Abstract

Thick (900–1500 µm), crack-free lithium manganese oxide (LMO) electrodes with a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-based polymer electrolyte were prepared using an innovated slurry casting method. The selectivity and intercalation capacity of the thick electrodes of 900–1500 μm were evaluated in aqueous chloride solutions containing main cations in synthetic Salar de Atacama brine using cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements. The CV data indicated that a high Li+ selectivity of Li/Na = 152.7 could be achieved under potentiostatic conditions. With the thickest electrode, while the mass specific intercalation capacity was 6.234 mg per gram of LMO, the area specific capacity was increased by 3–11 folds compared to that for conventional thin electrodes to 0.282 mg per square centimeter. In addition, 82% of capacity was retained over 30 intercalation/dis-intercalation cycles. XRD and electrochemical analyses revealed that both Faradaic diffusion-controlled or battery-like intercalation and Faradaic non-diffusion controlled or pseudocapacitive intercalation contributed to the capacity and selectivity. This work demonstrates a practical technology for thick electrode fabrication that promises to result in a significant reduction in manufacturing and operational costs for lithium extraction from brines.

1. Introduction

The demand for and production of lithium-ion batteries have been increasing exponentially in recent years, largely due to the expansion of global electric car sales [1]. In 2023, global demand for lithium was estimated at 989,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE), while production was around 964,000 metric tons of LCE, resulting in a 3% shortfall [2]. By 2028, global lithium demand is expected to double, surpassing two million metric tons of LCE, compared to the 2023 level.

The global distribution of lithium resources is highly uneven. Lithium-bearing minerals, including spodumene, lepidolite, and petalite, are primarily found in pegmatite formations [3]. These hard-rock deposits are mostly concentrated in Australia, the world’s largest lithium producer, as well as in Canada, China, and parts of Africa [4]. Lithium-containing brine from salt lakes and geothermal wells accounts for around 60% of total lithium reserves [5]. The ‘Lithium Triangle,’ which is formed by Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, holds the most significant global lithium reserves [6]. Lithium concentration often varies widely among different salt lakes and geothermal wells, as well as within different regions of the same lakebed [7]. For instance, Chile’s Salar de Atacama is known for its exceptionally high lithium concentration, averaging 1500 mg/L, though concentrations can fluctuate dramatically within different parts of the lakebed, ranging from 900 mg/L (0.13 M) to 8500 mg/L (1.2 M) [8]. This variability underscores the need for research and development of lithium extraction methods that can provide high selectivity, efficiency, and cyclability across a wide range of concentrations.

Direct extraction of lithium compounds from brines accounts for a significant portion of the industrial lithium supply. The conventional evaporation/precipitation process typically involves purification, evaporation, and chemical conversion [9,10]. It has been widely used in large-scale production for decades due to its low energy consumption. However, major drawbacks include large-scale environmental contamination, high freshwater and chemical consumption, and long production times.

Membrane separation technology offers an alternative to conventional methods due to its simplicity, low energy cost, and eco-friendliness. Among membrane-based approaches, nanofiltration (NF) membranes have gained attention for their ability to achieve preferential Li+ separation through steric hindrance and Donnan exclusion mechanisms [11,12,13]. Wang et al. [14] developed a copper-doped m-phenylenediamine NF membrane, which demonstrated both high water permeability and Li/Mg selectivity. To further improve selectivity, the NF membrane was incorporated with metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) featuring tailored pore sizes and functional groups [15,16]. NF membranes have also been integrated into electrodialysis systems to separate monovalent ions [17,18]. However, fouling issues and trade-offs between permeability and selectivity remain barriers to their widespread application [19]. Ion-sieve membranes, which utilize intercalation-based adsorption, demonstrate excellent selectivity and high adsorption capacities [20,21,22]. Their chemical stability and adsorption efficiency make them promising for high-salinity environments, though inorganic particle leakage poses significant challenges. In industrial applications, EnergyX commissioned its LiTAS pilot plant at Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni in 2021, utilizing membrane separation technologies for lithium extraction [23].

Ion-sieve oxides, acting as adsorbents, are derived from precursors that contain the target metal ions [24]. The molecular structure of the precursors can be retained even after the target ions are stripped. Lithium manganese oxide (LMO)-based lithium-ion sieves (LISs) have gained significant attention due to their high lithium uptake capacities [25,26]. In the spinel structure of LMO, Li+ ions transport through channels that connect octahedral sites (8a), tetrahedral sites (16d), and octahedral sites (8a). Lithium extraction is achieved by converting [LIS(H)] to [LIS(Li)] via Li-H ion exchange. However, the de-intercalation step requires a large amount of acid, which leads to degradation of the ion-sieve oxide. Moreover, acid recovery is a time-, freshwater-, and energy-consuming process. The ion-sieve process has already been implemented at the pilot scale by Lilac Solutions, a company actively involved in several lithium extraction projects worldwide, including the Great Salt Lake project in Utah, the Kachi project in Argentina, and the Atacama field pilot project in Chile [27,28].

Electrochemical lithium adsorption processes have been investigated for several decades. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) has attracted significant attention due to its stability, reversibility, durability, and eco-friendliness [29]. Liu et al. [30] developed an “ionic pumping” system with a TiO2-coated FePO4 electrode for lithium extraction. The TiO2 coating enhances the contact between the electrode and seawater without compromising the electrode’s conductivity. Trócoli et al. [31] used de-intercalated FePO4 as an intercalation electrode, with the counter electrode based on K2NiFe(CN)6. The Prussian blue analogue electrode is Li-exclusive, and with these electrodes, brine water can be used as the recovery solution. LMO is an excellent intercalation electrode material for lithium extraction, as the ionic radius of the lithium ion fits well into the LMO spinel structure. Lee et al. [32] developed a λ-MnO2|Ag system that was highly selective for lithium ions. Adsorption/desorption can be achieved by reversing the voltage sign. Mu et al. [33] proposed a ‘rocking chair’ λ-MnO2|LiMn2O4 system equipped with an anion exchange membrane. Under an applied voltage, the LiMn2O4 electrode releases Li+ into the recovery solution, while the λ-MnO2 electrode simultaneously captures Li+ from the brine.

To reduce the cost of electrode materials, researchers have developed a variety of alternatives to silver counter electrodes. Kim et al. [34] introduced an LMO|Zn system characterized by low cost and high capacity. Missoni et al. [35] developed a counter electrode made of polypyrrole (PPy), which demonstrated significant advantages in reducing the energy consumption of lithium extraction. Zhao et al. [36] advanced the design by utilizing LMO|MXene electrodes combined with a pulsed electric field to enhance the lithium extraction process. The pulsed electric field effectively eliminated concentration overpotential, thereby promoting lithium intercalation. Zhao et al. [37] also utilized polyaniline nanowires as the active material to fabricate high-capacity counter electrodes.

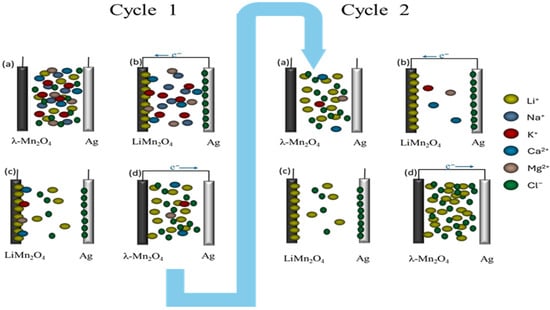

In electrochemical extraction, a two-stage process is implemented, as illustrated in Figure 1. In the first stage, a source solution containing lithium ions is pumped into the cell, and a negative voltage sweep is applied, enabling the intercalation of lithium ions into the λ-MnO2 electrode. In the second stage, the cell is purged with deionized water to remove any residues. Subsequently, a diluted recovery solution containing LiCl is introduced into the cell, and a positive voltage sweep is applied, releasing the captured lithium ions into the recovery solution. Typically, several cycles of repeating the first and second stages are executed to increase the purity of lithium chloride. The recovered solution from the prior cycle is then used as the input for the first stage of the following cycle. For battery manufacturers, a purity of 99.5% or higher is preferred.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of lithium extraction procedure. Cycle 1: (a) A source solution is pumped into the cell; (b) a negative voltage is applied between the λ-MnO2 and Ag electrodes; (c) after purging with pure water, a recovery solution is introduced into the cell; and (d) a positive voltage is applied between the λ-MnO2 and Ag electrodes. Cycle 2: (a) the solution with recovered lithium ions is pumped into the cell; (b) a negative voltage is applied between the λ-MnO2 and Ag electrodes; (c) after purging with pure water, a recovery solution is introduced into the cell; and (d) a positive voltage is applied between the λ-MnO2 and Ag electrodes.

For the commercialization of electrochemical extraction technology, materials, fabrication, and operational costs are major barriers and concerns. By comparison, the costs of active electrode materials are much lower than the combined costs of corrosion-resistant current collectors, membranes/separators, bipolar plates, pumps, tubes, and valves. Therefore, the total cost per unit of product could be reduced by increasing the loading of active materials per unit area of the electrode or by increasing the thickness of the active material layer of the electrode. Although maximizing lithium absorption/intercalation capacity per unit area by increasing electrode thickness could be highly beneficial, it has not received sufficient attention in the literature. In fact, the fabrication of crack-free thick electrodes presents notable technical challenges. To date, intercalation electrodes thicker than 200 µm have rarely been reported. Conventional tape-casting or slurry-casting methods often encounter a limit on electrode thickness due to the initiation of macroscopic surface cracks during the post-casting drying process [38,39,40]. These cracks are believed to primarily result from capillary stresses generated during the non-uniform drying process [41]. Cracked active electrodes are prone to falling off or falling apart, making them unsuitable for electrochemical cell fabrication. The presence of these cracks reduces the in-plane conductivity of the electrode, induces heterogeneity in current and potential distribution, and causes uneven flow of liquid reactants. This leads to reduced absorption capacity, ion uptake efficiency, energy efficiency, and durability [42]. In this study, we developed a method for fabricating thick, crack-free, porous Li-selective LMO-based polymer electrolyte-containing electrodes with thicknesses up to 1500 µm. The electrochemical cells fabricated with thick electrodes demonstrated high selectivity, capacity, and stability when tested in synthetic brine containing lithium ions and multiple co-existing metal ions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Li-Selective Electrode Fabrication

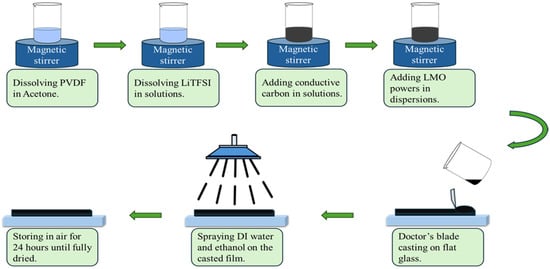

As shown in Figure 2, 50 mg of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, 99.5%, MTI Corporation, Richmond, CA, USA) powder was dissolved in 20 mL of acetone (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) by stirring at 80 °C until the mixture became clear. Then, 0.3 g of lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI, 99.95%, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was added and stirred for 30 min. This polymer electrolyte was incorporated into the electrodes as the ionic conducting binder. Next, 0.3 g of conductive carbon powder (99.5%, MTI Corporation, Richmond, CA, USA) was added to the solution, followed by stirring for an additional 15 min. Subsequently, 0.8 g of LiMn2O4 (LMO, 99.7%, MTI Corporation, Richmond, CA, USA) powder was added to the suspension and stirred continuously for 2 h. The resulting slurry was then cast onto a piece of carbon cloth (300 μm, Fuel Cell Store, Bryan, TX, USA) using a doctor’s blade to ensure uniform thickness. During the post-casting process, a mixture of deionized water and ethanol (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in a 1:1 volume ratio was sprayed onto the cast film for 40 min to maintain an environment with high humidity and ethanol vapor. The cast film dried slowly under this environment. The film was subsequently left to dry in air, without solution spraying, for 24 h. By adopting this protocol, the slurry film dried without forming visible cracks, even at a thickness of 1500 μm. The PVDF component may undergo a non-solvent-induced phase separation (NIPS) process [43], which occurs when acetone is exchanged with water, leading to the formation of a porous structure. Both the carbon cloth substrate and the water/ethanol spray played crucial roles in maintaining the cast film crack-free during drying.

Figure 2.

Thick Li-selective electrode fabrication process.

2.2. Physical Characterization

The surface morphology of the electrodes was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss EVO 60, Oberkochen, Germany). The crystal structures of the cathode materials that underwent lithiation/delithiation were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Philips X’PERT, Cambridge, MA, USA). XRD measurements were performed using a Cu Kα1 radiation source (λ = 1.54056 Å) at an operating voltage of 45 kV and a current of 20 mA.

2.3. Electrochemical Characterization

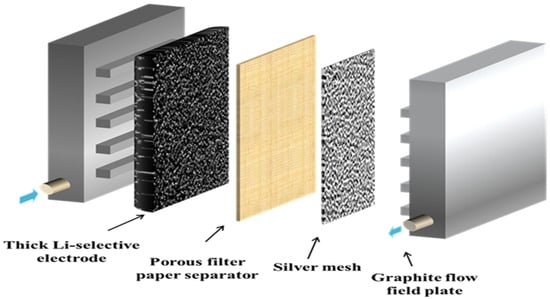

Electrochemical measurements in this study were performed using a fuel cell setup (Fuel Cell Store, Bryan, TX, USA), where the porous Li-selective electrode functioned as the intercalation electrode, and a piece of silver mesh, cut to match the size of the Li-selective electrode, served as the counter electrode. A filter film (PTFE, 0.2 μm, Advantec, Dublin, CA, USA) was used as the porous separator. The structure of the cell is shown in Figure 3. To enhance selectivity for lithium ions, the LiMn2O4 electrode was electrochemically converted to a λ-MnO2 electrode prior to electrochemical measurements. This conversion was achieved by applying a potential of 1.0 V (versus a saturated silver-silver chloride electrode, or SSC) for 30 min in a 0.1 M KCl solution. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were conducted on the λ-MnO2|Ag cell using a potentiostat/galvanostat (Gamry 3000, Gamry Instruments, Warminster, PA, USA) to evaluate the selectivity, capacity, and cyclability of the lithium extraction system.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the electrochemical cell.

Three types of representative solutions were used to evaluate the selectivity and adsorption capacity of the electrodes: (1) 0.1 M LiCl, NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, or MgCl2; (2) 1 M LiCl, NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, or MgCl2; and (3) synthetic brine. The synthetic brine used was a solution mimicking the composition of brine from the Salar de Atacama in Chile [32]. The specific concentrations are presented in Table 1. Because the concentration of lithium ions in the Salar de Atacama ranged from 0.13 to 1.2 M, 0.1 M and 1 M LiCl solutions were chosen as the test solutions.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of ‘Salar de Atacama’ brine lake, Chile [32].

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Cast Film

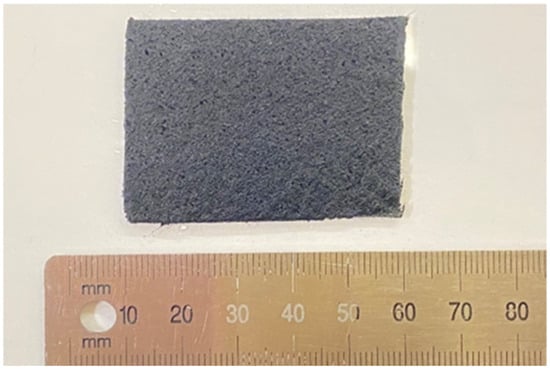

A photo of the as-prepared Li-selective electrode, fabricated using the procedure outlined in Figure 2, is shown in Figure 4. The photo reveals some unevenness, but no visible cracks. To investigate the effects of mass loading and electrode thickness on the electrochemical lithium adsorption process, electrodes with thicknesses of 400, 900, 1200, and 1500 µm were prepared.

Figure 4.

Photo of Li-selective electrode with thickness of 1500 µm including the carbon cloth.

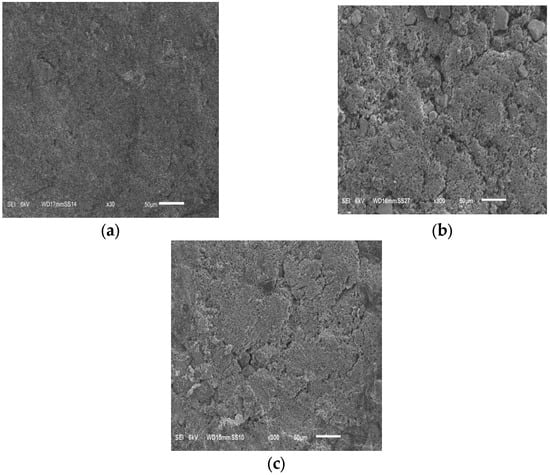

SEM micrographs of LMO electrodes after adsorption tests are shown in Figure 5. Electrodes with higher mass loading were smooth and exhibited uniform thicknesses on the carbon cloth and ideal for electrochemical testing. The absence of visible cracks demonstrates the effectiveness of the adopted electrode fabrication method/procedure.

Figure 5.

SEM images of LMO electrodes with a thickness of (a) 900 µm, (b) 1200 µm and (c) 1500 µm.

One Li-selective electrode was lithiated at 0.5 V for one hour, and another was delithiated at 1 V for one hour in 0.1 M LiCl solutions. The active materials were then scraped off the electrodes using a blade, thoroughly rinsed with deionized water, and dried in a cabinet oven at 80 °C for 4 h. The resulting lithiated and delithiated powders were analyzed separately using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

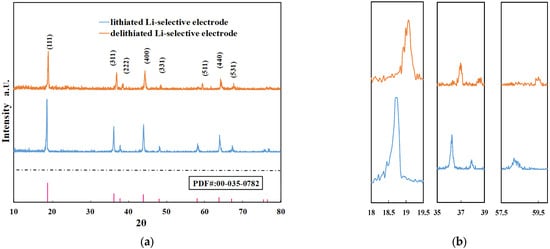

Due to the substantially higher X-ray scattering factors of manganese and oxygen compared to lithium, the XRD pattern of LMO was primarily dominated by contributions from manganese and oxygen atoms [44]. As shown in Figure 6a, the XRD patterns of the lithiated and delithiated electrodes are similar in terms of relative peak positions and intensities. However, noticeable peak shifts are observed when comparing the diffraction spectra, as illustrated in Figure 6b. It has been reported that during the delithiation process, the release of Li+ ions leads to a reduction in the lattice constant, a. According to Bragg’s law, the diffraction angle will shift to higher values as a result. A summary of the lattice parameters for both the lithiated and delithiated states is provided in Table 2.

Figure 6.

(a) XRD pattern of lithiated and delithiated Li-selective electrodes and (b) enlarged parts of the XRD patterns. Peaks from left to right are, (111), (311), (222), and (511).

Table 2.

Lattice parameters in lithiated and delithiated states of LMO.

3.2. Electrochemical Measurements in 1 M Chloride Solution

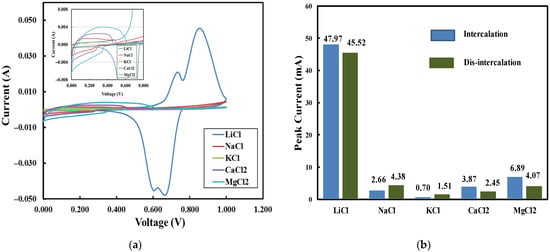

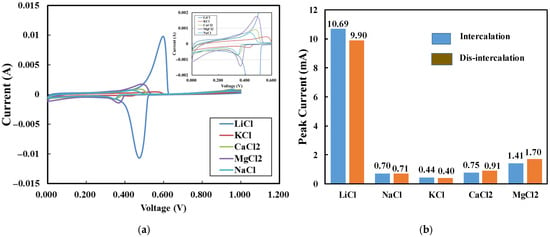

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were conducted to evaluate the adsorption capacity and relative selectivity of the LMO electrodes. Figure 7a displays a set of CV curves generated in 1 M chloride solutions. The results indicate that the Li-selective electrode exhibits a high adsorption capacity for lithium ions in LiCl solution, superior to its performance for sodium ions in NaCl, potassium ions in KCl, calcium ions in CaCl2, and magnesium ions in MgCl2. The corresponding peak currents are summarized in Figure 7b. The maximum adsorption peak current for LiCl is 48 mA at 0.66 V, which is much higher than those for other cations.

Figure 7.

(a) CV curves of 1 M chloride solutions (scan rate: 2 mV/s; electrode thickness: 1500 µm); (b) adsorption peak currents of 1 M chloride solutions.

3.3. Electrochemical Measurements in 0.1 M Chloride Solution

We also evaluated the adsorption and selectivity in 0.1 M aqueous solutions of various metal chlorides, including KCl, NaCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, and LiCl, as shown in Figure 8a. This concentration of lithium ions (0.1 M) falls within the typical ranges found in actual brine [8]. The CV curves again confirmed a much higher adsorption capacity for Li+ compared to other ions in low-concentration solutions. By comparing Figure 7b with Figure 8b, it is evident that the relative adsorption capacity of the electrode for lithium ions, compared to other ions, or its selectivity for lithium ions, was maintained at high levels. To quantify the selectivity, the capacity at peak current, or peak capacity, was evaluated by calculating the average area below (disintercalation) and above (intercalation) the peaks. Specifically, the peak capacity ratio of Li/Mg was 8.33 for 1 M solutions and 7.39 for 0.1 M solutions. This is significant since lithium extraction from high Mg/Li brine remains a key technical challenge in global lithium recovery efforts [45,46].

Figure 8.

(a) CV curves of 0.1 M chloride solutions (scan rate: 2 mV/s; electrode thickness: 1500 µm), (b) adsorption peak current of 0.1 M chloride solutions.

3.4. Cyclability Test

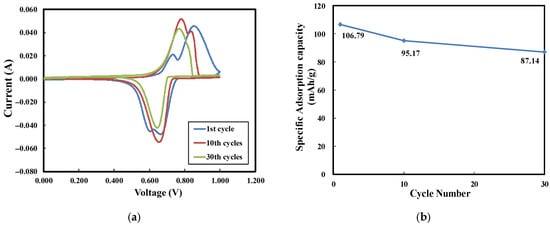

To examine the cyclability of the electrode, the cell was tested for up to 30 cycles, as shown in Figure 9a. The electrochemical charge capacities were calculated and are shown in Figure 9b. Despite the increasing number of cycles, the peak current values remained relatively stable. The specific adsorption capacity decreased from 106.79 mAh/g to 87.14 mAh/g over the 30-cycle test, suggesting that the electrode exhibited good cyclability.

Figure 9.

(a) Cyclability test of LMO electrodes in 1 M LiCl (scan rate: 2 mV/s; electrode thickness: 1500 µm), (b) specific adsorption capacity with various cycles.

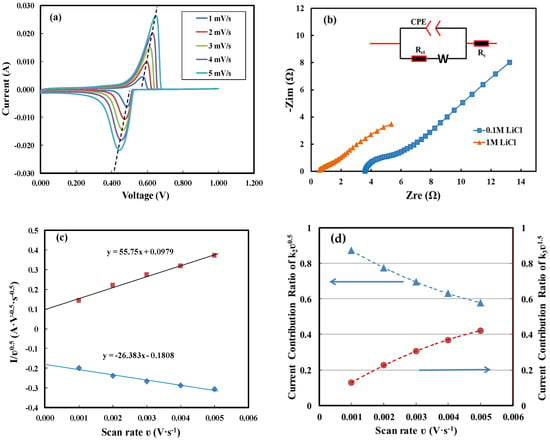

3.5. The Effect of Scan Rates

As the scan rate increased, a shift in peak potential was observed, as shown in Figure 10a. The reduction peak currents and corresponding potentials are summarized in Table 3. By connecting the peak current points, the reverse slope was calculated to be 2.8 Ω. In Figure 10b, Nyquist plots for 0.1 M and 1 M LiCl were curve-fitted to an equivalent circuit model. The model consisted of an equivalent series resistance (ESR, Rs), a constant phase element (CPE) in parallel with a charge transfer resistance (Rc) and a Warburg impedance element. The curve-fitting yielded an ESR of 3.55 Ω and a charge transfer resistance of 5.56 Ω for 0.1 M LiCl, and an ESR of 0.54 Ω and a charge transfer resistance of 1.53 Ω for 1 M LiCl. In the concentration range of 0.1 to 1 M, the ionic conductivity of the LiCl solution increases with concentration, thereby significantly reducing the ESR. Increasing the concentration of Li+ also enhances the intercalation reaction rate and reduces the charge transfer resistance. The ESR for 0.1 M LiCl was close to the resistance value obtained by the reverse slope of the line connecting the peak current points. This resistance value characterizes the contribution of IR drop to the applied voltage during a CV test and is commonly referred to as the internal resistance of the electrochemical cell.

Figure 10.

(a) CV test of LMO electrodes in 0.1 M LiCl with various scan rates (electrode thickness: 1500 µm), (b) Nyquist plot with the frequency from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz, (c) plot of I/ʋ0.5 vs. ʋ0.5 for intercalation process, (d) The current contribution ratio of k2ʋ0.5 and k3ʋ1.5 as a function of the scanning rate.

Table 3.

Peak current and corresponding potential with various scan rates.

Peak current as a function of scan rate has been used by Aldama et al. [47], Forghani et al. [48], and Zhou et al. [49] to define the battery-like and capacitive contributions by utilizing different current-time scaling laws of the two charge/discharge mechanisms. The capacitive contribution is described by while the Faraday or redox contribution is described by , where is scan rate in V/s and and are constants. However, according to Ghasemiahangarani et al. [50], the peak current can be related to the scan rate by the equation below:

where is the scan rate, and , , and are proportionality constants related to surface capacitance-controlled (capacitive contribution), Faradaic diffusion-controlled (Cottrell/battery-like contribution), and Faradaic non-diffusion-controlled kinetics, respectively. The third term represents the characteristics of a pseudocapacitive contribution that originates from nano-sized surface structures, porosity, and local intercalation paths. In other words, there is a region dominated by migration rather than diffusion.

Unlike previous studies [33,48,49] that employed nanostructured materials with specific surface areas of several hundred or even thousand m2/g, this work used a mixture of conductive carbon and LMO powder. According to the manufacturer’s specification for the LMO powder, the average particle size was 20 μm, and the compaction density was 2.85 g/cm3. Based on these parameters, the specific surface area of LMO was 0.1 m2/g, while the specific surface area of the conductive carbon was 62 m2/g. Therefore, the average specific surface area of the mixture was 17 m2/g.

According to results for supercapacitors based on activated carbon with specific surface areas of 1500–2000 m2/g [49], electrode materials with a surface area of 17 m2/g would result in a capacitive current of 0.005 mA, which is negligible, compared to the peak current of 6.3 mA. Thus, the first term in Equation (1) is negligible, and Equation (1) can be rearranged as:

In Figure 10c, is plotted against . For the intercalation current, the proportionality constant values of and are 0.1808 AV−0.5s−0.5 and 26.383 AV−1.5s−1.5, respectively. The fitting curve does not pass through the origin, indicating that both Faradaic diffusion-controlled (battery-like) and Faradaic non-diffusion-controlled (pseudocapacitive) contributions are involved in the intercalation process. In Figure 10d, the current contribution ratios of and to the total current are plotted as a function of scan rate. As the scan rate increased, the ratio of decreased from 87.3% to 57.8%, revealing the limitation of diffusion-dominated mass transport. This result indicates that porosity and tortuosity may impact the electrochemical reaction kinetics. However, to the author’s knowledge, there has been no systematic research on the effect of porosity in similar electrochemical systems.

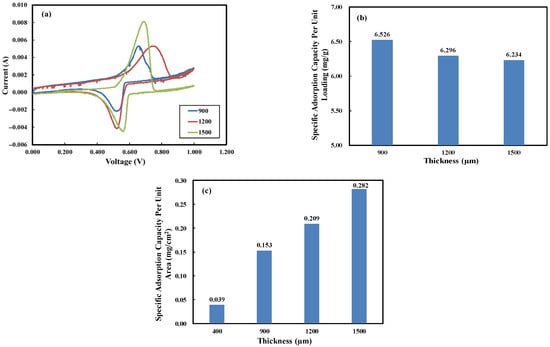

3.6. The Effect of Electrode Thickness

To explore the impact of electrode thickness on the lithium recovery process, synthetic brine (Salar de Atacama, Chile) was used [32]. The composition of the synthetic brine is listed in Table 1. The electrodes were fabricated with different thicknesses (900, 1200, and 1500 µm). The cyclic voltammetry (CV) results are displayed in Figure 11a. The specific adsorption capacities per unit loading show a slight decrease with increasing electrode thickness, with values of 6.562, 6.296, and 6.234 mg/g for electrodes with thicknesses of 900, 1200, and 1500 µm, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 11b. Figure 11c shows a significant increase in the specific adsorption capacity per unit area as the electrode thickness increases. For comparison with literature data, we also fabricated a Li-selective electrode with a total thickness of 400 µm, consisting of a 300 µm carbon cloth substrate and a 100 µm active material layer, which represents a typical electrode thickness reported in the literature. The specific adsorption capacity per unit area was evaluated at 0.039 mg/cm2.

Figure 11.

(a) CV of the LMO electrode in the synthetic solution with the concentrations given in Table 1 (scan rate: 2 mV/s, electrode thickness: 900, 1200, 1500 µm), (b) specific adsorption capacity per unit loading, (c) specific adsorption capacity per unit area.

4. Discussion

From Figure 7a, the CV curve for 1 M LiCl shows two distinct pairs of current peaks, which correspond to the two-step intercalation process of lithium ions into the electrode material. These reactions can be described as follows [51]:

In Figure 8a, the integration of the CV curve obtained in 0.1 M LiCl solution yielded an estimated lithium adsorption capacity of 11.826 mg/g for the Li-selective electrode. Based on the XRD analysis in Figure 6, the lattice parameter of LMO changed from 8.20495 Å (lithiated) to 8.05145 Å (delithiated). According to Chladil’s [52] method, the corresponding lithium concentration, x, in LixMn2O4 during the lithiation/delithiation process fell within the range of 0.3 ≤ x ≤ 0.9. Based on this result, the adsorption capacity was 13.649 mg/g, which was consistent with the value directly obtained by integrating the CVs.

While the maximum theoretical adsorption capacity for the LMO-based electrode prepared in this study was 38.4 mg/g (for x = 1), the reported values of adsorption capacity in the literature typically ranged from 2 to 25 mg/g [53,54]. In Figure 11b, the adsorption capacity in the synthetic brine with multiple metal ions for the 1500 μm electrode was 6.234 mg/g, smaller than 11.826 mg/g obtained in the 0.1 M LiCl solution. This decrease was mainly due to the competitive adsorption of coexisting ions on the electrode surfaces, resulting in significant steric hindrance to lithium intercalation kinetics [55,56,57].

From Figure 7a and Figure 8a, the peak capacity values for K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ at the peak voltage for Li+ were determined. These values are given in Table 4, along with the peak capacity for Li+. For 0.1 M solutions, the peak capacity for LiCl is over 20 times higher than that for 0.1 M NaCl, or 32 times higher than that for 1.0 M NaCl, revealing a significant selectivity difference.

Table 4.

Peak capacity values for 1 M LiCl, KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, and NaCl solutions and for 0.1 M LiCl, KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, and NaCl solutions.

Methods for practical electrochemical adsorption of lithium have been proposed and assessed in laboratories [54]. The two most commonly discussed methods are the constant current (galvanostatic) method [30,54,58,59] and the constant voltage (potentiostatic) method [54,60]. In a galvanostatic process, the cell voltage decreases continuously from a high to a low voltage (typically by 1.3 V), whereas in a constant voltage process, the current decreases continuously from a high current and gradually approaches zero.

In the galvanostatic method, the selectivity of Li to Na can be estimated using the ratio of the peak capacities. For high concentration, the ratio is 6.299/0.191 = 32.97, and for low concentration, the ratio is 0.329/0.015 = 21.93. However, when the constant voltage method is used, the selectivity of Li to Na is estimated using the ratio of the peak capacity of LiCl to the capacity of NaCl at the peak voltage. For example, the ratio is 0.329/0.0021 = 156.7. Thus, to achieve greater selectivity, the constant voltage method is preferred over the galvanostatic method.

Calvo et al. [54] evaluated the selectivity of Li to Na in a simulated brine. The initial [Li+]/[Na+] ratio was 0.01. After the first cycle of the lithium extraction process, as described in Figure 1, the ratio increased to 1.59. This selectivity of 159 is consistent with the selectivity estimated at the peak current voltage in a constant voltage process.

The high selectivity of lithium ions can be attributed to their small ionic radii, which allow them to fit precisely into the tetrahedral sites of the three-dimensional spinel structure of λ-MnO2 [32]. The ionic radii of relevant cations are summarized in Table 5. As lithium ions are removed from the LMO lattice during de-intercalation, the resulting vacancies in λ-MnO2 create well-defined structural templates that selectively accommodate Li+ during re-intercalation. This “template effect” underpins the intercalation capacity of λ-MnO2, enabling high selectivity for Li+ while excluding larger cations such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ [61].

Table 5.

Ionic radii of cations in this study.

However, the case for Mg2+ is different. Although Mg2+ has an ionic radius comparable to that of Li+, its high dehydration energy presents a kinetic barrier, effectively hindering its intercalation into the λ-MnO2 framework [62].

A shift in the peak potential towards more negative values was observed in Figure 9a, suggesting that not all the absorbed lithium ions are released back into the recovery solution. This behavior can be explained by the Nernst equation.

The Li+ intercalation reaction in LMO is:

Thus, the Nernst equation can be rewritten as [33]:

where is the standard equilibrium potential of electrode reaction, is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1), is the temperature, is the Faraday’s constant (96,485 C/mol), is the residual intercalation percentage of Li+, and is the activity of Li+ in water. The accumulation of residual Li+ leads to an increase in value, resulting in a negative shift in the equilibrium potential. Additionally, capacity fading may arise from microstructural changes within the electrode pores, as well as from detachment of active particles from the conductive carbon-based binder [63,64]. Moreover, manganese dissolution—recognized as a critical degradation mechanism in LiMn2O4 spinel materials—proceeds through a disproportionation reaction (2 Mn3+ → Mn2+ + Mn4+) [65]. Several mitigation strategies have been proposed. For instance, the addition of Nafion has been shown to suppress both the disproportionation reaction and the resulting Mn dissolution, as its sulfonic acid groups preferentially capture Mn2+ over other cations [66]. Jiang et al. [67] fabricated an LMO electrode supported by a carbon nanotube sponge, whose abundant microstructure provides increased active sites. The formation of Mn–O–C bonds further enhances the structural robustness. Furthermore, Gou et al. [68] demonstrated that doping with Bi3+ effectively suppresses the Jahn–Teller effect. This incorporation compresses the Mn–O octahedra while expanding the Li–O tetrahedra, a structural adjustment that strengthens the framework and improves the electrode’s cycle life.

From the CV curves for lithium adsorption shown in Figure 7a and Figure 8a, a shift in the peak potential for lithium adsorption toward more negative values is observed in 0.1 M LiCl solution compared to that in 1 M LiCl. Specifically, the peak potential in 0.1 M LiCl is approximately 0.48 V, while in 1 M LiCl, the peak potential increases to around 0.66 V. This shift exceeds the expected Nernstian response of 0.059 V per decade [69,70]. The deviation is attributed to differences in internal resistance, which arise from the reduction in bulk ion concentrations [71]. Furthermore, during the intercalation process, lithium ions are depleted near the electrode surface, leading to a local concentration lower than that in the bulk solution. This concentration gradient also contributes to the deviation from the Nernstian prediction.

While the capacitive contribution to current arises from the formation of electric double layers (EDLs) at the electrolyte/electrode interface, without electric charge passing across the interface, both Faradaic diffusion-controlled and Faradaic non-diffusion-controlled (pseudocapacitive) contributions involve electric charge transfer across the interface. The Faradaic diffusion-controlled contribution is characterized by a conventional charge transfer process across an interface with regular geometry, whereas the pseudocapacitive contribution involves charge transfer at an irregular interface with nano-sized roughness, micro-porous channels, tortuous intercalation paths, and semi-structured cation-anion clusters. According to Ghasemiahangarani et al. [50], in non-diffusion-controlled cases, mass transfer is dominated by migration rather than diffusion. This model provides insight into the fact that pseudocapacitive behavior originates from surface reactions.

It is not surprising that pseudocapacitive behavior arises from surface reactions, as it is observed in systems with irregular or high-surface-area interfaces, where migration dominates mass transfer. In such systems, the reaction time scaling is proportional to or , rather than . In the present study, both the CV and XRD measurements confirm similar intercalation levels, indicating that both pseudocapacitive and Faradaic diffusion-controlled (battery-like) currents are Faradaic in nature.

From Figure 10d, the obtained values of and can be used to calculate the Faradaic diffusion-controlled and pseudocapacitive contributions, respectively. The ratio of the Faradaic diffusion-controlled current to the total current is highest at the lowest scan rate and decreases as the scan rate increases. This trend is primarily due to the sluggish kinetics of electrochemical reactions and limited ion mass transport through the electrode [48]. At lower scan rates, lithium ions have sufficient time to diffuse into the deeper bulk area or regular geometry regions of the electrode material, leading to a larger battery-like current contribution. In contrast, at higher scan rates, diffusion into the deeper bulk regions does not keep up with the scan rate, while migration of ions in the irregular superficial areas is still comparable to the scan rate. As a result, the contribution of pseudocapacitive current increases with higher scan rates [50]. Since pseudocapacitive current originates from a Faradaic intercalation process, it contributes to the selectivity of the LMO electrodes.

As shown in Figure 11b, the lithium adsorption capacity per gram of active material slightly decreases with increasing electrode thickness at low scan rates. This is due to longer diffusion pathways in both the electrolyte and solid active material phases for thicker electrodes [72]. At higher scan rates, thicker electrodes may exhibit a decrease in specific lithium adsorption capacity due to increased concentration overpotential [73]. However, this rate-limiting process can be mitigated by designing electrodes with low tortuosity or a porosity gradient [74,75].

The results in Figure 11c demonstrate that the area-specific capacity for lithium intercalation is proportional to the thickness of the Li-selective electrode. The area-specific lithium adsorption capacity for the 1500 µm thick electrode is 15 times that of the 400 µm electrode, which represents the typical maximum thickness achievable with conventional fabrication methods. A comparison of the area-specific lithium adsorption capacity between this study and others is presented in Table 6. The area-specific capacity in this work is 3 to 11 times higher than that reported in other studies. By using thicker electrodes prepared in this study, the cost and energy consumption per unit mass of lithium chloride extracted can be significantly reduced.

Table 6.

Data of adsorption capacity per square centimeter reported in literature.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an innovative method for fabricating thick, crack-free LMO electrodes was developed. According to the CV results, the thick LMO electrodes, integrated with a PVDF-LiTFSI polymer electrolyte, demonstrated excellent Li+ selectivity of 156.7 over Na+ ions under voltage-controlled conditions. Notably, 82% of the lithium adsorption capacity was maintained after 30 cycles. Electrochemical tests with synthetic brine (Salar de Atacama) showed that the thick electrodes achieved an unprecedented Li+ areal capacity of 0.282 mg/cm2, which is superior to the performance of thin electrodes. Furthermore, both CV and XRD measurements confirmed that the lithium adsorption capacity was driven by both Faradaic diffusion-controlled (battery-like) intercalation and pseudocapacitive reactions. The technique introduced in this work offers the potential for significantly reducing both the manufacturing and operational costs associated with electrochemical lithium extraction from brines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y., H.L., M.A. and X.Z.; methodology, D.Y., H.L. and X.Z.; validation, D.Y. and X.Z.; formal analysis, D.Y. and X.Z.; investigation, D.Y., J.Q. and M.A.; data curation, D.Y. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.Y., H.L. and X.Z., J.Q.; visualization, D.Y.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Xuyang Zhang, Xiangyang Zhou, and the DOE Geothermal Lithium Extraction Prize.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LMO | Lithium manganese oxide |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| LCE | Lithium carbonate equivalent |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| LISs | Lithium-ion sieves |

| PPy | polypyrrole |

| NIPS | Non-solvent induced phase separation |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SSC | Silver chloride electrode |

| ESR | Equivalent series resistance |

| EDLs | Electric double layers |

References

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2024. IEA, Paris. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- S&P Global Commodity Insights. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/en (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Dessemond, C.; Lajoie-Leroux, F.; Soucy, G.; Laroche, N.; Magnan, J.-F. Spodumene: The Lithium Market, Resources and Processes. Minerals 2019, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Shi, A.; Yin, H.; Li, K.; Chao, Y. Global lithium product applications, mineral resources, markets and related issues. Nat. Sci. 2024, 1, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chai, G.; Zhang, Y. Research progress on lithium extraction from salt-lake brine. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 148, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, R.L.L.; Salvi, S. Brine grades in Andean salars: When basin size matters A review of the Lithium Triangle. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, C.; Miranda, P.H.; Perrin, M.; Poggi, P. Assessment of world lithium resources and consequences of their geographic distribution on the expected development of the electric vehicle industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, L.A.; Boutt, D.; Butler, K.; Russo, A.; Jenckes, J.; Moran, B.; Kirshen, A. Lithium Brines: Origin, Characteristics, and Global Distribution. Econ. Geol. 2025, 120, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.W.; Kang, D.J.; Tran, K.T.; Kim, M.J.; Lim, T.; Tran, T. Recovery of lithium from Uyuni salar brine. Hydrometallurgy 2012, 117–118, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Gui, W.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y. Systemic and Direct Production of Battery-Grade Lithium Carbonate from a Saline Lake. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 16502–16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, C.; Zhou, A.; He, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J. A positively charged composite nanofiltration membrane modified by EDTA for LiCl/MgCl2 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 186, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mo, Y.; Qing, W.; Shao, S.; Tang, C.Y.; Li, J. Membrane-based technologies for lithium recovery from water lithium resources: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 591, 117317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-Y.; Cai, L.-J.; Nie, X.-Y.; Song, X.; Yu, J.-G. Separation of magnesium and lithium from brine using a Desal nanofiltration membrane. J. Water Process Eng. 2015, 7, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Rehman, D.; Sun, P.-F.; Deshmukh, A.; Zhang, L.; Han, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Park, H.-D.; Lienhard, J.H.; et al. Novel Positively Charged Metal-Coordinated Nanofiltration Membrane for Lithium Recovery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 16906–16915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Li, T.; Li, S.; Yin, S.; Zhang, L. Application of Nanofiltration Membrane Based on Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in the Separation of Magnesium and Lithium from Salt Lakes. Seperations 2022, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ying, Y.; Mao, Y.; Peng, X.; Chen, B. Polystyrene Sulfonate Threaded through a Metal–Organic Framework Membrane for Fast and Selective Lithium-Ion Separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15120–15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T. Development of technology for recovering lithium from seawater by electrodialysis using ionic liquid membrane. Fusion Eng. Des. 2013, 88, 2956–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.-Y.; Sun, S.-Y.; Sun, Z.; Song, X.; Yu, J.-G. Ion-fractionation of lithium ions from magnesium ions by electrodialysis using monovalent selective ion-exchange membranes. Desalination 2017, 403, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Yu, P.; Yan, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z. Fabrication of lithium ion imprinted hybrid membranes with antifouling performance for selective recovery of lithium. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Meng, M.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Yan, Y. Highly selective, regenerated ion-sieve microfiltration porous membrane for targeted separation of Li+. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, P.; Qi, P.; Gao, C. Adsorption and desorption properties of Li+ on PVC-H1.6Mn1.6O4 lithium ion-sieve membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 235, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Nisola, G.M.; Vivas, E.L.; Limjuco, L.A.; Lawagon, C.P.; Seo, J.G.; Kim, H.; Shon, H.K.; Chung, W.-J. Mixed matrix nanofiber as a flow-through membrane adsorber for continuous Li+ recovery from seawater. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 510, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberti, M. Pathways to Greener Primary Lithium Extraction for a Really Sustainable Energy Transition: Environmental Challenges and Pioneering Innovations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wan, P.; Gasem, K.; Wang, K.; He, T.; Adidharma, H.; Fan, M. Extraction of lithium with functionalized lithium ion-sieves. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 84, 276–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Miyai, Y.; Kanoh, H.; Ooi, K. Lithium+ extraction/insertion with spinel-type lithium manganese oxides. Characterization of redox-type and ion-exchange-type sites. Langmuir 1992, 8, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-H.; Li, S.-P.; Sun, S.-Y.; Yin, X.-S.; Yu, J.-G. LiMn2O4 spinel direct synthesis and lithium ion selective adsorption. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, L.; Kölbel, T.; Herrmann, L.; Kaymakci, E.; Ghergut, I.; Poirel, A.; Schneider, J. Lithium extraction from geothermal brines in the Upper Rhine Graben: A case study of potential and current state of the art. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 221, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snydacker, D.H.; Hegde, V.I.; Aykol, M.; Wolverton, C. Computational Discovery of Li–M–O Ion Exchange Materials for Lithium Extraction from Brines. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6961–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Kim, S.; Hatton, T.A.; Mo, H.; Waite, T.D. Lithium recovery using electrochemical technologies: Advances and challenges. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Lin, D.; Hsu, P.-C.; Liu, B.; Yan, G.; Wu, T.; Cui, Y.; Chu, S. Lithium Extraction from Seawater through Pulsed Electrochemical Intercalation. Joule 2020, 4, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trócoli, R.; Battistel, A.; La Mantia, F. Nickel Hexacyanoferrate as Suitable Alternative to Ag for Electrochemical Lithium Recovery. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Yu, S.-H.; Kim, C.; Sung, Y.-E.; Yoon, J. Highly selective lithium recovery from brine using a λ-MnO2–Ag battery. PCCP 2013, 15, 7690–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Electrochemical lithium recovery from brine with high Mg2+/Li+ ratio using mesoporous λ-MnO2/LiMn2O4 modified 3D graphite felt electrodes. Desalination 2021, 511, 115112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, J. Electrochemical Lithium Recovery with a LiMn2O4–Zinc Battery System using Zinc as a Negative Electrode. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missoni, L.L.; Marchini, F.; del Pozo, M.; Calvo, E.J. A LiMn2O4-Polypyrrole System for the Extraction of LiCl from Natural Brine. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, L.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. Pulsed electric field controlled lithium extraction process by LMO/MXene composite electrode from brines. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Liu, J.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y. Highly Selective and Pollution-Free Electrochemical Extraction of Lithium by a Polyaniline/LixMn2O4 Cell. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Rollag, K.M.; Li, J.; An, S.J.; Wood, M.; Sheng, Y.; Mukherjee, P.P.; Daniel, C.; Wood, D.L. Enabling aqueous processing for crack-free thick electrodes. J. Power Sources 2017, 354, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumberg, J.; Müller, M.; Diehm, R.; Spiegel, S.; Wachsmann, C.; Bauer, W.; Scharfer, P.; Schabel, W. Drying of Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes for Use in High-Energy Cells: Influence of Electrode Thickness on Drying Time, Adhesion, and Crack Formation. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 1900722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-S.; Wu, Z.; Petrova, V.; Xing, X.; Lim, H.-D.; Liu, H.; Liu, P. Analysis of Rate-Limiting Factors in Thick Electrodes for Electric Vehicle Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.B.; Tirumkudulu, M.S. Cracking in Drying Colloidal Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 218302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagonia, M.S.; Brogioli, D.; La Mantia, F. Effect of Current Density and Mass Loading on the Performance of a Flow-Through Electrodes Cell for Lithium Recovery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, E286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Rodrigue, D. A Review on Porous Polymeric Membrane Preparation. Part I: Production Techniques with Polysulfone and Poly (Vinylidene Fluoride). Polymers 2019, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.C. Preparation of a new crystal form of manganese dioxide: λ-MnO2. J. Solid State Chem. 1981, 39, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Ouyang, W.; Li, Z.; Han, J. Direct numerical simulation of continuous lithium extraction from high Mg2+/Li+ ratio brines using microfluidic channels with ion concentration polarization. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 556, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; He, L.; Zhao, Z. Lithium extraction from high Mg/Li brine via electrochemical intercalation/de-intercalation system using LiMn2O4 materials. Desalination 2021, 503, 114935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldama, I.; Barranco, V.; Ibañez, J.; Amarilla, J.M.; Rojo, J.M. A Procedure for Evaluating the Capacity Associated with Battery-Type Electrode and Supercapacitor-Type One in Composite Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani, M.; Donne, S.W. Method Comparison for Deconvoluting Capacitive and Pseudo-Capacitive Contributions to Electrochemical Capacitor Electrode Behavior. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Akin, M.; Zhou, X.; Mansour, A.N.; Ko, J.K.; Waller, G.H.; Martin, C.A.; et al. Electrochemical and In Situ Spectroscopic Study of the Effect of Prussian Blue as a Mediator in a Solid-State Supercapacitor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 106505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiahangarani, P.; Farhan, G.; del Mundo, D.; Schoetz, T. Charge Storage Mechanisms in Batteries and Capacitors: A Perspective of the Electrochemical Interface. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2404704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistel, A.; Palagonia, M.S.; Brogioli, D.; La Mantia, F.; Trócoli, R. Electrochemical Methods for Lithium Recovery: A Comprehensive and Critical Review. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chladil, L.; Kunický, D.; Kazda, T.; Vanýsek, P.; Čech, O.; Bača, P. In-situ XRD study of a Chromium doped LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 cathode for Li-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, J.S.; Joo, H.; Sung, Y.-E.; Yoon, J. Understanding the Behaviors of λ-MnO2 in Electrochemical Lithium Recovery: Key Limiting Factors and a Route to the Enhanced Performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9044–9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, E.J.; Marchini, F. Method and Electrochemial Device for Low Environmental Impact Lithium Reovery from Aqueous Solutions. United States Patent Application No.: US 2014/0076734 A1, 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.-Y.; Ji, Z.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Li, F.; Yuan, J.-S. Effect of Impurity Ions in the Electrosorption Lithium Extraction Process: Generation and Restriction of “Selective Concentration Polarization”. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11834–11844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.-Y.; Ji, Z.-Y.; Chen, Q.-B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Wang, S.-Z.; Li, F.; Yuan, J.-S. Effect of coexisting ions on recovering lithium from high Mg2+/Li+ ratio brines by selective-electrodialysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 207, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, F.; Rubi, D.; del Pozo, M.; Williams, F.J.; Calvo, E.J. Surface Chemistry and Lithium-Ion Exchange in LiMn2O4 for the Electrochemical Selective Extraction of LiCl from Natural Salt Lake Brines. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 15875–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gong, J.; Hu, X. Electrochemically Controlled Reversible Lithium Capture and Release Enabled by LiMn2O4 Nanorods. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagonia, M.S.; Brogioli, D.; La Mantia, F. Lithium recovery from diluted brine by means of electrochemical ion exchange in a flow-through-electrodes cell. Desalination 2020, 475, 114192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yu, X.; Li, M.; Duo, J.; Guo, Y.; Deng, T. Green recovery of lithium from geothermal water based on a novel lithium iron phosphate electrochemical technique. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Choi, S.; Shin, J.; Dinh, H.-C.; Choi, J.W. An Electrochemical Cell for Selective Lithium Capture from Seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 9415–9422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitrakar, R.; Makita, Y.; Ooi, K.; Sonoda, A.A. Lithium recovery from salt lake brine by H2TiO3. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 8933–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Fan, Q.; Hu, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, J.; Xu, J.; Pan, B.; Lu, Z. Continuous flow extraction of lithium from brine using silica-coated LMO beads. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 2202–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Foster, J.M.; Gully, A.; Krachkovskiy, S.; Jiang, M.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Protas, B.; Goward, G.R.; Botton, G.A. Three-dimensional investigation of cycling-induced microstructural changes in lithium-ion battery cathodes using focused ion beam/scanning electron microscopy. Power Sources 2016, 306, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Pieczonka, N.P.W.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Harris, S.; Powell, B.R. Understanding the capacity fading mechanism in LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4/graphite Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 90, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Ran, Y.; Qian, Z.; Zhao, B.; Li, C.; Liu, Z. Overcoming polarizaiton and dissolution of manganese-based electrodes to enhance stability in electrochemical lithium extraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 155009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Kong, X.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, K.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Cao, A. Three-dimensional carbon nanotube sponge supported LiMn2O4 hybrid for electrochemical lithium extraction with high capacity and stability. Desalination 2025, 614, 119129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, L.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wang, W.; Ying, J.-Y.; Fan, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-Z. Triple synergistic effects fo bismuth doping in spinel-LiMn2O4: A path to high-performance electrochemical lithium extraction from salt-lake brine. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildi, C.; Cabello, G.; Michoff, M.Z.; Velez, P.; Leiva, E.; Calvente, J.J.; Andreu, R.; Cuesta, A. Super-Nernstian Shifts of Interfacial Proton-Coupled Electron Transfers: Origin and Effect of Noncovalent Interactions. J. Phys. Chemsitry C 2015, 120, 15586–15592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, J.; Josowicz, M. Nernstian and non-Nernstian potentiometry. Solid State Ion. 1997, 94, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, D. IR elimination in electrochemical cells. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1978, 88, 309–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Reichman, B.; Wang, X. Modeling the effect of electrode thickness on the performance of lithium-ion batteries with experimental validation. Energy 2019, 186, 115864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, J.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Battaglia, V.S. A comprehensive understanding of electrode thickness effects on the electrochemical performances of Li-ion battery cathodes. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 71, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Chen, C.; Kirsch, D.; Hu, L. Thick Electrode Batteries: Principles, Opportunities, and Challenges. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadesigan, V.; Methekar, R.N.; Latinwo, F.; Braatz, R.D.; Subramanian, V.R. Optimal Porosity Distribution for Minimized Ohmic Drop across a Porous Electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Joo, H.; Moon, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, J. Rapid and selective lithium recovery from desalination brine using an electrochemical system. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanoh, H.; Ooi, K.; Miyai, Y.; Katoh, S. Electrochemical Recovery of Lithium Ions in the Aqueous Phase. Sep. Sci. Technol. 1993, 28, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).