1. Introduction

In December 2019, a new form of human coronavirus known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected, which led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a global pandemic of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019) in 2020 [

1]. Due to the rapid worldwide spread of the disease, the development of diagnostic tools became urgent, with the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test adopted as the gold standard for contamination diagnosis [

2,

3,

4]. The gold standard defined by the WHO also recommends serological and radiological testing, with the screening using computerized tomography (CT) and chest X-rays being useful to reveal patterns complementary to the RT-PCR test [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Additionally, imaging techniques offer the potential to apply artificial intelligence (AI) methods to improve SARS-CoV-2 detection [

3,

6,

7,

8].

Although computed tomography (CT) and chest X-ray are the most commonly used modalities for lung disease screening, their widespread application is limited by challenges such as the requirement for patient mobility and exposure to ionizing radiation [

9]. In contrast, lung ultrasound (LUS) does not present these disadvantages, as it enables real-time imaging at a lower cost than CT and X-ray and is portable, making it a good diagnostic tool for regions with limited healthcare systems [

10]. The low cost of this kind of exam also allows repeated bedside exams to monitor a patient’s condition and also to help doctors make quick decisions, which is not feasible with CT and X-ray [

11]. For these reasons, LUS was also adopted for patient screening during the COVID-19 outbreak, leading to the development of specific protocols to assess disease severity [

12]. However, LUS diagnosis strongly depends on the radiologist’s experience and expertise in interpreting visual artifacts [

13]. Consequently, this modality has become the focus of studies seeking to enhance the diagnostic process through machine learning approaches.

Some of the earliest studies investigating the use of lung ultrasound (LUS) for COVID-19 diagnosis employed handcrafted feature extraction techniques, focusing primarily on visual patterns such as the pleural line and B-lines [

14,

15]. These features were subsequently used to train support vector machine (SVM) classifiers, achieving accuracy rates of up to 94% in the work of Carrer et al. [

14]. Despite their initial success, such approaches are inherently limited by their reliance on manually defined features, which may introduce bias and information loss by neglecting other potentially relevant image characteristics. Moreover, the dependence on a fixed feature set and static model architecture reduces the adaptability of these methods to patterns or domain changes [

16].

Other studies have explored the use of deep learning models that automatically learn image representations directly from data. Almost all of them employed convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are well known for tasks involving images [

3,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], but there are also approaches that relied on alternatives such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [

23,

24,

25,

26]. A hybrid framework based on spatial transformers and decision trees was presented in Custode et al. [

27]. Regarding the CNN approaches, some used pre-trained models, such as the popular VGG16 explored in Baum et al. [

18] and in Born et al. [

19], while others employed custom architectures (which was the case for the Mini-COVIDNet presented by Awashi et al. [

20] or the XCovNet proposed in Madhu et al. [

21]). Although there are similarities regarding the models used, each of these studies introduced important contributions, such as the extensive COVID-19 LUS dataset made available by Born et al. [

19] and the development of efficient models for embedded systems in Awashi et al. [

20].

While these studies reported promising results and contributed to advance deep learning methods for COVID-19 detection, they were constrained by the scarcity of medical data—a challenge particularly evident in the context of LUS, given the limited number of publicly available datasets (which is explained due to the use of ultrasound as a medical urgency procedure during the pandemic to make quick decisions and usually without preserving the images obtained) [

15]. Training deep learning models—which have a massive number of parameters—on datasets with a small number of observations might lead to overfitting, which hinders the use of the model to classify new observation not seen during the training step [

28]. One potential way to mitigate this issue is the use of synthetic data generation, with generative adversarial networks (GANs) showing promising results and receiving growing attention in recent years [

29,

30]. By leveraging adversarial training between two neural networks, GANs are capable of learning rich data representations, thereby alleviating the dependence on large annotated datasets since they can generated synthetic samples based on these data representations that can be used to train the classification models [

31]. In the medical domain, recent studies have investigated GAN-based data generation across a variety of imaging modalities, including MRI, CT, and dermoscopy for skin cancer [

32,

33]. However, there are also applications beyond image synthesis, such as image segmentation, denoising, enhancement, and super-resolution across various examination modalities [

33,

34].

Several studies have investigated applications of GANs to ultrasound imaging. For data augmentation, these models have been used to generate synthetic images for breast ultrasound, transcranial ultrasound, intraoperative liver ultrasound, and functional ultrasound for neuroimaging, among others [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. More recent works have expanded the use of GANs beyond image generation, applying them to a wide range of tasks, including the generation of masks for semantic segmentation of key structures in cardiac ultrasound [

41], lesion segmentation in breast ultrasound scans [

42], domain adaptation across different ultrasound machines and acquisition protocols [

43,

44], and speckle noise reduction in ultrasound images [

45], while many of these approaches rely on adaptations of established GAN architectures, the most commonly adopted state-of-the-art models include Wasserstein GAN (WGAN), Pix2Pix GAN, CycleGAN, Progressive Growing GAN (ProGAN), and Super-Resolution GAN (SRGAN) [

34,

46].

Specifically for COVID-19 applications, several works have employed classical GANs and their variants to address the scarcity of imaging data, particularly for X-ray and CT scans [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. However, only a limited number of studies have reported using GANs to improve COVID-19 diagnosis via ultrasound. In Karar et al. [

54], GAN models were trained to improve the COVID-19 classification, using the discriminator to classify the samples and reporting an accuracy of 99.45%. Liang et al. [

36] presented a method for generating high-resolution LUS images through the use of information regarding texture and regions of interest for diagnosis. Zhang et al. [

55] employed Fuzzy logic as a means to constrain the image generation task, proposing the reference-guided Fuzzy integral GAN (RFI-GAN). Denoising diffusion models were explored in [

56] to augment the LUS data, which were used to train a VGG16-based classifier that reached an accuracy of 91%. Fatima et al. [

57] proposed an approach named supervised autoencoder generative adversarial networks (SA-GAN), which uses a supervised encoder to build a latent space to minimize the problem of mode collapse (where the network learns the representation of only a small portion of the data distribution) and uses it to augment data for the minority classes, reporting an increase of up to 5% in the classification accuracy for score classification models trained with the synthetic data.

It is important to note that the application of GANs to medical imaging tasks still faces several limitations. Previous studies have highlighted challenges such as training instability in specific GAN variants, long training times, mode collapse, and tendency to overfit the training set [

54,

58,

59,

60]. Another concern relates to the evaluation of synthetic data, as commonly used performance measures—such as Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Multiscale Structural Similarity (MS-SSIM)—are highly application-dependent and may fail to capture clinically relevant details present in medical images [

60]. Finally, a critical limitation that is often overlooked is that, while GANs can synthesize new data consistent with the training distribution and even interpolate across underrepresented regions, there is no guarantee that the synthetic samples will adequately reflect the distributional characteristics of an independent/external dataset, which may contain modes absent from the original training data [

61,

62].

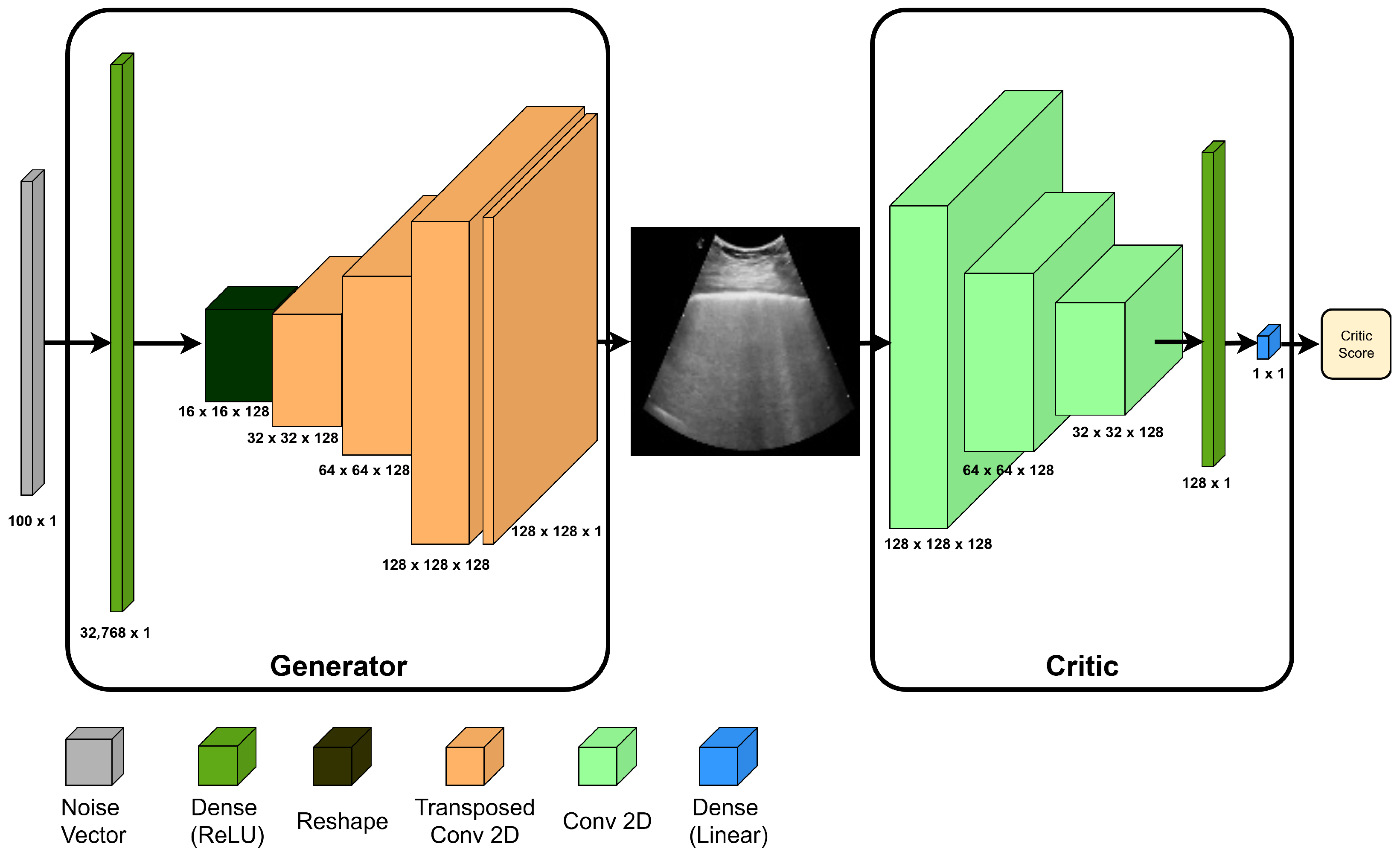

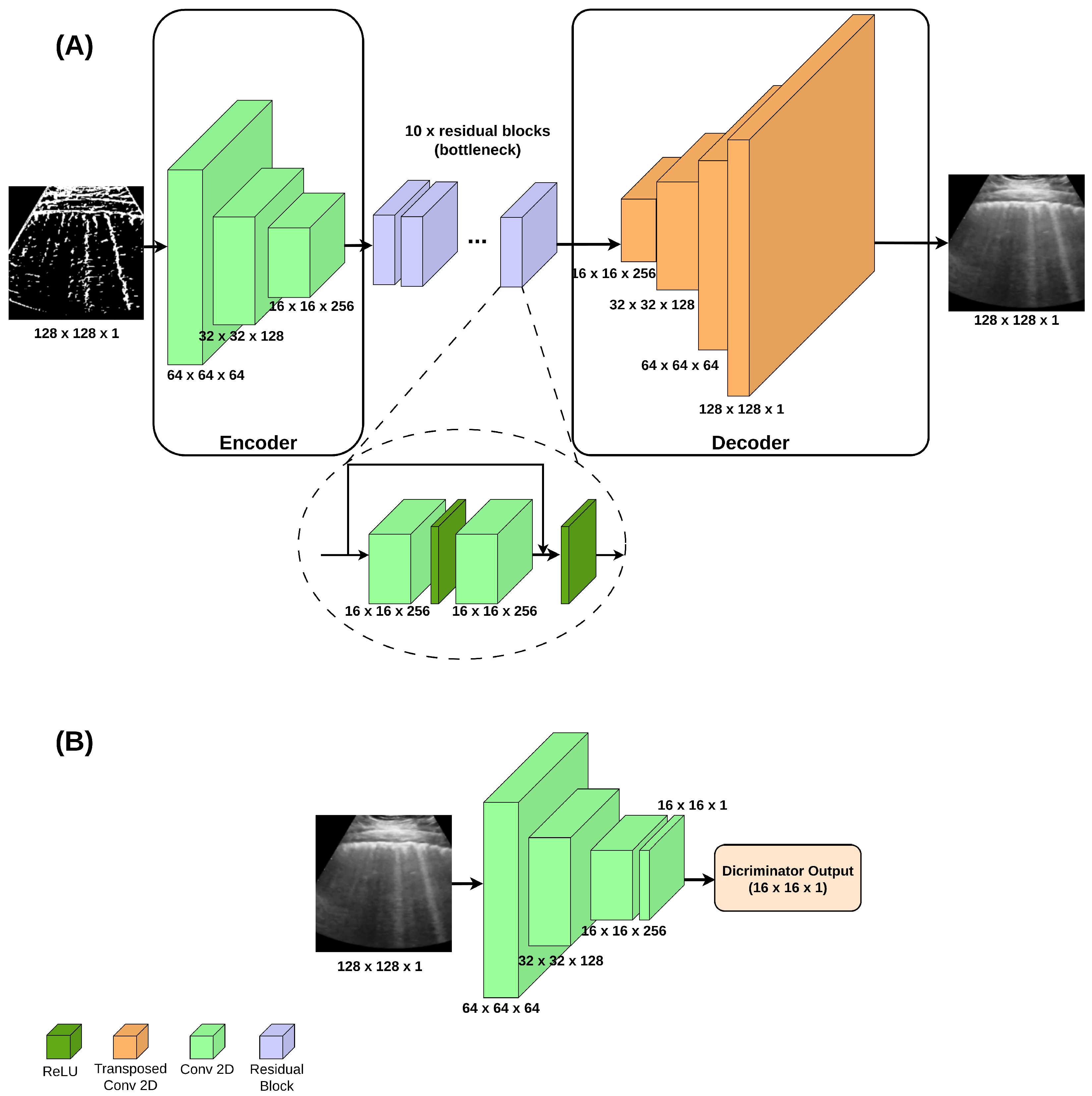

Delving into the challenge of generating LUS images to improve the COVID-19 diagnosis, this study introduces a novel framework that combines multiple GAN-based synthetic data sources to train a single classifier—a strategy not previously explored in this context. The proposed method integrates two complementary GAN approaches: the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN), known for its robustness against mode collapse [

63,

64], and the Pix2Pix GAN, which performs image-to-image translation to produce realistic synthetic data [

65]. By leveraging the strengths of both models, the framework aims to improve the accuracy and generalization of COVID-19 LUS classifiers. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

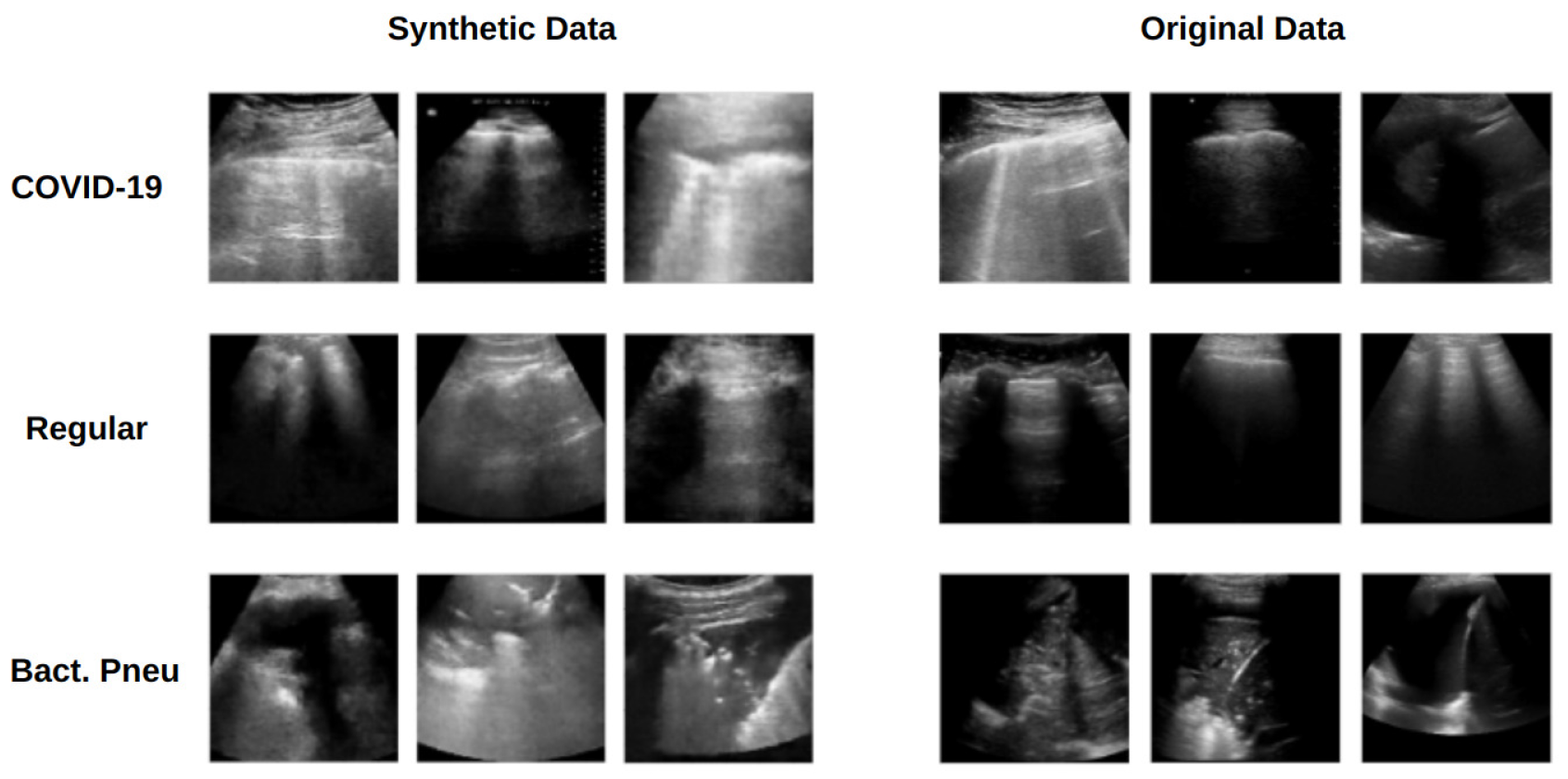

Combining Wasserstein and image-to-image translation GANs to synthesize LUS images.

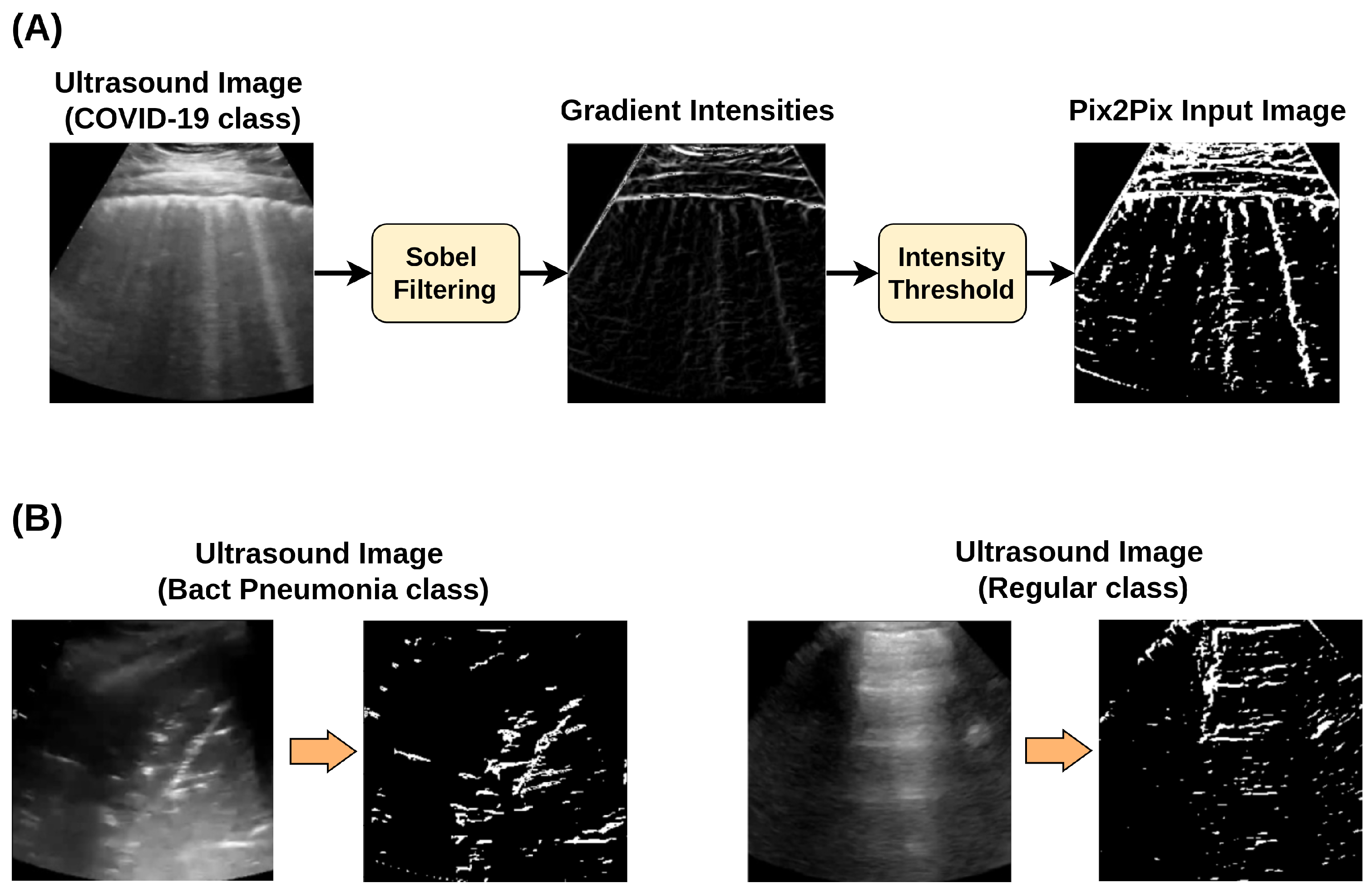

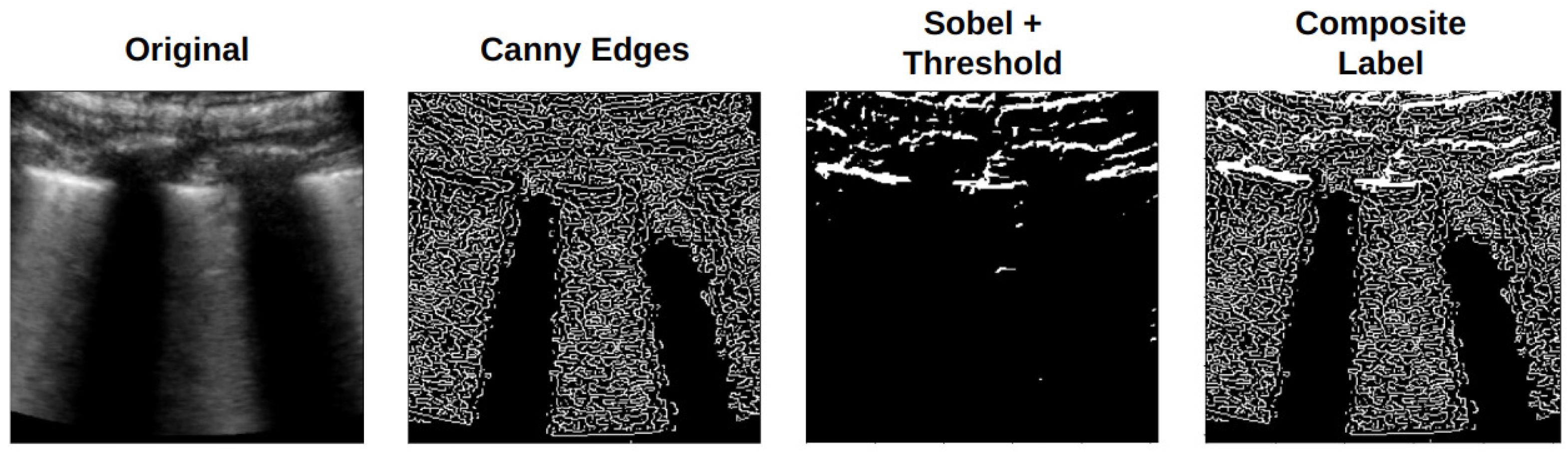

Incorporating a new automated extraction of annotated regions from clinically relevant areas of LUS images for Pix2Pix GAN training.

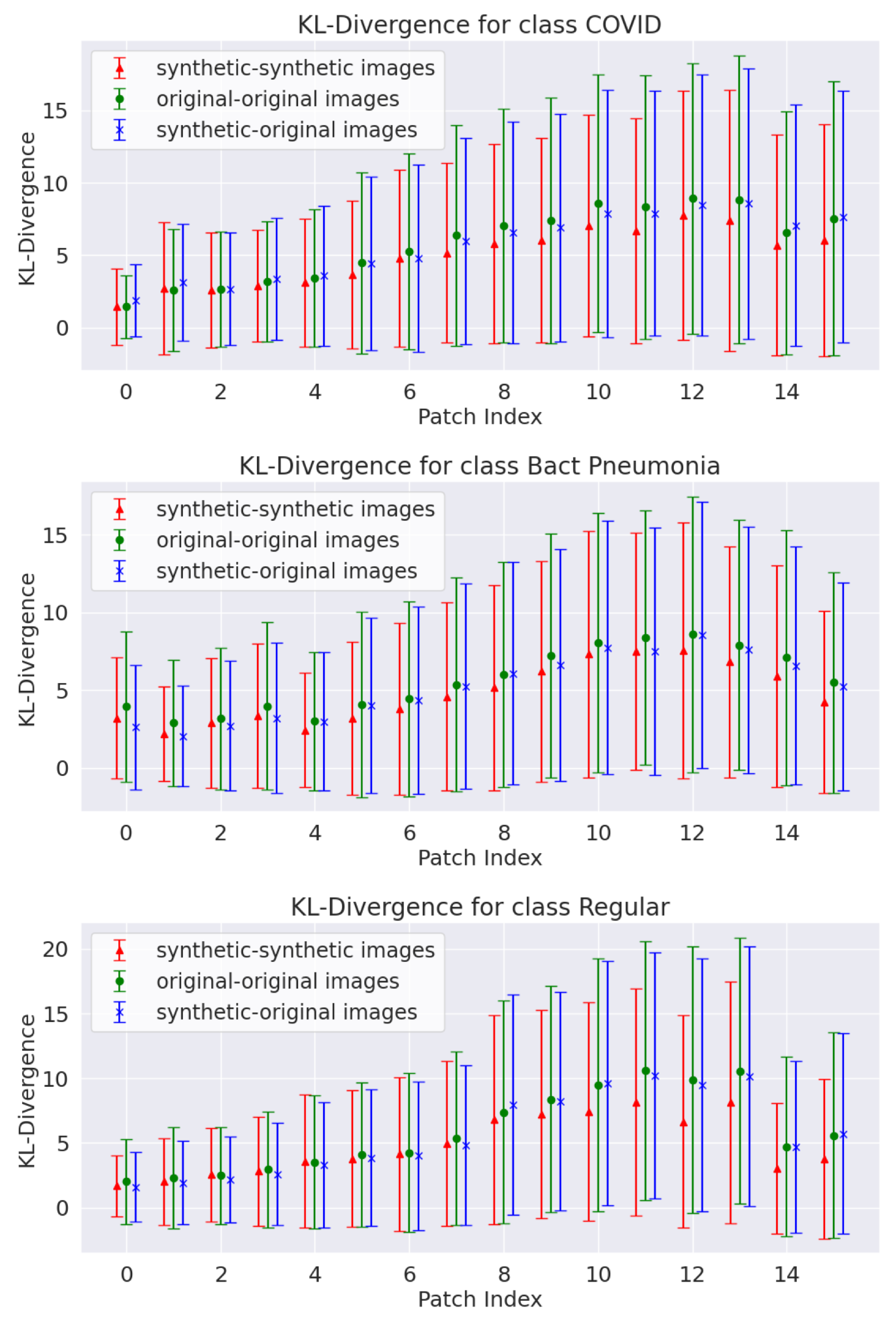

Proposing a method to verify distributional similarity between generated and real LUS images.

Evaluating the impact of synthetic data on classifiers’ performance.

Results show a significant performance improvement when a combination of original and synthetic data is used in the training step of the classifiers, achieving results comparable to or even superior to recent studies.

4. Discussion

Much of the Results Section is devoted to evaluating the generated data, as the best approach for assessing generative models remains an open topic. The present study adopted the KL divergence to assess data diversity in a distribution. The quasi-distance was measured between image patch pairs, and estimates for synthetic data and original–synthetic pairs were found to be similar to those observed in the original data. This suggests that the synthetic data produce fluctuations similar to those from original data within each analyzed region. Furthermore, the L1 and L2 norm analyses confirm the absence of replicas of the training data (as no zero entries were observed in any histogram) and demonstrate that the distributions derived from original data are close to those obtained from synthetic data.

The KID analysis revealed that, although the images generated by the Pix2Pix approaches were generally closer to the original data distribution, the WGAN method demonstrated a notable advantage. Interestingly, the average KID for the WGAN-generated data was lower than the KID estimated in the original dataset. This suggests that the distribution of the WGAN-generated images may be closer to the original data than the distance observed between different subsets of the original data, while this could reflect limitations of the KID metric—such as its reliance on a model pretrained on the broad ImageNet dataset and the required resizing of images to fit the Inception V3 input, which may affect image fidelity—it may also indicate that WGAN-GP is capable of generating samples that fill distributional gaps, particularly those arising from partitioning data across a limited and heterogeneous patient population.

As demonstrated in the Results section, the WGAN and Pix2Pix models provide compelling evidence of their potential to mitigate the scarcity of medical imaging data. The classifier architectures and hyperparameters were kept consistent with those used in [

19,

21], yet a notable performance improvement was achieved when training with a combination of original and synthetic data, as presented in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6. This enhancement can be attributed to the data augmentation effect introduced by the synthetic samples, which increases the number of training observations and thereby reduces the risk of overfitting during model training. Moreover, because WGAN and Pix2Pix models are trained to approximate the underlying probability distribution of the real data, the generated images are not simple transformations of existing samples but instead introduce novel, distribution-consistent variations. This contributes to greater data diversity, thereby enhancing model generalization on unseen test data.

Although

Table 7 shows that some studies may outperform the results of the method presented in this paper, it is important to remember that the cross-validation used was very rigorous, partitioning the data at the patient level and not allowing test data to leak at any point for the training of the models. Unfortunately, that extra care seems not to be taken in related studies, such as Karar et al. [

54], Madhu et al. [

21]. Furthermore, the possibility of generating new data is a powerful tool that can benefit even the models with the highest performance to date.

The comparison with similar studies is limited by the reduced number of studies and the diversity of performance measures adopted [

36,

54,

56,

57]. Thus, a comparison can be made with Karar et al. [

54] and Zhang et al. [

56], which used GANs to generate new data to improve the training of COVID-19 classifiers. As shown in

Table 3, this study’s method yields average results above those of Zhang et al. [

56], although both studies overlap in their error bars. Karar et al. [

54], reported some of the best results for the classification task, but since a k-fold at patient or video-level was not adopted, the values for the performance measures might be optimistic. Even so, the method presented in this paper still reached results close to those of Karar et al. [

54], when considering the error bar.

The WGAN and Pix2Pix approaches yielded similar results, but some significant differences were observed. First, since WGAN generators map random noise onto a LUS image, a large number of observations can be generated. This is not the case with Pix2Pix, as its trained models require an input map to generate an output LUS image. Another difference between these models emerged during training: WGAN models required significantly more epochs to generate realistic LUS images, while Pix2Pix models, after just 2000 epochs, already produced data that enhanced classifier performance. Thus, there is a trade-off between fast training and the number of generated samples.

In particular, for Pix2Pix models, it was surprising that the results for composite label input maps were slightly lower on average compared to the other two preprocessing techniques. When checking for significant differences, the null hypothesis of the median difference between paired observations being equal to zero could be rejected when comparing the composite label results to the other two, meaning the composite label results can be lower than the other Pix2Pix results. This was unexpected, as this approach integrates information from the other two input maps. However, the overlap of input maps could hide information regarding the localization and shape of the artifacts of interest. This is an interesting point that will be addressed in future studies.

The activation maps analysis has shown that, in general, the trained classifier models tend to focus on the center of the input images, which aligns with the position of the pleural line, B-lines, and A-lines. However, as shown in

Figure 16, other regions of the images also generate strong activation. Particularly for the XCovNet trained only with the original data, the activation map shown highlights only regions in the corners of the image, which do not present any meaningful artifacts. However, the same model seems to focus more on regions of the clinical artifacts when trained with the synthetic data.

Training the classifiers with both WGAN and Pix2Pix data resulted in a slight improvement in the average estimates from k-fold cross-validation. This suggests that synthetic data from both sources may complement each other, covering modes that each alone misses. However, further investigation is needed, as the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed no significant difference between the combined approach and the individual use of WGAN or Pix2Pix synthetic images.

There are some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there is still a high cost of computer resources and training time, which were faced when training the GAN models. This limited the image resolution and, particularly for the WGANs, increased the time to train the model by weeks—models were trained on NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPUs. Second, although the quantitative analyses indicate that the distributions of synthetic and real images are comparable, visual inspection reveals that some generated samples lack characteristic medical artifacts, such as well-defined B-lines. This suggests a risk of artifact distortion or omission, reflecting an intrinsic limitation of the employed GAN architectures in accurately replicating subtle diagnostic features. Third, the restricted dataset size imposes constraints on the representativeness of the training data, potentially limiting the model’s ability to capture the full variability of lung ultrasound (LUS) patterns across different populations, acquisition settings, and imaging devices. This limitation may, in turn, affect the generalizability of the trained models to broader clinical contexts. Nonetheless, as noted by Born et al. [

19], the dataset used in this study presents a certain degree of heterogeneity in terms of patient metadata, technical parameters, and disease progression, which partially mitigates the limitations associated with dataset size and homogeneity.

5. Conclusions

Deep learning techniques hold significant potential for enhancing the screening and diagnosis of COVID-19 through lung ultrasound (LUS) analysis. However, their performance remains constrained by the limited availability of publicly accessible medical imaging datasets. To address this challenge, the present study introduced a novel framework that integrates two complementary GAN-based generative models to produce synthetic LUS images, thereby augmenting the training data available for deep learning classification and improving overall model performance. In addition, the study proposed quantitative measures to assess the distributional similarity between original and synthetic images, providing a foundation for evaluating the fidelity and representativeness of the generated data.

WGAN and Pix2Pix models were trained to generate synthetic data. An automated preprocessing pipeline was developed to extract annotated regions corresponding to clinically relevant LUS artifacts, which were subsequently used as input for the Pix2Pix model. The generated images demonstrated a high degree of visual and statistical similarity to the original data, presenting comparable variance and distribution characteristics. When these synthetic images were combined with real data for classifier training, the resulting models achieved significant performance gains over baselines trained exclusively on the original data. Moreover, the proposed approach yielded results comparable to, and in some cases surpassing, the best-performing methods reported in recent literature, underscoring its effectiveness and practical potential in medical image analysis.

Although certain limitations persist regarding the computational cost of training these models and the relatively small dataset size, the proposed approach demonstrates potential to enhance the performance of classifiers developed for this task, while lung ultrasound (LUS) is already a low-cost alternative to CT and X-ray imaging, using synthetic data can further reduce reliance on large volumes of patient data for training classification models. This, in turn, can support the development of computer-aided diagnostic (CAD) systems that may be integrated into portable devices, enabling deployment in regions with limited access to healthcare technologies.

Future work will aim to overcome the current methodological limitations regarding the representation of B-lines in synthetic images. This will involve using manually annotated regions corresponding to these artifacts as auxiliary information during the training of generative models, enabling the exploration of architectures such as the Auxiliary Classifier GAN (ACGAN) and the Conditional GAN (CGAN). Additionally, the authors plan to extend the proposed framework to generate short synthetic LUS videos by incorporating 3D convolutional neural networks (3D CNNs) and experimenting with VideoGAN architectures. This extension is expected to capture the temporal dynamics inherent to LUS examinations, which are critical for comprehensive clinical assessment and diagnostic accuracy.