Abstract

The increasing energy crisis demands sustainable functional materials. Wood, with its natural three-dimensional porous structure, offers an ideal renewable template. This study demonstrates that microstructural engineering of wood is a decisive strategy for enhancing magnetothermal conversion. Using eucalyptus wood, we precisely tailored its pore architecture via delignification and synthesized Fe3O4 nanoparticles in situ through coprecipitation. We systematically investigated the effects of delignification and precursor immersion time (24, 48, 72 h) on the loading, distribution, and magnetothermal performance of the composites. Delignification drastically increased wood porosity, raising the Fe3O4 loading capacity from ~5–6% (in non-delignified wood) to over 14%. Immersion time critically influenced nanoparticle distribution: 48 h achieved optimal deep penetration and uniformity, whereas extended time (72 h) induced minor local agglomeration. The optimized composite (MDW-48) achieved an equilibrium temperature of 51.2 °C under a low alternating magnetic field (0.06 mT, 35 kHz), corresponding to a temperature rise (ΔT) > 24 °C and a Specific Loss Power (SLP) of 1.31W·g−1. This performance surpasses that of the 24 h sample (47 °C, SLP = 1.16 W·g−1) and rivals other bio-based magnetic systems. This work establishes a clear microstructure–property relationship: delignification enables high loading, while controlled impregnation tunes distribution uniformity, both directly governing magnetothermal efficiency. Our findings highlight delignified magnetic wood as a robust, sustainable platform for efficient low-field magnetothermal conversion, with promising potential in low-carbon thermal management.

1. Introduction

The increasingly severe global energy crisis is driving an urgent search for sustainable materials derived from renewable resources. Among these, wood—a naturally occurring three-dimensional scaffold that is abundant, lightweight, and possesses excellent mechanical properties—has demonstrated immense potential [1]. By integrating inorganic nanomaterials into its unique multi-scale pore structure, functionalization research on wood has opened new avenues for developing advanced composite materials [2]. Specifically, the incorporation of magnetic elements—such as Fe, O, NdFeB, and others—has given rise to wood-based magnetic composites, elevating natural timber into advanced functional materials suitable for modern applications.

Magnetic nanoparticles have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their unique magnetocaloric effect (also known as the magnetocaloric phenomenon) [3]. First proposed by J. C. Maxwell in the 19th century, this effect describes the significant temperature change in materials caused by magnetic moment rearrangement under an applied alternating magnetic field [4]. Based on this principle, magnetic nanoparticles enable efficient conversion of magnetic energy into thermal energy [5], demonstrating application value in biomedicine [6,7,8,9,10], magnetic refrigeration [11,12,13,14,15], and smart electronic devices [16,17].

However, the realization of these applications heavily relies on the development of high-performance magnetocaloric materials. Magnetic nanoparticles still face multiple challenges in practical applications, including biocompatibility, colloidal stability, agglomeration, and sustainability [18,19,20,21,22]. To overcome these limitations, an effective strategy is to composite them with functional matrices to construct structurally stable, functionally integrated composite systems [23]. Researchers have attempted to composite magnetic components like Fe3O4 and Co with carbon-based materials (e.g., expanded graphite, carbon nanotubes) [24,25,26] and phase-change matrices (e.g., SA, PEG) [27,28,29], successfully developing multifunctional composites with high-efficiency photothermal/magnetothermal synergistic conversion capabilities and excellent cycling stability. These efforts validate the feasibility of the composite strategy for enhancing the comprehensive performance of magnetothermal materials.

Among various matrix options, wood offers an ideal carrier for efficient magnetothermal conversion and thermal energy storage due to its inherent three-dimensional interconnected porous framework, excellent mechanical properties, renewability, and tunable interfacial characteristics [30]. Research indicates that incorporating magnetic nanoparticles like Fe3O4 with phase-change media such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and tetradecanol into porous wood-based substrates—including delignified wood and carbonized wood powder—enables the construction of multifunctional composite systems. These materials exhibit high phase-change enthalpy, outstanding cycling stability, and significant magnetothermal temperature rise [31,32]. They demonstrate broad application prospects in building energy efficiency, human comfort regulation, and sustainable thermal energy management [33,34].

In summary, wood-based magnetic composites ingeniously integrate the structural advantages of natural wood with the functional properties of magnetic nanoparticles, opening new avenues for developing sustainable, high-performance magnetocaloric devices. However, systematic research on the magnetothermal conversion of such materials remains relatively scarce. In particular, the structure–property relationship between their magnetothermal conversion performance and the microstructure of wood, the loading amount of magnetic nanoparticles, and their distribution morphology remains unclear. This significantly limits further optimization of their performance and the precise exploration of application scenarios.

Therefore, by elucidating the fundamental structure–property relationship between wood microstructure, magnetic nanoparticle distribution, and magnetothermal conversion efficiency, the microstructurally engineered composite developed in this study presents a sustainable and high-performance material platform. This delignified wood-based composite not only offers a scalable and eco-friendly fabrication pathway but also demonstrates significant potential for industrial applications—such as in low-carbon building materials for interior heating, localized thermal therapy devices in biomedicine, or energy-management components in smart furniture and packaging—due to its integrated biocompatibility, structural robustness, and efficient energy conversion. Thus, this work provides both valuable scientific insights for the field of magnetic composite chemistry and engineering and a practical strategy to address the dual demands of efficiency and sustainability in next-generation thermal management systems.

Figure 1 shows the experimental flowchart. Addressing this research gap, this study aims to systematically investigate magnetothermal conversion performance of wood-based magnetic composites, focusing on revealing the structure–property relationship governing their magnetothermal conversion efficiency. To achieve this, we employed a simple in situ synthesis method to generate Fe3O4 nanoparticles within eucalyptus wood samples. The porous structure of the wood template was precisely controlled through a delignification process. We thoroughly investigated the effects of impregnation time in the precursor solution (24, 48, and 72 h) on the loading capacity and distribution morphology of the magnetic phase. Additionally, the role of subsequent densification treatment on the structure and properties of the composite materials was evaluated. The magnetothermal conversion capabilities of all prepared composites were quantitatively assessed using a custom-built alternating magnetic field apparatus.

Figure 1.

Experimental flowchart.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Material

This experiment utilized eucalyptus wood with dimensions of 40 mm × 50 mm × 2 mm (length × width × height) as the initial material, and the eucalyptus wood was provided by Zhejiang Shenghua Yunfeng Greeneo Co., Ltd. (Huzhou, China). The eucalyptus blocks were placed in distilled water for 30 min of ultrasonic cleaning and then dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 48 h. Experimental reagents Na2SO3, NaOH, FeSO4·7H2O, and FeCl3·6H2O were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Deionized water was prepared in the laboratory for experimental use.

2.2. Preparation of Delgified Wood

De-lignify the eucalyptus wood. Weigh 15 g of Na2SO3 and dissolve it in 150 mL of deionized water to form a 10% Na2SO3 solution. Weigh 0.6 g of NaOH and dissolve it in 150 mL of deionized water to form a 0.1 M NaOH solution. Place the eucalyptus wood sample into the reaction vessel. Add 150 mL of the 10% Na2SO3 solution to the reaction vessel, ensuring the sample is fully submerged. Add 150 mL of the 0.1 M NaOH solution to achieve a 1:1 volume ratio with the Na2SO3 solution. Heat the reaction vessel to 90 °C and maintain this temperature while stirring continuously for 4–6 h. Ensure the wood sample remains fully submerged in the solution throughout. After processing, remove the wood sample from the solution and rinse thoroughly with copious amounts of deionized water to remove residual chemicals. Place the wood samples in a well-ventilated area to air-dry naturally, or dry them in an oven at a low temperature (<60 °C) until completely dry. This yields delignified eucalyptus samples (DW). A separate portion of undelignified eucalyptus samples was washed and dried. This ensures that the eucalyptus samples are thoroughly delignified and suitable for subsequent magnetic composite preparation.

2.3. Preparation of Wood-Based Magnetic Composites

Prepare the FeSO4-FeCl3 precursor solution. Prepare 100 mL of a mixed solution containing 0.5 mol/L FeSO4·7H2O and 0.5 mol/L FeCl3·6H2O in a 2:1 ratio. Stir the solution using a magnetic stirrer to ensure complete dissolution. Immerse delignified and undelignified eucalyptus wood samples into the solution. After thorough wetting, impregnate them at room temperature and atmospheric pressure for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively. After immersion in the precursor solution, thoroughly rinse the samples with deionized water. Then, hydrolyze them in a 1 mol/L NaOH solution for 24 h. Finally, rinse thoroughly with deionized water until the system is neutralized. Dry the samples in a 50 °C oven to obtain magnetic Fe3O4 wood-based composites (MDW and MW). As shown in Table 1 below, eight sets of samples were prepared under different conditions based on lignin removal status and precursor solution immersion time.

Table 1.

Treatment conditions of different samples and Fe3O4 loading rates.

Among them, the loading rate of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on wood is calculated using the following formula:

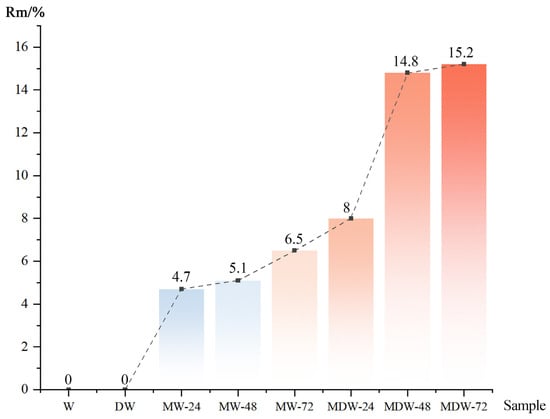

Rm is the loading rate of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the wood, Wm is the weight of the magnetic wood, and Wn refers to the weight of the wood sample before treatment. Treatment conditions of different samples and Fe3O4 loading rates are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Fe3O4 loading rates of different samples.

2.4. Compaction Treatment

The compaction (hot-pressing) treatment is a common process in advanced wood manufacturing, known to significantly enhance the density and mechanical properties of wood-based materials [35,36,37,38]. Therefore, in this study, a standard hot-pressing treatment was applied as the integral final step in fabricating all wood-based magnetic composites, aiming to produce structurally robust samples suitable for practical applications.

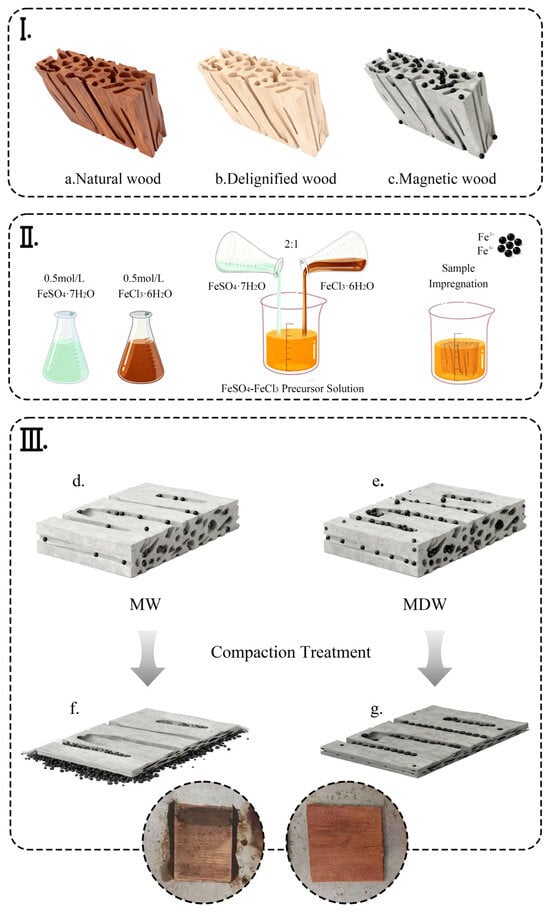

Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the preparation process: Panel I presents the morphology of natural eucalyptus wood (W), delignified eucalyptus wood (DW), and magnetic eucalyptus wood (MDW) after impregnation with the precursor solution; Panel II illustrates the preparation of the precursor solution and the impregnation process; Panel III highlights a critical divergence observed after the compaction treatment among different sample groups.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the preparation process of magnetic wood. (I) Morphology evolution. (II) Preparation and impregnation of the Fe3+/Fe2+ precursor solution (molar ratio 2:1). (III) Demonstrates the differences between sample groups after compaction treatment: d—non-delignified magnetic wood (MW), e—delignified magnetic wood (MDW); after compaction, f—MW with severe structural failure and magnetic particle overflow, g—MDW with intact structure (the insets are physical photos of the corresponding compacted samples).

However, a clear distinction was observed upon compaction: samples from the non-delignified magnetic wood group (MW) exhibited severe structural failure upon compaction. Specifically, the Fe3O4 nanoparticles, which were predominantly surface-adhered due to the impeded penetration caused by the dense lignin network, were extensively extruded under the combined heat and pressure. This resulted in visible material overflow and a highly inhomogeneous distribution of the magnetic phase. Consequently, the compacted MW samples were deemed unsuitable for reliable and representative magnetothermal performance evaluation and were excluded from the subsequent quantitative analysis.

This stark contrast powerfully underscores the pivotal role of delignification. The process creates an open, permeable cellulose framework that not only facilitates deep and uniform loading of Fe3O4 nanoparticles but also confers sufficient structural integrity to withstand standard densification processes without functional degradation. The following sections, therefore, focus on the characterization and performance evaluation of the delignified magnetic wood composites (MDW series), which successfully integrate enhanced magnetic functionality with the structural benefits of compaction.

2.5. Characterization

Using a high-resolution scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300, Oberkochen, Germany), observe the surface and cross-sectional structures of different samples. Pay particular attention to the distribution of magnetic nanoparticles within the wood fiber and pore structures, evaluating particle uniformity and fixation. Employ X-ray diffraction (XRD, Ultima IV combined multifunctional horizontal X-ray diffractometer, Tokyo, Japan) technology to determine the crystal structure of magnetic nanoparticles in various samples.

2.6. Magnetothermal Conversion Experiment

A homemade magnetothermic device was constructed using a 2 mm copper wire coil and a resonant PLC circuit to generate a constant alternating magnetic field for measuring the magnetothermal conversion performance in magnetic wood. During the experiment, wood samples were excited under a magnetic field frequency of 35 kHz, with a magnetic field strength of 0.06 mT, a coil diameter of 35 mm, a voltage of 12 V, and a current of 5 A. An infrared thermal imager (FLIR, Jasco 4600 instrument, Tokyo, Japan) was employed to record real-time changes in the wood surface temperature. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results, each magnetothermal test was performed twice on independent samples from the same batch, with an interval of 5 days between measurements. The reported temperature profiles and derived parameters are the averages of these two highly concordant runs.

The magnetothermal conversion efficiency was quantitatively evaluated by calculating the Specific Loss Power (SLP).

C: The specific heat capacity of the wood-based sample. A value of 1.7 J·g−1·°C−1, characteristic of dry wood, was adopted for the composite [32].

m: The mass of the wood sample.

mnp: The total mass of the magnetic nanoparticles loaded on the wood (g).

/: The initial linear heating rate was determined from the slope of the linear regression fit applied to the temperature–time data within a stable linear heating period (30–120 s after magnetic field activation). This period was selected to avoid any initial transient response and ensure excellent linearity (R2 > 0.99 for all samples).

3. Results

3.1. Morphological and Structural Characteristics of Magnetic Wood

Figure 4 displays structural characterization images of W, DW, and MDW samples at 24–72 h. As shown in Figure 4a, the SEM image of untreated natural eucalyptus wood (W) clearly reveals the wood’s porous structure. The cell walls and middle lamellae of the wood cells appear largely intact, with most vessel walls tightly integrated.

Figure 4.

Structural characterization of wood-based magnetic composites. (a) Natural wood (W). (b) Delignified wood (DW). (c–e) Magnetic wood (MDW) after 24, 48, and 72 h of impregnation.

As shown in Figure 4b, the SEM image depicts the delignified eucalyptus sample (DW). Comparing the photographs reveals the appearance of numerous gaps and a distinctly roughened, delaminated texture on the radial cross-section. This occurs because wood cell walls are primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Delignification disrupts the structural stability of lignin, causing it to dissociate and dissolve from the cellulose and hemicellulose network [1]. Consequently, the porosity of the wood structure increases significantly, pore sizes enlarge, cell cavities expand, and some cell walls collapse or fracture, resulting in uneven grooves and microfibril bundles on the surface. This provides additional anchoring sites and diffusion pathways for subsequent Fe3O4 nanoparticle loading.

As shown in Figure 4c–e, SEM images of MDW-24, MDW-48, and MDW-72 after in situ coprecipitation reveal that Fe3O4 adsorption within the MDW series markedly increases with prolonged impregnation time (24 h → 72 h). This occurs because, within a short timeframe (24 h), ion diffusion dominates, leading particles to preferentially load onto surfaces and macropores. As time extends (48 h), deeper pores are progressively filled, and particle size tends toward uniformity. However, excessive prolongation may cause particles to clog pores (local agglomeration observed in MDW-72, Figure 4e). In summary, delignification treatment significantly enhances Fe3O4 nanoparticle loading efficiency and distribution uniformity by optimizing wood microstructure and surface chemistry, while impregnation time further optimizes loading capacity by regulating ion penetration depth.

3.2. Wood-Crystal Structure and Chemical Composition

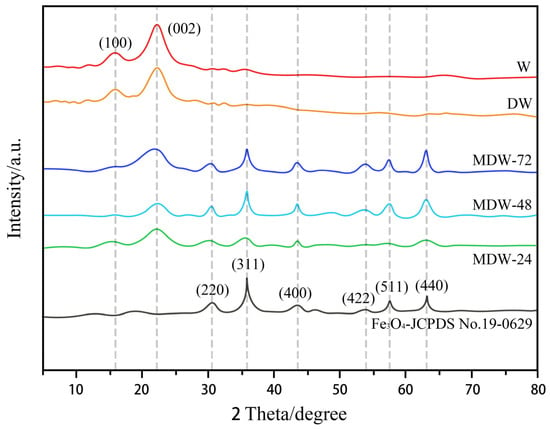

The crystal structure of the experimental samples was tested using XRD. Figure 5 shows the XRD patterns of W, DW, and MDW-24~72. The characteristic peaks at 15.6° and 22.4° in the W pattern correspond to the (100) and (002) crystallographic planes of cellulose. The DW pattern matches W’s characteristic peaks, confirming that delignification does not alter the crystallographic structure of the eucalyptus sample. The XRD pattern of Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibits characteristic peaks at 30.1°, 35.4°, 43.1°, 53.4°, 56.9°, and 62.5°, corresponding to the (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440) crystal planes, consistent with the pdf standard card for magnetite (JCPDS NO.19-0629).

Figure 5.

XRD of Fe3O4 and experimental samples under different treatment conditions.

The characteristic peaks in the MDW24~72 h pattern curve, in addition to those corresponding to cellulose crystal planes, also exhibit six additional peaks matching the Fe3O4 nanoparticle pattern, confirming the successful synthesis of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles in the MDW-24~72 samples. Furthermore, MDW-48 and MDW-72 exhibit more pronounced characteristic peaks compared to MDW-24, indicating that the Fe3O4 loading in MDW-48 and MDW-72 is greater than that in MDW-24.

The average crystallite size of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles within the magnetic wood composites was estimated from X-ray diffraction (XRD) data. Using the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most intense (311) diffraction peak of Fe3O4 in the XRD pattern, the Scherrer equation is presented as follows:

Here, D represents the average crystallite diameter, K is the shape factor (taken as 0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (0.15406 nm), β is the FWHM of the diffraction peak (in radians), and θ is the Bragg diffraction angle. The calculated average crystallite size of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles is approximately 12.8 nm.

3.3. Magnetic Properties of the Composites

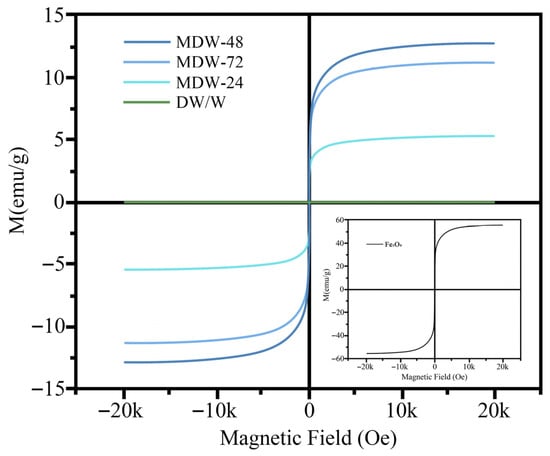

To quantitatively evaluate the distribution of the magnetic phase and corroborate the successful loading of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, the magnetic properties of representative samples were characterized using a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) at room temperature.

As shown in Figure 6, all MDW samples exhibit typical ferrimagnetic hysteresis loops, whereas native wood (W) and delignified wood (DW) show only negligible diamagnetic responses, confirming that the magnetization originates solely from the incorporated Fe3O4 phase. Furthermore, all MDW samples display low coercivity and negligible remanence, indicating that the embedded Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibit near-superparamagnetic behavior at room temperature—a property favorable for efficient magnetothermal conversion via Néel relaxation.

Figure 6.

VSM analysis of the composites.

A clear trend is observed in the saturation magnetization (Ms) values: MDW-48 exhibits the highest Ms (12.8 emu/g), followed by MDW-72 (11.9 emu/g) and MDW-24 (5.2 emu/g). This progression aligns closely with the gravimetrically determined Fe3O4 loading rates (Rm, Table 1). Such a strong positive correlation provides direct magnetic evidence that the Fe3O4 nanoparticles are distributed throughout the bulk volume of the wood matrix rather than merely deposited on the surface. The highest Ms of MDW-48 corresponds to its optimal nanoparticle loading and uniform distribution, as observed in SEM images (Figure 4d). The slightly lower Ms of MDW-72 is consistent with the localized agglomeration noted in SEM (Figure 4e), which may reduce the effective magnetic moment per unit mass due to inter-particle interactions.

In summary, the VSM results not only confirm the successful integration of magnetic nanoparticles but also establish a direct microstructure–magnetic property relationship, where improved nanoparticle loading and distribution uniformity lead to enhanced magnetic response—a key factor underpinning the magnetothermal performance discussed in the following section.

3.4. Magnetothermal Conversion Properties of Wood

3.4.1. Magnetothermal Performance and Macroscopic Heating Behavior

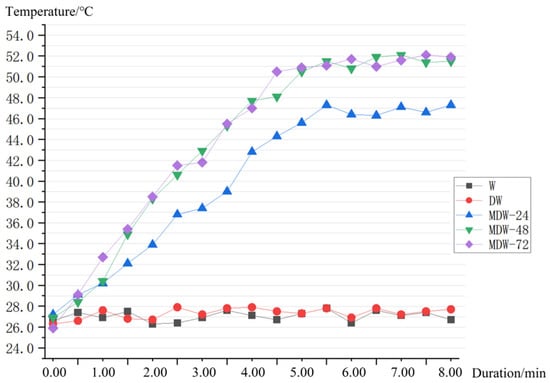

The author’s self-made alternating magnetic field magnetocaloric testing device is used to determine the magnetothermal conversion performance of the sample [34]. The alternating magnetic field works at a frequency of 35 kHz, with a magnetic flux density of 0.06 mT and a current of 5 A. The experimentally prepared wood-based magnetic materials are placed in the device. The surface temperature changes in the wood-based magnetic materials are measured using an infrared thermal imager, thereby calculating their magnetothermal conversion efficiency. To assess the reproducibility and stability of the measurement, each sample underwent two independent tests with a 5-day interval between runs. The data presented in Figure 7 and Table 2 represent the average of these two highly consistent measurements. Figure 7 and Table 2 show the temperature change in the wood-based magnetic samples DW and MDW-24~72 after being subjected to an alternating magnetic field for 8 min.

Figure 7.

Temperature change curves of the wood-based magnetic samples DW, MDW-24~72.

Table 2.

Temperature changes in the wood-based magnetic samples DW, MDW-24, MDW-48, and MDW-72.

The surface temperature of sample W and DW remained consistently between 26 °C and 27 °C over time. This demonstrates that untreated wood, not impregnated with the reaction solution, exhibits no magnetothermal conversion performance under a 35 kHz alternating magnetic field.

Samples MDW-24, MDW-48, and MDW-72 exhibit a rapid temperature rise over time, stabilizing at approximately 5 min and 30 s. This demonstrates that wood-based magnetic materials immersed in the reaction solution exhibit strong magnetothermal conversion performance under a 35kHz alternating magnetic field.

The average peak temperature for sample MDW-24 was 47 °C, while samples MDW-48 and MDW-72 reached an average peak temperature of approximately 51.2 °C. This demonstrates that the magnetothermal conversion performance of wood-based magnetic materials correlates with the immersion duration in the reaction solution during testing. Longer immersion periods increase the loading rate of Fe3O4 nanoparticles within the material, thereby enhancing its magnetothermal conversion performance. Furthermore, after 48 h of immersion, the Fe3O4 nanoparticle loading rate in the wood-based magnetic material essentially reaches saturation, leading to a stable magnetothermal conversion performance. The high reproducibility of the heating profiles between the two independent tests confirms the robustness of the experimental data and indicates the short-term stability of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles within the wood matrix. No performance degradation was observed between the tests, suggesting that the in situ synthesized nanoparticles are effectively anchored in the delignified cellulose framework.

3.4.2. Quantitative Analysis of Magnetothermal Conversion Efficiency

To enable direct comparison with other magnetothermal material systems, the Specific Loss Power (SLP) was calculated for the MDW series. The key parameters and results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The SLP values of the magnetic wood composites.

As shown in Table 3, MDW-48 exhibits the highest SLP value (1.31 W·g−1), which correlates directly with its highest Fe3O4 loading (14.8%) and the most uniform nanoparticle distribution observed in SEM images (Figure 4d). A high and uniform loading ensures maximum utilization of nanoparticles for efficient magnetothermal conversion under the alternating magnetic field. The SLP of MDW-72 (1.26 W·g−1) is slightly lower, consistent with the incipient local agglomeration of nanoparticles (Figure 4e), which may reduce effective magnetic relaxation losses. MDW-24 shows the lowest SLP (1.16 W·g−1), in agreement with its lowest loading rate (8.0%) and shallower particle penetration.

This quantitative SLP trend—MDW-48 ≈ MDW-72 > MDW-24—is fully consistent with the observed macroscopic equilibrium temperatures (Figure 6) and the microstructural characterization. It provides conclusive evidence, from the perspective of energy conversion rate, that engineering the wood template through delignification to create an open porous structure, combined with an optimal 48 h impregnation duration, is the key to achieving the highest magnetothermal conversion performance.

4. Conclusions

This work successfully demonstrates a microstructure-driven strategy for transforming natural wood into an efficient magnetothermal material. The key lies in the sequential engineering of its porous architecture: delignification opens the internal wood network, while controlled impregnation time (48 h) ensures optimal Fe3O4 nanoparticle loading and distribution. This two-step process results in composites where the magnetic phase is uniformly embedded within the wood bulk, as confirmed by cross-sectional SEM, VSM, and magnetothermal analysis. The established structure–property relationship is clear: samples with higher and more homogeneous nanoparticle loading (notably MDW-48) exhibit stronger magnetic response and superior magnetothermal conversion efficiency under low-field conditions. The excellent reproducibility of the heating profiles further attests to the stability of the composite. Beyond presenting a high-performance material, this study provides a generalizable and sustainable fabrication route that leverages the innate structure of wood. The proposed magnetic wood composite thus emerges as a promising, eco-friendly platform for thermal management applications, showcasing how green process engineering can unlock advanced functionalities in renewable biomass.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; methodology, C.C. and Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, W.X.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, W.X.; project administration, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32571962).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Chen Chen is a postdoctoral fellow in a joint program with Zhejiang Shenghua Yunfeng Greeneo Co., Ltd., which supplied the eucalyptus wood. Yuxi Lin is employed by Zhejiang Shenghua Yunfeng Greeneo Co., Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Xiong, X.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, M. Current situation and key manufacturing considerations of green furniture in China A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 121957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, R.; Kristak, L.; Antov, P. Advanced eco-friendly wood-based composites. Materials 2022, 15, 8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starsich, F.H.; Eberhardt, C.; Boss, A.; Hirt, A.M.; Pratsinis, S.E. Coercivity determines magnetic particle heating. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1800287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.C. A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1865, 155, 459–512. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, W. Cyclopedia of the Physical Sciences; Thomson, J.P., Ed.; Richard Green and Company: London, UK, 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Yanase, M.; Shinkai, M.; Honda, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Yoshida, J.; Kobayashi, T. Intracellular hyperthermia for cancer using magnetite cationic liposomes: An in vivo study. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1998, 89, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavilán, H.; Avugadda, S.K.; Fernández-Cabada, T.; Soni, N.; Cassani, M.; Mai, B.T.; Chantrell, R.; Pellegrino, T. Magnetic nanoparticles and clusters for magnetic hyperthermia: Optimizing their heat performance and developing combinatorial therapies to tackle cancer. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11614–11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic nanoparticle heating and heat transfer on a microscale: Basic principles, realities and physical limitations of hyperthermia for tumour therapy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.R.; Weissleder, R. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for targeted imaging and therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, M.R.; Adams, C.F.; Chari, D.M. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Mediated Gene Delivery to Two-and Three-Dimensional Neural Stem Cell Cultures: Magnet-Assisted Transfection and Multifection Approaches to Enhance Outcomes. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2017, 40, 2D.19.1–2D.19.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debye, P. Einige bemerkungen zur magnetisierung bei tiefer temperatur. Ann. Phys. 1926, 386, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, W.F. A thermodynamic treatment of certain magnetic effects. A proposed method of producing temperatures considerably below 1 absolute. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1927, 49, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, V.; Blázquez, J.; Ingale, B.; Conde, A. The magnetocaloric effect and magnetic refrigeration near room temperature: Materials and models. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2012, 42, 305–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschneidner, K.A.; Pecharsky, V.K.; Tsokol, A.O. Recent developments in magnetocaloric materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, J.H.; Pires, A.L.; Araujo, J.P.; Pereira, A.M. Magnetocaloric materials: From micro-to nanoscale. J. Mater. Res. 2019, 34, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Parada, G.A.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaax7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challener, W.A.; Peng, C.; Itagi, A.V.; Karns, D.; Peng, W.; Peng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, X.; Gokemeijer, N.J.; Hsia, Y.-T.; et al. Heat-assisted magnetic recording by a near-field transducer with efficient optical energy transfer. Nat. Photonics 2009, 3, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, P.; Di Corato, R.; Lartigue, L.; Wilhelm, C.; Espinosa, A.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Gazeau, F.; Manna, L.; Pellegrino, T. Water-soluble iron oxide nanocubes with high values of specific absorption rate for cancer cell hyperthermia treatment. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3080–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, L.H.; Arias, J.L.; Nicolas, J.; Couvreur, P. Magnetic nanoparticles: Design and characterization, toxicity and biocompatibility, pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5818–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.L.; Fu, Y.C. Formation of Chitosan/Sodium Phytate/Nano-Fe3O4 Magnetic Coatings on Wood Surfaces via Layer-by-Layer Self-Assembly. Coatings 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waki, H.; Igarashi, H.; Honma, T. Estimation of effective permeability of magnetic composite materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 1520–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Thi, N.T.; Nho, N.T.; Hanh, L.T.; Tuan, H.N. A novel stearic acid/expanded graphite/Fe3O4 composite phase change material with effective photo/electro/magneto-triggered thermal conversion and storage for thermotherapy applications. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2024, 9, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaib, S.S.A.; Yuan, W. Hierarchical magnetic porous carbonized wood composite phase change materials for efficient solar-thermal, electrothermal, and magnetothermal conversion-storage. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Tie, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, P.; Jiang, Z.; Tie, S.; Wang, C. Photo-and magneto-responsive highly CNTs@ Fe3O4 Glauber’s salt based phase change composites for energy conversion and storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 286, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.; Yang, H.; Cao, G.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. Carbonized wood flour matrix with functional phase change material composite for magnetocaloric-assisted photothermal conversion and storage. Energy 2020, 202, 117636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, B.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sui, M.; Xie, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, H.; Lu, X.; Tong, Y. Cellulose nanofibrous/MXene aerogel encapsulated phase change composites with excellent thermal energy conversion and storage capacity. Energy 2023, 262, 125505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xue, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z. Economical cobalt metal organic framework derived magnetic porous carbon achieves high flow interfacial evaporator with excellent photothermal and magnetothermal conversion capacity. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 342, 120140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xiao, G.; Chen, J.; Fu, S. Wood nanotechnology: A more promising solution toward energy issues: A mini-review. Cellulose 2020, 27, 8513–8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chao, W.; Di, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, T.; Yu, Q.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Wang, C. Multifunctional wood based composite phase change materials for magnetic-thermal and solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 200, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Gao, L.; Xiao, S.; Gao, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhan, X. Magnetic wood as an effective induction heating material: Magnetocaloric effect and thermal insulation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1700777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Gu, K.; Han, S.; Cen, J.; Yu, Y.; Hou, J. Bifunctional wood-based phase change composites: Exceptional magnetothermal and photothermal conversion capabilities. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, Z.; Guo, H. Preparation of phase change Heat storage wood with in-situ generation of thermal conductive particles to improve photothermal conversion efficiency. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yue, K.; Qian, J.; Lu, D.; Wu, P.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z. Integrated approach for improving mechanical and high-temperature properties of fast-growing poplar wood using lignin-controlled treatment combined with densification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqrinawi, H.; Ahmed, B.; Wu, Q.; Lin, H.; Kameshwar, S.; Shayan, M. Effect of partial delignification and densification on chemical, morphological, and mechanical properties of wood: Structural property evolution. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 213, 118430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.G.; Liu, Y.; Konukcu, A.C. Study on withdrawal load resistance of screw in wood-based materials: Experimental and numerical. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 2084699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Xiong, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Mo, X. Effects of surface modification methods on mechanical and interfacial properties of high-density polyethylene-bonded wood veneer composites. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.