a disaster risk reduction perspective, more special needs schools might introduce the system, potentially enhancing overall disaster preparedness.

4.1. Compensating for Teachers’ Lack of Shelter Experience

Collaboration with local residents is essential when operating evacuation shelters. However, 87.9% of teachers reported that they had no prior experience of living in evacuation shelters. Without such experience, teachers may struggle to anticipate the supplies and challenges involved in shelter operations.

The chi-square test showed that schools with the SMC had a significantly higher proportion of respondents indicating preparedness for accepting evacuees other than infants, children, and students (Q2) and consideration of challenges arising when enrolled children and temporary evacuees are mixed (Q6), compared with schools without the system (Table 4). The SMC offers a platform for teachers to engage with local residents, thereby compensating for their lack of shelter experience. By incorporating residents’ perspectives, preparedness can be enhanced. Although conducting drills assuming the school becomes an evacuation shelter (Q4) showed a significant difference in the chi-square test (Table 4), this item was not statistically significant in the logistic regression model (Table 6). Nevertheless, special needs schools with the SMC can engage in planning, drills, and coordination for temporary evacuees while incorporating input from residents through the SMC. In this way, the SMC helps bridge the experience gap in disaster preparedness among teachers.

4.2. Enhancing Welfare Shelter Function Through Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

The designation of a school as a welfare evacuation shelter (Q1) was significantly associated with the adoption of the SMC in the chi-square tests. Such designations are based on legal frameworks [3,17,18] outlining the responsibilities of national and local governments and requiring the provision of safe environments for vulnerable individuals. When a special needs school is designated as a welfare shelter, it works in coordination with municipal authorities familiar with the community’s needs.

The item on whether roles and responsibilities have been established with the municipal disaster management department for emergencies (Q5) was also statistically significant in the chi-square tests. This factor demonstrated a strong influence in the logistic regression analysis, with an odds ratio of 1.714. The item regarding the presence of a storage warehouse on the school premises (Q8) yielded the highest odds ratio at 3.321, indicating the strongest association with the adoption of the SMC, followed by the aforementioned factor. Although various organizations operate within communities, the World Health Organization’s [19] Strategic Framework for Emergency Preparedness emphasizes that “effective emergency preparedness can only be achieved with the active participation of local governments, civic society organizations, local leaders, and individual citizens.”

The SMC strengthens both community resilience and social capital through these connections. Prior studies have highlighted the important role of schools in fostering social capital for resilience [20]. One study on school resilience following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake emphasized strengthening ties between schools and communities through three actions: involving communities in school activities, participating in community association initiatives, and collaborating on joint activities [21]. When roles are clarified in advance through the SMC, the lives of disaster victims—including vulnerable persons evacuated to special needs schools—can be better protected. The SMC enhances the function of welfare shelters by fostering cooperation between schools, municipalities, and residents. Therefore, the results from the analysis of quantitative data obtained in our nationwide study support Shiwaku et al.’s [21] assertion that close collaboration and cooperation between schools and communities contribute to school resilience.

4.3. Infrastructure and Hygiene Preparedness Through Community–School Coordination

The presence of a stockpile warehouse on school premises (Q8) was a statistically significant predictor in both chi-square and logistic regression analyses, with an odds ratio of 3.321. This suggests a strong association between physical preparedness and adoption of the SMC. Establishing stockpiles reflects collaborative planning between schools and local communities. One study noted that “the provision of supplies, storage, and preservation of supplies, materials, and emergency equipment” contributes to disaster-resilient schools [22]. Through the SMC, stakeholders can discuss emergency equipment tailored to the needs of children with disabilities and determine the necessary quantity and dimensions of storage units. Based on the above, the supply and storage of goods and materials, necessary for the “disaster-resilient schools” proposed by Mirzaei et al. [22], can be achieved through a collaborative framework with local residents, such as the SMC. Thus, our study further develops insights from previous research.

The item on toilet availability during water outages (Q12) also showed a significant difference in the chi-square tests but was not statistically significant in logistic regression. The 2019 MEXT White Paper emphasized efforts to improve disaster education and strengthen school infrastructure [23]. Both teachers and residents appear to be aware of the importance of hygiene, and related drills are already being conducted. Indeed, restoring access to clean water and toilets after disasters is vital in preventing the spread of infectious diseases [24]. The Sphere Handbook notes that “containment of human excreta away from people creates an initial barrier to excreta-related disease by reducing direct and indirect routes of disease transmission” [25]. Children with disabilities are particularly vulnerable [26], and their caregivers and teachers understand the importance of maintaining hygiene. Therefore, securing toilet facilities is likely prioritized in preparedness planning. The SMC may contribute to improved shelter functionality and hygiene management.

The item on availability of power supply during blackouts (Q10) did not show significance in logistic regression analysis. Given Japan’s high disaster risk [27] and frequent power outages during typhoons, heavy rains, and snowstorms [28], preparedness for blackouts is likely routine among both schools and residents. Although the regression coefficient was negative, indicating no direct influence on the implementation of the SMC, this factor may still contribute to the initial stages of disaster planning.

4.4. Policy Recommendations for Advancing Disaster Preparedness Through the SMC

The MEXT advocates for the SMC as part of its initiative for “Promoting Learning in Local Communities,” incorporating the strengths of the local community into school management [29]. The Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education, as outlined by the national government, includes both the advancement of special needs education and the further promotion of the SMC [30].

As demonstrated in this study, introducing the SMC not only helps compensate for the lack of shelter experience among teachers and staff but also strengthens support for disaster victims through collaboration with local residents and municipal authorities. Furthermore, collaboration with local residents enhances schools’ preparedness for unforeseen events. The SMC is therefore considered to contribute to strengthening disaster preparedness in schools. However, it currently lacks an explicit disaster risk reduction perspective. As evidenced by the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, disasters can occur without warning and cause extensive damage beyond school boundaries. Therefore, if the MEXT were to integrate a disaster risk reduction perspective into the SMC, more special needs schools might adopt the system, thereby enhancing nationwide disaster preparedness.

Despite its merits, this study has certain limitations: the number of participating schools was limited owing to the use of a self-administered questionnaire; the specific characteristics of each school based on geographical location were unknown as the survey was conducted anonymously; and the data were collected in 2020, which means that our findings may not necessarily capture subsequent changes in national educational policy. Nevertheless, our study provides valuable data on the preparedness for disaster risk reduction in Japanese special needs schools.

5. Conclusions

We examined the relationship between SMC adoption and disaster preparedness in special needs schools. The results showed that 23.1% of special needs schools had adopted the system. Logistic regression analysis identified two items significantly associated with adoption: the concerned municipal department approves the clearly delineated roles and responsibilities for disasters and the presence of a stockpile warehouse on school premises. These findings suggest that adoption of the SMC may enhance disaster risk reduction efforts. The key finding of this study is the significant association between the adoption of the SMC and two specific preparedness items: the presence of a stockpile warehouse and having established roles with the municipality.

The findings are meaningful in that they extend prior results, that disaster countermeasures are promoted when special needs schools are designated as welfare evacuation shelters by considering the role of the SMC.

Furthermore, a major contribution of our study is the revelation that, in addition to physical “hard” preparedness, a “soft” mechanism promoting collaboration between schools and local residents—namely, the SMC—is effective for disaster preparedness. This finding, which highlights the importance of collaboration between schools and the community during normal times, offers valuable insights for all school stakeholders aiming to protect the lives of both children and local residents in the event of a disaster.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and H.T.; methodology, H.K., S.Y. and H.T.; validation, H.K., S.Y. and H.T.; formal analysis, H.T., H.K. and S.Y.; investigation, H.K. and S.Y.; data curation, H.K., S.Y. and H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, H.K., H.T. and S.Y.; supervision, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Program (KAKENHI), Japan, grant number 17H04467.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Epidemiology of HIROSHIMA UNIVERSITY (approval number: E-2224; date of approval: 12 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Responding to the survey was considered an indication of informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those involved in the special needs schools that participated in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMC | School Management Council |

| MEXT | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology |

| LP | liquefied petroleum |

References

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response; Sphere Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 251. Available online: https://spherestandards.org/handbook-2018/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- UNDRR. PreventionWeb: Building Safer and More Resilient Schools in a Changing Climate. 2024. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/news/building-safer-and-more-resilient-schools-changing-climate (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Japanese Law Translation. Basic Act on Disaster Management (Act No. 223 of 1961), Articles 8-2(xv) and 49-7 (Designation of Designated Shelters). Last Version: Act No. 36 of 2021. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/4171 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Cabinet Office. Guidelines for Securing and Operating Welfare Evacuation Shelters. Revised in May 2021. p. 12. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/taisaku/hinanjo/pdf/r3_hinanjo_guideline.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024). (In Japanese)

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. All Under One Roof: Disability-Inclusive Shelter and Settlements in Emergencies; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 94. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/All-under-one-roof_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo Metropolitan Government Disaster Prevention Guidebook; Tokyo Metropolitan Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; p. 20. Available online: https://www.bousai.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/content/e_book_04/guide-english/pdf/guide-english.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Kawasaki, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Murata, Y.; Iwasa, M.; Teramoto, C. Teacher-parents cooperation in disaster preparation when schools become evacuation centers. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020, 44, 101445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, R.; Şahinöz, S. The experiences of people with disabilities in the 2020 Izmir earthquake: A phenomenological research. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrati, A.; Bardin, S.; Mann, D.R. Spatial distributions in disaster risk vulnerability for people with disabilities in the U.S. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 87, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. Modality and Promotion Policies Between Schools and Communities for Education in a New Era and Towards Realizing Regional Revitalization (Key Points). 2015. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/news/topics/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2016/12/06/1380270_001.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- US Department of Education. What is a Charter School? Available online: https://charterschoolcenter.ed.gov/what-charter-school (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Korea Legislation Research Institute. Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Act No. 19740, 2023. Establishment of School Governance Committees, Article 31. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=64084&lang=ENG (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Nagata, T.; Kimura, R. Developing a disaster management education and training program for children with intellectual disabilities to improve “zest for life” in the event of a disaster—A case study on Tochigi Prefectural Imaichi Special School for the Intellectually Disabled–. J. Disaster Res. 2020, 15, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, H.; Cui, Z.; Kurokawa, M.; Sonai, K. Current situation of disaster preparedness for effective response in Japanese special needs schools. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. School Code List. 2024. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/mext_01087.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Japanese)

- Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Welcome to GSI. Available online: https://www.gsi.go.jp/ENGLISH/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Japanese Law Translation. Order for Enforcement of the Basic Act on Disaster Management (Cabinet Order No. 288 of 1962), Article 20-6-iv (Standards of Designated Shelters). Last version: Cabinet Order No. 153 of 2021. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/4172 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Japanese Law Translation. Regulation for Enforcement of the Basic Act on Disaster Management (Prime Minister’s Office Order No. 52 of 1962), Articles 1-7-2 (Standard as Specified by Cabinet Office Order Set Forth in Article 20-6 of the Order) and 1-9 (Standard as Specified by Cabinet Office Order Set Forth in Article 20-6 of the Order). Last Version: Cabinet Office Order No. 30 of 2021. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/4173 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. A Strategic Framework for Emergency Preparedness; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 4. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/a-strategic-framework-for-emergency-preparedness (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Mutch, C. How schools build community resilience capacity and social capital in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 92, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwaku, K.; Ueda, Y.; Oikawa, Y.; Shaw, R. School disaster resilience assessment in the areas affected by the 2011 East Japan earthquake and tsunami. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Dehghani Tafti, A.A.; Mohammadinia, L.; Nasiriani, K.; Rahaei, Z.; Falahzadeh, H.; Amiri, H.R. Operational strategies for establishing disaster-resilient schools: A qualitative study. Adv. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 4, e23. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. Chapter 13: Enhancing Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Measures. In White Paper on Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technology, Part II: Trends and Development in Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Policies; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://warp.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/13731853/www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/hakusho/html/hpab201801/detail/1420041_00011.htm (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Akaishi, T.; Morino, K.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishibashi, S.; Takayama, S.; Abe, M.; Kanno, T.; Tadano, Y.; Ishii, T. Restoration of clean water supply and toilet hygiene reduces infectious diseases in post-disaster evacuation shelters: A multicenter observational study. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sphere Association. The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response; Sphere Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 113. Available online: https://spherestandards.org/handbook-2018/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Mann, M.; McMillan, J.E.; Silver, E.J.; Stein, R.E.K. Children and adolescents with disabilities and exposure to disasters, terrorism, and the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Director General for Disaster Management. Disaster Management in Japan: Pamphlet. 2021. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/1info/pdf/saigaipamphlet_je.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Cabinet Office. White Paper on Disaster Management 2023. 2023; pp. 49–57. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/en/documentation/white_paper/pdf/2023/R5_hakusho_english.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. Overview of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology: Promoting Learning in Local Communities. 2019; p. 7. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/about/pablication/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2019/03/13/1374478_001.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Cabinet Office. Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education. Cabinet Decision. 2023; pp. 75–86. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/lawandplan/20240311-ope_dev03-1.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).