Abstract

In the current climate change context and the potential to extend exotic crops in Romania, sweet potato could become an option for extensive areas with optimum ecophysiological conditions to provide economic and ecological benefits and assure food security. This study aimed to validate the suitability, photosynthetic performance, yield productivity, and sugar content of three sweet potato cultivars, KSC, Koretta, and Hayanmi, in Central Romania. Three key phenophases were selected: the beginning of flowering (P1), 50% tuber formation/full flowering (P2), and total tuber formation/leaves and stems bleached and dry (P3), respectively. At the beginning of flowering, extreme heat and moisture stress showed a reduced effect on the sweet potato development and photosynthetic parameters. The only exception was the assimilation rate for Hayanmi, which was markedly lower, with the highest relative chlorophyll content and leaf dry biomass. Koretta registered increased values for stomatal features. A higher tuber weight was registered for Hayanmi in P2 due to slightly increased rainfall and elevated evapotranspiration. In P3, the temperatures dropped sharply, rainfall exceeded evapotranspiration, and KSC accumulated a seven times higher value for tuber weight. The total biomass was 2–3 times higher for KSC in P3. Sugar content was negatively correlated with tuber weight, and Hayanmi had 1% higher values compared with KSC and Koretta. Sweet potato showed a variety-specific response to ecophysiological conditions, and for each variety, these physiological features suggest potential advantages for different cropping scenarios.

1. Introduction

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.), the sixth most significant edible crop in the Convolvulaceae family, contributes to sustainable global food security and Sustainable Development Goal 2, “zero hunger” [1,2].

The areas with a tradition of sweet potato production are in tropical and temperate (monsoon) regions such as Africa and Asia [3], the regions between 48° N and 40° S, located between 0 and 3000 m above sea level, and characterized by mean multiannual temperatures in the range of 15–35 °C [1,4]. In origin countries, aboveground biomass, including leaves, is used, whereas belowground biomass is of particular interest as food due to carbohydrate accumulation in tuber roots [4].

Sweet potato offers diverse benefits for the environment, for farmers’ economic well-being, and for human health. With rapid, extensive shoot growth, it is beneficial for weed biocontrol and requires low-nutrient soil to achieve high yield potential; therefore, it could be an essential chain for crop rotation [5,6]. Its extract exhibits antimicrobial, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties [7,8,9,10] and is highly nutritious, rich in starch, protein, dietary fiber, β-carotene, anthocyanins, and vitamins A, C, and E. People with type 2 diabetes are advised to consume it for health benefits [11].

In Romania, the first steps toward introducing sweet potato into the cropping system were undertaken at the Research and Development Station for Plant Cultivation on Sands Dăbuleni [12] in a small area with quite specific climate and soil conditions in the extreme south of Romania, along the Danube Plain, with a very hot and dry warm season, and dominant sandy soils. Due to these specific conditions, the subregion is also known as the Romanian Sahara [13].

In Southern Romania, promising results for sweet potatoes, with yields exceeding 30 t ha−1, have already been obtained [14], and some varieties can achieve a maximum yield performance of 53 t ha−1 [15]. So far, most studies have focused on sandy soils, where sweet potato has been cultivated under research conditions for more than 10 years. Even though it has been proven that sweet potato is drought-resistant and finds suitable conditions in sandy soils (as in the extreme south of Romania), its highest potential for cultivation is estimated to be in regions with more fertile soil conditions and with a wetter climate [14,16], which are specific to most lowlands in Romania.

This research is part of a larger study within the ExoCrop project available at https://exocrop.indecosoft.ro/en/home/ (accessed on 31 December 2025), which aims to explore climate opportunities and assess the suitability of sweet potato, among other exotic crops, in various regions of Romania with a moderate–temperate continental climate and more fertile soils.

Sweet potato was selected due to (i) its high versatility that could enable cropping and be expanded to other areas in most Romanian lowland regions, particularly under changing climate conditions [4], and to (ii) its economic, ecological, and health benefits.

Ecophysiological assessment using photosynthetic parameters enables non-destructive monitoring of plants’ carbon assimilation capacity. Biomass accumulation and its traits are correlated with photosynthetic rate, whereas leaf stomatal traits are good indicators of gas exchange under environmental conditions. All these parameters can serve as early indicators of the final yield and are necessary for farmers to establish a viable cropping system.

This study focused on validating the photosynthetic performance of sweet potato in new regions of Southeastern Europe (Central Romania). To accomplish this aim, a series of objectives were proposed: (i) to validate the crop suitability in Central Romania and to test the reach to full maturity of the entire principal growth stages of the growing season; (ii) to determine the physiological performance in the flowering stage; and (iii) to examine the yield productivity and sugar contents of different cultivars grown in field conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Data

2.1.1. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted under field conditions at the Cojocna Research Station of the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, located in Central Romania (Transylvania). Three sweet potato varieties, KSC, Koretta, and Hayanmi, were selected for experimental trials. They were selected because they have already been adapted in a small region in Southern Romania (South Oltenia). However, that region is characterized by distinct natural conditions, such as extreme summer heat, a large annual temperature range, and predominantly sandy soil, which differ markedly from those of the testing region in this study. Sweet potato cuttings were planted on an area of 1000 m2 on 19 June 2025. The seedling density was 40,000 plants ha−1.

The land was previously cultivated with a disc, and 40 cm high mounds were mechanically created to promote optimal development by thickening the sweet potato roots. The distance between the mounds was 70 cm. At the beginning of the experiment, NPK 20:20:20 mineral fertilizer was applied at a rate of 400 kg ha−1. Before planting, grey foil was placed over the mounds to optimize weed control and prevent evaporation.

The topsoil was medium loam, while deeper layers were clay-rich. The soil properties were pH 7.88, a humus level of 5.03, a nitrogen index of 4.27, a phosphorus content of 16.42 ppm, and a potassium content of >400 ppm.

In Romania’s climatic conditions, sweet potatoes bloom; however, seed production is very rare. Because the growing season length (GSL) is insufficient, they are vegetatively propagated by cuttings (shoots).

Sweet potato seedlings were produced at the Dăbuleni Research and Development Station for Plant Culture on Sands. The tubers were planted in late March in a mixture of sand and peat (1:1 volume ratio). An optimal microclimate was maintained with a foil coverage until the shoots emerged. A hardening period of 5–6 days of reduced irrigation and increased aeration was established prior to field transplantation. Uniform shoots (30–35 cm in length; 6–7 nodes) were harvested at an age of 40–45 days and followed by a 24 h wilting period at 20 °C to facilitate handling and prevent breakage during establishment. The planting period for sweet potato shoots must ensure that the plants will benefit from a 120-day growing season.

For long-term comparison of local climate between the region where the sweet potato was first acclimatized in the extreme south of Romania and the location under study in this research, we used historical temperature and precipitation gridded data extracted for the pixels corresponding to the two locations from the national databases made available by the National Meteorological Administration (https://data.gov.ro/dataset/date-meteorologice-zilnice-gridate, accessed on 1 October 2025). The datasets spanned 64 years (1961–2024) at a spatial resolution of 1 km and a temporal resolution of 1 day.

Daily weather data for short-term analysis of mean and extreme temperatures, precipitation, wind speed, and solar radiation were collected in situ during the growing season using an automatic, robust, wireless meteorological station (Davis Vantage Pro2) placed in the experimental field. The data were collected every 15 min and were complemented by hourly data from the nearest national weather network station (Sărmașu). The Sărmașu weather station was located less than 15 km from the experimental field, with a similar topography, making the two datasets comparable with respect to the main parameters. The dataset from the Sarmasu weather station is available at www.meteomanz.com (accessed on 20 November 2025). For further processing, the most relevant variables and derived indices were aggregated daily across various phenophases and over the entire growing season.

2.1.2. Physiological Methods and Parameters

The RCC (Relative Chlorophyll Content)

This physiological parameter was assessed using an Apogee Instruments MC-100 chlorophyll meter (North Logan, UT, USA). The parameter was determined directly in SPAD units using a nondestructive field method. The relative chlorophyll content was assessed during the phenophase of anthesis beginning (P1), full flowering with 50% tuber formation (P2), and total tuber formation, with leaves and stems bleached and dry (P3), according to the extended BBCH growth scale. This phenophase selection emphasizes the most critical shifts in resource allocation, which depend on the environmental sensitivity. By selecting these three pivot points, P1 represents the baseline for the plant’s potential, where shifts in hormonal balance happen to prepare for storage; P2, with the maximum physiological stress because it is simultaneously supporting flowers and rapidly expanding tubers, represents a peak moment for water and nutrient demand; and P3 represents the sink–source completion relationship, and it highlights the final translocation of dry matter from the dying leaves into the mature tubers.

Gas Exchange Measurements

A portable gas exchange system, GFS-3000 (Waltz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany), was used for measurements of leaf gas exchange characteristics in P1. The system features an environmentally controlled cuvette with an 8 cm2 window area and is equipped with a full-window leaf chamber fluorimeter for sample illumination and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. The measurements were made at an ambient CO2 concentration of 400 mmol mol−1 and light intensity of 1000 mmol m−2 s−1. The leaf temperature was kept between 26.51 and 27.12 °C. After leaves were placed in the system cuvette, the light was switched on, and the leaves were stabilized until the stomata opened and steady-state values of the net photosynthetic rate (A) and stomatal conductance to water vapor (GH2O) were obtained, typically requiring 20–30 min for each measurement.

Stomatal Number, Length, Width, and Aperture

For stomatal assessment in P1, fresh leaves were studied under an Olympus CX43 microscope (Tokyo, Japan)with a 12 MP PROMICAM PRO4K camera (Prague, Czech Republic) at 20×. The camera was calibrated using the PROMICRA 3.2 software. All values for the number, length, width, and aperture of the stomata were obtained by accurate measurements in the software. Then, all recorded data were exported to Excel files.

Leaf Area

Leaf area was assessed in P1 and P2. For precise measurements, images were acquired, and ImageJ 1.46r was used to perform the analysis.

Fresh and Dry Biomass

Leaf dry biomass was determined gravimetrically in P1 and P2. Carbon allocation in the ecophysiological conditions of sweet potato was highlighted. The standard method was used to determine the leaves’ dry biomass parameter; the samples were oven-dried at 105 °C for 48 h until reaching a constant weight.

2.1.3. Climatic Data and Indices

The agrometeorological and agroclimatic analysis used multiple variables and derived indices. A brief climatic analysis was performed to compare two regions in Romania: Southern Romania (Dăbuleni), where the sweet potato was first cultivated/acclimatized in Romania, and Central Romania (Cojocna), where the crop’s ecophysiological performance was assessed in this paper.

For a multi-perspective analysis on short-term series (the growing season of year 2025) and for comparison between the two locations, we considered some of the extreme temperature and precipitation indices, as they were established by the Expert Team for Sector-Specific Indices of the World Meteorological Organization for the agriculture sector, and some additional ones calculated based on observation data. They are synthetically presented in Table 1. For long-term comparison, we used only the extreme temperature and precipitation indices, given the limited availability of other variables and indices.

Table 1.

Meteorological variables and indices used for the agroclimatic analysis (following https://climpact-sci.org/indices/, accessed on 1 November 2025, modified and completed).

2.1.4. Agroclimatic Differences Between Southern and Central Romania Regions

The climatic differences between the Southern and Central regions of Romania were consistent across most indices analyzed (Table 2), indicating a considerably warmer climate in Southern Romania than in the test regions, as indicated by both the mean and extreme values, thereby justifying the field test of the considered crop.

Table 2.

Long-term agroclimatic indices (1961–2024) for comparison between the test region and the “traditional” region for sweet potato in Romania (data processed by the authors following https://data.gov.ro/dataset/date-meteorologice-zilnice-gridate, accessed on 1 November 2025).

Thus, the mean temperatures in Central Romania (the focus region of this research) are about 2 °C lower than those recorded in Southern Romania, whereas in the case of extreme temperatures, especially in the maximum ones, the difference is higher than 5 °C. The number of days on which the TX exceeded the fixed thresholds (SU, TX30, and TX35) was also much lower in the testing region than in the region where the sweet potato had already been acclimatized and cultivated for more than 12 years (Southern Romania) (Table 2).

In terms of the GDD and GLS, the differences were pronounced: the GDD values in Central Romania were approximately 600 °C lower than in Southern Romania, and the GLS was shorter by 23 days (Table 2).

When precipitation amounts were compared, no substantial difference was detected; however, the CDD index indicated approximately 30% shorter dry spells (in mean and maximum duration) in the test region (Central Romania).

Given the significant climatic differences between the two regions, we considered it necessary to assess the performance of the sweet potato crop to support its further recommendation for large-scale cultivation in Transylvania (Central Romania), a traditional potato-growing region, and where farmers could be more open to adopting crop changes as an adaptive measure for climate change toward smart agriculture.

2.2. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the RStudio console, version 4.0.5 [17]. Basic statistics were performed using the “psych” package [18], and the average and standard error (SE) were displayed. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher LSD were performed using the “agricolae” [19] and “broom” packages [20].

The boxplot figures were made with the help of free online tools produced by Plotly.js (v2.24.1) (https://www.statskingdom.com/advanced-boxplot-maker.html, accessed on 1 December 2025). Therefore, the inclusive quartile was defined, and the median value is shown in the figures, along with the ANOVA (F, p) and the LSD test significance. Different letters in the figures above the boxplots indicate differences between treatments at p < 0.05. All parameters were analyzed for the Pearson correlation detection using the “Hmisc” package [21] and plotted with the “corrplot” package [22]. Two types of correlation analysis were performed to assess the relationships among the parameters extracted for each variety. The first type was performed on the pooled dataset to identify generalized physiological dependencies across the studied varieties. The approach enabled the identification of indicators that remain consistent across varieties. The LSD test further explored the presence of significant differences among varieties for each parameter. The second type of correlations was performed both on pooled data and at the variety level (provided as annexes) to explore the relations between photosynthetic parameters, chlorophyll, water content, and biomass features.

3. Results

3.1. Photosynthetic Parameters’ Assessment During the Beginning of the Flowering Phenophase

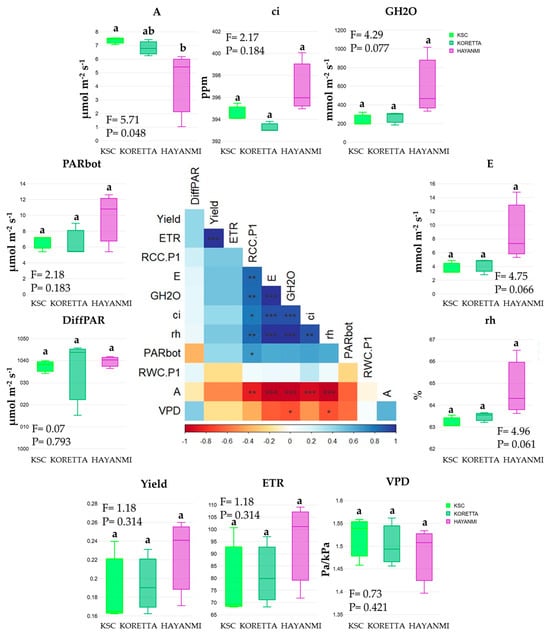

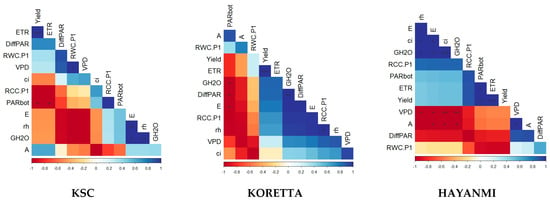

Plant photosynthetic efficiency, measured as the assimilation rate or net photosynthesis (A), was the only parameter that differed substantially between Hayanmi and KSC, whereas Koretta had an intermediate value. The analysis performed on the three sweet potato varieties during anthesis showed reduced references for all other recorded parameters (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Photosynthetic parameters of sweet potato at the beginning of the flowering stage. Different letters above indicate significant differences between varieties based on LSD test apt p < 0.05, ANOVA F and p value. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

The absence of significant differences was not directly related to the trends observed in the parameters analyzed. Hayanmi reached the maximum value for GH2O, E, PARbot, Yield, ETR, and rh. Parameter ci reached the maximal value in KSC, while VPD had similar values for all three varieties.

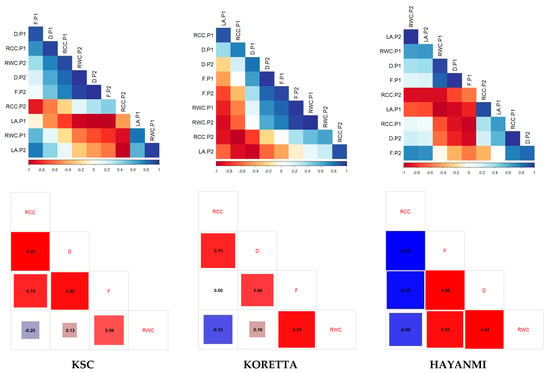

The correlations between photosynthetic parameters (Figure 1) showed three groups of interconnected parameters. The first one showed a negative relationship between VPD and GH2O, followed by the same correlation between ci and RCC.P1. The second group comprised the positive correlations between the E–RCC.P1 group and rh-A, with 10 interrelations. A singular positive relation was observed between PARbot and RCC.P1. The third group, with almost perfect positive correlations, was identified between ETR and Yield. To further investigate the relationships at the variety level, separate correlations were performed (Figure A1). KSC variety showed a significant relationship between Yield and ETR, as well as rh, E, and GH2O. Meanwhile, PARbot was negatively correlated with both Yield and ETR. For the Koretta variety, the same parameter was negatively associated with GH2O, DiffPAR, and E, whereas the association between Yield and ETR was preserved. Hayanmi exhibited the strongest correlations between parameters. GH2O, ci, E, and rh sustained each other, while Yield, ETR, and PARbot maintained the same trend of relationship. Meanwhile, both VPD and A were in opposition to GH2O, ci, E, and rh.

3.2. Stomatal Conductance and Architecture During the Beginning of the Flowering Phenophase

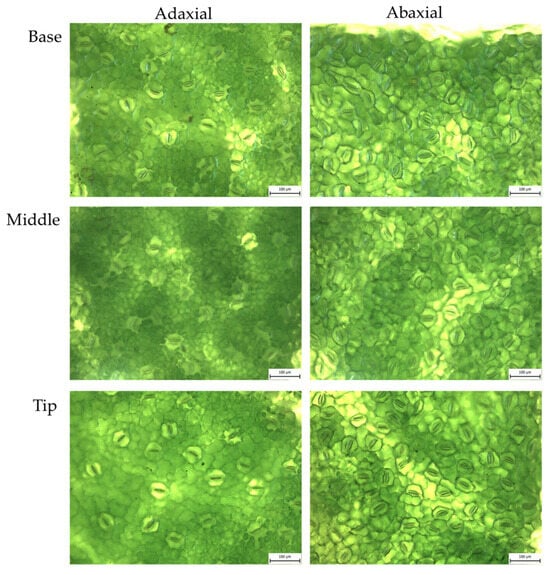

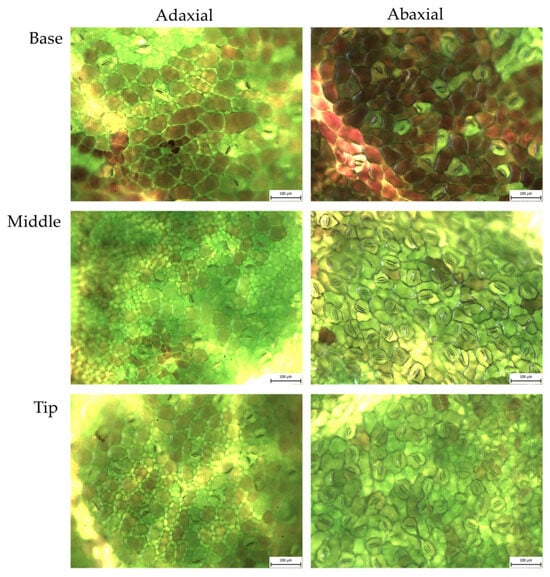

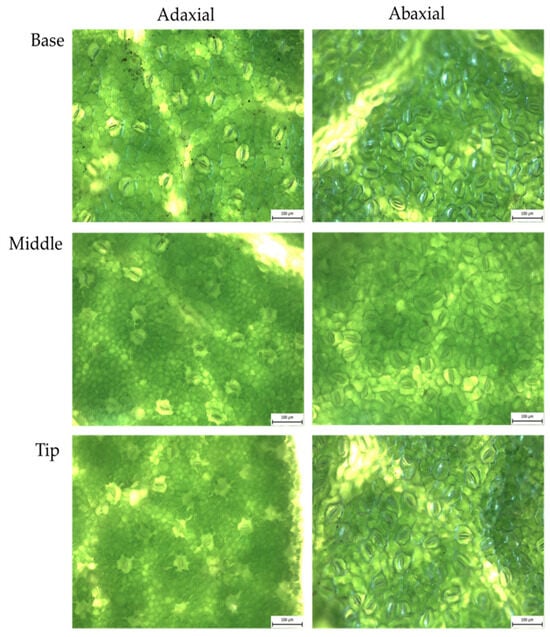

The analysis of stomatal parameters showed notable differences between the three varieties tested (Table 3) across 14 parameters from the entire database (Table A1). The general trend observed was not uniform across all varieties; it was more variety-specific.

Table 3.

Stomatal differences associated with the sweet potato variety at P1.

Four parameters showed differences between stomata on the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces (B.no, M.no, L, and A). Koretta had the highest number of adaxial stomata at the leaf base, two times higher than Hayanmi (Figure A2 and Figure A3). On the abaxial side, KSC (Figure A4) showed the highest number of stomata at the leaf base; however, the difference between the first and last values recorded was less than 50%. The difference for each variety in terms of this parameter was two to three times higher in favor of the abaxial position. The number of stomata in the adaxial middle of the leaf showed a similar peak in Koretta, which was higher than in the other two varieties. For the same parameter, the stomatal number in the abaxial position was under 70 for KSC, with 10–14 stomata more than the other two varieties. Both the stomatal length and aperture differed notably among the varieties in the two positions analyzed. The adaxial position showed lower values than the abaxial position, with a maximum reached for the KSC variety. The differences between KSC and Koretta were minimal, whereas all comparisons between KSC and Hayanmi were greater across parameters. Another five parameters showed marked differences only in the adaxial (four) or abaxial (one) position. Adaxial stomatal length and width exceed 50 units in Koretta, higher than in Hayanmi, where these parameters were 40% and 70% lower. The leaf tip feature highlighted the same Koretta variety, with the maximum stomatal length exceeding Hayanmi and a higher aperture compared with KSC. The stomatal aperture from the middle of the abaxial position showed KSC with the maximum value recorded, while Hayanmi had only 60% of this value. The relative chlorophyll content showed distinct patterns across the three varieties, with Hayanmi at over 550 units and exceeding 150–200 units.

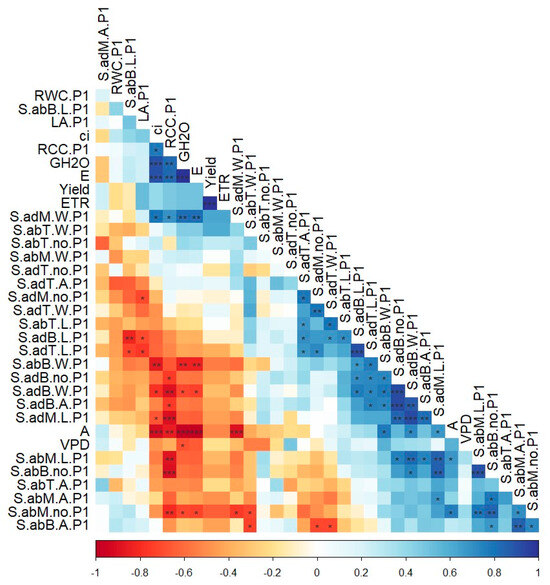

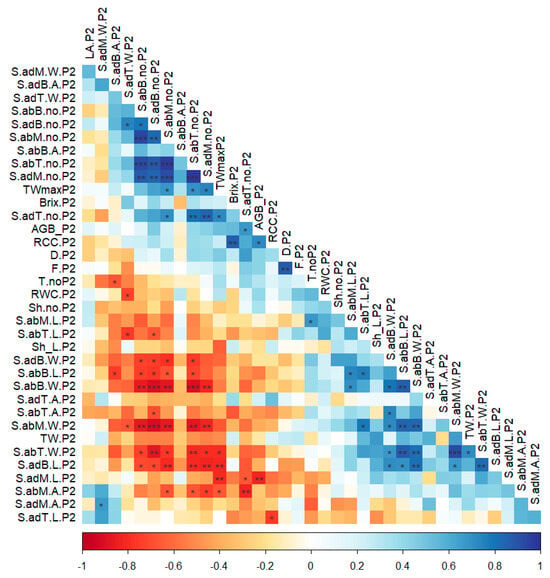

The exploration of parameter interconnections revealed multiple relationships, both positive and negative (Figure 2). The number of abaxial middle leaf stomata was negatively correlated with their width, GH2O, and RCC.

Figure 2.

Sweet potato abaxial and adaxial stomata features (L = length, W = width, no = number, and A = aperture) correlated with stomatal conductance (GH2O), first assessment of relative chlorophyll content (RCC.P1), and leaf area (LA.P1). In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

The relative chlorophyll content was negatively correlated with the abaxial and adaxial base leaf stomata number, width, and aperture, respectively, and with the middle leaf stomata length. One notable positive correlation was observed between adaxial and abaxial stomatal numbers at the mid-leaf, suggesting an inverse shift between the two sides. The number positively influenced abaxial middle leaf stomatal aperture, while their length showed a positive correlation between adaxial and abaxial positions. The same direction of correlation was observed for stomatal number at both positions. A very high correlation was found between adaxial base stomatal numbers, apertures, and recorded width. A multitude of important positive correlations across the entire database were not identified between the same parameter in adaxial and abaxial positions, or with stomatal determinations. These values were recorded for the parameters in different positions on the analyzed leaves. The length of stomata in the abaxial middle leaf was associated with the abaxial base leaf stomatal number. The width of abaxial base stomata was correlated with the length of middle leaf stomata, and the length of adaxial stomata in the base and tip of the leaf.

3.3. Relative Water Content and Fresh and Dry Biomass Changes from the Beginning of Flowering to 50% Tuber Formation

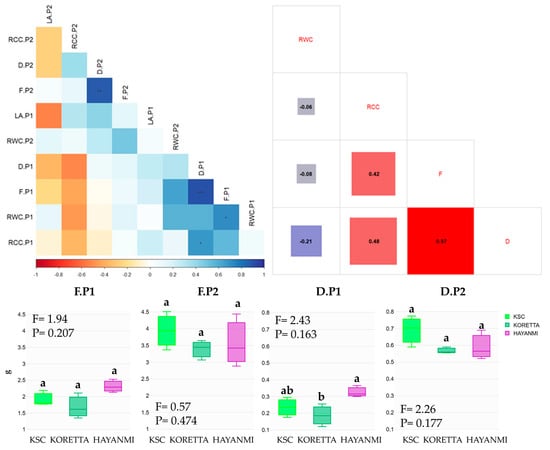

Measurements performed during the anthesis initiation and 50% tuber formation phenophases show both positive and negative correlations between parameters recorded in both stages (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fresh and dry biomass in the phenophase of flowering and 50% tuber formation. Different letters above indicate significant differences between varieties based on LSD test apt p < 0.05, ANOVA F and p value. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

Leaf area and relative chlorophyll content show no significant shift from the first phenophase to the next. Meanwhile, there were positive correlations between fresh biomass and relative water content, and between relative chlorophyll content and dry biomass at the beginning of anthesis. Both fresh and dry biomass were positively correlated in the two phenophases. Interestingly, there was no correlation between fresh biomass and RCC or LA during the tuber formation phenophase. When the entire database was analyzed for correlations between water and chlorophyll content, and fresh and dry biomass, the analysis indicated a different pattern of linkage. Fresh and dry biomass were almost perfectly correlated, and both were highly correlated with relative chlorophyll content. Dry biomass was negatively correlated with relative water content; however, this parameter was not affected by fresh biomass. There was a low correlation between relative water and chlorophyll content, indicating a lack of a determinative relationship between the recorded values. At the variety level, the correlation trends differed in the direction of the relationships (Figure A5). Hayanmi RCC was negatively correlated with biomass and RWC, while for KSC and Koretta, RCC was positively influenced by dry biomass, and RWC by fresh biomass.

The analysis of differences between varieties revealed distinct patterns of variation in the recorded parameters (Figure 3). Fresh biomass was higher for Hayanmi in anthesis and for KSC during early tuber formation. Variation within each variety was higher in the second phenophase analyzed, but overall differences were not notable. At the beginning of anthesis, dry biomass showed substantial variation, with Hayanmi reaching the highest value. This parameter presented a different pattern of increase from anthesis to 50% tuber formation. Hayanmi and Koretta doubled their values, while KSC tripled its values. No clear differences were detected among varieties; however, Koretta was the most stable, with leaves of similar weight.

Meanwhile, the relative chlorophyll content decreased from anthesis to tuber formation and varied among varieties (Figure 4). Hayanmi recorded 500–600 SPAD units at anthesis, approximately 200–300 SPAD units higher than the other two varieties. At tuber formation, this parameter was highest in the KSC variety, while both Koretta and Hayanmi had similar values. The relative water content was similar during phenophases, with a slight difference between varieties at anthesis.

Figure 4.

Relative chlorophyll content and relative water content in the phenophase of flowering beginning and 50% tuber formation. Different letters above indicate significant differences between varieties based on LSD test apt p < 0.05, ANOVA F and p value.

3.4. Leaf Dependent Parameters in 50% Tuber Formation Phenophase

Variety had a strong influence on the values recorded for stomatal features during the tuber formation phenophase (Table 4). The number of leaf base stomata recorded showed a similar variation between varieties, both on adaxial and abaxial positions. KSC reached the maximum stomatal count, whereas Hayanmi scored below 60%.

Table 4.

Stomatal differences associated with the sweet potato variety at P2.

The middle position of the leaf showed the highest number of adaxial stomata, with KSC exceeding the value from the base by 20. Both Koretta and Hayanmi maintained the adaxial stomatal value as recorded at the base of the leaf. The abaxial stomata in the middle of the KSC leaves increased by more than 20% compared with the base, while for Hayanmi, they decreased. It is worth noting that the abaxial position at the tip of the leaf recorded the highest number of stomata along the entire length across all varieties. Hayanmi had the lowest significant stomatal values among the abaxial samples. The tip of the leaf in the adaxial position showed the lowest values along the entire leaf for Koretta and Hayanmi, and an intermediate one for KSC. Compared with the number of stomata, Hayanmi presented the highest values of stomatal length and width in both positions from the base of the leaf. This variety had stomata of nearly identical types in both adaxial and abaxial positions.

The other two varieties showed wider adaxial widths and opposite combinations in the abaxial positions. For the other four stomatal parameters, great differences were observed only at the abaxial position and were highest in the Hayanmi variety. The stomatal length and width at the tip of the leaf were similar, whereas the width in the middle of the leaf was different. Across all three parameters, a pronounced difference was observed, particularly in the Koretta variety.

The correlations among parameters in the tuber-formation phenophase revealed clearly significant interactions in both positive and negative directions (Figure 5). Both the width and length of stomata were negatively impacted by the number of stomata. On the contrary, the number of stomata along the entire leaf was positively correlated between adaxial and abaxial areas. The width and length of stomata showed a similar trend of correlations along the entire leaf.

Figure 5.

Leaf dependent parameters in 50% tuber formation phenophase. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

3.5. Tuber Weight and Sugar Content at 50% Tuber Formation and Total Tuber Mass Reached

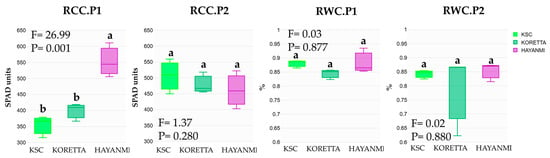

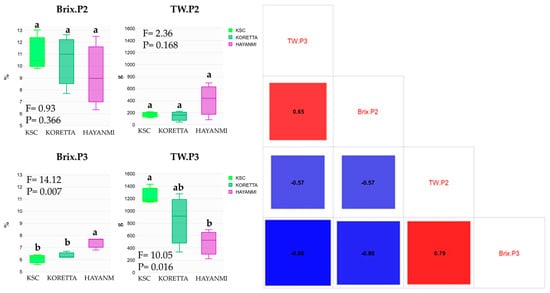

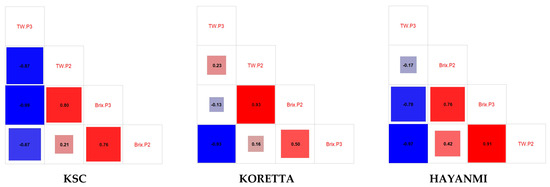

Tuber weight and Brix (°Bx) values recorded in tuber formation and at the end of the growing season showed divergent correlations (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sugar content of sweet potato at 50% tuber formation and at the total tuber mass reached phenophase. Different letters above indicate significant differences between varieties based on the LSD test at p < 0.05, ANOVA F and p values.

Brix values in tuber formation positively impacted the tuber weight in the total tuber mass reached phenophase, while higher-weight tubers provided a higher °Bx at the end of the growing season. High tuber weight during tuber formation was associated with lower °Bx values and lower tuber weight in the total tuber mass reached phenophase. The same trend of correlation was observed between °Bx values in the total tuber mass reached phenophase and tuber weight, as well as between °Bx during the previous phenophase and °Bx at P3. Tuber weight drastically reduced the sugar percentage values; therefore, high values during tuber formation were translated into a lower sugar content in the total tuber mass reached phenophase. For Hayanmi, tuber weights were negatively correlated, while for KSC, the final tuber weight was negatively correlated with both the previous tuber weight and Brix contents (Figure A6).

Koretta showed an interesting relationship between tuber weight and Brix, with a positive correlation at 50% tuber formation and a negative one at harvesting. For this variety, there was no important correlation between tuber weights, suggesting that this parameter increases in a short period at the end of the vegetation period, regardless of the weight reached at 50% tuber formation.

By analyzing the differences between the varieties for the two parameters, multiple shifts were recorded. Sugar content during early tuber formation showed a similar maximal value but exhibited 2–6% variations within the same variety. A clear difference was observed in the total tuber mass reached phenophase, with Hayanmi having a °Bx more than 1% higher than that of the other two varieties. When comparing the two phenophases, the sugar content decreased by half for all varieties. An opposite trend was observed for tuber weight, with higher values for Hayanmi recorded during early tuber formation. At P3, KSC produced 7 times more tubers than in the previous phenophase, whereas Koretta showed 2–6 times higher values.

3.6. Aboveground, Belowground Biomass, Root/Shoot Ratio, and Tuber Quality Interaction

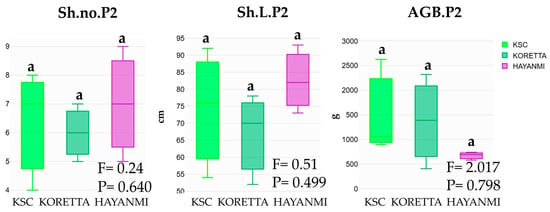

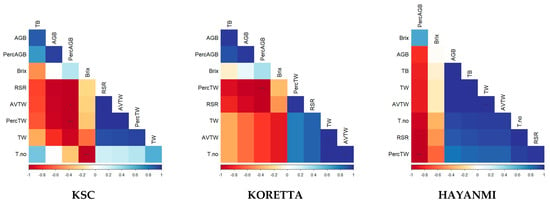

The Koretta variety presented average values between the two other ones. The shoot number was slightly higher in the Hayanmi variety, but their length was similar in both Hayanmi and Koretta (Figure 7). Aboveground biomass varied greatly for the KSC and Koretta varieties and remained approximately constant for Hayanmi, but did not differ greatly in the total tuber mass phenophase.

Figure 7.

Shoot number and length, and aboveground green biomass, in 50% tuber formation phenophase. Different letters above indicate significant differences between varieties based on LSD test apt p < 0.05, ANOVA F and p value.

At the end of the growing season, four additional parameters presented significant differences between varieties (Table 5). The aboveground biomass reached more than 1700 g in KSC, with values of 600–1100 g in the other two varieties. The total biomass showed a 2–3 times higher value in KSC than in the other two varieties, while the average tuber weight was almost double in KSC compared with Hayanmi. The maximum tuber weight favored the KSC variety, whose value was almost three times that of Hayanmi (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biomass and tuber characteristics in total tuber mass reached phenophase.

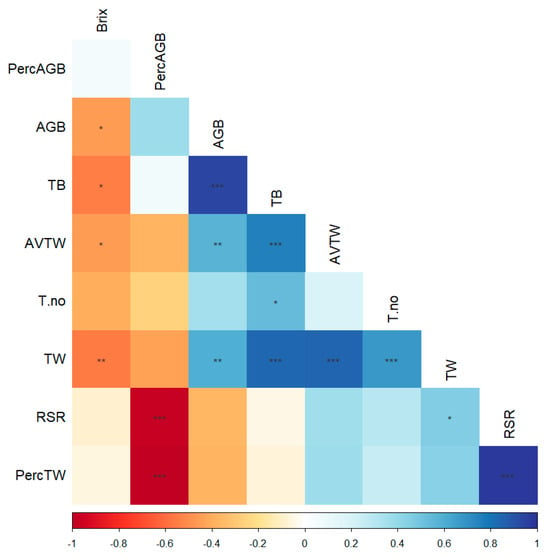

For this phenophase, the correlations between biomass parameters and sugar content were analyzed (Figure 8). Brix values were negatively correlated with tuber weight and aboveground and total biomass. Total biomass was positively correlated with aboveground biomass and with the average and total tuber weight. An interesting aspect was that sugar content was not linked to the share of aboveground biomass relative to total biomass, a parameter associated with formed tubers. For Koretta, tuber weight was negatively influenced by the foliage developed during the growing season, whereas tuber number was positively correlated with tuber weight, suggesting that even at high tuber numbers, tuber development can be good (Figure A7). Hayanmi showed a clear negative relationship between above- and belowground biomass, implying allocation toward one or the other during the growing season. In terms of tuber development, they were correlated with the total biomass, indicating that this variety allocated its resources for tuber development, and its ability to use the foliage developed with a higher performance. KSC showed two trends of correlations, positive for average tuber weights due to the root/shoot ratio and negative for Brix in relation to tuber number and between above- and belowground biomass.

Figure 8.

Aboveground and belowground biomass-correlated characteristics at the end of the growth season. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

The three selected varieties exhibited two types of ecophysiological requirements: the first were associated with their origin, while the others were associated with their specific adaptation to cultivation conditions. Breeding programs are oriented toward selecting genotypes with a high yield potential under water scarcity and a good stress tolerance index that represents an adaptive response [23,24,25]. This crop thrives in warm climates and presents resilience to moderate drought, but current climate changes are leading to an increase in water requirements and shifts in suitable cultivation areas [26,27]. There is an ongoing interest in improving sweet potato varieties and in selecting, from the high diversity of germplasm, those that outperform traditional/local ones [28,29]. Thus, there is a need for field validation studies that assess the crop response to various climatic and ecophysiological conditions [30,31].

The agroclimatic conditions for sweet potato in 2025 were analyzed for the entire growing season (19 June–15 October) and for three distinct phenophases: the beginning of flowering (19 June–28 July), full flowering + 50% tuber mass reached (29 July–24 September), and total tuber mass reached + leaves and stems bleached and dry (25 September–15 October). The results are synthetically presented in Table 6 and detailed below.

Table 6.

Meteorological variables and indices used for the agroclimatic analysis.

Thus, the agroclimatic conditions across the growing season showed distinct patterns that influenced each developmental phase. Over the entire vegetation period, temperatures were generally warm (19 °C), with substantial heat accumulation (GDD: 1067.5). However, several heat stress events occurred, including multiple days above 30 °C and three days above 35 °C. Rainfall cumulated 274.5 mm, while the evapotranspiration demand was high, resulting in a pronounced soil water deficit. Solar radiation levels were also elevated, supporting vigorous vegetative growth but increasing evaporative stress (Table 6).

During the beginning of flowering, temperatures peaked, with the highest mean and maximum values for the TX-related variables of the entire cycle. This period experienced frequent heat stress days and strong evaporative demand, but only moderate rainfall. Consequently, soil moisture deficits intensified. Although radiation levels were very favorable for photosynthesis, the combination of high heat and moisture stress during this sensitive phase may have negatively affected early tuber formation (Table 6).

Conditions during full flowering and the 50% final tuber mass phenophase were slightly cooler and more favorable for tuber formation, with no extreme heat days and moderate night temperatures. Solar radiation remained high, supporting active bulking. However, despite slightly increased rainfall, evapotranspiration remained elevated, and soil water deficits persisted. These sustained deficits during the primary bulking period could have limited potential tuber enlargement (Table 6).

By the time the total tuber mass stage was reached, temperatures dropped sharply, slowing physiological processes and nearly halting heat accumulation. Night temperatures frequently fell below 10 °C, and solar radiation declined substantially. Rainfall exceeded evapotranspiration, resulting in moisture replenishment rather than additional deficit. These conditions supported tuber maturation, skin set, and completion of the growth cycle, but were no longer conducive to further biomass accumulation (Table 6).

Hayanmi has a Korean origin and is recognized for its good adaptability and performance in a wide variety of environments, fitting well in sandy soils in Southern Romania [32,33,34], with potential yields ranging from 16.0 to 25 t ha−1, depending on the planting time [35]. The KSC variety, of Korean origin, was cultivated in sandy soil from the Danube Plain of Romania; it can lead to yields higher than 30–35 t ha−1 [36,37]. Koretta is a variety registered in Romania in 2023 [38] and is proposed as a new planting material for the next period.

Three types of parameters were measured to deepen the understanding of how sweet potato performs during the three selected phenophases under temperate ecophysiological conditions. Each of the measurements made was chosen to identify the most suitable and important characteristics that can be associated with one or another variety and provide a field response.

The selection of the first parameter category—net photosynthetic rate (A), relative humidity (RH), transpiration rate (E), and vapor pressure deficit (VPD)—was in accordance with their potential to show the photosynthesis efficiency, how varieties use water, and, finally, the productivity. PAR and A are indicators of photosynthetic rate and phytochemical efficiency [39,40]. The high values of RH reduced VPD, maintained stomatal conductance, and lowered ET0 (Table 6), the last parameter being responsible for water-use efficiency and water loss via transpiration [31,41]. Higher values of VPD corresponded to increased E and were visible in the closure of stomata and, thus, the reduction in photosynthesis [42]. The sweet potato assimilation rate in the absence of stress, across different studies, ranged from 20 to 35 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1, with variation among varieties and planting material, and can decline drastically in adverse environmental conditions [31,35,43]. The values observed in our study can be explained by using non-rooted shoots as the planting material, which originates from a different climate. Transpiration rates [32,43] can vary greatly in time and between varieties, with our experiment showing reduced values for KSC and Koretta and 2–3 times higher values for Hayanmi. The low value of this parameter indicates the ability of plants to reduce their water loss as an adaptive response to the environment. Additionally, the VPD values sustained moderate stress due to a high evapotranspiration potential, both parameters indicating the ability of the tested varieties to provide a specific response to the tested cropping climate. The assessment of both assimilation rate and stomatal conductance indicated that the three varieties tested were exposed to a medium-to-high water stress, indicating an adaptive response, and with Hayanmi presenting the most resistant characteristics [42,44].

The second type of parameters focused on stomatal characteristics (width, number, and aperture), all reported on the adaxial and abaxial sides of the leaf and at the base, middle, and tip. The length, width, and aperture are directly correlated with the rates of CO2 uptake in photosynthesis and the amount of water loss through transpiration, while the number of stomata indicates the potential for gas exchange along the leaf [45,46]. For sweet potato, recording these parameters improves the understanding of how the plants respond to environmental stressors and how effective their photosynthetic processes are [42,45]. An important aspect is the identification of stomatal characteristics on both leaf surfaces, enabling a comprehensive assessment of gas exchange, water use efficiency, and responses to environmental conditions [47,48,49].

The stomatal density is higher on the abaxial side and is important for gas exchange, while their size can vary on both sides of the leaf [46]. Stomatal aperture is an indicator of stress adaptation as it is involved in real-time gas exchange in leaves and is more responsive on the abaxial side due to exposure to stronger environmental pressures [47,50].

The third set of parameters was derived from their critical indicator values for yield and quality. Fresh biomass was recorded to assess plant vigor, photosynthetic potential, and stress tolerance, while the dry biomass was used to indicate assimilate accumulation, stress signals, and potential for storage [51,52,53]. Relative water content and chlorophyll content were used to analyze plant growth and development; higher values indicated greater drought resilience, the potential for a high tuber yield, and greater biomass [23,42,54]. The shoot number sustains vegetative growth and can increase the number and weight of tubers, whereas sugar content is an indicator of taste and nutritional value and is a marketable trait [55,56,57]. This last category of parameters is important for selecting drought-tolerant varieties and for agronomic decisions related to management and yield optimization [55,58]. Drought stress is evident in reduced photosynthetic rates, lower stomatal conductance, and reduced potential biomass production and allocation [42,59,60].

The results obtained provide insight into how the three varieties show divergent ecophysiological strategies in the tested area. The Hayanmi variety exhibited an early efficiency strategy, characterized by a higher net photosynthetic rate, early biomass accumulation, and high relative chlorophyll contents during the anthesis stage. At the leaf level, the stomatal architecture showed fewer stomata but larger ones at the leaf base, and the tuber yield maintained high sugar contents. In contrast, the KSC variety showed a high-capacity strategy, with triple biomass accumulation from anthesis to tuber formation, approximately two to three times higher compared with the other varieties. The variety increased the stomatal density in the middle and tip of the leaf by over 20% during the tuber formation phenophase, which resulted in the highest average tuber weights and yield. Koretta’s results showed a stability strategy, with intermediate values overall compared with the other varieties. It maintained stable foliage throughout the growing season and provided a reliable performance.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study showed variety-specific growth and stomatal traits, providing field validation data, which are necessary for improving current sweet potato crop models under the pressure of climate change [61]. While the current modeling techniques (e.g., AquaCrop, CROPWAT, Spotcoms, and Madhuram) are used to forecast potential yield and water consumption, their accuracy in specific areas, such as most parts of Romania, is often limited due to both geographical data gaps and abiotic factors from ecosystems [61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The results of this study directly address these limitations by providing field-extracted parameters required for continuous analysis of crop development [61]. Under these circumstances, the ecophysiological data from our study provide a basis for refining regional suitability models and simulations to improve forecast/suitability model performance by integrating climate change scenarios and identifying the potentially suitable areas for this crop [68,69,70].

Our study demonstrates that the climate in Central Romania during the growing season acts as a critical abiotic filter for sweet potato cultivation, with a mean multiannual GDD exceeding 1300 °C and relatively low-to-moderate heat stress (days with temperatures exceeding 30 °C).

The Hayanmi variety exhibited a mixed strategy of earliness and quality, with high assimilation rates and a higher chlorophyll content. The variety reaches a stable tuber weight early in the season, making it a good candidate for shorter growing seasons and early-quality yields.

Koretta was a variety with a structural stability strategy, with high adaxial stomatal features and stable foliage during the growing season. The increases in the sugar content at the end of the vegetation period suggest a resilient metabolism and an adjustment to late-summer conditions.

The KSC variety showed higher abaxial stomatal features and a triple increase in dry biomass correlated with a sevenfold increase in tuber weight during the tuber formation phenophase.

A new physiological framework can be provided for sweet potato variety selection. This approach is based on correlations between stomatal architecture and biomass accumulation, and between early and final sugar contents with tuber weight.

Although known as a thermophilic crop and specific to (inter)tropical regions, our results revealed that sweet potato can still yield successfully in the continental temperate regions despite the limited availability of high temperatures and growing degree days. A combination of soil type, fertility, climatic conditions, and cropping technology can ensure successful yields and adaptation of this new or exotic crop. Sweet potato shows promise for cultivation in Romania under the current changing climate, with the potential to improve food security. Further research is needed to assess its optimal adaptability across other regions in Romania and Southeastern Europe to ensure food security under changing climatic conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.S., A.E.C. and V.S.; methodology, V.A.S., A.E.C., A.N.P., F.C. and S.D.V.; software, V.A.S., C.H. and V.S.; validation, A.E.C., A.N.P., A.D., F.C. and S.D.V.; formal analysis, V.A.S., A.E.C., C.H., A.D. and S.D.V.; investigation, V.A.S., A.E.C. and V.S.; data curation, V.A.S. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.S., A.E.C., C.H., A.N.P., A.D., F.C., V.S. and S.D.V.; writing—review and editing, V.A.S., A.E.C., C.H., A.N.P., A.D., F.C., V.S. and S.D.V.; supervision, V.A.S., A.E.C. and V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UEFISCDI, under the project “Exploring Climate Opportunities and Assessing the Favorability of Romania’s Territory for Optimized and High-Performance Agriculture”, project code PN-IV-P7-7.1-PTE-2024-0006 (contract no. 16PTE⁄2025).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| A | Net photosynthesis or assimilation rate |

| ci | Intracellular CO2 mole fraction |

| GH2O | Stomatal conductance |

| E | Transpiration rate |

| PARbot | Photosynthetically active radiation measured with sensor in lower cuvette half |

| DiffPAR | Photosynthetically active radiation between top and bottom leaf |

| Yield | Quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport |

| ETR | Electron transport rate |

| VPD | Vapor pressure deficit between leaf and air |

| rh | Relative humidity |

| P1 | First assessed phenophase: beginning of anthesis |

| P2 | Second assessed phenophase: full flowering + 50% tuber formation |

| P3 | Third assessed phenophase: end of tuber formation–total tuber mass reached phenophase + leaves and stem bleached and dry |

| RCC | Relative chlorophyll content |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| S.adB.L | Adaxial stomata length at leaf base |

| S.abB.L | Abaxial stomata length at leaf base |

| S.adM.L | Adaxial stomata length at middle leaf |

| S.abM.L | Abaxial stomata length at middle leaf |

| S.adT.L | Adaxial stomata length at leaf tip |

| S.abT.L | Abaxial stomata length at leaf tip |

| S.adB.W | Adaxial stomata width at leaf base |

| S.abB.W | Abaxial stomata width at leaf base |

| S.adM.W | Adaxial stomata width at middle leaf |

| S.abM.W | Abaxial stomata width at middle leaf |

| S.adT.W | Adaxial stomata width at leaf tip |

| S.abT.W | Abaxial stomata width at leaf tip |

| S.adB.A | Adaxial stomata aperture at leaf base |

| S.abB.A | Abaxial stomata aperture at leaf base |

| S.adM.A | Adaxial stomata aperture at middle leaf |

| S.abM.A | Abaxial stomata aperture at middle leaf |

| S.adT.A | Adaxial stomata aperture at leaf tip |

| S.abT.A | Abaxial stomata aperture at leaf tip |

| Bx | Sugar Brix % from the sweet potato tuber—dissolved sugar content |

| TW | Tuber weight |

| Sh.no | Shoot number |

| Sh.L | Shoot length |

| F | Fresh leaf biomass |

| B | Dry leaf biomass |

| LA | Leaf area |

| AGB | Aboveground biomass |

| AVTW | Average tuber weight |

| TB | Total biomass |

| PercAGB | Aboveground biomass percent from TB |

| PercTW | Tuber biomass percent from TB |

| T.no | Sweet potato tuber number per plant as average of 20 plants |

| RSR | Root/shoot ratio |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Non-significant parameters recorded for the three assessment periods: P1–P2.

Table A1.

Non-significant parameters recorded for the three assessment periods: P1–P2.

| Parameter | Variety | Average ± s.e. | Parameter | Variety | Average ± s.e. | Parameter | Variety | Average ± s.e. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH2O | KSC | 13.27 ± 3.60 | Sh.no.P2 | KSC | 6.33 ± 1.2 | S.adB.A.P2 | KSC | 5.33 ± 0.66 |

| Koretta | 17.51 ± 3.03 | Koretta | 6.00 ± 0.57 | Koretta | 8.00 ± 0.57 | |||

| Hayanmi | 46.91 ± 18.98 | Hayanmi | 7.00 ± 1.15 | Hayanmi | 4.33 ± 0.33 | |||

| S.adT.no.P1 | KSC | 22.66 ± 2.6 | Sh_L.P2 | KSC | 74.00 ± 11.01 | S.abB.A.P2 | KSC | 6.00 ± 1.15 |

| Koretta | 24.33 ± 2.4 | Koretta | 66.66 ± 7.68 | Koretta | 5.00 ± 0.57 | |||

| Hayanmi | 24.00 ± 1.15 | Hayanmi | 82.66 ± 5.78 | Hayanmi | 4.66 ± 0.33 | |||

| S.abT.no.P1 | KSC | 61.66 ± 2.33 | Brix.P2 | KSC | 11.10 ± 0.98 | S.adM.A.P2 | KSC | 4.66 ± 0.66 |

| Koretta | 60.00 ± 0.57 | Koretta | 10.44 ± 1.45 | Koretta | 6.33 ± 0.88 | |||

| Hayanmi | 58.00 ± 4.50 | Hayanmi | 9.26 ± 1.78 | Hayanmi | 6.00 ± 1.15 | |||

| S.abB.L.P1 | KSC | 47.00 ± 2.08 | TW.P2 | KSC | 168.33 ± 29.05 | S.adT.A.P2 | KSC | 5.66 ± 0.66 |

| Koretta | 41.00 ± 0.57 | Koretta | 143.33 ± 52.62 | Koretta | 6.66 ± 0.88 | |||

| Hayanmi | 46.33 ± 0.33 | Hayanmi | 406.16 ± 177.33 | Hayanmi | 7.33 ± 1.76 | |||

| S.abT.L.P1 | KSC | 45.66 ± 2.33 | F.P2 | KSC | 3.93 ± 0.32 | S.abT.A.P2 | KSC | 5.00 ± 0.00 |

| Koretta | 51.00 ± 3.78 | Koretta | 3.38 ± 0.16 | Koretta | 5.00 ± 0.57 | |||

| Hayanmi | 44.00 ± 1.00 | Hayanmi | 3.58 ± 0.45 | Hayanmi | 6.00 ± 0.57 | |||

| S.abB.W.P1 | KSC | 50.00 ± 1.00 | D.P2 | KSC | 0.68 ± 0.05 | LA.P2 | KSC | 105.09 ± 4.18 |

| Koretta | 55.00 ± 1.52 | Koretta | 0.56 ± 0.01 | Koretta | 117.54 ± 12.92 | |||

| Hayanmi | 45.00 ± 3.05 | Hayanmi | 0.59 ± 0.05 | Hayanmi | 109.15 ± 9.31 | |||

| S.adM.W.P1 | KSC | 49.33 ± 2.18 | RWC.P2 | KSC | 0.84 ± 0.00 | AGB_P2 | KSC | 1526.66 ± 551.22 |

| Koretta | 51.66 ± 1.33 | Koretta | 0.78 ± 0.08 | Koretta | 1371.66 ± 552.88 | |||

| Hayanmi | 55.33 ± 3.84 | Hayanmi | 0.85 ± 0.01 | Hayanmi | 670 ± 47.25 | |||

| S.abM.W.P1 | KSC | 49.66 ± 3.52 | RCC.P2 | KSC | 506.22 ± 31.67 | T.noP2 | KSC | 7.00 ± 0.57 |

| Koretta | 54.33 ± 2.02 | Koretta | 480.22 ± 19.25 | Koretta | 5.00 ± 0.57 | |||

| Hayanmi | 50.66 ± 2.33 | Hayanmi | 461.32 ± 34.53 | Hayanmi | 6.66 ± 0.88 | |||

| S.adT.W.P1 | KSC | 46.33 ± 3.71 | S.adM.L.P2 | KSC | 25.00 ± 3.05 | |||

| Koretta | 56.66 ± 2.33 | Koretta | 27.66 ± 3.17 | T.no | KSC | 7.42 ± 0.81 | ||

| Hayanmi | 50.66 ± 2.60 | Hayanmi | 30.66 ± 1.33 | Koretta | 6.42 ± 1.04 | |||

| S.abT.W.P1 | KSC | 48.66 ± 2.40 | S.abM.L.P2 | KSC | 36.33 ± 1.45 | Hayanmi | 5.71 ± 0.60 | |

| Koretta | 53.00 ± 1.00 | Koretta | 32.00 ± 4.16 | RSR | KSC | 0.94 ± 0.20 | ||

| Hayanmi | 51.66 ± 1.66 | Hayanmi | 42.33 ± 3.17 | Koretta | 0.64 ± 0.09 | |||

| S.adM.A.P1 | KSC | 9.00 ± 0.57 | S.adT.L.P2 | KSC | 30.66 ± 2.18 | Hayanmi | 0.82 ± 0.15 | |

| Koretta | 9.00 ± 1.15 | Koretta | 33.66 ± 0.88 | PercAGB | KSC | 55.35 ± 5.96 | ||

| Hayanmi | 9.33 ± 0.88 | Hayanmi | 32.00 ± 1.52 | Koretta | 62.27 ± 3.70 | |||

| S.abT.A.P1 | KSC | 9.66 ± 0.88 | S.adM.W.P2 | KSC | 31.00 ± 2.51 | Hayanmi | 57.23 ± 4.90 | |

| Koretta | 9.00 ± 1.00 | Koretta | 38.00 ± 1.52 | PercTW | KSC | 44.64 ± 5.96 | ||

| Hayanmi | 7.00 ± 1.15 | Hayanmi | 33.66 ± 2.33 | Koretta | 37.72 ± 3.70 | |||

| LA.P1 | KSC | 71.34 ± 1.58 | S.adT.W.P2 | KSC | 34.00 ± 2.08 | Hayanmi | 42.76 ± 4.90 | |

| Koretta | 60.94 ± 1.22 | Koretta | 37.00 ± 3.21 | |||||

| Hayanmi | 69.93 ± 4.47 | Hayanmi | 29.66 ± 1.2 |

Note: Values represent averages and SE (standard error); yellow color highlight parameters measured in phenophase P1—flowering; green color highlight parameters measured in phenophase P2—50% tuber formation; and blue color represents measured parameters from phenophase P3—senescence.

Figure A1.

Correlations between photosynthetic parameters of sweet potato varieties at the beginning of the flowering stage. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01, ***—p < 0.001.

Figure A2.

Koretta sweet potato: abaxial and adaxial stomata from fresh leaves, magnified 20×.

Figure A3.

Hayanmi sweet potato: abaxial and adaxial stomata from fresh leaves, magnified 20×.

Figure A4.

KSC sweet potato: abaxial and adaxial stomata from fresh leaves, magnified 20×.

Figure A5.

Correlations between fresh and dry biomass of sweet potato varieties in the phenophase of flowering and 50% tuber formation. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.01.

Figure A6.

Correlations between the sugar content of sweet potato varieties at 50% tuber formation and in the total tuber mass reached phenophase.

Figure A7.

Correlations between aboveground and belowground biomass at the end of the growth season for each variety. In the correlation chart: *—p < 0.05, ***—p < 0.001.

References

- Pati, K.; Kaliyappan, R.; Giri, A.K.; Chauhan, V.B.S.; Gowda, H.; Arutselvan, R.; Laxminarayana, K. Phenological Growth Stages of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam.) According to the Extended BBCH Scale. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2024, 184, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. Sustainable Development Goals. In Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility: Climate Change; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cartabiano-Leite, C.E.; Porcu, O.M.; Casas, A.F. Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam) Nutritional Potential and Social Relevance: A Review. History 2020, 11, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Burbano-Erazo, E.; Cordero, C.; Pastrana, I.; Espitia, L.; Gómez, E.; Morales, A.; Pérez, J.; López, L.; Rosero, A. Interrelation of Ecophysiological and Morpho-Agronomic Parameters in Low Altitude Evaluation of Selected Ecotypes of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas [L. Lam.). Horticulturae 2020, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xu, G.; Li, D.; Jin, G.; Liu, S.; Clements, D.R.; Zhu, X. Ipomoea batatas (Sweet Potato), a Promising Replacement Control Crop for the Invasive Alien Plant Ageratina Adenophora (Asteraceae) in China. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2019, 10, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Pacenka, S.; Gao, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, G.; Steenhuis, T.S. Effect of Diversified Crop Rotations on Groundwater Levels and Crop Water Productivity in the North China Plain. J. Hydrol. 2015, 522, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agili, S.; Nyende, B.; Ngamau, K.; Masinde, P. Selection, Yield Evaluation, Drought Tolerance Indices of Orange-Flesh Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam) Hybrid Clone. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo, R.; Asseng, S.; Cammarano, D.; Quiroz, R. Potato, Sweet Potato, and Yam Models for Climate Change: A Review. Field Crops Res. 2014, 166, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motsa, N.M.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) as a Drought Tolerant and Food Security Crop. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2015, 111, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Nie, S.; Zhu, F. Chemical Constituents and Health Effects of Sweet Potato. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvik, B.; Neuffer, B.; Pacini, G. Efficacy of Ipomoea batatas (Caiapo) on Diabetes Control in Type 2 Diabetic Subjects Treated with Diet. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, A.; Paraschiv, A.N.; Drăghici, R.; Croitoru, M.; Dima, M. Sweet potato, a perspective crop for the sandy soil area in Romania. Lucr. Ştiinţifice USAMV Iaşi Ser. Agron. 2018, 61, 169–174. Available online: https://repository.iuls.ro/xmlui/handle/20.500.12811/528 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Purcaru, I. O Expeditie in “Sahara Olteana”; SITECH: Craiova, Romania, 2018; ISBN 978-606-11-6380-9. [Google Scholar]

- Diaconu, A.; Draghici, R.; Croitoru, M.; Draghici, I.; Dima, M.; Paraschiv, A.N.; Coteț, G. Dynamics of the Production Process of Sweet Potato Cultivated in the Sandy Soil Conditions in Romania. Pak. J. Bot. 2019, 51, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Soare, R. Researches on the Sweet Potato (Ipomea batatas L.) Behaviour under the Soil and Climatic Conditions of the South-West of Romania. J. Hortic. For. Biotechnol. 2015, 19, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Drăghici, R.; Diaconu, A.; Paraschiv, A.; Drăghici, I.; Coteț, G.; Croitoru, M.; Dima, M. Research on Obtaining Biological Planting Material for Sweet Potatoes Under Conditions in Romania. In “Agriculture for Life, Life for Agriculture” Conference Proceedings; Sciendo: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Revelle, W. R Package, version 2.4.12. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- de Mendiburu, F. R Package, version 1.3-7. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. Comprehensive R Archive Network: Online, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Robinson, D.; Hayes, A.; Couch, S. R Package, version 1.0.7. Broom: Convert Statistical Objects into Tidy Tibbles. Comprehensive R Archive Network: Online, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=broom (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Harrell, F., Jr. R Package, version 5.2-2. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. Comprehensive R Archive Network: Online, 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package, Version 0.95. ‘Corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. Comprehensive R Archive Network: Online, 2024. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Andrade, A.; Henschel, J.; Araújo, D.; Gomes, D.; Silva, T.; Soares, V.; Dantas, E.; Lopes, A.; Júnior, A.; Zeist, A.; et al. Selection of Biofortified Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Genotypes in Response to Drought Stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapakhova, Z.; Raissova, N.; Daurov, D.; Zhapar, K.; Daurova, A.; Zhigailov, A.; Zhambakin, K.; Shamekova, M. Sweet Potato as a Key Crop for Food Security under the Conditions of Global Climate Change: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, C.; Kalaivani, R. Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.): Climate Resilient Crop for Food Security in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions—A Review. Indian J. Arid. Hortic. 2025, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbayaki, C.; Karuku, G. Predicting Impact of Climate Change on Water Requirements for Directly Sown Rain-Fed Sweet Potato in the Semi-Arid Katumani Region, Kenya. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2021, 24, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taduri, S.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Wijewardana, C.; Lone, A.A.; Meyers, S.L.; Shankle, M.; Gao, W.; Reddy, K.R. Sweetpotato Cultivars Responses to Interactive Effects of Warming, Drought, and Elevated Carbon Dioxide. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1080125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Ma, P.; Jia, Z.; Rodríguez, D.; Vargas, I.J.P.; Ventura, V.; Efraín González, J.; Portal, O.; Diaz, F.; Parrado Alvarez, O.; et al. Evolution of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.) Breeding in Cuba. Plants 2025, 14, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merga, M.; Mourtala, I.; Abtew, W.; Oselebe, H. Genetic diversity and nutritional analysis of sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] genotypes in Abakaliki, Nigeria. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kännaste, A.; Zekker, I.; Tosens, T.; Kübarsepp, L.; Runno-Paurson, E.; Niinemets, Ü. Productivity of the Warm-Climate Crop Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) in Northern Latitudes. Zemdirb. Agric. 2023, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, T.; Marótiné Tóth, K.; Táborosiné Ábrahám, Z.; Bráj, R.; Adu Donyina, G.; Bordé, Á.; Somogyi, N.; Szarvas, A. A Tropical Crop, as Hungarian Farmers’ Potential Response to Climate Change—The Sweet Potato. Acta Hortic. 2025, 1422_13, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, M.; Diaconu, A.; Drăghici, R.; Dima, M.; Coteț, G. The Influence of Climate Change on the Quality of the Sweet Potatoes Grown on Sandy Soils in Southwestern Oltenia. Muzeul Olten. Craiova. Oltenia. Stud. Comunicări. Ştiinţele Nat. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Drăghici, E.M.; Dobrin, E.; Chira, A.; Chira, L.; Bălan, D.; Luță, G. Study Regarding the Influence of Some Technological Factors on The Quality of Sweet Potato Planting Material. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2024, 68, 559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Cioloca, M.; Tican, A.; Bǎdãrǎu, C.; Bǎrǎscu, N.; Popa, M. In Vitro Medium Term Conservation of Sweet Potato Genotypes Using Mannitol and Sorbitol. Rom. Agric. Res. 2021, 38, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Diaconu, A.; Drăghici, R.; Cioloca, M.; Boiu Sicuia, O.; Mohora, A.; Croitoru, M.; Paraschiv, A.; Draghici, I.; Dima, M.; Coteț, G. Ghid de Bune Practici Agricole si de Mediu in Domeniul Optimizarii Tehnologiei de Cultivare a Cartofului Dulce; SITECH: Craiova, Romania, 2018; ISBN 978-606-11-6626-8. Available online: https://www.scdcpndabuleni.ro/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Diaconu, A.; Cho Eun-Gi, C.E.; Drăgici, R.; Croitoru, M.; Ploae, M.; Drăghici, I.; Dima, M. The Behavior of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) in Terms Psamosoils in Southern Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2016, 60, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Coteț, G.; Diaconu, A.; Nanu, Ștefan; Paraschiv, N.-A.; Dima, M.; Mitrea, R. Research on the Behavior of Some Sweet Potato Genotypes Cultivated on the Sandy Soils of Southern Romania. Sci. Papers. Ser. B Hortic. 2023, 68, 566–571. [Google Scholar]

- ISTIS CATALOG OFICIAL 2024. Available online: https://istis.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ISTIS-CATALOG-OFICIAL-2024.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- He, J.; Qin, L. Growth and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) Leaves Grown under Natural Sunlight with Supplemental LED Lighting in a Tropical Greenhouse. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 252, 153239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Wong, S.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; Weng, J. Photosystem II Efficiency in Response to Diurnal and Seasonal Variations in Photon Flux Density and Air Temperature for Green, Yellow-Green, and Purple-Leaved Cultivars of Sweet Potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam]. Photosynthetica 2024, 62, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, H. Photosynthesis Product Allocation and Yield in Sweet Potato in Response to Different Late-Season Irrigation Levels. Plants 2023, 12, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Effects of Drought Stress on Photosynthetic Characteristics and Endogenous Hormone Levels in the Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanayake, B.; Reddy, K.R.; Shankle, M.W.; Arancibia, R.A. Growth, Developmental, and Physiological Responses of Two Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.[Lam]) Cultivars to Early Season Soil Moisture Deficit. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 168, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrewold, S.E.; Gurmu, F.; Haile, A.; Roro, A.G. Screening Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Varieties for Moisture Stress Tolerance Based on Morpho-Physiological Traits. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 353, 114472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampe, H.; Umboh, S.; Siahaan, R.; Maabuat, P. Anatomical Characteristics of Stomata, Mesophyll and Petiole of Six Varieties Sweet Potatoes (Ipomoea batatas L.) after Organic Fertilizer Induction. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanourakis, D.; Giday, H.; Milla, R.; Pieruschka, R.; Kjaer, K.; Bolger, M.; Vasilevski, A.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fiorani, F.; Ottosen, C. Pore Size Regulates Operating Stomatal Conductance, While Stomatal Densities Drive the Partitioning of Conductance between Leaf Sides. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Hu, K.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Guard Cells on the Adaxial and Abaxial Leaf Surfaces Use Different Compositions of Potassium Ion Channels to Drive Light-Induced Stomatal Opening. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, S.; Lemonnier, P.; Milliken, A.; Davey, P.; Lawson, T. Simultaneous and Independent Abaxial and Adaxial Gas Exchange Measurements. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2790, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, M.; Marino, G.; Loreto, F.; Centritto, M. Integrating Stomatal Physiology and Morphology: Evolution of Stomatal Control and Development of Future Crops. Oecologia 2021, 197, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Nie, N.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; He, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhai, H. A Novel WRKY Transcription Factor from Ipomoea trifida, ItfWRKY70, Confers Drought Tolerance in Sweet Potato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, C.; Ganança, J.; Nóbrega, H.; Freitas, J.; Lebot, V.; Carvalho, M. Drought Avoidance and Phenotypic Flexibility of Sweet Potato. (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) Under Water Scarcity Conditions. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, P.; Thangamani, C.; Pugalendhi, L.; Swarnapriya, R.; Meenakshi, P. Studies on Evaluation of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) Genotypes for High Tuber Yield and Quality. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, P.; Tripathi, K.; Gautam, D.; Shrestha, A. Effect of Crop Geometry on Growth, Yield and Quality of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Genotypes. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Tan, W.; Deng, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Shen, J.; Liu, N. Investigating the Mechanisms of Hyperspectral Remote Sensing for Belowground Yield Traits in Potato Plants. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Babeanu, C.; Hoza, G.; Sima, R.; Soare, R. Nutraceutical Value and Production of the Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Cultivated in South-West of Romania. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y. Comparison of Quality Characteristics among 20 Sweet Potato Varieties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitompul, S.; Nawawi, H.; Arifin, N. Growth and Yield of Eight Sweet Potato Accessions in Red Yellow Podsolic Soil. Braz. J. Dev. 2024, 10, e76198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, C.; Ganança, J.; Lebot, V.; Carvalho, M. Changes in Oxalate Composition and Other Nutritive Traits in Root Tubers and Shoots of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam.]) under water stress. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 100, 1702–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Gou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, M.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Deng, S.; Du, K.; Lv, C.; Tang, D.; et al. Effects of Different Temperatures on the Physiological Characteristics of Sweet Potato. Plants 2025, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pazos, J.; Rosero, A.; Martínez, R.; Pérez, J.; Morelo, J.; Araujo, H.; Burbano-Erazo, E. Influence of Morpho-Physiological Traits on Root Yield in Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) Genotypes and Its Adaptation in a Sub-Humid Environment. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 275, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekanmbi, T.; Wang, X.; Basheer, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, A.; Cheng, H. Climate Change Impacts on Global Potato Yields: A Review. Environ. Res. Clim. 2023, 3, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Reddy, G.V.P.; Wadl, P.A.; Rutter, W.; Culbreath, J.; Lau, P.W.; Rashid, T.; Allan, M.C.; Johaningsmeier, S.D.; Nelson, A.M.; et al. Sustainable Sweetpotato Production in the United States: Current Status, Challenges, and Opportunities. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 630–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaro, G.P.; Tsehaye, Y.; Girma, A.; Rubangakene, D. The Impact of Future Climate on Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato Production in Arid Areas of Northern Ethiopia. A Case Study in Afar Region. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Sun, W.; Chen, D.; Qing, Y.; Xing, J.; Yang, R. Early Sweet Potato Plant Detection Method Based on YOLOv8s (ESPPD-YOLO): A Model for Early Sweet Potato Plant Detection in a Complex Field Environment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, K.; Mithra, V.S. MADHURAM: A Simulation Model for Sweet Potato Growth. World J. Agric. Sci. India 2008, 4, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mithra, V.S.; Somasundaram, K. A Model to Simulate Sweet Potato Growth. World Appl. Sci. J. 2008, 4, 568–577. [Google Scholar]

- Okoro, E.O.; Okwu-Delunzu, V.U.; Enete, I.C. Water Requirements, and Irrigation Schedules of Sweet Potato in Agbani, Enugu State, Nigeria. Afr. Res. J. Environ. 2019, 2, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, E.C.; Silva Do Sacramento, J.A.A.; Taube, P.S.; Gasparin, E.; Cotta Dângelo, R.A.; Silva Santos, E.; Paixão, G.P. Risk of Climate Change to Sweet Potato Cultivation in the American Continent. J. Crop Improv. 2024, 38, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, R.; VS, S.M.; Gangadharan, B. Future Climate Suitability of Underutilized Tropical Tuber Crops-’Aroids’ in India. J. Agrometeorol. 2023, 25, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, R.; Gangadharan, B. Climate Resilience, Yield and Geographical Suitability of Sweet Potato under the Changing Climate: A Review. Nat. Resour. Forum 2024, 48, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.