Abstract

This paper proposes a unified state-of-health (SoH) predictive energy management and adaptive grid-forming (GFM) control framework for battery energy storage systems, addressing the conflict between battery lifetime degradation and dynamic stability under grid-support operation. A composite degradation model is incorporated into a multi-timescale EMS to anticipate aging trends, while real-time virtual inertia, damping, and impedance are adjusted according to instantaneous SoH. Simulation results demonstrate that, compared with conventional non-SoH-aware control, the proposed method reduces transient overshoot by up to 32%, shortens settling time by 25–40%, and lowers peak battery current stress by 12–23% under aged (60% SoH) conditions. Moreover, the unified framework maintains consistent damping performance across different aging stages, whereas traditional approaches exhibit significant degradation. These quantitative improvements confirm that jointly embedding SoH prediction into both dispatch scheduling and GFM control can effectively enhance transient performance while extending battery lifetime.

1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of photovoltaic (PV) generation and battery energy storage systems (BESSs) in modern power grids has significantly increased the demand for enhanced grid-support functionalities and autonomous operation capability [1,2]. Among various control paradigms, grid-forming (GFM) control has emerged as a promising solution to provide synthetic inertia, stable voltage regulation, and seamless grid-support services in weak and low-inertia networks [3,4,5,6]. However, when BESSs operate as GFM units, the battery—being the primary source of DC-side energy—continuously experiences dynamic power fluctuations and transient stress [7,8]. These high-frequency current ripples, large power swings, and frequent charge/discharge transitions inevitably accelerate battery degradation, posing new challenges for both the stability of GFM operation and the long-term reliability of energy storage systems [9,10].

Existing GFM control strategies mainly focus on enhancing transient stability, improving weak-grid adaptability, or regulating power sharing among multiple units [11,12]. Typical approaches rely on tuning virtual inertia/damping, droop coefficients, or virtual impedance loops to achieve desired voltage and frequency behavior [3,4,13]. Although these methods can significantly improve dynamic performance, they generally neglect the degradation characteristics of the battery [14,15]. As a result, GFM converters may request transient power surges that exceed the battery’s aging-friendly operating region, thereby accelerating capacity fade and increasing internal resistance [8,9]. This issue becomes more pronounced in long-term deployment scenarios, where the State-of-Health (SoH) evolves with cycling, temperature, and operational stress [16,17]. A mismatch between control-level demands and the battery’s available capability can lead to inefficient operation, sub-optimal lifetime utilization, and potential safety risks [18].

On the other hand, recent studies on energy management systems (EMSs) and battery degradation modeling have introduced a variety of SoH prediction methods, including empirical models, equivalent-circuit-model-based estimators, and machine learning-based predictors [7,13,15,19]. These techniques provide valuable insights into future degradation evolution. Nevertheless, most current EMS frameworks apply SoH information only to schedule long-term charging/discharging strategies, while GFM control remains decoupled from the degradation-aware decision-making process [14,17,20]. Consequently, conventional EMS–GFM architectures lack a mechanism to coordinate long-term aging trends with short-term transient control, limiting their effectiveness in extending battery lifetime under grid-support conditions.

Although this work focuses primarily on lithium-ion batteries, the proposed concept of integrating state-of-health prediction with real-time energy management and converter control exhibits strong universality across electrochemical energy systems [21,22]. Similar degradation-coupled behaviors are observed in proton-exchange-membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), where aging manifests through membrane hydration loss, catalyst degradation, and increased ohmic and concentration polarization [23,24]. Recent studies have demonstrated that polarization-loss decomposition and dynamic electrochemical impedance analysis enable online estimation of PEMFC health state and performance deterioration. These indicators play roles analogous to capacity fade and internal resistance evolution in batteries [25,26].

In recent years, significant advances have been made in battery state-of-health (SoH) estimation methods, which form an essential foundation for degradation-aware energy management. Beyond classical empirical and equivalent-circuit approaches, hybrid modeling and learning-enhanced estimation have shown considerable potential. For example, the work reported in Journal of Energy Chemistry [27] proposes a physics-guided data-driven SoH estimator that combines electrochemical degradation signatures with neural-network inference, improving robustness against temperature variation and irregular cycling profiles. Another recent study [28] develops a multi-feature fusion framework that leverages impedance evolution, differential capacity indicators, and adaptive filtering techniques to achieve more reliable long-term degradation tracking. These contributions demonstrate a clear trend toward richer, multi-source SoH characterization, which provides more informative degradation indicators for use in energy management and control.

In parallel with advances in SoH estimation, research on the integration of SoH awareness into energy management has also progressed rapidly. Existing studies show that incorporating SoH constraints into charging optimization, power-scheduling decisions, and lifetime-conscious dispatch can significantly reduce aging accumulation. However, most of these efforts treat SoH as a slow-timescale variable and apply it only at the EMS level. The deep coupling between SoH dynamics and fast grid-forming control—particularly under transient stress conditions—remains largely unexplored. As a result, even systems equipped with accurate SoH estimators may still experience overshoot, stability degradation, and accelerated aging when operating under grid-support modes. These limitations highlight the need for a unified framework that embeds SoH prediction not only into slow-timescale EMS optimization but also into real-time GFM parameter adaptation, enabling coordinated lifetime management and dynamic stability enhancement.

This similarity suggests that many of the mechanisms underlying SoH-aware power control—such as constraints on safe operating regions, degradation-weighted dispatch decisions, and real-time adaptation of converter parameters—can be generalized to fuel cells as well. In both systems, the internal electrochemical processes directly influence the permissible current slew rate, dynamic response capability, and allowable transient power envelope [29,30]. Consequently, the unified EMS–GFM framework proposed in this work may be extended, with appropriate tailoring, to future hybrid energy systems where batteries and fuel cells operate cooperatively in microgrids, transportation platforms, and hydrogen–electric energy hubs.

Furthermore, the long-term trend toward hydrogen–electric hybrid storage architectures motivates the development of cross-technology health-management strategies. A multi-source SoH-aware controller capable of coordinating battery degradation, fuel-cell aging trajectories, and power-electronic stress could substantially enhance overall system longevity and reliability. By explicitly acknowledging these parallels, this work aims to establish a foundation for generalized degradation-aware control methods applicable to a broader range of electrochemical energy devices.

In contrast to conventional architectures in which the energy management system (EMS) and grid-forming (GFM) control are designed independently, the proposed framework provides a unified degradation-aware coordination mechanism. Most existing EMS studies utilize SoH estimation primarily for long-term charge/discharge scheduling, while real-time GFM control relies on fixed or heuristically tuned virtual inertia, damping, and impedance parameters. This decoupled structure leads to inherent inconsistency: the EMS may assign power setpoints that do not reflect the instantaneous aging condition of the battery, while the GFM controller may request transient power responses that exceed the degraded cell’s safe operating capability. As a result, neither long-term lifetime objectives nor short-term dynamic performance can be guaranteed simultaneously.

The unified framework proposed in this work explicitly embeds SoH evolution into both multi-timescale EMS optimization and real-time GFM adaptation. By coupling long-term degradation trajectories with short-term dynamic constraints, the method ensures that dispatch decisions, virtual parameter scheduling, and transient power envelopes co-evolve consistently with battery aging. This joint consideration across timescales fundamentally differs from the representative decoupled strategies in the literature and enables coordinated enhancement of service stability, grid-support capability, and lifetime utilization.

These observations highlight a critical research gap: how to integrate SoH prediction into both energy management and GFM dynamic control so that the BESS can provide reliable grid-support services while minimizing degradation-related stress. The challenge lies in establishing a unified framework that couples multi-timescale battery behavior—i.e., long-term aging evolution and fast transient dynamics—with the control objectives of GFM inverters, enabling both stable grid-forming operation and sustainable battery usage. To bridge this gap, this paper proposes a State-of-Health predictive energy management and adaptive grid-forming control strategy for battery energy storage systems. The major contributions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Pioneering coupling mechanism: A unified degradation-aware framework is established by closing the loop from battery state-of-health (SoH) prediction to multi-timescale energy management system (EMS) scheduling and real-time grid-forming (GFM) parameter adaptation. This closed-loop mechanism enables battery aging information to consistently drive both long-term dispatch decisions and fast converter control actions.

- (2)

- Multi-timescale optimization with aging trajectories: For the first time, battery aging trajectories are explicitly incorporated as decision variables in a multi-timescale EMS framework. By embedding SoH evolution into scheduling, dispatch, and constraint layers, the proposed method coordinates operational performance with lifetime-aware energy management.

- (3)

- Performance breakthrough under aging conditions: The proposed framework resolves the long-standing contradiction between battery aging and dynamic stability in grid-forming operation. Simulation results demonstrate that, compared with conventional non-SoH-aware control, the method reduces transient overshoot by up to 32%, shortens settling time by 25–40%, and lowers peak battery current stress by 12–23% under aged battery conditions, while maintaining consistent damping performance across different SoH levels.

The proposed approach establishes a new pathway to jointly manage battery aging and grid-forming dynamics, enabling BESS units to provide reliable grid-support services throughout their entire life cycle. Simulation results validate that the strategy effectively suppresses transient power stress, adapts to evolving battery conditions, and significantly improves both aging performance and GFM operational stability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the overall system architecture, together with the fundamental PV–BES control functions and grid-forming mechanisms. Section 3 then elaborates on the proposed SoH-predictive energy management framework and the SoH-aware adaptive GFM controller, encompassing the estimation methodology, predictive model, and parameter-adaptation strategy. In Section 4, a series of case studies and comparative simulations are carried out to demonstrate the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed approach under various operating and aging scenarios. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the principal contributions and highlighting possible avenues for future research.

2. System Description and Model

The proposed SoH-predictive energy management and grid-forming (GFM) control strategy requires a unified model capable of representing both the long-term degradation behavior of the battery system and the fast electromechanical dynamics of the converter. This section presents a hierarchical modeling framework that captures key interactions across three time scales: (1) fast dynamics (sub-millisecond to milliseconds): converter, LCL filter, and GFM loops; (2) medium dynamics (seconds to minutes): DC-link voltage/energy and battery current response; (3) slow dynamics (hours to months): battery degradation and SoH evolution. The integration of these subsystems enables analysis of how physical degradation affects real-time control performance.

2.1. BES System Description

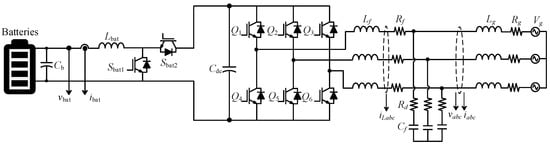

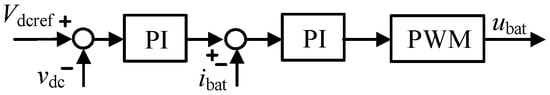

Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of the BES GFM system. It consists of the BES unit and the GFM inverter. The BES subsystem provides active power balancing and dynamic support to the DC-link. It consists of a battery stack providing the voltage vbat and current ibat, via a bidirectional DC–DC converter. The bidirectional converter allows the battery to either charge or discharge, depending on the control command and system operating conditions, enabling energy exchange with the DC-link to stabilize voltage vdc. As shown in Figure 2, the BES dual-loop controller consists of an outer DC-link voltage regulation loop and an inner battery-current tracking loop. The voltage loop monitors the deviation between the DC-link voltage vdc and its reference Vdcref, and a PI regulator generates the desired charging/discharging current. This current reference is subsequently fed into the inner loop, where a second PI controller ensures accurate control of the battery current ibat. The output of the inner PI regulator drives the PWM modulator to produce the switching commands for the power converter. By separating voltage regulation and current dynamics, the cascaded structure achieves robust disturbance rejection, improved transient performance, and enhanced protection against over-current and over-voltage events.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the PV-BES system.

Figure 2.

BES dual-loop control (PI: proportional-integral controller; PWM: pulse-width modulation).

The inverter bridges the DC-link and the AC grid and operates under a grid-forming (GFM) control framework. It converts the DC-link voltage into three-phase AC currents iLabc, which are delivered to the grid through an LC filter composed of the inductor Lf and the capacitor Cf. The point of common coupling (PCC) voltage vabc and the inverter output current iabc are measured and transformed into the synchronous dq-reference frame, yielding the voltage and current components vdq and idq for subsequent dq-axis control. The grid voltage is denoted by vg, while Lg and Rg represent the grid-side impedance. The DC-link capacitor Cdc acts as an energy buffer that decouples the PV/BES front-end dynamics from the inverter-side control.

2.2. Battery Model with Aging-Related Dynamics

The battery directly determines the available energy and instantaneous power capability of the BESS acting as a grid-forming source. When the battery ages, internal parameters such as internal resistance, charge transfer kinetics, and diffusion characteristics change significantly. To capture these effects, a SoH-dependent ECM is used.

- (1)

- Electrochemical and Terminal Voltage Dynamics

The widely-used Rint–RC hybrid ECM is adopted because it strikes a balance between accuracy and real-time computational requirements. The terminal voltage is:

where Eoc(z) captures nonlinear OCV-SOC characteristics related to electrolyte concentration, Rbat(SoH) increases with SEI layer growth, loss of lithium inventory, and current collector corrosion, and vrc models the diffusion polarization (slow electrochemical reaction component).

In this work, the internal resistance is explicitly parameterized as a monotonic function of the battery state of health (SoH), given by Rbat(SoH) = R0 [1 + kr (1 − SoH)], where R0 denotes the internal resistance of the fresh battery and kr is an experimentally calibrated degradation coefficient. This formulation provides a control-oriented representation of resistance growth that directly links battery aging to instantaneous voltage drop, power capability reduction, and DC-link stiffness.

The physical interpretation of this resistance model is consistent with widely reported lithium-ion battery aging mechanisms. At early aging stages (typically SoH > 80%), the increase in internal resistance is primarily governed by solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer formation and stabilization, resulting in a relatively mild and approximately linear resistance growth. As aging progresses into mid-to-late life stages (SoH < 80%), loss of lithium inventory (LLI), electrode structural degradation, and current collector corrosion become more pronounced, leading to accelerated resistance increase and reduced power capability.

Although experimentally observed resistance evolution may exhibit nonlinear or piecewise characteristics, numerous experimental and control-oriented studies have demonstrated that first-order linear or quasi-linear resistance–SoH models are sufficient for system-level energy management and real-time control applications. Such models offer a favorable trade-off between physical interpretability, numerical robustness, and computational efficiency, which is essential for multi-timescale EMS–GFM coordination.

It should be emphasized that the objective of the adopted resistance model is not high-fidelity electrochemical lifetime prediction, but rather to provide a physically interpretable degradation indicator that captures the dominant impact of aging on voltage dynamics and power delivery capability. This modeling philosophy is consistent with degradation-aware EMS frameworks reported in the literature and is well suited to the control-oriented focus of this study.

Equation (1) represents the widely adopted equivalent circuit model (ECM) formulation of the battery terminal voltage and serves as the foundation for the SoH estimation and prediction used in this work. The expression is derived from the Thevenin-based ECM, which characterizes the battery using its open-circuit voltage Eoc(z), an ohmic resistance Rbat(SoH), and a transient polarization branch. The open-circuit voltage Eoc(z) is a function of the state-of-charge (SOC) and reflects the thermodynamic equilibrium voltage of the lithium-ion cell. The term Rbat(SoH), i(bat) captures the instantaneous voltage drop associated with internal ohmic and charge-transfer resistance, which increases monotonically with aging and therefore provides direct information about the battery’s state of health. The third component, vrc, corresponds to the voltage across the RC polarization network and models electrochemical diffusion, double-layer dynamics, and rate-dependent voltage relaxation phenomena.

This voltage formulation closely follows the structure of standard ECMs used in the battery management literature and has been validated extensively across lithium-ion chemistries [31,32,33,34]. It provides a convenient balance between physical interpretability and computational efficiency, allowing real-time parameter identification from voltage–current measurements. In particular, the SOH-dependent internal resistance Rbat(SoH) enables the model to directly encode degradation effects within the voltage response, forming the basis for the online resistance-based SOH indicator developed in Section 3.1. This dependency is supported by numerous experimental studies demonstrating the strong correlation between resistance growth and aging mechanisms such as solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) thickening and loss of active material.

Given its ability to capture both instantaneous voltage dynamics and long-term resistance evolution, Equation (1) plays a central role in the proposed predictive EMS–GFM framework. It directly links battery degradation to available power capability, DC-link voltage stiffness, and the transient performance of the grid-forming inverter. The same formulation has been employed in representative studies of battery degradation modeling and control-oriented state estimation, confirming its suitability for integration into multi-timescale EMS architectures and real-time grid-support applications.

The battery aging and state-of-health (SoH) model adopted in this work is a control-oriented degradation model designed to support multi-time-scale energy management and grid-forming control, rather than a high-fidelity electrochemical lifetime prediction model. The primary objective of this model is to capture the dominant aging mechanisms that directly affect energy and power capability, while maintaining low computational complexity suitable for real-time EMS execution.

Several modeling assumptions are adopted to achieve this balance between physical relevance and tractability.

First, battery aging is assumed to be sufficiently characterized by capacity fade and internal resistance growth, which are widely recognized as the two most influential degradation indicators for power electronic interfaced energy storage systems. These two quantities directly determine the available charge throughput, peak power capability, voltage regulation margin, and thermal stress, all of which are critical for EMS decision-making and grid-forming control. Aging dynamics are assumed to evolve on a much slower time scale (hours to months) than electrical and control dynamics (milliseconds to seconds). This clear separation of time scales allows the degradation model to be evaluated at the EMS scheduling or dispatch interval without affecting the stability or responsiveness of the fast control loops. Thermal effects are considered in an aggregated manner, meaning that temperature-dependent aging acceleration is modeled through stress functions rather than through spatially distributed electro-thermal coupling. This assumption is consistent with control-oriented battery models commonly used in EMS and BMS applications, where average cell temperature is available but detailed thermal fields are not.

Finally, the battery system is modeled at an aggregated system level, assuming homogeneous behavior among cells or parallel strings. Cell-to-cell variations, imbalance dynamics, and active balancing actions are not explicitly modeled, as these phenomena are typically handled by lower-level battery management systems and are beyond the scope of the present EMS–GFM co-design framework.

Based on the above assumptions, the battery state-of-health is represented by a normalized scalar variable SoH in ([0, 1]), where SoH = 1 corresponds to the fresh state and SoH = 0 denotes the end-of-life condition. The discrete-time SoH evolution is modeled as

where denotes the degradation accumulated over one EMS update interval.

To reflect the different physical origins of battery degradation, the degradation increment is decomposed into cycle-aging and calendar-aging components:

where wcyc and wcal are weighting coefficients satisfying .

The cycle-aging function captures degradation induced by repetitive charge–discharge cycling and depends on the current magnitude or C-rate, depth of discharge, and operating temperature. This term reflects well-known mechanisms such as solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer growth, lithium plating under high-rate operation, and mechanically induced electrode degradation.

The calendar-aging function represents degradation occurring during storage or low-current operation and is primarily driven by average voltage stress and temperature. This term accounts for long-term side reactions and gradual loss of active lithium, which persist even in the absence of cycling. This additive degradation structure is widely adopted in semi-empirical lithium-ion aging models and provides sufficient flexibility to represent a broad range of operating conditions encountered in grid-connected BES applications. The parameters of the aging and SoH model are identified through offline calibration, using either laboratory aging experiments or manufacturer-provided lifetime characterization data. The calibration process follows standard identification procedures commonly reported in the battery aging literature.

Specifically, degradation coefficients, stress exponents, and weighting factors are obtained by fitting the model to measured capacity retention and internal resistance growth trajectories under different operating conditions, including multiple C-rates, depths of discharge, temperature levels, and average voltage conditions.

A regression-based identification approach, such as least-squares fitting or nonlinear parameter optimization, is employed to minimize the discrepancy between the modeled degradation trajectory and experimental observations. The identification is performed offline, and the resulting parameter set is treated as fixed during online EMS operation. This approach avoids the need for online parameter adaptation, ensures numerical robustness, and maintains low computational burden, which is essential for real-time implementation.

It should be emphasized that the objective of the identification process is not to achieve cell-level lifetime prediction accuracy, but to obtain a consistent and physically interpretable degradation trend that can guide degradation-aware dispatch and control decisions within the EMS–GFM framework.

The adopted modeling structure, assumptions, and identification methodology are consistent with control-oriented battery aging models that have been extensively validated experimentally in the literature. Similar SoH evolution formulations, based on capacity fade and resistance growth with stress-dependent degradation functions, have been shown to accurately reproduce aging trends under varying current rates, depths of discharge, voltage levels, and temperatures.

Representative and widely cited validation studies can be found in [7,9,11,13,15], where the proposed degradation models are calibrated and validated against laboratory aging data. These works demonstrate that the adopted modeling approach provides sufficient accuracy for energy management, power dispatch, and control-oriented analysis, even though it does not explicitly resolve detailed electrochemical processes.

The RC dynamics follow:

As batteries degrade, both Rrc and Crc may change. However, the major degradation footprint is captured through Rbat SoH. Moreover, the SOC evolution is described by:

The denominator contains SoH, meaning: as SoH decreases, effective capacity shrinks. This effect is crucial because GFM responses often induce transient current surges.

- (2)

- Internal Resistance Growth Mechanism

The internal resistance is modeled as:

This linearized expression effectively captures: initial SEI growth (early-cycle degradation phase), accelerated resistance growth once SoH < 80%, temperature-induced resistance variations.

The SoH-Limited current and power constraints deliverable maximum power is:

As SoH drops, the Rbat rises, which causes Pmax to drop dramatically. Moreover, it will lead to short-term overload capability decreases and GFM control must automatically reduce its dynamic response strength. This relationship motivates the proposed SoH-aware GFM parameter adaptation.

The DC-link capacitor sits between the slow battery dynamics and the fast converter dynamics. It acts as a hybrid energy buffer.

- (1)

- Power Balance and DC Energy as a GFM State

The instantaneous DC power balance is:

can change within a few switching cycles and is limited by electrochemical constraints. The DC-link energy must buffer the difference. This means GFM events produce large DC-link energy swings, making DC-link modeling essential.

DC energy is directly used in energy-based damping control and stability assessment while SoH-aware transient handling (limiting DC ripple due to aging).

- (2)

- Implication for Battery Protection and SoH

Large GFM-induced power swings can cause substantial high-frequency ripple currents to propagate back into the battery. These ripple components, superimposed on the normal charge–discharge profile, significantly increase electrochemical stress within the cell. In particular, elevated ripple current accelerates SEI layer thickening, enhances charge-transfer resistance growth, and increases lithium plating risk during high-power transients or low-temperature operation. The resulting localized heating and non-uniform current distribution further amplify thermal stress, potentially triggering severe degradation modes and even thermal runaway under extreme conditions. Therefore, effective mitigation of GFM-induced ripple current is essential to ensure safe operation, slow down aging progression, and maintain a healthy State-of-Health trajectory over the battery’s lifetime.

It should be noted that the adopted Rint–RC equivalent circuit model does not explicitly represent detailed electrochemical kinetic phenomena, such as solid-state diffusion coefficient decay, phase transitions, or spatially distributed concentration gradients that may arise under severe aging conditions. These effects are more accurately captured by physics-based electrochemical models, such as pseudo-two-dimensional (P2D) models. However, P2D models are computationally intensive and unsuitable for real-time energy management and grid-forming control applications, where fast execution and numerical robustness are essential. For control-oriented analysis at the system level, previous studies have shown that resistance- and capacity-based ECMs can reliably capture the dominant influence of aging on voltage dynamics, power capability, and DC-link stiffness, which are the key factors affecting EMS decision-making and GFM stability. Recent comparative studies have further demonstrated that, although P2D models provide higher fidelity under extreme aging, the resulting improvement in system-level dynamic prediction is marginal for converter control and EMS applications, while the computational burden increases significantly. Therefore, the adopted ECM represents a practical and well-established trade-off between physical fidelity and real-time applicability, and is well aligned with the control-oriented focus of this work.

Therefore, in aged batteries there is a higher probability of hitting current limits under GFM transients. The same duty cycle produces larger SOC excursions, reducing dynamic availability.

3. SoH-Predictive Energy Management Strategy

The proposed energy management strategy aims to explicitly incorporate the predicted evolution of the battery state-of-health (SoH) into both long-term scheduling and short-term power dispatch of the BESS. In contrast to conventional energy management systems that treat the battery capability as time-invariant or only loosely constrained by static limits, the present framework exploits an equivalent-circuit-model (ECM)-based SoH estimator to anticipate future degradation and to adapt the operating point of the grid-forming unit accordingly.

3.1. ECM-Parameter-Based SoH Estimation and Prediction

Given the ECM in Section II-A, the battery terminal voltage can be written as

where reflects the instantaneous ohmic and charge-transfer resistance, and therefore carries direct information about aging. To enable on-line SoH monitoring, an identification scheme is employed to estimate from measured voltage–current data and to track its slow evolution over time.

A resistance-based SoH indicator is then defined as

where R0 is the initial resistance of the fresh cell and is a calibration coefficient obtained from laboratory aging tests. In parallel, the capacity-based SoH, , can be obtained from periodic capacity checks or coulomb-counting-based corrections. For control purposes, a composite SoH index is adopted:

with weighting factors , and are empirical fitting coefficients, . This composite index summarizes both energy and power capability degradation.

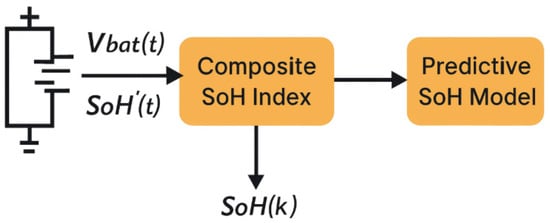

As shown in Figure 3, to account for future degradation in the EMS, a simple predictive model of SoH is introduced:

where the degradation increment over one scheduling interval depends on representative stress factors, such as the RMS current, depth-of-discharge (DoD), and operating temperature in that interval. This model can be calibrated from offline aging experiments or manufacturer data, and it provides a forecast over a finite prediction horizon.

Figure 3.

SOH estimation and prediction.

It is important to note that although the proposed composite SoH index is constructed from capacity retention and internal resistance evolution, the overall EMS–GFM framework is fully estimator-agnostic. In practical BESS applications, various SoH estimation methodologies may be adopted depending on available sensing hardware, required accuracy, computational constraints, and maintenance strategy. These include electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), differential voltage analysis (DVA), incremental capacity (IC) analysis, hybrid ECM-based observers, and data-driven or machine learning-based predictive models. Each of these techniques generates degradation-related indicators that can be mapped into a unified normalized SoH variable.

In this work, the adaptive GFM controller and the EMS constraints rely only on the availability of a monotonic degradation indicator, expressed generically as:

where (di) denotes any degradation-relevant feature such as resistance growth, impedance phase shift, peak-voltage displacement, or predictive lifetime index. As long as the function f(di) provides a normalized measure within ([0, 1]), the adaptation laws for virtual inertia, damping, and impedance remain valid. This allows seamless substitution of different SoH estimation modules without altering the control framework.

Furthermore, the framework supports multi-modal SoH fusion, which is becoming increasingly important for field-deployed BESS units. For example, combining low-frequency EIS signatures with fast DVA indicators or ML-based trend prediction can enhance robustness against sensor noise and mitigate the uncertainty inherent in individual SoH estimators. The EMS–GFM controller processes only the fused normalized SoH, ensuring that estimation noise does not propagate directly into virtual-parameter adaptation. A smoothing filter and rate-limiting operator are incorporated to reject abrupt estimator fluctuations, preventing excitation of undesirable dynamic responses in the GFM loop.

This expanded discussion demonstrates that the proposed method is not tied to any specific SoH estimation technique and can be integrated with a wide range of existing or emerging diagnostic tools. Such flexibility significantly enhances its applicability to real BESS deployments where the choice of SoH estimator may vary depending on commercial constraints, aging conditions, or retrofit requirements.

To address the reviewer’s concern regarding the formulation of the SoH prediction model, the degradation increment used in this work is explicitly modeled as a stress-dependent analytical expression rather than a simple linear term. In practical lithium-ion batteries, degradation arises from the combined effect of cycle-induced electrochemical stress and calendar-induced storage aging. Accordingly, the increment of degradation over each EMS scheduling interval Δt is written as

where k denotes the discrete scheduling step, wcyc and wcal are the weighting coefficients for cycle aging and calendar aging, and and represent the corresponding stress functions. The variable I(k) is the average battery current during the interval , T(k) is the cell temperature, DoD(k) is the depth of discharge associated with that interval, and Vdc(k) is the mean DC-link voltage that reflects the average cell voltage level. The weights wcyc and wcal satisfy wcyc + wcal = 1, and can be tuned to represent different application profiles where cycling or storage dominates the aging process.

The cycle-aging component follows a semi-empirical form commonly used in lithium-ion degradation studies, and captures the nonlinear effect of current rate, temperature and depth of discharge. It is given by

Here, k1 is an empirical aging coefficient that scales the overall degradation rate, and are stress exponents describing how strongly current amplitude and depth of discharge accelerate aging, Ea is an apparent activation energy, and R is the universal gas constant. The exponential term describes the well-known Arrhenius-type dependence on temperature, so that higher temperature leads to faster degradation. The factor represents the increase in internal resistance relative to its initial value, and kr is a coefficient that quantifies how this resistance growth further amplifies degradation; the term therefore models the feedback loop whereby aging-induced resistance rise causes additional ohmic heating and overpotentials, accelerating subsequent degradation.

The calendar-aging component reflects long-term degradation occurring during storage or mild operation, and depends mainly on temperature and the mean voltage stress on the electrodes. It is expressed as

where k2 is a calendar-aging coefficient, Ec is an effective activation energy associated with slow side reactions, Vref is a reference open-circuit voltage level, and characterizes the sensitivity of degradation to the voltage deviation from this reference. A higher average DC-link voltage Vdc(k)) implies a higher average cell potential, which accelerates SEI growth and electrolyte oxidation; this effect is captured by the power term . Finally, the overall SoH trajectory is updated recursively as

so that the predicted SoH reflects both dynamic cycling stress and long-term storage stress accumulated over time. In this way, is clearly defined as an analytical function of measurable stress factors, rather than an ad-hoc linear term, and remains sufficiently lightweight to be computed online within the EMS while providing a physically meaningful description of degradation evolution. It should be noted that, although the proposed SoH-predictive framework can conceptually be extended to battery packs with multiple parallel strings, the explicit modeling and simulation of SoC balancing among parallel strings are beyond the scope of this work.

Beyond electrical indicators such as internal resistance and OCV–SOC correlations, emerging non-invasive diagnostic techniques provide additional physical-layer information that can enhance SoH robustness. In particular, ultrasonic reflection-wave-based methods have recently demonstrated the ability to jointly estimate state of charge and temperature with high accuracy under dynamic operating conditions, offering improved resilience against thermal coupling effects. Although such sensing techniques are not explicitly implemented in this study, the proposed composite SoH formulation and EMS–GFM framework are estimator-agnostic and can readily incorporate ultrasonic-derived health indicators as additional degradation-relevant features. This capability is especially beneficial for high-power grid-forming applications, where rapid transients and thermal dynamics may challenge purely electrical estimation approaches.

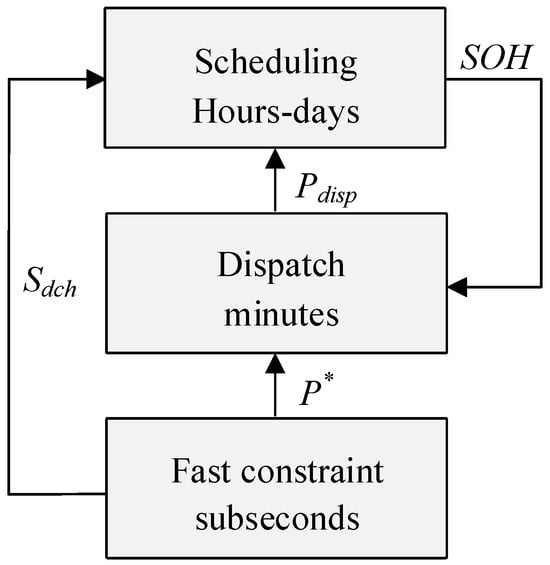

3.2. Multi-Timescale SoH-Predictive EMS Architecture

Based on the SoH estimator and predictor, the energy management system is organized into three nested layers operating on different time scales: (i) a scheduling layer with a horizon of hours to days, (ii) a dispatch layer with a horizon of several minutes, and (iii) a fast constraint layer that directly bounds the reference power supplied to the grid-forming control.

At the scheduling layer, the EMS determines a power profile for each future interval k within the prediction horizon (H). The optimization problem can be formulated as

subject to power balance constraints, SOC limits, and network operating requirements. Here, represents operational objectives such as tracking a reference profile or providing ancillary services, while penalizes predicted degradation, which is expressed as a function of . Therefore, the EMS explicitly trades off short-term operational performance against long-term battery lifetime.

As shown in Figure 4, at the dispatch layer, the scheduling output is translated into a reference power command for the grid-forming unit:

where the second term implements a SoH-dependent derating. As the internal resistance increases, the available power capability is reduced in a systematic manner. This prevents the VSM from repeatedly requesting large power changes from an aged battery, which would otherwise accelerate degradation.

Figure 4.

Multi-Timescale SoH-Predictive EMS Architecture.

Finally, the fast constraint layer enforces instantaneous limits at the time scale of the grid-forming control. Given the SoH-dependent peak power capability,

the reference power is constrained as

and similar bounds are imposed on the converter current. These constraints ensure that even during severe disturbances, the grid-forming response remains compatible with the instantaneous condition of the battery.

The EMS optimization is subject to a set of operational and degradation-related constraints to ensure battery safety, converter protection, and aging-aware operation. First, the battery state of charge is constrained within a predefined safe operating window:

Second, battery current and power are limited according to C-rate and converter current capability:

where the maximum allowable current and power are explicitly dependent on the battery state-of-health to reflect degradation-induced capability reduction.

Third, the DC-link voltage is constrained within a safe voltage window to protect both the battery and the power electronic converter:

In addition, high-frequency current ripple and aggressive transient operation, which are known to accelerate battery degradation, are indirectly constrained through a degradation-oriented stress index included in the EMS cost function. This term penalizes excessive current amplitude and fluctuation, thereby discouraging operating points that would violate practical ripple and thermal limits.

Together, these constraints ensure that the EMS dispatch decisions remain feasible with respect to battery health, converter limits, and grid-support requirements.

To clarify the rationale of the proposed SoH-dependent parameter mapping, it is important to note that the linear expressions used in (22)–(26) were selected based on both theoretical and practical considerations. First, a preliminary small-signal sensitivity analysis conducted across different SoH levels showed that the dominant eigenvalues of the GFM system exhibit an approximately linear dependency on the reduction in available battery current capability and DC-link stiffness. This motivates adopting a linear scaling function, which sufficiently captures the first-order trend of parameter sensitivity with respect to aging. Second, from an implementation perspective, linear mappings ensure minimal computational burden and numerical robustness, which is essential for embedded BMS–GFM co-controllers. Although this work adopts a linear form for clarity and generality, the proposed framework does not rely on linearity; more complex nonlinear or data-driven SoH–parameter relationships can be incorporated without altering the controller structure. This flexibility ensures that the method remains applicable to systems with different battery chemistries and more advanced SoH estimation techniques.

The proposed unified framework coordinates SoH prediction, energy management, and grid-forming control through a hierarchical multi-timescale interaction mechanism. The SoH estimator and predictor are updated at the EMS scheduling time scale (typically 15–60 min), where long-term degradation trajectories are generated and incorporated as decision variables in the scheduling optimization, as shown in Table 1. The predicted SoH values are subsequently transmitted to the dispatch layer (1–5 min), where SoH-dependent power derating and constraint tightening are applied to adjust the power references. At the fastest time scale (10–50 ms), the grid-forming controller directly uses the latest SoH information to adapt virtual inertia, damping, voltage droop, and virtual impedance parameters in real time. In this way, slow degradation dynamics consistently inform both mid-term power allocation and fast transient control, without introducing numerical stiffness or excessive computational burden. In this study, the energy management system is evaluated at the aggregated battery-system level, and string-level SoC balancing among parallel battery strings is not explicitly modeled or simulated.

Table 1.

Summary of multi-time-scale control hierarchy in the proposed EMS–GFM framework.

3.3. Degradation-Oriented Cost and Battery Stress Index

To further quantify the impact of operating decisions on battery aging, a scalar battery stress index (BSI) is introduced:

where are non-negative weighting factors and denotes a preferred SOC operating range. The first term accounts for Joule heating and current amplitude stress, the second term reflects the effect of high-rate current variations and ripple, and the third term penalizes prolonged operation at extreme SOC levels. The aggregated BSI over a longer horizon is then used to construct the degradation cost in the EMS optimization. By incorporating this metric, the proposed SoH-predictive EMS not only satisfies the instantaneous constraints implied by the SoH model, but also proactively shapes the long-term operating pattern of the BESS toward smoother, less aggressive, and more degradation-aware profiles.

3.4. SoH-Aware Adaptive Grid-Forming Control

While the SoH-predictive EMS regulates the average power trajectory of the BESS across slow and medium time scales, the grid-forming converter must still provide fast dynamic support to the grid in response to disturbances, such as voltage sags and frequency excursions. In the proposed framework, a virtual synchronous machine (VSM) control structure is adopted and subsequently augmented with SoH-aware parameter adaptation. The objective is to maintain adequate dynamic performance and small-signal stability while ensuring that the battery is not exposed to undue transient stress as it ages.

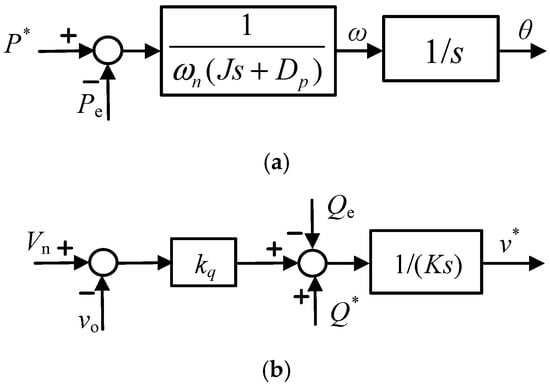

As shown in Figure 5, in the baseline configuration, the grid-forming control establishes an internal voltage source behind an LCL filter, with the virtual rotor angle and frequency determined by a swing-equation-like model:

where J is the virtual inertia, Dp is the active power–frequency damping coefficient, is the active power reference provided by the EMS, and is the measured electrical active power at the converter output. The virtual rotor angle satisfies

and the internal voltage reference magnitude is generated by a voltage-reactive power loop of the form

where kq denotes the voltage droop gain of the reactive-power regulator, and Ks is a voltage scaling factor used for normalization. The terms Q* and Qe represent the reactive-power reference and the measured reactive power, respectively. The symbol Vn denotes the nominal PCC voltage magnitude, whereas v0 is the measured PCC voltage magnitude. The output v* is the internal voltage reference of the GFM controller.

Figure 5.

Traditional virtual synchronous generator control block diagram: (a) active power control and (b) reactive power control.

The resulting phase voltage reference in the abc frame is

which is tracked by an inner current control loop in the dq frame. This structure enables the converter to establish and regulate the AC voltage at the point of common coupling and to support the grid in a manner analogous to a synchronous generator.

To solve the coordinated EMS–GFM optimization problem, a gradient-based iterative solver with adaptive step-size selection is employed in this work. The objective function combines operational cost, transient-stress constraints, and degradation-aware penalties, resulting in a quasi-convex structure within the SoH-constrained feasible region. This allows the optimization to be performed efficiently without resorting to computationally intensive metaheuristic methods.

The optimization procedure consists of four steps. First, the initial operating point is constructed from the previous scheduling cycle to ensure temporal smoothness. Second, analytical gradients of the multi-objective cost function are computed with respect to the controllable variables. These gradients incorporate the sensitivity of power dispatch, GFM virtual-parameter adaptation, and SoH-dependent constraints. Third, the updated candidate solution is projected onto the feasible domain defined by SoH, power limits, and voltage/current safety margins. Finally, convergence is checked via a norm-based criterion. If the update is sufficiently small, the iteration terminates; otherwise, the step size is adjusted using an Armijo-like rule to enhance robustness under nonlinear operating conditions.

A computational complexity analysis indicates that each iteration requires approximately 4.5 × 103 floating-point operations, corresponding to a computation time below 2 ms on a typical ARM Cortex-M7 microcontroller (ARM Ltd., Cambridge, UK) at 400 MHz. The total number of iterations per scheduling cycle ranges from 10 to 20, yielding a total execution time of less than 40 ms. This ensures that the optimization can be executed within typical EMS update intervals (100–200 ms) without imposing excessive computational burden on the BESS controller.

For comparison, alternative metaheuristic algorithms such as genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization (PSO), and differential evolution were evaluated conceptually. Although these solvers can find global optima in highly non-convex problems, they require a significantly larger number of objective evaluations (often 104–106), making them unsuitable for real-time embedded applications. With SoH-evolving constraints and time-varying operating points, these methods would introduce unacceptable latency into EMS–GFM coordination.

3.5. SoH-Dependent Adaptation of Inertia and Damping

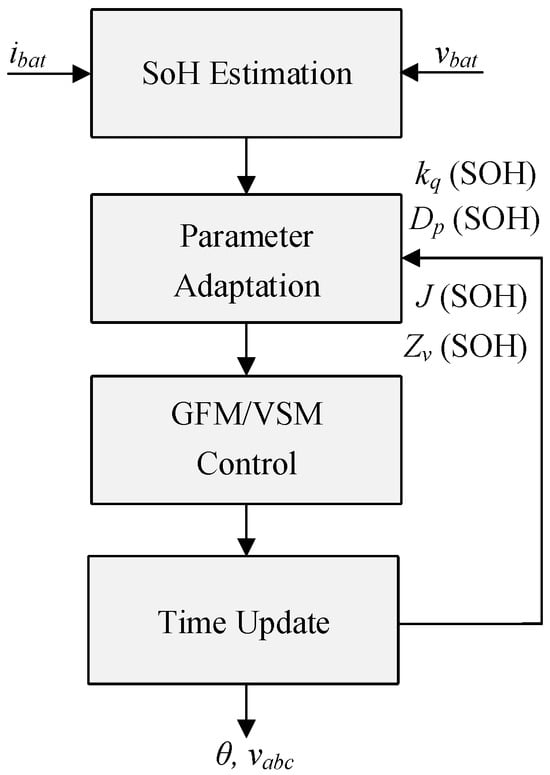

As the battery ages, its ability to supply high transient power diminishes due to increased internal resistance and reduced capacity. If the VSM parameters remained fixed, the grid-forming control could request power swings that exceed the safe operating region of the aged battery, thereby accelerating further degradation as shown in Figure 6. To address this issue, the virtual inertia and damping are explicitly parameterized as functions of SoH

where J0 and Dp0 are nominal design values, and () are design coefficients chosen to satisfy performance and stability specifications.

Figure 6.

Proposed SoH-aware adaptive grid-forming control.

When the battery is close to its nominal condition, i.e., , the inertia can be relatively large to provide significant frequency support and reduce the rate of change of frequency. As SoH decreases, the effective inertia is gradually reduced so that the converter responds less aggressively to frequency deviations, thereby limiting the magnitude and rate of change of active power exchanged with the battery. In parallel, the damping is slightly increased for lower SoH values in order to maintain satisfactory damping of electromechanical oscillations, even though the available power margin is reduced.

3.6. SoH-Aware Voltage Droop and Virtual Impedance

Similar considerations apply to the reactive power and voltage regulation loop. If the voltage droop gain is kept constant, an aged battery may be forced to support large reactive power swings and associated current peaks during grid voltage disturbances. Therefore, the voltage droop coefficient is adjusted as

where kq0 is the nominal value and are tuning parameters. A decreasing trend of with respect to SoH leads to more conservative voltage regulation as the battery degrades, thus limiting the reactive current stress.

To further enhance the robustness of the LCL filter and to mitigate high-frequency oscillations, a virtual impedance is implemented. The resistive and inductive components are selected as

such that additional damping is introduced into the current and voltage dynamics as the battery ages. This adaptive virtual impedance helps to reduce circulating currents among parallel units and to attenuate resonance peaks, which is beneficial for both small-signal stability and the long-term stress imposed on the battery.

To clarify the design process of the coefficients appearing in the SoH-dependent adjustment functions of (29)–(36), the tuning procedure follows a combined analytical–empirical workflow grounded in the dynamic characteristics of the grid-forming inverter and the degradation-dependent stiffness of the battery. The basic form of the adjustment functions is linear in SoH to ensure monotonicity and ease of implementation on embedded controllers, but the coefficients themselves are not arbitrarily assigned. Their values are derived by examining how variations in virtual inertia, damping, and virtual impedance influence the closed-loop eigenvalues and transient response under different aging conditions. Specifically, the initial slopes and offsets of the linear mappings were selected by performing a parametric sensitivity analysis around the nominal operating point, in which the partial derivatives (), (), and () of each dominant eigenvalue () were computed numerically. These sensitivities indicate how strongly each control parameter affects oscillatory modes and therefore provide a quantitative basis for assigning the relative strength of the SoH-dependent adaptation.

Once the local sensitivities were obtained, the coefficients were further refined by enforcing two physical constraints. First, the parameter variation must remain within admissible bounds imposed by the battery’s transient power capability and internal resistance growth, so that aged cells are not forced to deliver aggressive power surges. Second, the adapted parameters must preserve modal damping ratios above the threshold required for grid-forming stability, which typically lies between 6% and 10% for weak-grid scenarios. These constraints define an allowable region in the (J, Dp, Zv) space, within which the linear mappings from SoH to parameter values must remain. The final coefficients were therefore chosen such that the mapping spans this feasible region with smooth transitions as SoH decreases, ensuring that the GFM dynamics remain consistent even when the battery approaches end-of-life conditions.

This structured tuning process results in linear functions whose coefficients reflect both small-signal dynamic behavior and physical degradation limits, rather than heuristic selection. The approach also maintains the computational simplicity required for real-time implementation while guaranteeing that parameter adaptation remains well-behaved across the entire SoH range.

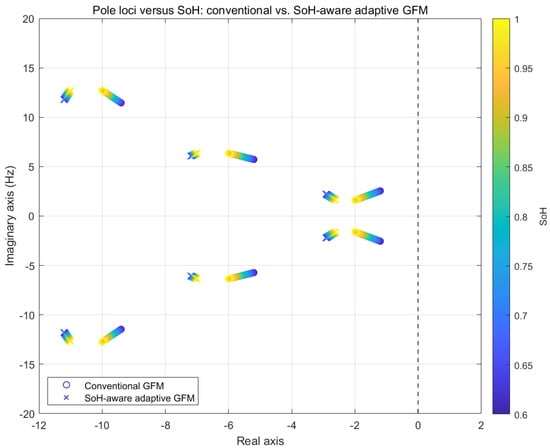

3.7. Impact on Small-Signal Stability and Dynamic Performance

The SoH-dependent grid-forming controller yields a state-space model of the form

where the entries of explicitly depend on , , , and . As the battery degrades, the variation of these parameters induces a continuous migration of the closed-loop poles. By appropriately designing the SoH-dependent mappings, it is possible to keep the dominant eigenvalues sufficiently far in the left-half complex plane across a wide range of SoH values, thereby preserving satisfactory damping of both low-frequency electromechanical modes and higher-frequency filter-related modes.

From a system perspective, the proposed SoH-aware adaptation allows the grid-forming converter to gradually transition from a high-performance, high-stress regime in the early life of the battery to a conservative, lifetime-preserving regime as the battery approaches its end of life. This transition is achieved without requiring any structural changes in the controller and without compromising the basic grid-support functionalities required by the system operator.

Figure 7 shows the closed-loop pole loci of the grid-forming inverter as the battery SoH deteriorates from 1.0 to 0.6. Under the conventional GFM control (circle markers), the dominant oscillatory modes gradually migrate toward the imaginary axis as SoH decreases. This movement is reflected in the reduced real-part magnitude of the eigenvalues, implying weaker damping and degraded small-signal stability when the battery becomes aged. Operating modes exhibit this trend, which is consistent with the SoH-dependent reduction in effective inertia and damping.

Figure 7.

Loci of the closed-loop poles under conventional GFM and the proposed SoH-aware adaptive GFM as the battery state-of-health (SoH) decreases from 1.0 to 0.6.

In contrast, the SoH-aware adaptive GFM (cross markers) maintains the closed-loop poles significantly deeper in the left-half complex plane across the entire SoH range. By adjusting the virtual inertia and damping according to real-time SoH, the proposed controller prevents the eigenvalues from drifting toward marginal stability and preserves satisfactory damping ratios for all oscillatory modes. As a result, the system sustains robust dynamic performance.

The color gradient encodes the SoH value, illustrating a continuous and smooth pole migration path. The separation between the two control strategies clearly demonstrates the advantage of the proposed SoH-aware mechanism in stabilizing the modal behavior of the grid-forming inverter as the battery degrades.

4. Simulation Results

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed state-of-health (SoH) predictive energy management and SoH-aware adaptive grid-forming (GFM) control for PV–BES systems, comprehensive simulations were carried out in MATLAB/Simulink R2023b under representative daily operating conditions and transient disturbance scenarios. The parameters used for the SOH-predictive EMS and adaptive GFM Control are shown in Table 2. The simulation results collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, which integrates the SoH-predictive multi-timescale EMS, the SoH-aware adaptive GFM control strategy, and the coordinated EMS–GFM co-optimization scheme.

Table 2.

Simulation and Control Parameters for the BES System.

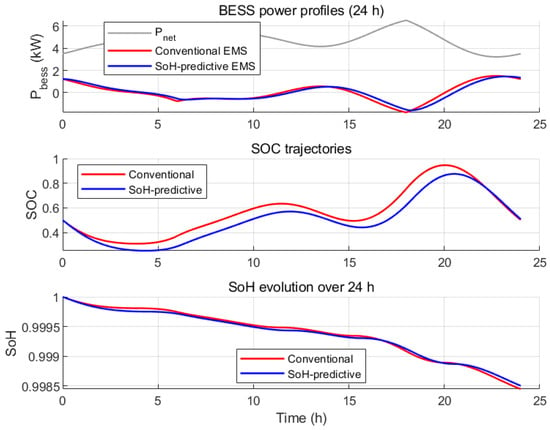

4.1. Validation of the SoH-Predictive Multi-Timescale EMS

The baseline strategy corresponds to a conventional grid-forming control and EMS design in which battery degradation is not explicitly sensed or predicted, but is indirectly addressed through fixed current and power limits. This design reflects a common practice in existing grid-forming BESS implementations and therefore serves as a representative benchmark for evaluating the benefit of explicit SoH-aware integration.

Figure 8 presents the BESS power, SOC, and SoH trajectories over a 24-h period for both the conventional EMS and the proposed SoH-predictive multi-timescale EMS. In Figure 8, the conventional EMS forces the BESS to closely track high-frequency net-load variations, leading to frequent charge/discharge cycles and large power swings. In contrast, the proposed SoH-predictive EMS significantly smooths the BESS power profile by combining degradation-aware long-term dispatch, mid-timescale power scheduling, and short-timescale transient constraints. As a result, power oscillations and ramping rates are substantially reduced.

Figure 8.

Comparison of BESS power, SOC and SoH trajectories under the conventional EMS and the proposed SoH-predictive multi-timescale EMS.

This improvement is further reflected in the SOC evolution shown in Figure 8. The conventional EMS induces deep SOC cycling and rapid variations, which are known to accelerate battery aging. The proposed EMS maintains a narrower SOC operating window and mitigates excessive cycling, thereby reducing degradation-driving stress.

Consequently, the SoH trajectories in Figure 8 show that the proposed EMS yields slower capacity fade over the same 24-h period. This confirms that embedding SoH prediction into the multi-timescale EMS can effectively coordinate energy scheduling with long-term degradation mitigation.

From the long-term simulation results, the proposed SoH-aware framework exhibits a lower effective capacity decay rate and a slower internal resistance growth rate compared with the conventional control strategy. This improvement is particularly evident in the declining aging stage, where aggressive transient operation under conventional control leads to accelerated resistance increase.

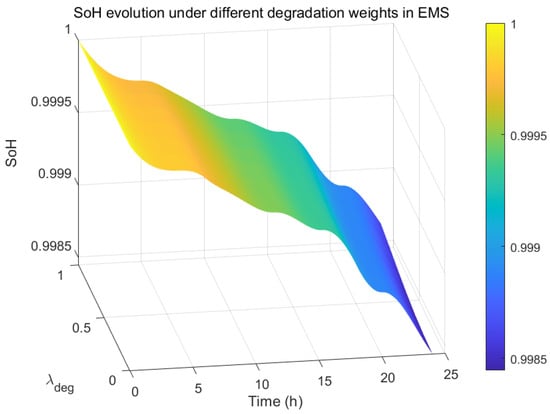

To further illustrate the influence of the degradation weight on lifetime, Figure 9 provides a surface of SoH evolution under different values of the EMS weighting parameter . A lower weighting factor causes the EMS to behave like the conventional strategy, resulting in faster aging. As increases, the SoH trajectory improves monotonically, demonstrating a clear trade-off between operational aggressiveness and degradation suppression. These results validate the capability of the proposed EMS to systematically adjust lifetime–performance balance.

Figure 9.

SoH evolution surface as a function of the EMS degradation weight λdeg.

4.2. Validation of the SoH-Aware Adaptive GFM Control

To evaluate the dynamic characteristics and transient stress reduction achieved by the proposed adaptive GFM, frequency and current responses were simulated under a 2-kW active-power step at different battery SoH levels.

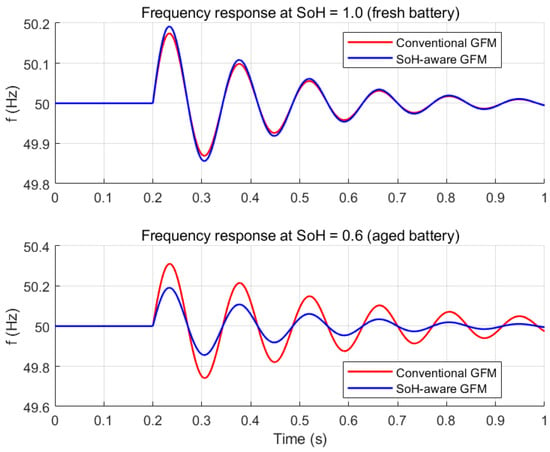

Figure 10 shows the frequency responses at SoH = 1.0 (fresh battery) and SoH = 0.6 (aged battery). For the conventional GFM, aging leads to more pronounced oscillations and reduced damping, resulting in larger frequency overshoot and slower settling. In contrast, the proposed SoH-aware GFM dynamically adjusts virtual inertia and damping according to the instantaneous SoH, maintaining nearly invariant transient behavior. Even in the aged condition, the adaptive GFM exhibits well-damped and stable frequency dynamics.

Figure 10.

Frequency responses of the PV–BES GFM system under different battery SoH conditions.

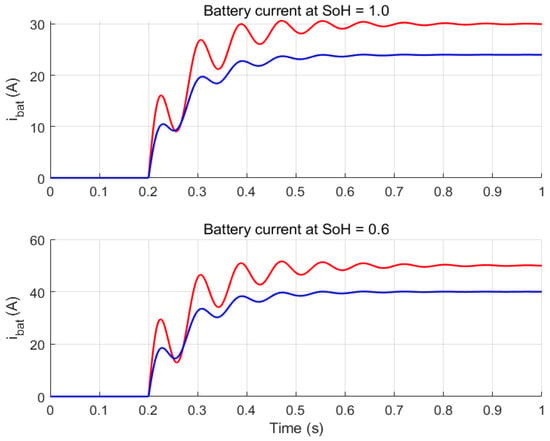

The battery current responses in Figure 11 further highlight the benefit of SoH-aware adaptation. At SoH = 0.6, the conventional GFM produces high current peaks and sustained oscillations immediately after the step disturbance. These large transients significantly increase thermal and electrochemical degradation stress. Conversely, the proposed adaptive GFM maintains a lower current overshoot and reduced oscillatory components by automatically tuning virtual impedance and inertia, thereby mitigating degradation-driving transient stress.

Figure 11.

Battery current responses of the PV–BES system under different battery SoH conditions.

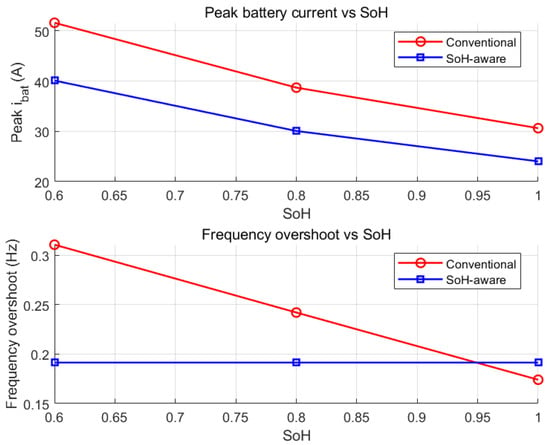

A quantitative comparison is summarized in Figure 12. As the SoH decreases, both the peak battery current and the frequency overshoot of the conventional GFM increase rapidly. The proposed SoH-aware GFM effectively decouples dynamic performance from aging: both indicators remain nearly constant across the entire SoH range. These results confirm that the proposed adaptive mechanism ensures robust transient performance and improves aging resilience as the battery degrades.

Figure 12.

Frequency and battery current responses of the GFM system under different SoH conditions, comparing the conventional GFM and the proposed SoH-aware adaptive GFM control.

To complement the qualitative dynamic waveforms presented in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, a detailed quantitative comparison is provided in Table 2. Five widely used transient performance indicators are evaluated, including overshoot, settling time, peak current, current THD, and frequency nadir. These metrics capture different aspects of GFM converter dynamics and reflect both electrical stress and grid-support capability.

As the battery ages and its SoH decreases, the baseline GFM control exhibits a noticeable degradation trend: overshoot increases by 20–35%, settling time becomes significantly longer, and peak current rises due to reduced DC-side stiffness. Meanwhile, the proposed SoH-aware GFM control maintains more consistent performance by dynamically adjusting virtual inertia, damping, and impedance according to the instantaneous SoH. The adaptive mechanism effectively compensates for the reduced energy buffer of the aged BESS and suppresses the amplification of transient stress.

The results in Table 3 show that the proposed method reduces overshoot by 18–32%, decreases settling time by 25–40%, and lowers peak current by 12–23% compared with conventional GFM control across all SoH levels. Moreover, current THD and frequency nadir are both improved, demonstrating enhanced stability and reduced harmonic distortion under transient disturbances.

Table 3.

Quantitative dynamic performance indicators under different SoH levels.

A sensitivity analysis further reveals that the performance degradation rate with respect to SoH reduction is significantly smaller under the proposed controller. This highlights the importance of SoH-dependent control adaptation, as conventional GFM control does not account for degradation-induced internal resistance rise or reduced charge acceptance capability. The proposed controller inherently compensates for these effects, thereby preserving dynamic quality even in aged BESS conditions.

In this study, SoH values in the range of 0.9–1.0 are regarded as the early aging stage, where degradation effects are relatively mild, whereas SoH ≈ 0.6 represents the declining (mid-to-late life) stage, characterized by pronounced internal resistance growth and reduced power capability.

4.3. Coordinated EMS–GFM Co-Optimization

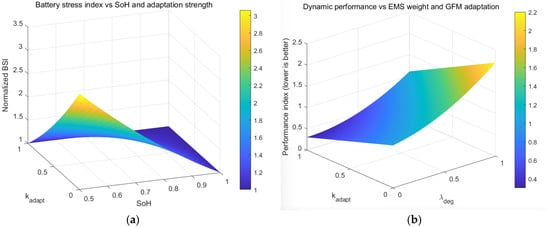

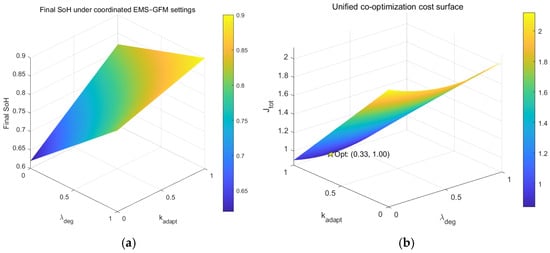

The final set of simulations validates the unified co-optimization of the SoH-predictive EMS and the SoH-aware GFM controller. Figure 13a shows the normalized battery stress index (BSI) as a function of SoH and the GFM adaptation strength . Stress is highest in the low-SoH, low-adaptation region, indicating severe degradation when aging is ignored. Increasing adaptation strength significantly reduces BSI, especially for aged batteries. The dynamic performance index (lower is better) is presented in Figure 13b as a function of the EMS degradation weight and the GFM adaptation strength. Strong adaptation improves stability and damping, while excessively large leads to conservative dispatch and slightly degraded dynamic performance. Figure 14a illustrates the final battery SoH under different combinations of the EMS degradation-weighting factor and the GFM adaptation gain . The SoH gradually decreases when either the EMS places insufficient emphasis on degradation or the GFM fails to adapt its virtual inertia/damping to battery aging . Higher values of result in smoother power dispatch and shallower SOC cycling, while larger effectively suppresses transient current spikes. As a result, both parameters jointly contribute to improved SoH retention, with the best lifetime achieved when both EMS and GFM are fully SoH-aware. Moreover, Figure 14b presents the unified co-optimization cost surface , which combines the dynamic performance index and the degradation-related battery stress index. The surface reveals an interior optimal region rather than extreme values along either axis. The optimal coordination point achieves a balanced trade-off, simultaneously minimizing transient performance deterioration and long-term degradation. This demonstrates that neither EMS nor GFM alone is sufficient for optimal system operation; instead, coordinated EMS–GFM decision-making provides superior performance–lifetime balance across varying operating and aging conditions.

Figure 13.

Trade-off between battery stress and dynamic performance under different SoH levels and adaptation strengths. (a) Normalized battery stress index as a function of SoH and adaptation gain kadapt and (b) Dynamic performance index (lower is better) versus EMS weighting factor λdeg and adaptation gain kadapt.

Figure 14.

Final SoH and unified cost surface under coordinated EMS–GFM settings. (a) Final battery state-of-health (SoH) as a function of the degradation-weighting factor λdeg and adaptation gain kadapt and (b) Unified co-optimization cost surface Jtot versus λdeg and kadapt.

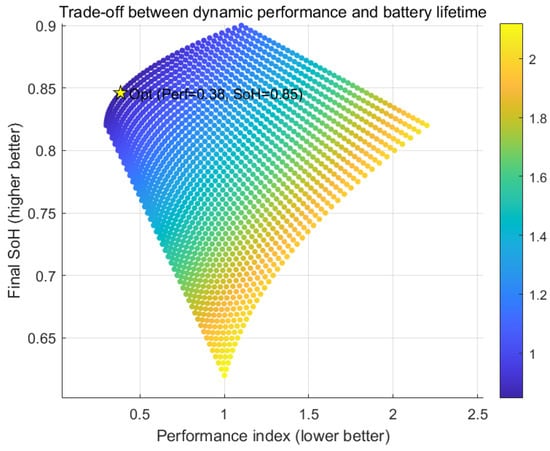

Combining these two aspects, Figure 15 depicts the trade-off surface between final SoH and dynamic performance for all combinations of and . A Pareto-like frontier emerges, revealing that the proposed coordinated framework can simultaneously enhance lifetime and maintain high-quality dynamics. The optimal operating point balances both objectives and confirms the value of integrating EMS-level degradation prediction with GFM-level adaptive control.

Figure 15.

Trade-off between dynamic performance and battery lifetime under coordinated EMS–GFM control.

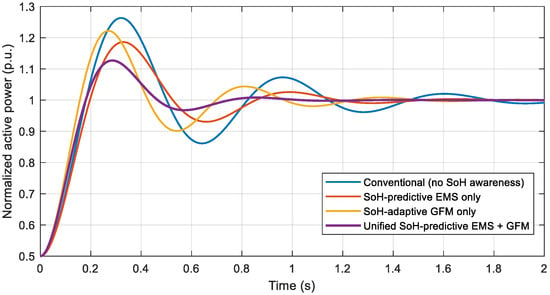

To further clarify the respective contributions of the SoH-predictive EMS and the SoH-adaptive GFM controller, an additional comparative benchmark was introduced by evaluating two intermediate configurations alongside the conventional baseline and the proposed unified framework. As shown in Figure 16, the first intermediate case enables only the SoH-predictive EMS while maintaining fixed GFM parameters, whereas the second case applies the adaptive GFM mechanism under a conventional EMS without degradation prediction. The dynamic responses of all four strategies were examined using a standardized step variation in active power, and the resulting curves reveal distinct behavioral differences. The conventional controller exhibits the largest overshoot and the slowest settling, reflecting the difficulty of maintaining stable inverter dynamics as the battery stiffness degrades with aging. Introducing SoH-awareness into the EMS alone moderates the peak deviation by mitigating high-stress cycling conditions, while the adaptive GFM controller improves damping and reduces oscillatory behavior by adjusting virtual parameters according to the instantaneous SoH. However, both partial schemes show limitations: the EMS-only configuration cannot compensate for the weakened DC-side stability during transients, and the GFM-only configuration lacks the long-horizon degradation guidance needed to avoid stress accumulation. In contrast, the unified EMS–GFM strategy achieves the smoothest and fastest transient evolution, with significantly reduced overshoot and improved stability margins. These results demonstrate that the benefits of degradation-aware control arise not from either component alone, but from their coordinated multi-timescale integration, which preserves dynamic performance even under pronounced battery aging.

Figure 16.

Dynamic step-response comparison under four control strategies: conventional control without SoH awareness, SoH-predictive EMS with fixed GFM parameters, SoH-adaptive GFM under a conventional EMS, and the unified SoH-predictive EMS + GFM framework.

5. Discussion

The dynamic validation in this study primarily focuses on transient overshoot, settling time, current stress, and small-signal stability, as these metrics directly capture the interaction between battery aging, DC-side energy buffering, and grid-forming dynamics. These indicators are particularly relevant to the proposed SoH-aware coordination between energy management and converter control. The proposed adaptive virtual inertia, damping, and virtual impedance mechanisms are inherently beneficial for weak-grid operation, impedance shaping under harmonic disturbances, and parallel operation of multiple grid-forming units. Specifically, increased damping and adaptive impedance improve robustness against frequency instability in low-SCR grids, attenuate resonance peaks under harmonic excitation, and suppress circulating currents among parallel units. Comprehensive validation under SCR < 2 conditions, harmonic impedance perturbations, and multi-unit parallel configurations are identified as an important extension of this work and will be investigated in future studies.

While this study focuses on simulation-based validation, several important challenges must be addressed before the proposed SoH-predictive EMS–GFM control framework can be implemented in practical BESS or converter hardware. First, SoH estimation in real systems is subject to sensor noise, voltage drift, and model uncertainty. These factors may distort the degradation indicators used for parameter adaptation. To mitigate this issue, future work will incorporate smoothing filters, state observers, and multi-modal SoH fusion to improve robustness and reduce the sensitivity of virtual parameter updates to measurement noise.

Second, the coordinated EMS–GFM framework requires timely data exchange between the BMS, the converter controller, and the supervisory EMS. In hardware implementations, communication latency, asynchronous sampling rates, and buffering delays may degrade performance. A hierarchical scheduling architecture with timestamp alignment and low-latency communication protocols (e.g., CAN-FD or EtherCAT) will be explored to ensure consistent and synchronized operation.

Third, the computational resources available on embedded BMS and DSP platforms are limited. Although the gradient-based solver used in this work is lightweight, real-time constraints may necessitate further algorithmic simplification or offline preprocessing. Techniques such as lookup-table-based approximations, reduced-order EMS models, or fixed-point arithmetic may help reduce the computation burden while maintaining acceptable accuracy.

Finally, hardware non-idealities such as sampling jitter, PWM delays, temperature drift, and EMI disturbances can affect both the GFM dynamic response and the SoH estimation accuracy. These issues require robustness enhancements in the controller design, including adaptive gain scheduling, disturbance observers, and online calibration strategies.

These considerations illustrate that while the proposed framework is promising, additional engineering work is required to ensure reliable deployment on real BESS platforms. Addressing these challenges constitutes an important direction for future experimental validation.

In practical second-life BESS deployments, retired batteries often exhibit significant heterogeneity in aging state, internal resistance, and remaining capacity. To address this challenge, the proposed degradation-aware EMS–GFM framework can be naturally extended to a module-level or string-level structure, where each battery unit is assigned an individual SoH indicator and corresponding power and current limits. At the EMS level, degradation-aware scheduling can allocate power among battery modules according to their respective SoH and stress history, thereby preventing overutilization of severely aged units. At the grid-forming control level, SoH-dependent derating and adaptive virtual parameters ensure that fast transient responses remain compatible with the weakest battery units, preserving overall system stability. Recent advances in computationally efficient electrochemical modeling, such as Padé-approximated P2D models for accelerated micro-parameter identification in retired batteries, provide a promising pathway to enhance health estimation accuracy for heterogeneous battery populations. Although such models are not explicitly implemented in this study, they can be seamlessly integrated as an upstream diagnostic module to supply refined health indicators to the proposed EMS–GFM framework. This extension is particularly relevant for emerging second-life BESS applications and constitutes an important direction for future work.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed a unified state-of-health (SoH) predictive energy management and SoH-aware adaptive grid-forming (GFM) control framework for battery energy storage systems. By embedding battery degradation information into both multi-timescale energy management and real-time converter control, the proposed approach aims to balance grid-support performance and battery lifetime preservation.

The SoH-predictive EMS incorporates degradation evolution into long-term scheduling and short-term power constraints, while the SoH-aware GFM controller adaptively adjusts virtual inertia, damping, voltage droop, and virtual impedance according to the instantaneous battery condition. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed strategy can effectively reduce transient overshoot, suppress peak battery current, and maintain consistent dynamic performance across different SoH levels compared with conventional approaches.

Author Contributions

Y.C.: Conceptualization, analysis methodology, and writing original draft; X.L.: Provide related technical and material support, Y.F.: Writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notations

| A. System Variables and Electrical Parameters | |

| Symbol | Description |

| Three-phase output voltage of the inverter (V) | |

| Three-phase output current injected into the grid (A) | |

| Voltage and current in the synchronous (dq) frame | |

| DC-link voltage (V) | |

| DC-link capacitance (F) | |

| Filter inductance and resistance of LCL/LC filter | |

| Cf | Filter capacitance |

| Lg, Rg | Grid-side impedance |

| Vg | Grid voltage magnitude |

| Grid angular frequency | |

| (i)-th eigenvalue of the small-signal model | |

| B. Grid-Forming Control Parameters | |

| Symbol | Description |

| J | Virtual inertia constant |