Abstract

The calmodulin-binding protein 60 (CBP60) family comprises essential Ca2+-responsive transcription factors that orchestrate salicylic acid (SA)-mediated immunity and broader stress responses. Despite being extensively characterized in model species, the CBP60 family remains poorly understood in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), a globally significant cucurbit crop highly susceptible to aphid infestation and fusarium wilt. In this study, we performed a comprehensive genome-wide identification and characterization of the CBP60 gene family in watermelon, identifying 16 putative ClaCBP60 members, all of which harbor the conserved calmodulin-binding domain. These genes are non-randomly distributed across chromosomes, featuring a prominent cluster of 10 members on chromosome 3. Phylogenetic analysis across seven cucurbit species categorized the CBP60 proteins into four distinct subfamilies, revealing both evolutionary conservation and lineage-specific diversification. Gene structure and conserved motif analyses revealed shared core domains with subfamily-specific variations, indicative of functional divergence. Furthermore, synteny analysis showed strong collinearity with cucumber and melon, reflecting the evolutionary stability of key CBP60 loci. Transcriptional profiling under F. oxysporum infection and aphid infestation revealed dynamic expression patterns, with ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 exhibiting rapid and robust induction during the early stages of both stresses. These findings indicated that ClaCBP60 genes operate in a coordinated yet diversified manner to modulate defense signaling against F. oxysporum and aphid attack. This study provides a systematic insight into CBP60 family members in watermelon, establishing a foundation for validation and molecular breeding aimed at enhancing biotic tolerance.

1. Introduction

Watermelon (C. lanatus) is a major cucurbit crop of considerable global economic importance; however, its productivity is severely constrained by biotic stresses. Among these, the soil-borne vascular pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum (Fon) and phloem-feeding aphids represent two of the most devastating threats worldwide [1,2,3]. Although these two stressors possess distinct infection strategies, Fon invading from the soil and aphids attacking aerial tissues, they interestingly converge on the plant’s vascular system, the critical transport network for water and nutrients. Aphids penetrate leaf tissues to extract sap from the phloem, thereby inflicting mechanical damage and facilitating virus transmission [4]. Simultaneously, Fon colonizes the xylem vessels, obstructing water transport and inducing progressive vascular browning and wilting [5,6]. This convergence on vascular tissues highlights vascular immunity as a pivotal battleground for watermelon survival. Accordingly, the identification of key transcriptional regulators that can orchestrate defense responses within these vascular tissues against both piercing-sucking insects and vascular pathogens is of great breeding value. Moreover, the widespread reliance on chemical pesticides and fumigants to control these pests and pathogens has accelerated resistance evolution, increased production costs, and raised serious environmental and food-safety concerns [7,8]. Thus, breeding resistant watermelon cultivars represents the most sustainable and effective long-term strategy. Nevertheless, progress remains limited due to an incomplete understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying watermelon defense responses.

Plant immunity against piercing-sucking insects and vascular pathogens is mediated by intricate phytohormone signaling networks, particularly salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET), with SA playing a pivotal regulatory role [9]. Precise modulation of SA biosynthesis and downstream defense gene expression depends on transcriptional regulators [10,11]. Among these, the CBP60 family integrates calcium signaling with SA-mediated immunity [12,13]. CBP60 proteins are characterized by a conserved calmodulin-binding domain (CaMBD; Pfam PF07887), which enables calcium-dependent regulation, and many members also contain nuclear localization signals, consistent with their predominant localization in the nucleus, where they function as transcription factors [14]. Initially characterized in the model species Arabidopsis thaliana, the CBP60 family comprises eight members, including CBP60g and its paralog SARD1 (SYSTEMIC ACQUIRED RESISTANCE DEFICIENT 1), which act as master transcriptional activators of SA accumulation and systemic acquired resistance [15,16]. These transcription factors directly bind to the promoters of key defense genes, most notably ICS1, encoding the rate-limiting enzyme in the predominant isochorismate pathway of SA biosynthesis [17]. Consequently, CBP60g and SARD1 significantly enhance resistance to biotrophic bacterial and fungal pathogens.

CBP60 family members have been identified across diverse plant species and exhibit functional diversification in both biotic and abiotic stress responses. In rice (Oryza sativa), the CBP60 family has undergone significant expansion to 15 members, which exhibit differential expression patterns in response to pathogen infection and drought stress [18,19]. Tomato harbors 11 CBP60 genes that display structural variation and induced expression following pathogen or abiotic stresses, implicating them in both immune responses and thermotolerance [20]. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that the CBP60 family originated early in land plant evolution, with the immune-associated CBP60g/SARD1 clade undergoing rapid diversification and positive selection across angiosperms, likely driven by persistent pathogen pressure [20,21]. This evolutionary plasticity, together with compensatory interactions among subfamily members, enhances the robustness of SA-mediated immune signaling and confers resilience against pathogen effector suppression.

Although most of the functional studies on CBP60 proteins have focused on microbial immunity [16], accumulating evidence points to broader roles in defense against insect herbivory. Aphid infestation triggers rapid calcium influxes and SA accumulation in host plants, and transcriptome profiling in A. thaliana consistently shows upregulation of specific CBP60 genes under insect feeding stress, suggesting conserved roles in anti-insect defense [22]. Despite these advances, the CBP60 family remains largely uncharacterized in the Cucurbitaceae crops such as cucumber, melon, and watermelon, all of which are highly susceptible to aphid colonization. Aphid feeding in cucurbits activates multiple defense mechanisms, including callose deposition, reactive oxygen species bursts, and complex phytohormone crosstalk, yet baseline resistance varies substantially among species and cultivars [23].

In this context, the availability of high-quality watermelon genome assemblies provides an unprecedented opportunity to systematically investigate immune-regulatory gene families. The objectives of the present study were therefore: (1) to perform a comprehensive genome-wide identification and characterization of the CBP60 gene family in watermelon; (2) to elucidate their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, conserved motifs, chromosomal distribution, syntenic patterns across Cucurbitaceae, and cis-regulatory elements in promoter regions; (3) to investigate the expression profiles of ClaCBP60 genes in response to Fon infection and aphid infestation using quantitative real-time PCR. These findings provide new insights into the potential roles of CBP60s in watermelon defense and establish a foundation for functional validation and molecular breeding aimed at improving Fon and aphid resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Physicochemical Properties of CBP60 Gene Family Members in C. lanatus and the Other Six Cucurbit Species

The reference genome assembly and annotation files for watermelon (Citrullus lanatus inbred line ‘G42’) were downloaded from the Watermelon Genome Database. To identify CBP60 family members, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile corresponding to the calmodulin-binding domain (CaMBD; Pfam PF07887) was retrieved from the Pfam database and used to query the predicted watermelon proteome with HMMER v3.3.2 (E-value ≤ 1 × 10−5). Candidate sequences were further verified for the presence of an intact CaMBD using SMART [24] and the NCBI Conserved Domain Database [25]. Redundant or partial sequences were manually removed. An identical pipeline was applied to six additional cucurbit genomes accessed via the Cucurbit Genomics Database (http://cucurbitgenomics.org/v2/ (accessed on 5 May 2025)), including cucumber (Cucumis sativus), melon (Cucumis melo), bitter gourd (Momordica charantia), bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), wax gourd (Benincasa pruriens) and pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima).

Physicochemical properties of the validated CBP60 proteins, including amino acid length, molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI), instability index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were computed using the Expasy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 28 December 2025). Subcellular localization was predicted using CELLO v2.5 (https://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/ (accessed on 16 May 2025)) and Plant-mPLoc [26].

2.2. Gene Structure, Conserved Motif, and Chromosomal Localization of ClaCBP60

Exon–intron organization was derived from GFF3 annotation files and visualized with Tbtools V2.376 [27]. Conserved protein motifs were elucidated using MEME Suite v5.5.0 [28], with parameters set to identify 15 motifs of 6–50 residues in width and zero or one occurrence per sequence. Promoter sequences (2 kb upstream of the translation start site) were retrieved and analyzed for cis-regulatory elements using PlantCARE (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 28 December 2025) [29]. Chromosomal locations were extracted from genome annotation files and mapped using MapChart 2.32 [30]. Synteny analysis between watermelon and other cucurbit species was conducted with MCScanX (https://github.com/wyp1125/MCScanX, accessed on 28 December 2025) [31], employing default parameters. Collinear blocks and syntenic relationships were visualized using the Advanced Circos and Dual Synteny Plotter modules in Tbtools V2.376.

2.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Full-length CBP60 protein sequences from seven cucurbit species were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8.31 [32]. Phylogenetic reconstruction was conducted using the maximum-likelihood (ML) method in IQ-TREE v2.2.0 under the best-fit model selected by ModelFinder (BIC criterion), with branch support assessed using 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.4. Promoter and Cis-Acting Element Analysis

Promoter sequences (2 kb upstream of the translation start codon) were extracted using TBtools V2.376 and submitted to PlantCARE [29] for cis-acting regulatory element prediction. The identified elements were classified into functional categories based on their annotated biological roles, including hormone responsiveness (e.g., SA, JA, ABA, and ethylene), stress responsiveness (e.g., drought, low temperature, and pathogen infection), growth and developmental regulation, and light responsiveness. Their distribution patterns across ClaCBP60 promoters were subsequently visualized using Tbtools V2.376 to highlight potential regulatory modules.

2.5. Plant Material and Aphid Inoculations

Watermelon seedlings of the inbred line ‘ym-t’, a cultivar for its pronounced susceptibility to both biotic and abiotic stresses, were cultivated in a climate-controlled chamber (26 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, 60–70% relative humidity). Aphid individuals were collected from the watermelon plants in the farm of Yangzhou University and maintained in an incubator to establish a laboratory colony. The aphid species was identified as Aphis gossypii, a common phloem-feeding pest of cucurbits. At the three-leaf stage, plants were infested with approximately 50 wingless adults of Aphis gossypii per plant. Fully expanded leaves were harvested at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 144 h post-infestation (hpi), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. At each time point, samples from three individual plants were pooled to form one biological replicate, and three independent biological replicates were prepared.

2.6. Plant Growth and F. oxysporum Inoculations

The F. oxysporum isolate used in this work was obtained from the farm of Yangzhou University, China. Pathogen identification was performed using a combination of morphological and molecular approaches. Initially, classical morphological characteristics, including colony morphology and conidial features, were used for preliminary screening and identification (Supplementary Figure S1). This was followed by whole-genome resequencing to further validate and confirm the taxonomic status of the isolate.

For inoculum preparation, the verified F. oxysporum isolate was cultured in potato dextrose broth at 26 °C with shaking at 150 rpm for 3 days. Upon completion of incubation, the concentration of the resulting conidial suspension was quantified using a hemocytometer and adjusted to 1 × 106 conidia per milliliter for subsequent use. A modified root-dip method was used for inoculation. Uniform seedlings at the two-leaf stage were washed to remove adhering soil, trimmed by 2 cm at the root tip, and immersed in the conidial suspension for 20 min. The inoculated seedlings were then transplanted into sterile substrate and incubated in the dark at 26 °C and 80% relative humidity for 12 h, followed by growth in a controlled chamber at 26 °C, 80% relative humidity, and a 16 h/8 h light–dark cycle. Control plants were treated with sterile distilled water under identical conditions. Root samples were collected at 1, 3, 6, and 9 DPI, with three biological replicates per time point and three seedlings per replicate. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

2.7. Total RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), and genomic DNA contamination was removed by on-column DNase I digestion. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). Primers (Table S3) were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 and validated for specificity and efficiency. Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed in triplicate on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) using TB Green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara). Reactions comprised 10 μL 2× TB Green Premix, 0.4 μM each primer, and 2 μL diluted cDNA in a final volume of 20 μL. Cycling conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Gene-specific primers (Table S3) were designed using Primer3, and actin (ClG42_01g0162900.10) was used as the internal reference gene. And three technical replicates were performed per biological replicate. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [33].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.32 software. All experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). For the fusarium wilt treatment, differences in gene expression between the control group and the F. oxysporum inoculated group at each time point were evaluated using Student’s t-test to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). For the aphid infestation treatment, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied for multiple comparisons among groups to assess differences in gene expression. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and statistically distinct groups are indicated by different lowercase letters in the figures.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Physicochemical Properties of CBP60 Gene Family Members

A systematic genome-wide survey of the C. lanatus genome (G42) identified 16 CBP60 family members, which were designated ClaCBP60_01 through ClaCBP60_16 according to their chromosomal positions. All candidates were confirmed to harbor the conserved calmodulin-binding domain, and redundant sequences were excluded following rigorous domain validation. Physicochemical characterization revealed substantial heterogeneity among the encoded proteins (Table 1). Protein lengths ranged from 351 amino acids (ClaCBP60_11) to 852 amino acids (ClaCBP60_12), corresponding to molecular weights of approximately 39.70–95.96 kDa. Theoretical isoelectric points varied between 4.74 and 9.14, encompassing both acidic (ClaCBP60_04) and basic (ClaCBP60_06) proteins. Instability indices ranged from 33.22 to 54.75, indicating differences in predicted stability among paralogs. All proteins exhibited negative Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) values (−0.645 to −0.317), consistent with an overall hydrophilic nature. Subcellular localization predictions indicated that the majority of ClaCBP60 proteins (11) are targeted to the nucleus, consistent with their putative roles as Ca2+-responsive transcriptional regulators. Additional predicted localizations included mitochondria (3 members), cytosol (1 member), and chloroplast (1 member). To evaluate evolutionary conservation across the Cucurbitaceae, the identical identification workflow was applied to six additional cucurbit genomes. This analysis identified 23 members in C. sativus, 13 in C. melo, 6 in M. charantia, 11 in L. siceraria, 15 in B. pruriens, and 16 in C. maxima. Detailed physicochemical characteristics of these gene families are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of CBP60 family members in watermelon genome.

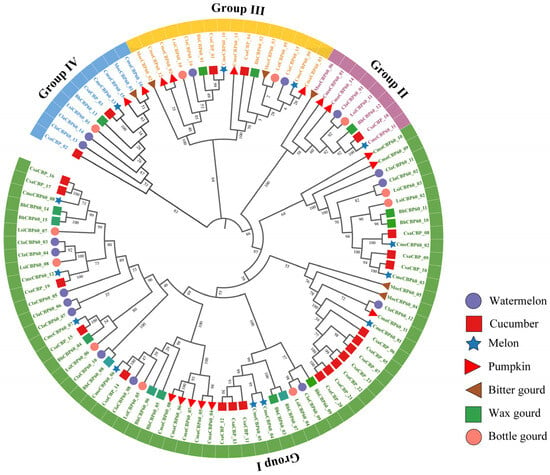

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Classification of the CBP60 Gene Family

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of the CBP60 gene family within Cucurbitaceae, a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis was performed using 100 CBP60 protein sequences derived from seven representative species: watermelon (16), cucumber (23), melon (12), pumpkin (17), wax gourd (15), sponge gourd (11), and bitter gourd (6). Multiple sequence alignment was conducted using MUSCLE, and a maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed in MEGA 11 with 1000 bootstrap replicates to ensure statistical robustness. The resulting phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) resolved the CBP60 proteins into four major subfamilies, reflecting both evolutionary conservation and lineage-specific diversification. Subfamily I emerged as the largest clade, containing 66 members, followed by subfamilies III (16 members) and II (10 members), while subfamily IV was the smallest, with only 8 members. Notably, ClaCBP60 genes from watermelon were distributed across all four subfamilies, indicating that gene family diversification in C. lanatus mirrors broader patterns observed throughout the Cucurbitaceae. Orthologous groups from different species consistently clustered together with strong nodal support (>80% bootstrap), underscoring conserved evolutionary trajectories and shared ancestral functions within this economically important plant family.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the CBP60 protein family in seven cucurbit species, including watermelon, cucumber, melon, pumpkin, bitter gourd, wax gourd, and bottle gourd. The dendrogram was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with the JTT amino acid substitution model in iTOL.

3.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of the Watermelon CBP60 Gene Family

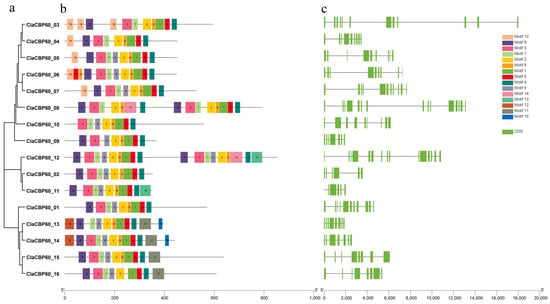

To investigate the structural characteristics and potential functions of the 16 ClaCBP60 genes, exon–intron organization and conserved protein motifs were analyzed (Figure 2). Motif analysis using MEME identified 15 distinct conserved motifs across the family. Members clustered within the same phylogenetic subfamily typically shared highly similar motif compositions and sequential arrangements, underscoring their close evolutionary relationships. A core set of motifs was present in nearly all ClaCBP60 proteins, highlighting the fundamental architectural conservation essential for calmodulin binding and transcriptional regulatory activity. Notably, the calmodulin-binding domain (CaMBD) was mapped to a combination of Motifs 1, 2, 4, and 5, which together form the functional interface for Ca2+/CaM interaction. In addition, subfamily-specific variations were observed. For instance, ClaCBP60_08 and ClaCBP60_12 uniquely harbored additional motifs (Motifs 14 and 15) that were absent from other paralogs.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, and gene structures of ClaCBP60 genes in watermelon. (a) The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with the JTT amino acid substitution model. (b) Conserved motifs of ClaCBP60 proteins were identified using MEME, the numbers represent different motifs. (c) The exon–intron structures of ClaCBP60 genes are illustrated, with green boxes denoting exons and black lines representing introns. The relative lengths of exons and introns are displayed according to the scale at the bottom.

Gene structure analysis revealed considerable heterogeneity in exon number and coding sequence length. Exon numbers ranged from 6 to 15, with corresponding coding sequence (CDS) lengths varying accordingly. Several members, including ClaCBP60_04, ClaCBP60_09, ClaCBP60_11, and ClaCBP60_13, exhibited compact organizations characterized by short CDS and few exons, consistent with streamlined regulatory roles. In contrast, ClaCBP60_03, ClaCBP60_08, and ClaCBP60_12 displayed markedly complex structures, featuring extended CDS regions and numerous exons.

3.4. Chromosomal Localization and Synteny Analysis

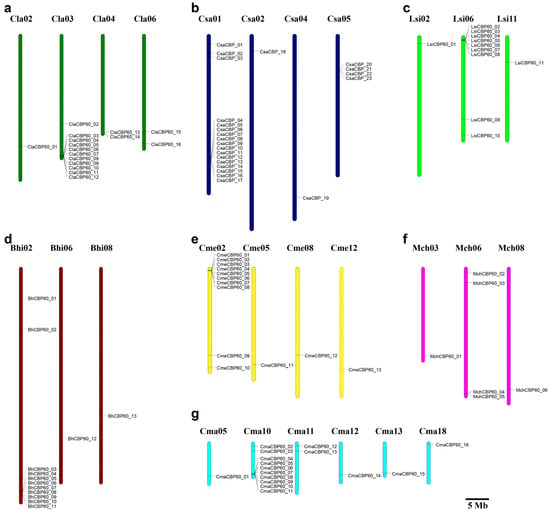

The 16 ClaCBP60 genes exhibited a non-random genomic distribution, being localized to only four chromosomes in the watermelon chromosomes (Figure 3; Table 1). Chromosome 3 harbored the vast majority of the family (11 genes), ten of which formed a dense genomic cluster within a confined region. BLASTP-based assessment of sequence similarity and intergenic distances revealed no evidence of recent tandem duplication among these clustered genes. The remaining five genes were sparsely distributed: one on Cla02, two on Cla04, and two on Cla06. Notably, no ClaCBP60 members were identified on the other seven chromosomes, underscoring a highly localized expansion pattern within the C. lanatus genome.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal localization of CBP60 genes in seven Cucurbitaceae species. The different colors indicate distinct Cucurbitaceae crops: (a) dark green represents watermelon; (b) dark blue represents cucumber; (c) light green represents bottle gourd; (d) brown to wax gourd; (e) yellow to melon; (f) purple to bitter gourd; (g) light blue to pumpkin.

Comparative mapping across Cucurbitaceae revealed analogous clustering in related species. In cucumber, for instance, CsaCBP60 genes were located on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, and 5, with a pronounced cluster on chromosome 3. Comparable high-density aggregations were observed in melon, pumpkin, wax gourd, and sponge gourd, but not in bitter gourd (Figure 3). Intraspecific synteny analysis in watermelon identified only one tandem duplication event (ClaCBP60_13 and ClaCBP60_14), while no segmental duplicates were detected among the large Cla03 cluster. Furthermore, interspecific synteny analysis across seven cucurbit genomes confirmed that clustered organization is a conserved feature in five of the six additional species examined. In these genomes, more than half of all CBP60 members resided within discrete clusters, highlighting the evolutionary significance of local gene aggregation in maintaining and expanding functional redundancy or diversity within this transcription factor family across Cucurbitaceae.

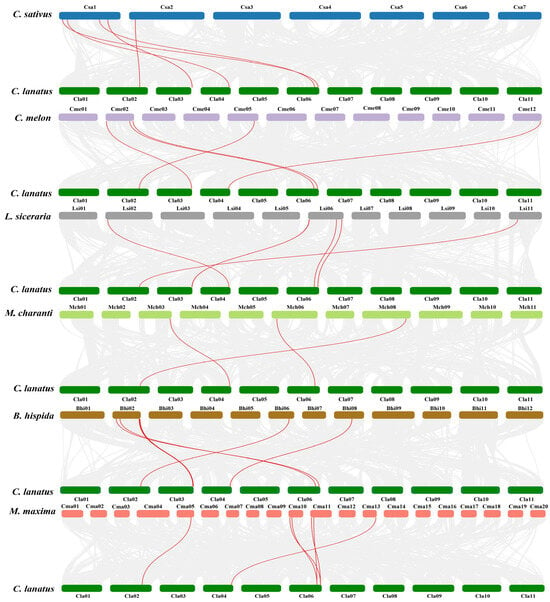

3.5. Interspecific Synteny Analysis of CBP60 Genes Across Cucurbitaceae

To investigate the evolutionary conservation and divergence of the CBP60 gene family following speciation within Cucurbitaceae, a comparative syntenic analysis was performed between watermelon and six representative cucurbit species. Collinearity mapping identified numerous conserved collinear blocks, confirming that a substantial proportion of CBP60 loci have been retained as orthologs since the most recent common ancestor (Figure 4). In total, seven ClaCBP60 genes participated in interspecific segmental duplication events, establishing syntenic relationships with homologs in at least one other cucurbit genome (Table S2). Notably, ClaCBP60_01, ClaCBP60_14, and ClaCBP60_15 each exhibited synteny with five of the six comparator species, highlighting their profound evolutionary conservation and probable indispensability for core family function. Furthermore, ClaCBP60_09 and ClaCBP60_16 were syntenic with four species, whereas ClaCBP60_13 showed collinearity exclusively with wax gourd (BhCBP60_13) and melon (CmeCBP60_13). The most restricted syntenic relationship was observed for ClaCBP60_11, which aligned solely with bottle gourd (LsiCBP60_03), suggestive of lineage-specific retention or functional specialization.

Figure 4.

Homology analysis of CBP60 genes among six Cucurbitaceae species, including watermelon, cucumber (C. sativus), melon (C. melo), bottle gourd (L. cylindrica), bitter gourd (M. charantia), wax gourd (B. hispida), and pumpkin (C. maxima). Red lines denote duplicated gene pairs, while gray lines represent all syntenic blocks within the reference genome.

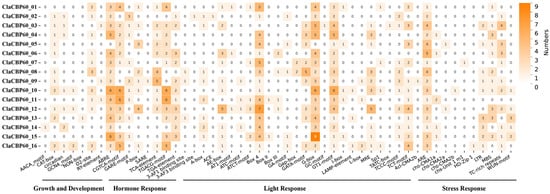

3.6. Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements in CBP60 Promoter Regions

To investigate the potential transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of the ClaCBP60 family, the 2 kb upstream promoter sequences of all 16 genes were scanned using PlantCARE. The cis-element profiles revealed a complex regulatory landscape with both conserved and divergent features. Light-responsive motifs (G-box) and general stress-related elements (ARE, TC-rich repeats) were widely distributed across most promoters, suggesting a broad sensitivity to environmental cues (Figure 5). Several promoters were enriched in hormone- and defense-related elements, including ABREs (ABA-responsive), TCA-elements (SA-responsive), TGACG/CGTCA motifs (JA-responsive), and W-boxes (WRKY-binding sites). This enrichment suggests the potential integration of ClaCBP60 genes into multiple hormone signaling pathways. Notably, promoters of ClaCBP60_08 and ClaCBP60_12 contained high densities of defense- and hormone-associated motifs together with MYB/MYC recognition sites, indicating potential inducibility under biotic stress. In contrast, promoters such as ClaCBP60_04 and ClaCBP60_09 were relatively depleted in defense motifs but enriched in light- or development-related elements, suggesting roles in constitutive growth or non-defense processes. Furthermore, ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 displayed particularly high motif counts, supporting their potential involvement in aphid-induced responses. Overall, the sparse distribution pattern indicates that ClaCBP60 members are partitioned into distinct regulatory subgroups rather than being uniformly responsive.

Figure 5.

Analysis of cis-regulatory elements in ClaCBP60 genes. Promoter regions comprising 2000 bp upstream of each ClaCBP60 coding sequence were scanned using the PlantCARE database to identify cis-regulatory elements. The numbers indicate the counts of each element type per gene.

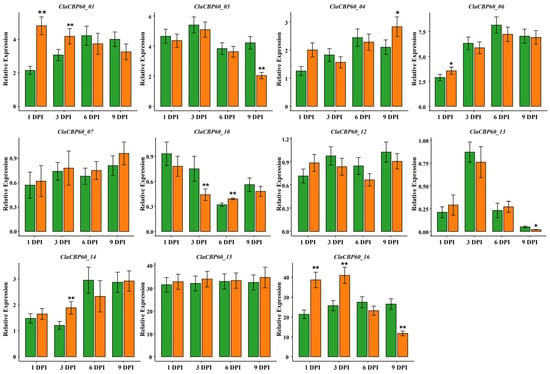

3.7. Expression Patterns of ClaCBP60 Genes in Response to F. oxysporum Infection

To further explore the potential involvement of ClaCBP60 genes in watermelon defense against fungal pathogens, the expression levels of all sixteen ClaCBP60 genes were examined in root tissues at 1, 3, 6, and 9 days post-inoculation (DPI) with Fon. The results revealed diverse and dynamic expression patterns in response to pathogen challenge. Of the sixteen genes, eleven of the 16 ClaCBP60 genes displayed high expression at least at one time point relative to mock-inoculated controls (Figure 6). Notably, ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 displayed the most rapid and pronounced induction. Specifically, ClaCBP60_16 showed a striking increase in transcript abundance that remained sustained throughout the entire nine-day experimental period. Several other members exhibited moderate or transient induction, whereas the remaining five genes exhibited no significant changes. These findings suggest that multiple ClaCBP60 family members are involved in watermelon immune responses to fungal pathogens.

Figure 6.

Relative expression level of eleven ClaCBP60 genes in watermelon in response to F. oxysporum infection. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in gene expression between the mock-inoculated control (water treatment) and F. oxysporum inoculated group for each gene at the corresponding time point, as determined by Student’s t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

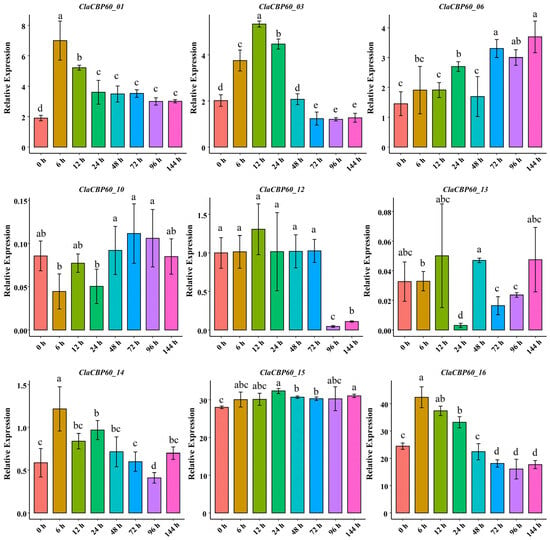

3.8. Expression Pattern Analysis of CBP60 Genes Under Aphid Infestation

To characterize the transcriptional regulation of the ClaCBP60 gene family in response to aphid attack, RT-qPCR was performed for all 16 members in leaf tissues at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h post-infestation with aphid infestation. Seven ClaCBP60 genes exhibited no detectable expression across the sampled time course. The remaining nine genes displayed marked and divergent expression patterns, underscoring substantial functional diversification within the family (Figure 7). Several members were rapidly and transiently upregulated following infestation. Notably, ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 underwent acute induction, with transcript levels peaking robustly at 6 h before returning to near-basal levels by 24 h post-infestation. Conversely, ClaCBP60_03 exhibited a more protracted response, with steady accumulation culminating at 12 h post-infestation, followed by a gradual decline. The remaining responsive genes displayed modest or oscillatory changes without distinct temporal peaks, suggesting auxiliary or context-dependent regulatory functions during prolonged aphid feeding.

Figure 7.

Relative expression of nine ClaCBP60 genes in response to aphid infestation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences, as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The CBP60 family comprises essential calcium-signal decoders that function as central regulators of plant immunity and stress responses. These proteins integrate early calcium signaling cascades with downstream defense pathways, primarily by modulating SA biosynthesis and activating defense-related genes [16,34]. Despite their documented importance in microbial defense, the CBP60 family has remained uncharacterized in watermelon, a globally important cucurbit crop highly susceptible to aphid and fusarium wilt. The present study conducted a comprehensive genome-wide identification of 16 ClaCBP60 genes in watermelon, analyzing their genomic features, phylogenetic relationships, synteny, and expression under biotic stresses. These findings provide new insights into the evolutionary conservation and functional diversification of the CBP60 family in cucurbits.

While all identified ClaCBP60 members contained the conserved calmodulin-binding domain, confirming their classification as Ca2+-responsive transcription factors [15]. Nevertheless, marked structural and sequence heterogeneity was observed in protein length, physicochemical properties, exon–intron organization, and conserved motif composition. Such structural plasticity likely reflects subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization events that have driven the diversification of regulatory roles within the family. Phylogenetic reconstruction involving 100 CBP60 proteins from seven Cucurbitaceae species resolved four distinct subfamilies, with watermelon representatives present in all clades. This distribution indicates that C. lanatus has retained core ancestral lineages while undergoing lineage-specific expansions and diversifications, patterns broadly congruent with evolutionary trends reported in rice and tomato [15,35]. Such diversification may contribute to functional specialization in immunity and stress responses.

4.1. Chromosomal Clustering and Structural Divergence of ClaCBP60s

Chromosomal mapping revealed a striking clustering pattern, with 10 of the 16 ClaCBP60s forming a dense gene cluster on chromosome 3. Sequence similarity and intergenic distance analyses provided no evidence of recent tandem duplications within this cluster, implying that their aggregation arose through alternative mechanisms, such as ancient segmental duplications, transposon-mediated rearrangements, or selective retention of ancestral loci [36,37]. Similar clustering patterns observed in cucumber and melon indicate that local genomic aggregation is a conserved organizational feature of the CBP60 family across the Cucurbitaceae. However, it is essential to note that these patterns are currently inferred from genome assemblies; future functional and evolutionary studies will be required to determine if they correspond to genuine lineage-specific expansion processes. Future functional and evolutionary studies will be necessary to determine whether these patterns correspond to genuine expansion processes.

Despite this genomic clustering, substantial structural divergence exists among the chromosome 3 residents. For instance, ClaCBP60_08 and ClaCBP60_12 possess highly complex exon–intron architectures and unique motifs. The retention of core calmodulin-binding motifs alongside subfamily-specific structural innovations supports an evolutionary model in which essential Ca2+/CaM-dependent functions are preserved, while structural modifications expand the family’s regulatory repertoire to meet complex environmental challenges [21,38].

4.2. Conserved and Lineage-Specific Synteny of ClaCBP60s

Interspecific synteny analysis underscored the evolutionary stability of several ClaCBP60 loci, particularly ClaCBP60_01, ClaCBP60_14, and ClaCBP60_15, which displayed high collinearity with orthologs across five or more cucurbit species. This high degree of conservation, especially pronounced within the Cucumis genus, implies strong purifying selection, likely reflecting their indispensable roles in fundamental immune signaling [39]. Conversely, lineage-specific synteny patterns, such as the exclusive collinearity of ClaCBP60_11 with bottle gourd, point toward species-specific retention or specialization. This mosaic of conserved and divergent syntenic patterns illustrates the dual evolutionary forces shaping the CBP60 family: the preservation of core regulatory modules and adaptive diversification to address species-specific ecological pressures [11].

4.3. Regulatory Roles of ClaCBP60s in Fon and Aphid Defense

A pivotal finding of this study is the robust, simultaneous induction of ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 under two ecologically distinct stresses: the phloem-feeding aphid and the soil-borne vascular pathogen Fon. In natural agroecosystems, plants must integrate diverse signals from simultaneous insect and microbial attacks. Their rapid upregulation (peaking at 6 h post-infestation for aphids and 1 DPI for Fon) suggests they function as early responders in the watermelon immune surveillance system.

This dual responsiveness can be mechanistically supported by their promoter architecture. Our cis-element analysis revealed that the promoters of ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 are densely populated with SA-responsive elements (TCA-element) and JA/wound-responsive motifs (TGACG-motif), and pathogen-inducible W-boxes. This complex regulatory landscape enables these genes to function as signal integration hubs, decoding Ca2+ signatures triggered by both aphid stylet penetration and fungal hyphal invasion into coherent transcriptional outputs [40,41].

In Arabidopsis, CBP60g and SARD1 are master regulators essential for SA biosynthesis and systemic acquired resistance [34,42]. The functional conservation observed here suggests that ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 may serve as functional orthologs of these master regulators in watermelon. Notably, unlike the redundancy often seen in model plants, their specific high-amplitude induction is the primary determinant of vascular immunity in C. lanatus. Consequently, the genes ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16 represent ideal targets for molecular breeding. Manipulating these regulators, either through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated fine-tuning or targeted overexpression, offers a promising strategy to engineer broad-spectrum resistance against both piercing-sucking pests and vascular wilt diseases. Such an approach could potentially bypass the growth-defense trade-offs often associated with constitutive immune activation, providing a more sustainable method for enhancing crop resilience.

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study presents the first comprehensive, genome-wide characterization of the CBP60 gene family in watermelon, revealing its evolutionary features, structural variation, and potential roles in responses to Fon attack and aphid infestation. While these results provide an essential framework for understanding ClaCBP60 functions, the conclusions are largely derived from computational predictions and transcript-level analyses, which inherently limit functional interpretation. Future work should prioritize experimental validation of these candidate genes. In particular, quantifying downstream defense-related metabolites and phytohormones in both resistant and susceptible backgrounds following aphid feeding or fungal infection will be critical for determining whether transcriptional activation of key members (ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16) corresponds to measurable biochemical and physiological defense outputs. Parallel functional assays using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout, targeted overexpression, or virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) will enable direct assessment of the causal contributions of individual ClaCBP60 genes to resistance.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive genome-wide characterization of the CBP60 gene family in watermelon, identifying 16 members harboring conserved calmodulin-binding domains and exhibiting an uneven distribution across chromosomes. Phylogenetic, structural, and synteny analyses revealed both strong evolutionary conservation and lineage-specific diversification within the Cucurbitaceae. Promoter analysis further demonstrated the enrichment of hormone and defense-related cis-regulatory elements, suggesting that ClaCBP60 genes participate in complex regulatory networks associated with phytohormone-mediated signaling. Expression profiling under Fon infection and aphid infestation showed rapid and robust induction of several family members (ClaCBP60_01 and ClaCBP60_16) across both biotic stresses. Collectively, these findings highlight the pivotal contribution of the CBP60 family to broad-spectrum defense signaling and identify high-priority candidate genes for molecular breeding strategies aimed at enhancing resistance to major insect pests and fungal pathogens in watermelon.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010051/s1. Table S1: The information of CBP60 family members in Arabidopsis, cucumber, bottle gourd, wax gourd, melon, bitter gourd, pumpkin; Table S2: The blastp results of CBP60 members in watermelon compared with those in six other Cucurbitaceae species; Table S3: Forward and reverse primer sequences of ClaCBP60 genes; Figure S1: Morphological characteristics of Fusarium oxysporum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: X.Y. and H.F.; Methodology: Y.M. and J.T.; Experiments, data collection, and preparation of figures and tables: X.W. and L.Z.; Data analysis and original draft writing: Y.M. and J.T.; Manuscript review, revision, and improvement: X.Y. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20220573).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Haipeng Fu was employed by the company Tianjin Vegetable Research Center, Vegetable Research Institute of Tianjin Kernel Agricultural Science & Technology Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Su, Z.; Lan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, J.; Guo, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luan, F.; Zhang, X. Methyl jasmonate-dependent hydrogen sulfide mediates melatonin-induced aphid resistance of watermelon. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, P.; Tenner, G.; Joshi, L.; Mrema, F.; Bhatta, B.P. Current status of Fusarium wilt resistance research in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus): A review. Indian J. Arid. Hortic. 2025, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadon, P.; Corre, M.-N.; Lugan, R.; Boissot, N. Aphid adaptation to cucurbits: Sugars, cucurbitacin and phloem structure in resistant and susceptible melons. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Sohail, H.; Qiu, L.; Gu, J. Fortifying crop defenses: Unraveling the molecular arsenal against aphids. Hortic. Adv. 2024, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Patra, K.; Pai, H.; Aguilar-Pontes, M.V.; Berasategui, A.; Kamble, A.; Di Pietro, A.; Redkar, A. Molecular dialogue during host manipulation by the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2024, 62, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Liu, G.; Yao, X.; Li, P.; Yang, X. Characterization of the watermelon seedling infection process by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem Ullah, R.M.; Gao, F.; Sikandar, A.; Wu, H. Insights into the effects of insecticides on aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae): Resistance mechanisms and molecular basis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, M.A.; Amer, A.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Ibrahim, E.-D.S.; El-Hefny, D.E.; Salem, M.Z. Efficacy of chemical and bio-pesticides on cowpea aphid, Aphis craccivora, and their residues on the productivity of fennel plants (Foeniculum vulgare). J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, D.; Cai, N.; Liu, R.; Dong, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tu, X. Saliva of Therioaphis trifolii (Drepanosiphidae) activates the SA plant hormone pathway, inhibits the JA plant hormone pathway, and improves aphid survival rate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caillaud, M.-C.; Asai, S.; Rallapalli, G.; Piquerez, S.; Fabro, G.; Jones, J.D. A downy mildew effector attenuates salicylic acid–triggered immunity in Arabidopsis by interacting with the host mediator complex. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Gonçalves, N.M.; Matiolli, C.C.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Barros, P.M.; Oliveira, M.M.; Abreu, I.A. SUMOylation of rice DELLA SLR1 modulates transcriptional responses and improves yield under salt stress. Planta 2024, 260, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, D.; Guo, Y.; Han, Y.; Mao, T.; Huang, Y. A nucleoporin-associated signaling cascade controls plant immunity via histone modification. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Wang, K.; Sun, L.; Xing, H.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Guo, H.-S.; Zhang, J. The plant-specific transcription factors CBP60g and SARD1 are targeted by a Verticillium secretory protein VdSCP41 to modulate immunity. eLife 2018, 7, e34902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tsuda, K.; Sato, M.; Cohen, J.D.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. Arabidopsis CaM binding protein CBP60g contributes to MAMP-induced SA accumulation and is involved in disease resistance against Pseudomonas syringae. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truman, W.; Sreekanta, S.; Lu, Y.; Bethke, G.; Tsuda, K.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. The CALMODULIN-BINDING PROTEIN60 family includes both negative and positive regulators of plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 1741–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tsuda, K.; Truman, W.; Sato, M.; Nguyen, L.V.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. CBP60g and SARD1 play partially redundant critical roles in salicylic acid signaling. Plant J. 2011, 67, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Verk, M.C.; Bol, J.F.; Linthorst, H.J. WRKY transcription factors involved in activation of SA biosynthesis genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D.; Prasad, B.D.; Nirala, R.; Sahni, S. Functional Analysis of Calmodulin Binding Protein 60s in Disease Resistance Responses in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D.; Prasad, B.D.; Sahni, S.; Nonhebel, H.M.; Krishna, P. The expanded and diversified calmodulin-binding protein 60 (CBP60) family in rice (Oryza sativa L.) is conserved in defense responses against pathogens. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-S.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-X.; Yu, F.; Hao, G.-J.; Yin, G.-M.; Dou, Y.; Zhi, J.-Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, J.-F. CBP60b clade proteins are prototypical transcription factors mediating immunity. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Majsec, K.; Katagiri, F. Pathogen-driven coevolution across the CBP60 plant immune regulator subfamilies confers resilience on the regulator module. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, T.R.; Canham, J.; Toyota, M.; Avramova, M.; Mugford, S.T.; Gilroy, S.; Miller, A.J.; Hogenhout, S.; Sanders, D. Real-time in vivo recording of Arabidopsis calcium signals during insect feeding using a fluorescent biosensor. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2017, 56142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Kang, H.; Ning, G.; Feng, J.; Xiao, X.; Wan, Z.; Hereward, J.P.; Wang, Y. Differential activation of defense responses in cucumbers by adapted versus non-adapted lineages of the cotton-melon aphid. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 2830–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D222–D226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Shen, H.-B. Plant-mPLoc: A top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorrips, R. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-h.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y. ChIP-seq reveals broad roles of SARD1 and CBP60g in regulating plant immunity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.D.; Ramakant; Sahni, S.; Kumari, D.; Kumar, P.; Jambhulkar, S.J.; Alamri, S.; Adil, M.F. Gene expression analyses of the calmodulin binding protein 60 family under water stress conditions in rice. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Smith, D.R. An overview of online resources for intra-species detection of gene duplications. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1012788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Chen, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Ancient duplications and grass-specific transposition influenced the evolution of LEAFY transcription factor genes. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, D.; Prasad, B.D.; Dwivedi, P. Genome-wide analysis of calmodulin-binding Protein60 candidates in the important crop plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chovelon, V.; Feriche-Linares, R.; Barreau, G.; Chadoeuf, J.; Callot, C.; Gautier, V.; Le Paslier, M.-C.; Berad, A.; Faivre-Rampant, P.; Lagnel, J. Building a cluster of NLR genes conferring resistance to pests and pathogens: The story of the Vat gene cluster in cucurbits. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, I.; Mai, V.C.; Gabryś, B. Phytohormonal signaling in plant responses to aphid feeding. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 2057–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, S.; Huang, Y. Molecular interactions between plants and aphids: Recent advances and future perspectives. Insects 2024, 15, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Busta, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, P.; Jetter, R.; Zhang, Y. TGACG-BINDING FACTOR 1 (TGA 1) and TGA 4 regulate salicylic acid and pipecolic acid biosynthesis by modulating the expression of SYSTEMIC ACQUIRED RESISTANCE DEFICIENT 1 (SARD 1) and CALMODULIN-BINDING PROTEIN 60g (CBP 60g). New Phytol. 2018, 217, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.