Abstract

A series of high-viscosity ferrofluids with variations in particle concentration and carrier liquid molecular weight were synthesized in a fluoroether oil base by the chemical coprecipitation method. The microstructure, surface coating, and magnetic properties of the nanoparticles were characterized, and the rheological properties of the corresponding ferrofluids were systematically investigated to elucidate their governing mechanisms and underlying mechanisms. The results indicate that the synthesized zinc-doped ferrite particles are spherical with a size of less than 50 nm and are chemically coated with a fluoroether acid. Moreover, the saturation magnetization of the ferrofluids increases with rising particle concentration. With the increase in particle concentration, the zero-field viscosity and shear stress of the ferrofluids increase significantly. The zero-field viscosity and shear yield stress of the ferrofluid increase significantly with the molecular weight of the carrier liquid, due to the strengthened entanglement of its molecular chains. At a carrier liquid molecular weight of 4600 g/mol, the 50 wt.% ferrofluid displayed a liquid character, in contrast to the gel-like character displayed by the 60 and 70 wt.% samples. The 60 wt.%-7480 g/mol sample demonstrated superior elasticity to its 60 wt.%-4600 g/mol counterpart. Furthermore, the application of a 100 mT magnetic field induced a transition from a liquid to a gel state in the 50 wt.%-4600 g/mol sample. This transition, driven by the formation of magnetic field-induced chain-like structures, significantly enhanced the magnetoviscous effect. This study provides the theoretical basis and experimental support for the development of high-viscosity ferrofluid sealing materials suitable for high-pressure, liquid environments and corrosive working conditions.

1. Introduction

Ferrofluids are stable colloidal suspensions consisting of magnetic nanoparticles, a carrier liquid, and surfactants [1]. Their properties can be tuned by an external magnetic field, under which they exhibit both liquid-like fluidity and solid-like magnetic behavior [2]. These unique characteristics enable their use in diverse applications, including sealing [3,4,5,6], lubrication [7], damping and vibration reduction [8], sensors [9,10], and micropumps [11,12,13].

The choice of carrier liquid largely dictates the application-specific performance of ferrofluids. For instance, silicone oil-based variants, with their temperature-insensitive viscosity, are ideal for extreme temperature environments [14]. Ionic liquid-based ferrofluids exhibit zero volatility, making them suitable for high-temperature applications [15]. Due to their exceptional shear stability, polyalphaolefin-based ferrofluids are well suited for lubrication and sealing [16]. Fluoroether oil-based ferrofluids offer resistance to high temperatures and corrosion, with their strong hydrophobicity enabling effective sealing in liquid environments [17,18].

The rheological properties of ferrofluids are a critical determinant of their performance in applications such as sealing resistance torque [19], vibration damping [20], heat transfer [21], and critical pressure resistance in aqueous environments [22]. Research has consistently identified several key factors governing these properties. For instance, Hosseini et al. [23] reported that viscosity increases with magnetic nanoparticle concentration due to enhanced interparticle interactions. The carrier liquid’s viscosity is equally influential, as demonstrated by Kim et al. [16], who found that ferrofluids prepared with high-viscosity PAO-60 exhibit significantly greater viscosity than those with PAO-30. External fields also play a major role; Wang et al. [24] observed that increasing magnetic field strength raises both static and dynamic yield stresses, while elevated temperature reduces the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli. Furthermore, the magnetic field can induce dramatic microstructural changes. Čampelj [25] described an aqueous ferrofluid that transitioned to a gel-like state at 50 mT and reverted to a liquid at 200 mT, a behavior attributed to particle agglomeration and sedimentation. Underlying these phenomena are field-induced structures: Zubarev et al. [26] revealed that the strong magnetoviscous effect at low shear rates stems from the formation of chain-like aggregates, a finding supported by Ivanov et al. [27], who linked the influence of large particles to internal inhomogeneities from magnetic dipole–dipole interactions. Finally, the stability of these structures is affected by the medium, with Li et al. [28] showing that a higher-viscosity carrier liquid fosters larger network structures and more stable particle dispersion. In summary, the rheology of ferrofluids is governed by a complex interplay of factors, including magnetic nanoparticle concentration, carrier liquid viscosity, temperature, and magnetic field strength.

Current efforts in developing high-viscosity ferrofluids have achieved limited success. For instance, Liu Li et al. [29] dispersed magnetic nanoparticles in PAO-4 and PAO-10 to produce ferrofluids with particle concentrations up to 37 wt.% and 30 wt.%, respectively, achieving zero-field viscosities of 3 Pa·s at room temperature. Similarly, Chuding Zhang et al. [30] synthesized a ferrofluid with a viscosity of 6 Pa·s by dispersing carbon nanotube-coated nanoparticles in PAO-20. While Liu [31] developed a high-concentration hydrophobic magnetite gel with a high saturation magnetization of 46.0 emu/g, it lacks fluidity in the absence of a field. Reported fluoroether oil-based ferrofluids, meanwhile, do not exceed a particle concentration of 50 wt.% and possess insufficient viscosity [32].

Furthermore, the choice of magnetic particles is crucial. Zinc ferrite (Zn ferrite) and its derivatives have emerged as promising alternatives due to their tunable magnetic properties and lower density. Wang et al. [33] demonstrated that ZnFe2O4 nanocrystal clusters yield magnetorheological (MR) fluids with a strong MR effect and superior sedimentation stability. Thirupathi et al. [34] also reported complex, field-dependent rheology in Mn-Zn ferrite nanofluids.

Despite these advances, a systematic understanding of systems combining ultra-high particle concentrations (>50 wt.%) with ultra-high-viscosity fluoroether oils remains lacking. To address this gap, we prepared a series of fluoroether oil-based ferrofluids with particle concentrations of 50, 60 and 70 wt.% using carrier liquid of molecular weights 4600 and 7480 g/mol. This work systematically investigates the effects of particle concentration, carrier liquid viscosity, and magnetic field strength on rheological properties, thereby providing fundamental insights and practical guidance for developing advanced high-viscosity ferrofluids.

2. Materials and Methods

Briefly, ferric chloride (FeCl3∙6H2O), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4∙7H2O), zinc chloride (ZnCl2), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were purchased from Alfa Aesar Chemical reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). PFPE oil (F-(C3F6O)n-C2F5, Mw = 4600 g/mol, 7480 g/mol) and PFPE acids (C3F7O-(C3F6O)n-C3F4O2H, Mw = 3800 g/mol) were purchased from Shanghai ICAN Chemical S&T Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without any further purification.

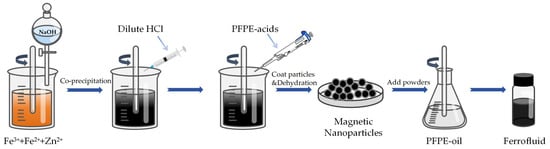

In a typical procedure, Zn ferrite nanoparticles (ZnxFe3−xO4, where the ratio of Zn2+, x, is 0.2) were synthesized via the chemical coprecipitation method, following these steps: First, 24 g of NaOH was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water to prepare the NaOH solution. In addition, 25.95 g of FeCl3·6H2O, 12.68 g of FeSO4·7H2O, and 1.78 g of ZnCl2·6H2O were dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water. The NaOH solution was added to the iron salt solution, and the reaction was conducted for 1 h at 70 °C with mechanical stirring at 400 rpm, and Zn ferrite nanoparticles were produced. Dilute hydrochloric acid was added dropwise to the reaction solution to adjust the pH to 6.5. Subsequently, 10 g of fluoroether acid was added dropwise for particle coating. The reaction was carried out for 1 h at 70 °C with mechanical stirring at 300 rpm. After the reaction, the particles were cleaned and separated using a magnetic separation method, followed by drying and grinding. The particles were weighed according to mass concentrations of 50, 60 and 70 wt.%, and then added to fluoroether oils with two different molecular weights (4600 g/mol and 7480 g/mol), respectively. A series of fluoroether oil-based ferrofluids were obtained via mechanical stirring. A schematic illustration of the preparation process of ferrofluid is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation process for the ferrofluids.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on a DX-2700X X-ray diffractometer (Haoyuan Instrument, Dandong, China) equipped with Cu Kα (λ = 0.154056 nm) radiation. Scans were performed from 10° to 80° at a rate of 0.085 deg./s. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired on JSM-6700 M (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). FTIR data were acquired using a Nicolet iS10 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer under the following test conditions: a resolution of 4 cm−1, scan rate of 20 scans per minute, and wavenumber range of 500–4000 cm−1. TGA data were obtained with a TG209F1 thermogravimetric analyzer. The test was conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a temperature range from 25 °C to 600 °C and a heating rate of 10 °C/min. A vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, Lake Shore 7410) (Lake Shore, Columbus, OH, USA) was used for the magnetic characterization of nanoparticles at an external magnetic field ranging from −2.0 × 104 to +2.0 × 104 Oe at 25 °C. The rheological properties of the PFPE oil-based ferrofluids were investigated using a rotational rheometer (MCR 301, Anton-Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria) equipped with a magnetic field module. A parallel plate system made of non-magnetic metal with a diameter of 20 mm was used, and the gap was set to 1 mm. Steady-state flow curves were measured in controlled shear rate (CSR) mode. The shear rate was logarithmically swept from 10−3 to 102 s−1. A critical aspect of the protocol was the data point acquisition time. To ensure that the measured shear stress represented a steady-state value and to mitigate elastic effects at low shear rates, the acquisition time at each point was set to be greater than or equal to the reciprocal of the applied shear rate. This ensures that the fluid is sheared for a sufficient number of strain units to achieve a steady flow, which is particularly important for characterizing yield stress fluids or fluids with significant viscoelasticity.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructures and Magnetic Properties

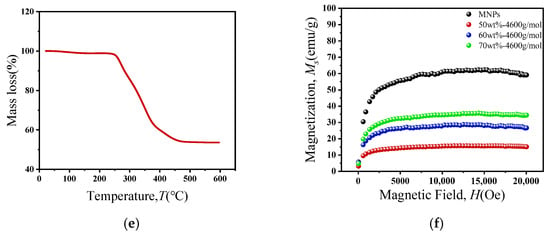

The microstructure and magnetic properties of the particles are shown in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows that the corresponding positions and relative intensities of the diffraction peaks of the powder are consistent with the cubic spinel structure [32]. Figure 2b reveals that the particles have an approximately spherical morphology with a particle size of less than 50 nm.

Figure 2.

Microstructures and magnetic properties of particles and the ferrofluid: (a) XRD, (b,c) SEM&EDS, (d) FTIR, (e) TGA, (f) VSM.

As indicated in Figure 2c, the particles are composed of Fe, Zn, and O elements, suggesting that Zn2+ has been doped into the ferrite particles. From Figure 2d, the diffraction peaks at 1238.1 cm−1, 1134.0 cm−1, and 1307.5 cm−1 indicate the presence of C–F, –CF2, and –CF3 functional groups in the sample, respectively. The diffraction peak at 983.5 cm−1 confirms the existence of the C–O–C functional group. The diffraction peak for the C=O bond in PFPE acids is located at 1777.3 cm−1. After coating, this peak shifts to 1685.5 cm−1. This shift is caused by the chemical adsorption between the COOH group and the iron ions on the particle surface, confirming that PFPE acid is coated via chemical bonds [35]. As shown in Figure 2e, the mass of the sample decreases gradually with increasing temperature. When the temperature is lower than 280 °C, the mass reduction is slight, which is attributed to the evaporation of a small amount of water. In the temperature range of 280–480 °C, the particles undergo a mass loss of approximately 45 wt.%, resulting from the decomposition of PFPE acids coated on the particle surface. As the temperature continues to rise to 600 °C, no further change in the particle mass is observed [36]. From Figure 2f, it can be seen that with the increase in magnetic field strength, the saturation magnetization of the particles initially increases rapidly and then saturates. The magnetization curve of the particles shows that their specific saturation magnetization is 61.93 emu/g [23]. The magnetization curves of the ferrofluids are similar to that of the particles; the specific saturation magnetizations of the three ferrofluids (50 wt.%-4600 g/mol, 60 wt.%-4600 g/mol and 70 wt.%-4600 g/mol) are 15.47 emu/g, 28.40 emu/g and 35.52 emu/g, respectively.

3.2. The Effect of Particle Concentration on the Rheological Properties of the Ferrofluids

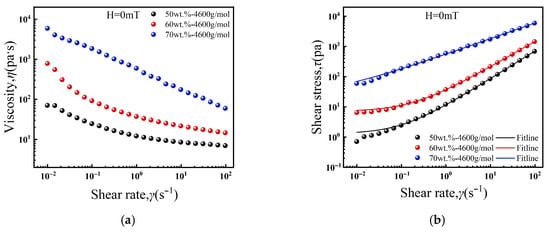

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of particle concentration on the rheological properties of the ferrofluids in the absence of a magnetic field. As shown in Figure 3a, all samples exhibit typical shear-thinning behavior, where the viscosity gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes with increasing shear rate. This is attributed to the rotation, displacement, and progressive alignment of the magnetic nanoparticles and their aggregates in the direction of shear [36]. Furthermore, at a constant carrier liquid molecular weight, the entire viscosity curve shifts upward as the particle concentration increases, leading to higher zero-field viscosity (η0). This increase results from reduced interparticle spacing. The smaller spacing enhances magnetic dipole–dipole interactions, which in turn raises the internal frictional resistance within the samples [37].

Figure 3.

Effect of particle concentration on the rheological properties of ferrofluids under zero magnetic field: (a) viscosity curves, (b) shear curves.

Figure 3b reveals that the shear stress–shear rate curves for all samples deviate from linearity, confirming their non-Newtonian behavior. To further quantify the yield characteristics under zero magnetic field, the flow curves were fitted with the Herschel–Bulkley model, given by Equation (1).

In the equation, τ is the shear stress, γ is the shear rate, τ0 is the yield stress, k is the consistency coefficient, and n is the power law index. The fitted parameters are listed in Table 1. As summarized in Table 1, the yield stress (τ0) increases markedly with particle concentration. This trend is caused by significantly stronger interparticle interactions, which include magnetic dipole–dipole forces, van der Waals forces, and steric hindrance. These interactions intensify as the interparticle spacing decreases [38]. The observed behavior can be explained by the underlying microstructural evolution. At 50 wt.%, weak interactions form only loose, local aggregates, which shear can easily disrupt. At 60 wt.%, more extensive aggregates connect into a percolating network, substantially raising the yield stress. At 70 wt.%, particle spacing is minimized, resulting in a robust, continuous three-dimensional network. This network causes a sharp rise in yield stress [39]. Correspondingly, the consistency coefficient (k) exhibits exponential growth, mirroring the trend in yield stress. In contrast, the flow index (n) decreases progressively from 0.92 for the 50 wt.% sample—indicating near-Newtonian behavior with weak shear-thinning—to 0.84 and 0.52 for the 60 and 70 wt.% samples, respectively. This progressive decline in the flow index confirms the enhanced non-Newtonian character and more pronounced shear-thinning behavior at higher particle concentrations. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the dramatic changes in rheological properties are rooted in the microstructural evolution from “loose aggregates” to a “continuous three-dimensional network” with increasing particle concentration.

Table 1.

H-B fitting parameters of ferrofluids with different particle concentrations.

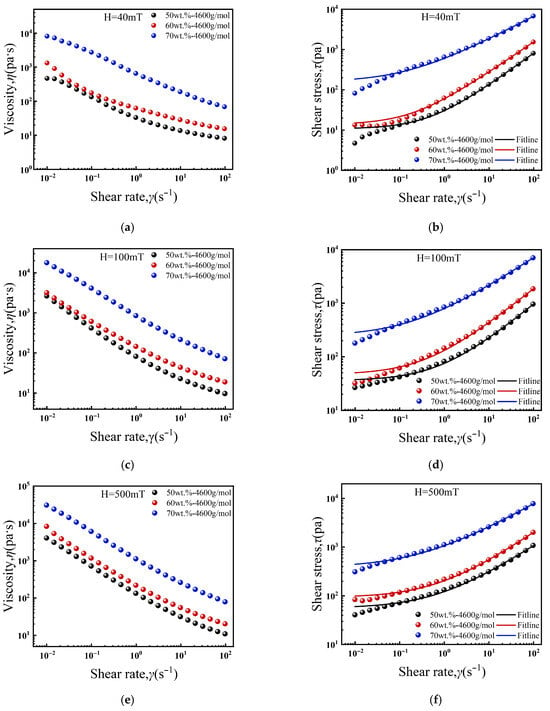

The rheological properties of the ferrofluids under an applied magnetic field are presented in Figure 4. Figure 4a,c demonstrate a significant field-induced thickening effect, where the viscosity at a given shear rate increases with magnetic field strength. This phenomenon is caused by magnetic dipole–dipole interactions that induce the nanoparticles to align into chain-like or columnar structures along the field direction [40]. A stronger field enhances these interactions, promoting the formation of denser, longer chains and thus a more pronounced thickening effect [41]. Similarly, the yield stress increases with field strength, as shown in Figure 4b,d. This enhancement is due to the formation of elongated particle chains, which cross-link into a three-dimensional network [42]. It is noted that the Herschel–Bulkley (H-B) model shows poor agreement with the experimental data at low shear rates, with the fit improving as the shear rate increases.

Figure 4.

Effect of particle concentration on rheological properties of ferrofluids under magnetic field: (a) viscosity curves (40 mT), (b) shear stress curve (40 mT) and H-B fitting curves, (c) viscosity curves (100 mT), (d) shear stress curve (100 mT) and H-B fitting curves, (e) viscosity curves (500 mT), (f) shear stress curve (500 mT) and H-B fitting curves.

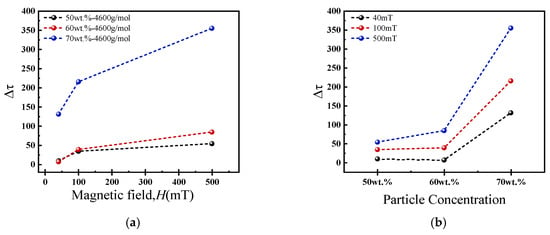

Figure 5 depicts the variation in the field-induced yield stress (Δτ) with particle concentration. The results show that Δτ scales markedly with concentration at a constant magnetic field strength, a trend driven by the exponential increase in magnetic dipole–dipole interaction force as interparticle spacing decreases, as described by Equation (2). A particularly sharp rise in Δτ is observed when the concentration increases from 60 to 70 wt.%. At this ultra-high concentration, the drastically reduced particle spacing causes a superposition of magnetic dipole fields from neighboring particles. This effect amplifies the local magnetic field strength [39], which in turn strengthens the interparticle magnetic interactions, resulting in a more rigid and robust cross-linked spatial network that is highly resistant to deformation [27].

where Fd is the magnetic dipole–dipole interaction force, μ0 is the vacuum permeability, V is the particle volume, r is the particle spacing, and M is the particle magnetization.

Figure 5.

(a) Variation in field-induced yield stress of ferrofluids with different particle concentrations. (b) Field-induced yield stress as a function of particle concentration at 40 mT, 100 mT and 500 mT.

The field-induced yield stress is plotted as a function of particle concentration for 40 mT, 100 mT, and 500 mT in Figure 5b. This new representation clearly illustrates the nonlinear and synergistic enhancement of Δτ with both increasing particle concentration and magnetic field strength. The data show a clear progression with magnetic field strength, where the Δτ values for the 40 mT field lie consistently below those for 100 mT and 500 mT. The significantly steeper slope of the curves at higher concentrations (from 60 to 70 wt.%) visually confirms the formation of a much more rigid and robust magnetic field-induced network, as discussed in the text. The substantial and progressive gaps between the 40 mT, 100 mT, and 500 mT curves across all concentrations underscores the strong field dependence of the yield stress.

3.3. Quantitative Analysis Using the Magnetoviscous Parameter

To generalize our findings and facilitate a comparison with prior studies, the field-induced enhancement in viscosity is quantified using the magnetoviscous parameter (RH), defined as the relative increase in viscosity due to the magnetic field:

where ηH is the viscosity under an applied magnetic field and η0 is the zero-field viscosity at the same shear rate.

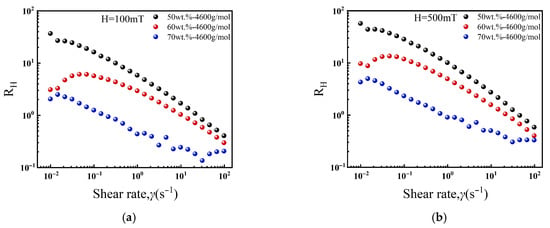

Figure 6a,b present the magnetoviscous parameter, RH, as a function of shear rate for ferrofluids with different particle concentrations under applied magnetic fields of 100 mT and 500 mT, respectively. A prominent feature observed is the significant enhancement of RH at low shear rates, which diminishes rapidly with increasing shear rate. This behavior originates from the competition between the strength of the magnetic field-induced structures and the hydrodynamic shear forces. At low shear rates, magnetic interactions dominate, facilitating the formation and persistence of chain-like structures that impede flow, thereby resulting in high RH values. As the shear rate increases, the progressively stronger hydrodynamic shear forces disrupt these structures, causing particle alignment along the flow direction and reducing the magnetoviscous effect until it becomes negligible.

Figure 6.

The magnetoviscous parameter, RH, as a function of shear rate for ferrofluids with different particle concentrations: (a) 100mT, (b) 500mT.

Furthermore, at any given shear rate, the magnetoviscous parameter, RH, increases markedly with both particle concentration and magnetic field strength. This trend is fully consistent with the enhanced interparticle magnetic interactions discussed previously. Stronger interactions promote the formation of more robust field-induced structures, which consequently exhibit greater resistance to shear-induced breakup.

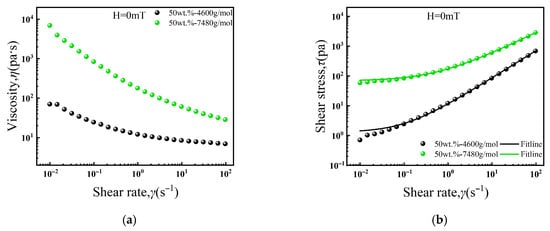

3.4. Effect of Molecular Weights of Carrier Liquid on Rheological Properties of Ferrofluids

As shown in Figure 7, the carrier liquid’s molecular weight significantly affects the zero-field rheological properties. Both samples are strongly shear-thinning, meaning their viscosity drops sharply as the shear rate increases. The sample with the higher-molecular-weight carrier (7480 g/mol) possesses greater zero-field viscosity than the 4600 g/mol sample. This is because the higher-molecular-weight fluoroether oil has longer polymer chains. These longer chains enhance physical entanglement [43]. Consequently, shearing must overcome more entanglements. This results in higher flow resistance and more pronounced shear-thinning.

Figure 7.

Effect of molecular weight of carrier liquid on rheological properties of ferrofluids under zero magnetic field: (a) viscosity curves, (b) shear stress curves and H-B model fitting curves.

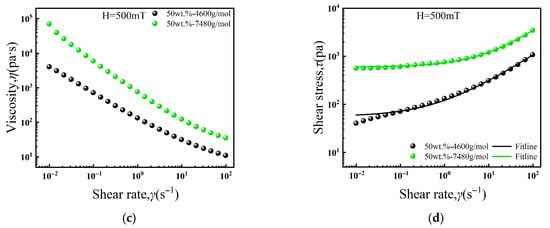

Figure 8 depicts the influence of carrier liquid molecular weight on the viscosity of ferrofluids under an applied magnetic field. As shown in Figure 8a, the viscosity of the 50 wt.%-7480 g/mol sample exceeds that of the 50 wt.%-4600 g/mol counterpart at any given shear rate, consistent with the zero-field behavior. Correspondingly, Figure 8b shows that the shear stress is also higher for the sample with the higher-molecular-weight carrier liquid. The shear stress curves were fitted with the Herschel–Bulkley model (Equation (1)), with the resulting parameters listed in Table 2. The fits confirm that both the yield stress and consistency coefficient increase with magnetic field strength for both ferrofluids. Notably, the 50 wt.%-7480 g/mol sample achieves the highest yield stress of 589.79 Pa at 500 mT, indicating that the magnetic field-induced structure formed in this system possesses the greatest mechanical strength. This superior performance is also influenced by the longer molecular chains of the carrier liquid, which contribute to the network’s robustness [27]. Furthermore, the flow index (n) for both samples remains below unity, corroborating their shear-thinning nature under a magnetic field.

Figure 8.

Effect of molecular weight of carrier liquid on rheological properties of ferrofluids under magnetic field: (a) viscosity curves (100 mT), (b) shear stress curve (100 mT) and H-B fitting curves, (c) viscosity curves (500 mT), (d) shear stress curve (500 mT) and H-B fitting curves.

Table 2.

H-B fitting parameters of ferrofluids with carrier liquids of different molecular weights under magnetic field.

3.5. Study on Variation Law of Viscoelasticity of Ferrofluids

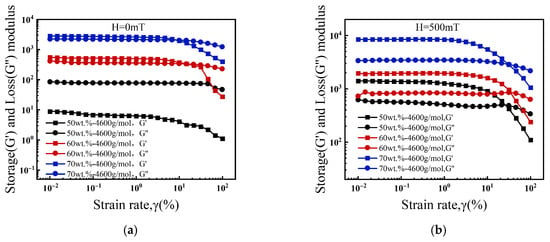

Figure 9 presents the viscoelastic response of the ferrofluids versus particle concentration. The linear viscoelastic region (LVE) is the strain range where the storage modulus (G′) remains within 5% of its plateau value. The critical strain (γc) marks the end of this region. As shown in Figure 9a under zero magnetic field, the 50 wt.% sample exhibits fluid-like behavior within the LVE, with G′ lower than the loss modulus (G″). In contrast, the 60 and 70 wt.% samples show a solid-like response, with G′ exceeding G″. Furthermore, both the plateau storage (G′LVE) and loss (G″LVE) moduli increase significantly with particle concentration, indicating enhanced interparticle interactions and the formation of a denser network structure.

Figure 9.

Strain sweep curves of ferrofluids prepared with different particle concentrations: (a) 0 mT, (b) 500 mT.

Parameter ΔG (= G′LVE − G″LVE) was defined to quantify the degree of elasticity dominance in the system. Under a zero magnetic field, a negative ΔG value for the 50 wt.% sample confirms its viscosity-dominated behavior. In contrast, the positive and progressively increasing ΔG values for the 60 wt.% (144.77 Pa) and 70 wt.% (504.74 Pa) samples signify a transition to elasticity-dominated responses. This trend demonstrates that the elastic character is strengthened and the network structure becomes more continuous and stable with increasing particle concentration.

As shown in Figure 9b under a 500 mT magnetic field, all samples exhibit solid-like behavior within the LVE region, with G′ exceeding G″. Compared to the zero-field condition, both the plateau storage (G’LVE) and loss (G″LVE) moduli are significantly enhanced at all concentrations. This universal transition occurs because the magnetic field induces particle alignment into columnar chains. This alignment transforms the microstructure from a disordered suspension into a “chain–carrier liquid” composite. This robust, load-bearing structure is responsible for the greatly enhanced elastic modulus of the system [27,39,42].

The viscoelastic parameters of the ferrofluids under various conditions are summarized in Table 3. The data show that G′LVE increases substantially with particle concentration, but the rate of this increase tends to level off. This saturation effect is attributed to the reduction in particle spacing and the confinement of free volume, which diminishes the marginal enhancement of the network structure [44,45]. Furthermore, under a 500 mT magnetic field, the ΔG values for all samples (50, 60 and 70 wt.%) are significantly elevated compared to their zero-field states. This indicates that the magnetic field not only intensifies the elasticity-dominated behavior of the system but also that the enhancement is more pronounced at higher particle concentrations.

Table 3.

Viscoelastic parameters of ferrofluids under different particle concentrations, molecular weights of carrier liquid and magnetic field conditions.

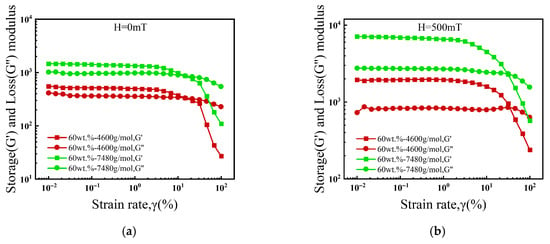

The strain-dependent viscoelastic behavior of 60 wt.% ferrofluids prepared with different carrier liquid molecular weights is shown in Figure 10. As shown in Figure 10a under a zero magnetic field, both samples exhibit solid-like behavior (G′ > G″) within the LVE region, with the modulus of the 7480 g/mol sample being significantly higher. This is attributed to the longer polymer chains of the high-molecular-weight oil, which form a denser entanglement network with more interaction points and possess greater inherent elastic recovery [28,39]. Under a 500 mT field as shown in Figure 10b, G′ is further enhanced for both samples. This synergistic stiffening has two causes. First, the magnetic field induces particle chains that improve stress transmission [27,37]. Second, the polymer entanglement network concurrently restricts chain slip. The magnetic field also reduces the extent of the LVE region for both samples, as the field-induced chains are more susceptible to strain. However, the 7480 g/mol sample maintains a wider LVE region, owing to the superior deformation resistance imparted by its stronger entanglement network.

Figure 10.

Strain sweep curves of ferrofluids prepared with carrier liquids of different molecular weights: (a) 0 mT, (b) 500 mT.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a series of high-viscosity fluoroether oil-based ferrofluids with varying particle concentrations and carrier liquid molecular weights were successfully prepared via chemical co-precipitation, and their rheological properties were systematically investigated. The results demonstrate that both magnetic field strength and particle concentration significantly enhance the viscosity and yield stress (τ0) of the ferrofluids. Notably, at particle concentrations exceeding 50 wt.%, the influence of concentration on viscosity dominates that of the magnetic field. The Herschel–Bulkley model accurately describes the yield stress behavior at high shear rates. The field-induced thickening effect is prominent at low shear rates but diminishes at high shear rates. The zero-field viscosity and shear yield stress were substantially higher for the 50 wt.%-7480 g/mol sample than for the 50 wt.%-4600 g/mol counterpart. The 50 wt.%-7480 g/mol sample also achieved the highest yield stress (589.79 Pa at 500 mT), resulting from the enhanced physical entanglement between polymer chains. Viscoelastic analysis revealed that the 50 wt.%-4600 g/mol sample is liquid-like in the absence of a field, whereas the 60 and 70 wt.% samples are gel-like. The sample prepared with the higher-molecular-weight carrier liquid (60 wt.%-7480 g/mol) exhibited superior elasticity. Furthermore, the elasticity dominance parameter (ΔG) increased with magnetic field strength, indicating a reinforced solid-like response, particularly for the 70 wt.%-4600 g/mol sample.

Looking forward, translating these ultra-high-viscosity ferrofluids into industrial applications (e.g., high-pressure sealing) requires attention to scalable production and long-term stability. Fortunately, the ultra-high viscosity and gel-like characteristics inherent to the systems studied here provide a favorable condition for suppressing particle sedimentation. Future work will focus on optimizing batch synthesis routes and systematically evaluating the performance evolution under practical service conditions, such as long-term storage, repeated shearing, and thermal cycling, to ensure their reliability in real-world applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.; investigation, F.C., Y.L., Q.G., Y.X., Y.D., S.Y., Y.H. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Regional Joint Fund for Innovative Development (Grant No. U23A20669), and it was also funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant No. 52379092. and the Xihua University Science and Technology Innovation Competition Project for Postgraduate Students (Grant No. YK20240214).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oehlsen, O.; Cervantes-Ramírez, S.I.; Cervantes-Avilés, P.; Medina-Velo, I.A. Approaches on ferrofluid synthesis and applications: Current status and future perspectives. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 3134–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, M.; Khandekar, S. Engineering applications of ferrofluids: A review. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 537, 168222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Dou, X.; Han, L. Experimental study of symmetrical ferrofluid seals with single magnetic source and small clearance. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęch, M. Experimental study on the leak mechanism of the ferrofluid seal in a water environment. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 4600510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, D. The sealing pressure variance originated from volume of ferrofluids in magnetic fluid seal. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, D.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, L.; Yao, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; et al. Experiment and simulation on the ferrofluid boundary deformation and fluctuation characters of a high-speed rotary seal. J. Tribol. 2024, 146, 064402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, D. Fabrication and properties research on a novel perfluoropolyether based ferrofluid. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 473, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, P.; Li, D.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Typical dampers and energy harvesters based on characteristics of ferrofluids. Friction 2023, 11, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, D. The theoretical and experimental study of a ferrofluid inertial sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Lv, R.Q.; Zhang, Y.N.; Wang, Q. Review on optical fiber sensors based on the refractive index tunability of ferrofluid. J. Light. Technol. 2016, 35, 3406–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Z.; Han, W.; Li, D.; Yan, S.; Zhou, J. Study of the flow characteristics of pumped media in the confined morphology of a ferrofluid pump with annular microscale constraints. J. Fluids Eng. 2025, 147, 021201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Z.; Han, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y. Mechanism of bubble generation in ferrofluid micro-pumps and key parameters influencing performance. Powder Technol. 2025, 467, 121562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, W.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y. Research on the flow rate characteristics and velocity pulsation behavior of ferrofluid micro pumps. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 526, 171211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D. Rheological properties of silicon oil-based magnetic fluid with magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs)-multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWNT). Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 065023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Ionic liquids–based magnetic nanofluids as lubricants. Lubr. Sci. 2018, 30, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, K.B. Properties of Polyalphaolefin-Based Ferrofluids. J. Magn. 2015, 20, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yao, J.; Li, D. Research on the rheological properties of a perfluoropolyether based ferrofluid. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 424, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, D. Preparation and property research of perfluoropolyether oil-based ferrofluid. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3607–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, D.; Dai, R. Experimental analysis of starting torque of perfluoro polyethers-based magnetic fluid seal. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2017, 38, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; He, X. A ferrofluid-based tuned mass damper with magnetic spring. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2019, 60, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, M.; Mansourpour, Z.; Shariaty-Niassar, M. Controlled assembly and alignment of CNTs in ferrofluid: Application in tunable heat transfer. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 479, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yao, J. Influence of viscosity and magnetoviscous effect on the performance of a magnetic fluid seal in a water environment. Tribol. Trans. 2018, 61, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Vafajoo, L.; Ghasemi, E.; Salman, B.H. Experimental investigation the effect of nanoparticle concentration on the rheological behavior of paraffin-based nickel ferrofluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 93, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Cui, H. Steady-state and dynamic rheological properties of a mineral oil-based ferrofluid. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čampelj, S. Rheology of aqueous ferrofluids: Transition from a gel-like character to a liquid character in high magnetic fields. ChemEngineering 2023, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, A.Y.; Odenbach, S.; Fleischer, J. Rheological properties of dense ferrofluids. Eff. Chain-Like Aggreg. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 252, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.O.; Zubarev, A. Chain formation and phase separation in ferrofluids: The influence on viscous properties. Materials 2020, 13, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, D.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Influence of the carrier fluid viscosity on the rotational and oscillatory rheological properties of ferrofluids. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 5572–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z. Rheological and magnetic properties of stable poly alpha olefins based ferrofluids with high viscosity and magnetization. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 564, 170096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Zhao, W.; Nie, S.; Yang, J. Research on preparation and stability of high viscosity carbon nanotube-modified PAO20-based magnetic fluids. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 41, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kaminski, M.D.; Guan, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Rosengart, A.J. Preparation and characterization of hydrophobic superparamagnetic magnetite gel. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 306, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Yan, S.; Fu, H.; Yan, Z. Investigation of the rheological properties of Zn-ferrite/perfluoropolyether oil-based ferrofluids. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Ma, Y.; Tong, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, M. Solvothermal synthesis, characterization, and magnetorheological study of zinc ferrite nanocrystal clusters. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2017, 28, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi, G.; Singh, R. Magneto-viscosity of MnZn-ferrite ferrofluid. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2014, 448, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z. Influence of various parameters on the performance of superior PFPE-oil-based ferrofluids. Chem. Phys. 2018, 513, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, R.A.; Pavel, K.; Georges, B.; DG, D.J. Optimizing the Magnetic Response of Suspensions by Tailoring the Spatial Distribution of the Particle Magnetic Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 12143–12147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zubarev, A.Y.; Iskakova, L.Y. Theory of structural transformations in ferrofluids: Chains and “gas-liquid” phase transitions. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 061406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Mathew, S. Ferrofluids: Synthetic strategies, stabilization, physicochemical features, characterization, and applications. ChemPlusChem 2014, 79, 1382–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Holm, C.; Müller, H.W. Molecular dynamics study on the equilibrium magnetization properties and structure of ferrofluids. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 021405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, A.Y.; Iskakova, L.Y. Structural transformations in ferrofluids. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 68, 061203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.; Yan, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Lei, Z.; Wang, Q. Manipulating three-dimensional magnetic particles motion in a rotating magnetic field. Powder Technol. 2025, 449, 120391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vicente, J.; Klingenberg, D.J.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, R. Magnetorheological fluids: A review. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 3701–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguineti, A.; Guarda, P.A.; Marchionni, G.; Ajroldi, G. Solution properties of perfluoropolyether polymers. Polymer 1995, 36, 3697–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.L.; Weeks, E.R. The physics of the colloidal glass transition. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2012, 75, 066501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Derkach, S.R.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheology of gels and yielding liquids. Gels 2023, 9, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).