Abstract

Lithium-ion batteries are widely used in energy storage systems and consumer electronics; however, long-term usage leads to capacity degradation, which affects system efficiency and safety. Existing studies have largely focused on individual cells and their SOH and SOC metrics, with less attention paid to larger battery packs, while the SOP more effectively reflects the overall operational characteristics of a battery pack. Therefore, this study proposes a parameter-optimized prediction method based on PSO and SVM, using SOP as a key health indicator for life prediction. In this method, the global optimal solution is obtained by simulating the collaborative search behavior of the particle swarm, dynamically updating particle positions and velocities; this solution determines the SVM’s critical parameters, namely the kernel parameter g and the penalty coefficient c, which are then used to train the SVM model to enhance its generalization ability and prediction accuracy. The results indicate that the PSO-SVM model can effectively capture the degradation characteristics of battery packs, achieving high-precision SOP prediction, with most prediction errors below 5% and the maximum error reaching 10.91%.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of global energy demand and the increasing severity of environmental pollution, the development of clean energy and electrification is accelerating. Lithium-ion batteries, due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and environmental friendliness, have been widely applied in renewable energy storage and consumer electronics, such as mobile phones, laptops, and electric vehicles. However, during prolonged use, lithium-ion batteries inevitably undergo performance degradation, primarily manifested as capacity fade and increased internal resistance, which in turn reduces system efficiency and increases safety risks. To ensure the reliability and safety of battery systems, it is necessary to estimate battery states, particularly the State of Health (SOH) and Remaining Useful Life (RUL), which are key components of Battery Management Systems (BMS) [1,2,3,4].

In the field of Prognostics and Health Management (PHM) for lithium-ion batteries, researchers have proposed various prediction methods, including degradation model-based methods, data-driven methods, and hybrid approaches [5,6,7]. Degradation model-based methods typically rely on electrochemical principles or equivalent circuit models to characterize battery operation and degradation mechanisms. These methods provide a clear mathematical description of device degradation and possess strong physical interpretability; however, they depend on complex parameter identification and experimental conditions, making them difficult to adapt to dynamic and complex real-world operating environments [8]. Data-driven methods, on the other hand, leverage statistical analysis, machine learning, and deep learning techniques to extract degradation patterns from large volumes of experimental or operational data and construct predictive models. With the development of artificial intelligence, techniques such as ensemble learning, deep neural networks, and Transformers have been increasingly applied to SOH and RUL prediction. Data-driven methods generally outperform other approaches in terms of prediction accuracy and generalization ability; however, they require substantial fault data to ensure reliability. As manufacturing quality improves and equipment becomes more reliable, collecting large amounts of failure data within a short time becomes challenging, thereby limiting the accuracy of these models [9,10,11,12]. Hybrid prediction methods, which integrate model-based and data-driven approaches, have received increasing attention in recent years [13,14,15]. By combining degradation modeling with data-driven techniques, hybrid methods retain the physical interpretability of models while enhancing adaptability to complex degradation processes [16,17].

Research on lithium-ion battery performance degradation has been steadily expanding; however, most studies have focused on single-cell degradation prediction, with insufficient attention paid to battery pack systems, which are more prevalent in practical applications [18,19,20]. Battery packs consist of multiple cells connected in series and parallel, and the heterogeneity and interactions among individual cells make the degradation mechanisms more complex. Relying solely on single-cell models is therefore insufficient to accurately capture pack-level characteristics. Furthermore, most studies use State of Charge (SOC) or SOH as the primary indicators, whereas research on State of Power (SOP) remains relatively limited [21,22,23,24]. SOP directly affects electric vehicle acceleration performance and energy recovery efficiency, and understanding its degradation patterns is critical for extending battery life and ensuring safety, yet it has not been sufficiently considered in life prediction studies. In addition, existing methods typically adopt fixed thresholds to determine the end-of-life, such as defining failure when capacity drops to 80% of the rated value. With the development of cascaded utilization and secondary applications, the life threshold requirements vary across different scenarios, making fixed thresholds inadequate for multi-scenario applications. Finally, balancing prediction accuracy and computational efficiency remains a key challenge. Physical models are computationally complex and often cannot meet real-time requirements, while deep learning methods, although highly accurate, demand large amounts of training data and computational resources, limiting their practical application in BMS [25,26,27].

To address the aforementioned limitations, researchers have proposed a series of improved methods. The combination of optimization algorithms and deep learning provides a new approach to enhance prediction accuracy and adaptability. Zhang et al. [28] proposed an improved Particle Swarm Optimization-Extreme Learning Machine (PSO-ELM) modeling strategy to enhance the accuracy of lithium-ion battery SOH estimation and the adaptability of RUL prediction. This method optimizes the parameters of the Extreme Learning Machine in conjunction with the PSO algorithm, effectively improving prediction accuracy and robustness, with empirical comparisons confirming its performance advantages. Lyu et al. [29] proposed a transfer-driven battery SOH prediction method, achieving cross-level application from single cells to battery packs. By integrating adaptive differential model decomposition techniques, this approach effectively bridges the gap between laboratory conditions and real-world operating scenarios, and multi-scenario experiments verified its accuracy and reliability under different application conditions. Zhang et al. [18] proposed a model-data fusion method for real-time prediction of the remaining useful life of lithium batteries. This approach employs a generalized Wiener process model combined with optimization and filtering techniques to achieve dynamic parameter updating, thereby ensuring continuity and accuracy of prediction. Experimental results demonstrate that the method achieves high accuracy and strong real-time adaptability on both public and measured datasets. Che et al. [30] proposed a “cell-to-pack” prognostic framework, successfully transferring health indicators extracted from individual cells to battery packs and achieving low prediction errors. This study demonstrates that degradation-related features derived at the cell level (e.g., health indicators based on voltage–capacity curves) remain valid and informative at the pack level. Naylor Marlow [31] investigated the degradation of parallel-connected lithium-ion battery packs under thermal gradients and uneven current conditions. The results indicate that, although parallel configurations introduce non-uniform current distribution and temperature variations, the dominant aging mechanisms—such as SEI layer growth, impedance increase, and active material loss—remain fundamentally the same as those observed in individual cells.

It can be observed that research on battery PHM exhibits three major trends: first, the focus is expanding from single cells to battery packs; second, prediction indicators are extending from single metrics such as SOC or SOH to multidimensional health factors, including SOP. In the future, battery life prediction frameworks that integrate optimization algorithms, transfer learning, and multi-source information are expected to enhance model generality and reliability across multiple operating conditions and scenarios, while maintaining high accuracy and computational efficiency.

Therefore, exploring battery life prediction methods based on multi-method integration can not only advance PHM theory but also hold significant engineering value for the safe and efficient operation of new energy vehicles and energy storage systems. This study proposes a battery pack SOP prediction method based on Particle Swarm Optimization-Support Vector Machine (PSO-SVM). The method leverages the strong global search capability of PSO and the excellent nonlinear modeling and generalization ability of SVM, thereby improving the accuracy of SOP prediction for battery packs.

2. Experimental Data Acquisition

This study utilized a total of 32 lithium-ion cells, each with a rated capacity of 0.8 Ah. To ensure experimental consistency, all cells were sourced from the same production batch and subjected to standardized charge–discharge procedures in a temperature-controlled chamber to guarantee uniform initial capacity and SOC levels. Although minor individual differences and system measurement errors exist, these measures effectively minimized discrepancies between battery packs, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent model training and validation. The experiments were divided into two main categories. The first category consisted of 8 cells selected for single-cell experiments, used solely for investigating individual performance degradation [32]. The remaining 24 cells were used for pack-level experiments and further subdivided as follows: 15 cells were evenly divided into 3 groups, with each group of 5 cells connected in parallel to form three battery packs with a theoretical rated capacity of 4.0 Ah each; the remaining 9 cells were evenly divided into 3 groups, with each group of 3cells connected in parallel, forming three additional battery packs with a theoretical rated capacity of 2.4 Ah each [33]. The charge–discharge cycling tests were conducted using equipment that can measure voltages in the range of 0–5 V and currents in the range of 0–6 A [34].

This study designed two types of test protocols for battery degradation experiments: baseline testing and complex testing [35]. To ensure the repeatability and reliability of the experimental results, the baseline testing protocol was selected. Corresponding to this experimental design, test conditions were configured to match the capacity characteristics of eight single cells and six battery packs: the eight single cells were subjected to cyclic charging and discharging at a constant current of 0.8 A, while the 2.4 Ah battery packs were charged and discharged at 2.4 A constant current, and the 4 Ah battery packs at 4 A constant current [36].

In this experiment, alternating charge–discharge currents were applied as a complex test to simulate load fluctuations in actual operating environments and to investigate the degradation characteristics of batteries under different current conditions [37]. Taking a 2.4 Ah battery pack as an example, the charging method is the same as in the baseline test, but the initial discharge current of 2.4 A gradually increases to 6.0 A during the experiment, with the cutoff discharge voltage set at 2.7 V. This approach allows for a comparison of the effects of different current conditions on battery performance degradation. Finally, to test and validate the dynamic characteristics of the batteries, periodic verification test cycles were conducted [38]. In this stage, both single cells and battery packs underwent multiple current intensities and staged charge–discharge strategies, providing a more comprehensive assessment of their dynamic behavior and further validating the reliability of the aforementioned experimental results [39]. In the experiment, the testing equipment used was capable of directly acquiring data such as the battery’s voltage, current, and power. This study primarily focuses on transfer prediction for battery packs. To simplify the complex testing conditions, only the degradation trend data of the batteries under offline baseline testing are selected for analysis [40].

In lithium-ion battery experiments, the constant current-constant voltage (CC-CV) charge–discharge strategy is the most commonly used control method. During charging, the battery is initially charged at a constant current until its voltage reaches the preset cutoff voltage; this phase is known as the constant current charging stage. When the battery approaches full capacity, constant current charging alone can no longer increase the battery’s charge, and the process transitions to the constant voltage stage. In this stage, the battery voltage is maintained constant while the current gradually decreases over time, ensuring that the battery is fully charged.

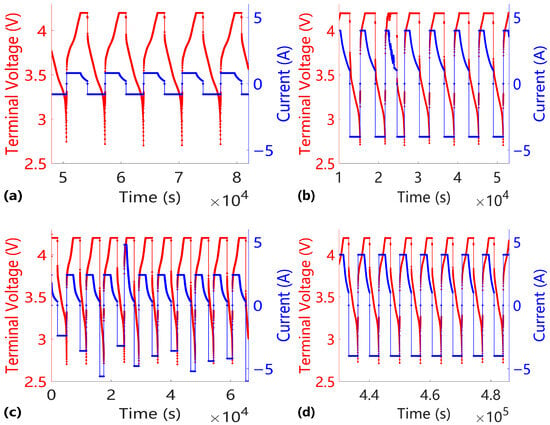

Figure 1 shows the current-voltage time series of the battery under different testing modes, with the horizontal axis representing time (s). The red curve represents the battery voltage, corresponding to the left vertical axis, while the blue curve represents the current, corresponding to the right vertical axis [41]. Figure 1a,b depict charge–discharge cycles under baseline testing, whereas Figure 1c,d show charge–discharge cycles under complex testing conditions [42].

Figure 1.

Current–voltage time series under different testing modes. (a) Current–voltage profile of a single cell under baseline testing; (b) Current–voltage profile of a 4.0 Ah battery pack under baseline testing; (c) Current–voltage profile of a 2.4 Ah battery pack under complex testing; (d) Current–voltage profile of a 4.0 Ah battery pack under complex testing.

3. Methodology Overview

In lithium-ion battery time series prediction tasks, the classification performance of SVM is highly dependent on the kernel parameter g and the penalty coefficient c. Specifically, g determines the feature width of the kernel function, while c reflects the tolerance for error samples. These two parameters directly affect the model’s generalization ability and solution accuracy; inappropriate selection may lead to insufficient generalization or overfitting. Traditional methods such as manual parameter tuning or grid search are inefficient and prone to converging to local optima.

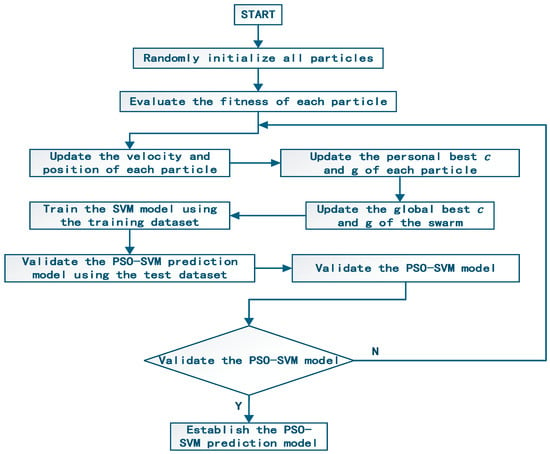

Therefore, this study introduces the PSO algorithm. PSO simulates the foraging search behavior of a flock of birds, continuously adjusting the velocity and position of particles during iterations to gradually approach the optimal solution. In this method, a particle’s position represents a parameter set, and the fitness function is measured by the SVM’s classification performance on a validation set (e.g., true positive rate). The updates of the personal best (pbest) and global best (gbest) are performed as follows: if a particle’s current performance exceeds its historical best, pbest is updated; if its performance exceeds the global best, gbest is updated. After multiple iterations, the global best particle obtained corresponds to the optimal SVM parameters. The overall process is illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Framework of PSO-SVM Model.

3.1. SVM Structure

SVM was first proposed by Vapnik to address classification and regression problems. As a supervised learning method based on the principle of Structural Risk Minimization (SRM), SVM demonstrates strong generalization ability in pattern recognition and prediction tasks, overcoming common issues in traditional machine learning methods such as susceptibility to local optima, slow convergence, and overfitting.

The fundamental idea of SVM is to find an optimal hyperplane in the input space that separates data points of different classes. In the case of linearly separable data, the optimal hyperplane maximizes the margin between the two classes, thereby achieving robust classification results. When the data are not linearly separable, SVM employs a kernel function to map the input features into a high-dimensional space, where an optimal linear separating hyperplane can still be constructed. The SVM regression function in the high-dimensional feature space is expressed as:

In the equation: (z) is a nonlinear mapping function from the Rm space to the H space; ω is the weight vector, and b is the bias term.

Based on the principle of structural risk minimization, the problem is transformed into minimizing a linear risk functional:

In the equation: c is the penalty coefficient, and are slack variables. Equation (2) represents a standard constrained optimization problem, which can be solved using the Lagrange function method. Consequently, the SVM regression function f(x) can be expressed as:

In the equation, and denote Lagrange multipliers, and represents the kernel function.

The kernel function is defined as follows:

In the equation, is the width parameter of the radial basis function kernel. The penalty factor c and the kernel width g are two critical parameters that directly affect the prediction accuracy of the model. Selecting an appropriate combination of c and is essential for ensuring the classification capability of the SVM.

SVM maps inputs into a high-dimensional space through a kernel function, enabling it to capture complex nonlinear relationships. Moreover, SVM is insensitive to noise and outliers, making it suitable for data scenarios with significant disturbances. With these characteristics, SVM provides a mathematically tractable framework for modeling battery aging under complex operating conditions.

Based on this, the present study employs a sliding window approach to construct the input features for the SVM. The window length is set to w = 50 with a step size of 1, meaning that the target value at the 51st time step is predicted using the historical data from the preceding 50 time steps. This windowing strategy effectively captures the dynamic trends of battery performance over time and transforms the time-series prediction problem into a standard supervised learning task.

Regarding feature design, the input variables mainly consist of two types of information: first, the cumulative cycle count, which characterizes the long-term degradation process of the battery; second, the SOP parameters, which reflect the instantaneous output capability of the battery at each time step. This combination of features allows the model to capture both the slow-varying aging trends and the rapidly changing performance behaviors, providing more comprehensive degradation information.

For the prediction model, a radial basis function (RBF) kernel is used to establish a nonlinear mapping between the input features and the prediction target. The entire modeling process operates in a single-step prediction mode, enabling the model to continuously update predictions along the progressing time series and enhancing its sensitivity to local variations.

3.2. SVM Based PSO for Optimization

To improve the prediction accuracy of lithium-ion battery time series data, this study proposes an automatic SVM hyperparameter optimization method based on the PSO algorithm. To address the inefficiency and susceptibility to local optima associated with manually and randomly assigned hyperparameters, the PSO algorithm is employed to achieve global optimization by simulating the collective behavior of flocks of birds or schools of fish. It models the movement of particles within the search space to identify the best possible solutions to the problem. With this behavior-driven mechanism, PSO can efficiently configure the key SVM hyperparameters, namely the kernel parameter and the penalty coefficient c, thereby significantly enhancing the prediction performance and robustness of the SVM model.

PSO completes optimization tasks by simulating the cooperative search behavior observed in flocks of birds or schools of fish. The overall optimization process can be divided into three main stages: initialization, particle performance evaluation, and particle update. Initially, PSO randomly generates a swarm of particles within a predefined search space and assigns each particle a random initial velocity, with each particle representing a potential solution to the optimization problem. The random initialization simulates the uncertainty of the flock school regarding the target position and ensures that the particle swarm covers a wide area during the initial search stage, thereby reducing the likelihood of becoming trapped in local optima.

During the performance evaluation phase, PSO evaluates the current position of each particle to assess the quality of the solution. Each particle records the best position it has found so far, referred to as the individual historical best. Simultaneously, the entire swarm cooperates to determine the global best position, which corresponds to the best-performing solution among all particles.

After evaluating the performance of the particles, the particle update phase begins. In PSO, each particle dynamically adjusts its velocity based on its current velocity, its historical best position, and the best positions of neighboring particles. The classical PSO update formula is as follows:

Here, and represent the position and velocity of the i-th particle at iteration t, respectively; is the inertia weight, which regulates the balance between global and local search; and denote the individual best solution and the global best solution, respectively; and are learning factors controlling the influence of individual and social learning; and are random numbers in the range [0, 1], introduced to enhance the stochasticity of the search. The optimization process terminates when the termination condition is met, which is typically defined either by the maximum number of iterations or when the optimal position found by the particle swarm satisfies a fitness threshold.

To ensure that the SVM model achieves optimal performance under varying sample sizes and feature distributions, this study encodes the penalty parameter C and the RBF kernel parameter gas the primary dimensions of each particle, and employs PSO to perform global adaptive optimization. During initialization, particles are randomly distributed within the predefined parameter search space to guarantee sufficient diversity in candidate solutions. Subsequently, through iterative velocity–position updates, the particle swarm progressively approaches the optimal solution, continuously refining the combinations of c and to enhance the generalization capability of the model. To further improve convergence stability and efficiency, a linearly decreasing inertia weight strategy is adopted, enabling strong global exploration in the early stages and more refined local search in the later stages of optimization.

Regarding the design of the fitness function, this study utilizes cross-validation-based mean squared error (MSE) as the evaluation metric to assess the performance of each candidate parameter combination. The incorporation of cross-validation effectively mitigates overfitting risks under limited data conditions, ensuring that the final parameter configuration maintains robust generalization performance. Through this mechanism, PSO is able to efficiently explore the high-dimensional and non-convex parameter space, thereby identifying the optimal hyperparameter configuration for the SVM model and ultimately improving its prediction accuracy.

In the application of SVM hyperparameter optimization, this mechanism can efficiently identify the optimal combination of parameters. Compared with traditional manual random assignment methods, this study employs the PSO algorithm to optimize the parameter combination of the SVM model, reducing computational cost and effectively avoiding local optima, thereby improving the classification accuracy of the SVM model.

4. Experimental Results

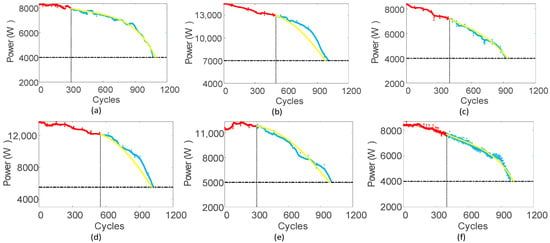

This study used battery power data over time as the input features for the model. Specifically, a sliding window approach was employed to use historical power data as inputs, enabling the capture of performance variations in the battery at different aging stages. These power features directly reflect the battery’s real-time output capability and degradation trends, serving as core indicators for predicting battery life and state of power. To ensure consistency in data processing and stability during training, all input features were normalized using the min–max method, mapping feature values to the [0, 1] range, thereby eliminating dimensional differences and accelerating model convergence. In this experiment, data from eight individual cells were used as the training set to train the PSO-SVM prediction model, while six battery packs were used as the test set to evaluate the model’s generalization ability and prediction accuracy. The experimental results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PSO-SVM Experimental Results. (a) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 1; (b) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 2; (c) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 3; (d) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 4; (e) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 5; (f) Comparison between predicted and actual values for Battery Pack 6.

The red solid line represents the baseline degradation trajectory drawn from historical measurement data. The subsequent blue solid line depicts the actual degradation trajectory of the battery packs, primarily used for comparison with the model’s predictions. The yellow solid line corresponds to the trajectory predicted by the PSO-SVM model, representing the model’s output. The horizontal black dashed line indicates the failure threshold optimized through reliability analysis, serving as the benchmark for assessing whether the battery has reached a failure state. In battery performance prediction, the failure threshold is generally set at 80%, which defines the prediction endpoint. The determination of the failure threshold mainly relies on empirical experience. To achieve a more comprehensive assessment of prediction performance and in consideration of lithium-ion battery “secondary utilization”, this study adopts a multiple-threshold scheme and applies it in the prediction process.

As observed from the Figure 3, the degradation trajectory predicted by the PSO-SVM model (yellow solid line) closely overlaps with the actual degradation trajectory (blue solid line) across all stages. This indicates that the model is able to effectively learn the degradation characteristics of individual cells and successfully transfer this knowledge to predict the performance of battery packs, demonstrating strong transfer learning and prediction capabilities. Moreover, the intersection point between the predicted trajectory and the failure threshold closely aligns with that of the actual degradation trajectory, further validating the model’s accuracy in remaining useful life prediction.

By comparing the results, it is evident that different prediction starting points have minimal impact on model performance. Whether predictions are made in the early or mid-to-late stages of battery life, the model consistently produces results that align with the actual degradation trends, indicating stable predictive performance under varying initial conditions. Additionally, the six battery packs used in the experiment consisted of three packs with three cells in parallel and three packs with five cells in parallel. Despite the individual differences and pack effects among these battery groups, the PSO-SVM model can still effectively predict their degradation trends.

For a quantitative analysis of prediction accuracy, Table 1 present the calculated mean percentage error (MPE) of different methods over the entire life cycle. The calculation formula of MPE is as follows:

Table 1.

Comparison of Prediction Errors over the Entire Life Cycle (%).

In the formula, denotes the actual failure time, which is a unique value. represents the mean of the predicted results, the average predicted failure time obtained at the i-th prediction starting point. denotes the absolute error between the predicted result at the i-th prediction starting point and the actual value.

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed PSO-SVM method, three representative categories of existing battery prediction approaches were selected for systematic comparison. These include physics-based models constructed on electrochemical mechanisms, the Differential Model Decomposition (DMD) method based on linear dynamic mode decomposition, and the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network leveraging deep learning representation capabilities. These three types of methods, respectively, represent mechanism-driven modeling, linear dynamic learning, and nonlinear deep learning, each with its own advantages and limitations. By comparing PSO-SVM with these approaches, the overall performance advantages of the proposed method in battery degradation prediction can be further validated.

Physics-based models rely on electrochemical mechanisms to establish the internal dynamic equations of a battery. For example, equivalent circuit models (ECM) can describe the physical relationships among voltage, current, and SOP. Such models typically include parameters related to electrochemical reaction kinetics, diffusion processes, and ohmic resistance. Because these models directly utilize the intrinsic mechanisms of the battery for prediction, they offer strong physical interpretability and can predict unseen operating conditions to some extent. However, they require accurate model parameters and experimental calibration; the parameters are complex, costly to obtain, and the models still struggle to fully capture the battery’s complex nonlinear characteristics.

Differential Model Decomposition (DMD) is a data-driven dynamic system decomposition method that decomposes time-series data into several dynamic modes and their evolution patterns, and predicts future system states through mode reconstruction. DMD can decompose time-varying data such as battery capacity and power into low-dimensional dynamic modes and thereby predict future states. Since DMD is essentially a linear decomposition method, its performance is limited when dealing with strongly nonlinear systems. Therefore, it is more suitable for short-term prediction or scenarios with weak nonlinear dynamics.

LSTM is an improved recurrent neural network that introduces forget, input, and output gates to effectively address the gradient vanishing and exploding problems found in traditional RNNs when processing long sequences. In battery SOP prediction, LSTM can learn nonlinear dynamic relationships from historical time-series data such as current, voltage, and temperature, enabling accurate forecasting of future SOP changes. Although LSTM can model complex nonlinear relationships, it requires large amounts of data to ensure prediction accuracy.

To ensure fairness and comparability among different methods, all models were processed under completely consistent experimental conditions: power features were extracted in a uniform manner, input data were normalized using the min–max method, identical strategies were applied for handling missing and anomalous values, and training and testing were performed following the same data partitioning scheme.

Table 1 presents the prediction errors of different methods for the six battery packs used in this study over their full life cycles. To ensure the fairness and reliability of the comparison results among different methods, all models included in the comparison were optimized and tuned to the same extent in this study. Whether it was the physics-based models, the DMD method, or the deep learning LSTM network, all were trained and validated under identical data conditions, evaluation metrics, and optimization procedures. By maintaining a consistent optimization strategy, potential biases arising from differences in model configurations can be effectively avoided, allowing the comparison results to more accurately reflect the intrinsic performance differences in each method in battery degradation prediction tasks. The results indicate that the PSO-SVM model consistently achieved the lowest prediction errors among all methods applies to the experimental battery packs, with an error range of 1.94–10.91%. For the other three approaches, the smallest prediction error observed was 13.22%, obtained by applying the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to Battery Pack 5. Nevertheless, this value still exceeds the maximum error produced by the PSO-SVM model.

Compared with the other battery packs, Battery Pack 1 exhibits a slightly higher prediction error. This phenomenon may be related to the individual differences and initial state characteristics of the battery pack itself. Although the PSO-SVM model can effectively capture the degradation patterns of individual cells and transfer them to battery pack-level predictions, micro-level differences may still exist among battery packs in a parallel configuration, such as uneven current distribution, deviations in initial health states, or consistency errors during the manufacturing process. These subtle differences can be amplified during the early stages of model prediction, resulting in relatively lower predictive performance for Battery Pack 1 compared to the other packs. Nevertheless, despite the slightly higher error for Battery Pack 1, the PSO-SVM model maintains high prediction accuracy throughout the entire cycle life, with a maximum overall error not exceeding 10.91%, and the predicted curve closely follows the actual capacity degradation trend. This indicates that the model’s overall predictive reliability remains effective.

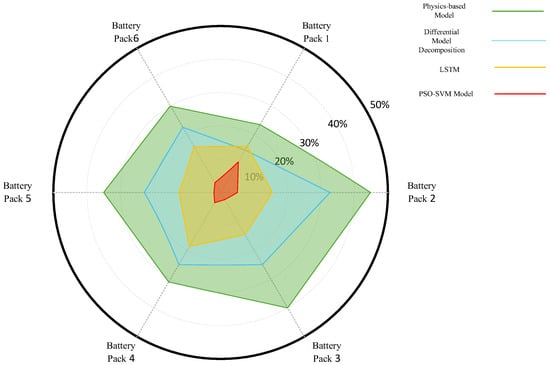

Figure 4 further reveals the overall differences among the models. The error distributions of the physics-based model and the difference decomposition model are located near the outer region of the radar chart, indicating larger overall deviations. In contrast, the LSTM network demonstrates an improvement but its prediction accuracy remains limited. The PSO-SVM model exhibits a more compact error region close to the center, suggesting that it consistently maintains lower and more stable error levels across different battery packs.

Figure 4.

Distribution of prediction errors.

Experimental results demonstrate that the PSO-optimized SVM model, trained on degradation data from individual battery cells, can achieve high prediction accuracy and maintain stability when applied to transfer prediction tasks for battery packs.

The experiments did not account for temperature gradients or charge–discharge characteristics under different C-rates, which may limit the model’s generalization capability under complex operating conditions. Although the idealized experiments provide a reliable basis for model development, the model’s performance and the accuracy of SOP predictions still need to be further validated under conditions closer to real-world applications.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a time series prediction model based on PSO and SVM. By leveraging the PSO algorithm to perform global optimization of the key hyperparameters of the SVM, the model significantly improves the prediction accuracy of battery performance degradation and effectively overcomes the arbitrariness and local optimum issues associated with traditional parameter selection methods. The experimental results demonstrate that the PSO-SVM model exhibits high consistency and reliability in remaining useful life prediction. The model is not only applicable to different battery packs but also maintains satisfactory prediction accuracy under various operating conditions, indicating its superior predictive capability compared to conventional methods. The prediction model proposed in this study, which is based on cycle count, can effectively characterize battery degradation under controlled experimental conditions; however, its applicability in real-world scenarios is limited. The actual aging process of batteries is influenced by multiple factors, including cumulative throughput, partial cycling, dynamic loads, and temperature variations. Relying solely on cycle count is insufficient to fully capture these complex mechanisms, which may lead to reduced prediction accuracy under non-standard operating conditions. Future research could consider incorporating multi-dimensional aging indicators, such as features based on cumulative throughput, state of power (SOP) parameters, or electrochemical signal-derived features, to enhance the model’s ability to represent battery performance degradation under complex operating conditions, thereby improving its generalization and reliability.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.L.; software, Y.W.; validation, Q.W.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, H.Y. and G.H.; resources, B.Y.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.H.; visualization, Z.H. and J.Y.; supervision, B.Y.; funding acquisition, Q.W. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is funded by the Science and Technology Project of China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd. (project number: 035300KC23120014).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hangang Yan, Qingbin Wang, Yun Yang, Xianzhong Zhao, Zudi Huang, and Yuxi Wang are employed by the Yunfu Power Supply Bureau of Guangdong Power Grid Co., Ltd. Authors Shi Liu, Bin Yi, Gancai Huang, and Jianfeng Yang are employed by the National Institute of Guangdong Advanced Energy Storage Co., Ltd. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ju, Y. Optimisation Analysis of Electric Vehicle Charging and discharging based on Bidirectional Power Converter Bipolar Structure. Mechatron. Syst. Control 2025, 53, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Fang, J. Thin-Walled Double Curvature Metal Cladding Stamping Wrinkling Mechanism and Control Methods. Mechatron. Syst. Control 2025, 53, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Barnes, P.; Zhang, H.; Efaw, C.; Wang, Y.; Park, B.; Li, B.; Chen, B.-R.; Evans, M.C.; Liaw, B.; et al. Calendar life of lithium metal batteries: Accelerated aging and failure analysis. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 65, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Su, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Wang, Z. Prognostics of Lithium-Ion batteries using knowledge-constrained machine learning and Kalman filtering. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 231, 108944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, H.; Xiao, N.C. A hybrid approach based on deep neural network and double exponential model for remaining useful life prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cui, X.; Meng, J.; Peng, J.; Lin, M. Data-driven transfer-stacking-based state of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Shi, J.; Yue, D.; Shi, G.; Lyu, D. A parallel weighted ADTC-Transformer framework with FUnet fusion and KAN for improved lithium-ion battery SOH prediction. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 159, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lyu, D.; Xiang, J. A model-data-fusion method for real-time continuous remaining useful life prediction of lithium batteries. Measurement 2024, 238, 115312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Ye, J. A Review of Parameter Identification and State of Power Estimation Methods for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Processes 2024, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Shen, W. A review of equivalent circuit model based online state of power estimation for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Vehicles 2021, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, W.; Ding, G. RUL prediction for lithium-ion batteries based on variational mode decomposition and hybrid network model. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 3109–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Sui, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Teodorescu, R.; Stroe, D.-I. Overview of machine learning methods for lithium-ion battery remaining useful lifetime prediction. Electronics 2021, 10, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggab, T.; Avila, M.; Vrignat, P.; Kratz, F. Unifying model-based prognosis with learning-based time-series prediction methods: Application to Li-ion battery. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 15, 5245–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Miao, J.; Tong, S.; Lu, Y. Early prediction of remaining useful life for Lithium-ion batteries based on a hybrid machine learning method. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, Y.A.; Eladl, A.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Gamel, S.A. Enhancing electric vehicle battery lifespan: Integrating active balancing and machine learning for precise RUL estimation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Zhang, B.; Liu, E.; Yang, T.; Xiang, J. Prognosis-enabled battery SOC estimation using a closed-loop approach with consideration of SOH degradation. J. Energy Storage 2025, 106, 113713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Niu, G.; Zhang, B.; Chen, G.; Yang, T. Lebesgue-time–space-model-based diagnosis and prognosis for multiple mode systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 1591–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Niu, G.; Liu, E.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.; Zhang, B. Uncertainty management and differential model decomposition for fault diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 5235–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Dewan, L. Trajectory tracking and balancing control of rotary inverted pendulum system using quasi-sliding mode control. Mechatron. Syst. Control 2022, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Hao, X. Review of state estimation and remaining useful life prediction methods for lithium–ion batteries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, F.; Zhang, C. Remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion battery based on extended Kalman particle filter. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Transfer learning-based hybrid remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries under different stresses. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3501810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xiang, J. Remain useful life prediction of rolling bearings based on exponential model optimized by gradient method. Measurement 2021, 176, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; He, Y. An integrated method of the future capacity and RUL prediction for lithium-ion battery pack. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 71, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Pan, R.; Chen, R.; Chen, Z. State-of-health estimation for the lithium-ion battery based on support vector regression. Appl. Energy 2018, 227, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Zhang, B.; Zio, E.; Xiang, J. Battery cumulative lifetime prognostics to bridge laboratory and real-life scenarios. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on PSO-TCN-Attention neural network. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, C.; Xie, Y.; Fernandez, C. Improved particle swarm optimization-extreme learning machine modeling strategies for the accurate lithium-ion battery state of health estimation and high-adaptability remaining useful life prediction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 080520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Liu, E.; Chen, H.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, J. Transfer-driven prognosis from battery cells to packs: An application with adaptive differential model decomposition. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tang, X.; Lin, X.; Nie, X.; Hu, X. Lifetime and aging degradation prognostics for lithium-ion battery packs based on a cell to pack method. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 35, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor Marlow, M.; Chen, J.; Wu, B. Degradation in parallel-connected lithium-ion battery packs under thermal gradients. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Sun, L.; Lyu, D. An efficient, generalizable method for equivalent circuit modeling of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 659, 238310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Onori, S.; Tao, S.; Howey, D.A.; Zhang, B.; Quade, K.L.; Dubarry, M.; Wu, B.; Li, W. Next steps for battery diagnostics. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2025, 6, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Shi, J.; Yue, D.; Shi, G.; Lyu, D. Estimating Lithium-Ion Battery Health Status: A Temporal Deep Learning Approach with Uncertainty Representation. IEEE Sens. Sens. J. 2025, 25, 26931–26943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, B.; Lyu, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, K. Estimation of lithium-ion battery health state using enhanced variational autoencoder and bidirectional gated recurrent unit based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Power Sources 2025, 655, 237957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Wang, X.; Niu, G.; Lyu, D.; Yang, T.; Zhang, B. Uncertainty management in lebesgue-sampling-based Li-ion battery SFP model for SOC estimation and RDT prediction. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 28, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Niu, G.; Lyu, D.; Yang, T.; Zhang, B. Low-cost adaptive LS-DEKF for SOC estimation and RDT prediction with SFP model. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3522609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Niu, G.; Liu, E.; Zhang, B.; Chen, G.; Yang, T.; Zio, E. Time space modelling for fault diagnosis and prognosis with uncertainty management: A general theoretical formulation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Wang, X.; Niu, G.; Lyu, D.; Yang, T.; Zhang, B. Lebesgue sampling-based Li-ion battery simplified first principle model for SOC estimation and RDT prediction. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 9524–9534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Liu, E.; Zhang, B.; Zio, E.; Yang, T.; Xiang, J. Threshold-varying assessment for prognostics and health management. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 55, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, T.; Xiang, J. Predicting Remaining Discharge Time for Lithium-ion Batteries based on Differential Model Decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd Industrial Electronics Society Annual On-Line Conference (ONCON), Online, 8–10 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.; Gao, S.; Zhao, D. A terminal sliding mode Learning control for a class of uncertain non-linear Systems. Mechatron. Syst. Control 2022, 50, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).