Abstract

The structural and interfacial stability of silicon-based and lithium metal anode materials is essential to their battery performance. Scientists are looking for a better inactive material to buffer strong volume change and suppress unwanted surface reactions of these anodes during cycling. Lithium silicates formed in situ during the formation cycle of silicon monoxide anode not only manage anode swelling but also avoid undesired interfacial interactions, contributing to the successful commercialization of silicon monoxide anode materials. Additionally, lithium silicates have been further utilized in the design of advanced silicon and lithium metal anodes, and the results have shown significant promise in the past few years. In this review article, we summarize the structures, electrochemical properties, and formation conditions of lithium silicates. Their applications in advanced silicon and lithium metal anode materials are also introduced.

1. Introduction

Silicon monoxide (SiO) is regarded as one of the next-generation anode materials to replace graphite in Li-ion batteries (LIBs). The advantages of SiO include low cost and abundant raw materials (silicon and silica), environmental benignity, facile fabrication, and high specific capacity (2100 mAh g−1) [1]. However, low conductivity, swelling after lithiation, and poor first-cycle efficiency (<60%) [2] in LIBs hinder the commercialization of SiO anodes. Researchers have designed the SiO anode material structure, majorly decorated with conductive carbon coatings, to boost the battery performance of SiO anodes in order to obtain high energy density, rapid charge/discharge capability, long cycle life, and improved first-cycle efficiency.

Current commercial SiO materials in the battery market are employed in anodes for LIBs and optical coating applications. SiO is synthesized by mixing silicon and silica in a 1:1 molar ratio and then subliming the mixture to collect the amorphous SiO (a-SiO) material. Since the silicon atoms in a-SiO are randomly distributed, their valence numbers can be 0, 1+, 2+, 3+, and 4+ upon the bonding condition with different numbers of oxygen atoms [3]. Some silicon atoms agglomerate and form tiny silicon crystals surrounded by other amorphous substances, with Si–O bonds that have different valence numbers of silicon. In LIBs, these tiny silicon crystals in a-SiO react with Li+ ions and form Li15Si4 [4,5], serving as the active material to store energy. Owing to the nano scale of tiny silicon crystal, no pulverization occurs after lithiation [6]; therefore, good reversibility can be obtained. The Si–O bonding area has more complicated reactions with Li+ ions. Not only is a portion of silicon reduced, forming lithium silicide alloys, but Li2O and various lithium silicates can be formed, serving as ionic conductors and structural stabilizers [4,5].

Compared to SiO anode materials, high-capacity anode materials consisting of pristine silicon still have a lot of obstacles to be overcome due to their severe swelling behavior and poor cycle life [7,8]. Under systematic electrochemical characterizations, SiO anode outperformed silicon in terms of volume-expansion control, rate performance, and Li-diffusion coefficient [9]. It is believed that lithium silicates generated in situ in SiO anodes after initial lithiation play a critical role in buffering the volume expansion and maintaining structural integrity, resulting in great cycle performance comparable to conventional graphite anodes. There are also many recent publications showing that lithium silicates can serve as a good protective layer to improve battery performance of silicon-based and lithium metal anode materials. In this review, we introduce the material properties of different types of lithium silicates and their applications, as well as future prospects in anode materials for high-energy-density batteries.

2. Structures of Lithium Silicates

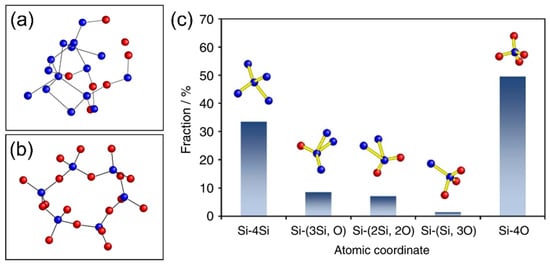

Before studying the structures of lithium silicates, we should understand how they are formed in lithiated a-SiO material. Atomic models of suboxide-type tetrahedra in a-SiO and amorphous SiO2 using angstrom-beam electron diffraction (ABED) and synchrotron high-energy XRD (HEXRD) techniques can be seen in Figure 1a,b [10], where a-SiO exhibits a very disordered structure. It was found that five bonding structures can be formed in a-SiO, including Si–4Si, Si–(3Si+1O), Si–(2Si+2O), Si–(1Si+3O), and Si–4O (Figure 1c). This shows that pure silicon (Si–4Si) and silica (Si–4O) are not the only phases, but there are considerable fractions of various suboxide tetrahedra remaining in the interface of Si/SiO2, leading to more complex reactions during lithiation/delithiation in LIBs. Since a-SiO is a thermally unstable material, the disproportionation reaction transforms a-SiO into a mixture of crystalline silicon and silica after heat treatments [11,12]. When disproportionated, a-SiO is lithiated and delithiated, also showing distinctive behavior compared to pristine a-SiO. As a result, owing to the variety of Si-O bonding structures, different lithium silicates could be generated in SiO/SiOx anode materials after lithiation.

Figure 1.

Atomic models of (a) interfacial suboxide-type tetrahedra in a-SiO and (b) amorphous SiO2 in a-SiO. (c) Fractions of the five atomic coordinates found in a-SiO. The silicon atom is in blue, and the oxygen atom is in red. Reproduced with permission from ref. [10]. Copyright 2015, Nature Publishing Group.

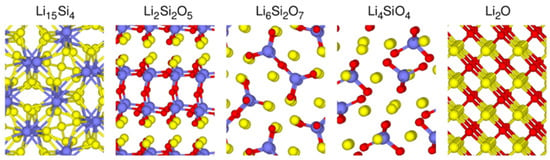

Jung et al. adopted Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) to simulate lithiated SiO structure via density functional theory (DFT), Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE), and projector-augmented wave (PAW) methods [13]. Figure 2 shows the possible phases composed of elements Li, Si, and O after the lithiation of SiO. In fact, not only can Li4SiO4 proposed by a simple lithiation model [4] be generated, but crystalline Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 could also exist during the electrochemical reactions. When the ratio of Li to SiO is lower (2.65–3.54), Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 phases are generated. When the ratio of Li to SiO reaches more than 3.81, crystalline Li4SiO4 is the dominant lithium silicate phase. In Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 structures, each SiO4 tetrahedron shares three oxygens and one oxygen with the neighboring tetrahedra, respectively, to form bonds. In contrast, the SiO4 tetrahedron of Li4SiO4 does not share any oxygen. Due to the high activation energy of SiO4 tetrahedron decomposition, Li2Si2O5, Li6Si2O7, and Li4SiO4 are difficult to reduce to silicon or to convert into Li2O, representing their high irreversibility [13].

Figure 2.

Crystalline structures of Li15Si4, Li2Si2O5, Li6Si2O7, Li4SiO4, and Li2O. The silicon atom is in blue, the oxygen atom is in red, and the lithium atom is in yellow. The bond length of Si-Si is 2.8 Å, and that of Si-O is 2.0 Å. To make the structures look succinct, only Si-O bonds are shown in Li2Si2O5, Li6Si2O7, and Li4SiO4. Reproduced with permission from ref. [13]. Copyright 2015, ACS Publications.

3. Electrochemical Properties and Formation Conditions of Lithium Silicates

Since various lithium silicates have different crystalline structures and Li/Si ratios, their material properties and electrochemical properties are not the same. For instance, the Li diffusivities of compounds consisting of lithium, silicon, and oxide were calculated via the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method, and the diffusivities ranked from low to high are: Li6Si2O7 (1.8 × 10−12) < Li2Si2O5 (1.3 × 10−11) < Li4SiO4 (1.1 × 10−10) < Li2O (1.8 × 10−8) < Li15Si4 (8.8 × 10−6) [13]. According to the simulation results, fully-lithiated silicon has the highest diffusivity compared to all lithium silicates, and Li2O has a Li diffusivity that is two orders of magnitude higher than that of other inactive lithium silicates [13]. Another report demonstrated that at low Li concentrations, the diffusivity of Li+ ions in lithium silicates is two orders of magnitude lower than that of lithium silicides (LixSi), but it rapidly increases with increasing Li content [14]. Lithium silicates with high Li-ion diffusivity facilitate fast charge/discharge capability, high utilization of active materials, and low polarization/overpotential. In the subsections below, we introduce the electrochemical properties and formation conditions of lithium silicates in anode materials. Simplified formation mechanisms of lithium silicates from SiO and SiO2 can be shown as follows (assuming LixSiyOz species are generated before LixSi) [15,16]:

4 SiO + 4 (Li+ + e−) → 3 Si + Li4SiO4

2 SiO2 + 4 (Li+ + e−) → Si + Li4SiO4

14 SiO + 12 (Li+ + e−) → 10 Si + 2 Li6Si2O7

7 SiO2 + 12 (Li+ + e−) → 3 Si + 2 Li6Si2O7

6 SiO + 4 (Li+ + e−) → 4 Si + 2 Li2SiO3

3 SiO2 + 4 (Li+ + e−) → Si + 2 Li2SiO3

10 SiO + 4 (Li+ + e−) → 6 Si + 2 Li2Si2O5

5 SiO2 + 4 (Li+ + e−) → Si + 2 Li2Si2O5

3.1. Li4SiO4

As one of the major phases in lithiated a-SiO, Li4SiO4 is the most studied buffer material that minimizes the volume expansion of SiO anode [4,5,11,17]. Li4SiO4 functions as an inactive material but can maintain structural integrity due to its strong mechanical strength. The capability of conducting Li+ ions is very important for Li4SiO4 to serve as both an ionic conductor and a buffer material, which guarantees smooth electrochemical reactions. It was reported that, in terms of Li ionic conductivity, the conductivity of crystalline Li4SiO4 in SEI detected by atomic visualization is estimated to be 1000 times greater than that of Li2O, according to molecular dynamic simulation [18]. Pristine Li4SiO4 has been identified as either chemically or electrochemically inactive with lithium [1]. This means that Li4SiO4 can be neither lithiated nor delithiated once formed [1,19,20]. However, Hirose et al. demonstrated that Li4SiO4 can release Li+ ions at a high potential (2.5 V vs. Li/Li+) [17,21]. Additionally, it is believed that Li4SiO4 is the lithium silicate with the highest Li/Si ratio that can be formed in an electrochemical cell. Coyle et al. adopted radio-frequency magnetron sputtering of both SiO2 and Li2O targets to make thin lithium silicate films with various compositions, and a lithium-rich Li8SiO6 (Li/Si = 8) phase was confirmed by inductively coupled optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [22]. However, there have been no electrochemical performance data reported on Li-rich lithium silicates with a Li/Si ratio higher than four.

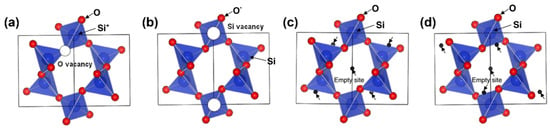

Yamamura et al. found that neither crystalline Li4SiO4 nor SiO2 can react with lithium metal, but amorphous SiO2 showed Li-ion activity [1]. It is believed that the SiO4 tetrahedra in Li4SiO4 and SiO2 are difficult to reduce by lithium metal and ions, but the dangling bonds and distorted SiO4 tetrahedra in a-SiO2 can facilitate reactions with lithium. The formation energy (Ef) of lithium inserting into the SiO4 tetrahedra of crystalline SiO2 can be calculated. When lithium stays in the O vacancy (Figure 3a), the Ef is 0.44 eV, requiring extra energy to be stabilized. When lithium is in the Si vacancy (Figure 3b), the Ef is −3.66 eV, which represents a spontaneous exothermic reaction of Li+ with O−. This indicates that lithium has a high tendency to bond with oxygen due to the electrostatic attraction force originating from their opposite charges. In addition, when lithium is located at the empty sites in the structure shown in Figure 3c,d, the Ef is 1.15 eV and 1.18 eV, respectively, implying the difficulty of creating bonds. Sivonxay et al. employed DFT and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) methods to demonstrate that amorphous SiO2 is thermodynamically driven to be lithiated, which shows that Li–O local environments are increasingly favored, as compared to Si–O bonding [14]. Moreover, amorphous SiO2 and SiO have disordered structures, including many vacancies, dangling bonds, and non-equivalent bond lengths, offering more reaction sites for lithiation. This explains why amorphous silicon oxides exhibit lithium activity, while crystalline Li4SiO4 and SiO2 are considered chemically and electrochemically inert with lithium.

Figure 3.

The crystalline structure of SiO2 (P3121 space group) drawn via the VESTA method (a) with O vacancy, (b) with Si vacancy, and (c,d) with empty sites. Reproduced with permission from ref. [1]. Copyright 2011, The Ceramic Society of Japan.

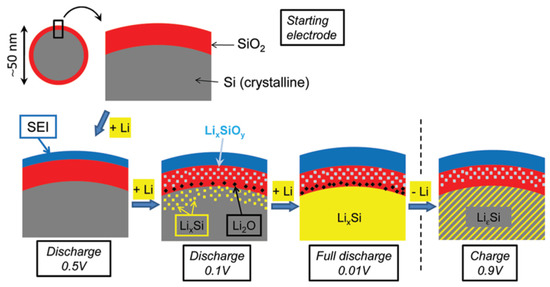

Lithium silicates were also discovered in the oxidized surface of silicon nanoparticles during cycling in LIBs [23]. When pure silicon is in contact with air, a thin nanocoating of silica is formed on the silicon surface, which prevents further oxidation. Figure 4 exhibits how the microstructure and composition of nano-sized Si with naturally formed SiO2 change, along with discharge and charge conditions. When the silica-covered silicon anode is discharged to ~0.5 V, a solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer is formed under the electrolyte reduction reactions. This layer passivates the anode surface to avoid further Li-ion and electrolyte consumption. While the Li/Si cell is deeply discharged, both LixSiyOx and Li2O are formed in the surface oxide region, and LixSi is formed in the core silicon region. By analyzing the signal of Si 2p spectra, it was confirmed that Li4SiO4 is the main lithium silicate phase [23]. After the cell is recharged to 0.9 V, Li2O is gone, but Li4SiO4 still exists in the structure, evidencing the reversibility of Li2O and the irreversibility of Li4SiO4. On the surface of a silicon anode, Li4SiO4 remains in the protective layer, remaining unchanged during cycling, similar to a-SiO and disproportionated SiOx anodes [12,13].

Figure 4.

Microstructure of nano-sized Si with naturally formed SiO2 on the surface. Composition changes during shallow and deep discharge and full recharge. Reproduced with permission from ref. [23]. Copyright 2012, ACS Publications.

The formation of Li4SiO4 in SiO/SiOX-based anodes occurs during the first discharge process at <0.24 V vs. Li/Li+, and the crystalline phase remains in the anode structure regardless of cell recharge or cycling, showing strong irreversibility [19,20,24]. Besides the electrochemically generated Li4SiO4 in situ, Li4SiO4 can be synthesized by the thermal reaction of SiO and lithium hydroxide cofired at 550 °C [25,26]. A simple hydrothermal synthesis method (175 °C) using fumed silica and lithium hydroxide can also produce Li4SiO4 [27]. A citric-acid-based sol-gel route (also with fumed silica and LiOH) was developed to synthesize macroporous Li4SiO4 with a carbon coating [28]. Due to the stability of electrochemical cells and the synthesizability of Li4SiO4, it can serve as a promising protective buffer material for silicon and lithium metal anodes, which will be discussed in the next section.

3.2. Li2SiO3

Li2SiO3 has lithium activity, unlike Li4SiO4, with a reversible capacity of <200 mA h g−1 [29]. Yang et al. utilized graphene to prepare a composite material with Li2SiO3 as the anode, showing good cycle life [29]. Pristine Li2SiO3 has sloping charge/discharge curves with an average voltage above 1 V, and it can be reversibly cycled in a half cell with lithium metal. Li2SiO3 can be formed by heating a graphite/Li4SiO4 mixture at 600 °C [30]. A graphite composite sample with Li2SiO3 obtained a higher capacity than that with Li4SiO4, although larger first-cycle capacity loss was also found in an anode sample with Li2SiO3. Xiao et al. pointed out that Li2SiO3 can improve Li-ion diffusion behavior for better rate performance and that co-existing Li2CO3 favors the growth of a denser and more conductive SEI layer [30]. Li2SiO3 has also been synthesized in a graphene composite material with Li4Ti5O12 or Li2SnO3 [31,32]. Both anode composite materials with Li2SiO3 have better capacity and rate performance due to their lithium activity and good ionic conductivity.

Li2SiO3 was also found in lithiated SiO/SiOx-based anode materials and electrodes under both shallow and deep lithiation conditions [1,33,34]. Both Li4SiO4 and Li2SiO3 can be generated either by chemical lithiation with lithium foil or powder at 600 °C–800 °C (Figure 5a) or electrochemical lithiation within a half cell with a lithium metal. Since Li4SiO4 is an inert material for lithiation/delithiation and Li2SiO3 is active to Li+ ions with good reversibility, there should be reversible phases of Li-rich compounds formed after Li2SiO3 lithiation, which have not yet been identified. Wang et al. claimed that Li2SiO3 reacts with Li+ ions and generates Li2O and Si [32], but this claim needs further confirmation.

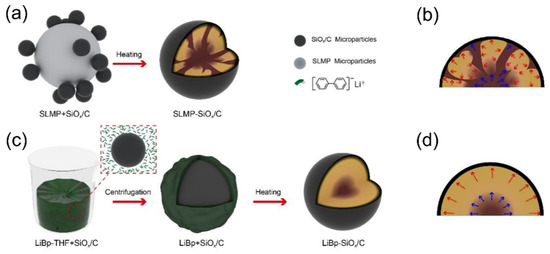

Figure 5.

Schematic drawing illustrating the synthesis process and internal stresses for (a,b) SLMP-SiOx/C and (c,d) LiBp-SiOx/C. Reproduced with permission from ref. [34]. Copyright 2020, ACS Publications.

Other than being generated in situ in electrochemical cells or via chemical lithiation processes with lithium metal, Li2SiO3 can be synthesized by using the hydrothermal method followed by a heat process [29,31,32]. First, silicon and LiOH are well mixed in a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 180 °C for an appropriate dwell time, and then the product is transferred to a furnace under inert gas and sintered at 600 °C–800 °C; as a result, pure Li2SiO3 can be obtained [29]. Hydrothermal synthesis using H2SiO3 as the starting material instead of silicon can also produce Li2SiO3 without post-heat treatments [35]. A few studies have reported that Li2SiO3 and byproduct Li2CO3 can be formed when Li4SiO4 reacts with CO2 gas [28,30]. A water-based sol-gel method adopting fumed silica and LiOH can produce Li2SiO3 and Li2CO3 at 500 °C, but Li4SiO4 is the only dominant phase if the intermediate is heated up to 675 °C [36]. Obviously, Li2SiO3 and Li4SiO4 are mutually convertible when Li2CO3 or CO2 is introduced into the thermal process.

3.3. Li2Si2O5

Li2Si2O5 was found as a result of characterizations of selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) under high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) with other lithium silicates (Li4SiO4 and Li6Si2O7) in an NaOH-etched SiO anode during electrochemical lithiation and delithiation [20]. All three lithium silicates were preserved, even when the Li metal half cell was discharged to 0 V [19,20]. Li2Si2O5 should be the lithium silicate phase formed in the early stage because of its low Li/Si ratio. However, only Li2Si2O5 disappeared, while Li4SiO4 and Li6Si2O7 remained after the cell was charged to 2 V. It was proposed that Li4SiO4 and Li6Si2O7 are irreversible phases in LIBs, but Li2Si2O5 can react with Si and then be converted into SiOx during delithiation [19,20,37] or react with additional Li+ ions to obtain Li2SiO3 and Si [15]. Another paper reporting a thin SiO2 film electrode utilized in LIBs showed that the lithiated product Li2Si2O5 has good cyclability and can be converted back to SiO2 at 3.0 V vs. Li/Li+ [38]. Lener et al. calculated the free energy for the lithiation reaction of silica and concluded that Li2Si2O5 is, thermodynamically, the most favorable lithium silicate product [39].

In addition to hydrothermal synthesis [40], Li2Si2O5 was able to be synthesized using carbon-coated SiOx (SiOx/C) microparticles and lithium-biphenyl (LiBp) complex solution, as shown in Figure 5c. In contrast to the lithiation method utilizing stabilized lithium metal power (SLMP) exhibited in Figure 5a, LiBp complex solution provides a homogeneous lithiation environment due to the intimate contact of SiOx/C with the Li-containing solution. Chemical lithiation that adopts SLMP, usually in several microns, can only offer point-to-point lithiation channels where the particles are in contact with each other (Figure 5a). The relatively inhomogeneous lithiation leads to randomly distributed LixSiyOz formation, resulting in strong internal stresses and thereby pulverization (Figure 5b). The LiBp-SiOx/C sample has a uniform Li2Si2O5 coating on the particle; thereby, much better cycle performance and internal stress control can be obtained (Figure 5d). Yan et al. attributed the formation of Li2Si2O5 to the homogeneous absorption of LiBp on the SiOx/C surface, which supports stable lithiation reactions, avoiding both excess and deficient lithium supply, as shown in the SLMP-SiOx/C sample processed by solid-state lithiation [34].

3.4. Li6Si2O7

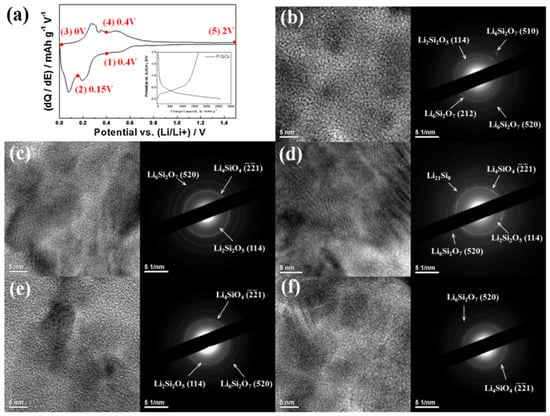

As mentioned above, Li6Si2O7 co-exists with Li2Si2O5 and Li4SiO4 in SiO/SiOX-based anodes during discharge and charge reactions [19,20]. Figure 6 explicitly displays the generation and transformation of lithium silicate phases at different delithiation and lithiation voltages [19]. At 0.4 V, Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 first appear in the anode, as shown in Figure 6b. When further discharged to 0.15 V, the porous SiOX anode starts to generate Li4SiO4, and both Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 remain in the anode structure until 0 V (Figure 6c,d). All three lithium silicates can be still observed when the cell is charged to 0.4 V (Figure 6e), which is a higher charge than that of the formation voltage of Li4SiO4. At a full charge of 2 V (exhibited in Figure 6f) Li2Si2O5 disappears, but Li6Si2O7 and Li4SiO4 cannot be delithiated and remain in the structure as the dominant phases. Li6Si2O7 is clearly an irreversible phase, like Li4SiO4, playing a role as a buffer material in SiO/SiOX-based anodes to alleviate their swelling behavior. It is worth noting that a reversible Li2SiO3 phase was not detected in the reports from the same research group [19,20,24], in contrast to the results of a later study [33]. A possible reason for this contradiction is that Li2SiO3 may be formed at a very early stage of lithiation and synchronously converted into Si and Li2O due to further lithiation [31,32].

Figure 6.

(a) Differential capacity plot (DCP) and charge/discharge profile of porous SiOx anode at the first cycle. Ex situ HRTEM images with SAED patterns of porous SiOx anode at various potentials indicated in DCP. (b) Discharge at 0.4 V, (c) discharge at 0.15 V, (d) discharge at 0 V, (e) charge at 0.4 V, and (f) charge at 2 V. Reproduced with permission from ref. [19]. Copyright 2013, Elsevier.

There are no studies in the literature reporting successful synthesis of sole Li6Si2O7 as the only lithium silicate phase. In the previous studies, Li6Si2O7 was synthesized, along with other lithium silicates, such as Li2SiO3 and Li4SiO4 [41,42]. Li6Si2O7 (15%) was produced with Li2SiO3 (40%) and Li4SiO4 (45%) by annealing a melt consisting of 60Li2O ⋅ 40SiO2 prepared at 1250 °C [41]. Mixed lithium silicate phases including Li6Si2O7 as impurities were obtained in an LTAP (Li1.3Ti1.7Al0.3(PO4)3) sample with an Li2O additive [43]. Li6Si2O7 as a minor phase can also be synthesized with Li4SiO4 using a sintering process of a Li2CO3 and SiO2 mixture between 750 °C and 850 °C [42]. However, the Li6Si2O7 phase vanishes when the heating temperature is increased to 900 °C. It was reported that Li6Si2O7 is a metastable lithium silicate phase, which can be decomposed into Li2SiO3 and Li4SiO4 at a high temperature [44].

4. Lithium Silicates in Silicon, Lithium Metal, and Other Anode Materials

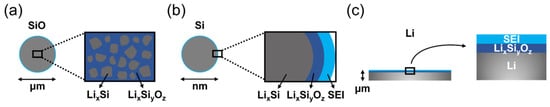

The success of lithium silicates in SiO/SiOX-based anodes has prompted researchers to investigate their use in high-capacity silicon and lithium metal anode systems. Both anodes have unsettled problems, such as dramatic volume change, unstable interfacial reactions, and poor cycle performance [45,46,47,48,49]. In a typical SiO anode, the lithium silicates formed in situ after the initial lithiation act as a rigid framework to accommodate the swelled LixSi alloy, and the lithium silicates in the structure can provide good ionic channels at the same time [11]. Figure 7 displays the common positional design of lithium silicates in SiO/SiOx, nano-Si, and lithium metal anode materials. Both SiO and nano-Si are in powder form, but only SiO possesses a structure with dispersed lithium silicates. On the other hand, lithium silicates are usually applied as a coating layer in nano-Si and metallic lithium anodes. Methods of applying lithium silicates in anode structures have been extensively developed. Below, we give some examples of how to employ lithium silicates in order to stabilize the electrochemical reactions of silicon and lithium metal anode materials, thereby prolonging their cycle life.

Figure 7.

Schematic drawing illustrating the lithium silicates (LixSiyOz) in the structure of (a) SiO/SiOx, (b) nano-Si, and (c) metallic lithium anode materials.

4.1. Lithium Silicates in Silicon Anodes

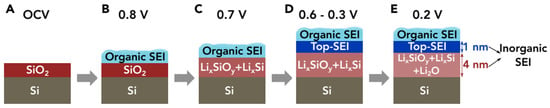

Cao et al. analyzed the composition of SEI formed on the native oxide-covered silicon anodes by employing in situ synchrotron X-ray reflectivity, linear sweep voltammetry, and ex situ XPS [16]. The inorganic SEI comprised two well-defined structures, which can be divided into a bottom SEI layer (adjacent to the electrode) and a top SEI layer (adjacent to the organic SEI layer from electrolyte decomposition), as shown in Figure 8. At open circuit voltage (OCV), the silicon surface is terminated by the pristine native silica (Figure 8A). While lithiation begins and the anode voltage drops to 0.8 V vs. Li/Li+, the organic SEI starts to form on the silicon anode, and native silica remains unchanged (Figure 8B). At 0.7 V, the lithiation of the native oxide layer initiates and transforms into lithium silicates (LixSiOy) [16,50,51] and lithium silicide alloys (LixSi) as the bottom SEI layer (Figure 8C). This finding is also in consistent with another report, which concluded that the lithiation voltage of SiO2 is higher than that of Si [14]. Between 0.6 V and 0.3 V, the top SEI, consisting of LiF and other products, is formed in between the organic SEI and bottom SEI, and lithiation of the bottom SEI continues (Figure 8D). At 0.2 V, the last step of SEI formation, Li2O is formed in the bottom SEI layer, which is thicker than the top SEI (Figure 8E). The authors concluded that a smooth LixSiOy layer as the bottom SEI can secure the growth of a conformal, smooth, and thin top SEI layer, and both cycle stability and rate performance can be guaranteed [16]. It was reported that Li4SiO4 should be the final lithium silicate product from the lithiation of either native oxide or artificial oxide grown on an Si surface, and a small lithiation current is necessary to activate the electrochemical synthesis of lithium silicates [23,52].

Figure 8.

(A–E) Schematic drawing illustrating the proposed voltage-dependent SEI growth mechanism on native oxide-terminated silicon anodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. [16]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier.

In addition to lithium-silicate-based SEI derived from native oxide, another approach to directly deposit lithium silicates onto silicon as an artificial SEI can be implemented for superior battery anode performance. Zhu et al. synthesized a Si@Li2SiO3 core-shell anode by oxidizing silicon nanoparticles at 600 °C in air with a subsequent thermal prelithiation process [53]. In comparison with the non-prelithiated Si@SiOx anode, Si@Li2SiO3 showed a much better initial Coulombic efficiency of 89.1% (vs. 66.5% in Si@SiOx and 56.8% in Si), indicating prelithiation treatment can minimize irreversible Li-ion consumption during SEI formation reactions. Cycling tests also revealed that Si@Li2SiO3 electrodes outperformed Si@SiOx and Si not only in specific capacity but also in cycling stability. The Li2SiO3 shell did slightly contribute to a charge/discharge capacity of 105.3/125.3 mA h g−1, which is consistent with the results of lithium activity discussed in the previous section [29]. The authors also demonstrated that the electron and Li-ion diffusion pathways of the Li2SiO3 layer on the Si surface are better than those of the SiOx layer by comparing their reaction resistances, leading to an outstanding rate capability [53].

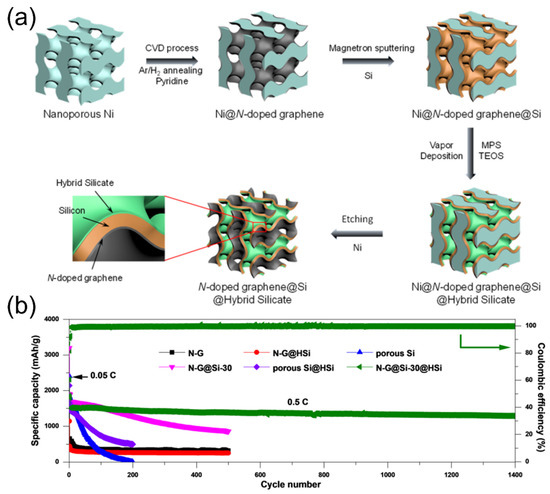

Huang et al. utilized nanoporous nickel as the substrate to be coated with N-doped graphene (via CVD process), silicon (via magnetron sputtering), and hybrid silicate (via vapor deposition) to build a sandwiched N-doped graphene@Si@hybrid silicate (N-G@Si@HSi) nanoarchitecture [54]. Figure 9a shows the step-by-step details of the fabrication process of the bicontinuous porous material. A hybrid silicate was derived from the reactions of 3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (MPS), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) precursors, and H2O vapors after a mild heating process. After the last nickel etching step, the free-standing film was used as the anode. The N-G@Si-30@HSi (Si-30: 59 nm silicon deposition thickness) exhibited extremely stable cycle performance among the other anode deigns in Figure 9b. In the ingenious sandwiched anode design, the N-doped graphene serves as a flexible and conductive support, and the porous silicon nanolayer can avoid severe volume expansion and pulverization [6,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The amorphous external coating of hybrid lithium silicates plays an important role to significantly enhance the robustness and integrity of the structure and to facilitate the formation of stable SEI films [54].

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic drawing illustrating the fabrication process of the nanoporous N-G@Si@HSi anode. (b) Cycling performance of the N-G, N-G@HSi, porous Si, N-G@Si-30, porous Si@HSi, and N-G@Si-30@HSi electrodes at 0.05 C for the initial three cycles and at 0.5 C for the extended cycles. Reproduced with permission from ref. [54]. Copyright 2020, ACS Publications.

4.2. Lithium Silicates in Lithium Metal Anodes

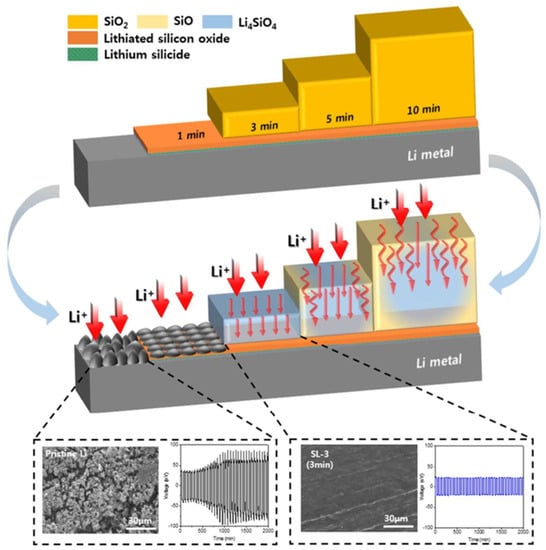

A Li4SiO4 passivation layer can be formed on lithium metal anodes by in situ reactions between lithium foil and the a-SiO2 thin film derived from electron cyclotron resonance (ECR)−chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [62]. Figure 10 exhibits the hierarchical structure of the composite lithium metal anode, which varies with a-SiO2 deposition time, which is proportional to the thickness of the passivation layer. Without any interfacial protection, a rough surface was clearly found in the pristine lithium anode after lithiation (bottom left in Figure 10), and severe voltage polarization worsened with increasing cycle numbers due to significant degradation of the ether-based electrolyte [63]. While a-SiO2 was deposited onto the lithium metal, a thin lithium silicide and lithiated silicon oxide bilayer was simultaneously generated by the immediate reactions with lithium. With a longer deposition time, pure a-SiO2 started to exist on top of the bilayer, and the thickness of a-SiO2 grew with the process time. After lithiation, the a-SiO2 top layer was converted into Li4SiO4, leading to a dendrite-free surface (SL-3 sample shown in the bottom of Figure 10), showing a flat plating/stripping voltage plateau with a minimal overpotential of 21.7 mV during repeated cycling, which represents excellent interfacial stability [62,64]. When the a-SiO2 layer became too thick, not only ionically conductive Li4SiO4 but also relatively insulating SiO was formed in the artificial top-layer structure, resulting in a higher overpotential due to the thicker protective layer’s longer Li-ion migration distance and poorer diffusivity due to a higher SiO/Li4SiO4 area ratio [62]. A few cracks were found in the lithium metal anode samples, particularly with a thicker a-SiO2 protective layer, due to the heavy electrical stress induced by high electrical resistance, thereby leading to high interfacial resistance [62,65]. As a result, owing to higher Li-ion conductivity and Young’s modulus (141.1 GPa) of Li4SiO4 than those of a-SiO2, a carefully designed Li4SiO4 artificial layer can serve as an excellent protective interface to stabilize the electrochemical reactions of lithium metal anodes [62].

Figure 10.

Schematic drawing illustrating the silicon oxide-based passivation layer deposited on the surface of lithium metal anode by the ECR-CVD method. Reproduced with permission from ref. [62]. Copyright 2018, ACS Publications.

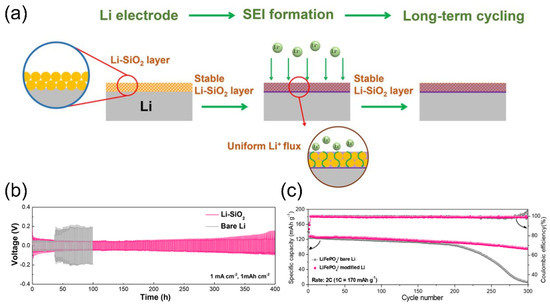

A similar approach was developed by applying a-SiO2 nanoparticles top of a lithium metal anode [66]. Silica spherical powders (200–300 nm in diameter) were sprayed onto a fresh lithium foil, followed by rolling-pressing to improve adherence. A compact and conformal SiO2 layer with a thickness of 3.6 μm then functioned as the artificial interfacial layer to stabilize the lithium-plating and stripping behaviors in lithium metal batteries (Figure 11a). The porous SiO2 layer transformed into Li4SiO4 after prelithiation, and zigzagged channels that can facilitate Li-ion transfer were formed between Li4SiO4 particles. This protective film remained integrated after extended cycles, which guarantees low polarization (Figure 11b) and great cycle performance (Figure 11c). Unlike previously mentioned continuous a-SiO2 film fabricated via the ECR-CVD method [62], a layer consisting of a-SiO2 powder has plenty of interstices, where SEI species, such as LiF, can infiltrate during initial formation cycles [66]. This Li4SiO4 hybrid structure possesses higher Young’s modulus (up to 8.81 GPa), lower Li-ion diffusion barrier, and flexibility to accommodate volume expansion [66]. Therefore, great cyclability and rate performance originating from stable interfacial reactions and enhanced charge-transfer kinetics can be obtained.

Figure 11.

(a) Schematic drawing illustrating the fabrication of a conformal Li4SiO4-based hybrid layer for the dendrite-proof metallic lithium anode. (b) Electrochemical cycling stability of bare Li and modified Li symmetric cells (1 mA cm−2, 1 mA h cm−2). (c) Long-term cycling performance of Li metal full cells. Reproduced with permission from ref. [66]. Copyright 2020, ACS Publications.

Liu et al. directly exposed a piece of lithium foil to MPS and TEOS vapors, and lithium silicates (LixSiyOz) were formed and bound with surface Li2O and LiOH, which were naturally generated on the lithium metal before vapor deposition [67]. It was reported that when the hydroxyl group on lithium reacts with TEOS, the protective film formed in situ possesses a self-healing feature that can dynamically repair the corroded metallic lithium anode, which, remarkably, improves its reversibility [68]. Since MPS and TEOS are both organosilicon compounds, methoxysilane (–Si–OCH3, from MPS) and ethoxysilane (–Si–OCH2CH3, from TEOS) can undergo hydrolysis and condensation reactions to create a hybrid organic–inorganic lithium silicate layer comprising a “soft” organic moiety (mercaptopropyl groups) and a “hard” inorganic moiety (lithium silicates) [67]. The soft part in the artificial layer can improve flexibility and robustness, and the hard part can enhance Li-ion transport and block the growth of lithium dendrite. Both organic and inorganic structures synergistically stabilize anode reactions of lithium metal during charge and discharge, leading to great cycle life in Li–LiFePO4 and Li–S full cells [67]. Ju et al. adopted aluminum silicate fibers to protect lithium metal anodes, realizing dendrite-free lithium anode reactions and a fast Li-ion conducting interface [69]. Inorganic species of lithium aluminates (LixAlOy) and lithium silicates (LixSiOy) were detected upon cycling, implying alternative metal silicates could also be used as precursors of artificial SEI for lithium metal anodes.

Liang et al. floated lithium metal foil on a solution of 3-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS) and LiOH, and Li6Si2O7 particles were adaptively embedded in the Si–O–Si polymer as a protective dual-phase layer during the initial lithium-stripping/plating process [70]. This dual-phase interface showed high elastic modulus, high mechanical rigidity, and high interface energy, which can suppress the formation of one-dimensional lithium dendrite whiskers [71]. Moreover, the structure of the composite shielding layer can efficiently lower the Li-ion migration barrier [72]. An Li–air battery with an adaptive polymer-inorganic hybrid structure on the lithium metal anode can perform up to 180 cycles in an air atmosphere (25 °C, 15% humidity) with a capacity limitation of 1000 mAh g−1 under a high current density of 1000 mA g−1 [70]. Yu et al. employed the self-healing protective film concept by not only treating lithium metal foil in TEOS as the anode but using TEOS as an additive in the electrolyte for film-forming purposes during cycling [68]. A thin lithium silicate layer can be formed under the reaction between TEOS and the detrimental corrosion products LiOH on the surface of lithium metal anodes in the highly corrosive environment of Li–O2 batteries. The shielded lithium metal anode with film-forming electrolyte additive gives Li–O2 batteries a considerable boost in cycle life (up to 144 cycles), indicating great dynamic-repair capability of the protective layer on the lithium metal anode [68].

Lithium silicates can also be used to serve as a bridge layer between lithium metal anodes and solid-state electrolytes to lower the interfacial resistance. To achieve a low interfacial resistance with lithium metal of the garnet solid electrolyte, an amorphous Li2SiO3 interlayer was proposed [73]. A liquid-phase coating process was utilized to deposit a thin lithium silicate film on the surface of garnet solid electrolytes, followed by a heat treatment, and metallic lithium was directly pressed onto the modified surface. This approach achieved stable cycling performance and a low interfacial resistance of 44 Ω cm2, which was more than 10 times lower than that of the uncoated solid electrolyte. The authors proposed a possible reaction mechanism whereby Li2SiO3 decomposed into Li21Si5 and Li2O after being in contact with lithium metal [73].

To sum up, there are many approaches using lithium silicates with various Li/Si ratios to improve anode performance in Li-ion and Li metal batteries. The majority of previous research focused on the Li4SiO4 protective coating on silicon and metallic lithium anodes. With a rational design of composite anode structure, unwanted interfacial reactions can be either suppressed or eliminated, leading to better performance of long cycle life and small overpotential. The swelling issue of Si-based anodes can be addressed by utilizing SiO anodes where lithium silicates are formed in situ during cell formation or by adopting a 3D framework to accommodate lithium silicate-protected silicon. Table 1 summarizes the previous works employing lithium silicates to boost battery anode performance. The studies related to modified metallic lithium anodes utilized excess lithium in the full cell. Without detailed full-cell design parameters, their specific capacity cannot be confirmed at this point. Still, other lithium silicate phases, such as Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7, have yet to be identified as a good anode-protection-layer material, like Li4SiO4 and Li2SiO3. As a result, additional in-depth research is required before a sound judgment can be reached.

Table 1.

Electrochemical performance of anode materials protected by lithium silicates.

5. Summary and Outlook

The properties of various lithium silicate phases have been carefully reviewed in this paper. Li4SiO4, regarded as the major compound among lithiated SiO anodes and SEI deposited on the naturally oxidized surface of Si anodes, is the most investigated lithium silicate material in battery applications. Li4SiO4 and Li2SiO3 are frequently used to protect high-capacity silicon and lithium metal anodes. Li2Si2O5 and Li6Si2O7 can also be found in some SiOx-based battery anodes after the lithiation process or during charge/discharge reactions. In general, lithium silicates play an important role in anodes for (1) stabilization of interfacial reactions, (2) buffering of volume expansion without any mechanical failure, and (3) offering fast Li-ion transportation pathways. Further systematic research is required to determine which lithium silicate phase is the best in class to protect silicon and lithium anode materials.

Lithium silicates can be synthesized by lithiation of amorphous silica or organosilicon compounds. The necessary raw materials are commonly seen in chemical engineering and semiconductor industries and are low-cost and easy to process, making this approach feasible and scalable for battery anode applications. A streamlined manufacturing process needs to be developed for better integration into current battery-production procedures. Aside from the success of SiO/SiOx anode materials, lithium silicates have now been successfully adopted in high-capacity anode systems, especially serving as the major ingredient in the protection layer of metallic lithium. Alternative lithium metal oxide compounds could be developed if comparable ionic and mechanical properties can be obtained. Due to the rigid nature of ceramics-like oxide-based ion-conducting materials that might lose intimate contact with the active anode material during cycling, a polymer-inorganic (soft-rigid) hybrid protection layer appears to be a promising option for achieving both high elasticity and ionic conductivity to shield silicon and lithium metal anodes [67,70].

Currently, the lithium silicates adopted in commercial battery systems are mostly formed during the lithiation process of SiO anodes at the formation step of battery-cell manufacturing. The challenges of lithium silicate-enhanced anodes are: (1) The efficacy of anode protection by lithium silicates synthesized from silica or other organosilicon compounds other than SiO is still not clear at the industry level; (2) The processing and preparation of lithium silicate protective layers could be cost-ineffective; (3) The long-term protection and adhesion stability of lithium silicates in integrated anodes is unknown. Strategies concerning smart architectural designs, innovative methods of anode integration processes, low-cost and scalable synthesis, and long-cycle durability improvements will need to be thoroughly investigated before lithium silicates can be widely applied in various anode systems for practical Li-ion and Li metal batteries.

Author Contributions

Y.-S.S. drafted the majority of this review paper. K.-C.H., P.S. and J.-Y.H. were involved in the editing and literature-screening efforts. All authors participated in writing the manuscript and discussing the contents to be included in this review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan (110-2113-M-A49-027-MY2) and by the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Taiwan under the Yushan Young Scholar Program (110B53-8) and the Higher Education SPROUT Project of the National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (110W266).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All collected data are presented in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yamamura, H.; Nobuhara, K.; Nakanishi, S.; Iba, H.; Okada, S. Investigation of the Irreversible Reaction Mechanism and the Reactive Trigger on SiO Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Battery. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 119, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, G.; Chen, C.; Jiao, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D.; Dong, A. An Affordable Manufacturing Method to Boost the Initial Coulombic Efficiency of Disproportionated SiO Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. J. Power Sources 2019, 426, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, A.; Wieder, T.; van Aken, P.A.; Weirich, T.E.; Denninger, G.; Vidal, M.; Oswald, S.; Deneke, C.; Mayer, J.; Fuess, H. An Interface Clusters Mixture Model for the Structure of Amorphous Silicon Monoxide (SiO). J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 320, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Park, C.-M.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Sohn, H.-J. Electrochemical Behavior of SiO Anode for Li Secondary Batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2011, 661, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Su, X. Recent Advancement of SiOx Based Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2017, 363, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Zhong, L.; Huang, S.; Mao, S.X.; Zhu, T.; Huang, J.Y. Size-Dependent Fracture of Silicon Nanoparticles During Lithiation. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Zhu, B.; Lu, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhu, J. Challenges and Recent Progress in the Development of Si Anodes for Lithium-Ion Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, M.; He, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, C. Nanoscale Silicon as Anode for Li-Ion Batteries: The Fundamentals, Promises, and Challenges. Nano Energy 2015, 17, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, K.; Zou, F.; Canova, M.; Zhu, Y.; Kim, J.-H. Systematic Electrochemical Characterizations of Si and SiO Anodes for High-Capacity Li-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 413, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, A.; Kohara, S.; Asada, T.; Arao, M.; Yogi, C.; Imai, H.; Tan, Y.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M. Atomic-Scale Disproportionation in Amorphous Silicon Monoxide. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; He, R.; Xu, M.; Feng, S.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Mai, L. Silicon Oxides: A Promising Family of Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Lee, M.J.; Oh, S.M.; Kim, J.J. Fading Mechanisms of Carbon-Coated and Disproportionated Si/SiOx Negative Electrode (Si/SiOx/C) in Li-Ion Secondary Batteries: Dynamics and Component Analysis by TEM. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 85, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.C.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, Y.-K. Atomic-Level Understanding toward a High-Capacity and High-Power Silicon Oxide (SiO) Material. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivonxay, E.; Aykol, M.; Persson, K.A. The Lithiation Process and Li Diffusion in Amorphous SiO2 and Si from First-Principles. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynier, Y.; Vincens, C.; Leys, C.; Amestoy, B.; Mayousse, E.; Chavillon, B.; Blanc, L.; Gutel, E.; Porcher, W.; Hirose, T.; et al. Practical Implementation of Li Doped SiO in High Energy Density 21700 Cell. J. Power Sources 2020, 450, 227699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Abate, I.I.; Sivonxay, E.; Shyam, B.; Jia, C.; Moritz, B.; Devereaux, T.P.; Persson, K.A.; Steinrück, H.-G.; Toney, M.F. Solid Electrolyte Interphase on Native Oxide-Terminated Silicon Anodes for Li-Ion Batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 762–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirose, T.; Morishita, M.; Yoshitake, H.; Sakai, T. Study of Structural Changes That Occurred during Charge/Discharge of Carbon-Coated SiO Anode by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Solid State Ion. 2017, 303, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Ju, Z.; Lu, G.; Sheng, O.; Nai, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; et al. Silicious Nanowires Enabled Dendrites Suppression and Flame Retardancy for Advanced Lithium Metal Anodes. Nano Energy 2021, 82, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.-C.; Hwa, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Sohn, H.-J. A New Approach to Synthesis of Porous SiOx Anode for Li-Ion Batteries via Chemical Etching of Si Crystallites. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 117, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.-C.; Hwa, Y.; Park, C.-M.; Sohn, H.-J. Reaction Mechanism and Enhancement of Cyclability of SiO Anodes by Surface Etching with NaOH for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T.; Morishita, M.; Yoshitake, H.; Sakai, T. Investigation of Carbon-Coated SiO Phase Changes during Charge/Discharge by X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure. Solid State Ion. 2017, 304, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.; Apblett, C.; Brumbach, M.; Ohlhausen, J.; Stoldt, C. Structural and Compositional Characterization of RF Magnetron Cosputtered Lithium Silicate Films: From Li2Si2O5 to Lithium-Rich Li8SiO6. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2017, 35, 061509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, B.; Dedryvère, R.; Allouche, J.; Lindgren, F.; Gorgoi, M.; Rensmo, H.; Gonbeau, D.; Edström, K. Nanosilicon Electrodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Interfacial Mechanisms Studied by Hard and Soft X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-S.; Park, C.-M.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-U.; Jeong, G.; Sohn, H.-J. Quartz (SiO2): A New Energy Storage Anode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluchamy, A.; Doh, C.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, D.-J.; Ha, K.-H.; Shin, H.-M.; Jin, B.-S.; Kim, H.-S.; Moon, S.-I.; et al. Improvement of Cycle Behaviour of SiO/C Anode Composite by Thermochemically Generated Li4SiO4 Inert Phase for Lithium Batteries. J. Power Sources 2009, 188, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, C.-H.; Veluchamy, A.; Oh, M.-W.; Han, B.-C. Analysis on the Formation of Li4SiO4 and Li2SiO3 through First Principle Calculations and Comparing with Experimental Data Related to Lithium Battery. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Shi, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lu, T.; Huang, W. A Facile Approach to Fabricate Li4SiO4 Ceramic Pebbles as Tritium Breeding Materials. Mater. Lett. 2015, 159, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, P. Synthesis of Macroporous Li4SiO4 via a Citric Acid-Based Sol–Gel Route Coupled with Carbon Coating and Its CO2 Chemisorption Properties. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 2990–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Miao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H. Synthesis of Graphene Supported Li2SiO3 as a High Performance Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 444, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Gong, Y.; Lu, T.; Luo, C.; Yan, K. Enhanced Electrochemical Performance and Decreased Strain of Graphite Anode by Li2SiO3 and Li2CO3 Co-Modifying. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 223, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Miao, J.; Lu, M.; Wen, T.; Sun, J. Graphene Supported Li2SiO3/Li4Ti5O12 Nanocomposites with Improved Electrochemical Performance as Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 403, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Miao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z. Synthesis of Graphene Supported Li2SiO3/Li2SnO3 Anode Material for Rechargeable Lithium Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom, J.H.; Hwang, S.W.; Cho, S.M.; Yoon, W.Y. Improvement of Irreversible Behavior of SiO Anodes for Lithium Ion Batteries by a Solid State Reaction at High Temperature. J. Power Sources 2016, 311, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.-Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.-F.; Yin, Y.-X.; Zhang, C.-J.; Jiang, K.-C.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.-L.; Guo, Y.-G. Enabling SiOx/C Anode with High Initial Coulombic Efficiency through a Chemical Pre-Lithiation Strategy for High-Energy-Density Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 27202–27209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemi, A.; Khademinia, S.; Sertkol, M. Part III: Lithium Metasilicate (Li2SiO3)—Mild Condition Hydrothermal Synthesis, Characterization and Optical Properties. Int. Nano Lett. 2015, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Wen, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Li4SiO4 Nano-Powders by a Water-Based Sol-Gel Process. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 392, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zeng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zeng, C.; Gu, J.; Feng, X.; He, H. Fabrication and Lithium Storage Performance of Sugar Apple-Shaped SiOx@C Nanocomposite Spheres. J. Power Sources 2015, 288, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Z.-W. Lithium Electrochemistry of SiO2 Thin Film Electrode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 3774–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lener, G.; Otero, M.; Barraco, D.E.; Leiva, E.P.M. Energetics of Silica Lithiation and Its Applications to Lithium Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 259, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alemi, A.; Khademinia, S.; Sertkol, M. Lithium Disilicate (Li2Si2O5): Mild Condition Hydrothermal Synthesis, Characterization and Optical Properties. J. Nanostruct. 2014, 4, 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva, O.N.; Shtenberg, M.V.; Khvorov, P.V. Vibrational Spectroscopic and X-Ray Diffraction Study of Crystalline Phases in the Li2O-SiO2 System. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 59, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Cao, Y.D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, W.J.; Wu, D.P.; Shen, L. Fabrication of Lithium Silicate Doped with Lithium Titanate by Solid-State Reaction and Its XRD Study. AMR 2012, 624, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihandoko, B.; Sardjono, P.; Zulfia, A.; Siradj, E. The effect of Li2O on composite LTAP and windows glasses. Indones. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 9, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Piazza, G.; Reimann, J.; Günther, E.; Knitter, R.; Roux, N.; Lulewicz, J.D. Behaviour of Ceramic Breeder Materials in Long Time Annealing Experiments. Fusion Eng. Des. 2001, 58–59, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Lott, A.; Lu, W.; Sheldon, B.W.; Wu, J. Silicon-Based Nanomaterials for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014, 4, 1300882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Zhu, J.; Müller-Buschbaum, P.; Cheng, Y.-J. Silicon Based Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes: A Chronicle Perspective Review. Nano Energy 2017, 31, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-B.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Zhang, Q. Toward Safe Lithium Metal Anode in Rechargeable Batteries: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10403–10473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y. Reviving the Lithium Metal Anode for High-Energy Batteries. Nat. Nanotech. 2017, 12, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-B.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Wei, F.; Zhang, J.-G.; Zhang, Q. A Review of Solid Electrolyte Interphases on Lithium Metal Anode. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, B.; Dedryvère, R.; Gorgoi, M.; Rensmo, H.; Gonbeau, D.; Edström, K. Improved Performances of Nanosilicon Electrodes Using the Salt LiFSI: A Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9829–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.W.; Celio, H.; Webb, L.J.; Stevenson, K.J. Examining Solid Electrolyte Interphase Formation on Crystalline Silicon Electrodes: Influence of Electrochemical Preparation and Ambient Exposure Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 19737–19747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, G.; Saeed, T.; Liu, Y.; Kaczmarek, S.E.; Lu, W.; Wu, Q. Investigations on the Effect of Current Density on SiO/Si Composite Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 393, 139072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhou, J.; Cai, W.; Lu, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, S.; Fu, Q.; Qian, Y. Prelithiated Surface Oxide Layer Enabled High-Performance Si Anode for Lithium Storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 18305–18312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Han, J.; Lu, Z.; Wei, D.; Kashani, H.; Watanabe, K.; Chen, M. Ultrastable Silicon Anode by Three-Dimensional Nanoarchitecture Design. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4374–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, W.; Gao, B.; Mei, S.; Xiang, B.; Fu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chu, P.K.; Huo, K. Scalable Synthesis of Ant-Nest-like Bulk Porous Silicon for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ge, M.; Fang, X.; Rong, J.; Zhou, C. Review of Porous Silicon Preparation and Its Application for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 422001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Rong, J.; Fang, X.; Zhang, A.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, C. Scalable Preparation of Porous Silicon Nanoparticles and Their Application for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Nano Res. 2013, 6, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Rong, J.; Fang, X.; Zhou, C. Porous Doped Silicon Nanowires for Lithium Ion Battery Anode with Long Cycle Life. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2318–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zheng, J.; Song, J.; Luo, L.; Yi, R.; Estevez, L.; Zhao, W.; Patel, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.-G. A Novel Approach to Synthesize Micrometer-Sized Porous Silicon as a High Performance Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Gu, M.; Yang, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Dai, F.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Inward Lithium-Ion Breathing of Hierarchically Porous Silicon Anodes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhai, T.; Zhou, H. Hierarchical Micro/Nano Porous Silicon Li-Ion Battery Anodes. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, A.-Y.; Liu, G.; Woo, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.K. Li4SiO4-Based Artificial Passivation Thin Film for Improving Interfacial Stability of Li Metal Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 8692–8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieker, G.; Winter, M.; Bieker, P. Electrochemical in Situ Investigations of SEI and Dendrite Formation on the Lithium Metal Anode. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 8670–8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, H.-K.; Woo, S.-G.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.-R.; Kim, Y.-J. Conductive Porous Carbon Film as a Lithium Metal Storage Medium. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, D.-H.; Yang, D.-G. Thick SiO2 Films Obtained by Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition Using Hexamethyldisilazane, Carbon Dioxide, and Hydrogen. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C. Rational Tuning of a Li4SiO4-Based Hybrid Interface with Unique Stepwise Prelithiation for Dendrite-Proof and High-Rate Lithium Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 39362–39371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xiao, Q.; Wu, H.B.; Shen, L.; Xu, D.; Cai, M.; Lu, Y. Fabrication of Hybrid Silicate Coatings by a Simple Vapor Deposition Method for Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yin, Y.-B.; Ma, J.-L.; Chang, Z.-W.; Sun, T.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Yang, X.-Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.-B. Designing a Self-Healing Protective Film on a Lithium Metal Anode for Long-Cycle-Life Lithium-Oxygen Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Jin, C.; Yuan, H.; Yang, T.; Sheng, O.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhang, W.; et al. A Fast-Ion Conducting Interface Enabled by Aluminum Silicate Fibers for Stable Li Metal Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 128016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Lian, F.; Meng, N.; Lu, J.; Ma, L.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Zhang, Q. Adaptive Formed Dual-Phase Interface for Highly Durable Lithium Metal Anode in Lithium-Air Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.M.; Mullin, S.A.; Teran, A.A.; Hallinan, D.T.; Minor, A.M.; Hexemer, A.; Balsara, N.P. Resolution of the Modulus versus Adhesion Dilemma in Solid Polymer Electrolytes for Rechargeable Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, A222–A227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, F.; Appetecchi, G.B.; Persi, L.; Scrosati, B. Nanocomposite Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Nature 1998, 394, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Navarro, N.C.; Kajiura, R.; Jalem, R.; Tateyama, Y.; Miura, A.; Tadanaga, K. Significant Reduction in the Interfacial Resistance of Garnet-Type Solid Electrolyte and Lithium Metal by a Thick Amorphous Lithium Silicate Layer. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 5533–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).