Abstract

Lanthanide-based single-molecule magnets are promising candidates for potential applications. Their magnetism is governed by ligand-field splittings, which may require up to 27 ligand-field parameters for accurate modeling. Determining these parameters reliably from measured data is a major challenge, for which machine learning approaches offer promising solutions. We provide an overview of these approaches and present our perspective on addressing the inverse problem relating experimental data to ligand-field parameters. Previously, a machine learning architecture combining a variational autoencoder (VAE) and an invertible neural network (INN) showed promise for analyzing temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility data. In this work, the VAE-INN model is extended through data augmentation to enhance its tolerance to common experimental inaccuracies. Focusing on second-order ligand-field parameters, diamagnetic and molar-mass errors are incorporated by augmenting the training dataset with experimentally motivated error distributions. Tests on simulated experimental susceptibility curves demonstrate substantially improved prediction accuracy and robustness when the distributions correspond to realistic error ranges. When applied to the experimental susceptibility curve of the complex , the augmented VAE–INN recovers ligand-field solutions consistent with least-squares benchmarks. The proposed data augmentation thus overcomes a key limitation, bringing the ML approach closer to practical use for higher-order ligand-field parameters.

1. Introduction

For the past three decades, single-molecule magnets (SMMs) have catalyzed significant scientific research. In addition to enabling the study of fundamental quantum magnetic phenomena, such as magnetic quantum tunneling or quantum interference effects [1,2,3,4,5,6], the sustained interest in SMMs also arises from their promising potential in technological applications, including magnetic memory, quantum computing, and spintronics [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Strong magnetic bistability and slow magnetic relaxation are crucial for practical applications, and research has thus increasingly shifted toward lanthanide-based SMMs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], where the unquenched orbital angular momentum generates large total angular momentum J and anisotropy splitting, resulting in a manifold of magnetic sublevels with well separated spin reversal pathways.

Compared to transition-metal SMMs, lanthanide-based SMMs pose a greater challenge for characterization. Their magnetic behavior depends critically on the splitting of the J multiplet by the surrounding ligand-field, which is commonly modeled by the Hamiltonian

where are Stevens operators (, ) [22,23]. The ligand-field environment is, however, often of low symmetry, which implies that all ligand-field parameters may contribute and therefore would have to be considered. In practice, the order of k is usually truncated at on the basis of first-order perturbation theory, although this limitation is somewhat arbitrary, as higher-order terms may not always be negligible [24]. Nevertheless, this still results in a staggering 27 ligand-field parameters, presenting a considerable challenge for both experiment and interpretation [17,25,26,27,28,29,30].

For instance, experimental data are rarely sufficiently informative to determine this many model parameters, and reduced models with fewer parameters must therefore be used, which naturally raises questions about the physical relevance of the selected parameters. The problem is particularly severe when analyzing magnetic susceptibility and magnetization measurements on powder samples, the most widely used experimental techniques, since the resulting data are generally feature-poor for lanthanide-based complexes. Experimental uncertainties, such as errors in sample mass or diamagnetic corrections, further complicate the situation. That is, the data analysis problem is massively overparameterized, and the traditional least-squares fitting may not converge, may strongly depend on the initial guess, may result in many almost equally good solutions, or may yield best-fit parameter sets of questionable physical relevance. Using machine learning (ML) tools for the purpose of determining magnetic parameters from such data emerges as an interesting alternative worth investigating.

In scientific research, ML has experienced explosive development in recent years, evolving from its early applications in particle physics to becoming a cornerstone of data analysis and property prediction across a wide range of disciplines. Its integration into research workflows has led directly to a number of high-profile breakthroughs. Most notably, Alphafold, a deep learning network developed by Google DeepMind, made monumental progress on the protein folding problem and established itself as the gold standard in protein structure prediction [31]. This work was the recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in chemistry. That same year, the Nobel Prize in Physics recognized foundational contributions to statistical learning models, specifically Hopfield networks and Boltzmann machines [32,33,34]. A significant transformation is also underway in materials science, where, e.g., ML models are increasingly being used as surrogates for density functional theory (DFT) or to accelerate DFT by approximating the typically expensive exchange correlation functional [35,36,37,38,39]. It has become increasingly evident that ML will be an indispensable tool in scientific research going forward.

Research in molecular magnetism has also begun to leverage the predictive capabilities of ML models. DFT is used to predict various properties of SMMs, such as magnetic exchange couplings and phonon frequencies, and has been a major entry point of ML in the field. For instance, neural network surrogates have recently been trained on DFT data to predict magnetic parameters, including axial magnetic anisotropy parameter D and the matrix [40,41]. In addition to being much faster, the approach has also been found to be significantly more accurate than routine DFT methods and, in fact, comparable in quality to Complete Active Space Self Consistent Field (CASSCF) ab initio techniques [41]. Similarly, an ML force-field surrogate was employed in place of DFT calculations of phonon frequencies to determine the spin relaxation times of single ion magnets [42,43]. Furthermore, Gaussian moments were used as molecular descriptors in neural networks to model the interatomic potentials of SMMs and thereby predict their thermally averaged magnetic anisotropy tensors [44]. Modeling the structure property relationships with ML models has also opened a new avenue towards the inverse design and discovery of magnetic molecules with desirable properties [45,46,47,48]. In particular, ML has been used to learn a structural property map from ab initio data and to explore structural configurations that maximize magnetic anisotropy [49]. The majority of these studies focus on 3D-based SMMs. Using ML to approximate first-principles calculations for lanthanide-based SMMs remains rare and is only recently being investigated [43]. This is for good reason, as the calculations are significantly more challenging in comparison. The strong spin-orbit coupling cannot be treated as a perturbation, and DFT functionals struggle to deliver accurate multiplets. Ab initio methods such as CASSCF perform much better, but are quite involved and yet to reach full predictive capability that can be regularly applied [26,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Essentially all of these works, especially those employing surrogate-type ML models, are concerned with forward problems, in which each input produces a unique output. That is, the problem can be represented by a mathematical function, making the mapping relatively straightforward. In contrast, the problem of determining model parameters from experimental data constitutes an inverse problem, where the relationship between inputs and outputs cannot be represented by a function, since a single input is generally related to two or more outputs (a one-to-many mapping). In other words, the function representing the forward problem is not invertible. Accordingly, inverse problems are typically far more difficult to solve, and very different ML methods are required. For the sake of precision, it is noted that the notions of (i) “forward” vs. “inverse” and (ii) “function” vs. “non-invertible” are not exactly synonymous; however, for the purposes of this work, the subtle distinctions can be disregarded, and the terms are used interchangeably.

ML models tackling inverse problems, such as mixture density networks or inverse neural networks (INNs), have recently been the subject of significant research [58,59,60,61,62,63], and ML is already gradually being incorporated into, e.g., X-ray and neutron scattering data analysis workflows [64,65,66,67,68,69]. In a recent work, some of us employed a probabilistic ML model, consisting of a variational autoencoder (VAE) for dimensionality reduction coupled with an INN for inverse mapping (VAE-INN in short), to analyze the magnetic susceptibility data of the butterfly-type compound [70], where = [(-OH)2(pmide)2(p-Me-PhCO2)6]·2MeCN (pmideH2 = N-(2-pyridylmethyl)-iminodiethanol) [71]. It is a suitable choice as a model compound: the magnetic interaction between the two magnetic ions () in this complex is negligible, and is diamagnetic. The observed magnetism thus arises solely from the splitting of the energy levels by the surrounding ligand field, and Equation (1) represents the appropriate magnetic model. This case study showed that an ML model can successfully learn a one-to-many mapping from magnetic susceptibility data to ligand-field parameters. Moreover, the ML approach was found to offer significant advantages over traditional least-squares fitting methods, exhibiting improved generalization and convergence and, in particular, greater robustness to detrimental experimental errors, such as inaccuracies in sample mass determination. The work thus provides encouraging evidence for the potential of ML to determine ligand-field parameters from magnetic data, but it also highlights the challenges that must be addressed before it can become a universally applicable tool. In addition to experimental errors, the construction of informative datasets and the avoidance of the curse of dimensionality were identified as particular challenges, which limited the ML model in Ref. [70] to no more than four ligand-field parameters.

In this work, we begin by offering general remarks on ML to help researchers in single-molecule magnetism avoid common misconceptions and better understand the terminology and concepts involved. These remarks will be framed in relation to traditional least-squares fitting, highlighting points of similarity where analogies can be drawn, and emphasizing key differences where they diverge. We then present our perspective on analyzing ligand-field parameters of SMMs using ML-based approaches. The general methodology is outlined and contrasted with ab initio and least-squares-based approaches, and particular attention is given to the challenges that remain. Finally, in the main part of the paper, we address the challenge posed by experimental errors. In particular, we demonstrate, using a controlled setting focusing on second-order ligand-field parameters, that augmenting the training dataset with artificially introduced experimental errors can significantly enhance the ML model’s ability to generalize. Through this data augmentation, the ML framework becomes more robust to inaccuracies in the measured data, effectively learning to discount spurious fluctuations while retaining sensitivity to the underlying ligand-field parameters. To illustrate this, the VAE-INN is applied to simulated magnetic susceptibility data and to the magnetic susceptibility of .

1.1. Machine Learning Basics

This section does not attempt to provide an introduction to ML, as many excellent textbooks and review articles already fulfill that role [72,73,74,75,76,77]. Instead, it aims to clarify a few points that may appear confusing or misleading to novices in the field. Given the vast array of methods and tools in ML, the following cannot claim to be comprehensive and is certainly simplified. It is tailored to the context of this manuscript, but should nevertheless provide a sufficiently broad perspective on some general aspects.

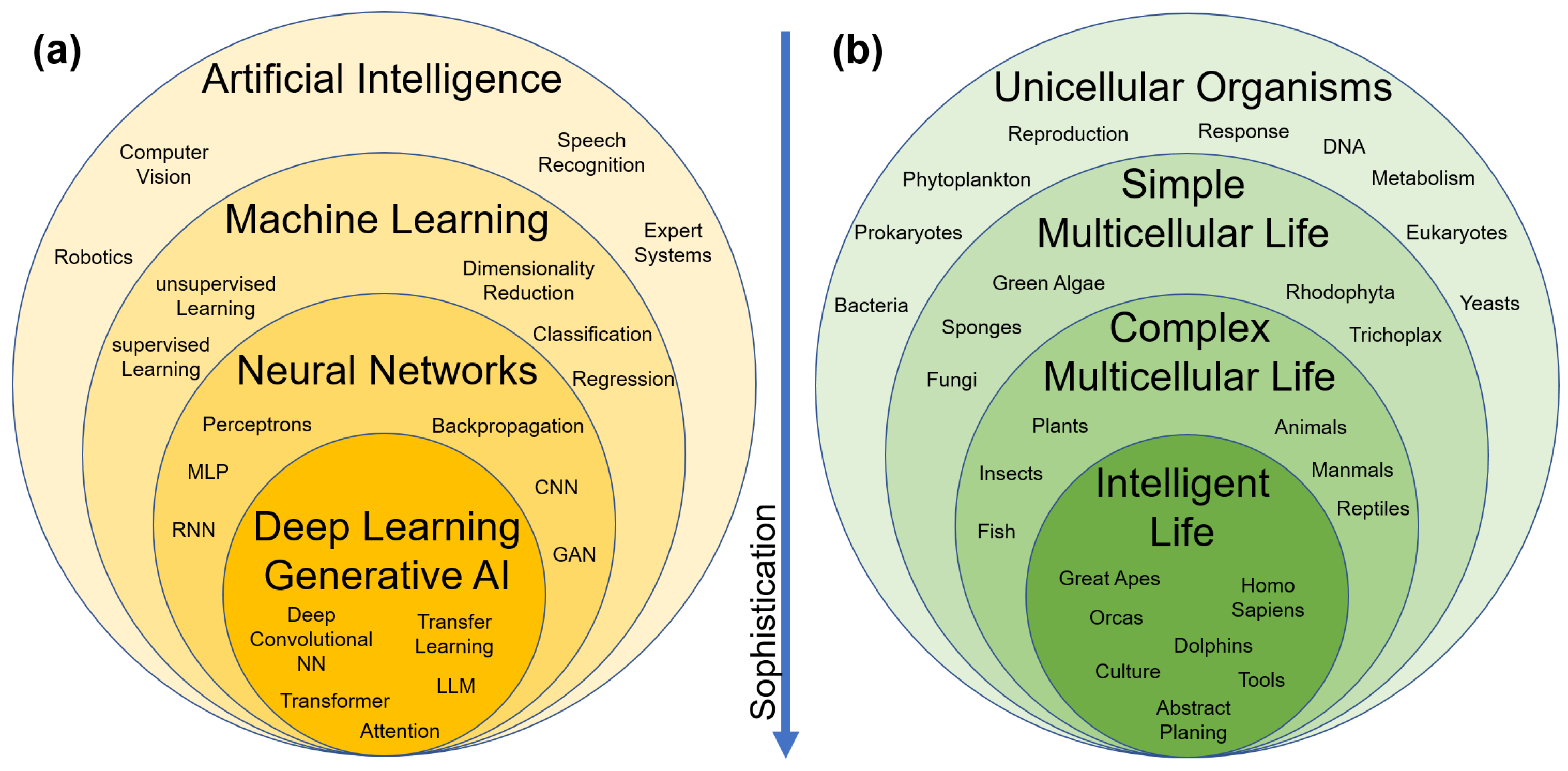

First, the conceptual scope of the terms artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) is discussed. Figure 1a presents a widely used heuristic classification scheme in terms of an onion model, in which each inner layer represents a subset of increasingly sophisticated and capable algorithms. The point to observe is that AI, by common definition, serves as the umbrella term [78,79]. It thus also encompasses a broad class of algorithms, which are rather traditional statistical methods and which intuitively would not be perceived as particularly “intelligent”. In terms of increasing algorithmic complexity and sophistication, the hierarchy proceeds as: AI → ML → DL. This structure is in marked contrast to the common-sense classification of natural life forms. For comparison, Figure 1b sketches a classification of natural organisms by complexity (the schematic does not follow formal biological taxonomy; it is intended purely for pedagogical purposes). The terms AI and “natural intelligence” are not corresponding pairs; rather, they lie at opposite ends of the complexity scale and are better regarded as antonyms.

Figure 1.

(a) Sketch of a common heuristic classification of the algorithms underlying artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), neural networks (NNs), and deep learning (DL). MLP: multilayer perceptron, CNN: convolutional neural network, RNN: recurrent neural network, GAN: generative adversarial network, LLM: large language model. (b) Sketch of a common-sense classification of natural life forms. Neither schematic follows formal taxonomy, but both are intended purely for pedagogical purposes.

Next, while this is an oversimplification, much of AI and its sub-components can be demystified by framing them as vastly complex fitting functions. The conceptual backbone of ML and traditional numerical fitting is, in fact, similar, and it is instructive to compare the two approaches, both to highlight parallels and to emphasize the significant differences between them. We will see that while they both model a function by means of minimizing an error, the fundamental difference lies in complexity, i.e., the number of parameters in the ML approach and the size of the dataset. In what follows, we focus on neural networks (NNs), which represent a broad and flexible class of ML models.

In numerical fitting, a function is defined that describes the relation between the independent variable x and the dependent variable y, where denotes the model parameters. In our setting, f represents the ligand-field Hamiltonian and quantum statistical equations to compute thermal observables, the dependent variable y is the temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility , the independent variable x is the temperature T, and the model parameters consist of the ligand-field anisotropy parameters , , and so on (denoted as in short). In the process of fitting a given magnetic susceptibility curve y, the parameters are iteratively adjusted to minimize the least-squares error between the measured data and the model output (n denotes the number of data points in the curve, and i indexes each data point). Each iteration requires evaluating f, which in our case entails diagonalizing the Hamiltonian and potentially other quantities, such as derivatives, depending on the fitting algorithm in use [80].

NNs also define a function , but the assignment of x and is very different. The output y remains the magnetic susceptibility curve, but the input x now corresponds to a set of ligand-field parameters, while corresponds to a large number of tunable NN parameters (also called “weights”). These tunable parameters are not physically interpretable, giving rise to the familiar “black box” character of NNs. However, their flexibility makes NNs universal function approximators [81], meaning that although the functional form of f is not (and usually cannot be) specified explicitly, the NN can approximate any arbitrary function. Using NNs, f becomes a complex mapping from the input space of ligand-field parameters x to the output space of possible magnetic susceptibility curves y. The “training” of the network involves iteratively adjusting the NN parameters to minimize the error between input and predicted curves y and , respectively, similar to a fitting procedure. However, the error is minimized not only for a specific, single input curve, but across a large set of curves which, together with their corresponding ligand-field parameters, form the training dataset. Assembling informative datasets is thus a critical task in ML. In the ML context, the error measure is usually referred to as the “loss function”. Whereas the least-squares error is a possible choice (in ML, usually called mean squared error, MSE), other loss functions are usually more suitable depending on the task. For instance, regularization by incorporating the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence and other terms is commonly employed [72,75,82]. Since the mapping encoded in is learned over a domain of ligand-field parameters, the trained ML model possesses predictive capability within that domain. New, previously unseen ligand-field parameter sets x can be input to obtain corresponding predictions of . Furthermore, these predictions can be generated significantly faster than diagonalizing the Hamiltonian.

The ML model described so far serves as a surrogate for the Hamiltonian model, generating susceptibility curves from ligand-field parameters. However, as f in the ML context can be any mapping, one might instead consider training the ML model to approximate the inverse mapping (it is recalled that in this setting x represents the ligand-field parameters). Such an ML model would directly predict ligand-field parameters from susceptibility curves, without requiring iterative diagonalization of the Hamiltonian as in the fitting approach. However, due to the overparameterized nature of the problem, where multiple ligand-field parameter sets can describe the susceptibility data to equivalent accuracy, the inverse to f is not single-valued but instead a one-to-many mapping. That is, is, in fact, not a mathematical function. The one-to-many mapping must instead be represented by a function into probability distributions such that , where is the probability distribution of the possible parameter sets x that could have produced the data y. Using probabilistic ML models, the ability to approximate any arbitrary probability distribution is recovered under universal density approximation theorems [83], and it is this property that guides our choice of ML architectures.

In this inverse task, the distinction between ML and numerical fitting becomes especially clear. Numerical fitting approximates a single susceptibility curve by iteratively varying the set of Hamiltonian parameters, allowing determination of parameters specific to that curve. ML, by contrast, aims to approximate an abstract relationship between many susceptibility curves and their corresponding parameters. Although this generalization may sacrifice the precision with which individual curves are reproduced in numerical fitting, it can offer distinct advantages: Firstly, modeling the entire mapping provides us with instantaneous predictions for a specific input curve. Second, generalizing over large and diverse training datasets should enable appropriately designed ML models to extract physically relevant information while being less sensitive to, e.g., experimental inaccuracies, which numerical fitting is often highly vulnerable to. It is such capabilities that, in our perspective, make ML a promising alternative to traditional fitting for data analysis.

Before training the ML model, the input data must be transformed into a suitable form. This “data preprocessing” step typically involves normalizing the data to the range and may include additional transformations designed to emphasize meaningful features of the data. A particular type of preprocessing strategy that this work will investigate is that of data augmentation [75,84,85,86,87,88]. In our case, artificial experimental errors are added to the training data effectively expanding the dataset size. By applying perturbations to the curves in the training dataset while keeping the corresponding ligand-field parameters unchanged, the ML model is encouraged to generalize over these variations, thereby potentially improving the robustness of physically relevant parameter predictions when presented with actual experimental data.

Lastly, another potential source of confusion is that ML has developed its own terminology for concepts already familiar to the SMM community. For instance, the least-squares error is referred to as MSE or more generally as loss function in ML frameworks, and the process of “fitting” is now called “learning”. A more substantial example is the term “model”. In the context of data analysis, it refers to the function or, in fact, the Hamiltonian Equation (1), whereas in ML it denotes the specific ML architecture, which is largely independent of the Hamiltonian, as this information is encoded in the training dataset. Even more confusing can be the different use of the term “experiment”. In ML, an experiment does not refer to a physical laboratory experiment. Rather, it generally denotes a controlled procedure for training, testing, and evaluating an ML model, i.e., running an ML model under specific conditions to study its behavior or performance. In short, it is about testing computational procedures rather than conducting physical measurements. In this work, we aim to avoid misinterpretations by, e.g., consistently referring to an ML model.

1.2. Our Perspective

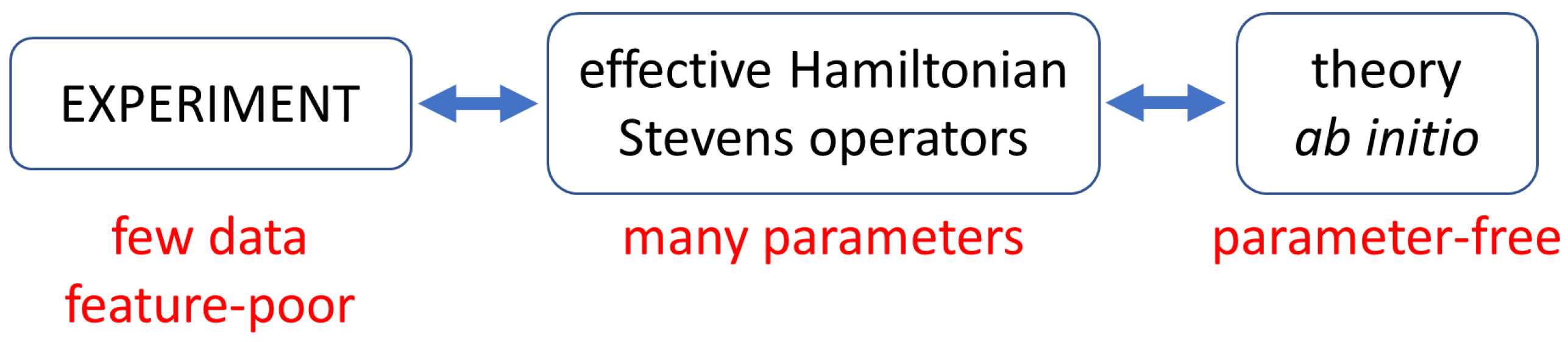

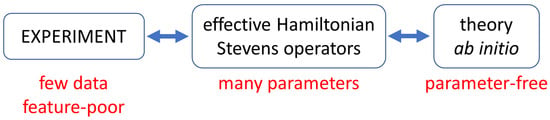

As indicated in the introduction, a fundamental challenge in studying lanthanide-containing magnetic clusters is the severe mismatch between the number of parameters in the effective spin Hamiltonian Equation (1) and the amount of information present in experimental data such as magnetic susceptibility. The effective spin Hamiltonian concept emerged decades ago as a highly efficient tool for both describing experimental data and condensing theoretical results, thereby establishing an excellent bridge between experiment and theory [22,23], as illustrated in Figure 2. For magnetic lanthanide ions, however, this approach largely loses its effectiveness due to the mismatch described before.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the interconnections between experiment, the effective spin Hamiltonian, and theory, and the challenges in experimental studies of lanthanide-based systems (for details, see text).

In addition, it appears that experimental techniques such as electron spin resonance (EPR) and inelastic neutron scattering (INS), which have proven highly informative for transition metal clusters, often enabling high precision studies [89,90,91,92], tend to be considerably less effective for lanthanide-based compounds. For instance, the number of observable transitions in such experiments is frequently small, among other limitations [27,93,94,95]. In order to obtain more information, one may analyze a series of structurally related clusters, for example by substituting the lanthanide ions, and assume that the ligand-field parameters can be transferred across the different compounds. This strategy sometimes works very well [28,96,97], but more often it does not.

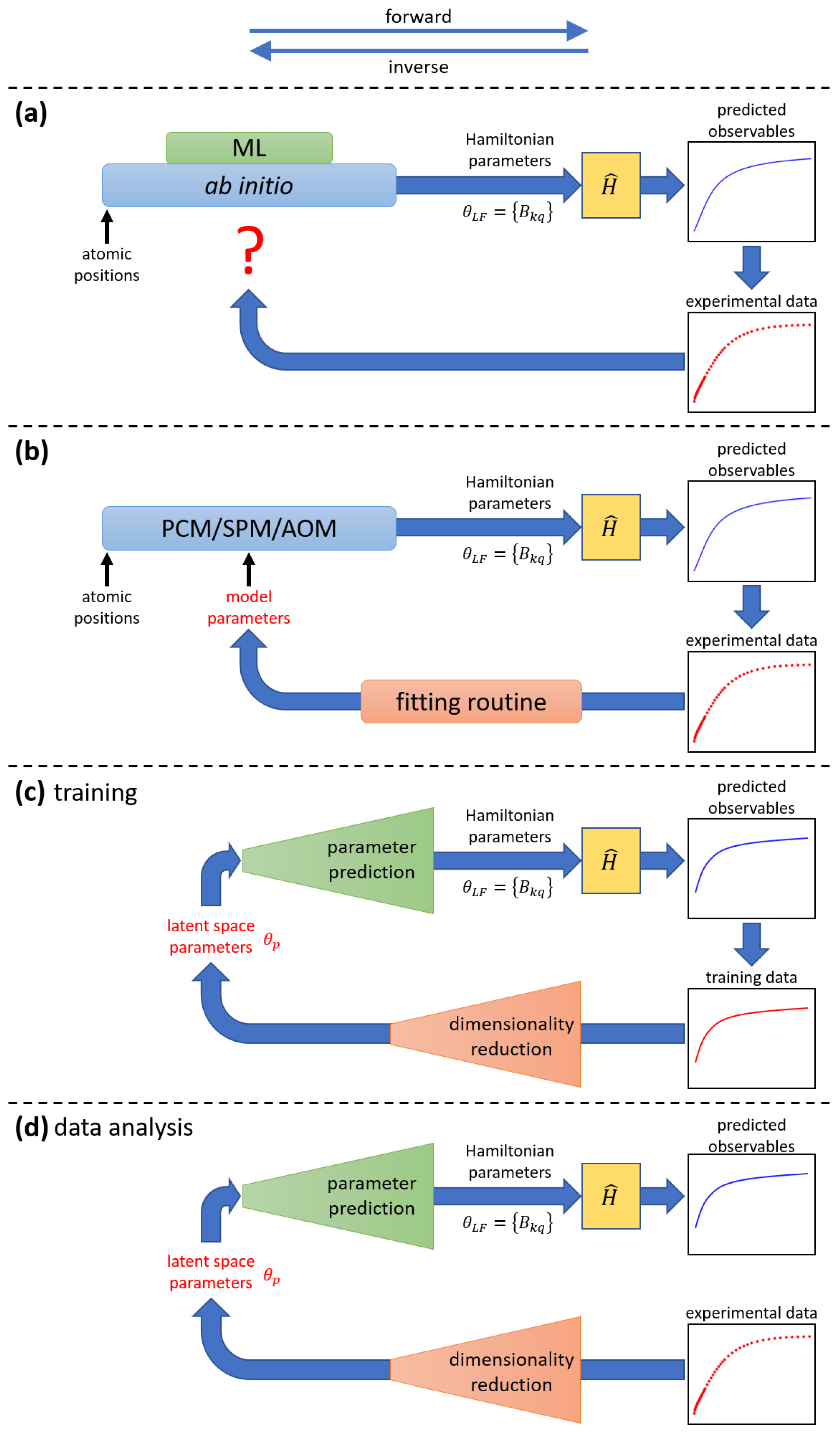

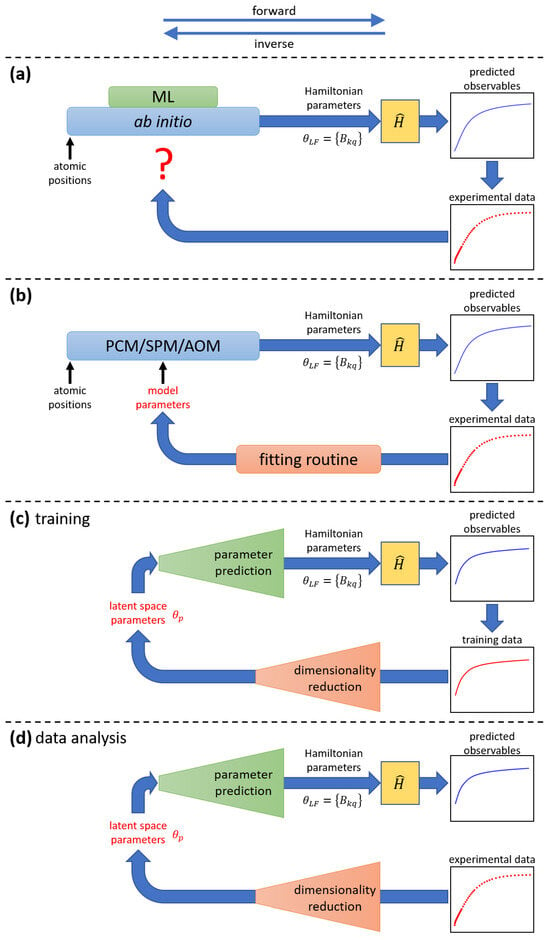

Ab initio techniques, on the other hand, are parameter-free and can produce a complete set of 27 ligand-field parameters (or more), and are increasingly becoming invaluable tools in the field [26,98]. Although these techniques are powerful, theoretical predictions often fail to perfectly reproduce experimental observations [29,54,57,99,100], and, due to the first-principles nature of these methods, it is unclear which “tuning knobs” should be adjusted to achieve improved agreement with experiment. Specifically, it remains unclear how the predicted 27 ligand-field parameters should be modified to better match the experimental data, due to both their sheer number and the incomplete understanding of their relative significance. This is illustrated in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Comparative illustration of the application of ab initio methods, phenomenological models, and ML models for the analysis of experimental data (for details, see text). At the top, the directions associated with the forward and inverse tasks are shown. (a) Ab initio techniques determine the ligand-field parameters from first principles and are parameter-free. Thus, when compared with experimental data, it is not clear how to improve the model if discrepancies between predictions and experimental observations arise. Subtasks within the ab initio method might be replaced by ML surrogates. (b) Phenomenological models, such as PCM, SPM, or AOM, can determine the ligand-field parameters from a smaller set of model parameters (parameter reduction). Discrepancies between model predictions and experimental observations can be minimized using numerical fitting methods. (c) An ML model encodes the information contained in the training dataset into a small set of latent-space parameters . During training, it iteratively compares its predictions to all curves in the training dataset and adjusts its internal parameters (weights) to minimize a loss function. (d) Once trained, the ML model can predict ligand-field parameters for new experimental data.

Obviously, a more efficient parametrization scheme than the ligand-field parameters in Equation (1) would be highly desirable. In view of the limited information contained in, e.g., the experimental data, a mathematical device realizing parameter reduction is needed, i.e., one that takes as input a relatively small number of free parameters and generates the 27 ligand-field parameters as output, which can then be fed into the Hamiltonian Equation (1). Ideally, the number of free parameters would be commensurate with the information content of the data. This mathematical device cannot be just a simple function, such as a linear mapping, but must encode the highly non-linear correlations and redundancies among the 27 ligand-field parameters.

Phenomenological ligand-field models, such as the point charge model (PCM) [101,102], super position model (SPM) [103], or angular overlap model (AOM) [104,105,106,107], along with their many variations [108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116], can provide this reduction and are hence possible candidates for this purpose. Moreover, their input parameters often have clear chemical meaning [104,107,117,118]. These models can be straightforwardly incorporated into traditional fitting schemes [28], as illustrated in Figure 3b. The models are widely used, but they come at the cost of introducing approximations that are difficult to control, especially for lanthanide ions.

The central idea of our approach, which we present here, is that parameter reduction, as well as a deeper understanding of the 27 ligand-field parameters, can be achieved using ML models. That is, the distinct variations in the susceptibility data arising from the Hamiltonian Equation (1) can be distilled into a smaller statistical parameterization, commonly called latent space parameters, . This reduced parameterization mediates between the experimental data and the underlying ligand-field parameters, . By basing the analysis solely on the variations in the susceptibility curves, the ML model can also identify the corresponding physically meaningful regions in the 27-dimensional ligand-field parameter space. The structure of these regions, in turn, provides insights into the relative importance of individual parameters, as well as their correlations and potential redundancies.

The generic architecture of such ML models thus includes a component for dimensionality reduction, where the information contained in the susceptibility curves of the training dataset is represented by a relatively small number of latent space parameters , and a component for parameter prediction (inverse of parameter reduction), which generates the ligand-field parameters from the latent space parameters . This is sketched in Figure 3c,d. During the training stage, the loop is closed: the predicted susceptibility curves are iteratively compared to the susceptibility curves in the training dataset, and the ML model’s weights are adjusted until the loss function is minimized (see Figure 3c). For application, that is, the actual analysis of an experimental susceptibility curve, the loop is open: the experimental curve is fed into the ML model, and the predicted ligand-field parameters provide the result (see Figure 3d).

One important implication of the ML approach, as emphasized earlier, is that the ML model’s objective is not to fit the experimental data as closely as possible by minimizing the least-squares error. Instead, the goal is to infer the ligand-field parameters. Because the prediction of these parameters is one step removed from the experimental curves, the ML model is inherently less sensitive to inaccuracies in the data. The proper design of the preprocessing step can further reduce sensitivity to experimental errors, as discussed earlier. It is worth mentioning that the computationally expensive task of training the ML model needs to be performed only once for a given magnetic model. Once trained, the ligand-field parameters for new experimental data can be determined almost instantaneously.

The mapping from susceptibility curves to ligand-field parameters realized by the ML model is purely statistical; any aspect of physical interpretability or rationale in the model is suspended. In this sense, the ML model is a true black box. To understand why capturing the statistics is appropriate for our purpose, it should be noted that the Hamiltonian admits only a limited number of distinct variations, i.e., ways in which the associated susceptibility curves may change in response to parameter adjustments. It is precisely these statistical variations that are represented by the latent-space parameterization. Crucially, the number of latent-space parameters required to describe the training dataset is substantially smaller than the total number of ligand-field parameters, since many of the latter are correlated or redundant due to the information asymmetry discussed before. The role of ML now becomes clear: while phenomenological models such as the PCM or AOM reduce the parameter space by appealing to physical and chemical principles, ML offers a different approach. It achieves a statistical reduction by learning directly from a large set of simulated data (the training dataset), thereby uncovering the effective free parameters (latent-space parameters). This is precisely what makes ML well suited to the task. In the broader context of molecular magnetism, the use of ML for this inverse problem of inferring Hamiltonian parameters from experimental data has largely remained unexplored, with only a few notable exceptions [65,66,119].

The methodology is clearly not limited to magnetic susceptibility and can be applied to other experimental observables as well. A natural extension would be to include low-temperature magnetization curves. However, generating magnetization curves for powder samples is far more computationally demanding than computing susceptibility curves, because numerical averaging over all magnetic field orientations is required. Accordingly, producing suitable training datasets is substantially more challenging. Focusing on magnetic susceptibility for now allows us to establish the core methods.

1.3. Challenges

There are, however, a number of challenges that arise in practice. As discussed before, a central challenge is modeling the one-to-many mapping from experimental data to ligand-field parameters. Capturing this multiplicity is significantly more demanding than predicting a single solution and requires the use of specialized probabilistic ML models capable of representing distributions rather than point estimates. Predicting all possible solutions is likely unrealistic; instead, the ML model should aim to predict a set of plausible solutions.

A further challenge concerns computational cost. To predict as many valid solutions as possible, the ML model must be trained over the full 27-dimensional ligand-field parameter space. A naive strategy would be to sample this space uniformly on a dense grid. However, such an approach is impractical: The overwhelming majority of the parameter space corresponds to ligand-field parameter values that produce trivial or uninformative susceptibility curves when simulated. Moreover, it is not known a priori which subregions of the parameter space are most likely to contain physically meaningful parameter sets. Thus, uniform sampling not only wastes computational resources but also fails to efficiently capture the regions of interest. In fact, the training of ML models strongly depends on the informative quality of the training dataset. If the dataset is dominated by uninformative or redundant samples, the ML model will struggle to learn the underlying structure. It is therefore essential not only to explore the high-dimensional parameter space efficiently but also to focus on parameter regions that generate rich and discriminative variations in the data curves. These challenges are collectively known as the “curse of dimensionality” [72,120,121,122]. The term refers to the observation that as the dimension of the parameter space increases, data points become increasingly sparse, making sampling and learning more difficult. In our previous study on the VAE-INN model, which employed naive uniform grid sampling, the curse of dimensionality limited us to no more than four ligand-field parameters [70]. Generating a suitable training dataset is thus another crucial challenge, and more advanced techniques will need to be developed in future work. In this work, for these reasons, the magnetic model includes only the D and E anisotropy parameters.

A final challenge to consider is the potential presence of experimental errors in the measured curves. Magnetic susceptibility measurements on powder samples are already relatively feature-poor and limited in the amount of information they provide, and any additional inaccuracies can have disproportionate consequences on the predicted ligand-field parameters. As regards magnetic measurements, the most common experimental errors arise from inaccuracies in the diamagnetic correction, which accounts for contributions from, e.g., the sample holder, eicosane, or Pascal’s constants, and the determination of the sample’s molar mass, which can be affected, e.g., by loss of solvent molecules and other factors. In traditional least-squares fitting, and for the types of susceptibility curves typically recorded for lanthanide SMMs, even relatively small experimental errors can lead to substantially different best-fit ligand-field parameters. Sensitivity to such errors is not only a limitation of traditional fitting but also, in principle, a challenge for ML approaches. However, as will be shown in this work for the model mentioned, this issue can be largely mitigated in the ML framework by proper data preprocessing, which represents the main result of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Magnetic Model

In this work, the powder magnetic susceptibility of a single ion (total angular momentum , Landé g factor ) is considered, as modeled by Equation (1) up to second-order (). The five parameters can be reduced to two free parameters by a suitable choice of coordinate frame, conventionally taken as and , with the remaining parameters satisfying . The parameters D and E correspond to the axial and rhombic components of the anisotropy, respectively. There exist indeed six such choices of coordinate frame, and thus six physically equivalent D, E parameter sets that produce identical powder susceptibility curves (see Appendix A). The g factor was set to the Landé value in all simulations. Two types of experimental errors are considered, namely inaccuracies in the diamagnetic correction and in the determination of the sample’s molar mass. They are modeled as

where represents a diamagnetic correction error and a molar-mass error (in the absence of such errors holds , ), and refers to the simulated curve as obtained from Equation (1). A simulated susceptibility curve is thus characterized by the four parameters D, E, , and .

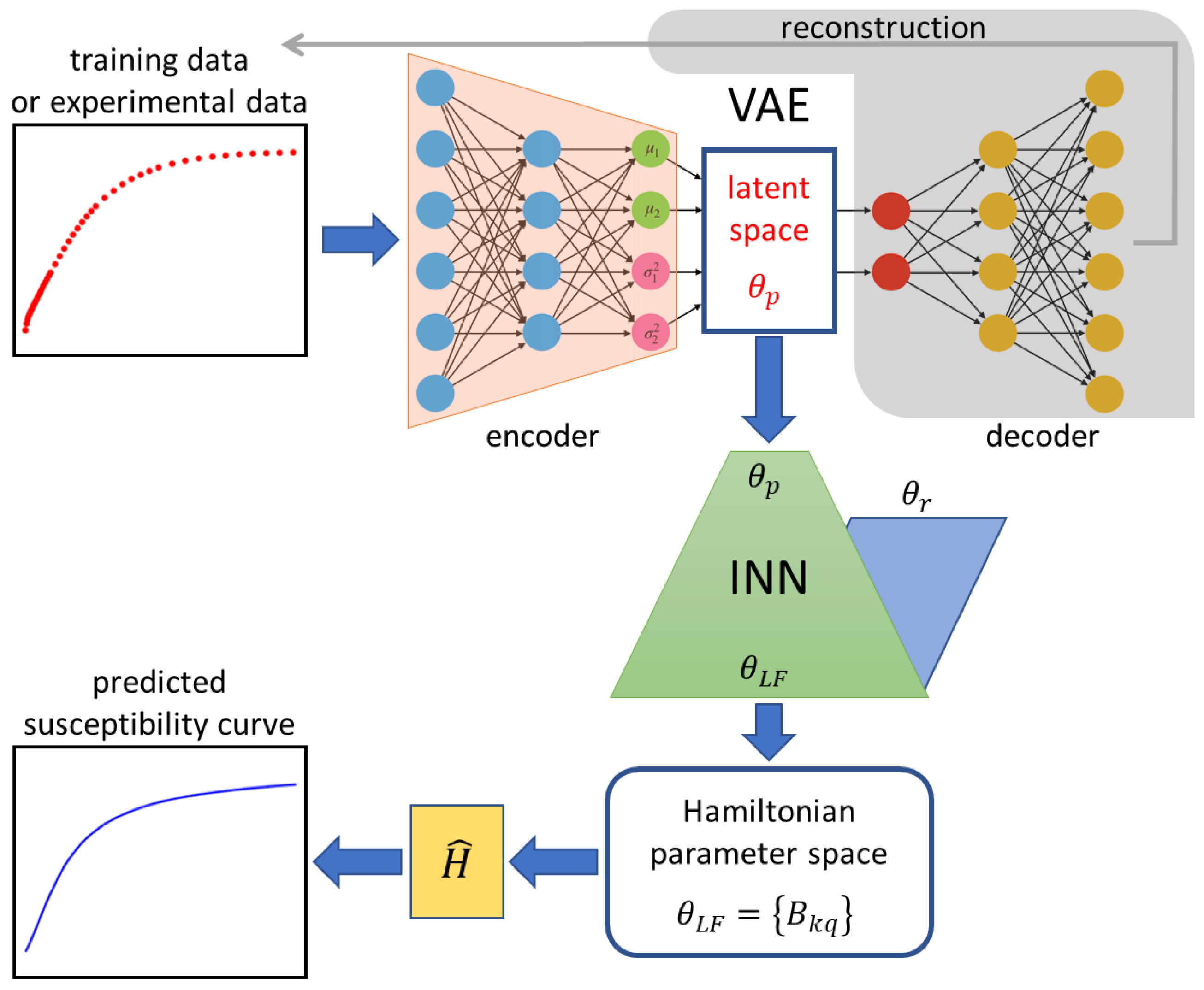

2.2. VAE-INN Model and Training Datasets

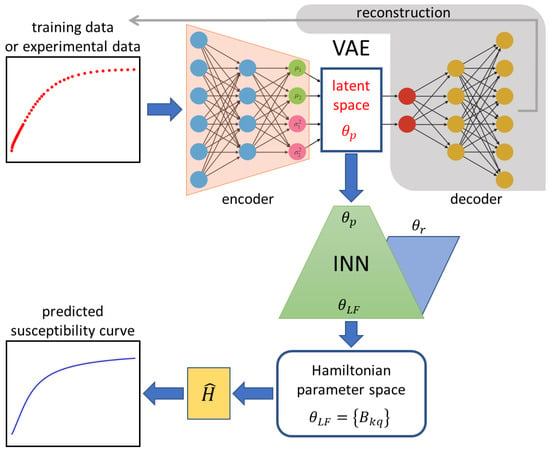

The architecture of the employed VAE-INN model is depicted in Figure 4. The VAE-INN is described here only qualitatively; the full theoretical formulation, hyperparameter specifications, and training methodology can be found in Ref. [70]. The VAE-INN model can be divided into the VAE and INN components. The VAE is used for dimensionality reduction. The variations in the magnetic susceptibility data are encoded into three latent space variables, , , and , i.e., . Once trained, the VAE maps a supplied input susceptibility curve to a unique point in the latent space, such that similar susceptibility curves are mapped to nearby points. The INN component is trained to learn the one-to-many mapping that relates the unique latent-space representation of the input susceptibility curve to the potentially multiple (non-unique) ligand-field parameters . Thus, for a given input susceptibility curve, the VAE-INN first determines the latent space parameterization and then predicts associated ligand-field parameter sets. For every predicted ligand-field parameter set, the corresponding powder magnetic susceptibility curve can then be simulated using the Hamiltonian and compared with the input susceptibility curve.

Figure 4.

Scheme of the VAE-INN architecture. The VAE encodes experimental temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility data (red scatter plot) to a unique point in the latent space for which the INN predicts all associated sets of ligand-field parameters . The INN solves the inverse task of parameter prediction by augmenting the latent space parameters with randomly sampled auxiliary parameters . The parameter predictions are then used to simulate susceptibility curves (blue line plot), which can be compared with the original input curve. The component shaded in gray is required for training the VAE, but not for application, i.e., analysis of an input curve.

The datasets for learning the VAE-INN were generated as follows: First, 57,000 values of D and E were uniformly sampled from the ranges K and K. For each D, E parameter set, the powder magnetic susceptibility curve was computed for K. Ten duplicate curves were then generated by introducing errors in the diamagnetic correction and molar-mass through sampling and from Gaussian distributions with standard deviations and . These Gaussian distributions describe the likelihood of the experimental errors, and the widths reflect the accuracy of the experimental procedure. This augmentation resulted in a total dataset size of 627,000 curves. Data provided as input to NNs generally requires scaling in order to achieve comparable features and smoother optimization. Therefore, all susceptibility data were normalized to lie in the range by the transformation

where is the susceptibility data from the training dataset, and are the global minimum and maximum of the complete training dataset, and is the curve supplied to the VAE-INN. This normalization step is also applied to any input susceptibility curve. An 80/20 split was made to obtain the training and testing datasets for the purpose of validation of the VAE-INN model. The hyperparameters of the VAE and INN components were identical to those given in Ref. [70], with the exception that the VAE encoding was found to now require a three-dimensional latent space (three parameters in ). This is expected, as the experimental errors introduce additional, distinct variations in the susceptibility curves, thereby increasing the complexity of the dataset. Several datasets with different values of were generated and used to train the VAE-INN, in order to systematically study the effect of data augmentation. The molar-mass error was found to be less relevant than the diamagnetic error, as it is partially accounted for by the normalization step; accordingly, it was held constant to in this work.

2.3. Input Susceptibility Curves

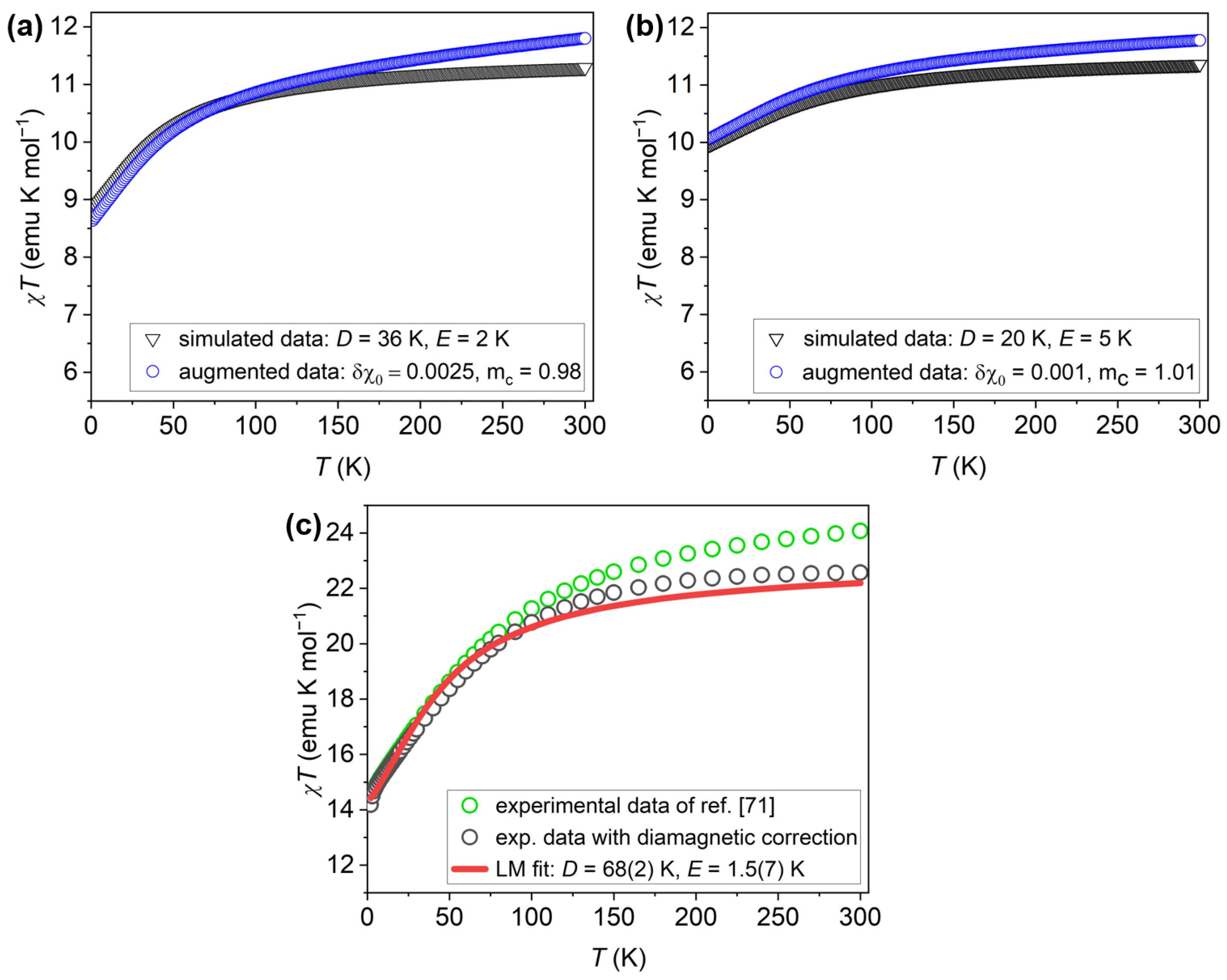

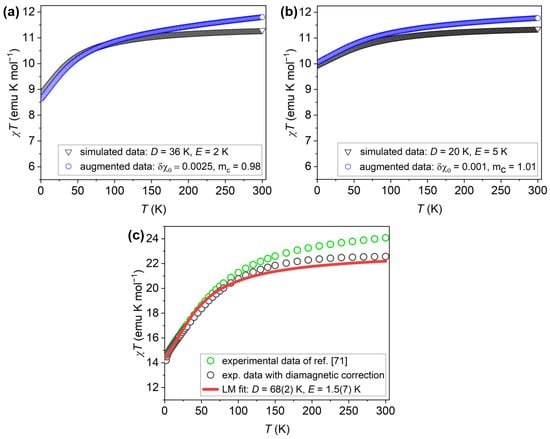

The performance of the VAE-INN model is demonstrated below by presenting results for three input susceptibility curves. The first two curves, generated by simulation, will be referred to as “simulated experimental curves”. Such curves are especially valuable for evaluating the ML model because the ground-truth ligand-field parameters D, E are known exactly. The two curves correspond to the parameter sets K, K, emu/mol, , and K, K, emu/mol, ; they are shown in Figure 5a and Figure 5b, respectively. The first curve displays a more pronounced curvature but includes a relatively large diamagnetic correction, whereas the second is comparatively flat and feature-poor, with a smaller simulated diamagnetic inaccuracy. These curves will be referred to as the “axial” and “rhombic” cases in the following. The third input curve consists of the experimental susceptibility data of [71], shown in Figure 5c. The data were properly treated, e.g., diamagnetic corrections accounting for the sample holder were employed [71]. However, empirical evidence indicated that the diamagnetic correction was substantially inaccurate, and the error was estimated to emu/mol, or emu/mol per ion [70]. In the previous work [70], the experimental susceptibility curve was therefore corrected for that inaccuracy, and the corrected curve was used in all analyses in that work. In order to obtain reference D, E values, the corrected susceptibility curve was analyzed using Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) least-squares fitting, which yielded K and K. In this work, however, the original experimental curve, as reported in Ref. [71], will be analyzed; the LM fit values K and K, and the estimated diamagnetic correction of emu/mol, will serve as baseline for comparison with the ML approach in this work (note that is the negative of the diamagnetic correction applied to the experimental data, as it is defined with respect to the ground-truth susceptibilty curve).

Figure 5.

Input susceptibility curves employed in this work. (a) Simulated experimental susceptibility for the “axial” case with parameters K, K, emu/mol, and (blue open circles). For reference, the simulated curve , unaffected by simulated experimental errors, is also shown (black open triangles). (b) Simulated experimental susceptibility for the “rhombic” case with parameters K, K, emu/mol, (blue open circles). For reference, the simulated curve , unaffected by simulated experimental errors, is also shown (black open triangles). (c) Experimental susceptibility data of as reported in Ref. [71] (green open circles) and after applying an empirically determined diamagnetic correction (black open circles). Also shown is the result of an LM least-squares fit to the corrected experimental curve (red solid line); the resulting parameters are given in the text. contains two ions per molecule, and hence the values are twice as large as for a single ion. This is accounted for by division by two in all numerical work, but the resulting susceptibility curves are shown with respect to .

The “rhombic” simulated experimental curve, but without experimental errors, and the corrected experimental data were used in the previous work [70]. Using them again here, now with experimental inaccuracies included, permits a direct comparison with the earlier results and thereby provides an assessment of the impact of the augmented dataset on the VAE–INN model.

2.4. Evaluation Method

To evaluate the performance of the VAE–INN model, it was found that it is particularly instructive to focus on the VAE latent space rather than on the final VAE–INN output. The INN processes the information encoded in the latent space and merely translates it into a user-friendly output. Focusing on the latent space, therefore, provides a more systematic evaluation, as it avoids potential additional effects introduced by the INN. For representing the latent space, the following method was employed: Given the latent-space point predicted for the input susceptibility curve, a narrow region of interest (ROI) was defined around this point to include the 400 closest curves from the training dataset. The curves within the ROI were then represented as points in a D-E diagram according to their ligand-field parameters D and E, with a color indicating their normalized probability density (dark red = high density, dark blue = low density; Gaussian kernel density estimation was used for calculating the normalized probability density in the D-E space [123]). These diagrams are referred to as “VAE plots” in the following. For representing the VAE-INN, 1000 parameter predictions were drawn and plotted in a D-E diagram as before, using a similar color scheme (“VAE-INN plot” henceforth). For the two simulated experimental susceptibility curves, only VAE plots are presented.

3. Results

3.1. Simulated Experimental Susceptibility Curves

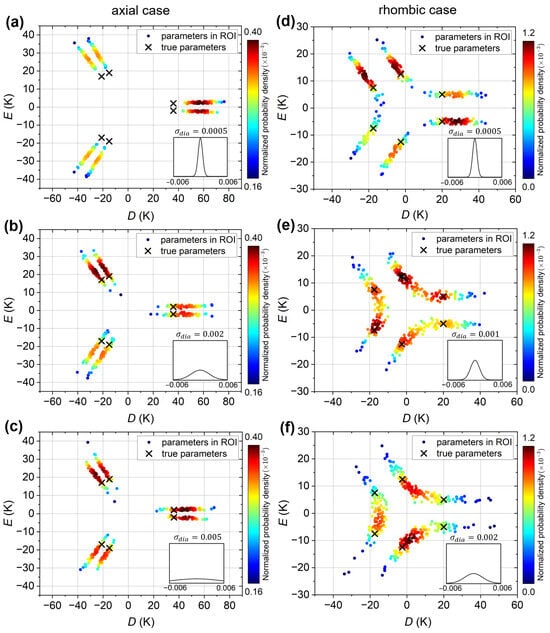

Figure 6a–c show the VAE plots for the “axial” simulated experimental curve, for VAEs trained with , , and emu/mol datasets, respectively. The true ligand-field parameters K and K, as well as the other five physically equivalent parameter sets, are indicated by crosses. In all three plots, six clusters, or regions of high density, are observed, indicating that the VAE successfully recovers the six solutions. However, for the VAE trained with the emu/mol dataset (Figure 6a), the predictions are all shifted away from the true parameter values; that is, the magnitude of D is significantly overestimated. Increasing to 0.002 emu/mol (Figure 6b) improves the predictions, bringing them closer to the true values. However, further increasing provides no additional improvement, as demonstrated for emu/mol in Figure 6c. On the flip side, this means that the VAE model retains its predictive capability for the “axial” simulated experimental curve even when trained on datasets with large . It is noted that emu/mol is comparable to the artificial diamagnetic error emu/mol of the “axial” simulated experimental curve. The results thus suggest that if the range of diamagnetic errors in the training dataset is too narrow, as compared to the error in the input susceptibility curve, the VAE’s predictive capability is reduced. For larger , the VAE predictions improve up to a limit, beyond which no further improvement is obtained.

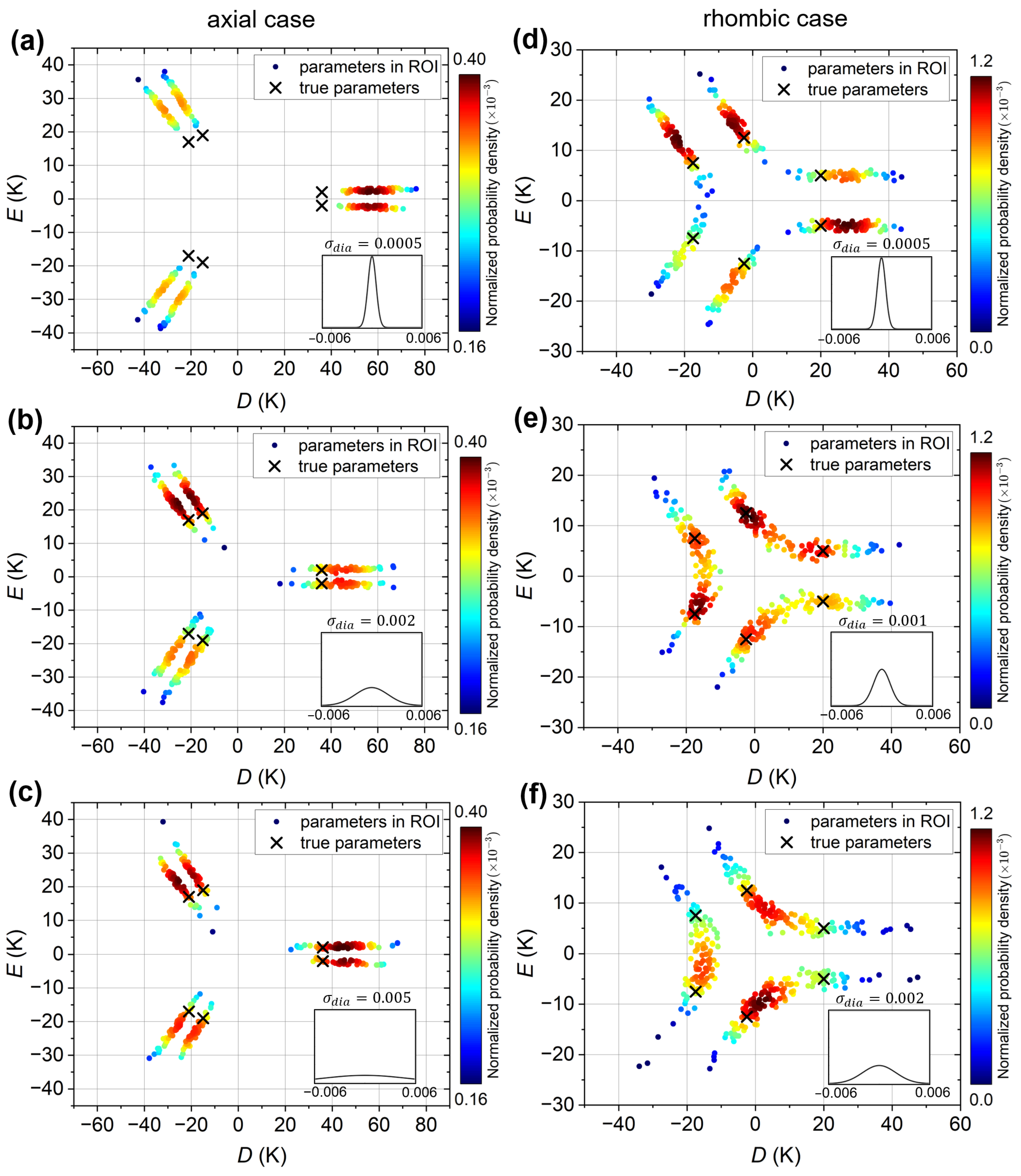

Figure 6.

VAE plots of the simulated experimental susceptibility curves; predictions in the ROI are plotted as solid circles and colored by their normalized probability density (dark red: highest probability, dark blue: lowest probability). (a–c) VAE plots for the “axial” simulated experimental susceptibility curve, for VAEs trained on datasets with equal to (a) emu/mol, (b) emu/mol, and (c) emu/mol. (d–f) VAE plots for the “rhombic” simulated experimental susceptibility curve, for VAEs trained on datasets with equal to (d) emu/mol, (e) emu/mol and (f) emu/mol. In all panels, the black crosses indicate the six physically equivalent parameter sets corresponding to the true D and E values given in the text. The insets show the Gaussian distributions of the diamagnetic errors in the training datasets.

For the “rhombic” simulated experimental curve, the VAE plots are shown in Figure 6d–f for VAEs trained with , and emu/mol datasets, respectively. The six parameter sets corresponding to the true K and K ligand-field parameters of this curve are again indicated by crosses. For emu/mol (Figure 6d), six clusters (regions of high density) are observed, with the predictions overestimating the magnitude of D, similar to the “axial” case but with a smaller overestimation. As increases to emu/mol (Figure 6e), the six clusters, or more precisely, the probability maxima, shift toward the true values, essentially reproducing them perfectly. However, pairs of clusters begin to merge, resulting in a relatively high solution probability between the maxima. For emu/mol (Figure 6f), the pairs of clusters have merged completely, resulting in only three broad regions of high density, with the maxima located between the true solutions. Thus, for the “rhombic” simulated experimental curve, the trend with increasing is initially similar to that of the “axial” case, but when increases beyond the input curve’s experimental error, the parameter predictions become less accurate. This can be attributed to the fact that the variation in the “rhombic” curve due to the ligand-field parameters is much weaker than in the “axial” curve, and not easily distinguished from the variations caused by the diamagnetic error.

3.2. Experimental Susceptibility Curve

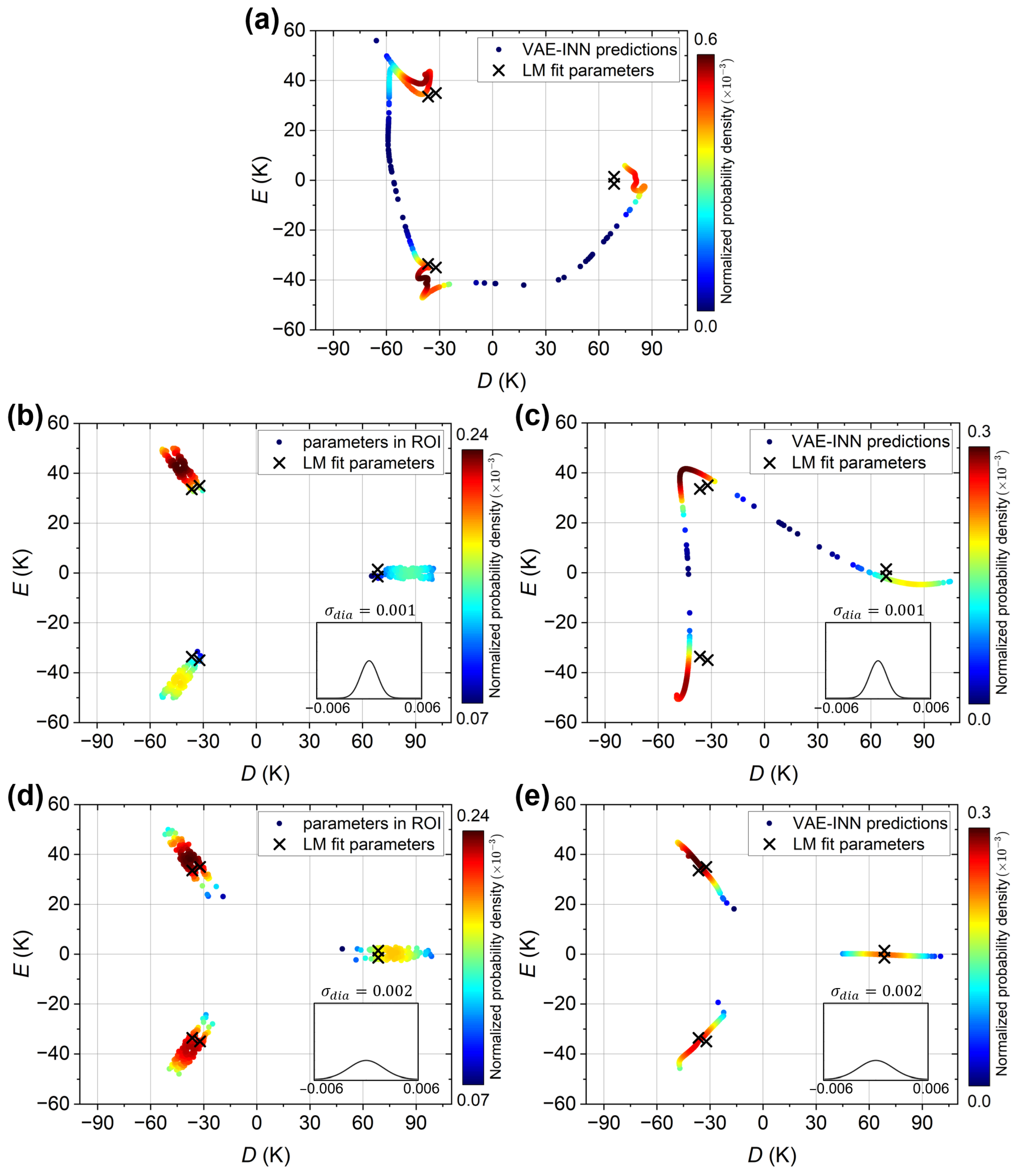

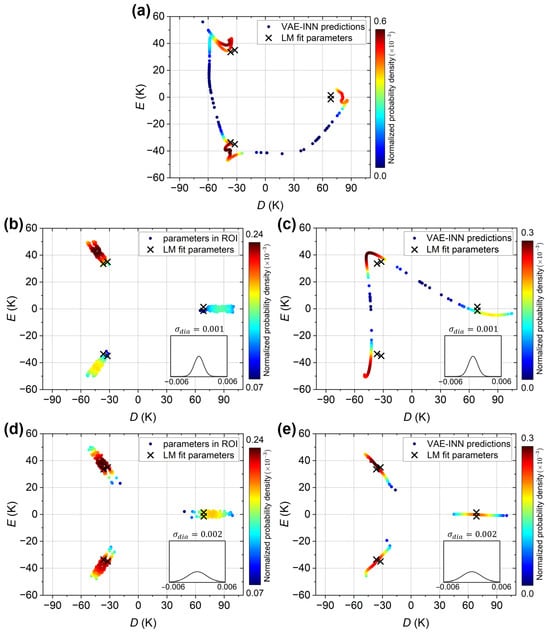

The case of the experimental susceptibility curve is considered next. For reference, the VAE-INN plot reported in the previous work Ref. [70] is reproduced in Figure 7a. It shows the VAE-INN output for the corrected experimental susceptibility curve (black open circles in Figure 5c) with the VAE-INN trained on a dataset without augmentation (). The six parameter sets corresponding to the LM best-fit values K and K are indicated as black crosses. Because of the small ratio, the crosses occur in closely spaced pairs. The VAE-INN predicts three regions of high probability, which are close to, but slightly shifted away from, the LM fit solutions, again corresponding to an overestimation of the magnitude of D. The VAE-INN cannot resolve the closely spaced pairs among the six LM solutions, i.e., the small E value.

Figure 7.

VAE and VAE-INN predictions for the experimental susceptibility curve. Predictions are plotted as solid circles and colored according to their normalized probability density (dark red: highest probability, dark blue: lowest probability). Panel (a) reproduces the previous results reported in Ref. [70], showing the VAE-INN plot for the corrected experimental susceptibility curve described in the text, with the VAE-INN trained on a dataset without augmentation. Panels (b,c) present the VAE and VAE-INN plots, respectively, when trained on a dataset with emu/mol. Panels (d,e) present the VAE and VAE-INN plots, respectively, when trained on a dataset with emu/mol. In all panels, the black crosses indicate the six physically equivalent parameter sets corresponding to the LM best-fit D and E values given in the text. The insets show the Gaussian distributions of the diamagnetic errors in the training datasets.

With regards to the performance for the actual experimental susceptibility curve (green open circles in Figure 5c), Figure 7b and Figure 7c show the VAE and VAE-INN plots, respectively, when trained with a emu/mol dataset. Again, similar as before, three clusters are observed, indicating that the small E value is not resolved, and the predictions are shifted away from the LM reference values. The shifts are somewhat larger than in Figure 7a, but it should be noted that here the experimental input curve includes a substantial diamagnetic error. Considering this, the performance of the VAE-INN with the emu/mol data augmentation is satisfactory. The VAE-INN plot closely reproduces the features in the VAE plot, as expected for a well-performing INN. Lastly, Figure 7d and Figure 7e show the VAE and VAE-INN plots, respectively, when trained with a emu/mol dataset. Again, the small E value cannot be resolved, but the clusters (regions of high density) are now very close to the LM reference values. That is, the VAE or VAE-INN model provides estimates of the D and E parameters accurate to within a few Kelvin, despite the substantial diamagnetic error in the experimental susceptibility curve. Further increasing does not result in additional improvement, similar to the earlier observation for the “axial” curve.

It is mentioned that, from an experimental point of view, a diamagnetic error of 0.0025 emu/mol, as estimated for the susceptibility curve, is unusually large and at the upper end of the acceptable range for well-conducted experiments (probably rather exceeding it). That is, training datasets augmented with emu/mol should represent a reasonable choice for most cases.

4. Discussion

The presented results suggest several points for discussion regarding the relationship between the experimental error distributions in the augmented training dataset and the information content of magnetic susceptibility curves.

First, it should be emphasized that the previous version of the VAE-INN model [70], trained on an unaugmented dataset, fails when applied to the actual experimental susceptibility data of . That is, the VAE encodes this curve into a latent-space point falling outside the populated region of the latent space. The resulting VAE-INN predictions are highly inaccurate, indicating a typical breakdown of the ML model when input data lie outside the distribution of the training dataset. With that earlier VAE-INN model, it was necessary to adjust the experimental data “by hand” for the estimated diamagnetic error in order for the VAE-INN to successfully predict ligand-field parameters. The ability of the augmented VAE-INN presented here to make reasonable predictions even when supplied with experimental data affected by substantial diamagnetic inaccuracy demonstrates the effectiveness of the data augmentation.

The analysis of the (augmented) VAE-INN for the “axial” simulated experimental curve, as a function of the diamagnetic error distribution , revealed increasing accuracy in the predicted ligand-field parameters. For low , the ML model is biased toward small diamagnetic errors and is therefore less likely to attribute curvature in the input curve to a diamagnetic contribution. Instead, it compensates by adjusting the predicted ligand-field parameters. As increases, larger diamagnetic errors appear more frequently in the training dataset, and the VAE-INN becomes better at accounting for them. Increasing beyond a certain threshold, however, does not further improve the accuracy of the ML model. This is expected, since large values progressively skew the training dataset toward physically implausible curves that are irrelevant for training the ML model. Overall, a moderate improves the robustness of the VAE-INN model and enables it to effectively ignore the experimental inaccuracies in the data. The fact that this robustness, up to a certain threshold, depends on the augmentation width suggests that the VAE-INN internally weighs competing explanations for curve variations according to their probability in the training distribution.

Beyond prediction accuracy, the results on the simulated experimental susceptibility curves also clarify how robustness to experimental errors depends on the information content of the curve. For the “rhombic” simulated experimental curve, prediction accuracy initially improves but degrades for values beyond a comparatively small threshold. This behavior is consistent with the fact that the “rhombic” curve contains less intrinsic information about the ligand-field parameters than the “axial” curve. The “rhombic” curve, without simulated experimental errors, was also studied in the previous work Ref. [70], where the (unaugmented) VAE-INN model accurately predicted the ligand-field parameters. Introducing a positive diamagnetic error, however, makes the curve more linear and reduces the distinctive features available for the VAE to encode. For large , the substantial diamagnetic errors in the training dataset obscure information about the ligand-field parameters, making it harder for the VAE to discriminate curves that correspond to physically different parameters. As a result, initially distinct clusters of high probability density merge, deteriorating the parameter predictions. This highlights that robustness also depends on the level of experimental error relative to the information content about the ligand-field parameters in the curve. Feature-rich susceptibility curves can tolerate a broader diamagnetic error distribution in the augmented dataset, whereas feature-poor input curves do not support the same level of prediction accuracy. This is expected, but it is reassuring to see it confirmed by the results. This behavior is not specific to the VAE-INN architecture but a general limitation of inverse problems, when observable data contain limited information and correspond to non-unique solutions. With regard to practical application, (and ) should be treated as a prior and adjusted according to the experimental uncertainty of the specific measurement device and protocol (sample handling, sample holder corrections, solvent loss, etc.). As noted for the experimental susceptibility curve, a value of emu/mol may often be a suitable choice.

A key result of this work is that incorporating physically motivated experimental errors during training renders the VAE–INN a practical tool for interpreting magnetic susceptibility data that would otherwise be more difficult to analyze. With augmentation, the training distribution captures both the variations arising from the forward Hamiltonian physics (here limited to the D, E model) and the deviations of real measurements from ideal curves due to diamagnetic and molar-mass errors. This corresponds to inferring parameters under a noise model and explains why the same architecture that struggles with experimental inaccuracies in an unaugmented setting can now recover physically meaningful ligand-field parameters. The VAE model encodes error-induced variations in the susceptibility curves into the same statistical space that captures variations due to ligand-field parameters. As mentioned above, the VAE required a higher-dimensional latent space when trained on augmented datasets (three-dimensional instead of two-dimensional). This is more than a technical adjustment: it suggests that some directions in the latent space act as “nuisance directions” associated with errors and scalings, while the remaining directions encode the physically meaningful variations due to the ligand-field parameters. Disentangling these into separate subspaces allows the ML model to recover accurate ligand-field parameters even when the input curve is substantially distorted by experimental errors.

Compared to traditional least-squares fitting routines, the VAE-INN approach offers several major advantages. First, it can predict multiple plausible solutions across a broad range of ligand-field parameters, rather than returning a single best-fit parameter set. Second, its predictions are determined by generalizing from a large training dataset, which helps the ML model infer physically meaningful parameters. As demonstrated in this work, data augmentation can enhance these capabilities by reducing the ML model’s sensitivity to experimental inaccuracies that often bias traditional fitting procedures. The demonstration was limited to the second-order D, E model, and conclusions regarding robustness are therefore established in a low-dimensional setting. However, the data augmentation strategy can be extended to magnetic models with additional ligand-field parameters. This will require careful attention to the construction of the training dataset, as emphasized in Section 1.3, since prediction accuracy depends on how well the training dataset represents the relevant variations in the susceptibility curves. Including higher-order ligand-field parameters will therefore require informed dataset construction techniques, such as guided sampling of parameter space to focus on regions that produce discriminative curve variations. Additional constraints can also help, and training on multiple observables, such as susceptibility together with magnetization curves or energy spectrum data, can reduce non-uniqueness. That is, with more ligand-field parameters, data augmentation will likely remain valuable, but more sophisticated techniques for constructing the training dataset will also need to be developed in the future.

In conclusion, the data augmentation presented in this work renders the VAE-INN approach a practical tool for analyzing magnetic susceptibility data within the D, E model. Further improvements may be achieved by combining data augmentation with more sophisticated preprocessing strategies, such as one-dimensional convolutional filtering. Extending the architecture to include higher-order ligand-field parameters, however, remains the main challenge and will require further dedicated studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A.A. and O.W.; methodology, P.T. and Z.A.A.; software, Z.A.A. and P.T.; validation, P.T. and Z.A.A.; formal analysis, Z.A.A. and P.T.; investigation, Z.A.A. and P.T.; resources, O.W.; data curation, Z.A.A. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.A.A. and O.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.A.A. and O.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors (technical limitations).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the group of Annie K. Powell for providing the experimental data of in electronic format. We also want to take this opportunity to sincerely thank Annie and her group members for the decades-long close collaboration and friendship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Within the D, E ligand-field model, each parameter set gives rise to five additional sets that result in exactly the same powder magnetic susceptibility curve. When D, E refer to the set that fulfills the conditions and , the six equivalent solutions are given by the following:

For further details, see [70].

References

- Christou, G.; Gatteschi, D.; Hendrickson, D.N.; Sessoli, R. Single-Molecule Magnets. MRS Bull. 2000, 25, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatteschi, D.; Sessoli, R.; Villain, J. Molecular Nanomagnets; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sessoli, R.; Tsai, H.L.; Schake, A.R.; Wang, S.; Vincent, J.B.; Folting, K.; Gatteschi, D.; Christou, G.; Hendrickson, D.N. High-spin molecules: [Mn12O12(O2CR)16(H2O)4]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Sarachik, M.P.; Tejada, J.; Ziolo, R. Macroscopic Measurement of Resonant Magnetization Tunneling in High-Spin Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 3830–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Lionti, F.; Ballou, R.; Gatteschi, D.; Sessoli, R.; Barbara, B. Macroscopic quantum tunnelling of magnetization in a single crystal of nanomagnets. Nature 1996, 383, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernsdorfer, W.; Sessoli, R. Quantum phase interference and parity effects in magnetic molecular clusters. Science 1999, 284, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. Making qubits from magnetic molecules. Phys. Today 2025, 78, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pineda, E.; Wernsdorfer, W. Magnetic Molecules as Building Blocks for Quantum Technologies. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2025, 8, 2300367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.S.; Paillot, K.; Breslavetz, I.; Novitchi, G.; Rikken, G.L.J.A.; Train, C.; Atzori, M. Optical Readout of Single-Molecule Magnets Magnetic Memories with Unpolarized Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 23616–23624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, M.; Chiesa, A.; Lepori, L.; Carretta, S. Fault-tolerant computing with single-qudit encoding in a molecular spin. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 4961–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Canaj, A.B.; Liu, S.; Regincós Martí, E.; Celmina, A.; Nichol, G.; Cheng, H.P.; Murrie, M.; Hill, S. Engineering Clock Transitions in Molecular Lanthanide Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 11083–11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Santini, P.; Garlatti, E.; Luis, F.; Carretta, S. Molecular nanomagnets: A viable path toward quantum information processing? Rep. Prog. Phys 2024, 87, 034501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernot, K. Get under the Umbrella: A Comprehensive Gateway for Researchers on Lanthanide–Based Single–Molecule Magnets. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N. Simultaneous Determination of Ligand-Field Parameters of Isostructural Lanthanide Complexes by Multidimensional Optimization. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 5831–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N. Single molecule magnet with single lanthanide ion. Polyhedron 2007, 26, 2147–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.H.; Burchell, T.J.; Ungur, L.; Chibotaru, L.F.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Murugesu, M. A polynuclear lanthanide single-molecule magnet with a record anisotropic barrier. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9489–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, D.N.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Layfield, R.A. Lanthanide single-molecule magnets. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5110–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Kalita, P.; Chandrasekhar, V. Lanthanide(III)-Based Single-Ion Magnets. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 9462–9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernot, K.; Daiguebonne, C.; Calvez, G.; Suffren, Y.; Guillou, O. A Journey in Lanthanide Coordination Chemistry: From Evaporable Dimers to Magnetic Materials and Luminescent Devices. Accounts Chem. Res 2021, 54, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala-Lekuona, A.; Seco, J.M.; Colacio, E. Single-Molecule Magnets: From Mn12-ac to dysprosium metallocenes, a travel in time. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 441, 213984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, O. A criterion for the anisotropy barrier in single-molecule magnets. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 10035–10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.W.H. Matrix Elements and Operator Equivalents Connected with the Magnetic Properties of Rare Earth Ions. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A 1952, 65, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abragam, A.; Bleaney, B. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Transition Ions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Manvell, A.S.; Pfleger, R.; Bonde, N.A.; Briganti, M.; Mattei, C.A.; Nannestad, T.B.; Weihe, H.; Powell, A.K.; Ollivier, J.; Bendix, J.; et al. LnDOTA puppeteering: Removing the water molecule and imposing tetragonal symmetry. Chem. Sci. 2023, 15, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelli, C.; Gatteschi, D. Introduction to Molecular Magnetism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ungur, L.; Chibotaru, L.F. Ab Initio Crystal Field for Lanthanides. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 3708–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prša, K.; Nehrkorn, J.; Corbey, J.; Evans, W.; Demir, S.; Long, J.; Guidi, T.; Waldmann, O. Perspectives on Neutron Scattering in Lanthanide-Based Single-Molecule Magnets and a Case Study of the Tb2(μ-N2) System. Magnetochemistry 2016, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutschler, J.; Ruppert, T.; Peng, Y.; Schlittenhardt, S.; Schneider, Y.F.; Braun, J.; Anson, C.E.; Ollivier, J.; Berrod, Q.; Zanotti, J.M.; et al. Finding lanthanide magnetic anisotropy axes in 3d-4f butterfly single-molecule magnets using inelastic neutron scattering. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2025, 6, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, O. Relation between Electrostatic Charge Density and Spin Hamiltonian Models of Ligand Field in Lanthanide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, O. Chiral symmetry in ligand field models with a focus on lanthanides. Z. Für Naturforschung A 2025, 81, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfield, J.J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 2554–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlman, S.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Sejnowski, T.J. Massively Parallel Architectures for AI: NETL, Thistle, and Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 22–26 August 1983; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; Volume 3, pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E. Computation by neural networks. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, J.; Parrinello, M. Generalized Neural-Network Representation of High-Dimensional Potential-Energy Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 146401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartok, A.P.; Payne, M.C.; Kondor, R.; Csanyi, G. Gaussian Approximation Potentials: The Accuracy of Quantum Mechanics, without the Electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 136403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. Machine learning interatomic potential: Bridge the gap between small-scale models and realistic device-scale simulations. iScience 2024, 27, 109673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, S.; Fernandez-Serra, M. Machine learning accurate exchange and correlation functionals of the electronic density. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; McMorrow, B.; Turban, D.H.P.; Gaunt, A.L.; Spencer, J.S.; Matthews, A.G.D.G.; Obika, A.; Thiry, L.; Fortunato, M.; Pfau, D.; et al. Pushing the frontiers of density functionals by solving the fractional electron problem. Science 2021, 374, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Fonseca, E.; Perry, W.; Cheng, H.P.; Zhang, X.G.; Hennig, R.G. Ligand Optimization of Exchange Interaction in Co(II) Dimer Single Molecule Magnet by Machine Learning. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Junior, H.C.; Menezes, H.N.S.; Ferreira, G.B.; Guedes, G.P. Rapid and Accurate Prediction of the Axial Magnetic Anisotropy in Cobalt(II) Complexes Using a Machine-Learning Approach. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 14838–14842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, A.; Sanvito, S. Multiple spin-phonon relaxation pathways in a Kramer single-ion magnet. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 174113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, V.; Lunghi, A. A machine-learning framework for accelerating spin-lattice relaxation simulations. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaverkin, V.; Netz, J.; Zills, F.; Köhn, A.; Kästner, J. Thermally Averaged Magnetic Anisotropy Tensors via Machine Learning Based on Gaussian Moments. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleis, L.; Shivaram, B.S.; Balachandran, P.V. Machine learning guided design of single-molecule magnets for magnetocaloric applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 222404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, A.; Sanvito, S. Computational design of magnetic molecules and their environment using quantum chemistry, machine learning and multiscale simulations. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangoulis, L.; Khatibi, Z.; Mariano, L.A.; Lunghi, A. Generating New Coordination Compounds via Multireference Simulations, Genetic Algorithms, and Machine Learning: The Case of Co(II) and Dy(III) Molecular Magnets. JACS Au 2025, 5, 3808–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandgaard, M.; Linjordet, T.; Kneiding, H.; Burnage, A.L.; Nova, A.; Jensen, J.H.; Balcells, D. A Deep Generative Model for the Inverse Design of Transition Metal Ligands and Complexes. JACS Au 2025, 5, 2294–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunghi, A.; Sanvito, S. Surfing Multiple Conformation-Property Landscapes via Machine Learning: Designing Single-Ion Magnetic Anisotropy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 5802–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, M.; Ganyushin, D.; Sivalingam, K.; Neese, F. A Modern First-Principles View on Ligand Field Theory Through the Eyes of Correlated Multireference Wavefunctions. In Molecular Electronic Structures of Transition Metal Complexes II; Mingos, D.M.P., Day, P., Dahl, J.P., Eds.; Structure and Bonding; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 143, pp. 149–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Eng, J.; Atanasov, M.; Neese, F. Covalency and chemical bonding in transition metal complexes: An ab initio based ligand field perspective. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 344, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Sharma, T.; Sarkar, A.; Rajaraman, G. Ab Initio Modelling of Lanthanide-Based Molecular Magnets: Where to from Here? In Computational Modelling of Molecular Nanomagnets; Rajaraman, G., Ed.; Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 34, pp. 291–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Atanasov, M.; Neese, F. Ab Initio Ligand-Field Theory Analysis and Covalency Trends in Actinide and Lanthanide Free Ions and Octahedral Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8802–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Islam, M.A.; Pecoraro, V.L.; Mallah, T.; Berthon, C.; Bolvin, H. Derivation of Lanthanide Series Crystal Field Parameters From First Principles. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15112–15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Singh, M.K.; Rajaraman, G. Role of Ab Initio Calculations in the Design and Development of Lanthanide Based Single Molecule Magnets. In Organometallic Magnets; Chandrasekhar, V., Pointillart, F., Eds.; Topics in Organometallic Chemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 64, pp. 281–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, A.; Sarkar, A.; Rajaraman, G. Role of Ab Initio Calculations in the Design and Development of Organometallic Lanthanide-Based Single-Molecule Magnets. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 4056–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soncini, A.; Piccardo, M. Ab initio non-covalent crystal field theory for lanthanide complexes: A multiconfigurational non-orthogonal group function approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 18915–18930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Mixture Density Networks; Technical Report; Aston University: Birmingham, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jha, D.; Paul, A.; Liao, W.k.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A. Generative Adversarial Networks and Mixture Density Networks-Based Inverse Modeling for Microstructural Materials Design. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2022, 11, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jha, D.; Paul, A.; Liao, W.-K.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A. A General Framework Combining Generative Adversarial Networks and Mixture Density Networks for Inverse Modeling in Microstructural Materials Design. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardizzone, L.; Kruse, J.; Wirkert, S.; Rahner, D.; Pellegrini, E.W.; Klessen, R.S.; Maier-Hein, L.; Rother, C.; Köthe, U. Analyzing Inverse Problems with Invertible Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2018), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.; Kim, J.; McCann, M.T.; Klasky, M.L.; Ye, J.C. Diffusion Posterior Sampling for General Noisy Inverse Problems. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Daras, G.; Chung, H.; Lai, C.H.; Mitsufuji, Y.; Ye, J.C.; Milanfar, P.; Dimakis, A.G.; Delbracio, M. A Survey on Diffusion Models for Inverse Problems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Andrejevic, N.; Drucker, N.C.; Nguyen, T.; Xian, R.P.; Smidt, T.; Wang, Y.; Ernstorfer, R.; Tennant, D.A.; Chan, M.; et al. Machine learning on neutron and X-ray scattering and spectroscopies. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2021, 2, 031301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, A.M.; Alan Tennant, D. Machine learning for magnetic phase diagrams and inverse scattering problems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2021, 34, 044002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarakoon, A.; Tennant, D.A.; Ye, F.; Zhang, Q.; Grigera, S.A. Integration of machine learning with neutron scattering for the Hamiltonian tuning of spin ice under pressure. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, A.M.; Laurell, P.; Balz, C.; Banerjee, A.; Lampen-Kelley, P.; Mandrus, D.; Nagler, S.E.; Okamoto, S.; Tennant, D.A. Extraction of interaction parameters for -RuCl_3 from neutron data using machine learning. Phys. Rev. Res. 2022, 4, L022061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wu, G.; Pajerowski, D.M.; Stone, M.B.; Savici, A.T.; Li, M.; Ramirez-Cuesta, A.J. Direct prediction of inelastic neutron scattering spectra from the crystal structure*. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. Machine learning in neutron scattering data analysis. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2024, 17, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Mutschler, J.; Waldmann, O. Determination of ligand field parameters of single-molecule magnets from magnetic susceptibility using deep learning based inverse models. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 064403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Mereacre, V.; Anson, C.E.; Powell, A.K. Butterfly M2IIIEr2 (MIII = Fe and Al) SMMs: Synthesis, Characterization, and Magnetic Properties. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6360–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]