Abstract

Lentinula edodes (shiitake) is a major edible and medicinal mushroom and a key component of the horticultural mushroom industry in East Asia. During April–June 2024 cropping season, a widespread blue mold outbreak was observed on bag-cultivated shiitake in Xixia County, Henan Province, China. Affected cultivation rooms showed extensive blue-green sporulation on the exposed surfaces of substrate blocks and on developing and mature fruiting bodies, leading to rapid loss of marketability. To clarify the etiology of this disease, we coupled field surveys with morphological, molecular, and pathogenicity analyses. Fifty-five Penicillium isolates were obtained from symptomatic cultivation bags. Three representative isolates (LE06, LE15, and LE26) were characterized in detail. Colonies on PDA produced velutinous to floccose mycelia with blue-green conidial masses and terverticillate penicilli bearing smooth-walled, globose conidia. Sequencing of four loci—the internal transcribed spacer (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2), β-tubulin (benA), calmodulin gene (CaM), and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2)—followed by multilocus phylogenetic analysis placed all three isolates in a well-supported clade with the ex-type CBS 227.28 of Penicillium bialowiezense. Inoculation of healthy shiitake cultivation bags with conidial suspensions (1 × 106 conidia mL−1) reproduced typical blue mold symptoms on substrate surfaces and fruiting bodies within 40 days post inoculation, whereas mock-inoculated controls remained symptomless. The pathogen was consistently reisolated from diseased tissues and showed identical ITS and benA sequences to the inoculated strains, thereby fulfilling Koch’s postulates. This is the first confirmed report of P. bialowiezense causing blue mold on shiitake, and it expands the known host range of this species. Our findings highlight the vulnerability of bag cultivation systems to airborne Penicillium contaminants and underscore the need for improved hygiene, environmental management, and targeted diagnostics in commercial shiitake production.

1. Introduction

Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) is among the world’s most extensively cultivated edible–medicinal mushrooms, with China contributing the majority of production. China alone accounts for more than 80% of global output, driven by extensive cultivation in central and eastern provinces [1,2,3]. Intensive cultivation creates conditions that favor opportunistic fungi and bacteria, leading to measurable yield and quality losses [4,5]. Among these, Trichoderma green mold outbreaks—predominantly attributed to Trichoderma spp.—have drawn considerable attention due to major yield penalties and quality deterioration [6,7]. By contrast, in shiitake cultivation handbooks, “blue mold” is commonly described at the genus level as Penicillium spp., whereas only limited studies have examined species-level Penicillium contamination during the spawn run stage [8,9].

Located on the southern foothills of the Funiu Mountains in Henan Province, Xixia County is characterized by extensive low- to mid-elevation mountain ranges. The diurnal temperature range and atmospheric humidity create natural conditions highly conducive to the growth of L. edodes (shiitake). Beginning in the 1990s, the county vigorously promoted cultivation of shiitake and has since developed into the largest shiitake production base in northern China [10,11,12]. During early spring of 2024, producers in Xixia County reported widespread blue discoloration, sporulation, and soft rot on shiitake fruiting bodies, with rapid spread under warm and humid conditions common to seasonal production rooms. Given the direct impact on marketability and food safety, there was an urgent need to identify the causal agent and delineate its epidemiological relevance. Accurate species level identification within Penicillium requires integration of cardinal phenotypes, micromorphology (conidiophore branching patterns and stipe morphology), and a multilocus molecular approach encompassing ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and protein coding markers including β-tubulin (benA), calmodulin gene (CaM), and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2).

Penicillium bialowiezense (section Brevicompacta) is a member of the Penicillium characterized from forest substrates and occasionally implicated in blue mold of certain fruits [13,14,15,16]. In addition to causing postharvest spoilage, some Penicillium species are able to synthesize bioactive secondary metabolites with potential food-safety implications. P. bialowiezense, a close relative of the well-known mycophenolic-acid producer Penicillium brevicompactum, has been reported to produce mycophenolic acid (MPA), and genomic analyses have identified the corresponding MPA biosynthetic gene cluster in P. bialowiezense with chemical confirmation of MPA production in culture [17,18]. MPA is a potent inhibitor of inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) and is used clinically as the active ingredient of immunosuppressive drugs (mycophenolate formulations), indicating strong bioactivity; therefore, contamination by MPA-producing Penicillium spp. may represent an additional concern beyond quality losses [19,20]. Here we present morphological, molecular, and pathogenicity evidence that P. bialowiezense is the etiological agent of shiitake blue mold outbreaks in China. Specifically, we document field symptomatology and disease incidence; isolate and characterize the pathogen; infer its phylogenetic placement using a concatenated dataset (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, benA, CaM, rpb2) with representative type sequences; and demonstrate pathogenicity through controlled inoculations followed by reisolation and molecular confirmation. The findings establish a foundation for epidemiological studies and practical disease management in mushroom farms.

Although green mold caused by Trichoderma spp. is widely recognized in edible-mushroom production [6,7,8], comparatively little is known about the spectrum and epidemiology of blue molds caused by Penicillium in shiitake. We therefore asked whether Penicillium spp. are etiological agents of surface molds and fruiting impairment on L. edodes in Xixia. Our a priori hypotheses were that symptomatic cultivation bags would harbor a single, consistently re-isolated Penicillium species identifiable by multilocus phylogenetics, and that disease signs would initiate on exposed substrate surfaces and subsequently affect primordia under high humidity. This focus is motivated by extensive evidence that Penicillium species are dominant blue-mold agents in postharvest fruit (e.g., Penicillium expansum on pome fruit; Penicillium italicum on citrus) with well-characterized pathogenicity and resistance issues [21,22,23,24,25,26,27], alongside reports that Penicillium can occur as a contaminant or competitor in mushroom production albeit at lower frequency than Trichoderma [5]. By resolving the causal agent and framing system-specific drivers, this study aims to refine surveillance targets and management priorities for shiitake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Surveys and Sample Collection

Surveys were conducted from April to June 2024 across shiitake farms in Xixia County, Henan Province, China (33.34° N, 111.51° E). Environmental metadata (daily temperature, relative humidity) were recorded for each survey site. We summarized daily temperature, relative humidity, and cultivar. Disease incidence was estimated at the farm level as the proportion of production rooms exhibiting characteristic blue mold symptoms. Fruiting bodies displaying light blue patches progressing to dense blue sporulation and eventual black soft rot were collected into sterile bags, transported on ice, and processed within 24 h. A minimum of five symptomatic fruiting bodies per farm were sampled. Representative specimens were documented photographically. The disease severity index (DSI) was calculated according to a five-grade scale (0 = healthy, 1 = <5% fruiting body area affected, 2 = 6–10%, 3 = 11–25%, and 4 = >25%). DSI (%) = Σ (ni × si)/(N × sₘₐₓ) × 100, where nᵢ is the number of fruiting bodies in severity class sᵢ, N is the total number of fruiting bodies, and sₘₐₓ = 4. Group differences were analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 31) using one-way ANOVA (α = 0.05); 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported.

2.2. Pathogen Isolation and Purification

Surface tissues (5 × 5 mm) from lesion margins were excised, briefly rinsed under running tap water, surface sterilized in 75% ethanol (30 s), and rinsed thrice with sterile distilled water. Tissues were blotted dry and triturated in sterile water to obtain conidial suspensions. Serial dilutions were plated onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium supplemented with streptomycin (50 μg mL−1) to suppress bacterial contaminants. Plates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark for 7 d in a thermostatic incubator (Model BPH-9272, Yiheng Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China). Emerging monocolored colonies with Penicillium-like features were sub-cultured and purified by single spore isolation: a dilute conidial suspension was spread on 2% water agar; single germinating conidia were picked under a stereomicroscope and transferred to fresh PDA.

2.3. Cultural and Microscopic Characterization

For cultural characters, 5 mm diameter plugs from the colony margin were placed on PDA plates and incubated at 25 °C for 7 d; colony diameter was recorded for each isolate (n = 3 plates per isolate). Colony morphology (color, texture, exudate, soluble pigment) was noted. Micromorphology was assessed from slide cultures prepared on PDA. After 3–5 d, conidiophores and conidia were examined using a compound microscope (Model BM2100POL, Jiangnan novel optics, Nanjing, China) at ≥400× magnification. At least 100 conidia were measured per isolate. Diagnostic features (e.g., terverticillate branching; smooth walled conidia) were recorded. Photomicrographs were captured with a digital camera attached to the microscope. For the characterization of the conidial phase, morphological terminology and identification were based on specialized taxonomic keys for Penicillium [28,29], and the assignment to Penicillium section Brevicompacta followed Frisvad et al. [30].

2.4. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from mycelium scraped from 3-day-old cultures grown on PDA using a CTAB protocol. The quality and concentration of genomic DNA were evaluated prior to PCR using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to record A260/280 and A260/230 ratios, and DNA integrity was checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. For multilocus sequencing, we selected three representative isolates to capture geographic and production-site variation. These three isolates (LE-06, LE-15, LE-26) were chosen from different townships and independent farms. For each isolate, four loci were amplified: ITS (primers ITS1/ITS4), benA (β-tubulin; primers Bt2a/Bt2b), CaM (primers CMD5/CMD6), and rpb2 (primers 5F/7CR). PCR reactions (25 µL) contained 1× buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 µM of each primer, 1 U Taq polymerase, and ~20 ng template DNA. Cycling parameters followed original primer publications with minor optimization (annealing 52–58 °C depending on locus). PCR amplifications were performed using a thermal cycler (T100 Thermal Cycler, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under the conditions described above. PCR amplicons were purified and bidirectionally Sanger sequenced by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) using an Applied Biosystems™ 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Primer sequences and references are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primer sequences for each locus of Penicillium sp. in this study.

2.5. Sequence Submission and Dataset Assembly

Consensus sequences of the four loci for each representative isolate were deposited in GenBank (accessions to be provided in Table 2). Reference sequences of ex-type or authentic strains for Penicillium species within the relevant sections were retrieved from public databases to construct a comparative dataset.

Table 2.

Isolates and GenBank accession numbers used for phylogenetic analyses in this study.

2.6. Phylogenetic Analyses

Sequences were aligned using MAFFT (version 7.526) with default gap penalties and manually adjusted to maintain positional homology. Loci were concatenated (ITS–benA–CaM–rpb2) after checking for topological congruence. Phylogenetic inference was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) method in MEGA (version 12) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branches with bootstrap support ≥ 70% were considered well supported for species level resolution in the context of ML analysis.

2.7. Pathogenicity Tests and Reisolation

Healthy, disease-free cultivation bags of shiitake produced by a commercial farm were obtained for pathogenicity tests. For each of the three representative Penicillium isolates, a conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia mL−1, quantified with a hemocytometer) was prepared in sterile distilled water with 0.01% Tween-20. For each isolate, 3 cultivation bags were sprayed to runoff over the exposed surface and directly into the bags using a sterile atomizer. Mock controls (n = 3) received sterile carrier without conidia. All bags were maintained in a controlled environment simulating standard shiitake fruiting conditions: 18–22 °C, 85–95% RH, and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with intermittent ventilation. Symptom development was monitored daily for 40 d post inoculation (dpi). From symptomatic tissues, the pathogen was reisolated and identified morphologically and by sequencing of ITS and benA.

3. Results

3.1. Disease Occurrence and Symptomatology in the Field

During the April–June fruiting period of L. edodes cultivation in Xixia County, greenhouses are typically managed at a mean air temperature of approximately 15–22 °C and a relative humidity of 80–90%; humidity is often held at 85–90% during primordium formation and reduced to 75–85% during cap expansion, with additional shading to keep peak June temperatures below 28 °C. Disease incidence ranged from 35% to 40%. The mean DSI (%) values across survey plots ranged from 21% to 38%, indicating moderate to severe disease pressure. Early symptoms consisted of small, light blue patches on pilei and stipes. Within days, lesions expanded and coalesced, with prolific blue conidiation and powdery masses covering affected surfaces (Figure 1). Progressive colonization led to tissue softening, water soaking, and secondary darkening culminating in black rot (Figure 1d). Symptomatic fruiting bodies rapidly lost marketability.

Figure 1.

Disease symptoms of blue mold on shiitake. (a,b) blue, powdery colonies initially on the exposed surfaces of the cultivation substrate and subsequently on shiitake; the red arrow in panel (a) points to uninfected shiitake mushroom fruiting bodies. (c,d) sporulating patches on fruiting bodies showing water-soaked to brown lesions overrun by blue conidial masses. Photographs taken under production conditions in Xixia.

3.2. Morphological Identification of Penicillium Isolates

In our sampled fruiting bodies and substrate surfaces, the symptomatic areas were almost entirely covered by dense blue sporulation typical of Penicillium. Following isolation and purification, 55 isolates were obtained from 30 independently sampled fruiting bodies from different farms. All 55 cultures obtained from these samples were identified as Penicillium spp., and no other fungal genera were recovered under our isolation conditions. Therefore, Penicillium was the predominant fungus in this disease.

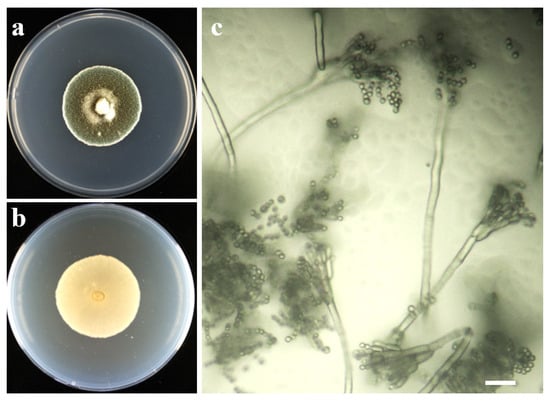

On PDA at 25 °C for 7 d, colonies were circular, flat to low convex, and velvety, with abundant blue conidial masses; reverse was pale to slightly yellowish. Colony diameters ranged from 19 to 22 mm (mean ± SD: 20.7 ± 1.1 mm), with no significant differences among isolates (ANOVA, p > 0.05). No diffusible pigments were observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Morphology of the causal Penicillium sp. of isolate LE06. (a) colony on PDA, obverse, 7 d at 25 °C; (b) reverse on PDA; (c) conidiophores with ampulliform to subcylindrical phialides; smooth-walled, globose conidia in chains. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Slide cultures revealed typical Penicillium conidiophores that were terverticillate with smooth stipes and ramification into metulae bearing phialides. Phialides were ampulliform to cylindrical, 6–9 µm long. Conidia were ellipsoidal to subglobose, smooth walled, hyaline in mass, measuring (1.8–3.0) ± 0.46 µm in width by (1.9–4.1) ± 0.81 µm in length (n = 100), arranged in unbranched chains. These features were consistent across all isolates examined and collectively aligned with the circumscription of Penicillium sp.

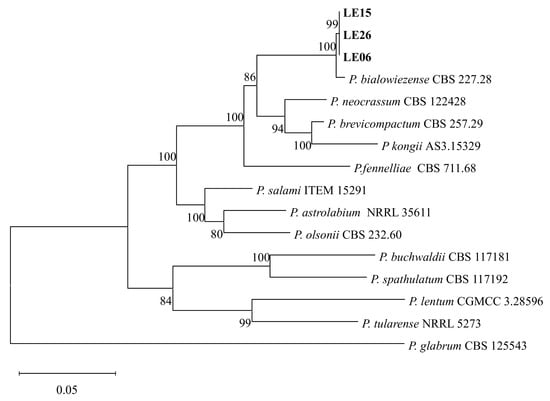

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

For each isolate, four genetic loci—ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, benA, CaM, and rpb2—were successfully amplified, sequenced, and deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers PP908489, PP908495, PP908496 (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2), PP963648–PP963650 (benA), PP960544–PP960546 (CaM), and PP919460–PP919462 (rpb2).

Pairwise BLASTn (version 2.17.0) searches supported assignment of all three isolates to P. bialowiezense (Table 3). For isolate LE06, ITS (PP908489) and rpb2 (PP919460) were 100% identical to P. bialowiezense CBS 227.28 (516/516 bp) and strain 5306 (846/846 bp), respectively, while benA (PP963648) and CaM (PP960544) showed 99% identity to KBP:F-430 (429/430 bp) and AS3.15316 (398/399 bp). Collectively, the multilocus identities (ITS 100%; benA/CaM 99–100%; rpb2 98–100%) unequivocally place LE06, LE15, and LE26 within P. bialowiezense.

Table 3.

BLAST (version 2.17.0) results of locus sequences of the three strains isolated.

The concatenated alignment comprised about 2200 positions after manual trimming. ML analysis strongly supported the placement of our isolates within the P. bialowiezense clade together with the ex type strain CBS 227.28, distinct from closely related taxa in the section Brevicompacta (Figure 3). Bootstrap support for the focal clade was 100%.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic trees based on maximum likelihood (ML) analysis of a combined dataset of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, benA, CaM, and rpb2 gene sequences of Penicillium species. Bootstrap values are presented above the branches. Bold indicates the strains described in this study. The scale bar indicates 0.05 changes. P. glabrum (CBS 125543) was selected as the outgroup.

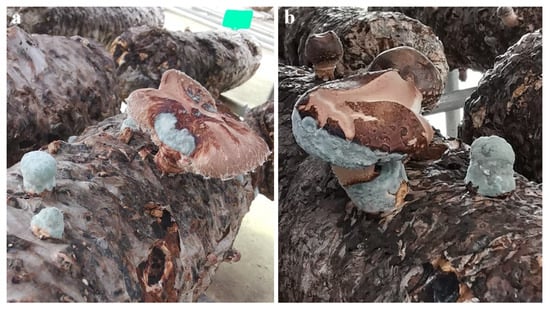

3.4. Pathogenicity and Reisolation

At 40 dpi, all inoculated bags developed typical blue mold symptoms on the fruiting bodies, with diffuse conidial mats that matched field observations; where primordia or fruiting bodies emerged, lesions were similarly overrun by blue conidia (Figure 4). Mock-inoculated controls (n = 3) remained symptomless throughout the 40-day period. Penicillium was consistently re-isolated from symptomatic tissues and re-identified as P. bialowiezense based on cultural and microscopic characters, with ITS/benA sequences identical to the inoculum (100% identity), thereby fulfilling Koch’s postulates. No Penicillium was recovered from controls, which maintained normal L. edodes mycelial vigor and fruiting. The assay was performed twice (per isolate, 3 bags; three isolates total), and outcomes were concordant across all isolates and experimental runs.

Figure 4.

Pathogenicity test on shiitake cultivation bags (Koch’s postulates). (a,b) Cultivation bags sprayed to runoff with a conidial suspension developed diffuse blue colonies on fruiting bodies.

4. Discussion

This study establishes P. bialowiezense as a causal agent of blue mold on shiitake and distinguishes it from the more frequently reported Trichoderma complex in edible-mushroom production, thereby expanding the recognized pathogen spectrum of L. edodes. Species level delineation within Penicillium species is challenging due to morphological convergence and plasticity under culture conditions. While genus level recognition is straightforward based on conidiophore architecture, species identification benefits from sequencing multiple loci that provide higher resolution than ITS alone. Our concatenated ITS–benA–CaM–rpb2 dataset afforded placement with CBS 227.28 and support separating our isolates from sympatric Penicillium species potentially present in mushroom houses.

Green mold epidemics in shiitake and other mushrooms are well documented for Trichoderma spp., where aggressive mycoparasitism and rapid sporulation devastate crops. By contrast, blue molds attributable to Penicillium spp. have been underrecognized or treated as generic contaminants. In addition to Trichoderma “green mold,” several other fungal diseases have been reported on Lentinula edodes, notably yeast-like Hyphozyma (synanamorph) [36], cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum [37], and cases associated with Stemonaria longa and Physarella oblonga [38,39]. Most of these records arise from bag-based cultivation during substrate preparation, spawn run, or early fruiting in enclosed rooms, where steam-sterilized media, filtered air, and dense cropping favor contamination dynamics distinct from those in outdoor log systems. Consistent with these reports, the Penicillium outbreaks documented here occurred in bag-cultivated shiitake production units and were most conspicuous on the exposed substrate surfaces and fruiting bodies during the cropping stage. We therefore infer that the cultivation system itself—substrate type and sterilization, immersion practices, microclimatic control, and sanitation regimes—acts as a key ecological filter shaping pathogen spectra.

Bag cultivation relies on steam-sterilized or autoclaved sawdust–nutrient substrates enclosed in polypropylene bags with defined air exchange, whereas log cultivation uses non-sterilized hardwood bolts with intact bark and native endophytes. In bag systems, substrate sterilization removes much of the indigenous microbial community, potentially opening ecological niches for fast-growing airborne fungi such as Penicillium once conidia are introduced via contaminated air, tools, or water. Repeated soaking, high relative humidity (≈85–95%), and dense stacking of bags in enclosed rooms can create persistently wet surfaces and reduced air movement around the fruiting windows, conditions that favor conidial germination, lesion expansion, and sporulation. In the mountainous production areas of Xixia, cooler temperatures encourage the use of high-humidity, semi-enclosed houses to stabilize temperature, which may further limit ventilation and promote the build-up of Penicillium inoculum. These interacting features of bag cultivation—substrate sterility, bag configuration, and microclimatic management—may therefore predispose shiitake to P. bialowiezense blue mold, in a manner that is ecologically distinct from the Trichoderma green mold complex.

Given the edible nature of shiitake fruiting bodies, chemical interventions are restricted [40]. Therefore, integrated strategies emphasizing hygiene and environmental control are paramount [4], including rigorous sanitation of growing rooms and equipment between cropping cycles and optimized humidity management to minimize prolonged surface wetness.

This initial investigation focuses on a limited geographic scope and cultivation period. To our knowledge, this is the first confirmed report of P. bialowiezense on L. edodes, expanding the host range of the species and underscoring the need for integrated disease management and continued surveillance in mushroom production; future work should survey the regional and seasonal distribution of the pathogen and potential reservoirs of inoculum within cultivation facilities, and quantify infection thresholds and the roles of temperature, relative humidity, ventilation, and soaking practices in epidemic development, and develop rapid, on-farm diagnostics (LAMP) and evaluate non-chemical interventions compatible with edible mushrooms.

5. Conclusions

From blue mold outbreaks in bag-cultivated shiitake (L. edodes) in Xixia County, China, 55 Penicillium isolates were obtained, and three representative isolates (LE06, LE15, and LE26) showed consistent cultural and micromorphological traits. Multilocus sequencing (ITS, benA, CaM, and rpb2) and phylogenetic analysis placed these isolates in the Penicillium bialowiezense clade with strong bootstrap support. Spray inoculation of healthy cultivation bags reproduced characteristic blue mold symptoms on substrate surfaces and fruiting bodies, and the pathogen was reisolated and sequence-confirmed, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. These results provide a clear etiological basis for targeted diagnostics and preventive management in bag-based shiitake production.

In theory, inoculating naturally occurring saprophytes as “protective” colonizers could suppress Penicillium and Trichoderma contamination through competitive exclusion and antagonism. In principle, candidate organisms could be selected from the resident microbiota of consistently healthy shiitake cultures and screened for safety and efficacy under production conditions. This prospect highlights the need for future microbiome studies integrating bacteria–fungi community profiling of healthy versus contaminated bags, coupled with isolation-based functional assays to identify keystone taxa associated with disease suppression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and Q.N.; methodology, T.W.; software, T.W.; validation, C.W., E.Z. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, T.W.; investigation, C.W.; resources, S.H.; data curation, T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W.; writing—review and editing, T.W.; visualization, T.W.; supervision, S.H. and Q.N.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Q.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agricultural Biomass Green Conversion Technology University Scientific Innovation Team in Henan Province, grant number 24IRTSTHN036 and the quality improvement project of shiitake mushroom industry in the water source area of the middle route of South-to-North Water Diversion, grant number Z20221343035.

Data Availability Statement

All nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been deposited in NCBI GenBank in Table 2. Records can be accessed via the NCBI Nucleotide database: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ (accessed on 20 October 2025) using the listed accession numbers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Q.; Hu, S.; Song, Z.; Cui, X.; Kong, W.; Song, K.; Zhang, Y. Relationship between flavor and energy status in shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) harvested at different developmental stages. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 4288–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Xia, Z.; Liu, C.; Nie, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wadood, S.A.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Rogers, K.M.; Yuan, Y. Model optimization for geographical discrimination of Lentinula edodes based stable isotopes and multi-elements in China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 118, 105160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, L.-H.; Su, Q.-H.; Gao, X.-F. Edible Mushroom Polysaccharides: A Review. Curr. Top Nutraceutical Res. 2023, 21, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanayake, A.J.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Luangharn, T.; Liyanage, W.K.; Caige, L.; Zhao, Q. Fungal threats to global mushroom cultivation: Diseases, competitor molds, and management strategies—A review. Mycosphere 2025, 16, 3130–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.-Y.; Choi, J.-N.; Sharma, P.K.; Lee, W.-H. Isolation and Identification of Mushroom Pathogens from Agrocybe aegerita. Mycobiology 2010, 38, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.T.; Bian, Y.B.; Xu, Z.Y. First Report of Trichoderma oblongisporum Causing Green Mold Disease on Lentinula edodes (shiitake) in China. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Cao, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, M.; Liu, C.; Yan, L.; Bian, Y. Diversity and effect of Trichoderma spp. associated with green mold disease on Lentinula edodes in China. Microbiologyopen 2016, 5, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukahuta, C.; Limtong, S.; Suwanarit, P.; Nutalaya, S. Species Diversity of Trichoderma Contaminating Shiitake Production Houses in Thailand. Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 2000, 34, 478–485. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Pan, H.; Wu, Y.; Choi, K.W. Mushroom Growers Handbook 2-Shiitake Cultivation; MushWorld: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005; pp. 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau. Technical Specifications for Registration of Geographical Indication: Xixia Xiang Gu (Xixia Mushroom). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/geographical-indications-register/eambrosia-public-api/api/v1/attachments/65629 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Wu, N.; Qiao, J.; Li, X. The spatial diffusion of agricultural specialized production under government promotion: A case study of mushroom production in Xixia county. Geogr. Res. 2017, 8, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Xixia Shiitake: How a Chinese agricultural Brand Builds an International Profile. 2016. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/qg/201612/t20161205_5397901.htm (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Kocsubé, S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J. A review of recently introduced Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and other Eurotiales species. Stud. Mycol. 2024, 107, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Hong, B.; Niu, S. New Phthalides and Isochromanone Derivatives from the Deep-Sea-Derived Fungus Penicillium bialowiezense A3. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.H.; Li, C.T.; Li, Y. First Report of Penicillium brevicompactum Causing Blue Mold Disease of Grifola frondosa in China. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, H.; Sun, W.; Hu, Z.; et al. Mycophenolic Acid Derivatives with Immunosuppressive Activity from the Coral-Derived Fungus Penicillium bialowiezense. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prencipe, S.; Siciliano, I.; Gatti, C.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Botta, R.; Spadaro, D. Several species of Penicillium isolated from chestnut flour processing are pathogenic on fresh chestnuts and produce mycotoxins. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garello, M.; Piombo, E.; Buonsenso, F.; Prencipe, S.; Valente, S.; Meloni, G.R.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldón, T.; Spadaro, D. Several secondary metabolite gene clusters in the genomes of ten Penicillium spp. raise the risk of multiple mycotoxin occurrence in chestnuts. Food Microbiol. 2024, 122, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.G.; Genee, H.J.; Kaas, C.S.; Nielsen, J.B.; Regueira, T.B.; Mortensen, U.H.; Frisvad, J.C.; Patil, K.R. A new class of IMP dehydrogenase with a role in self-resistance of mycophenolic acid producing fungi. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, F.; Sharifirad, A.; Yakhchali, B.; Ansari, S.; Fatemi, S.S.-A. Production of Mycophenolic Acid by a Newly Isolated Indigenous Penicillium glabrum. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2420–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pennerman, K.K.; Wu, G.; Hua, S.S.T.; Yu, J.; Jurick, W.M.; Guo, A.; Bennett, J.W. Characterization of Blue Mold Penicillium Species Isolated from Stored Fruits Using Multiple Highly Conserved Loci. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano-Rosario, D.; Keller, N.P.; Jurick, W.M. Penicillium expansum: Biology, omics, and management tools for a global postharvest pathogen causing blue mould of pome fruit. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanashiro, A.M.; Akiyama, D.Y.; Kupper, K.C.; Fill, T.P. Penicillium italicum: An Underexplored Postharvest Pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 606852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.K.; Sang, H.K.; Woo, S.K.; Park, M.S.; Paul, N.C.; Yu, S.H. Six species of Penicillium associated with blue mold of grape. Mycobiology 2007, 35, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.-N.; Lin, X.-H.; An, M.-M.; Zhao, G.-Z. Two new species of Penicillium (Eurotiales, Aspergillaceae) from China based on morphological and molecular analyses. MycoKeys 2025, 116, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Lu, J. First Report of Blue Mold on Sparassis crispa Caused by Penicillium sumatrense in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.S.D.A.; Jarek, T.M.; de Jesus, G.L.; de Oliveira, G.D.; Cuquel, F.L. First report of Penicillium brevicompactum causing disease in Pleurotus ostreatus. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2024, 96, e20210103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Penicillium and Related Genera. In Fungi and Food Spoilage; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 203–338. [Google Scholar]

- Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hong, S.-B.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Varga, J.; Yaguchi, T.; Samson, R.A. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Houbraken, J.; Popma, S.; Samson, R.A. Two new Penicillium species Penicillium buchwaldii and Penicillium spathulatum, producing the anticancer compound asperphenamate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 339, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR 348 Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-B.; Cho, H.-S.; Shin, H.-D.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houbraken, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Wang, X.-C.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Hubka, V.; Bensch, K.; Samson, R.A.; et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 95, 5–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuneda, A.; Murakami, S.; Gill, W.M.; Maekawa, N. Black spot disease of Lentinula edodes caused by the Hyphozyma synanamorph of Eleutheromyces subulatus. Mycologia 1997, 89, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Li, Y. First Report of Cobweb Disease Caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum on Cultivated Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes) in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Y.S.; Li, T.H.; Li, Y. First Report of a New Myxogastria (Stemonaria longa) Causing Rot Disease on Shiitake Logs (Lentinula edodes) in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, S.C.; Hsiang, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.L. First Report of Physarella oblonga on Lentinula edodes in China. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shen, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, D.; Shang, X.; Tan, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Analysis of heavy metal content in Lentinula edodes and the main influencing factors. Food Control 2021, 130, 108198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.