Abstract

This study explores how 130 future teachers (FTs) perceive and address massive waste generation when it is framed through two socio-environmental contexts: waste export from affluent to vulnerable countries and microplastic pollution in natural environments. Using a mixed-methods design, we examine how each context shapes problem perception, attribution of responsibility, and proposed teaching activities. Both contexts foster a systemic understanding of waste issues. Economic drivers are identified as the main cause (means = 3.2/4), while institutional factors are downplayed in the export scenario and individual factors in the microplastics scenario. Proposed solutions center on institutional and economic measures. Ecological impacts are prioritized in both contexts; however, the export case elicits broader multi-sphere interpretations, whereas microplastics are viewed primarily as ecological–sanitary risks. Perceived responsibility is moderate (mean = 2.6/4) in both contexts, though waste export is interpreted more individually and microplastics more collectively. A disengaged profile predominates, particularly for microplastics (76.92%), with most FTs showing limited intention to change personal habits. In terms of didactic design, only 20% of activities in the export context and 50% in the microplastics context are action-oriented. Findings highlight the importance of carefully selected socio-environmental contexts in teacher education to promote systemic reasoning, shared responsibility, and action-oriented learning.

1. Introduction

One of the most critical threats to achieving sustainability on a global scale is the growing generation waste [1]. The uncontrolled accumulation of municipal solid waste (MSW) in the natural environment is a significant source of environmental pressure, affecting air, soil, surface water, and groundwater quality [2]. It also has implications for public health, landscape balance, territorial equity, and the economy due to the costs of management and remediation [3,4].

In quantitative terms, 2.3 billion tons of MSW were produced worldwide in 2023, with a substantial increase projected to reach 3.8 billion tons per year by 2050 [5]. Despite institutional efforts to optimize MSW recycling or energy recovery processes, significant technical, economic, and regulatory constraints remain [6,7]. Added to these limitations are negative side effects, such as the generation of leachate, the emission of persistent pollutants—such as dioxins and furans—and the increase in greenhouse gases, with direct implications for the current climate crisis [5,8].

In this context, a profound reconceptualization of the production and consumption model that underpins the contemporary economy is essential. Prevention at source and the effective reduction of waste associated with individual consumption decisions are positioned as priority strategies [9,10]. However, numerous studies show that a large part of the population fails to establish clear links between their daily practices and global socio-ecological issues [11]. As a result, it is difficult to recognize excessive waste generation as a manifestation of consumerism and the complex network of economic, social, cultural, and ecological relationships it involves [12].

Given this disconnect, education for sustainability (ES) emerges as a key tool [13,14]. However, various studies warn of significant barriers to effectively addressing these challenges in the field of education. Specifically, the difficulties in developing the critical and systemic thinking that is required are highlighted [15,16]. In general, a reductionist view of these challenges prevails, focusing on the ecological consequences and leaving the socio-economic ones in the background [17]. In addition, these effects are not always immediate or visible in the immediate environment [18]. They are even displaced in other geographical contexts, generally to countries in the Global South [19]. Thus, in addition to the complexity of integrating different areas, there is also the complexity of managing multiple spatial and temporal scales.

All of this prevents citizens from perceiving the problem and its magnitude, limiting their capacity to respond [20]. Furthermore, there is a tendency to externalize responsibility to the productive system or public administration [21]. This overlooks the active role that each individual plays, both individually and collectively, in the demand for and perpetuation of the linear consumption model [18].

Overcoming these barriers requires transformative educational action that promotes the acquisition of competencies in sustainability [22]. Therefore, in addition to understanding the structural causes of this challenge, it is necessary to promote the ability to question current consumption patterns, including one’s own, and decision-making [23,24]. The interest in this lies in the fact that the generation of MSW is very close and tangible. It is an issue that resonates in the lives of students, linked to their daily habits and with accessible and actionable solutions, even from an early age [25]. Hence, the educational potential of the issue of waste for ES.

In this regard, several studies recognize the effectiveness of real-life case studies that integrate different areas and cross-cutting content on the circular economy, responsible consumption, and environmental justice [26,27,28]. In this way, waste ceases to be merely a matter of hygiene or recycling and becomes a gateway to analyzing the limits of the current consumption model. This strengthens the potential of education to contribute to the transition towards more just and sustainable societies [29].

In this context, teachers emerge as strategic agents. Their ability to influence younger generations makes them key vectors for driving this transition [14,30,31]. Numerous studies have revealed that teachers are highly sensitive to socio-ecological issues, including mass waste production [32,33]. However, this sensitivity does not always translate into individual responsibility or an active willingness to adopt sustainable behaviors. Moreover, in some cases, attitudes of indifference or skepticism toward the seriousness of the problem have been identified [34,35,36].

In terms of educational practices, limited teacher training has been identified in content, methodologies, and skills related to ES. Ref. [37] point out that gaps persist in the development of professional skills to address socio-ecological controversies with a critical and reflective approach. This shortcoming directly affects teachers’ confidence levels and the quality of their teaching proposals for integrating the relationship between consumerism, waste, and environmental degradation [38,39]. As a result, there is a lack of practical teaching to engage students in the issue of mass waste generation [26].

Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen initial teacher training in order to build learning environments that promote sustainable behaviors in the classroom [40,41,42]. Teachers must be equipped with conceptual and pedagogical tools that enable them to highlight the connection between consumption practices, global inequality, and ecosystem collapse [13,43].

In this regard, authors such as [44] and [45] point out that it is appropriate to take into account the contexts through which issues are raised when addressing sustainability issues. These contexts can influence the potential to generate commitments to them. However, the influence of these contexts is not fully defined, especially in the context of teacher training. In this regard, ref. [46] question the role played by the different contexts from which future teachers analyze these issues in the teaching proposals they design.

Therefore, this research explores the potential of different contexts to address the challenge of massive waste generation in the training of future teachers (FT) in education for sustainability, considering their dual role as citizens and educators. Then, the research questions of this paper are followings:

- What perceptions do future teachers develop regarding the causes, potential solutions and consequences in each context?

- What commitments, in terms of responsibility and willingness to act, do FT adopt in each context?

- What is the educational approach of the activities proposed by FT in each context?

This comparative analysis may be useful in guiding educators in selecting contexts for initial training.

2. Material and Methods

The research design is mixed-methods descriptive-correlational, with both qualitative and quantitative data analysis. The collection and processing of qualitative and quantitative data occur simultaneously and are subsequently articulated and interpreted together to answer the research questions, so that they support each other, allowing for a deeper and more robust understanding of the results [47]. Combining both methods in social research provides a better understanding of the answers to the research questions [48].

This study is part of a research project by the authors. Therefore, the data collection and data analysis criteria described below are consistent with that project [34,37].

2.1. Participants

The study was conducted over four academic years (from 2019–2020 to 2022–2023) at a Spanish university. A total of 130 participants were selected on a non-probabilistic basis from among future biology teachers who were in the final stage of their Master’s degree in Secondary Education. All participants had received training in science teaching and had completed seven weeks of teaching practice in secondary schools. The groups of participants were equivalent each year, consisting of between 30 and 35 FT, with an average age of 25.6 years.

This study is exploratory in nature and, therefore, open to other analyses that include personal or contextual factors that could influence the FT’s approaches. Furthermore, it should be noted that the sample size makes it difficult to extrapolate the results. Further research is needed to determine whether these results are valid for larger samples.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

A questionnaire was developed based on the work of [34]. This instrument was introduced based on a news item related to each of the contexts involving the massive waste generation. For [49], using real and contextualized situations serves as a trigger for the analysis required by this type of instrument.

Specifically, two contexts were chosen that are close and significant to the FT (see Supplementary Material). This allows for critical reflection on individual consumption within a broader framework that considers the systemic factors involved in the dynamics of waste generation [11]. Promoting, through holistic and pluralistic pedagogical approaches, students’ ability to act, backed by sufficient reflection on the subject to make them responsible for their actions [50]. One of the contexts selected was the export of waste from countries with more developed economies to vulnerable regions. This context allows for the incorporation of a pluralistic–holistic pedagogical approach [49] by integrating multiple perspectives, including social and economic spheres. It provides an opportunity to analyze the interrelationships between different actors and levels, and to link individual actions with the global implications of the problem [50,51].

The second context was the ubiquitous presence of microplastics. This is an emerging problem with increasingly evident environmental and sanitary consequences. Given that it is exacerbated by the widespread use of everyday products (packaging, cosmetics, clothing, etc.), it also allows individual actions to be linked to their cumulative effects at the global level. Furthermore, this context allows us to address not only the complexity of the problem, but also its evolution and persistence [52,53]. This enables a pedagogical approach that is not only holistic but also pluralistic, allowing students to recognize the complexity, value conflicts, and uncertainty associated with the problem [50].

In each of the proposed contexts, three sets of questions were included, designed according to the different dimensions to be explored (Table 1). In this way, it is possible to discuss in a comparative manner the role that context plays in each dimension [44,46]:

Table 1.

Description of the dimensions, features of the questions, and categories of analysis.

Regarding perceptions (P), three questions were included focusing on causes, possible solutions, and consequences. Specifically, the FT assessed the relevance of certain spheres regarding the causes of the problem and the achievement of solutions (P1 and P2). To do this, each sphere was assigned a value from 1 to 4, justifying their decisions. These spheres, in line with [21], are institutional, economic, collective, and individual. The identification of the possible consequences of massive waste generation was carried out through an open question on the subject (P3).

Regarding commitments (C), in line with [54] and [36], two questions were included to assess the degree of responsibility of the FT and their willingness to change their habits: Regarding responsibility (C1), the FT assessed it using a 4-level scale. Furthermore, this assessment was justified. And, regarding willingness to change habits (C2), the FT expressed their willingness or unwillingness to reduce their waste production, justifying their decision.

Regarding their educational approaches (A), the FT designed an activity to be implemented in a secondary school classroom to address the context presented.

2.3. Criteria for Data Analysis

In order to analyze the responses obtained, analysis criteria were established for each of the variables.

Regarding the assessment of causes (P1) and solutions (P2) within the perception of the problem, the analysis focused on determining the relevance given to the different spheres involved with respect to the causes of each context and possible solutions [24,55].

For the consequences (P3), the analysis focused on the impacts associated with each context, differentiating four categories according to their nature: environmental, economic, social, and sanitary [2,35,56,57,58]. As this was an open-ended question, the responses were analyzed using [59] qualitative content analysis. The analysis procedure was carried out in several stages. First, two researchers from the team, experts in science teaching and sustainability, independently carried out an initial categorization of the responses. This resulted in a Cohen’s kappa index of 0.69, which translated into “substantial” agreement [60]. In the second stage, the responses were reviewed and compared until a Cohen’s kappa index of 0.87 was achieved, reflecting an “almost perfect” degree of agreement [60]. In this way, the explanations mentioned by the FT were categorized into these four deductive categories. Table 2 shows the keywords from the responses to this question.

Table 2.

Exemplary coding guideline for analyzing consequences (P3).

For the responsibility assumed by the FT (C1) in each context, their degree of responsibility was analyzed according to their selection of one of the four options given (from not at all responsible to totally responsible, Table 1). As for their justifications, the same four categories were established as for causes and solutions: institutional, economic, collective, and individual [21]. This facilitated the evaluation of the consistency between their perceptions in this regard and who they consider responsible for the problem.

Regarding the willingness of the FT to change habits (C2), two profiles were defined, adapted from [36], according to the justifications they indicate: A disengaged profile: they are less aware of the human origin of socio-ecological problems and have less awareness of the need for change to address them. Therefore, FT find it more difficult to recognize that they contribute to the problem of waste export. As a result, they are less willing to change their habits, or their proposals involve only non-specific changes. On the other hand, a concerned profile: they are aware of the need for change to address socio-ecological problems. Therefore, FT are more willing to change their habits, as they feel they are part of the problem and also part of the solution. Their proposals involve changes that directly affect their consumption patterns at an individual or collective level.

In terms of the types of activities proposed, four educational approaches were identified according to their potential to promote sustainability skills [44,49], as described in [34,37]:

- Approach 1, aimed at conveying information and providing students with data and facts about the problem of MSW. This type of approach is dominated by teacher explanations, video viewing, and pen-and-paper activities [61,62].

- Approach 2, aimed at promoting a certain level of student involvement, giving them a greater role than in the previous approach, although still with a strong dependence on information. This involves activities such as bibliographic search or report writing, which are sometimes combined with practical exercises in which students follow set instructions [63].

- Approach 3, aimed at promoting critical thinking and reflection on real problems associated with socio-ecological conflict situations. These approaches focus on promoting interactive, participatory, experiential, and action-oriented learning. This is the case with proposals based on simulation games or problem-solving [64,65].

- Approach 4, aimed at promoting commitments, in which, in addition to critical thinking and reflection, explicit attention is paid to the analysis and adoption of individual commitments regarding one’s own habits and participation in the community [66].

To ensure reliability in the assignment of analysis categories in the open-ended questions, Cohen’s Kappa was calculated as a measure of agreement between evaluators for categorical data, based on the total independent coding of two researchers. The results show almost perfect agreement for P3 and C1 (κ = 0.87 and κ = 0.85, respectively) and substantial agreement for C2 and A (κ = 0.77 and κ = 0.70, respectively) [60].

2.4. Data Treatment

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to process the data for the three dimensions. On the one hand, the frequency of the established categories was calculated, except for P1 and P2. For these last questions, students ranked the relevance of each category, and the average obtained for each category was calculated. Values close to 4 indicate greater relevance to each category. On the other hand, non-parametric inferential statistics were applied in order to determine possible differences according to the context presented: In perceptions (P), regarding the relevance that the FT gives to the different spheres in the causes and solutions of the problem, and its consequences, using the Mann–Whitney U test and X2. In commitments (C), on the one hand, regarding the level of responsibility assumed by the FT and its interpretation of this responsibility. On the other hand, regarding the willingness to change habits. For this purpose, the Mann–Whitney U test and the X2 test were used. In educational approaches (A), regarding the approach to the activities proposed by the FT, applying the X2 test.

For these inferential statistics, the significance level was set at a value of p < 0.05, using SPSS 28.0 statistical software. The results produced by these statistics can be considered reliable, given that the statistical power was greater than 78% in all of them [67].

This research has been authorized by the Human Ethics Committee of the University where it was conducted (ID 2526/2019), and the processing of the data collected complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of the Problem

With regard to causes (P1), the FT highlight the economic sphere as the most relevant in both contexts, since it is the only sphere with an average score above 3 (Table 3). Within their justifications indicate that companies prioritize economic profitability, in the context of exporting waste to low-income countries. In the other context, they point out that people give preference to the use of plastics because of their low cost.

Table 3.

Average relevance value assigned to each sphere for causes and solutions.

With regard to the least relevant sphere, the export of waste, the least relevant sphere is considered to be the institutional sphere. In general, their justifications indicate that the mass production of waste and its exportation, together with economic interests, is due to excessive personal consumption and a lack of public awareness, rather than administrative decisions, whereas, for the massive presence of microplastics, the individual sphere is pointed out as the least relevant one. In this case, their justifications focus on the collective contribution to the arrival of plastics in the environment and the fact that the public institutions do not apply sufficient control measures.

When analyzing statistical significance, statistically significant differences are observed in the relevance that future teachers assign to the different sphere as causes (X2 = 20.628; gl = 3; p < 0.001). When analyzing what happens in each sphere, we observe that these differences focus on the relevance they attach, on the one hand, to the institutional sphere, which would have a limited role in relation to waste exports. On the other hand, with regard to the individual sphere, which is less relevant to the problem of microplastics, with a more collective perception of their origin (Table 3).

With regard to solutions (P2), the FT seem to give greater importance to solutions that come from the institutional and economic spheres in both contexts (Table 3). Specifically, the arguments focus on the regulation of the productive sector at the institutional level and from the economic sector itself. In relation to the former, the application of sanctions against illegal practices stands out, together with the need to establish international agreements to regulate waste management and trade. Regarding the latter, business investment aimed at improving the technologies used and optimizing waste management processes stands out.

With regard to the less relevant sphere, in the export of waste, less importance is given to the collective sphere, with more attention being paid to reducing individual consumption and waste generation at the domestic level. Meanwhile, when it comes to the problem of microplastics, the individual sphere is again perceived as the least relevant, being the only one with an average value below 2. In this case, FTs identify collective actions aimed at generating social pressure for the implementation of solutions as more significant than individual actions.

These differences in the perception of solutions according to context are statistically significant (X2 = 26.893; gl = 3; p < 0.001). When analyzing what happens in each sphere, it is possible to highlight the institutional and individual spheres (Table 3). Regarding the former, it is the only one that does not show differences statistically significant, highlighting institutions as a relevant sphere to solve the problem in both contexts. On the other hand, regarding individual sphere, for which differences statistically significant do exist, the solution originating in the individual sphere is clearly more undervalued in the context of microplastics.

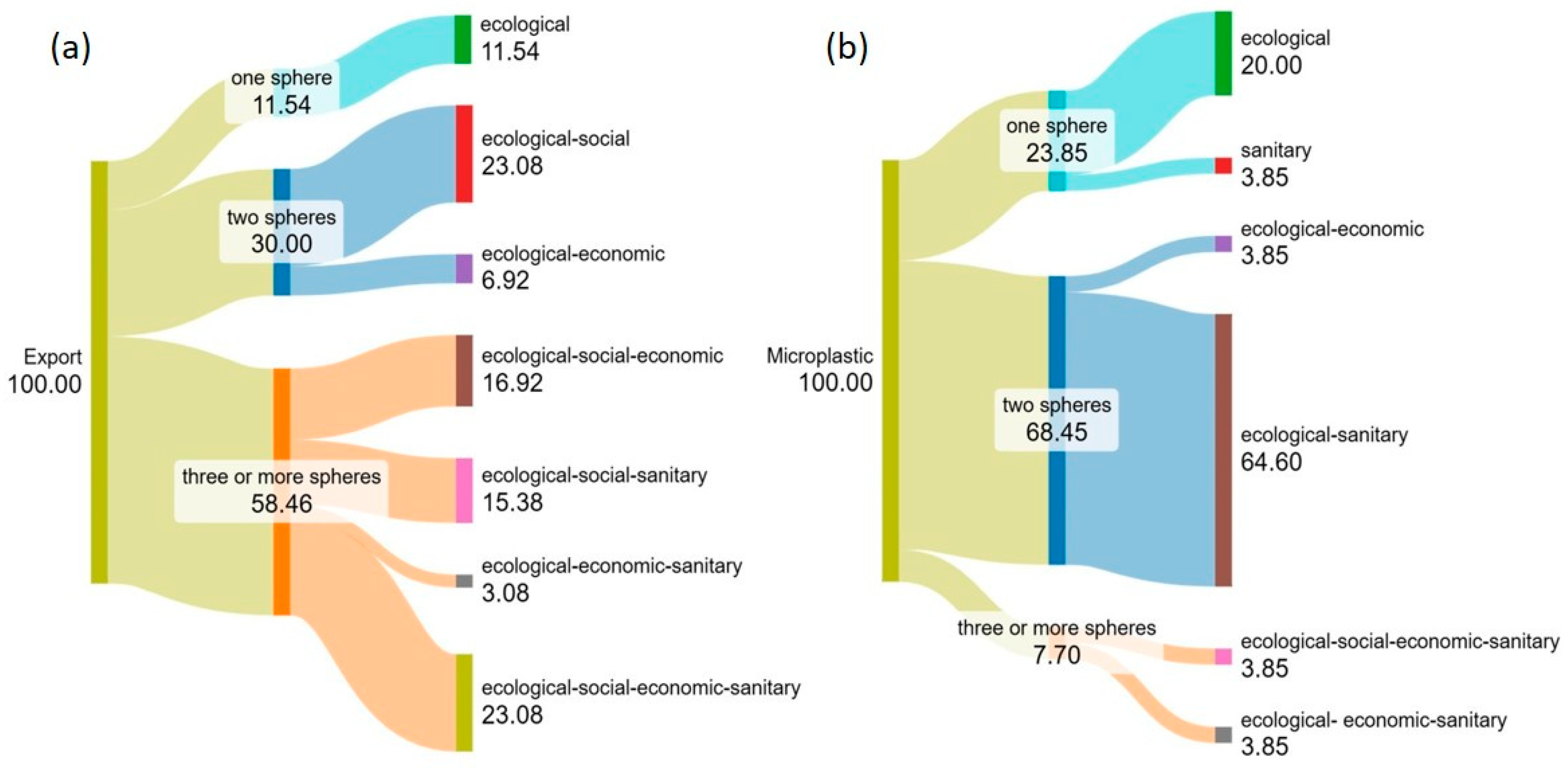

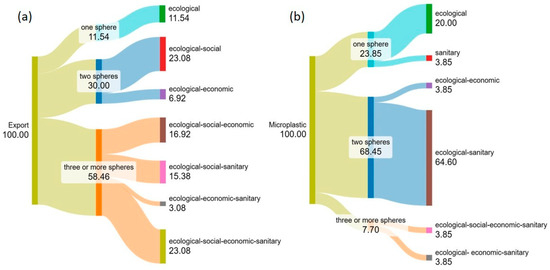

When describing the consequences of massive waste generation, ecological impacts stand out in both contexts. Nevertheless, it is also observed that it is common to incorporate other spheres (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spheres included when assessing the consequences in each context: (a) exportation context, (b) microplastic context (in %).

In this regard, when it comes to waste exports context, future teachers tend to incorporate three or more spheres. Thus, in addition to ecological impacts, they mainly consider social impacts, together with economic and health or sanitary impacts. Their justifications refer to the incidence of illegal landfills on the greater social vulnerability of the countries receiving the waste, pointing out the impacts on the health of people living in these environments and/or the economic benefits for the exporting countries.

In the context of microplastics, most FT have an ecological and sanitary-related view of the problem. The justifications predominantly refer to the damage caused by microplastics to ecosystems, especially marine ecosystems, and the risks to human health posed by their incorporation into the food chain.

The differences observed according to context are statistically significant, both for the spheres involved (X2 = 170.905, gl = 8, p < 0.001) and for the number of spheres involved (Z = −7.238, p < 0.001). Thus, in the context of waste export, FT have a more complex view because, although the ecological-social view stands out, the tendency is to incorporate three or more spheres. Meanwhile, in the context of microplastics, an ecological–sanitary view dominates and rarely incorporates more spheres.

3.2. Commitments

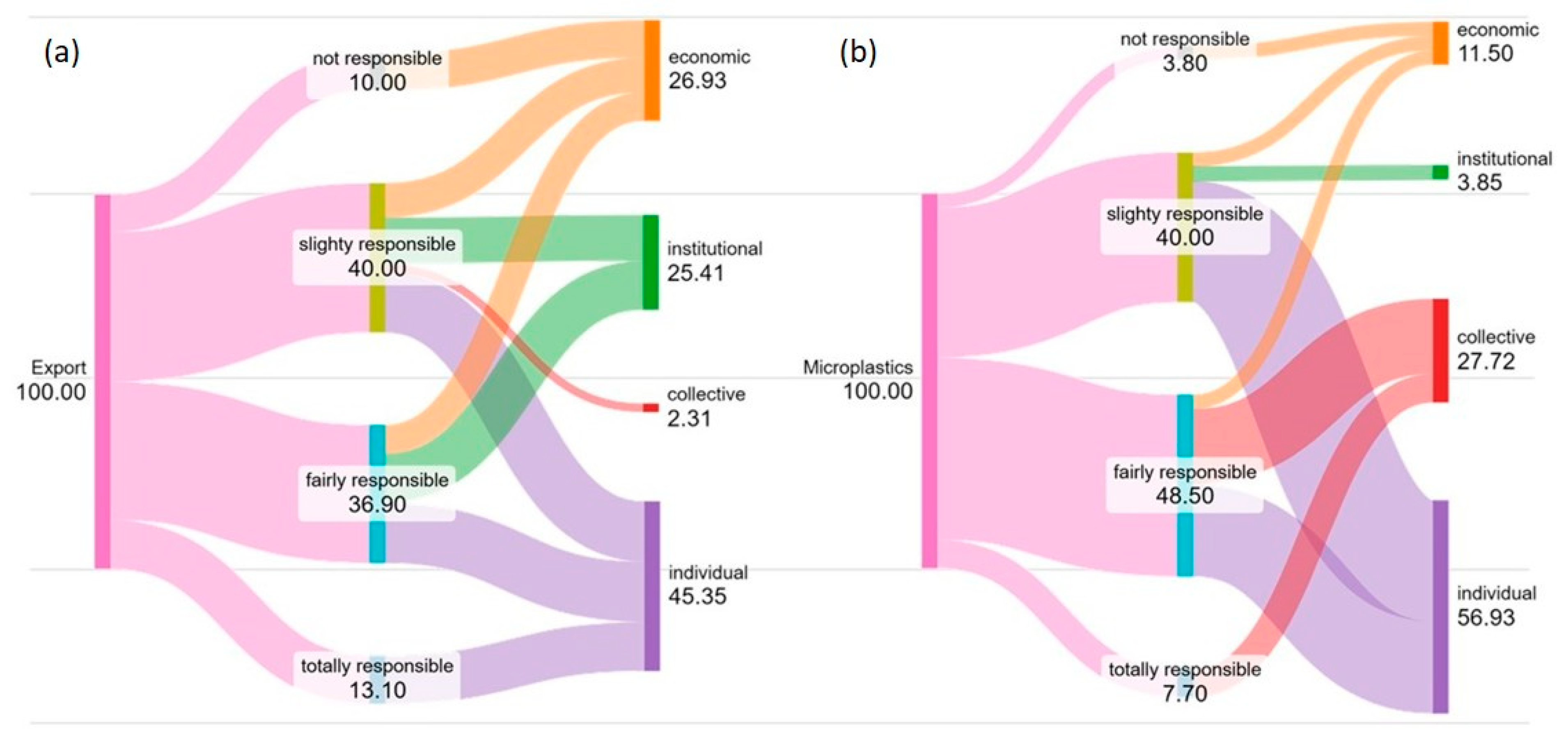

The FT assumes similar responsibility in both contexts, ranking mostly between somewhat and quite responsible, with an average value close to 2.6. Thus, regardless of the context, the FT accept joint responsibility, considering other spheres, mainly economic and institutional, in addition to their individual contribution (Table 4).

Table 4.

Categories of the responsibility assumed by FT and their justification.

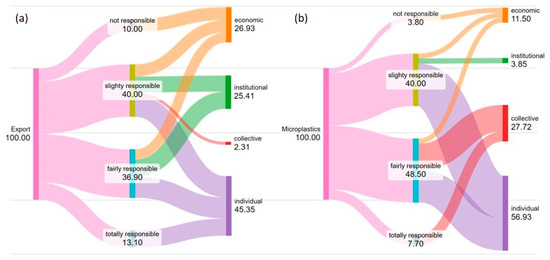

However, from an overall assessment of the responsibility they assume and the spheres they include, different trends can be seen depending on the context (Figure 2). Thus, although when the FT do not feel responsible at all, in both contexts, they only consider the economic sphere, as they assume responsibility, in the context of exports the tendency is for it to be at individual level, while in microplastics it is collective.

Figure 2.

Degree of responsibility assumed and spheres considered in each context: (a) exportation context, (b) microplastic context (in %).

Statistical analysis confirms that there are no differences in the level of responsibility assumed by the FT depending on the context (Z = −0.720, p = 0.471). Nevertheless, there are significant differences in the spheres considered in the justifications in each case (X2 = 92.771, gl = 5, p < 0.001), in response to the trends described above.

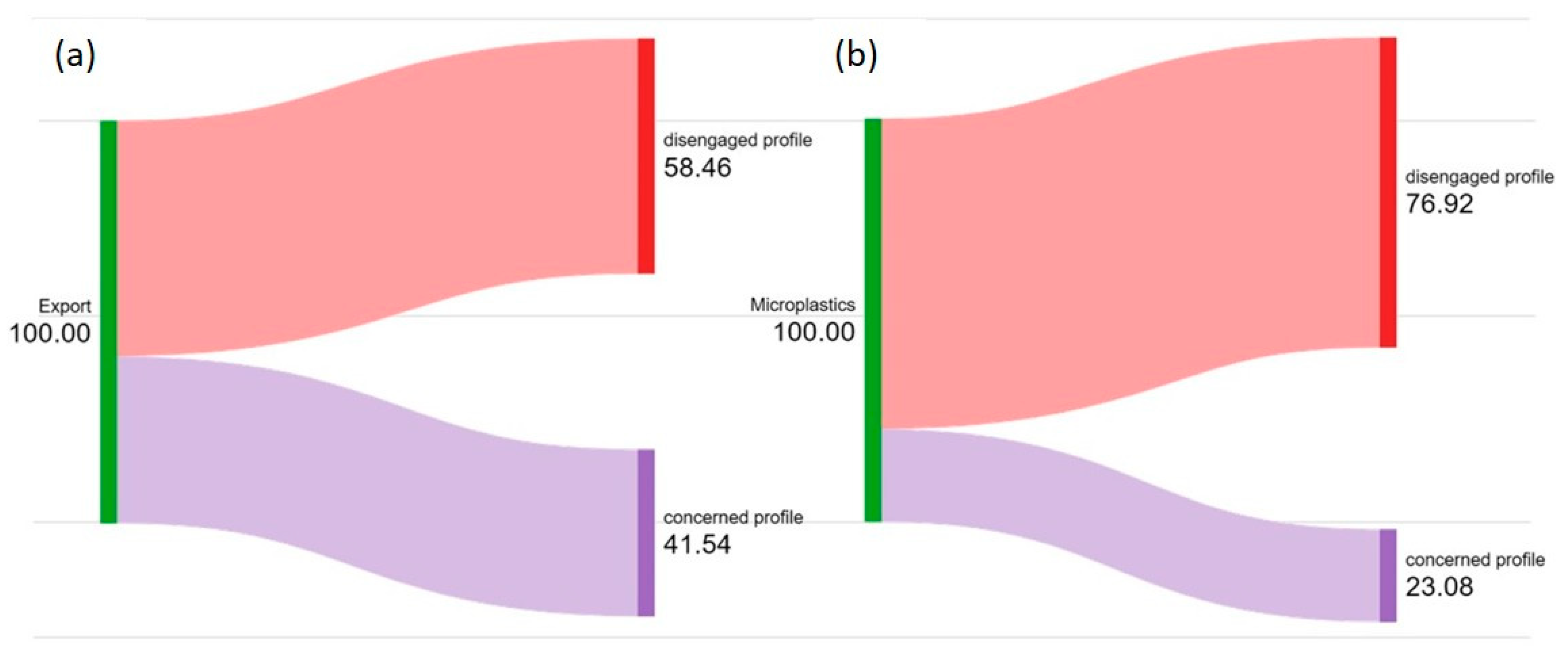

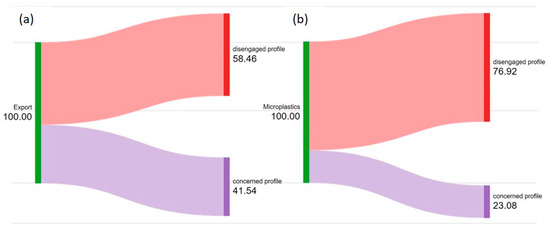

Regarding their willingness to change their habits, we observed a predominance of the disengaged profile in both contexts (Figure 3), although with a lower frequency for waste export. Within this profile, we find different lines of justification depending on the context:

Figure 3.

Frequency of profiles according to willingness to change in each context: (a) exportation context, (b) microplastic context (in %).

- In the context of waste export, the vast majority of FT present the problem as unrelated to its origin or how they contribute to it, individually or collectively, and propose non-specific changes, for example: “The problem exists and we need to change our habits because, if we don’t, it will eventually affect us” (FT 65), or “There are global environmental problems that require urgent action to be mitigated” (FT 20).

- In the context of microplastics, half of the FT follow the same line, with very superficial readings of the problem and indicating non-specific changes, such as “In truth, I should reduce the amount of plastic I consume” (FT 85). However, the other half offer very critical analyses of the complexity of the problem and express skepticism about the effectiveness of individual changes if they are not accompanied by others, involving the economic and institutional sectors: “I would change my attitude if I knew that, in doing so, I would effectively contribute to reducing plastic waste; however, I often reflect on the complexity of the problem, where industry is primarily responsible, and I believe that governments should prioritize the needs of citizens over productive interests” (FT17).

The “concerned” profile is more frequent in the context of waste export, while in the context of microplastics it represents only 1 in 4 FT. Within this profile, there is recognition of the contribution to the problem and specific changes are presented, linked to consumption patterns. Thus, in the export of waste, the “concerned” FT points out: “I am going to buy less clothing. I am a big consumer, and I recognize that this has an impact on both the quality of life of other people and the well-being of the planet” (FT 10). Faced with the problem of microplastics, the concerned FT states: “I generate a lot of plastic waste, and I am going to reduce it by buying in bulk and using large or reusable containers” (FT 101).

There are statistically significant differences in the willingness to change habits depending on the context addressed (X2 = 9.910, gl = 1, p = 0.002). Thus, in the context of waste export, there seems to be a greater willingness to change consumption habits aimed at reducing waste generation. Meanwhile, in the context of microplastics, the vast majority of FT either propose unspecific changes or remain skeptical about the impact of individual consumption changes.

3.3. Proposed Educational Approaches

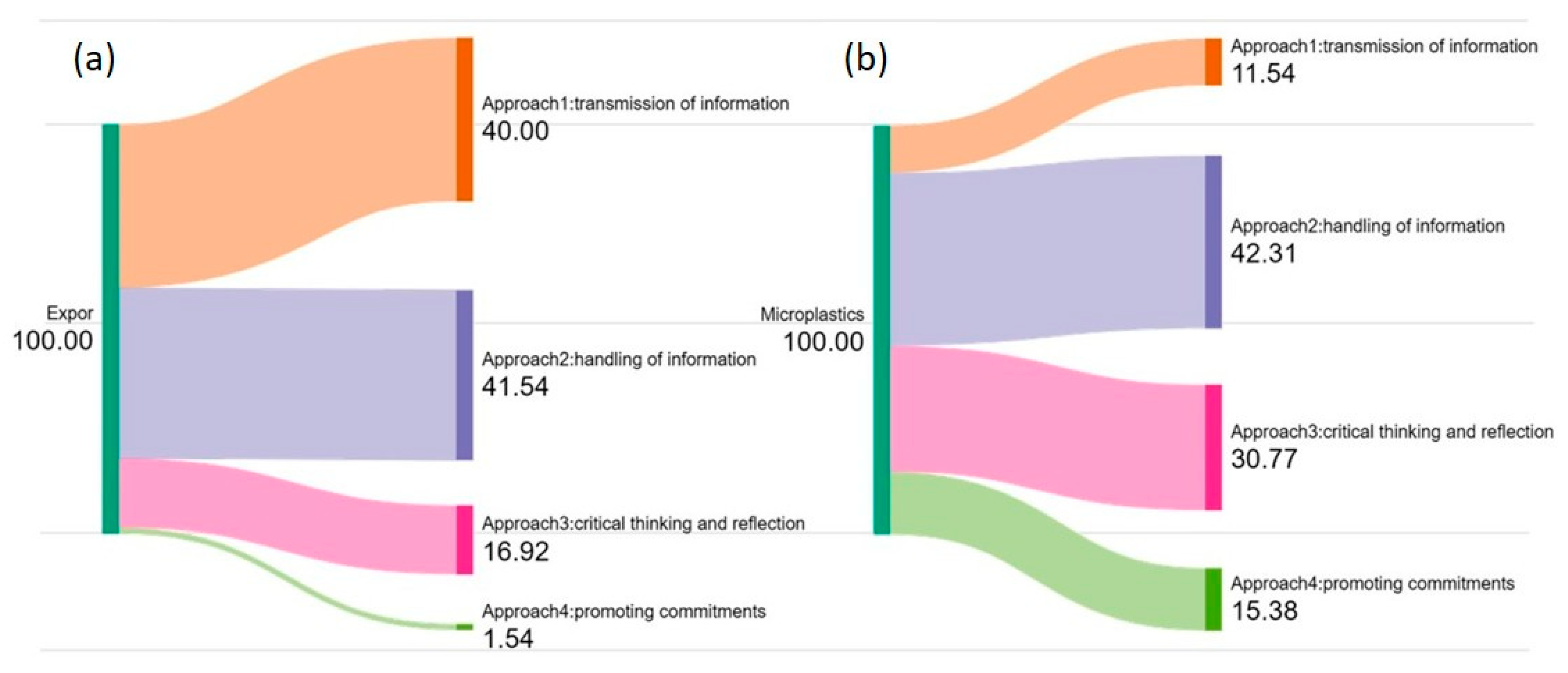

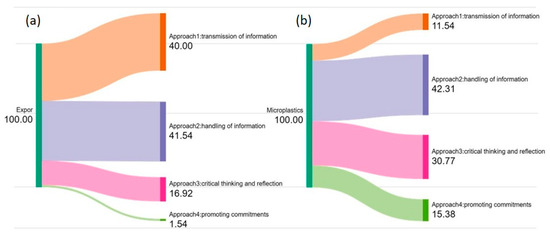

When the FT design educational activities, it favors an approach that promotes a certain level of student involvement, although this is highly dependent on handling information (Approach 2). Specifically, these activities are geared toward consulting data on the web, for example, on the amount of waste generated in the municipality or the presence of microplastics in cosmetic products. Students then use this data to answer questions or write short reports. The frequency of this approach is similar in both contexts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Educational approaches to the activities proposed in each context: (a) exportation context, (b) microplastic context (in %).

With regard to the other approaches, there are differences between the two contexts: In the context of exporting, approach 1 (based on the transmission of information to students) is more frequently observed, especially through explanatory videos. This approach is used with a frequency very similar to approach 2. Meanwhile, less than 1 in 5 activities fall under approaches 3 and 4, which aim to promote student involvement through critical thinking and the adoption of commitments, respectively. Therefore, activities based on the handling of data and facts predominate in this context of waste export.

In the context of microplastics, approach 1 is the least frequent. Thus, there is a similar frequency between the more transmissive approaches (approaches 1 and 2) and those with greater potential to promote sustainable commitments (approaches 3 and 4). Among the activities within the approach 4, which are much more frequent in this context, are those in which students implement actions to reduce the use of plastic in their homes, evaluating their effectiveness. There are also activities in which students participate in community actions, such as collecting waste in the neighborhood, characterizing plastic waste according to the human activities to which it is linked, and carrying out awareness campaigns for the school’s neighborhood.

These differences in the approach to the activities proposed by the FT according to context are statistically significant (X2 = 38.579, gl = 3, p ≤ 0.001). Thus, in the context of microplastics, the activities have greater potential to promote sustainable commitments.

4. Discussion

This article empirically examines the potential of using different contexts during initial teacher education to foster competencies in Education for Sustainability (ES), as those addressed in [49]. Specifically, it focuses on the perceptions, commitments, and educational approaches of future biology teachers regarding the issue of massive waste generation, considered one of the most critical global threats [1].

Regarding perceptions, future teachers closely associate the structural roots of the problem with the productive sector. They identify this domain, along with public administration, as the main contributor to the problem and as one that must play an active role in addressing its solutions. This aligns with earlier studies addressing similar issues [21,68]. Among these future teachers, the prevailing view attributes the problem more to overproduction, which should be regulated, rather than to excessive demand [34].

When various contexts are used, interesting differences appear concerning the relevance of individual versus collective causes and solutions. In the waste exportation context, individual factors, such as household garbage generation, gain importance. Conversely, in the microplastics context, a collective perspective prevails.

Differences between contexts also emerge regarding perceived consequences. Although both contexts recognize the ecological impacts of waste generation, each highlight different associated spheres. In the case of waste exportation context, socioeconomic impacts, particularly the vulnerability of recipient countries, are most salient, often perceived as distant phenomena affecting “other” nations [19,69]. In contrast, in the microplastics context, health or sanitary impacts are more frequently mentioned, with a strong link between food safety and ocean pollution, consistent with [70]. This context therefore offers greater potential for FT to feel individually affected and to perceive the issue as an urgent threat. Ref. [71] notes that perceiving a threat to what is valued heightens personal engagement with socio-ecological issues. The interconnection between ecological and sanitary spheres also contributes to developing a One-health approach [72,73], which, in its educational sense, seeks to raise public awareness of the impact humans have on the planet and, ultimately, affecting collective sustainability [74].

Such a systemic vision contrasts with earlier studies on teachers’ perceptions of sustainability issues [17,36]. Ref. [75] found that when massive waste generation is presented without a specific context, ecological impacts are most frequently recognized, while social impacts remain less identified. The use of specific contexts seems to foster more systemic understandings of the problem, as future teachers more easily incorporate social and sanitary aspects. The importance of this lies in the fact that connecting different spheres brings FT closer to systemic thinking, recognized as a key competence in ES [76].

When exploring the commitments of future teachers, their sense of responsibility shows strong consistency with their perceptions. Most acknowledge co-responsibility for the issue, consistent with prior studies [77]. However, context affects how this responsibility is framed. In the waste exportation context, an increase in perceived responsibility tends to accompany a more individual reading of the issue. In the microplastics context, while individual responsibility remains common, collective sphere gain weight. Several authors have argued that responding effectively to socio-ecological challenges is rarely possible at the individual level alone [24,78]. Nevertheless, personal empowerment is essential to spark broader social transformation [36]. Thus, individual responsibility should not be interpreted in isolation but as part of social responsibility, enabling collective responses [79].

When assessing willingness to reduce waste, most FT propose broad, non-specific changes. Recycling emerges as the dominant recommendation, both for the general public and teachers, as observed by [11] and [35]. This aligns with [80], who found that FT tend to adopt low-effort measures. When referring to waste reduction rather than waste management, they show difficulty in suggesting concrete actions, particularly concerning microplastics. Limited awareness that everyday products such as cosmetics and hygiene items can be sources of microplastics may hinder the design of appropriate solutions [53]. Moreover, classic studies on barriers to sustainable behavior identify overcoming “old behavior patterns” as one of the greatest challenges [81] (p. 257). Thus, addressing massive waste generation—regardless of context—requires strengthening the internal locus of control among future teachers [82], enabling them to recognize the impact of their consumption decisions as a key step toward responsible action [83]. Accordingly, confronting FT with their own consumption patterns will always be more valuable for education for sustainability (ES) than focusing mainly on household waste separation practices [84].

Differences also appear in the educational approaches adopted by future teachers depending on the context. In the waste exportation context, activities are mainly transmissive and informational, representing eight out of ten proposals, a proportion consistent with [36]. Such approaches are limited in effectively engaging students with sustainability [85]. In contrast, in the microplastics context, this dependence is significantly reduced. The number of proposals designed to encourage critical thinking doubles, with nearly half of them fostering critical perspectives and sustainable commitments [44]. These proposals often invite students to critically question plastic use, reduce consumption in daily life, and participate collectively in cleanup actions and civic involvement.

A specific context in which future teachers more easily suggest transformative educational practices becomes a powerful context for their ES preparation. Such contexts help construct learning environments characteristic of this domain [40] and boost the motivation and confidence of future teachers to implement them [38]. Hence, the contexts framing sustainability issues play a decisive role in generating commitments from the initial teacher education [44].

In the case of waste generation, those commitments should not only involve questioning current consumption patterns and making socio-ecological impacts visible, but also adopting practices oriented toward prevention and consumption reduction [9,24]. However, as in previous studies, this research highlights persistent limitations among future teachers when designing educational practices specifically aimed at action [34,38,68,79]. Strengthening the ES training of future teachers thus remains a key strategy for education to decisively contribute to the transition toward more equitable and sustainable societies [29].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of selecting specific contexts when addressing sustainability issues, particularly massive waste generation, during the initial training of future teachers. The comparative analysis between the waste exportation context and the ubiquitous presence of microplastics context reveals some differences. Regarding perceptions of causes and solutions, beyond economic and institutional domains, in both contexts future teachers acknowledge the need to involve the general population, either collectively or individually. Concerning the perceived consequences, both contexts foster a systemic understanding of the issue. In the waste exportation context, there is a tendency to encompass multiple spheres, where nearly 60% of FTs include ecological and socioeconomic impacts. However, these impacts are located in importing countries and thus perceived as distant realities. In contrast, in the microplastics context, consequences are closely linked to human health. In fact, for nearly 65%, there are only ecological and sanitary consequences. Regarding human health, a critical concern for the population, which may lead future teachers to feel more individually affected.

In terms of commitment, different trends are observed as responsibility awareness increases. In the waste exportation context, responsibility is mainly assumed at an individual level. In the microplastics context, while individual engagement remains common, collective spheres gain relevance. In fact, 100% of those who assume full responsibility for exports do so on an individual basis, while 100% of those who consider themselves fully responsible for the release of microplastics do so on the basis of their membership in the community.

Regarding the willingness to change, although the frequency of the concerned profile is almost double when it comes to waste export, in both contexts, future teachers show difficulties in identifying specific actions to reduce waste generation. The educational approaches of the proposed activities also vary according to the context. The microplastics context is associated with greater potential for fostering engagement among their future students. It was found that nearly half of the proposals related to microplastics could achieve this objective, while less than 20% of those related to waste exports could do so. The differences detected indicate that the context used to address sustainability issues significantly influence the potential to generate involvement and commitment from initial teacher training.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/recycling10060224/s1, Table S1: questionnaire for data collection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.-G. and P.E.-G.; methodology, I.B.-G., P.E.-G. and A.R.-N.; analysis, M.Á.G.-F. and M.V.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.-G., M.Á.G.-F. and P.E.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.R.-N., M.Á.G.-F. and M.V.-P.; supervision, I.B.-G. and P.E.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AGENCIA ESTATAL DE INVESTIGACIÓN (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Gobierno de España), grant number PID2019-105705RA-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (protocol code 2526/2019, 15 November 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Perplexity for the purposes of translation into English. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FT | Future teachers |

| ES | Education for sustainability |

| MSW | Municipal solid waste |

References

- Bagheri, M.; Esfilar, R.; Sina, M.; Kennedy, A.C. Towards a circular economy: A comprehensive study of higher heat values and emission potential of various municipal solid wastes. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Resource Efficiency for Sustainable Development: Key Messages for the Group of 20. 2018. Available online: https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/resource-efficiency-sustainable-development (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.C.; Velis, C.A. Waste management—Still a global challenge in the 21st century: An evidence-based call for action. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Waste Management Outlook 2024: Beyond an age of waste—Turning Rubbish Into a Resource. Nairobi. 2024. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/44939 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Bourguignon, D. Circular Economy Package: Four Legislative Proposals on Waste. Briefing EU Legislation in Progress. European Parliamentary Research Service. 2018. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/614766/EPRS_BRI(2018)614766_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Kafle, S.; Karki, B.K.; Sakhakarmy, M.; Adhikari, S. A review of global municipal solid waste management and valorization pathways. Recycling 2025, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; VanWoerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M. Campus sustainability: An integrated model of college students’ recycling behavior on campus. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Ed. 2019, 20, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, A.; Salonen, A.O.; Cantell, H. Climate Change Education: A New Approach for a World of Wicked Problems. In Sustainability, HumanWell-Being, and the Future of Education; Cook, J.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 339–374. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D.; Alkaher, I.; Aram, I. “Looking garbage in the eyes”: From recycling to reducing consumerism- transformative environmental education at a waste treatment facility. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D.; Sahakian, M.; Gumbert, T.; Di Giulio, A.; Maniates, M.; Lorek, S.; Graf, A. Consumption Corridors: Living a Good Life within Sustainable Limits, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brias-Guinart, A.; Markus Högmander, T.A.; Heriniaina, R.; Cabeza, M. A better place for whom? Practitioners’ perspectives on the purpose of environmental education in Finland and Madagascar. J. Environ. Educ. 2023, 54, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Berlin Declaration on Education for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the UNESCO World Conference on Education for Sustainable Development, Berlin, Germany, 17–19 May 2021. German Commission for UNESCO Federal Ministry of Education and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Banos-González, I.; Esteve-Guirao, P.; Ruiz-Navarro, A.; García-Fortes, M.Á.; Valverde-Pérez, M. Exploratory Study on the Competencies in Sustainability of Secondary School Students Facing Conflicts Associated with ‘Fast Fashion’. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Elen, J.; Steegen, A. Fostering students geographic systems thinking by enriching causal diagrams with scale. Results of an intervention study. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2019, 29, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Soysal, N. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Initial Teacher Training Programmes at the UCL Institute of Education; DERC Research Paper No. 22; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Efing, A.C.; Gomes, L. La responsabilidad compartida de los residuos posconsumo en el combate contra la contaminación transfronteriza. Ius Veritas 2014, 24, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cotta, B. What goes around, comes around? Access and allocation problems in Global North–South waste trade. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2020, 20, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.; Brenner, B.; Schmid, E.; Steiner, G.; Vogel, S. Towards meta–competences in higher education for tackling complex real–world problems–a cross disciplinary review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Ed. 2022, 23, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolas, E.; Tampakis, S. Environmental Responsibility: Teachers’ Views. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2010, 12, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 785163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for the Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: París, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, F.; Ruane, B.; Oberman, R.; Morris, S. Geographical Process or Global Injustice? Contrasting Educational Perspectives on Climate Change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 25, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, E.; Murphy, C.; Mancilla, Y.; Mallon, B.; Kater-Wettstaedt, L.; Barth, M.; Ortiz, M.G.; Smith, G.; Kelly, O. International scaling of sustainability continuing professional development for in-service teachers. Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2021, 17, e2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Vidal, D.G.; Dinis, M.A.P. Raising Awareness on Solid Waste Management through Formal Education for Sustainability: A Developing Countries Evidence Review. Recycling 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Solier, P.M.; García-López, A.M.; Prados-Peña, M.B. Teacher Training and Sustainable Development: Study within the Framework of the Transdisciplinary Project RRREMAKER. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N. Ensuring Sustainability: Embedding Environmental Education in Teacher Training. Indian J. Nat. Sci. 2024, 15, 80901–80906. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L. Educación Ambiental y Ecociudadanía: Un proyecto ontogénico y político. Rev. Eletrônica Mestr. Educ. Ambient. 2017, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings Smith, E.; Rushton, E.A.C. Geography teacher educators’ identity, roles and professional learning in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2022, 32, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckert, A.; Bogner, F. Cognitive Learning about Waste Management: How Relevance and Interest Influence Long-Term Knowledge. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezeljak, P.; Scheuch, M.; Torkar, G. Understanding of sustainability and education for sustainable development among pre-service biology teachers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Kalsoom, Q.; Soysal, N.; Ince, B. Student Teachers’ Understanding and Engagement with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in England, Türkiye (Turkey) and Pakistan; Development Education Research Centre, Research Paper No. 23; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- García-Fortes, M.Á.; Esteve, P.; Banos-González, I. Do future teachers’ sustainability commitments really relate to action-oriented educational approaches? Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 31, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Borreguero, G.; Maestre-Jiménez, J.; Mateos-Núñez, M.; Naranjo-Correa, F.L. Analysis of Environmental Awareness, Emotions and Level of Self-Efficacy of Teachers in Training within the Framework of Waste for the Achievement of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Losada, M.; Vega-Marcote, P.; Lorenzo-Rial, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, U. The Challenge of Global Environmental Change: Attitudinal Trends in Teachers-In-Training. Sustainability 2021, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fortes, M.A.; Banos-González, I.; Esteve-Guirao, P. ESD action competencies of future teachers: Self-perception and competence profile analysis. Int. J. Sustain. High. Ed. 2024, 25, 1558–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, T. Prepared to Teach for Sustainable Development? Student Teachers’ Beliefs in Their Ability to Teach for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.; Großschedl, J.; Harms, U. Does motivation matter? The relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and enthusiasm and students’ performance. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Mallon, B.; Smith, G.; Kelly, O.; Pitsia, V.; Martínez Sainz, G. The influence of a teachers’ professional development programme on primary school pupils’ understanding of and attitudes towards sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1011–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, A.; Yousuf Zai, S.A.; Waseem, M.; Khan, S.A. Education for sustainable development (ESD): Effects of sustainability education on pre-service teachers’ attitude towards sustainable development (SD). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, G.; Rojas-Andrade, R.; Caro Zúñiga, C.; Schröder Navarro, E.; Romo-Medina, I. Determinants of the implementation of participatory actions in the environmental education with children and adolescents in Chile. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 30, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, U.; Varela-Losada, M.; Lorenzo-Rial, M.; Vega-Marcote, P. Attitudinal Trends of Teachers-in-training on Transformative Environmental Education. Rev. Psicodidact. 2017, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, E. Advancing educational pedagogy for sustainability: Developing and implementing programs to transform behavior. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2013, 8, 1–34. Available online: http://www.ijese.net/makale/1558.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Rada, E.; Bresciani, C.; Girelli, E.; Ragazzi, M.; Schiavon, M.; Torretta, V. Analysis and measures to improve waste management in schools. Sustainability 2016, 8, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring the Student Teachers’ Views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencias profesionales en Educación para la Sostenibilidad: Un estudio exploratorio de la visión de futuros maestros. Ensen. Cienc. 2014, 32, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Designing powerful learning environments in education for sustainable development: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintrop, D.; Beheshti, E.; Horn, M.; Orton, K.; Jona, K.; Trouille, L.; Wilensky, U. Defining computational thinking for mathematics and science classrooms. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2016, 25, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baierl, T.; Bogner, F.X. Plastic Pollution: Learning Activities from Production to Disposal-FRom Where Do Plastics Come & Where Do They Go? Am. Biol. Teach. 2021, 83, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, P.; Bogner, F.X. Microplastics in the Environment: Raising Awareness in Primary Education. Am. Biol. Teach. 2020, 82, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banos-González, I.; Esteve-Guirao, P.; Jaén, M. Future teachers facing the problem of climate change: Meat consumption, perceived responsibility, and willingness to act. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1618–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Petegem, P.; Blieck, A.; Van Ongevalle, J. Conceptions and Awareness Concerning Environmental Education: A Zimbabwean Case-study in Three Secondary Teacher Education Colleges. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Environment Outlook—GEO-6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People. 2019. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/27539 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Yeheyis, M.; Hewage, K.; Alam, M.S.; Eskicioglu, C.; Sadiq, R. An overview of construction and demolition waste management in Canada: A lifecycle analysis approach to sustainability. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2013, 15, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 20. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0002204 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Flores, J. Rasgos del profesorado asociados al uso de diferentes estrategias metodológicas en las clases de ciencias. Ensen. Cienc. 2017, 35, 175–192. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/Ensenanza/article/view/319574 (accessed on 9 May 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martín Gámez, C.; Prieto Ruz, T.; Jiménez López, M.A. Tendencias del profesorado de ciencias en formación inicial sobre las estrategias metodológicas en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Estudio de un caso en Málaga. Ensen. Cienc. 2015, 33, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalàs, J.; Ferrer-Balas, D.; Mulder, K.F. What Do Engineering Students Learn in Sustainability Courses? The Effect of the Pedagogical Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, L.; Pouliot, C.; Pedretti, E.; Simonneaux, L.; Simonneaux, J.; Zeidler, D. SAQ, SSI and STSE Education: Defending and Extending “Science- in-Context”. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2020, 15, 825–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Van Petegem, P. The interrelations between competences for sustainable development and research competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Ed. 2016, 17, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, E.; Redman, A. Transforming sustainable food and waste behaviors by realigning domains of knowledge in our education system. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurandi-López, A.; González-Vidal, A. (Eds.) Análisis de Datos y Métodos Estadísticos Con R. Editum; Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Soysal, N. Transformative Learning and Pedagogical Approaches in Education for Sustainable Development: Are Initial Teacher Education Programmes in England and Turkey Ready for Creating Agents of Change for Sustainability? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Rishad, H.; Hardisty, D. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviours to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, A.I.; Kramm, J.; Völker, C.; Henry, T.B.; Everaert, G. Risk Posed by Microplastics: Scientific Evidence and Public Perception. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E. How Do Teachers Perceive Environmental Responsibility? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, M.J.; Morrison, K.E.; Parkes, M.W.; Venema, H.D. Promoting health and well-being by managing for social–ecological resilience: The potential of integrating ecohealth and water resources management approaches. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Esquivel-Martín, T. New Insights for teaching the One Health Approach: Transformative Environmental Education for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobusch, U.; Scheuch, M.; Heuckmann, B.; Hodžić, A.; Hobusch, G.M.; Rammel, C.; Pfeffer, A.; Lengauer, V.; Froehlich, D.E. One Health Education Nexus: Enhancing synergy among science-, school-, and teacher education beyond academic silos. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1337748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fortes, M.Á.; Ortega-Lasuen, U.; Esteve-Guirao, P.; Barrutia, O.; Ruiz-Navarro, A.; Zuazagoitia, D.; Valverde-Pérez, M.; Díez, J.R.; Banos-González, I. Are Future Teachers Involved in Contributing to and Promoting the Reduction of MassiveWaste Generation? Sustainability 2024, 16, 7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Empowering Educators for a Sustainable Future. Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development. Geneva. 2013. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/esd/ESD_Publications/Empowering_Educators_for_a_Sustainable_Future_ENG.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Estrada-Vidal, L.I.; Olmos-Gómez, M.D.C.; López-Cordero, R.; Ruiz-Garzón, F. The differences across future teachers regarding attitudes on social responsibility for sustainable development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Van Petegem, P. Teachers’ profiles in education for sustainable development: Interests, instructional beliefs, and instructional practices. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 30, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegalajar-Palomino, M.C.; Burgos-García, A.; Martinez-Valdivia, E. What Does Education for Sustainable Development Offer in Initial Teacher Training? A Systematic Review. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2021, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolppanen, S.; Claudelin, A.; Kang, J. Pre-Service Teachers’ Knowledge and Perceptions of the Impact of Mitigative Climate Actions and Their Willingness to Act. Res. Sci. Educ. 2021, 51, 1629–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Jeng, J.M. Examining the Causal Relationships among Selected Antecedents of Responsible Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Blood, N.; Beery, T. Environmental action and student environmental leaders: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, locus of control, and sense of personal responsibility. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 23, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, A.; Chang, C. Promoting pro-environmental behaviour in a community in Singapore–from raising awareness to behavioural change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 25, 1019–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).