Abstract

Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins play an essential role in plant growth under various abiotic stresses. In this study, we identified 23 RcLEA genes in Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ and subsequently grouped them into eight clades according to phylogenetic relationships and conserved domain features by bioinformatics methods. And conserved protein motifs and gene structure are also analyzed. The cis-regulatory elements of RcLEA promoter are enriched with cis-regulatory elements relevant to abiotic stress adaptation. Comparative transcriptomics between two species revealed tissue-specific and cold-induced expression differences, highlighting distinct functional roles of LEA genes in growth and abiotic stress tolerance between Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ and Rosa beggeriana. Furthermore, Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR validation confirmed divergent cold-responsive expression profiles of LEA genes in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ compared with the highly cold-tolerant R. beggeriana in four LEA homologous genes. These findings indicated that LEA acts as a cold-response gene in roses and provide foundation to breed cold-tolerant varieties of roses.

1. Introduction

Abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures disrupt crop growth and cause yield losses and quality decline [1]. Through evolution, plants have acquired molecular, physiological, and biochemical adaptations, prominently the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins, which respond to low temperature, abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene, drought, and salinity to protect cellular integrity [2,3,4]. First noted in maturing cotton seeds [5,6], LEA proteins have since been documented in rice [7], maize [8], soybean [9], and many other species. LEA proteins are now recognized as stress-inducible protectors expressed beyond seeds in seedlings, leaves, and roots under drought or salinity [10,11].

LEA proteins constitute a diverse family that can be classified into eight groups based on the Pfam database: LEA1, LEA2, LEA3, LEA4, LEA5, LEA6, dehydrin (DHN), and seed maturation proteins (SMP) [12]. These proteins are typically highly hydrophilic and glycine-rich, a property that contributes to their ability to stabilize cellular structures under stress conditions [13]. Members of different LEA groups have been implicated in a wide range of protective functions, including safeguarding cellular structures during dehydration (LEA1) [14], stabilizing membranes and mediating stress signaling (LEA2) [15], and enhancing drought and salt tolerance through antioxidant regulation (LEA3) [16]. LEA4 enhances tolerance to salt and drought too [17]. Other groups are associated with stress adaptation (LEA5) [18], seed longevity and desiccation tolerance via the glassy state (LEA6) [19], and seed maturation processes [20]. Dehydrins (DHNs) are particularly responsive to diverse abiotic stresses [21]. Drought resistance is enhanced by AtLEA3-3 in Arabidopsis [22], WZY3-1 in wheat [23], and GmPM35 in Glycine max [24]. Salt and osmotic stress tolerance are enhanced by CaDHN5 in pepper [25], MsLEA4-4 in alfalfa [26], and LEA12OR in wild rice [27]. ZmDHN15 has been shown to improve cold tolerance in maize. [28], VamDHN3 in Vitis amurensis [29], AmDHN4 in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus [30], PasLEA3-2, and Pasdehydrin-3 in P. armeniaca L. × P. sibirica L. [31].

Roses, being important ornamental plants and pivotal materials in the perfume industry, hold significant cultural and economic value worldwide. The cold resistance of roses can affect their growth, thereby influencing the promotion of their varieties. As the ancestor of modern repeat-flowering roses, Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ endows its descendants with perpetual bloom, compact habit, and vivid color, traits that significantly influenced global horticulture [32]. It serves as a crucial resource for understanding Rosaceae evolution and breeding. In contrast, Rosa beggeriana, a cold-resistant wild rose native to Central Asia, holds potential for improving cultivated roses through hybridization [33]. Cold-tolerant germplasm in roses remains limited, and existing cultivars exhibit insufficient hardiness. Our research team has previously conducted systematic studies on Rosa beggeriana, including its use in distant hybridization to develop the cold-hardy ‘Tianshan’ series of rose cultivars, the demonstration of its exceptional freezing tolerance and elucidation of the associated physiological mechanisms, as well as the characterization of phenotypic and genetic diversity of its natural populations in Xinjiang [34,35,36,37]. These earlier works establish a solid foundation for the current investigation into its molecular cold-tolerance mechanisms. Although LEA proteins play a notable role in plant low-temperature stress tolerance, their functions within the Rosa are still poorly understood.

This study systematically characterized the LEA gene family in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ by examining gene numbers, structural organization, and motif distribution. In addition, phylogenetic relationships, chromosomal localization, and duplication events were investigated. The cis-acting regulatory elements of LEA members were further predicted based on the available high-quality genome sequence [38]. Expression analysis of LEA genes under low-temperature treatment was conducted using transcriptome data to explore their role in cold resistance. Elucidating the cold resistance mechanisms of LEA genes in Rosaceae species offers a theoretical foundation for the genetic enhancement and breeding of cold-tolerant rose cultivars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Characterization of RcLEAs

The reference genome of R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’, along with its annotation, was retrieved from the LIPM database (https://lipm-browsers.toulouse.inra.fr/pub/RchiOBHm-V2/web/fatal/download/download.html, accessed on 1 January 2024). To detect LEA family members, Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles corresponding to LEA1 (PF03760), LEA2 (PF03168), LEA3 (PF03242), LEA4 (PF02987), LEA5 (PF00477), LEA6 (PF10714), DEHYDRIN (PF00257), and SMP (PF04927) domains were obtained from Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/, accessed on 1 January 2024) and applied in HMMER v3.3.2 searches (e-value < 1 × 10−5) [39]. In parallel, 51 Arabidopsis LEA proteins were collected from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 1 January 2024) and applied as queries in BLASTP (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome, accessed on 1 January 2024) screening against the R. chinensis proteome (cutoff e-value 1 × 10−5; Table S3). Pfam and NCBI Conserved Domain Database were used to validate candidate proteins for conserved domains subsequently (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/, accessed on 1 January 2024). Physicochemical properties, including sequence length, molecular mass, and theoretical pI, were calculated with the ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 1 January 2024).

2.2. Gene Structure, Motif, and Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of AtLEAs and RcLEAs

Phylogenetic relationships between 51 AtLEAs and 23 RcLEAs were established by the neighbor joining (NJ) method and bootstrap analysis (1000 replications) in MEGA11 program [40]. Conserved domains were annotated via NCBI CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml, accessed on 1 January 2024), while motifs were identified using MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/, accessed on 1 January 2024) [41]. Exon–intron structures of RcLEA genes were visualized with TBtools v2.376 [42]. Classification of LEA family members was achieved by integrating domain/motif information with phylogenetic clustering. Cis-regulatory elements within 2000 bp upstream regions were predicted using PlantCARE (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 1 January 2024) [43].

2.3. The Chromosomal Location and Duplication Analysis of RcLEAs

Chromosomal positions of RcLEA genes were extracted from genome annotations and mapped using TBtools v2.376. Sequence similarity searches (BLAST v2.16.0, e-value < 1 × 10−5) were performed to identify tandem and whole-genome duplication events, which were further confirmed with MCScanX v1.0.0 under default parameters [44]. Evolutionary constraints were assessed by calculating Ka/Ks ratios with KaKs_Calculator v3.0 (Table S4) [45].

2.4. Cis-Acting Element Analysis

Promoter sequences spanning 2000 bp upstream of RcLEA genes were analyzed using PlantCARE to predict cis-acting elements (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcate/html, accessed on 1 January 2024). The distribution of regulatory motifs was illustrated using TBtools.

2.5. Cold Stress Experimental Design and Plant Materials

Annual seedlings of R. beggeriana and R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ obtained by cutting propagation were maintained in a controlled chamber at 24 °C during the day and 18 °C at night under a 10 h light/14 h dark cycle. After a one-week adaptation period, seedlings of both species were subjected to cold treatments. Plants were exposed to 4 °C for 0, 1, 6, and 24 h, followed by −4 °C for 6 h and 24 h for qRT-PCR validation. For R. beggeriana, plants were maintained at 4 °C for 0, 1, 6, and 24 h for transcriptome analysis. Each treatment included three independent biological replicates, with 0 h serving as the control. For tissue-specific expression analysis, stem, leaf, root, flower, and fruit tissues of R. beggeriana were sampled under normal growth conditions.

2.6. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

Transcriptome data of R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ (Project accession: PRJNA546486) were downloaded from the SRA database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, accessed on 1 February 2024) [46] to examine the tissue-specific expression profiles of RcLEA genes. The corresponding genes in R. beggeriana were identified by sequence alignment using the R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ genome as a reference, following a one-to-one correspondence screening criterion. The tissue-specific expression heatmaps for both species were generated using TBtools based on fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values. Total RNA from the cold-treated samples described in Section 2.5 was used for transcriptome sequencing. The raw data for R. beggeriana are provided in Tables S7 and S8. The expression profiles of RbLEA genes under cold stress were visualized as heatmaps using TBtools based on FPKM values.

2.7. Experimental Validation by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To validate the RNA-Seq results, qRT-PCR was performed on the cold-treated samples described in Section 2.5. Total RNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Plant RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). qRT-PCR reactions were conducted using SupRealQ Ultra Hunter SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers for LEA genes were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (primer sequences are listed in Table S9). Rba-Tubulin was used as the reference gene for normalization. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and statistical significance was assessed as described in Section 2.8.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted with three independent biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v10.1.2. For qRT-PCR data, differences between treatments were evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Fold-change thresholds (>2-fold) were used to define biologically relevant differential expression.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of LEAs in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’

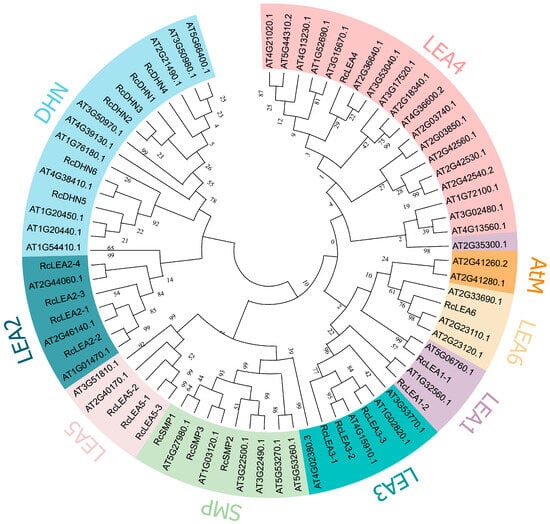

R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ had 23 LEA genes (Table S1). A neighbor joining (NJ) tree was constructed for the LEA members of A. thaliana and R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ (Tables S2 and S3). In total, 74 LEA genes were grouped into eight categories: LEA1, LEA2, LEA3, LEA4, LEA5, LEA6, SMP, and DHN (Figure 1). After analysis, the DHN gene family was the maximum subgroup including 6 of 23 LEA genes from R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’. The subfamily LEA2 was the next largest subgroup, comprising four LEA from R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’. Gene numbers differ among groups, with substantial variation compared to Arabidopsis. The species-specific group (AtM) of A. thaliana was not present in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’. Compared with A. thaliana, the number of genes in LEA4 of R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ is significantly reduced.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of LEA proteins of A. thaliana and R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’. Phylogenetic analysis was performed in MEGA 11 employing the neighbor-joining algorithm. The 8 subfamilies are distinguished by different colors.

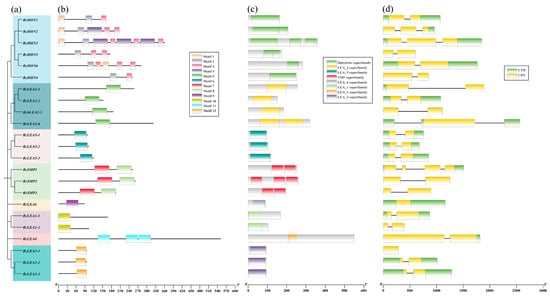

3.2. Motif Analysis, Conserved Domain Analysis, and Gene Structure Analysis of LEAs in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’

To analyze the structural features of RcLEA proteins, an unrooted phylogenetic tree incorporating motif, CDS, UTR, and gene structure information was constructed based on the full-length sequences of the 23 RcLEA genes (Figure 2, Figures S1 and S2). The location of motif overlaps with that of the conserved domain (Figure 2b,c). The DHN subfamily was predicted to have the largest number of motifs, with three types. The SMP subfamily had two types, while each of the other subfamilies had only one type. Meanwhile, the exon-intron structure of RcLEA genes was analyzed (Figure 2d). Notably, the DHN subfamily exhibits the widest range of structural diversity among all RcLEA groups, containing the most genes and displaying the most pronounced differences in exon–intron architecture. RcSMP1 has four exons. RcDHN2, RcDHN3, and RcLEA2-4 have three exons. RcLEA6 and RcLEA3-1 have one exon. The remaining genes all contain two exons. In general, RcLEA genes categorized under the same phylogenetic group were characterized by conserved exon–intron structures, a finding consistent with and supportive of the established evolutionary relationships and group classification.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships, motif distribution, conserved protein motifs, and gene structure analysis of LEAs in Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’. (a) Phylogenetic relationships among RcLEA proteins. MEGA 11 was used to construct phylogenetic tree by NJ method. Using the sequences of 23 RcLEA proteins, the bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replicates. (b) Distributions of motifs in RcLEA genes. Twelve types of predicted motifs are marked with distinct colored boxes. (c) Analysis of conserved domain of 23 RcLEA proteins. (d) Gene structure of RcLEA genes. CDS are represented by orange boxes; introns are represented by black lines.

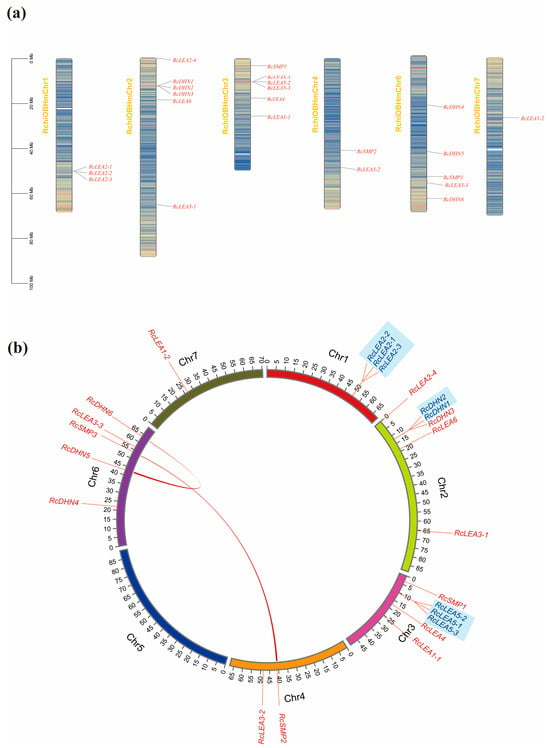

3.3. Synteny and Chromosomal Location Analysis of LEAs in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’

Twenty-three RcLEAs are distributed on the six chromosomes (Figure 2a). The LEA genes were unevenly distributed along the chromosome of R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’. There was no LEA gene distribution on Chr 5. The largest quantity of RcLEAs was found on Chr 2 and Chr 3, followed by Chr 6. Three genes located on Chr 1 and two genes on Chr 4. Chr 7 carried only one gene. Genes are non-uniformly distributed across chromosomes, with certain gene clusters exhibiting aggregation.

Gene family expansion and evolution are primarily driven by tandem and whole-genome duplication events. For RcDHN1 and RcDHN2, these two tandemly duplicated genes positioned on Chr 2. There are also two clusters of tandem duplications, one on Chr 1 consisting of RcLEA2-1, RcLEA2-2, and RcLRA2-3. The other group is located on Chr 3, which consisted of RcLEA5-1, RcLEA5-2, and RcLEA5-3. Furthermore, two whole-genome duplication events, including RcDHN5, RcDHN6, RcSMP2, and RcSMP3, were identified on three separate chromosomes (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Gene duplication and chromosomal location of the RcLEA genes. (a) The position of RcLEAs on chromosomes. (b) Whole-genome duplication and tandem duplication of the RcLEA genes. Whole-genome duplicated gene pairs are connected by red lines, while tandemly duplicated genes are highlighted in light blue.

The selective pressure on homologous gene pairs in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ were further investigated. We analyzed their Ka/Ks values (Table S4). All LEA homologous gene pairs exhibited Ka/Ks ratios under 1, reflecting the action of purifying selection throughout evolution. We also predicted the Ka/Ks ratios of AtLEAs (Table S4). Both ratios of these two species are less than 1, indicating that the family subjected to strong purifying selection and has highly conserved functions.

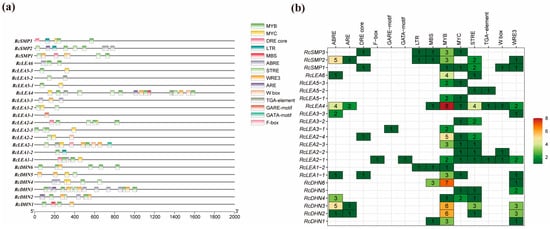

3.4. Promoters Analysis of the RcLEA Genes

For the analysis of cis-regulatory elements in RcLEAs, sequences spanning 2 kb upstream of the translation start sites of all LEA genes were retrieved from the Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ genome (Figure 4). In total, 14 types of cis-regulatory elements linked to stress tolerance were found, among them ABRE, ARE, DRE core, F-box, GARE-motif, GATA-motif, LTR, MBS, MYB, MYC, STRE, TGA-element, W-box, and WRE3 (Figure 4a). MYB transcription factors accounted for the largest proportion, whereas GARE transcription factors were the least represented, indicating the diversity of transcription factors associated with RcLEAs (Figure 4b). All RcLEA members harbored at least two cis-elements associated with stress adaptation. Among these, ABRE, MYB, and WRE3 motifs were particularly enriched, indicating their dominant role in the regulation of the RcLEA gene family (Figure 4). Table S5 summarizes the detailed profiles of cis-acting elements identified in each RcLEA gene.

Figure 4.

Predicted cis-acting elements in the promoters of RcLEA genes. (a) Promoter regions of RcLEA genes containing cis-elements. Different element classes are indicated by distinct colors and shapes. (b) Quantitative heatmap of cis-acting elements across the RcLEA gene promoters. The color gradient represents the predicted number of cis-acting elements, with green indicating a lower count and red indicating a higher count.

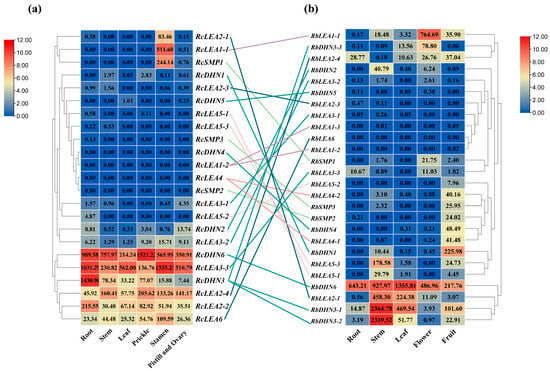

3.5. Expression Profiling of LEA Genes Under Cold Stress in Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’, with Comparative Patterns Assessed in Rosa beggeriana

RNA-Seq analysis revealed that RcLEA genes in Rosa chinensis displayed tissue-biased expression across stamen, root, stem, prickle, leaf, and pistil (Figure 5). RcDHN6 and RcLEA3-3 exhibited very high transcript abundance across multiple tissues, with peaks in prickle and stamen, whereas RcLEA1-1 and RcSMP1 were specifically enriched in stamen. RcLEA2-4, RcLEA2-2, and RcLEA6 exhibited high transcript abundance across multiple tissues at the same time. In Rosa beggeriana, RbDHN6 showed higher expression across multiple tissues, with peaks in leaf. In stem, expression was the most pronounced, with several genes reaching extremely high transcript levels, making this tissue the dominant site of RbLEA activity. In root, expression was moderate overall, with a few genes contributing prominently. In conclusion, the strongest RbLEA signals were concentrated in stem, leaf, and flower, while root and fruit showed more selective expression patterns.

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of LEA genes in different tissues of two rose species. (a) Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ (RcLEA). (b) Rosa beggeriana (RbLEA). The number in each square (heatmap cell) represents the FPKM. The color gradient from red to blue represents log2-transformed FPKM values, indicating high to low expression levels, respectively. Homologous genes between the two species are connected by colored lines.

Within the LEA1 group, RcLEA1-1 was highly expressed in reproductive tissues, whereas its homolog RbLEA1-1 showed extremely high expression in flower, indicating a conserved reproductive bias. In the LEA3 group, RcLEA3-3 exhibited very strong expression in reproductive tissues and root, while its homolog RbLEA3-3 was predominantly expressed in flower, reflecting redistribution of expression within reproductive organs. RcLEA2-1 was highly expressed in stamens, whereas its homolog RbLEA2-1 showed strong expression in stems and leaves, reflecting a marked shift in tissue specificity. In contrast, RcLEA6 was moderately expressed across multiple tissues, while its homolog RbLEA6 showed no detectable expression, suggesting loss of activity in R. beggeriana. Among the DHN genes, RcDHN3 was strongly expressed in root and reproductive tissues, whereas its homologs, RbDHN3-1 and RbDHN3-2, were highly expressed in stem and leaf, indicating a major tissue shift. RcDHN1 and RcDHN2 showed weak expression in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’, but their homologs, RbDHN1 and RbDHN2, were strongly expressed in fruit and stem, representing a gain of expression in R. beggeriana. By contrast, RcDHN6 and RbDHN6 both displayed very high expression across multiple tissues, reflecting a conserved high-expression pattern. Overall, these results demonstrate that, while some homologous pairs retained conserved expression, such as DHN6, many exhibited pronounced changes in both tissue specificity and transcript abundance, with R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ genes enriched in reproductive tissues and root and R. beggeriana homologs more strongly expressed in stem, leaf, and fruit.

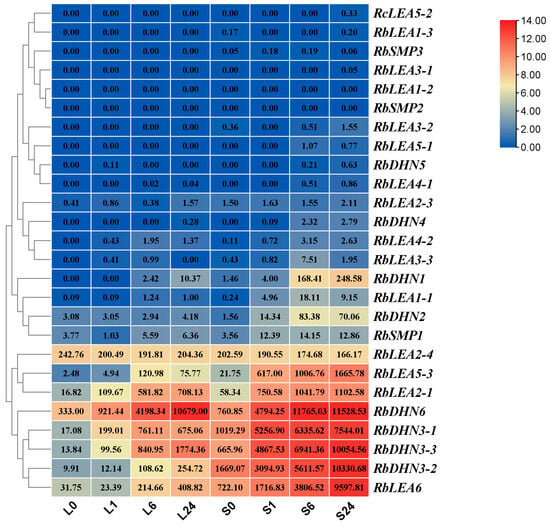

Twenty-six RbLEA genes were found in R. beggerian through transcriptome analysis of leaves and stems under chilling treatment (Figure 6 and Table S7). Over 10 genes were revealed with significance under the 23/18 °C treatment, including RbLEA6, RbLEA3-2, RbLEA3-3, RbLEA3-1, RbDHN6, RbLEA2-1, RbLEA5-3, RbSMP1, RbLEA2-3, RbLEA1-1, RbDHN2, and RbLEA2-4 in both tissue. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in R. beggeriana were identified from transcriptomes of leaves and stems following chilling treatment at 4 °C. In leaves, the expressions of RbLEA6, RbLEA3-2, RbLEA3-3, RbLEA3-1, RbDHN6, RbLEA2-1, and RbDHN1 were up-regulated under cold stress. The expression levels of RbLEA5-3 were up-regulated at early time points and then down-regulated. In stems, the expressions of RbLEA6, RbLEA3-2, RbLEA3-3, RbLEA3-1, RbDHN6, RbLEA2-1, RbLEA5-3, RbSMP1, RbDHN1, and RbDHN4 were up-regulated under cold stress. The expression levels of RbDHN1, RbDHN3, RbLEA5-3, and RbLEA6 were much higher in stems than in leaves. The expression levels of RbLEA3-1, RbLEA3-2, RbLEA5-1, and RbSMP1 fluctuated under cold stress. In addition, RbLEA1-2, RbLEA2-1, RbSMP1, and RbSMP2 showed comparable effects on growth temperature.

Figure 6.

Expression of RbLEA genes under cold stress. Heatmap depicting the expression dynamics of RbLEA genes in leaves (L) and stems (S) of R. beggeriana after chilling treatment at 4 °C for 0, 1, 6, and 24 h. The number in each square (heatmap cell) represents the FPKM. The color gradient from red to blue represents log2-transformed FPKM values, indicating high to low expression levels, respectively.

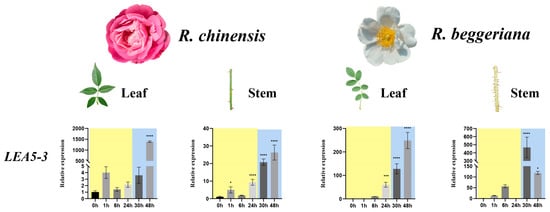

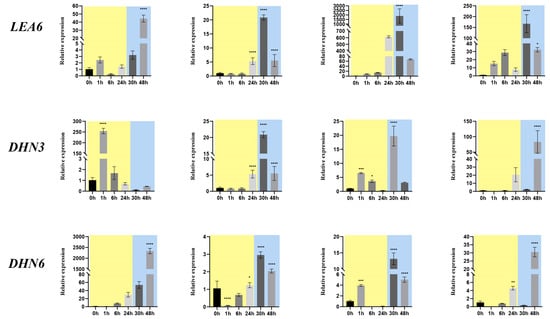

In R. beggeriana, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the majority of RbLEA genes exhibited expression profiles in both leaves and stems that were consistent with transcriptome data (Figure 7). In leaves, R. beggeriana showed much stronger and more sustained induction of LEA6, DHN3, and DHN6 than R. chinensis. In stems, the same trend was observed, with genes such as LEA5-3 and DHN6 up-regulated more strongly in R. beggeriana. Within species, R. beggeriana generally displayed higher expression in leaves than stems, while R. chinensis showed weaker and less tissue-differentiated responses. These results indicate that R. beggeriana activates LEA and DHN genes more robustly under cold stress, consistent with its greater cold tolerance.

Figure 7.

qRT-PCR profiling of LEA genes with elevated expression in Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ and Rosa beggeriana. Standard deviations are shown as error bars, and statistical significance is indicated by asterisks when comparing the untreated control (0 h) with samples exposed to cold at 4 °C for 1, 6, and 24 h or −4 °C for 6 and 24 h (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). Stages of 4 °C treatment are highlighted with a yellow background, whereas −4 °C treatment stages are marked with a blue background.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural and Evolutionary Features of LEA Genes and Their Significance in Rose

The late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family plays a central role in adaptation to abiotic stresses, especially in plants. LEA proteins are typically highly hydrophilic, glycine-rich, and contain intrinsically disordered regions, which enable them to stabilize proteins and membranes under dehydration and freezing conditions [47]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, genome-wide surveys revealed that LEA genes can be classified into multiple subfamilies, with LEA2 being the largest, and many members are strongly induced by abiotic stresses [48]. These comparative studies suggest that the expansion or contraction of specific LEA subfamilies reflects their central roles in stress adaptation.

In our study, we identified 23 LEA genes in Rosa chinensis, distributed across eight subfamilies, with DHNs forming the largest group. Rosa exhibits lineage-specific evolutionary features. Tandem duplications were detected in the LEA2 and LEA5 clusters, while whole-genome duplications contributed to the expansion of SMP and DHN genes. Such duplication events are likely the main drivers of functional redundancy and divergence. Although most LEA genes maintain conserved gene structures within subfamilies, DHNs display substantial structural variability, which may underlie their functional diversification. Compared with other Rosaceae species, R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ has been domesticated as an ornamental plant in temperate climates. These contrasting evolutionary trajectories likely shaped the structural diversification and regulatory potential of their LEA gene families. In this study, all the LEA genes showed Ka/Ks < 1, indicating that this family has undergone strong purifying selection and maintains high functional conservation. Compared to A. thaliana, the number of LEA genes in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ is lower, which may reflect the different whole-genome duplication histories among species and the differences in adaptation strategies for specific habitats.

In summary, the structural conservation of LEA proteins provides the biochemical foundation for stress protection, while lineage-specific duplication and divergence explain the unique features of Rosa. The predominance of DHNs, together with Rosa-specific duplication patterns, highlights the evolutionary innovations that may underlie the genus’s adaptation to diverse environments.

4.2. Upstream Transcription Factors, Tissue-Specific Expression, and Divergent Cold Responses

The transcriptional regulation of LEA genes is tightly controlled by upstream transcription factors. Promoter analyses revealed abundant ABRE, MYB, MYC, and DRE/CRT elements, indicating regulation via both ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling pathways [49]. Transcription factors from the MYB, NAC, WRKY, and AP2/ERF families are key regulators orchestrating cold stress responses [50].

Promoter analysis of RcLEA genes revealed abundant cis-acting elements correlated with abiotic stress and hormone signaling. Elements such as ABRE, MYB, DRE core, and LTR were frequently detected, suggesting responsiveness to abscisic acid, drought, and cold [51,52]. In our study, 14 types of cis-acting elements implicated in stress were identified, including ABRE, DRE core, ARE, F-box, MBS, GARE-motif, GATA-motif, LTR, MYB, MYC, STRE, TGA-element, W-box, and WRE3. Notably, RcLEA2-4, RcLEA3-3, and RcDHN6 harbored multiple ABRE and MYB motifs, consistent with their strong cold-induced expression [13]. The diversity of cis-acting elements in DHN promoters may contribute to their transcriptional flexibility, as also observed in other stress-inducible LEA genes [53]. Tandemly duplicated genes like RcLEA2-1 to RcLEA2-3 shared similar regulatory motifs, indicating conserved stress-responsive regulation. The cis-acting elements landscape supports the hypothesis that RcLEA genes are tightly regulated under cold stress, providing a molecular basis for their differential expression and potential roles in cold acclimation [54]. Some transcriptions have been proven to bind to the promotor of LEAs and enhance plants’ abiotic tolerance in other species. AmWRKY45 can combine with the promotor of AmDHN4 and enhance the low-temperature and drought tolerance in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus [30]. The interaction between ClWRKY61 and ClLEA55 enhances salt tolerance in watermelon [55]. In Anoectochilus roxburghii, a plasma membrane complex formed by ArWRKY57 and ArWRKY70 directly regulates the transcription of ArLEA5, enhancing drought tolerance in this plant [56]. The SAG21 promoter was targeted by 33 transcription factors belonging to nine families, notably ERF, WRKY, and NAC [57], the transcriptions we predicted may be involved in low-temperature tolerance in Rosa chinensis ‘Old blush’. We also predicted the ABRE and DRE; there is early research about these two transcription factors. Analyses of the mutant aba1, which lacks sufficient ABA, and abi1, which is insensitive to ABA, revealed that the RD29A promoter, containing multiple DREs and one ABR, is primarily induced via the ABA-independent pathway, whereas the RD29B promoter, harboring several ABREs, is predominantly controlled by ABA [58,59,60,61]. These two types of transcriptions make great impact on plants’ response to abiotic treatment. CRT/DRE binding factor is the CBFs binding site. Overexpression of CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3 activated expression of the COR6.6, COR15a, COR47, and COR78 genes [62,63,64].

Striking differences in tissue-specific expression were revealed by transcriptome data when comparing Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’ with Rosa beggeriana. For example, RcLEA2-1 was highly expressed in stamens, whereas its homolog RbLEA2-1 showed strong expression in stems and leaves, reflecting a marked shift in tissue specificity. RcLEA3-3 was abundant in reproductive tissues and roots, while its homolog RbLEA3-3 was enriched in flowers, indicating intra-organ divergence. RcDHN3 was strongly expressed in roots and reproductive tissues, but its homologs RbDHN3-1 and RbDHN3-2 were markedly expressed in stems and leaves, suggesting major tissue reallocation. In contrast, RcDHN6 and its homolog RbDHN6 both displayed very high expression across multiple tissues, representing a conserved high-expression pattern. qRT-PCR validation further confirmed that R. beggeriana activates LEA and DHN genes more strongly and persistently under cold stress. For example, RbDHN6 expression increased more than 10-fold within six hours of cold treatment and remained elevated at 24 h, whereas RcDHN6 induction was weaker and transient. RbLEA3-3 and RbLEA5-3 were robustly up-regulated in both leaves and stems, while RcLEA3-3 and RcLEA5-3 showed only moderate induction. These results indicate that R. beggeriana reallocates LEA and DHN expression to vegetative tissues under cold stress, which likely contributes to its superior freezing tolerance.

In other species, homologous genes of RcLEAs exhibit similar functions. MsLEA60, as the homolog of RcLEA1-1, responds significantly to drought, low temperature, and salt stress [65]. Under drought and 4 °C chilling treatment, its expression continuously increases, while, under salt stress, its expression first rises and then declines. In Malus domestica, the RcLEA1-1 homolog MdLEA60 enhances the resistance of transgenic tobacco to cold, drought, and saline-alkaline stress [66]. The RcLEA6 homolog BnaA.LEA6.a is cold-responsive at low temperatures, and studies have shown that its expression in cold-acclimated Brassica napus is higher than in non-acclimated controls, with the difference being more pronounced under −4 °C treatment [67]. Meanwhile, DHNs have also been shown in other species to enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stresses. In Hevea brasiliensis, overexpression of HbDHNs in Arabidopsis thaliana significantly improved tolerance to salt, drought, and osmotic stress. The function of DHNs is not limited to cold, drought, and salinity [68]. For example, OsDHN2 has been identified as a cadmium-responsive gene with the potential to enhance cadmium resistance in rice. This inspires further exploration of the diverse functions of LEA gene family members [69]. However, studies have also shown that homologous RcLEA genes may exhibit functional divergence in other species. In Caragana korshinskii, CkLEA3-3 shows low expression under 4 °C treatment, and CkDHN3 shows no significant expression [70]. Similarly, the RcLEA3-3 homologs CsLEA10 and CsLEA7 in Camellia sinensis do not exhibit significant expression under cold stress [71]. These findings suggest that the functions of LEA gene family members are species-specific. Research on abiotic stress in Rosa extends beyond low-temperature stress. In molecular breeding for thermotolerance in R. chinensis, RcTPS7b functions as a signaling regulator that enhances heat adaptation by activating the heat shock signaling pathway (HSF/HSP) and maintaining redox homeostasis [72]. In Rosa rugosa, saline-alkali stress modulates the transcription factor MYB5, which affects the expression of downstream genes ANR and TPS31, thereby dynamically regulating the accumulation of proanthocyanidins and sesquiterpenes in rose petals and improving plant adaptation to salt stress. Therefore, RcLEAs may also play crucial roles in other types of abiotic stress [73].

In summary, these findings suggest that Rosa LEA regulation involves both conserved and divergent elements. These differences are likely mediated by variation in promoter architecture and transcription factor binding, particularly involving MYB, NAC, WRKY, and CBF families. Understanding these regulatory networks provides a foundation for breeding cold-tolerant roses by introgressing R. beggeriana alleles into cultivated backgrounds.

5. Conclusions

In Rosa chinensis ‘Old Blush’, 23 LEA genes were identified and classified into eight subfamilies, with chromosomal mapping revealing their distribution across six chromosomes and partial gene clustering. All RcLEA proteins contained conserved LEA motifs and exhibited simple gene structures with few introns. Promoter analysis indicated that RcLEA genes harbor abundant cis-elements associated with abiotic stress and hormone responses. Comparative expression analysis and qRT-PCR validation showed that several LEA homologs, including DHN3, displayed strong cold-responsive expression patterns, suggesting their potential as candidate genes for future functional studies. This study also provides a genome-wide framework for understanding LEA gene organization and cold-responsive expression in roses. Future work involving transgenic or gene-editing approaches will be necessary to clarify the specific contributions of LEA genes to cold tolerance and to evaluate their potential utility in breeding cold-resilient rose cultivars.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12020136/s1, Table S1: Identification and characterization of LEAs in R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’; Table S2: DNA sequences of 23 RcLEA genes; Table S3: Protein sequences of 74 LEA proteins from two species; Figure S1: Motif analysis of RcLEAs; Figure S2: Conserved analysis of RcLEAs; Table S4: Ka/Ks ratios of RcLEA genes; Table S5: Cis-acting elements in the promoters of 23 RcLEA genes; Table S6: RNA-seq data of RcLEA genes in different tissues (PRJNA546486); Table S7: RNA-seq data of RbLEA genes in different tissue; Table S8: RNA-seq data of RbLEA genes in leaves and stems under cold treatment; Table S9: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, S.Y.; writing—original draft, L.L. and H.L.; software, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and data curation, L.L. and H.L.; validation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., S.W. and H.S.; resources, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, S.Y., Y.K., R.J., X.Z., J.D., L.X. and H.G. All authors have examined the manuscript and agree with its published form. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program (2024YFD1200503) and the Project of Northern Agriculture and Livestock Husbandry Technical Innovation Center, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2022RC-Hohhot Industrial Technology Innovation Research Institute-3).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Mingao Duan and Xiaofei Wang in the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Linbo Xu and Junjie Duan were employed by the company Inner Mongolia Zhongnong North Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LEA | Late Embryogenesis Abundant proteins |

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| DHN | Dehydrin |

| SMP | Seed maturation proteins |

| NJ | Neighbor-Joining |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads |

| CDS | Coding Sequence |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| ABRE | ABA-Responsive Element |

| ARE | AU-Rich Element |

| DRE | Dehydration-Responsive Element/Drought-Responsive Element |

| LTR | Low Temperature Responsive element |

| MBS | MYB Binding Site |

| MYB | Myeloblastosis oncogene |

| MYC | Myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| STRE | Stress-Responsive Element |

| WRE3 | Wound-Responsive Element 3 |

| RNA-seq | RNA Sequencing |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

References

- Gechev, T.; Petrov, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Abiotic Stress in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Christov, N.K.; Tsuda, S.; Imai, R. Identification of a Novel LEA Protein Involved in Freezing Tolerance in Wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-A.; Cho, S.K.; Kim, J.E.; Chung, H.S.; Hong, J.-P.; Hwang, B.; Hong, C.B.; Kim, W.T. Isolation of cDNAs differentially expressed in response to drought stress and characterization of the Ca-LEAL1 gene encoding a new family of atypical LEA-like protein homologue in hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L. cv. Pukang). Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegzouti, H.; Jones, B.; Marty, C.; Lelièvre, J.-M.; Latché, A.; Pech, J.-C.; Bouzayen, M. Er5, a tomato cDNA encoding an ethylene-responsive LEA-like protein: Characterization and expression in response to drought, ABA and wounding. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 35, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galau, G.A.; Hughes, D.W.; Dure, L., 3rd. Abscisic acid induction of cloned cotton late embryogenesis-abundant (Lea) mRNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 1986, 7, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dure, L., 3rd; Greenway, S.C.; Galau, G.A. Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination: Changing messenger ribonucleic acid populations as shown by in vitro and in vivo protein synthesis. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 4162–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Hembram, P. An Overview of LEA Genes and Their Importance in Combating Abiotic Stress in Rice. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2024, 43, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, J. Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) Gene Family in Maize: Identification, Evolution, and Expression Profiles. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2016, 34, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Dong, L.; Ye, H.; Valliyodan, B.; Nguyen, H.T.; Song, L. The Late Embryogenesis Abundant Proteins in Soybean: Identification, Expression Analysis, and the Roles of GmLEA4_19 in Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chi, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, T.; Han, L.; Li, L.; Pei, X.; Long, Y. Genome-wide identification and functional characterization of LEA genes during seed development process in linseed flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zheng, J.; Xu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Gan, J.; Raboanatahiry, N.; Yin, Y.; Li, M. Genome-wide identification, structural analysis and new insights into late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family formation pattern in Brassica napus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database: Towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D279–D285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xiao, D.; Wang, X.; Zhan, J.; Wang, A.; He, L. Genome-wide identification, evolutionary and expression analyses of LEA gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; She, M.; Zhao, M.; Yu, H.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genome-wide analysis and functional validation reveal the role of late embryogenesis abundant genes in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) fruit ripening. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, B.; Yang, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhuo, R.; Yao, X. The LEA2 gene sub-family: Characterization, evolution, and potential functions in Camellia oleifera seed development and stress response. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 322, 112392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, S.; Ma, Z.; Wang, D.; Long, D.; Niu, Y. Overexpression of GiLEA5-2.1, a late embryogenesis abundant gene LEA3 from Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat., enhances the drought and salt stress tolerance of transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana). Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, L.; Iqbal, S.; Rasheed, S.; Munir, H.; Niazi, A.K.; Khan, R.S.A. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Characterization of LEA4-5 Genes in Response to Drought Stress in Brassica Species. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 4678–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska, B.; Razak, N.; Shaw, D.S.; Plumb, W.; Van De Slijke, E.; Stephens, J.; De Jaeger, G.; Murcha, M.W.; Foyer, C.H. Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA)5 Regulates Translation in Mitochondria and Chloroplasts to Enhance Growth and Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 875799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Mosso, I.A.; Diaz-Ardila, H.N.; Garciarrubio, A.; Kumara, U.; Rendon-Luna, D.F.; Nava-Ramirez, T.B.; Boothby, T.C.; Reyes, J.L.; Covarrubias, A.A. A Group 6 LEA Protein Plays Key Roles in Tolerance to Water Deficit, and in Maintaining the Glassy State and Longevity of Seeds. Plant Cell Env. 2025, 48, 6874–6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, A. Analysis of Cyperus esculentus SMP family genes reveals lineage-specific evolution and seed desiccation-like transcript accumulation during tuber maturation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chu, T.; Tian, H.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Hu, T. Identification and Functional Validation of the PeDHN Gene Family in Moso Bamboo. Plants 2025, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Kang, K.; Gan, L.; Ning, S.; Xiong, J.; Song, S.; Xi, L.; Lai, S.; Yin, Y.; Gu, J.; et al. Drought-responsive genes, late embryogenesis abundant group3 (LEA3) and vicinal oxygen chelate, function in lipid accumulation in Brassica napus and Arabidopsis mainly via enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and reducing ROS. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 2123–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L. The functional analysis of a wheat group 3 late embryogenesis abundant protein in Escherichia coli and Arabidopsis under abiotic stresses. Plant Signal Behav. 2019, 14, 1667207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Qiu, W.; Guan, S.; et al. Overexpression of the GmPM35 Gene Significantly Enhances Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Soybean. Agronomy 2025, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, R. CaDHN5, a Dehydrin Gene from Pepper, Plays an Important Role in Salt and Osmotic Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, C.; Dong, K. Overexpression of Medicago sativa LEA4-4 can improve the salt, drought, and oxidation resistance of transgenic Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, G.; Cheng, X.; Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Chi, W.; Li, J.; Dai, Z.; Wang, C.; Duan, E.; et al. The superior allele LEA12OR in wild rice enhances salt tolerance and yield. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Fan, X.; Wang, C.; Jiao, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Guan, S.; Liu, S. Overexpression of ZmDHN15 Enhances Cold Tolerance in Yeast and Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, G.; Elias, G.K.; Li, S.; Liang, Z. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Grapevine LEA Gene Family in Response to Osmotic and Cold Stress Reveals a Key Role for VamDHN3. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F. AmDHN4, a winter accumulated SKn-type dehydrin from Ammopiptanthus mongolicus, and regulated by AmWRKY45, enhances the tolerance of Arabidopsis to low temperature and osmotic stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wuyun, T.-n.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Tian, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Genome-wide and functional analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes during dormancy and sprouting periods of kernel consumption apricots (P. armeniaca L. × P. sibirica L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 133245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Balasubramaniam, L.M.; Priya, M.D.L.; Varun, B.R.; Sekar, R. Exploring the potential of Rosa chinensis, Rosa cymosa, and Rosa indica in oral disease prevention: A multifaceted approach. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2025, 29, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Ge, H. Studies on the use of rosa beggeriana schrenk as a source of cold resistance in rose breeding. Acta Hortic. Sin. 1989, 16, 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Guo, N.; Fu, L.; Ge, H. Phenotypic Diversity of Rosa beggeriana Populations in Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2014, 41, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Jia, R.; Zhao, X.; Ge, H. Analysis of Freezing Tolerances and Its Physiological Differences of Two Rosa Species During the Overwintering. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2017, 44, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Jia, R.; Zhao, X.; He, L.; Meng, W.; Ge, H. Physiological and Proteomics Analysis on Freezing Tolerance of Rosa beggeriana Branches during Overwintering. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2020, 21, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, N.; Liu, H.; Ge, H. AFLP-based Genetic Diversity of Rosa beggeriana Populations in Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2015, 42, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, O.; Gouzy, J.; Just, J.; Badouin, H.; Verdenaud, M.; Lemainque, A.; Vergne, P.; Moja, S.; Choisne, N.; Pont, C.; et al. The Rosa genome provides new insights into the domestication of modern roses. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Williams, N.; Misleh, C.; Li, W.W. MEME: Discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W369–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higo, K.; Ugawa, Y.; Iwamoto, M.; Higo, H. PLACE: A database of plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: Calculating Selective Pressure on Coding and Non-coding Sequences. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhao, T.; Cheng, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q. Dissecting the Genome-Wide Evolution and Function of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Family in Rosa chinensis. Genes 2019, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artur, M.A.S.; Zhao, T.; Ligterink, W.; Schranz, E.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Van De Peer, Y. Dissecting the Genomic Diversification of Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) Protein Gene Families in Plants. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundertmark, M.; Hincha, D.K. LEA (Late Embryogenesis Abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, J.-K. Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.A.; Azzeme, A.M.; Yousefi, K. Fine-Tuning Cold Stress Response Through Regulated Cellular Abundance and Mechanistic Actions of Transcription Factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 850216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheshadri, S.A.; Nishanth, M.J.; Simon, B. Stress-Mediated cis-Element Transcription Factor Interactions Interconnecting Primary and Specialized Metabolism in planta. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; He, M.; Zhu, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Singer, S.D.; Wang, Y. Identification of the dehydrin gene family from grapevine species and analysis of their responsiveness to various forms of abiotic and biotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Teng, Y.; Cen, Q.; Fang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xue, D. Genome-Wide Identification of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor and Expression Analysis under Abiotic Stress in Rice. Plants 2022, 11, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Xuan, C.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Feng, M.; Yuan, L.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. The transcription factor ClWRKY61 interacts with ClLEA55 to enhance salt tolerance in watermelon. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Lv, A.; Huang, Y.; Shao, Q.; Lu, C.; Sun, J.; Zhao, C. The ArWRKY57-ArWRKY70-ArLEA5 module: Key regulators of drought tolerance in Anoectochilus roxburghii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 328, 147596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.V.; Ransom, E.; Nayakoti, S.; Wilding, B.; Mohd Salleh, F.; Gržina, I.; Erber, L.; Tse, C.; Hill, C.; Polanski, K.; et al. Expression of the Arabidopsis redox-related LEA protein, SAG21 is regulated by ERF, NAC and WRKY transcription factors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koornneef, M.; Jorna, M.L.; Brinkhorst-van der Swan, D.L.C.; Karssen, C.M. The isolation of abscisic acid (ABA) deficient mutants by selection of induced revertants in non-germinating gibberellin sensitive lines of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) heynh. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1982, 61, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koornneef, M.; Reuling, G.; Karssen, C.M. The isolation and characterization of abscisic acid-insensitive mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant. 1984, 61, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Satoh, R.; Maruyama, K.; Parvez, M.M.; Seki, M.; Hiratsu, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AREB1 Is a Transcription Activator of Novel ABRE-Dependent ABA Signaling That Enhances Drought Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3470–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, Y.S.J.P.C. A Novel cis-Acting Element in an Arabidopsis Gene Is Involved in Responsiveness to Drought, Low-Temperature, or High-Salt Stress. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Jaglo-Ottosen, K.R.; Gilmour, S.J.; Zarka, D.G.; Schabenberger, O.; Thomashow, M.F. Arabidopsis CBF1 Overexpression Induces COR Genes and Enhances Freezing Tolerance. Science 1998, 280, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, S.J.; Sebolt, A.M.; Salazar, M.P.; Everard, J.D.; Thomashow, M.F. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis CBF3 transcriptional activator mimics multiple biochemical changes associated with cold acclimation. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Abe, H.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low- temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B. Abiotic stress-regulated LEA gene mediates the response to drought, salinity, and cold stress in Medicago sativa L. Plant Cell Physiol. 2025, 66, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B. Comprehensive identification of LEA protein family genes and functional analysis of MdLEA60 involved in abiotic stress responses in apple (Malus domestica). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Xia, X.; Chen, X.; Qian, L.; Xiong, X.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of LEA gene family reveals a positive role of BnaA.LEA6.a in freezing tolerance in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiang, X.; Geng, M.; You, Q.; Huang, X. Effect of HbDHN1 and HbDHN2 Genes on Abiotic Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.-J.; Wang, M.-T.; Du, Z.-Y.; Li, J.-H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.-Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, M.; Yang, J.; et al. Bioinformatic and functional analysis of OsDHN2 under cadmium stress. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Yue, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Li, G. Identification of the LEA family members from Caragana korshinskii (Fabaceae) and functional characterization of CkLEA2-3 in response to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis. Braz. J. Bot. 2019, 42, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pedrosa, A.M.; Martins, C.d.P.S.; Gonçalves, L.P.; Costa, M.G.C. Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) Constitutes a Large and Diverse Family of Proteins Involved in Development and Abiotic Stress Responses in Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osb.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Du, B.Q.; Bai, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Du, J.Z.; Wu, X.W.; Yan, L.P.; Bai, Y.; Chai, G.H. Saline-alkali stress affects the accumulation of proanthocyanidins and sesquiterpenoids via the MYB5-ANR/TPS31 cascades in the rose petals. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-W.; Lin, X.-L.; Ding, Q.-H.; Du, J.-L.; Dong, X.-K.; Liu, A.; Liu, X.-D.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Chen, H.-X.; Chen, J.-R.; et al. Functional identification of trehalose and a trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene involved in heat stress tolerance of rose. Ornam. Plant Res. 2025, 5, e039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.