Abstract

This study investigates additive-free cold calendering of ELT-derived rubber powders across three particle size fractions (<0.5 mm, 0.5–0.71 mm, and 0.71–0.90 mm) using a two-roll mill without external heating or virgin polymers, aiming to obtain a cohesive material. Results demonstrate particle size effects on material properties. The finest fraction exhibited the highest crosslink density (5.30 × 10−4 mol·cm−3), approximately 18% greater than coarser fractions, correlating with superior hardness (≈65 ShA) and elastic modulus (≈7.5 MPa). Tensile properties ranged from 1.6–1.8 MPa stress and 60–75% elongation at break, positioning calendered sheets between low-temperature compression-molded GTR and high-pressure sintered materials reported in the literature. The cold calendering process achieves competitive mechanical performance with reduced energy consumption, simplified processing, and complete retention of recycled content. These findings support the development of regulation-compliant ELT recycling technologies, with potential applications in nonstructural construction panels, vibration-damping components, and protective barriers, advancing circular economy objectives while addressing emerging microplastic concerns.

1. Introduction

End-of-life tires (ELTs) present significant recycling challenges due to their crosslinked structure and accumulation worldwide. Conventional reuse often involves their conversion into rubber granules for synthetic turf infill or blending with thermoplastic binders. However, recent regulations identify these applications as significant sources of microplastics. The accumulation of end-of-life tires (ELTs) represents one of the most pressing challenges in global polymer waste management [1]. Each year, over 1 billion waste tires are produced worldwide, nearly 3.9 million tons annually only in Europe (European Tire and Rubber Manufacturers’ Association [2]). End-of-life tires are predominantly composed of vulcanized rubber, characterized by chemical crosslinking that imparts exceptional resistance and imperviousness to natural biodegradation processes [3,4]. However, this inherent thermosetting nature fundamentally precludes the application of conventional thermoplastic recycling methodologies, thereby generating significant environmental concerns and presenting substantial economic challenges regarding their material recovery and valorization [5,6].

The complex composition of ELTs significantly complicates recycling efforts. A typical passenger tire consists of approximately 47% natural and synthetic rubber (primarily styrene-butadiene rubber and polybutadiene), 22% carbon black as reinforcing filler, 17% steel cord reinforcement, 5% textile fibers, and 9% various additives including zinc oxide, sulfur, accelerators, antioxidants, and processing oils [7]. This heterogeneous structure, combined with the three-dimensional crosslinked network formed during vulcanization, renders ELTs highly resistant to conventional recycling approaches. The sulfur-based crosslinks create covalent bonds between polymer chains that cannot be reversed through simple thermal processing, distinguishing tire rubber from recyclable thermoplastics and necessitating alternative treatment strategies [8].

Historically, ELT management has followed two main routes: energy recovery (e.g., co-incineration or pyrolysis) and material recovery, typically via mechanical grinding into rubber granulate. While energy recovery reduces volume and exploits the calorific value of rubber, it is increasingly criticized for its carbon emissions and the loss of valuable materials, notably carbon black [9]. Energy recovery through incineration or co-processing in cement kilns can achieve thermal efficiencies of up to 80%, yet this approach conflicts with circular economy principles by irreversibly destroying the material structure and embedded carbon content [10,11]. Recovered carbon black is a strategic component in tire formulations, and its preservation or reuse is gaining industrial and regulatory interest. Pyrolysis can isolate carbon black through thermal decomposition in oxygen-free atmospheres at temperatures ranging from 400 °C to 700 °C, yielding pyrolytic carbon black (rCB), oil, gas, and steel wire as recoverable products [7,12]. However, this process requires high energy input (typically 1.5–2.5 MWh per ton of ELTs) [13], complex post-treatment including activation and surface modification to restore the reinforcing properties comparable to virgin carbon black, and sophisticated emission control systems to manage volatile organic compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons released during decomposition. Moreover, the quality and consistency of recovered carbon black remain variable, often exhibiting lower surface area and compromised reinforcing capabilities compared to virgin grades, which limits its direct substitution in high-performance rubber applications [14,15]. Conversely, mechanical recycling retains carbon black within the rubber matrix through ambient or cryogenic grinding processes, enabling partial reuse without component separation and avoiding the energy-intensive thermal treatment required by pyrolysis. Ambient grinding typically produces particles in the range of 0.1–4 mm using shear-based size reduction equipment such as crackers, granulators, and mill systems, while cryogenic grinding employs liquid nitrogen to embrittle the rubber below its glass transition temperature (−70 °C to −90 °C), facilitating finer particle generation with reduced heat buildup and oxidative degradation [16,17]. This approach preserves the original filler network and minimizes surface oxidation, making it particularly suitable for applications requiring retained elastomeric properties. However, mechanical recycling faces inherent limitations: the three-dimensional crosslinked network structure of vulcanized rubber prevents re-melting and conventional thermoplastic processing, while the ground particles exhibit poor interfacial adhesion when incorporated into new rubber compounds or thermoplastic matrices due to the absence of reactive surface groups and the encapsulation of fillers within the devulcanized network [8]. Consequently, mechanically recycled GTR typically suffers from reduced tensile strength (often 30–50% lower than virgin compounds), decreased elongation at break, and compromised fatigue resistance when blended with virgin rubber at loading levels exceeding 10–20 wt% [18,19]. These mechanical property compromises have historically limited the direct reuse of GTR in high-performance applications, driving research efforts toward surface modification techniques, devulcanization strategies, and innovative processing methods that can restore interfacial compatibility and mechanical integrity [20,21].

Recycled rubber powder (ground tire rubber, GTR) has found widespread applications in playground surfaces, bituminous pavements, insulation panels, and as infill material for synthetic turf [22]. However, the latter use is now undergoing major regulatory reevaluation: in 2023, the European Commission adopted new restrictions on intentionally added microplastics, which will include polymeric infill materials such as ELT-derived rubber granules for artificial grass [23]. As a result, products like artificial turf infill (which is typically made from recycled tire rubber) are affected. The new rules prohibit the sale of products intentionally containing microplastic particles beyond set deadlines. Consequently, the use of ELT-derived rubber granules as infill in synthetic turf systems will be phased out by 2031. This regulatory shift effectively eliminates many conventional outlets for tire crumbs. For instance, about 80% of existing artificial-turf infill is made from recycled rubber, so the impending ban has raised serious concerns [24]. Industry associations have warned of “catastrophic consequences” for the tire-recycling sector if alternative uses are not found [24]. More generally, the EU’s REACH-based restriction on rubber granules and powder (enforced through the above regulation) is expected to curtail or ban a wide range of current applications for tire powder. In other words, Europe’s new microplastic rules leave much recycled rubber without its traditional markets.

Given this context, further recycling methods are needed. Existing processes for reusing waste rubber rely on additives or heat. For example, a common approach is to blend ground tire rubber with virgin thermoplastic binders (such as ethylene-vinyl acetate, EVA) to form solid composites. In such blends, the thermoplastic acts as a binder that connects rubber particles [25]. Other studies have explored innovative recycling strategies for GTR, including thermal sintering, microwave-assisted reprocessing, reactive compatibilization, and high-pressure compression molding [26,27]. These techniques typically require substantial energy input, long processing times, additives, or virgin polymer binders to improve cohesion and mechanical strength. While some of these processes have demonstrated promising results, their scalability, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness remain under debate.

In this context, the present study investigates a mechanical calendering process as an additive-free, low-energy recycling method for converting rubber powder from ELTs into dense, cohesive sheets. The process relies exclusively on friction-induced temperature rise and pressure generated during calendering, without the use of virgin binders or external heating. The resulting sheets exhibit good mechanical integrity, with tensile strength, hardness, and crosslink density that are competitive—and in some cases, superior—compared to those reported for sintered GTR products processed under more intensive thermal and pressure conditions.

This study demonstrates that cold calendering represents a viable, additive-free recycling route for converting ELT rubber powder into cohesive monolithic sheets with competitive mechanical properties. Potential applications in nonstructural construction, acoustic insulation, and protective components are cited to contextualize the practical relevance of this recycling technology within emerging circular economy frameworks and regulatory constraints on microplastic generation. However, the primary focus of this investigation is the fundamental characterization of process-structure-property relationships as a function of particle size, rather than comprehensive validation for specific commercial end-uses. This work aims to (i) assess the influence of particle size distribution on the mechanical and structural properties of calendered GTR sheets; (ii) compare the performance of calendered materials with data from sintered GTR sheets in the literature; and (iii) critically discuss the process–structure–property relationships governing this recycling route.

The study delivers: swelling equilibrium measurements and Flory–Rehner analysis to quantify crosslink density as a function of particle size; hardness characterization (Shore A and micro-IRHD) to assess network integrity; tensile testing to determine stress–strain behavior, elastic modulus, and elongation at break; scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examination of fracture surfaces to evaluate particle consolidation and interfacial bonding; and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to characterize inorganic content across particle-size fractions. This approach not only contributes to the growing portfolio of sustainable elastomer recycling technologies but also aligns with future regulatory trends and material circularity goals in the rubber sector.

2. Results

2.1. Leaching Test

Leaching characterization of waste materials is conducted to simulate and quantify the potential release of hazardous substances when waste materials are exposed to aqueous environments under representative disposal or reuse conditions. For end-of-life tire rubber, this assessment is particularly critical due to the complex environmental and regulatory considerations inherent to this waste stream, especially considering the growing utilization of recycled tire rubber as infill material in synthetic turf systems [28,29].

ELT rubber comprises a complex heterogeneous matrix containing vulcanization chemicals, metallic accelerators (including zinc compounds), carbon black reinforcement, and residual processing additives [1]. When subjected to landfill disposal, utilization in civil engineering applications, or incorporation into moisture-exposed products such as playground surfaces, synthetic sports fields, or roadway substrates, water infiltration may facilitate the mobilization of heavy metals and organic contaminants into adjacent soil matrices and groundwater systems. Of particular concern is the potential release of heavy metals. The characterization of leaching behavior permits the quantification of pollutant release, consequently providing fundamental parameters for environmental risk evaluation and impact forecasting frameworks. This data constitutes an essential foundation for comprehending the extended environmental trajectory of rubber tire-derived materials and their potential ecological ramifications, especially within critical applications such as artificial turf infill, where direct anthropogenic contact represents a primary exposure pathway. Furthermore, European Union directives and corresponding national legislation, including the EU Landfill Directive and Waste Framework Directive, mandate that granular waste materials demonstrate inert behavior, defined as the absence of contaminant release above specified regulatory threshold concentrations in standardized leachate tests. For specific applications such as synthetic turf infill materials, additional technical standards apply, notably DIN 18035-7, which establishes comprehensive requirements for materials used in synthetic turf construction. This standard specifically mandates the determination of heavy metal concentrations in leachate extracts, focusing on six critical elements: lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), zinc (Zn), and tin (Sn), which are commonly present in tire rubber due to manufacturing processes and additive formulations. Mercury (Hg), although not typically associated with tire rubber, may be present in other synthetic materials used in sports surfaces and is therefore also reported [28]. The DIN 18035-7 protocol [30] requires aqueous extraction procedures that simulate environmental exposure conditions, enabling the assessment of metal mobility and potential environmental impact when tire rubber infill is subjected to precipitation and irrigation water contact.

Particle size distribution represents a critical parameter in leaching test execution for determining material compliance with reuse requirements, particularly regarding heavy metal release thresholds. The regulatory granulometry specified for conformity assessment ranges from 0.8 to 2.5 mm, and materials demonstrating compliance within this size range may subsequently be commercialized in finer granulometries as rubber powder. However, experimental results presented in Table 1 demonstrate that while the material exhibits conformity for reuse applications when tested at the specified granulometry (0.8–2.5 mm, with Zn concentration of 0.3 mg/L, well below the 3 mg/L limit established by Italian Ministerial Decree 5 February 1998), testing at smaller particle sizes results in zinc concentrations exceeding permissible threshold limits. Specifically, the <0.50 mm fraction released 55.25 mg/L of Zn, the 0.50–0.71 mm fraction released 37.75 mg/L, and the 0.71–0.90 mm fraction released 51.50 mg/L—all values significantly above the reuse limit of 3 mg/L and the inert waste disposal limit of 0.4 mg/L (Italian Ministerial Decree 30 August 2005). These concentrations also exceed the DIN 18035-7 limit of 0.5 mg/L for synthetic turf applications. In contrast, Cd, total Cr, Pb, and Sn concentrations remained below their respective regulatory limits across all fractions tested (Table 1). Zinc emerges as a particularly critical element in tire rubber leaching studies, as extensively documented in the literature examining metals contained and leached from rubber granulates used in synthetic turf applications [31]. The observed increase in zinc leaching at reduced particle sizes can be attributed to the enhanced surface area to volume ratio, which facilitates greater solid–liquid interface contact and consequently increases the potential for heavy metals release.

Table 1.

Leaching test results (L/S = 10 L/kg, 24 h) for ELT powder fractions: Zn, Cd, total Cr, Pb, and Sn concentrations in the eluate.

Harmonized testing protocols such as UNI EN 12457-2 [34] establish standardized experimental parameters, including liquid-solid ratio, and agitation time and conditions, coupled with prescribed analytical methodologies for contaminant quantification. This regulatory framework enables the classification of materials as inert, non-hazardous, or hazardous waste categories while ensuring compliance with application-specific technical requirements. Achieving inert classification for ELT powders significantly expands their potential for safe reuse applications, including synthetic turf infill systems, while circumventing the economic and logistical constraints associated with hazardous waste disposal pathways.

2.2. Crosslink Density

Crosslink density (ν) is a key parameter governing the mechanical integrity, chemical resistance, and dimensional stability of vulcanized rubber: higher generally correlates with greater stiffness, reduced swelling, and improved heat resistance, whereas lower often yields increased elasticity and toughness [5].

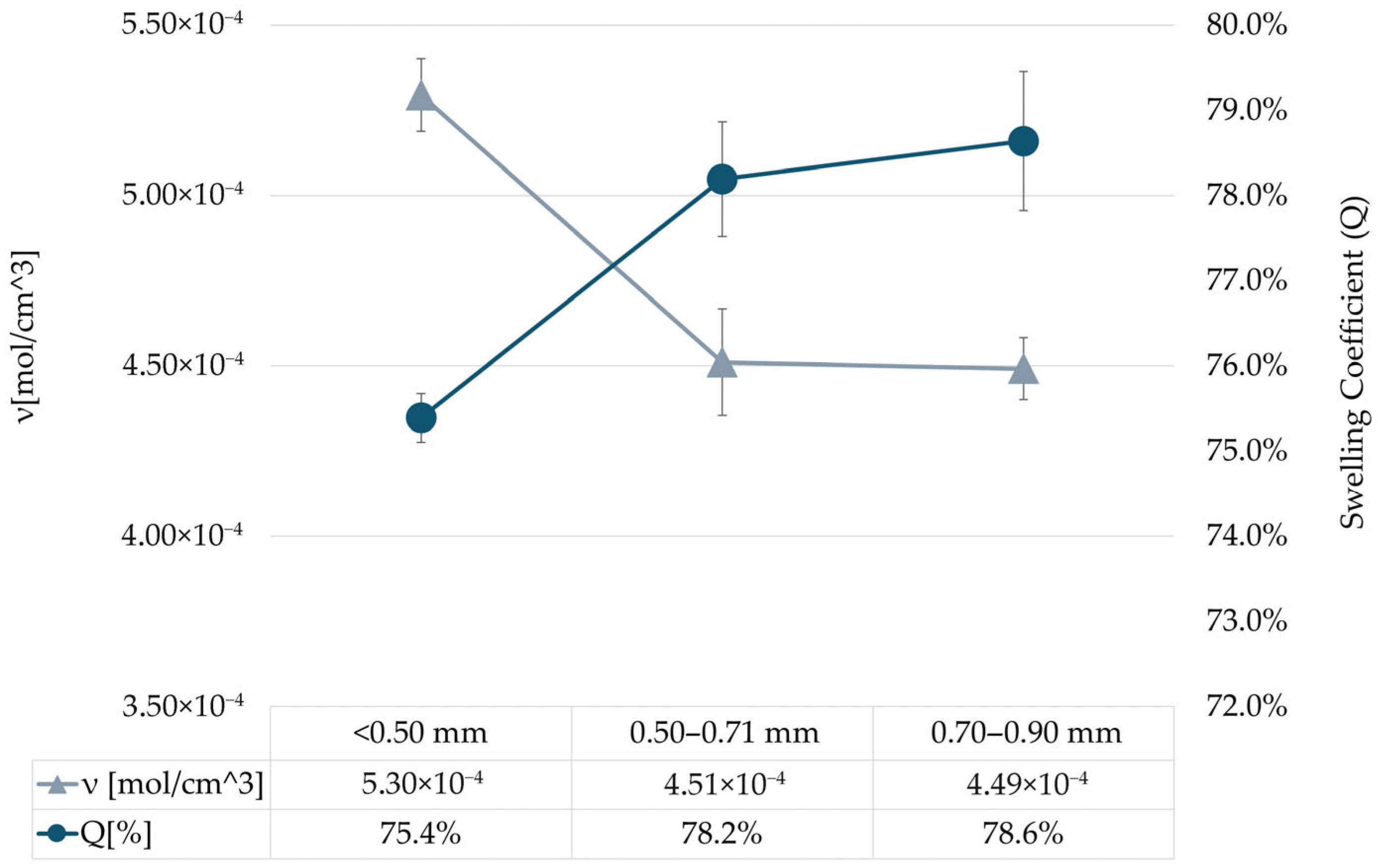

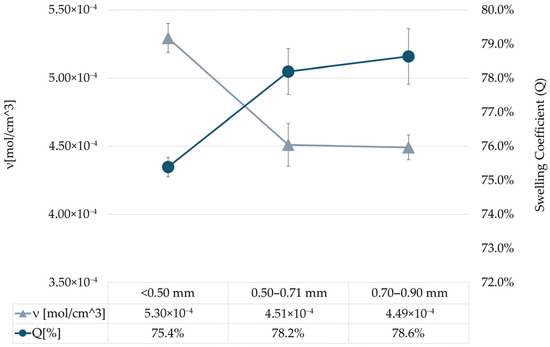

Figure 1 illustrates the influence of powder granulometry on crosslink density in recycled rubber sheets. Samples derived from finer particles consistently achieved higher network densities, with the <0.5 mm fraction reaching 5.30 × 10−4 mol·cm−3, the 0.5–0.71 mm fraction 4.51 × 10−4 mol·cm−3, and the 0.71–0.90 mm fraction 4.49 × 10−4 mol·cm−3. This corresponds to an 18% increase in crosslink density for the finest fraction versus the medium and coarse fractions, respectively, implying that smaller particles promote complete network formation during cold calendering.

Figure 1.

Crosslink density (ν) and swelling coefficient (Q) of recycled ELT rubber sheets as a function of starting powder particle size (<0.5 mm, 0.5–0.71 mm, and 0.71–0.90 mm), determined via toluene swelling and calculated using the Flory–Rehner equation. The error bars indicate the standard deviation over the 3 replicates. The table within the figure reports the average values.

This granulometry-dependent behavior arises from the mechanics of cold calendering, wherein vulcanized rubber particles are forced and stretched between two counter-rotating rolls operating at slightly different rotating speeds. This differential motion induces shear and elongational forces that partially devulcanize the material and remodel its macromolecular network. Given a fixed nominal roll gap of 0.05 mm, finer particles (<0.5 mm) traverse the nip with less deformation, resulting in lower network disruption and higher retained crosslink density. In contrast, coarser particles (0.5–0.71 mm and 0.71–0.90 mm) span the roll gap more fully and undergo greater stretching, promoting more extensive chain scission and a consequent reduction in ν. The similarity in crosslink densities between the two larger fractions indicates that network breakdown scales with relative particle size. It is only when the granulometric difference is greater that the disparity in ν becomes pronounced.

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

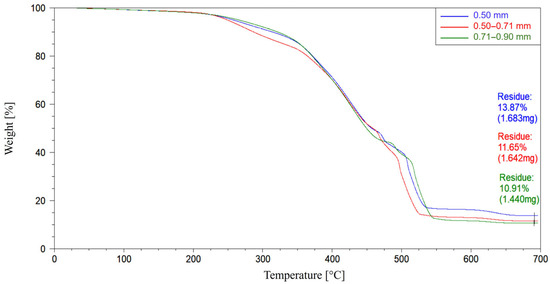

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed under oxidative conditions (air atmosphere) with the primary aim of quantifying the inorganic residue remaining after thermal degradation. This approach allows for the complete oxidation of organic components, including rubber polymers and carbon black, enabling a reliable estimation of the ash content. The final residual mass at 700 °C thus reflects the total non-combustible fraction, including inorganic fillers and any embedded contaminants.

While the oxidative TGA conditions employed in this study enable the identification of different thermal degradation stages (volatile loss, polymeric decomposition, carbon black oxidation, and ash formation), it should be noted that the precise quantification of individual components—particularly the distinction between carbon black and polymer content—is more accurately achieved through TGA being performed under inert atmosphere (nitrogen or argon). Under inert conditions, carbon black remains stable at the temperatures where polymers decompose, allowing for a clear differentiation between these components. However, for the specific objectives of this investigation, the oxidative approach was deemed appropriate as it provides a comprehensive assessment of the total inorganic content, which is particularly relevant for recycled materials derived from end-of-life tires, where variable ash content may arise from environmental exposure, filler composition, or surface contamination introduced during grinding and sieving processes.

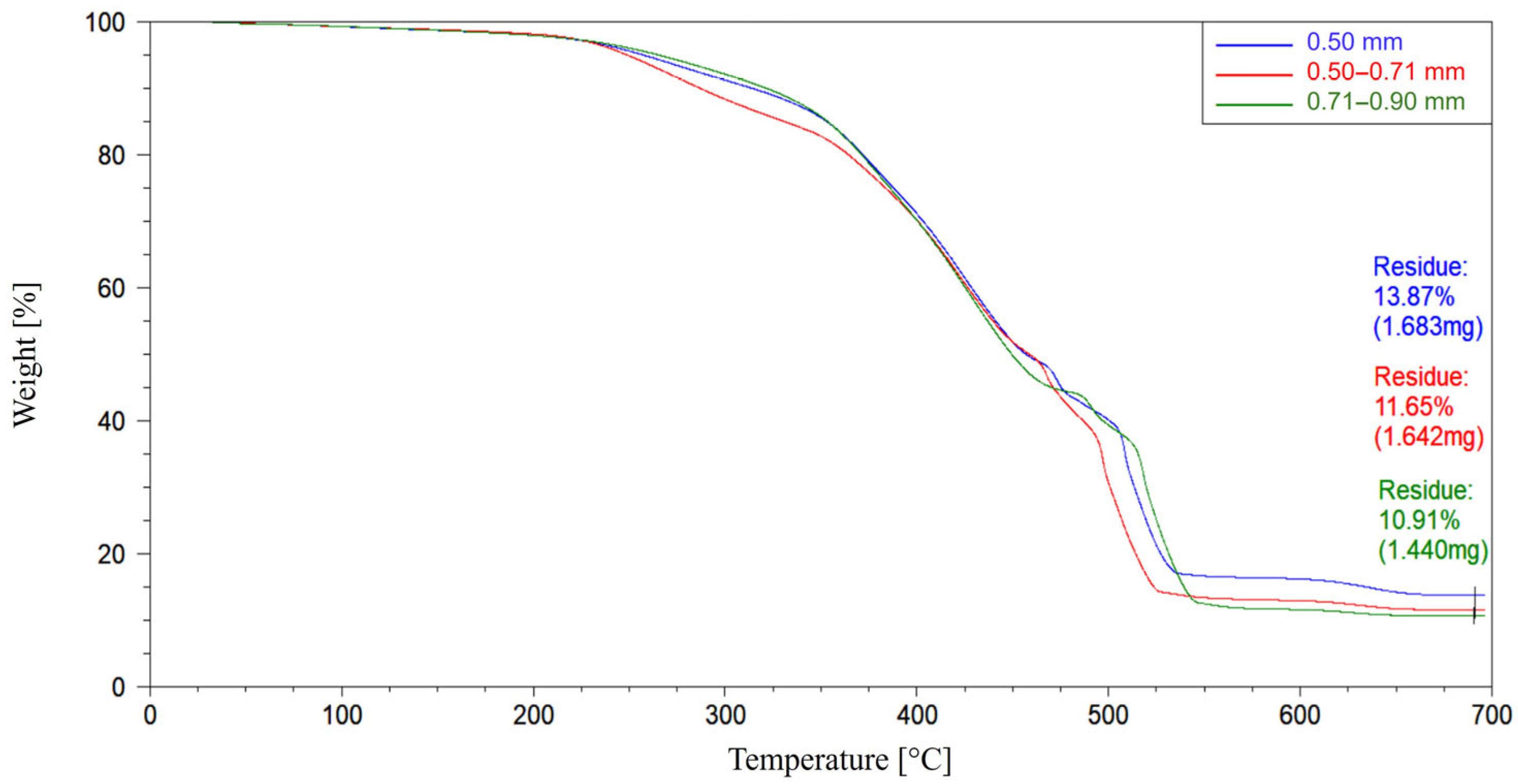

All three particle-size fractions display similar thermal degradation profiles, indicating comparable resistance to heat (Figure 2). However, the residual ash content at 700 °C increases with decreasing powder size: 13.87% for <0.5 mm, 11.65% for 0.5–0.71 mm, and 10.91% for 0.71–0.90 mm, reflecting higher inorganic or contaminant content in finer fractions. This trend is consistent with the use of end-of-life tire rubber: smaller particles are more likely to retain dirt and debris that pass through the sieving process into the finer class.

Figure 2.

TGA of recycled ELT rubber sheets as a function of starting powder particle size (<0.5 mm, 0.5–0.71 mm, and 0.71–0.90 mm).

2.4. Mechanical Tests

The mechanical performance of the recycled ELT rubber was subsequently evaluated through hardness measurements (Shore A and micro-IRHD) and uniaxial tensile test.

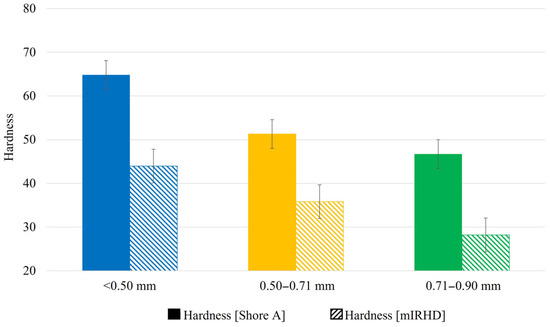

2.4.1. Hardness Test

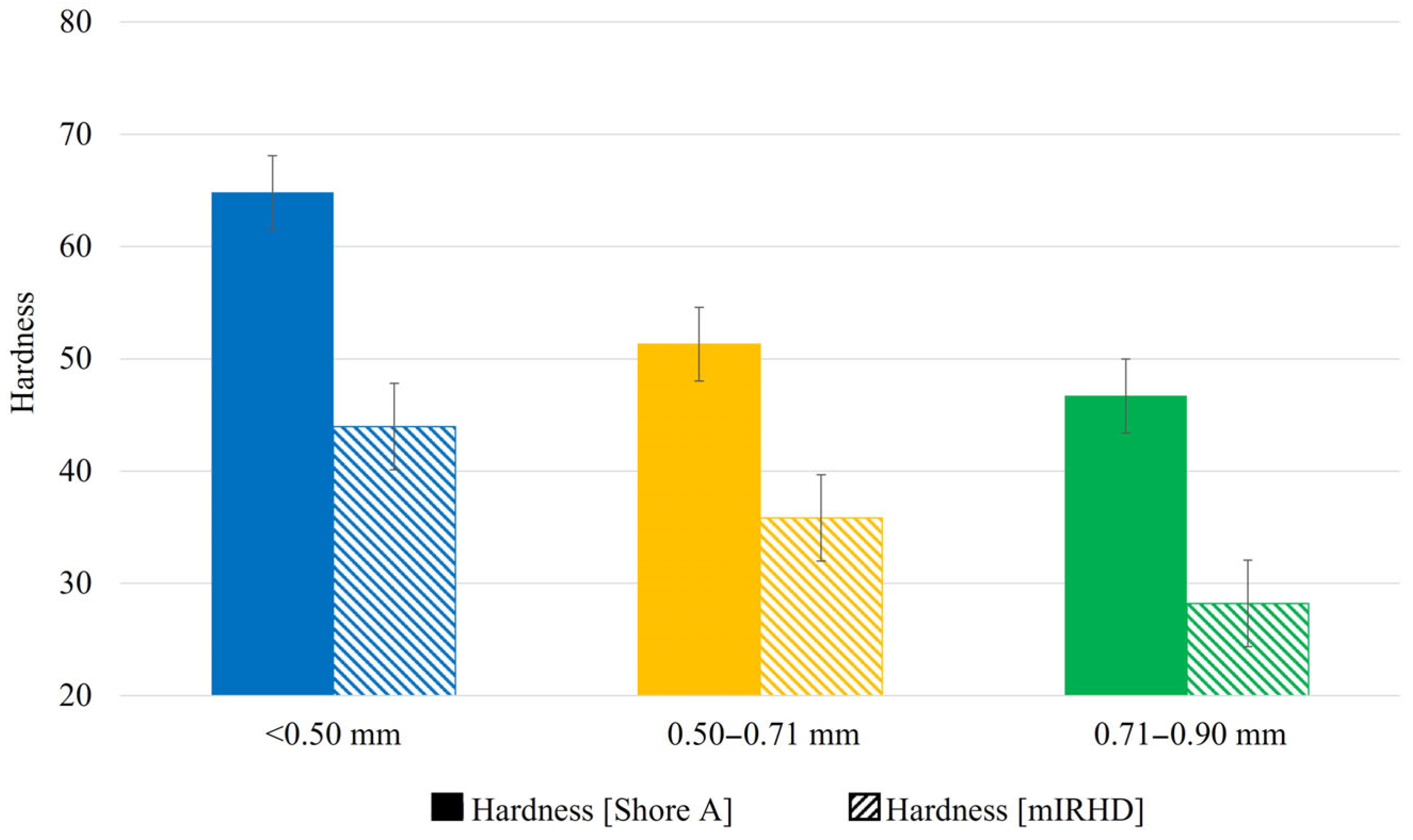

In the rubber industry, hardness is a fundamental mechanical property as it provides a quick way of assessing crosslink density, which is essential for optimal performance. This study evaluated the hardness of recycled rubber sheets derived from fractions of different particle sizes using both the Shore A scale and the micro-IRHD (mIRHD) scale, providing a comprehensive characterization of their mechanical response. While Shore A is the standard method used for rubber characterization and requires specimens at least 6 mm thick, the mIRHD method is widely adopted in industrial practice for evaluating the crosslink state of thin rubber components, which often do not meet the thickness requirements of Shore hardness testing. mIRHD is thus frequently used to indirectly monitor curing performance and define molding process parameters.

As shown in Figure 3, hardness values exhibit a systematic decrease with increasing particle size across both measurement scales. The <0.5 mm fraction demonstrated the highest average hardness values (≈65 Shore A and ≈44 mIRHD), followed by the intermediate 0.5–0.71 mm fraction (≈56 Shore A and ≈36 mIRHD), while the coarsest 0.71–0.90 mm fraction recorded the lowest hardness values (≈51 Shore A and ≈28 mIRHD).

Figure 3.

Shore A and micro-IRHD (mIRHD) hardness values of recycled ELT rubber sheets as a function of starting powder particle size (<0.5 mm, 0.5–0.71 mm, and 0.71–0.90 mm).

This progressive hardness reduction correlates directly with the previously observed crosslink density trends, reinforcing the mechanistic understanding that finer powders preserve a more intact three-dimensional network structure during cold calendering. The higher crosslink density in finer fractions translates to increased material stiffness and enhanced resistance to localized deformation under indentation loads. Conversely, the greater network disruption experienced by coarser particles during processing results in reduced crosslink density and consequently lower hardness values.

2.4.2. Tensile Test

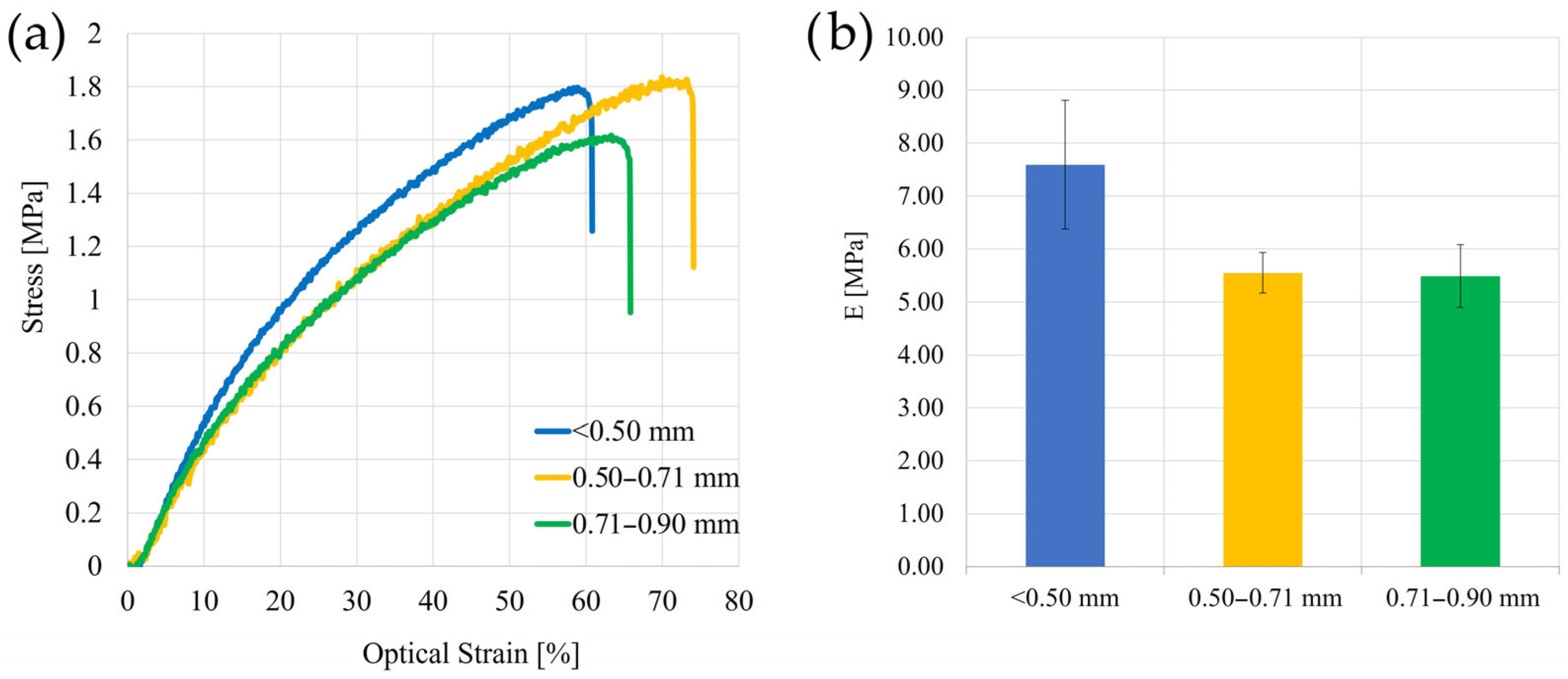

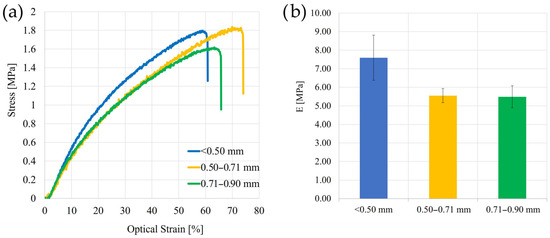

The tensile behavior of the recycled rubber sheets shows a consistent relationship with the initial particle size. Figure 4a presents representative stress–strain curves from five replicates for each granulometric fraction. While the overall behavior is typical of crosslinked elastomers characterized by non-linear elasticity and softening before rupture, the sample derived from the <0.5 mm fraction exhibits a slightly stiffer response. At equal strain levels, it requires higher tensile stress, indicating an increased elastic modulus. This observation is quantitatively confirmed in Figure 4b, where the fine fraction yields the highest modulus (≈7.6 MPa), followed by the 0.5–0.71 mm and 0.71–0.90 mm (≈5.50 MPa) fractions. The modulus increase is consistent with the established relationship between network density and stiffness in vulcanized elastomers, where reduced chain mobility leads to higher elastic modulus [5].

Figure 4.

Mechanical characterization of recycled ELT rubber sheets as a function of powder particle size (<0.5 mm, 0.5–0.71 mm, and 0.71–0.90 mm). (a) Representative stress–strain curves obtained from uniaxial tensile testing. The curves are representative of the average behavior over n = 5 replicates for each material. (b) Elastic modulus values calculated from the initial linear region of the stress–strain curves. The error bars indicate the standard deviation (SD) over the n = 5 replicates.

These differences correlate well with the previously reported crosslink density data (Figure 1): finer powders preserve a denser three-dimensional network, likely due to reduced mechanical disruption during calendering. Notably, the increased stiffness in the <0.5 mm material is accompanied by a modest reduction in elongation at break, though all samples maintain elongation values above 60%, confirming the retention of sufficient ductility. Overall, the mechanical performance supports the conclusion that finer rubber powders yield more structurally robust recycled sheets under additive-free, cold processing.

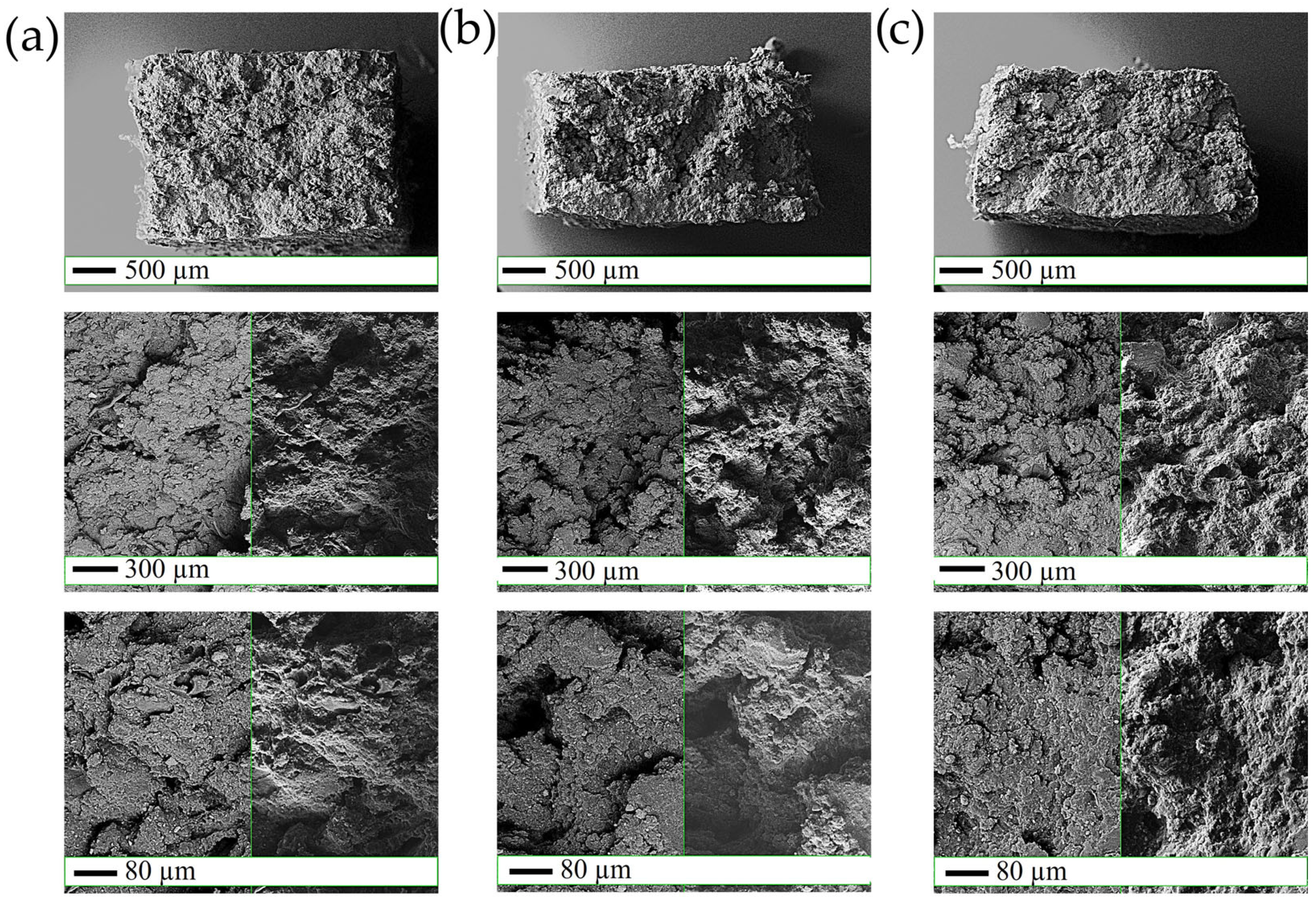

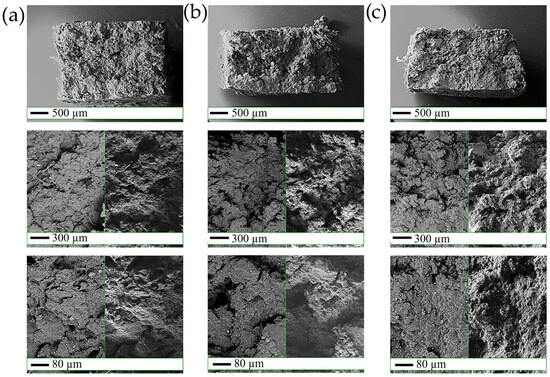

Figure 5 shows the SEM micrograph and backscatter images of cross-sections of samples broken during tensile testing at different intensities. The images reveal that, although the fracture surfaces do not appear as smooth and homogeneous as those of virgin rubber, no discrete rubber particles are distinguishable. Instead, the powders have fused into a continuous matrix, with only minor porosity and discontinuity attributable to unavoidable contaminants in end-of-life tire material. Importantly, no evidence of fracture initiation from dominant defects was observed. Furthermore, when comparing specimens obtained from different initial particle sizes, no discernible differences were detected at any magnification level.

Figure 5.

SEM micrograph and backscattering images of cross-sections of specimens broken in tensile test: (a) fine (<0.5 mm), (b) medium (0.5–0.71 mm), and (c) coarse (0.71–0.90 mm).

3. Discussion

A primary regulatory driver for developing alternative ELT recycling technologies is the growing concern over microplastic pollution from conventional rubber applications. The EU microplastic regulation (Commission Regulation 2023/2055) restricts intentionally added microplastics in products, specifically affecting polymeric infill materials, including ELT-derived rubber granules [22,23]. Current ELT recycling routes involve distinct microplastic generation mechanisms. Synthetic turf infill applications employ unbound rubber granules (0.5–2 mm) that are inherently microplastics (particles < 5 mm). These granules are subject to mechanical fragmentation, abrasion, and hydrological transport. In contrast, the proposed calendering technology transforms the material from a particulate system to a monolithic, continuous structure. Through repeated shear deformation, rubber particles undergo interfacial welding, eliminating discrete particle boundaries. The resulting sheets exhibit a cohesive crosslinked network. This monolithic structure offers significant advantages: (i) elimination of loose particles that can be directly dispersed, (ii) structural integrity through crosslinking that resists fragmentation, and (iii) dramatically reduced surface-area-to-volume ratio compared to granular forms, minimizing weathering interfaces. However, an important limitation must be acknowledged. The calendared sheets remain susceptible to microplastic generation through abrasive wear; therefore, applications involving frictional stresses have to be avoided.

A comprehensive comparison of mechanical properties between calendered and thermally sintered recycled rubber materials reveals distinct performance and processing trade-offs. Thermal sintering processes are well known in the literature: Biglili et al. [35] reported tensile strengths of up to 6 MPa and elongations of up to 400% with a pressing pressure of 6 MPa, while Morin et al. [36] obtained a tensile strength of 3 MPa with an elongation at break of 800% at a pressure of 8.5 MPa. However, these improved properties require specific processing conditions, with minimum temperatures of 100 °C, processing times exceeding 40 min, and applied pressures exceeding 4 MPa. Under more moderate sintering conditions, the mechanical advantages become less pronounced. Quadrini et al. [37,38] employed compression molding at 160 °C and 3 MPa on ELT particles (0–0.05 mm), achieving tensile strengths of only 1 MPa with 30% elongation at break. Notably, when coarser particles (0–0.8 mm) underwent mechanical buffing prior to molding, elongation at break improved substantially to 80%, demonstrating the importance of surface treatment in optimizing interfacial bonding.

Similarly, Lucignano et al. [39] studied sintering pressures between 1.3 and 3.25 MPa on 1.2 mm granules, obtaining tensile strengths between 0.05 and 0.5 MPa and elongations between 5 and 50%. These results illustrate the strong dependence of sintered material properties on processing parameters, where higher pressures generally produce better mechanical performance.

In contrast, the current cold calendering approach achieves tensile strengths of 1.6–1.8 MPa and elongations of 60–75% without requiring high temperatures, prolonged processing times, or high-pressure equipment. Although these properties may not match the maximum performance achievable through optimized thermal sintering, the calendering process offers significant advantages in terms of energy efficiency, processing simplicity, and equipment requirements, making it particularly attractive for large-scale recycling applications where cost-effectiveness and environmental sustainability are key considerations.

4. Materials and Methods

The recycled rubber feedstock was obtained from post-consumer ELTs that had been initially processed through industrial mechanical shredding to produce rubber powder with a nominal particle size of 0.8 mm. The ELT powder composition reflects typical passenger tire tread formulations and consists of:

- Vulcanized rubber matrix: primarily styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) and natural rubber (NR) blends with residual sulfur crosslinks

- Carbon black reinforcement: approximately 20–30 wt% retained within the rubber matrix

- Inorganic fillers: including silica, zinc oxide, and calcium carbonate

- Residual additives: processing oils, antioxidants, and vulcanization accelerators

This study investigates 100% recycled rubber sheets produced exclusively through mechanical consolidation. No virgin rubber, thermoplastic binders, compatibilizers, or chemical devulcanizing agents were added at any processing stage. Approximately 2 kg of this industrially milled powder was separated into three distinct particle-size fractions through sequential sieving on a vibrating platform using stacked test sieves (mesh sizes: 0.90 mm, 0.71 mm, and 0.50 mm) for 30 min to ensure complete size classification, yielding the following fractions:

- Fine fraction: <0.50 mm

- Medium fraction: 0.50–0.71 mm

- Coarse fraction: 0.71–0.90 mm

Environmental safety assessment was conducted through batch leaching tests following UNI EN 12457-2 standard protocol. For the standard rubber particle size range (0.8–2.05 mm) and for each investigated particle size fraction, 90 g of dry rubber powder was placed in an HDPE vessel, and 900 mL of deionized water was added to achieve an L/S ratio of 10 L kg−1. The suspension was agitated continuously at ambient temperature for 24 h. After leaching, samples were filtered through 0.45 µm membranes and the eluates analyzed for metal content. Zinc, cadmium, total chromium, lead, and tin concentrations were determined by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), with detection limits as specified in the standard.

The EN 12457-2 leaching protocol employed in this study is a harmonized European standard widely recognized for waste characterization and environmental compliance assessment across multiple application domains. This standardized methodology is explicitly referenced in the Italian regulatory framework for both material reuse (Ministerial Decree of 5 February 1998) and inert waste disposal (Ministerial Decree of 30 August 2005), as well as in analogous regulations throughout EU member states. The 24-h batch leaching test at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 10 L/kg under continuous agitation represents a conservative approach that maximizes contaminant mobilization, thereby providing a worst-case environmental impact assessment. While application-specific standards exist for particular end-uses, the EN 12457-2 protocol offers a versatile baseline characterization applicable to materials intended for diverse applications, including construction materials, civil engineering uses, and recycled products.

The rubber powder was then reprocessed on a two-roll open mill (Gaoge-Tech instrument, model GAG-R905, Dongguan, China) equipped with counter-rotating chilled cast-iron rolls (working diameter 150 mm, working length 320 mm). This type of open-mill equipment is routinely employed in rubber compounding to disperse additives and achieve homogenous mixing of elastomeric formulations [40]. The calendering process was conducted at ambient temperature without external heating or addition of chemical devulcanizing agents or solvents. Temperature rise during processing resulted exclusively from frictional work and internal viscous dissipation within the rubber powder.

The key processing parameters were maintained constant across all particle-size fractions:

- Roll gap (nip): 0.05 mm

- Front-roll linear speed: 8 m·min−1

- Speed ratio (friction ratio): 1:1.2 between front and back rolls, generating the shear forces

- Motor power: 7.5 kW

- Processing time: approximately 40 min per batch (150 g)

- Number of passes: approximately 450–500 passes (one pass every ~5 s)

Based on the roll geometry and the nominal gap (h = 0.05 mm), the theoretical contact half-width in the nip region can be estimated using Hertzian contact theory as a ≈ √(R × h) ≈ 1.94 mm, corresponding to a contact width of approximately 4 mm. The theoretical maximum separating force, derived from the power-velocity relationship (F = P/v), is approximately 56 kN. However, accounting for mechanical efficiency losses (20–30%), energy dissipation through frictional heating (30–40% of input power), and discontinuous material feed, the effective separating force is estimated at 15–25 kN. With a contact area of approximately 1280 mm2 (320 mm × 4 mm), the average nip pressure is estimated to be in the range of 12–20 MPa.

The calendering treatment induced progressive consolidation of the rubber powder through repeated shear deformation between the rolls. The mechanical work raised the rubber’s temperature to approximately 70 °C, promoting enhanced molecular mobility and interfacial adhesion between particles. Processing continued until the powder transformed into a continuous, cohesive sheet that could be handled without cracking or delamination. No significant differences in the number of passes required to achieve sheet formation were observed among the three particle-size fractions.

The mechanical work raised the rubber’s temperature to approximately 70 °C, as measured via contact thermocouple on the sheet surface during intermittent monitoring between passes. It should be noted that continuous thermal profiling was not performed to avoid disrupting the regular processing sequence; the reported temperature is therefore indicative of the thermal conditions achieved rather than a precisely controlled parameter. This temperature rise demonstrates the significant frictional heating generated by the shear forces during calendering, which contributes to enhanced molecular mobility and interfacial adhesion between particles.

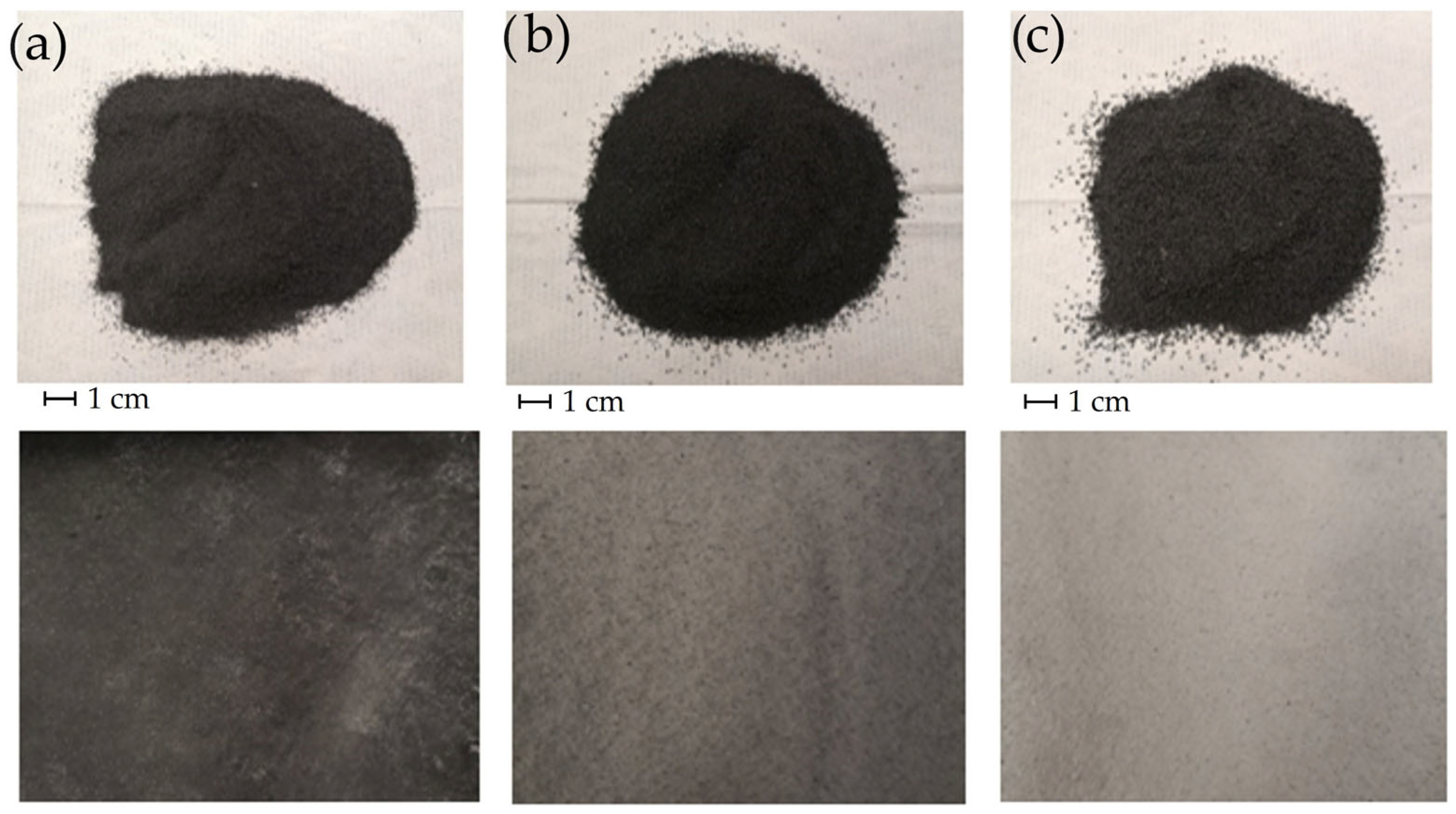

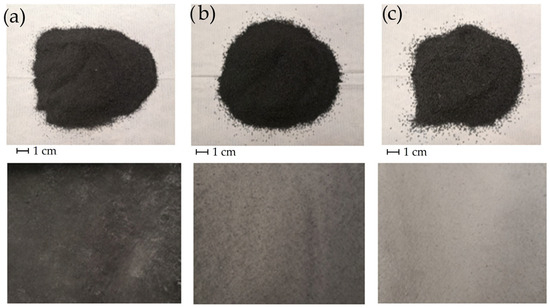

Figure 6 illustrates the macroscopic appearance of ELT-derived rubber powders before and after recycling for the three particle-size fractions.

Figure 6.

Macroscopic view of ELT-derived rubber powders at three particle sizes pre and post recycling: (a) fine (<0.5 mm), (b) medium (0.5–0.71 mm), and (c) coarse (0.71–0.90 mm).

Test specimens were prepared by direct cutting or mechanical punching from the calendered sheets.

Solvent swelling analysis was employed to determine the crosslink density of the rubber specimens through equilibrium swelling measurements. Rectangular test specimens weighing approximately 500 mg (m0) were excised from the rubber sheets and fully immersed in analytical-grade toluene for 48 h at ambient temperature to achieve swelling equilibrium. Upon completion of the immersion period, specimens were dried with absorbent paper to eliminate surface-adhered solvent and immediately weighed to determine the swollen mass (ms). Subsequently, the specimens underwent thermal drying in a convection oven at 80 °C until a constant dried mass (md) was achieved, thereby removing any residual low-molecular-weight extractable compounds. The volumetric swelling coefficient Q was calculated according to Equation (1):

where ρs and ρr represent the density of the swelling agent (0.867 g/cm3 for toluene) and the rubber (1.13 g/cm3).

The equilibrium swelling behavior, governed by the balance between crosslink density and polymer-solvent affinity, was theoretically predicted using the Flory–Rehner Equation (2):

In this relationship, denotes the crosslink density (mol/cm3), represents the molar volume of toluene (106.52 cm3/mol), χ corresponds to the Flory–Huggins polymer-solvent interaction parameter (0.391) [41], and is the volume fraction of rubber in the swollen gel according to Equation (3) [42].

The functionality parameter () was set to 4 [41], assuming tetrafunctional crosslink junctions typical of sulfur-vulcanized rubber networks.

Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on a TA Instruments Q500 analyzer (New Castle, DE, USA). Approximately 10 mg of each recycled rubber sample was heated from room temperature to 700 °C at 10 °C/min in an air atmosphere. The residual mass at 700 °C was recorded to quantify inorganic filler and impurity content across the different particle-size distributions.

Hardness characterization was performed according to ISO 48-4 standard procedures [43] using both Shore A and micro-International Rubber Hardness Degree (mIRHD) scales provided by Gibitre Instruments (Bergamo, Italy). For Shore A measurements, three 2 mm thick sheets were stacked to achieve the minimum specimen thickness requirement of ≥6 mm as specified by the standard. For mIRHD testing, individual 2 mm thick sheets were utilized, which satisfied the thickness requirements for this measurement technique. Three indentations were performed at different locations on each sample to ensure measurement reliability, and mean values with corresponding standard deviations were calculated for each particle-size fraction to quantify the variability within each group.

Uniaxial tensile testing was conducted using an universal testing machine mod. 3366 provided by Instron (Pianezza, TO, Italy) equipped with a load cell capacity of 10 kN. ISO 37 Type 2 dumbbell specimens with a 50 mm gauge length were subjected to tensile loading at a constant crosshead displacement rate of 100 mm/min until failure [44]. The optical strain was determined with image frames at 2-s intervals. The following mechanical properties were extracted from each stress–optical strain curve: initial elastic modulus (determined from the slope of the linear elastic region covering a strain interval between 0% and 5%), ultimate tensile strength, and elongation at break. Five replicate specimens were tested for each particle-size fraction to ensure statistical reliability and to assess the variability of mechanical properties within each group.

Fracture surfaces from tensile test specimens were examined using scanning electron microscopy to assess powder dispersion characteristics and fracture mechanisms. Samples were sputtered with gold. Images were acquired by LEO EVO 40 SEM (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Qualitative comparisons between fine and coarse particle-size fractions focused on matrix–powder adhesion behavior and fracture morphology characteristics.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that cold calendering is a viable and sustainable route for obtaining coherent ELT-based sheets with full recycled content.

The main findings are:

- The additive-free, low-energy process converts ELT powders into cohesive sheets without external heating or virgin binders, relying solely on friction-induced temperature rise.

- Finer powder fractions (<0.5 mm) retain the highest crosslink density (5.30 × 10−4 mol·cm−3, ~18% higher than coarser powders), resulting in increased hardness and modulus.

- The recycled sheets exhibit tensile strengths of 1.6–1.8 MPa and elongation at break of 60–75%, positioning the material between low-temperature compression-molded and high-pressure sintered GTRs. Compared with sintering, calendering provides a favorable balance between mechanical performance and energy demand, while preserving 100% recycled content.

- The transformation from particulate rubber to a monolithic structure addresses the EU microplastic regulation (2023/2055), as the calendered sheets prevent direct particle dispersion. However, microplastic formation may still occur under severe abrasion.

The demonstrated feasibility of additive-free mechanical recycling for ELT rubber therefore represents a significant advance in circular material management, providing a practical pathway for resource recovery in line with emerging regulatory frameworks and circular economy principles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and G.R.; methodology, A.G. and G.R.; validation, A.G., G.R., K.D. and G.C.; formal analysis, A.G.; investigation, A.G.; resources, G.R.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, G.C., G.R. and K.D.; supervision, G.R. and G.C.; project administration, G.R.; funding acquisition, G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank GesTyre SRL (Brescia), REP SRL (Brescia), and Eng. Fabrizio Pasolini, for providing the materials and test equipment. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) to improve the text’s clarity and readability. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the tool-generated output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ELT | End-of-Life Tires |

References

- Battista, M.; Gobetti, A.; Agnelli, S.; Ramorino, G. Post-Consumer Tires as a Valuable Resource: Review of Different Types of Material Recovery. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2020, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers’ Association, E. End-of-Life Tyres in a Circular Economy: ETRMA’s Perspective on a Competitive Recycling Sector. Available online: https://tyreseurope.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Gobetti, A.; Cornacchia, G.; Ramorino, G. Transforming Waste into Valuable Resources: Recycled Nitrile-Butadiene Rubber Scraps Filled with Electric Arc Furnace Slag. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, A.; Ramorino, G.; Gelfi, M.; Depero, L.E.; Zacco, A.; Fenotti, M.; Cornacchia, G. Innovative Application of Steelmaking Slag from Ladle Furnace as Filler for Recycled Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Industrial Scrap. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, A.; Kiesewetter, J. Determination of the Crosslink Density of Tire Tread Compounds by Different Analytical Methods. KGK Kautsch. Gummi Kunststoffe 2019, 72, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gobetti, A.; Marchesi, C.; Depero, L.E.; Ramorino, G. Characterization of Recycled Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Industrial Scraps. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Kucinska-Lipka, J.; Janik, H.; Balas, A. Progress in Used Tyres Management in the European Union: A Review. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formela, K. Sustainable Development of Waste Tires Recycling Technologies—Recent Advances, Challenges and Future Trends. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2021, 4, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, A.; Cornacchia, G.; Agnelli, S.; Ramini, M.; Ramorino, G. A Novel and Sustainable Rubber Composite Prepared from Electric Arc Furnace Slag as Carbon Black Replacement. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2024, 7, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.T. Pyrolysis of Waste Tyres: A Review. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1714–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahijani, P.; Zainal, Z.A. Gasification of Palm Empty Fruit Bunch in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed: A Performance and Agglomeration Study. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2068–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.D.; Puy, N.; Murillo, R.; García, T.; Navarro, M.V.; Mastral, A.M. Waste Tyre Pyrolysis—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.; Chaala, A.; Darmstadt, H. Vacuum Pyrolysis of Used Tires End-Uses for Oil and Carbon Black Products. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1999, 51, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formela, K.; Cysewska, M.; Haponiuk, J.T. Thermomechanical Reclaiming of Ground Tire Rubber via Extrusion at Low Temperature: Efficiency and Limits. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2016, 22, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikakos, L.D.; Papadaskalopoulou, C.; Hofko, B.; Gschösser, F.; Cannone Falchetto, A.; Bueno, M.; Arraigada, M.; Sousa, J.; Ruiz, R.; Petit, C.; et al. Harvesting the Unexplored Potential of European Waste Materials for Road Construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 116, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; De, D.; Maiti, S. Reclamation and Recycling of Waste Rubber. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000, 25, 909–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarad, S.; Khalid, M.; Ratnam, C.T.; Chuah, A.L.; Rashmi, W. Waste Tire Rubber in Polymer Blends: A Review on the Evolution, Properties and Future. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 72, 100–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.R.; Fuhrmann, I.; Karger-Kocsis, J. LDPE-Based Thermoplastic Elastomers Containing Ground Tire Rubber with and without Dynamic Curing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 76, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, X.; Cañavate, J.; Carrillo, F.; Lis, M.J. Acoustic and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polyvinyl Chloride/Ground Tyre Rubber Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2014, 48, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; Maiti, S.; Adhikari, B. Reclaiming of Rubber by a Renewable Resource Material (RRM). III. Evaluation of Properties of NR Reclaim. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 75, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaro, L.; Gratton, M.; Seghar, S.; Aït Hocine, N. Recycling of Rubber Wastes by Devulcanization. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbe, U.; Krüger, O.; Wachtendorf, V.; Berger, W.; Hally, S. Development of Leaching Procedures for Synthetic Turf Systems Containing Scrap Tyre Granules. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2055—Restriction of Microplastics Intentionally Added to Products. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/chemicals/reach/restrictions/commission-regulation-eu-20232055-restriction-microplastics-intentionally-added-products_en#:~:text=added to products-,Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2055—Restriction of mi (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- EU Commission Bans Crumb Rubber Infill. Available online: https://scraptirenews.com/2023/11/03/eu-commission-bans-crumb-rubber-infill/#:~:text=Image 49For crumb rubber,the Council raised any objections (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Marín-Genescà, M.; García-Amorós, J.; Mujal-Rosas, R.; Vidal, L.M.; Arroyo, J.B.; Fajula, X.C. Ground Tire Rubber Recycling in Applications as Insulators in Polymeric Compounds, According to Spanish Une Standards. Recycling 2020, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli, A.; Rodrigue, D. Recycling Waste Tires into Ground Tire Rubber (Gtr)/Rubber Compounds: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toncheva, A.; Brison, L.; Dubois, P.; Laoutid, F. Recycled Tire Rubber in Additive Manufacturing: Selective Laser Sintering for Polymer-Ground Rubber Composites. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, B.; Forte, G.; Petrucci, F.; Costantini, S.; Izzo, P. Metals Contained and Leached from Rubber Granulates Used in Synthetic Turf Areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Sloot, H.A.; Comans, R.N.J.; Hjelmar, O. Similarities in the Leaching Behaviour of Trace Contaminants from Waste, Stabilized Waste, Construction Materials and Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 1996, 178, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 18035-7:2002-06; Sports Grounds Part 7; Synthetic Turf Areas Determination of Environmental Compatibility. Deutsches Institut fuer Normung: Berlin, Germany, 2002; pp. 6–8.

- Park, J.K.; Edil, T.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Huh, M.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.J. Suitability of Shredded Tyres as a Subsitute for a Landfill Leachate Collection Medium. Waste Manag. Res. 2003, 21, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supplemento Ordinario Alla Gazzetta Ufficiale 16 Aprile 1998 n. 88 Individuazione Dei Rifiuti Non Pericolosi Sottoposti Alle Procedure Semplificate Di Recupero Ai Sensi Degli Articoli 31 e 33 Del Decreto Legislativo 5 Febbraio 1997, n. 22. 1998. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1998/04/16/098A3052/sg%20 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. Ministero Dell’ambiente e Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare Gazzetta Ufficiale Del 31 Marzo 2020, n.78; Gazzetta Ufficiale: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/07/21/20G00094/sg (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- UNI EN 12457-2 Characterisation of Waste—Leaching—Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges—Part 2: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 l/Kg for Materials with Particle Size Below 4 Mm (Without or with Size R). 2004. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/511437969/BS-EN-12457-2-2002 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Bilgili, E.; Dybek, A.; Arastoopour, H.; Bernstein, B. A New Recycling Technology: Compression Molding of Pulverized Rubber Waste in the Absence of Virgin Rubber. J. Elastomers Plast. 2003, 35, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.E.; Williams, D.E.; Farris, R.J. A Novel Method to Recycle Scrap Tires: High-Pressure High-Temperature Sintering. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2002, 75, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrini, F.; Bellisario, D.; Santo, L.; Hren, I. Direct Moulding of Rubber Granules and Powders from Tyre Recycling. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 371, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrini, F.; Santo, L.; Musacchi, E. A Sustainable Molding Process for New Rubber Products from Tire Recycling. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2018, 35, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucignano, C.; Gugliemotti, A.; Quadrini, F. Compression Moulding of Rubber Powder from Exhausted Tyres. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2012, 51, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, A.; Tomasoni, G.; Cornacchia, G.; Ramorino, G. Steel Slag as a Low-Impact Filler in Rubber Compounds for Environmental Sustainability. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2024, 39, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formela, K.; Cysewska, M.; Haponiuk, J. The Influence of Screw Configuration and Screw Speed of Co-Rotating Twin Screw Extruder on the Properties of Products Obtained by Thermomechanical Reclaiming of Ground Tire Rubber. Polimery/Polymers 2014, 59, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, V.P.; Stephen, R.; Greeshma, T.; Sharan Dev, C.; Sreekala, M.S. Mechanical and Swelling Behavior of Green Nanocomposites of Natural Rubber Latex and Tubular Shaped Halloysite Nano Clay. Polym. Compos. 2016, 37, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 48-4; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Hardness—Part 4: Indentation Hardness by Durometer Method (Shore Hardness). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 37; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).