Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Review of Technology, Practice, and Opportunity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Recycling Technology Landscape

3.1. Mechanical Recycling, Textile-Specific, Commercial Scale

3.1.1. Mechanical Fabric Recycling

3.1.2. Mechanical Fiber Recycling

3.1.3. Thermomechanical Polymer Recycling

3.2. Chemical Recycling, Textile-Applicable, Commercial Scale

3.2.1. Hydrolytic Monomer Recycling

3.2.2. Alcoholytic Monomer Recycling

3.2.3. Ammonolytic Monomer Recycling

3.2.4. Cellulosic Polymer Recycling

3.2.5. Pyrolytic Monomer Recycling

3.3. Chemical Recycling, Textile-Applicable, Laboratory Scale

3.3.1. Aminolytic Monomer Recycling

3.3.2. Enzymatic Depolymerization

3.3.3. Ionic Liquid Depolymerization

3.3.4. Metal Complex Catalyst Depolymerization

3.4. Recycling Technology Summary

3.4.1. Mechanical vs. Chemical

3.4.2. Material-Process Compatibility Limitations

3.4.3. Impact Avoidance Limitations

3.4.4. Industrial Capacity Limitations

4. Textile Waste Logistics Landscape

4.1. Collection and Sortation

4.1.1. Collection and Sortation Challenges

4.1.2. Collection and Sortation Technologies

4.1.3. Collection and Sortation Limitations

4.2. Material Separation

4.2.1. Material Separation Challenges

4.2.2. Material Separation Technologies

4.2.3. Material Separation Limitations

5. Circularity Assessment

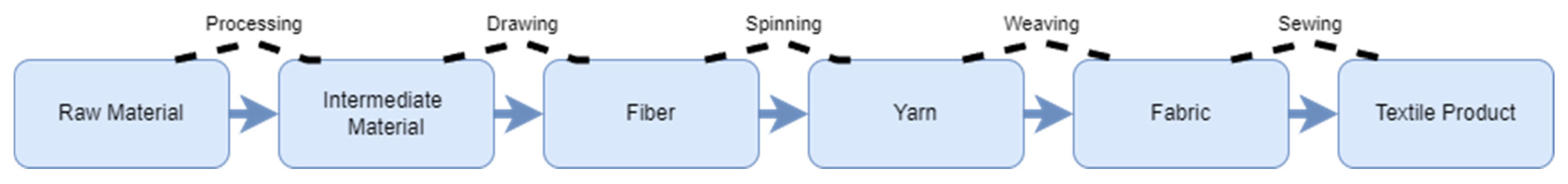

5.1. Manufacturing Value Chain

5.2. Waste Origins and Embodied Value

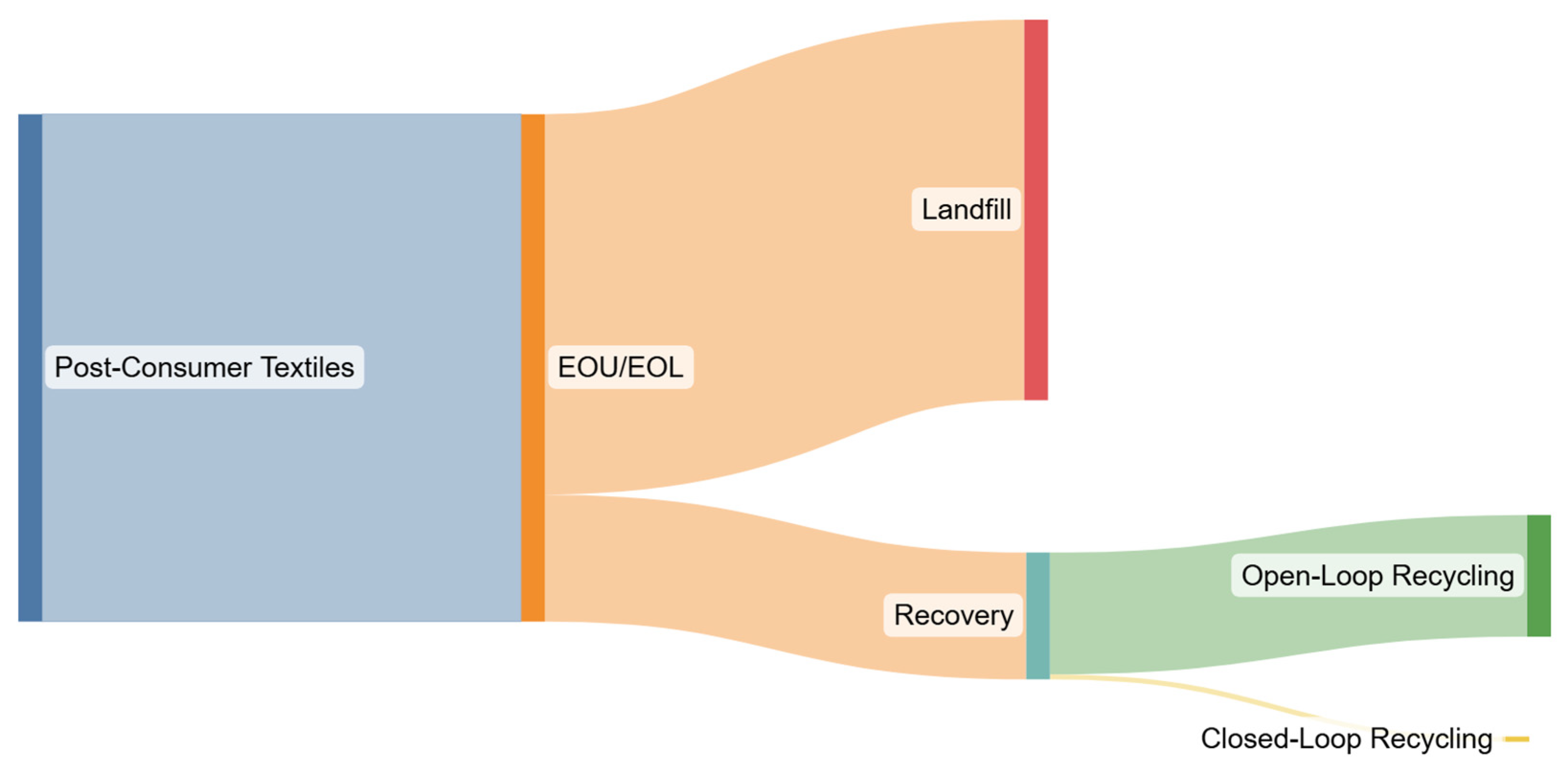

5.3. Open- vs. Closed-Loop Disposition

5.4. Recycling Hierarchy

5.4.1. Closed-Loop Reuse

5.4.2. Fabric Recycling

5.4.3. Fiber Recycling

5.4.4. Polymer Recycling

5.4.5. Monomer Recycling

5.4.6. Energy Recovery

5.5. Generalized Framework

5.6. Scale of Opportunity

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Critical Limitations in Chemical Recycling

6.2. Upstream Potential: Circularity Assessment Framework

6.3. Uptake Challenges and Inevitable Waste

6.4. Recommendations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EOU | End-of-Use |

| EOL | End-of-Life |

| US | United States |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| MMT | Million Metric Tonnes |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| NMMO | N-methyl morpholine N-oxide |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| LCIA | Lifecycle Impact Assessment |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ERM | Enterprise Resource Management |

| DPP | Digital Product Passports |

References

- Textile Exchange. Preferred Fiber & Materials, Market Report; Textile Exchange: Mumbai, India, 2020; Available online: https://textileexchange.org/app/uploads/2021/03/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Claudio, L. Waste couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, A448–A454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Developing a national programme for textiles and clothing recovery. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TTRI Low Carbon Intelligent Operations for Textile Industry in APEC Economies. Taiwan Textile Research Institute. 2013. Available online: https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/Publications/2013/8/Low-Carbon-Intelligent-Operations-for-Textile-Industry-in-APEC-Economies---Project/TOC/Main-Report.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Rana, S.; Pichandi, S.; Karunamoorthy, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Parveen, S.; Fangueiro, R. Carbon footprint of textile and clothing products. In Handbook of Sustainable Apparel Production; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Athalye, A. Carbon footprint in textile processing. Colourage 2012, 59, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- CTR. Council for Textile Recycling. 2018. Available online: http://www.weardonaterecycle.org/ (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Yacout, D.M.; Hassouna, M.S. Identifying potential environmental impacts of waste handling strategies in textile industry. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesa, F.S.; Turra, A.; Baruque-Ramos, J. Synthetic fibers as microplastics in the marine environment: A review from textile perspective with a focus on domestic washings. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzem, S.; Wang, L.; Daver, F.; Crossin, E. Environmental impact of discarded apparel landfilling and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P.; Tehrani-Bagha, A. A review on microplastic emission from textile materials and its reduction techniques. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 199, 109901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.; Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Microfibres from apparel and home textiles: Prospects for including microplastics in environmental sustainability assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, K.; Bajpai, S. Microplastics in Landfills: A Comprehensive Review on Occurrence, Characteristics and Pathways to the Aquatic Environment. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Fiber and textile waste utilization. Waste Biomass Valor. 2010, 1, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.D. Recycled fiber industry facing opportunities and challenges in the new situation. Resour. Recycl. 2012, 11, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- FabScrap. Fabric Recycling. 2025. Available online: https://fabscrap.org/fabric-recycling (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Cotopaxi. Deadstock. Sustainable by Design. 2025. Available online: https://www.cotopaxi.com/pages/sustainable-by-design (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Scott, A. Transforming textiles. CEN Glob. Enterp. 2022, 100, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K. Textile Recycling Technologies, Colouring and Finishing Methods. Report for Metro Vancouver Solid Waste Services, University of British Columbia Sustainability Initiative. 2018. Available online: https://sustain.ubc.ca/about/resources/textile-recycling-technologies-colouring-and-finishing-methods (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Morlet, A.; Opsomer, R.; Herrmann, S.; Balmond, L.; Gillet, C.; Fuchs, L. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Swan, P.; Trebowicz, M.; Ireland, A. Review of wool recycling and reuse. In Natural Fibres: Advances in Science and Technology Towards Industrial Applications: From Science to Market; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 415–428. ISBN 978-94-017-7513-7. [Google Scholar]

- Uyanık, S. A study on the suitability of which yarn number to use for recycle polyester fiber. J. Text. Inst. 2019, 110, 1012–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unifi. Putting Waste to Use. REPREVE®. 2025. Available online: https://unifi.com/sustainability/repreve (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Mahitha, U.; Dhaarini Devi, G.; Akther Sabeena, M.; Shankar, C.; Kirubakaran, V. Fast Biodegradation of Waste Cotton Fibers from Yarn Industry using Microbes. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, C.P.; Koilraj, A.J. Bacterial Diversity in Compost and Vermicompost of Cotton Waste at Courtallam, Nellai District in Tamilnadu, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 582–585. [Google Scholar]

- Aishwariya, S.; Amsamani, S. Evaluating the efficacy of compost evolved from bio-managing cotton textile waste. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2012, 6, 941–952. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.J.; Park, S.J.; Shin, P.G.; Yoo, Y.B.; Jhune, C.S. An improved compost using cotton waste and fermented sawdust for cultivation of oyster mushroom. Mycobiology 2004, 32, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briga-Sá, A.; Nascimento, D.; Teixeira, N.; Pinto, J.; Caldeira, F.; Varum, H.; Paiva, A. Textile waste as an alternative thermal insulation building material solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Wazna, M.; El Fatihi, M.; El Bouari, A.; Cherkaoui, O. Thermo physical characterization of sustainable insulation materials made from textile waste. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 12, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounni, A.; Mabrouk, M.T.; El Wazna, M.; Kheiri, A.; El Alami, M.; El Bouari, A.; Cherkaoui, O. Thermal and economic evaluation of new insulation materials for building envelope based on textile waste. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 149, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, C.A.; Handoko, W.; Pahlevani, F.; Sahajwalla, V. Cascading use of textile waste for the advancement of fibre reinforced composites for building applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, Z.; Behera, B.K. Sustainable hybrid composites reinforced with textile waste for construction and building applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 284, 122800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, P.P.; Martínez-Barrera, G.; Martínez-López, M.; Ureña-Núñez, F.; Ávila-Córdoba, L.I. Waste and Recycled Textiles as Reinforcements of Building Material. In Natural and Artificial Fiber-Reinforced Composites as Renewable Sources; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/56947 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Anjana, E.A.; Shashikala, A.P. Sustainability of construction with textile reinforced concrete—A state of the art. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Materials, Mechanics and Structures, Kerala, India, 14–15 July 2020; IOP Conference Series. Materials Science and Engineering: Kerala, India, 2020. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/936/1/012006/pdf (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Williams, N.; Lundgren, K.; Wallbaum, H.; Malaga, K. Sustainable Potential of Textile-Reinforced Concrete. J. Mater. Civil. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014207. Available online: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001160 (accessed on 16 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Broda, J.; Przybyło, S.; Gawłowski, A.; Grzybowska-Pietras, J.; Sarna, E.; Rom, M.; Laszczak, R. Utilisation of textile wastes for the production of geotextiles designed for erosion protection. J. Text. Inst. 2018, 110, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, M.; Mucsi, G. Open-loop recycling of end-of-life textiles as geopolymer fibre reinforcement. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; García, J.M. Chemical recycling of waste plastics for new materials production. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systemiq. Transforming PET Packaging and Textiles in the United States. 2024. Available online: https://www.systemiq.earth/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Systemiq-Transforming_PET_Packaging_and_Textiles_in_the_United_States_EN.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Shaw, D. THING.; Fleece Fabric: Not Just for Skiing Anymore. The New York Times, 5 February 1995; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, A.; Shukla, S.; Singh, A.; Arora, S. Circular fashion: Properties of fabrics made from mechanically recycled poly-ethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Plastics Recyclers. Postconsumer PET Container Recycling Activity in 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.plasticsmarkets.org/jsfcode/srvyfiles/wd_151/napcor_2017ratereport_final_1.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- USDA2025. Cotton Wool Textile Data—Raw-Fiber Equivalents of, U.S. Textile Trade Data. Economic Research Service. Available online: www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/cotton-wool-and-textile-data/raw-fiber-equivalents-of-us-textile-trade-data (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- BBE Engineering. “VacuFil® Visco[+],” Recycling Technologies. 2023. Available online: https://bbeng.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/BBE_Recycling_Broschuere_Stand-02_2023-web.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Enking, J.; Becker, A.; Schu, G.; Gausmann, M.; Cucurachi, S.; Tukker, A.; Gries, T. Recycling processes of polyester-containing textile waste—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulich, B. Development of products made of reclaimed fibres. In Recycling in Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Jabarin, S.A.; Lofgren, E.A. Thermal stability of polyethylene terephthalate. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1984, 24, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.B.; Madhamshettiwar, S.V. Kinetics and thermodynamic studies of depolymerization of nylon waste by hydrolysis reaction. J. Appl. Chem. 2014, 1, 286709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, A.-J.; Goldhahn, R.; Rihko-Struckmann, L.; Sundmacher, K. Chemical Recycling Processes of Nylon 6 to Caprolactam: Review and Techno-Economic Assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Savage, P.E.; Pester, C.W. Neutral hydrolysis of post-consumer polyethylene terephthalate waste in different phases. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 7203–7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Yu, H.J.; Jegal, J.; Kim, H.S.; Cha, H.G. Depolymerization of PET into terephthalic acid in neutral media catalyzed by the ZSM-5 acidic catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 398, 125655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.Y.; Wan, B.Z.; Cheng, W.H. Kinetics of hydrolytic depolymerization of melt poly (ethylene terephthalate). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, V.; Rodrigue, D. Recycling of Polyamides: Processes and Conditions. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwucha, C.N.; Ehi-Eromosele, C.O.; Ajayi, S.O.; Schaefer, M.; Indris, S.; Ehrenberg, H. Uncatalyzed neutral hydrolysis of waste PET bottles into pure terephthalic acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 6378–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquafil. Econyl Regenerated Nylon, Infinitely Recyclable. 2025. Available online: https://econyl.aquafil.com/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Bureo. “How it Works,” NetPlus®. 2025. Available online: https://bureo.co/how-it-works (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Guo, Z.; Eriksson, M.; de la Motte, H.; Adolfsson, E. Circular recycling of polyester textile waste using a sustainable catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, J.R.; Kamal, M.R.; Cooper, D.G. Kinetics of glycolysis of poly (ethylene terephthalate) melts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 54, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, W.; Du, R.; An, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.Z. Selective depolymerization of PET to monomers from its waste blends and composites at ambient temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korley, L.T.; Epps, T.H., III; Helms, B.A.; Ryan, A.J. Toward polymer upcycling—Adding value and tackling circularity. Science 2021, 373, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijin 2025. ECOPET: Quality from Waste; Teijin Frontier USA, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: www.teijin-frontier-usa.com/ecopet/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- McNeeley, A.; Liu, Y.A. Assessment of PET depolymerization processes for circular economy. 2. Process design options and process modeling evaluation for methanolysis, glycolysis, and hydrolysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 3400–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, D.; Wulandari, L.A.; Bagaskoro, A.; Rianjanu, A.; Wu, H.S. Possibility routes for textile recycling technology. Polymers 2021, 13, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagano, U.N.; Cahill, L.; Smullen, C.; Gaughran, J.; Kelleher, S.M. The Current State-of-the-Art of the Processes Involved in the Chemical Recycling of Textile Waste. Molecules 2025, 30, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Repon, M.R.; Rupanty, N.S.; Asif, T.R.; Tamjid, M.I.; Reukov, V. Chemical valorization of textile waste: Advancing sustainable recycling for a circular economy. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11697–11722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fu, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, J.; Peng, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.; Kang, S. Valorization of polyethylene terephthalate wastes to terephthalamide via catalyst-free ammonolysis. J. Indus. Eng. Chem. 2024, 132, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascend Materials. Circular Polymers by Ascend Launches Cerene™ Certified Post-Consumer Recycled Polymers and Materials. 2023. Available online: www.ascendmaterials.com/news/circular-polymers-by-ascend-launches-cerene-certified-post-consumer-recycled-polymers-and-materials (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Universal Fibers. Universal Fibers Nyon 6,6. 2023. Available online: www.universalfibers.com/news/nylon6.6_for_the_win (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Mihut, C.; Captain, D.K.; Gadala-Maria, F.; Amiridis, M.D. Recycling of nylon from carpet waste. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2001, 41, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Polk, M.; Kumar, S.; Muzzy, J. Recycling of carpet and textile fibers. Plast. Environ. 2003, 1, 697–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bertagni, M.B.; Socolow, R.H.; Martirez, J.M.P.; Carter, E.A.; Greig, C.; Ju, Y.; Lieuwen, T.; Mueller, M.E.; Sundaresan, S.; Wang, R.; et al. Minimizing the impacts of the ammonia economy on the nitrogen cycle and climate. PNAS 2023, 120, e2311728120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interface. Environmental Product Declaration: Modular Carpet. Interface, Inc. Americas: Atlanta, GA, USA. 2021. Available online: https://www.interface.com/US/en-US/sustainability/epds.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- FLOR. “Rug Backings that Give Back,” Our Commitment. 2025. Available online: https://www.flor.com/responsible.html (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Peterson, R.J.L.; Neppel, E.P.; Holmes, D.; Ofoli, R.; Dorgan, J.R. Upcycling of Waste Poly (ethylene terephthalate): Ammonolysis Kinetics of Model Bis (2-hydroxyethyl terephthalate) and Particle Size Effects in Polymeric Substrates. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202500509. [Google Scholar]

- United States Code of Federal Regulations. Title 16, Chapter 1, Subchapter C, Part 303, Subsection 303.7: Generic Names and Definitions for Manufactured Fibers. US Federal Trade Commission. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-16/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-303/section-303.7 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Wheeler, E. The Manufacture of Artificial Silk with Special Reference to the Viscose Process; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1928; Available online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001526382 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Blanc Paul, D. Fake Silk: The Lethal History of Viscose Rayon; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-300-20466-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mcorsley, C. Process for Shaped Cellulose Article Prepared from Solution Containing Cellulose Dissolved in a Tertiary Amine N-oxide Solvent. US Patent 4246221, 20 January 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Duan, C.; Hu, H.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Stavik, J.; Ni, Y. Regenerated cellulose by the Lyocell process, a brief review of the process and properties. BioResources 2018, 13, 4577–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Rayon—The Multi-Faceted Fiber. Ohio State University Extension. Document No. HYG-5538-02. 2002. Available online: http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/5000/pdf/5538.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Nijhuis, M. Bamboo Boom: Is This Material for You? Sci. Am. 2009, 19, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krässig, H.; Schurz, J.; Steadman Robert, G.; Schliefer, K.; Albrecht, W.; Mohring, M. Schlosser Harald 2002 “Cellulose” Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2002; ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Södra. OnceMore®. 2020. Available online: https://www.sodra.com/en/global/pulp/oncemore/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Lenzing. REFIBRA™ Technology—Lenzing’s Initiative to Drive Circular Economy in the Textile World. 2017. Available online: www.lenzing.com/newsroom/news-events/refibratm-technology-lenzings-initiative-to-drive-circular-economy-in-the-textile-world/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Evrnu. Nucycl®. 2025. Available online: https://www.evrnu.com/nucycl (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Circ®. Circ® and Zalando Launch First Collection Featuring Circ Lyocell. 2025. Available online: https://circ.earth/circ-and-zalando-launch-first-collection-featuring-circ-lyocell/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- TextileWorld. Altor Acquires Remaining Assets of Renewcell, Ushering in a New Era as Circulose; Textile Industries Media Group, LLC: Marietta, GA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.textileworld.com/textile-world/fiber-world/2024/06/altor-acquires-remaining-assets-of-renewcell-ushering-in-a-new-era-as-circulose/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Renewcell. Circulose and Tangshan Sanyou Chemical Fiber Forge Strategic Partnership to Drive Large-Scale Textile Circularity. 2025. Available online: www.renewcell.com/en/circulose-and-tangshan-sanyou-chemical-fiber-forge-strategic-partnership-to-drive-large-scale-textile-circularity/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Czajczyńska, D.; Anguilano, L.; Ghazal, H.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Reynolds, A.J.; Spencer, N.; Jouhara, H. Potential of pyrolysis processes in the waste management sector. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2017, 3, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; He, P. Pyrolysis technologies for municipal solid waste: A review. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2466–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.T. Pyrolysis of waste tyres: A review. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1714–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.S.; Oasmaa, A.; Pihkola, H.; Deviatkin, I.; Tenhunen, A.; Mannila, J.; Minkkinen, H.; Pohjakallio, M.; Laine-Ylijoki, J. Pyrolysis of plastic waste: Opportunities and challenges. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2020, 152, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharuddin, S.D.A.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Aroua, M.K. A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 115, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Striūgas, N.; Tatariants, M.; Abdelnaby, M.A.; Tuckute, S.; Kliucininkas, L. A sustainable bioenergy conversion strategy for textile waste with self-catalysts using mini-pyrolysis plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 196, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tujjohra, F.; Hoque, E.; Kader, M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Sustainable valorization of textile industry cotton waste through pyrolysis for biochar production. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockhorn, H.; Hornung, A.; Hornung, U. Mechanisms and kinetics of thermal decomposition of plastics from isothermal and dynamic measurements. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1999, 50, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E.S.; Sadrameli, S.M. Analytical representations of experimental polyethylene pyrolysis yields. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 72, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhout, R.W.J.; Waanders, J.; Kuipers, J.A.M.; van Swaaij, W.P.M. Kinetics of the low-temperature pyrolysis of polyethene, polypropene, and polystyrene modeling, experimental determination, and comparison with literature models and data. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L. Selling a Mirage. ProPublica. 2024. Available online: www.propublica.org/article/delusion-advanced-chemical-plastic-recycling-pyrolysis (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Encinar, J.M.; González, J.F. Pyrolysis of synthetic polymers and plastic wastes. Kinetic study. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Sosa_Blanco, C.; Bustos-Martinez, D.; Vasile, C. Pyrolysis of textile wastes: I. Kinetics and yields. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2007, 80, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona, L.; Barrós, I.; Montero, Á.; Solís, R.R.; Pérez, A.; Martín-Lara, M.Á.; Blázquez, G.; Calero, M. Pyrolysis of textile waste: A sustainable approach to waste management and resource recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcik-Canbolat, C.; Ozbey, B.; Dizge, N.; Keskinler, B. Pyrolysis of commingled waste textile fibers in a batch reactor: Analysis of the pyrolysis gases and solid product. Int. J. Green Energy 2017, 14, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchik, S.V.; Weil, E.D.; Lewin, M. Thermal decomposition of aliphatic nylons. Polym. Int. 1999, 48, 532–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.E. Pyrolysis kinetics of nylon 6–6, phenolic resin, and their composites. J. Macromol. Sci. Chem. 1969, 3, 649–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, L.H., Jr.; Huffman, M.W. Thermal degradation of nylon 66. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-1 Polym. Chem. 1971, 9, 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernik, S.; Elam, C.C.; Evans, R.J.; Meglen, R.R.; Moens, L.; Tatsumoto, K. Catalytic pyrolysis of nylon-6 to recover caprolactam. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1998, 46, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, G.; Ravens, D.A.S.; Ward, I.M. The degradation of polyethylene terephthalate by methylamine—A study by infra-red and X-ray methods. Polymer 1962, 3, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, J.R.; Haynes, S.K. Determination of the crystalline fold period in poly (ethylene terephthalate). J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Symp. 1973, 43, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M.S.; Fisher, L.D.; Alger, K.W.; Zeronian, S.H. Physical properties of polyester fibers degraded by aminolysis and by alkalin hydrolysis. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1982, 27, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.J.; Zeronian, S.H.; Marshall, M.L. Analysis of the molecular weight distributions of aminolyzed poly (ethylene terephthalate) by using gel permeation chromatography. J. Macromol. Sci. Chem. 1991, 28, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.A. Aminolysis of poly (ethylene terephthalate) in aqueous amine and amine vapor. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1996, 61, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darai, T.; Ter-Halle, A.; Blanzat, M.; Despras, G.; Sartor, V.; Bordeau, G.; Lattes, A.; Franceschi, S.; Cassel, S.; Chouini-Lalanne, N.; et al. Chemical recycling of polyester textile wastes: Shifting towards sustainability. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6857–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, S.; Maaskant-Reilink, E.; Ewing, T.A.; Julsing, M.K.; van Haveren, J. Back-to-monomer recycling of polycondensation polymers: Opportunities for chemicals and enzymes. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 947–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenull-Halver, U.; Holzer, C.; Piribauer, B.; Quartinello, F. Development of new treatment methods for multi material textile waste. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2205. [Google Scholar]

- Jeihanipour, A.; Aslanzadeh, S.; Rajendran, K.; Balasubramanian, G.; Taherzadeh, M.J. High-rate biogas production from waste textiles using a two-stage process. Renew. Energy 2013, 52, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanova, E.; Zhelev, N.; Akunna, J.C. Effect of liquid nitrogen pre-treatment on various types of wool waste fibres for biogas production. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Forgács, G.; Horváth, I.S. Enhanced methane production from wool textile residues by thermal and enzymatic pretreatment. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartinello, F.; Vajnhandl, S.; Valh, J.V.; Farmer, T.J.; Vončina, B.; Lobnik, A.; Acero, E.H.; Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M. Synergistic chemo-enzymatic hydrolysis of poly (ethylene terephthalate) from textile waste. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, S.; Han, S.F.; Yang, G.; Jönsson, L.J. Bacterial cellulose production from cotton-based waste textiles: Enzymatic saccharification enhanced by ionic liquid pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabel, S.; Arciszewski, J.; Borchers, T.H.; Therien, J.D.; Friščić, T.; Auclair, K. Solid-state enzymatic hydrolysis of mixed PET/cotton textiles. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202201613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrigwani, A.; Thakur, B.; Guptasarma, P. Conversion of polyethylene terephthalate into pure terephthalic acid through synergy between a solid-degrading cutinase and a reaction intermediate-hydrolysing carboxylesterase. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 6707–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, F.; Kawabata, T.; Oda, M. Current state and perspectives related to the polyethylene terephthalate hydrolases available for biorecycling. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8894–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Sun, Q. Complete Enzymatic Depolymerization of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Plastic Using a Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Based Whole-Cell Biocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, J.S. A Short History of Ionic Liquids—From Molten Salts to Neoteric Solvents. Green Chem. 2002, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoye, D. Solvents. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; ISBN 3527306730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumble, J. (Ed.) Laboratory Solvent Solvents and Other Liquid Reagents. In CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 102nd ed.; (Internet Version); CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Welton, T. Ionic liquids: A brief history. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, A.; Yamamoto, S. An efficient method to depolymerize polyamide plastics: A new use of ionic liquids. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2533–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C. Catalysis in Ionic Liquids. Adv. Catal. 2006, 49, 153–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Brandt, A.; Tran, K.; Zahari, S.M.S.N.S.; Klein-Marcuschamer, D.; Sun, N.; Sathitsuksanoh, N.; Shi, J.; Stavila, V.; Parthasarathi, R.; et al. Design of low-cost ionic liquids for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt-Talbot, A.; Gschwend, F.; Fennell, P.; Lammens, T.; Tan, B.; Weale, J.; Hallett, J. An economically viable ionic liquid for the fractionation of lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3078–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaadi, S.; Hummel, M.; Hellsten, S.; Härkäsalmi, T.; Ma, Y.; Michud, A.; Sixta, H. Renewable high-performance fibers from the chemical recycling of cotton waste utilizing an ionic liquid. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 3250–3258. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed, S.; Hellsten, S.; Guizani, C.; Witos, J.; Rissanen, M.; Rantamäki, A.H.; Varis, P.; Wiedmer, S.K.; Sixta, H. Recycling of superbase-based ionic liquid solvents for the production of textile-grade regenerated cellulose fibers in the lyocell process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 14217–14227. [Google Scholar]

- Jehanno, C.; Flores, I.; Dove, A.; Müller, A.; Ruipérez, F.; Sardon, H. Organocatalysed depolymerisation of PET in a fully sustainable cycle using thermally stable protic ionic salt. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekara, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Nwankwo, V. Sulfonic acid group functionalized Brönsted acidic ionic liquid catalyzed depolymerization of poly (ethylene terephthalate) in water. J. Ion. Liq. 2022, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plechkova, N.; Seddon, K. Applications of ionic liquids in the chemical industry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, T. Chapter 1: Overview of the Catalytic Chemistry of Metal Complexes. In Redox-Based Catalytic Chemistry of Transition Metal Complexes; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-83767-469-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Rong, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ding, K. Catalytic hydrogenation of cyclic carbonates: A practical approach from CO2 and epoxides to methanol and diols. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed. Engl.) 2012, 51, 13041–13045. [Google Scholar]

- Krall, E.M.; Klein, T.W.; Andersen, R.J.; Nett, A.J.; Glasgow, R.W.; Reader, D.S.; Dauphinais, B.C.; Mc Ilrath, S.P.; Fischer, A.A.; Carney, M.J.; et al. Controlled hydrogenative depolymerization of polyesters and polycarbonates catalyzed by ruthenium (II) PNN pincer complexes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 4884–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhues, S.; Idel, J.; Klankermayer, J. Molecular catalyst systems as key enablers for tailored polyesters and polycarbonate recycling concepts. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, P.; Gangwar, M.K.; Sundararaju, B. Well-defined Cp* Co (III)-catalyzed Hydrogenation of Carbonates and Polycarbonates. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.A.; Smith, S.M.; Scharbert, M.T.; Carpenter, I.; Cordes, D.B.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Clarke, M.L. On the functional group tolerance of ester hydrogenation and polyester depolymerisation catalysed by ruthenium complexes of tridentate aminophosphine ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 10851–10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar-Tobar, R.A.; Wozniak, B.; Savini, A.; Hinze, S.; Tin, S.; de Vries, J.G. Base-free iron catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of esters using EtOH as hydrogen source. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A.C. Reductive depolymerization of plastic waste catalyzed by Zn (OAc)2 2H2O. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4228–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, B.M.; Oliveira, C.; Fernandes, A. Dioxomolybdenum complex as an efficient and cheap catalyst for the reductive depolymerization of plastic waste into value-added compounds and fuels. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2419–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.P.; Völker, C.; Kramm, J.; Landfester, K.; Wurm, F.R. Plastics of the future? The impact of biodegradable polymers on the environment and on society. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Ramírez, L.A.; McKeown, P.; Shah, C.; Abraham, J.; Jones, M.D.; Wood, J. Chemical degradation of end-of-life poly (lactic acid) into methyl lactate by a Zn (II) complex. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11149–11156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Espinosa-Jalapa, N.A.; Leitus, G.; Diskin-Posner, Y.; Avram, L.; Milstein, D. Direct synthesis of amides by dehydrogenative coupling of amines with either alcohols or esters: Manganese pincer complex as catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14992–14996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; von Wolff, N.; Rauch, M.; Zou, Y.-Q.; Shmul, G.; Ben-David, Y.; Leitus, G.; Avram, L.; Milstein, D. Hydrogenative depolymerization of nylons. J. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14267–14275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Neumann, P.; Al Batal, M.; Rominger, F.; Hashmi, A.S.K.; Schaub, T. Depolymerization of Technical-Grade Polyamide 66 and Polyurethane Materials through Hydrogenation. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4176–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Werner, T. Indirect reduction of CO2 and recycling of polymers by manganese-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of amides, carbamates, urea derivatives, and polyurethanes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 10590–10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Liu, X.; Beckett, K.B.; Rothbaum, J.O.; Lincoln, C.; Broadbelt, L.J.; Kratish, Y.; Marks, T.J. Catalyst metal-ligand design for rapid, selective, and solventless depolymerization of Nylon-6 plastics. Chem 2024, 10, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacroCycle 2025. Available online: https://www.macrocycle.tech/#About (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ritz, J.; Fuchs, H.; Kieczka, H.; Moran, W. Caprolactam. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollini, F.; Brivio, L.; Innocenti, P.; Sponchioni, M.; Moscatelli, D. Influence of the catalytic system on the methanolysis of polyethylene terephthalate at mild conditions: A systematic investigation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 260, 117875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.; Ilén, E.; Sixta, H.; Hummel, M.; Niinimäki, K. Colours in a circular economy. In Circular Transitions Proceedings: A Mistra Future Fashion Conference on Textile Design and the Circular Economy; Earley, R., Goldsworthy, K., Eds.; University of the Arts London: London, UK, 2017; pp. 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, A.B.; Noor, Z.Z.; Hassan, A.; Abd Hamid, M.K.; Samsudin, S.A.; Sabeen, A.H. Current developments in chemical recycling of post-consumer polyethylene terephthalate wastes for new materials production: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textile Exchange 2021. In Textile Exchange Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report 2021; Textile Exchange: Mumbai, India, 2021.

- Bethmann, R. The Sustainable Future of Nylon. VAUDE Academy for Sustainable Business. Report for Performance Days. 2021. Available online: www.performancedays.com/loop/focus-topic/2021-12-the-sustainable-future-of-nylon.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Roos, S.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.; Spak, B.; Schwarz Bour, L.; Perzon, E.; Jönsson, C. White Paper on Textile Recycling; Mistra Future Fashion: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Yu, X.; Shao, Y.; McBride, L.; Hidalgo, H.; Yang, Y. Complete recycling of polymers and dyes from polyester/cotton blended textiles via cost-effective and destruction-minimized dissolution, swelling, precipitation, and separation. Res. Cons. Rec. 2023, 199, 107275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J. Closed-loop recycling of polymers using solvents: Remaking plastics for a circular economy. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2020, 64, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palme, A.; Peterson, A.; de la Motte, H.; Theliander, H.; Brelid, H. Development of an efficient route for combined recycling of PET and cotton from mixed fabrics. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2017, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, S.; Hummel, M.; Anghelescu-Hakala, A.; Määttänen, M.; Sixta, H. Upcycling of cotton polyester blended textile waste to new man-made cellulose fibers. Waste Manag. 2019, 97, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholamzad, E.; Karimi, K.; Masoomi, M. Effective conversion of waste polyester–cotton textile to ethanol and recovery of polyester by alkaline pretreatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 253, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uekert, T.; Singh, A.; DesVeaux, J.S.; Ghosh, T.; Bhatt, A.; Yadav, G.; Afzal, S.; Walzberg, J.; Knauer, K.M.; Nicholson, S.R.; et al. Technical, economic, and environmental comparison of closed-loop recycling technologies for common plastics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.A.; Shaver, M.P. Depolymerization within a circular plastics system. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2617–2650. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA 2024. Plastics: Material-Specific Data. In Facts and Figures About Materials, Waste, and Recycling; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ocean Recovery Alliance 2024. Towards Circular Plastics: Assessing the Role of Recycling Technologies in Tackling Plastic Pollution. Available online: https://worldplasticscouncil.org/resource/towards-circular-plastics-assessing-the-role-of-recycling-technologies-in-tackling-plastic-pollution/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Bell, L. Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception; Beyond Plastics and International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN): Bennington, VT, USA, 2023; Available online: https://d12v9rtnomnebu.cloudfront.net/paychek/103023_ChemicalRecyclingReport_web.pdf#page=8 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Milbrandt, A.; Coney, K.; Badgett, A.; Beckham, G.T. Quantification and evaluation of plastic waste in the United States. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 183, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonti, L. Reinventing Rayon. Earth Isl. J. 2023, 38, 48–53. Available online: https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/fashion-forward-towards-more-eco-friendly-rayon/ (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Grand View Research. Rayon Fiber Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/rayon-fiber-market-report (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Falk, B.; McKeever, D. Generation and recovery of solid wood waste in the US. BioCycle 2012, 53, 30–32. Available online: https://www.biocycle.net/generation-and-recovery-of-solid-wood-waste-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Manshoven, S.; Christis, S.; Vecalsteren, A.; Arnold, M.; Nicolau, M.; Lafond, E.; Mortensen, L.F.; Coscieme, L. Textiles and the Environment in a Circular Economy; Eionet Report—ETC/WMGE 2019/6; European Topic Centre Waste and Materials in a Green Economy: Mol, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, K.; Domina, T. Consumer Textile Recycling as a Means of Solid Waste Reduction. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 1999, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. State of the Art in Textile Waste Management: A Review. Textiles 2023, 3, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K.; Forster, A.L. Facilitating a Circular Economy for Textiles Workshop Report; NIST SP 1500-207; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022; Gina M. Raimondo, Secretary: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ramirez, T.D. Exploring the Feasibility and Limitations of Digital Product Passports in the Textile Industry: A Critical Assessment of Current Models. Doctoral Dissertation, Università degli Studi di Padova Department of Science and Chemistry, Padua, Italy, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12608/59346 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Güngör, B.; Leindecker, G. Digital Technologies for Inventory and Supply Chain Management in Circular Economy: A Review Study on Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, Coordinating Engineering for Sustainability and Resilience, Timișoara, Romania, 29–31 May 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridis, Y.; Argyriou, V.; Sarigiannidis, A.; Radoglou, P.; Sarigiannidis, P. Autonomous AI-Enabled Industrial Sorting Pipeline for Advanced Textile Recycling. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 29 April–1 May 2024; pp. 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Jain, S.; Islam, A.; Walluk, M.; Thurston, M. Contaminant Investigation and Pre-Processing Opportunities for Textile-To-Textile Recycling. J. Adv. Manuf. Process. 2025, 7, 70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Datko, A.; Kroell, N.; Küppers, B.; Greiff, K.; Gries, T. Near-infrared-based sortability of polyester-containing textile waste. Res. Cons. Rec. 2024, 206, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Management. Expanding Materials Solutions. In We’re Driving Sustainability: 2025 WM Sustainability Report; WM (Waste Management): Houston, TX, USA, 2025; Available online: https://sustainability.wm.com/downloads/WM_2025_Sustainability_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Bernat, K.; Zaborowska, M.; Kulikowska, D. The Growing Problem of Textile Waste Generation—The Current State of Textile Waste Management. Energies 2024, 17, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K.A.; Forster, A.L. Textiles in a Circular Economy: An Assessment of the Current Landscape, Challenges, and Opportunities in the United States. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 1038323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloyi, R.B.; Gbadeyan, O.J.; Sithole, B.; Chunilall, V. Recent Advances in Recycling Technologies for Waste Textile Fabrics: A Review. Text. Res. J. 2024, 94, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cura, K.; Rintala, N.; Kamppuri, T.; Saarimäki, E.; Heikkilä, P. Textile Recognition and Sorting for Recycling at an Automated Line Using Near Infrared Spectroscopy. Recycling 2021, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.-R.; Cantero, R.; Riba-Mosoll, P.; Puig, R. Post-Consumer Textile Waste Classification through Near-Infrared Spectroscopy, Using an Advanced Deep Learning Approach. Polymers 2022, 14, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsi, G.; Cristiano, M.; Stefano, A.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Pirola, C. Nylon recycling processes: A brief overview. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 100, 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.-B.; Lv, X.-D.; Ni, H.-G. Solvent-based separation and recycling of waste plastics: A review. Chemosphere 2018, 209, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, P.M. Recovery of Polyamide Using a Solution Process. U.S. Patent No. US5430068A, 4 July 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stefandl, R. Improved Process for Recycling and Recovery of Purified Nylon Polymer. International Patent No. WO2000029463A1, 25 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, M.; Hendrix, J.A.J.; Frentzen, Y.H.; Beckers, N.M.H. Process for Recycling Polyamide-Containing Carpet Waste. European Patent No. EP0759456B1, 9 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.A.; Dellinger, J.A. Method of Recovering Caprolactam from Mixed Waste. U.S. Patent No. US5241066, 31 August 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mauldin, L.B.; Cook, J.A. Separation of Polyolefins from Polyamides. International Patent Application No. WO2005118691A3, 2 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rietzler, B.; Manian, A.P.; Rhomberg, D.; Bechtold, T.; Pham, T. Investigation of the decomplexation of polyamide/CaCl2 complex toward a green, nondestructive recovery of polyamide from textile waste. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, e51170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi Ono, T. Method for Chemically Recycling Nylon Fibers Processed with Polyurethane. Japanese Patent Application No. JP2008031127A, 14 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, R. Treatment of Polyamides. International Patent Application No. WO2008032052A1, 20 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Yang, D. Recycling Method of wasted AIR Bag Fabrics. Korean Patent No. KR20120005255A, 23 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Takayuki, M. Recycling Method of Air Bag Scrap Cloth Made of Nylon. Japanese Patent Application No. JP2017124553A, 20 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, R.; Kevin, R.; Gerzevske, K.R. Method for Removing Color from Polymeric Material. U.S. Patent No. US7947750B2, 24 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, B.; Yang, Y. Complete separation of colorants from polymeric materials for cost-effective recycling of waste textiles. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zou, X.; Wong, W.K. Computer vision-based color sorting for waste textile recycling. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P.; Harlin, A. The Need and Challenges of Decolorization of Textile Waste in Textile Recycling. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, V.; Chattopadhyay, S.K.; Raja, A.S.M.; Shakyawar, D.B. Waste management in coated and laminated textiles. In Waste Management in the Fashion and Textile Industries; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas-Abadi, M.S.; Tomme, B.; Goshayeshi, B.; Mynko, O.; Wang, Y.; Roy, S.; Kumar, R.; Baruah, B.; De Clerck, K.; De Meester, S.; et al. Advancing textile waste recycling: Challenges and opportunities across polymer and non-polymer fiber types. Polymers 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F. Introductory chapter: Textile manufacturing processes. Text. Manuf. Process. 2019, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.K. Manufacturing, properties and tensile failure of nylon fibres. In Handbook of Tensile Properties of Textile and Technical Fibres; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2009; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. “Circular Economy Principles” What is a Circular Economy? 2022. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Porter, M.E. The value chain and competitive advantage. Underst. Bus. Process. 2001, 2, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. Embodied energy and economic valuation. Science 1980, 210, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolano, L.; Foschi, J.; Caldeira, C.; Huygens, D.; Sala, S. Understanding textile value chains: Dynamic Probabilistic Material Flow Analysis of textile in the European Union. Res. Cons. Recy. 2025, 212, 107888. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneve, Switzerland, 2006.

- Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Environmental impact of textile reuse recycling—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanga-Labayen, J.P.; Labayen, I.V.; Yuan, Q. A review on textile recycling practices and challenges. Textiles 2022, 2, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarioğlu, E.; Kaynak, H.K. PET bottle recycling for sustainable textiles. In Polyester Production Characterization and Innovative Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A.D.; Kratochvil, P.; Stepto, R.F.T.; Suter, U.W. Glossary of Basic Terms in Polymer Science. Pure Appl. Chem. 1996, 68, 2287–2311. Available online: https://media.iupac.org/publications/pac/1996/pdf/6812x2287.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Raj, C.S.; Arul, S.; Sendilvelan, S.; Saravanan, C.G. Biogas from Textile Cotton Waste—An Alternate Fuel for Diesel Engines. Open Waste Manag. J. 2009, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Isci, A.; Demirer, G.N. Biogas production potential from cotton wastes. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.Z.; Talib, A.R. Recycled medical cotton industry waste as a source of biogas recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4413–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamawand, I.; Sandell, G.; Pittaway, P.; Chakrabarty, S.; Yusaf, T.; Chen, G.; Seneweera, S.; Al-Lwayzy, S.; Bennett, J.; Hopf, J. Bioenergy from Cotton Industry Wastes: A Review and Potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, S.; Lazić, V.; Veljović, Đ.; Mojović, L. Production of bioethanol from pre-treated cotton fabrics and waste cotton materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 164, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, C.; Phan, A.N.; Yang, Y.-B.; Sharifi, V.N.; Swithenbank, J. Ignition and burning rates of segregated waste combustion in packed bed. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youhanan, L. Environmental Assessment of Textile Material Recovery Techniques. Examining Textile Flows in Sweden. Master’s Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. Available online: www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:630028/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Plastics Industry Association. Recycling is Real. 2025. Available online: https://recyclingisreal.com/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Statista. U.S. Plastics Industry—Statistics & Facts; Statista Research Department: Hamburg, Germany, 2024; Available online: www.statista.com/topics/7460/plastics-industry-in-the-us/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Center for Sustainable Systems. Plastic Waste Factsheet. Pub. No. CSS22-114; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2024.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Ocean Studies Board; Committee on the United States Contributions to Global Ocean Plastic Waste. In Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Di, J.; Reck, B.K.; Miatto, A.; Graedel, T.E. United States plastics: Large flows, short lifetimes, and negligible recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook. 2022. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?tenant=archive&df%5bds%5d=DisseminateArchiveDMZ&df%5bid%5d=DF_PLASTIC_USE_8&df%5bag%5d=OECD&lom=LASTNPERIODS&lo=5&to%5bTIME_PERIOD%5d=false (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Allen, D.; Spoelman, N.; Linsley, C.; Johl, A. The Fraud of Plastic Recycling. Center for Climate Integrity. 2024. Available online: https://climateintegrity.org/uploads/media/Fraud-of-Plastic-Recycling-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parnell, K.; Rolston, A.; Hilton, B.; Luccitti, A. Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Review of Technology, Practice, and Opportunity. Recycling 2025, 10, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060225

Parnell K, Rolston A, Hilton B, Luccitti A. Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Review of Technology, Practice, and Opportunity. Recycling. 2025; 10(6):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060225

Chicago/Turabian StyleParnell, Kyle, Abigail Rolston, Brian Hilton, and Allen Luccitti. 2025. "Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Review of Technology, Practice, and Opportunity" Recycling 10, no. 6: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060225

APA StyleParnell, K., Rolston, A., Hilton, B., & Luccitti, A. (2025). Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Review of Technology, Practice, and Opportunity. Recycling, 10(6), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060225