Abstract

This study aimed at developing in vitro propagation methods for Crocus sativus L., focusing on the effectiveness of temporary immersion systems (TIS) or bioreactors as an alternative, cost-efficient technique for the large-scale production of saffron corms. The effects of the culture system and cross-cutting on saffron propagation were evaluated. Saffron shoots were cultured in TIS and compared with shoots produced using a conventional semi-solid tissue culture system (SS). The recipient material for automated temporary immersion used in this study was the SETIS™ bioreactor. The growth parameters measured for in vitro culture were the number of neo-formed shoots, shoot height, and the number and size of corms. Based on the present detailed study, the highest shoot multiplication rate (9.1 shoots/explant with 7.2 cm of shoot height) was achieved in the TIS system after shoot cross-cutting, while the lowest multiplication rates were obtained in the semi-solid system (1 shoot/explant with 14.8 cm long shoots). Furthermore, the highest corm formation was obtained in the TIS system, with an average of four corms per explant, with a larger corm weight (10.90 g) and diameter (21.78 mm). These findings highlighted for the first time the efficiency of the bioreactor system combined with cross-cutting of the shoot for efficient and scalable saffron corm propagation, thus making a valuable contribution to sustainable cultivation and conservation strategies while meeting the growing demand for this spice.

Keywords:

saffron; Crocus sativus L.; temporary immersion; SETIS™; bioreactor; shoot; micropropagation; hyperhydricity 1. Introduction

Crocus sativus L. is a plant belonging to the Iridaceae family [1] known as ‘red gold’ and produces the world’s most expensive spice, extracted from the red stigma of its flower [2,3,4]. Saffron is known for its traditional uses in food, perfume, textiles, and folk medicine, and is used as a sedative, anti-asthma, and stomachic agent. Recently, several studies have uncovered its broad-spectrum properties, including antioxidant, fungicidal, anticancer, cardiovascular protection, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Owing to its unique value and properties, the demand for saffron spices has been growing recently. Saffron is vegetatively propagated by corms because of its sterility [4,14,15]. Nevertheless, traditional propagation methods do not ensure the availability of high-quality planting saffron corm material capable of sustaining large-scale growth and production.

In vitro plant tissue culture technology may offer a feasible alternative propagation method, and consequently, large-scale production of genetically homogeneous, disease-free, high-quality saffron corms [16]. Temporary immersion systems (TIS) are novel advanced tools for commercial micropropagation, displaying advantages compared to the conventional culture system (semi-solid medium), including reduction in production cost and promotion of biological yield, increased chlorophyll synthesis, and stomatal functionality, as well as the multiplication rate of in vitro explants [17] using temporary immersion. The huge success of TIS in the micropropagation of several plant species is due to several factors, including the high uptake of nutrients by plant explants in a liquid system, which increases the photosynthesis and respiration of explants. Significant research studies have been conducted since the first report on the application of temporary immersion systems. This culture system has been proven to be effective in many plant species, and different authors have indicated that the microenvironment within a TIS improves nutrient availability and uptake and enhances gas exchange [18,19]. Thus, it leads to a higher multiplication rate, better physiological status, and greater biomass growth.

To the best of our knowledge, two temporary immersion systems have been previously tested for in vitro saffron micropropagation, including ebb and flow and Plantform™ bioreactors reported by Dewir et al. [16] and Tarraf et al. [20]. However, the SETIS™ bioreactor system investigated in the present study has not yet been explored. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to assess the potential of the temporary immersion system (liquid medium) compared to a conventional culture system (semi-solid medium) for enhancing in vitro saffron propagation. In addition, we examined the combined effect of cross-cutting treatment with the culture system to determine whether their interaction could further improve shoot growth and corm formation.

While earlier research by El Merzougui et al. [4] demonstrated that cross-cutting treatment boosted saffron shoot multiplication and corm formation under controlled conditions, its performance in vitro has not been explored. Consequently, in the present study, we aimed to test the effect of cross-cutting treatment on corms and in vitro shoots multiplication. We hypothesize that combining the cutting treatment with the culture system will produce a synergistic effect, thereby further increasing in vitro growth and overall saffron productivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Crocus sativus corms were collected from the Taliouine/Taznakht region of Morocco during the summer dormancy period (July). Subsequently, they were carefully stored in a dry and dark place until they were ready to be used for the experiment.

2.2. Surface Disinfection and Establishment of Culture

Healthy, disease-free saffron corms were used, and all injured or infected corms were discarded. The corms were gently scrubbed under running tap water for 15 min for surface disinfection. Subsequently, they were cleaned with commercial liquid detergent and kept under tap water for 25 min. Following preliminary cleaning, the corms were either used intact as explants or aseptically dissected using a sterile razor blade. Dissection focused on the basal region and the part of the corm that was in direct contact with the soil. The explants obtained measured approximately 1–1.5 cm in length, a size reduction intended to enhance the efficiency of disinfection. The explants were immediately transferred to a laminar airflow cabinet, where they were immersed in 70% ethanol for 1 min and then submerged in 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 20 min. Sterilized explants were rinsed three more times using distilled water and air-dried for 5 min.

2.3. In Vitro Corm Cross-Cuttings

The effect of in vitro cross-cutting was carried out after surface disinfection, and all cutting treatments were performed as previously described by El Merzougui et al. [4]. Under sterile conditions, using a sterile blade, the saffron corms were cut without separation of the corm: (i) basal cutting treatment (BC), in which saffron corms were cut from the bottom to the top, and (ii) top-to-bottom cutting treatment (CTB), where the saffron corms were cut through the center from top to bottom. The control group was left intact without any cutting. Subsequently, the corms were cultured in MS Murashige and Skoog [21] medium (PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) supplemented with 3% sucrose and 2.75 mg/L 6-Benzylaminopurine (BA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in combination with 0.25 mg/L 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Establishment of In Vitro Corm Multiplication

Corms were inoculated in two culture systems: (i) semi-solid medium (SS), in which each corm was cultured in a single container (PhytoCon™ culture vessels (32 oz [946 mL], PhytoTech Labs) with 100 mL medium solidified with 0.3% phytagel, and (ii) in temporary immersion bioreactors (SETIS™, VERVIT, Beervelde, Belgium, TIS) with immersion and aeration frequency of 1.5 h and immersion for 2 min.

2.5. Effect of Cross-Cutting on In Vitro Shoot Multiplication

Eight-week-old in vitro shoots regenerated in the SS system served as explants for shoot multiplication, and the effects of two main factors on the growth and multiplication of the shoots were investigated: (i) the effect of cross-cutting treatment (BC cutting) on the reformation of new shoots and (ii) the effect of the culture system on shoot growth and multiplication. After cross-cutting (BC cutting), in vitro shoots were cultured in MS medium supplemented with 3% sucrose, 2.75 mg/L 6-Benzylaminopurine (BA), and 0.25 mg/L 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), in the SS and TIS bioreactor (SETIS™). For the semi-solid culture system, a single explant was cultured individually in separate PhytoCon™ culture vessels (32 oz [946 mL]) containing 100 mL medium solidified with 0.3% Phytagel. Meanwhile, in the temporary immersion system (TIS), a total of 30 explants were used in the experiment. Ten explants were cultured per flask in SETIS™ bioreactors containing 1000 mL of liquid medium. Immersion frequencies were applied for 2 min every 1.5 h in the SETIS™ system. Three flasks were used per treatment, resulting in three replicates per treatment. In both culture systems, the volume of culture medium was standardized to 100 mL per explant. All experiments were conducted using a completely randomized design.

The growth and morphological parameters of in vitro shoots were measured after three months of culture as follows: in vitro shoot height, number of shoots per bud, and leaf aspect.

2.6. Effect of Cross-Cutting and Different Culture Systems on Corm Formation

In vitro, corm formation was carried out using MS medium supplemented with 6% sucrose and 2.5 mg/L Paclobutrazol (PBZ). In the corm formation stage, the immersion frequencies were applied for 2 min every 4 h in the TIS system (SETIS™ bioreactors).

2.7. Culture Condition and Data Collection

Both the semi-solid system cultures and temporary immersion system (TIS) cultures were maintained in a growth chamber at 25 ± 2 °C under a 16 h photoperiod provided by LED light (Valoya’s L-Series LED grow light, model L35-144, 35 W AP67 spectrum; 14% Blue, 16% Green, 53% Red, and 17% Far Red; Valoya, Helsinki, Finland), with a light intensity of 79 µmol m−2 s−1. In vitro saffron shoot cultures were grown under these light conditions, while corms were incubated in complete darkness to promote corm development.

For shoot growth and multiplication, growth and morphological parameters were recorded, including shoot height and number of shoots per bud. Moreover, the number and size of corms were recorded at the end of the experiment.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The present study was conducted following a completely randomized experimental design. Data values were recorded and subjected to a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effect of culture system and cross-cutting treatment. The mean comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to investigate the multivariate relationships among treatments based on morphological parameters, including shoot length, number of corms, and corm diameter. All statistical analyses were conducted using R-Studio 2026.01.0 Build 392 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) software.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Cross-Cutting on In Vitro Corm Multiplication

The use of corm as a source of explant material presents a major challenge for the establishment of a clean culture. In our first experiment, a high contamination rate of explants was recorded, reaching 100% in TIS culture and 80% in semi-solid medium. Therefore, due to the high contamination level and the limited number of surviving explants, no data were collected, and no analysis could be performed. Hence, in vitro clean shoots were selected for the next study to evaluate the effect of cross-cutting on shoot growth and development.

3.2. Effect of Cross-Cutting on In Vitro Shoot Multiplication

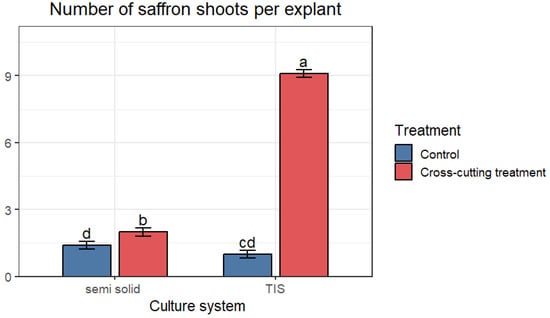

At the in vitro multiplication phase, the average number of regenerated shoots ranged from 1 ± 0.19 to 9.1 ± 0.27 shoots per single bud explant. This finding indicates that both the culture system and the cross-cutting treatment affect the shoot regeneration. Significant differences were observed among all treatments (Figure 1), with the highest number of shoots obtained after cross-cutting of in vitro shoots in the TIS system (SETIS™), with an average of 9.1 shoots per explant. This was followed by 2 shoots per explant obtained after cross-cutting of shoots cultured in semi-solid medium. The lowest numbers, with an average of 1.4 and 1 shoot per explant, were obtained with the control group (uncut) cultured in semi-solid and TIS systems, respectively (Figure 2 and Figure 6). These findings highlighted that while the cross-cutting treatment could enhance the shoot regeneration, the maximum shoot regeneration was achieved when the cross-cut shoots were cultured in the TIS system.

Figure 1.

Average of saffron in vitro shoots per explant obtained in semi-solid medium and TIS after cross-cutting. Data are presented as means ± SE. The different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference between treatments according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

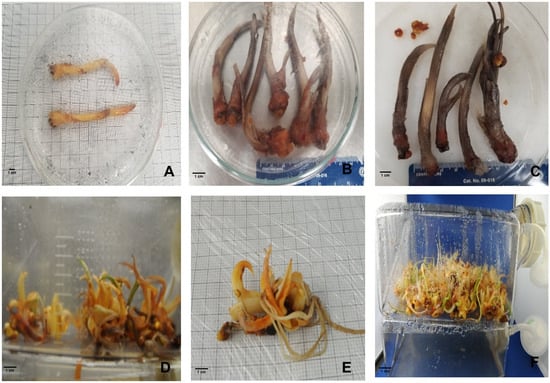

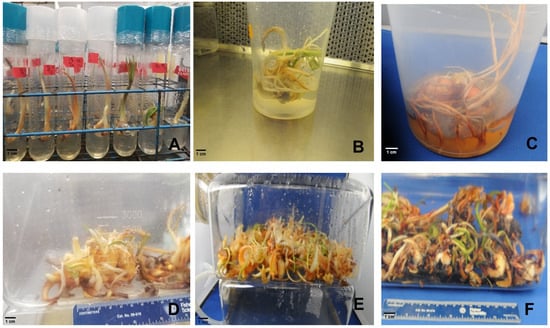

Figure 2.

In vitro shoot proliferation of saffron in SETISTM bioreactor system after shoot cross-cutting. (A,B) In vitro control group in the TIS system; (B,C) hyperhydricity symptoms on saffron shoots in the TIS system; (D–F) in vitro shoot proliferation after cross-cutting.

The effects of in vitro cross-cutting of the shoots and culture system on shoot growth and length were studied, and the results are presented in Table 1. According to ANOVA analysis, a significant difference in shoot growth among the treatments was observed; the highest shoot length, with an average of 14.8 cm, was obtained in the uncut group’s culture in the semi-solid medium, followed by the cross-cutting culture inoculated in the semi-solid medium, with an average of 9.1 cm. In contrast, the lowest shoot height was recorded in the shoot culture in the TIS system, with an average of 8.47 cm and 7.21 cm of height recorded in the control group (uncut shoot) and the cut shoot, respectively. These findings demonstrate that both the culture system and the cross-cutting treatment significantly influenced shoot growth and height, with the semi-solid medium in the control group resulting in the highest growth, whereas the TIS system with cutting treatment resulted in a significant reduction in growth. For shoot growth and multiplication, normal shoot growth was recorded in the cross-cut group in the continuous immersion bioreactor SEITIS (TIS), with normal shoot regeneration and leaves showing no signs of hyperhydricity (Figure 2D,E). Contrary to the control group (uncut group), almost all of the in vitro shoots cultured (≃80%) in the TIS bioreactors showed anomalous growth with a clear sign of hyperhydricity (Figure 2B,C).

Table 1.

Average height and hyperhydricity rate of saffron in vitro shoots were measured on both culture systems. Data are presented as means ± SE. The different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference between treatments according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

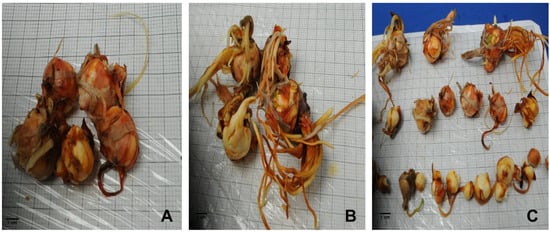

3.3. Effect of Cross-Cutting on In Vitro Cormlet Formation

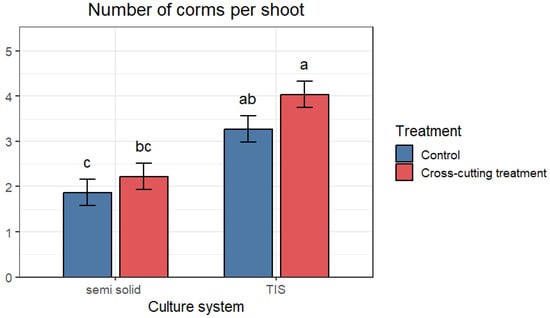

Two factors were studied in this experiment: the cross-cutting of shoots and two different culture systems, which were compared to evaluate the appropriate system for growth and corm formation. The results are shown in Figure 3. A highly significant difference in the number of corms formed was recorded across the treatments. The highest mean number of corms formed was obtained in TIS, with an average of 4 and 3.27 corms per shoot explant. In contrast, the lowest mean number of corm formations was recorded in the semi-solid system, with an average of 1.87 and 2.23. Furthermore, cross-cutting also significantly increased the number of corms formed, with the highest number occurring after shoot cross-cutting treatment. For the semi-solid system, an average of 1.87 and 2.23 was recorded in the control and cross-cut groups, respectively, whereas an average of 3.27 and 4.04 corms per shoot was obtained in the TIS system (SETIS™) for the control and cross-cut groups, respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 3.

Mean number of regenerated saffron corms in both culture systems. Data are means ± SE. The different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference between treatments according to Tukey’s (p < 0.05).

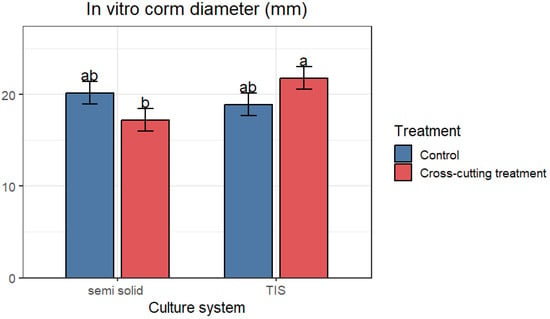

The two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference across the culture system and cross-cutting treatment. The cross-shoot cutting treatment had a significant influence on the production of cormlets. This treatment markedly increased the diameter of the corms produced within the TIS system (Figure 4). The largest corm, with an average of 21.78 mm, was achieved following cross-shoot cutting in the TIS system (SETIS™), whereas the smallest corm, with an average of 18.90 mm, was observed in the control group within the same system. Conversely, the cross-cut exerted a detrimental effect on in vitro corm production in the conventional system; the control group cultured in SS exhibited the largest corm with an average diameter of 20.16 mm, while the smallest corms with an average of 17.21 mm were recorded following cross-shoot cutting in the SS system (Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Average diameter of in vitro regenerated saffron corms assessed in both cultivation systems. Data are presented as means ± SE. The different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference between treatments according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

The results of the effects of shoot cross-cutting and culture system presented in Table 2 showed no significant difference in corm weight. However, the highest corm weight, with an average of 10.90 g, was observed in the TIS system after cross-cutting of the shoot, followed by the control group cultured in a semi-solid medium. The lowest average corm weight was observed in semi-solid medium after shoot cutting.

Table 2.

Mean in vitro saffron corm weight (g) measured after shoot cross-cutting.

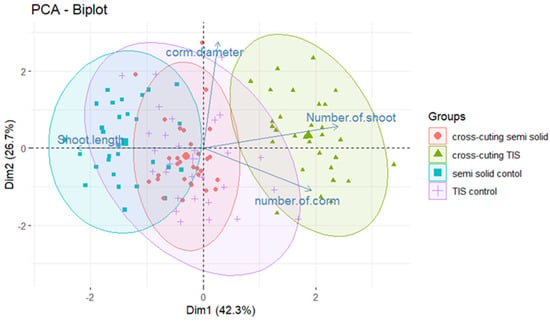

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of System Culture and Cross-Cutting on In Vitro Morphological Traits

PCA was performed to uncover the correlation of different parameters, specifically the culture system and cross-cutting treatment, with the key morphological traits of in vitro corm formation, including the number of corms and corm diameter (Figure 5). The PCA biplot in Figure 5 illustrates distinct clustering patterns in the distribution of the treatment groups along the first two components, Dim 1 (42.3%) and Dim 2 (26.7%), which together accounted for 68.9% of the total variance. The semi-solid treatment, in conjunction with the control group of culture (without BC cross-cutting), was strongly associated with increased shoot length, indicating its efficacy in promoting shoot growth and elongation. Conversely, the same culture system with cross-cutting was positively correlated with the number of corms and the number of shoots, indicating that this treatment enhanced both corm formation and shoot proliferation. Furthermore, the TIS system combined with cross-cutting demonstrated a positive alignment with all evaluated morphological traits, including shoot proliferation and corm number and diameter, making it the most effective overall among the treatments.

Figure 5.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot showing the effect of system culture and BC cross-cutting on all in vitro morphological traits of saffron. The first two components (Dim 1: 42.3%; Dim 2: 26.7%) capture the key variance. The parameters considered include the number of shoots, shoot length, corm size, and number of corms. Relationships and contributions are color-coded according to their magnitude.

4. Discussion

Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) is a highly treasured medicinal plant, known as “red gold” due to its economic value. Recently, the global demand for saffron has increased owing to its enormous application in the food and skincare industries and its medicinal value [3]. However, saffron production is limited by its production method and biotic and abiotic stresses [15,22]. Meeting this growing demand necessitates the development of alternative production strategies, such as tissue culture.

Tissue culture technology is an efficient method for the commercial production of plant species. It has been proven to be efficient in various plant production processes via a conventional system (semi-solid), yet its applications are hindered by high labor costs and a lack of automation. Thus, the TIS system has emerged as a promising alternative solution for greater efficiency and cost-effective suitability for large-scale production [23]. This current study investigated the efficiency of the two culture systems for in vitro saffron production. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the in vitro regeneration of shoots and corms via SETIS bioreactors. By evaluating the effect of the culture system and cutting treatment for scaling production in vitro, this work thereby opens up a new possibility for efficient propagation of C. sativus.

The establishment of a clean culture poses a major challenge, especially when underground parts of plants, such as corms, tubers, and rhizomes, are used as explants. Saffron disinfection protocols and their effectiveness and contamination rates have rarely been described in the literature [24]; however, several studies have highlighted the main factors that could affect the efficiency of sterilization: the physiological state of the stock plant; size, age, and type of explant; type, concentration, and duration of sterilization agent; and the temperature of treatment [16,25]. In the present work, the selection of sodium hypochlorite was deliberate, despite the well-documented use and efficacy of mercuric chloride (HgCl2). This choice was guided by the contemporary environmental principles of safety and responsible laboratory practice. In contrast to HgCl2, which poses a significant risk to human health and the environment, sodium hypochlorite provides a non-toxic and more sustainable alternative for explant disinfection.

High levels of contamination were recorded in both culture systems with the use of the entire corm as an explant, despite precleaning and disinfection protocols based on sodium hypochlorite treatment, indicating that the surface disinfection method adopted using sodium hypochlorite was not efficient. Similar findings were reported by Cavusoglu et al. [26] after using H2O2 for saffron corm sterilization. In contrast to the study reported by Yasmin et al. [27], the lowest level of contamination could be achieved after a three-step disinfection process was carried out for surface disinfection: fungicide treatment with carbendazim (0.01%) and mancozeb (0.1%), followed by 10 min of bleach treatment and 5 min of 1.6% mercuric chloride for 94% of the clean culture. Notably, reducing explant size to approximately 1–1.5 cm in length before treatment proved to be more effective for enhancing disinfection efficiency and improving culture establishment.

Propagation through a liquid system has several advantages over a semi-solid system. However, continuous immersion of explants in a liquid medium could have negative effects on explants, such as asphyxiation [28,29,30]. Therefore, a temporary immersion system, which offers a transition between dry and liquid immersion of plant tissues, has overcome these limitations and offers adequate nutrient uptake and high gas exchange. Different TIS systems have been successfully reported for micropropagation of several species [31,32,33,34,35].

Comparative evaluation of the two systems for the control group (uncut shoots), the conventional system (semi-solid), and the temporary immersion system demonstrated that both systems supported the shoot growth, while no significant difference in shoot length and multiplication was obtained. These results contrast with the findings reported by Martínez-Estrada et al. [36] for the Anthurium andreanum Lind., in which a production of an average of 31.50 shoots per explant was obtained in TIS. Similarly, Shaik et al. [37] reported that the highest shoot multiplication of Lessertia frutescens L. was recorded in TIS compared to the SS system. Ramos-Castellá et al. [38] demonstrated a significant increase in the shoot multiplication rate of Vanilla planifolia using TIS; the highest multiplication rate achieved was 14.27 shoots per explant with an immersion frequency of 2 min every 4 h. In contrast, the lowest rate, 5.80 shoots per explant, was observed under semi-solid culture conditions. In another study by Palaz et al. [39], they found that the Rhus coriaria shoot lengths in the platform bioreactor were significantly higher than the shoot lengths cultured in the SS system, with an average of 72.33 mm and 44.67 mm, respectively.

Although no significant difference in shoot multiplication and elongation was observed in both culture systems, further analysis highlighted a clear advantage of the TIS system in the in vitro saffron corm formation. A significant increase in the number of daughter corms was recorded in TIS for both the cross-cut and the control groups compared to those recorded in the semi-solid medium (Figure 7). The highest mean of in vitro corm obtained in the TIS system was 4.4 corm per single shoot, while the lowest was obtained in the SS system with 1 corm per shoot explant. This finding aligns with prior research on saffron reported by Dewir et al. [16] and Tarraf et al. [20], which emphasized that bioreactors promote saffron’s corm formation. Collectively, these results indicate that the TIS system supports saffron in vitro propagation and multiplication, highlighting its advantages over the SS system. Similar findings of the efficacy of TIS compared to the semi-solid system have also been proven for Blueberry and Cloudberry [40], pistachio [41], banana (Musa AAA cv. Grand Naine) [42], and Bletilla striata [43] propagation. This high multiplication rate on TIS with respect to the semi-solid system is due to several factors, including the high superficial contact of liquid medium with the explant, thus more stimulation of nutrients and PGRs, the renewal of air inside the bioreactor vessel, and the dilution of exuded inhibitors released by explants, such as phenols [44,45,46].

The cross-cutting treatment alone for in vitro shoot showed a significant improvement in saffron in vitro shoot multiplication. The highest mean shoot regeneration was 9.1 and 2 shoots per single explant after cutting treatment in TIS and SS systems, respectively (Figure 6B,D,E). The lowest mean recorded was 1 and 1.4 shoots per explant in TIS and SS systems, respectively. We speculated that cross-cutting induced shoot regeneration. These results suggest that cross-cutting of the shoot stimulates axillary shoot growth and overcomes bud apical dominance. Similar results were reported by El Merzougui et al. [4] for saffron corm formation under controlled conditions and by Ren et al. [47] for bulblet multiplication of Lycoris sprengeri. In contrast, no significant effect of cross-cutting was obtained on shoot length and corm formation in the present study. These findings are inconsistent with those reported by El Merzougui et al. [4], who indicated a significant effect of cutting on corm formation.

Figure 6.

Micropropagation of saffron under different culture systems. (A) in vitro shoot growth; (B) in vitro shoot multiplication; (C) in vitro corm formation in semi-solid medium; (D) in vitro shoot multiplication on TIS system; (D,E) in vitro corm formation on TIS (SETIS™), (F) in vitro corm formation on TIS.

Furthermore, signs of hyperhydricity or vitrification were recorded in the control group cultured in the TIS system (Figure 2B,C). This is a common phenomenon found in the in vitro propagation, which affects shoot growth. Various authors have reported tissue necrosis and vitrification problems in TIS systems in blueberries, bananas, and other plant species [48,49]. This problem can be prevented or controlled through further optimization of different factors, including immersion frequency, PGR concentration, and composition of the culture medium [19,36].

The combined effect of cross-cutting treatment with culture systems on the in vitro shoot and daughter corm formation and multiplication was evaluated. The results demonstrated further enhancement in the in vitro saffron multiplication compared with the culture system alone. This synergetic approach not only improved the shoot multiplication rate but also produced a higher number, size, and weight of saffron cormlets, exhibiting robust overall performance compared to the control group in the SS system (Figure 7B,C). Notably, this synergetic treatment improved shoot growth without any sign of hyperhydricity in the TIS system (Figure 6D,E) while promoting adventitious shoot regeneration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to evaluate the effect of shoot cross-cutting on corm development, thereby supporting the consistency of BC cross-cutting of shoots and its beneficial effect on high multiplication frequency. Comparative findings were reported by El Merzougui et al. [4] under controlled conditions. They demonstrated that the cross-cutting treatment of mother corm culture under controlled conditions significantly improved saffron corm production compared to the control corm (uncut).

Figure 7.

Saffron’s daughter corm formation using bud explants; (A) corm formed in semi-solid medium; (B,C) corm formed in TIS medium (SETIS™ biorector).

Overall, these findings highlight the potential of the SETIS bioreactor, either alone or in combination with cross-cutting treatment, to promote greater adventitious shoot regeneration, corm formation, and growth. Moreover, this study underscores, for the first time, the significant impact of cross-cutting of the shoot on the mass propagation of saffron corms and the reduction of the hyperhydricity symptom of the shoot in TIS bioreactors.

5. Conclusions

The present study establishes a revolutionary strategy for saffron propagation by integrating the temporary immersion system (TIS) with cross-cutting treatment. We demonstrated that the SETIS™ bioreactor is a more efficient system for saffron shoot and corm multiplication compared to the conventional system (SS). Furthermore, the BC cross-cutting treatment not only enhanced in vitro adventitious shoot regeneration but also helped mitigate hyperhydricity, ensuring high-quality, healthy shoot development. Moreover, the synergetic method of TIS with cross-cutting treatment further promotes overall in vitro shoot and saffron corm formation. These findings provide a robust foundation for a cost-effective, large-scale production method. Future research should focus on optimizing other factors, such as the explant’s density, immersion frequency, and medium composition. Additionally, the genetic fidelity assessment is recommended. Lastly, investigating acclimatization and field trial of in vitro saffron corm is necessary to confirm the efficiency of TIS bioreactors and for future sustainable agriculture strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.M., W.A.V. and M.A.S.; methodology, S.E.M., D.G.B.; validation, W.A.V., M.A.S. and D.G.B.; formal analysis, S.E.M. and R.E.B.; investigation, S.E.M. and T.S.C.; resources and data analysis, S.E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E.M.; review and editing, V.M.P., T.S.C. and R.E.B.; supervision, W.A.V. and M.A.S.; project administration, W.A.V. and M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Hassan II Academy of Sciences and Technologies (SafranVal project), the National Center for Scientific and Technical Research (PPR/2015/33 project), Morocco, and Ibn Zohr University, Morocco. The US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture has also provided support for this study under Hatch project 7001563.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude and appreciation to the local farmers of Taliouine and Taznakht, as well as to Dar Azaafarane. S.E.M. acknowledged support from a Fulbright Fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TIS | Temporary immersion systems |

| SS | Semi-solid tissue culture system |

| BA | 6-Benzylaminopurine |

| NAA | 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid |

| PBZ | Paclobutrazol |

| BC | Basal cutting treatment |

References

- El Merzougui, S.; Benelli, C.; El Boullani, R.; Serghini, M.A. The Cryopreservation of Medicinal and Ornamental Geophytes: Application and Challenges. Plants 2023, 12, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Devi, M.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S. Introduction of high-value Crocus sativus (saffron) cultivation in non-traditional regions of India through ecological modelling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Merzougui, S.; Boudadi, I.; El Fissi, H.; Lachheb, M.; Lachguer, K.; Lagram, K.; Ben El Caid, M.; El Boullani, R.; Serghini, M.A. Genomic DNA extraction from the medicinal plant Crocus sativus: Optimization of Standard Methods. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Merzougui, S.; Boudadi, I.; Lachguer, K.; Beleski, D.G.; Lagram, K.; Lachheb, M.; Ben El Caid, M.; Pereira, V.M.; Nongdam, P.; Serghini, M.A.; et al. Propagation of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Using Cross-Cuttings under a Controlled Environment. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, R.; Trevisani, F.; Vignolini, P.; Vita, C.; Fiorio, F.; Campo, M.; Ieri, F.; Di Marco, F.; Salonia, A.; Romani, A. Evaluation of anti-cancer potential of saffron extracts against kidney and bladder cancer cells. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Hamza, A.A.; Bajbouj, K.; Ashraf, S.S.; Daoud, S. Saffron: A potential candidate for a novel anticancer drug against hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011, 54, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskabady, M.-H.; Gholamnezhad, Z.; Khazdair, M.-R.; Tavakol-Afshari, J. Antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of saffron and its derivatives. In Saffron; Koocheki, A., Khajeh-Hosseini, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, X.; Zhao, C.; Cai, L.; Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Yin, H.-X.; Chen, C. Antioxidant potential of crocins and ethanol extracts of Gardenia jasminoides ELLIS and Crocus sativus L.: A relationship investigation between antioxidant activity and crocin contents. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, N.; Bouymajane, A.; Oulad El Majdoub, Y.; Ezrari, S.; Lahlali, R.; Tahiri, A.; Ennahli, S.; Laganà Vinci, R.; Cacciola, F.; Mondello, L. Flavonoid Composition and Antibacterial Properties of Crocus sativus L. Petal Extracts. Molecules 2022, 28, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara, S.; Petretto, G.L.; Mannu, A.; Zara, G.; Budroni, M.; Mannazzu, I.; Multineddu, C.; Pintore, G.; Fancello, F. Antimicrobial activity and chemical characterization of a non-polar extract of saffron stamens in food matrix. Foods 2021, 10, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeh-Hosseini, M.; Fallahpour, F. Emerging innovation in saffron production. In Saffron; Koocheki, A., Khajeh-Hosseini, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, T.; Mollaei, H.; Takhviji, V.; Bijari, B.; Zarban, A.; Rostami, Z.; Hoshyar, R. The anti-dyslipidemia property of saffron petal hydroalcoholic extract in cardiovascular patients: A double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 55, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordzadeh, A.; Saadatabadi, A.R.; Hadi, A. Investigation on penetration of saffron components through lipid bilayer bound to spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 using steered molecular dynamics simulation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachheb, M.; El Merzougui, S.; Boudadi, I.; El Caid, M.B.; El Mousadik, A.; Serghini, M.A. Deciphering phylogenetic relationships and genetic diversity of Moroccan saffron (Crocus sativus L.) using SSRg markers and chloroplast DNA SNP markers. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 162, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagram, K.; El Merzougui, S.; Boudadi, I.; Ben El Caid, M.; El Boullani, R.; El Mousadik, A.; Serghini, M.A. In vitro shoot formation and enrooted mini-corm production by direct organogenesis in saffron (Crocus sativus L.). Vegetos 2023, 37, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewir, Y.H.; Alsadon, A.; Al-Aizari, A.A.; Al-Mohidib, M. In vitro floral emergence and improved formation of saffron daughter corms. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arano-Avalos, S.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Sánchez-Páez, R.; Bello-Bello, J. An efficient protocol for commercial micropropagation of malanga (Colocasia esculenta L. Schott) using temporary immersion. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunakhonnuruk, B.; Inthima, P.; Kongbangkerd, A. Improving bacoside yield of Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst. in temporary immersion system by increasing immersion time and lowering the intervals. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 115859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Bayoudh, C.; Werbrouck, S.; Mars, M. Effects of meta–topolin derivatives and temporary immersion on hyperhydricity and in vitro shoot proliferation in Pyrus communis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 143, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, W.; İzgü, T.; Şimşek, Ö.; Cicco, N.; Benelli, C. Saffron In Vitro Propagation: An Innovative Method by Temporary Immersion System (TIS), Integrated with Machine Learning Analysis. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjlil, H.; Elkassemi, K.; Hamza, M.A.; Mateille, T.; Furze, J.N.; Cherifi, K.; Ferji, Z. Plant-parasitic nematodes parasitizing saffron in Morocco: Structuring drivers and biological risk identification. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L. Scaling-up procedures and factors for mass micropropagation using temporary immersion systems. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2025, 61, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiri, A.; Mazri, M.A.; Karra, Y.; Ait Aabd, N.; Bouharroud, R.; Mimouni, A. Propagation of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) through tissue culture: A review. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Kulus, D.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, S.; Ma, G.; Piqueras, A. Disinfection of explants for saffron (Crocus sativus) tissue culture. Environ. Exp. Biol. 2016, 14, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusoglu, A.; Sulusoglu, M.; Erkal, S. Plant regeneration and corm formation of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) in vitro. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 8, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin, S.; Nehvi, F.; Wani, S.A. Tissue culture as an alternative for commercial corm production in saffron: A heritage crop of Kashmir. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 3940–3946. [Google Scholar]

- Maurizio, L.; Roncasaglia, R.; Bujazha, D.; Baileiro, F.; da Silva, D.C.; Ozudogru, E. Improvement of shoot proliferation by liquid culture in temporary immersion. In Proceedings of the 6th International ISHS Symposium on Production and Establishment of Micropropagated Plants, San Remo, Italy, 19–24 April 2015; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadpour Barough, A.; Dianati Daylami, S.; Fadavi, A.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Vahdati, K. Enhancing photosynthetic efficiency in Phalaenopsis amabilis through bioreactor innovations. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, S.; Garrido, J.; Sánchez, C.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Codesido, V.; Vidal, N. A temporary immersion system to improve Cannabis sativa micropropagation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 895971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-D.; Kwon, S.-H.; Murthy, H.N.; Yun, S.-W.; Pyo, S.-S.; Park, S.-Y. Temporary immersion bioreactor system as an efficient method for mass production of in vitro plants in horticulture and medicinal plants. Agronomy 2022, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimäki, S.; Paavilainen, L.; Tikkinen, M.; Salonen, F.; Varis, S.; Aronen, T. Production of Norway spruce embryos in a temporary immersion system (TIS). In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2020, 56, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D.; Hahn, E.; Yoon, Y.; Paek, K. Micropropagation of apple rootstock M. 9 EMLA using bioreactor. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2003, 78, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San José, M.C.; Blázquez, N.; Cernadas, M.J.; Janeiro, L.; Cuenca, B.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N. Temporary immersion systems to improve alder micropropagation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 143, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.; Malnoy, M.; Aldrey, A.; Cernadas, M.J.; Sánchez, C.; Christie, B.; Vidal, N. Micropropagation of Apple Cultivars ‘Golden Delicious’ and ‘Royal Gala’in Bioreactors. Plants 2025, 14, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Estrada, E.; Islas-Luna, B.; Pérez-Sato, J.A.; Bello-Bello, J.J. Temporary immersion improves in vitro multiplication and acclimatization of Anthurium andreanum Lind. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.; Dewir, Y.; Singh, N.; Nicholas, A. Micropropagation and bioreactor studies of the medicinally important plant Lessertia (Sutherlandia) frutescens L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Castellá, A.; Iglesias-Andreu, L.; Bello-Bello, J.; Lee-Espinosa, H. Improved propagation of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews) using a temporary immersion system. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2014, 50, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaz, E.B.; Adali, S.; Yilmaz, A. Pioneering in vitro micropropagation of sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) using promising SPM medium in bioreactor system. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2025, 61, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath Samir, C. A two-step procedure for in vitro multiplication of cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus L.) shoots using bioreactor. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2007, 88, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, H.; Süzerer, V.; Onay, A.; Tilkat, E.; Ersali, Y.; Çiftçi, Y.O. Micropropagation of the pistachio and its rootstocks by temporary immersion system. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 117, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Cruz-Cruz, C.A.; Pérez-Guerra, J.C. A new temporary immersion system for commercial micropropagation of banana (Musa AAA cv. Grand Naine). In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2019, 55, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Song, L.; Bekele, L.D.; Shi, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, B.; Jin, L.; Duns, G.J.; Chen, J. Optimizing factors affecting development and propagation of Bletilla striata in a temporary immersion bioreactor system. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 232, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewir, Y.H.; Indoliya, Y.; Chakrabarty, D.; Paek, K.-Y. Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Hyperhydricity in Liquid Culture System; Paek, K.Y., Murthy, H., Zhong, J.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 693–709. [Google Scholar]

- Etienne, H.; Berthouly, M. Temporary immersion systems in plant micropropagation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002, 69, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.P.; Pan, L.; Xu, X.J.; Zhu, Y. Nitrifying treatment of wastewater from fertilizer production in a three-phase flow airlift loop bioreactor. Eng. Life Sci. 2003, 3, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.; Lin, Y.; Lv, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Gao, C.; Wu, Y.; Xia, Y. Clonal bulblet regeneration and endophytic communities profiling of Lycoris sprengeri, an economically valuable bulbous plant of pharmaceutical and ornamental value. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 279, 109856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, R.; Kundu, S.; Majumder, S.; Marshall, H.D.; Igamberdiev, A.U.; Debnath, S.C. Exploring two bioreactor systems for micropropagation of Vaccinium membranaceum and the antioxidant enzyme profiling in tissue culture-raised plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.P.; Luis, Z.G.; De Araújo Silva-Cardoso, I.M.; Gomes, A.C.M.M.; De Souza, A.L.X.; Scherwinski-Pereira, J.E. Comparative structural analysis of banana plantlets cultivated in semi-solid medium and in temporary immersion bioreactor. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2025, 61, 759–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.