Abstract

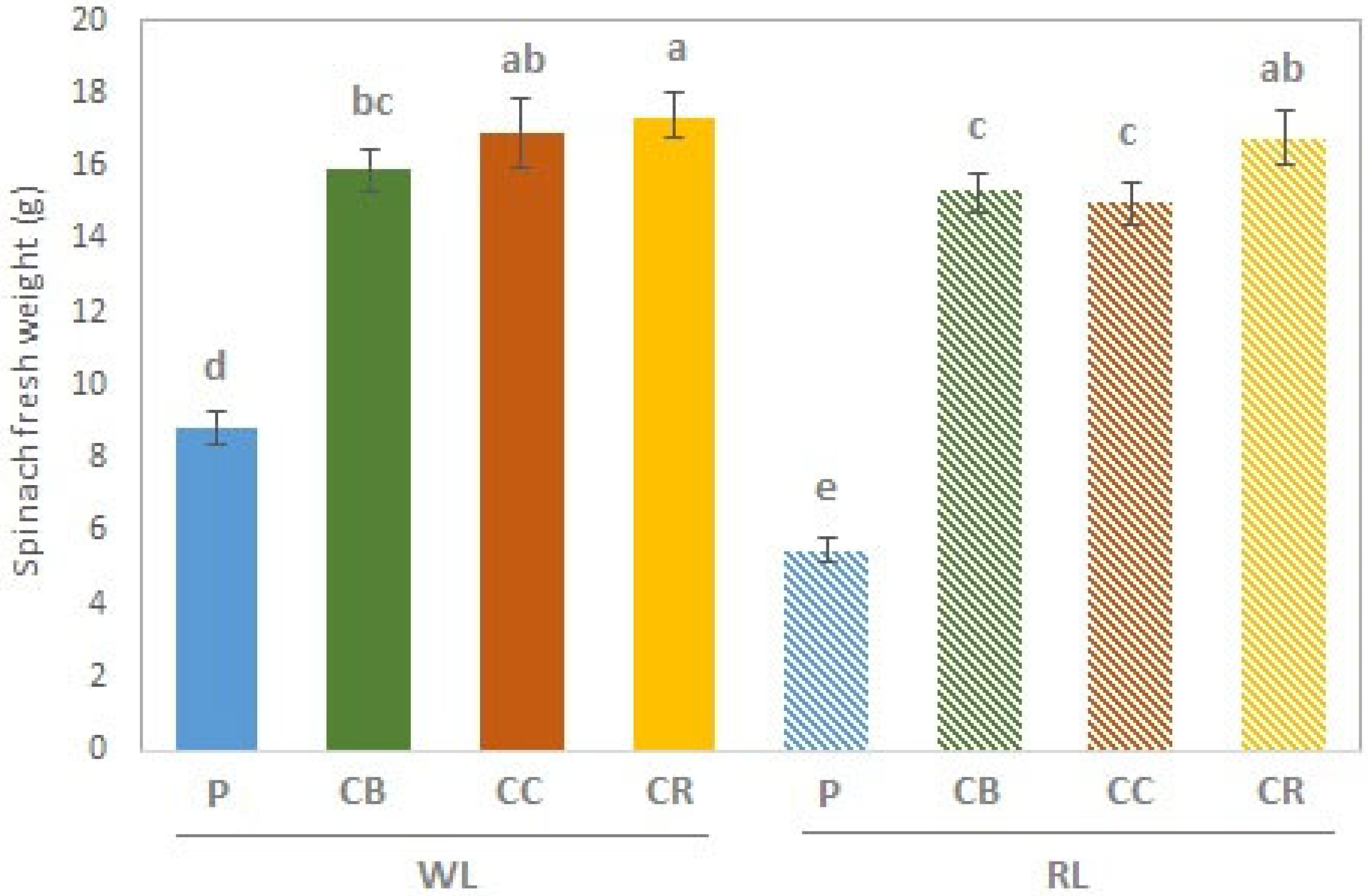

Background: Spinach has a high content of nutrients, proteins, carbohydrates, and vitamins beneficial for human health, that are closely associated with the type of crop, the growing media, the temperature, and lights used for growing. Methods: Two types of light were used: white light (WL) and red light (RL), and also three different growing media: compost without additives (CB), compost with coffee additive (CC), and compost with rockrose additive (CR). Results: Spinach grown under WL, regardless of the treatment, showed greater plant growth than that grown under RL_P. Furthermore, treatments WL_CC and WL_CR increased by 90% and 95%, respectively, compared to WL_P; similarly, treatments WL_CB, WL_CC, and WL_CR increased by 179%, 174%, and 205%, respectively, compared to the RL_P control. The protein content of spinach leaves from growing media WL_CB and WL_CC increased by 50 and 46% respectively compared to WL_P; similarly, growing media RL_CB and RL_CC increased by 82 and 57% respectively compared to RL_P. This contrasted with the carbohydrate content, which was higher in spinach grown under WL_P and RL_P. Spinach grown under WL_P and RL_P showed significantly more free sugars. On the other hand, spinach grown under WL had a higher concentration of organic acids than that grown under RL, regardless of the growing media used. The content of fatty acids, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activities did not follow a clear pattern with respect to the type of light and growing media. Conclusions: Overall, compost-based substrates combined with white LED light enhanced spinach growth and nutritional quality through a synergistic effect. However, compost reduced phenolic compounds, while red LED light increased phenolic content and antioxidant activity, indicating contrasting effects on spinach quality.

1. Introduction

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is one of the most important leafy vegetables worldwide, both in terms of production volume and consumption. Several varieties are sold on the market, including baby spinach, teen spinach, and vine spinach [1,2,3,4]. This widespread acceptance is due to its high nutritional value, as it constitutes an important source of proteins, minerals, carbohydrates, and vitamins beneficial to human health [1,5]. Baby spinach shows tiny and tender leaves compare to other spinach leaves varieties and its production cycles are faster than in other varieties [5].

Baby spinach can grow on soil or in growing media [6]. The main growing media is peat, however, the extraction of this resource generates adverse effects on the ecosystem [7] so alternative growing media are necessary to replace partially or totally the use of peat. Composts from the agri-food industry can be a good raw material for compost after a protocolized composting process [8]. These materials not only provide a safe and environmentally sustainable source for compost production, but can also confer additional functional properties, such as biostimulant, biofertilizer, and biopesticide activity [9]. In addition, the addition of organic, biological, or mineral amendments during the final stage of composting can enhance the compost’s agronomic properties [3,10,11,12]. Different mixes of compost/peat have assayed with good results. For example, De Corato et al. [13] found that compost from agro-energy co-products and residues were capable to induce suppression towards seven pathosystems. Hernández-Lara et al. [9] observed and increased crop productivity when using a compost/peat (75/25; w/w) on baby red lettuce, and Nájera et al. [14] observed higher production of microgreens (Mizuna and Pak choi) using compost/peat (50/50 and 75/25; w/w).

Cultivation using light emitting diode (LED) lighting environmentally controlled rooms enables stable vegetable production regardless of the weather conditions [15,16]. Therefore, high productivity or superior vegetable quality can be attained even under suboptimal light intensity conditions. The choice of light source plays a critical role in determining both the yield and quality of the vegetable crop, as light characteristics directly influence plant development [17]. Plant growth is affected not only by light intensity but also by the spectral composition of the light, which regulates key physiological processes [18]. Several studies have reported significant variations in the growth and development of spinach plants as a function of the applied light treatment [18].

Narrow-spectrum lighting specifically designed for crop cultivation enables targeted regulation of plant physiological processes such as leaf expansion and photosynthesis [19]. Red light (600–700 nm) is regarded as the most efficient wavelength range for driving photosynthesis [20]. However, exposure to red light alone has been shown to limit both plant growth and photosynthetic capacity [21]. Adding blue light (400–500 nm) is essential for proper functioning of photosynthesis [22] and plays a role in several key physiological processes, such as light-mediated chloroplast movement and the regulation of stomatal aperture [23]. Far-red light (700–800 nm) is involved in phytochrome-mediated phenotypic adaptation [24].

The metabolism of the plants and, consequently, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites are also affected by the edaphoclimatic conditions, such as the photoperiod, the type of light, the fertility of the soil, the growing media, the temperature, and agricultural practices [25,26]. Light has been studied to influence the biosynthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites, as photoreceptor signalling pathways cause genetic changes when activated by light photons [27]. For example, Esteban et al. [28] or Figueroa et al. [29] obtained a higher content of secondary metabolites (carotenoids) at a photosynthetic photon flux of 600 µmol m−2 s−1. However, no studies have systematically evaluated the interactive effects of different compost additives and LED light spectra on the accumulation of secondary metabolites in spinach. This study is the first to integrate varying proportions of raw compost materials and specific additives (e.g., coffee and rockrose residues) with controlled LED light spectra (WL and RL) to use as a growing media (compost/peat; 50/50) to increase the yield and quality of baby spinach (Spinacia oleracea L, variety Sunangel, RZ) and to find the best growing media–LED light spectra combination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lighting Conditions

Two types of LEDs were used: Xitanium LED (Phillips®, Koninklijke Philips N.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands), Blue: 18%, Green: 44.82%, Red: 34.36%, and FR: 2.83% (White light, WL) and Arize® Top Horticulture LED Grow Lights (GE Current®, Tianjin, China), Blue 24.4%, Green: 0%, Red: 74.45%, and FR: 1.43%, (Red light, RL). Both LEDs showed a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 260 μmol m−2 d−1 and daily light integral (DLI) of 13.1 mol m−2 d−1.

2.2. Material

Compost was composed of 47% vineyard waste, 34% tomato waste, and 19% leek waste (CB); 47% vineyard waste, 34% tomato waste, and 19% leek waste and 20% coffee waste as additive (CC); 47% vineyard waste, 34% tomato waste, and 19% leek waste and 19% rockrose as an additive (CR). Compost characteristics and the composting process were previously described by [9]. Peat 315 (Blond/black 60/40, Turbas and Coco Mar Menor S.L.) as a control and mixed with composts at a rate 50/50 (compost/peat) (w:w) were used in the experimental design. The main physico-chemical and chemical characteristics of peat were pH 5.6, EC 1 mS cm−1, TOC 466.8 g kg−1, total N 9.4 g kg−1, total P 0.3 g kg−1, and total K 0.9 g kg−1.

2.3. Experimental Design

The experiment was carried out at CEBAS-CSIC, (Murcia, Spain) in a germination chamber at 18 ± 1 °C in the dark with a relative humidity of 80% for 72 hours and afterwards in growth chamber at 25 °C–18 °C (day/night) and 60–70% relative humidity. For each LED (WL and RL), 48 pots of 250 ml food-grade polystyrene weighted (12 replicates/treatment) with 6 seed of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L., variety Sunangel, RZ) and 70 g of compost/peat mixture according to the different compost assayed CB, CC, CR, and only peat (P) for the control.

Three lamps of each LED (WR and RL) were placed above the crop canopy, with a separation of 50 cm between the lamp and the crop, and the plants were exposed to a photoperiod of 14/10 h (day/night). Inorganic NPK fertilizer (15-15-15) (compound NPK fertilizer-Fertiberia) was used as fertilizer. Spinach plants were collected 29 days after planting and the aerial part was weighed to obtain fresh biomass. Subsequently, the plant was stored at −80 °C for further analysis and freeze-dried. The 12 replicates per treatment were homogenized to obtain a representative sample for each treatment. From this representative sample, 3 independent measurements were performed.

2.4. Proximal and Energetic Measurements

The proximal and energetic values of spinach were carried out according to the procedures described by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) (AOAC, 2016). Crude protein content (N × 6.25) was quantified by the macro-Kjeldahl method using an automatic distillation and titration unit (model Pro-Nitro-A, JP Selecta, Barcelona, Spain); the crude fat content was estimated using a Soxhlet apparatus (Behr Labor Technik, Dussedolf, Germany) by extraction with petroleum ether; and the ash content was evaluated by incinerating the samples at 550 ± 15 °C. The total carbohydrate content was evaluated by the difference based on the following equation: total carbohydrates: 100 − (g fat + g ash + g protein). The energy value (kcal/100 g of dw) was calculated according to the Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 (2011) as follows: 4 × (g protein + g carbohydrates) + 9 × (g fat).

2.5. Hydrophilic Compounds

2.5.1. Free Sugars Profile

Free sugars were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to a refractive index (RI) detector, following a previously described methodology [30]. Spinach leaf samples were extracted with 80% ethanol (40 mL) in a water bath at 80 °C for 30 min, using melezitose (5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as an internal standard. After centrifugation, the supernatants were filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure at 60 °C. Defatting was performed by liquid–liquid extraction with ethyl ether (10 mL, three times). The aqueous phase was then centrifuged, concentrated at 40 °C, reconstituted in distilled water to a final volume of 5 mL, and filtered through 0.2 µm nylon filters (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) prior to injection into the HPLC system. Free sugars were identified by comparison of retention times with those of authentic standards, and quantification was carried out using the internal standard method with calibration curves constructed from standard solutions. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Clarity 2.4 software (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic).

2.5.2. Organic Acids Profile

The organic acids profile was determined following a previously described method [31]. Briefly, spinach leaf samples (2 g) were extracted with 25 mL of metaphosphoric acid at 25 °C and centrifuged at 150 rpm for 45 min. The resulting extracts were filtered through Whatman No. 4 paper and subsequently through 0.2 µm nylon filters prior to analysis. Chromatographic analysis was performed using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled with a diode array detector (UHPLC–DAD; Shimadzu 20A series, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), with UV–Vis detection. Compounds were monitored using a photodiode array detector at a preferential wavelength of 280 nm. Organic acids were identified by comparing retention times and UV spectra with those of authentic standards, while quantification was carried out using external calibration curves constructed from standard compounds based on peak area measurements.

2.6. Lipophilic Compounds

2.6.1. Fatty Acid Profile

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were obtained by transesterification of the lipid fraction previously extracted by Soxhlet. Methylation was carried out using a methanol/sulfuric acid/toluene mixture (2:1:1, v/v/v; 5 mL) in a water bath at 50 °C for 12 h under constant agitation (160 rpm). After the reaction, deionized water (3 mL) and diethyl ether (3 mL) were added to promote phase separation, allowing recovery of the FAME-containing organic phase, as previously described [32]. The analysis was performed using a gas chromatography system (Chromass 6500, YL Instruments, Anyang, Republic of Korea) equipped with a split/splitless injector, a flame ionization detector (FID), and a Zebron-FAME capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.20 µm film thickness; Phenomenex, Lisbon, Portugal). The chromatographic conditions and temperature program were applied according to previously published procedures [30]. The identification and quantification were determined by comparing the relative retention times of the FAME peaks of the samples with commercial standards (FAMEs, reference standard mixture 37, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The results were processed using CSW 4.0 Software (Informer Technologies, Inc., Solihull, UK).

2.6.2. Tocopherols Profile

Tocopherols were quantified according to a previously established method [30]. Spinach samples were supplemented with butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT; 10 mg/mL; 100 µL) and an internal standard solution (tocol; 50 µg/mL; 400 µL), both prepared in hexane. Extraction was performed by sequential addition of methanol (4 mL), hexane (4 mL), and a saturated aqueous NaCl solution (2 mL). The mixture was centrifuged, and the upper hexane layer containing tocopherols was collected into light-protected vials. This extraction step was repeated twice using hexane, and the combined organic phases were evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream. The dried extracts were reconstituted in n-hexane (2 mL), passed through an anhydrous sodium sulfate micro-column, and filtered through 0.2 µm nylon filters (Whatman) into dark injection vials. Tocopherol analysis was carried out using a high-performance liquid chromatography system equipped with a fluorescence detector (FP-2020; Jasco, Tokyo, Japan), set at an excitation wavelength of 290 nm and an emission wavelength of 330 nm. Identification was achieved by comparison of retention times with those of authentic standards, and quantification was performed using the internal standard method based on fluorescence response, with calibration curves constructed from commercial standards.

2.7. Phenolic Compounds Profile

In total, 1.5 g of spinach leave powder was extracted with vigorous shaking (150 rpm) with a hydroethanolic mixture (EtOH/H2O, 80:20). The extracts were filtered through 0.22 μm disposable filter disks. The combined extracts were concentrated under reduced pressure with a 40 °C water bath (Büchi R-210 rotary evaporator, Flawil, Switzerland). The aqueous phase was frozen and lyophilized (FreeZone 4.5, Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) for further analysis.

Lyophilized spinach extracts were reconstituted in an ethanol/water mixture (80:20, v/v) to obtain solutions at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and subsequently filtered through 0.22 µm membranes. Phenolic compounds were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode array detection and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS), following a previously described methodology [33]. Compound identification was tentatively assigned based on retention times, UV–Vis absorption characteristics, and mass spectral data in comparison with authentic standards and published literature. Quantification was carried out using peak area measurements and calibration curves constructed with commercially available standards of structurally related compounds, namely chlorogenic acid. Final identification was supported by chromatographic behavior, elution sequence, UV–Vis spectra, and fragmentation patterns, in agreement with data reported in previous studies [34,35,36,37,38].

2.8. Antioxidant Activity Evaluation

2.8.1. Assessment of the Capacity to Inhibit the Formation of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS)

The hydroethanolic extracts prepared above to analyse the profile of phenolic compounds were re-dissolved in water and subjected to dilutions from 10 to 0.1562 mg/mL. The lipid peroxidation inhibition in porcine brain cell homogenates was evaluated by the decrease in TBARS; the colour intensity of malondialdehyde– thiobarbituric acid (MDA–TBA) was measured at 532 nm. The inhibition percentage (%) was calculated using the following equation: [(A − B)/A] × 100, where A and B represent the absorbance of the control and the sample extract [30]. Antioxidant activity was expressed as EC50 values, defined as the concentration of sample (mg/mL) required to achieve 50% inhibition. Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was employed as a positive control.

2.8.2. Assessment of the Capacity to Inhibit Oxidative Haemolysis (OxHLIA)

The antihaemolytic activity of the hydroethanolic extracts, reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), was assessed using the oxidative haemolysis inhibition assay (OxHLIA) with erythrocytes isolated from healthy sheep, following the procedure described by the authors [39]. A 2.8% (v/v) erythrocyte suspension (200 µL) was combined with 400 µL of either extract solutions (0.0938–3 mg/mL in PBS), PBS as control, or water for complete hemolysis. After pre-incubation at 37 °C for 10 min under gentle shaking, AAPH (2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride; 200 µL, 160 mM in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added. The optical density at 690 nm was recorded approximately every 10 min using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, ELX800, Santa Clara, CA, USA) until complete hemolysis occurred. IC50 values (mg/mL), defined as the extract concentration required to protect 50% of the erythrocytes from AAPH-induced hemolysis over a ∆t of 60 min, were calculated. Trolox was used as a positive control.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using IMB Statistics SPSS 27.0 software, and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed for the studied parameters. When significant differences were detected (α = 0.05), the treatments were compared using the Tukey’s HDS test.

3. Results

3.1. Spinach Yield

In general, treatment under WL showed higher yield than under RL (Figure S1). WL_P showed significant higher yield than RL_P (Figure S1). Treatments with compost showed significantly higher spinach fresh weight than peat independently of type of LED light (Figure 1). Between compost under both LEDs light, treatment WL_CR (17.33 g) followed by WL_CC (16.89 g) and RL_CR (16.79 g) showed significantly higher spinach fresh weight than the rest of the treatments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) fresh weight. Results are expressed mean ± SD (n = 3); WL—white light; RL—red light; P—peat (control); CB—compost without additive; CC—compost with coffee additive; CR—compost with rockrose additive; Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between samples were assessed by a one-way ANOVA, and compared by Tukey’s test (HSD) when significant differences were detected, and are indicated by different letters.

3.2. Proximate Composition of Spinach Leaves

The nutritional composition of spinach is shown in Table 1. The fat content in peat treatments did not show differences between the types of LEDs. The highest values in compost treatments were RL_(CB–CC) and WL_(CB-CR). The proteins content of spinach leaves in peat was higher in WL_P than RL_P. Compost treatments independent of type of LED showed higher values than peat. Treatment RL_CB showed the highest values followed by WL_(CB-CC) (Table 1). The ash content in peat treatment did not show differences between lights. Compost treatments were significantly higher than peat independent of type of light; WL_CB showed the highest values. However, carbohydrates and energy content increased significantly in peat in both lights compared to composts. Treatment RL_CR for carbohydrates and RL_CC for energy showed the highest values. While carbohydrate RL_P was higher than WL_P, but for energy no differences were observed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proximate composition, free sugars, and tocopherols of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves.

3.3. Free Sugars of Spinach Leaves

Three soluble sugars were found in spinach leaves, glucose, sucrose, and raffinose (Table 1). Raffinose was only detected in compost treatments (Table 1), where treatment RL_(CC-CR) showed the highest values. No differences were observed in the content of glucose in peat treatment independent of type of light. In general, the content of glucose in compost treatments was lower than in peat independent of type of light, except WL_CB that showed the highest values (Table 1). The content of sucrose was higher in RL than in WL. Peat treatments showed higher content than compost. WL_CR showed the highest values of compost treatment. Raffinose content in RL_(CC–CR) showed the highest values (Table 1).

The content of α-tocopherol was higher than γ-tocopherols. Both tocopherols showed higher content for peat under RL than WL lights for peat and compost treatments. RL_CR showed the highest values (Table 1).

3.4. Organic Acids of Spinach Leaves

The main organic acids detected in spinach were oxalic, malic, shikinic, ascorbic, citric, and traces of fumaric acid (Table 2). The oxalic, malic, and citric acids were observed in higher content than the others organic acids, and the WL_P showed higher values than RL_P. The content of oxalic and malic acids in compost treatment was in general, higher than peat except in RL that were similar. The content of citric acid in compost treatment were in general, lower than in peat independently of light, except for WL_CB and RL_CC that showed higher values compared to their respective peat treatments. Ascorbic acid was, in general higher, in WL_P and RL_P than the compost treatment independent of type of light except for WL_CB that showed the highest values. Total organic acids were significantly higher in WL_(CB-CC). WL_P treatments showed higher total acids than RL_P treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Organic acids of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves.

3.5. Fatty Acids of Spinach Leaves

The main fatty acids detected were C18:3n3 (α-linolenic 46.87–53.09%), C18:2n6c, (linoleic 16.59–21.85%), and C16:0 (palmitic acid 16.83–19.76%) (Table S1).

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) followed by saturated (SFA) were the most abundant classes of fatty acids in spinach leaves (Table 3). For PUFA, treatment WL_P showed higher content than RL_P and for compost treatments WL_CB and RL_CB-CR showed the highest values (Table 3). While for SFA, WL_P showed lower values than RL_P and the highest values were showed by RL_P and WL_CC.

Table 3.

Lipophilic composition (relative percentage %) of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves.

3.6. Phenolic Profile of Spinach Leaves

Twenty-five compounds were identified in all spinach leaves (Table S1). The profile of phenolic compounds is shown in Table S1. The presence of three phenolic acids (Ferulic acid derivative, ferulic acid hexoside, and p-coumaric acid corresponding to peaks 1, 2, and 8) and 22 flavonoids are shown (Table S1). Flavonoids found in spinach were derived from patuletin (six peaks), spinacetin (ten peaks), jadeidin (one peak), and isorhamnetin (one peak) (Table S1). In addition, three flavonoids (peaks 23, 24, and 25) were present as glucuronide conjugates (Table S3).

The content of flavonoids was higher than phenolic compounds (Table 4). Total flavonoids was higher in all treatments under RL than WL. RL_P and WL_P showed the highest values (Table 4). Total phenolic compounds were higher in peat under both lights RL and WL than composts. RL_P wassignificantly higher than WL_P (Table 4). Phenolic compounds content was higher in RL-P and WL_P, and compost treatment showed higher values than peat. WL_CB showed the highest values (Table 4).

Table 4.

Content (mg/g of extract) of phenolic compounds in spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves.

3.7. Antioxidant Activity in Spinach Leaves

The IC50 values of TBARS and OxHLIA activities for all spinach were considerably higher than those of the positive control (Trolox) showing less antioxidant activity (Table 5). RL_P showed higher TBARS and OxHLIA compared to WL_P indicating lower antioxidant activity with RL than with WL. Compost treatment under WL showed higher values than their respective peat treatment (WL_P), while, under RL, compost treatment showed lower values than RL_P (Table 5).

Table 5.

Antioxidant activity of the spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spinach Growth

Considering the benefit of spinach leaves in human health, the way to boost its production and healthy properties is under study. Composts as growing media in a mix of compost/peat (50/50), increase plant growth due to its organic matter, macronutrient content, and a slow release of nutrients [9,40,41]. In addition, compost CC and CR under WL showed the highest fresh weight, probably due to the incorporation of coffee and rockrose as additives that could have biostimulants, biofertilizers, growth promoting compounds, biotic agents, and many others components [9,42]. These components can synergistically act in affecting physiological and biochemical metabolism including uptake and transportation of water and mineral, enzyme activation, osmotic potential, photosynthesis, hormone balance, and antioxidant defenses [43]. Several studies suggest that coffee grounds and other organic waste as compost can modify the chemical composition of the substrate, including organic C and total N, which can influence plant nutrition and metabolism by releasing nutrients during processing [44].

The type of LED light also influences the crop yield [45,46]. The WL and RL activate photoreceptors (cryptochromes, phytochromes, and phototropins) that are closely related to the physiological and morphological responses of plants [47]. The best growth was under WL, possibly due to WL including almost the whole spectral range (360–730 nm), thus being more effective for photoreceptors [48]. While RL does not have a green wavelength, it does have a higher blue and red wavelength compared to WL. Vaštakaitė-Kairienė et al. [45] also reported the lowest spinach growth under conditions with the highest proportion of blue light (i.e., the lowest red-to-blue ratio), consistent with our findings. The role of blue light in modulating crop yield has been examined in various studies, although the results remain contradictory [49]. An increased proportion of blue light has been shown to inhibit both cell division and expansion, resulting in reduced leaf area [50]. This reduction in leaf surface limits photon capture, which is frequently the primary factor contributing to diminished plant growth [51]. Interestingly, the best growth showed for WL_CR could indicate a nice synergy between compost and LED light [45,49,50,51].

4.2. Nutritional Profile

Nitrogen is an essential component of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. When a plant absorbs more available nitrogen, it can reduce it to assimilable forms (e.g., NH4+) and use it to synthesize amino acids through metabolic pathways involving enzymes such as glutamine synthetase. This increases total protein synthesis in plant tissues. The agronomic literature directly links higher levels of absorbed and stored nitrogen with higher protein content in crops such as alfalfa or wheat under nitrogen applications (whether organic or synthetic) [52]. Adequate nitrogen availability is essential for spinach production, as it promotes vigorous growth and enhances the dark green pigmentation of the leaves, a key quality trait valued by consumers [53]. The agro-industry compost used for spinach growth increased the content of nitrogen and proteins in spinach due to the higher N content of these compost compared to peat and their availability for plants [9,54]. Adekiya et al. [55] observed similar results in okra with the incorporation of green manures in the soil. In addition, the WL_P showed higher protein content. It could mean that WL should be one of the important factors affecting the accumulation of protein in spinach.

Compost treatments independent of types of LEDs light showed lower carbohydrate content. Studies on source–sink dynamics in Arabidopsis thaliana during the vegetative phase have reported a progressive decline in carbohydrate levels, particularly during the night, associated with the absence of light and the depletion of starch reserves [56,57]. A decline in carbohydrate availability is known to induce the expression of the triose-phosphate translocator gene (TPT), which plays a key role in the photosynthetic system and in the redistribution of carbohydrate reserves—particularly starch—to mitigate energy shortages [58,59,60,61]. Plants tend to accumulate higher levels of carbohydrates when mild stress conditions inhibit growth to a greater extent than photosynthesis [62]. In spinach, based on results, leaves RL_P increase carbohydrates content compared to WL_P. RL showed higher percentage of blue light 24.4% and red 74% than WL. These results agree with Ajdanian et al. [63] that observed the highest amount of carbohydrate with the bluest light, and in cabbage, soybean, and rapeseed under high red light [64,65]. The results of our work indicate that compost increases the nutritional content of spinach as other authors observed [66,67] and that the interaction between compost and LED light is a synergic effect [68].

4.3. Free Sugars, Tocopherols Content, and Organic Acids

Sugars are key biochemical compounds with significant nutritional value, serving as the primary energy source in the human diet [69]. The concentration of soluble sugars in leafy vegetables such as spinach is receiving growing attention, particularly due to its relevance for individuals with diabetes, who must regulate their insulin dosage [57]. Sucrose was the highest compound followed by glucose and fructose observed in spinach leaves [57,61]. The raw materials from compost (tomato and leek wastes) showed lower values of sugars [70] that could indicate that this compost cannot increase sugar content compared to peat. However, several authors have showed high soluble sugars compared to our lower levels of sugar in spinach grown in compost. For example, Boutasknit et al. [71] showed a significant increase in total soluble sugars in garlic bulb grown with compost. Ekinci et al. [72] observed an increase in total soluble sugars in spinach plants grown in fish compost. Vahid Afagh et al. [41] found a higher content of total sugars in chamomile plants treated with spent mushroom compost, and Song et al. [73] also observed a reduction in soluble sugar content in lettuce leaves with increasing mineral nutrient concentration.

Our results showed higher total sugars under WL than RL contrary to Bantis et al. [74] who showed higher total sugar in spinach grown under red light (600–780 nm) compared to white light (500–599 nm). Also, a synergy was observed in WL_CR increased the sugar content compared to the other compost treatments.

The growing conditions and the genotype are key factors for tocopherol composition in leafy vegetables [72,75], mustard, parsley, and beet microgreens [76]. The only forms of vitamins detected were tocopherols α- and γ-, where α-tocopherol was higher than δ-tocopherol, and agrees with the findings of [77] who reported a similar profile of tocopherols for various spinach types. They also agree with [78,79], who found a higher amount of α-tocopherol than γ-tocopherols in spinach leaves. According to [38], the increase in α-tocopherol could indicate the important role in plant defense against aggressors that in this case could be due to the synergy of compost and RL. Also, similar results were observed by [80] who showed that the content of tocopherols in lettuce was higher in blue-red light than in white light.

Spinach contains various acids, including oxalic, malic, citric, and tartaric acids, with oxalic acid being the most abundant, as observed in our study. Oxalic acid consumption is considered safe when ingested in small amounts; however, consuming large quantities can lead to kidney stone formation in some individuals due to its binding with Ca2+ and Fe3+ ions and the formation of oxalate [61].

The increase in oxalic acid in spinach with compost treatment can be an indicative of an effective way to use compost as a source of nutrients for spinach, although it depends on several other factors such as species, cultivar traits, and nutrient management [1]. Bandian et al. [81] observed that the more fertilizers were applied to spinach, the greater the oxalic acid content they accumulated. The synthesis of oxalic acid is also linked to the reduction of nitrate to ammonium in leaf tissues, serving to counterbalance the alkalinity generated during this process [82].

A higher proportion of red light increased ascorbic acid levels and reduced nitrate (NO3−) and oxalic acid concentrations, in agreement with [80]. However, this contrasts with our results, as WL_P showed higher oxalic acid levels, and the combined effect of compost and WL also increased oxalic acid in spinach leaves. Some studies agree with our results. Proietti et al. [61], for instance, conducted a study on Eruca vesicaria (L.) Cav. where malic and citric acid tended to accumulate in plants grown in red-blue light and ascorbic acid was accumulated in plant grown in white light, similar to our results. Also, Gao et al. [83] observed that both oxalic and citric acid increased in green onion grown under white light.

4.4. Fatty Acid Composition

The widespread consumption of spinach worldwide may contribute significantly to the improvement of blood lipid profiles and the enhancement of the body’s defense mechanisms against chronic diseases [84]. Maeda et al. [85] documented the fatty acid profile of spinach leaves, highlighting their richness in polyunsaturated fatty acids and omega-3 (C18:3n3), despite its low lipid content. The fatty acid profile in green leafy vegetables is affected by light quality [84]. This effect was evident in our spinach. Spinach under WL had the least diversity of fatty acids compared to spinach grown in RL, except for the spinach grown in WL_CC. The green light spectrum increases the concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) [84]. However, the monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) of spinach did not show significant differences between the different growing media or light LED. The biosynthetic pathways through which this fatty acid is produced under specific light regimes remains to be clarified [86].

4.5. Phenolic Compounds

Variability in the concentration of phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, in vegetables can be attributed to multiple factors, including species-specific traits, geographic and environmental conditions, ultraviolet radiation exposure, nutrient availability, atmospheric pollutants, biotic stressors, cultivation techniques, harvest parameters, and post-harvest processing and storage methods [87,88]. Machado et al. [53] have shown that the biosynthesis of total phenols is stimulated by the low content of nitrogen in the soil or compost. This agrees with the low phenol content present in the spinach leaves in our study, probably due to the composts used showed a high nitrogen content [9]. A higher accumulation of flavonoids was also observed under organic fertilization relative to conventional practices [88].

Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites not indispensable for primary metabolism such as photosynthesis or dark respiration but play a key role in the adaptation of plants to habitats. Our composition of phenolic compounds agrees with the previous findings of other authors [34,35,36,37,38]. Phytochemical accumulation is influenced by cultivation techniques and environmental conditions [89], with environmental stresses inducing accumulation of phenolic compounds [90].

Herms et al. [91] showed the relationship between defense and plant growth, which may justify the higher content of flavonoids and phenolic compounds in spinach grown in peat compared to those grown in compost. It could be due to when the available nitrogen conditions are adequate or higher than necessary, plants focus on their growth, and not on the production of secondary metabolites that will help their subsequent defense due to lack of nutrients [43]. Regarding the effect of the type of light, light is one of the primary factors that affect plant growth, yield, and the accumulation of phenolics because among other functions, they protect cells against UV radiation and high light intensity, acting as sunscreens. Phenolic compound content was higher in spinach grown under RL than WL. The red light phytochrome receptor may play a role in the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds [92]. This may reflect the role of phytochrome in red light responses, since red light activates phytochromes that regulate plant growth; in turn, this activation could also engage photoreceptors involved in fruit development and chloroplast development, ultimately leading to an increase in chlorophyll [93,94]. This finding agrees with previous studies that demonstrated that far-red light (FR) (in our study the WL had a higher proportion of far-red), could induce the synthesis of phenolic compounds in spinach, since the content of secondary metabolites correlates with the activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), which is inactivated by far-red light, as in lettuce plants and several vegetables [90,95].

4.6. Antioxidant Activity

The greater antioxidant activity in spinach grown in RL compared to WL could be due to the fact that the expression of carotenoid-related genes (Lcyb, CrtZ, and Ccs) is better expressed in red light [96]. Refs. [97,98] observed that flavonoids and phenolic compounds are positively correlated with the antioxidant capacity of spinach. Antioxidant activity can be affected depending on the type of substrate used (soil, compost, hydroponic cultivation) in green leafy vegetables. Refs. [26,98] observed how Cichorium spinosum plants grown in soil showed greater antioxidant activity than plants grown with compost due to the increase in the content of phenolic compounds. Ref. [99] showed that in a water spinach culture, a high proportion of blue light had a positive effect on antioxidant activity, while red and white light showed the opposite. Despite this, it is possible that using light that includes all light waves influences the antioxidant activity of plants.

5. Conclusions

This study indicated that different mixtures of raw materials and additives in compost mixed with peat (50/50), and light LED type affected the growth, nutritional value, and chemical composition of spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Compost as growing media CC and CR and WL lighting LED (WL_CC_CR) boost the fresh weight of spinach by 90% and 95%, respectively, compared to the WL_P. In addition, compost treatments increase the nutritional profile of spinach and the interaction compost and LED light principally. WL was a synergic effect. In contrast, compost decreased the content of phenolic compounds of spinach due to the increase in nutrients available for the plant, producing a decrease of secondary metabolites. Only RL LED light effect increased the phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity.

Despite the relevance of the findings, this study has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. One limitation of this study is the limited number of light spectra and compost formulations evaluated, which could limit the generalizability of the results to other growing conditions. In addition, the relatively short experimental period may not fully capture the long-term effects on plant metabolic responses. Future studies should include a wider range of compost additives, spinach cultivars, light regimes, and growth stages to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12020165/s1, Table S1: Fatty acids (relative percentage %) of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves; Table S2: Chromatographic (retention time) and spectral (UV, MS, and MS/MS) data and suggested assignment of phenolic compounds in Spinach; Table S3: Content of phenolic compounds (mg g−1 extract) assigned of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves. Figure S1. Growing spinach in different composts and LED lights. The pot with the yellow label showed spinach grown in WL—white light, and the spinach with the red label shows spinach grown in RL—red light. (a) showed spinach grown in P—peat; (b) showed spinach grown in CB—compost without additive; (c) showed spinach grown in CC—compost with coffee additive; (d) showed spinach grown in CR—compost with rockrose additive.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N., Â.F., M.R., J.A.P., and L.B.; methodology, A.H.-L., D.A., C.P., and T.F.F.d.S.; software, C.N. and C.P.; validation, Â.F., M.R., J.A.P., and L.B.; formal analysis, A.H.-L., C.N., Â.F., and M.R.; investigation, A.H.-L., D.A., and C.N.; resources, A.H.-L., Â.F., and C.N.; data curation, A.H.-L., D.A., and T.F.F.d.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.-L., Â.F., and D.A.; writing—review and editing, C.N., Â.F., M.R., J.A.P., and L.B.; visualization, Â.F., C.N., and M.R.; supervision, Â.F. and M.R.; project administration, M.R., J.A.P., and L.B.; funding acquisition, M.R., J.A.P., and L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) for fi-nancial support from the FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC): CIMO, UID/00690/2025 (10.54499/UID/00690/2025) and UID/PRR/00690/2025 (10.54499/UID/PRR/00690/2025); and SusTEC, LA/P/0007/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0007/2020). The authors are also grateful to the national funding by FCT, through the institutional and individual scientific employment pro-gram-contract with L. Barros (CEEC-INST, DOI: 10.54499/CEECINST/00107/2021/CP2793/CT0002) and A. Fernandes (2023.11031.TENURE.014), respectively; and C. Pereira. This work has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and with European Regional Development Funds (ERDF, “Una manera de hacer Europa”) in the framework of the project “Compoleaf” (Compost as biofertilizer, resistance inductor against plant pathogens and healthy property promoter under a crop intensive sustainable production). Project (AGL2017-84085-C3-1-R, C3-2-R and C3-3-R) and grant (PRE2018-085802).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no know competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Giménez, A.; Gómez, P.A.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D.; Martínez-Sabater, E.; Ros, M.; Pascual, J.A.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Fernández, J.A. Effect of Compost Extract Addition to Different Types of Fertilizers on Quality at Harvest and Shelf Life of Spinach. Agronomy 2021, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaşka, M.; Kaymak, H.Ç. Unraveling the Impact of Seed Fatty Acid Profiles on Spinach Seed Germination under Temperature Stress. Turkish J. Agric. For. 2024, 48, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiyan, B.; Kour, J.; Nayik, G.A.; Anand, N.; Alam, M.S. Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). In Antioxidants in Vegetables and Nuts-Properties and Health Benefits; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, U.; TR, B. Dietary Phytonutrients in Common Green Leafy Vegetables and the Significant Role of Processing Techniques on Spinach: A Review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, M.; Hurtado-Navarro, M.; Giménez, A.; Fernández, J.A.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Lozano-Pastor, P.; Pascual, J.A. Spraying Agro-Industrial Compost Tea on Baby Spinach Crops: Evaluation of Yield, Plant Quality and Soil Health in Field Experiments. Agronomy 2020, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchena, F.B.; Pisa, C.; Mutetwa, M.; Govera, C.; Ngezimana, W. Effect of Spent Button Mushroom Substrate on Yield and Quality of Baby Spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Int. J. Agron. 2021, 2021, 6671647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, G.E.; Alexander, P.D.; Robinson, J.S.; Bragg, N.C. Achieving Environmentally Sustainable Growing Media for Soilless Plant Cultivation Systems—A Review. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 212, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.A.; Morales, A.B.; Ayuso, L.M.; Segura, P.; Ros, M. Characterisation of Sludge Produced by the Agri-Food Industry and Recycling Options for Its Agricultural Uses in a Typical Mediterranean Area, the Segura River Basin (Spain). Waste Manag. 2018, 82, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lara, A.; Ros, M.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Moral, R.; Andreu-Rodríguez, F.J.; Fernández, J.A.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Pascual, J.A. The Influence of Feedstocks and Additives in 23 Added-Value Composts as a Growing Media Component on Pythium irregulare Suppressivity. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthod, J.; Rumpel, C.; Dignac, M.-F. Composting with Additives to Improve Organic Amendments. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sánchez-García, M.; Vandecasteele, B.; D’Hose, T.; López, G.; Martínez-Gaitán, C.; Kuikman, P.J.; Sinicco, T.; Mondini, C. Agronomic Evaluation of Biochar, Compost and Biochar-Blended Compost across Different Cropping Systems: Perspective from the European Project FERTIPLUS. Agronomy 2019, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayara, T.; Basheer-Salimia, R.; Hawamde, F.; Sánchez, A. Recycling of Organic Wastes through Composting: Process Performance and Compost Application in Agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U.; Viola, E.; Arcieri, G.; Valerio, V.; Zimbardi, F. Use of Composted Agro-Energy Co-Products and Agricultural Residues against Soil-Borne Pathogens in Horticultural Soil-Less Systems. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera, C.; Ros, M.; Moreno, D.A.; Hernandez-Lara, A.; Pascual, J.A. Combined Effect of an Agro-Industrial Compost and Light Spectra Composition on Yield and Phytochemical Profile in Mizuna and Pak Choi Microgreens. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, D.C.J.; Ong, M.M.X.; Lee, Y.Y.; Teo, E.J.; Ong, Q.; Tanoto, H.; Xu, J.; Ong, K.S.; Suresh, V. Shaping and Tuning Lighting Conditions in Controlled Environment Agriculture: A Review. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellini, A.; Toscano, S.; Romano, D.; Ferrante, A. LED Lighting to Produce High-Quality Ornamental Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi-Kaneko, K.; Takase, M.; Kon, N.; Fujiwara, K.; Kurata, K. Effect of Light Quality on Growth and Vegetable Quality in Leaf Lettuce, Spinach and Komatsuna. Environ. Control Biol. 2007, 45, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisegna, F.; Burattini, B.; Mattoni, B. Lighting Design for Plant Growth and Human Comfort. In Proceedings of the 28th CIE Conference, Manchester, UK, 8 June–4 July 2015; pp. 1592–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, G.D.; Kim, H.-H.; Wheeler, R.M.; Mitchell, C.A. Plant Productivity in Response to LED Lighting. HortScience 2008, 43, 1951–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogewoning, S.W.; Wientjes, E.; Douwstra, P.; Trouwborst, G.; Van Ieperen, W.; Croce, R.; Harbinson, J. Photosynthetic Quantum Yield Dynamics: From Photosystems to Leaves. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1921–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorio, N.C.; Goins, G.D.; Kagie, H.R.; Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C. Improving Spinach, Radish, and Lettuce Growth under Red Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) with Blue Light Supplementation. HortScience 2001, 36, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogewoning, S.W.; Trouwborst, G.; Maljaars, H.; Poorter, H.; van Ieperen, W.; Harbinson, J. Blue Light Dose–Responses of Leaf Photosynthesis, Morphology, and Chemical Composition of Cucumis Sativus Grown under Different Combinations of Red and Blue Light. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3107–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaś, A.K.; Aggarwal, C.; Łabuz, J.; Sztatelman, O.; Gabryś, H. Blue Light Signalling in Chloroplast Movements. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1559–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, K.A.; Whitelam, G.C. Red: Far-red Ratio Perception and Shade Avoidance. In Annual Plant Reviews; Light Plant Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 30, pp. 211–234. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The Effect of Developmental and Environmental Factors on Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petropoulos, S.; Fernandes, Â.; Pereira, C.; Tzortzakis, N.; Vaz, J.; Soković, M.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactivities, Chemical Composition and Nutritional Value of Cynara cardunculus L. Seeds. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, F.; Somborn-Schulz, A.; Schlehuber, D.; Keuter, V.; Deerberg, G. Effects of Light on Secondary Metabolites in Selected Leafy Greens: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 495308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, R.; Fleta-Soriano, E.; Buezo, J.; Míguez, F.; Becerril, J.M.; García-Plazaola, J.I. Enhancement of Zeaxanthin in Two-Steps by Environmental Stress Induction in Rocket and Spinach. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Álvarez-Gómez, F.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Vega, J.; Massocato, T.F.; Gómez-Pinchetti, J.L.; Korbee, N. Interactive Effects of Solar Radiation and Inorganic Nutrients on Biofiltration, Biomass Production, Photosynthetic Activity and the Accumulation of Bioactive Compounds in Gracilaria cornea (Rhodophyta). Algal Res. 2022, 68, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spréa, R.M.; Fernandes, Â.; Calhelha, R.C.; Pereira, C.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Alves, M.J.; Canan, C.; Barros, L.; Amaral, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical and Bioactive Characterization of the Aromatic Plant Levisticum Officinale WDJ Koch: A Comprehensive Study. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Use of UFLC-PDA for the Analysis of Organic Acids in Thirty-Five Species of Food and Medicinal Plants. Food Anal. Methods 2013, 6, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obodai, M.; Mensah, D.L.N.; Fernandes, Â.; Kortei, N.K.; Dzomeku, M.; Teegarden, M.; Schwartz, S.J.; Barros, L.; Prempeh, J.; Takli, R.K. Chemical Characterization and Antioxidant Potential of Wild Ganoderma Species from Ghana. Molecules 2017, 22, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessada, S.M.F.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Coleostephus myconis (L.) Rchb. f.: An Underexploited and Highly Disseminated Species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 89, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritomi, M.; Komori, T.; Kawasaki, T. Flavonol Glycosides in Leaves of Spinacia Oleracea. Phytochemistry 1985, 25, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F.; Gil, M.I.; Castañer, M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Phenolic Metabolites in Red Pigmented Lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Changes with Minimal Processing and Cold Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 4249–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.H.; Hoskin, R.T.; Hayes, M.; Iorizzo, M.; Kay, C.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Lila, M.A. Spray-Dried and Freeze-Dried Protein-Spinach Particles; Effect of Drying Technique and Protein Type on the Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids, Chlorophylls, and Phenolics. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 133017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.; Charoenprasert, S.; Mitchell, A.E. Effect of Organic and Conventional Cropping Systems on Ascorbic Acid, Vitamin C, Flavonoids, Nitrate, and Oxalate in 27 Varieties of Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3144–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, J.M.; Park, J.; Ercius, P.; Kim, K.; Hellebusch, D.J.; Crommie, M.F.; Lee, J.Y.; Zettl, A.; Alivisatos, A.P. High-Resolution EM of Colloidal Nanocrystal Growth Using Graphene Liquid Cells. Science 2012, 336, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockowandt, L.; Pinela, J.; Roriz, C.L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Bredol, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical Features and Bioactivities of Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus L.) Capitula: The Blue Flowers and the Unexplored Non-Edible Part. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.B.; Ros, M.; Ayuso, L.M.; de Los Angeles Bustamante, M.; Moral, R.; Pascual, J.A. Agroindustrial Composts to Reduce the Use of Peat and Fungicides in the Cultivation of Muskmelon Seedlings. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahid Afagh, H.; Saadatmand, S.; Riahi, H.; Khavari-Nejad, R.A. Effects of Leached Spent Mushroom Compost (LSMC) on the Yield, Essential Oil Composition and Antioxidant Compounds of German Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.). J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, K.; Kono, M.; Fukunaga, T.; Iwai, K.; Sekine, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Iijima, M. Field Evaluation of Coffee Grounds Application for Crop Growth Enhancement, Weed Control, and Soil Improvement. Plant Prod. Sci. 2014, 17, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Mou, B. Responses of Spinach to Salinity and Nutrient Deficiency in Growth, Physiology, and Nutritional Value. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Z.; Yang, R. Spent Coffee Ground and Its Derivatives as Soil Amendments—Impact on Soil Health and Plant Production. Agronomy 2024, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V.; Brazaitytė, A.; Miliauskienė, J.; Runkle, E.S. Red to Blue Light Ratio and Iron Nutrition Influence Growth, Metabolic Response, and Mineral Nutrients of Spinach Grown Indoors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, L.; Vitale, E.; Guercia, G.; Turano, M.; Arena, C. Effects of Different Light Quality and Biofertilizers on Structural and Physiological Traits of Spinach Plants. Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, C.; Mattoni, B.; Bisegna, F. The Impact of Spectral Composition of White LEDs on Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) Growth and Development. Energies 2017, 10, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navvab, M. Daylighting aspects for plant growth in interior environments. Light Eng. 2009, 17, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Piovene, C.; Orsini, F.; Bosi, S.; Sanoubar, R.; Bregola, V.; Dinelli, G.; Gianquinto, G. Optimal Red: Blue Ratio in Led Lighting for Nutraceutical Indoor Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougher, T.A.O.; Bugbee, B. Long-Term Blue Light Effects on the Histology of Lettuce and Soybean Leaves and Stems. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 129, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, B. Economics of LED Lighting. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q. Effects of Combined Nitrogen and Phosphorus Application on Protein Fractions and Nonstructural Carbohydrate of Alfalfa. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1124664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Alves-Pereira, I.; Lourenço, D.; Ferreira, R.M.A. Effect of Organic Compost and Inorganic Nitrogen Fertigation on Spinach Growth, Phytochemical Accumulation and Antioxidant Activity. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldrin, A.; Andersen, J.K.; Møller, J.; Christensen, T.H.; Favoino, E. Composting and Compost Utilization: Accounting of Greenhouse Gases and Global Warming Contributions. Waste Manag. Res. 2009, 27, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekiya, A.O.; Ejue, W.S.; Olayanju, A.; Dunsin, O.; Aboyeji, C.M.; Aremu, C.; Adegbite, K.; Akinpelu, O. Different Organic Manure Sources and NPK Fertilizer on Soil Chemical Properties, Growth, Yield and Quality of Okra. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.; Mainson, D.; Porcheron, B.; Maurousset, L.; Lemoine, R.; Pourtau, N. Carbon Source–Sink Relationship in Arabidopsis thaliana: The Role of Sucrose Transporters. Planta 2018, 247, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-E.; Kuppusamy, S.; Cho, K.M.; Kim, P.J.; Kwack, Y.-B.; Lee, Y.B. Influence of Cold Stress on Contents of Soluble Sugars, Vitamin C and Free Amino Acids Including Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in Spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Food Chem. 2017, 215, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, D.; Kruse, A.; Flügge, U.-I.; Frommer, W.B.; Riesmeier, J.W.; Willmitzer, L.; Heldt, H.W. Effect of Antisense Repression of the Chloroplast Triose-Phosphate Translocator on Photosynthetic Metabolism in Transgenic Potato Plants. Planta 1994, 193, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic-Malinovska, R.; Kuzmanova, S.; Winkelhausen, E. Application of Ultrasound for Enhanced Extraction of Prebiotic Oligosaccharides from Selected Fruits and Vegetables. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 22, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.E. Carbohydrate-Modulated Gene Expression in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1996, 47, 509–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, S.; Moscatello, S.; Riccio, F.; Downey, P.; Battistelli, A. Continuous Lighting Promotes Plant Growth, Light Conversion Efficiency, and Nutritional Quality of Eruca vesicaria (L.) Cav. in Controlled Environment with Minor Effects Due to Light Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 730119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Thakur, J.K. Photosynthesis and Abiotic Stress in Plants. In Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ajdanian, L.; Babaei, M.; Aroiee, H. Investigation of Photosynthetic Effects, Carbohydrate and Starch Content in Cress (Lepidium sativum) under the Influence of Blue and Red Spectrum. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-H.; Huang, M.-Y.; Huang, W.-D.; Hsu, M.-H.; Yang, Z.-W.; Yang, C.-M. The Effects of Red, Blue, and White Light-Emitting Diodes on the Growth, Development, and Edible Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. Var. capitata). Sci. Hortic. 2013, 150, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gu, M.; Cui, J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. Effects of Light Quality on CO2 Assimilation, Chlorophyll-Fluorescence Quenching, Expression of Calvin Cycle Genes and Carbohydrate Accumulation in Cucumis sativus. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2009, 96, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyvast, G.; Olfati, J.-A.; Madeni, S.; Forghani, A.; Samizadeh, H. Vermicompost as a Soil Supplement to Improve Growth and Yield of Parsley. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2008, 14, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Mou, B. Short-Term Effects of Composted Cattle Manure or Cotton Burr on Growth, Physiology, and Phytochemical of Spinach. HortScience 2016, 51, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; He, D.; Ji, F.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J. Effects of Daily Light Integral and LED Spectrum on Growth and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponic Spinach. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, R.A.; Jones, J.M.; Kern, M.; Lee, S.; Mayhew, E.J.; Slavin, J.L.; Zivanovic, S. Functionality of Sugars in Foods and Health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 433–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic-Malinovska, R.; Kuzmanova, S.; Winkelhausen, E. Oligosaccharide Profile in Fruits and Vegetables as Sources of Prebiotics and Functional Foods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutasknit, A.; Ait-Rahou, Y.; Anli, M.; Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Meddich, A. Improvement of Garlic Growth, Physiology, Biochemical Traits, and Soil Fertility by Rhizophagus Irregularis and Compost. Gesunde Pflanz. 2021, 73, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Atamanalp, M.; Turan, M.; Alak, G.; Kul, R.; Kitir, N.; Yildirim, E. Integrated Use of Nitrogen Fertilizer and Fish Manure: Effects on the Growth and Chemical Composition of Spinach. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Huang, H.; Hao, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, H. Nutritional Quality, Mineral and Antioxidant Content in Lettuce Affected by Interaction of Light Intensity and Nutrient Solution Concentration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantis, F.; Fotelli, M.; Ilić, Z.S.; Koukounaras, A. Physiological and Phytochemical Responses of Spinach Baby Leaves Grown in a PFAL System with Leds and Saline Nutrient Solution. Agriculture 2020, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.A.; Fernandes, Â.; Plexida, S.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.; Chrysargyris, A.; Tzortzakis, N.; Petrović, J.; Soković, M.D. The Sustainable Use of Cotton, Hazelnut and Ground Peanut Waste in Vegetable Crop Production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuolienė, G.; Viršilė, A.; Brazaitytė, A.; Jankauskienė, J.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Vaštakaitė, V.; Novičkovas, A.; Viškelienė, A.; Sasnauskas, A.; Duchovskis, P. Blue Light Dosage Affects Carotenoids and Tocopherols in Microgreens. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, B. Nutrient Content of Lettuce and Its Improvement. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2009, 5, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.; Al-Taher, F.; Abshiru, N. Extraction and Natural Bioactive Molecules Characterization in Spinach, Kale and Purslane: A Comparative Study. Molecules 2021, 26, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Plexida, S.; Chrysargyris, A.; Tzortzakis, N.; Calhelha, R.C.; Ivanov, M.; Stojković, D.; Soković, M. The Effects of Biostimulants, Biofertilizers and Water-Stress on Nutritional Value and Chemical Composition of Two Spinach Genotypes (Spinacia oleracea L.). Molecules 2019, 24, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Sirtautas, R.; Viršilė, A.; Sakalauskaitė, J.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Duchovskis, P. LED Illumination Affects Bioactive Compounds in Romaine Baby Leaf Lettuce. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3286–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandian, L.; Nemati, H.; Moghaddam, M. Effects of Bentonite Application and Urea Fertilization Time on Growth, Development and Nitrate Accumulation in Spinach (Spinacia oleraceae L.). Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.D. The Fine Control of Cytosolic PH. Physiol. Plant. 1986, 67, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Kong, Y.; Lv, Y.; Cao, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. Effect of Different LED Light Quality Combination on the Content of Vitamin C, Soluble Sugar, Organic Acids, Amino Acids, Antioxidant Capacity and Mineral Elements in Green Onion (Allium fistulosum L.). Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultberg, M.; Jönsson, H.L.; Bergstrand, K.-J.; Carlsson, A.S. Impact of Light Quality on Biomass Production and Fatty Acid Content in the Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 159, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Kokai, Y.; Ohtani, S.; Hada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Mizushina, Y. Inhibitory Effects of Preventive and Curative Orally Administered Spinach Glycoglycerolipid Fraction on the Tumor Growth of Sarcoma and Colon in Mouse Graft Models. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saapilin, N.S.; Yong, W.T.L.; Cheong, B.E.; Kamaruzaman, K.A.; Rodrigues, K.F. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa Var. Chinensis) to Different Light Treatments. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, F.; Balducci, F.; Capocasa, F.; Visciglio, M.; Mei, E.; Vagnoni, M.; Mezzetti, B.; Mazzoni, L. Environmental Conditions and Agronomical Factors Influencing the Levels of Phytochemicals in Brassica Vegetables Responsible for Nutritional and Sensorial Properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, D.P.; dos Santos Pinto Júnior, E.; de Menezes, A.V.; de Souza, D.A.; de São José, V.P.B.; da Silva, B.P.; de Almeida, A.Q.; de Carvalho, I.M.M. Chemical Composition, Minerals Concentration, Total Phenolic Compounds, Flavonoids Content and Antioxidant Capacity in Organic and Conventional Vegetables. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Huang, D.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Deemer, E.K. Analysis of Antioxidant Activities of Common Vegetables Employing Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) and Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assays: A Comparative Study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3122–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, U.; Sgherri, C.; Miranda-Apodaca, J.; Micaelli, F.; Lacuesta, M.; Mena-Petite, A.; Quartacci, M.F.; Muñoz-Rueda, A. Concentration of Phenolic Compounds Is Increased in Lettuce Grown under High Light Intensity and Elevated CO2. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herms, D.A.; Mattson, W.J. The Dilemma of Plants: To Grow or Defend. Q. Rev. Biol. 1992, 67, 283–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Amaki, W.; Watanabe, H. Effects of Monochromatic Light Irradiation by LED on the Growth and Anthocyanin Contents in Leaves of Cabbage Seedlings. In Proceedings of the VI International Symposium on Light in Horticulture; International Society for Horticultural Science: Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2009; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Goins, G.D.; Yorio, N.C.; Sanwo, M.M.; Brown, C.S. Photomorphogenesis, Photosynthesis, and Seed Yield of Wheat Plants Grown under Red Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) with and without Supplemental Blue Lighting. J. Exp. Bot. 1997, 48, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera, C.; Díez-Piqueras, J.; Gallegos-Cedillo, V.M.; Giménez, A.; Moreno, D.A.; Ros, M.; Pascual, J.A. Influence of Continuous and Pulsed Light on the Yield and Phytochemical Composition of Capsicum annuum L. Cv.‘Padrón. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2026, 106, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Alves-Pereira, I.; Ferreira, R.M.A. Plant Growth, Phytochemical Accumulation and Antioxidant Activity of Substrate-Grown Spinach. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pola, W.; Sugaya, S.; Photchanachai, S. Color Development and Phytochemical Changes in Mature Green Chili (Capsicum annuum L.) Exposed to Red and Blue Light-Emitting Diodes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 68, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Howard, L.R.; Prior, R.L.; Morelock, T. Flavonoid Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Spinach Genotypes Determined by High-performance Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, U.K.S.; Oba, S.; Yanase, E.; Murakami, Y. Phenolic Acids, Flavonoids and Total Antioxidant Capacity of Selected Leafy Vegetables. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwankaew, J.; Nguyen, D.T.; Kagawa, N.; Takagaki, M.; Maharjan, G.; Lu, N. Growth and Nutrient Level of Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forssk.) in Response to LED Light Quality in a Plant Factory. In International Symposium on New Technologies for Environment Control, Energy-Saving and Crop Production in Greenhouse and Plant Factory—GreenSys 2017; International Society for Horticultural Science: Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2017; pp. 653–660. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.