Abstract

The southern elderberry (Sambucus australis Cham. & Schltdl.), whose berries have highlighted functional properties, is native to temperate regions of eastern South America and is found growing spontaneously at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (RECS) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. This study aimed to describe the development of the flower bud to ripe fruit of S. australis in the agro-ecological conditions of the RECS, evaluate the different floral phases in relation to climatic factors, and identify the visiting insects that could act as potential pollinators. Flowers have all the organs to classify them as hermaphrodites; functionally, some flowers have shortly stamens without pollen and others have a non-functional ovule. Male and female flowers exhibited substantial synchronization, with the appearance of button flowers and anthesis phases occurring either simultaneously or very closely. On the other hand, it adapts to climatic changes that may occur by modifying the dates of the start of flowering and the maximum expression of the anthesis phase. Rainfall significantly influenced the opening of flower buds, the number of flowers in anthesis, and the harvest of the fruits of this species. Visiting insects which could perform pollination have been identified.

1. Introduction

Native and underutilized plants are increasingly recognized for their potential as natural alternatives to synthetic nutraceutical compounds and chemicals. They offer a diverse range of bioactive compounds that have been used ancestrally by local populations but were abandoned in modern times in favor of commercial products. However, there is a new interest in their valorization due to their important contribution to situations of hunger and malnutrition [1]. However, these wild plants require further studies to fully exploit their sociocultural, economic, and nutritional potential, particularly in relation to their reproductive cycle and their growth habitat.

The genus Sambucus, which is distributed worldwide, holds significant potential for both health-related and dietary applications. This potential lies in various parts of the plant, including the leaves, flowers, and fruits. The fruits are commonly known as “elderberries” [2,3] and are typically processed into jellies, wine, or other food products, rather than consumed fresh [4]. Moreover, the growing consumer interest in natural and health-promoting foods presents promising opportunities that are driving innovation in the food industry. Sambucus australis, also known as the southern elderberry, is native to temperate regions of eastern South America. Its range extends into parts of Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Bolivia, and possibly Peru. In Argentina, it is found from the northwest to Buenos Aires Province [5].

Although some traditional uses have been documented and certain physicochemical aspects of its fruits have been described, like the morphological traits and bioactive compounds [6], there is limited information regarding the floral phenology of S. australis, including the synchronization between male and female flowers and the influence of climatic factors on its reproductive cycle. In fact, Murriello et al. [7] report only the flowering period of this species in Buenos Aires Province. In response to this gap, we have conducted long-term phenological studies aimed at elucidating the species’ reproductive cycle and determining which environmental factors might disrupt it. Within Buenos Aires Province, S. australis can be found in several locations, among which the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (RECS) is particularly notable. This 350 hectare reserve was established on land reclaimed from the Río de la Plata—an area once filled with rubble and polluted waters which was naturally reclaimed. Native vegetation slowly colonized the site until it eventually transformed the landscape into a thriving ecosystem. Today, RECS stands as a native flora and fauna reserve in the heart of the city. In 2005, it was designated a “Ramsar Site” by the Ramsar Convention, which promotes the conservation of wetlands worldwide. It is precisely within this environment that S. australis has found favorable conditions to grow and spread naturally. However, the changes in climate that the planet is undergoing could influence the growth and development of this species, which is why we hypothesize that interannual variation in rainfall/temperature will shift onset and peak anthesis and that bio-morphological markers (pollen size and ovule number) will covary with water availability.

The objectives of this study were to (i) describe the development of the flower bud to ripe fruit of S. australis in the agro-ecological conditions of the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires Province); (ii) evaluate the different floral phases of this species in order to monitor its phenology—from the appearance of the flower bud to fruit ripening—in relation to climatic factors; and (iii) identify the visiting insects that could act as potential pollinators.

2. Materials and Methods

Plant material and growing conditions: Plants growing spontaneously at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (RECS) (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 34°36′27.09″ SL, 58°21′17.21″ WL, 14 m.a.s.l.) were selected at random and were permanently labeled (n = 24). Flower buds at different stages were collected from August to November. Each of their anthophilous species were studied in particular.

Button flowers (E) (n = 10) preserved in FAA were used to measure pollen grains (n = 10) and ovule number (n = 10) per ovary loculus from each genotype (n = 24) using a Leica DM 2500 microscope 11-5435-0175 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Polar and equatorial diameters were measured for each pollen grain, and the average of these two measurements was then calculated. The measurements were taken with a micrometer installed in the eyepiece, which is related to the stage micrometer to obtain the measurement in micrometers. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and Tukey’s test.

Flowering phenology was determined through the morphological changes observed in flower buds until fruit formation. A phenological scale was previously developed according to a modification of the Fleckinger scale [8]. Phenological changes were recorded through the evaluation of each phase in each shrub by percentage once a week over three consecutive years (2022–2024), and the records were always carried out by the same person throughout the study period. In addition, visiting insects were registered. Fruit set was calculated for the three years studied using the relation of fruit number/button flower number in percentage. Data were analyzed by χ2 test.

Climate conditions: The area of the RECS is classified as warm and temperate. According to Köppen [9], this climate is classified as Cfa, i.e., temperate rainy climate.

Historical climate records show that RECS has a warm, relatively dry climate with distinct seasonal variations. In fact, January has the highest average maximum temperature at 29 °C and the highest average minimum at 19 °C, while July has the lowest average maximum temperature at 14 °C and lowest average minimum at 6 °C. Rainfall was highest in February, March, and October, with approximately 100 mm each, and lowest in June at 50 mm. Wind speed was highest in November at 11 mph and lowest in June at 8 mph. Cloud cover was highest in June at 54% and lowest in January at 39%.

Hourly data of mean temperature (°C), precipitation (mm), wind speed (mph), and cloudiness (%) were taken from the websites Meteoblue (ID: Buenos Aires, −34.610000, −58.380000, distance to RECS 2.5 km); Windguru (ID: Argentina—Capital Federal, Ins. Ind. Luis A. Huergo, −34.617, −58.3745, distance to RECS: 2.3 km); and the Argentine National Meteorological Service (ID: AEROPARQUE AERO, Capital Federal, −34.5575, −58.4157, distance to RECS 7.6 km) for 2022–2024. Precipitation was evaluated as monthly accumulation of waterfall. Cloudiness was considered only for the daily spring period and calculated as hours of cloud cover in percentage through the following scale: 0–20% sunny days, 21–80% partly cloudy, and more than 80% cloudy. Data were analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s test.

3. Results

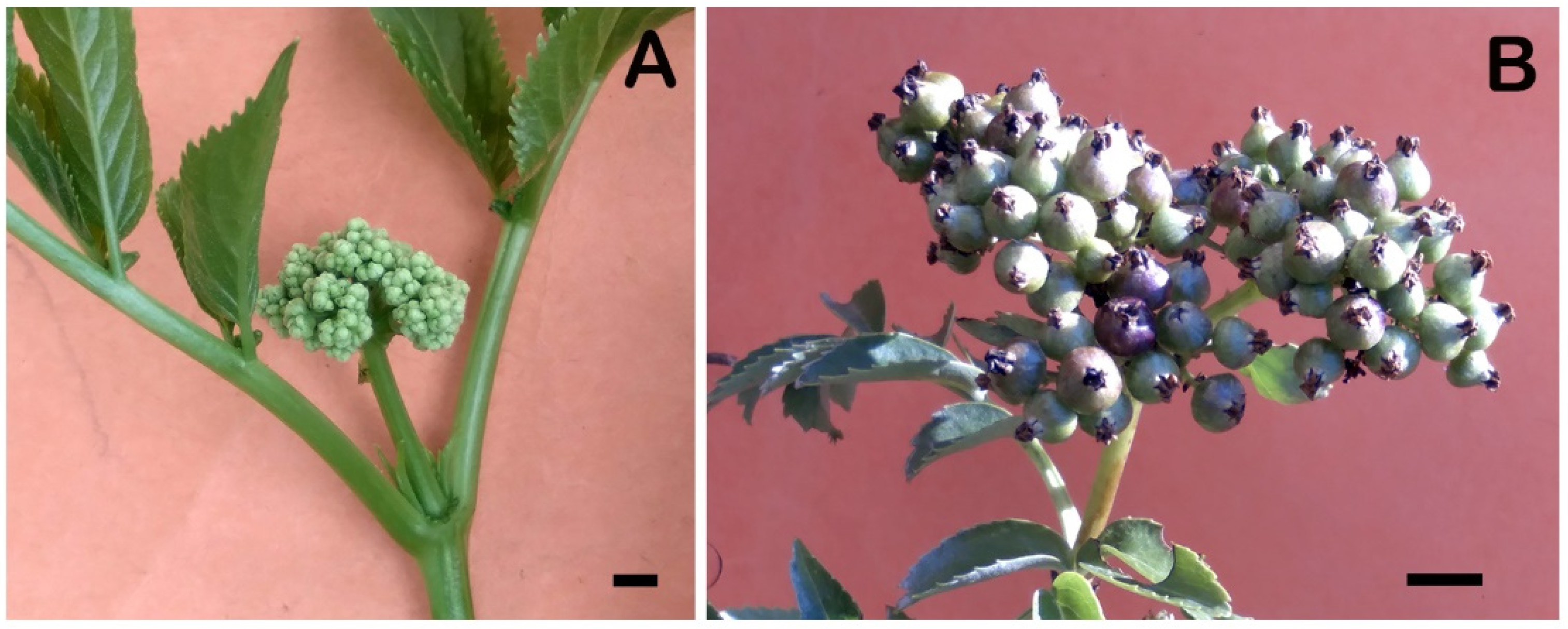

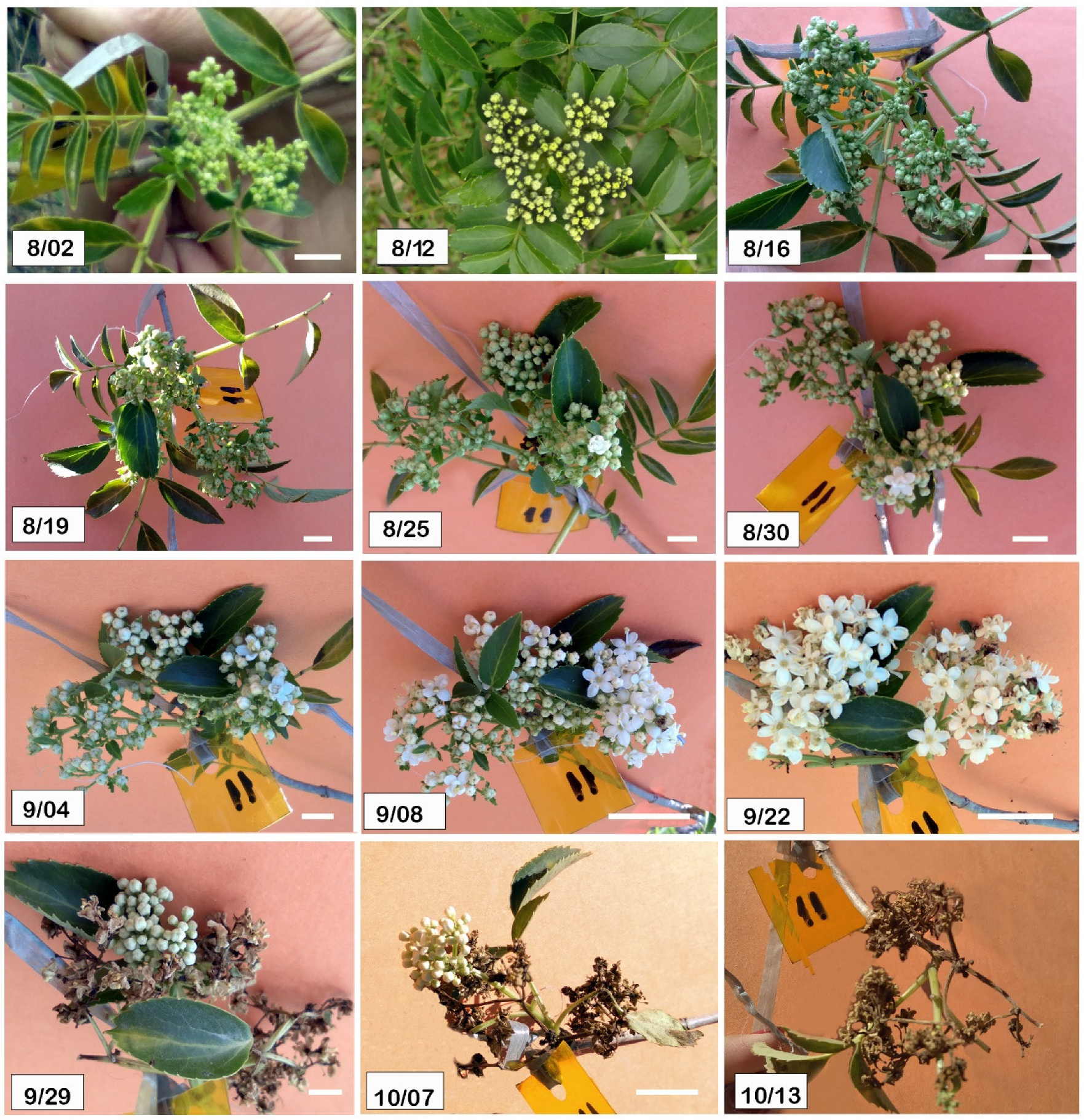

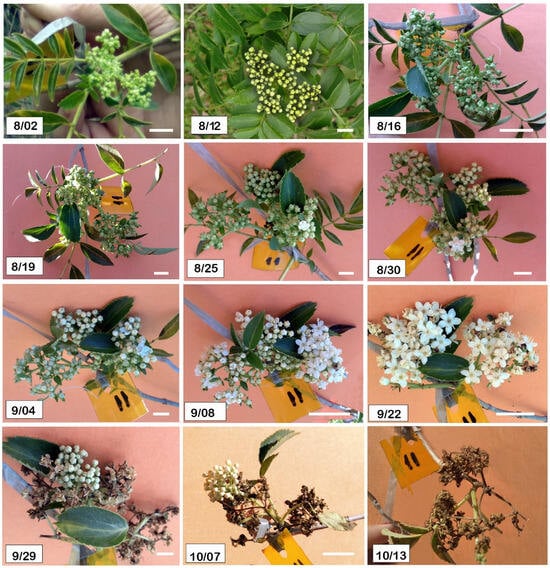

Floral phenology: Seven floral phenological stages (B, C, D, E, F, G, and H) were identified during flowering (Figure 1). The process begins with the appearance of green flower buds at the stem apex, where the flowers are still attached to each other (Figure 2A). Anthesis begins when the petals start to separate, exposing the stamens, and ends when the corolla is fully expanded (Figure 1F). In stage G, the petals fall or exhibit necrosis (Figure 3, 9/29). Finally, fruit formation (phase H) is recognized when the receptacle widens (Figure 2B). The evolution of a female and a male inflorescence over the same period is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Macroscopic differences became evident from 29 September onward. In the female flowers, the receptacles are thickened and the petals droop, while in the male flowers, the petals remain dried.

Figure 1.

Flower buds of Sambucus australis in different stages of development. Bar = 10 mm. Letters indicate the different phases B–F.

Figure 2.

Inflorescence of Sambucus australis. (A) Button flowers (phase B); (B) fruits (phase H). Bar = 20 mm.

Figure 3.

Development of a female inflorescence of Sambucus australis from 2 August to 13 October grown at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires). Bars = 20 mm.

Figure 4.

Development of a male inflorescence of Sambucus australis from 2 August to 13 October at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires). Bars = 20 mm.

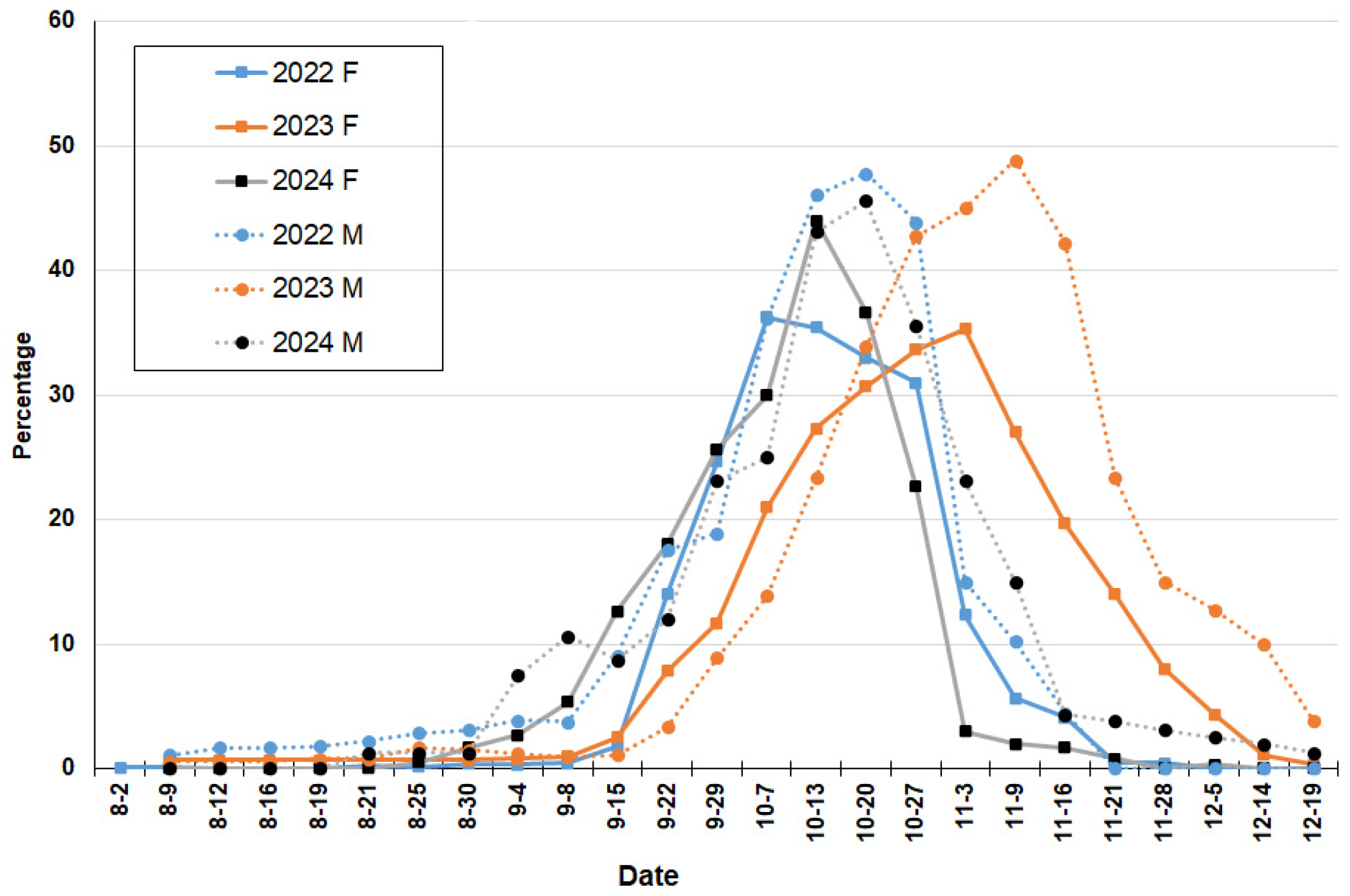

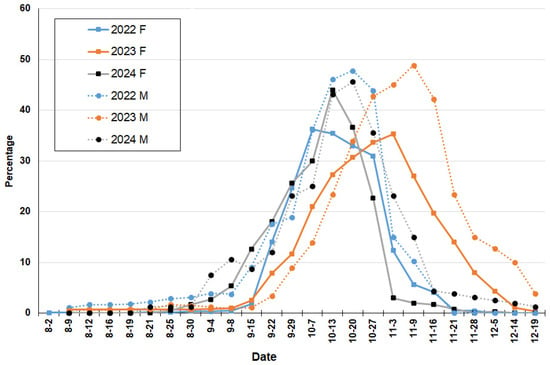

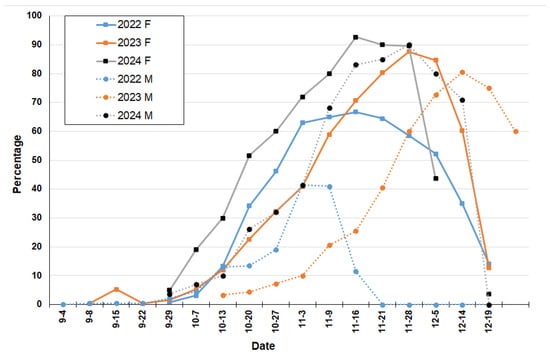

Flowering phenology during the spring periods of the three-year study was observed (Table 1). During 2022, 11.92% of button female flowers were recorded on 2 August. This year, the anthesis stage began on 20 September with 10% and increased to a maximum of 36.25% by 7 October (Figure 5). Fruit growth commenced at the end of September, with 99% fruit set recorded on 7 November (Figure 6). Male flowers began anthesis phase on 15 September at 9.11% and rose to a maximum of 47.78% by 20 October (Figure 5). Between the maximum peaks of anthesis and fruit formation, 27 days were recorded.

Table 1.

Details of the dates on which the different phenological events of Sambucus australis plants were observed according to their sexual behavior (female or male) during the three years of study at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024.

Figure 5.

Anthesis phase of Sambucus australis registered at Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024 years. Full line and letter F for female flowers and dotted line and letter M for male flowers.

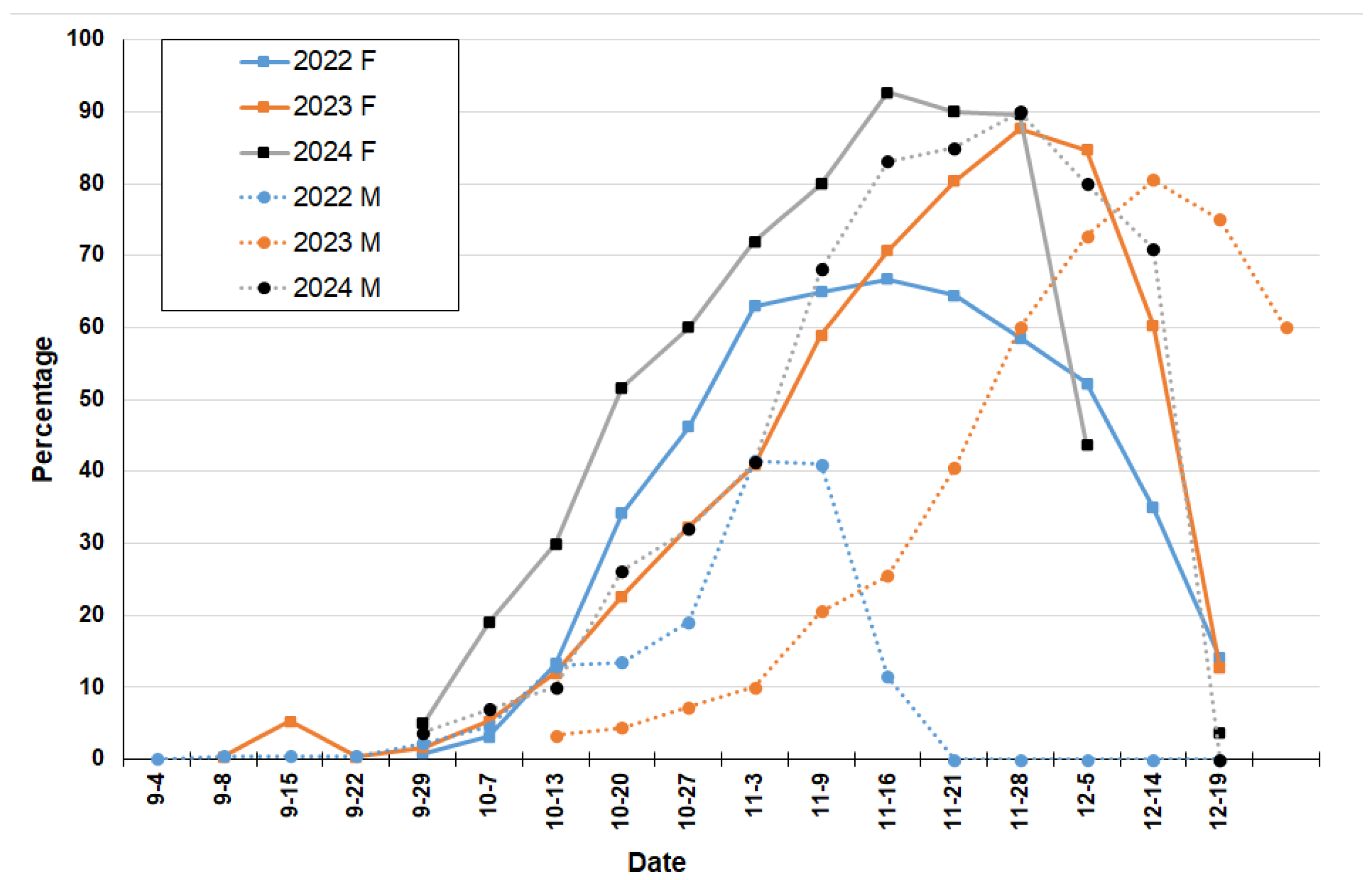

Figure 6.

Fruit formation (H phase) and necrotic flowers (G phase) of Sambucus australis registered at Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024 years. Full line and letter F for female flowers and dotted line and letter M for male flowers.

On 29 August 2023, the first button female and male flowers were recorded (11.67%). The anthesis stage started on 29 September with 11.67% and increased to a maximum of 35.31% by 3 November (Figure 5). Fruit growth began on 13 October (12%), with 87.67% fruit set registered on 28 November (Figure 6). The male flowers entered the anthesis phase a few days later on 7 October (13.89%) and increased to a maximum of 48.89% by 9 November (Figure 5). Necrotic flowers emerged on 3 November (10%), reaching 80.56% on 14 December (Figure 6). In this year, 25 days were documented between the maximum peaks of anthesis and fruit formation.

In the third year of the study, the first button female and male flowers were computed on 16 August (10%). The anthesis stage began on 15 September (12.67%), with the highest value recorded on 13 October (43.13%) (Figure 5). In 29 September, some growing fruits were observed, and fruit set was maximum on 16 November with 92.67% (Figure 6). For male flowers, anthesis stage began on 8 September (10.63%) and increased to a maximum of 45.63% by 20 October (Figure 5). Necrotic flowers were first observed on 29 September, reaching 85% by 21 November (Figure 6). Finally, 34 days between the maximum peaks of anthesis and fruit formation were recorded.

Fruit set was significantly different between the 2022 and 2024 harvest (p = 0.041). In fact, fruit production in 2022 was 45% and 63% in 2024, while in 2023 it was 48%.

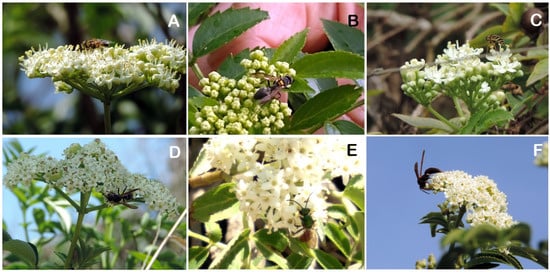

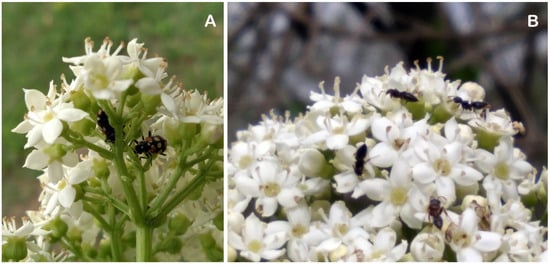

Several insects visiting this species were found. Among them different Hymenoptera, such as Apis mellifera bees (Figure 7A), Halíctidae sp. (Figure 7E), the sweat bee, and wasps of the genus Polybias, known locally as “camoatí” (Figure 7C,D,F). All these insects visit the flowers even before anthesis, promoting the opening of the petals with the movement of their legs and proboscis. In addition, different butterflies such as Libytheana carinenta (Figure 8A), Doxocopa laurentia (Figure 8B), and Riodina lysippoides (Figure 8C) were observed. Other insects found on the flowers were beetles (Eriopis connexa) (Figure 9A) and ants (Figure 9B).

Figure 7.

Hymenoptera observed during the floral period of Sambucus australis at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024. (A) Apis mellifera; (B–D,F) Polybias sp.; (E) Halíctidae sp.

Figure 8.

Butterflies observed during the floral period of Sambucus australis at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024. (A) Libytheana carinenta; (B) Doxocopa laurentia; (C) Riodina lysippoides.

Figure 9.

Beetles (A) and ants (B) visiting flowers of Sambucus australis at the Reserva Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) during 2022–2024.

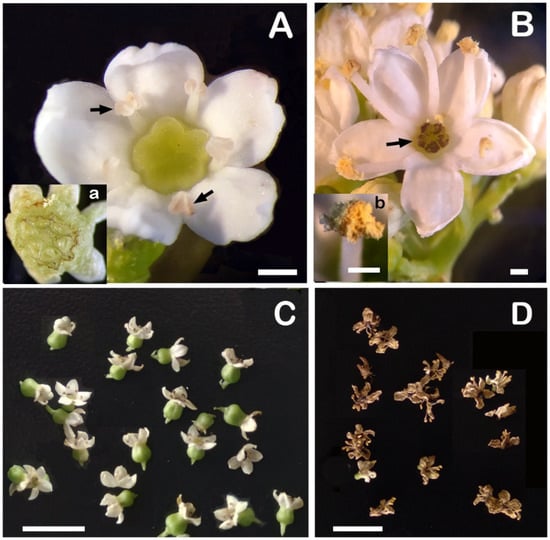

Flower description: Flowers analyzed in the three-year study were clustered in inflorescence terminal corymbs. Each flower was composed by a calyx with 5 elliptical green fused sepals, corolla with 5 white, oval to elliptical fused petals and very labile (Figure 10). Androecium with 5 stamens, with filaments variable in length. Gynoecium with an inferior ovary soldered to the coronary tube is globose-papilose and has a short style. The stigma is five-lobed, rarely four-lobed or six-lobed, greenish in color, covered by a nectar drop. It also has well-defined carpels, and one seminal rudiment per loculus with axial placentation. Gynoecium is generally pentacarpellate and pentalocular, with 90.4 to 92.7% of flowers with pentacarpellate flowers among 2022 and 2024 years, less frequently tetracarpellate and rarely hexacarpellate (Figure 10A(a)). Number of carpels was correlated with other flower anthophiles, i.e., flowers with 4 carpels had 4 sepals, 4 petals and 4 stamens. Ovule number was similar for the three years of study (4.9–4.96).

Figure 10.

Flowers of Sambucus australis. (A,C) female flower; (B,D) male flower; (A) with sterile anthers (arrows); (A(a)) transversal section of the ovary with 6 ovules; (B) with necrotic stigmata (arrow); (B(b)) detail of dehiscent anther with pollen grains; (C) flowers with thickened receptacles; (D) flowers with dry petals. Bars: (A,B) = 2 mm; (C,D) = 10 mm.

Sizes of the pollen grains in S. australis were different according to the year studied. In fact, the average diameter measured in 2022 was 19.5 microns, significantly different (p ≤ 0.001) to the 21.3 and 21.0 microns registered in 2023 and 2024, respectively.

Although the flowers have all the organs to classify them as hermaphrodites, functionally, some flowers have shortly stamens without pollen and others have a non-functional ovule, therefore there are shrubs with female flowers (Figure 10A) and shrubs with male flowers (Figure 10B). These differences are seen from the wilting and falling of petals, where the female ones are shown with thickened receptacles (Figure 10C) and the male ones with dry petals (Figure 10D). Shrubs with functional hermaphrodite flowers are rarely found. In fact, only 16% of these types of shrubs recognized as hermaphrodite produced fruit. Female flowers have indehiscent anthers without pollen while male flowers are dehiscent (Figure 10B(b)).

Climate conditions: Significant differences in climate parameters were observed across the three years of study. Average annual mean temperatures varied notably (p ≤ 0.001), with values recorded at 17.5 °C, 18.18 °C, and 17.64 °C for the years 2022, 2023, and 2024, respectively.

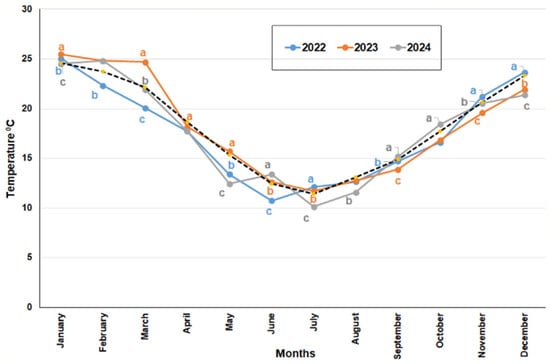

In the period from 2022 to 2024, 2023 had the highest average monthly mean temperatures for the first half of the year, while September and November were significantly cooler compared to the other two years (Figure 11). Year 2022 overall had significantly lower temperatures, except for July, November, and December, which were higher than the averages of 2023 and 2024. In 2024, only June, September, and October were significantly warmer than the other two years. Notably, 2022 had the lowest overall average mean temperatures, and November and December 2022 saw the highest average monthly mean temperatures of 21.2 °C and 23.6 °C, respectively. In 2023, June and September recorded the highest temperatures of 13.4 °C and 15.2 °C, respectively. In 2024, January, March, and May saw significant increases in average temperatures, measuring 25.7 °C, 24.7 °C, and 15.7 °C, respectively (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Average monthly media temperature values measured in °C registered in the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) for the three years studied. Different letters for one month indicate significant differences. Pointed line refers to the average historical monthly value.

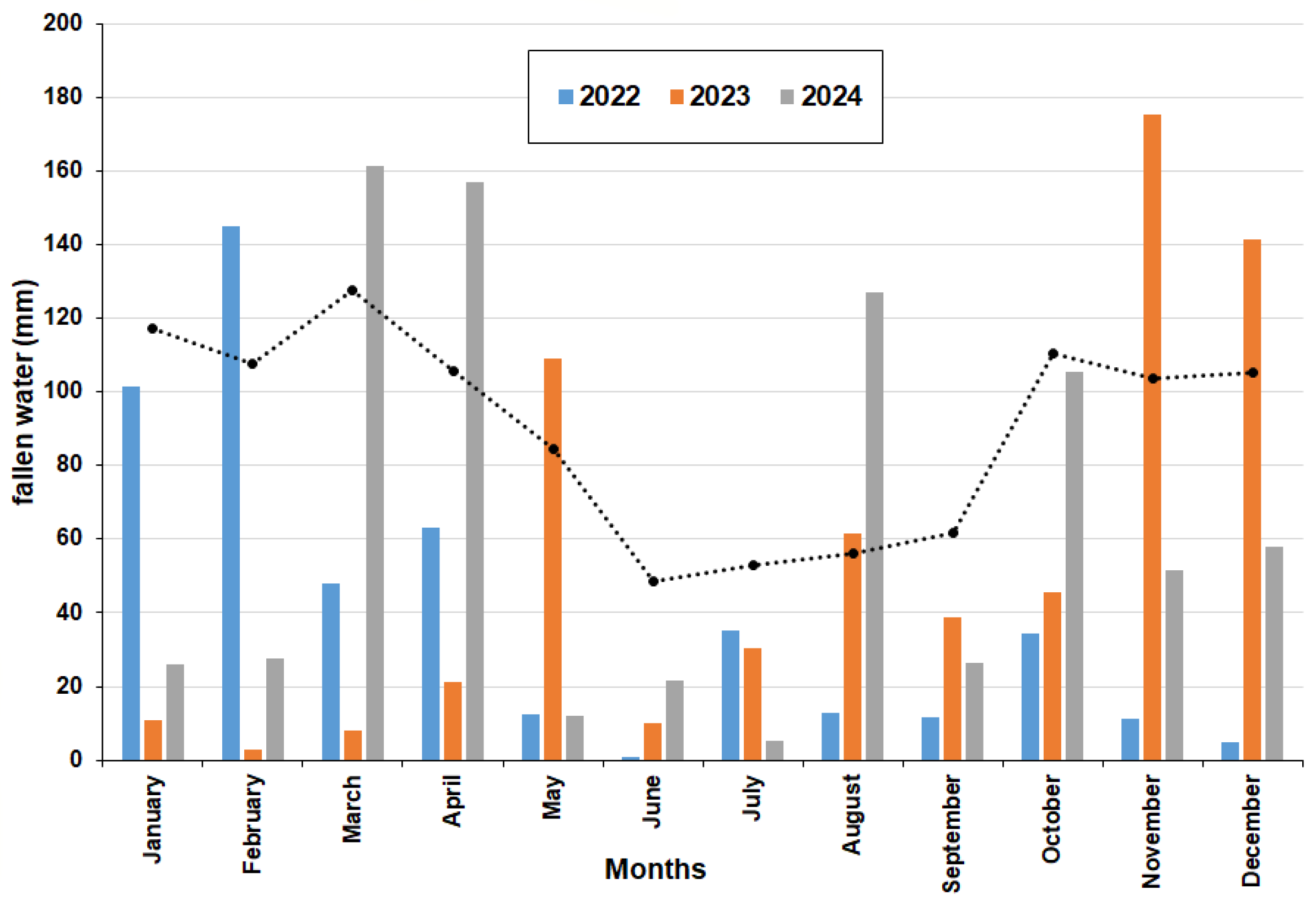

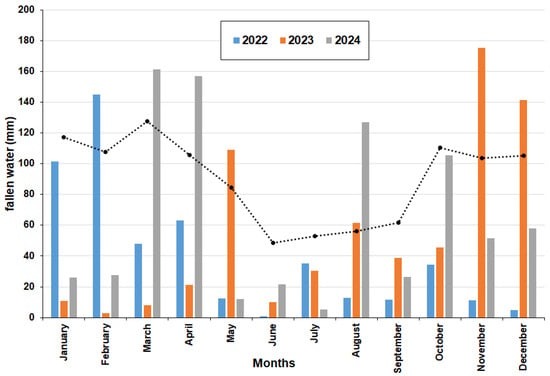

During 2022, rainfall was significantly lower (489 mm) compared to the years 2023 and 2024, which recorded 655 mm and 778 mm, respectively. Significant differences in precipitation were observed among the three years in most months except for June, July, and September (Figure 12). Comparison of the records of the three years with respect to historical values shows significant differences in all months (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Amount of rainfall measured in mm for every month at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) for the three years studied. Pointed line refers to the average historical monthly value.

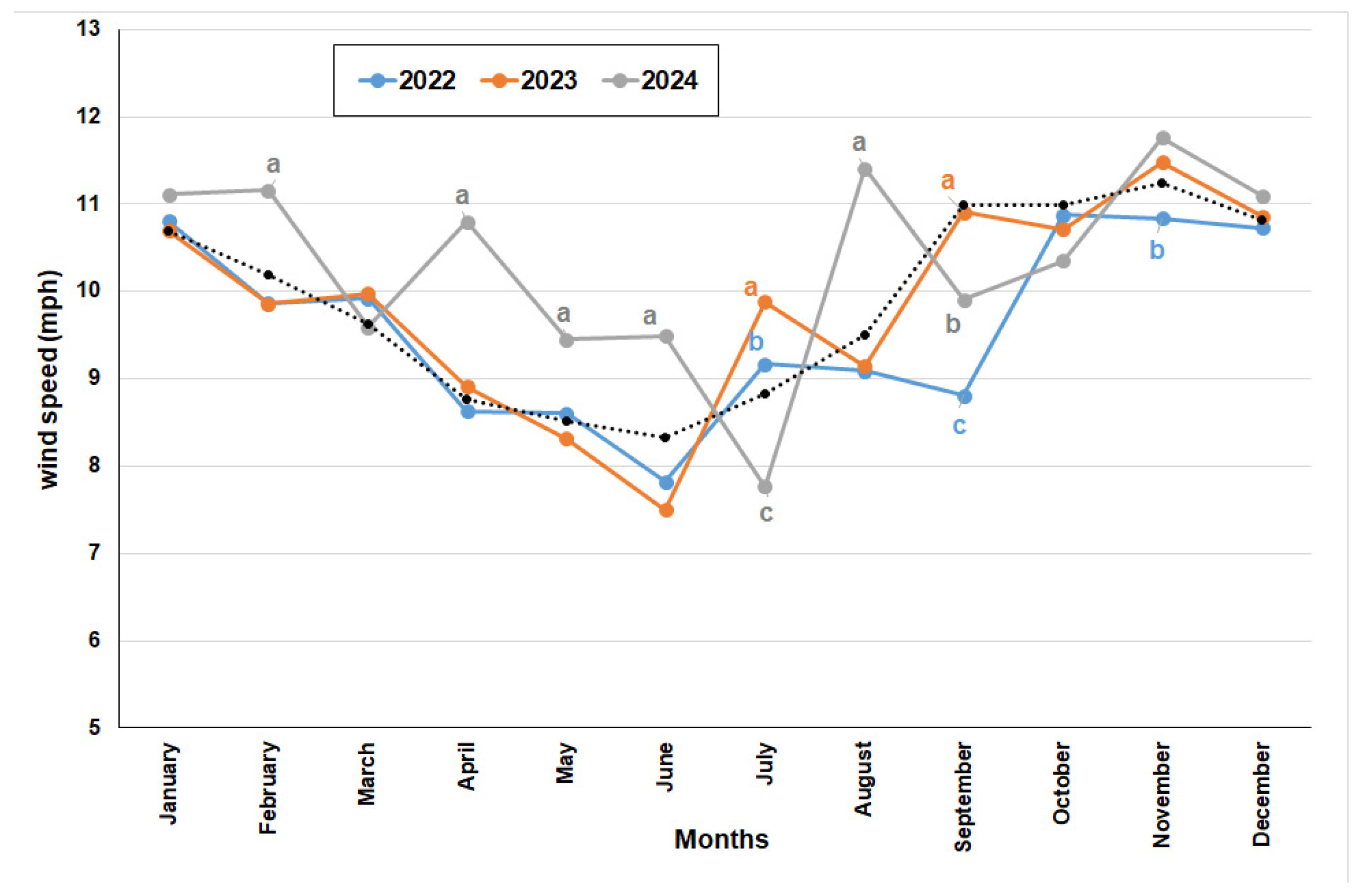

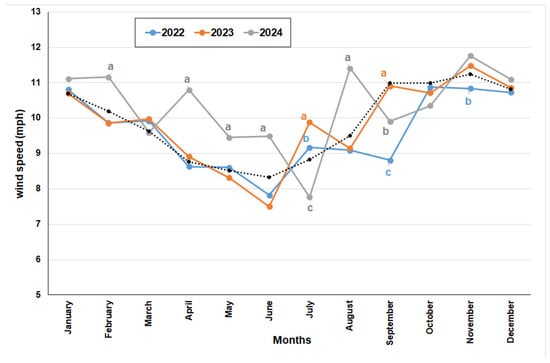

On the other hand, average wind speeds between the years studied differed significantly (p = ≤0.001). In fact, average wind speed was 7.75, 8.0, and 8.47 for 2022, 2023, and 2024, respectively. During 2024, February, April, May, June, and August were significantly windier months. On the contrary, July and September were significantly windier for 2023. The wind speed of the year 2022 did not show significant differences except for the months of July, September, and November (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Average monthly wind speed values measured in mph at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) for the three years studied. Different letters for one month indicate significant differences. Pointed line refers to the average historical monthly value.

Average daily cloud cover was calculated. Spring 2022 saw the sunniest days from August to December (zero–20 clouds), while in 2023, the days were cloudiest in September and December (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average cloud cover during the daily spring period, evaluated as a percentage at the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur (Buenos Aires) for the three years studied. Days with less than 20% cloud cover are considered sunny, between 20 and 80% are considered partly cloudy, and more than 80% are considered cloudy. Different letters for each category and one month indicate significant differences by χ2 test.

4. Discussion

Flowers of S. australis are small and arranged in corymbs, similar to those of S. nigra (European elder or black elderberry) and S. canadensis (American elderberry). However, some authors describe the inflorescence of S. nigra as an umbel [10]. Flowers of S. australis grown in the RECS exhibited the same characteristics described by Scopel [11]. Notably, Scopel highlights that flowers can have varying filament lengths in the stamens, akin to those found in RECS-grown flowers, which are dioecious. Interestingly, some plants grown in the RECS displayed flowers with six floral parts, a characteristic not mentioned by Scopel.

As previously noted, this species exhibits dioecious behavior concerning its flowers, necessitating assistance from insects for pollination. During the flowering period, various Hymenoptera, including honeybees (Apis mellifera) and sweat bees, were observed actively visiting elderberry flowers. As is the case with many other species, honeybees are recognized as pollinators, while sweat bees are particularly effective in pollinating fruit species such as melon and mango [12,13]. Although we did not conduct a detailed record of the time spent and specific activity of each insect, nor the count of pollen grains on their bodies, we can infer that Hymenoptera are their primary pollinators. Additional, wasps of the genus Polybia were frequently found visiting the flowers of S. australis. These wasps feed on nectar, and while collecting it the pollen from the anthers adheres to their bodies allowing them to transport it from flower to flower. Thus, they can also be considered pollinators, as has been studied in Passiflora [14]. Similarly, butterflies such as Doxocopa laurentia, Riodina lysippoides and Libytheana carinenta, also perform important pollination roles in several other species [15,16].

Most of these insects visit the flowers before anthesis, likely attracted by the fragrant scents and pheromones emitted by the elderberry flowers [17,18]. Conversely, this species exhibits allopathic strategies to attract entomophile pollinators [19].

The presence of Eriopis connexa (beetles) was also noted; they are predators of common crop pests such as aphids, psyllids, and mites. Although they do not participate in pollination, they serve as a natural form of pest control, reducing the need for chemical pesticides [20]. Furthermore, ants were observed stealing nectar but do not contribute to pollination [21].

Since this species has flowers with functional sexes on different plants, synchronization of male and female flowers is crucial for ensuring effective pollination and, ultimately, a successful harvest. Fortunately, S. australis exhibited substantial synchronization, with the appearance of button flowers and the phases of anthesis occurring either simultaneously or very closely. Moreover, the number of open male flowers exceeded that of the female ones, ensuring an abundant supply of pollen for the insects to carry out their pollination tasks. All this information was gathered through the floral phenology which is correlated with environmental factors such as climate, seasons, and interactions with pollinators.

As has already been demonstrated in other studies, climatic conditions significantly influenced both flowering phenology and insect activity, making their study crucial [22,23]. Although historical records indicate a sustained increase in annual rainfall over recent decades, the year 2022 was characterized by the “La Niña” phenomenon, leading to prolonged droughts, while 2023 was marked by the opposite phenomenon, “El Niño”, resulting in increased rainfall. In fact, quarterly values calculated by Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) from July–August–September 2020 to December–January–February 2023 were all greater than −0.5 (−0.5 to −1.3), confirming the effect of “La Niña”. Conversely, in the spring of 2023 the values were greater than 0.5 (0.5 to 2.0), corresponding with the “El Niño” effect [24]. These two phenomena explain the monthly differences observed during the study period compared to historical values.

According to data from the Environmental Protection Agency, average annual temperature and precipitation have increased significantly over the past 60 years. In Buenos Aires city, cold days are becoming less cold, temperatures are rising, and heat waves are more frequent and longer-lasting. From 1960 to 2018, the average annual mean and maximum temperature increased by 1 °C, while the average minimum temperature rose by up to 1.7 °C. Furthermore, the frequency of heat waves doubled between 2010 and 2018 compared to those recorded in the 1990s.

In contrast, during the studied period (2022–2024) it was observed that the average spring temperatures in 2023 were cooler compared to the other two years. This temperature difference was reflected in the floral phenology of the species, as it took 35 days for the flowers to reach peak anthesis from the start of flowering, i.e., more than twice as long as the previous year. Additionally, the time between the maximum peaks of anthesis and fruit formation was the shortest, lasting only 25 days. The peak of anthesis occurred 27 and 21 days later than in 2022 and 2024, respectively. These findings suggest that the timing of the anthesis phase was significantly influenced by temperature, as reported by Matsuda and Higuchi [23] for Annona cherimola.

Moreover, the lower number of open flowers and reduced fruit production in 2022 compared to the other years could be attributed to the scarce spring rainfall associated with the “la Niña” effect, which, according to the ONI, began in the first quarter of July–August–September 2020. The water stress observed during the flowering period may have caused several issues, such as a decrease in the number of floral buds produced, their abortion, changes in morphology, or a reduction in nectar production, all of which negatively affect plant–pollinator interactions. Notably, a decrease in the size of the pollen grain was also found. In our case, although some analyses were performed to evaluate the germinability of the pollen grain, results were too erratic, so they were not presented. However, it is known that seed production can be affected by water availability and also depend on the amount and quality of pollen deposited, as observed by the authors of [25].

Lastly, water stress can alter fruit development, ultimately leading to a decrease in final fruit production [26,27].

Although differences in wind speed were observed between the years studied, these variations did not adversely affect the activity of pollinating insects. In fact, wind speeds exceeding 12 mph can cause honeybees to cease visiting flowers. Even when temperatures and sunlight are favorable, rain and wind speeds above 15 mph can lead honeybees to stop foraging [28].

Cloud cover can significantly influence the activity of pollinator insects, especially bees, as it reduces sunlight, making it more challenging for pollinators to locate and navigate to flowers. Indeed, climate, particularly during the spring flowering period, directly influences pollinator activity and, consequently, fruit production [29,30]. In this case, differences in cloudiness observed between the three years of study did not correlate with fruit production.

Finally, S. australis plants grown in their natural environment sensitively respond to changes in climatic factors with variations in flower production and modifications of the floral period, which in turn affect fruit production. These results underscore the importance of phenological studies with native species that often serve as highly effective indicators due to their sensitivity to environmental changes, adjusting their growth and reproductive patterns in response to these events. This has been studied in 29 native plant species of California by Solakys-Tena et al. [31] and in Berberis microphylla [32] where it was observed that climate change in Ushuaia (Argentina) significantly altered the reproductive phenology of the species as well as that of its pollinators.

5. Conclusions

S. australis grown spontaneously in the RECS completes its biological cycle normally, showing substantial flowering synchronization between plants that behave as females and others as males. Pollination is performed by a variety of insects that inhabit the area. Phenological plasticity observed across three years suggests the species can adjust flowering timing under interannual weather variability; however, multiyear and multi-site data are needed to assess long-term adaptive responses to climate change.

On the other hand, S. australis responds to climatic changes that may occur by modifying the dates of the start of flowering and the peak of the anthesis phase. Rainfall significantly influenced the opening of flower buds, the number of flowers in anthesis, and the harvest of the fruits of this species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and M.E.A.; Methodology, S.R., A.V.S. and M.E.A.; Software, S.R.; Validation, S.R. and A.V.S.; Formal analysis, S.R.; Investigation, A.V.S. and M.E.A.; Resources, S.R. and M.E.A.; Data curation, S.R. and A.V.S.; Writing—original draft, S.R.; Writing—review and editing, S.R., A.V.S. and M.E.A.; Visualization, S.R. and M.E.A.; Supervision, S.R.; Project administration, S.R. and M.E.A.; Funding acquisition, S.R. and M.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by PICTO MINCYT-UM 0003 and PIP CONICET 11220200102292CO.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Donno, D.; Turrini, F. Plant foods and underutilized fruits as source of functional food ingredients: Chemical composition, quality traits, and biological properties. Foods 2020, 9, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hummer, K.E.; Pomper, K.W.; Postman, J.; Graham, C.J.; Stover, E.; Mercure, E.W.; Aradhya, M.; Crisosto, C.H.; Ferguson, L.; Thompson, M.M.; et al. Emerging Fruit Crops. In Fruit Breeding, Handbook of Plant Breeding; Badenes, M., Bryne, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 99–147. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Szablewski, T.; Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Świerk, D.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Krejpcio, Z.; Suchowilska, E.; Tomczyk, Ł.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. Sambucus nigra extracts–natural antioxidants and antimicrobial compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atehortúa, B.M.G.; Galvis, M.M.B.; Quirama, J.F.R. Características, manejo, usos y beneficios del saúco (Sambucus nigra L.) con énfasis en su implementación en sistemas silvopastoriles del Trópico Alto. RIAA 2015, 6, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, A.V.; Arena, M.E.; Radice, S. Sambucus australis Cham. & Schltdl. “Sauco”, a wild and native species from South America: A review for its valorization as a wild food plant with edible and medicinal properties. Acta Bot. Bras. 2024, 38, e20230185. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, A.V.; Povilonis, I.S.; Borroni, V.; Pérez, E.; Radice, S.; Arena, M.E. Unveiling the Potential of Southern Elderberry (Sambucus australis): Characterization of Physicochemical Properties, Carbohydrates, Organic Acids and Biophenols. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murriello, S.; Arturi, M.; Brown, A.D. Fenología de las especies arbóreas de los talares del este de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. Ecol. Aust. 1993, 3, 025–031. [Google Scholar]

- Fleckinger, J. Phenologie et arboriculture frutière. Bon Jardinier. 1955, 1, 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Das geographische system de Klimate. In Handbuch der Klimatologie; Köppen, W., Geiger, G., Eds.; Verlag Gebruder Borntrager: Berlin, Germany, 1936; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, S.; de Brito, E.S.; de Oliveira Silva, E. Elderberry—Sambucus nigra L. In Exotic Fruits; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Scopel, M. Análise Botânica, Química e Biológica Comparativa Entre Flores das Espécies Sambucus nigra L. e Sambucus Australis cham. & Schltdt. e Avaliação Preliminar da Estabilidade. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Federal de Río Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo Gómez, S.; Ornosa, C.; Selfa, J.; Guara, M.; Polidori, C. Small sweat bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) as potential major pollinators of melon (Cucumis melo) in the Mediterranean. Entomol. Sci. 2016, 19, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Ghosh, S.; Khan, R.; Khan, A.A.; Perween, T.; Hasan, M.A. Role of pollination in fruit crops: A review. Pharma Innov. J. 2019, 8, 695–702. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.; Dambolena, J.S.; Zunino, M.P.; Galetto, L. Nectar characteristics and pollinators for three native co-occurring insect pollinated Passiflora (Passifloraceae) from central Argentina. Int. J. Plant Reprod. Biol. 2012, 4, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Reddi, C.S.; Bai, G.M. Butterflies and pollination biology. Proc. Anim. Sci. 1984, 93, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfar, M.; Malik, M.F.; Hussain, M.; Iqbal, R.; Younas, M. Butterflies and their contribution in ecosystem: A review. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016, 4, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pachura, N.; Gavahian, M.; Jałoszyński, K.; Surma, M.; Szumny, A. Changes in bioactive and aroma compounds in flower elderberry as affected by innovative drying method. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renou, M. Pheromones and General Odor Perception in Insects. In Neurobiology of Chemical Communication; Mucignat-Caretta, C., Ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- Basas-Jaumandreu, J.; de Las Heras, F.X.C. Allelochemicals and esters from leaves and inflorescences of Sambucus nigra L. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 30, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgaertner, J.U.; Frazer, B.D.; Gilbert, N.; Gill, B.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Ives, P.M.; Nealis, V.; Raworth, D.A.; Summers, C.G. Coccinellids (Coleoptera) and aphids (Homoptera): The overall relationship. Can. Entomol. 1981, 113, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrant, E.O., Jr.; Fiedler, P.L. Flower defenses against nectar-pilferage by ants. Biotropica 1981, 13, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.; Evans, M.; Scheele, B.; Encinas-Viso, F.; Florez Fernandez, J.; Lumbers, J.; Cunningham, S.A. Influence of climate, weather and floral associations on pollinator community composition across an elevational gradient. Oikos 2024, 12, e10688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Higuchi, H. Effects of temperature and humidity conditions on anthesis and pollen germinability of cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.). Trop. Agricu. Dev. 2015, 59, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Prediction Center-Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). Available online: https://origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Recart, W.; Campbell, D.R. Water availability affects the relationship between pollen intensity and seed production. AoB Plants 2021, 13, plab074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, A.; Lovelli, S.; Di Tommaso, T.; Perniola, M. Flowering, growth and fruit setting in greenhouse bell pepper under water stress. J. Agron. 2011, 10, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, A.; Camacho, G.; Gomez-del-Campo, M. Spring deficit irrigation promotes significant reduction on vegetative growth, flowering, fruit growth and production in hedgerow olive orchards (cv. Arbequina). Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 248, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, G.; Harris, C.; Eaton, C.; Wright, P.; Jackson, E.; Goulson, D.; Ratnieks, F.F. Gone with the wind: Effects of wind on honey bee visit rate and foraging behaviour. Anim. Behav. 2020, 161, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, K.; Meyer, S.T.; Thomas, F.; Frank, A.; Weisser, W.W.; Bekessy, S. Small-scale habitat conditions are more important than site context for influencing pollinator visitation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 703311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbassioon, A.; Yearlsey, J.; Dirilgen, T.; Hodge, S.; Stout, J.C.; Stanley, D.A. Responses in honeybee and bumblebee activity to changes in weather conditions. Oecologia 2023, 201, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solakis-Tena, A.; Hidalgo-Triana, N.; Boynton, R.; Thorne, J.H. Phenological Shifts Since 1830 in 29 Native Plant Species of California and Their Responses to Historical Climate Change. Plants 2025, 14, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radice, S.; Giordani, E.; Arena, M.E. Effect of Climatic Variations in the Floral Phenology of Berberis microphylla and Its Pollinator Insects. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).