Abstract

During their stay at the surface of the Earth, meteorites undergo terrestrial weathering. In particular, the iron-nickel alloys and iron sulfides that are abundant in many types of meteorites transform into oxides and oxihydroxides (magnetite, maghemite, akaganeite, etc.). Mössbauer spectroscopy is a powerful tool to identify these weathering products. However, distinguishing signals from different phases summed up in the Fe3+ paramagnetic doublets in the central part of the spectrum remains challenging. This study focuses on a detailed investigation of meteorite weathering products to separate signals from different secondary minerals formed on Earth in a series of weathered meteorites. We carried out a room-temperature Mössbauer spectroscopy study on seventy ordinary chondrites collected in the Atacama Desert, Chile, in order to make a comparative qualitative analysis of the mineralogy of their terrestrial weathering products. Based on these results, three samples showing a variety of weathering products (Catalina 146, Catalina 535, and El Médano 070) were selected for a detailed study and two of them for low-temperature Mössbauer study. We found that, above 200 K, most meteorites exhibit superparamagnetic magnetization dynamics attributable to strong dispersed maghemite–magnetite phase formed as a weathering product. On the other hand, other iron-bearing weathering products (goethite, akaganeite, hematite) demonstrate line shapes of the corresponding partial components that are close to the shapes of the bulk samples. Only two of the 70 measured meteorites showed no superparamagnetic behavior at room temperature.

1. Introduction

Meteorites are unique objects whose study allows us to address questions about the origin and evolution of the Solar System and planetary formation. Among the interesting questions addressed through meteorite studies is the quantification of the meteorite flux to the Earth and the identification of possible variations in this flux. This requires estimating the age of the meteorite fall on Earth, called its terrestrial age. The study of the meteorite flux ultimately contributes to understanding how material is transferred from the asteroid belt to the Earth’s surface through complex dynamic processes.

The primary magnetic iron minerals (mainly kamacite and taenite, which are abundant in most meteorites) tend to transform into iron oxides and oxyhydroxides under terrestrial conditions. Thus, changes in magnetic mineralogy reflect the gradual weathering of meteorites in the terrestrial environment. Therefore, the amount and nature of these secondary mineral reactions might be a quantitative proxy of the terrestrial age of the meteorites [1]. Some studies suggest the possibility of using weathering products as ‘sensors’ to do a retrospective study of the chemical reactivity of the planetary environment as a function of time [2]. Classically, the terrestrial age of meteorites is estimated from the measurement of radioactive cosmogenic nuclide concentration, typically 14C, 36Cl, or 10Be, depending on the age range of interest [3]. On the other hand, the weathering mineralogy of meteorites during their stay on Earth may be a good proxy for their terrestrial age [4]. The primary magnetic minerals in many meteorite groups, and, in particular, in ordinary chondrites that are the most abundant meteorites available for study, are Fe-Ni alloys. In the terrestrial environment, these alloys undergo weathering to form iron oxyhydroxides and/or oxides. Magnetic methods and Mössbauer spectrometry (MS) are often used to characterize these magnetic minerals and their weathering products [5,6,7,8,9]. Mössbauer spectroscopy is also sensitive to the weathering of iron sulfides (in particular, troilite, a paramagnetic mineral present in most meteorites).

The Atacama Desert is the driest and oldest desert on Earth, providing a unique combination of conditions for meteorite accumulation at the surface [1]. The Atacama Desert is a suitable location for studying weathering products of meteorites because of the high number of meteorite finds and a wide range of terrestrial ages. In fact, meteorite density in the range 100 to 200 meteorites >10 g per km2 has been described in the Central Depression of the Atacama Desert [10,11]. These elevated meteorite densities are explained by terrestrial ages of up to 2 Ma, with an average of 710 ka, for instance, in the El Médano dense collection area [12]. The hyperaridity of the Central Depression of the Atacama Desert is one of the critical factors slowing down the oxidation of Fe0 and Fe2+ to Fe3+. This allows weathering to be studied on a longer time scale than in any other hot desert.

Chondrites represent the most primitive material of the Solar System. They can contain solids formed by direct condensation from the nebular gas (calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions), organic matter, and solids formed by melting and quenching of dust with a Solar composition (chondrules). The abundance of primary iron-bearing minerals in ordinary chondrites and the effects of terrestrial weathering have been the focus of a large number of Mössbauer studies [8,13,14]. The combination of Mössbauer spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) has been shown to be a powerful approach for a detailed characterization of redox conditions of ordinary chondrites [15].

However, in weathered ordinary chondrites, the central part of room-temperature Mössbauer spectra remains difficult to interpret in terms of the identification of secondary phases. This is due to the diversity of weathering products, their high dispersion (variations in particle shape, size, and their non-stoichiometry), and rapidly occurring relaxation processes. In other studies, for the central part of the spectrum where several phases with similar hyperfine interaction parameters are present, a broadened doublet with parameters characteristic of Fe3+ in a paramagnetic state is often introduced using mathematical modeling, without separating signals from individual secondary minerals. In mathematical description, this doublet component allows, as a zero-order approximation, accounting not only for various paramagnetic phases but also for ultrafine phases in superparamagnetic relaxation collapse mode.

The present work is devoted to a detailed study of weathering products in meteorite samples from the Atacama Desert with the aim of clarifying their phase and magnetic properties. We are presenting the results of low-temperature Mössbauer spectroscopy studies of three meteorites chosen to show a variety of weathering products. This allowed us to improve our approach to fitting Mössbauer transmission spectra, which made it possible to better distinguish between primary and weathering products based on the parameters of hyperfine interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objects of Investigation

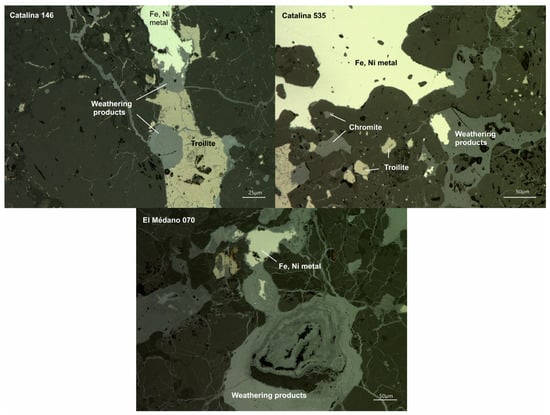

In this study, we investigate three ordinary chondrites from the Atacama Desert: Catalina 146 (H5, weathering grade W1, terrestrial age 166 ka), Catalina 535 (H5, W1, 1504 ka), and El Médano 070 (L6, W3, 270 ka). The terrestrial ages are from Sadaka et al. [16]. The weathering grades, as defined by Wlotzka [17], are based on the modal abundance of weathering products relative to the initial amount of metal and troilite. A weathering grade of W1 indicates that less than 20% of the initial metal and troilite have been weathered. A weathering grade of W3 indicates that between 60 and 90% of the initial metal and troilite have been weathered. Reflected light images evidencing the weathering intensity and style for the three meteorites are provided in Figure 1. The meteorites were selected among 70 meteorites from the Catalina and El Médano dense collection areas [10,11] for which we measured room-temperature Mössbauer spectra. The selection was made to span a range of meteorite groups, weathering state, weathering mineralogy, and terrestrial ages. All samples are from the meteorite collection of the Centre de Recherche et d’Enseignement des Géosciences de l’Environnement (CEREGE). We performed a room and low-temperature Mössbauer study and X-ray diffraction analysis on these three meteorites.

Figure 1.

Reflected light images of Catalina 146, Catalina 535, and El Médano 070.

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction

X-ray powder diffraction analysis was performed at the Institute of Geology and Petroleum Technologies, Kazan Federal University, using the D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) in Bragg–Brentano geometry with monochromated CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in step-scan mode. The measurement and recording parameters were as follows: X-ray tube voltage of 30 kV, current of 10 mA, scanning step of 0.02°, and scanning speed of 1°/min. The scanning angle range in Bragg–Brentano geometry was 10–100°. To minimize texture effects, the sample was continuously rotated perpendicular to the goniometer axis. The detection limit of the method is about 1 wt%.

X-ray diffraction measurements were conducted on powdered samples. Samples with mass ~200 mg were ground in an agate mortar to produce powder with particle sizes smaller than 100 µm. To minimize structural defects in minerals caused by mechanical processing, grinding was performed in a 95% ethyl alcohol medium. The powder was then dried and loaded into standard steel sample holders before being manually gently pressed flat.

Data processing was carried out using DIFFRAC plus Evaluation Package software version 3.2 (EVA, Search/Match) to perform both qualitative and quantitative analysis. The resulting diffraction patterns were compared with reference patterns from a database. Primary interplanar spacings were identified and matched to specific mineral phases. The analysis utilized the international Powder Diffraction File database (PDF-2) as the reference.

2.3. Mössbauer Study

The 57Fe Mössbauer spectra were obtained at the Institute of Physics, Kazan Federal University, on a standard MS-1104Em spectrometer № 40–12 (SFedU, Rostov-on-Don, Russia) in the constant acceleration mode using a symmetric sawtooth law of velocity change with separate accumulation of the spectra as the source moves forward and backward and their subsequent summation to eliminate background line distortion. A scintillation counter with a thin NaI (Tl) crystal was used as the detector. The spectra were obtained with a 57Co source in a Rh matrix. Calibration was performed using the α-Fe spectrum, and isomer shifts were measured from the “center of gravity” of the spectrum obtained at room temperature (RT) of this reference. Mathematical handling of the gained spectra was carried out through the Mössbauer program SpectrRelax [18]. All samples were placed in a round (1 cm in radius) aluminum holder, which was attached to the cryostat, and their temperature was changed between 80 and 300 K by a temperature controller with an accuracy of ±0.5 K. The mass of measured powdered samples was ~200 mg.

3. Results

Diffraction patterns of three samples show similarity in composition of the meteorites with little difference in mineralogy and mineral abundances (Figures S1–S3). Crystalline phases present in the samples, and their abundance, are given in Table 1. XRD analysis was performed to better interpret the Mössbauer spectroscopy results and determine the exact minerals of pyroxenes and olivine groups. The XRD results help to better interpret MS results.

Table 1.

Results of XRD analysis in wt%.

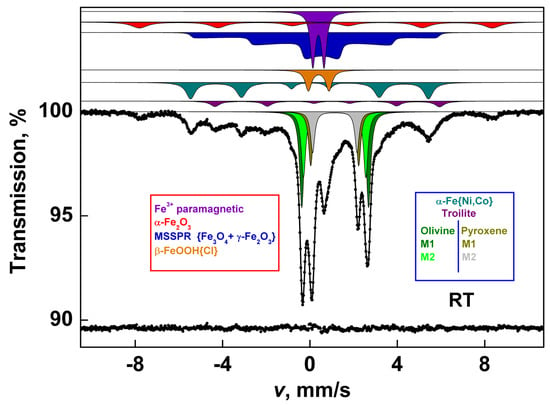

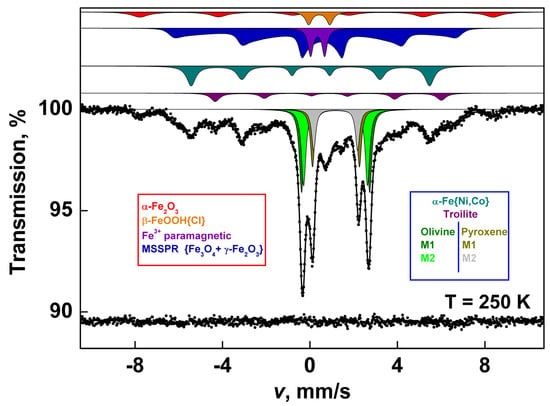

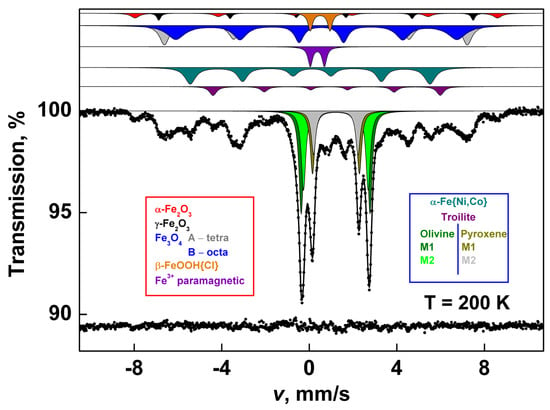

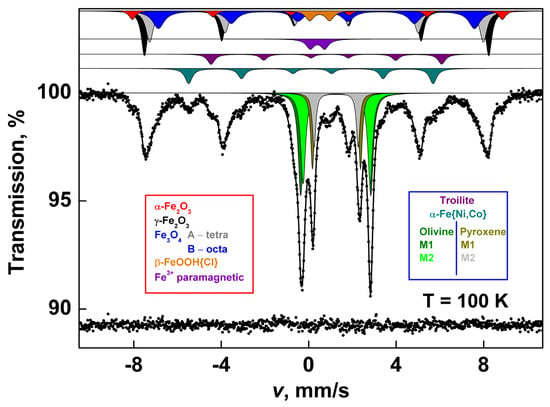

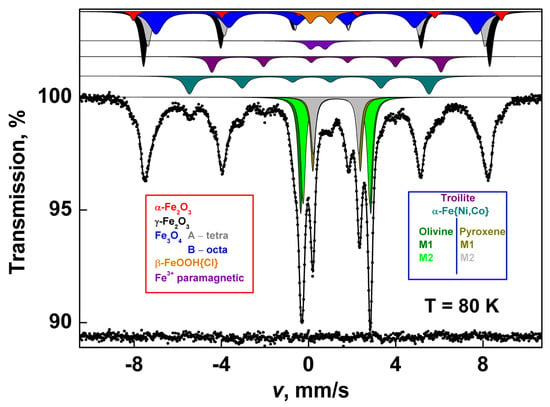

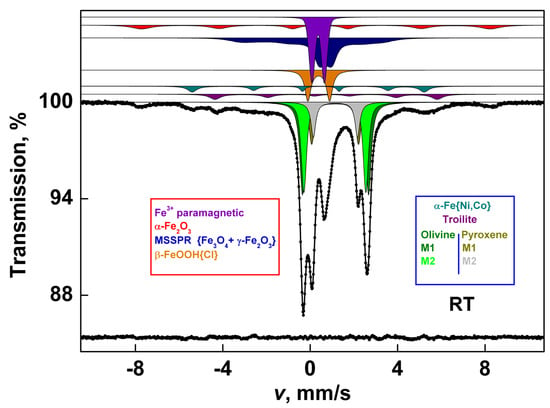

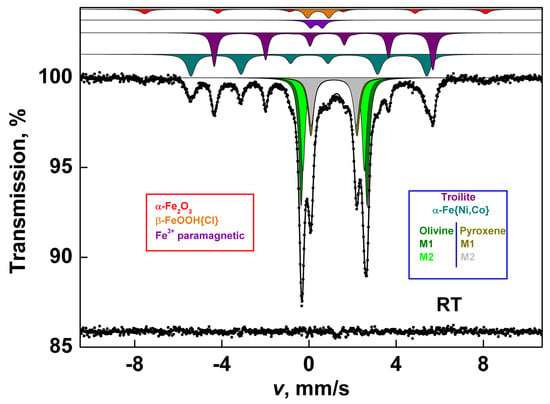

The Mössbauer spectra for the three studied samples are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. They show a well-characterized set of primary minerals classically found in ordinary chondrites: olivine (Mg,Fe)2[SiO4], pyroxene (Mg,Fe)2[Si2O6], troilite (FeS), and kamacite (α-Fe{Ni,Co}) (Table 2). Typical weathering products were also detected with different relative contributions: hematite (α-Fe2O3), strongly dispersed intermediary magnetite/maghemite phase (Fe3O4 + γ-Fe2O3), goethite (α-FeOOH), and akaganeite (β-FeOOH{Cl}), which is formed only in the presence of Cl− anions and contains them in its crystal lattice (Table 2. The chlorine for forming akaganeite comes from the salts present in the Atacama Desert’s subsurface layer. Two doublet components corresponding to two different metal sites (M1 and M2) in the olivine crystal lattice were detected in all spectra of the studied meteorite samples. Partial areas of these components (M1 + M2) range from ~25 to ~39% (i.e., 25 to 39% of the total Fe in the sample is in the olivine; here and in the following, all MS results are in % of total Fe present in each phase). These components exhibit approximately the same values of the hyperfine interaction parameters (Table 2). The partial fractions of pyroxenes (M1 + M2) are smaller than those of olivine, ranging from ~14 to ~24 percent in the transmission spectra (Table 2). The troilite fractions in the samples Catalina 535 and El Médano 070 range from ~4 to ~5%. In the case of the Catalina 146 sample, this area is three times larger. The kamacite fraction in the Catalina 146 sample is also more important (15%) than in the other two cases. In contrast to the primary products, the spectral components of the weathering products demonstrate temporal stochastic effects in the magnetic subsystem. The most time-dependent behavior is demonstrated by components corresponding to the intermediary magnetite-maghemite phase. To a lesser extent, this seems to be the case for hematite; its lines broaden as the observation temperature approaches room temperature. Doublets of Fe3+ paramagnetic and akaganeite can be partially resolved in the spectrum of Catalina 535 recorded at 200 K (Figure 4 and Figure S4). The 14.41 keV ±1/2 → ±3/2 transitions in 57Fe differ significantly in resonant Doppler velocity for Fe3+ paramagnetic and akaganeite partial components (Figure S4). The doublets with parameters associated with goethite and akaganeite seem to be static at all observation temperatures. Goethite and part of the superparamagnetic intermediate magnetite/maghemite phase in the fast relaxation regime give unresolved doublets at all temperatures. The parameters of the hyperfine interactions in these doublets are very close, and their partial areas are summarized in the Fe3+ paramagnetic component. This statement is true for the Catalina 535 and El Médano 070 samples; in Catalina 146, the presence of goethite is not confirmed by XRD data. For the Catalina 146 sample, we associate the Fe3+ paramagnetic component area only with the isotropic superparamagnetic intermediate magnetite/maghemite phase in the regime of collapse of the hyperfine spectral structure. Apparently, the particles of intermediate magnetite/maghemite phase in the sample Catalina 146 are the smallest and have sizes smaller than those necessary for the occurrence of spontaneous magnetization at the investigated temperatures. This magnetic behavior is well demonstrated on a model nanoscale core(α-Fe)-shell(γ-Fe2O3) system with a characteristic size of 2.5 nm. Low-temperature blocking of the nanoparticles’ magnetic moments have been clearly evidenced in the integrated electron magnetic resonance line intensity, and the blocking temperature was only about 60 K [19]. The absence of the hyperfine sextets characteristic of magnetite in the spectra of ordinary chondrites may seem a surprising result given the stability of magnetite in terrestrial surface environments and its resistance to alteration. However, in some cases, this is the result of strong dispersion in the intermediate magnetite/maghemite phase for which only doublet components can be observed at different temperatures. Apparently, the Catalina 146 sample is exactly like this. At room temperature and below, superparamagnetic relaxation sextets are observed in the spectra of Catalina 535 and El Médano 070 (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 7 and Figure S5, Table S1). The mathematical fitting of these subspectra, typical for Mössbauer spectra of superparamagnetic particles, was performed using the Many-State Superparamagnetic Relaxation (MSSPR) model [20], implemented in the SpectrRelax tool. The integral forms of spectra of three selected samples show differences at the same temperature, apparently caused by the different dispersion of weathering products, primarily by the intermediate magnetite–maghemite phase. The MSSPR component is practically undetectable in the spectrum of Catalina 146 and, if present, its partial area is less than half a percent. Because of its small magnitude, this signal is easily lost due to the presence of more than forty resonances between nuclear transition energies for 57Fe nuclei with and in hematite. At 80 K, the spectra of samples Catalina 535 and El Médano 070 (Figure 6 and Figure S6, Table S2) show characteristic relaxation times larger than the Larmor precession time; thus, sextets appear similar to those of bulk samples. The spectra under these observational conditions show an almost imperceptible contribution of the time-dependent function to the Hamiltonian.

Figure 2.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at RT (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 3.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at 250 K (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 4.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at 200 K (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 5.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at 100 K ( black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 6.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at 80 K ( black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 7.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample El Médano 070 measured at RT ( black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Figure 8.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample Catalina 146 measured at RT ( black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table 2)—solid lines.

Table 2.

Parameters of Mössbauer spectrum for powdered meteorites at different temperatures *.

4. Discussion

In the work by Nikulov et al. [21], a bulk powdered sample was separated into different fractions by magnetic separation. These fractions were used for further investigation, including Mössbauer spectroscopy. The authors identified two sextet partial components in the spectrum of the non-magnetic fraction (see Figure 5 in [21], SE-1nm), with hyperfine fields of ~30 T and <20 T, associated with well-crystallized and disordered goethite, respectively. When the particle size decreases below the critical value (for goethite, 15 nm at 300 K), the spectrum collapses into a doublet component. The authors also report significant line broadening of the sextets (~1.4 mm/s). As seen from our results, the broadened sextet components are substantially relaxation-induced, and freezing the relaxation leads to parameter stabilization with values characteristic of the intermediate magnetite-maghemite phase.

A separate important issue is the differentiation of paramagnetic phases in the central part of chondrite spectra. Distinguishing these phases is complicated due to the similar hyperfine interaction parameters of their doublet components, as well as line broadening caused by general non-stoichiometry and high dispersion of the target phases. Often, these components are not described in detailed mathematical terms but are collectively represented by a single, strongly broadened doublet [8,21]. Nikulov et al. [21] suggest that such a doublet corresponds to ultra-dispersed varieties of iron oxyhydroxides—hydrogoethite, akaganeite, lepidocrocite, and ferrihydrite. To address this issue, they recorded the doublet part of the non-magnetic sample spectrum with twice the resolution in the Doppler velocity range of −4 to +4 mm/s.

A significantly more radical approach to separating these phases is the use of low temperatures. Munayco et al. [8] employed helium temperatures (4.2 K) to magnetically split the components in the central part of the spectrum; however, the phases remained undifferentiated in the paramagnetic state. A distinctive feature of our study is the use of the temperature evolution of nuclear gamma resonance spectra for detailed phase analysis. As demonstrated in this work, the use of intermediate (250, 200, 100, 80 K) temperatures, combined with XRD data, allowed for the separation of contributions from various phases (akaganeite, goethite, intermediate magnetite-maghemite phase) in the central part of the Mössbauer spectra and the estimation of their partial fractions.

The spectra and MS results for the three studied meteorites show significant differences (Table 3). The abundance of α-Fe2O3, MSSPR (Fe3O4 + γ-Fe2O3), β-FeOOH{Cl}, and paramagnetic Fe3+ is significantly higher in meteorites with a greater terrestrial age. Conversely, the content of primary minerals: α-Fe{Ni,Co}, troilite, olivine, and pyroxene is higher in the younger meteorite. Iron content in each mineral phase is 15.4%, 15.2%, 38.8%, and 23.5%, respectively. These values are already reduced compared to those in fresh meteorites. For example, Jarosewich [22] reports that in fresh meteorites the iron content is: ~60% Fe in metal, ~13% Fe in troilite, ~28% Fe in olivine + pyroxene (for n = 24 H falls) and ~32% Fe in metal, ~17% Fe in troilite, ~51% Fe in olivine + pyroxene (for n = 53 L falls).

Table 3.

Results of Mössbauer spectroscopy, iron content (in % of the total iron) for various minerals in the samples.

It was shown that the central part of the room temperature Mössbauer spectra is difficult to interpret. Step-by-step freezing of the meteorites gives us the opportunity to distinguish different magnetic phases. The most productive application of low temperatures proved to be for the analysis of the signal from the transient dispersed magnetite–maghemite phase, whose partial component parameters at high temperatures differed significantly from those of the stoichiometric magnetite and maghemite phases. At the same time, the superparamagnetic partial contribution to the spectra from this phase was satisfactorily described by a single common MSSPR Fe3O4 + γ-Fe2O3 component for all samples across a wide range of observation temperatures. This fact convincingly indicates a common magnetic subsystem of magnetite and maghemite within this intermediate phase. The slow oxidation of magnetite to maghemite in the conditions of the Atacama Desert apparently leads to the formation of a randomly modulated short-range order, demonstrating the incompleteness of the maghemite formation process and, as a consequence, the unusual magnetic behavior of such a transitional phase.

Based on the study of only three meteorites, it is impossible to constrain with any detail the terrestrial weathering rate. However, we note a rough correlation between the sum of weathering products and the terrestrial age of meteorites (Table 3).

5. Conclusions

The method used in this study of weathered meteorites from the Atacama Desert, with Mössbauer spectroscopy combined with stepwise freezing of the samples, allowed us to describe the whole set of experimental data with one set of spectral components of primary minerals and differently dispersed weathering products. Weathering products are presented by goethite, akageneite, hematite, and an intermediate magnetite–maghemite phase, demonstrating superparamagnetic dynamics in the magnetic subsystem. The main feature identified in the weathering products of the studied meteorites is the magnetite–maghemite transitional phase at different stages of secondary oxidation. Utilizing the varying dispersity of this weathering product in the three selected samples revealed the formation of a phase with a randomly modulated short-range order. The properties of this phase evidence the slow progression of the oxidation of secondary magnetite into maghemite in conditions of the Atacama Desert. We also observe that meteorites with greater terrestrial ages contain more weathering products and very little remaining metal and troilite. A future study of all seventy meteorites with the same methodology would allow refining the relation between terrestrial age, meteorite group, and the amount and nature of weathering products, and eventually constrain the terrestrial weathering rate of meteorites in the Atacama Desert.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/magnetochemistry11120107/s1. Figure S1. XRD results of Catalina 535; Figure S2. XRD results of El Médano 070; Figure S3. XRD results of Catalina 146; Figure S4. Part of the 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the powdered sample Catalina 535 measured at 200K (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components – solid lines. The 14.41 keV ±1/2 → ±3/2 transitions in 57Fe differ significantly in resonant Doppler velocity for Fe3+paramagnetic and akaganeite; Figure S5. 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample El Médano 070 measured at 200K (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table S1)– solid lines; Figure S6. 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of powdered sample El Médano 070 measured at 80 K (black dots). Best fit lines for Mössbauer spectrum and partial components (see Table S2)– solid lines; Table S1. Parameters of Mössbauer spectrum for powdered sample El Médano at 200 K; Table S2. Parameters of Mössbauer spectrum for powdered sample El Médano 070 at 80 K*.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and J.G.; methodology, A.P.; investigation, A.P., C.S. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, J.G.; visualization, A.P., C.S. and R.M.; project administration, D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 24-27-00388, https://rscf.ru/project/24-27-00388/, accessed on 27 November 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Galina M. Eskina (Institute of Geology and Petroleum Technologies, Kazan Federal University) for providing X-ray diffraction measurements. We thank the reviewers for their work in improving our article and for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| RT | Room temperature |

| MS | Mössbauer spectroscopy |

References

- Pinto, G.A.; Tavernier, A.; Gattacceca, J.; Corgne, A.; Valenzuela, M.; Luais, B.; Flores, L.; Olivares, F.; Marrocchi, Y. Dense collection areas and terrestrial alteration of meteorites in the Atacama Desert. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2024, 59, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, P.A.; Bevan, A.W.R.; Jull, A.J.T. Ancient meteorite finds and the Earth’s surface environment. Quat Res. 2000, 53, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J.M.; Codilean, A.T.; Willenbring, J.K.; Lu, Z.T.; Keisling, B.; Fülöp, R.H.; Val, P. Cosmogenic nuclide techniques. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, P.A.; Berry, F.J.; Smith, T.B.; Skinner, S.J.; Pillinger, C.T. The flux of meteorites to the Earth and weathering in hot desert ordinary chondrite finds. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, D.; Gattacceca, J.; Gouilloux, H.; Mertens, H.; Lacube, R.; Demory, F.; Lorenz, C. The effect of terrestrial weathering on the magnetic properties of meteorites from the Atacama Desert. Uchenye Zap. Kazan. Univ. Ser. Estestv. Nauki. 2025, 167, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, E.V.; Chukin, A.V.; Varga, G.; Dankhazi, Z.; Leitus, G.; Felner, I.; Kuzmann, E.; Homonnay, Z.; Grokhovsky, V.I.; Oshtrakh, M.I. Characterization of bulk interior and fusion crust of Calama 009 L6 ordinary chondrite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2024, 59, 2865–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, P.A.; Zolensky, M.E.; Benedix, G.K.; Sephton, M.A. Weathering of chondritic meteorites. In Meteorites and the Early Solar System II; Lauretta, D.S., Mcsween, H.Y., Jr., Eds.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2006; pp. 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munayco, P.; Munayco, J.; De Avillez, R.R.; Valenzuela, M.; Rochette, P.; Gattacceca, J.; Scorzelli, R.B. Weathering of ordinary chondrites from the Atacama Desert, Chile, by Mössbauer spectroscopy and synchrotron radiation X-ray diffraction. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2013, 48, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, M.; Gattacceca, J.; Rochette, P.; Demory, F.; Valenzuela, E.M. Magnetic study of meteorites recovered in the Atacama desert (Chile): Implications for meteorite paleomagnetism and the stability of hot desert surfaces. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2012, 200–201, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, A.; Gattacceca, J.; Rochette, P.; Braucher, R.; Carro, B.; Christensen, E.J.; Cournede, C.; Gounelle, M.; Ouazaa, N.L.; Martinez, R.; et al. Description of a very dense meteorite collection area in western Atacama: Insight into the long-term composition of the meteorite flux to Earth. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2016, 51, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaka, C.; Gattacceca, J.; Gounelle, M.; Roskosz, M.; Lagain, A.; Tartese, R.; Bonal, L.; Maurel, C.; Martinez, R.; Valenzuela, M. Systematic Meteorite Collection in the Catalina Dense Collection Area (Chile): Description and Statistics. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2025, 60, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouard, A.; Gattacceca, J.; Hutzler, A.; Rochette, P.; Braucher, R.; Bourlès, D.; ASTER Team; Gounelle, M.; Morbidelli, A.; Debaille, V.; et al. The meteorite flux of the past 2 my recorded in the Atacama Desert. Geology 2019, 47, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshtrakh, M.I.; Petrova, E.V.; Grokhovsky, V.I.; Semionkin, V.A. A study of ordinary chondrites by Mössbauer spectroscopy with high-velocity resolution. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2008, 43, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, M.; Brzózka, K.; Woźniak, M.; Gałązka-Friedman, J.; Szopa, K. The influence of sample thickness on results of Mössbauer spectroscopy of ordinary chondrites and their classification. Interactions 2024, 245, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, O.N.; Bland, P.A.; Berry, F.J.; Cressey, G.A. Mössbauer spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction study of ordinary chondrites: Quantification of modal mineralogy and implications for redox conditions during metamorphism. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2005, 40, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaka, C.; Gattacceca, J.; Dumas, F.; Braucher, R.; ASTER Team; Gounelle, M.; Kuzina, D.; Lorenz, C.; Corgne, A. Description of the Calama Area Meteorite Collection (Atacama Desert, Chile). Meteorit. Planet Sci. 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlotzka, F. A Weathering Scale for the Ordinary Chondrites. Meteoritics 1993, 28, 460. [Google Scholar]

- Matsnev, M.E.; Rusakov, V.S. SpectrRelax: An application for Mössbauer spectra modeling and fitting. AIP Conf. Proc. 2012, 1489, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domracheva, N.E.; Pyataev, A.V.; Manapov, R.A.; Gruzdev, M.S. Magnetic Resonance and Mössbauer Studies of Superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles Encapsulated into Liquid-Crystalline Poly (propylene imine) Dendrimers. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 3009–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattagupta, S.; Blume, M. Stochastic theory of line shape. I. Nonsecular effects in the strong-collision model. Phys. Rev. B 1974, 10, 4540–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulova, N.Y.; Lyutoev, V.P.; Astahova, I.S.; Ignat’ev, G.V.; Kulikova, K.V.; Lysyuk, A.Y.; Makeev, B.A.; Sandula, A.N.; Simakova, Y.S.; Filippov, V.N.; et al. Mineral-petrographic and geochemical characteristics of the oxidized chondrite (Atakama, Chile). Vestn. Geosci. 2020, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosewich, E. Chemical analyses of meteorites: A compilation of stony and iron meteorite analyses. Meteoritics 1990, 25, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).