1. Introduction

The battery is the key component of electric vehicles, storing energy to power the motor. Among various rechargeable batteries, lithium-ion cells dominate EV applications due to their high energy density. Lithium-ion batteries are one of the most important energy sources for electric vehicles, but their performance and lifetime are severely limited by temperature conditions. To ensure the safety of vehicle operation and to reduce range anxiety, there is an urgent need to understand the current situation and to anticipate the development and challenges of the battery thermal management system.

Lithium-ion battery technology is one of the most suitable energy storage options for driving electric vehicles due to its high specific power and high specific energy density. The high capacity of the battery pack poses safety challenges, such as overheating, combustion, and explosion, as the battery heats up during operation.

The general trend in electric transport technology is to develop cells with higher gravimetric and volumetric energy densities (Wh·kg

−1 or Wh·L

−1) to increase the distance traveled per charge [

1]. In addition to energy density, safety and charging time are also critical factors. Pouch-type cells combine high energy density with compactness and lightness, making them attractive for EV applications. Different chemistries (LTO, LFP, and NMC) are used in EVs, but pouch-type NMC cells dominate due to their high energy density. High-capacity batteries extend the driving range but also increase vehicle weight and energy consumption, which highlights the importance of efficient thermal management solutions.

Zhonghao Rao et al. [

2] stated that the optimal operating temperature for a battery is between 25 and 40 °C, and the temperature difference between individual modules should be less than 5 °C to ensure maximum power output and cycle time. Therefore, to meet these operational requirements, a battery thermal management system (BTMS) must be designed and effectively developed.

Thomas Buidin et al. [

3] analyzed existing research related to the types, designs, and thermal operating principles of BTMS used in various lithium-ion battery configurations. Lithium-ion batteries are preferred for EVs, but their cost and energy density limit efficiency [

2]. The performance of EVs strongly depends on battery capacity, with temperature being the most critical factor. Zhao et al. [

4] reviewed electrode modifications to enhance BTMS thermal performance. Battery temperature has a major impact on the charging and discharging rate of the battery. For this reason, temperature management of the EV battery pack is of vital importance, and the design of energy-intensive packs has to use efficient yet sophisticated cooling systems that employ hundreds of cooling channels. Such cooling systems add 10–20% to the battery cost [

5]. Lithium-ion batteries are susceptible to thermal runaway when the electrolyte reaches 70–130 °C. In addition, lithium-ion cells naturally degrade over time due to their operating conditions and state of charge. Temperature has a strong influence on the performance of almost all batteries. Fast charging and high currents increase heat loss in cells [

5,

6].

There are two main sources of heat generation in a battery cell: electrochemical action and joule heating by the movement of electrons. A temperature range of 25–40 °C provides ideal working conditions for lithium-ion batteries, while temperatures above 50 °C are detrimental to battery life. Elevated temperatures accelerate parasitic side reactions according to the Arrhenius law, leading to faster electrolyte decomposition and destabilization of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). This increases internal resistance, promotes gas generation, and reduces life cycle. Recent studies also emphasize the importance of predictive modeling for battery aging trajectories. For instance, Wang et al. [

7] proposed a transferable generative pretrained transformer (TransLoRA-GPT) capable of forecasting SOH degradation from partial charging data, highlighting the growing role of advanced data-driven methods in understanding battery reliability.

Even immature deterioration of a single cell can significantly reduce the performance and efficiency of the entire battery. The main objective of BTMS is to regulate the temperature of the battery cells to increase lifetime [

8,

9]. Conventional BTMS systems are divided into active and passive cooling. Active cooling involves forced circulation of air, coolant, or mixed techniques, typically using fans and pumps [

9]. Passive cooling uses heat pipes, hydrogels, and PCMs, but poor conductivity limits performance. Composite PCMs with graphite or metal additives improve heat transfer [

10,

11]. Despite many theoretical alternatives [

12], EV manufacturers prefer liquid cooling with conductive plates due to stability, cost, and simplicity [

9,

13,

14]. Coolants with additives such as glycol or nanoparticles further enhance heat transfer [

15]. Recent studies on cylindrical 21700 cells have demonstrated the importance of cooling plate design parameters for effective BTMS [

16]. Recent experimental work has investigated pouch-type Li-ion cells cooled with mini-channel plates, showing that optimized plate geometry can effectively reduce heat generation and improve thermal uniformity under high C-rate operation [

14]. A recent comprehensive review has summarized global advancements and challenges in BTMS, emphasizing the need for innovative cooling strategies to meet the demands of modern EV applications [

17]. This work provides a broad perspective that complements experimental studies by situating BTMS development within long-term technological trends. Together, these studies and reviews underline the urgent need for effective BTMS solutions in modern EVs.

Cicconi et al. [

18] conducted an analysis of the thermal behavior of a lithium-ion battery using a three-dimensional model, which was experimentally validated under a driving cycle.

Geesoo Lee et al. [

19] used FireM Multiphysics CFD software to investigate and analyze the electrical and thermal behavior of a pouch-type lithium-ion battery. They developed a model and examined its performance under different charging conditions.

Ansys Fluent is recognized as one of the most advanced platforms for computational modeling, offering robust capabilities for the thermal analysis of lithium-ion batteries. The software supports multi-scale multi-domain (MSMD) modeling, which enables the simultaneous simulation of electrochemical and thermal processes within the battery [

20]. This integrated approach is particularly critical for evaluating heat generation resulting from Joule heating and electrochemical reactions, especially under high C-rate conditions.

In a recent study, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis was employed to investigate the thermal behavior of a lithium-ion battery pack utilizing air-cooling strategies. A three-dimensional model was developed to assess temperature distribution, heat flux, and cooling efficiency under various operational scenarios. The findings indicated that relatively simple air-cooling configurations can be optimized to reduce temperature gradients, thereby enhancing battery safety and extending operational lifespan [

21,

22].

Another investigation using Ansys Fluent explored the thermal responses of different battery pack formats, including prismatic, cylindrical, and pouch-type cells. The simulations revealed that pouch-type cells exhibit greater sensitivity to temperature non-uniformity, underscoring the need for more effective thermal management strategies tailored to this cell format [

23].

The aim of this research is to develop and validate a numerical model of pouch-type lithium-ion battery cells that accurately predicts thermal behavior under various charging and discharging conditions, and to experimentally investigate temperature distribution and gradients across the cell face surface. The study seeks to quantify thermal non-uniformity and assess the impact of C-rate on cell heating, with the goal of informing the design of effective cooling strategies for battery module development.

This study uniquely focuses on the thermal non-uniformity of pouch-type cells, with special attention to face cooling implications, combining NTGK modeling and thermal imaging validation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of the Numerical Study

Based on the actual dimensions of the cell, a 3D model was created in Ansys software, consisting of 92,418 nodes and 76,312 elements, as shown in

Figure 5.

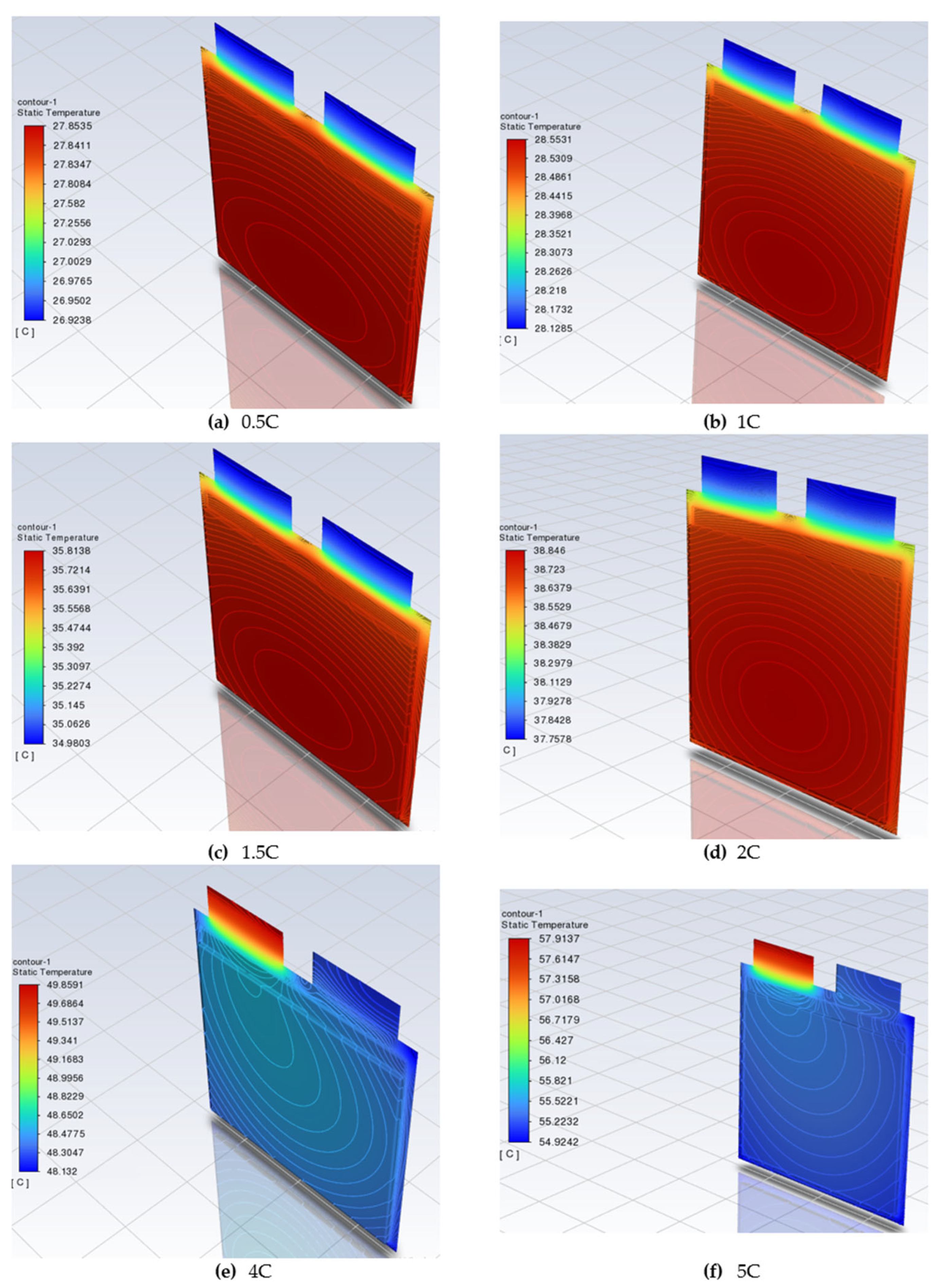

The tested battery cell was discharged at 0.5 C, 1 C, 1.5 C, 2 C, 4 C, and 5 C, and calculated temperatures of the battery cell are presented in

Figure 6. The discharge loads and timing of the battery were set in the Ansys battery module. The manufacturer’s technical specification for the cell specifies a minimum battery cell voltage that cannot fall below 2.7 V.

Summarizing the simulation results with one KOKAM KCL216057PN battery cell at different loads showed that the maximum recommended temperature of 35 °C was not reached at 0.5 C and 1 C loads. The highest temperature was recorded in the cell body at the junction between the contacts and the body. At loads of 1.5 C, 2 C, 4 C, and 5 C, the maximum recommended temperature was exceeded, and at loads of 4 C and 5 C the maximum permissible battery cell temperature was also exceeded. Additional cooling is required to operate the battery cell at these loads.

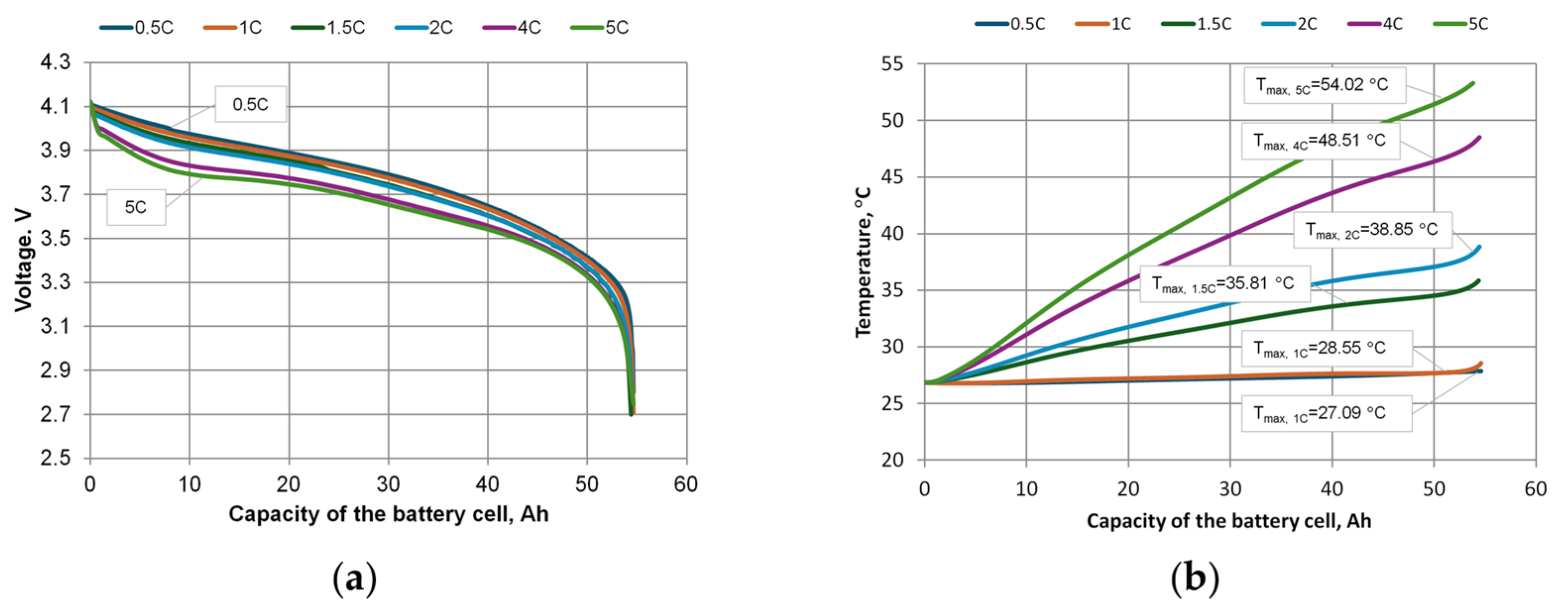

The results of the simulation performed by the Ansys software are presented in

Figure 7. They show the dependence of voltages (

Figure 7a) and temperatures (

Figure 7b) on battery cell capacity at different discharge rates. The voltage graphs correspond to the physics of the cell discharge process, as when discharged at a higher rate, the voltage drop at the beginning of the discharge process is greater.

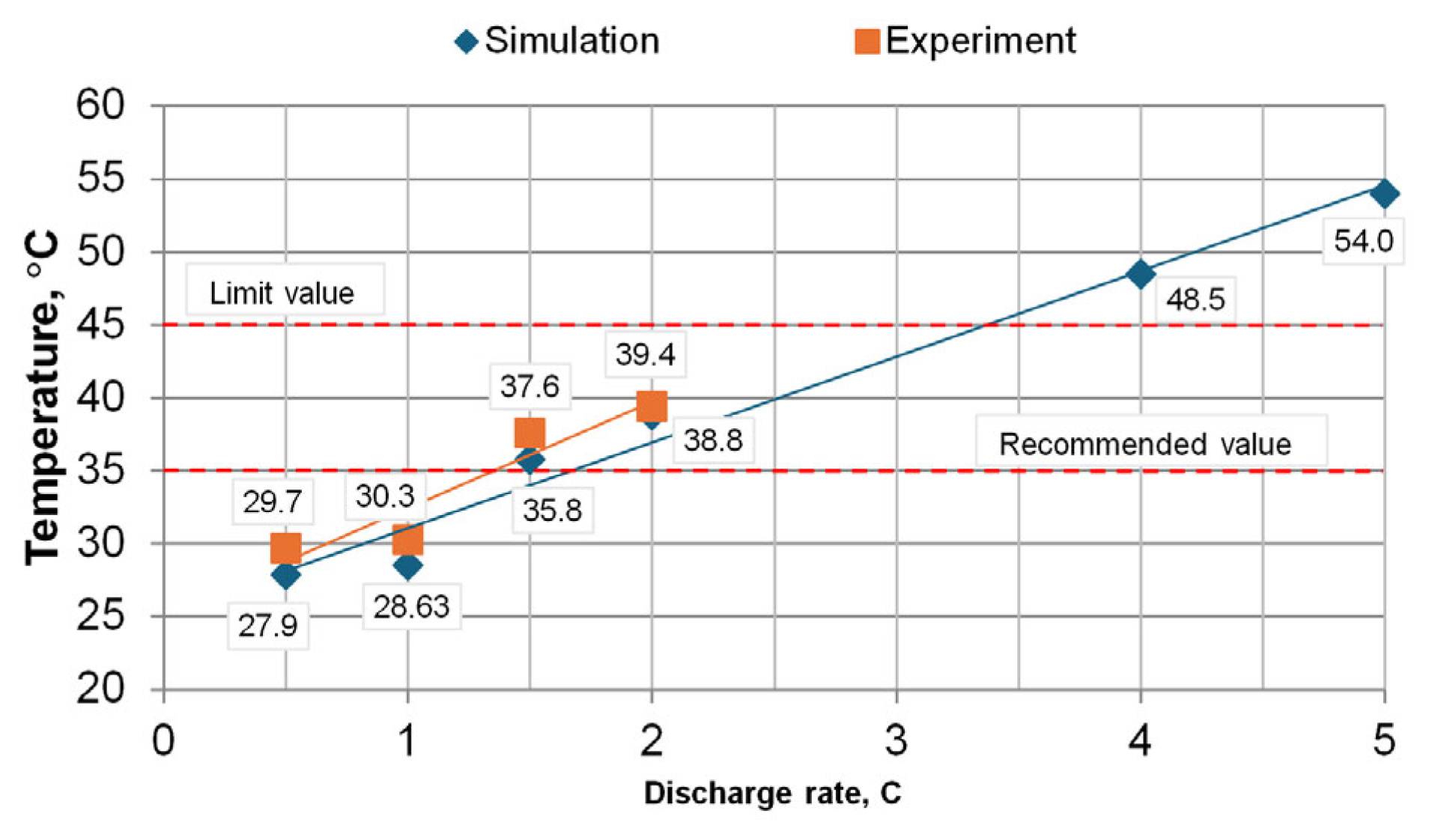

The temperature results obtained from the Ansys simulation of the battery module (

Figure 7b) were compared with the experimental data, which are shown in

Figure 8 and

Table 2. The analysis and the calculation of the percentage deviations showed that the average difference between the simulation and the experimental data is about 4.54%, which suggests that the created battery model has sufficient accuracy and can be considered as a reliable tool for engineering calculations.

3.2. Results of Experimental Studies

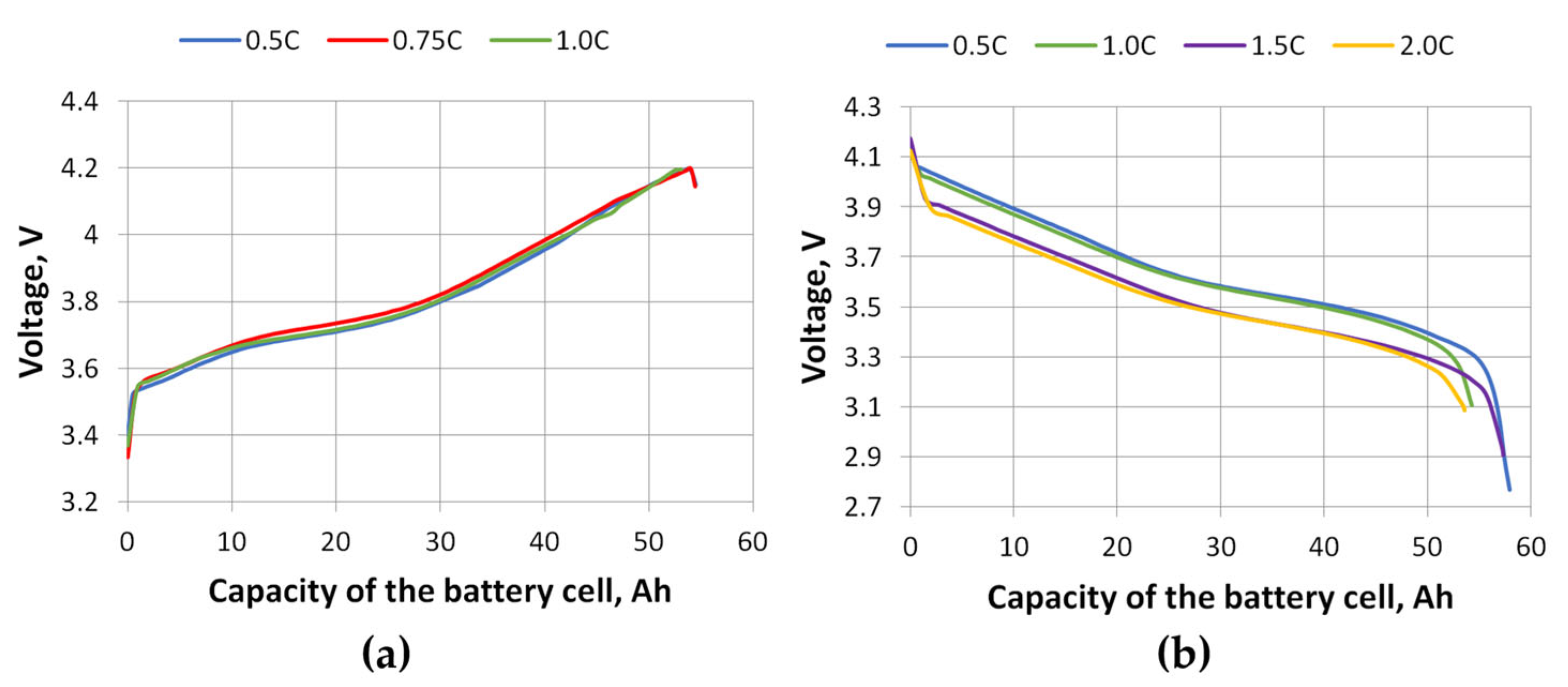

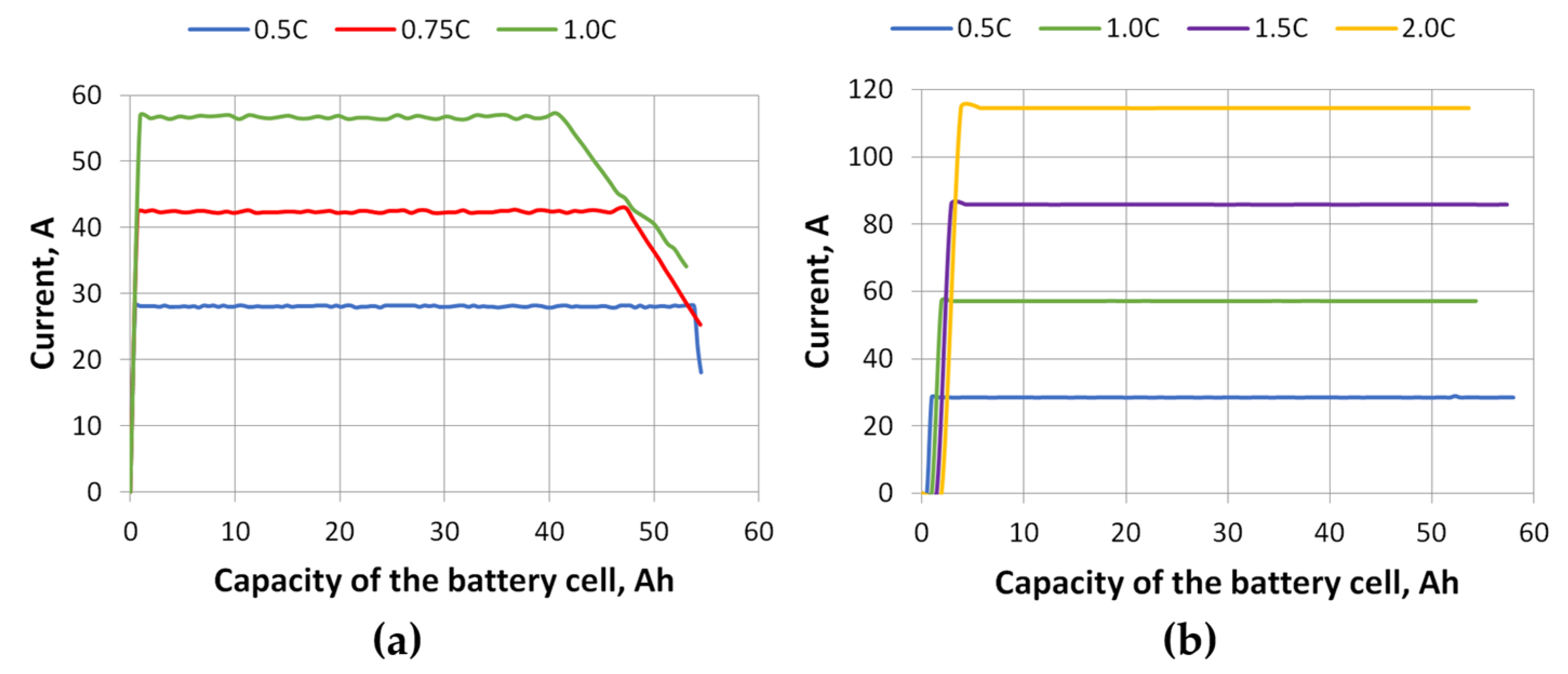

At the start of this study, the battery cell was fully charged and discharged, charging up to 4.2 V and discharging until the battery cell voltage dropped to 2.7 V. The graphs of the battery cell voltage variation during charging and discharging are shown in

Figure 9, and the charging and discharging current change in relation to the battery cell capacity is shown in

Figure 10. The results of the voltage drop simulation (

Figure 7a) are similar to the experimental results (

Figure 9b). This can be explained by the fact that when a lithium-ion battery is discharged at higher C-rates, the terminal voltage drops more sharply due to increased internal resistance and accelerated electrochemical polarization. This initial voltage drop reflects the battery’s limited ability to maintain stable ion transport under high current demand [

28].

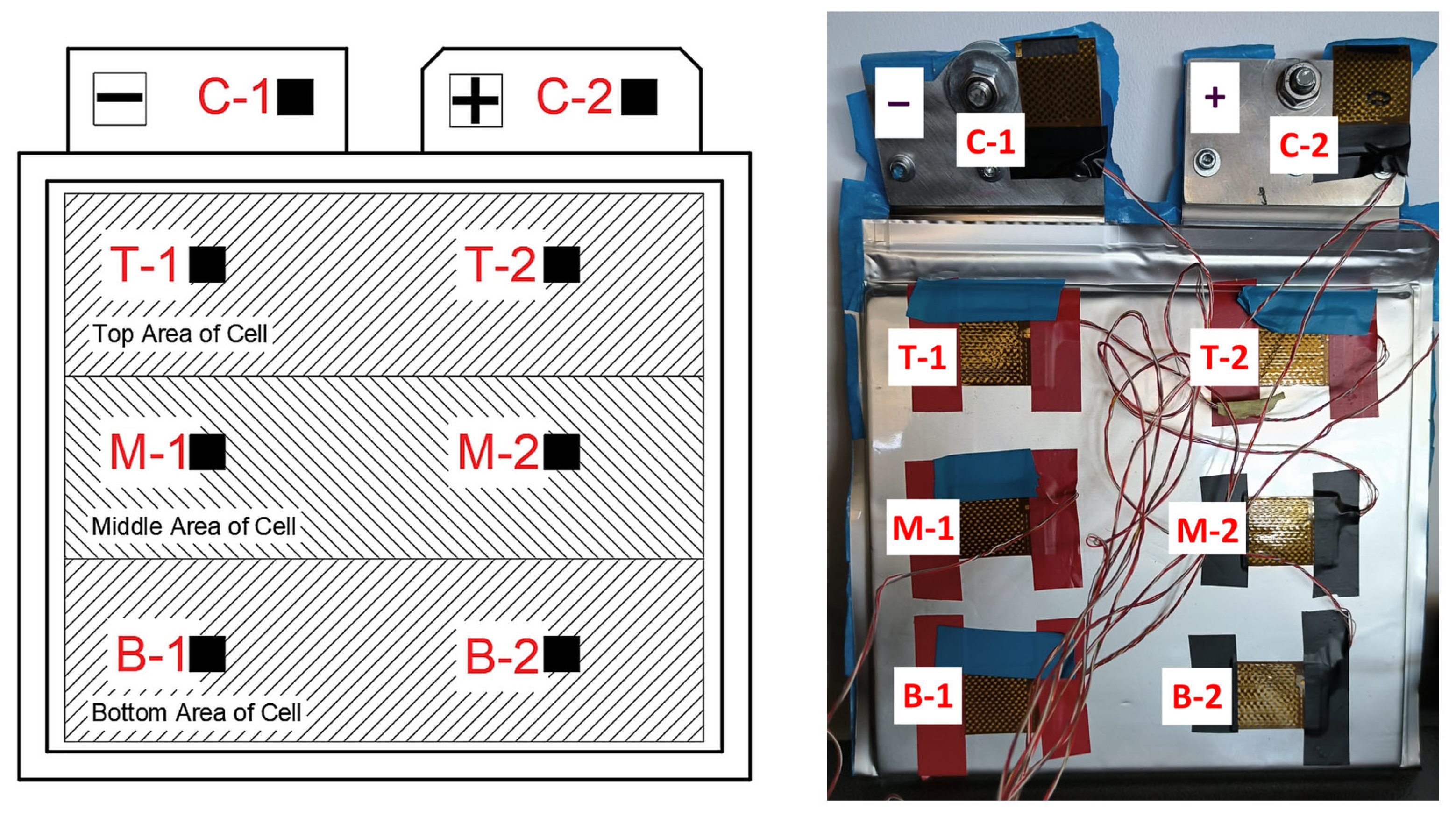

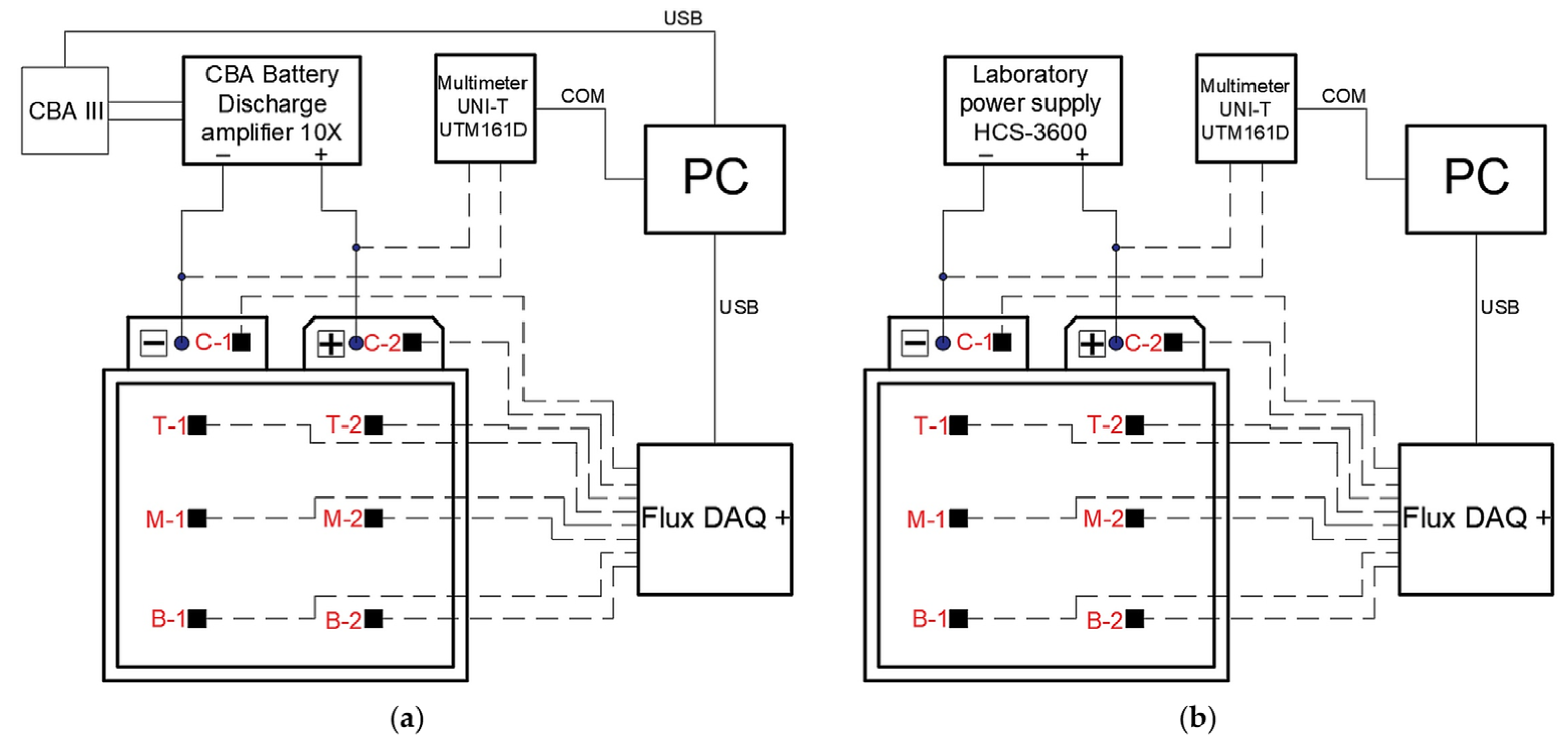

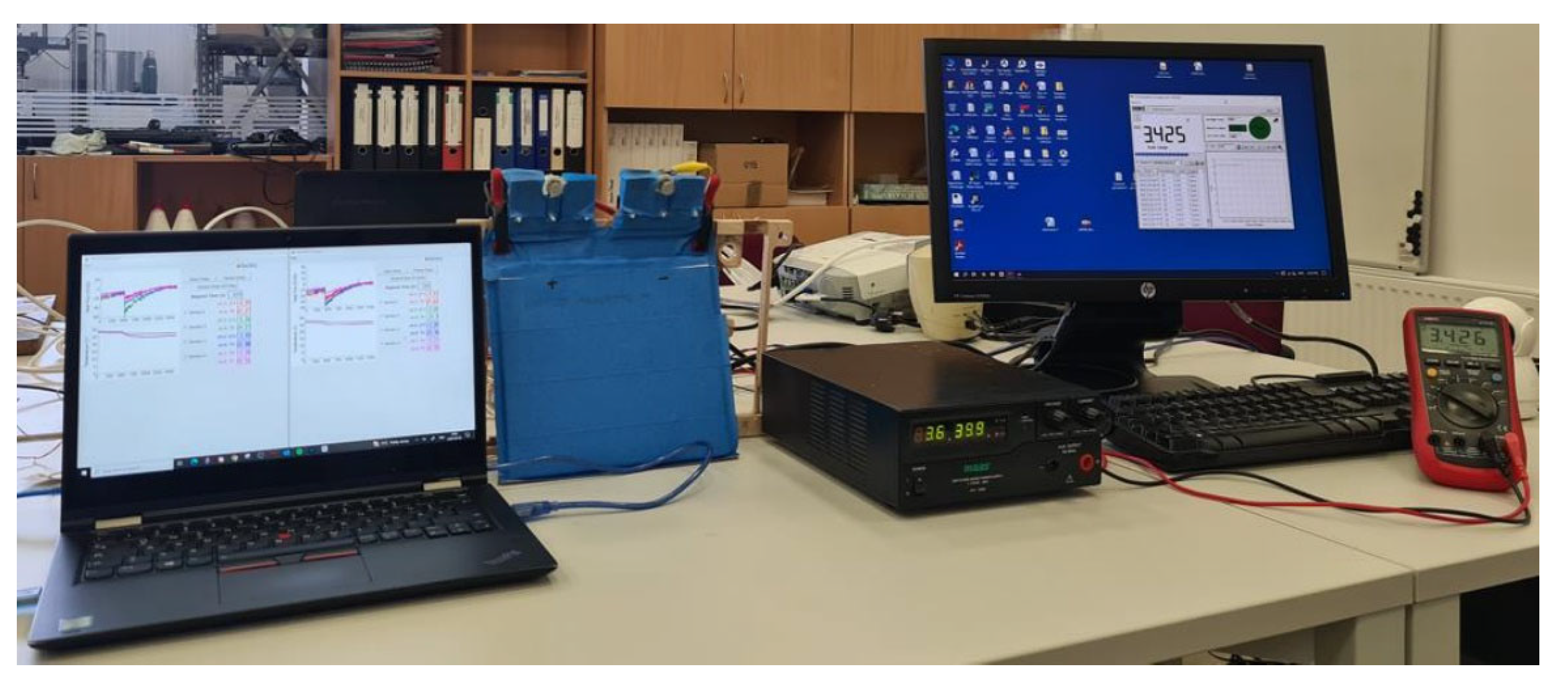

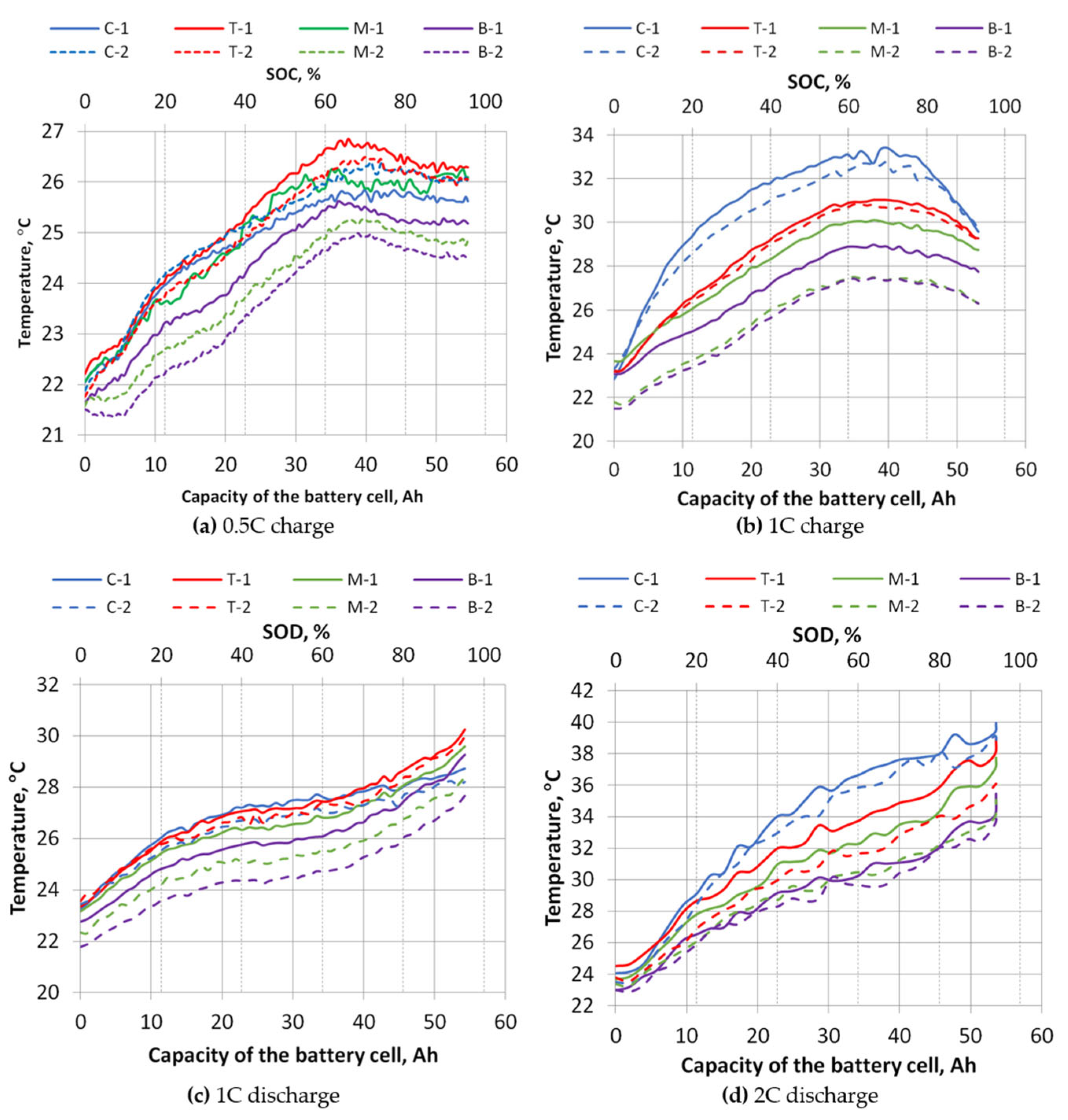

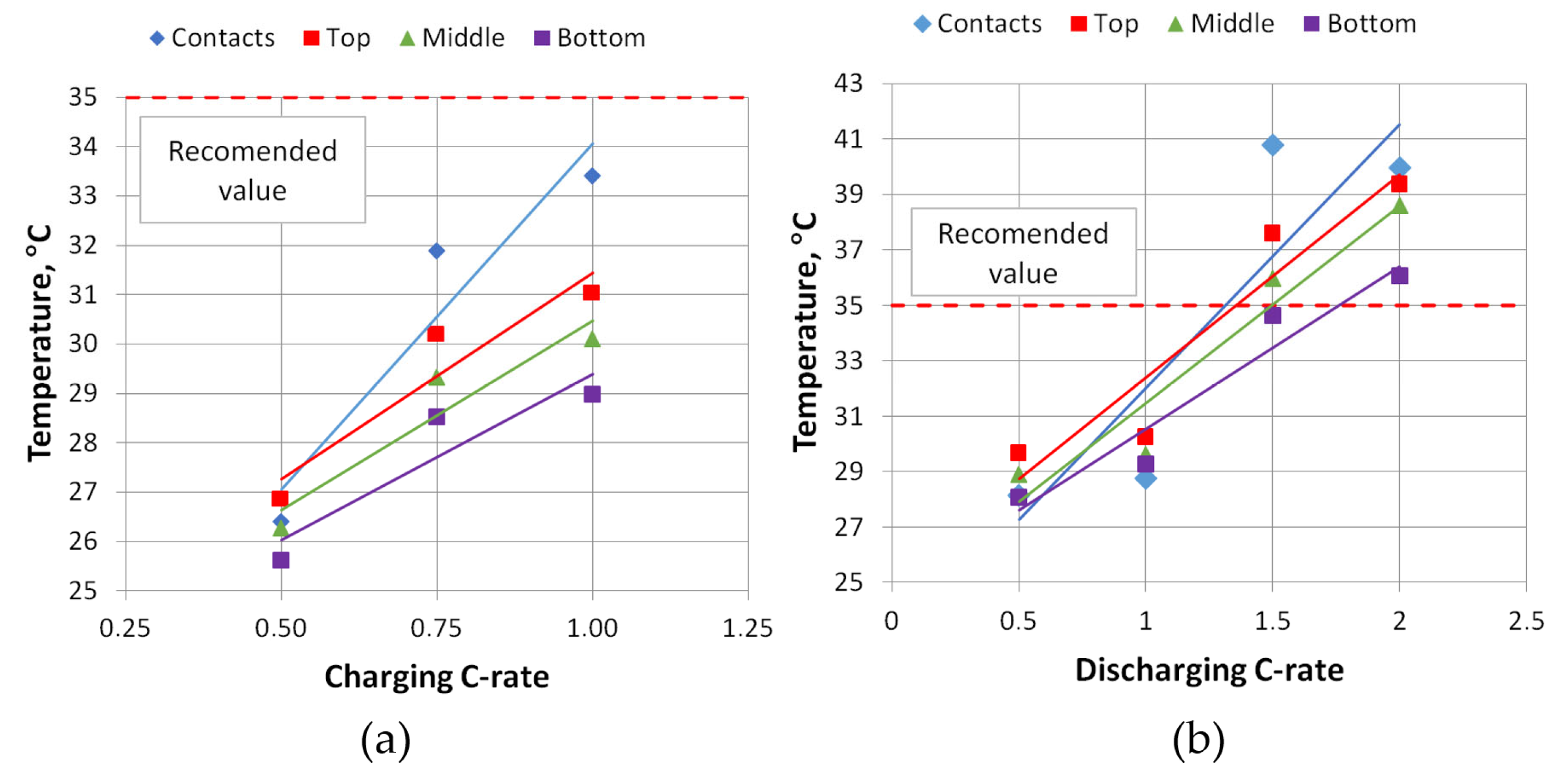

The plots of the measured temperatures were obtained from the temperature and heat flux sensors that are shown in

Figure 11, but not all measurements are shown here, only the charging at 0.5 C and 1 C, and the discharging process at 1 C and 2 C. The summarized dependencies of the maximum temperatures achieved for all measurements on the charging/discharging rates are given in

Figure 12.

As shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the temperature variation and the dependence on the charge/discharge rate show that the hottest part of the battery cell is the cell connection terminals. The temperatures measured on the cell terminals increase, especially with higher charging/discharging rates. When charging slowly (0.5 C), the contact temperatures are similar to, and even slightly lower than, the temperature measured at the top of the cell. From the temperature graphs in

Figure 8, during charging, the temperature of the battery cells rises only up to a point where the cell voltage reaches its maximum value of 4.2 V and the controller switches from constant current mode to constant voltage mode. When the switch to constant voltage mode is made, the charging current starts to decrease, thus reducing the load on the cell, and the temperature starts to decrease. During discharge, the current is almost constant throughout the discharge process. The discharge current decreases gradually as the discharge resistors become progressively hotter. Thus, the temperature rise is consistent, and the maximum temperature is reached at the end of the discharge process.

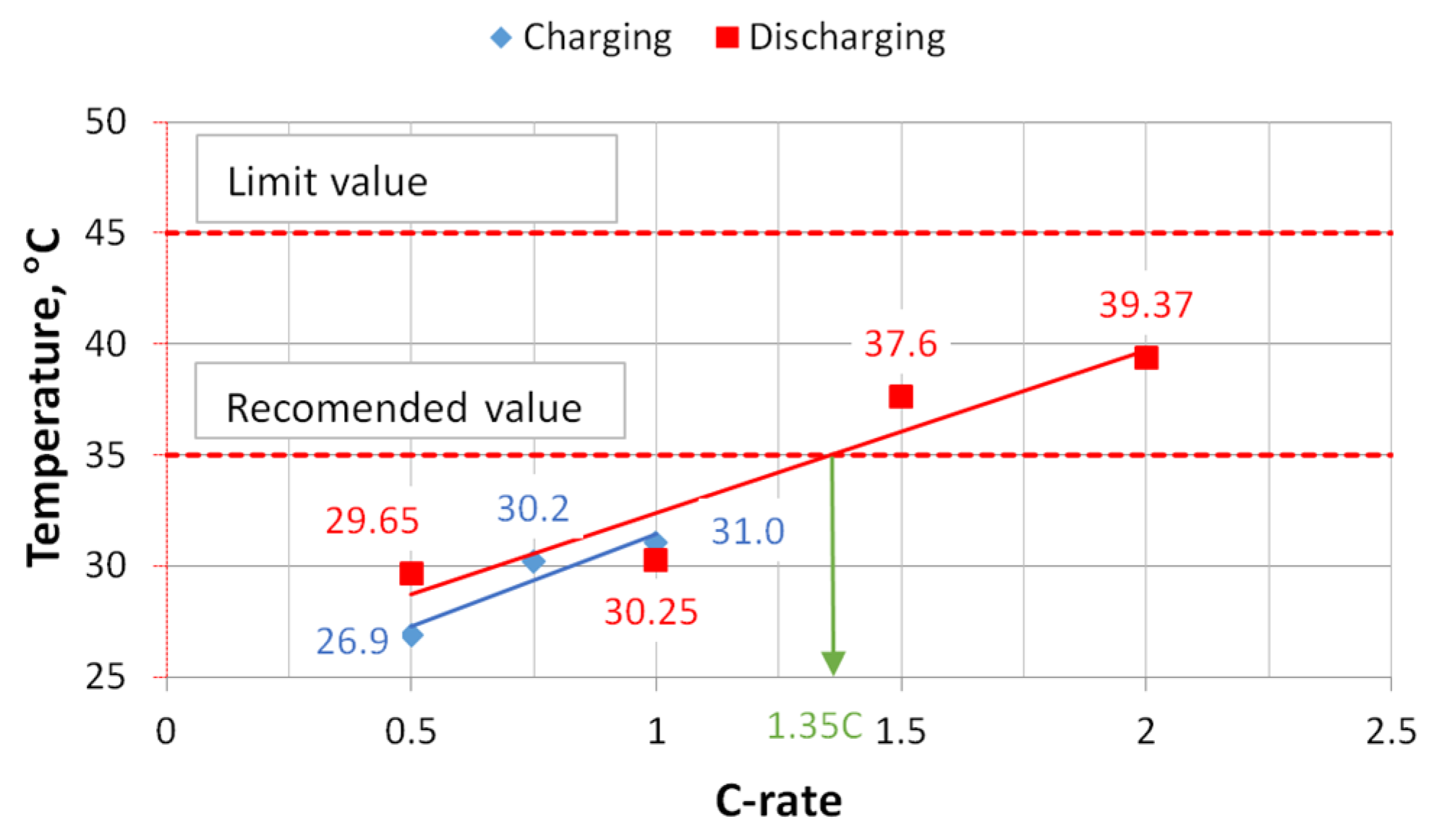

During the charging process at 1 C, the highest temperature reached was 31 °C, and during the discharge process at the same rate it was 30.3 °C. During discharging at 2 C, the temperature on the face of the cell reached 39.4 °C. This temperature on the face of the cell is too high, because at cell temperatures above 35 °C the degradation processes of the cell start to intensify, and thus the number of charge/discharge cycles of the cell start to decrease, which is declared by the manufacturer. As can be seen from the dependency graph, without the use of cooling and keeping the cell face temperature below 35 °C, the cells can only be discharged up to a rate of 1.35 C.

Figure 13 also shows that during the discharge process, the temperature of the face of the cell is slightly higher.

The data results in

Figure 14 show that the temperature gradient on the face of the cell also changes. The top of the cell is the warmest and the bottom of the cell is the coolest. As seen for both charging and discharging, the temperature gradient increases with a rise of the C-rate, but at 2 C the temperature gradient starts to drop. Due to a higher discharge rate, the cell heats rapidly and warms up more uniformly.

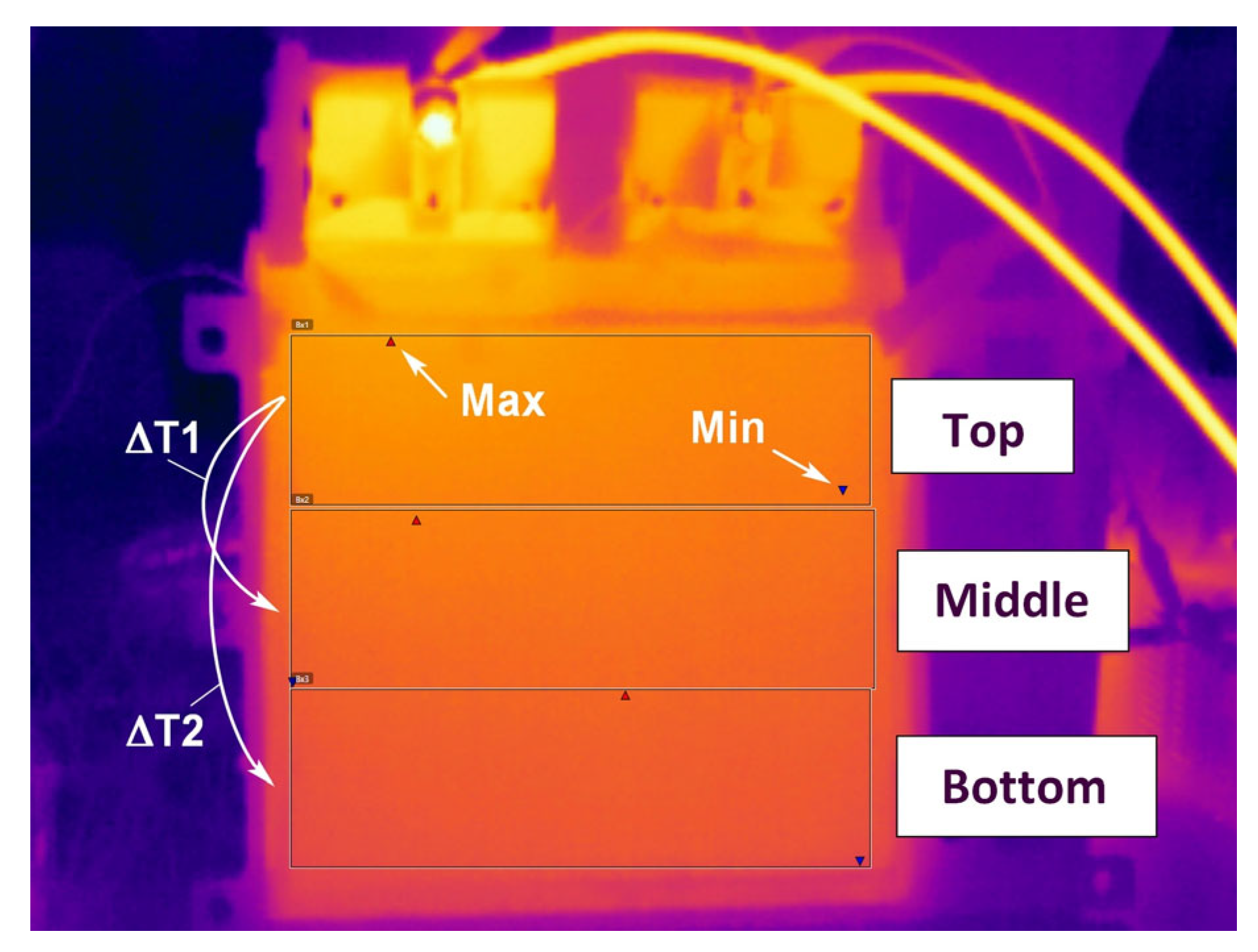

3.3. Results of Thermal Imaging Studies

While measuring the temperatures of the battery cells with heat flux and temperature sensors, thermal imaging measurements were also performed at the same time. The thermal images obtained were used to obtain a clearer picture of how the temperature is distributed on the face of the cell, how it changes during charging and discharging, and what temperature differences occur between the top and bottom of the cell. Knowing this information allows us to select the most suitable cooling method for pouch-type cells, the best configuration of cooling plate channels, and the best cooling fluid flow control.

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 show how temperature gradients vary with different charging and discharging C-rates. For the graphs in

Figure 15, average values were taken from the three measured zones shown in

Figure 4 and temperature differences were calculated (ΔT

1avg—the difference between the average temperature at the top of the cell and the average temperature in the middle of the cell, and ΔT

2avg—the difference between the average temperature at the top of the cell and the average temperature at the bottom of the cell). For the graphs in

Figure 16, the maximum temperatures at the top of the cells were taken and subtracted from the minimum temperatures at the middle and bottom of the cells, and the temperature differences were calculated (ΔT

1max-min—the difference between the maximum temperature at the top of the cell and the minimum temperature at the middle of the cell, and ΔT

2max-min—the difference between the maximum temperature at the top of the cell and the minimum temperature at the bottom of the cell).

These graphs show that the temperature differences during charging are greater than during discharging at the same charging/discharging rate. When charging the cell, the average temperature difference between the top and bottom ΔT

2avg at 1 C is 1.3 °C (maximum difference ΔT

2max-min is 3.4 °C), and when discharging, 0.9 °C (maximum difference ΔT

2max-min is 2.5 °C). During discharge, the maximum temperature differences ΔT

2 were recorded at a discharge rate of 1.5 C, which are greater than those measured at a discharge rate of 2 C, during which the highest temperatures were recorded. The average temperature difference between the top and bottom ΔT

2avg at a discharge rate of 1.5 C was 2.3 °C (maximum difference ΔT

2max-min is 4.6 °C), and at a discharge rate of 2 C, ΔT

2avg was 2.1 °C (maximum difference ΔT

2max-min is 3.9 °C). This reduction in ΔT at 2 C compared to 1.5 C can be explained by the non-uniform current density distribution in pouch cells: at lower C-rates, current density is concentrated near the tabs, leading to localized heating and pronounced gradients, while at higher C-rates the current spreads more evenly across the electrode area, generating heat more uniformly. As a result, rapid and spatially widespread internal heat generation overwhelms the thermal diffusion timescale, producing a more homogeneous temperature field despite higher absolute temperatures [

29,

30,

31]. Meanwhile, during slower discharge (e.g., 1.5 C), heat accumulates closer to the contacts, so the cell face temperature rises from the contact side, and the temperature gradient becomes more pronounced. Based on experimental studies with pouch-type lithium-ion cells, it is recommended that the temperature gradient of the cell face does not exceed 2–3 °C, to avoid uneven aging and electrochemical imbalance [

32]. Since this study was performed without active cooling, the observed larger temperature gradient (~4 °C) indicates the need to apply thermal management solutions that would ensure a more even temperature distribution and reduce the risk of degradation.

The thermal images of the cell face at 2 C discharge from the start of discharge to the end of discharge are shown in

Figure 17. During these tests, the highest temperatures were recorded on the face of the cell. The temperature change curves repeat the curves obtained from the temperature sensors (see

Figure 11d).

From the thermal images obtained, temperature contour maps (isotherms) were created, which clearly show the hottest area of the cell’s face and the temperature gradient, the graphs of which are presented in

Figure 18 and

Figure 19. The graphs were taken from the measurement points where the highest temperature gradients were obtained during charging and discharging (

Figure 18) and during discharging at different C-rates at maximum temperature (

Figure 19), which is typically the end of discharging.

It was found that when discharging at a rate of up to 1 C, the highest temperatures were recorded in the middle and top areas of the cell face, and as the discharge rate increased, the heating of the cell was most affected by the heating of the contacts. When charging only to a temperature of 0.5 C, the temperature rose in the middle part of the cell, and when charging faster, the highest temperatures were observed under the cell contacts.

Summarizing the results of temperature measurements, it was found that when the connecting cell contacts mechanically, good cell contact is very important. If the cell contacts are compressed even slightly less, the contacts and the cell itself immediately begin to heat up, and we had to repeat these tests because they distorted the overall results. It is obvious that when charging and discharging faster, the cell temperatures will be higher, and when charging/discharging above 1.5 C, it is necessary to apply an additional cooling method and first try to remove the temperature from the upper face of the cell.

The goal of further research is to create a battery module that would consist of 30 cells mechanically connected in series and cool their cell faces with cooling plates. During the research, fast charging up to 4 C will be used, and environmental operating conditions will be changed from −10 °C to 50 °C.

4. Conclusions

During the investigation of these pouch-type cells, a numerical model of the cell was created, and the results of numerical modeling were presented, which correlated with the experimental investigations performed. The average difference between simulation and experimental data was less than 5%, which indicates that the battery model created is sufficiently accurate and can be considered a reliable tool for engineering calculations. This cell model will continue to be used in the development of battery modules with different cooling methods.

After conducting experimental studies of pouch-type cells and measuring temperatures at different locations on the face of the cell under different charging and discharging modes, it was found that the cell heats up quite rapidly if no cooling is used. The approximate curves obtained show that at 1.35 C and higher C modes, the battery cell temperature exceeded 35 °C. Once this value is reached, the manufacturer declares that a more intense battery degradation process may begin and the number of charging and discharging cycles will decrease. While charging at a rate of 1 C, the maximum measured temperature on the face of the cell was at the top of the cell, above the contacts, and reached 31.0 °C. During discharge at 1.5 C, the maximum measured temperature was 37.6 °C, and at 2 C it was 39.4 °C.

It was also found that the face of the battery cell heated up unevenly—it depends on the C-rate. The top of the cell heated up the most, while the bottom heated up less. Additional thermal imaging studies were performed to determine the temperature gradients between the top and middle of the cell (ΔT1) and between the top and bottom of the cell (ΔT2), and graphs of their changes at different charging/discharging C-rates were presented. During charging at 1C, the average difference between the top and bottom was ΔT2avg = 1.3 °C, and the maximum difference was ΔT2max-min = 3.4 °C. During discharge at 1.5 C, the highest temperature gradients were obtained, with an average difference between the top and bottom of ΔT2avg = 2.3 °C, and a maximum difference of ΔT2max-min = 4.6 °C.