Abstract

This paper presents a comparative analysis of pedestrian behavior and perceived safety among university students at two signalized intersections near the campus premises of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. Although both intersections include pedestrian crosswalks and traffic lights, one permits vehicle left turns during pedestrian phases via flashing yellow arrows, while the other restricts all vehicle movement. Two questionnaire-based surveys (n1 = 304 and n2 = 303) recorded demographic information, crossing behavior, perceived risk, and preferred safety interventions. Results indicate that the intersection permitting vehicle conflict is associated with significantly lower levels of perceived safety and higher instances of risk-taking, such as crossing “at any time”. Conversely, the vehicle-restricted intersection fosters greater compliance with pedestrian signals and a stronger sense of security. Key factors influencing crossing decisions included vehicle speed, signal duration, pedestrian group presence, and urgency. Respondents prioritized safety improvements such as pedestrian countdown timers, enhanced signage, and enforcement cameras. These findings underscore the critical role of signal phasing in shaping pedestrian behavior and safety perceptions. Evidence-based recommendations are offered to urban planners and policymakers to enhance pedestrian safety through targeted infrastructure upgrades and enforcement strategies.

1. Introduction

Pedestrian safety at signal-controlled crossings is a perennial challenge in urban areas, especially around academic campuses where students, faculty, and staff converge in large numbers. Although traffic signals are intended to organize the movement of pedestrians and vehicles, their effectiveness hinges on factors such as signal timing, crossing design, and the behavior of both drivers and walkers.

A critical risk occurs when motorists run red lights, exposing pedestrians to life-threatening conflicts. Equally problematic is an insufficient pedestrian “green” interval: in high-density settings, a short walk phase can leave individuals stranded mid-crossing or force them to dash against oncoming traffic. The simultaneous flow of pedestrians and vehicles—particularly during class-change rush hours—further compounds these hazards.

University students form a distinct pedestrian group. Their routine trips between lecture halls, dormitories, and campus facilities often involve crossing busy streets under time pressure and distraction from mobile devices. Meanwhile, drivers familiar with the urban road network may become complacent or aggressive, neglecting speed limits and signal compliance. To mitigate these risks, a combination of infrastructure upgrades (e.g., extended signal timing, high-visibility crosswalks) and behavior-change initiatives (e.g., targeted awareness campaigns) is essential.

In Greece, 2022 road-safety statistics underscore the urgency of such measures: of 654 total traffic fatalities, pedestrians accounted for 112 deaths (17.1%) [1]. Although senior citizens represented the majority of these pedestrian fatalities, the data highlight the broader vulnerability of individuals on foot—nearly 15% of all crashes involved pedestrians, with residential zones and two-wheeled vehicles posing particularly high risks.

This paper examines how students perceive and navigate risks at two signalized crossings near Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh) in Greece. A field survey administered in January–February 2025 gathered qualitative insights (e.g., perceived danger, crossing patterns) during peak traffic periods.

The findings reveal significant gaps in signal timing, visibility, and rule enforcement, and suggest that behavioral interventions are as crucial as physical upgrades. The recommend measures concern optimizing walk-phase durations, enhancing lighting and signage, and implementing educational programs for both pedestrians and drivers. These measures aim to guide urban planners and policymakers in developing safer, more walkable near campus zones.

Building on prior theories and empirical findings related to pedestrian behavior, traffic signal phasing, and perceived safety, this study offers several innovative contributions. Unlike previous research predominantly focusing on general pedestrian safety or isolated behavioral aspects, our study uniquely examines how specific signal phasing characteristics influence university students’ crossing decisions and their confidence levels. By integrating behavioral analysis with perceived risk assessment at two distinct types of signalized intersections, the research fills a notable gap in understanding the real-time interaction between signal control strategies and pedestrian decision-making. Moreover, the incorporation of situational context—such as vehicle left-turn permissions during pedestrian phases—advances existing conceptual models by highlighting nuanced effects of traffic control design on safety perception and crossing behavior. These insights provide novel empirical evidence with practical implications for designing pedestrian-friendly signal systems, especially in educational campus environments

2. Literature Review

The literature review was conducted using the SCOPUS database with the search item “TITLE-ABS-KEY (pedestrian AND safety AND signalized AND intersection) AND PUBYEAR > 2009 AND PUBYEAR < 2026” returning 344 publications spanning 2018–2025. The number of documents remained relatively stable from 2019 to 2021, hovering around 41–44 documents. There was a notable upward trend from 2021 to 2024, with document counts steadily increasing and peaking at 65 in 2024. However, in 2025, there is a sharp decline in the number of documents, bringing it back to the levels seen in 2019 and 2021.

China (100 papers) and the United States (99 papers) are the leading contributors, significantly outpacing all other nations. India follows as a distant third with 44 papers. The remaining countries contribute much smaller numbers, with a large majority having 5 or fewer papers (Greece contributes with 6 papers), and 21 countries contributing only 1 paper each. This indicates that a substantial portion of the documents originate from just a few key regions, while many other countries have minimal contributions.

2.1. Geometric Design and Infrastructure Factors

Research in this category examines how road geometry, crossing design, and signal phasing directly impact pedestrian safety at signalized intersections. Stipancic et al. (2020) [2] through their research indicated a positive correlation between pedestrian and vehicle volumes and pedestrian injuries. Specific geometric features like curb extensions, raised medians, and exclusive left-turn lanes were found to reduce pedestrian injuries. Conversely, an increase in the total number of lanes and commercial entrances was associated with an increase in injuries. Jiang et al. (2020) [3] found that channelized right-turn lanes generally increase pedestrian risks at signalized intersections across various safety dimensions. These lanes can increase risks by bringing pedestrian–vehicle interactions into a non-signalized environment and by potentially leading to higher vehicle speeds due to increased turning radii. Arafat et al. (2025) [4] investigated pedestrian and motorist decision-making and safety on unsignalized slip lanes (also known as channelized right-turn lanes in right-hand driving countries). These lanes are common at signalized intersections to facilitate turning movements, but their impact on pedestrian safety is not well understood. The complexity arises from the joint decision-making process between pedestrians and motorists at these uncontrolled crossing points. Their research identified factors influencing yielding behavior and conflict risk, such as vehicle arrival rate, pedestrian volume, and driver characteristics. This approach provides valuable insights into pedestrian safety on slip lanes, which can inform design and operational improvements. He et al. (2019) [5] analyzed the specific conflicts involving left-turning vehicles and pedestrians. The research highlighted the common occurrence of these conflicts when traffic lights change, suggesting that while traffic lights are intended to manage flow, they also create complex interaction scenarios. Their research findings contribute to understanding the dynamics of these conflicts, providing insights into improving road safety at signalized intersections by considering the specific risks posed by left-turning vehicles to pedestrians. Hasanpour et al. (2025) [6] focused on developing Safety Performance Functions (SPFs) for pedestrian crashes at signalized intersections by integrating traffic conflict frequency and severity indicators. This approach aimed to provide a more robust method for estimating pedestrian crash risk, especially in situations with limited crash data. Marisamynathan & Vedagiri (2020) [7] proposed a methodology to evaluate crosswalk safety at signalized intersections, particularly under mixed traffic conditions, using Surrogate Safety Measures (SSM). Gitelman et al. (2020) [8] investigated the effects of a Leading Pedestrian Interval (LPI) signal phase on pedestrian crossing behaviors and safety at signalized urban intersections. Signalized intersections are identified as high-risk locations for pedestrians, and the LPI is a countermeasure designed to enhance pedestrian visibility and reduce conflicts with turning vehicles by giving pedestrians a head start before parallel vehicular traffic receives a green light. Ge et al. [9] and Typa et al. [10] demonstrated through observational studies at signalized intersections how texting, web-surfing, and phone conversations substantially increase risk-taking behaviors. Houten and DeLaere [11], and Do et al. [12] examined countdown timer implementations, finding both benefits for pedestrian decision-making and unintended consequences including increased driver aggression during yellow phases, highlighting the need for comprehensive system design approaches. Lalwani et al. (2021) [13] focused on quantifying the safety risk associated with conflicts between free left-turning vehicles and pedestrians at signalized intersections. The research utilized Post-Encroachment Time (PET) as a surrogate safety measure to assess these conflicts. The researchers analyzed various parameters, including pedestrian volume, classified vehicle volume, speeds of vehicles and pedestrians, pedestrian waiting time, lag/gap time, and PET values. A linear regression model showed a positive correlation between pedestrian volume and the total number of conflicts. Furthermore, conflict severity was categorized based on PET values, revealing that approximately 25-45% of observed conflicts at both locations fell into the severe category.

2.2. Pedestrian and Driver Behavior

Mukherjee & Mitra (2019) [14] identified several contributing factors to pedestrian violation, including longer waiting times, higher pedestrian–vehicle interaction, pedestrian’s state of crossing (e.g., carrying overhead loads, being distracted), and personal attributes like intended mode of transportation, home location, and socio-demographic characteristics. Do et al. (2023) [12] through their research analyzed driver behavior using a dataset of 827,000 drivers and over 1 million time-stamped vehicle locations from 15 intersections in Quebec, QC, Canada, collected between 2017 and 2019. The study focused on stop/go decisions at the onset of a yellow light, particularly during the dilemma zone (the area where a driver might struggle to decide whether to stop or proceed safely). Findings revealed that drivers were more likely to run yellow lights at intersections with Pedestrian Countdown Signals (PCS). This effect was more pronounced in the later stages of the yellow light phase and when the remaining time on the countdown timer was low. The study highlights that the unintended visibility of PCS information to drivers can lead to more aggressive driving behavior, potentially increasing the risk of red-light running and crashes. Abu Khuzam et al. (2025) [15] analyzed the unexpected interactions it creates between pedestrians and drivers and by modeling these interactions, they derived reward functions, which provide insights into their behaviors, and optimal policies, representing the best sequences of decisions for both road user types. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the risks associated with jaywalking and offer a foundation for developing more effective countermeasures to enhance safety at signalized intersections. Rafe et al. (2025) [16] investigated pedestrian non-compliant crossing behaviors, specifically focusing on spatial violations (crossing outside marked crosswalks) and temporal violations (crossing against the signal). Using a comprehensive dataset of 5589 pedestrian crossing events at 47 crosswalks across 39 intersections in Utah (U.S.A.), the research employed multilevel regression models to identify the factors influencing these violation behaviors. The key findings indicated that both individual characteristics (e.g., gender, use of mobility devices) and environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, time of day) play a significant role in influencing whether pedestrians commit spatial or temporal violations. Additionally, social dynamics, such as the presence of other pedestrians, also impact these behaviors. The study provides valuable insights into the complex factors driving pedestrian crossing decisions, which can inform strategies aimed at improving pedestrian safety and compliance at signalized intersections. Dhoke & Choudhary (2024) [17] investigated how time pressure influences pedestrian compliance behaviors (temporal and spatial) at signalized intersections. Pedestrian non-compliance, such as hurrying and engaging in unsafe behaviors like red-light running or crossing outside crosswalks, poses a significant safety risk. Their key findings indicated from this simulator research provide insights into how time pressure and other factors contribute to unsafe pedestrian behaviors, which can inform strategies for improving pedestrian safety at signalized intersections. Sahu et al. (2025) [18] proposed a new theory and methodology aiming to provide a more robust and accurate way to identify high-risk situations and inform the development of targeted countermeasures to enhance pedestrian safety, using AI-based video analysis. Guo et al. (2019) [19] investigated the characteristics of pedestrian red-light running behavior, specifically focusing on two-stage crossings at signalized intersections. While two-stage crossings are important for pedestrian safety and efficiency, the authors noted that research on red-light violations in such contexts has been limited, proposing a goal-oriented and time-driven red-light violation behavior model for pedestrian two-stage crossings, offering valuable insights into understanding and addressing pedestrian non-compliance at signalized intersections. Haque et al. (2024) [20] investigated pedestrian safety behavior at urban signalized T-intersections, which are common but often pose safety challenges due to complex vehicle–pedestrian interactions. The research aimed to understand various aspects of pedestrian behavior, including compliance with signals and use of marked crosswalks, and how these behaviors impact safety. The authors concluded that crossing speed was not a significant factor in safety, while waiting time varies significantly across different gender and age groups. A concerning finding was that very few pedestrians exhibit entirely safe or even partially safe crossing behaviors. Finally, time-saving and personal convenience, followed by perceived low traffic, are the primary reasons for unsafe crossings, highlighting that both pedestrian psychology and traffic conditions equally contribute to these behaviors. Krishnan & Marisamynathan (2023) [21] through their research acknowledged that pedestrians are highly vulnerable road users and that their diverse and complex crossing behaviors significantly influence their perceived safety. The researchers identified variations in pedestrian crossing behavior based on socio-economic variables, travel attributes, and existing pedestrian and traffic characteristics. Zhou et al. (2019) [22] investigated how mobile phone use affects pedestrian behavior at signalized intersections in Nanjing, China. Observing 4196 pedestrians, the research found that phone users, particularly young individuals, exhibit significantly riskier crossing behaviors—such as crossing on red lights, walking more slowly, and failing to observe traffic. Age significantly influences phone use, while gender does not. The study suggested improving public awareness, adjusting signal timings, and implementing technology-based interventions to enhance pedestrian safety. De Pauw et al. (2015) research [23], comes outside the SCOPUS database research and time period, examined the safety impact of implementing protected left-turn phasing at signalized intersections on highways in Flanders, Belgium. Using an Empirical Bayesian before-and-after design, the researchers analyzed crash data at 103 intersections, 33 of which had only signal control changes and 70 with additional modifications. The introduction of protected left-turn signals led to a 46% reduction in injury crashes, primarily due to a 60% decrease in left-turn collisions, with no significant change in rear-end crashes. The most substantial safety gains were observed for severe crashes (66% reduction). Casualty-level analysis further indicated notable improvements across all road-user groups, including cyclists and motorcyclists. Sherif et al. (2025) [24], in a survey involving 5000 pedestrians across Central Florida, observed that distraction led to an average 4% increase in crossing time—comparable to the typical 2 s startup delay seen in drivers. They concluded that such distractions have minimal impact on the overall efficiency of intersection operations. Iryo Asano & Alhajyaseen (2017) [25] investigated abrupt changes in pedestrian speed at crosswalks in Nagoya, emphasizing their pivotal contribution to increasing the likelihood of conflicts with vehicles. Gruden et al. (2022) [26] used eye-tracking technology at signalized intersections to demonstrate how both smartphone usage and intersection layout notably influence pedestrians’ visual attention and decision-making during crossing. Perra et al. (2022) [27] found that factors such as age, spatial positioning, and exposure to potential conflicts significantly influenced the time distracted pedestrians took to cross streets in Thessaloniki. Wang et al. [28] and Krishna et al. [29] provided comprehensive analyses of distracted pedestrian behaviors using advanced behavioral modeling techniques. These findings complement Zhou et al. (2019) [22] who observed 4196 pedestrians in China, revealing that phone users exhibit significantly riskier behaviors including red-light running and reduced situational awareness.

2.3. Conflicts and Safety Performance Modeling

Xie et al. (2025) [30] focused on understanding sequential traffic conflicts at signalized intersections, particularly those involving left-turning vehicles. Due to complex interactions among vehicles, pedestrians, and non-motorized traffic, and frequent right-of-way violations, intersections often have numerous conflict points. Sequential conflicts, where road users encounter multiple risky situations in quick succession, can deplete attention and increase accident risk. Patra et al. (2020) [31] investigated the factors influencing pedestrians’ choices between at-grade signalized crosswalks and coexisting foot overbridges in Indian cities revealing that their usage rate is often low, leading to uneven utilization of crossing facilities and affecting pedestrian safety and mobility. Xiao et al. (2021) [32] investigated the factors influencing the severity of pedestrian injuries at signalized intersections, concluding that the complexities of unobserved factors and spatial attributes that can affect injury outcomes. Pan et al. (2022) [33] addressed the growing need to understand how autonomous vehicles (AVs) impact traffic efficiency and safety, especially when operating in mixed traffic flows alongside human-driven vehicles and pedestrians at signalized intersections. According to the authors, while AV field experiments are increasing, there is a recognized gap in evaluating their efficiency and conflicts with pedestrians in real-world scenarios. Thei research aimed to bridge this gap by developing a simulation model to specifically assess the efficiency and safety of left-turn (LT) vehicles and crossing pedestrians in signalized intersections under conditions where both human-driven and autonomous vehicles are present. Their analysis identified critical behavioral parameters such as gap/lag acceptance behavior and reaction time of LT vehicles, which significantly influence the efficiency and safety outcomes. Guo et al. (2024) [34] introduced a two-stage pedestrian crossing framework utilizing Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) integrated with fluid dynamics principles to model pedestrian velocity, density, and acceleration. Alhajyaseen and Nakamura (2010) [35] observed that the efficiency of signalized crosswalks is most compromised when pedestrian traffic is evenly split in both directions, leading to a notable reduction in overall capacity. Surrogate safety measures and conflict analysis have evolved significantly with Chen et al. [36] developing comprehensive frameworks for assessing pedestrian–vehicle conflicts using time-based metrics like Post-Encroachment Time (PET). Ivan et al. [37] evaluated these measures across various roadway environments, establishing validation protocols for video-based analysis systems that complement traditional crash data collection methods.

2.4. Technology and Automated Systems

Gavric et al. (2024) [38] investigates potential safety issues arising from incorrect pedestrian detection by automated systems (Automated Pedestrian Video Detection Systems). Advanced technological applications are revolutionizing pedestrian safety analysis through artificial intelligence and physics-informed modeling approaches. Lee et al. [39] and Guo et al. [34] pioneered Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) applications for predictive risk assessment, demonstrating how machine learning can incorporate physical laws governing pedestrian–vehicle interactions. Lévêque et al. [40] and Hochman et al. [41] employed eye-tracking technologies to understand visual attention patterns during crossing decisions, revealing how infrastructure design influences pedestrian gaze behavior and safety perception.

2.5. Vulnerable Groups and Socio-Demographics

Hu et al. (2022) [42] focused on the critical issue of pedestrian safety at urban signalized intersections, which are identified as high-risk areas due to complex vehicle–pedestrian interactions. The research emphasizes that understanding pedestrian–vehicle conflicts is essential for improving road safety, especially as traditional crash data collection can be limited. Juozevičiūtė & Grigonis (2022) [43] evaluated the safety performance of exclusive pedestrian phases at one-level signalized intersections in Vilnius (Lithuania). The study focused on intersections without diagonal crossing capabilities. It utilizes anonymized traffic accident data from the Lithuanian Police Department Accident Register to analyze the density of traffic accidents at 11 signalized intersections where this pedestrian phase was implemented. Deluka-Tibljaš et al. (2021) [44] conducted a comparative study analyzing the factors that influence children’s pedestrian behavior in the conflict zones of urban intersections, particularly near primary schools in Enna (Italy), and Rijeka and Osijek (Croatia). The researchers observed 900 children crossing at 18 signalized pedestrian crosswalks and found that crosswalk length, age, and group movement significantly affected children’s crossing speed. Additional factors—such as adult supervision, gender, distractions like mobile phone use, and running behavior—were influential in some locations but not universally. Notably, younger children (under 7) walked more slowly and unsafely, underlining their vulnerability. The study highlights the need for targeted infrastructural design and traffic education to safeguard young pedestrians across different urban contexts. Osuret et al. [45] examined child pedestrian crossing patterns, identifying developmental factors affecting risk perception and decision-making capabilities. At the other demographic extreme, Zhang et al. [46] investigated elderly pedestrian behavior, finding spatial-temporal violations and slower crossing speeds that create distinct safety challenges at signalized intersections, particularly relevant for campus environments where multiple age groups interact.

Table 1 summarizes the literature review into five (5) categories.

Table 1.

Literature review categorized into five (5) categories based on their research objectives (overlapping was not excluded).

3. Methodology

The key objective of this research is to examine how traffic signal phasing—specifically, exclusive pedestrian (“protected”) versus concurrent pedestrian–vehicle (“unprotected”) phases—shapes university students’ crossing behavior and perceived safety. To structure this inquiry, we pose three Research Questions: (RQ1) How do perceived safety levels differ between protected and unprotected intersections? (RQ2) Which factors—such as peer influence, basic traffic light cues, or vehicular speed and volume—most strongly drive crossing decisions under each phasing condition? (RQ3) What intervention strategies (e.g., enforcement cameras, enhanced markings, lighting improvements) do students prioritize at each intersection type? These research questions guided the design of our data collection instruments, sampling procedures, and analytical approach to ensure a focused investigation of the relationships among signal phasing, pedestrian perceptions, and safety intervention preferences.

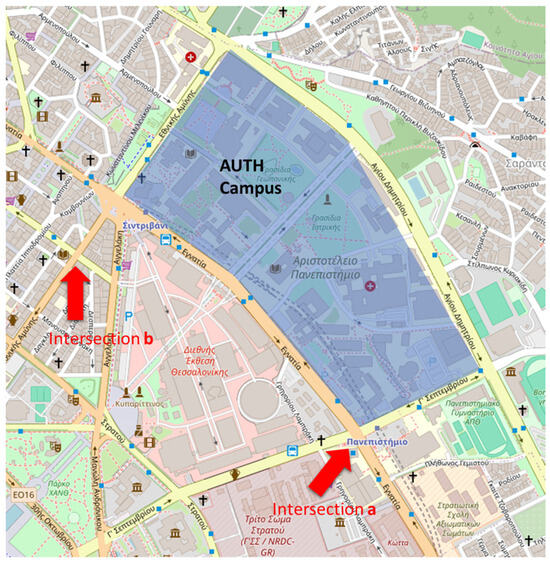

The two (2) in situ as well as the questionnaire-based surveys were implemented at the (a) the at-grade intersection of Egnatia and 3rd Septemvriou streets and (b) the at-grade intersection of Aggelaki and Al. Svolou streets, in the Municipality of Thessaloniki, Greece. The survey was disseminated to students of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki through departmental mailing lists, social media groups, and physical notices near the two signalized intersections examined in this study. A total of 607 valid responses were collected, corresponding to approximately 0.69% of the total student population.

Egnatia Street is one of the main horizontal (on parallel to the coastline) roads in the city of Thessaloniki, stretching across the city from east—southeast to west—northwest. It accommodates traffic with two lanes in each direction, supplemented by a dedicated bus lane on the right-hand side. A central median of varying width runs a small section of the street, separating opposing traffic flows. All intersections along the road are signalized, typically allowing right turns and, in some few cases, permitting left turns. Where allowed, left-turn maneuvers are managed through designated turning lanes and corresponding traffic signals. At the intersection in question, vehicles can execute left turns using a dedicated lane.

At the second intersection, left-turning vehicles is controlled by a flashing yellow arrows beside the green light on the traffic lights. According to the Greek Road Traffic Code (Law 2696/1999, as amended), ‘flashing arrows’ are covered by the provisions on vehicle light signals in Article 6, paragraph 1, subparagraphs (f)–(h) [47]. Specifically, “Yellow light with an arrow (steady or flashing): carries the same obligations as the circular yellow light. The driver is required to slow down, proceed with heightened caution, and yield priority to pedestrians and other vehicles” [47]. At the intersection there is also a pedestrian signal controlling their movements. Both intersections are presented in relation to the AUTh Campus premises in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of the under study at-grade intersections in the city of Thessaloniki in relation of the AUTh Campus premises using OpenStreetMap digital background [Source: Based on OpenStreetMap contributors. (2024)].

At these intersections, two members of each research team carried out a questionnaire-based survey exclusively targeting students of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh). The questionnaires (almost identical), specifically designed for this study, begin with a set of socio-demographic questions covering gender, age range, occupation, education level, and household income.

Following this, the surveys examine participants’ travel behavior, including their ownership or frequent use of private vehicles and how often they use pedestrian crosswalks. A core focus is placed on pedestrian practices at crossings—participants were asked whether they typically use designated crossing points and if they comply with traffic signals, such as crossing during a green light or engaging in risky behavior during a red signal. The questionnaires also explored perceptions of safety, including how secure individuals feel when crossing and whether upgrading the existing standard traffic light to an advanced system would enhance their sense of safety.

Moreover, the surveys evaluated multiple factors that may influence crossing decisions, such as vehicle speed, traffic volume, urgency to reach a destination, the presence of other pedestrians, and the functionality of the signaling system. Respondents were asked to rank these elements in terms of importance, offering valuable insights into the primary factors shaping pedestrian behavior.

The questionnaires further delved into perceived risks related to crossing, such as brief signal durations, drivers disobeying traffic lights, and shared space between vehicles and pedestrians. They also investigated types of pedestrian distractions—like mobile phone use, listening to music, or talking—and how these behaviors may compromise safety or encourage riskier choices.

In its concluding sections, the surveys assessed opinions on potential safety enhancements, including improved lighting, clearer road signage, reduced speed limits, and the installation of enforcement cameras. Participants were invited to prioritize these interventions and identify the most critical hazards encountered during road crossings. In total, the questionnaire comprises six questions focused on demographic data and 14 questions addressing perceived crossing risks. At intersection (a), 303 in total questionnaires were collected while at intersection (b), 304 questionnaires were collected. The surveys were conducted on January 2025 and MS © Excel was used for the statistical analysis.

The sample sizes of 303 and 304 respondents for each intersection represent statistically robust datasets that meet established standards for survey research among university populations. Based on the estimated 88,000 student population at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the combined sample of 607 participants significantly exceeds the minimum threshold of approximately 384 respondents required for 95% confidence level with ±5% margin of error for populations of this magnitude. This sample size aligns with established practices in pedestrian behavior research, comparable to similar studies such as Van Houten and DeLaere (2022) [11] who surveyed 300 participants across multiple locations, and exceeds many specialized transportation studies that typically range from 100 to 400 participants. The near-equal distribution between the two intersection types ensures adequate statistical power for comparative analysis, while the focus on university students—a homogeneous population with shared mobility patterns and time pressures—enhances internal validity and reduces confounding variables that might arise from broader demographic sampling. Furthermore, the self-reported nature of the data collection through structured questionnaires, combined with the specific targeting of actual users of these intersections, provides both practical relevance and methodological rigor that supports the study’s objectives of understanding pedestrian behavior and safety perceptions at signalized intersections.

This paper offers innovation on multiple levels, extending beyond the research questions alone, contributing systematically through research design, methodology, and technology integration:

- Research Question Innovation: Unlike prior work that often examines general pedestrian safety or isolated behavioral dimensions, this study uniquely focuses on how specific signal phasing characteristics (exclusive protected pedestrian phases versus concurrent vehicle–pedestrian phases permitting turning movements) influence university students’ crossing decisions and perceived safety. This population, characterized by significant time pressures and mobile device distraction, represents an understudied vulnerable group, adding further novelty.

- Methodological Innovation: The paper applies a comparative, dual-site design at two real-world signalized intersections with differing phasing schemes, using structured in situ questionnaire-based surveys targeting actual users (university students). This enables a nuanced behavioral and perceptual comparison under authentic crossing conditions. The method combines demographic, behavior, perception, and intervention priority data, offering a multi-aspect perspective beyond simple compliance statistics.

- Technological and Analytical Innovation: While employing classical statistical analysis (chi-square tests), the paper introduces the exploration of distraction behavior impacts (e.g., mobile phone use) incorporated alongside traditional traffic signal variables, enriching the understanding of modern pedestrian safety risks. Moreover, the research lays groundwork for future adoption of advanced modeling techniques such as structural equation modeling (SEM) for comprehensive latent variable analysis, introducing a pathway for refined technology-based behavioral risk assessment.

4. Results

Concerning the analysis of the collected demographic data the key findings are the following. Overall, the comparison is based on data about Protected and Not Protected pedestrian movement. As Protected is meant that the pedestrians cross the road while the vehicles are stopped facing a red light, while as Not Protected is meant that the pedestrians cross the road while vehicles are allowed through yellow flashing arrows and green light to pass respecting the Greek Road Traffic Code.

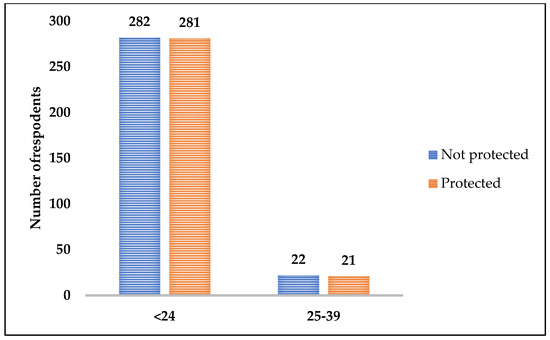

Figure 2 presents the distribution of individuals across two age groups (<24 and 25–39) based on their protection status, categorized as “Protected” and “Not protected.” The <24 age group overwhelmingly dominates the sample, with nearly equal representation in both protection categories, indicating that most participants belong to this younger demographic. In contrast, the 25–39 group includes significantly fewer individuals, suggesting limited participation or lower relevance within this age range. The similar numbers of “Protected” and “Not protected” individuals within each group imply that protection status is not notably influenced by age in this dataset.

Figure 2.

Comparison of respondents’ age groups.

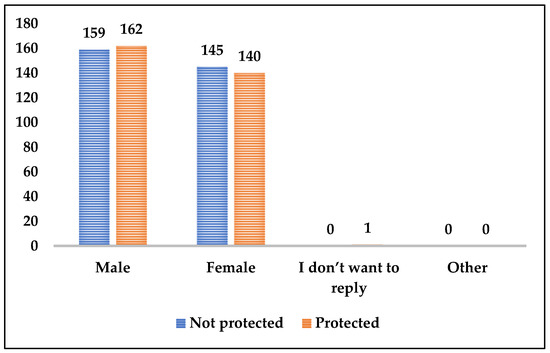

Figure 3 presents the number of male and female pedestrians crossing under two traffic conditions: “Protected”, where vehicles are stopped at a red light, and “Not Protected”, where vehicles are allowed to pass (e.g., with green lights or flashing yellow arrows) in accordance with the Greek Road Traffic Code. Among males, protected crossings slightly outnumber unprotected ones (162 vs. 159), whereas females show a small inverse trend, with more unprotected crossings (145) than protected (140). Only one respondent chose not to disclose their gender, and no one identified as “Other.” The near-equal distribution of protected and unprotected crossings across genders indicates that many pedestrians regularly cross under conditions where vehicle traffic is active, highlighting potential safety concerns. These findings suggest the need for targeted interventions to improve pedestrian safety, such as enhanced signal timing, physical infrastructure changes, or behavioral campaigns, especially considering that unprotected crossings inherently carry greater risk.

Figure 3.

Comparison of respondents’ gender groups.

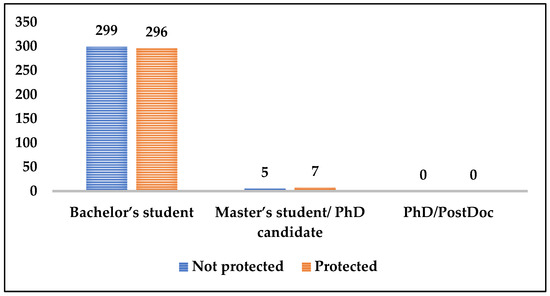

Figure 4 presents the number of pedestrian crossings under protected and not protected conditions, categorized by educational status. The overwhelming majority of respondents are Bachelor’s students, with 299 reporting crossings under not protected conditions and 296 under protected ones, indicating a nearly even distribution but slightly more exposure to unprotected situations. A much smaller group of Master’s students or PhD candidates reported 5 unprotected and 7 protected crossings, while no PhD/PostDoc-level individuals were recorded. These results suggest that most pedestrian behaviors analyzed relate to undergraduate students, who experience both protected and unprotected crossings at almost equal rates, underlining the potential safety risks faced by this group and the importance of targeted road-safety measures within university zones.

Figure 4.

Comparison of respondents’ educational level.

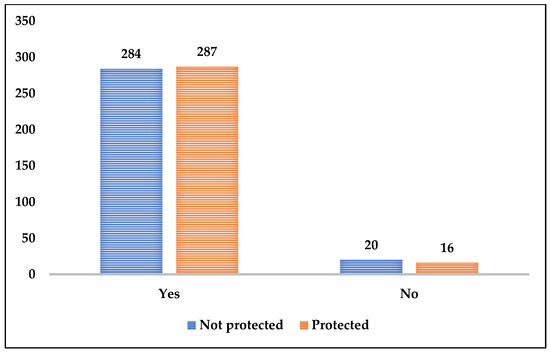

Figure 5 presents the number of pedestrians crossing under protected and not protected conditions based on whether they own a private car. Among respondents who own a car, 287 crossings occurred under protected conditions (vehicles stopped at a red light) and 284 under not protected conditions (vehicles allowed to move, e.g., with flashing yellow or green light), indicating a nearly equal distribution. For those who do not own a car, the numbers are lower overall but show a slight preference for unprotected crossings (20 vs. 16). These results suggest that regardless of car ownership, pedestrians frequently cross in both protected and unprotected conditions, but car owners slightly more often engage in protected crossings. This could imply that drivers, being more aware of traffic behavior, may choose safer crossing moments, although the small difference calls for further investigation into pedestrian decision-making across user groups.

Figure 5.

Comparison of respondents’ private car ownership.

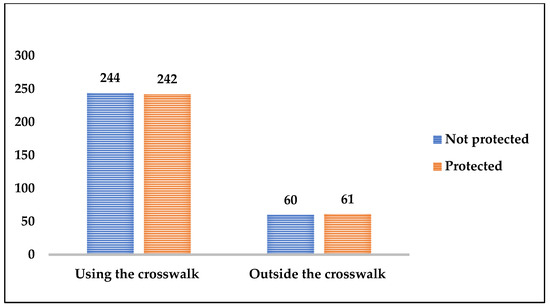

Figure 6 presents the distribution of individuals based on their crossing method—”Using the crosswalk” versus “Outside the crosswalk”. The “Using the crosswalk” category represents the dominant method of crossing, with a nearly even split between “Not protected” (244 individuals) and “Protected” (242 individuals), indicating that the vast majority of observed crossings occur at designated crosswalks, regardless of protection status. In contrast, “Outside the crosswalk” crossings are significantly fewer, with 60 individuals “Not protected” and 61 “Protected”, suggesting that a smaller, but still present, portion of the population crosses without using designated areas. The relatively balanced numbers between “Not protected” and “Protected” within both crossing methods imply that protection status is not primarily dictated by the choice of crossing location itself, but rather that both protected and unprotected crossings occur at similar rates within each crossing behavior. Overall, the chart highlights a strong preference for using crosswalks, which are generally associated with safer pedestrian behavior.

Figure 6.

Comparison of respondents’ street crossing habit.

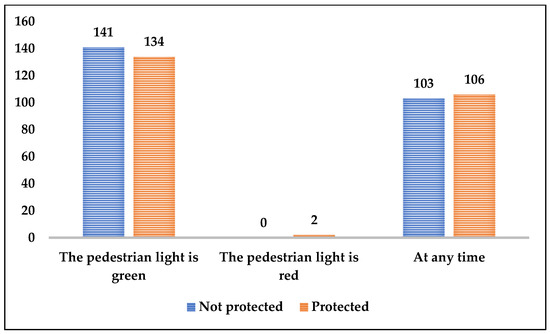

Figure 7 presents pedestrian crossing behavior categorized by the traffic light signal. When “The pedestrian light is green”, a substantial number of individuals cross, with 141 classified as “Not protected” and 134 as “Protected”. This indicates that while the green light is generally perceived as safe, a considerable portion of these crossings still fall under the “Not protected” category, suggesting potential variations in how “protection” is defined or applied even with a favorable signal. Conversely, “The pedestrian light is red” shows almost no crossings, with 0 “Not protected” and only 2 “Protected”, strongly suggesting that pedestrians largely adhere to red lights, especially in a “Not protected” context. The “At any time” category also shows significant activity, with 103 individuals “Not protected” and 106 “Protected”. This implies that a notable portion of pedestrians cross regardless of the specific light phase, with a nearly even split between protected and non-protected scenarios within this group. Overall, the chart highlights that while green pedestrian lights are the primary time for crossing, a significant number of crossings also occur “At any time”, and even with a green light, a notable portion of pedestrians are considered “Not protected”.

Figure 7.

Comparison of respondents’ street crossing habit in relation to traffic light signal.

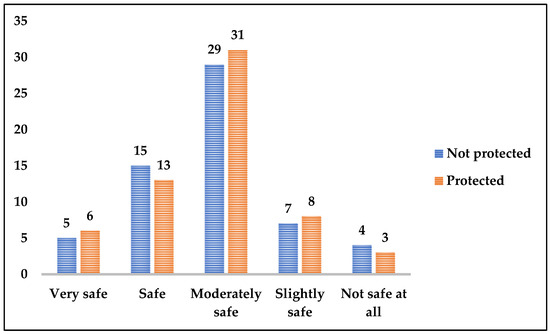

Figure 8 presents individuals’ subjective safety perceptions during street crossings. The largest group perceives crossings as “Moderately safe”, with 29 individuals “Not protected” and 31 “Protected”, indicating that a mid-range perception of safety is most common, whether under protected or unprotected conditions. Following this, “Safe” is the next most frequent response, with 15 “Not protected” and 13 “Protected” individuals. Perceptions of “Very safe” are less common, showing 5 “Not protected” and 6 “Protected”. On the more cautious side, “Slightly safe” is reported by 7 “Not protected” and 8 “Protected” individuals, while “Not safe at all” has the lowest numbers, with 4 “Not protected” and 3 “Protected” responses. Overall, the chart suggests that the majority of respondents perceive crossing as at least “Moderately safe”, with a slight tendency for “Protected” individuals to report slightly higher safety perceptions (e.g., more “Moderately safe” and “Very safe” in absolute numbers). There is a consistent trend across all safety levels where the numbers of “Not protected” and “Protected” individuals are relatively close, implying that the perception of safety is not drastically different between these two groups.

Figure 8.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived level of safety.

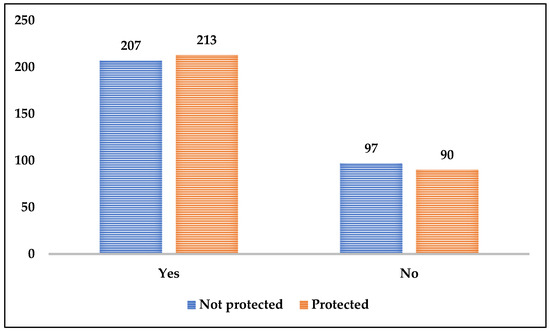

Figure 9 presents individuals’ responses to whether they use traffic lights with counters for pedestrians. The majority of respondents indicated “Yes” to using such lights, with 207 individuals classified as “Not protected” and 213 as “Protected”. This suggests a strong overall inclination towards using traffic lights with countdown timers, regardless of their protection status, likely because these counters provide useful information for crossing. Conversely, a smaller but significant number of individuals answered “No” to using these lights, with 97 identified as “Not protected” and 90 as “Protected”. The data reveals that while a large portion of the sample utilizes these advanced pedestrian signals, a notable segment does not, and the distribution between “Not protected” and “Protected” individuals remains relatively consistent across both “Yes” and “No” responses. This implies that the decision to use or not use traffic lights with counters is not heavily influenced by whether an individual falls into the “Protected” or “Not protected” category.

Figure 9.

Comparison of respondents’ opinion on installing a traffic light with counter would make them feel safer.

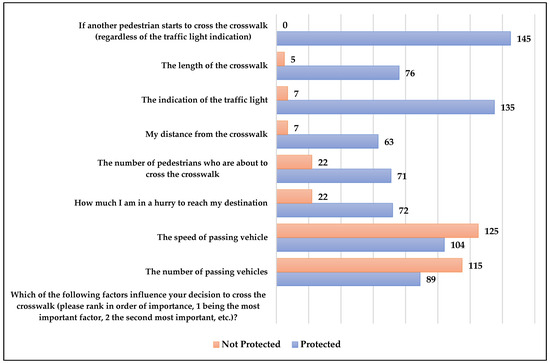

Figure 10 presents various factors that influence pedestrians’ decisions to cross. The most influential factor for “Not protected” individuals appears to be “If another pedestrian starts to cross the crosswalk”, with a substantial 145 responses, while “Protected” individuals show 0 responses for this factor, indicating a significant reliance on others’ actions when unprotected. “The indication of the traffic light” also strongly influences “Not protected” individuals (135 responses), while “Protected” individuals show only 7 responses for this factor, again suggesting a differing reliance on explicit signals based on protection status. Conversely, factors like “The number of passing vehicles” (115 for “Protected” vs. 89 for “Not protected”) and “The speed of passing vehicle” (125 for “Protected” vs. 104 for “Not protected”) show that “Protected” individuals are more influenced by vehicular traffic conditions. “The length of the crosswalk”, “My distance from the crosswalk”, “The number of pedestrians who are about to cross”, and “How much I am in a hurry to reach my destination” generally show lower numbers for both groups, although “Not protected” individuals still consistently have higher counts for these factors. Overall, Figure 10 strongly suggests that “Not protected” pedestrians are predominantly influenced by the behavior of other pedestrians and the traffic light’s indication, possibly implying a more reactive or less secure crossing approach. In contrast, “Protected” pedestrians are more concerned with vehicular dynamics (speed and number of vehicles), which aligns with the definition of “Protected” crossings where vehicles are allowed through, requiring them to be more attentive to traffic. The stark differences in influence factors between the two protection statuses highlight distinct decision-making processes for pedestrians.

Figure 10.

Comparison of respondents’ factors influencing their decision to cross the street using the crosswalk.

Figure 11 presents various factors contributing to pedestrians’ feelings of insecurity. “Drivers running the yellow light” is the most prominent reason for insecurity among “Not protected” pedestrians, with a substantial 104 responses, significantly higher than the 52 responses from “Protected” pedestrians. This highlights a critical point of insecurity for those crossing under less controlled conditions. Similarly, “The simultaneous passage of vehicles and pedestrians” is a major concern for “Not protected” individuals (86 responses), compared to 72 for “Protected” individuals, suggesting that mixed traffic flow is a greater source of unease when protection is not explicit. “Drivers running the red light” is also a significant concern for both groups, with 74 “Not protected” and 70 “Protected” responses, indicating a widespread insecurity related to severe traffic violations regardless of protection status. “The vehicles in the first row that are about to start” also contribute to insecurity, with 70 “Not protected” and 53 “Protected” responses. Finally, “The short duration of the green light” impacts both groups, with 65 “Not protected” and 56 “Protected” individuals citing it as a reason for insecurity. Overall, the chart reveals that “Not protected” pedestrians consistently report higher levels of insecurity across most factors, particularly concerning drivers running yellow lights and the simultaneous movement of vehicles and pedestrians. This reinforces the notion that their “Not protected” status translates to a heightened perception of risk from various traffic behaviors. While “Protected” pedestrians also experience insecurity from issues like drivers running red lights, the magnitude of these concerns is generally lower than for their “Not protected” counterparts.

Figure 11.

Comparison of respondents’ reasons making them feel insecure.

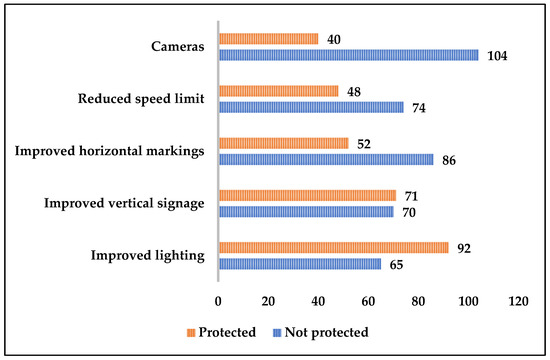

Figure 12 presents various proposed measures for enhancing pedestrian safety. “Cameras” are overwhelmingly favored by “Not protected” individuals as a safety measure, with 104 responses, significantly more than the 40 responses from “Protected” individuals. This suggests that those who feel less protected see surveillance as a crucial way to improve safety, potentially by deterring dangerous driving. “Improved horizontal markings” is another measure strongly preferred by “Not protected” individuals (86 responses) compared to “Protected” individuals (52 responses), indicating a desire for clearer guidance on the road. Similarly, “Reduced speed limit” is more often cited by “Not protected” individuals (74 responses) than by “Protected” individuals (48 responses), highlighting concerns about vehicle speed when crossing. Conversely, “Improved lighting” is a measure where “Protected” individuals show a higher preference (92 responses) than “Not protected” individuals (65 responses), suggesting that better visibility is a greater concern for those who already feel some level of protection. “Improved vertical signage” is desired by both groups, with relatively similar numbers (70 for “Not protected” and 71 for “Protected”), indicating a shared view on the importance of clear road signs. Overall, the chart reveals a clear divergence in preferred safety measures based on protection status. “Not protected” pedestrians primarily advocate for enforcement-based solutions (cameras, reduced speed limits) and clearer infrastructure (horizontal markings), likely to mitigate perceived risks from driver behavior. In contrast, “Protected” pedestrians show a higher preference for measures that enhance overall visibility, such as improved lighting, while also acknowledging the importance of clear signage.

Figure 12.

Comparison of respondents’ proposed measures to improve their perceived level of safety.

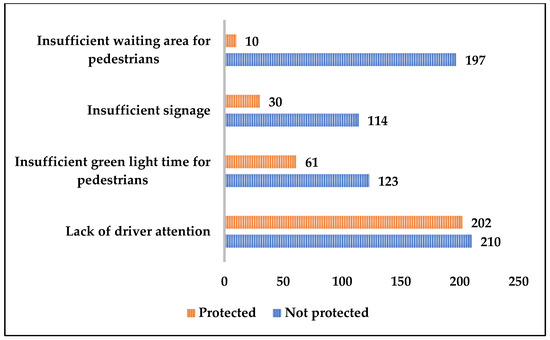

Figure 13 presents the primary factors contributing to pedestrians’ perception of danger. “Lack of driver attention” stands out as the most significant reason for danger for both groups, with 210 “Not protected” and 202 “Protected” individuals citing it. This indicates a widespread concern regarding driver vigilance across all pedestrians in Thessaloniki, regardless of their protection status. “Insufficient waiting area for pedestrians” is overwhelmingly identified as a danger by “Not protected” individuals (197 responses), contrasting sharply with only 10 responses from “Protected” individuals. This highlights a critical infrastructural deficiency perceived by those who feel more vulnerable. Similarly, “Insufficient green light time for pedestrians” is a substantial concern for “Not protected” individuals (123 responses) compared to 61 for “Protected” individuals, suggesting that insufficient crossing time is a significant risk factor when not “Protected.” “Insufficient signage” also contributes to insecurity, with 114 “Not protected” and 30 “Protected” individuals citing it. Overall, the chart clearly shows that while “Lack of driver attention” is a universal concern, “Not protected” pedestrians disproportionately perceive danger from infrastructural shortcomings such as insufficient waiting areas, insufficient green light time, and insufficient signage. This suggests that their “Not protected” status may be directly linked to perceived deficiencies in the pedestrian environment and traffic management, whereas “Protected” pedestrians, while still concerned about driver behavior, are less impacted by these specific infrastructural issues.

Figure 13.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived dangers for their safety.

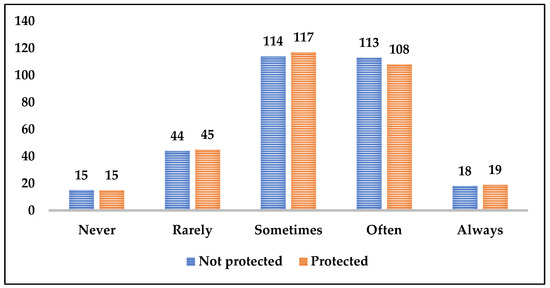

Figure 14 presents how often pedestrians cross the street in a hurry. The most common response for both groups is “Sometimes”, with 114 “Not protected” and 117 “Protected” individuals indicating this frequency. This suggests that crossing with haste is a common, though not constant, occurrence for a significant portion of pedestrians, regardless of their protection status. “Often” is the next most frequent category, with 113 “Not protected” and 108 “Protected” responses, further highlighting the commonality of hurried crossings. Conversely, “Never” crossing with haste is the least common response, with 15 individuals in both “Not protected” and “Protected” categories. Similarly, “Rarely” crossing with haste is also relatively low, with 44 “Not protected” and 45 “Protected” responses. “Always” crossing with haste accounts for 18 “Not protected” and 19 “Protected” individuals, representing a small but consistent segment. Overall, the chart indicates that a significant majority of pedestrians, both “Not protected” and “Protected”, cross the street with some degree of haste, primarily “Sometimes” or “Often.” The similar distribution of responses between the “Not protected” and “Protected” groups across all frequency categories suggests that the underlying reason for being in a hurry (e.g., time constraints, personal habits) is largely independent of whether a pedestrian is crossing under “Protected” or “Not protected” conditions.

Figure 14.

Comparison of respondents’ stated frequency of crossing under haste.

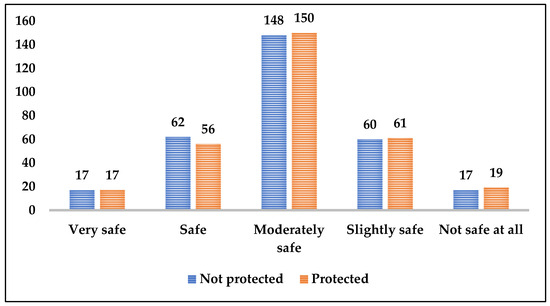

Figure 15 presents how pedestrians perceive their safety when crossing the street while simultaneously talking on a mobile phone. The most frequent perception of safety for both groups falls under “Moderately safe”, with 148 “Not protected” and 150 “Protected” individuals indicating this level. This suggests a widespread, tempered sense of security when engaging in this common multitasking behavior. Following this, a considerable number also perceive it as “Slightly safe”, with 60 “Not protected” and 61 “Protected” responses, indicating a notable portion feels a degree of reduced safety. Fewer individuals perceive it as either “Very safe” (17 for both groups) or “Safe” (62 “Not protected”, 56 “Protected”). At the other end of the spectrum, the perception of “Not safe at all” is the least common, reported by 17 “Not protected” and 19 “Protected” individuals. Overall, the chart reveals a consistent pattern: regardless of whether pedestrians are “Protected” or “Not protected” during a crossing, their perceived level of safety when simultaneously talking on the phone is remarkably similar across all categories. This strongly implies that the act of talking on the phone during a crossing equally impacts the subjective feeling of safety for all pedestrians, potentially by diverting attention, and that the “Protected” status does not significantly alleviate this perceived risk.

Figure 15.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived level of safety when crossing while talking on the phone.

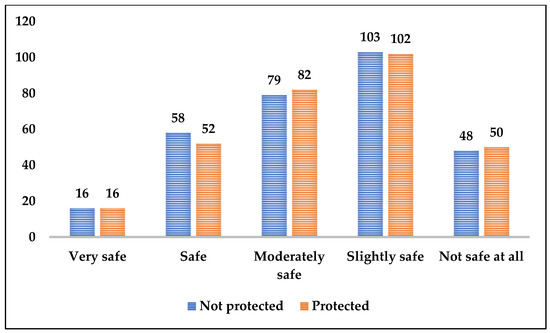

Figure 16 presents how pedestrians perceive their safety when crossing the street while actively using a mobile phone for non-verbal tasks (e.g., texting, Browse). The most prevalent perception of safety for both groups is “Slightly safe”, with 103 “Not protected” and 102 “Protected” individuals indicating this level. This suggests that merely using the phone (without talking) while crossing still significantly diminishes perceived safety for a substantial portion of pedestrians. The “Not safe at all” category follows with a considerable number of responses: 48 for “Not protected” and 50 for “Protected”, further emphasizing the perceived danger of this behavior. “Moderately safe” is also a common perception, reported by 79 “Not protected” and 82 “Protected” individuals. Fewer individuals consider it “Safe” (58 “Not protected”, 52 “Protected”) or “Very safe” (16 for both groups). Overall, the chart reveals a consistent trend where “Slightly safe” and “Not safe at all” are the most frequently chosen categories for both “Not protected” and “Protected” pedestrians when actively using their phone while crossing. This strongly implies that the act of using a phone (even without talking) while crossing significantly impairs perceived safety, regardless of whether the pedestrian is in a “Protected” or “Not protected” crossing scenario. The remarkable similarity in responses between the two protection statuses suggests that this form of distraction impacts perceived safety almost equally for all pedestrians.

Figure 16.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived level of safety when crossing while using the phone (no talking).

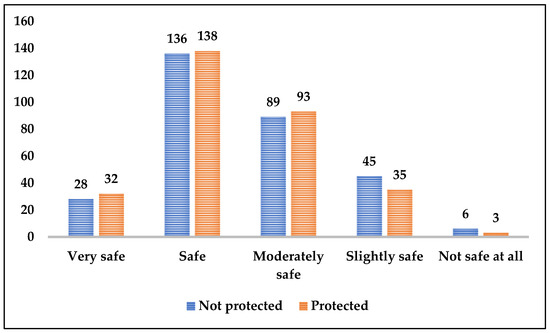

Figure 17 presents how pedestrians perceive their safety when crossing the street while engaged in conversation with friends. The most common perception of safety for both groups falls under “Safe”, with 136 “Not protected” and 138 “Protected” individuals indicating this level. This suggests that engaging in conversation with friends while crossing is widely perceived as a relatively safe activity. Following this, “Moderately safe” is the next most frequent response, with 89 “Not protected” and 93 “Protected” individuals. “Very safe” is also reported by a notable number, 28 “Not protected” and 32 “Protected” individuals. On the less safe end of the spectrum, “Slightly safe” is indicated by 45 “Not protected” and 35 “Protected” responses. The perception of “Not safe at all” is the least common, with only 6 “Not protected” and 3 “Protected” individuals. Overall, the chart reveals a strong inclination towards perceiving safety as “Safe” or “Moderately safe” when crossing while talking with friends, for both “Not protected” and “Protected” pedestrians. The numbers across all safety perception categories are remarkably similar between the two protection statuses. This implies that, unlike phone usage, engaging in conversation with friends does not significantly diminish the perceived level of safety, and the “Protected” status does not notably alter this perception. The lower numbers for “Slightly safe” and “Not safe at all” compared to phone usage charts suggest that social interaction is perceived as less distracting or dangerous than phone-related activities.

Figure 17.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived level of safety when crossing while talking with other people (friends).

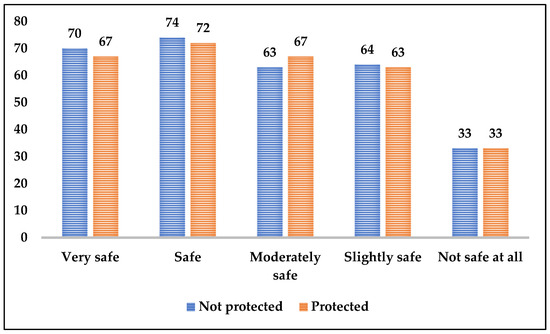

Figure 18 presents how pedestrians in Thessaloniki perceive their safety when crossing the street while listening to music using headphones. The most frequent perceptions of safety are “Safe” (74 for “Listening to music using headphones”/”Not protected”, and 72 for “Protected”) and “Very safe” (70 for “Listening to music using headphones”/”Not protected”, and 67 for “Protected”). This suggests that a substantial number of pedestrians feel a high level of safety even when listening to music with headphones. “Moderately safe” is also a common perception (63 for “Listening to music using headphones”/”Not protected”, and 67 for “Protected”). However, a significant portion also perceives this activity as “Slightly safe” (64 for “Listening to music using headphones”/”Not protected”, and 63 for “Protected”). Importantly, “Not safe at all” is reported by 33 individuals in both categories, highlighting that a notable segment recognizes the inherent danger. Overall, the chart indicates that while a large portion of pedestrians in Thessaloniki perceive crossing with headphones as “Safe” or “Very safe”, a considerable number also acknowledge it as “Slightly safe” or “Not safe at all.” The distribution of perceived safety levels is remarkably similar between the two groups (assuming blue is ‘Not Protected’ and orange is ‘Protected’), implying that listening to music with headphones impacts perceived safety almost equally for all pedestrians, regardless of their protection status, likely due to the common factor of reduced auditory awareness.

Figure 18.

Comparison of respondents’ perceived level of safety when crossing while listening to music.

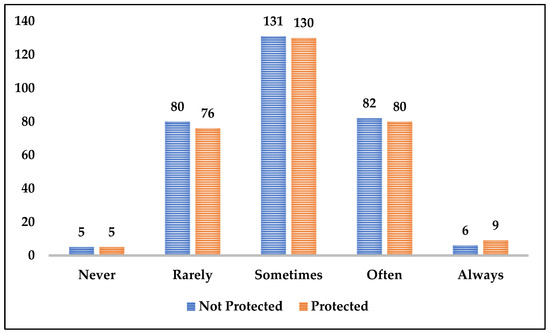

Figure 19 presents how often pedestrians in Thessaloniki cross the street while talking on their phone. The most common frequency for both groups is “Sometimes”, with 131 individuals in the “Talking on phone” group and 130 in the “Protected” group indicating this. This suggests that a large portion of pedestrians engage in this multitasking behavior with moderate frequency. “Often” is also a significant category, reported by 82 individuals in the “Talking on phone” group and 80 in the “Protected” group, further highlighting the commonality of this behavior. “Rarely” talking on the phone while crossing is also a considerable response, with 80 individuals in the “Talking on phone” group and 76 in the “Protected” group. “Never” engaging in this behavior is minimal, with only 5 individuals in both categories. Similarly, “Always” talking on the phone while crossing is a small proportion, with 6 individuals in the “Talking on phone” group and 9 in the “Protected” group. Overall, the chart indicates that a large majority of pedestrians in Thessaloniki cross the street while talking on the phone “Sometimes” or “Often.” The frequency distributions of phone usage while crossing were nearly identical between protected and non-protected groups, indicating minimal influence of crossing status on this behavior.

Figure 19.

Comparison of respondents’ frequency on crossing while talking to phone.

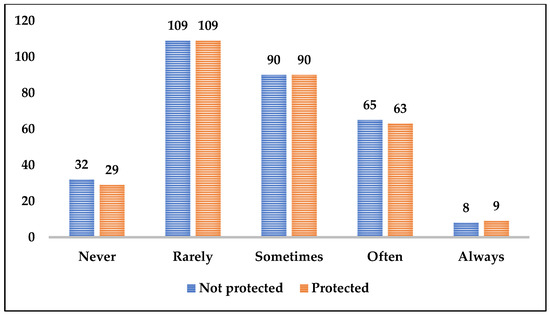

Figure 20 presents how often pedestrians in Thessaloniki cross the street while actively using their phone for non-verbal tasks (e.g., texting, browsing). The most common frequency for both groups is “Rarely”, with 109 individuals in both “Not protected” and “Protected” categories. This indicates that while it does occur, actively using a phone without talking while crossing is often not a constant behavior for the majority of pedestrians. “Sometimes” is the next most frequent response, with 90 individuals in both groups. “Often” also sees significant numbers, with 65 “Not protected” and 63 “Protected” responses. Conversely, “Never” engaging in this behavior is less common, with 32 “Not protected” and 29 “Protected” individuals. “Always” crossing while actively using the phone (no talking) is the least frequent, reported by only 8 “Not protected” and 9 “Protected” individuals. Overall, the chart reveals that a substantial portion of pedestrians in Thessaloniki “Rarely” or “Sometimes” cross the street while actively using their phone (non-talking). The remarkably similar distribution across all frequency categories for both “Not protected” and “Protected” groups suggests that the propensity to use a phone in this manner while crossing is independent of a pedestrian’s “Protected” status.

Figure 20.

Comparison of respondents’ frequency on crossing while using their phone.

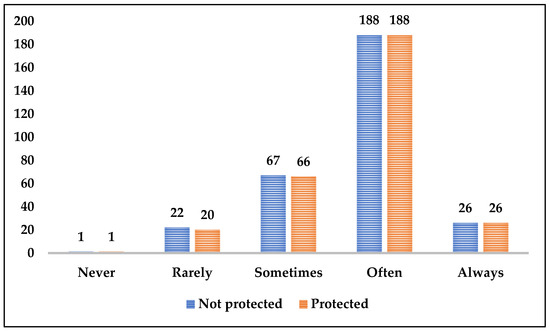

Figure 21 presents how often pedestrians in Thessaloniki cross the street while engaged in conversation with friends. The most prominent frequency for both groups is “Often”, with 188 individuals in both “Not protected” and “Protected” categories. This indicates that a significant majority of pedestrians frequently cross while talking with friends. “Sometimes” is the next most common response, with 67 “Not protected” and 66 “Protected” individuals. Conversely, “Rarely” talking with friends while crossing is reported by 22 “Not protected” and 20 “Protected” individuals. “Always” engaging in this behavior while crossing is also a notable frequency, with 26 individuals in both categories. “Never” crossing while talking with friends is extremely rare, with only 1 individual in each group. Overall, the chart clearly shows that talking with friends while crossing the street is a very common behavior among pedestrians in Thessaloniki, with a strong tendency to occur “Often.” The frequency distributions are remarkably consistent between “Not protected” and “Protected” groups, suggesting that social interaction during crossings is a prevalent habit that does not significantly differ based on a pedestrian’s protection status.

Figure 21.

Comparison of respondents’ frequency on crossing while talking to other people (friends).

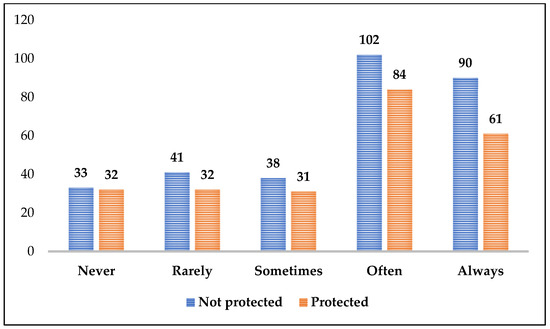

Figure 22 presents how often pedestrians in Thessaloniki cross the street while listening to music using headphones. Often” is the most frequent response for “Not protected” individuals (102 responses), indicating a strong tendency to engage in this behavior. For “Protected” individuals, “Often” is also the most common response, but with fewer instances (84 responses), suggesting they might do it less frequently than their “Not protected” counterparts. “Always” shows a similar pattern, with 90 “Not protected” individuals compared to 61 “Protected” individuals, further highlighting a higher frequency among the “Not protected” group. Conversely, “Never” crossing while listening to music is a less common response, with 33 “Not protected” and 32 “Protected” individuals. “Rarely” is reported by 41 “Not protected” and 32 “Protected” individuals. “Sometimes” sees 38 “Not protected” and 31 “Protected” individuals. Overall, the chart suggests that “Not protected” pedestrians tend to cross the street while listening to music “Often” or “Always” more frequently than “Protected” pedestrians. This disparity could imply that the “Not protected” group might be more prone to behaviors that could reduce their auditory awareness during crossings.

Figure 22.

Comparison of respondents’ frequency on crossing while listening to music.

Key findings from the Results section are summarized below:

- Pedestrian walking speed is influenced by several interrelated factors that operate similarly across both distracted and non-distracted individuals: older age and walking in a group tend to reduce speed, while greater crossing distances induce pedestrians to accelerate—perhaps motivated by urgency—and higher pedestrian volumes generally slow overall walking pace.

- For distracted pedestrians, increasing pedestrian volume raises near-miss probability; the opposite holds for non-distracted pedestrians.

- Pedestrian volume positively influences conflict likelihood in both groups.

- Distracted pedestrians not accompanied are more prone to conflicts.

- Conflicts occur more frequently when no vehicle is present on the crossing.

The Chi-square () test is a widely used statistical method for examining associations between categorical variables. It evaluates whether the observed distribution of data across categories deviates significantly from the distribution expected if the variables were independent. Essentially, the test compares observed frequencies in a contingency table with expected frequencies calculated under the assumption of no association, quantifying the discrepancy as the Chi-square statistic.

The core idea behind the Chi-square test of independence is to assess if two categorical variables are related or independent in a given population. By tabulating counts of observations for each combination of categories, the test measures how much the actual joint distribution differs from what would be expected if the categories were unrelated. A large Chi-square statistic accompanied by a small p-value indicates a significant association, suggesting that the variables influence each other.

In the context of the pedestrian behavior data analyzed here, multiple pairs of categorical variables—including gender, age groups, crossing types, perceived safety, and attention to vehicles—were tested using the Chi-square method. The majority of variable pairs showed no statistically significant association, implying independence among most variables in this sample. However, the Chi-square test revealed a significant relationship between age group and perceived crossing safety in the group using protected crossings.

Table 2 presents the detailed Chi-square Test results for associations between key categorical variables in Protected and Non-Protected Pedestrian Crossing Groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of Chi-square Test Results for Association Between Key Categorical Variables in Protected and Non-Protected Pedestrian Crossing Groups (n1 = 304—Protected, n2 = 303—Non Protected).

The descriptions of the variables tested in the Chi-square analyses are provide below:

- Gender: Categorical variable representing respondent’s gender. Categories include Male, Female, and some missing or unspecified responses.

- Age Group: Aggregated categorical variable derived from exact age or age ranges. Typical categories include <24, 25–39, 40–54, 55–65, >65, grouping respondents by age cohort.

- Crossing Type: Type of pedestrian crossing typically used by the respondent. Categorized as “Protected” (designated safe crossings, e.g., with pedestrian signal phases) or “Non-Protected”.

- Crossing Behavior Safety: Respondent’s perception of how safe they feel when crossing, typically with categories such as Safe, Somewhat Safe, or Not Safe.

- Vehicle Check: Indicates whether the respondent looks out for approaching vehicles before crossing. Usually binary Yes/No categories.

For the Protected group, the only statistically significant relationship observed is between Age Group and perceived Crossing Behavior Safety. This finding suggests that perceptions of safety vary meaningfully among different age cohorts when crossing in protected environments. It points to age being an important demographic factor influencing how secure pedestrians feel, which could reflect varying risk attitudes, experience, or vulnerability perceptions that urban planners need to consider for targeted safety interventions.

In contrast, the Non-Protected group showed no significant associations between any pairs of tested variables, including age, gender, crossing type, safety perception, and vigilance in checking for vehicles. This lack of statistical significance may stem from limited sample size, less variability in responses, or a different behavioral dynamic in non-protected crossing conditions. It indicates that in non-protected settings, these demographic and behavioral factors may not exhibit clear, quantifiable relationships in this sample.

Neither group showed gender-based significant associations with any safety or behavioral variables, suggesting that male and female pedestrians in the study behave similarly with respect to crossing preferences, safety perception, and vigilance.

Overall, the analysis highlights the value of protected crossings in creating measurable variations in pedestrian safety perceptions across age groups, underlining the importance of protection features in pedestrian infrastructure to address demographic differences. The findings also emphasize the need for further study of behaviors in non-protected contexts, potentially with larger datasets or complementary methods (e.g., advanced econometric modeling) to uncover subtle or complex associations.

Table 3 presents a concise summary linking the Research Questions to actual finding, emphasizing how signal phase underpins differences in behavior, safety perceptions, and intervention preferences.

Table 3.

Summary linking the Research Questions to actual findings.

5. Discussion

This research aimed to conduct a comparative analysis of pedestrian behavior and perceived safety among university students at two signalized intersections in Thessaloniki, Greece, one permitting vehicle left turns during pedestrian phases (“Not protected” crossings) and the other restricting all vehicle movement (“Protected” crossings). The findings, derived from two questionnaire-based surveys, offer significant insights into how signal phasing and intersection design profoundly shape pedestrian decisions and their subjective sense of security.

For clarity in the international context, it is important to note that what is referred to here as “Not protected” phasing (vehicles and pedestrians moving concurrently) is often termed “concurrent phasing” in the global literature, while “Protected” phasing (all vehicle movement stopped for pedestrians) aligns with “exclusive” or “protected” pedestrian phases. Making this distinction helps align our findings with broader research on signal phasing strategies.

Our results underscore a critical distinction in pedestrian experience: crossings where vehicles are permitted to move (defined as “Not protected”) are consistently associated with lower levels of perceived safety and a higher propensity for risk-taking behaviors. Specifically, as presented in Figure 7, a considerable number of “Not protected” crossings occurred even when the pedestrian light was green, and significantly, a large number of “Not protected” individuals also crossed “at any time”, indicating less adherence to explicit signals compared to their “Protected” counterparts. This aligns with findings by Haque et al. (2024) [20] and Dhoke & Choudhary (2024) [17] who noted that time-saving and personal convenience often drive unsafe crossings, and Rafe et al. (2025) [16] who identified factors influencing spatial and temporal violations. The Greek Road Traffic Code’s provision for flashing yellow arrows, which requires drivers to yield but allows movement [47], inherently creates a more ambiguous environment for pedestrians, leading to the observed “Not protected” scenarios.

The influence factors for crossing decisions (Figure 10) further highlight this divergence. “Not protected” pedestrians are overwhelmingly influenced by the presence of other pedestrians (145 responses for “If another pedestrian starts to cross the crosswalk”) and the traffic light indication (135 responses), suggesting a reactive approach where social cues and basic signals are paramount. This contrasts sharply with “Protected” pedestrians, who show minimal reliance on these social cues (0 responses) and traffic light indications (7 responses), instead being more influenced by vehicular dynamics like the number and speed of passing vehicles. This behavior of “Protected” pedestrians is consistent with the heightened awareness required when crossing in a mixed traffic flow, as discussed by He et al. (2019) [5] regarding conflicts with left-turning vehicles.

Perceptions of insecurity (Figure 11) also varied significantly with protection status. “Not protected” pedestrians cited “Drivers running the yellow light” and “The simultaneous passage of vehicles and pedestrians” as major reasons for feeling insecure. This resonates with the findings of Do et al. (2023) [12], who found that pedestrian countdown signals can unintentionally lead to more aggressive driver behavior, and Xie et al. (2025) [30], who highlighted risks from sequential traffic conflicts. The widespread concern about “Lack of driver attention” (Figure 13) among both groups further emphasizes a fundamental behavioral issue in the urban traffic ecosystem, as noted by various studies in the literature review focusing on driver behavior [12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, “Not protected” pedestrians disproportionately perceive danger from infrastructural shortcomings such as insufficient waiting areas and insufficient green light time (Figure 13), aligning with observations by Alhajyaseen and Nakamura (2010) [35] and Iryo Asano & Alhajyaseen (2017) [25] regarding compromised crosswalk efficiency and speed changes.

Regarding proposed safety measures (Figure 12), “Not protected” pedestrians prioritize enforcement (cameras, reduced speed limits) and clearer infrastructure (horizontal markings), indicating a desire for systemic changes to mitigate perceived risks from driver behavior. The strong preference for cameras among the “Not protected” group (104 responses versus 40 for “Protected”) underlines their felt vulnerability and belief in stricter enforcement as a solution. In contrast, “Protected” pedestrians show a higher preference for measures enhancing overall visibility, such as improved lighting, suggesting that their existing level of protection allows them to focus on subtler environmental improvements. This suggests that different interventions are needed based on the type of intersection and the associated pedestrian “protection” level.

The study also examined the impact of distractions on perceived safety and crossing frequency. Interestingly, while talking on the phone or actively using it (non-talking) while crossing significantly diminished perceived safety for both “Protected” and “Not protected” groups (Figure 15 and Figure 16), the frequency of engaging in these behaviors was largely similar across both categories (Figure 19 and Figure 20). This implies that distractions, particularly phone usage, are a pervasive factor impacting pedestrian safety perception irrespective of signal phasing. This corroborates the findings of Zhou et al. (2019) [22], Gruden et al. (2022) [26], and Perra et al. (2022) [27], who highlighted how mobile phone use and distractions influence pedestrian behavior and visual attention. Conversely, talking with friends while crossing was perceived as much safer (Figure 17) and was a very common behavior (Figure 21), suggesting social interaction may be viewed differently from electronic distractions. Furthermore, listening to music, while impacting perceived safety for both groups, was more frequent among “Not protected” pedestrians (Figure 22), indicating a potential higher exposure to reduced auditory awareness in this group.

These findings highlight the critical role of specific signal phasing strategies in shaping pedestrian confidence and behavior. Intersections that restrict all vehicle movement during pedestrian phases foster greater compliance and a stronger sense of security, aligning with studies that advocate for exclusive pedestrian phases [8,23,43]. The presence of vehicle conflict, even with yield provisions, significantly erodes perceived safety and encourages riskier crossing decisions among university students, a vulnerable group often under time pressure and prone to distractions [22,44].

While our findings and prior studies indicate that exclusive pedestrian phases generally increase perceived safety and compliance, it should be noted that their effectiveness can be influenced by factors such as pedestrian impatience, long wait times, or low vehicle volumes. Even with protected phasing, some pedestrians may choose to cross against the signal if delays are perceived as excessive, as reported in recent observational studies.

Recent research also suggests that protected phasing not only reduces the frequency of pedestrian–vehicle conflicts but may also decrease the severity of such incidents when they do occur. Although our study did not directly measure conflict severity, this is an important consideration for urban planners evaluating the overall safety benefits of exclusive pedestrian phases.

Previous research on pedestrian compliance with traffic signals in Greece indicates generally lower red-light violation rates than those observed in our university student sample. For instance, Schrenk et al. (2012) [48] reported that approximately 15% of pedestrians in the city of Volos crossed against the red light during signalized phases. Similarly, Roussou et al. [49] demonstrated through video surveillance at busy Athens’s intersections that red-light violations occurred but at lower proportions varying by intersection characteristics. These studies involving general urban populations suggest that our measured 40% red-running rate among students reflects a substantially higher risk-taking behavior, possibly attributable to their condensed schedules, peer influences, and familiarity with local crossings.