Abstract

Retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPS) are rare tumours, primarily treated with surgical resection. However, recurrences are frequent. Combining clinical factors with CT-derived radiomic features could enhance treatment stratification and personalization. This study aims to assess whether radiomic features provide additional prognostic value beyond clinicopathological features in patients with high-risk RPS treated with preoperative radiotherapy. This retrospective study included patients aged 18 or older with non-recurrent and non-metastatic RPS treated with preoperative radiotherapy between 2008 and 2016. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression to assess the impact of clinical and radiomic features on time to event outcomes. Predictive accuracy was assessed with c-statistics. Radiomic analysis was performed on the high-risk group (undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, well-differentiated/de-differentiated liposarcoma or grade 2/3 leiomyosarcoma). Seventy-two patients were included, with a median follow-up of 3.7 years, the 5-year overall survival (OS) was 67%. Multivariable analysis showed older age (HR: 1.3 per 5-year increase, p = 0.04), grade 3 (HR: 180.3, p = 0.02), and larger tumours (HR: 4.0 per 10 cm increase, p = 0.02) predicted worse OS. In the higher-risk group, the c-statistic for the clinical model was 0.59 (time to distant metastasis (TDM)) and 0.56 (OS). Among 27 radiomic features, kurtosis improved OS prediction (c-statistic 0.69, p = 0.013), and Neighbourhood Gray-Tone Difference Matrix (NGTDM) busyness improved it to 0.73 (p = 0.036). Kurtosis also improved TDM prediction (c-statistic 0.72, p = 0.023). Radiomic features may complement clinicopathological factors in predicting overall survival and time to distant metastasis in high-risk retroperitoneal sarcoma. These exploratory findings warrant validation in larger, multi-institutional studies.

1. Introduction

Retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPS) are a group of rare tumours that represent approximately 0.2% of all malignancies and 10–15% of all soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) [1,2]. Approximately half of RPS are intermediate or high-grade lesions with the most common histologic subtypes being de-differentiated liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS). For patients with localized disease, surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment with the aim of microscopic negative margins [3]. Unfortunately, recurrences are common and outcomes remain poor with a 5-year OS of approximately 60% [3]. When compared to other STS, RPS have a worse overall outcome compared with matched histologies in the extremity potentially related to the difficulties with its anatomical location and large size at presentation [4]. Improving the outcomes for RPS has remained a significant challenge with a major study reporting no significant benefits from neoadjuvant radiotherapy [5]. However, RPS are heterogeneous leading to variability in potential response to treatments, and, therefore, identifying subgroups who might benefit from radiotherapy or other treatment strategies remains crucial. Furthermore, predicting distant recurrences is crucial, as these patients may benefit more from neo/adjuvant systemic therapy to address micrometastatic disease. Improved methods for predicting recurrence and survival are thus required for optimizing treatment stratification and personalizing care.

While several clinical prognostic factors have been established (e.g., resectability, age, tumour size, grade, high-risk histology (UPS, well-differentiated/de-differentiated liposarcoma or grade 2/3 leiomyosarcoma), multifocality, histologic organ invasion, surgery in a high volume centre), the predictive power of current nomograms remains limited, with reported C-indices ranging from 0.71 to 0.74 [2,6,7]. Since computed tomography (CT) is a cornerstone of RPS diagnosis, the development of models that integrate existing clinical factors with CT-derived radiomic features holds promise for improving prediction accuracy and supporting treatment decision-making [8].

Radiomics involves advanced analysis of quantitative features extracted from conventional imaging, offering potential for diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive applications across diverse tumour types like lung cancer, head and neck cancer, glioblastoma, rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and germ cell tumour [9,10,11,12,13]. These non-invasive imaging tools hold great potential to augment clinical prediction algorithms for enhanced patient prognostication and treatment selection. Radiomics has demonstrated evolving clinical utility across multiple oncologic settings, including tumour staging, early diagnosis, disease differentiation, prognosis prediction, and treatment response assessment [14].

The main radiomic features used for analysis include first-order, the Gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), the Gray Level Dependence Matrix (GLDM), the Gray Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM), the Gray Level Size Zone Matrix (GLSZM), the Neighbourhood Gray-Tone Difference Matrix (NGTDM), and shape features [15]. First-order features, such as mean, median, standard deviation, and kurtosis describe the distribution of pixel intensities within a region of interest. The GLCM quantifies texture by assessing the spatial relationship between pixel intensities, providing metrics like contrast and homogeneity. The GLDM evaluates the dependence of a pixel on its neighbours, capturing granularity in texture. GLRLM measures the length of consecutive pixels with the same intensity, highlighting texture patterns. The GLSZM assesses the size of homogeneous zones, reflecting structural information. The NGTDM evaluates the difference between a pixel and its neighbours, indicating local texture variations. Shape features describe the geometric properties of a tumour, such as volume and surface area [15]. These radiomic features are crucial in radiomic analysis as they provide comprehensive information on tumour heterogeneity, aiding in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response evaluation.

Several studies have explored the use of radiomics in soft-tissue sarcomas [16,17,18]. Notably, the RADSARC-R study reported a validated radiomics model with high accuracy in predicting RPS histology and grade [19]. However, research on the predictive performance of combined radiomic and clinical models for relapse and survival in RPS remains scarce. This study aims to assess whether radiomic features provide additional prognostic value beyond clinicopathological features in patients with high-risk RPS treated with preoperative radiotherapy. This, in turn, could potentially identify high-risk patients who might benefit from the addition of chemotherapy.

2. Methods

This is a single-institutional retrospective study of patients with RPS who were treated with preoperative radiotherapy at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2016. After receiving institutional ethics approval (PMCC 18/168R), patients were identified via institutional health records. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived by institutional ethics review. The study population included patients aged 18 years or above and availability of radiation therapy treatment planning computed tomography (CT) imaging. Patients had to have received neoadjuvant radiotherapy (conformal radiotherapy was given to a dose of 50.4 Gy in 1.8 fractions, daily for 5 days over 6 weeks) and had complete, curative-intent tumour resection performed at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. This radiation dose was the institutional standard at the time of data collection. Patients who had history of any other malignancies diagnosed in the last 5 years or had a recurrent RPS were excluded.

Pre-treatment clinical and pathological data were obtained from the health records. Radiomics features were developed from radiation therapy treatment planning CT images. High-risk disease was defined as UPS, differentiated liposarcoma, or grade 2/3 leiomyosarcoma. Radiomics analysis was performed on images acquired for patients in this high-risk group.

2.1. Segmentation

The gross tumour volume (GTV) as used for RT treatment planning was used as the starting point for all segmentations. The GTV was reviewed by a member of the study team (KT) and refined to exclude non-tumour anatomy such as bone, bowel, and other organs. Where there was ambiguity in the tumour boundary, a senior radiation oncologist (SC) reviewed the segmentation and adjusted as necessary. Images were reviewed at the location of the GTV to determine any artefacts which may impact radiomics feature extraction.

2.2. Radiomics Feature Extraction

CT imaging and segmentations were exported in DICOM format. Images were converted to meta image format, and the GTV segmentation was converted to a binary mask using Plastimatch (v1.8; open-source software; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA). PyRadiomics (v2.1.2; open-source software; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) was used to extract 105 features from the original image; first order statistics, shape, gray level co-occurrence matrix, gray level run length matrix, gray level size zone matrix, neighbouring gray tone difference matrix, and gray level dependence matrix features were extracted. An extraction intensity bin width was set at 10 Hounsfield units, images were resampled to 1 × 1 × 1 mm, and no image intensity normalization was performed [20,21]. Intensity normalization was not applied because the CT images were acquired using a uniform tube potential and largely identical scanner and reconstruction parameters, resulting in a homogeneous dataset where additional normalization was unlikely to alter feature behaviour. Feature extraction was performed on a Dell Precision 5680 workstation.

Since the number of radiomics features was large (105, Supplementary Table S1), a dimensionality reduction step was performed as follows. All pairs of features with an absolute value of Spearman’s rank correlation > 0.8 were identified. Then, iteratively, the following steps were followed to determine inclusion in the final feature set to be used for modelling. All features were marked as ‘yet to be classified’ for inclusion. The feature yet to be classified with the smallest mean absolute correlation with all other features was marked for inclusion in the final feature set. All other features having absolute value of Spearman’s rank correlation > 0.8 with that feature included in the previous step were marked for exclusion from the final feature set. This was repeated iteratively until all features were either classified for inclusion or exclusion. This procedure reduced the dimensionality of the radiomics feature set from 105 features to 27 features. This conservative, correlation-based approach was chosen to minimize multicollinearity and reduce the risk of model overfitting given the modest sample size and limited number of outcome events. Penalized regression techniques such as LASSO were considered but deemed unsuitable, as they typically require substantially larger datasets to produce stable and generalizable feature selection.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics, baseline characteristics, and treatment details were described using descriptive statistics. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to describe the time-to-event curves. Overall survival (OS) was defined by time from surgery until death from any cause. Relapse free survival (RFS) was defined as time from surgery until disease relapse (local or distant) or death. Time to local recurrence (TLR) and time to distant metastasis (TDM) were defined as time from surgery until local relapse or distant disease progression, respectively. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the impact of clinical and radiomic features on time-to-event endpoints. Multivariable analysis of radiomic features was carried out for each radiomic feature adjusting for age at time of surgery and maximum tumour size. Hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals, likelihood ratio p-values, and c-statistics were provided for each model. The assumption of proportional hazards was verified for each of the models. The presence of influential observations was checked for each of the models. Linearity for radiomic features was assessed. No adjustment for multiplicity was performed as the analysis was exploratory in nature. All statistical analyses were performed in R (v4.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

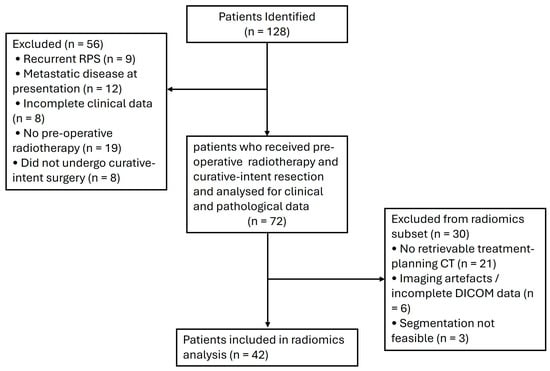

Seventy-two patients met the inclusion criteria for this study, as outlined in the study flow diagram (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort. The median follow-up was 3.7 years, and the median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range, 31–86 years). Most patients were male (61%) and had an ECOG performance status of 0 (58%). WD-DDLPS was the most common histologic subtype (42%), and the median maximum tumour dimension on imaging was 132 mm (range, 23–360 mm). The majority of tumours were grade 2 or 3. Supplementary Table S2 provides a detailed distribution of tumour grades by histologic subtype.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

3.1. Recurrence and Survival Outcomes

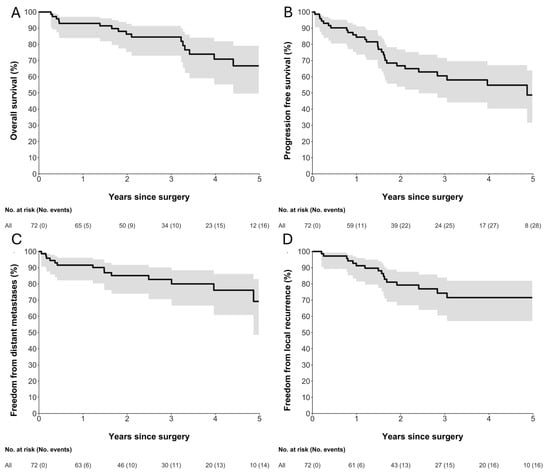

Figure 2 illustrates the OS, RFS, TLR, and TDM for the study cohort. The 5-year landmark estimates were 67% for OS, 49% for RFS, 72% for TLR, and 69% for TDM. Median RFS and OS were 4.9 years (95% CI 2.4—not reached) and 7.4 years (95% CI 4.4—not reached), respectively. These estimates are based on a small number of patients at risk and should therefore be interpreted with caution due to limited precision.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) overall survival, (B) relapse-free survival, (C) freedom from distant metastases, and (D) freedom from local recurrence following surgery. Solid black lines represent Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, and grey shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers at risk and cumulative numbers of events are shown below each plot. Time is measured in years since surgery.

3.2. Clinical Predictors of Survival

Table 2 summarizes the univariable and multivariable analyses of clinical variables associated with survival outcomes. Older age, higher grade, and larger tumour size were associated with worse overall survival. For RFS, older age remained the only variable significantly associated with poorer outcomes (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Cox-proportional hazard model for OS and clinical variables.

3.3. Radiomics

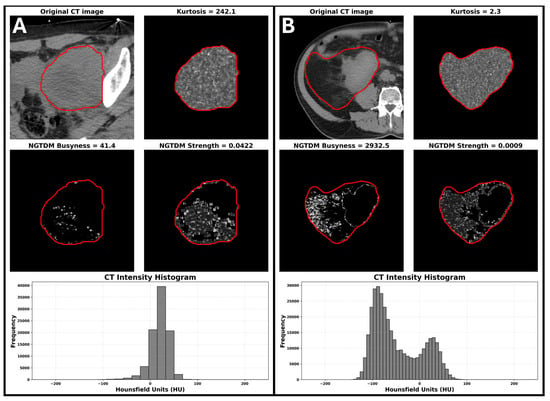

Radiomics analysis was performed on 42 high-risk disease patients for whom imaging was available. Images were acquired on a Philips Brilliance Big Bore (n = 38), or a GE Discovery PET/CT (n = 4), all at 140 kV with 3 mm slice thickness. Given the very limited number of events (15 deaths and 13 distant failures in this subset), only age and maximum dimension were added to the Cox models with radiomic features. The c-statistic for the clinical model (incorporating age and maximum tumour dimension) for OS and TDM was 0.56 and 0.59. Table 3 summarizes the overall survival results for each radiomic features adjusted by tumour size and age (i.e., each line in the table corresponds to a different Cox model). Bold rows indicate radiomic features with an increase in c-statistic > 0.1 compared with the clinical model including age and tumor size alone . For TDM, kurtosis was the only radiomic feature that was predictive (c-statistic 0.72) (Supplementary Table S4). The visual interpretation of variations in radiomic features such as kurtosis and NGTDM are illustrated in Figure 3. In the context of liposarcomas, Figure 3A demonstrates a mass with very uniform density and low fat content resulting in high kurtosis, low NGTDM busyness, and high NGTDM strength, features associated with improved OS. Conversely, Figure 3B shows a mass with a high fat content, as well as a higher density component with low kurtosis, high NGTDM busyness, and low NGTDM strength, associated with poorer OS.

Table 3.

Overall survival by radiomics features adjusted by age and tumour size in the high-risk subset of patients.

Figure 3.

The visual interpretation of variations in radiomic features such as kurtosis and NGTDM. (A) Example of a patient with high kurtosis, low NGTDM busyness, and high NGTDM strength. (B) Example of a patient with low kurtosis, high NGTDM busyness, and low NGTDM strength. Red contours delineate the gross tumor volume used for radiomic feature extraction. The feature scores for the patient on the left were associated with improved OS while the feature scores for the patient on the right were associated with poorer survival.

4. Discussion

This exploratory study evaluated the prognostic potential of radiomic features in addition to clinicopathological features in patients with high-risk RPS treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Age, maximum tumour dimension, and grade were associated with overall survival in the model with clinical variables alone. When incorporating radiomics features in patients with high-risk histology, some radiomic features such as NGTDM busyness and strength showed potential additional prognostic value for OS, worthwhile of further investigation in a larger study.

Our study aligns with prior research that identified grade, age, and tumour size as significant predictors of OS in RPS patients [2,22,23]. While our initial clinical model demonstrated a low c-statistic for predicting both OS (c-statistic 0.56), incorporating radiomic features improved its performance (c-statistics 0.72). Age, grade, and tumour size are well-established prognostic factors for RPS and are integrated into clinical prognostic tools like the Sarculator. This calculator quantifies the risk of recurrence and guides treatment decisions [23,24]. The Sarculator’s C-index for OS and RFS typically ranges from 0.60 to 0.70, indicating moderate predictability [25]. To our knowledge, no existing studies have explored the integration of radiomic features with the Sarculator or other clinicopathological models for RPS. This aspect represents a novel contribution of our investigation.

Prognostic tools such as Sarculator have improved outcome prediction in retroperitoneal and soft-tissue sarcomas but retain only moderate discriminative performance and would benefit from further refinement to support individualized prognostication [26]. Recent studies have proposed incorporating novel biomarkers, including radiomic, genomic, and molecular features to enhance these models. However, emerging evidence indicates that adding candidate biomarkers to Sarculator does not consistently improve prognostic accuracy, underscoring the need to evaluate modalities such as radiomics for genuine incremental value in risk prediction and clinical decision-making [27]. Kurtosis measures the intensity distribution of an image. High kurtosis indicates a distribution with a sharp peak and heavy tails, while low kurtosis suggests a flatter distribution with fewer extreme values. Tumours with higher kurtosis are more heterogeneous and potentially more aggressive [15,28]. The NGTDM filter applied to an image results in a matrix of the differences between the intensity of a voxel and the average of the surrounding voxels within a specified distance. NGTDM busyness measures the rate of intensity change within the image, with higher busyness reflecting rapid changes in intensity values [15,28]. NGTDM strength captures the consistency of gray levels throughout the CT image, where higher NGTDM strength indicates a more homogeneous texture, and lower strength suggests a more heterogeneous and complex texture [15,28]. This was demonstrated in Figure 3 and highlights a crucial aspect of radiomics, through its capacity to quantify features that are imperceptible through visual inspection yet may be critical in predicting clinical outcome.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the integration of radiomic factors into existing clinical models for RPS management [19]. While limited research explores the combined use of radiomic and clinical data to predict RPS relapse and survival, the large, multi-cohort RADSARC-S study evaluated the ability of radiomic features to predict histology and grade in patients with primary leiomyosarcoma or liposarcoma RPS undergoing surgical resection. Although the RADSARC-S study successfully predicted grade and histology with high accuracy, it did not assess the model’s ability to predict recurrence or survival [19]. Several other studies investigating non-RPS have reported a similar improved predictive utility of radiomics for relapse, progression, and survival [11,29,30,31,32,33].

Radiomics has the potential to influence treatment algorithms for patients with localized RPS, enabling treatment de-escalation or escalation based on specific features. Currently, treatment decisions typically rely on clinicopathological findings, which are often limited by small biopsy samples that may not capture tumour heterogeneity. In contrast, CT scans, universally employed in RPS workup, allow for the extraction of radiomic features from the entire tumour, potentially enhancing the accuracy of outcome prediction, as demonstrated in our study. Importantly, while the STRASS study did not yield conclusive results, radiomics could identify RPS patients who might benefit from neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Additionally, kurtosis showed utility in predicting time to distant metastasis, potentially identifying RPS patients who could benefit from neo/adjuvant chemotherapy. However, further validation studies and model development for routine clinical practice are warranted.

Our study’s strength lies in combining clinicopathological and radiomics data to enhance the prediction of OS and time to distant metastasis. Additionally, as a real-world study, our patient population may better reflect everyday clinical practice. However, all patients in our cohort were treated before the results of the STRASS trial, meaning they all received neoadjuvant radiotherapy, which may not represent current practices.

Regarding our study limitations, the retrospective nature of this study may have introduced bias, and the modest sample size with limited follow-up and few outcome events only enabled a highly exploratory analysis of radiomic features. No internal or external validation was performed, and radiomic features were assessed individually rather than in combination due to the limited event count. All images were acquired with the same tube potential, without intravenous contrast, and the vast majority of images were acquired with the same scanner and acquisition/reconstruction protocols. This relative homogeneity may limit generalizability to more variation in imaging acquisition protocols such as those with intravenous contrast. Segmentation was performed by experienced operators, but test–retest or interobserver reproducibility was not formally evaluated. No image harmonization or normalization techniques were applied, consistent with prior exploratory single-centre studies. Some hazard ratio estimates were associated with wide confidence intervals, reflecting the limited number of outcome events and small sample size; these should be interpreted as indicating the direction and relative strength of association rather than precise quantitative effects. Given these limitations, no multiplicity correction was performed, and the findings should be considered hypothesis-generating, warranting further validation in larger, prospective multicentre cohorts.

5. Conclusions

We identified similar clinicopathological factors associated with time to distant recurrence and OS that was in line with the published literature. Some radiomic features may complement clinical predictors to clinicopathological factors to predict OS and time to distant metastasis in patients with high-risk RPS. These findings are hypothesis-generating and warrant further research for validation and development of tools to assist in treatment decision-making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jimaging11120450/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Radiomic features evaluated in the study; Supplementary Table S2: Distribution of histologic subtype and tumour grade within the study cohort; Supplementary Table S3: Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis for relapse-free survival; Supplementary Table S4: Summary of radiomic features associated with time to distant metastasis (TDM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: N.H., J.L., M.B., and A.H. Data curation: N.H., M.B., and A.H. Formal analysis: M.B., A.H., N.H., A.S., and J.L. Funding acquisition: J.L. Investigation: M.B., A.H., N.H., A.S., and J.L. Methodology: A.S., N.H., D.E.G., K.M.I., K.T., C.M., S.C., J.C., M.H., A.H., M.B., J.L. Resources: M.B., A.H., N.H., A.S., and J.L. Software: M.B., A.H., N.H., and J.L. Supervision: J.L. Validation: A.S., N.H., D.E.G., K.M.I., K.T., C.M., S.C., J.C., M.H., A.H., M.B., J.L. Visualization: M.B., N.H., and A.S. Writing—original draft: A.S. Writing—review and editing: A.S., N.H., D.E.G., K.M.I., K.T., C.M., S.C., J.C., M.H., A.H., M.B., J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the 2018 ANZSA Hannahs Chance Sarcoma Research Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Peter McCallum Cancer Centre (PMCC 18/168R, 7 August 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for individual informed consent was waived by the institutional research ethics committee because of the retrospective nature of the study. The study involved analysis of existing clinical, pathological, imaging, and treatment-planning data that had been collected as part of routine clinical care, with no direct patient contact and no impact on patient management. All data were de-identified prior to analysis, and the study posed minimal risk to participants. The waiver of consent was approved by the institutional research ethics committee in accordance with applicable national regulations and institutional policies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| RPS | Retroperitoneal sarcoma |

| STS | Soft-tissue sarcoma |

| UPS | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

| WD-DDLPS | Well-differentiated/De-differentiated liposarcoma |

| LMS | Leiomyosarcoma |

| OS | Overall survival |

| RFS | Relapse-free survival |

| TLR | Time to local recurrence |

| TDM | Time to distant metastasis |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| GTV | Gross tumour volume |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| GLCM | Gray level co-occurrence matrix |

| GLDM | Gray Level Dependence Matrix |

| GLRLM | Gray Level Run Length Matrix |

| GLSZM | Gray Level Size Zone Matrix |

| NGTDM | Neighbourhood Gray-Tone Difference Matrix |

| IDN | Inverse difference normalized |

| IMC1 | Informational measure of correlation 1 |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Performance Status) |

| C-statistic | Concordance statistic |

| QA | Quality assurance |

| STRASS | EORTC-62092: Preoperative Radiotherapy Plus Surgery Versus Surgery Alone for Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma |

| ANZSA | Australian and New Zealand Sarcoma Association |

References

- Yamagata, Y.; Komiyama, M.; Iwata, S. Clinical Characteristics and Management of Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma: A Literature Review. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2024, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronchi, A.; Strauss, D.C.; Miceli, R.; Bonvalot, S.; Swallow, C.J.; Hohenberger, P.; Van Coevorden, F.; Rutkowski, P.; Callegaro, D.; Hayes, A.J.; et al. Variability in Patterns of Recurrence After Resection of Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (RPS): A Report on 1007 Patients From the Multi-Institutional Collaborative RPS Working Group. Ann. Surg. 2016, 263, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhao, J.; Du, X.; Huang, B. Survival Outcomes of Surgery for Retroperitoneal Sarcomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, D.C.; Lewis, J.J.; Leung, D.; Brennan, M.F. Influence of Biologic Factors and Anatomic Site in Completely Resected Liposarcoma. JCO 2000, 18, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvalot, S.; Gronchi, A.; Le Péchoux, C.; Swallow, C.J.; Strauss, D.; Meeus, P.; van Coevorden, F.; Stoldt, S.; Stoeckle, E.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Preoperative Radiotherapy plus Surgery versus Surgery Alone for Patients with Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (EORTC-62092: STRASS): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, D.; Miceli, R.; Mariani, L.; Raut, C.P.; Gronchi, A. Soft Tissue Sarcoma Nomograms and Their Incorporation into Practice. Cancer 2017, 123, 2802–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, D.; Miceli, R.; Bonvalot, S.; Ferguson, P.C.; Strauss, D.C.; van Praag, V.V.M.; Levy, A.; Griffin, A.M.; Hayes, A.J.; Stacchiotti, S.; et al. Development and External Validation of a Dynamic Prognostic Nomogram for Primary Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma Survivors. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 17, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai-Kwon, J.; Siva, S.; Lewin, J. Assessing the Clinical Utility of Computed Tomography-Based Radiomics. Oncologist 2018, 23, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiot, J.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Deprez, L.; Zerka, F.; Danthine, D.; Frix, A.; Lambin, P.; Bottari, F.; Tsoutzidis, N.; Miraglio, B.; et al. A Review in Radiomics: Making Personalized Medicine a Reality via Routine Imaging. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libling, W.A.; Korn, R.; Weiss, G.J. Review of the Use of Radiomics to Assess the Risk of Recurrence in Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, R.; Wang, G.; Jing, D.; Bo, L.; Huang, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; et al. Radiomics for Predicting Response of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 893103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, V.; Cerrone, M.; Lavitrano, M.; Salvatore, M.; Cavaliere, C. A Systematic Review of the Current Status and Quality of Radiomics for Glioma Differential Diagnosis. Cancers 2022, 14, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding-Theobald, E.; Louissaint, J.; Maraj, B.; Cuaresma, E.; Townsend, W.; Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Singal, A.G.; Su, G.L.; Lok, A.S.; Parikh, N.D. Systematic Review: Radiomics for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Ren, S.; Guo, K.; Daniels, M.J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, R. Preoperative Differentiation of Serous Cystic Neoplasms from Mucin-Producing Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms Using a CT-Based Radiomics Nomogram. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapicchio, C.; Gabelloni, M.; Barucci, A.; Cioni, D.; Saba, L.; Neri, E. A Deep Look into Radiomics. Radiol. Med. 2021, 126, 1296–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombé, A.; Fadli, D.; Italiano, A.; Saut, O.; Buy, X.; Kind, M. Systematic Review of Sarcomas Radiomics Studies: Bridging the Gap between Concepts and Clinical Applications? Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 132, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Miao, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, K.; Qin, S.; Chen, H.; Lang, N. CT-Based Quantification of Intratumoral Heterogeneity for Predicting Distant Metastasis in Retroperitoneal Sarcoma. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, R.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Q.; Wang, D. Deep Learning Radiomics-Based Prediction Model of Metachronous Distant Metastasis Following Curative Resection for Retroperitoneal Leiomyosarcoma: A Bicentric Study. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, A.; Orton, M.R.; Emsley, R.; Vit, S.; Kelly-Morland, C.; Strauss, D.; Lunn, J.; Doran, S.; Lmalem, H.; Nzokirantevye, A.; et al. A CT-Based Radiomics Classification Model for the Prediction of Histological Type and Tumour Grade in Retroperitoneal Sarcoma (RADSARC-R): A Retrospective Multicohort Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffino, P.; Raudaschl, P.; Fritscher, K.; Sharp, G.C.; Spadea, M.F. Technical Note: Plastimatch Mabs, an Open Source Tool for Automatic Image Segmentation. Med. Phys. 2016, 43, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronchi, A.; Miceli, R.; Shurell, E.; Eilber, F.C.; Eilber, F.R.; Anaya, D.A.; Kattan, M.W.; Honoré, C.; Lev, D.C.; Colombo, C.; et al. Outcome Prediction in Primary Resected Retroperitoneal Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Histology-Specific Overall Survival and Disease-Free Survival Nomograms Built on Major Sarcoma Center Data Sets. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, S.; Palmerini, E.; Quagliuolo, V.; Martin-Broto, J.; Lopez-Pousa, A.; Grignani, G.; Brunello, A.; Blay, J.-Y.; Tendero, O.; Diaz-Beveridge, R.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in High-Risk Soft Tissue Sarcomas: A Sarculator-Based Risk Stratification Analysis of the ISG-STS 1001 Randomized Trial. Cancer 2022, 128, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARCULATOR. Available online: https://www.sarculator.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Callegaro, D.; Barretta, F.; Raut, C.P.; Johnston, W.; Strauss, D.C.; Honoré, C.; Bonvalot, S.; Fairweather, M.; Rutkowski, P.; van Houdt, W.J.; et al. New Sarculator Prognostic Nomograms for Patients With Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma: Case Volume Does Matter. Ann. Surg. 2024, 279, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, A.; Gronchi, A. Sarculator: How to Improve Further Prognostication of All Sarcomas. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2024, 36, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callegaro, D.; Tinè, G.; Oppong, F.B.; Nzokirantevye, A.; Litière, S.; Percio, S.; Carenzo, A.; De Cecco, L.; Chibon, F.; Brich, S.; et al. CINSARC and Sarculator in Patients with Primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma: A Combined Analysis of Single-Institution Data and the EORTC-STBSG-62092 Trial (STRASS). Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 3239–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanzione, A.; Cuocolo, R.; Ugga, L.; Verde, F.; Romeo, V.; Brunetti, A.; Maurea, S. Oncologic Imaging and Radiomics: A Walkthrough Review of Methodological Challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeken, J.C.; Bernhofer, M.; Spraker, M.B.; Pfeiffer, D.; Devecka, M.; Thamer, A.; Shouman, M.A.; Ott, A.; Nüsslin, F.; Mayr, N.A.; et al. CT-Based Radiomic Features Predict Tumor Grading and Have Prognostic Value in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcomas Treated with Neoadjuvant Radiation Therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 135, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, P.; Cui, J.; Sun, C.; Chen, L.; Hong, N.; Li, Z. Radiomics Analysis Based on CT for the Prediction of Pulmonary Metastases in Ewing Sarcoma. BMC Med. Imaging 2023, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, M.; Honoré, C.; Crombé, A.; Bouhamama, A.; Feydy, A.; Dercle, L.; Haddag, L.; Bouché, P.-A.; Ngo, C.; Le Cesne, A.; et al. Prognostic Factors of the Synovial Sarcoma of the Extremities: Imaging Does Matter. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 33, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Ma, S.-T.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.-H.; Wang, Y.-M.; Li, M. Prediction of the Therapeutic Efficacy of Epirubicin Combined with Ifosfamide in Patients with Lung Metastases from Soft Tissue Sarcoma Based on Contrast-Enhanced CT Radiomics Features. BMC Med. Imaging 2022, 22, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.; Zhi, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Hong, N. Radiomics Models for the Preoperative Prediction of Pelvic and Sacral Tumor Types: A Single-Center Retrospective Study of 795 Cases. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 709659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).