Is It Worth It? Potential for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Bitumen Roofing Membrane Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

Goal and Scope

2. Methodology

2.1. Impact Categories

2.2. Database

2.3. Overview

2.4. Pearson Correlation Coefficients

2.5. Statistical Significance Testing

2.6. Regression Analysis

- Bitumen mass ratio vs. limestone mass ratio;

- Bitumen mass ratio vs. indicator;

- Limestone mass ratio vs. indicator.

2.7. Calculation Software

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Welch Test

3.3. Pearson Correlation Coefficients

3.4. Regression Analysis

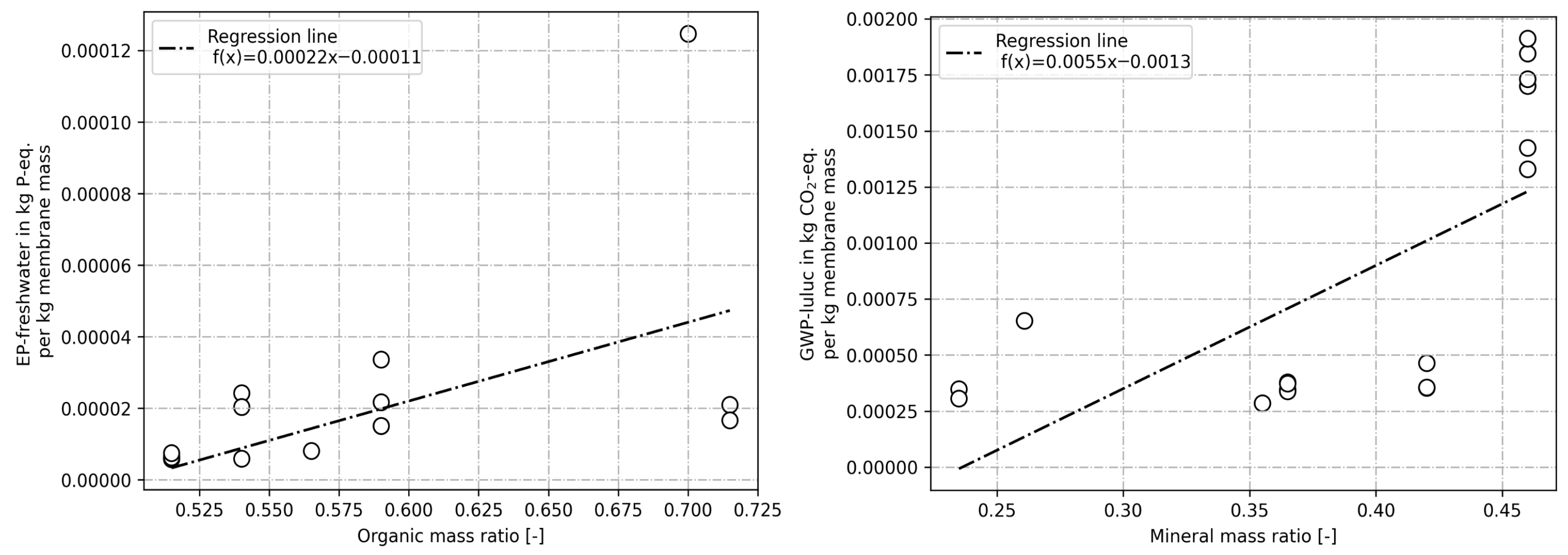

3.4.1. Prediction by Organic Mass

3.4.2. Prediction by Mineral Mass

3.4.3. Multiple Regression Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Predicting Carrier Material

4.2. Correlation Matrix

4.3. Regression Models

4.4. Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPE | Abiotic Depletion Potential of Elements |

| ADPF | Abiotic Depletion Potential of Fossils |

| AP | Acidification Potential |

| DGNB | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen |

| EP | Eutrophication Potential |

| EWA | European Waterproofing Association |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| LULUC | Land-Use and Land-Use Change |

| NMVOC | Non-Methane Volatile Organic Compounds |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| PENRT | Primary Energy Non-Renewable, Total |

| PERT | Primary Energy Renewable, Total |

| POCP | Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| WDP | Water Depletion Potential |

Appendix A. Materials & Results

Used Datasets

| Source | Product | Carrier | Density [] | Thickness [mm] | Organic Ratio | Mineral Ratio | Year Ref. | Geography | Database |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasse | Yearly production | Glasfiber, Polyester fleece, Aluminium | 5.1 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 0.26 [7] | 2021 | DE | Ecoinvent 3.9 |

| Ökobaudat | G200 S4 | Glas fiber | 5.0 | 4.0 | - | - | 2018 | DE | GaBi |

| PYE PV200 S4 | Polyester fleece | 5.21 | 4.0 | - | - | 2018 | DE | GaBi | |

| PYE PV200 S4 ns | Polyester fleece | 6.20 | 4.0 | - | - | 2023 | DE | GaBi | |

| V60 | Glas fleece | 5.0 | 4.0 [4] | - | - | 2023 | DE | GaBi | |

| Ecoinvent | Alu80 | Aluminium | 1.9 [2] | 1.5 [2] | 0.66 | 0.26 | 2007 | RER [1] | Ecoinvent 3.10 |

| EP4 | Polyester fleece | 4.7 [2] | 4.00 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 2007 | RER [1] | Ecoinvent 3.10 | |

| PYE PV200 S5 | Glas fiber | 6.02 [2] | 5.00 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 2007 | RER [1] | Ecoinvent 3.10 | |

| V60 S4 | Glas fleece | 5.76 [2] | 4.00 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 2007 | RER [1] | Ecoinvent 3.10 | |

| VA4 | Glas fleece / Aluminium | 5.33 [2] | 4.00 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 2007 | RER [1] | Ecoinvent 3.10 | |

| Phønix Tag Materialer | AeroTæt PF2000 | Polyester fleece | 2.24 | 2.10 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 2021 | DK | GaBi 10.6.1.35 |

| Aero Tæt PF3200 | Polyester fleece | 3.39 | 2.90 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 2021 | DK | GaBi 9.2.1.68, Ecoinvent 3.6, Eurobitume LCI 2019 | |

| BituFlex PF5000 SBS | Polyester fleece | 5.00 | 4.30 | 0.59 | 0.365 | 2021 | DK | ||

| BituFlex Kombi PF/GF5000 SBS | Polyester fleece / Glas fleece | 5.30 | 4.40 | 0.59 | 0.365 | 2021 | DK | ||

| DuraFlex PF3500 SBS | Polyester fleece | 3.30 | 2.90 | 0.59 | 0.365 | 2021 | DK | ||

| DuraFlex Kombi PF/GF3500 SBS | Polyester fleece / Glas fleece | 3.30 | 2.90 | 0.59 | 0.365 | 2021 | DK | ||

| Topmembran PF4600 SBS | Polyester fleece | 5.00 | 4.70 | 0.715 | 0.235 | 2021 | DK | ||

| Flammespærre GF3000 | Glas felt | 2.54 | 2.00 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 2021 | DK | ||

| Bundmembran PF4500 SBS | Polyester fleece | 5.10 | 4.70 | 0.715 | 0.235 | 2021 | DK | ||

| European Waterproofing Association | Benchmark [6] | Polyester and glas fleece | 5.30 | 4.30 | 0.565 | 0.355 | 2019 | BE BY DK FI FR DE IT LT NL NO PT RU ES SE | SimaPro 9, Ecoinvent 3.6, Plastics Europe 2014 |

| Danosa [3, 5] | System NTV2/EXT1 | Polyester fleece, Glas fiber | 8.64 | 5.0 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 |

| System TPP1/NTG1 | Polyester fleece, Glas fiber | 7.96 | 5.8 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 | |

| System TVA1/TVH1/TPC1/TPC2 | Polyester felt/Glas fiber | 9.04 | 6.15 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 | |

| ESTERDAN PLUS 50/GP ELAST | Polyester fleece | 6.0 | 3.5 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 | |

| POLYDAN PLUS FM 50/GP ELAST | Polyester felt/Glas fiber | 5.6 | 3.5 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 | |

| System NTV6 | Polyester fleece | 7.84 | 5.0 | 0.515 | 0.46 | 2021 | ES | Ecoinvent 3.8, SimaPro 9.3 |

| Quelle | Product Name | ADPE | ADPF | AP | EP-Freshwater | EP-Marine | EP-Terrestrial | GWP-Biogenic | GWP-Fossil | GWP-Luluc | GWP-Total | ODP | POCP | PENRT | PERT | WDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg Sb eq.] | [MJ] | [Mole H+ eq.] | [kg P eq.] | [kg N eq.] | [Mole N eq.] | [kg CO2 eq.] | [kg CO2 eq.] | [kg CO2 eq.] | [kg CO2 eq.] | [kg CFC-11 eq.] | [kg NMVOC eq.] | [MJ] | [MJ] | [m3] | ||

| Hasse | Jahresproduktion | 3.68 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 102 | 2.25 × 10−2 | 6.36 × 10−4 | 4.60 × 10−3 | 4.07 × 10−2 | 1.41 × 10−2 | 5.19 | 3.33 × 10−3 | 5.21 | 8.53 × 10−7 | 3.22 × 10−2 | 1.78 × 102 | 3.25 | 1.23 |

| Oekobaudat | G200 S4 | 5.286 × 10−7 | 193.2 | 0.009556 | 0.000004574 | 0.002042 | 0.02229 | 0.03031 | 3.301 | 0.002774 | 3.334 | 1.11 × 10−11 | 0.008925 | 167.6 | 5.694 | 0.09493 |

| Oekobaudat | PYE PV200 S4 | 6.523 × 10−7 | 253.6 | 0.009933 | 0.00001524 | 0.002631 | 0.02835 | 0.0297 | 5.764 | 0.002741 | 5.796 | 2.197 × 10−11 | 0.01356 | 227.2 | 11.07 | 0.1462 |

| Oekobaudat | PYE PV200 S4 ns | 6.539 × 10−7 | 252.9 | 0.01005 | 0.00001526 | 0.002696 | 0.02908 | 0.02915 | 5.765 | 0.003105 | 5.798 | 2.203 × 10−11 | 0.01365 | 252.9 | 11.12 | 0.1485 |

| Oekobaudat | V60 | 5.021 × 10−7 | 188 | 0.008386 | 0.000004493 | 0.001874 | 0.02058 | 0.01533 | 2.889 | 0.002736 | 2.907 | 1.306 × 10−11 | 0.008311 | 188 | 6.235 | 0.06025 |

| Ecoinvent | Alu80 | 2.27 × 10−5 | 87.6 | 0.0222 | 0.00115 | 0.00012 | 0.037 | 0.082 | 3.82 | 0.0078 | 3.83 | 9.24 × 10−7 | 0.021 | 98.4 | 4.7 | 1.00 |

| Ecoinvent | EP4 | 5.88 × 10−5 | 179.1 | 0.0218 | 0.00137 | 0.00020 | 0.037 | 0.201 | 4.92 | 0.0041 | 4.93 | 1.36 × 10−6 | 0.036 | 201.9 | 6.6 | 1.78 |

| Ecoinvent | No Name (PYE PV 200 S5) | 6.28 × 10−5 | 269.2 | 0.0325 | 0.00109 | 0.00026 | 0.057 | 0.383 | 8.56 | 0.0034 | 8.57 | 1.46 × 10−6 | 0.046 | 293.2 | 7.6 | 4.67 |

| Ecoinvent | V60 (S4) | 7.08 × 10−5 | 214.5 | 0.0223 | 0.00127 | 0.00021 | 0.036 | 0.183 | 4.90 | 0.0039 | 4.91 | 1.61 × 10−6 | 0.043 | 240.1 | 6.5 | 1.25 |

| Ecoinvent | VA4 (wie V60 S4 + Al) | 7.11 × 10−5 | 221.0 | 0.0287 | 0.00233 | 0.00031 | 0.048 | 0.395 | 6.11 | 0.0078 | 6.13 | 2.17 × 10−6 | 0.045 | 260.7 | 13.1 | 2.34 |

| PTM | AeroTaet PF2000 (Dampfspaerre) | 3.47 × 10−7 | 6.32 × 101 | 1.45 × 10−3 | 5.42 × 10−5 | 8.10 × 10−4 | 8.74 × 10−3 | 7.98 × 10−3 | 7.40 × 10−1 | 1.04 × 10−3 | 7.49 × 10−1 | 8.92 × 10−9 | 1.26 × 10−3 | 6.64 × 101 | 7.35 | 9.86 × 10−2 |

| PTM | AeroTaet PF3200 (Dampfspaerre) | 3.98 × 10−7 | 1.06 × 102 | 1.71 × 10−3 | 6.90 × 10−5 | 1.19 × 10−3 | 1.29 × 10−2 | 1.33 × 10−2 | 1.00 | 1.20 × 10−3 | 1.01 | 1.08 × 10−8 | 1.50 × 10−3 | 1.12 × 102 | 7.66 | 1.30 × 10−1 |

| PTM | BituFlex PF5000 SBS | 4.98 × 10−7 | 1.56 × 102 | 3.56 × 10−3 | 7.54 × 10−5 | 1.90 × 10−3 | 2.07 × 10−2 | 2.82 × 10−3 | 2.07 | 1.73 × 10−3 | 2.07 | 1.07 × 10−8 | 4.20 × 10−3 | 1.64 × 102 | 9.33 | 3.11 × 10−1 |

| PTM | BituFlex Kombi PF/GF5000 SBS | 5.27 × 10−7 | 1.63 × 102 | 3.82 × 10−3 | 7.98 × 10−5 | 1.98 × 10−3 | 2.15 × 10−2 | 1.09 × 10−2 | 2.13 | 1.80 × 10−3 | 2.14 | 1.15 × 10−8 | 4.24 × 10−3 | 1.70 × 102 | 9.55 | 3.14 × 10−1 |

| PTM | DuraFlex PF3500 SBS | 4.67 × 10−7 | 1.17 × 102 | 2.77 × 10−3 | 7.15 × 10−5 | 1.46 × 10−3 | 1.58 × 10−2 | 7.70 × 10−3 | 1.51 | 1.25 × 10−3 | 1.52 | 1.10 × 10−8 | 3.05 × 10−3 | 1.22 × 102 | 9.04 | 2.32 × 10−1 |

| PTM | DuraFlex Kombi PF/GF3500 SBS | 1.03 × 10−6 | 1.12 × 102 | 3.35 × 10−3 | 1.11 × 10−4 | 1.48 × 10−3 | 1.67 × 10−2 | 1.18 × 10−2 | 1.39 | 1.23 × 10−3 | 1.41 | 3.07 × 10−8 | 2.82 × 10−3 | 1.17 × 102 | 8.67 | 3.54 × 10−1 |

| PTM | Topmembran PF4600 SBS | 6.62 × 10−7 | 2.18 × 102 | 5.31 × 10−3 | 1.05 × 10−4 | 2.65 × 10−3 | 2.89 × 10−2 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 3.16 | 1.74 × 10−3 | 3.19 | 1.61 × 10−8 | 6.72 × 10−3 | 2.28 × 102 | 9.47 | 4.96 × 10−1 |

| PTM | Flammespaerre GF3000 | 1.88 × 10−7 | 6.18 × 101 | 1.68 × 10−3 | 1.49 × 10−5 | 7.58 × 10−4 | 8.20 × 10−3 | −1.51 × 10−2 | 4.79 × 10−1 | 9.04 × 10−4 | 4.65 × 10−1 | 1.45 × 10−12 | 8.00 × 10−4 | 6.53 × 101 | 6.92 | 4.00 × 10−2 |

| PTM | Bundmembran PF4500 SBS | 5.59 × 10−7 | 2.17 × 102 | 4.97 × 10−3 | 8.49 × 10−5 | 2.57 × 10−3 | 2.81 × 10−2 | 2.07 × 10−2 | 2.99 | 1.56 × 10−3 | 3.02 | 1.16 × 10−8 | 6.42 × 10−3 | 2.27 × 102 | 8.98 | 4.67 × 10−1 |

| EWA | Bitumen-Durchschnitt [7] | 3.68 × 10−6 | 6.13 × 101 | 9.17 × 10−3 | 4.27 × 10−5 | 1.42 × 10−3 | 1.58 × 10−2 | −7.98 × 10−2 | 1.28 | 1.51 × 10−3 | 1.20 | 9.76 × 10−7 | 6.44 × 10−3 | 6.30 × 101 | 2.43 | 5.43 |

| Danosa | System NTV2/EXT1 | 1.22 × 10−5 | 2.36 × 102 | 3.35 × 10−2 | 5.03 × 10−5 | 5.88 × 10−3 | 6.46 × 10−2 | 3.45 × 10−3 | 5.67 | 1.47 × 10−2 | 5.69 | 6.53 × 10−7 | 1.86 × 10−2 | 2.53 × 102 | 5.86 | 4.36 |

| Danosa | System TPP1/NTG1 | 1.22 × 10−5 | 2.36 × 102 | 3.35 × 10−2 | 5.03 × 10−5 | 5.88 × 10−3 | 6.46 × 10−2 | 3.45 × 10−3 | 5.67 | 1.47 × 10−2 | 5.69 | 6.53 × 10−7 | 1.86 × 10−2 | 2.53 × 102 | 5.86 | 4.36 |

| Danosa | System TVA1/TVH1/TPC1/TPC2 | 1.57 × 10−5 | 2.66 × 102 | 3.84 × 10−2 | 5.89 × 10−5 | 6.72 × 10−3 | 7.39 × 10−2 | 4.22 × 10−3 | 6.32 | 1.50 × 10−2 | 6.34 | 7.16 × 10−7 | 2.13 × 10−2 | 2.84 × 102 | 6.13 | 4.94 |

| Danosa | ESTERDAN PLUS 50/GP ELAST | 1.04 × 10−5 | 1.39 × 102 | 2.08 × 10−2 | 3.55 × 10−5 | 3.68 × 10−3 | 4.05 × 10−2 | 2.99 × 10−3 | 3.51 | 7.98 × 10−3 | 3.52 | 3.98 × 10−7 | 1.18 × 10−2 | 1.49 × 102 | 3.32 | 2.63 |

| Danosa | POLYDAN PLUS FM 50/GP ELAST | 1.04 × 10−5 | 1.39 × 102 | 2.08 × 10−2 | 3.55 × 10−5 | 3.68 × 10−3 | 4.05 × 10−2 | 2.99 × 10−3 | 3.51 | 7.98 × 10−3 | 3.52 | 3.98 × 10−7 | 1.18 × 10−2 | 1.49 × 102 | 3.32 | 2.63 |

| Danosa | System NTV6 | 1.57 × 10−5 | 2.66 × 102 | 3.84 × 10−2 | 5.89 × 10−5 | 6.72 × 10−3 | 7.39 × 10−2 | 4.22 × 10−3 | 6.32 | 1.50 × 10−2 | 6.34 | 7.16 × 10−7 | 2.13 × 10−2 | 2.84 × 102 | 6.13 | 4.94 |

| ADPE | ADPF | AP | EP | GWP | ODP | POCP | PENRT | PERT | WDP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| freshw. | mar. | terr. | bio. | fos. | luluc | tot. | |||||||||

| ADPE | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| ADPF | −0.13 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| AP | 0.70 *** | −0.17 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| EP-freshwater | 0.79 *** | 0.08 | 0.16 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| EP-marine | 0.76 *** | 0.11 | 0.91 *** | 0.37 * | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| EP-terrestrial | 0.63 *** | 0.09 | 0.91 *** | 0.2 | 0.98 *** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| GWP-biogenic | −0.06 | 0.84 *** | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| GWP-fossil | 0.48 ** | 0.60 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.23 | 0.67 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.47 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| GWP-luluc | 0.38 * | −0.22 | 0.89 *** | −0.18 | 0.78 *** | 0.86 *** | −0.07 | 0.38 * | 1.00 | ||||||

| GWP-total | 0.47 ** | 0.61 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.23 | 0.67 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.49 ** | 1.00 *** | 0.38 * | 1.00 | |||||

| ODP | 0.73 *** | −0.56 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.4 * | 0.54 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.61 *** | 0.19 | 0.45 ** | 0.17 | 1.00 | ||||

| POCP | 0.90 *** | 0.19 | 0.74 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.78 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.13 | 0.79 *** | 0.39 * | 0.79 *** | 0.62 *** | 1.00 | |||

| PENRT | −0.12 | 0.97 *** | −0.15 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.84 *** | 0.53 ** | −0.16 | 0.54 ** | −0.56 *** | 0.14 | 1.00 | ||

| PERT | −0.54 ** | 0.31 | −0.80 *** | 0.017 | −0.60 *** | −0.61 *** | 0.31 | −0.39 * | −0.65 *** | −0.39 * | −0.74 *** | −0.59 *** | 0.33 | 1.00 | |

| WDP | 0.35 | −0.56 *** | 0.66 *** | −0.093 | 0.43 * | 0.47 ** | −0.69 *** | 0.02 | 0.62 *** | 0.01 | 0.85 *** | 0.26 | −0.63 *** | −0.74 *** | 1.00 |

| Estimate | p-Value | R2 (adj.) | F(2,14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPE | Intercept | −0.000062 * | 0.197 | 0.09 | 1.8 |

| Prop. organics | 0.000070 * | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.000060 * | ||||

| ADPF | Intercept | −339.7 *** | <0.000 *** | 0.67 | 17.4 |

| Prop. organics | 425.3 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 325.8 *** | ||||

| AP | Intercept | −0.067 ** | 0.030 ** | 0.31 | 4.6 |

| Prop. organics | 0.072 ** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.073 ** | ||||

| EP-freshwater | Intercept | −0.00058 | 0.042 ** | 0.27 | 4.0 |

| Prop. organics | 0.00073 | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.00046 | ||||

| EP-terrestrial | Intercept | −0.12 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.51 | 9.5 |

| Prop. organics | 0.13 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.12 *** | ||||

| EP-marine | Intercept | −0.012 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.49 | 8.8 |

| Prop. organics | 0.013 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.012 *** | ||||

| GWP-biogenic | Intercept | −0.29 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.56 | 11.3 |

| Prop. organics | 0.33 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.28 *** | ||||

| GWP-fossil | Intercept | −12.9 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.50 | 9.1 |

| Prop. organics | 14.7 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 12.8 *** | ||||

| GWP-luluc | Intercept | −0.026 *** | <0.000 *** | 0.63 | 14.4 |

| Prop. organics | 0.027 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.030 *** | ||||

| GWP-total | Intercept | −13.2 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.52 | 9.7 |

| Prop. organics | 15.1 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 13.1 *** | ||||

| ODP | Intercept | 0.00000078 | 0.795 | 0.11 | 0.23 |

| Prop. organics | −0.00000082 | ||||

| Prop. minerals | −0.00000066 | ||||

| POCP | Intercept | −0.057 * | 0.103 | 0.17 | 2.7 |

| Prop. organics | 0.065 ** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 0.055 * | ||||

| PENRT | Intercept | −360.5 *** | <0.000 *** | 0.63 | 14.8 |

| Prop. organics | 448.5 *** | ||||

| Prop. minerals | 349.3 *** | ||||

| PERT | Intercept | 14.7 | 0.597 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| Prop. organics | −13.2 | ||||

| Prop. minerals | −14.4 | ||||

| WDP | Intercept | 6.9 | 0.160 | 0.12 | 2.1 |

| Prop. organics | −7.8 | ||||

| Prop. minerals | −5.5 |

References

- Schwartz, M.; Hollander, D. Annealing, Distilling, Reheating and Recycling: Bitumen Processing in the Ancient Near East. Paléorient 2000, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, A.; Yitmen, I.; Myhren, J.A.; Almssad, A. Assessing the Impact of Recycled Building Materials on Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: A Comprehensive Framework for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Buildings 2024, 14, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, X. Life cycle assessment of SBS modified bitumen waterproofing membrane. Physics 2023, 2639, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Olsson, J.A.; Miller, S.A. Greenhouse gas emissions of global construction material production. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. J. 2025, 5, 015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckh, S. Ecological Footprint of Bitumen. Diploma Thesis, Technical University, Vienna, Austria, June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The Eurobitume Life Cycle Assessment 4.0 for Bitumen; European Bitumen Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. Available online: https://eurobitume.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/EB-LCA-4.0-2025.pdf? (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- European Commission. From Roof to Road—Innovative Recycling of Bitumen Felt Roofing Material. In Technical Report: LIFE07 ENV/DK/000102; European Commission: Glostrup, Danmark, 2011; Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE07-ENV-DK-000102/from-roof-to-road-innovative-recycling-of-bitumen-felt-roofing-material? (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Marktzahlen 2023—Zahlen im Überblick und Vergleich zum Vorjahr. Available online: https://www.derdichtebau.de/news/marktzahlen-2023/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Drefahl, J. Dach-Report 3/2008; CSI Dachverständige: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesinstitut für Bau-Stadt-Raumforschung (BBSR). Nutzungsdauern von Bauteilen für Lebenszyklusanalysen nach Bewertungssystem Nachhaltiges Bauen; BBSR: Bonn, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.nachhaltigesbauen.de/fileadmin/pdf/Nutzungsdauer_Bauteile/BNB_Nutzungsdauern_von_Bauteilen_2017-02-24.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Umweltbundesamt; Bauabfälle: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/ressourcen-abfall/verwertung-entsorgung-ausgewaehlter-abfallarten/bauabfaelle?# verwertung-von-bau-und-abbruchabfallen (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Hunklinger, R.; Krieger, C. Marktanalyse zur Entsorgung von bituminösen Dachbahnen. Baust.-Recycl. Und Deponietech. 1998. Available online: https://tubiblio.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/13504/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Nordic Waterproofing Holding A/S. Invitation to Acquire Shares in Nordic Waterproofing Holding A/S; Nordic Waterproofing Holding A/S: Helsingborg, Sweden, 2016; Available online: https://www.nordicwaterproofing.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/nwg-prospectus-30may2016-en-1.pdf? (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Rikmann, E.; Mäeorg, U.; Vaino, N.; Pallav, V.; Järvik, O.; Liiv, J. Recycling Bitumen for Composite Material Production: Potential Applications in the Construction Sector. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Allanson, M.; Sreeram, A.; Ryan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Airey, G.D. Characterisation of bitumen through multiple ageing-rejuvenation cycles. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2365350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, V.; Moreno, F.; Rubio-Gámez, M.; Freire, A.C.; Neves, J. Assessing RAP Multi-Recycling Capacity by the Characterization of Recovered Bitumen Using DSR. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contarini, A.; Meijer, A. LCA comparison of roofing materials for flat roofs. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2015, 4, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.; Molleti, S.; Ghobadi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Studies in Roofing Industry: Current Trends and Future Directions. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2781–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Hua, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, L.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Dong, L.; Seng Yap, P. Green construction for low-carbon cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1627–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, A.; Rahimy, O.; Levasseur, A. Environmental life-cycle impacts of bitumen: Systematic review and new Canadian models. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 136, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesinstitut für Bau- Stadt- Raumforschung (BBSR). Bitumen-Dachbahnen. BBSR: Bonn, Germany, 2013. Available online: https://www.wecobis.de/bauproduktgruppen/abdichtungen-pg/abdichtungsbahnen-pg/dachbahn-bitumen-pg.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Zheng, B.; Yang, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Jiang, H.; Bao, Z. A meta-analysis of environmental impacts of building reuse and recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 520, 146149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, A.; Andersen, B.; Klungseth, N.J.; Tadayon, A. Achieving a circular economy through the effective reuse of construction products: A case study of a residential building. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS). Bewertungssystem Nachhaltiges Bauen (BNB) Neubau Laborgebäude; BMVBS: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://www.bnb-nachhaltigesbauen.de/bewertungssystem/laborgebaeude/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- DIN EN ISO 14044:2021-02; Umweltmanagement-Ökobilanz-Anforderungen und Anleitungen. DIN Media Gmbh: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- DIN EN 15804:2022-03; Nachhaltigkeit von Bauwerken-Umweltproduktdeklarationen-Grundregeln für die Produktkategorie Bauprodukte. DIN Media Gmbh: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- Hauschild, M.; Rosenbaum, R. Life Cycle Assessment-Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht, R. Lehrbuch der Ökobilanzierung, 1st ed.; Springer-Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ecoinvent Association. Ecoinvent Version 3.10, Allocation Cut-Off by Classification. 2023. Available online: https://ecoquery.ecoinvent.org/3.10/cutoff (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Deutsche Bundesministerium für Wohnen, Stadtentwicklung und Bauwesen (Ed.) Ökobaudat-Datenbank 2023-I. 2023. Available online: https://www.oekobaudat.de/no_cache/datenbank/suche.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Hasse, C.; Rädecke, E. Bitumenbahnen zur Dach-und Bauwerksabdichtung. 2024. Available online: https://epd-online.com/EmbeddedEpdList/Detail?id=17869 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Phønix Tag Materialer. Produkter. 2025. Available online: https://www.phonixtagmaterialer.dk/produkter/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- European Waterproofing Association (EWA) AISBL. Flexible Bitumen Sheets For Roof Waterproofing-Sector EPD. Belgium. 2023. Available online: https://epd-online.com/EmbeddedEpdList/Detail?id=15748 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- DANOSA—Derivados S.A. Normalized Asfálticos. EPD—Waterproofing Systems with Bituminous Membrane: TPP1/TPC1/TPC2/TVH1/TVA1/NTG1/NTV1/NTV2/NTV5/NTV6/EXT1. Spain. 2023. Available online: https://d7rh5s3nxmpy4.cloudfront.net/CMP1814/files/1/DANOSA-DAP-waterproofing-LBM.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Sedlmeier, P.; Renkewitz, F. Forschungsmethoden und Statistik für Psychologen und Sozialwissenschaftler, 3rd ed.; Pearson Deutschland GmbH: München, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Liebich, A.; Müller, J.; Münter, D.; Wingenbach, C.; Vogt, R. LCAst–Prospektive Ökobilanzen auf Basis der Ecoinvent-Datenbank.ifeu Paper 03/2023. Heidelberg. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifeu.de/publikation/lcast-prospektive-oekobilanzen-auf-basis-der-ecoinvent-datenbank (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zimmerman, D.W. A note on preliminary tests of equality of variances. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2004, 57, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multicollinearity in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemiologic Studies. Epidemiol. Open Access 2016, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Mancini, E. Life cycle assessment and circularity indicators. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.; Weidema, B.P.; Bare, J.; Liao, X.; de Souza, D.M.; Pizzol, M.; Sala, S.; Schreiber, H.; Thonemann, N.; Verones, F. Methodological review and detailed guidance for the life cycle interpretation phase. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Arraiza, A.; Essamari, L.; Iturrondobeitia, M.; Boullosa-Falces, D.; Justel, D. Life cycle assessment of glass fibre versus flax fibre reinforced composite ship hulls. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppannan Gopalraj, S.; Kärki, T. A review on the recycling of waste carbon fibre/glass fibre-reinforced composites: Fibre recovery, properties and life-cycle analysis. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödger, J.M.; Beier, J.; Schönemann, M.; Schulze, C.; Thiede, S.; Bey, N.; Herrmann, C.; Hauschild, M.Z. Combining Life Cycle Assessment and Manufacturing System Simulation: Evaluating Dynamic Impacts from Renewable Energy Supply on Product-Specific Environmental Footprints. Int. J. Precis. Eng.-Manuf.-Green Technol. 2021, 8, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrč Obrecht, T.; Jordan, S.; Legat, A.; Passer, A. The role of electricity mix and production efficiency improvements on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of building components and future refurbishment measures. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabara, M.; Wu, J.; De Franceschi, S.; Manzardo, A. Assessing Mineral and Metal Resources in Life Cycle Assessment: An Overview of Existing Impact Assessment Methods. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, R.; Zou, L.; Lv, D.; Xu, Y. Effects of Filler–Bitumen Ratio and Mineral Filler Characteristics on the Low-Temperature Performance of Bitumen Mastics. Materials 2018, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Q.; Lei, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, C.; Pan, F. Influence of mineral fillers properties on the bonding properties of bitumen mastics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 126013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittipongvises, S. Assessment of Environmental Impacts of Limestone Quarrying Operations in Thailand. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2017, 20, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Calle, K.; Guillén-Mena, V.; Quesada-Molina, F. Analysis of the Embodied Energy and CO2 Emissions of Ready-Mixed Concrete: A Case Study in Cuenca, Ecuador. Materials 2022, 15, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Product | Carrier | Overview | Correlation Matrix | Test of Significance | Multiple Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasse [31] | Yearly production | Gfib, Pf, Alu | x | x | x | |

| Ökobaudat [30] | G200 S4 | Gfib | x | x | ||

| PYE PV200 S4 | Pf | x | x | x | ||

| PYE PV200 S4 ns | Pf | x | x | x | ||

| V60 | Gfl | x | x | |||

| Ecoinvent [29] | Alu80 | Alu | x | |||

| EP4 | Pf | x | ||||

| PYE PV200 S5 | Gfib | x | ||||

| V60 S4 | Gfl | x | ||||

| VA4 | Gfl/Alu | x | ||||

| Phønix Tag Materialer [32] | AeroTæt PF2000 | Pf | x | x | x | x |

| Aero Tæt PF3200 | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| BituFlex PF5000 SBS | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| BituFlex Kombi PF/GF5000 SBS | Pf/Gfl | x | x | x | x | |

| DuraFlex PF3500 SBS | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| DuraFlex Kombi PF/GF3500 SBS | Pf/Gfl | x | x | x | x | |

| Topmembran PF4600 SBS | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| Flammespærre GF3000 | Glas felt | x | x | x | ||

| Bundmembran PF4500 SBS | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| European Waterproofing Association [33] | Benchmark | Polyester/Gfl | x | x | x | x |

| Danosa [34] | System NTV2/EXT1 | Pf, Gfib | x | x | x | x |

| System TPP1/NTG1 | Pf, Gfib | x | x | x | x | |

| System TVA1/TVH1/TPC1/TPC2 | Pfelt/Gfib | x | x | x | x | |

| ESTERDAN PLUS 50/GP ELAST | Pf | x | x | x | x | |

| POLYDAN PLUS FM 50/GP ELAST | Pfelt/Gfib | x | x | x | x | |

| System NTV6 | Pf | x | x | x | x |

| dof | Mean | Standard Deviation | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPE | 25 | 0.0000031 | 0.0000046 | [0.0 0.0] |

| ADPF | 34.3 | 8.2 | [30.9 37.6] | |

| AP | 0.0029 | 0.0024 | [0.0019 0.0039] | |

| EP-freshwater | 0.000080 | 0.00015 | [2.0 × 10−5 14.2 × 10−5] | |

| EP-marine | 0.00043 | 0.00025 | [0.00033 0.00053] | |

| EP-terrestrial | 0.0065 | 0.0032 | [0.0052 0.0078] | |

| GWP-biogenic | 0.011 | 0.021 | [0.0023 0.020] | |

| GWP-fossil | 0.73 | 0.39 | [0.56 0.89] | |

| GWP-luluc | 0.00092 | 0.00083 | [0.00058 0.0012] | |

| GWP-total | 0.73 | 0.40 | [0.56 0.89] | |

| ODP | 0.00000010 | 0.00000013 | [0.0 0.0] | |

| POCP | 0.0030 | 0.0029 | [0.0018 0.0043] | |

| PENRT | 35.9 | 8.7 | [32.3 39.5] | |

| PERT | 1.6 | 0.81 | [1.2 1.9] | |

| WDP | 0.29 | 0.28 | [0.17 0.40] |

| t-Value | dof | p-Value | CI 95% | M_ g | SD_ g | M_ pg | SD_ pg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPE | 0.40 | 11.2 | 0.694 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.0000016 | 0.0000035 | 0.0000011 | 0.00000067 |

| ADPF | 2.5 | 13.1 | 0.025 ** | [ 1.37 16.87] | 36.1 | 7.2 | 27.0 | 6.8 |

| AP | −1.1 | 13.1 | 0.278 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.0019 | 0.0016 | 0.0028 | 0.0015 |

| EP-freshwater | 1.1 | 10.5 | 0.311 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.000039 | 0.000080 | 0.000012 | 0.0000094 |

| EP-marine | −1.1 | 12.9 | 0.286 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.00046 | 0.00019 | 0.00056 | 0.00018 |

| EP-terrestrial | −0.58 | 10.9 | 0.576 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.0056 | 0.0017 | 0.0062 | 0.0020 |

| GWP-biogenic | 1.8 | 15.6 | 0.088 * | [−0.0 0.02] | 0.0068 | 0.012 | −0.0011 | 0.0058 |

| GWP-fossil | 1.0 | 15.9 | 0.326 | [−0.12 0.35] | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.17 |

| GWP-luluc | −1.4 | 9.8 | 0.202 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.00067 | 0.00049 | 0.0011 | 0.00068 |

| GWP-total | 1.0 | 15.9 | 0.317 | [−0.12 0.35] | 0.66 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.18 |

| ODP | −0.86 | 15.8 | 0.400 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.000000042 | 0.000000084 | 0.000000072 | 0.000000056 |

| POCP | 0.52 | 13.5 | 0.613 | [−0.0 0.0] | 0.0021 | 0.0019 | 0.0017 | 0.00067 |

| PENRT | 2.4 | 11.5 | 0.032 ** | [0.91 16.7] | 37.4 | 6.5 | 28.6 | 7.3 |

| PERT | 2.0 | 12.5 | 0.068 * | [−0.07 1.61] | 1.9 | 0.75 | 1.1 | 0.75 |

| WDP | −2.2 | 9.2 | 0.059 * | [−0.61 0.01] | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.30 |

| Est. | Std. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | r2 | F-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.02 | 0.026 | 39.1 | <0.000 *** | 0.98 | 596.7 |

| Coefficient | −1.1 | 0.045 | −24.4 | <0.000 *** |

| Intercept | Coefficient | p-Value | F-Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPE | −0.0000011 | 0.0000039 | 0.540 | 0.03 | 0.4 |

| ADPF | −8.34 | 67.49 | 0.005 *** | 0.42 | 10.8 |

| AP | 0.0068 | −0.0080 | 0.189 | 0.11 | 1.9 |

| EP-freshwater | −0.00011 | 0.00022 | 0.018 ** | 0.32 | 7.1 |

| EP-terrestrial | 0.0083 | −0.0044 | 0.554 | 0.02 | 0.4 |

| EP-marine | 0.00061 | −0.00012 | 0.869 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| GWP-biogenic | −0.013 | 0.023 | 0.177 | 0.12 | 2.0 |

| GWP-fossil | 0.18 | 0.62 | 0.435 | 0.04 | 0.6 |

| GWP-luluc | 0.0039 | −0.0054 | 0.012 ** | 0.35 | 8.2 |

| GWP-total | 0.17 | 0.65 | 0.426 | 0.04 | 0.7 |

| ODP | 0.00000011 | −0.00000010 | 0.660 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| POCP | −0.00072 | 0.0042 | 0.417 | 0.04 | 0.7 |

| PENRT | −5.2 | 64.8 | 0.011 ** | 0.36 | 8.5 |

| PERT | 0.081 | 2.5 | 0.466 | 0.04 | 0.6 |

| WDP | 1.3 | −1.7 | 0.095 * | 0.17 | 3.2 |

| Intercept | Coefficient | p-Value | r2 | F-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPE | 0.0000019 | −0.0000020 | 0.728 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| ADPF | 50.50 | −51.95 | 0.021 ** | 0.31 | 6.6 |

| AP | −0.0012 | 0.0089 | 0.099 * | 0.17 | 3.1 |

| EP-freshwater | 0.00009 | −0.00019 | 0.029 ** | 0.28 | 5.8 |

| EP-terrestrial | 0.0031 | 0.0069 | 0.297 | 0.07 | 1.2 |

| EP-marine | 0.00038 | 0.00040 | 0.541 | 0.03 | 0.4 |

| GWP-biogenic | 0.006 | −0.014 | 0.378 | 0.05 | 0.8 |

| GWP-fossil | 0.63 | −0.24 | 0.740 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| GWP-luluc | −0.0013 | 0.0055 | 0.003 *** | 0.46 | 12.6 |

| GWP-total | 0.63 | −0.25 | 0.733 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| ODP | 0.00000002 | 0.00000007 | 0.725 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| POCP | 0.00260 | −0.0024 | 0.612 | 0.02 | 0.3 |

| PENRT | 50.9 | −49.0 | 0.039 ** | 0.25 | 5.1 |

| PERT | 2.540 | −2.6 | 0.403 | 0.05 | 0.7 |

| WDP | −0.2 | 1.4 | 0.137 | 0.14 | 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmid, M.T.; Thiel, C. Is It Worth It? Potential for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Bitumen Roofing Membrane Production. Recycling 2025, 10, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060208

Schmid MT, Thiel C. Is It Worth It? Potential for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Bitumen Roofing Membrane Production. Recycling. 2025; 10(6):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060208

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmid, Michael T., and Charlotte Thiel. 2025. "Is It Worth It? Potential for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Bitumen Roofing Membrane Production" Recycling 10, no. 6: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060208

APA StyleSchmid, M. T., & Thiel, C. (2025). Is It Worth It? Potential for Reducing the Environmental Impact of Bitumen Roofing Membrane Production. Recycling, 10(6), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10060208