Abstract

Accurate estimation of lithium-ion battery (LIB) state of health (SOH) is critical for prolonging battery life and ensuring safe operation. To address the limitations of existing data-driven models in robustness and feature coupling, this paper presents a new Bagging-PiFormer framework for SOH estimation. The framework integrates ensemble learning with an improved Transformer architecture to achieve accurate and stable performance across various degradation conditions. Specifically, multiple PiFormer base models are trained independently under the Bagging strategy to enhance generalization. Each PiFormer consists of a stack of PiFormer layers, which combines a cross-channel attention mechanism to model voltage–current interactions and a local convolutional feed-forward network (LocalConvFFN) to extract local degradation patterns from charging curves. Residual connections and layer normalization stabilize gradient propagation in deep layers, while a purely linear output head enables precise regression of the continuous SOH values. Experimental results on three datasets demonstrate that the proposed method achieves the lowest MAE, RMSE, and MAXE values among all compared models, reducing overall error by 10–33% relative to mainstream deep-learning methods such as Transformer, CNN-LSTM, and GCN-BiLSTM. These results confirm that the Bagging-PiFormer framework significantly improves both the accuracy and robustness of battery SOH estimation.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are extensively utilized in numerous fields due to their advantages of high energy density, long lifespan, and less environmental impact [1,2]. As these applications increasingly depend on battery capacity, safety, and reliability, accurately predicting the performance of batteries becomes particularly important [3]. Among many performance indicators, state of health (SOH) is a critical index for evaluating cell aging, capacity fading, and power degradation. Hence, accurate and timely SOH prediction is crucial for operational maintenance, safety optimization, and lifespan extension of LIBs [4].

Recent studies increasingly highlight the importance of ensemble learning and hybrid architectures in addressing the instability of single models. Garse et al. [5] demonstrated that ensemble methods reduce RMSE by >15% compared to standalone models, while Figgener et al. [6] highlighted the necessity of real-world validation for industrial deployment. Additionally, feature engineering innovations, such as the coefficient of variation (COV) proposed by Liao et al. [7], simplify health indicator extraction, and cross-channel fusion techniques [8,9] have become essential for modeling complex degradation coupling.

Generally, SOH estimation methods primarily fall into two categories: model-based and data-driven. Model-based approaches assess battery degradation performance by tracking battery parameters via simple relationships based on experimental data or by estimating battery states via interpreting internal electrochemical characteristics [10,11]. For instance, a versatile equivalent circuit model (ECM) framework was proposed by integrating statistical analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and clustering techniques to develop an ECM that is capable of representing various battery cell types [12]. A lithium-ion battery calendar-life prognostic model was presented in the literature [13], integrating traditional electrochemical models, mechanistic models, hybrid empirical-mechanistic models, and machine learning-based models to predict the calendar life of LIBs. While these approaches offer significant advantages in terms of adaptability and accuracy for handling complex battery behaviors and diverse application demands, they also face many challenges, for instance, high data requirements, high computational complexity, and limited model interpretability.

During the recent decade, the advent of data-driven techniques has revolutionized the landscape of industrial system diagnosis as well as battery state estimation [14,15,16,17]. These approaches predominantly leverage machine learning algorithms, including support vector machines (SVMs), random forests (RFs), and deep learning architectures [15], to discern underlying patterns and trends from operational data. Unlike conventional methods, data-driven techniques uncover latent relationships and dynamic influences within the input data, thereby exhibiting significant adaptability and resilience when confronted with nonlinear challenges and fluctuating operational environments. Recent research [18] confirms that deep learning architectures must integrate both global dependencies and local degradation characteristics. Xu et al. [19] further highlighted the limitations of conventional BP networks in dynamic scenarios, underscoring the need for mechanisms like adaptive attention [20] or temporal convolution [21]. Rout et al. [22] developed a data-driven method for evaluating the health status of LIBs, employing a variety of machine learning algorithms such as AdaBoost and Xgboost, ridge regression, random forest, artificial neural network (ANN), and long-short term memory network (LSTM). Among these approaches, LSTM outperforms in capturing underlying relationships within battery data sequences, showing obvious advantages in reducing error and improving accuracy compared with the other models. Poh et al. [23] propose advanced data-driven methods for estimating SOH of LIBs using health indicators and machine learning models, achieving high accuracy (average RMSE of 0.94%) and computational efficiency (15% CPU usage) in automotive applications. Gui et al. [24] design a hybrid architecture for SOH estimation for LIBs, integrating a CNN and a Transformer in parallel, so that local features and global dependencies in multimodal data can be learned cooperatively. By combining local and global feature extraction with a multi-information alignment strategy, the model achieved an RMSE below 0.017 and an R2 score of about 1.0 on multiple datasets. Zheng et al. [25] propose a data-driven joint estimation method for the SOH of LIBs using SVM, CNN, and LSTM models, achieving high accuracy with an SOH estimation RMSE below 0.81% and an MAE below 0.65%. And Su et al. [26] propose a hybrid method combining an equivalent circuit model, deep learning, and transfer learning for battery capacity estimation, achieving a maximum test error of 0.0941. Li et al. [27] design a CNN-based transfer learning method, using accelerated aging data for pre-training and 15% of normal-speed data for fine-tuning, achieving an RMSE below 0.32% and accuracy over 99.7% on SONY and FST batteries. Overall, deep learning technology has achieved remarkable results in extracting complex battery behavior from massive data. However, one of the existing limitations of these methods is their insufficient efficiency in learning key features.

To reliably estimate the SOH of LIBs under practical constraints, data-driven methods that leverage partial operational data have demonstrated significant potential. Recent advances in lithium-ion battery materials have shown that distinct cathode chemistries exhibit different aging pathways and degradation rates, which directly influence SOH evolution patterns [28]. The integration of advanced neural architectures, particularly those employing attention mechanisms to optimize the weight distribution of input health features, has been key to enhancing the characterization of battery degradation and achieving high estimation accuracy [29]. Arbaoui et al. [30] further advance the field by developing E-LSTM and CNN-LSTM models, emphasizing model explainability. They adopt Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) to interpret predictions, integrate pattern mining for anomaly detection on the MIT dataset, and realize a mean absolute error (MAE) of lower than 1%. For enhanced temporal modeling, Chu et al. [31] constructed a temporal convolutional network (TCN) integrated with an attention mechanism and refined it using Bayesian optimization. Their model, validated on a proprietary dataset, yielded a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) below 5.00%, demonstrating robust prediction capability across both high and low cycle numbers. Xiao et al. [32] propose a hybrid model that effectively learns the spatial information and long-term correlation of data by integrating CNN and a mask multi-head attention mechanism. The model performs best on the NASA and CALCE datasets, and its lowest RMSE and SDE values confirm its generalization and robustness. Zhao et al. [33] implemented a standard Transformer network, employing a rigorous feature selection process based on Pearson correlation coefficients. This model, tested on the NASA dataset with selected charging features, attained an RMSE of 0.0290 and an MAE of 0.0258, underscoring the efficacy of attention-based architectures for sequence modeling. Rajasekaran et al. [34] propose a GAN-based model with a CNN-LSTM generator and triple-attention ESN discriminator. By testing on NASA datasets, the model achieves an MAE as low as 0.0036 and an RMSE below 0.0213. Mchara et al. [35] develop a CNN-BiLSTM model for SOH estimation, using LSTM layers and a convolutional layer enhanced with an attention mechanism. Evaluated on NASA batteries, the model achieves an MAPE as low as 0.0031 and an RMSE below 0.0041. Geng et al. [36] design an interpretable deep learning framework with a multi-head attention LSTM, optimized with the Sparrow Search Algorithm and DeepSHAP for feature analysis. The model achieves an RMSE below 5% and an MAPE under 3% in NASA, CALCE, and PolyU datasets. Wang et al. [37] present a joint SOH estimation method using CNN-GRU for SOH. By testing under 1C cycling at 10 °C and 25 °C, the model achieves an RMSE below 1% for SOH. However, Chen et al. [38] reveal that neglecting cross-channel interactions in Transformers underutilizes sensor data. Du et al. [39] also emphasize that battery inconsistency in series-connected packs introduces overfitting risks, aligning with our dual-channel attention design. Collectively, these studies underscore a clear trend: the integration of attention mechanisms and specialized network designs is pivotal for achieving precise, robust, and interpretable battery SOH estimation. Despite these advances, few architectures jointly address (i) multi-model robustness via bagging [40], (ii) cross-channel coupling [41], and (iii) lightweight deployment [42]. This gap motivates our Bagging-PiFormer framework.

Although significant progress has been made in the accuracy of battery health status prediction in existing research, these achievements have not been fully validated on extensive battery data. The charging battery system is affected by multiple factors, such as charging rates, voltage changes, cycle times, material properties, and chemical composition. These factors often have complex temporal correlations that have a comprehensive effect on the health status of the battery. The current methods still lack sufficient understanding of the global structural features of data, making it difficult to comprehensively analyze these complex correlations.

Deep learning has shown great potential in state-of-health (SOH) estimation for lithium-ion batteries. However, its performance is still constrained by the limitations of model architecture, temporal dependency modeling, and feature fusion capability. In general, current data-driven SOH estimation methods still face the following four major challenges:

(1) Insufficient robustness of single-model architectures.

Most existing approaches rely on a single network structure, which tends to suffer from performance fluctuations and overfitting when facing diverse degradation stages, battery types, or noisy data, leading to unstable estimation results.

(2) Lack of effective utilization of channel coupling in conventional Transformer structures.

During the charging process, voltage and current signals exhibit strong interdependence. However, standard Transformer models primarily capture sequential correlations while neglecting cross-channel interactions, resulting in incomplete extraction of degradation features.

(3) Limited sensitivity of attention mechanisms to local temporal features.

Although attention mechanisms are effective for capturing long-range dependencies, they often fail to recognize local short-term patterns, such as voltage spikes or current pulses, which are critical indicators of degradation behavior in charging curves.

(4) Gradient attenuation and improper activation design in deep layers.

Transformer-based architectures are prone to gradient vanishing or feature distribution drift when deeply stacked. Moreover, since SOH is a continuous regression variable, the use of nonlinear activation functions in the output layer may constrain the output range and reduce estimation accuracy.

To address the above challenges, we propose a Bagging-PiFormer framework, an SOH estimation model based on ensemble learning, and an improved Transformer architecture. The proposed method integrates multi-model bagging, cross-channel attention fusion, and local convolutional feature extraction to achieve accurate and robust SOH estimation from both global and local perspectives. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

(1) Bagging-PiFormer ensemble framework:

A bagging-based ensemble architecture is developed, where multiple independent PiFormer models are trained in parallel, and their results are averaged to enhance robustness and generalization while reducing overfitting risk.

(2) Cross-channel attention mechanism:

A dual-channel attention module is designed within each PiFormer layer to model the bidirectional dependencies between voltage and current features, enabling dynamic interaction and effective fusion of cross-channel information.

(3) Local convolutional feed-forward network (LocalConvFFN):

A local convolutional module is introduced after the attention layer to extract short-term temporal degradation patterns through deep convolution and SiLU activation, complementing the attention mechanism’s ability to model long-range dependencies.

(4) Deep normalization and linear output design:

Residual connections and layer normalization are employed to stabilize feature distribution in deep layers, while a purely linear output head is used to regress the continuous SOH value, avoiding unnecessary activation constraints and improving estimation precision.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the dataset and the multi-channel physical feature extension technique. Section 3 details the cross-channel attention network. Section 4 presents experiments conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed methods, and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Dataset and Multi-Channel Physical Feature Extension

To simulate the real operating conditions of LIBs, two groups of experiments were conducted following the CLTC-P protocol, covering different charging conditions and battery aging status, resulting in the creation of Datasets A and B, respectively. To test the generalization performance of the model, this study also introduces Dataset C, which includes 124 A123 APR18650M1A lithium-ion cells tested within a forced convection chamber. These three datasets were then used to comprehensively evaluate the proposed method. All cycling experiments for Datasets A and B were performed using a Neware BTS-5V12A battery testing system (Neware Technology Limited Company, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China), ensuring a voltage and current measurement accuracy of 0.05%. All measurements and tester control for Datasets A and B were carried out using the BTSDA software (version 7.6.0, Neware Technology Limited Company). Dataset C is a publicly available dataset and therefore does not involve in-house testing equipment or software [43].

2.1. Battery Datasets

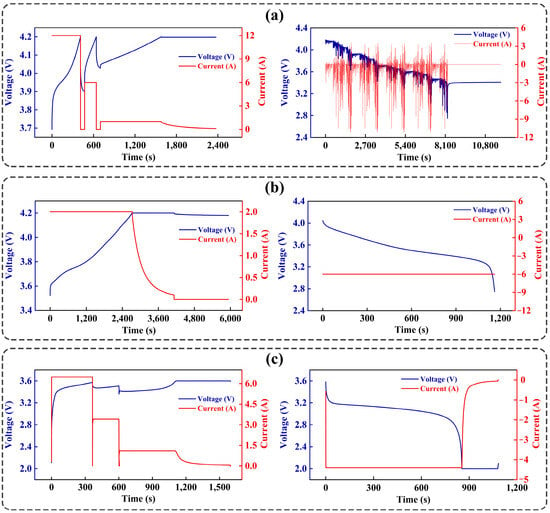

Dataset A: The test process of the INR 18650 battery is shown in Figure 1a. The process starts with a constant current charging: initially charging to 4.2 V at 6 C current, followed by a short rest, then charging to 4.2 V at 3 C current. After another one-minute rest, the standard 0.5 C constant-current constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging is performed, with a cut-off current of 0.05 C and a cut-off voltage of 4.2 V. Following a one-hour rest, the battery enters the discharge phase, continuously running the China light-duty test cycle for passenger cars (CLTC-P) cycles until the voltage drops to 2.7 V. The CLTC-P cycle is built based on big traffic data that includes low, medium, and high-speed intervals, lasting over 1800 s, and can effectively reflect real-world battery conditions. The capacity is measured every 50 cycles.

Figure 1.

Charging and discharging curves for (a) Dataset A, (b) Dataset B, and (c) Dataset C.

Dataset B: The steps of each aging cycle for the used Prospower ICR 18650 P battery are shown in Figure 1b. The process begins with a constant current charge to 4.2 V, followed by a 4.2 V constant voltage charge until the current drops to 0.1 C. Then, the battery discharges at a constant current rate of 3 C until reaching the cut-off voltage of 2.5 V. A one-hour resting interval is included between each cycle.

Dataset C: This dataset consists of 124 A123 APR18650M1A lithium-ion cells tested within a forced convection chamber maintained at 30 °C. Each cell underwent rapid-charging experiments employing either a one-step or two-step constant-current (CC) charging strategy, denoted as “C1(Q1)–C2,” where C1 and C2 correspond to the first and second constant-current phases, respectively, and Q1 represents the state of charge (SOC, %) at the transition between them. The first charging phase was conducted at rates between 5.5 C and 6.1 C, followed by a second phase at 4.4 C–4.7 C until the SOC reached 80%. Subsequently, the cells were charged under a 1 C CC–CV protocol with cutoff voltages of 3.6 V (upper) and 2.0 V (lower), according to manufacturer specifications.

In this study, the three datasets were obtained from independent aging experiments on commercial 18650 lithium-ion batteries with different chemistries. Dataset A corresponds to an INR 18650 cell (NMC-based), Dataset B to a Prospower ICR 18650P cell (LCO-based), and Dataset C to an A123 APR18650M1A cell (LFP-based). These battery types differ in nominal voltage, rated capacity, and expected degradation characteristics, providing a diverse evaluation benchmark for SOH estimation. For each dataset, multi-channel physical measurements—including voltage, current, temperature, and internal resistance—were recorded throughout the cycling process.

Table 1 summarizes the specifications of three datasets. The aging tests were conducted independently, and a pulse discharge method was used to emulate discharge patterns. All experiments were performed under temperature-controlled conditions. Partial constant current charging rates were 4 C for Dataset A and 5.5–6.1 C for Dataset B. SOH decay occurred over different time scales: Dataset A reached 80% capacity within one month, Dataset B over three months, and Dataset C over six months.

Table 1.

Related battery dataset specifications.

The SOH is defined as the actual capacity of the lithium-ion cell divided by its initial capacity, as shown in Equation (1):

where represents the current maximum discharge capacity (remaining capacity) and represents the initial capacity of the battery.

2.2. Health Indicators

Battery cycle life can be characterized by changes in related parameters such as terminal voltage, internal resistance, and capacity, which reflect the degree of degradation and health status. The key to achieving accurate SOH estimation is to effectively identify features from these parameters that reliably reflect the battery aging process.

Time-related features provide the most direct information about SOH variations. Deep learning models can learn complex nonlinear relationships between these temporal features and battery degradation from large datasets. However, for fast-charging batteries, the decay period is short. In Dataset B, SOH declines to 80% over six months, whereas in Datasets A and C, the same decay occurs in one month and three months, respectively. The number of cycles and the dataset size can limit the learning of the model, leading to the problem of vanishing gradients. This occurs when gradients of network parameters diminish toward zero during training, causing shallow layers to update faster while deeper layers learn slowly or stagnate, which impairs effective feature representation.

2.2.1. Feature Extraction Process

In the feature extraction process, we process two constant-current phases and one constant-current constant-voltage phase to implement feature extraction. Each phase is divided into a series of equally spaced voltage intervals, and samples are collected within these intervals. The sampling calculation is given as follows [44]:

where defines the voltage interval, is the maximum voltage difference within the current voltage segment, and is the sampling frequency. It is noted that the calculation of the sampling frequency directly impacts the subsequent feature extraction process.

Equations (3) and (4) determine the voltage range of the interval [44]:

where and represent the starting and ending voltages of the i-th voltage interval, respectively.

2.2.2. Time Variations Within Equal Voltage Intervals

The temporal differential during terminal charge/discharge cycles was disproportionately greater than that of initial cycles. Consequently, the inferable time difference within uniform voltage intervals serves as a direct indicator of inherent cell decay characteristics. Calculating these temporal variations enables finer-grained resolution of non-uniform aging patterns. To establish temporal boundaries for each interval, we derived the maximum and minimum voltage values cycle alongside their sampling frequencies. Subsequent feature extraction was then performed within these voltage-partitioned temporal blocks. The computation defining time variations across constant voltage intervals is expressed by the following formula:

where and represent the starting and ending times within the voltage interval, respectively, and is the time difference. This feature focuses on the temporal dynamics that occur during the charging period.

2.2.3. Cumulative Integral of the Voltage Variation

The voltage curve exhibits distinct upward and leftward displacements accompanied by altered slope characteristics. During initial charging phases, voltage demonstrates a gradual elevation that attenuates near process completion. Crucially, instantaneous voltage readings alone provide insufficient battery state characterization.

The cumulative integral methodology addresses this limitation by aggregating temporal voltage differentials, thereby amplifying minor fluctuations into discernible patterns that more accurately capture cell behavior. Comparative analysis shows that the terminal cycle’s cumulative integral is positioned superiorly and sinistrally to the initial cycle’s profile with marked magnitude deviation. Within this framework, Ei represents the energy input during charging, defined as the cumulative integral of voltage across constant-voltage intervals between start and end times, minus the product of instantaneous voltage and temporal differential:

where is the voltage, and the initial point and endpoint are determined by the time interval blocks of the first cycle.

2.2.4. Horizontal Value of the Slope Peak

During deep learning training, the accumulation of errors and noise amplification caused by integration operations can lead to gradient explosion, manifested as a sharp increase in network parameter gradients, uncontrolled weight updates, and ineffective representation. To address this issue, it is noticed that the peak position of the charging process continues to shift to the right with cyclic aging. This stable trend suggests that peak voltage (i.e., horizontal position) is a more reliable alternative feature than problematic area or peak height data. The specific calculation is as follows:

where and V are the capacity and voltage, respectively. k and k + 1 are time steps, and the variable is used to quantify the horizontal value of the maximum slope of the battery voltage change curve, representing the maximum voltage increase rate during the charging process.

2.2.5. Second-Order Differential Integral Feature

The second-order differential integral feature is extracted to quantitatively characterize the subtle curvature changes in the voltage–capacity curve. This feature serves as a highly sensitive indicator of degradation mechanisms such as lithium plating and solid electrolyte interphase growth. By integrating the second-order derivative, the feature captures the cumulative effect of these electrochemical shifts, providing a robust and noise-resistant metric that correlates strongly with capacity fade and internal resistance increase, making it a powerful predictor for state-of-health estimation. The specific calculation is as follows:

2.2.6. Total Charge Change Through the Circuit

In the constant current CC-CV charging process, under constant current charging or fast charging strategies, the charging capacity curve shows significant differences due to differences in current rate. These differences reflect the variation in the battery’s available capacity over time and capture the actual change in its ability to store charge during charging and discharging. As the number of batteries used increases and the degree of aging intensifies, their effective capacity gradually declines, amplifying differences in charging capacity. By multiplying the difference in charging capacity at each stage by the corresponding current, the change in charge within a specific voltage range can be quantified, providing deeper insights into the battery’s charging behavior. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

The product of the current and capacity difference in this stage defines the energy increment obtained by the battery during the charging interval, corresponding to the total charge passing through the circuit during this process.

Data from the target lithium-ion battery is acquired for feature extraction, transforming the raw measurements into a learnable tensor. For the time-sequential triplet sequence recorded from the processed data, a physically inspired feature expansion is performed based on the three original channels. To ensure that these heterogeneous channels share the same dimension and possess differentiable learning properties in subsequent deep networks, a trainable linear mapping is introduced. Each sampling point is transformed and subjected to layer normalization to obtain a token representation.

The final feature vector includes temporal features, voltage integral features, capacity-current features, second-order derivative integral features, and peak voltage features:

and the input tensor is designed considering :

The feature extraction procedure used in this work follows widely validated practices in battery SOH modeling. Prior studies have shown that degradation-sensitive indicators, such as voltage–current progression patterns, transition-region behaviors, curve-shape descriptors, and cumulative aging trends, provide strong predictive value for SOH estimation. Representative works include impedance-guided feature selection [45], optimization-based or statistical feature screening strategies [46,47], SHAP-based explainable feature ranking [48], and noise-robust feature refinement methods [49]. Moreover, our previous publications have applied SHAP-based interpretability analysis [50] and developed feature-selection algorithms that were peer-reviewed and experimentally validated [44]. Together, these works support the empirical and mechanistic validity of the feature set adopted in this study.

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Normalization

To ensure stable network training and consistent metric computation, all input features were subjected to Min–Max normalization during preprocessing. For each battery cell, a separate scaler was fitted using only its training cycles, and all corresponding validation and test cycles were transformed using the same scaler to avoid data leakage. Each feature value was mapped into the [0, 1] range as follows:

This scaling removed the influence of heterogeneous physical units among voltage-, current-, and time-related indicators, thereby improving model convergence and robustness.

The SOH labels were retained in their original physical range (typically 0.80–1.00), but underwent minor smoothing via a moving-average operation to suppress measurement noise. No normalization was applied to SOH during training; the model directly regressed the physical SOH value. For visualization and comparison, all predicted SOH values were multiplied by 100 during evaluation to express the results in percentages, following common practice in battery health studies. Importantly, metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and R2 were calculated strictly on the restored physical-scale SOH values.

3. Bagging-PiFormer Model Architecture Design

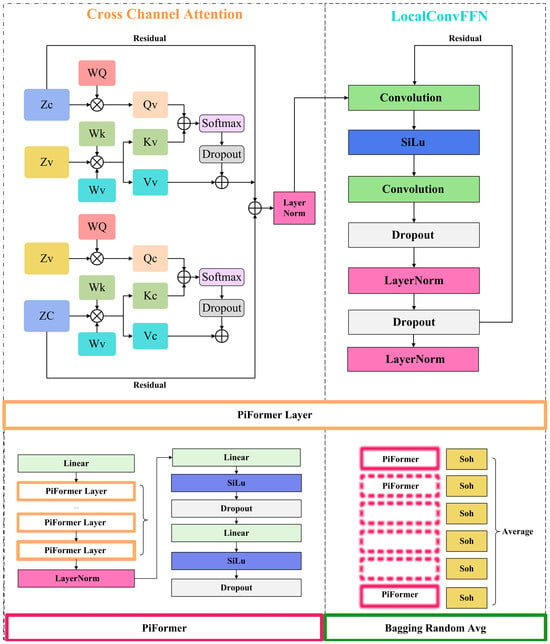

The proposed PiFormer model is a bidirectional interaction framework, which allows the voltage and current features to mutually enhance each other via separate Q, K, and V projections.

Architecturally, the model was composed of N stackable layers of lightweight Transformer blocks connected in series. Each layer adheres to the sequence of cross-channel attention, LocalConvFFN, and residual normalization, while incorporating specialized strategies tailored for multi-physics battery data within each sub-layer. Let denote the sequence tensor entering the l-th layer.

3.1. Cross-Channel Attention

The voltage channel from is linearly projected as the Query matrix . The current and voltage channels are concatenated along the feature dimension and then jointly projected as keys and values:

where denotes vector concatenation. The motivation is the electrochemical principle of “potential first”: most decay indicators manifest first in the voltage curve, while the current-voltage coupling provides the mechanistic information causing these indicators. The output of single-head attention is as follows:

The PiFormer employs h heads in parallel, whose results are concatenated and projected back to the model width via .

3.2. Bagging Strategy and Ensemble Construction

To enhance prediction stability and reduce variance, the Bagging-PiFormer framework constructs an ensemble of multiple PiFormer sub-models. Depending on the available computational resources, we train 10, 12, or 15 sub-models, each initialized with an independent random seed. Although explicit bootstrap sampling is not applied to the training data, the diversity introduced by randomized initialization provides a similar effect—each sub-model learns a slightly different mapping, reflecting the core idea of classical bagging: introducing randomness, training models independently, and aggregating their predictions.

After all sub-models are trained, their SOH predictions are stacked along a new dimension and averaged to obtain the final output:

where M ∈ {10, 12, 15} is the ensemble size. Since bootstrap sampling is not used, out-of-bag (OOB) estimates are not applicable. However, the mean and variance of the ensemble predictions naturally allow for estimation of 95% confidence intervals when required.

3.3. Local Convolutional Feed-Forward Network (LocalConvFFN)

Following the attention mechanism, a depthwise-separable convolution feed-forward module (DSF) is designed. First, a depthwise convolution with a kernel size of 3 is applied independently to each channel. The result is activated by the SiLU activation function and used as a gating factor, which then undergoes a Hadamard product with a 1 × 1 pointwise convolution :

where is the SiLU activation function, is the element function product. This design retains the advantage of convolutions in extracting local morphological features (e.g., “micro-discharge platforms”) while reducing parameters to about 1/4 of a traditional feed-forward network.

Pre-norm residual structure: The input is first passed through LayerNorm, then processed by the attention or DSF module, and finally added to the original input. This arrangement promotes gradient stability in deep networks. During training, dropout is applied after all projection matrices to suppress overfitting, and is removed during inference to save clock cycles. The recurrence is formulated as follows:

After N iterations, the resulting is the final hidden tensor, encapsulating Long-range and Short-range Coupling Information of I-V signals and local degradation features. To obtain a cycle-level global representation, average pooling is applied along the time dimension:

where the subscript n denotes the n-th cycle sample. Two linear output heads are then used:

where the output head uses a purely linear projection to regress the continuous SOH value, without any activation function.

As shown in Figure 2, the model implements an end-to-end framework for battery SOH prediction based on the Bagging-random-Avg algorithm. Input features propagate through the Bagging framework, which distributes them to each PiFormer. Each PiFormer processes features via an embedding layer, followed by multiple PiFormer layers—each incorporating a cross-channel attention mechanism and a LocalConvFFN. After layer normalization, an output head generates individual predictions. These predictions are averaged to produce the final output.

Figure 2.

Model structure diagram.

3.4. Training and Inference Procedure (Pseudocode)

The overall training and inference process of Bagging-PiFormer is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Training and Inference Procedure of Bagging-PiFormer | ||

| Data: Battery sequences from training cells; input window L; ensemble size M. Result: Final SOH prediction ŷ. | ||

| 1 | Initialize global seed and model hyperparameters | |

| 2 | Generate sliding-window sequences from training cells | |

| 3 | Normalize features using per-cell MinMax scaling | |

| 4 | Split data into training and validation sets (80%/20%) | |

| 5 | for m = 1 to M do | |

| 6 | Initialize PiFormer sub-model with random seed m | |

| 7 | Train model with HybridLoss and early stopping | |

| 8 | Save the best checkpoint of sub-model m | |

| 9 | end for | |

| 10 | for each test sequence do | |

| 11 | Obtain M sub-model predictions {ŷ1, …, ŷₘ} | |

| 12 | Aggregate outputs by mean: ŷ = (1/M) Σ ŷᵢ | |

| 13 | end for | |

4. Experimental Results and Discussions

This study used six performance indicators to systematically evaluate the model, including mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), coefficient of determination (R2), and maximum error (MAXE). The calculation formulas are as follows:

The above equation includes symbols where and are true values, and are predicted values, is the mean of the true values, and is the sample size.

The computation was performed on an experimental platform comprising an Intel(R) Xeon processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with two CPUs, 128-GB memory, and an NVIDIA RTX-4090D-24G GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.1. Data Splitting and Experimental Protocol

Each dataset follows a consistent train–validation–test partitioning strategy. Datasets A and B contain 7 battery cells each, while Dataset C contains 12 cells (details in Table 1). For each dataset, the first five cells (indices 0–4) are used to construct the training set. A sliding window of length 24 is applied to generate input–output pairs from each cell, and 20% of the resulting sequences are randomly separated as the validation set. The remaining two cells are reserved exclusively for testing:

- Dataset A: Test Set 1 = B104; Test Set 2 = B107;

- Dataset B: Test Set 1 = XQ-14; Test Set 2 = XQ-17;

- Dataset C: Test Set 1 = B204; Test Set 2 = B211.

A global random seed (seed = 0) is used for all random operations, including numpy.random, PyTorch CPU/GPU generators, CUDA kernels, data shuffling, and train/validation splitting. Deterministic CUDA settings (torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True) are also enabled to guarantee reproducibility. All models were implemented using PyTorch 2.2.0 (https://pytorch.org).

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, we perform a grid search over 72 hyperparameter configurations, combining the following:

- Three ensemble sizes (10, 12, 15 models);

- Four batch sizes (16, 32, 64, 128);

- Six learning rates (5 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−4).

Each configuration is trained for 300 epochs with early stopping (patience = 50). This results in 72 independent runs per dataset, each evaluated on both test cells, multiple noise-perturbed robustness scenarios (50 mV, 100 mV, 150 mV), and all ablation settings. All experiment results and hyperparameter configurations are automatically logged and saved for reproducibility.

4.2. Comparative Experiment

In the comparison experiment, we compared the proposed model with existing technologies such as Transformer, CNN-LSTM, and GCN-BiLSTM. Six sets of battery data were used as training groups, while B104 and B107, B204 and B211, and XQ-14 and XQ-14 were assigned as testing groups, respectively. All models use the feature subset obtained from Section 2.2 as input.

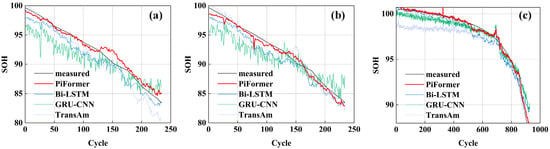

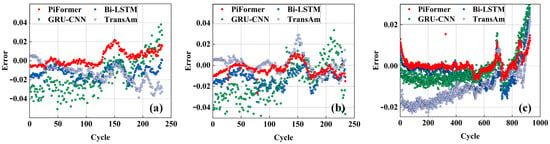

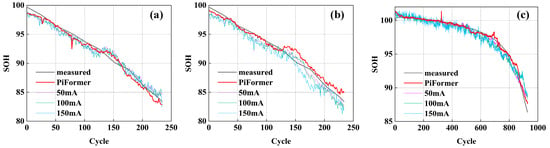

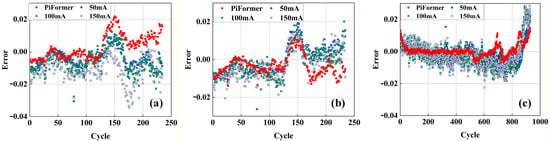

The evaluation index data for the SOH estimation results of different models are shown in Table 2. Figure 3 presents the SOH estimation performance of different models, while Figure 4 shows the corresponding error distributions. A comprehensive analysis shows that the model proposed herein is significantly superior to other comparative models in all error indicators. Specifically, the R2 values of the model generally approach or exceed 0.95, demonstrating strong interpretability and data-fitting performance. Regarding the MAXE value, the proposed model consistently achieves the lowest, minimizing the maximum prediction error and reflecting superior stability.

Table 2.

Results analysis of the comparative experiment.

Figure 3.

SOH estimation from different modes: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-14 and XQ-17); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

Figure 4.

SOH estimation errors from different modes: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-14 and XQ-17); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

As depicted, the Transformer and CNN-LSTM methods perform poorly in most tests, particularly under complex changes. This may be due to their weaker modeling ability in long-range dependencies compared to the GCN-BiLSTM model. Specifically, the MSE and MAXE of CNN-LSTM reach 9.790759 and 4.734474, respectively, indicating limited robustness to outliers. However, Transformer exhibits high values in most error metrics, including MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and MAXE, with significant prediction bias. The GCN-BiLSTM model outperforms CNN-LSTM, but does not surpass the proposed PiFormer method across all indicators. In the B204 and XQ-17 test cases, the R2 value of the GCN-BiLSTM model is relatively low, which reflects its insufficient explanatory performance under specific operating conditions.

Overall, the proposed PiFormer model outperforms when facing complex operating conditions and different types of battery data. This model not only performs well in statistical error indicators but also has significant advantages in maintaining prediction accuracy and stability. In contrast, although other comparative methods perform fairly well in some test scenarios, their overall performance in multi-scenario environments is still insufficient, and their stability is generally inferior to the proposed model.

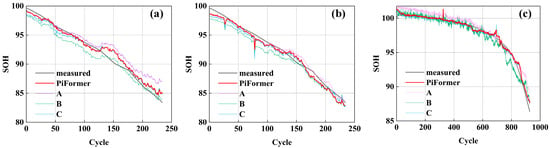

4.3. Noise Experiment

This experiment investigates how noise levels influence the PiFormer model’s SOH estimation accuracy. Noises with varying amplitudes (50 mV, 100 mV, and 150 mV) are introduced into the data to simulate uncertainties under real-world battery operating conditions, enabling a systematic evaluation of the stability and robustness of the PiFormer model in the presence of noise. The statistical results of the SOH estimation across different models are shown in Table 3, with Figure 5 presenting the SOH estimation performance of different models, and Figure 6 showing the corresponding errors. The results demonstrate that, although increasing noise levels degrade predictive performance, the proposed model maintains a relatively high level of prediction accuracy for the batteries’ SOH. Specifically, at noise levels of 50, 100, and 150 mV, the model exhibits prominent robustness, with predictive capability remaining largely unaffected despite escalating noise interference. These results confirm that the model has strong robustness when processing data with varying noise interference.

Table 3.

Results analysis of the noise experiment.

Figure 5.

SOH estimation results with different noises: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-17 and XQ-14); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

Figure 6.

SOH estimation errors with different noises: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-14 and XQ-17); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

These noise experiments further validated the effectiveness and adaptivity of the model, indicating that it can effectively cope with various noise interferences encountered in practical applications. The results not only confirm the technical advantages of the model but also highlight its potential for application in challenging scenarios where data quality is susceptible to multiple factors.

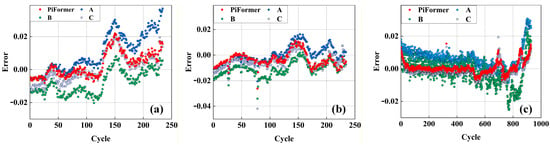

4.4. Ablation Experiment

Ablation experiments were carried out to analyze and validate the advantages of the proposed PiFormer model in estimating the SOH of LIBs. The proposed models removing BaggingRandom-Avg, LSTM-attention, and LocalConvFFN models are represented by A, B, and C, respectively, and validated using Dataset A. The proposed PiFormer model is used to evaluate the SOH. Figure 7 shows the estimation results, Figure 8 shows the estimation errors, and Table 4 shows the evaluation metric values.

Figure 7.

SOH estimation in ablation experiments: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-14 and XQ-17); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

Figure 8.

SOH estimation error in ablation experiments: (a) Dataset A (B104 and B107); (b) Dataset B (XQ-14 and XQ-17); and (c) Dataset C (B204 and B211).

Table 4.

Results analysis of the ablation experiment.

Removing the BaggingRandom-Avg module from PiFormer resulted in only a slight decrease in R2 value, but other performance indicators showed significant fluctuations. For example, in the B104 dataset, MSE and RMSE increased from 0.703395 and 0.838686 to 2.751545 and 1.658778, respectively. This indicates that the BaggingRandom-Avg ensemble learning strategy is effective in improving the robustness of the model.

After removing the cross-channel attention module from the PiFormer model, all evaluation indicators remain within a reasonable range; however, MSE, RMSE, and MAE show significant increases. For instance, in the XQ-17 battery, the MSE value increased by 48.95%. This result indicates that the cross-channel attention mechanism plays an irreplaceable role in the PiFormer architecture. This module effectively combines residual structure and attention mechanism to better capture the cross-channel dependencies and key features in sequence data, thereby significantly improving the model’s ability to characterize battery status.

Removing the LocalConvFFN module from the PiFormer model would result in all six evaluation metrics exceeding the reasonable range. The results demonstrate that the module can effectively extract key information from battery features through multi-layer convolution and average pooling operations. The convolution module plays an important role in constructing rich feature representations and improving overall performance.

These experiments analyzed the functional characteristics of each core component of PiFormer and verified their unique roles in improving model performance. These findings not only consolidate PiFormer’s advantages in estimating the SOH of LIBs but also provide a reliable basis for optimizing battery management and maintenance strategies.

To evaluate the computational efficiency of Bagging-PiFormer, we report the training time, inference latency, and parameter scale of the ensemble. On a single NVIDIA GPU, the average training time per epoch is 88.14 s for both Test 1 and Test 2 configurations. The inference latency is 34.29 s in Test 1 and 33.87 s in Test 2. The total number of trainable parameters increases with the ensemble size: 17.04 million parameters for 10 models, 20.45 million for 12 models, and 25.56 million for 15 models. GPU memory consumption remained within practical limits during all experiments. These results indicate that, despite the ensemble structure, Bagging-PiFormer achieves a reasonable balance between prediction accuracy and computational cost.

The performance improvements of Bagging-PiFormer are consistent across all datasets, evaluation metrics, hyperparameter configurations, and noise perturbation settings, demonstrating strong practical statistical significance.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a Bagging-PiFormer model for lithium-ion battery SOH estimation that is designed to overcome the limitations of single-model architectures and insufficient feature coupling in existing deep-learning approaches. The proposed framework employs an ensemble of improved Transformer-based PiFormer models to enhance robustness, while each PiFormer incorporates a cross-channel attention mechanism and a LocalConvFFN to achieve dynamic voltage–current interaction modeling and local temporal feature extraction.

Comprehensive experiments—including comparative analyses, noise-interference testing, and ablation studies—demonstrated that the Bagging-PiFormer consistently achieved the highest estimation accuracy and stability across multiple battery datasets. The model maintained R2 values above 0.963 and MAXE below 1.829 under various conditions, confirming its strong resistance to noise and outstanding generalization across different cell types.

Future research will incorporate SHAP-based feature attribution, attention-map visualization, and physical–electrochemical interpretability analysis to further elucidate how Bagging-PiFormer associates specific temporal regions with degradation mechanisms such as lithium inventory loss, impedance growth, and voltage-plateau evolution. These extensions will enhance the transparency and mechanistic insight of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

S.W.: methodology, validation, writing—review and editing, resources, and funding acquisition. J.Z.: validation, data curation, software, and writing—original draft. W.T.: conceptualization, validation, software, and writing—review and editing. X.L.: software and validation. Y.F.: investigation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported partially by the Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (252102211021, 252102211019, 252102241042), Guangdong Provincial Special Innovation Project for General Universities (Natural Sciences) of Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (2024KTSCX145), and 2024 Tertiary Education Scientific research project of Guangzhou Municipal Education Bureau (2024312086).

Data Availability Statement

The experiments of this study are ongoing. If you need our data for relevant research, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that may appear to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hasan, M.M.; Haque, R.; Jahirul, M.I.; Rasul, M.G.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Hassan, N.M.S.; Mofijur, M. Advancing energy storage: The future trajectory of lithium-ion battery technologies. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Luo, P.; Zheng, H.; Lyu, Z. Sulfur-doped graphene promoted Li4Ti5O12@C nanocrystals for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908, 164599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, R.; Wei, Y. A review of state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion battery packs. J. Energy Storage 2025, 118, 116078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahwiadi, M.; Wang, W. Battery Health Monitoring and Remaining Useful Life Prediction Techniques: A Review of Technologies. Batteries 2025, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garse, K.; Bairwa, K.; Mali, R.; Phule, S.; Navale, S. Performance Evaluation Of State Estimation Algorithms For Li Ion Battery State Of Health. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 2209–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgener, J.; Ouwerkerk, J.; Haberschusz, D.; Bors, J.; Woerner, P.; Mennekes, M.; Hildenbrand, F.; Hecht, C.; Kairies, K.; Wessels, O.; et al. Multi-year field measurements of home storage systems and their use in capacity estimation. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Han, J. Lithium-ion-battery state of health estimation based on coefficient of variation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2968, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Application of Attention-Based CNN-BiLSTM Model in Lithium-Ion Battery SOH Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference of Clean Energy and Electrical Engineering (ICCEEE), Changchun, China, 18–21 July 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Deng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lai, L.; Gong, G.; Tong, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Gong, M.; Yan, M.; et al. Lithium-Ion Battery State of Health Estimation Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention-FVIM Algorithm and Fusion of Multiple Health Features. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padder, S.G.; Ambulkar, J.; Banotra, A.; Modem, S.; Maheshwari, S.; Jayaramulu, K. Data-Driven Approaches for Estimation of EV Battery SoC and SoH: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 35048–35067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.Q.; Xu, B.; Chen, F.H.; Zhou, G. Predictive Modeling for Electric Vehicle Battery State of Health: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Energies 2025, 18, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Sah, B.; Mulpuri, S.K.; Barai, A.; Kumar, P. Develop a Versatile ECM Framework Capable of Accurately Representing Multiple Cell Types. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress & Exposition Asia (ECCE-Asia), Bengaluru, India, 11–14 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Li, Y.J.; Yao, Z.Q.; Liu, S.K.; Zhu, Y.H.; Wang, X.J.; Wang, J.; Zheng, C.M.; Sun, W.W. Research Advances on Lithium-Ion Batteries Calendar Life Prognostic Models. Carbon Neutralization 2025, 4, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renold, A.P.; Kathayat, N.S. Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Digital Twin Data-Driven Approaches in Battery Health Prediction of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 43984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Ji, C.; Dai, J.; Rao, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, W.; Romagnoli, J. Data-based health indicator extraction for battery SOH estimation via deep learning. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 109982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Xiang, D.; Cai, D.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z. Extraction of incipient fault features of rolling bearing based on CWSSMD and 1.5D-EDEO demodulation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Du, Y. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on MResNet-LSTM. Int. J. Acoust. Vib. 2024, 29, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Luo, B.; Chen, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Cao, Y.; Wang, C. The State of Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review of Health Indicators, Estimation Methods, Development Trends and Challenges. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Y. SOH estimation of lithium-ion battery under complex operating conditions based on BP neural network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2932, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; He, T.; Zhu, W.; Liao, Y.; Zeng, J.; Xu, Q.; Niu, Y. A lithium-ion battery SOH estimation method based on temporal pattern attention mechanism and CNN-LSTM model. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 122, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, B. Battery health prognosis using improved temporal convolutional network modeling. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.; Samal, S.K.; Gelmecha, D.J.; Mishra, S. Estimation of state of health for lithium-ion batteries using advanced data-driven techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, W.Q.T.; Xu, Y. Advanced Data-Driven Methods for Automotive Battery Health Prognostics. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, X.A.; Du, J.R.; Wang, Q.L.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, Y.H.; Zhao, J.H. Multi-modal data information alignment based SOH estimation for lithium-ion batteries using a local–global parallel CNN-Transformer Network. J. Energy Storage 2025, 129, 117178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Luo, X. Joint estimation of State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH) for lithium-ion batteries using Support Vector Machine (SVM), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM) models. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, W.; Mou, J.; Garg, A.; Gao, L.; Liu, J. A Hybrid Battery Equivalent Circuit Model, Deep Learning, and Transfer Learning for Battery State Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, J. CNN and transfer learning based online SOH estimation for lithium-ion battery. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 22–24 August 2020; pp. 5489–5494. [Google Scholar]

- Theodore, A.M. Promising cathode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries: A review. J. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Lin, H.; Yu, H.; Lai, Y.; Yang, Y. Battery state-of-health estimation based on random charge curve fitting and broad learning system with attention mechanism. J. Power Sources 2025, 636, 236544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaoui, S.; Samet, A.; Ayadi, A.; Mesbahi, T.; Boné, R. Data-driven strategy for state of health prediction and anomaly detection in lithium-ion batteries. Energy AI 2024, 17, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.C.; Wei, Z.C.; Yang, G.L.; Feng, Y.D.; Xing, Y.L. Prediction of the State of Health (SOH) of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles Based on Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) with Integrated Attention Mechanisms. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Electronics and Devices, Computational Science (ICEDCS), Marseille, France, 23–25 September 2024; pp. 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.P.; Fu, L.J.; Shang, C.Y.; Fan, Y.X.; Bao, X.Q.; Xu, X.H. A Lithium-Ion Battery State-of-Health Prediction Model Combining Convolutional Neural Network and Masked Multi-Head Attention Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 40, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Behdad, S. State of Health Estimation of Electric Vehicle Batteries Using Transformer-Based Neural Network. ASME J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2024, 146, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, E.; Venkatanarayanan, S. State-of-Health (SoH) prediction for electric vehicle battery systems using GAN-based models with triple attention mechanisms. J. Energy Storage 2025, 134, 118143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchara, W.; Khalfa, M.A.; Manai, L. Hybrid Deep Learning with Attention Mechanism based Health State Intelligent Diagnosis of Lithium-Ion Batteries. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD), Paris, France, 15–17 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Huang, X. Interpretable deep learning with uncertainty quantification for lithium-ion battery SOH estimation. Energy 2025, 335, 138027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ou, K.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.-X. A State-of-Charge and State-of-Health Joint Estimation Method of Lithium-Ion Battery Based on Temperature-Dependent Extended Kalman Filter and Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Y. Edge–cloud collaborative estimation lithium-ion battery SOH based on MEWOA-VMD and Transformer. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Song, Y.; Zeng, G.; Peng, Y.; Liu, D. Series-Connected Lithium-Ion Battery Packs’ Self-Adaptive SOH Estimation via Inconsistency Representation Optimization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3551413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, C.; Shao, K.; Tong, J.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. A SOH Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on CPA and CNN-KAN. Batteries 2025, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Jia, L.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, H. Cross-domain battery SOH and RUL estimation via Domain-Adaptive Transformer. Energy 2025, 20, 139288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Seo, Y.; Barde, S. Edge-compatible SOH estimation for Li-ion batteries via hybrid knowledge distillation and model compression. Energy 2025, 135, 118275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severson, K.A.; Attia, P.M.; Jin, N.; Perkins, N.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.H.; Aykol, M.; Herring, P.K.; Fraggedakis, D.; et al. Data-driven prediction of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Yan, C.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, G.; Ren, Z.; Li, S.; et al. A novel lithium-ion battery state-of-health estimation method for fast-charging scenarios based on an improved multi-feature extraction and bagging temporal attention network. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wei, F. State of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on impedance feature selection and improved support vector regression. Energy 2025, 326, 136135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Meng, J.; Amirat, Y.; Gao, F.; Benbouzid, M. Feature selection strategy optimization for lithium-ion battery state of health estimation under impedance uncertainties. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 101, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, S.; Kumar, B.; Mittal, A.P. Optimized XGBoost framework for RUL prediction of lithium-ion batteries using multi health indicators. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Wang, S. State-of-health rapid estimation for lithium-ion battery based on an interpretable stacking ensemble model with short-term voltage profiles. Energy 2023, 263, 126064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, Y.; Gao, X.; Xie, H.; Chen, S. Small-Sample Battery Capacity Prediction Using a Multi-Feature Transfer Learning Framework. Batteries 2025, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yan, C.; Wu, X.; Guan, Q.; Tan, X. An explainable state of health estimation method for sodium-ion batteries based on Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. J. Energy Storage 2025, 139, 118887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).