Abstract

Inefficient fertilization practices frequently take place in orchards in Dangshan County, leading to substantial changes in soil properties and pear tree growth. To comprehensively evaluate the long-term impact and identify limiting factors, this study assessed the effects of 30-year fertilization across different soil layers in “Dangshansuli” pear orchards. In May 2020, 30 soil samples were collected from a long-term fertilized plot and an unfertilized sandy control. The analyses focused on the physicochemical properties, mineral elements, heavy metals, chemical compound diversity, and allelopathic effects. The results showed that long-term fertilization significantly reduced soil pH (e.g., from 8.1 to 7.3 in the topsoil) and increased the content of soil organic matter by about 3.7-fold in the 0–20 cm layer. The contents of available potassium, exchangeable calcium, and magnesium in fertilized soil were optimal for pear growth, whereas available iron was deficient. Although fertilization led to the accumulation of heavy metals (Cu, Hg, Ni, Cr, As, Mn), their concentrations remained within national safety limits. The number of chemical compounds detected in fertilized soil was over 40% higher than in the control. Allelopathy tests indicated that 0.18 mmol·L−1 of octadecane strongly inhibited the root growth of “Shanli” (Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim.) tissue-cultured seedlings by more than 50%. These findings provide a scientific basis for optimizing fertilization strategies in “Dangshansuli” pear orchards.

1. Introduction

According to FAOSTAT (2016), China has become the largest consumer of worldwide [1]. The application of nitrogen fertilizer in China accounts for 30% of the worldwide total; however, the utilization rate is only about 35% [2]. This pattern of inefficient resource use is widespread in orchard management, where growers of crops such as pears and apples often apply excessive fertilizers, predominantly mineral-based ones with limited organic supplementation, in pursuit of higher yields [3,4]. Such practices can lead to significant resource wastage, soil degradation, and environmental pollution [5,6]. Additionally, long-term impacts of continuous mineral fertilization, which may induce profound changes in soil chemical properties, including pronounced acidification, nutrient imbalance, and the gradual accumulation of heavy zinc (Zn) and chromium (Cr) originating from fertilizer impurities [7]. Furthermore, these effects are often stratified with soil depth, influencing root zone environments differently [8].

In parallel, the application of organic amendments like livestock and poultry manure has gained attention as a sustainable alternative [9,10]. However, long-term manure application may also pose risks, such as elevating concentrations of toxic heavy metals (e.g., Hg, Cu, Zn, and Cr) and promoting the accumulation of allelochemicals in soil [11,12,13,14,15]. The latter relates to the phenomenon of allelopathy, where plants or amendments release biochemicals that influence the growth and development of themselves or neighboring plants. Allelopathy is increasingly being recognized as a potential contributor to soil sickness and replanting problems in orchards [16,17]. For instance, in systems like black walnut and banana orchards, specific secondary metabolites (e.g., phenolic acids, terpenoids, alkanes) have been shown to inhibit seedling growth and reduce root vitality [18,19]. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of long-term fertilization must extend beyond basic nutrients to include potential contaminants and shifts in soil allelochemical profiles, which together influence soil–plant feedbacks.

Pears are one of the most important economic fruit crops worldwide. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, China accounts for 67.3% of the worldwide pear cultivation area [20]. The “Dangshansuli” pear, a local major cultivar from Dangshan County, Anhui Province, has a cultivation history of more than 200 years and is renowned for its juiciness, pleasant flavor, and sweet aroma. Currently, it represents one-quarter of China’s total pear production [21]. However, decades of intensive fertilization in these orchards are reported to have triggered soil acidification and nutrient imbalances [22]. While the effects of long-term fertilization have been studied in other fruit systems such as apples [23] and highbush blueberries [24], a comprehensive evaluation focusing specifically on the ‘Dangshansuli’ pear system is lacking. Crucially, the integrated effects on soil chemical properties across different depths—encompassing nutrient status, heavy metal accumulation, and the diversity of chemical compounds with potential allelopathic activity—remain poorly documented.

This study aims to systematically evaluate the impacts of over 30 years of fertilization on the physicochemical and biochemical properties of soil across different depths in a “Dangshansuli” pear production orchard. Specifically, we compared mineral elements, heavy metals, and organic compound profiles between soils that had received long-term fertilization and an unfertilized control area maintained for over 30 years. We hypothesized that long-term fertilized soil would exhibit (1) significant acidification and altered nutrient availability, (2) elevated but safe-level concentrations of heavy metals, and (3) a distinct profile of organic compounds with demonstrated allelopathic potential, compared with an unfertilized control. By characterizing these changes in mineral elements, heavy metals, and organic compound diversity, this study seeks to provide a scientific basis for developing improved fertilization strategies that mitigate adverse effects on soil health and support the sustainable management of “Dangshansuli” pear orchards and similar intensive fruit-growing systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

The experiment was performed in a commercial “Dangshansuli” pear orchard located within the Dangshan County Fruit Germplasm Resource Garden (34°42′ N, 116°35′ E; 47.8 m above sea level), Suzhou City, Anhui Province, China. The region has a warm temperate monsoon climate. According to data from the local meteorological station, the annual average temperature is 14.3 °C, and the mean annual precipitation is 730 mm [25]. The year 2020, when sampling occurred, exhibited a typical pattern with a warm, rainy growing season. The orchard was established on flat terrain with well-drained sandy soil. The tree planting density was 14 plants per mu, with a spacing of 6 × 8 m between trees and rows. For this study, two adjacent plots within the orchard were selected as controls: a long-term fertilized plot and an unfertilized control plot. These two plots shared an identical soil type, topographic features, and management history, with fertilization serving as the sole variable. In the experimental plot, fertilization was applied annually following local conventional practices. The primary fertilizer used was a commercially available NPK compound fertilizer with an average application rate of approximately 750 kg per mu per year. The control plot received no fertilizer of any kind throughout the entire period.

2.2. Sample Collection and Physicochemical Property Analysis

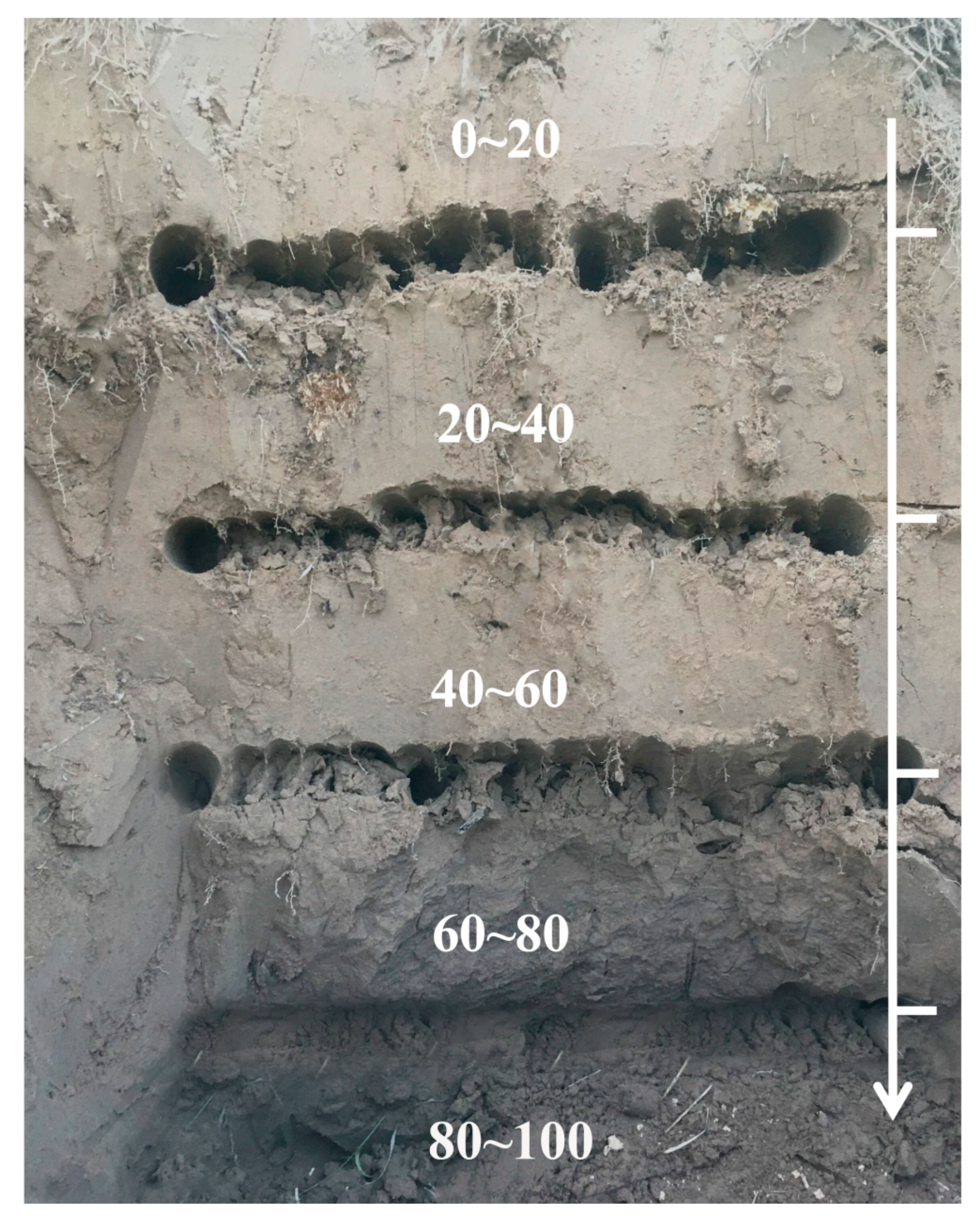

To capture representative soil conditions under each treatment, three “Dangshansuli” pear trees (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. grafted on Pyrus betulifolia Bunge rootstock) per plot were selected in May 2020. The selected trees were of uniform age, canopy size, and growth vigor, located in the central part of each plot to minimize edge effects. For each tree, soil samples were collected from five symmetrical points around the trunk using a soil auger (Figure 1). Samples were taken from five consecutive depth layers: 0–20, 20–40, 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100 cm. For each tree and each depth, the five spatial subsamples were thoroughly homogenized to form one composite sample per tree per depth. Consequently, for each treatment, we had n = 3 independent biological replicates (trees) × 5 depths = 15 composite samples in total. Each of these 30 composite samples (2 treatments × 3 trees × 5 depths) was processed and analyzed separately. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, where 500 g of soil from each composite sample was air-dried and passed through a 60-mesh sieve for subsequent physical and chemical property analysis.

Figure 1.

Soil profile under a “Dangshansuli” pear orchard. Schematic diagram of the soil sampling location.

2.3. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties

To measure soil pH, 10 g of air-dried soil was mixed with 50 mL of ultrapure water in a 200 mL conical flask and stirred magnetically for 2 min. The flask was then sealed with sealing film and allowed to stand for 30 min before measurements were taken. After calibration with standard solutions, the electrode was inserted into the supernatant, and the pH value was read directly from the meter ST3100 (OHAUS Instrument (Changzhou) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and recorded.

A total of 1 g of soil was placed into a test tube, and organic carbon in the soil was oxidized using the sulfuric acid–potassium dichromate method [26]. The mixture was heated in an oil bath, and the remaining potassium dichromate was titrated with ferrous sulfate. The content of organic matter was calculated based on the amount of potassium dichromate consumed.

The minerals and trace elements were determined using wet analysis and ICP OES analytical methods [27]. Heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, Pb) were extracted with HCl and determined using ICP-OES, as was measured using hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectrometry, and Hg was assessed using cold-vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry [28].

2.4. Determination and Analysis of Soil Organic Compounds

To achieve the extraction of soil organic compounds, 50 g of soil was accurately weighed into a 250 mL triangular flask, to which 150 mL of ethyl acetate was added. The mixture was shaken overnight in an oscillating incubator (Shanghai Boxun Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 25 °C. The sample was ultrasonicated for 1 h and kept in the dark for 24 h. The extract was then filtered through filter paper in a vacuum filtration system, and the process was repeated three times. The combined extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator (Tianjin automatic scienceinstrument Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) at 40 °C and passed through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. Analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatography system (Agilent Technologies (China) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) coupled with an Agilent 7000 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies (China) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and a 1 μL aliquot was injected via an Agilent autosampler [29]. The column temperature was programmed as follows: the initial temperature was 50 °C, which was increased to 280 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min and then held at 280 °C for 15 min. The carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Electron ionization was applied with the following settings: interface temperature 250 °C, ion source temperature 230 °C, and quadrupole temperature 150 °C. The mass scanning range was m/z 35–500 with a scan speed of 0.3 s per full scan.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) data were processed using the NIST2008 mass spectral library. Compounds with a similarity match greater than 80% were considered to be identified. Quantification was performed using an internal standard method by adding a known amount of ribitol solution to each sample prior to extraction, with compound contents calculated based on their peak area ratios relative to the internal standard.

2.5. Seed Germination Assay

For the soil extract bioassay, 100 g of air-dried soil was used from each of the 30 samples. Fertilized and unfertilized soil samples were separately combined, placed in a triangular flask with 2 L of distilled water, and shaken overnight at 25 °C. After full extraction, the mixture was filtered and concentrated to obtain a 1 g·mL−1 extract. Moreover, Pyrus betulifolia Bunge seeds (a common pear rootstock, chosen for its high germination uniformity) of uniform size and plumpness were selected for the germination tests. Each treatment included 5 replicates, with 25 seeds per replicate. The seeds were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol and rinsed three times with sterile water. The sterilized seeds were then placed in 90 mm Petri dishes lined with filter paper, and 3 mL of the soil extract was added. The control group received the same volume of distilled water. Dishes were incubated in a climate-controlled chamber (Darth Carter Technologies Co., Ltd., Hefei, China) at 25 ± 2 °C, and the extract was replenished daily. Germinated seeds (radicle ≥ 1 cm) were recorded daily for 7 days, and on the 8th day, the seedling growth [root length + shoot length] was measured. Germination rate (GR, %): (Final number of germinated seeds/Total seeds) × 100. Germination index (GI): Σ(Gt/Dt), where Gt is the number of seeds germinated on day t, and Dt is the corresponding day number. Vigor index (VI): GI × Mean seeding growths. These formulas for germination rate, germination potential, germination index, and vitality index were adapted and calculated as previously described [30].

2.6. Allelopathy Assay on Pear Seedlings

To assess the phytotoxic effects of specific compounds identified in the soil, a bioassay was conducted using tissue-cultured “Shanli” (Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim.) seedlings. Uniform tissue-cultured seedlings were transferred to MS medium supplemented with filter-sterilized benzoic acid or octadecane (common phenolic and alkane allelochemicals, respectively) [31]. The test concentrations for octadecane in the allelopathy assay were determined with reference to their in situ soil concentrations. Field measurements indicated levels of approximately 0.06 mmol·L−1 and 0.01 mmol·L−1 in the 20–40 cm layer, respectively. As there was a graded series of 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 3×, and 5×, these values were therefore tested. This design, guided by both the field data and reports of bioactive concentrations in the literature, led to the use of octadecane concentrations at 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.12, 0.18, and 0.30 mmol·L−1. Phenotypic assessment of the seedlings was performed after a 7-day incubation period.

2.7. Data Analysis

Data were compiled using Microsoft Excel and analyzed with SPSS19 software. To assess the soil properties, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to evaluate the main effects and interaction of treatment and depth. Where a significant interaction (p < 0.05) was found, simple main effects were analyzed. For germination and allelopathy assays, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare means across the treatments. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE).

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Soil pH and Organic Matter Following Fertilization in a “Dangshansuli” Pear Orchard

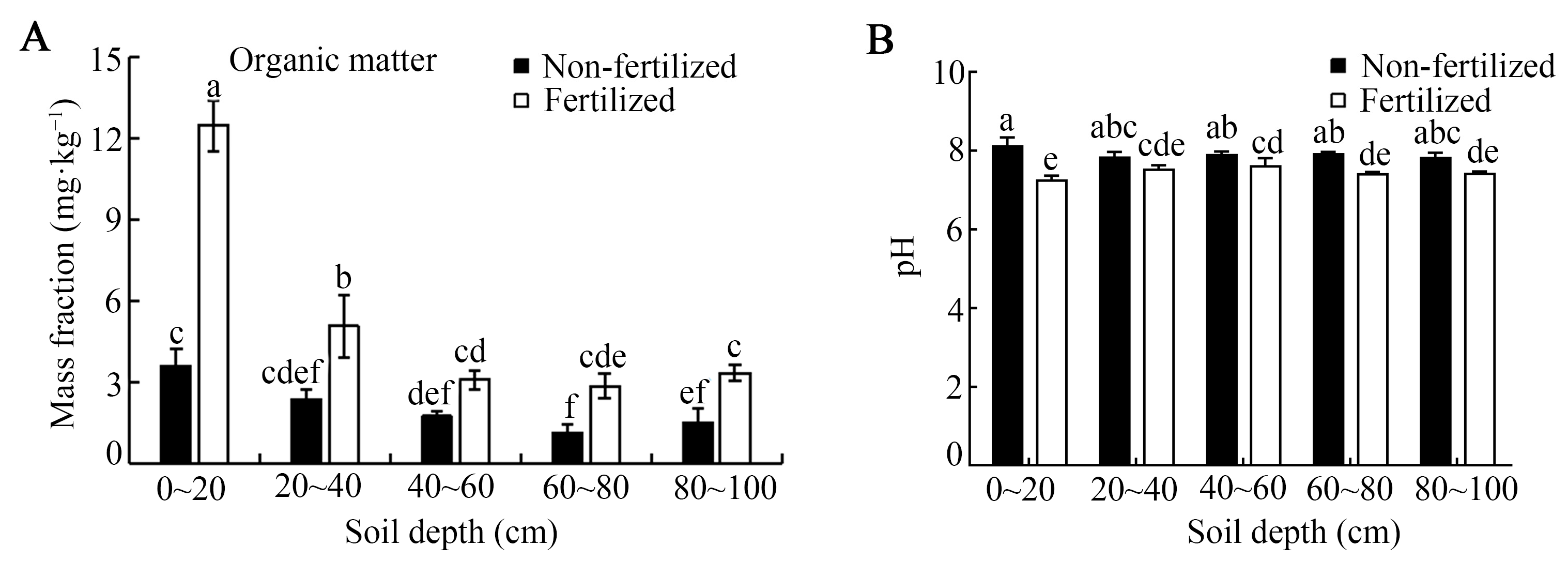

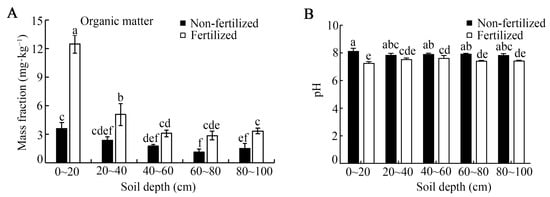

Long-term fertilization significantly altered soil properties, increasing organic matter (SOM) and decreasing pH, with both effects most pronounced in the surface layer (Figure 2). Relative to the unfertilized control, the SOM content was significantly higher in fertilized soil at all sampled depths except 40–60 cm. Notably, in the 0–20 cm layer, the SOM increased by approximately 3.7-fold (Figure 2A). Within the fertilized soil profile, the SOM content in the 0–20 cm layer was also significantly higher than that in the 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100 cm depths. Concurrently, soil pH showed significant acidification. In the 0–20 cm layer, pH decreased by about 0.8 units compared with the control (from ~8.1 to ~7.3), and this significant reduction persisted down to 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100 cm depth (Figure 2B). In contrast, the unfertilized control soil exhibited no significant variation in pH across the 20–40, 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100 cm profiles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Soil organic matter content (A) and soil pH (B) under long-term fertilization conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent replicates. Different lowercase letters above the error bars indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

3.2. Changes in Soil Macroelements Content with Fertilization

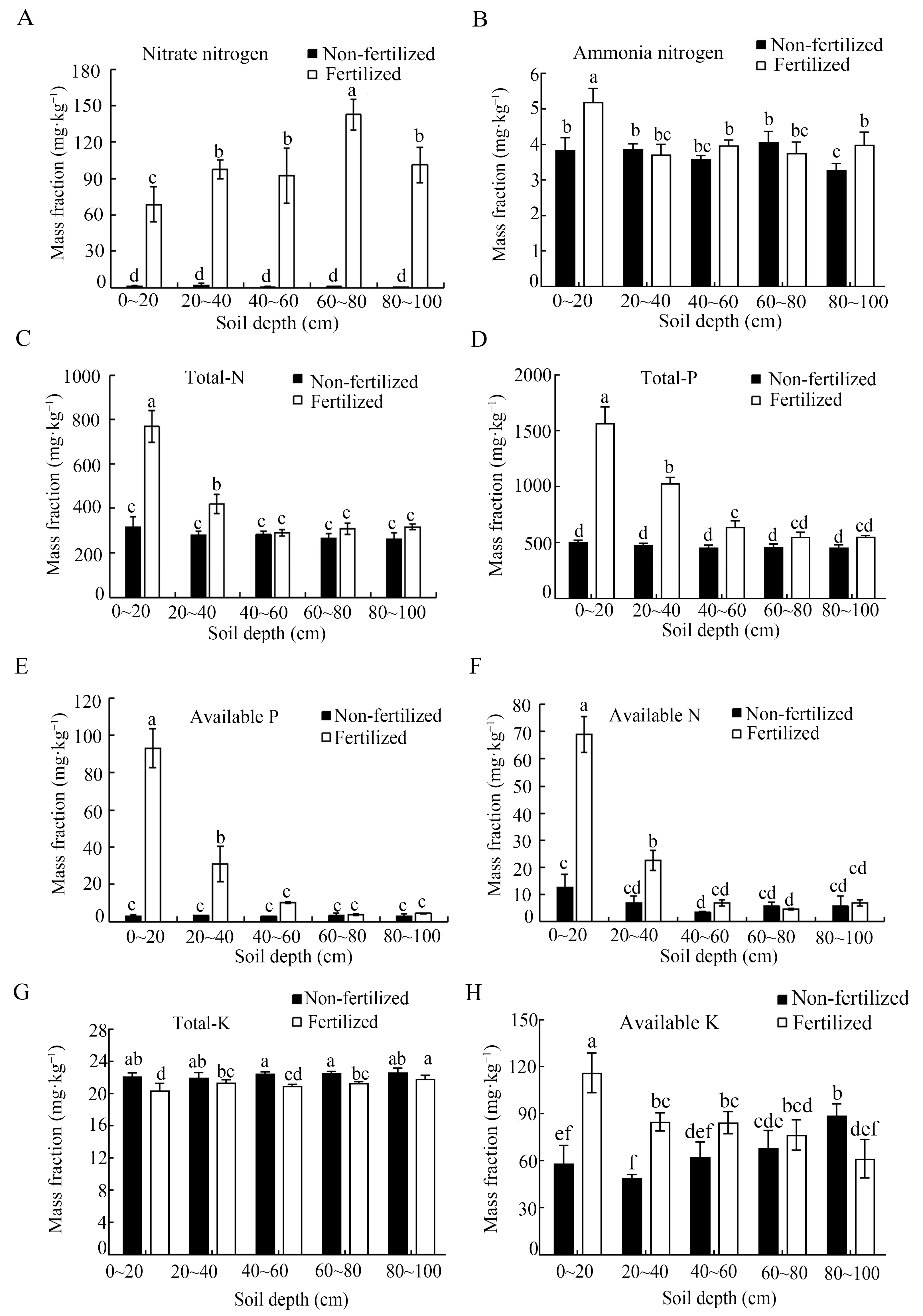

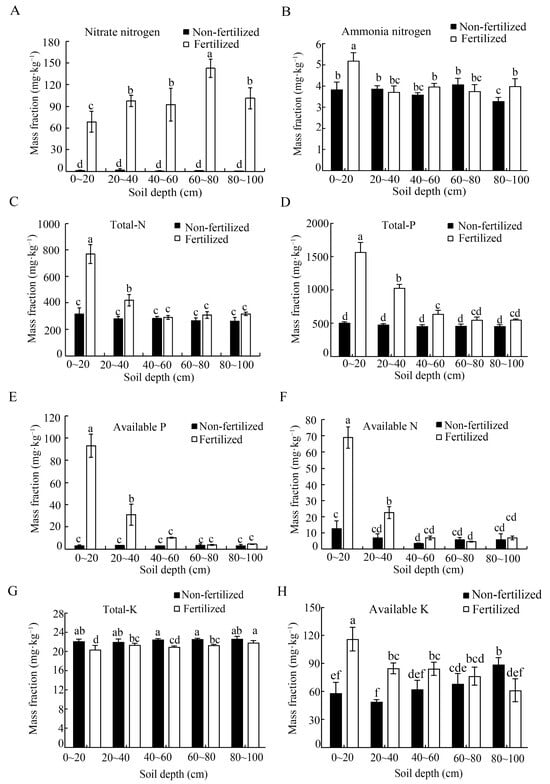

The nitrate NO3− content was significantly higher in the long-term fertilization soil than in the unfertilized control, with an increase of 48–157 fold. Similarly, the NH4+ content was significantly elevated in fertilized soil within the 0–20 cm and 80–100 cm soil layers, but there were no significant differences in the 20–40, 40–60 and 60–80 cm layers. The total nitrogen (N) content was also significantly higher in the fertilized treatment within the 0–40 cm layers, with no significant differences observed in deeper layers (Figure 3C). For total phosphorus (P), concentrations were significantly higher in fertilized soils within the 0–60 cm layers compared with the unfertilized control.

Figure 3.

Content of macroelements (A–H) across the different soil depths under long-term fertilization and unfertilized soil conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent replicates. Different lowercase letters above the error bars indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, as determined using Duncan’s multiple range test.

In contrast, total potassium (K) was lower in the fertilized soil than in the unfertilized control (Figure 3E,F), whereas the available K was significantly higher in the 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm layers under long-term fertilization conditions, and it was about 2-fold greater in the 0–20 cm layer compared with the control (Figure 3G,H). Exchangeable Ca showed a contrasting depth response. The concentration was higher in the fertilized soil at 0–20 cm, but it was significantly lower than the control in the 60–100 cm layers (Table 1). The available S content increased consistently with depth in fertilized soil and was markedly higher across all depths compared with the control, which showed minimal depth variation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Content of medium elements across the different soil depths under long-term fertilization conditions.

3.3. Trace Element Content Under Long-Term Fertilization

Trace elements are essential for normal plant growth, and their availability in soil can be altered through long-term fertilization practices. In this study, the content of available B was significantly higher under long-term fertilization conditions than in the unfertilized control across all soil layers (Table 2). Similarly, the available Fe and Cu were significantly elevated in the fertilized soil within the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers, although no significant differences were observed in soil at deeper layers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Trace element content with long-term fertilization at different soil depths.

In contrast, the effective Mn was significantly higher in soil under fertilization conditions only in the 0–20, 60–80, and 80–100 cm layers compared with those of the unfertilized soil. In addition, effective Zn was significantly greater in fertilized soil solely within the 0–20 cm layer, with no notable differences in the other depths (Table 2).

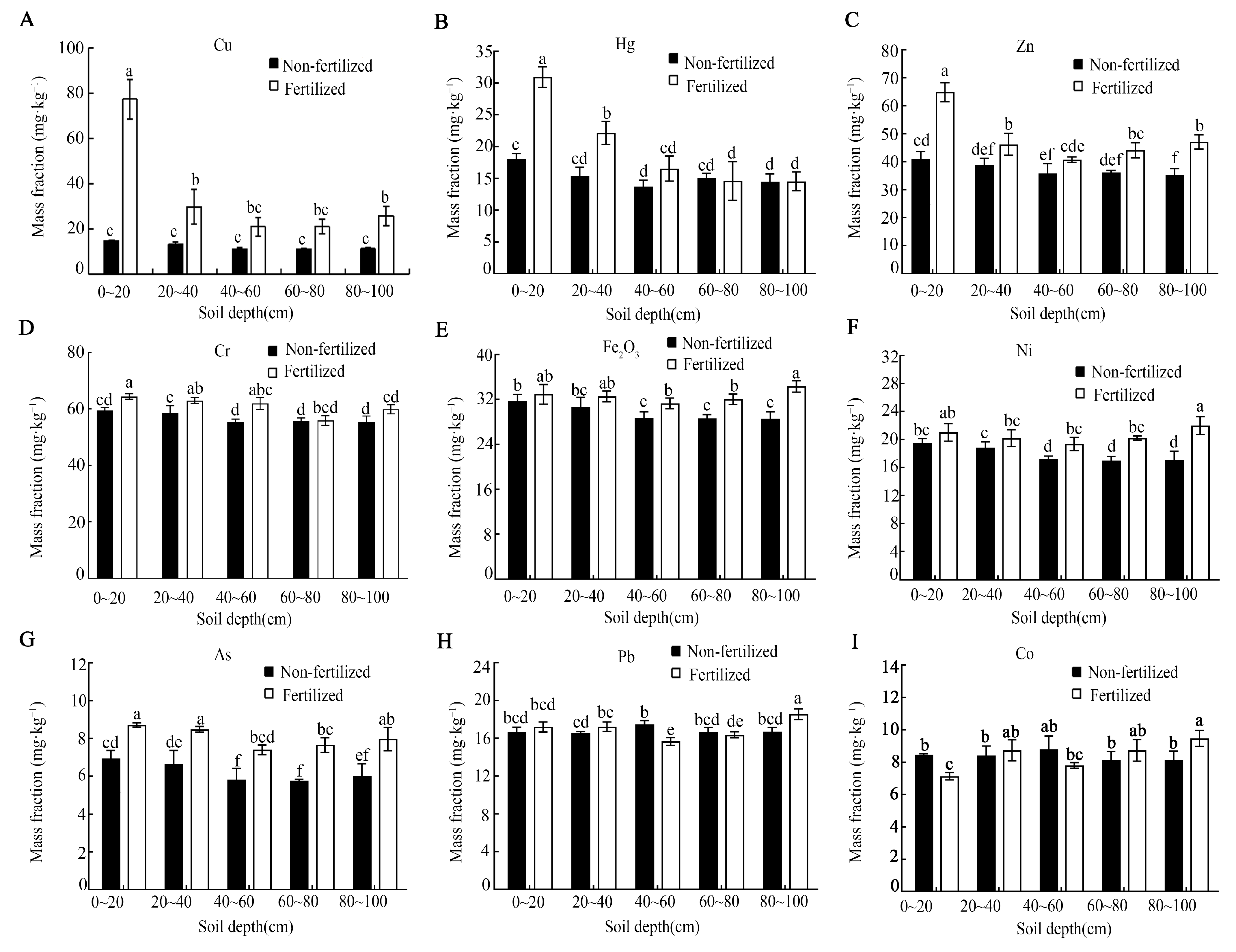

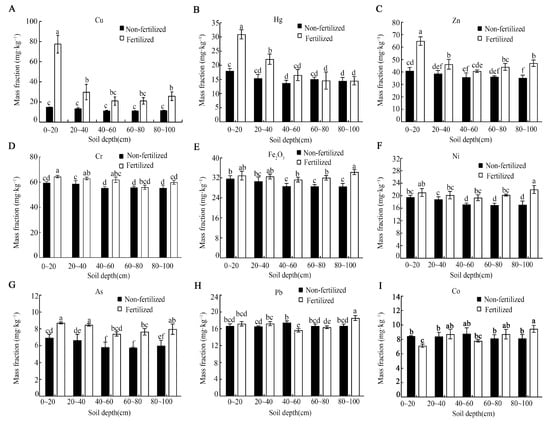

3.4. Soil Heavy Metal Content Under Long-Term Fertilization

Long-term fertilization resulted in the significant accumulation of several heavy metals in the soil profile, although all the measured concentrations remained below China’s soil environmental quality risk control standards (Figure 4). The contents of Cu, Hg, Zn, Cr, and As were significantly higher in fertilized soil, primarily within the 0–40 cm layers (Figure 4A–D,G). For instance, the Cu content in the 0–20 cm layer increased by approximately 5.3-fold compared with the control (Figure 4A). In contrast, the concentrations of Fe, Ni, and Pb in the 0–40 cm layer were not significantly affected by fertilization (Figure 4E,F,H). Interestingly, the Co content in the surface layer (0–20 cm) was notably lower in fertilized soil relative to the control.

Figure 4.

Heavy metal content (A–I) across the different soil depths under long-term fertilization conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent replicates. Different lowercase letters above the error bars indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

3.5. Soil Compound Profiles in the Fertilized and Unfertilized Soil Layers

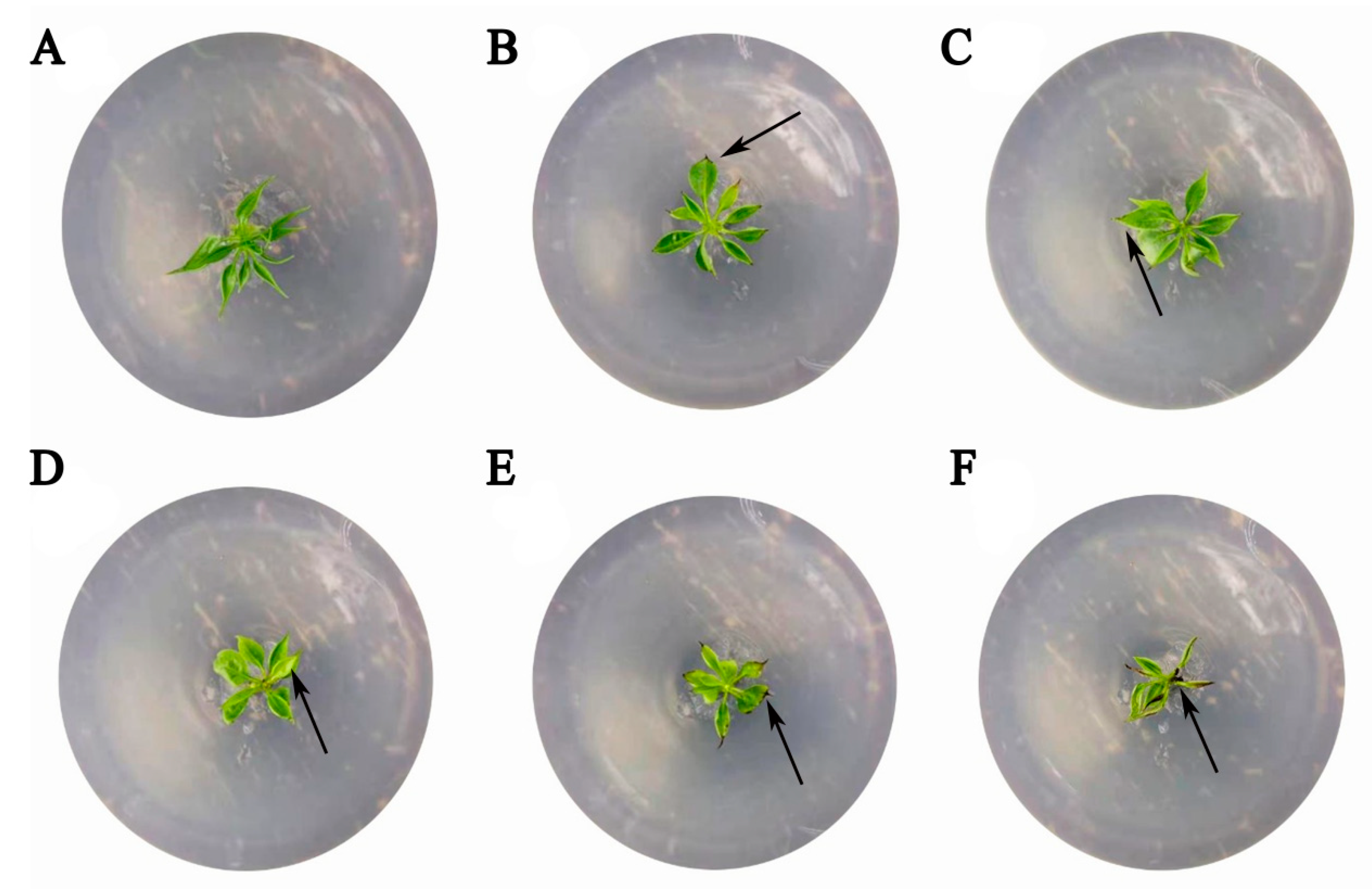

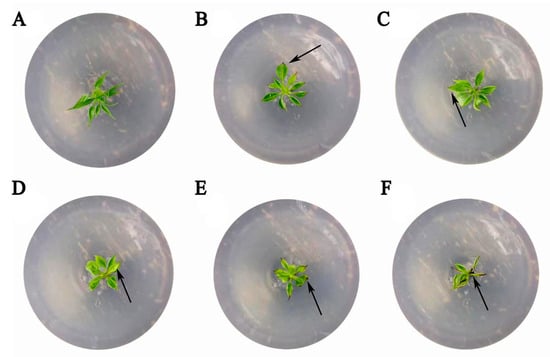

GC-MS analysis revealed that long-term fertilization altered the soil’s organic chemical profile. The diversity and relative abundance of detected compounds, particularly alkanes, were higher in fertilized soil compared with the control (Tables S1 and S2). To assess potential phytotoxicity, octadecane—a compound detected in fertilized soil—was tested on pear seedlings (Figure 5). Compared with the untreated control, the severity of inhibitory symptoms increased as the octadecane concentration rose. At 0.18 mmol·L−1, a distinct phenotypic response was observed (Figure 5A–E). while at the higher concentration of 0.30 mmol·L−1, the seedlings exhibited severe wilting and necrosis (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Phytotoxicity assessment of octadecane in pear tissue-cultured seedlings. Representative images showing (A) an untreated control seedling and (B–F) seedlings subjected to octadecane treatments at 0.03, 0.06, 0.12, 0.18, and 0.30 mmol·L−1. The arrows indicate representative stress symptoms, including wilting and necrosis.

The seed germination bioassay with aqueous soil extracts yielded a contrasting result: the extract from fertilized soil (1.00 g·mL−1) resulted in a significantly higher germination rate (by ~17.5%) for P. betulifolia seeds compared with the extract from unfertilized soil (Table S3), suggesting that the net effect of the complex soil solution on germination was not inhibitory under these test conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Physicochemical Characteristics Under Long-Term Fertilization

In this study, a systematic assessment of a 30-year NPK fertilization regime in a “Dangshansuli” pear orchard revealed distinct alterations in soil chemistry. The most pronounced changes occurred in the surface soil (0–20 cm), which exhibited significant acidification alongside an increase in organic matter. This paradoxical co-occurrence—often reported in productive perennial systems—is likely driven by enhanced root-derived carbon inputs counterbalanced by protons released during nitrification of applied ammonium-based fertilizers [23,32,33]. A similar SOM accumulation under mineral fertilization has been reported in apple orchards in the United States [34]. Crucially, we found that the fertilization effect was not uniform with depth. Macroelement nutrients (total N, available N and P) accumulated primarily in the top 40 cm, directly reflecting the placement of fertilizers. In contrast, the dynamics of the base cations revealed a leaching and displacement process: exchangeable K+ increased in the upper 60 cm, while Ca2+ and Mg2+ were depleted in the surface layer but enriched in deeper strata (60–100 cm). This pattern underscores a long-term ion-exchange sequence where applied K+ and H+ displace Ca2+ and Mg2+ from soil colloids, facilitating their downward migration [23,35]. The unfertilized control profile remained relatively homogeneous, confirming that the observed stratification is a direct artifact of the fertilization regime. This acidification pathway is widely recognized in intensively fertilized orchards worldwide. Over-application of inorganic fertilizers is a major driver of soil acidification, a concern increasingly reported across fruit-growing regions in Asia and Europe [36,37]. In response, studies have shown that organic amendments—such as organic fertilizer, bioorganic fertilizer, and humic acid—can mitigate acidification, enhance microbial activity, and improve crop yield, offering a sustainable strategy for maintaining soil health in perennial fruit systems [38,39].

4.2. Influence of Soil Trace Elements Under Long-Term Fertilization

The availability of trace and heavy metals showed divergent responses to fertilization across the soil profile. Elements such as available B, Cu, and Zn were significantly concentrated in the fertilized topsoil (0–40 cm). While a lower pH in these layers can enhance the solubility of many metals, attributing these changes solely to acidification requires caution without explicit correlation analysis [40]. The elevated available Cu, exceeding optimum levels for plant growth by more than twofold, is likely a combined result of increased solubility and historical use of copper-based fungicides, a common practice in orchards [23,41]. A critical agronomic finding was the deficiency of plant-available Fe within the root zone (20–40 cm), despite adequate total Fe. This suggests that long-term fertilization induced a physiological iron deficiency, explaining the leaf chlorosis that was observed and highlighting a severe nutrient imbalance.

4.3. Soil Heavy Metals Under Long-Term Fertilization

Concurrently, certain heavy metals (Cu, Hg, As) (0–40 cm) accumulated in the surface layers, although all concentrations remained within national safety limits. This indicates a chronic, low-level input likely derived from fertilizer impurities rather than acute contamination [14,32]. This gradual accumulation likely originates from trace impurities in mineral fertilizers and atmospheric deposition over decades. Short-term applications of organic amendments such as pig manure compost have been reported to improve soil fertility without sharply increasing metal loads [8,14,42]; however, our long-term data demonstrate cumulative effects. Compared with other orchard soils where the application of chicken and swine manure results in limited metal accumulation [43], our data establish a clear baseline for metal accumulation under pure mineral fertilization. Integrating high-quality, composted organic amendments could be a strategy to mitigate further metal loading while improving soil structure and buffering capacity [38,39], but the source and metal content of such amendments must be vetted carefully.

4.4. Influence of Soil Chemical Compounds Composition Under Long-Term Fertilization

Beyond nutrients and metals, long-term fertilization altered the soil’s organic chemical composition. The greater diversity and abundance of compounds (e.g., alkanes like octadecane and organic acids like benzoic acid) in the fertilized 0–60 cm soil point to fertilizer-derived inputs or shifts in microbial metabolism. Among these, octadecane and benzoic acid are established allelochemicals known to inhibit the growth of various plants and algae at elevated concentrations [44,45,46]. The allelopathic bioassay demonstrated that octadecane could inhibit pear seedling growth at various concentrations (0.18 mmol·L−1). The practical implication of this finding is twofold: Firstly, it identifies a specific compound whose accumulation should be monitored; second, and more importantly, it suggests that the chronic input of mineral fertilizers can subtly shift the soil’s biochemical environment, potentially contributing to replant problems over time. However, the effect on established trees is complex, as indicated by the stimulatory effect of the whole soil extract on seed germination. This finding is particularly significant, as it suggests that long-term fertilization may not only modify nutrient and heavy metal profiles but also introduce or promote the accumulation of specific bioactive compounds that could inhibit plant growth, a phenomenon that has been reported in fruit crop orchards [18]. The global relevance of this mechanism warrants further cross-regional investigation.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the 30-year impact of mineral fertilization in a “Dangshansuli” pear orchard, revealing three major findings: (1) significant topsoil acidification and nutrient stratification, with N and P enriched in the upper 40 cm, but base cations (Ca, Mg) depleted at the surface; (2) the increased availability of trace/heavy metals (e.g., Cu, Zn) alongside a critical deficiency in plant-available Fe; and (3) an altered soil organic profile, including the accumulation of allelopathic compounds such as octadecane. Based on these findings, we recommend a targeted shift in the fertilization strategy for “Dangshansuli” pear orchards on similar sandy soils: significantly reduce the application rates of conventional NPK fertilizers, particularly nitrogen, to halt progressive acidification; incorporate high-quality, well-composted organic amendments to increase SOM, buffer pH, improve cation exchange capacity, and monitor heavy metal content; and apply chelated iron fertilizers to correct Fe deficiency. This integrated approach, moving away from sole mineral reliance, is essential to reverse degradation trends, rebalance nutrient profiles, and ensure the long-term productivity and sustainability of these valuable orchard systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12020162/s1, Table S1: Compounds numbers in each soil layer with long-term fertilization; Table S2: Compounds concentration in each soil layer with long-term fertilization; Table S3: Germination of Pyrus betulifolia Bunge seeds after different treatments.

Author Contributions

Material preparation, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing were performed by L.X., Q.Z. Data analysis and chart generation were performed by H.Z., W.S., G.G., Y.W., B.J. designed the methodology and conducted the critical review. X.T. performed the critical review, commentary, and revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-28-14).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Profiles of compound content across different soil depths were provided in the original data of GC-MS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT Database. 2016. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Zhu, Z.L.; Chen, D.L. Nitrogen fertilizer use in China—Contributions to food production, impacts on the environment and best management strategies. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2002, 63, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.X.; Jiang, H.B.; Zhao, J.W.; Xu, Y.C. Current fertilization in pear orchards in China. Soils 2012, 44, 754–761. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Wolf, J.; Zhang, F.S. Towards sustainable intensification of apple production in China—Yield gaps and nutrient use efficiency in apple farming systems. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.L.; Patel, N.; Rani, L.; Kumar, P.; Dutt, I.; Maddodi, B.; Chaudhary, V.K. Sustainable options for fertilizer management in agriculture to prevent water contamination: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 8303–8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.C.; Gao, P.D.; Wang, B.Q.; Lin, W.P.; Jiang, N.H.; Cai, K.Z. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic amendments supplementation on soil nutrient, enzyme activity and heavy metal content. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Peng, X. Long-term fertilization increases heavy metals accumulation in topsoil but not in deeper layers of red soil sloping farmland. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 396, 128171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrzejewska, A.; Biber, M. The effect of long-term soil system use and diversified fertilization on the sustainability of the soil fertility—Organic matter and selected trace elements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yu, C.; Mou, S. Sustainable livestock and poultry manure management considering carbon trading. Energy 2025, 326, 136267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boora, R.S. Effect of inorganic fertilizers, organic manure and their time of application on fruit yield and quality in mango (Mangifera indica) cv. Dushehari. Agric. Sci. Digest 2016, 36, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Ye, J.; Lin, H.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Ma, J. Dynamic characteristics of heavy metal accumulation in agricultural soils after continuous organic fertilizer application: Field-scale monitoring. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of organic manure on wheat yield and accumulation of heavy metals in a soil—Wheat system. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H.; Jia, L.; Huang, C.; Qiao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Wan, Y. Long-term effect of intensive application of manure on heavy metal pollution risk in protected-field vegetable production. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Effects of long-term fertilizer applications on peanut yield and quality and plant and soil heavy metal accumulation. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Li, K.; Diao, T.T.; Sun, Y.B.; Sun, T.; Wang, C. Influence of continuous fertilization on heavy metals accumulation and microorganism communities in greenhouse soils under 22 years of long-term manure organic fertilizer experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 959, 178294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shah, A.; Arafat, Y.; Arif Hussain Rizvi, S.; Shao, H. Plant allelopath-y in response to biotic and abiotic factors. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.H.; Xuan, T.D.; Khanh, T.D.; Tran, H.D.; Trung, N.T. Allelochemicals and signaling chemicals in plants. Molecules 2019, 24, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Chander, S.; Ram, K.; Sajana, S. Allelopathy and its effect on fruit crop—A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, K. Allelopathic effects of high contents of phenols and flavonoids in Musa paradisiaca L. cultivars on banana borer Odoiporus longicollis (Olivier). Allelopath. J. 2019, 49, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y. The Pear Industry and research in China. Acta Hortic. 2011, 909, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.D.; Jia, B.; Liu, P.; Ye, Z.F.; Zhu, L.W. Differentially expressed genes related to the formation of russet fruit skin in a mutant of ‘Dangshansuli’ pear (Pyrus bretchnederi Rehd.) determined by suppression subtractive hybridization. Euphytica 2013, 196, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, B.; Baoyin, B.; Cui, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Cui, J. Effects of long-term application of nitrogen fertilizer on soil acidification and biological properties in China: A Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Long-term impact of fertilization on soil pH and fertility in an apple production system. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 18, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghege, C.; Bineng, C.; Messiga, A. Effects of long-term nitrogen fertilization and application methods on fruit yield, plant nutrition, and soil chemical properties in highbush blueberries. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.X.; Sun, C.Y.; Sun, L.Q.; Bao, X.M.; Hong, X.P. Aggregate composition and organic carbon distribution in long-term pear planting soil. Soils 2022, 54, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An Examination of the degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, E.F.; Augusto, A.S.; Pereira-Filho, E.R. Determination of Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Ni and Pb in cosmetic samples using a simple method for sample preparation. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Gui, H.R.; Chen, S.; Peng, W.H.; Liu, X.H.; Zhou, G.; Wen, W.L.; et al. Determination and application of soil heavy metal geochemical baseline in the southern region of Wushan County in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.F. Analytical Method Development for Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Calcareous Desert Soil. Master’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.Y.; Ge, Z.Q.; Gao, F.M.; Ao, M.; Guan, Y.X. Comprehensive evaluation of maize germplasm for alkali tolerance during germination. Front. Plant Sci. 2026, 16, 1728607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.W.; Xi, H.Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.W.; Jiang, T.P.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liang, L.L.; Liu, Y.X. Autotoxic effects and underlying mechanisms of exogenous benzoic acid on nicotiana tobacco. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 31, 2096–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shu, A.; Song, W.; Shi, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, S.; et al. Long-term organic fertilizer substitution increases rice yield by imp-roving soil properties and regulating soil bacteria. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Mou, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, J.; Heděnec, P.; Xu, Z.; Tan, B.; Cui, X.; et al. Fertilization effects on soil organic matter chemistry. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, T.; Milošević, N.; Mladenović, J. The influence of organic, organo-mineral and mineral fertilizers on tree growth, yielding, fruit quality and leaf nutrient composition of apple cv. ‘Golden Delicious Reinders’. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 297, 110978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tu, X.; Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Ni, K.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chang, S. Effects of ammonium-based nitrogen addition on soil nitrification and nitrogen gas emissions depend on fertilizer-induced changes in pH in a tea plantation soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zeng, S.; Jiang, S.; Xie, C.; Wang, Z.; Dong, C.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q. Mitigation of soil acidification in orchards: A case study to alleviate early defoliation in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) trees. Rhizosphere 2021, 20, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, K.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Tao, J.; Fan, L.; Raza, S.; Guggenberger, G.; Ku-zyakov, Y. Acidification of European croplands by nitrogen fertilization: Consequences for carbonate losses, and soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hu, X.; Kang, Y.; Xie, C.; An, X.; Dong, C.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in the rhizospheric soil of litchi and mango orchards as affected by geographic distance, soil properties and manure input. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 152, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzade, A.; Babaeian, M. Investigating the effects of humic acid and acetic acid foliar application on yield and leaves nutrient content of grape (Vitis vinifera). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 6049–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradl, H.B. Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soils constituents. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2004, 277, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Pandita, S.; Singh Sidhu, G.; Sharma, A.; Khanna, K.; Kaur, P.; Bali, A.; Setia, R. Copper bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants: A comprehensive review. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.J.; Zhang, L.F.; Liu, Z.B.; Zhang, W.X.; Lan, X.J.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.R.; Li, Z.Z.; Wang, P. Effects of long-term application of chemical fertilizers and organic fertilizers on heavy metals and their availability in reddish paddy soil. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2021, 42, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Su, D.; Qiao, Y.; Li, H. Accumulation and bioavaila-bility of heavy metals in an acid soil and their uptake by paddy rice under continuous application of chicken and swine manure. J. Hazard. Mat. 2020, 384, 121293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q.; Miao, Y.; Peng, Z.; Huang, B.; Guo, L.; Liu, D.; Du, H. Allelopathic effect of Artemisia argyi on the germination and growth of various weeds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Takeshita, S.; Kimura, F.; Ohno, O.; Suenaga, K. A novel substance with allelopathic activity in Ginkgo biloba. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, H.; Prajapati, S.K. Allelopathic effect of benzoic acid (hydroponics root exudate) on microalgae growth. Environ. Res. 2022, 219, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.