Abstract

Women play integral roles across various sectors, including mining. Moreover, they often form a majority in certain sectors, such as healthcare and education. Biological (sex) and social (gender) differences can influence how hazards are assessed and controlled for women at work. Therefore, because of the importance of women’s occupational health and safety (OHS), this study reviews and analyzes OHS-related research studies to explore (i) the attention given to women’s OHS; (ii) the specific occupations studied; and (iii) the primary OHS issues and challenges faced by women. Following PRISMA guidelines, the study examined articles from 2010–2021, selecting 62 that utilized primary data, with all or part of their participants being female. The results indicate that the included studies examined women’s OHS in specific occupations. These include healthcare workers, farm and forestry workers, office staff, teachers, firefighters, police officers, nail technicians, workers in the clothing industry, and general industrial workers. The trend of publishing articles on women’s OHS has been growing, with most studies focusing on healthcare and agriculture. The USA and South Korea are leading in publications in the field of women’s OHS, while the USA, Australia, and the Netherlands have the highest collaboration rates. Key findings reveal that the most common OHS issues faced by women in various occupations include stress, fatigue, musculoskeletal disorders and pain, sleep disorders, long working hours, depression and anxiety, workplace violence, and allergies and skin problems. Many of these issues are related to mental health. Specific issues based on the nature of the work vary; for example, teachers experience voice disorders, while farmers face digestive problems. This study contributes theoretically by enhancing understanding of women’s OHS, serving as a foundation for further research, and providing practical guidance for employers and policymakers seeking to implement effective strategies for guaranteeing women’s OHS across sectors.

1. Introduction

According to the charter of the International Labor Organization (ILO), all people of the world, irrespective of race, belief and gender, have the right to material and spiritual welfare with freedom and respect, as well as to economic security and equality of ownership [1]. In 1948, the United Nations (UN) in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provided equal rights to men and women. It called for the equality of women’s rights in various economic and social areas, such as employment, job promotion, education and choice of profession [2]. However, after 1950, although women’s employment rates had increased worldwide, women had not reached the desired socio-economic position in their working and private lives and were still subject to inequality (e.g., gender pay gap) [3].

Women face risks due to the multiple roles they play in family and society, the different physiological periods they experience, such as puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth and menopause, and their susceptibility to poverty, hunger, malnutrition, increased workloads and gender discrimination, all of which increase their health risks [4]. Health is related to all aspects of primary human rights [5]. The world’s health systems are increasingly shifting their goals from providing health care to creating a healthy society [6]. The general health indicators, such as welfare, have been replaced by limited and inadequate indices, such as mortality [7]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, well-being, physical, and social welfare are not just the lack of illness or organ defect [8]. The health and well-being of women, who constitute half of society, is not only recognized as a human right, the impact it has on family health and community is also becoming increasingly important [9,10]. According to the UN, women’s health is one indicator of a country’s level of development [11]. Countries cannot achieve thorough and sustainable development unless they take both halves of the population into consideration [12]. In recent decades, as a result of extraordinary efforts, women’s role in labor and income earning has increased [13]. More women work regularly, although their job opportunities are still limited based on gender [14]. The ILO has identified three main problems related to the work life of women: lack of social protection and access to decent work opportunities; challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities; and workplace discrimination and inequality [15,16].

Today, a considerable number of women are employed in the agriculture industry. Women produce half of the world’s food [7]. In the meantime, exposure to pesticides, which are an inevitable component in agricultural production, can be a threatening factor for women who hold farming jobs [17]. Estimations indicate that worldwide, 0.3 million workers in the agricultural sector lose their lives due to exposure to pesticides. Women are exposed to these toxins because protection measures are not respected [18]. Pesticide exposure has been linked to breast cancer in postmenopausal women as well as to aborted and not fully developed babies [19].

Women’s and men’s bodies have distinct physiological and anatomical differences, including in their skeletal structure, body fat composition, respiratory system [20,21,22,23]. Therefore, although working in the same conditions as men, women can experience different outcomes. Among the inherent differences that can influence these consequences are differences in body size and physical strength. Women, due to having less physical strength, are more likely to experience higher levels of muscular strain and may face greater physical discomfort when using personal protective equipment (PPE) [23,24]. Most PPE is designed for male workers and does not consider the dimensions and body size of women, leading to inadequate protection [25]. Women are vulnerable when exposed to chemicals in the following specific ways: The absorption of cadmium via the gastrointestinal tract poses more danger to women than to men, especially during menstruation and for women who have low iron storage and protein intake [26]. Also, the chemical substances absorbed in women’s bodies are dispersed more rapidly because of their smaller body mass, which is dependent on a more vigorous blood circulation system, causing faster substance release in the tissues [27]. The renal system in women is slower than in men, which leads to slower excretion of toxic substances through the urine [28]. Women’s bodies have more adipose tissue than men, which causes toxic substances to be absorbed, accumulated, and retained in the body. Studies on the rate of women’s exposure in the workplace to perchloroethylene, the primary solvent in cleaners, reveal the relevance of this substance to cervical cancer [29]. Further studies show that similar risk factors may increase women’s probability of developing bladder cancer and kidney problems [30]. In Chinese women, the prevalence of breast cancer was observed in laboratory technicians, telephone operators and telegraph operators, leather and fur workers, and glass workers [31]. In Norway, the incidence of ovarian cancer was high in women working in the paper industry [32]. In Russia, mortality due to gastric cancer and esophageal cancer is reported in women in the printing industry [33].

Work conditions, regarding ergonomics, work speed, heavy load management, and use of PPE, have been designed for the size and physical strength of the average male worker, despite the increasing participation of female workers in many fields. The high cost of appropriate interventions is still a barrier to improving women’s work environments and OHS. The use of PPE not designed appropriately for the physical size of women workers leads to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), especially during pregnancy. Additionally, the efficacy of some PPE, such as respirators, gloves and boots, is reduced when not suited for women’s physical dimensions [34,35]. Various studies have shown that employed women tend to be more vulnerable to carpal tunnel syndrome, burns, wounds and fractures, as well as to MSDs, than men [36].

As mentioned above, the role women play in the working environment is undeniable. Due to their physical and physiological characteristics, they experience different outcomes when exposed to hazards in the workplace. Therefore, they encounter distinct health and safety challenges that must be considered to prevent injuries and illnesses and provide a healthy and safe workplace. In this regard, the focus of this paper is on reviewing and analyzing OHS-related research studies that used primary data, with all or part of their participants from the female population, to address the following research questions. It is worth noting that the studies using primary data were investigated because primary data are collected directly from the source [37] (female population) and provides deeper, more accurate, and reliable knowledge [38].

- Research Question 1. How much attention did research studies draw to women’s health and safety in workplaces between 2010 and 2021?

- Research Question 2. In which occupations within specific sectors have research studies primarily concentrated on the female population, examining women’s OHS in those occupations?

- Research Question 3. Based on previous research studies, what are the primary OHS challenges or issues that women face in the occupations identified from Research Question 2?

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. It provides a quantitative assessment of findings and a synthesis of information from previously published studies.

2.1. Search Strategy

This review was conducted with a systematic search of articles published in PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) during the period of 2010–2021. Title and abstract searches were implemented in all of these electronic databases. Three sets of keywords were used in the search strategy: safety (occupational injury); health (occupational disease; occupational illness; job analysis; industrial health; employee health; industrial hygiene); and woman. The Boolean logic operators including “AND” and “OR” were applied to combine the keywords [39].

Then, the search results were entered into the EndNote version 20 software, and duplicate articles were automatically deleted. After removing duplicates, 1315 articles remained.

2.2. Selection of Studies

Two researchers independently reviewed articles. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered to determine the eligibility of studies:

- Only English-language articles were included. Therefore, articles in languages other than English were excluded.

- Only articles with full-text availability were included.

- Review articles, editorials, letters to the editor, articles presented at seminars and conferences, reports and books were excluded.

- Only articles that used primary data, with all or part of their participants from the female population, were included.

- Studies that included both women and men in their research but presented results in a generalized manner were excluded from the study because the focus of this review is on women’s OHS. Therefore, studies that did not present results focused on women were excluded. It is worth noting that this review does not intend to compare the OHS challenges faced by men and women. Instead, its focus is specifically on women.

- Studies that were unrelated to the human population (e.g., animal population) were excluded.

To determine which articles were within the research subject area, the article titles and abstracts were reviewed. After confirming that the year and subject matter were within the scope of this review, the articles were examined more closely. Additionally, the reference lists of articles were reviewed; however, no additional studies were added to this review.

2.3. Quality Assessment of Articles

The researchers assessed the quality of the all the articles using the quality assessment checklist provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The JBI checklist evaluates ten criteria for qualitative studies through critical appraisal questions and provides an overall appraisal decision at the end [40].

2.4. Screening Process

The initial search for studies was performed by two researchers who also independently carried out data extraction and a quality control evaluation. In the case of any inconsistency, the two researchers had a discussion to reach a consensus and make a final decision.

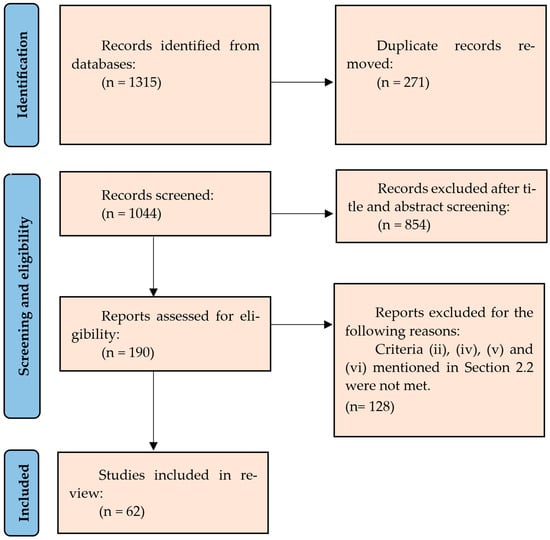

As previously mentioned (Section 2.1), 1315 studies were found after searching the databases. After completing three phases of checking (duplicate checking; title and abstract checking; full-text checking), 62 articles were entered into the final analysis stage. Additionally, these 62 articles were assessed using the JBI tools, and all of them met the criteria for inclusion in this review. Furthermore, as previously mentioned in Section 2.2, the lists of references of the included articles were reviewed to add related studies. However, no studies were added. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA-based flowchart of the studies included in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-based flowchart of the studies included in the review.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results Based on the Literature

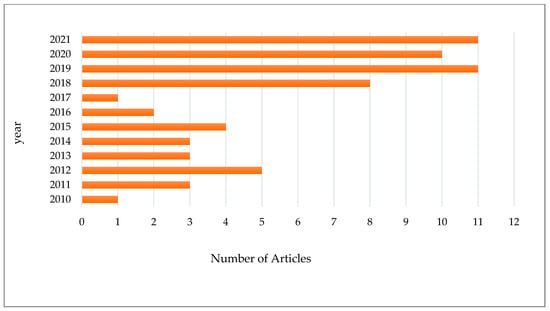

Considering the studies included in this review, Figure 2 shows the trend of publishing these types of articles (i.e., OHS-related studies that used primary data, with all or part of their participants from the female population, and results focused on the female population) during the studied years. As shown, after 2017, there is an increasing trend of studies into women’s OHS.

Figure 2.

The number of articles published in the field of women’s OHS during the period of 2010–2021.

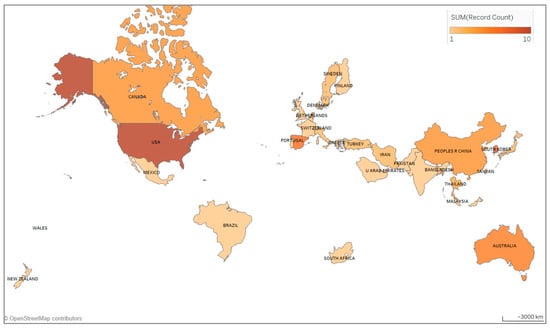

Between 2010 and 2021, 33 countries published papers on women’s OHS. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of publications by country.

Figure 3.

Distribution of publications by countries.

Through the current study, the ten most productive countries were identified, with a total of 46 published papers. The USA and South Korea are considered the most effective countries with 10 and 7 publications, respectively. China (People’s Republic of China) has an average of 46 citations per document but is ranked sixth among the ten most productive countries. Table 1 shows the number of documents and citations for each country separately.

Table 1.

The number of documents and citations of top 10 countries.

Furthermore, a co-authorship analysis was conducted using the VOSviewer to illustrate the countries’ collaboration. Figure 4 depicts the cooperative network among the various countries. A network of seven nodes was obtained based on the cooperation analysis of countries from 2010 to 2021, with each node representing an author’s country. In the map, the font size represents the frequency of collaboration with other countries, each line indicates the collaboration between the countries, and the darkness of the line represents the level of collaboration. Therefore, as shown in the map, USA, Australia, and the Netherlands have the largest rates of cooperation, engaging more than other countries in the field of women’s OHS. The greater the international cooperation of a country, the greater its academic influence of that country in that field. Countries sharing the same color were associated with similar research areas. For instance, Bangladesh, Malaysia, The Netherlands, and South Africa were grouped in Cluster 1; Australia, England, and Thailand in Cluster 2; Canada, United Arab Emirates, and USA in Cluster 3; Greece, Pakistan, and China in Cluster 4; France and Wales in Cluster 5; and Mexico and Spain in Cluster 6. The countries’ collaboration links are also displayed on the map.

Figure 4.

Collaboration Map of Countries Based on Co-authorship Analysis.

The 62 papers on women’s OHS were published in 39 journals. “Safety and Health at Work” and “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health” had the highest number of publications. The top 10 journals based on literature citations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The number of documents and citations for the top 10 journals.

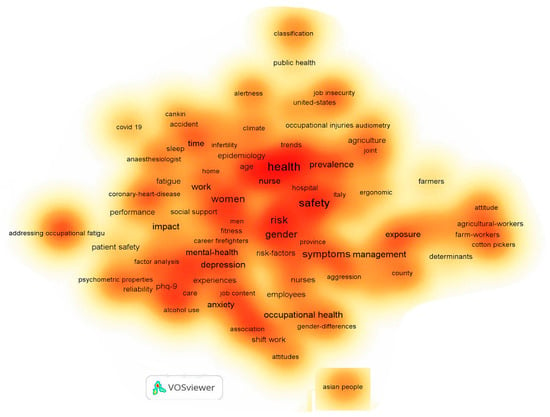

Additionally, Figure 5 represents a cluster density map of co-occurring keywords mapped using VOSviewer. Sixteen major keyword clusters were identified based on the correlation of keywords. Such cluster density maps are created based on the weight and number of surrounding elements for each item. As the density of the representative cluster increases, the frequency of keyword co-occurrence also increases. The minimum threshold for the co-occurrence of keywords was set at five. By analyzing the co-occurrence of keywords, a total of 422 keywords were identified, of which 16 met this threshold. Table 3 lists the ten most frequently occurring keywords along with their total link strengths. In terms of search terms, “health”, “safety” and “stress” were the most frequently used keywords.

Figure 5.

Cluster density map of co-occurring keywords.

Table 3.

The top 10 co-occurring keywords.

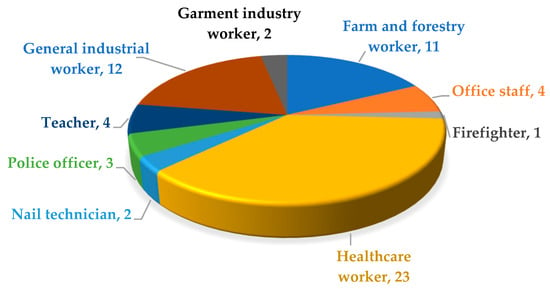

3.2. Results Related to Occupations in Specific Sectors as Found in the Literature

Figure 6 shows the number of articles published in the field of women’s OHS focusing on occupations during the period of 2010–2021. The majority of the included studies (23 articles) focus on the healthcare sector. The farm and forestry sector is second with 11 articles. These results indicate that the healthcare sector received more attention from researchers due to its significance and the various OHS issues present in this extensive occupational setting. It is worth noting that the industrial sector was not ranked second because it encompasses various sectors such as mining, construction, and transportation.

Figure 6.

The abundance of articles published in the field of women’s OHS focusing on occupations during the period of 2010–2021.

In addition, Table 4 shows a full description of the characteristics (i.e., author, year, country, occupation, type of study, target of the study, and number of women investigated) for all 62 included articles.

Table 4.

Summary of the included articles.

Additionally, Table 5 illustrates the OHS challenges or issues for women identified in the literature for each occupation within specific sectors. These challenges or issues are discussed in Section 4. Stress, fatigue, MSDs and pain, sleep disorders, long working hours, depression and anxiety, workplace violence, and allergies and skin problems are among the most common OHS challenges or issues faced by women in various occupations, as highlighted in the included studies (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Matrix of OHS challenges or issues for women by occupation.

4. Discussion

4.1. OHS Challenges or Issues for Women in Specific Occupations Based on the Literature

According to Section 3.2, the included studies examined women’s OHS in specific occupations. These included HCWs, farm and forestry workers, office staff, teachers, firefighters, police officers, nail technicians, workers in the clothing industry, and general industrial workers. Subsequently, OHS challenges or issues (Table 5) faced by women in these occupations are discussed based on the findings of the included studies.

4.1.1. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female HCWs

One occupation mentioned in most of these studies devoted to the OHS of women is that of HCWs, particularly in relation to organizational culture, burnout, job satisfaction, and stress appraisal. The results indicated that the following issues or challenges endanger the health and safety of female HCWs:

- Female HCWs are at high risk of job stress and job burnout, both of which can lead to less effective nursing care and psychological problems (11 studies);

- Three studies conducted between 2010 and 2021 considered workplace violence as a factor affecting the health level of female HCWs. Overall, the results showed that female HCWs were exposed to varying degrees of verbal, organizational, sexual, and physical violence;

- Another factor affecting HCWs health is fatigue due to high workload, long hours of work, and stress. Among the studies conducted in the field of fatigue, two were found in this case;

- Sleep is an essential factor that plays an important role in health. Sleep, as a physiological mechanism of the body, can restore lost power and eliminate fatigue caused by activity. Sleep disturbances can lead to physical and mental problems and a decrease in performance. One case study related to the sleep health of women working in the healthcare sector showed the results of sleep disturbances in working women;

- Two studies investigated the use of PPE related to reduced employee health levels;

- HCWs are at risk of ischemic heart disease (one study).

Table 6 shows a summary of included studies related to each of these issues or challenges.

Table 6.

A summary of studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female HCWs.

According to the findings, the OHS challenges or issues faced by women in the healthcare sector seriously affect mental health. Various factors contribute to stress, fatigue, and sleep disorders, including the nature of work in this occupational setting, exposure to mortality, staffing shortages, work pressure, and physically demanding tasks. Workplace violence is also a significant OHS issue among HCWs, having an adverse effect on their mental health. Risk factors associated with violence include working in community-based settings and working with unstable individuals. Consequently, HCWs experience violence from organizational threats, patients, and patients’ relatives. Therefore, mental health is crucial in the healthcare sector, and relevant risk factors should be eliminated to improve mental health among HCWs.

The included studies, based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, predominantly focused on the female HCWs’ occupational health issues. Based on the obtained findings, the existing research based on primary data and focused on safety issues among female HCWs is limited. However, it is obvious that existing occupational health issues can endanger the safety of HCWs and lead to injuries and fatalities. Stress, fatigue, and sleep disturbances are factors affecting health that ultimately lead to accidents, a decreased quality of life, and increased disease. Uymaz et al. [49] investigated the accidents experienced by HCWs. Of the participants, 44% and 34% experienced accidents and near misses, respectively. A meaningful relationship was found between gender and the occurrence of occupational accidents (p < 0.05). To investigate the quality of life of HCWs, Kheiraoui et al. [91] studied a population of 57% women with an average age of 39 years. In that study, the general health score of women was 68, and the mean score of physical performance was 92.6. Vitality received the lowest score with an average of 57, and mental health received a mean score of 67. A meaningful relationship was found between gender and vitality, body pain, social function, and mental health (p = 0.005). Additionally, results from Villar et al. [63] into work conditions and absenteeism during pregnancy in HCWs showed that the following risk factors caused an increase in absences during pregnancy: biological factors (58% absence), ergonomics (54%), and safety factors (42%), followed by psychological factors (34%) and physical and chemical factors (6%).

4.1.2. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Farm and Forestry Workers

Second to HCWs, female agricultural workers were among the most studied (11 articles). In the studies on the health and safety of women working in the agriculture sector, poisoning with pesticides was the most frequent OHS issue. Pesticides are regarded worldwide as the most effective, fastest and cheapest method of pest control. According to documented statistics, the rate of poisoning with pesticides in developing countries is 13 times higher than in developed countries [100]. In fact, employees in the agriculture sector are directly and indirectly dealing with agricultural toxins in a variety of ways that can have both positive and negative effects on their health.

In addition, according to the analysis of the health and safety risk factors of female farm and forestry workers presented in the included studies, the next categories of frequency were, MSDs, auditory and respiratory disorders, and other issues (e.g., slips, trips, and falls, the use of PPE and cuts). It is worth noting that products cultivated on farms can sometimes have adverse effects on women’s health. For example, Paul et al. [43] investigated the impact tobacco exposure has on female farm workers. Table 7 shows a summary of included studies related to each of these issues or challenges faced by female farm and forestry workers.

Table 7.

A summary of studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female farm and forestry workers.

As mentioned above, pesticide poisoning and MSDs were identified as the most frequent OHS issues among women in the farm and forestry sector. Protecting female workers in this sector involves precisely identifying and eliminating the contributing factors to pesticide poisoning and MSDs. For example, the factors contributing to pesticide poisoning include poor pesticide safety training, inadequate training on the proper use of PPE, and insufficient hygiene measures. The factors contributing to MSDs are related to the nature of the work and include high volumes of physical activity, prolonged static postures, and heavy load handling (e.g., large animal handling).

4.1.3. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Office Staff

The administrative work environment is composed of physical, psychological and social stimuli, each of which can be considered a cause of fatigue. These sources of stress and pressure can undermine physical health, mental health, and performance, and can reduce the health levels of women in administrative staff jobs [101]. Another important issue that women face is pregnancy. This is one of the most sensitive and vital periods of a woman’s life [102], during which she experiences changes due to hormonal, psychological, and physical factors [103]. Another problem office workers face is long working hours. According to European Union reports, poor health outcomes are associated with long working hours, which can be due to lack of social welfare, family responsibilities, and being the breadwinner. The last issue found, based on the literature, is MSDs.

Four studies focused on the OHS of women working in administration. Table 8 presents a summary of included studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female office staff.

Table 8.

A summary of included studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female office staff.

4.1.4. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Firefighters

Firefighters in rescue activities are subject to intense psychological pressure. The main occupational risk factors among women working in fire departments are time (20 h per week), stress in the workplace, violence in the workplace, strenuous physical activity, exposure to noise and chemicals, and working with men for prolonged amounts of time [104,105]. Watkins et al. [35] studied the health of women, finding that 49% of working women in North America complained of back injuries, 51% of lower limb injuries, and 45% of heat-related illnesses. A significant number (39%) of women considered the menstrual cycle and menopause as a factor affecting their work; 36% were worried about their ability to meet their job needs in the future; 50% reported “strength and conditioning support”; and 21% cited lack of sports facilities as their problem. The availability of PPE for women in the United Kingdom was 66%, compared to 42% in other groups.

4.1.5. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Police Officers

Police officers experience high levels of stress, anxiety and stimulation. Their profession is described as one of the most stressful jobs in the world because physical threats in the operational area are very high. Alexopoulos et al. [85] revealed that, 84% of female officers were more or less satisfied with their jobs, and only 35% were satisfied with their salaries. Most (78%) of the women described their health status as good to excellent, and 5% had a poor health status. In that study, significant relationships were found between physical disorders, stress, insomnia and depression. Ma et al. [62] sought to evaluate stress and sleep quality. The results indicated that female police officers have high stress levels. Only 13% of female police officers worked at night; 3% used “sleep medicine”, and 48% had a high workload. Female police officers reported a significant rating score for physical and psychological danger, averaging 48.9 (±25.1). Carleton et al. [56] assessed mental disorders in correctional staff. The findings indicated that screening results for mental disorders in female officers were 59.4% positive and that mental disorders occurred more often in women than in men.

4.1.6. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Teachers

Among the articles reviewed in this study, four looked at the safety and health of women working in education. One of the problems found based on the literature was fatigue. Another issue was stress due to workplace violence. Among other threatening factors for teachers is voice disorder, for which they experience an increased risk due to the prolonged use of their voice. The prevalence of vocal diseases is between 11% and 81%. These voice problems may lead to a reduced quality of teaching and an increased personal and emotional burden on teachers [92]. Table 9 presents a summary of the included studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female teachers.

Table 9.

A summary of included studies related to each of the OHS issues or challenges faced by female teachers.

4.1.7. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Nail Technicians

Nail technicians are very vulnerable to occupational hazards, as they are exposed to toluene and formaldehyde. In addition to causing skin problems, allergies and asthma, these chemicals are carcinogenic (present a risk of cancer). Additionally, prolonged sitting, improper posture, and MSDs can cause neck pain and back pain [106]. Two studies were conducted in the field of the safety and health of women working in nail salons. Dang et al. [50] aimed to investigate the level of health and safety of employees and to raise health and safety awareness among nail technicians. Three important factors affecting the health of nail technicians were identified: work-related stress factors such as the lack of policies and regulations, the lack of formal training, and insufficient knowledge; exposure risks in the workplace that include inhaling fumes from manufacturing materials and nail products as well as poor ergonomics; and the need for interventions at the individual and organizational levels, such as for a new educational policy. Furthermore, Seo et al. [67] studied female nail technicians and found that 46% of them were concerned about their health and reported complications such as stress (46%), pain (38%), allergies (35%), skin problems (35%) and MSDs (34%). Preventing these health symptoms would require, as priorities, the implementation of new ventilation regulations against long-term exposure to toxic chemicals, changes to public health policy, and staff training with an emphasis on increasing the use of PPE.

4.1.8. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female Workers in the Clothing Industry

Two studies into the OHS of workers in the apparel sector highlighted the factors that threaten women’s health in this profession. Akhter et al. [68] investigated violence against women working in the garment industry and demonstrated a high incidence of verbal and physical abuse by supervisors who try to exert control over female workers by yelling, insulting, and speaking harshly. The most common physical abuses included slapping, pinching, and pushing. Disregard for the physical conditions of the workers (lack of proper ventilation, lack of first aid boxes, high noise levels), long hours of work, and threats to the proper rehabilitation of workers after injury and accident at work are among the health and safety problems faced by women workers in this industry. Regarding female weavers, Aiswarya and Bhagya [48] found that more than 61% had occupational health complications. Of those, 93.4% had joint and muscle pain due to improper posture, continuous movement of hands and feet, and long hours of sitting. The majority had pain in the hands, arms, shoulders, and neck; 20% had respiratory problems due to the presence of fiber dust; 11.5% suffered from skin diseases, dermatitis, and conjunctivitis due to being part of the dyeing and spinning department; and 41% suffered from depression, with a high prevalence of anxiety among women in this work unit.

4.1.9. OHS Challenges or Issues Faced by Female General Industrial Workers

Regarding the OHS of female workers in other industries or units, including mining, construction, air transportation, and welding and electrical units, it was found that the following topics were studied: safety conditions of women’s work, mental disorders, long work hours, and PPE. Table 10 demonstrates the OHS issues faced by female workers in each of these industries or units.

Table 10.

The OHS issues faced by female general industrial workers.

In addition to the above-mentioned industries or units, some other studies investigated the OHS of female workers in general, rather than focusing on a specific industry. The results of those studies are as follows:

Honda et al. [81] studied the mental health of Japanese workers with multiple roles and found that women’s mental health was weaker than men’s. Married women had better mental health than unmarried women, and those who were responsible for their families had better mental health than those who only held a job. Chun et al. [57] assessed the level of depression and found that 26.5% of women were depressed and more than 50% had high workloads. Herrero et al. [94] examined stress and revealed that 22.10% of female workers had at least three stress-related signals. Young female workers had less stress than older female workers. Across the different age groups, women experienced more stress than men in the same age groups. After using a Bayesian network method to analyze the results, the factors found to most affect stress levels in women were, in descending order of importance, “overwork” (28.51%), “tight deadlines” (23.38%), “quick work” (22.86%), “complex tasks” (20.93%), “intellectual demanding” (19.18%), “repetitive tasks” (17.47%), and “attention level” (15.65%).

In the study of the physical and mental problems of Korean waged workers in different job categories, unskilled female workers experienced the most physical and mental problems. These were most frequently diabetes, high blood lipids, arthritis, depression, and suicidal thoughts. The most common disease among managers and specialists was cardiovascular disease, and among skilled female workers and after-sales service workers, it was high blood lipids and high blood pressure [69].

Berecki-Gisolf et al. [90] found that 1.8% of women in Thailand had been impaired during the previous 12 months and that women who worked more than 48 h per week, and those who had a lower income, were exposed to more risk. Also, women who worked part-time reported less victimization than women who worked full-time.

Lederer et al. [93] evaluated the social, physical, and organizational factors related to women’s work. The results showed that 64% suffered a high perceived physical workload, 38% had an average level of job satisfaction, and 15% were dissatisfied. In grading job security, the results depicted high job insecurity. Furthermore, 56.2% of the women were not aware of the safety and health programs in their workplace. They complained of pain in the back area (54%) and in the neck and upper extremities (35.5%). Also, the nature of pain in MSDs was 79% from vertebral injuries and 21% from repetitive movements in work.

Ahn et al. [44] examined the relationship between long working hours and infertility, and found that infertility is related to long hours of work in workers under 40 years of age. Furthermore, Wirtz et al. [95] found that with increased working hours, the number of injuries women reported increased.

4.2. Strengths Impact, and Future Research Avenues

In terms of strengths, this review covers the studies that utilized primary data, with all or part of their participants being female. Focusing on such specific studies allowed us to gain an understanding of the health and safety issues directly raised by the female population in the workplace. Additionally, this approach enabled us to understand the extent of attention that researchers have given to women’s OHS through empirical studies, rather than relying on secondary data or theoretical and conceptual studies.

Furthermore, the detailed discussion in Section 4.1 highlights that stress, fatigue, MSDs and pain, sleep disorders, long working hours, depression and anxiety, workplace violence, and allergies and skin problems are the most common OHS challenges or issues faced by women across different occupations, as indicated by the included studies. However, some of the factors affecting women’s OHS in specific sectors may not be as relevant in other sectors. For example, female farm and forestry workers may be at risk of pesticide poisoning; female workers in the clothing industry may develop conjunctivitis from working in dyeing and spinning departments; female teachers may experience voice disorders due to prolonged voice use; and female tobacco farmers may encounter digestive problems. These findings enable organizations, employers, and policymakers to pay more attention to women’s physical and physiological characteristics and to implement more efficient measures and strategies for protecting women’s health and safety in sectors with varying types of work. Additionally, these findings will help future OHS researchers identify the most critical research needs concerning the protection of female workers in various occupational settings. They will also assist in identifying industry sectors that have not yet been studied.

The obtained findings also indicate avenues for future research. This study provides insights for drawing more attention to the research topic of women’s OHS, highlighting the OHS challenges faced by women in workplaces. The field of OHS is broad. While this review focused on specific studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, future studies should examine women’s OHS more precisely by focusing on specific issues. This approach can help develop appropriate control measures for each specific issue to promote women’s health and safety in the workplace. Additionally, while the obtained findings included women’s OHS issues in several specific occupations (e.g., HCWs, farm and forestry workers, office staff, teachers, firefighters, police officers, nail technicians, workers in the clothing industry, and general industrial workers), several opportunities for future studies are recommended to precisely examine women’s health and safety issues in different occupations separately. For example, reviewing women’s risks in farm work, healthcare, manufacturing, transportation, and construction, especially in developing countries, could be beneficial for prevention purposes by accurately identifying the risk to women in each industry, considering the varied nature of work in each. Additionally, this approach allows for a precise focus on the OHS challenges faced by women in a specific sector. It also provides an opportunity to discuss in greater detail common OHS issues, as well as certain sector-specific factors affecting women’s OHS that may not be as relevant in other sectors, such as ethical stress in the healthcare sector. Ethical issues related to “protecting patient rights”, “autonomy and informed consent”, “organizational structures”, and “standardization and the development of health care system” can create stress among healthcare providers [107,108] and “a conflict between their professional and personal ethical values” [109]. Consequently, the development of programs to teach ethics and the creation of national and global strategies are essential to address ethical stress, to enhance the provision of “quality patient care”, and to retain skilled personnel [107,110].

Since the focus of this review is on women’s OHS and not solely on the health status of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, some studies (e.g., pandemic-related articles) were likely excluded. This exclusion is also due to the inclusion criteria being limited to articles that used primary data with all or part of their participants from the female population. Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic is a specific topic worthy of a targeted systematic review in future research, particularly given the substantial number of articles published on the subject.

Finally, the majority of studies included in this review focused on women’s health in the workplace. Therefore, future research should prioritize women’s safety to prevent workplace injuries.

5. Conclusions

In today’s world, women play active roles in various industries. The physical and physiological characteristics of women have an impact on their health and safety in the workplace. These characteristics should receive the attention needed to mitigate occupational diseases and occupational injuries and to provide a healthy and safe workplace for women. In this regard, this study aimed to review and analyze OHS-related research studies that used primary data, with all or part of their participants being female, to investigate the status of research on women’s health and safety, as well as the OHS challenges or issues that women face in different occupations. During the period of 2010–2021, an increasing trend in publishing such articles in the field of women workers’ OHS could be seen. The studies included in this review investigated women’s OHS in specific professions, such as HCWs, farm and forestry workers, office staff, teachers, firefighters, police officers, nail technicians, workers in the clothing industry, and general industrial workers. Most of the studies in this area were related to women working in the healthcare sector and agricultural industry. Some OHS issues identified in the literature, such as job stress, fatigue, MSDs and pain, sleep, workplace violence, as well as allergies and skin problems, are common across different occupations. However, certain OHS issues are specific to particular occupations due to the nature of the work. For instance, female teachers may suffer from voice disorders due to prolonged voice use, while female farmers working in tobacco planting farms may experience digestive problems. Additionally, the findings emphasize the importance of addressing women’s mental health across various occupational sectors.

Finally, based on the knowledge gained, limited research has been conducted on women’s OHS. This is particularly true for the new jobs in which women are engaged, and this has led to unsafe conditions, in which the threats to women’s health and safety remain unknown. Appropriate and preventive control measures have not yet been suggested to provide safer and healthier workplaces for women in various sectors. The findings of this study shed light on women’s OHS issues and challenges. Additionally, this paper serves as a foundation and a guideline for researchers to develop further research in this area. Moreover, there were certain limitations in conducting this review. This study used general keywords related to the field of women’s OHS. This review was also limited to studies that used the primary data, with all or part of their participants being female. Consequently, some studies might not have been included in the search, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of the list of OHS challenges and issues faced by women in various industries. Therefore, further research could focus on women’s OHS issues and challenges in each industry separately and comprehensively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J., S.B. and A.H.; methodology, S.B. and M.J.; validation, M.J. and A.H.; formal analysis, S.B. and A.H.; investigation, S.B., M.J. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.J. and A.H.; supervision, M.J.; project administration, A.H. and M.J.; funding acquisition, M.J. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (extracted from a doctoral dissertation, approved code of ethics: IR.SUMS.SCHEANUT.REC.1402.004).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the financial support of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elsan, M. Citizenship Rights from the View Point of Iranian Law and Global Citizenship. Hum Rts. 2008, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimzade Khoei, P.; Rajabzadeh, A.; Sotode, S. Promoting the human rights status of women by emphasizing the Iranian legal system. Mod. Jurisprud. Law 2021, 2, 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Flaspöler, E.; Hauke, A.; Koppisch, D.; Reinert, D.; Koukoulaki, T.; Vilkevicius, G.; Žemės, L.; Águila Martínez-Casariego, M.; Baquero Martínez, M.; González Lozar, L. New Risks and Trends in the Safety and Health of Women at Work. 2013. Available online: https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/31145/1/PubSub8694_Hassard.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Ahmadi, B.; Tabibi, J.; Mahmoodi, M. Designing a model of administration structure for Iranian women’s health development. Soc. Welf. Q. 2006, 5, 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health and Human Rights; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Knowledge for Better Health: Strengthening Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kasle, S.; Wilhelm, M.S.; Reed, K.L. Optimal health and well-being for women: Definitions and strategies derived from focus groups of women. Women’s Health Issues 2002, 12, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics (US); National Center for Health Services Research. Health, United States; US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2011.

- Somani, T. Importance of educating girls for the overall development of society: A global perspective. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2017, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M.; McGrath, S.J.; Meleis, A.I.; Stern, P.; DiGiacomo, M.; Dharmendra, T.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Campbell, J.C.; Hochleitner, M.; Messias, D.K.; et al. The health of women and girls determines the health and well-being of our modern world: A white paper from the International Council on Women’s Health Issues. Health Care Women Int. 2011, 32, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, B.; Babashahy, S. Women health management: Policies, research, and services. Soc. Welf. Q. 2013, 12, 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, H.; Azam, M.; Zakariya, S.K. The impact of environmental quality on public health expenditure in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Adv. Bus. Soc. Stud. 2016, 2, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, V.K. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1994, 20, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczyk, K.; Jentsch, B.; Sailer, J.; Schier, M. Female-breadwinner families in Germany: New gender roles? J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 1731–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.S. Occupational and Environmental Health: Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A. Globalization of the local/localization of the global: Mapping transnational women’s movements. Meridians 2000, 1, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, L.; De Grosbois, S.; Wesseling, C.; Kisting, S.; Rother, H.A.; Mergler, D. Pesticide usage and health consequences for women in developing countries: Out of sight out of mind? Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 8, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, Q.U.A.; Wagan, S.A.; Chunyu, D.; Shuangxi, X.; Jingdong, L.; Damalas, C.A. Health problems from pesticide exposure and personal protective measures among women cotton workers in southern Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.M. Pesticide exposure and women’s health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2003, 44, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, V.; Prakash, Y. Sex differences in pulmonary anatomy and physiology: Implications for health and disease. Sex Differ. Physiol. 2016, 10, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, E. Physiology of the skin—Differences between women and men. Clin. Dermatol. 1997, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legato, M.J.; Leghe, J.K. Gender and the heart: Sex-specific differences in the normal myocardial anatomy and physiology. Princ. Gend.-Specif. Med. 2010, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.E.J.; MacDougall, J.; Tarnopolsky, M.; Sale, D. Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1993, 66, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; Jones, B.H.; Van Arsdale, S.J.; Kelly, K.; Kraemer, W.J. Operational physical performance and fitness in military women: Physiological, musculoskeletal injury, and optimized physical training considerations for successfully integrating women into combat-centric military occupations. Mil. Med. 2016, 181 (Suppl. S1), 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipscomb, H.J.; Dement, J.M.; Epling, C.A.; Gaynes, B.N.; McDonald, M.A.; Schoenfisch, A.L. Depressive symptoms among working women in rural North Carolina: A comparison of women in poultry processing and other low-wage jobs. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2007, 30, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.M.; Chen, J.J.; Kovach, J.S. The relationship between body iron stores and blood and urine cadmium concentrations in US never-smoking, non-pregnant women aged 20–49 years. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldin, O.P.; Mattison, D.R. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugarten, J.; Golestaneh, L. Gender and the prevalence and progression of renal disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013, 20, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnest, G.S.; Flesch, J.P.; Hagedorn, R.T.; Hayden, C.S.; Watkins, D.S. Control of Exposure to Perchloroethylene in Commercial Drycleaning (Ventilation). 1997. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13416 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Wilson, R.T.; Donahue, M.; Gridley, G.; Adami, J.; Ghormli, L.E.; Dosemeci, M. Shared occupational risks for transitional cell cancer of the bladder and renal pelvis among men and women in Sweden. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2008, 51, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.M.; Ou Shu, X.; Jin, F.; Dai, Q.; Ruan, Z.; Thompson, S.J.; Hussey, J.R.; Gao, Y.T.; Zheng, W. Occupations and breast cancer risk among Chinese women in urban Shanghai. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2002, 42, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langseth, H.; Andersen, A. Cancer incidence among women in the Norwegian pulp and paper industry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1999, 36, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbulyan, M.A.; Ilychova, S.A.; Zahm, S.H.; Astashevsky, S.V.; Zaridze, D.G. Cancer mortality among women in the Russian printing industry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1999, 36, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewdok, T.; Sirisawasd, S.; Taptagaporn, S. Agricultural risk factors related musculoskeletal disorders among older farmers in Pathum Thani Province, Thailand. J. Agromedicine 2021, 26, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, E.R.; Walker, A.; Mol, E.; Jahnke, S.; Richardson, A.J. Women firefighters’ health and well-being: An international survey. Women’s Health Issues 2019, 29, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, L.; Baecke, M.; Grosjean, M.; Isaie, H.; Gregoire, Y.; Barbieux, C.; Tock, R.; Verbrugghe, M. Screening of work-related musculoskeletal upper limb disorders using the SALTSA protocol: A work-site study in Belgium. Workplace Health Saf. 2021, 69, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hempel, S.; Xenakis, L.; Danz, M. Systematic Reviews for Occupational Safety and Health Questions: Resources for Evidence Synthesis. 2016. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1400/RR1463/RAND_RR1463.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research 2017. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Ramirez-Moreno, J.M.; Ceberino, D.; Plata, A.G.; Rebollo, B.; Sedas, P.M.; Hariramani, R.; Roa, A.M.; Constantino, A.B. Mask-associated ‘de novo’headache in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderhalden-Zellweger, A.; Probst, I.; Mercier, M.-P.P.; Danuser, B.; Krief, P. Protecting pregnancy at work: Normative safety measures and employees’ safety strategies in reconciling work and pregnancy. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Sultana, N.N.; Nazir, N.; Das, B.K.; Jabed, M.; Nath, T.K. Self-reported health problems of tobacco farmers in south-eastern Bangladesh. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, M.Y.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, W. The Association Between Long Working Hours and Infertility. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattori, A.; Cantù, F.; Comotti, A.; Tombola, V.; Colombo, E.; Nava, C.; Bordini, L.; Riboldi, L.; Bonzini, M.; Brambilla, P. Hospital workers mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Methods of data collection and characteristics of study sample in a university hospital in Milan (Italy). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghihi, M.; Farshad, A.; Abhari, M.B.; Azadi, N.; Mansourian, M. The components of workplace violence against nurses from the perspective of women working in a hospital in Tehran: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelnicki, A.M.; Jamshidi, L.; Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N. Exposures to potentially psychologically traumatic events among nurses in Canada. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiswarya, A.; Bhagya, D. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on the lifestyle and dietary diversity of women handloom workers. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uymaz, P.; Ozpinar, S. Exposure to occupational accidents and near miss events of the healthcare workers in a university hospital. ASEAN J. Psychiatry 2021, 22, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, J.V.; Rosemberg, M.-A.S.; Le, A.B. Perceived work exposures and expressed intervention needs among Michigan nail salon workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursadeqiyan, M.; Arefi, M.F.; Khaleghi, S.; Moghaddam, A.S.; Mazloumi, E.; Raei, M.; Hami, M.; Khammar, A. Investigation of the relationship between the safety climate and occupational fatigue among the nurses of educational hospitals in Zabol. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.Y.; Lee, C.G.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, K.Y.; Ryu, S.Y.; Song, H.S. Work-related risk factors of knee meniscal tears in Korean farmers: A cross-sectional study. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani-Issa, W.; Radwan, H.; Al Marzooq, F.; Al Awar, S.; Al-Shujairi, A.M.; Khasawneh, W.; Albluwi, N. Salivary cortisol, subjective stress and quality of sleep among female healthcare professionals. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, R.; Chen, N.; Huang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y. Risk assessment of workplace violence towards health workers in a Chinese hospital: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harthi, M.; Olayan, M.; Abugad, H.; Wahab, M.A. Workplace violence among health-care workers in emergency departments of public hospitals in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Ricciardelli, R.; Taillieu, T.; Mitchell, M.M.; Andres, E.; Afifi, T.O. Provincial correctional service workers: The prevalence of mental disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, H.-r.; Cho, I.; Choi, Y.; Cho, S.-i. Effects of emotional labor factors and working environment on the risk of depression in pink-collar workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilella, S.B.; Zarceño, E.L.; Serrano Rosa, M.A. Mood, Physical, and Mental Load in Spanish Teachers of Urban School: The role of intensive or split shift. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Björklund, C.; Bergström, G.; Nybergh, L.; Schäfer Elinder, L.; Stigmar, K.; Wåhlin, C.; Jensen, I.; Kwak, L. Health and work environment among female and male Swedish elementary school teachers—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrosen, Y.; Lagrosen, S. Gender, quality and health–a study of Swedish secondary school teachers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.-J. Hearing impairment among Korean farmers, based on a 3-year audiometry examination. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.C.; Hartley, T.A.; Sarkisian, K.; Fekedulegn, D.; Mnatsakanova, A.; Owens, S.; Gu, J.K.; Tinney-Zara, C.; Violanti, J.M.; Andrew, M.E. Influence of work characteristics on the association between police stress and sleep quality. Saf. Health Work 2019, 10, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar, R.; Serra, L.; Serra, C.; Benavides, F.G. Working conditions and absence from work during pregnancy in a cohort of healthcare workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, L.J.; Cortes, M.d.C.J.W.; Dias, E.C.; de Meira Fernandes, F.; Gontijo, E.D. Burnout and job satisfaction among emergency and intensive care providers in a public hospital. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2019, 17, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gander, P.; O’Keeffe, K.; Santos-Fernandez, E.; Huntington, A.; Walker, L.; Willis, J. Fatigue and nurses’ work patterns: An online questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 98, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, B.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, S. The association between occupational stress and psychosomatic wellbeing among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Medicine 2019, 98, e15836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.Y.; Chao, Y.-Y.; Strauss, S.M. Work-related symptoms, safety concerns, and health service utilization among Korean and Chinese nail salon workers in the greater New York City Area. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2019, 31, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, S.; Rutherford, S.; Chu, C. Sufferings in silence: Violence against female workers in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh: A qualitative exploration. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519891302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, N.-S.; Lee, B.-K.; Park, J.; Kim, Y. Relationship of occupational category with risk of physical and mental health problems. Saf. Health Work 2019, 10, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongtip, P.; Nankongnab, N.; Mahaboonpeeti, R.; Bootsikeaw, S.; Batsungnoen, K.; Hanchenlaksh, C.; Tipayamongkholgul, M.; Woskie, S. Differences among Thai agricultural workers’ health, working conditions, and pesticide use by farm type. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2018, 62, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Han, B. Work sectors with high risk for work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korean men and women. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.d.; Silva, M.T.; Galvão, T.F.; Lopes, L.C. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms: An analysis of professionals in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Medicine 2018, 97, e13364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuetzle, K.V.; Pavlin, B.; Smith, N.A.; Weston, K.M. Survey of occupational fatigue in anaesthetists in Australia and New Zealand. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2018, 46, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimi, H.; Majd Teimouri, Z.; Mousavi, S.; Kazem Nezhad Leyli, E.; Jafaraghaee, F. Individual protection adopted by ICU nurses against radiation and its related factors. J. Holist. Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 28, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Starc, J. Stress factors among nurses at the primary and secondary level of public sector health care: The case of Slovenia. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tei-Tominaga, M.; Nakanishi, M. The influence of supportive and ethical work environments on work-related accidents, injuries, and serious psychological distress among hospital nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, N.; Arrandale, V.; Beach, J.; Galarneau, J.-M.F.; Mannette, A.; Rodgers, L. Health and work in women and men in the welding and electrical trades: How do they differ? Ann. Work Expo. Health 2018, 62, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Kamardeen, I. Work stress is a threat to gender diversity in the construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Räsänen, K.; Chae, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, K.; Lee, K. Farm work–related injuries and risk factors in South Korean agriculture. J. Agromed. 2016, 21, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.S.; Fan, J.Y. Nurse practitioner job content and stress effects on anxiety and depressive symptoms, and self-perceived health status. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Abe, Y.; Date, Y.; Honda, S. The impact of multiple roles on psychological distress among Japanese workers. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, M.; Carvalhais, J.; Teles, J. Irregular working hours and fatigue of cabin crew. Work 2015, 51, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botha, D.; Cronjé, F. Occupational health and safety considerations for women employed in core mining positions. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allesøe, K.; Holtermann, A.; Aadahl, M.; Thomsen, J.F.; Hundrup, Y.A.; Søgaard, K. High occupational physical activity and risk of ischaemic heart disease in women: The interplay with physical activity during leisure time. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, E.C.; Palatsidi, V.; Tigani, X.; Darviri, C. Exploring stress levels, job satisfaction, and quality of life in a sample of police officers in Greece. Saf. Health Work 2014, 5, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, M.; Davas, A.; Tanik, F.A.; Montgomery, A.J. Organizational stressors, work–family interface and the role of gender in the hospital: E xperiences from T urkey. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Date, Y.; Abe, Y.; Aoyagi, K.; Honda, S. Work-related stress, caregiver role, and depressive symptoms among Japanese workers. Saf. Health Work 2014, 5, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuse, T.; Sekine, M. Job dissatisfaction as a contributor to stress-related mental health problems among Japanese civil servants. Ind. Health 2013, 51, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Bartoll, X.; Basart, H.; Borrell, C. Long working hours and health status among employees in Europe: Between-country differences. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2013, 39, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berecki-Gisolf, J.; Tawatsupa, B.; McClure, R.; Seubsman, S.-A.; Sleigh, A. Determinants of workplace injury among Thai Cohort Study participants. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiraoui, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Mannocci, A.; Boccia, A.; La Torre, G. Quality of life among healthcare workers: A multicentre cross-sectional study in Italy. Public Health 2012, 126, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Houtte, E.; Claeys, S.; Wuyts, F.; Van Lierde, K. Voice disorders in teachers: Occupational risk factors and psycho-emotional factors. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2012, 37, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, V.; Rivard, M.; Mechakra-Tahiri, S.D. Gender differences in personal and work-related determinants of return-to-work following long-term disability: A 5-year cohort study. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, S.G.; Saldaña, M.Á.M.; Rodriguez, J.G.; Ritzel, D.O. Influence of task demands on occupational stress: Gender differences. J. Saf. Res. 2012, 43, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirtz, A.; Lombardi, D.A.; Willetts, J.L.; Folkard, S.; Christiani, D.C. Gender differences in the effect of weekly working hours on occupational injury risk in the United States working population. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2012, 38, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Muñoz, J.; Lacasaña, M. Practices in pesticide handling and the use of personal protective equipment in Mexican agricultural workers. J. Agromed. 2011, 16, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.; Jing, R.; Wheeler, K.; Smith, G.A.; Stallones, L.; Xiang, H. Work-related pesticide poisoning among farmers in two villages of Southern China: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, S.; Nayir, I.; Göl, C.; Ediş, S.; Yilmaz, H. Health problems and conditions of the forestry workers in Turkey. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 5884–5890. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, S.; London, L.; Rother, H.-A.; Burdorf, A.; Naidoo, R.; Kromhout, H. Pesticide safety training and practices in women working in small-scale agriculture in South Africa. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Multilevel Course on the Safe Use of Pesticides and on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pesticide Poisoning; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahpour, I. Quality of life and effective factors on it among governmental staff in Boukan city. Stud. Med. Sci. 2011, 22, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, E.; Moghadam, Z.B.; Saraylu, K. Quality of life in pregnant women with sleep disorder. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2013, 7, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Pien, G.W.; Schwab, R.J. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep 2004, 27, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolghanabadi, S.; Mousavi Kordmiri, S.; Mahmodi, A.; Mehdiabadi, S. The effect of mental workload on stress and Quality of Work Life firefighters. J. Sabzevar Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Konopko, M.; Jarosz, W.; Bienkowski, P.; Sienkiewicz-Jarosz, H. Work-related factors and depressive symptoms in firefighters-preliminary data. In MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; p. 00065. [Google Scholar]

- Quach, T.; Nguyen, K.-D.; Doan-Billings, P.-A.; Okahara, L.; Fan, C.; Reynolds, P. A preliminary survey of Vietnamese nail salon workers in Alameda County, California. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, C.M.; Taylor, C.; Soeken, K.; O’Donnell, P.; Farrar, A.; Danis, M.; Grady, C. Everyday ethics: Ethical issues and stress in nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2510–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haahr, A.; Norlyk, A.; Martinsen, B.; Dreyer, P. Nurses experiences of ethical dilemmas: A review. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, B.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Gowda, K.R. Ethical conflicts among the leading medical and healthcare leaders. Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2022, 17, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, A.M.; Sleem, W.F.; Seada, A.M. Effectiveness of ethical issues teaching program on knowledge, ethical behavior and ethical stress among nurses. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).