Abstract

The increasing demand for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) has intensified the need for efficient lithium (Li) recovery from secondary sources. This study focuses on anti-solvent crystallization for the recovery of high-purity lithium hydroxide monohydrate (LiOH·H2O) from a Li-rich leachate, derived from the flue dust of a pilot-scale pyrometallurgical process for LIB material recycling. To optimize product yield and purity, a series of experiments were performed, focusing on the influence of parameters such as solvent type, organic-to-aqueous (O/A) volumetric ratio, crystallization time, stirring rate, and anti-solvent addition rate. Acetone was identified as the most effective anti-solvent, producing rectangular cuboid crystals with approximately 90% Li recovery and around 95% purity, under optimized conditions (O/A = 4, 3 h, 150 rpm, and solvent flow rate of 5 mL/min). The flow rate influenced crystal morphology and impurity entrapment, with 5 mL/min favoring nucleation-dominated crystallization regime, producing ~20 μm of well-dispersed crystals with reduced impurity incorporation. SEM-EDS, surface washing, and gradual dissolution of obtained LiOH·H2O crystals revealed that the impurities sodium (Na), potassium (K), aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca) and chromium (Cr) were crystallized as conglomerates. It was found that Na, K, Al, and Ca primarily crystallized as highly soluble conglomerates, while Cr was crystallized as a lowly soluble conglomerate impurity. In contrast Zn was distributed throughout the crystal bulk, suggesting either the entrapment of soluble zincate species within the growing crystals or the formation of mixed Li-Zn phase. Therefore, to achieve battery-grade purity, further purification measures are necessary.

1. Introduction

The increasing global demand for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), particularly for battery electric vehicles (BEVs), has led to a significant rise in lithium (Li) consumption [1,2]. Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) and lithium hydroxide monohydrate (LiOH·H2O) are the primary Li compounds used as precursors in the production of NMC (nickel (Ni), manganese (Mn), cobalt (Co)) batteries that predominate the market [3]. However, LiOH·H2O has gained preference over Li2CO3, due to its ability to facilitate more efficient cathode synthesis at lower temperatures (650–700 °C compared to 850–900 °C for Li2CO3) [3,4]. Lower-temperature synthesis enhances battery performance, extends life span, and improves safety. As a result, the demand for LiOH·H2O is expected to surpass that of Li2CO3 in future [5].

To fulfill the rising demand of LiOH·H2O for battery manufacturing, spent LIBs have emerged as a key secondary source. Various combined pyro- and hydrometallurgical recycling flowsheets have been explored to extract Li as LiOH·H2O using thermal treatment followed by water leaching. Among these, reduction roasting using hydrogen has shown significant promise for converting Li in the cathode into lithium oxide (Li2O(s)), which when leached with water, forms a LiOH slurry with a recovery efficiency exceeding 95%. To recover LiOH·H2O from the slurry, evaporative crystallization is typically employed. This process enables relatively fast crystal growth; however, achieving battery-grade purity requires multiple washing, filtration, and recrystallization steps [6,7]. These additional purification stages may increase energy consumption and process complexity and depending on the operating conditions, may reduce the economic viability of the process [8].

An alternative approach is anti-solvent crystallization, which promotes crystal formation by the addition of water-miscible organic solvents such as ethanol or acetone to a supersaturated solution [9,10]. The addition of anti-solvent creates a competition between organic molecules and inorganic ions of the water molecules. Organic molecules with polar functional groups preferentially form strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules, thereby shielding the solubilizing interactions between water and inorganic ions, effectively reducing water activity and promoting crystallization [11]. Anti-solvent crystallization can achieve high crystallization yields typically at room temperature [12]. However, a separate solvent recovery step, such as distillation, is required post-crystallization, which can contribute significantly to the overall energy consumption of the process [13].

Anti-solvent crystallization is widely applied in the pharmaceutical industry to control the size, shape and crystalline form of drug compounds [14,15]. In recent years, this technique has been increasingly explored for the selective crystallization of salts, such as the recovery of high-purity potash from the hydrochloric acid leaching solution of K-Feldspar [11]; scandium fluoride from ammonium fluoride strip liquors [16,17,18]; Ni, Mn, and Co citrates from the citric acid leaching solution of NMC batteries [19]; Ni and Co sulfate from sulfuric acid leaching [20]; and the recovery of metal tartrates from NMC leachates of deep eutectic solvent (DES) [21]. The method has also been studied for LiOH·H2O crystallization using ethanol as an anti-solvent. The aqueous solution prepared with 11% by weight LiOH·H2O was subjected to anti-solvent crystallization using 70 and 90% ethanol under controlled conditions. Three different alcohol addition rates of 7, 30 and 60 cm3/min were tested, but variation of these parameters showed negligible effects on the recovery and crystal size of LiOH·H2O [22]. Although the study shows the feasibility of recovering LiOH·H2O via anti-solvent crystallization, it did not explore how impurities, particularly those from spent LIBs, affect crystal morphology and purity, highlighting an important gap in research.

The presence of impurity ions during crystallization can interact with different surfaces of the crystal, influencing the purity and morphology of growing crystals [23,24]. Understanding the mechanisms by which impurities incorporate into crystals is critical for producing high-purity LiOH·H2O. Impurities can enter the crystallized solids through several mechanisms: (i) entrapment of mother liquor as agglomerates and inclusions, (ii) lattice incorporation to form co-crystals, (iii) deposition or absorption to the crystal surface, (iv) solid solution formation or (v) conglomerate formation [25]. Co-crystal formation is a thermodynamically driven process; if a co-former impurity is present under suitable conditions, the discrete phase will form independently of the process conditions. Solid solution formation is also thermodynamically driven but is more sensitive to crystallization conditions. Therefore, impurities that can form co-crystals or enter solid solutions require removal prior to crystallization [26].

While research on impurity incorporation in metal crystallization is limited, some studies have examined the impact of impurities such as sodium (Na), potassium (K), chlorine (Cl) and magnesium (Mg) for Li2CO3 crystallization from brines [27,28]. However, research to date has not explored the impact of inorganic impurities on LiOH·H2O crystallization, making it an important area of further research.

On the contrary, impurity incorporation mechanisms have been extensively studied in the pharmaceutical industry, where a structured approach has been developed to identify mechanisms responsible for poor impurity rejection during crystallization. The workflow developed by Urwin et al. includes (i) microscopic imaging of the isolated crystals, ruling out or confirming agglomeration as a method of impurity inclusion, (ii) surface washing experiments to differentiate kinetically adsorbed or thermodynamically incorporated impurities, (iii) stepwise crystal dissolution, providing insights into limits of purification efficiency, and (iv) binary phase diagrams to analyze the behavior of crystals and impurities, revealing solid state interactions and phase behaviors [26]. However, this workflow does not account for conglomerate systems, which during stepwise crystal dissolution could exhibit behavior ranging from solid solution to surface deposition, depending on their solubilities. The workflow therefore was revised by [25] to provide a more comprehensive understanding of impurity incorporation mechanisms.

This study investigates the anti-solvent crystallization of LiOH·H2O from the pregnant leaching solution (PLS) of a flue dust. The flue dust, generated during pyrometallurgical processing of spent NMC batteries [29], was leached in limewater, yielding LiOH (aq) along with dissolved impurities such as Na, K, sulfur (S), calcium (Ca), aluminum (Al), zinc (Zn), and chromium (Cr) [30]. The key research questions addressed in this work are as follows: What is the effectiveness of selected anti-solvents in crystallizing LiOH·H2O from the leachate? What are the mechanisms by which certain impurities incorporate into the LiOH·H2O crystal? What measures can be taken to improve impurity rejection to industrially acceptable levels? To address these questions a comprehensive investigation was carried out, involving screening tests, parameter optimization with the chosen anti-solvent, and mechanistic studies of impurity incorporation by employing the revised workflow developed by [25]. This also includes crystallization kinetics and thorough characterization of solid and aqueous samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The chemical composition of the PLS used in this study is presented in Table 1. In the study organic solvents such as ethylene glycol (99%) and ethyl acetate (99.5%) from Sigma Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA), acetone (100%) and absolute ethanol (99.5%) from VMR Chemicals (Randor, PA, USA), and isopropanol (99.5%) from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) were employed.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the PLS, calculated based on ICP-OES data.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Organic Solvent Screening

The choice of an organic solvent is a critical step for achieving high recovery of the targeted metal salt during anti-solvent crystallization. The selection process, guided by several key factors [9], is as follows:

- Dielectric constant: A low dielectric constant decreases the activity of water, which directly influences the solubility and crystallization efficiency.

- Viscosity: Moderate viscosity ensures smooth handling in downstream processes, such as filtration and product washing.

- Chemical Stability: The solvent must be unreactive with components in the aqueous phase to prevent undesirable side reactions.

- Electrochemical inertness: The solvent EH–pH window should be equal to or wider than water.

- Boiling point and heat of vaporization: A normal boiling point and specific heat of vaporization, typically lower than water to reduce energy consumption during liquid–liquid separation.

Five anti-solvents—namely ethanol, isopropanol, acetone, ethylene glycol, and ethyl acetate—were selected for screening tests. The properties of these anti-solvents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specifications of organic solvents selected for screening tests for LiOH·H2O crystallization. The data to generate this table is extracted from [9,31] for 25 °C.

The screening experiments were conducted in an incubated shaker (Thermo MaxQ 4000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) under controlled conditions for 72 h. The temperature and stirring rate in the screening tests were kept constant at 25 °C and 150 rpm, respectively. For each test, 20 mL of leachate was mixed in a single step with the tested anti-solvent. To evaluate the effect of solvent volume, anti-solvent crystallization was performed at two different organic-to-aqueous (O/A) volumetric ratios of 3 and 6. Each screening test was conducted in duplicate to ensure consistency.

At the end of the screening experiments, the supernatants were sampled, filtered through 0.45 µm nylon syringe filters, and preserved directly in 2% HNO3 solution. The preserved samples were diluted 100-fold and analyzed for their residual content using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, Model: Thermo-Scientific ICAP 7200 DUO, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Following sample collection, the solution was filtered, and the crystals were collected and preserved for further analysis. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on the crystals using Zeiss Gemini Merlin Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Baden Wuttemberg, Germany). For imaging, a thin layer of crystals was mounted on an adhesive carbon tape and an acceleration voltage of 10 kV and emission current of 300 pA was used, while for EDS they were set to 20 kV and 1 nA.

2.2.2. Crystallization Kinetics

The crystallization kinetics encompassing nucleation and growth are directly influenced by the degree of supersaturation. Supersaturation () is defined as the difference between the chemical potential of the solute in the supersaturated and the saturated state [32]. For non-ideal solutions the is calculated using Equation (1) [33]:

where and are mole fractions and and are activity coefficients at supersaturated and saturated state, respectively. To calculate supersaturation, the activity coefficient values of water and PLS components were obtained using the Equilibrium module of HSC Chemistry 10 (Metso Finland Oy, Espoo, Finland), which employed the Pitzer model for its calculation. The rate of nucleation was evaluated based on the classical nucleation theory using Equation (2) [11]:

In this expression, , , , , and are pre-exponential factors, surface free energy, Boltzmann’s constant, temperature and supersaturation, respectively. The crystal growth during anti-solvent crystallization was evaluated using the diffusion–surface reaction model as expressed by Equation (3) [11]:

where is the overall mass transfer for the growth and its value lies between m/s and is the growth parameter which is typically 1.0.

2.2.3. Optimization of O/A Ratio, Crystallization Time and Stirring Rate

Following the screening tests, experiments were carried out for optimizing the O/A ratio, crystallization time, and stirring rate using the selected anti-solvent. All experiments were conducted at 25 °C in an incubated shaker and in each case, the anti-solvent was mixed with the PLS in a single step.

For O/A ratio optimization, the anti-solvent was added to the PLS at O/A volumetric ratios of 1:5, 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 5:1 for 72 h at a constant stirring rate of 150 rpm. After completion, supernatants were sampled, diluted 100-fold and analyzed for their chemical content using ICP-OES. The experiments were conducted in duplicate to ensure reproducibility.

To investigate the effect of crystallization time, experiments were conducted at the optimal O/A ratio at a stirring rate of 150 rpm. Samples were collected at 0.16 h, 0.33 h, 0.66 h, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, diluted and analyzed as described previously. Three parallel experimental setups were employed, with samples taken from alternating setups to minimize disturbance. The three parallel experiments were considered as a single set of data, and the entire process was repeated to ensure reproducibility.

Finally, the effect of the stirring rate was evaluated in duplicate experiments at an optimal O/A ratio and crystallization time by varying the stirring rate to 150, 200, 250, and 300 rpm. After completion, supernatants were sampled, diluted, and analyzed for their chemical content.

2.2.4. Supersaturation Control Through Anti-Solvent Addition Rate

After determining the optimal O/A ratio, crystallization time, and stirring rate, experiments were conducted with the controlled addition of anti-solvent to the PLS. The degree of supersaturation is influenced by changing the addition rate, which in turn can affect crystallization yield, impurity rejection and morphology of the crystals.

To study these effects, experiments were carried out using the Easy Max 402 Synthesis Workstation equipped with Easy Viewer 100 particle analyzer probe (Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). The system includes a 400 mL glass reactor, pitch-blade glass propellor Ø 38 mm, thermometer, and an SP50 dosing unit (Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). The experiments were conducted in duplicate at the previously optimized O/A ratio, crystallization time, and stirring rate, at a temperature of 25 °C.

Owing to the size limitations of the reactor and the necessity for the particle analyzer probe to remain submerged in the solution, 50 mL of the anti-solvent was initially mixed with 50 mL of the PLS, before addition to the reactor. The effect of the addition rate of the remaining anti-solvent was then examined at flow rates of 2.5 mL/min, 5 mL/min, 7.5 mL/min, 10 mL/min, and 12.5 mL/min. The number and size of particles were monitored every 10 s using the Easy Viewer 100 particle analyzer. The analyzer detects particles passing under the laser beam, However, given the system agitation, the measurements of the number and size of crystals were considered representative for the entire system. At the conclusion of each experiment, solids were filtered, and supernatants were sampled and analyzed by ICP-OES to determine crystallization yield and impurity incorporation. The crystals of LiOH·H2O were dried in a vacuum desiccator. A 0.304 g portion of high LiOH·H2O yield and effective impurity rejection was digested in 20 mL of aqua regia at 100 °C for 90 min. The resulting solution was diluted 100, 1000, and 2000 times with 2% HNO3 and then analyzed by ICP-OES for chemical content. The remaining crystals were further analyzed using SEM-EDS.

2.2.5. Diagnosis of Impurity Incorporation Mechanisms

In this study, the diagnostic workflow was followed to investigate impurity incorporation in high-purity crystals obtained under a controlled anti-solvent addition rate.

Microscopic Imaging for Agglomeration Assessment: To evaluate agglomeration, crystals were examined using SEM imaging. The lack of evidence for free-flowing crystals during this stage would suggest that impurity-rich mother liquor might have been trapped in the bridge between agglomerated crystalline particles and might be the cause of impurity incorporation within the crystals. In this case, anti-agglomeration strategies such as selecting a different solvent, reducing the degree of supersaturation or changing fluid dynamic conditions should be considered [34,35]. Conversely, if the SEM images confirm the presence of free-flowing crystals, agglomeration can be ruled out as a primary mechanism for impurity incorporation.

Surface washing of crystals: If agglomeration is not responsible, the next diagnostic step involves surface adsorption of impurities. This was investigated by slurry experiments and around 0.4 g of crystals were suspended in 60 mL of saturated LiOH·H2O impurity-free anti-solvent and agitated at 150 rpm for 12 h at 25 °C in an incubated shaker. At the end of the slurry experiment, the solution was filtered, and supernatant was sampled, diluted to be analyzed by ICP-OES. If >50% of the impurity is removed by this method, surface adsorption could be the primary mechanism of impurity incorporation.

Impurity Mapping through Gradual Dissolution of Crystals: The location and nature of impurity incorporation were further studied in controlled dissolution experiments, conducted in duplicate for reproducibility. Approximately 0.9 g of crystals were suspended in 80 mL of pure anti-solvent and subjected to dissolution in an incubated shaker at 150 rpm for 30 min. Milli-Q water (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA) was incrementally added to induce gradual dissolution of crystals. The dissolution profile of bulk crystals was then correlated with the concentration of impurities released at each stage. This approach makes it possible to qualitatively determine whether impurities are located as conglomerates (high- and low-solubility), embedded as inclusions within the crystal matrix (growth and attrition induced), or incorporated as solid solution.

Solubility Profile of Impurity Salts in Acetone–Water Mixtures: To isolate conglomerate effects from other incorporation mechanisms during stepwise dissolution, the solubility of impurities ranging from surface-deposited to those forming solid solutions was measured individually under the same solvent compositions used in the stepwise experiments. Since the anticipated crystallized impurities are hydroxide, zinc hydroxide (Fluorochem) was used for solubility measurements. An excess amount of the salt was introduced into its respective solvent and agitated at 150 rpm for 12 h at 25 °C in an incubated shaker. Following equilibrium, the suspensions were filtered, and aliquots were collected, diluted as necessary, and analyzed by ICP-OES.

3. Results

3.1. Organic Solvent Screening

Table 3 presents the results of organic solvent screening tests conducted at O/A ratios of 3 and 6. The results depict that ethyl acetate facilitated the removal of 100% of Li from the aqueous phase. However, it also extracted nearly 100% of impurities at both tested O/A ratios, demonstrating poor selectivity for Li. Moreover, the addition of ethyl acetate did not result in the formation of clean crystals, instead hydrated gel-like precipitate was formed, reducing its suitability for crystallization. Apart from ethyl acetate, the observed trend in crystallization efficiency of Li and impurities across the tested solvents followed this order: acetone > isopropanol > ethanol > ethyl glycol. Acetone (O/A ratios of 3 and 6) and isopropanol (O/A ratio of 6) demonstrated promising potential to crystallize Li, enabling the formation of well-defined crystals with substantial impurity rejection.

Table 3.

Crystallization yield for organic solvent screening tests at a stirring rate of 150 rpm, 25 °C and 72 h. The yield calculated based on ICP-OES data is presented as Mean ± S.D (n = 2).

Figure 1 presents the SEM images and the corresponding EDS analysis points for crystals obtained from the screening tests using acetone and isopropanol. Crystals formed in acetone at O/A ratios of 3 and 6 are rectangular cuboid-like with visible rough patches. At an O/A ratio of 3, needle-like inclusions are observed within the crystals (Figure 1b), whereas crystals obtained at an O/A ratio of 6 show a high degree of agglomeration (Figure 1c), although they appear to retain a similar cuboid shape. In contrast, crystals recovered using isopropanol at an O/A ratio of 6 display a needle-like shape and exhibit pronounced branching structures as patches on the crystal surface.

Figure 1.

SEM images of LiOH·H2O crystals obtained during organic solvent screening tests: (a,b) crystals formed in acetone at an O/A ratio of 3 and at two different resolutions; (c,d) crystals formed in acetone at an O/A ratio of 6 and at two different resolutions; and (e,f) crystals formed in isopropanol at an O/A ratio of 6 at two different resolutions. The crystals were formed at a stirring rate of 150 rpm, for 72 h, at a temperature of 25 °C.

Table 4 presents the elemental composition (wt.%) from the EDS analysis performed at the points indicated in Figure 1. Elements such as Al, S, K, Ca, Cr, and Zn were detected as crystallized impurities during the screening tests. These impurities predominately appear on the rough or patchy surface of crystal surfaces, while smoother surfaces tend to be relatively impurity-free. The needle-like inclusion observed in the crystals at an O/A ratio of 3 for acetone contained mostly S, Zn, and K.

Table 4.

Weight % of elements analyzed by SEM-EDS on the points on Figure 1 for the LiOH·H2O crystals obtained at O/A ratios of 3 and 6 for acetone and isopropanol at a stirring rate of 150 rpm and 25 °C.

3.2. Crystallization Kinetics

As supersaturation is the primary driving force for crystal nucleation and growth, other experimental parameters related to nucleation and growth were not directly measured. Instead, nucleation and growth are discussed in Section 4 based on the supersaturation calculations derived from the data presented in this section.

Derived from the Equilibrium module of HSC Chemistry 10, Figure 2 shows the variation in activity coefficient of ions in the PLS with an increasing O/A molar ratio for both acetone and isopropanol. The change in activity coefficient is similar for the two anti-solvents. Upon addition of anti-solvent, the activity coefficient of water decreased significantly from approximately 1 to 0.5 at a molar ratio of 1.5, whereas the activity coefficient of PLS components, such as Li, Na, K, Al, Zn, Cr, Ca, OH, and S, increased.

Figure 2.

Change in activity coefficient of ions in the PLS and water with changing organic solvent/water molar ratio: (a) Acetone, (b) Isopropanol at 25 °C.

The activity coefficient and mole fraction values used for calculating the supersaturation of Li in acetone and isopropanol at OA ratios of 3 and 6 are presented in Table 5. In the case of acetone, the supersaturation increased from 1.59 to 1.61 when O/A ratios increased from 3 to 6. Meanwhile, for isopropanol this increase was sharp, i.e., from 1.34 to 2.20.

Table 5.

Molar ratio, activity coefficient and the supersaturation values for Li in acetone and isopropanol at O/A ratios of 3 and 6, at a stirring rate of 150 rpm and 25 °C.

3.3. Optimization of O/A Ratio, Crystallization Time, and Stirring Rate

Among the solvents tested, acetone demonstrated promising potential to crystallize Li, with substantial impurity rejection, at relatively lower O/A ratios. Therefore, it was selected as the anti-solvent for the recovery of high-purity LiOH·H2O from the PLS and was further investigated for process parameter optimization.

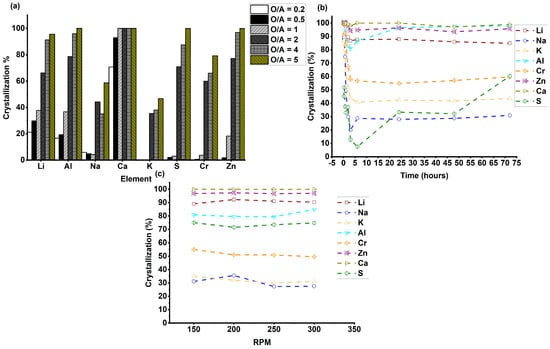

Figure 3 presents the optimization of key process parameters, O/A ratios, crystallization times and stirring rates for anti-solvent crystallization using acetone. The data is presented as a mean value with max standard deviations of ±3.3, ±6.2, and ±3.3 for the O/A ratio, crystallization time and stirring rate respectively (n = 2). As depicted in Figure 3a, increasing the O/A ratio from 0.2 to 5 led to a progressive increase in the crystallization yield of Li, reaching a maximum of 96% at an O/A ratio of 5. However, with increasing O/A ratios, the co-crystallization of impurities also increased and exceeded 90% at an O/A ratio of 5 for Al, Ca, and Zn. Therefore, an O/A ratio of 4 was selected as optimal, balancing a high Li recovery (90%) with comparatively less impurity incorporation. Crystallization time optimization (Figure 3b) conducted at the selected O/A ratio of 4 revealed that both Li and the impurities crystallized rapidly during the initial stages. Over time, the impurity levels started to reduce and stabilized for most of the impurities after 3 h. Therefore, a crystallization time of 3 h was deemed optimal.

Figure 3.

Process parameter optimization for anti-solvent crystallization of LiOH·H2O using acetone; (a) crystallization yield of Li and co-crystallization of other impurities at O/A ratios of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 5, at 25 °C, stirring rate of 150 rpm, and 72 h; (b) crystallization yield of Li and co-crystallization of other impurities during elapsed time of 72 h, at an O/A ratio of 4, 25 °C, and stirring rate of 150 rpm; (c) crystallization yield of Li and co-crystallization of impurities under stirring rates of 150, 200, 250, and 300, at an O/A ratio of 4, 25 °C, and 3 h. The crystallization yield was calculated based on ICP-OES data.

Stirring rate optimization (Figure 3c), performed at the optimized conditions of an O/A ratio of 4 and a 3 h crystallization time, showed no significant change in either Li crystallization yield or impurity co-crystallization across the range of stirring rates tested. Therefore, the initial stirring rate of 150 rpm was kept for the rest of the experiments. The results of experiments conducted under the optimized conditions—an O/A ratio of 4, crystallization time of 3 h, and stirring rate of 150 rpm at 25 °C—are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of crystallization results obtained at optimized conditions: an O/A ratio of 4, crystallization time of 3 h, and stirring rate of 150 rpm at 25 °C. The crystallization yield calculated based on ICP-OES data is presented as Mean ± S.D (n = 2).

3.4. Supersaturation Control Through Anti-Solvent Addition Rate

Table 7 presents the crystallization behavior of PLS components under various anti-solvent flow rates. Li recovery remained constantly high at around 90% across all tested flow rates. However, minimum co-crystallization of impurities was achieved at the flow rate of 5 mL/min and was considered to be favorable for Li crystallization.

Table 7.

Summary of crystallization results at various flow rates at an O/A ratio of 4, crystallization time of 3 h, stirring rate of 150 rpm and 25 °C. The crystallization yield calculated based on ICP-OES data is presented as Mean ± S.D (n = 2).

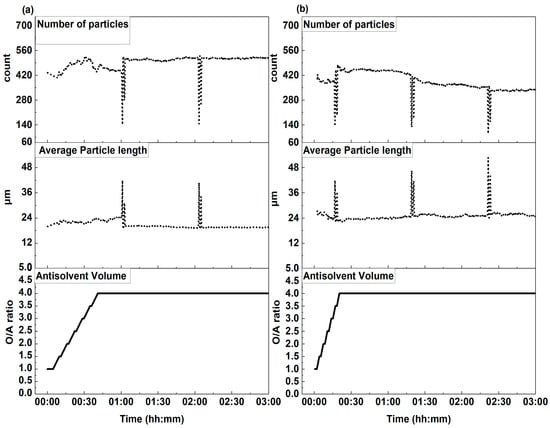

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of the controlled acetone addition rate on crystal formation, showing the evolution of average crystal length and number of particles over time for two flow rates, i.e., 5 mL/min and 12.5 mL/min. The cumulative volume of anti-solvent added is also presented to highlight the effect of progressive anti-solvent addition on the count and size of particles.

Figure 4.

Average particle length and counts of particles recorded in the focus area of a laser beam with respect to the changing O/A ratio: (a) acetone at an addition rate of 5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, 25 °C; (b) acetone at an addition rate of 12.5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, 25 °C.

At a flow rate of 5 mL/min (Figure 4a) both the average particle length and counts were high from the start and increased substantially when the O/A ratio exceeded a value above 1.5. The growth in the number of particles was more pronounced than the increase in the average length of crystals. The maximum particle count was recorded at an O/A ratio of 3.5, followed by a temporary decline accompanied by a slight increase in particle size. Both parameters stabilized during the hold time once the O/A ratio reached a value of 4. Notably, spikes in average particle size accompanied by drops in particle count were occasionally observed during the experiment; these fluctuations quickly normalized and were likely due to large, agglomerated particles temporarily entering the detector’s field of view. Once they settled, the average size rapidly returned to normal.

At a higher flow rate of 12.5 mL/min (Figure 4b), similar trends were observed. The maximum number of particles occurred at an O/A ratio of 4, but the overall number of particles remained lower than at 5 mL/min and exhibited a continuous decline thereafter, but the average particle length was consistently higher than that of 5 mL/min. The temporary spikes in average particle size, likely due to agglomerated particles, were more frequent at this flow rate.

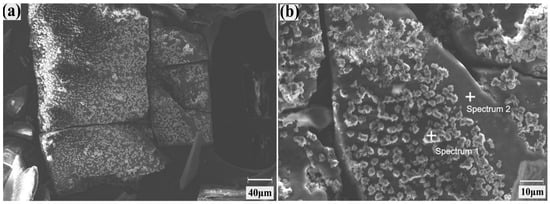

Figure 5 shows the SEM images and corresponding EDS analysis points for LiOH·H2O crystals formed in acetone at an anti-solvent flow rate of 5 mL/min. The crystals maintain the characteristic rectangular cuboid-like morphology observed during the initial screening tests. However, the rough patches now appear to be more uniformly distributed across the crystal surface. Table 8 presents the elemental composition (wt.%) obtained from the EDS analysis conducted at the points indicated in Figure 5. Elements such as Al, K, Ca, and Zn were detected as crystallized impurities under the optimized flow conditions. These impurities were predominately located on the rough surface regions of crystals, while smoother surfaces only tended to retain Zn.

Figure 5.

SEM images of LiOH·H2O crystals at two different resolutions: (a) at 40 µm and (b) at 10 µm. The crystals were formed in acetone at an O/A ratio of 4, with an acetone flow rate of 5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, for 3 h, at a temperature of 25 °C.

Table 8.

Weight % of elements analyzed by SEM-EDS on the points on Figure 5 for the LiOH·H2O crystals obtained in acetone at an O/A ratio of 4, flow rate of 5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, 3 h, at a temperature of 25 °C.

Table 9 presents the ICP-OES results of digested LiOH·H2O crystals, produced under optimized conditions, and their allowable limits for commercial battery-grade specifications [36]. Based on the Li content, the recovered LiOH·H2O crystals correspond to around 95% purity. All measured impurity concentrations exceeded acceptable thresholds for battery-grade LiOH·H2O precursors by 1–3 orders of magnitude and therefore require substantial mitigation to achieve battery-grade purity.

Table 9.

Concentration of crystallized impurities in LiOH.H2O (an O/A ratio of 4, acetone flow rate of 5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, for 3 h, at a temperature of 25 °C) in comparison to allowable impurity limit in commercial LiOH∙H2O. The concentration of crystallized Li and impurities is measured by ICP-OES.

3.5. Diagnosis of Impurity Incorporation Mechanism

The LiOH·H2O crystals formed in acetone under optimized conditions of anti-solvent addition rate of 5 mL/min, an O/A ratio of 4, stirring rate of 150 rpm, and 25 °C, were examined using SEM as shown in Figure 5. The crystals exhibit free-flowing, well-dispersed morphology, ruling out agglomeration as the primary mechanism of impurity incorporation within the crystals.

Surface washing experiments conducted on LiOH·H2O crystals formed in acetone under optimized flow rate conditions removed none of the impurities from the surface of the crystals. This finding effectively rules out surface adsorption as the primary mechanism of impurity incorporation within the LiOH·H2O crystals.

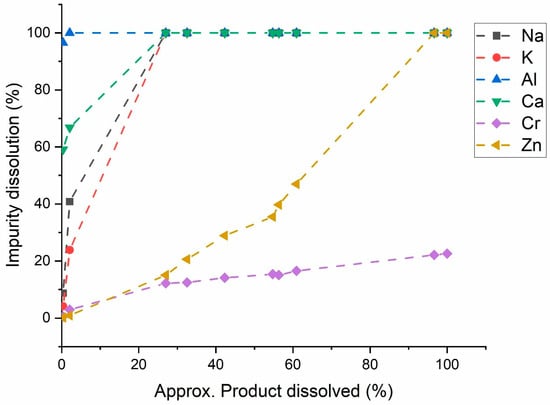

Figure 6 shows the dissolution profile of impurities as bulk LiOH·H2O crystals were gradually dissolved through incremental additions of Milli-Q water. The data is presented as a mean value with a maximum standard deviation of ±3.4 (n = 2). For Al, the dissolution was sharp and reached above 95% after the first addition. Complete Al dissolution occurred after the second addition when around 5% of bulk crystals were dissolved. Similarly, Na, K, and Ca showed rapid dissolution with 100% of each element dissolved when roughly 25% of the bulk crystals were dissolved. In contrast, Cr dissolution was steadier and reached only around 23%, even when the bulk crystals were fully dissolved. Zn dissolution was initially gradual but increased sharply when approximately 60% of bulk LiOH·H2O crystals were dissolved, ultimately reaching complete dissolution when around 95% of bulk crystals dissolved.

Figure 6.

Dissolution of impurities with respect to bulk LiOH·H2O crystals dissolution. The LiOH·H2O were formed at optimized conditions of an O/A ratio of 4, with acetone flow rate of 5 mL/min, stirring rate of 150 rpm, for 3 h, at temperature of 25 °C. The impurity dissolution % was calculated based on ICP-OES data.

Except for Zn, the gradual dissolution of impurities suggested the formation of high- or low-solubility conglomerates. To determine whether Zn dissolution was driven by conglomerate effects, a solubility test was performed. Table 10 presents the mean ± S.D (n = 2) solubility for Zn at different acetone/water ratios, alongside the corresponding Zn dissolution observed during the gradual dissolution experiments. The results depict that Zn was almost insoluble across all acetone/water ratios tested. In contrast, during the gradual dissolution experiments, Zn dissolved consistently with each successive addition of Milli-Q.

Table 10.

Solubility of Zn in different acetone/water ratio and the corresponding Zn dissolution during gradual dissolution experiments. The solubility (mg) calculated based on ICP-OES data is presented as Mean ± S.D (n = 2).

4. Discussions

The crystallization yield for Li observed during the screening tests is consistent with the dielectric constants of the organic solvents (Table 2) investigated. The trend in dielectric constant follows this order: ethyl acetate > acetone > isopropanol > ethanol > ethyl glycol. Screening tests with ethyl acetate did not yield well-defined LiOH·H2O crystals. This may be attributed to the solvent’s hydrogen bonding characteristics and its impact on the solvation environment. Ethyl acetate is a polar aprotic solvent with moderate hydrogen bond accepter capacity but no hydrogen bond donor ability. Its introduction into the PLS might have facilitated the formation of extended hydrogen bonded networks involving water and ethyl acetate molecules [37]. These networks could disrupt the hydrogen shell surrounding Li+ ions, thereby trapping it and preventing well-ordered crystal formation.

Although acetone and isopropanol have comparable dielectric constants (20.7 and 20.1, respectively, in Table 2), their performance as anti-solvents differed significantly. At an O/A ratio of 3, the crystallization yield of Li was 86% for acetone, but only 37% for isopropanol (Table 3). Since anti-solvent crystallization is a diffusion-controlled process, lower viscosity enhances molecular diffusion and promotes nucleation [11]. Acetone with a viscosity of 0.36 cP, facilitates faster diffusion than isopropanol, which has a viscosity of 2.25 cP (Table 2), likely resulting in higher Li recovery.

Rectangular cuboid-like LiOH·H2O crystals were obtained in acetone, while needle-like crystals were observed in isopropanol at an O/A ratio of 6 (Figure 1). This difference in crystal morphology can be attributed to the varying levels of supersaturation achieved in the two solvents, as shown in Table 5. In acetone the increase in supersaturation from O/A ratios of 3 and 6 was minimal (from 1.59 to 1.61), whereas in isopropanol, the supersaturation increased significantly from 1.34 to 2.20. This substantial increase likely influenced both nucleation and crystal growth rates, leading to the formation of fine needle-like crystals in isopropanol. The nucleation and growth rates are highly sensitive to supersaturation as compared to the parameter in Equations (2) and (3). For instance, an increase in supersaturation from 2 to 4 can lead to around 1070 folds increase in the nucleation rate [38]. Such a surge would favor the formation of numerous small nuclei and limit growth, resulting in thin, needle-like crystal morphologies.

During screening tests, impurities such as Na, K, Al, Zn, Cr, S, and Ca were also crystallized with Li. The SEM-EDS analysis of LiOH·H2O crystals (Figure 1 and Table 4) confirmed the presence of these impurities predominately on rough or patchy regions of crystal surfaces. This can be explained by the ionic properties and activity coefficient of these species in solution. For crystallization to occur, ions must first release their hydration shells [39]. Ions with higher ionic charge density are more resilient to dehydration, making them less likely to crystallize under the same conditions. The ionic charge density is directly proportional to the oxidation state and inversely proportional to the ionic radius [11]. Therefore, monovalent cations, such as Na+ and K+, which possess lower charge density and relatively larger ionic radius, are more readily dehydrated and more likely to crystallize. In contrast, divalent (Zn2+, Ca2+), trivalent (Al3+) and multivalent (S, Cr) ions exhibit higher charge density, making dehydration and subsequent crystallization more energy demanding. Solvation theory provides further insights into the concept of the heat of hydration. It defines the hydration effect as the energy required to separate water molecules from a hydrated ion. Crystallization becomes more favorable as the heat of hydration decreases [40].

Table 11 summarizes the ionic radius, oxidation state, and heat of hydration of Li and for the major impurity ions present in the PLS as impurities. Na+ and K+ are monovalent cations with a low heat of hydration. Under conditions of reduced water activity and elevated OH− concentration, they would have been crystallized. In contrast, divalent and multivalent impurities have smaller ionic radii and higher hydration; however, an increase in their activity coefficients under high OH− concentration might have promoted their crystallization.

Table 11.

Ionic properties of ions, present in the studied PLS. The date to make this table was taken from [9,41].

The optimization experiments for LiOH·H2O crystallization using acetone as an anti-solvent identified an optimal O/A ratio of 4, a crystallization time of 3 h, and a stirring rate of 150 rpm (Figure 3). During the optimization of crystallization time, impurity incorporation was initially high but gradually decreased, stabilizing after 3 h. This behavior may be explained by supersaturation dynamics: as anti-solvent was introduced all at once, a high supersaturation likely promoted both Li and impurity crystallization. As crystallization progressed and LiOH·H2O crystals continued to grow, the impurities were progressively excluded, possibly due to structural characteristics of the growing crystals. However, S crystallization after about 5 h began to increase and reached around 60% at 72 h. This depicts recrystallization of S, possibly due to the reestablishment of supersaturation in the mother liquor [42].

The average crystal length and number of crystals calculated for two different anti-solvent flow rates with optimized parameters using acetone (Figure 4) suggest different growth regimes. At 5 mL/min, particle counts increased significantly, and the average particle size remained relatively smaller, around 20 μm. This behavior indicates a nucleation dominant regime, where the formation of numerous small crystals is favored due to moderate supersaturation. At 12.5 mL/min, the particle count remained lower, while the average particle size increased to approximately 25 μm. This trend suggests that fewer nuclei were formed initially, but the crystals experienced more rapid growth due to higher availability of solute, leading to a growth-dominated regime [43].

Varying acetone flow rates did not yield a significant difference in impurity rejection. This may be due to higher final supersaturation achieved in each setup due to an elevated O/A ratio. The increased supersaturation would likely have reduced the solubility of multiple ionic species, promoting their simultaneous crystallization. Slightly higher levels of crystallized impurities such as K, Al, Ca, and Cr were detected at 12.5 mL/min compared to 5 mL/min (Table 7). These differences may be attributed to varying degrees of agglomeration. At higher flow rates, such as 12.5 mL/min, a continuous decline in the number of particles was recorded (Figure 4), indicating significant agglomeration during crystallization. However, at 5 mL/min only a single dip in particle count was observed, after which it stabilized and continued to grow. This behavior suggests that agglomeration significantly reduced at lower flow rates, leading to improved impurity rejection.

The LiOH·H2O crystals obtained through controlled acetone addition at the flow rate of 5 mL/min (Table 7) exhibited lower impurity levels as compared to the crystals formed by introducing acetone all at once (Table 6), despite similar Li crystallization % in both cases. SEM-EDS analysis of the crystals (Figure 5 and Table 8) showed that the crystallized impurities are uniformly distributed on the rough patches of crystal surface. This suggests that controlled anti-solvent addition not only enhances impurity rejection but also influences the distribution of residual impurities during crystallization.

The experiments conducted to investigate impurity incorporation mechanisms in LiOH·H2O crystals formed under optimized conditions of an O/A ratio of 4, crystallization time of 3 h, stirring rate of 150 rpm and acetone flow rate of 5 mL/min (Figure 5) suggest that agglomeration and surface adsorption are not the primary mechanism of impurity incorporation. Instead, most of the impurities crystallized as high- or low-solubility conglomerates. Gradual dissolution experiments (Figure 6) revealed that impurities, i.e., Na, K, Ca, and Al, dissolved predominately during the early stages of bulk LiOH·H2O crystal dissolution (~25%). This behavior indicates that these impurities were primarily crystallized as high-solubility conglomerates. Cr exhibited a dissolution pattern consistent with a low-solubility conglomerate, with only 23% dissolution occurring when 100% of bulk crystals were dissolved [25]. This distinct behavior of Cr, which may be present as Cr(OH)3 with bulk crystals, is due to its insolubility in water and acetone [44]. The limited dissolution likely occurred due to an increase in pH with LiOH·H2O crystal dissolution, which may have dissolved the amphoteric chromium hydroxide.

The dissolution of Zn suggests a more uniform distribution throughout the crystal bulk. The uniform distribution in the crystal bulk is supported by SEM-EDS data (Table 4 and Table 8). The solubility of Zn in different acetone/water solutions alongside its corresponding gradual dissolution (Table 10) suggests that Zn might have crystallized in a form other than Zn (OH)2. The distribution of Zn in the crystal bulk could be due to two possible mechanisms. Firstly, because Zn is amphoteric, it may have been readily present as zincate in the strongly basic PLS [45] and might have been trapped into the rapidly growing LiOH·H2O crystals. This zinc may have been released into the solution during gradual dissolution experiments. Secondly, Zn incorporation may have occurred due to the formation of a mixed Li–Zn phase. Previous studies report that Li can interact with Zn-bearing phases, making the formation of mixed Li–Zn phases plausible during crystallization [46].

Impurity Mitigation Strategies

Although substantial impurity rejection was achieved with acetone under optimized conditions, the resulting purity of LiOH·H2O crystals remained around 95%, which falls short of the ≥99% purity required for battery-grade LiOH·H2O [6].

To address this, several strategies can be considered. The impurities crystallized with LiOH·H2O crystals Al, Na, K, Cr, Zn, and Ca can potentially be minimized by controlling the pH during the leaching stage used to obtain the PLS, by controlling supersaturation through seeding [47] and/or using appropriate wash solvents [48]. Oxides of Al, Cr, and Zn which are present in the flue dust [30] are amphoteric [44] and readily form soluble complexes under strong alkaline conditions. Therefore, controlling pH may limit the dissolution of these elements, and their eventual crystallization with LiOH·H2O crystals. Seeding with LiOH·H2O crystals can promote crystallization to occur at lower supersaturation, enabling better control over crystal growth rates and therefore the impurities may not be trapped physically within the growing crystals. In addition, the rapid drop in supersaturation following seed addition may prevent impurities from reaching their nucleation thresholds. Similarly, using wash solvents that exhibit higher solubility specifically for impurities can facilitate the removal of most of the high-solubility conglomerate impurities such as Na, K, Ca, and Al from the bulk crystals.

To tackle impurity incorporation without detailed knowledge of specific impurity incorporation mechanisms, a novel strategy involving impurity complexation can be employed [48]. The resulting impurity–ligand complexes are larger and more hydrophilic than their free-ion counterparts, allowing their separation from both the solvent and solute of interest by methods such as membrane filtration [49]. This method is broadly applicable across various impurity incorporation pathways, with the exception of impurities that enter the crystals by solution entrapment. In this case the complexes also remain in the trapped solution [50].

5. Conclusions

This study investigated anti-solvent crystallization as a method for recovering high-purity lithium hydroxide monohydrate (LiOH·H2O) from lithium (Li)-rich leachate with a focus on process optimization, crystallization behavior, and impurity incorporation mechanisms. Although several solvents, including ethanol, which have been reported in previous studies for Li crystallization, produced substantial yields of LiOH·H2O, acetone was identified to be the most effective crystallization solvent. At a comparatively lower organic-to-aqueous (O/A) volumetric ratio than those required by other solvents used in this study, acetone achieved higher crystallization yields while exhibiting superior impurity rejection. Under optimized conditions (an O/A ratio of 4, acetone flow rate of 5 mL/min, crystallization time of 3 h, stirring rate of 150 rpm, and 25 °C) around 90% Li recovery with a crystal purity of 95% was achieved.

The mechanisms of impurity incorporation within bulk LiOH·H2O crystals were governed by supersaturation and crystallization kinetics. Diagnosis experiments revealed that most of the impurities in the crystals obtained under optimized conditions were incorporated as conglomerates. Na, K, Al, and Ca were crystallized as high-solubility conglomerates and Cr was crystallized as a low-solubility conglomerate. Zn showed uniform distribution throughout the bulk LiOH·H2O crystals. This distribution indicated either entrapment of soluble zincate within rapidly growing LiOH·H2O crystals or the formation of a mixed phase.

Based on the achieved results, effective impurity rejection to battery-grade levels requires exploration of several strategies, which include pH control during PLS production; further suppression of supersaturation by seeding; using appropriate wash solvents to selectively dissolve impurities; or impurity complexation with membrane-based separation. Therefore, systematic investigation of these approaches is critical to producing battery-grade LiOH·H2O

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.M., I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö.; Data curation: F.M.; Formal analysis: F.M.; Funding acquisition: L.S.-Ö.; Investigation: F.M., I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö.; Methodology: F.M., I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö.; Project administration: L.S.-Ö.; Resources: L.S.-Ö.; Software: F.M.; Supervision: I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö.; Validation: I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö.; Visualization: F.M.; Writing—original draft: FM.; Writing—review and editing: F.M., I.S., F.E. and L.S.-Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Swedish Energy Agency and ÅForsk, through projects “Process development for the recovery of lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries” (ÅForsk, Grant No. 20-508, 2020–2023) and “Optimizing Processes for recycling of lithium-ion batteries” (OptiLIB, Grant No. 2021-002312, 2021–2024).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Centre of Advanced Mining and Metallurgy (CAMM) and by CAMM-CRM, a Swedish government-supported initiative on critical raw materials at Luleå University of Technology, for supporting this research. The authors would also like to thank project partners Swerim and Northvolt, for their collaboration and contributions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5.2) to improve the language and readability of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boroumand, Y.; Razmjou, A. Adsorption-type aluminium-based direct lithium extraction: The effect of heat, salinity and lithium content. Desalination 2024, 577, 117406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global EV Outlook 2023: Catching Up with Climate Ambitions. 2023. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/dacf14d2-eabc-498a-8263-9f97fd5dc327/GEVO2023.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y. Influence of Li source on tap density and high rate cycling performance of spherical Li[Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3]O2 for advanced lithium-ion batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, B.; Yakovleva, M. Study of the Effect of Lithium Precursor Choice on Performance of Nickel-Rich NMC. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2017, MA2017-02, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.C.; Wang, M.; Dai, Q.; Winjobi, O. Energy, greenhouse gas, and water life cycle analysis of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide monohydrate from brine and ore resources and their use in lithium ion battery cathodes and lithium ion batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Peng, C.; Ma, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Z.; Wilson, B.P.; Lundström, M. Selective lithium recovery and integrated preparation of high-purity lithium hydroxide products from spent lithium-ion batteries. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Seo, S.; Han, K.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.J. A process using a thermal reduction for producing the battery grade lithium hydroxide from wasted black powder generated by cathode active materials manufacturing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-L.; Wang, H.-Y.; Ward, J.D. Economic Comparison of Crystallization Technologies for Different Chemical Products. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 12444–12457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, G.A.; Demopoulos, G.P. Organic solvent-assisted crystallization of inorganic salts from acidic media. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingaertner, D.A.; Lynn, S.; Hanson, D.N. Extractive crystallization of salts from concentrated aqueous solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1991, 30, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibania, S.; Sundqvist-Öqvist, L.; Rosenkranz, J.; Ghorbani, Y. Application of Anti-Solvent Crystallization for High-Purity Potash Production from K-Feldspar Leaching Solution. Processes 2024, 12, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.A.; Dye, S.R.; Ng, K.M. Synthesis of drowning-out crystallization-based separations. AIChE J. 1997, 43, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, N.; Bao, Y.; Hao, H. Crystallization techniques in wastewater treatment: An overview of applications. Chemosphere 2017, 173, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-H.; Kiyonga, A.N.; Lee, E.H.; Jung, K. Simple and Efficient Spherical Crystallization of Clopidogrel Bisulfate Form-I via Anti-Solvent Crystallization Method. Crystals 2019, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Desai, M.A.; Patel, S.R. Effect of surfactants and polymers on morphology and particle size of telmisartan in ultrasound-assisted anti-solvent crystallization. Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Ş.; Peters, E.M.; Forsberg, K.; Dittrich, C.; Stopic, S.; Friedrich, B. Scandium Recovery from an Ammonium Fluoride Strip Liquor by Anti-Solvent Crystallization. Metals 2018, 8, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.; Kaya, Ş.; Dittrich, C.; Forsberg, K. Recovery of Scandium by Crystallization Techniques. J. Sustain. Metall. 2019, 5, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.; Svärd, M.; Forsberg, K. Impact of process parameters on product size and morphology in hydrometallurgical antisolvent crystallization. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 2851–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Chagnes, A.; Xiao, X.; Olsson, R.T.; Forsberg, K. Antisolvent Precipitation for Metal Recovery from Citric Acid Solution in Recycling of NMC Cathode Materials. Metals 2022, 12, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, H.S.; Svärd, M.; Uysal, D.; Doğan, Ö.M.; Uysal, B.Z.; Forsberg, K. Antisolvent crystallization of battery grade nickel sulphate hydrate in the processing of lateritic ores. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 286, 120473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Svärd, M.; Forsberg, K. Recycling cathode material LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2 by leaching with a deep eutectic solvent and metal recovery with antisolvent crystallization. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, T.A.; Morales, J.W.; Robles, P.A.; Galleguillos, H.R.; Taboada, M.E. Behavior of LiOH·H2O crystals obtained by evaporation and by drowning out. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2008, 43, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, J.; Chong, M.W.S.; Manson, A.; Brown, C.J.; Nordon, A.; Sefcik, J. Effect of Process Conditions on Particle Size and Shape in Continuous Antisolvent Crystallisation of Lovastatin. Crystals 2020, 10, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, G.A.; Demopoulos, G.P. Producing high-grade nickel sulfate with solvent displacement crystallization. JOM 2002, 54, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.; Rawal, S.H.; Reddy, V.R.; Viswanath, S.K.; Merritt, J.M. Case Studies in the Application of a Workflow-Based Crystallization Design for Optimized Impurity Rejection in Pharmaceutical Development. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2023, 27, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urwin, S.J.; Levilain, G.; Marziano, I.; Merritt, J.M.; Houson, I.; Ter Horst, J.H. A Structured Approach to Cope with Impurities during Industrial Crystallization Development. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 1443–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H.E.; Salisbury, A.; Huijsmans, J.; Dzade, N.Y.; Plümper, O. Influence of Inorganic Solution Components on Lithium Carbonate Crystal Growth. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 6994–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiang, S.; Cui, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z. Molecular Dynamic Regulation of Na and Mg Ions on Lithium Carbonate Crystallisation in Salt Lakes. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2021, 36, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Mousa, E.; Ye, G. Recovery of Co, Ni, Mn, and Li from Li-ion batteries by smelting reduction—Part II: A pilot-scale demonstration. J. Power Sources 2021, 483, 229089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, F.; Strandkvist, I.; Engström, F.; Andersson, A.; Sundqvist-Öqvist, L. Hydrometallurgical Recycling of Lithium from the Flue Dust Generated During Pyrometallurgical Processing of LIB Material: A Comparative Analysis of Carbonated and Limewater Leaching. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 1952–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. Handbook of Solvents; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2001; ISBN 1-895198-24-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, K.; Myerson, A.; Trout, B. Polymorphic control by heterogeneous nucleation—A new method for selecting crystalline substrates. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Vipin Kumar, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar Gaurav, G.; Naresh Gupta, K. A critical review on thermodynamic and hydrodynamic modeling and simulation of liquid antisolvent crystallization of pharmaceutical compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, W.; Lorenz, H. Partial Miscibility of Organic Compounds in the Solid State—The Case of Two Epimers of a Diastereoisomer. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2006, 29, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, E.; Othman, R.; Vladisavljević, G.; Nagy, Z. Preventing Crystal Agglomeration of Pharmaceutical Crystals Using Temperature Cycling and a Novel Membrane Crystallization Procedure for Seed Crystal Generation. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, O.A.; Petranikova, M. Review of Achieved Purities after Li-ion Batteries Hydrometallurgical Treatment and Impurities Effects on the Cathode Performance. Batteries 2021, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakipov, I.T.; Petrov, A.A.; Akhmadiyarov, A.A.; Khachatrian, A.A.; Mukhametzyanov, T.A.; Solomonov, B.N. Thermochemistry of Solution, Solvation, and Hydrogen Bonding of Cyclic Amides in Proton Acceptor and Donor Solvents. Amide Cycle Size Effect. Molecules 2021, 26, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.G.; Hyeon, T. Formation Mechanisms of Uniform Nanocrystals via Hot-Injection and Heat-Up Methods. Small 2011, 7, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Yang, P.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Fang, C.; Gong, J. Recent progress in antisolvent crystallization. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 3122–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraati, M.; Chauhan, N.P.S.; Sargazi, G. Removal of electrolyte impurities from industrial electrolyte of electro-refining copper using green crystallization approach. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 3873–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atomistic Simulation Group. Database of Ionic Radii; Atomistic Simulation Group: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, F.L.; Sirota, E.; Hartmanshenn, C.; Kwok, T.T.; Paolello, M.; Li, H.; Abeyta, V.; Bramante, T.; Madrigal, E.; Behre, T.; et al. Prevalence of Impurity Retention Mechanisms in Pharmaceutical Crystallizations. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2023, 27, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, J.W. Crystallization, 4th ed.; Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, M.J. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 15th ed.; Merck & Co., Inc.: Rahway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Uekawa, N.; Yamashita, R.; Wu, Y.J.; Kakegawa, K. Effect of alkali metal hydroxide on formation processes of zinc oxide crystallites from aqueous solutions containing Zn(OH)42− ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.R.; Norby, P.; Nørlund Christensen, A.; Hanson, J.C. Hydrothermal synthesis, crystal structure refinement and thermal transformation of LiZnAsO4·H2O. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 1998, 26, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.L.; Tung, H.-H.; Midler, M. Organic crystallization processes. Powder Technol. 2005, 150, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capellades, G.; Bonsu, J.O.; Myerson, A.S. Impurity incorporation in solution crystallization: Diagnosis, prevention, and control. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Ortner, F.; Quon, J.; Peeva, L.; Livingston, A.; Trout, B.L.; Myerson, A.S. Use of Continuous MSMPR Crystallization with Integrated Nanofiltration Membrane Recycle for Enhanced Yield and Purity in API Crystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.C.; Wood, G.P.F.; Kunov-Kruse, A.J.; Nmagu, D.E.; Trout, B.L.; Myerson, A.S. Quantitative Solution Measurement for the Selection of Complexing Agents to Enable Purification by Impurity Complexation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.