Abstract

Bangladesh generates approximately 3000 tons of plastic waste daily, and high mismanagement leads to substantial discharge into soils, rivers, and oceans. Limited research exists on plastic pollution along Cox’s Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh, with no studies spanning the entire coast; this study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the full coastline. This study investigates the abundance, types, and distribution of macro-, meso-, and microplastics in sediments from 23 stations covering Tourism, Active, and Less Active areas. Plastics were classified by size, shape, color, and polymer composition using stereomicroscopy and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), while spatial patterns of microplastic polymers were analyzed using Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation. A total of 11,558 plastic particles were identified, with microplastics dominating (409.04 particles/m2), followed by mesoplastics (60.7 particles/m2) and macroplastics (32.8 particles/m2). Expanded polystyrene (EPS) and fragments were the most prevalent shapes, while transparent-white particles dominated in color. Polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene (PE) comprised over 95% of polymers. IDW mapping highlighted Tourism, urban, and industrial zones as microplastic hotspots, with higher abundances in tourism areas. These findings provide a baseline for monitoring coastal plastic pollution and emphasize improved plastic management and recycling, contributing globally to understanding contamination in rapidly urbanizing, tourism-driven developing regions.

Keywords:

marine plastic; FTIR spectroscopy; interpolation; polypropylene; polystyrene; polyethylene 1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, plastic has become an integral part of daily life due to its affordability and versatility [1,2]. Since its introduction in the 1950s, global production has risen sharply, reaching about 460 million tons by 2019 [3,4] and 359 million tons in 2018. Annually, around 6300 metric tons of plastic waste are generated, with only 9% recycled, 12% incinerated, and nearly 79% persisting in the environment [5,6]. Plastic waste is now widespread across soils, sediments, and aquatic systems, from freshwater to marine environments [7,8]. Due to its persistence, it accumulates on riverbeds, sea surfaces, and shorelines [9,10,11], where it gradually breaks down into smaller fragments known as microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics [12,13,14].

Macroplastics (>5 mm) are commonly found in marine environments, originating from recreational, industrial, and accidental sources, and pose adverse effects on marine organisms [15,16,17,18]. Microplastics (<5 mm) are smaller polymer fragments formed by the degradation of larger plastics [19,20]. They are categorized as primary—directly released from manufacturing, recycling, or microbeads—and secondary, produced through the weathering of macroplastics by waves, wind, and UV radiation [21,22,23].

Microplastics originating from land sources often bypass treatment facilities and travel through rivers, streams, storm drains, and sewage systems until they reach the ocean [22]. This movement highlights how land-based pollution is a major contributor to the microplastic contamination of marine environments. Moreover, rivers frequently become polluted with microplastics due to human activities, such as sewage discharge and wastewater treatment plants, which eventually release these particles into the oceans [24,25,26], causing pollution in both the water and surrounding sediments [27]. Previous studies have reported that microplastic abundance is positively correlated with local population density [28].

Bangladesh, one of the fastest-growing countries in Asia, is densely populated and experiencing rapid industrialization, particularly in its expanding plastic sector [29,30,31]. With economic growth comes increased plastic consumption, which further intensifies waste generation. As the economy grows, plastic use per person is also increasing, and Bangladesh now produces about 3000 tons of plastic waste every day [32]. However, the country’s plastic recycling systems and infrastructure are still in the early stages of development.

In December 2021, Bangladesh introduced a multisectoral action plan for sustainable plastic management, aligned with SDG 14. The plan outlined strategies and responsibilities across three timeframes: short-term (2022–2023), medium-term (2024–2026), and long-term (2027–2030), with four specific goals. One goal (Target 3) was to recycle 50% of plastic waste by 2025 and increase this to 80% by 2030. Another goal (Target 4) aimed to reduce annual plastic waste generation by 30% by 2030 [33].

A large amount of plastic continues to pollute land and water ecosystems due to weak governance, limited progress in recycling, and low public awareness [32]. This situation has direct consequences for regional water bodies such as the Bay of Bengal. The Bay of Bengal, bordering Bangladesh and India, is experiencing an increasing accumulation of both macroplastics and microplastics [34,35,36].

Cox’s Bazar features the world’s longest unbroken natural sandy beach (~120 km) along the southeastern coastline of Bangladesh (~710 km) and is renowned for its remarkable natural beauty, including tertiary hills, dunes, and the open sea [36,37,38]. The region is a major tourist destination, attracting around two million national and international visitors during the peak season from November to March, and supports numerous cultural and religious events [37]. Such intense human activity, including beachside hotels, restaurants, and recreational operations, has led to substantial plastic waste accumulation along the shoreline [37]. The Bakkhali and Matamohori rivers flow into the Maheshkhali Channel, carrying tons of domestic, agricultural, and industrial waste, mostly plastic debris [39]. Maheshkhali Channel, a tidal stream dividing Maheshkhali Island from the mainland area of Cox’s Bazar, a district in southeastern Bangladesh, exemplifies how river systems serve as pathways for inland plastic pollution to reach coastal waters.

A physical analysis of waste at the Kostori Para landfill in Cox’s Bazar found that 17 percent consists of recyclable plastics. At Laboni Beach, 37 percent of the plastic waste is recyclable, while at Inani Beach, the figure is even higher at 41 percent [33]. These findings highlight the potential for improving plastic waste recovery and recycling efforts in the region. Recent reviews have indicated that micro(nano)plastics can influence key biogeochemical processes, particularly by affecting soil and sediment nutrient cycling through interactions with microorganisms and associated enzymatic activities [40,41]. This suggests that the increasing plastic contamination may not only threaten aquatic systems but also disrupt essential soil functions.

Many studies have investigated the presence and spread of MPs in beach sediments in neighboring countries [2,42,43,44], but only a handful have focused on Bangladesh’s coastal and marine environments. Although recent research has been conducted in Cox’s Bazar, southeastern Bangladesh [37,45,46], and other regions [27,39,47], year-by-year monitoring data on plastic pollution are still lacking. As a result, it remains difficult to evaluate long-term changes in pollution levels along the Bangladesh coast. Moreover, previous studies in Cox’s Bazar have mainly concentrated on tourist-centric areas rather than the entire coastline. To address this gap, the present study provides the first comprehensive assessment of macro-, meso-, and microplastics across the full stretch of Cox’s Bazar beach, along with spatial mapping of microplastic polymers.

Therefore, this study aims to: (1) quantify and characterize the abundance and polymer types of macro-, meso-, and microplastics in Cox’s Bazar beach sediments; (2) analyze the spatial distribution of microplastic polymers using interpolation mapping; and (3) evaluate the variation in microplastic abundance across different zones. The findings are expected to serve as a valuable baseline dataset for future year-to-year comparisons and highlight the importance of targeted waste management and recycling efforts in coastal areas. Moreover, this study contributes to the broader understanding of plastic contamination in rapidly urbanizing and tourism-driven developing regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Cox’s Bazar is situated in the southeast of Bangladesh along the eastern coastline, facing the Bay of Bengal to the southwest. According to the Population and Housing Census 2022, the total population of this district is 2,823,268 within an area of 2491.85 sq.km. The normal maximum temperature is 32.3 °C in May [48], while the normal minimum temperature is 15 °C in January [49]. Average monthly rainfall ranges from 924.6 mm in July to 4.1 mm in January [50]. This research covers approximately 100 km of coastline parallel to the Cox’s Bazar–Teknaf marine drive. This coastline experiences two low and two high tides daily.

Among the numerous stretches of Cox’s Bazar beach, Laboni, Sugandha, Kolatoli, Himchari, and Inani are particularly well known as recreational hotspots, attracting a high concentration of visitors. This increased tourism activity is supported by rapid growth in accommodation facilities, including more than 400 hotels, motels, and guesthouses [45].

This beach consists mainly of Holocene sediment deposits [51] and is highly susceptible to tidal fluctuations and long-shore currents. It is frequently impacted by cyclones and storm-induced washovers [52]. Recent studies [36,37,45] have reported high levels of MPs in these beach sediments.

2.2. Sampling Design and Zonal Classification

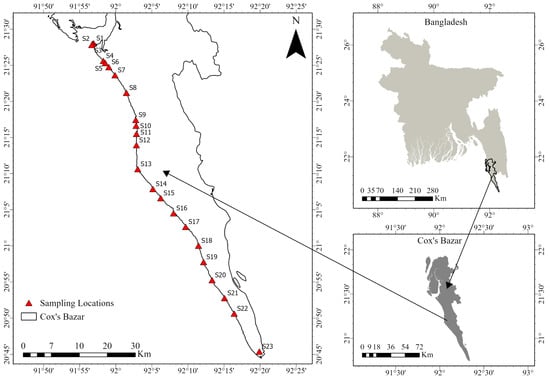

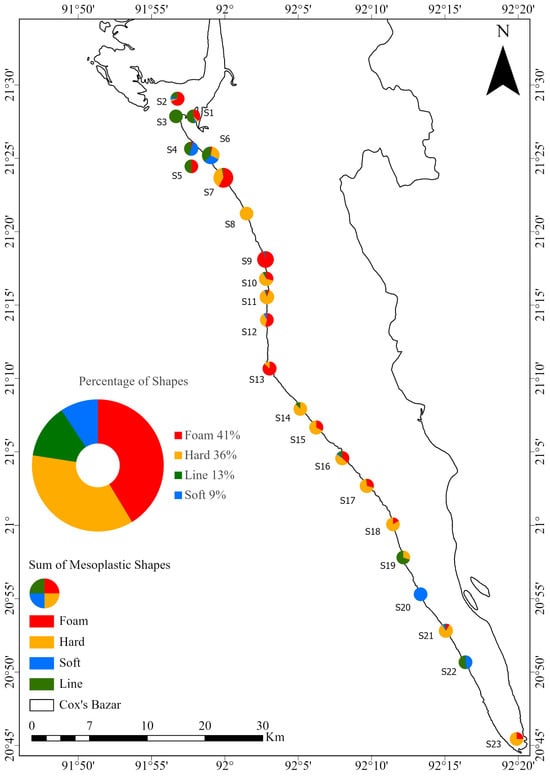

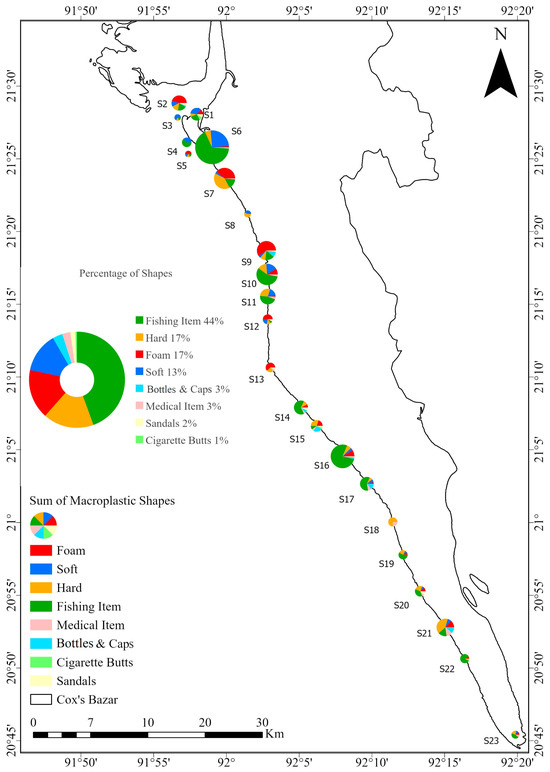

A total of 23 stations were selected along the ~100 km Cox’s Bazar–Teknaf coastline to ensure coverage of areas with varying human activities (Figure 1). Based on field observations during sampling, the stations were grouped into three functional zones to facilitate comparative analysis:

Figure 1.

Location of the sediment sampling points along Cox’s Bazar beach, southeastern Bangladesh; map developed using ArcGIS Pro 3.3.0. One sample was taken from each station.

- Tourist Zones (S4–S13): Locations characterized by intensive recreational use, small vendors, and high visitor presence.

- Active Fishing Zones (S1–S3, S16, S22): Areas with fishing-related activities such as fish landing, net drying, processing, buying and selling, and abandoned nets.

- Less Active Zones (S14, S15, S17–S21, S23): Sites with relatively lower direct anthropogenic activity.

During data collection, stations were selected to represent both high-activity and low-activity coastal stretches. Stations S1–S3 were identified as dry-fishing zones, where nets were spread for drying and boats were used mainly for transporting commodities, although active fish trading was limited. Numerous macroplastic items, particularly food packets, were also observed around S1.

Stations S9–S11 contained several fish and shrimp hatcheries but no beach-based fishing. Station S9 (BORI Beach) has recently become a popular tourist site, with activities such as small shops and coconut stalls contributing to plastic litter. A nearby river outlet, Reju Khal, likely serves as an additional source of plastic debris. Accordingly, stations S4–S13 were categorized as Tourist Zones.

Stations S16 (Shamlapur) and S22 (Sabrang) showed intense fishing operations, including landing, transport, processing, selling, and net repair, and were thus classified as Active Zones. The remaining stations were designated as Less Active Zones. Therefore, the study area consisted of three functional categories: (1) Tourism, (2) Active, and (3) Less Active.

The details of all 23 sampling stations, including coordinates and zone classifications, are summarized in Table 1. These classifications were used for statistical comparisons of microplastic abundance among different coastal use zones.

Table 1.

Geographic coordinates and zone categories of the 23 sampling stations.

2.3. Plastic Sample Collection

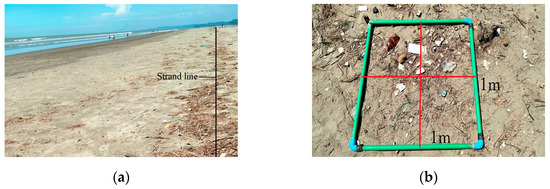

During low tide in October 2024, surface sediment samples were collected, mainly from the most recent visible strandline. In 2–3 stations where the strandline was absent due to narrow beach width or post-tidal washout, samples were taken from the vegetation line, which marked the furthest tidal reach. Microplastics (<5 mm, particularly the larger fraction ~1–5 mm) and mesoplastics (5 mm–2.5 cm) were collected using a stainless-steel sieve with mesh sizes of 710 µm and 5.6 mm, respectively, while macroplastics (>2.5 cm) were collected directly within the 1 m × 1 m quadrat (Figure 2). Sampling and handling procedures followed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) guidelines [53]. All topsoil was sieved, and the collected debris was stored in airtight zipper bags and transported to the Bangladesh Oceanographic Research Institute (BORI) laboratory for further analysis.

Figure 2.

Collection and identification of plastic samples: (a) Samples collected from the strandline; (b) 1 m × 1 m quadrat; (c) sieving for plastic samples; macroplastics collected directly from the quadrat; (d) transportation to the laboratory in a zipper bag; (e) visual separation of plastics from debris; (f) identification under a stereoscopic microscope.

2.4. Contamination Control

After debris removal, samples were individually placed in glass Petri dishes covered with aluminum foil. All glassware and stainless-steel sieves were rinsed with deionized water, dried, and handled carefully. Contamination was minimized by avoiding polyester fabrics and using cotton aprons and nitrile gloves during sampling and processing. The Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) crystal was cleaned with isopropanol prior to polymer analysis. Procedural blanks and field duplicate samples were not included in this campaign; however, future monitoring will incorporate these controls to enhance data reliability.

2.5. Visual Observation, Classification, and FTIR Analysis

The plastic items were first visually inspected [44,54] (p. 203) for size, shape, and color under a Motic SMZ-171 (Motic, HongKong, China) stereomicroscope at 100× magnification. After separation from debris, all plastic samples were categorized and counted according to their shape, color, and polymer type.

All collected MPs were divided into six shape groups: EPS, foam, pellet, fragment, line, and film. Mesoplastics were divided into four groups: foam, hard, soft, and line. EPS and sponge-like foam were combined into the foam category due to the small number of sponge particles; although EPS was abundant, it was not counted separately. Fragments and large plastics were classified as hard plastics, while films or thin plastics were categorized as soft plastics. Macroplastics were grouped into eight categories: foam, soft, hard, fishing items, medical items, bottles and caps, cigarettes, and sandals. All micro- and mesoplastic particles were assigned to six color groups.

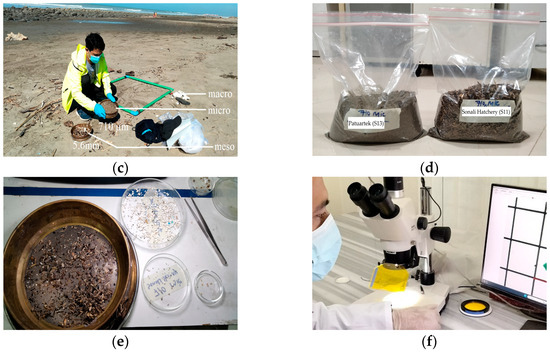

Plastic particles were analyzed using FTIR to determine their polymer composition and corresponding functional groups. Polymer types were identified using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FT-IR, LabSolutions IR, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an ATR diamond crystal. Infrared absorption spectra were controlled over 4000–400 cm−1, averaging 40 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1 (Figure 3). The obtained spectra were matched against a polymer reference library to determine the types of microplastics present [39,55]. A similarity index exceeding 80% between the sample spectra and reference spectra was used as the identification threshold [46].

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of microplastics identified in this study, showing the three most common polymer types: (a) polyethylene (PE), (b) polypropylene (PP), and (c) polystyrene (PS). Each type shows one sample spectrum and one library spectrum.

2.6. Data Analysis

Each station represents one data point per plastic category (macro-, meso-, and microplastics). Data were initially organized in MS Excel for graphical representation. Statistical comparisons among different zones were performed using one-way ANOVA and Tehman’s test in SPSS (version 30), with significance considered at p < 0.05. Spatial distribution and mapping of plastic types were conducted in ArcGIS Pro 3.3.0 using IDW interpolation to visualize hotspots along the coastline.

2.7. Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) Interpolation

The IDW interpolation technique was applied to examine the spatial distribution and patterns of microplastics. This method estimates values at unsampled locations by weighing nearby measured values more heavily, giving greater importance to those that are closer in distance. It uses an inverse square distance calculation, as shown in Equation (1), where zp is the predicted value at an unsampled location, zi represents the measured value at each sampling point, di is the distance between points, and p is the power parameter controlling the influence of distance [56].

The resulting maps were generated in ArcGIS Pro using classified symbology to illustrate spatial patterns and microplastics distributions [56]. IDW is particularly suitable for datasets with unevenly distributed sampling points, a common feature of field-based environmental studies [57]. Its adjustable power parameter enables the detection of localized gradients, making it effective for mapping fine-scale spatial variations influenced by both environmental and human factors.

Based on FTIR, only PP, PE, and PS were included in the interpolation analysis. Interpolation outputs were divided into 10 classes using distinct color bands, and the quantile classification method was applied to ensure equal sample counts per class. A power value of 2 was used, and the neighborhood search was set to standard, with a maximum of 15 and a minimum of 10 neighboring points.

3. Results

3.1. Abundance and Distribution of Microplastics, Mesoplastics, and Macroplastics

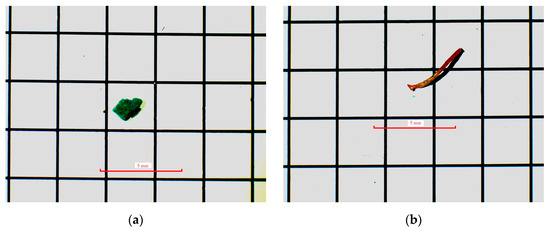

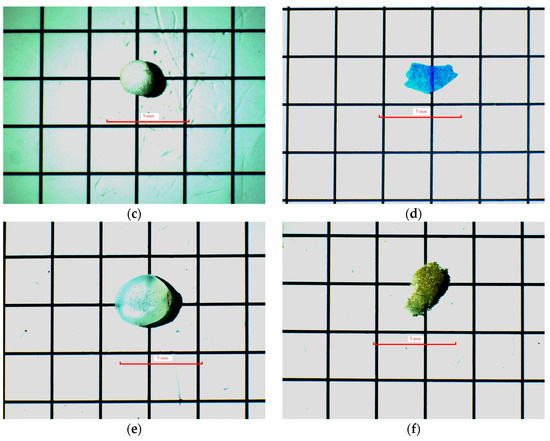

Some microscopic photos of microplastics are shown in Figure 4. The total number of plastic particles found at the 23 stations was 11,558. Among them, microplastics accounted for 9408 particles, with an average of 409.04 particles/m2. The decreasing sequence of total MPs was S6 > S7 > S11 > S9 > S13 > S10 > S4 > S21 > S16 > S17 > S12 > S18 > S2 > S15 > S1 > S3 > S23 > S19 > S14 > S5 > S20 > S8 > S22, with a range of 5–2352 particles/m2. The highest number of MPs was found at S6, with 2352 particles/m2, while the lowest number of MPs was found at S22, with 5 particles/m2 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Microplastics identified in sediment samples under a stereo zoom microscope: (a) fragment, (b) line, (c) expanded polystyrene (EPS), (d) film, (e) pellet, and (f) foam; red line indicates the scale bar. Under a Motic SMZ-171 stereomicroscope at 100× magnification.

Figure 5.

Abundance of macro-, meso-, and microplastics in beach sediment samples in Cox’s Bazar. From S1 to S23, each station represents the total number of plastics in particles/m2. Station S6 recorded the highest number of MPs, while stations S6–S13 exhibited the maximum concentrations of plastic particles.

The total number of mesoplastics was 1396 particles, with an average of 60.7 particles/m2. The decreasing sequence of total mesoplastics was S7 > S6 > S9 > S11 > S10 > S17 > S4 > S15 > S16 > S21 > S2 > S13 > S22 > S1 > S18 > S14 > S12 > S19 > S8 > S23 > S3 > S5 > S20, with a range of 3–386 particles/m2. The highest number of mesoplastics was found at S7, with 386 particles/m2, while the lowest number was found at S5 and S20, with 2 particles/m2 (Figure 5).

The total number of macroplastics was 754 particles, with an average of 32.8 particles/m2. The decreasing sequence of total macroplastics was S6 > S16 > S10 > S7 > S9 > S21 > S11 > S2 > S14 > S17 > S1 > S15 > S20 > S12 > S4 > S13 > S18 > S19 > S22 > S23 > S8 > S3 > S5, with a range of 6–163 particles/m2. The highest number of macroplastics was found at S6, with 163 particles/m2. The lowest number was found at S3 and S5 with 6 particles/m2 (Figure 5).

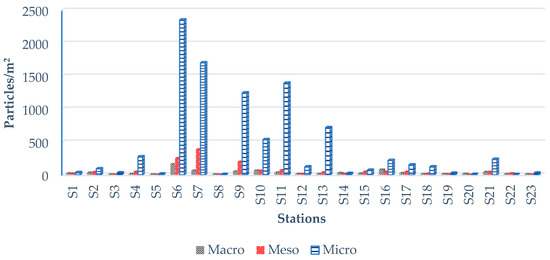

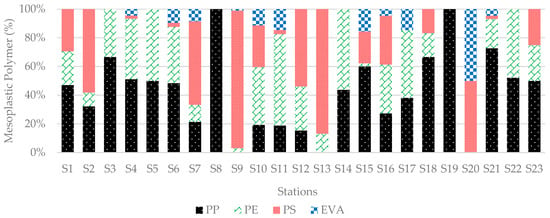

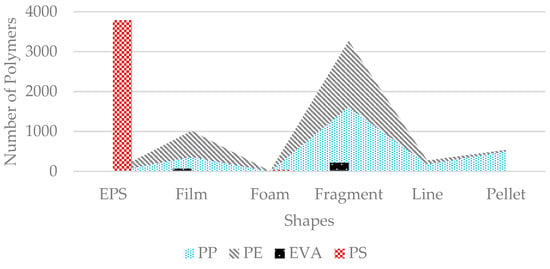

3.2. Shapes of Microplastics, Mesoplastics, and Macroplastics

EPS and fragments were the most abundant types of MPs found in beach sediments. EPS accounted for 3800 particles in the 23 stations, representing 40.39%, while fragments accounted for 3497 particles, representing 37.17%. The other types were film (Filament) at 1160 particles (12.33%), pellets at 564 particles (5.99%), line at 288 particles (3.06%), and foam at 99 particles (1.05%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distribution of different microplastic shapes at each station. Each station is represented by a pie chart showing shape-specific concentrations, with red indicating EPS, which was the most abundant. The central pie chart represents the overall percentage of each shape in the total MPs sample.

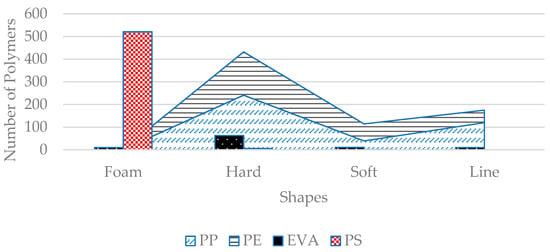

Foam and hard plastics were the most abundant types of mesoplastics found in beach sediments. Foam accounted for 577 particles, representing 41.33%. Hard plastics accounted for 504 particles, representing 36.10%. The other types were line at 185 particles (13.25%) and soft at 130 particles (9.31%). The combined percentage of foam and hard plastics was 77.44%, which was very similar to the total percentages found in microplastics for EPS and fragments (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of mesoplastic shapes at each station. Each station is shown as a pie chart indicating shape-specific concentrations, with red representing foam (including EPS), the most abundant type. The central pie chart shows the overall percentage of each shape in the total MPs sample.

For macroplastics, fishing items were the most numerous, with 335 items, representing 44.43%. Other types included hard (129 items), foam (126 items), and soft (101 items), making up 47.21%. The percentage of bottles (3.45%) did not reflect the actual observation. During the sample collection, many plastic and PET bottles were found scattered around the beach. A larger sampling area, such as a 10 m × 10 m quadrat, may provide more accurate results for macroplastics. Bottles, medical items, sandals, and cigarettes accounted for 26 items, 20 items, 13 items, and 4 items, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Distribution of macroplastic shapes at each station. Each station is represented by a pie chart showing shape-specific concentrations, with green indicating fishing items, the most abundant type. The central pie chart shows the overall percentage of each shape in the total macroplastic sample.

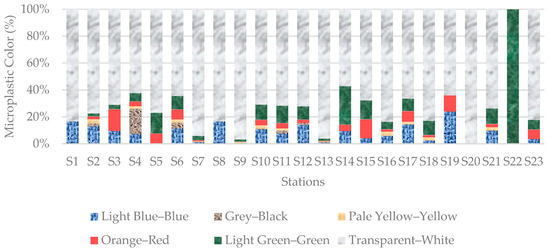

3.3. Color of Microplastics and Mesoplastics

The Mp colors from beach sediments samples in order of abundance were transparent–white (7453 particles, 79.22%), light green–green (685 particles, 7.28%), light blue–blue (597 particles, 6.35%), orange–red (330 particles, 3.51%), grey–black (202 particles, 2.15%) and pale yellow–yellow (141 particles, 1.50%) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Distribution of microplastic colors in sediment samples from all stations. Transparent–white, representing EPS, was the dominant color.

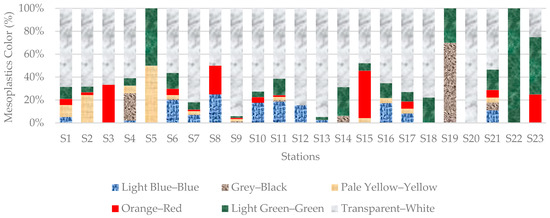

The mesoplastic colors from beach sediments samples in order of abundance were transparent–white (994 particles, 71.20%), light green–green (142 particles, 10.17%), light blue–blue (126 particles, 9.03%), orange–red (55 particles, 3.94%), pale yellow–yellow (51 particles, 3.65%) and grey–black (28 particles, 2.01%) (Figure 10). Color variations were not observed for macroplastics due to the presence of multiple colors in many items.

Figure 10.

Distribution of mesoplastic colors in sediment samples from all stations. Transparent-white, representing foam (including EPS), was the dominant color.

3.4. Polymer Types of Microplastics, Mesoplastics, and Macroplastics

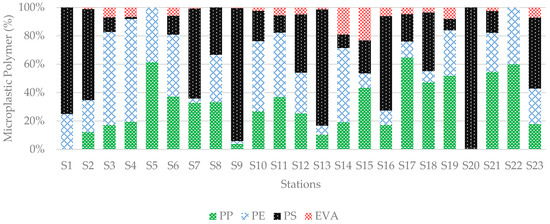

In microplastics, twelve polymer types were identified. Among them, three types were the most frequent: Polystyrene (PS), Polypropylene (PP), and Polyethylene (PE). PS showed the highest abundance of 40.85% in sediment samples, followed by PP at 28.30% and PE at 25.91%. This study found Ethylene Vinyl Acetate (EVA) in a 3.48% ratio. All four types made up 98.53% in total (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Distribution of microplastic polymers in sediment samples collected from all stations. PS was the dominant polymer, whereas PE and PP were present in relatively similar amounts.

Other identified polymers in MPs included Polyurethane (PU), High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE), Poly Diallyl Phthalate (PDAP), Nylon, Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT), Poly Methyl Pentene (PMP), Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), and Poly Vinyl Chloride (PVC), together representing 1.47%.

In mesoplastics, three polymer types were more frequent among the seven detected types. PS showed the highest abundance of 37.82% in sediment samples, followed by PP at 28.80% and PE at 22.99%. This study found EVA in a 6.73% ratio. All four types made up 96.35% in total (Figure 12). Other identified polymers observed in mesoplastics were PU, PBT, and ABS, forming 3.65% in total.

Figure 12.

Distribution of mesoplastic polymers in sediment samples collected from all stations. PS was the dominant polymer, whereas PE and PP were present in relatively similar amounts.

The PS number was highest in MPs due to the large number of EPS particles. All EPSs were PS-based (3788 particles) except for 12 particles found from ABS types, which are also styrene-based polymers. PP and PE were found in their highest number in fragment shapes at 1617 and 1652, respectively. In film shapes, the PE number was the most abundant (656 particles), as it represents soft plastic, especially polythene bags or food packing products. Most of the pellets represent (503 particles) PP types of polymers (Figure 13). PP was also the most abundant in the line shapes of plastics, which mainly represent ropes or fibers from fishing nets. Although the number of foams was very low, most of them represented PS (43 particles) and PU (40 particles).

Figure 13.

Polymer concentration in various shapes of microplastics. EPS corresponds only to PS; PE was most abundant in fragments, while pellets were mainly composed of PP.

PS was also the most abundant mesoplastic due to the high number of foams found in the mesoplastics. All foams were PS-based polymer (521 particles) except for 10 particles found from EVA types and 2 particles from PP types. In mesoplastics, all EPSs were considered in the foam category. PP and PE were highest in number in the hard plastic group, at 242 and 191, respectively. In soft plastics, PE was the most abundant (75 particles), as it represents polythene bags or food packing products. PP was the most abundant in line-shaped plastics, mainly representing ropes or fibers from fishing nets (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Polymer concentration in various shapes of mesoplastics. Foam corresponds only to PS; PP was most abundant in hard plastics, while soft plastics were mainly composed of PE.

For macroplastics, the largest portion of plastic polymers was PP (50.93%), followed by PE (24.54%), PS (12.07%), and EVA (5.44%), accounting for a total of 92.97%. In addition, nine other polymer types like PU, Nylon, HDPE, PBT, PVA, POM, SEB, ABS, and PET collectively made up the remaining 7.03%.

In many cases, a single macroplastic item contained multiple polymers. For example, sandals’ laces were PVC, while the foam portion was EVA. The food and chocolate packets consisted of PP and PE, sometimes made in two to three layers, each with a different polymer. The bottle caps were commonly PE, whereas bottles were typically PET or PP. Some large items were considered to be a single macroplastic based on shape, but had significantly greater weight than mesoplastics and microplastics. These items could degrade into smaller particles over time. Although the total mass of these large items was not measured in this study, it should be included in future assessments.

The polymer composition of micro-, meso-, and macroplastics revealed a consistent dominance of PP, PE, and PS, with EVA appearing in smaller proportions. PP was most abundant in macroplastics, whereas PS predominated in micro- and mesoplastic fractions. Detailed comparative data on polymer distributions across size classes are provided in Table A1 (see Appendix A.1).

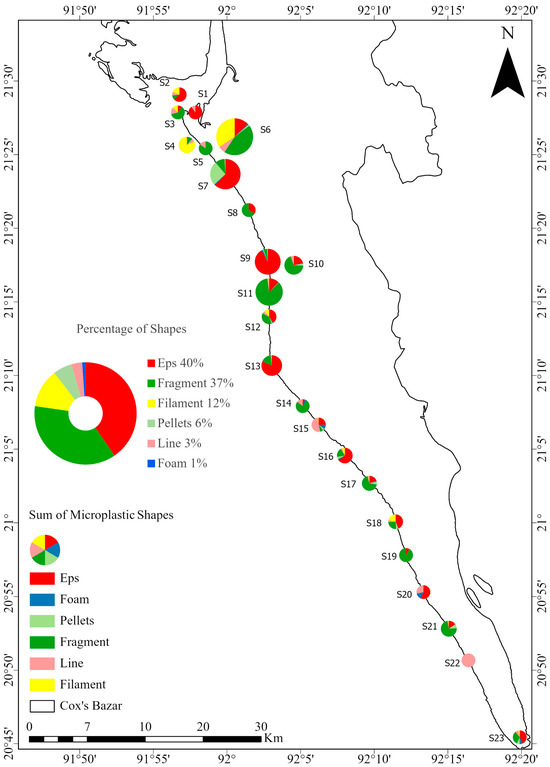

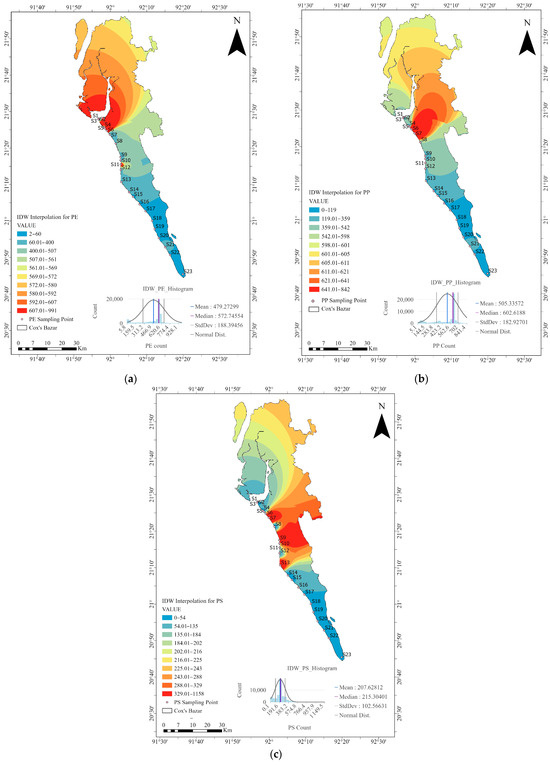

3.5. Spatial Distribution Mapping of Microplastic Polymers Using IDW Interpolation

The IDW results for PE showed that the Maheshkhali Channel area is the most heavily polluted with this type of plastic (Figure 15a). The IDW results for the PP and PS maps focused more on the middle part of the study area, which corresponds to the city and industrial area. Stations 4 to 13 are exclusively tourism activity zones, although some fishing activities were also observed in this area. Several fish hatcheries were located near stations 9 to 11; however, these activities are not directly related to the plastic pollution and are away from the beach.

Figure 15.

Spatial distribution of microplastic polymers in Cox’s Bazar using IDW interpolation: (a) PE, (b) PP, and (c) PS. The red zones indicate areas of the highest concentration of PE around the Maheshkhali Channel, and of PP and PS in the urban and industrial areas of Cox’s Bazar. The histograms show the mean, median, and standard deviation of the IDW-interpolated values for each polymer.

Population density was also very high in the red zones in the IDW results for PP and PS (Figure 15b,c). PS products mainly originated from buoys and fish packing containers. PP was very common in fragment types of plastics (61%) in this study area, indicating improper solid waste management in the urban or city area, as fragmented MPs typically originate from the breakdown of larger plastic items.

3.6. Microplastic Pollution Across Different Zones of Cox’s Bazar Beach

Based on the IDW results, this study found that high concentrations of PS, PP, and PE microplastics were located near the Tourism Zone. Therefore, microplastic data from the three zones—Tourism, Active, and Less Active—were analyzed to assess whether the differences among them were statistically significant. SPSS results indicated that Tourism sites had a significantly higher mean microplastic count (836.10 items) compared to Active (77.00) and Less Active (82.75) sites, suggesting a strong influence of tourism on microplastic pollution (Table 2). The overall mean microplastic level was 409.04, heavily influenced by the high values from the Tourism Zone. Levene’s test was statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated. Welch’s ANOVA also returned a significant result (p = 0.044), confirming a statistically significant difference in mean microplastic levels among the zones. Post hoc analysis using Tamhane’s T2 test revealed significant differences between Tourism and both Active and Less Active zones (p < 0.05), while no significant difference was found between Active and Less Active zones (p = 0.999), indicating similar microplastic levels in those areas.

Table 2.

Mean microplastic counts in different beach zones and group differences.

Table A2 (see Appendix A.2) summarizes the total particle counts, mean, SD, and range per station for micro-, meso-, and macroplastics across the three zones, providing a statistical overview of abundance and spatial variability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Drivers of Plastic Abundance

The present study recorded 11,558 plastic particles across 23 stations, with MPs dominating at 9408 particles (409.04 particles/m2), followed by mesoplastics (1396 particles; 60.7 particles/m2), and macroplastics (754 particles; 32.8 particles/m2). These values are higher than those reported in previous studies conducted in the same area, though lower than levels recorded in some international beaches, such as those in Korea and Mexico. In contrast, lower MP counts have been reported in India and the nearby Maheshkhali Channel, Bangladesh. Table 3 summarizes MP abundances on different beaches, expressed in particles/m2.

Table 3.

Abundance of microplastics in various regions around the world (particles/m2).

Recent studies in Cox’s Bazar beach sediments [37] found a mean abundance of 368.68 ± 10.65 items/kg, with fiber being the most common type (53%). Another study [45] found a much lower mean abundance of 8.1 ± 2.9 particles/kg, where fragments were most dominant. These differences in Rahman’s study are likely due to differences in sample collection methods.

Rahman et al. [45] collected samples from three sub-zones (swash zone, beach face, and wrack line), with the wrack line showing the highest mean abundance (22.50 ± 6.47 particles/kg). Hossain et al. [37] sampled during the pre-tourist season (August to October) in 2019, while Rahman et al. collected samples between August and December 2019. Both studies used quadrats and collected samples during low tide.

The present study consistently followed the strandline. When the beach width was narrow, the vegetation line was used instead. The sampling method was purposive sampling, and all topsoil within the quadrat was collected and sieved. This study aimed to determine the amount of macro-, meso-, and microplastics present within the same quadrat.

Variation in particle counts among studies underscores the influence of sampling process, time, and location. For instance, at Kalatoli Beach (Station 6), one of the most visited sites, numerous plastic items were found trapped in vegetation near the strandline, resulting in higher MP counts. Tidal action, precipitation, wind, and human activities are key factors affecting plastic abundance across zones.

The observed accumulation of micro-, meso-, and macroplastics indicates ecological risks for the marine environment. Plastics can cause ingestion and entanglement, leading to internal injuries, reduced feeding efficiency, and mortality. MPs are of particular concern because they can be transferred through the food web [23] and have been detected in a wide range of marine species, including zooplankton [61], bivalves [62,63], crustaceans [64], corals [65], fishes [66], and seabirds [67,68] from various global regions. These findings suggest that MPs can bioaccumulate and potentially reach higher trophic levels, including marine mammals [69] and humans [54]. Furthermore, microplastics can act as vectors for persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals, which may accumulate in marine organisms and alter ecosystem functions [24]. Although the toxicological impacts of micro- and nanoplastics are not yet fully understood, experimental studies have shown that ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption are major exposure routes, leading to oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA damage, and disruptions in multiple organ systems [14].

4.2. Shape Patterns

Plastic shape analysis reveals the degree of fragmentation and potential sources. Among MPs, EPS (40.39%) and fragments (37.17%) were dominant, followed by film, pellets, lines, and foam. These patterns reflect the sources of pollution in each location and are influenced by varying types of human activities [27]. These results are consistent with a study in Batan Bay, Indonesia, where EPS reached up to 30.4% [70]. They also align with observations from other areas where marine aquaculture predominantly uses Styrofoam-based flotation systems [60]. In that study, EPS accounted for 94.8% of all large MPs, with fragments making up 2.6% and pellets comprising 1.9% [60].

In this study, fragments were the second most common microplastic type and hard plastic type in mesoplastics. This aligns with findings from Cox’s Bazar, where fragments and foams made up 79% of MPs [45]. Similarly, a study on Saint Martin Island reported fragments as the most prevalent MP type, followed by EPSs, filaments, fishing lines, and foam [71].

In Asia, the proportion of EPS varied between 1.4% and 98.7%, with the highest levels recorded on several beaches in South Korea [72]. In regions outside Asia, EPS proportions on beaches showed a broader range (0.6–52.7%), with the greatest variation observed in the Indian Ocean sub-region, where values ranged from 1.3% to 50.9% [73].

Foams originated from broken fragments or pieces of Styrofoam [74] or from sponge and foam float materials [75]. Fragments are pieces of plastic products with rigid polymers, such as beverage bottles and other hard plastics. Pellets are manufactured as raw materials for larger plastic products and are generally 2–5 mm in size, with a cylindrical or disk-like shape. Films are thin, flexible fragments made from polymers used in items such as plastic bags and wrapping paper [74]. Fibers come from damaged fishing lines, plastic ropes, and synthetic textiles [75].

Meso- and macroplastics also showed high proportions of foam, hard, and soft plastics, with fishing items being particularly prevalent in macroplastics (44.43%). This pattern suggests that macroplastics act as precursors to meso- and microplastics through mechanical and environmental degradation. The similarity in shape composition across size classes highlights the role of anthropogenic sources such as packaging, ropes, and foam products in plastic pollution.

4.3. Color Patterns

Transparent–white plastics were dominant across MPs (79.22%) and mesoplastics (71.20%), while macroplastics displayed multiple colors due to mixed items. Color variations found in this study were similar to those reported by Hossain et al. [66], who found transparent–white dominant (26–68%). Another study [76] also found white to be the most common color (37%), and similar results were reported for Maheshkhali [39], where transparent–white accounted for 53%. However, Peng’s study [77] recorded color as the most dominant type (58%), and Hossain et al. [37] found that most MPs were colored (57%).

Marine species often mistakenly ingest colored MPs, which can be harmful to their health [10,78,79]. The presence of colored MPs suggests inputs from both synthetic and organic waste, highlighting the need for detailed research to identify their sources [37]. Differences in color distribution across size classes may reflect both source materials and degree of weathering, as larger items often contain mixed polymers and pigments.

4.4. Polymer Types and Pollution Sources

FTIR analysis revealed that PS, PP, and PE were the dominant polymers in MPs, mesoplastics, and macroplastics, collectively accounting for over 90% in each size class. EPSs in MPs and foams in mesoplastics were almost entirely PS. This polymer pattern is consistent with the previous studies [55], which found PS at 58.436%, PE at 18.418%, and PP at 18.801% in the water of Surabaya, Indonesia, and reported PS as the most common polymer in Banten Bay sediments [70]. Other studies also support this trend: PS foam accounted for 92% of plastic in Hong Kong, China [80], 96% in Guandong, China [81], and 75% in Washington, USA [82]. PS was the most abundant (95%) polymer type for L-MPs (Large Microplastics), followed by PP (2.5%) and PE (2.2%) [60].

Other research shows variations, with PP being the most abundant in sediment samples from Saint Martin Island, Bangladesh, followed by PS, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), and HDPE [71]. PET accounted for the largest proportion at all sampling locations, making up 48%, while PS had the lowest percentage at 15%. Another study in Cox’s Bazar [45] confirmed that PP and PE comprised the largest proportions of polymers, accounting for 50% and 20%, respectively. Such variations indicate that polymer accumulation depends on location-specific activities, sampling time, and environmental conditions. Further detailed studies are needed to know more about the main reason.

The various types of plastic polymers found in the surface sediments came from a range of sources, including land-based activities such as urban living, household use, industry, and tourism, as well as sea-based activities such as fishing and shipping. Some particles may also have arrived through atmospheric fallout [83]. These polymers are commonly used in everyday products, packaging materials, single-use plastics (SUP), and textiles, significantly contributing to global plastic pollution [84].

Because of their lightweight nature and smooth surface, PP products are widely used in furniture, automotive parts, ropes, textiles, medical devices, and toys [85,86]. PP and PE together account for over 70% of global plastic production, with the majority being SUPs [87].

PP and PE also enter beach sediments from ocean-based sources, including discarded rigid plastics, bundled fishing nets, and ropes [88]. The potential sources of PP and PE are the most widely used plastic materials for packaging and SUPs all over the world. They are often carelessly discarded and end up in the environment [89], in the surface, water bodies [90], and beach sediments [91,92].

PS is used in everyday items like cups, food containers, toys, home furniture, and building materials, serving a range of purposes including construction, packaging, automotive parts, foam products, and bottles [93,94]. It is also frequently utilized as a packaging material in the fishing industry and various other sectors [95]. Polystyrene MPs may originate from products such as styrofoam, toys, compact disks, toothbrushes, and food containers [96].

The differences in PS composition between large and small MPs are mainly due to how EPS buoys break down. EPS beads readily break off and form large MPs, whereas the creation of smaller MPs occurs more slowly through weathering and degradation processes [60]. The breakdown into smaller pieces requires more time, and the resulting fragments are often smaller than 50 μm, making them difficult to detect or collect using standard laboratory techniques [97]. These tiny fragments are also denser than anticipated, which makes them more challenging to separate in water-based tests.

Additionally, EPS contains high concentrations of flame retardants such as Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) [98,99], which can leak into the environment [100] and be absorbed by marine animals [101]. Due to these issues, the South Korean government has begun replacing EPS buoys, enhancing collection programs, and banning the use of HBCDs in such products [60]. More research is needed to fully understand EPS impacts on beach ecosystems.

4.5. Spatial Distribution and Hotspots

IDW observations align with previous research showing that MPs tend to accumulate in river estuaries and coastal beaches, likely transported by river flow to the shore and deposited by waves and ocean currents [19,102,103]. This study identified that 27% of the PE MPs were films, originating from soft plastics such as PE bags, food packaging, and similar materials. This is consistent with another study in the Maheshkhali Channel, which reported that film or sheet plastics made up the majority, accounting for approximately 84% [39]. Another study conducted in the salt pans of the Maheshkhali Channel found that 17% of the samples were PE, with 22% of the MPs categorized as film shapes [76]. This suggests that the Maheshkhali Channel is also being impacted by other anthropogenic factors contributing to plastic pollution. The current findings appear to agree with other research indicating that rivers are the primary source of microplastic contamination in estuaries and nearby areas [80,104,105,106].

Boucher & Friot reported that 98% of MPs found in water bodies originate from onshore activities [107]. Microplastic concentrations showed a positive correlation with population density in Chesapeake Bay [108]. PS dominated over other polymer types, likely because the MPs in the study area primarily originate from the breakdown of large waste generated by the community (secondary microplastics) [55].

Multiple regression analyses revealed that the abundance of large plastics was significantly linked to the population within a 30 km radius, indicating a connection to land-based sources [60]. This result is like those reported in other studies [108,109]. Tourism, urban drainage, and fishing activities are likely the primary sources of MPs in the study area [37]. PS polymers, which serve as raw materials for consumer plastic products, may enter water bodies through industrial effluent discharge [110].

In other studies on the sediments of several beaches in Tamil Nadu, India, similar findings were reported, identifying recreational, religious, and fishing activities as major contributors to microplastic abundance [42,111]. Higher levels of MPs were observed at Juhu Beach, a popular tourist destination in Mumbai, India, where elevated levels in sediments were linked to widespread littering and extensive plastic use in developing countries [58]. City discharges, industrial effluents, fishing activity, and tourism have also been identified as major anthropogenic sources of MPs in beach sediments along the German Baltic [112].

4.6. Tourism and Anthropogenic Impacts

Spatial variation in microplastic abundance was strongly linked to human activities. Rahman et al. [45] reported similar findings at Cox’s Bazar beach, dividing the area into two zones: tourist activity zones and non-tourist activity zones. Their T-test results showed that the occurrence and accumulation of MPs vary based on the level of tourist activity, and a significantly higher number of MPs were found in between zones.

However, in the present study, stations S16 (Shamlapur) and S22 (Sabrang), despite being busy fishing hubs with visible macroplastic debris, showed comparatively low MP abundance. This discrepancy may be attributed to site-specific factors such as the absence of a well-defined strandline during sampling and the influence of previous high tides. At Sabrang, the narrow beach and frequent tidal inundation further limited strandline or vegetation line formation, reducing MP accumulation and potentially influencing the statistical comparison between Active and Less Active zones.

This study was based on a single sampling campaign in October. Therefore, temporal and seasonal variations in microplastic deposition could not be captured. Future studies should include multiple campaigns across pre- and post-monsoon seasons, tourism periods, and time-series data to better understand the dynamics of plastic pollution in this region.

The spatial variation in plastic abundance, especially in tourist zones, highlights the influence of tourism and inadequate urban waste management. Although Bangladesh has adopted a National Plastic Action Plan, effective implementation requires local alignment with waste volume, capacity, and community conditions. Establishing proper waste collection and sorting and nearby MRF centers in urban areas could enhance recycling efficiency and reduce coastal plastic leakage.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first integrated assessment of macro-, meso-, and microplastics pollution along Cox’s Bazar beach, southeastern Bangladesh, highlighting critical pollution hotspots associated with human activities. Tourism Zones had the highest levels of plastic accumulation, suggesting that wastes generated by tourists, coupled with inadequate waste collection, may be the primary contributors to plastic pollution in coastal areas. The dominance of expanded polystyrene and fragmented plastics composed of polystyrene, polypropylene, and polyethylene polymers emphasizes the extensive influence of packaging materials, fishing gear, and single-use plastic products in the marine environment.

The spatial analysis demonstrated that microplastic abundance correlates strongly with population density and tourism intensity, confirming the role of human behavior and infrastructure inefficiency in exacerbating plastic pollution. These findings emphasize the urgent need for an integrated management approach that combines integrated waste management systems and education programs aimed at minimizing single-use plastics. Furthermore, adopting system innovation frameworks could accelerate the transition toward a circular and sustainable plastic economy through the interaction of technological, institutional, and societal changes [113].

Local communities should adopt source segregation, beach clean-ups, and awareness campaigns, while municipal authorities can improve recycling infrastructure, establish MRF centers, and align local policies with national plastic action plans. The scientific community should focus on longitudinal monitoring, mass-based quantification, and assessing the ecological and health impacts of coastal plastics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and H.Y.; methodology, K.A., H.Y., and T.M.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, K.A., H.Y., and T.M.; supervision, H.Y. and T.M.; project administration, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Bangladesh Oceanographic Research Institute (BORI) for granting access to the Environmental Oceanography and Climate Division laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflection |

| BORI | Bangladesh Oceanographic Research Institute |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene |

| EVA | Ethylene Vinyl Acetate |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HBCD | Hexabromocyclododecane |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| IDW | Inverse Distance Weighted |

| MP | Microplastic |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| PBT | Polybutylene Terephthalate |

| PDAP | Poly Diallyl Phthalate |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PMP | Poly Methyl Pentene |

| POM | Polyoxymethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PVC | Poly Vinyl Chloride |

| SEB | Styrene Ethylene Butylene |

| SUP | Single-Use Plastic |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Comparative summary of polymer composition across different plastic size classes (micro-, meso-, and macroplastics) collected from Cox’s Bazar beach. The table highlights clear variations in polymer dominance across size groups, indicating that PP, PE, and PS consistently represent the main polymers, while EVA remains a minor constituent.

Table A1.

Comparative summary of polymer composition across different plastic size classes (micro-, meso-, and macroplastics) collected from Cox’s Bazar beach. The table highlights clear variations in polymer dominance across size groups, indicating that PP, PE, and PS consistently represent the main polymers, while EVA remains a minor constituent.

| Polymer Type | Microplastics (n = 9270) | Mesoplastics (n = 1345) | Macroplastics (n = 701) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | 28.30% | 28.80% | 50.93% | PP dominant in macroplastics; common in all sizes |

| PE | 25.91% | 22.99% | 24.54% | PE relatively stable across all classes |

| PS | 40.85% | 37.82% | 12.07% | PS dominates micro- and mesoplastics |

| EVA | 3.48% | 6.73% | 5.44% | Minor polymer, increases in larger debris |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Summary of plastic particle abundance (micro-, meso-, macro-) across zones at Cox’s Bazar beach. This table presents total particle counts, mean, SD, and range across stations for each zone, illustrating the variation in plastic pollution relative to human activity.

Table A2.

Summary of plastic particle abundance (micro-, meso-, macro-) across zones at Cox’s Bazar beach. This table presents total particle counts, mean, SD, and range across stations for each zone, illustrating the variation in plastic pollution relative to human activity.

| Zone | Size Category | Total Particles | Mean | SD | Range | Stations Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourist | Micro | 8361 | 836.1 | 804.05 | 6–2352 | S4–S13 |

| Meso | 1075 | 107.5 | 129.29 | 2–386 | ||

| Macro | 432 | 43.2 | 48.05 | 6–163 | ||

| Active | Micro | 385 | 77.0 | 86.15 | 5–220 | S1–S3, S16, S22 |

| Meso | 132 | 26.4 | 17.40 | 3–46 | ||

| Macro | 154 | 30.8 | 29.39 | 6–80 | ||

| Less Active | Micro | 662 | 82.75 | 80.93 | 7–236 | S14, S15, S17–S21, S23 |

| Meso | 189 | 23.63 | 19.57 | 2–48 | ||

| Macro | 168 | 21.00 | 11.63 | 9–44 |

References

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Rathod, T.D.; Ajmal, P.Y.; Bhangare, R.C.; Sahu, S.K. Distribution and Characterization of Microplastics in Beach Sand from Three Different Indian Coastal Environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 140, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperagkas, O.; Papageorgiou, N.; Karakassis, I. Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Microplastics in Three Sandy Mediterranean Beaches, Including Different Methodological Approaches. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 219, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Samborska, V.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- PlacticsEurope. Plastics—The Facts 2019: An Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data; PlasticsEurope: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.C.; Tse, H.F.; Fok, L. Plastic Waste in the Marine Environment: A Review of Sources, Occurrence and Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Hardesty, B.D.; van Franeker, J.A.; Eriksen, M.; Siegel, D.; Galgani, F.; Law, K.L. A Global Inventory of Small Floating Plastic Debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A. The Macro-Debris Pollution in the Shorelines of Lake Tana: First Report on Abundance, Assessment, Constituents, and Potential Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 149235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cózar, A.; Echevarría, F.; González-Gordillo, J.I.; Irigoien, X.; Úbeda, B.; Hernández-León, S.; Palma, Á.T.; Navarro, S.; García-de-Lomas, J.; Ruiz, A.; et al. Plastic Debris in the Open Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10239–10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, H.S.; Emenike, C.U.; Fauziah, S.H. Distribution and Importance of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Review of the Sources, Fate, Effects, and Potential Solutions. Environ. Int. 2017, 102, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrano, D.M.; Wick, P.; Nowack, B. Placing Nanoplastics in the Context of Global Plastic Pollution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkham, S.; Faikhaw, O.; Munkong, N.; Sakunkoo, P.; Arunlertaree, C.; Chavali, M.; Mousazadeh, M.; Tiwari, A. A Review on Microplastics and Nanoplastics in the Environment: Their Occurrence, Exposure Routes, Toxic Studies, and Potential Effects on Human Health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 181, 113832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.W.; Hooker, S.K. Ingestion of Plastic and Unusual Prey by a Juvenile Harbour Porpoise. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugoni, L.; Krause, L.; Virgínia Petry, M. Marine Debris and Human Impacts on Sea Turtles in Southern Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001, 42, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derraik, J.G.B. The Pollution of the Marine Environment by Plastic Debris: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidyasakar, A.; Neelavannan, K.; Krishnakumar, S.; Prabaharan, G.; Sathiyabama Alias Priyanka, T.; Magesh, N.S.; Godson, P.S.; Srinivasalu, S. Macrodebris and Microplastic Distribution in the Beaches of Rameswaram Coral Island, Gulf of Mannar, Southeast Coast of India: A First Report. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-S.; Chae, D.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Choi, S.; Woo, S.-B. Factors Influencing the Spatial Variation of Microplastics on High-Tidal Coastal Beaches in Korea. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 69, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.M.; Ulla, M.A.; Rabuffetti, A.P.; Garello, N. Plastic Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems: Macro-, Meso-, and Microplastic Debris in a Floodplain Lake. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.E.; Bamford, H.A. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris. In National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R-30; University of Washington Tacoma: Tacoma, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as Contaminants in the Marine Environment: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivar do Sul, J.A.; Costa, M.F. The Present and Future of Microplastic Pollution in the Marine Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, P.; Manna, C.; Jain, M. Abundance, Interaction, Ingestion, Ecological Concerns, and Mitigation Policies of Microplastic Pollution in Riverine Ecosystem: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhiret Gela, S.; Aragaw, T.A. Abundance and Characterization of Microplastics in Main Urban Ditches Across the Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 831417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Aragaw, T.A.; Balasaraswathi Subramanian, R. Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent and Microfiber Pollution: Focus on Industry-Specific Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 51211–51233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahian, S.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Haider, S.M.B.; Kumar, R.; Walker, T.R.; Khandaker, M.U.; Idris, A.M. Baseline Marine Litter Abundance and Distribution on Saint Martin Island, Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 183, 114091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) as a Source of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Hasan, S.; Rana, M.S.; Sharmin, N. A Conceptual Framework for Zero Waste Management in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Li, Y.; Rob, M.M.; Cheng, H. Microplastic Pollution in Bangladesh: Research and Management Needs. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matter, A.; Ahsan, M.; Marbach, M.; Zurbrügg, C. Impacts of Policy and Market Incentives for Solid Waste Recycling in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Waste Manag. 2015, 39, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.A.; Mohonta, S.K. Plastic Pollution in Bangladesh: A Review on Current Status Emphasizing the Impacts on Environment and Public Health. Environ. Eng. Res. 2021, 26, 200535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshijima, S.; Nishat, B.; Yi, E.J.A.; Kumar, M.; Montoya, D.P.; Hayashi, S. Towards a Multisectoral Action Plan for Sustainable Plastic Management in Bangladesh; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adyel, T.M.; Macreadie, P.I. Plastics in Blue Carbon Ecosystems: A Call for Global Cooperation on Climate Change Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e2–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Sinha, R.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Padha, S.; Ivy, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dhar, A.; Sharma, P. Microplastics Pollution Load in Sundarban Delta of Bay of Bengal. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, M.R.J.; Ertaş, A.; Walker, T.R.; Rule, M.J.; Khandaker, M.U.; Idris, A.M. Macro Marine Litter Survey of Sandy Beaches along the Cox’s Bazar Coast of Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh: Land-Based Sources of Solid Litter Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Banik, P.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Rahman, T. Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in Sediments from the World’s Longest Natural Beach, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 163, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, H.M.Z.; Hasna Hossain, Q.; Kamei, A.; Araoka, D. Compositional Variations, Chemical Weathering, and Provenance of Sands from the Cox’s Bazar and Kuakata Beach Areas, Bangladesh. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahian, S.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Kumar, R.; Haider, S.M.B.; Sharma, P.; Idris, A.M. Distribution, Characteristics, and Risk Assessments Analysis of Microplastics in Shore Sediments and Surface Water of Moheshkhali Channel of Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Zaib, A.; Rehman, S.A.U.; Riaz, N.; Eliw, M.; Hayat, F.; Li, H.; Wang, F. Effects of Micro(Nano)Plastics on Soil Nutrient Cycling: State of the Knowledge. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zaib, A.; Yang, W.; Li, Q. The Impacts of Microplastics and Biofilms Mediated Interactions on Sedimentary Nitrogen Cycling: A Comprehensive Review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, N.; Jeyasanta, K.I.; Patterson, J. Abundance, Characteristics and Surface Degradation Features of Microplastics in Beach Sediments of Five Coastal Areas in Tamil Nadu, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasingam, S.; Mugilarasan, M.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Vethamony, P. Influence of 2015 Flood on the Distribution and Occurrence of Microplastic Pellets along the Chennai Coast, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 109, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharana, D.; Saha, M.; Dar, J.Y.; Rathore, C.; Sreepada, R.A.; Xu, X.-R.; Koongolla, J.B.; Li, H.-X. Assessment of Micro and Macroplastics along the West Coast of India: Abundance, Distribution, Polymer Type and Toxicity. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.A.; Robin, G.S.; Momotaj, M.; Uddin, J.; Siddique, M.A.M. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Microplastics in Beach Sediments of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajwar, M.; Gazi, M.Y.; Saha, S.K. Characterization and Spatial Abundance of Microplastics in the Coastal Regions of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: An Integration of Field, Laboratory, and GIS Techniques. Soil. Sediment. Contam. Int. J. 2022, 31, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajwar, M.; Shreya, S.S.; Gazi, M.Y.; Hasan, M.; Saha, S.K. Microplastic Contamination in the Sediments of the Saint Martin’s Island, Bangladesh. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 53, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monthly Maximum Temperature. Available online: https://live8.bmd.gov.bd/p/Monthly-Maximum-Temperature (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Monthly Minimum Temperature. Available online: https://live6.bmd.gov.bd/p/Monthly-Minimum-Temperature (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Normal Monthly Rainfall. Available online: https://live8.bmd.gov.bd//p/Normal-Monthly-Rainfall (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Rakib, M.R.J.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Pizarro-Ortega, C.I.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C.; Al-Nahian, S. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Pollution Driven by the COVID-19 Pandemic in Cox’s Bazar, the Longest Natural Beach in the World. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Alam, M.M.; Curray, J.R.; Chowdhury, M.L.R.; Gani, M.R. An Overview of the Sedimentary Geology of the Bengal Basin in Relation to the Regional Tectonic Framework and Basin-Fill History. Sediment. Geol. 2003, 155, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments; SIAS Faculty Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.B.; Quinn, B. Microplastic Pollutants, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-0-12-809406-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, M.R.; Purwiyanto, A.I.S.; Suteja, Y. Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in the Northern Coastal Waters of Surabaya, Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, M.Z.A.A.; Saufi, A.S.; Kamarulzaman, N.A.F.; Abidin, M.N.Z.; Osman, M.S. Spatial Distribution of Microplastics Abundance Along Selected Beaches in Kelantan, Malaysia. Sci. Res. J. 2025, 22, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, E.A.; Werorilangi, S.; Galloway, T.S.; Tahir, A. Distribution and Seasonal Variation of Microplastics in Tallo River, Makassar, Eastern Indonesia. Toxics 2021, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasiri, H.B.; Purushothaman, C.S.; Vennila, A. Quantitative Analysis of Plastic Debris on Recreational Beaches in Mumbai, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Ramirez, M.M.; Dzul Caamal, R.; Rendón von Osten, J. Occurrence and Seasonal Distribution of Microplastics and Phthalates in Sediments from the Urban Channel of the Ria and Coast of Campeche, Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eo, S.; Hong, S.H.; Song, Y.K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Shim, W.J. Abundance, Composition, and Distribution of Microplastics Larger than 20 μm in Sand Beaches of South Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botterell, Z.L.R.; Beaumont, N.; Dorrington, T.; Steinke, M.; Thompson, R.C.; Lindeque, P.K. Bioavailability and Effects of Microplastics on Marine Zooplankton: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lusher, A.L.; Rotchell, J.M.; Deudero, S.; Turra, A.; Bråte, I.L.N.; Sun, C.; Shahadat Hossain, M.; Li, Q.; Kolandhasamy, P.; et al. Using Mussel as a Global Bioindicator of Coastal Microplastic Pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Shim, W.J.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Hong, S.H. Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in Market Bivalves from South Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devriese, L.I.; van der Meulen, M.D.; Maes, T.; Bekaert, K.; Paul-Pont, I.; Frère, L.; Robbens, J.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastic Contamination in Brown Shrimp (Crangon Crangon, Linnaeus 1758) from Coastal Waters of the Southern North Sea and Channel Area. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 98, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, N.M.; Berry, K.L.E.; Rintoul, L.; Hoogenboom, M.O. Microplastic Ingestion by Scleractinian Corals. Mar. Biol. 2015, 162, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Sobhan, F.; Uddin, M.N.; Sharifuzzaman, S.M.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.N. Microplastics in Fishes from the Northern Bay of Bengal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, D. Microscopic Anthropogenic Litter in Terrestrial Birds from Shanghai, China: Not Only Plastics but Also Natural Fibers. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amélineau, F.; Bonnet, D.; Heitz, O.; Mortreux, V.; Harding, A.M.A.; Karnovsky, N.; Walkusz, W.; Fort, J.; Grémillet, D. Microplastic Pollution in the Greenland Sea: Background Levels and Selective Contamination of Planktivorous Diving Seabirds. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deudero, S.; Alomar, C. Mediterranean Marine Biodiversity under Threat: Reviewing Influence of Marine Litter on Species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 98, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahudin, D.; Cordova, M.R.; Sun, X.; Yogaswara, D.; Wulandari, I.; Hindarti, D.; Arifin, Z. The First Occurrence, Spatial Distribution and Characteristics of Microplastic Particles in Sediments from Banten Bay, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahian, S.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Haider, S.M.B.; Kumar, R.; Mohsen, M.; Sharma, P.; Khandaker, M.U. Occurrence, Spatial Distribution, and Risk Assessment of Microplastics in Surface Water and Sediments of Saint Martin Island in the Bay of Bengal. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 179, 113720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.S.; Jang, Y.C.; Hong, S.Y.; Shim, W.J.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Kang, D.; et al. Distribution and Size Relationships of Plastic Marine Debris on Beaches in South Korea. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 69, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.S.; Not, C. Variations in the Spatial Distribution of Expanded Polystyrene Marine Debris: Are Asian’s Coastlines More Affected? Environ. Adv. 2023, 11, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takada, H. Microplastic Fragments and Microbeads in Digestive Tracts of Planktivorous Fish from Urban Coastal Waters. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Fu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Dai, Z.; Li, Y.; Tu, C.; Luo, Y. The Distribution and Morphology of Microplastics in Coastal Soils Adjacent to the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea. Geoderma 2018, 322, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, M.R.J.; Al Nahian, S.; Alfonso, M.B.; Khandaker, M.U.; Enyoh, C.E.; Hamid, F.S.; Alsubaie, A.; Almalki, A.S.A.; Bradley, D.A.; Mohafez, H.; et al. Microplastics Pollution in Salt Pans from the Maheshkhali Channel, Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Zhu, B.; Yang, D.; Su, L.; Shi, H.; Li, D. Microplastics in Sediments of the Changjiang Estuary, China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, Z.; Peng, J.; Qiu, Q.; Li, M. The Behaviors of Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 113, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, L.; Cheung, P.K. Hong Kong at the Pearl River Estuary: A Hotspot of Microplastic Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 99, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, L.; Cheung, P.K.; Tang, G.; Li, W.C. Size Distribution of Stranded Small Plastic Debris on the Coast of Guangdong, South China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.; Murphy, A.G. Plastic in Surface Waters of the Inside Passage and Beaches of the Salish Sea in Washington State. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 97, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasingam, S.; Ranjani, M.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Bagaev, A.; Mukhanov, V.; Litvinyuk, D.; Verzhevskaia, L.; Guganathan, L.; Vethamony, P. Microplastics in Different Environmental Compartments in India: Analytical Methods, Distribution, Associated Contaminants and Research Needs. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 133, 116071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Verla, A.W.; Verla, E.N.; Ibe, F.C.; Amaobi, C.E. Airborne Microplastics: A Review Study on Method for Analysis, Occurrence, Movement and Risks. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchaiyappan, A.; Ahmed, S.Z.; Dowarah, K.; Jayakumar, S.; Devipriya, S.P. Occurrence, Distribution and Composition of Microplastics in the Sediments of South Andaman Beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D. Practical Guide to Polypropylene; Smithers Rapra Publishing: Shropshire, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-85957-282-5. [Google Scholar]

- Erni-Cassola, G.; Zadjelovic, V.; Gibson, M.I.; Christie-Oleza, J.A. Distribution of Plastic Polymer Types in the Marine Environment; A Meta-Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; van der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.-W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River Plastic Emissions to the World’s Oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Int-Veen, I.; Löder, M.G.J.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Identification of Microplastic in Effluents of Waste Water Treatment Plants Using Focal Plane Array-Based Micro-Fourier-Transform Infrared Imaging. Water Res. 2017, 108, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Lv, J.; Xiong, X.; Wu, C. Accumulation of Floating Microplastics behind the Three Gorges Dam. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 204, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in Freshwater and Terrestrial Environments: Evaluating the Current Understanding to Identify the Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, T.; Van der Meulen, M.D.; Devriese, L.I.; Leslie, H.A.; Huvet, A.; Frère, L.; Robbens, J.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastics Baseline Surveys at the Water Surface and in Sediments of the North-East Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigós, M.C.; Marín, M.L.; Cantó, A.; Sánchez, A. Determination of Residual Styrene Monomer in Polystyrene Granules by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1061, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halland, G.R. Uptake and Excretion of Polystyrene Microplastics in the Marine Copepod Calanus Finmarchicus. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjani, M.; Veerasingam, S.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Jinoj, T.P.S.; Guganathan, L.; Mugilarasan, M.; Vethamony, P. Seasonal Variation, Polymer Hazard Risk and Controlling Factors of Microplastics in Beach Sediments along the Southeast Coast of India. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, K.; Bukowska, B.; Sicińska, P. Polystyrene Nanoparticles: Sources, Occurrence in the Environment, Distribution in Tissues, Accumulation and Toxicity to Various Organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Jung, S.W.; Shim, W.J. Combined Effects of UV Exposure Duration and Mechanical Abrasion on Microplastic Fragmentation by Polymer Type. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4368–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Shim, W.J.; Han, G.M.; Rani, M.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H. Widespread Detection of a Brominated Flame Retardant, Hexabromocyclododecane, in Expanded Polystyrene Marine Debris and Microplastics from South Korea and the Asia-Pacific Coastal Region. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shim, W.J.; Han, G.M.; Jang, M.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H. Hexabromocyclododecane in Polystyrene Based Consumer Products: An Evidence of Unregulated Use. Chemosphere 2014, 110, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shim, W.J.; Han, G.M.; Jang, M.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H. Benzotriazole-Type Ultraviolet Stabilizers and Antioxidants in Plastic Marine Debris and Their New Products. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Shim, W.J.; Han, G.M.; Rani, M.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H. Styrofoam Debris as a Source of Hazardous Additives for Marine Organisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4951–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissen, R.; Chawchai, S. Microplastics on Beaches along the Eastern Gulf of Thailand—A Preliminary Study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, G.Z.; Shotorban, A.K.; Hatcher, P.G.; Waggoner, D.C.; Ghosal, S.; Noffke, N. Microplastic Fragment and Fiber Contamination of Beach Sediments from Selected Sites in Virginia and North Carolina, USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanale, C.; Stock, F.; Massarelli, C.; Kochleus, C.; Bagnuolo, G.; Reifferscheid, G.; Uricchio, V.F. Microplastics and Their Possible Sources: The Example of Ofanto River in Southeast Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Sánchez, L.; Grelaud, M.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Ziveri, P. River Deltas as Hotspots of Microplastic Accumulation: The Case Study of the Ebro River (NW Mediterranean). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Li, D. Analysis of Suspended Microplastics in the Changjiang Estuary: Implications for Riverine Plastic Load to the Ocean. Water Res. 2019, 161, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, J.; Friot, D. Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2017; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Yonkos, L.T.; Friedel, E.A.; Perez-Reyes, A.C.; Ghosal, S.; Arthur, C.D. Microplastics in Four Estuarine Rivers in the Chesapeake Bay, U.S.A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14195–14202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, F.; Chen, H.; Quan, G.; Yan, J.; Li, T.; et al. Environmental Occurrences, Fate, and Impacts of Microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]