Overexpression of the SlPti4 Transcription Factor in Transgenic Tobacco Plants Confers Tolerance to Saline, Osmotic, and Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Petit Havana SR1 In Vitro Germination

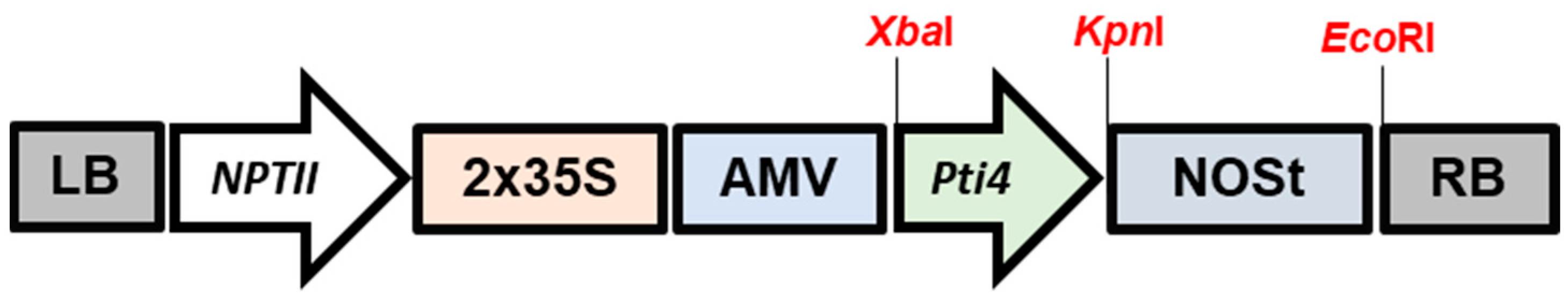

2.2. Construction of Transformation Vectors

2.3. Genetic Transformation of N. tabacum L. cv. Petit Havana Mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404

2.4. Molecular Analysis of Transgenic Tobacco Lines

2.5. Regeneration of the Transgenic Lines and Generation of a Homozygous Line of N. tabacum L. cv. Petit Havana

2.6. Semiquantitative Expression Analysis (RT-PCR) of the Pti4 Transgene

2.7. Tolerance Analysis Under Abiotic Stress Conditions (Salinity and Drought)

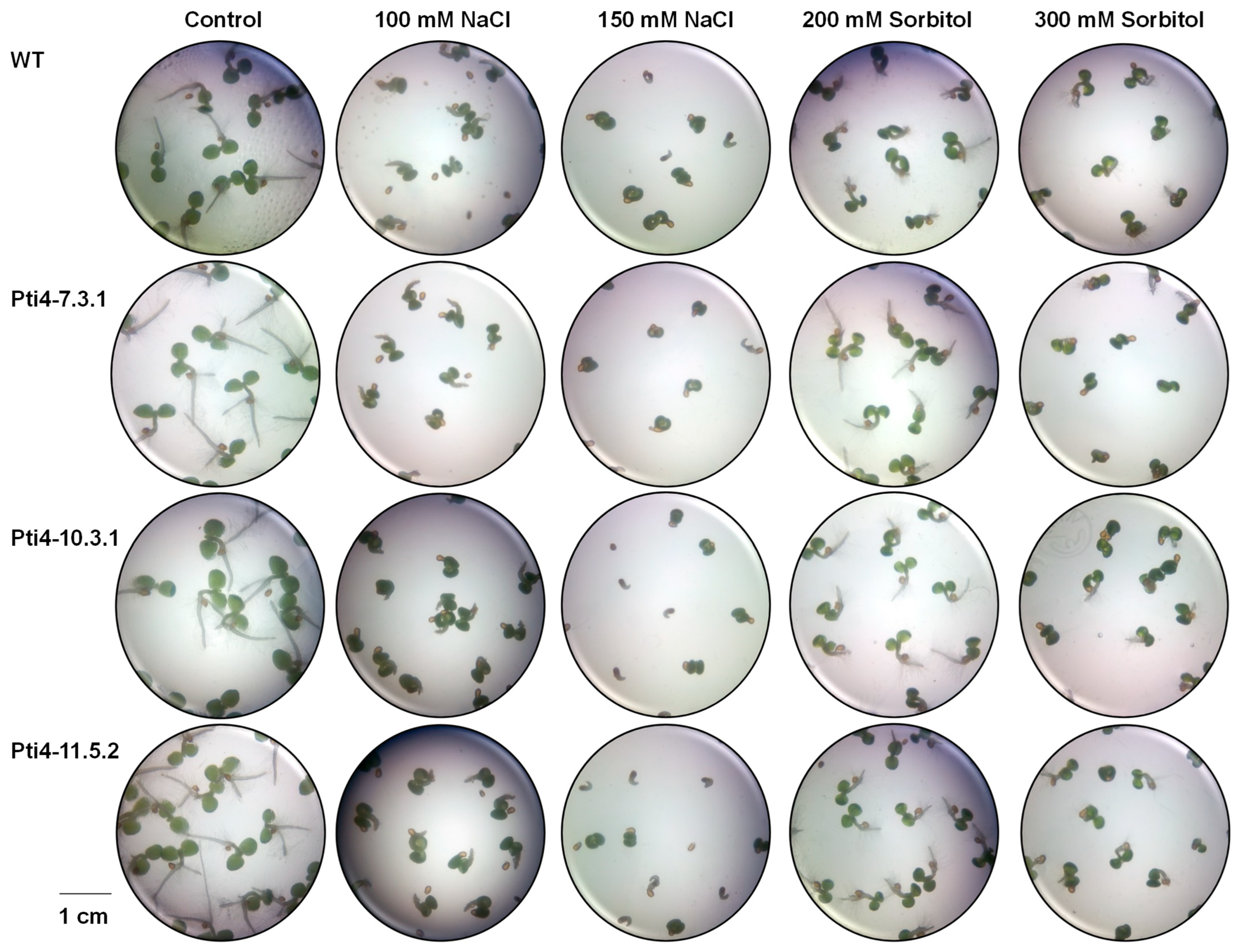

2.7.1. Evaluation of Stress Tolerance During Tobacco Seed Germination

2.7.2. Effect of Stress Tolerance in Tobacco Plants

2.7.3. Stress Indicator Parameters

2.7.4. Determination of Photoinhibition and the Electron Transport Index in Tobacco Plants

2.7.5. Quantification of Chlorophyll (Chl) Content in Tobacco Plants

2.7.6. Quantification of Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content in Tobacco Plants

2.7.7. Determination of Biomass in Tobacco Plants

2.7.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

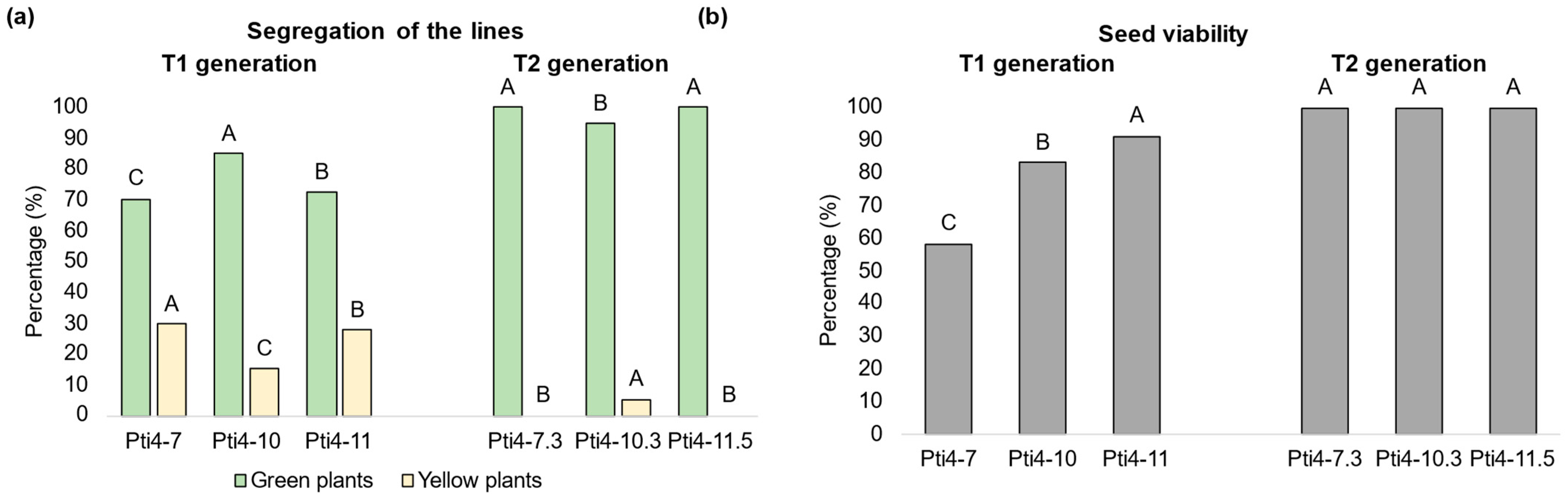

3.1. Generation of Homozygous Transgenic Tobacco Lines

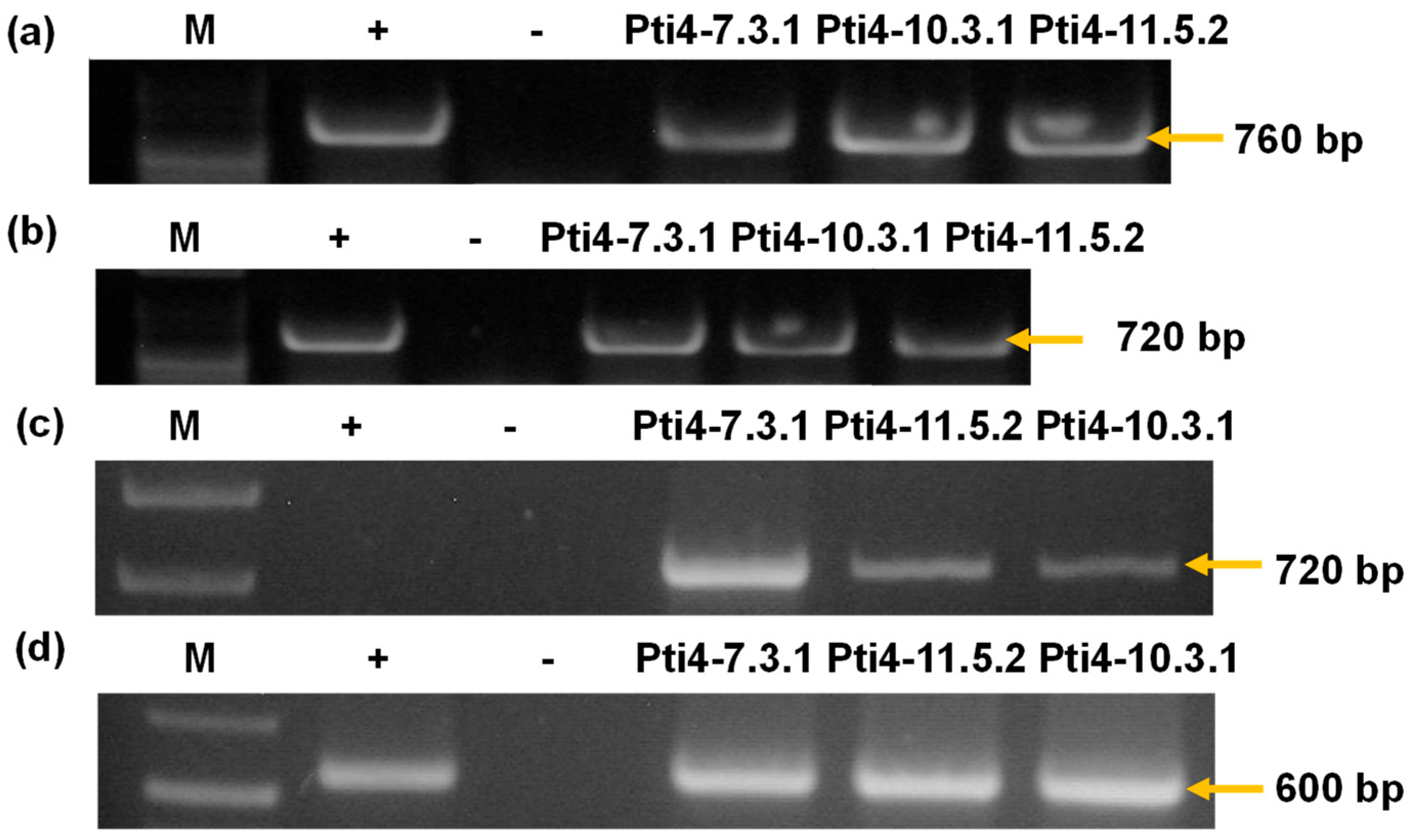

3.2. Molecular Analysis and Regeneration of Homozygous Transgenic Tobacco Lines

3.3. Semiquantitative Expression Analysis of the Gene of Interest Pti4

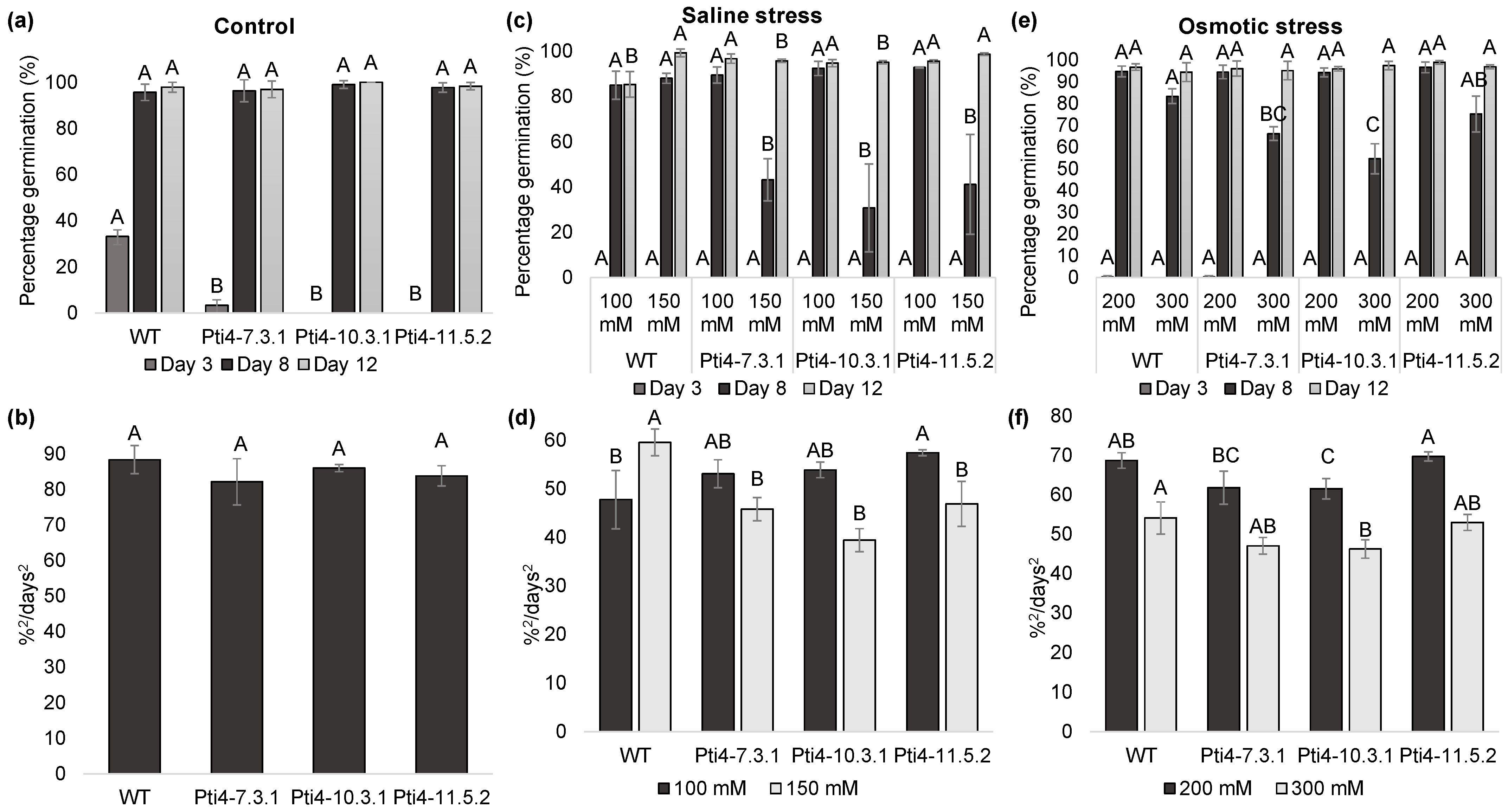

3.4. Effect of Tolerance to Abiotic Stress on Tobacco Seeds

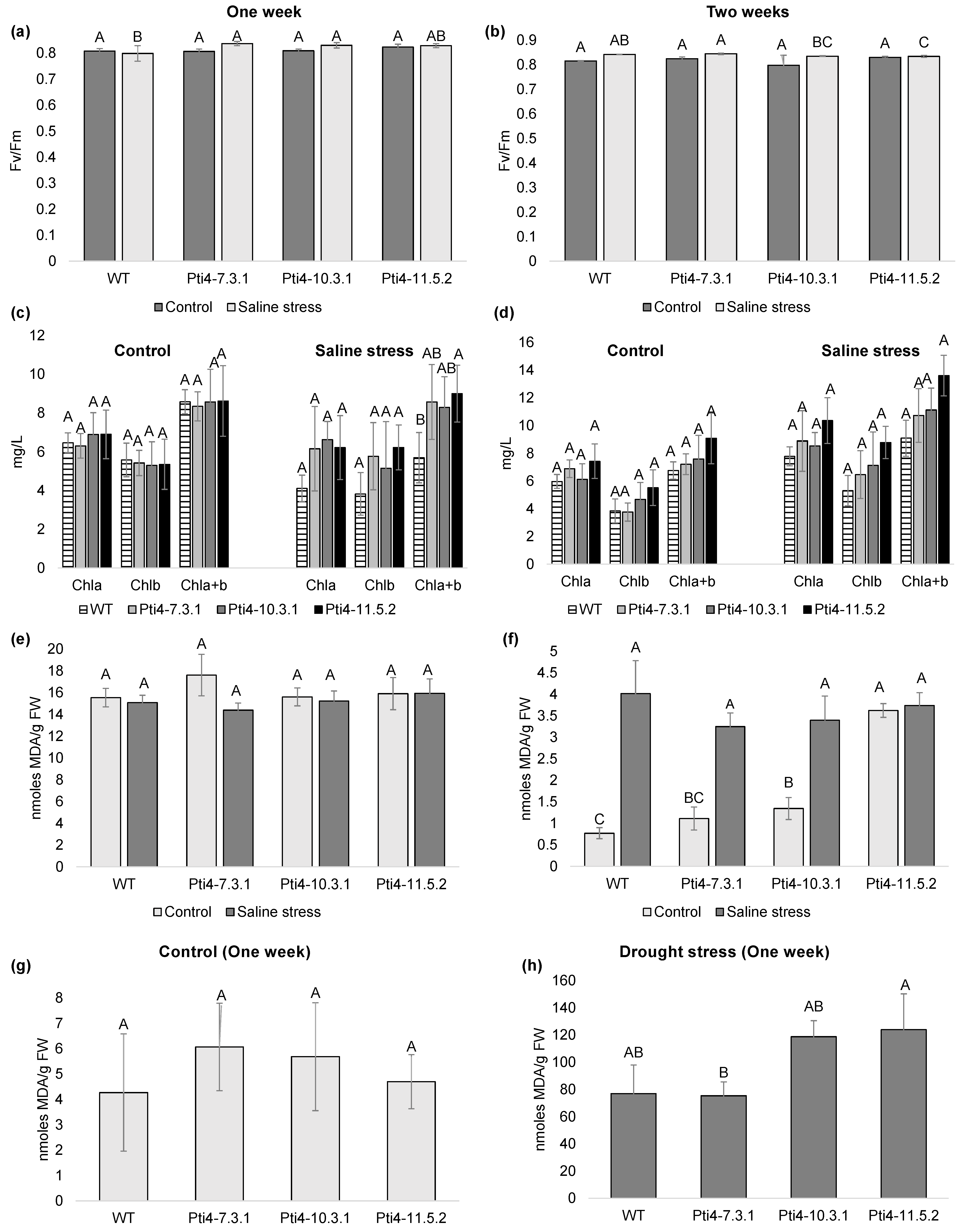

3.5. Effect of Tolerance to Abiotic Stress in Tobacco Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TF | Transcription factors |

| AP2/ERF | APETALA2/Ethylene Response Factor |

| PR | Genes related to pathogenesis |

| ERF | Ethylene-responsive factor |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| ET | Ethylene |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| ADM | Average daily germination |

| VM | Maximum germination value |

| PG | Germination percentage based on radicle emergence |

| VG | Value of germination vigor or germination speed |

| Fm | Fluorescence under light conditions |

| Fv | Variable fluorescence |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

References

- Madhava, R.K.V.; Raghavendra, A.S.; Janardhan Reddy, K. (Eds.) Physiology and Molecular Biology of Stress Tolerance in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.T.; Ma, S.L.; Bai, L.P.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Jia, P.; Liu, J.; Zhong, M.; Guo, Z.F. Signal transduction during cold, salt, and drought stresses in plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 969–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Nizam, S.; Verma, P.K. Biotic and abiotic stress signaling in plants. In Stress Signaling in Plants: Genomics and Proteomics Perspective; Sarwat, M., Ahmad, A., Abdin, M.Z., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Gómez, S. Abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. In Molecular Stress Physiology of Plants; Ranjan, G.R., Bandhu, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoliu, V.A. Respuesta Fisiológica de Cítricos Sometidos a Condiciones de Estrés Biótico y Abiótico. Aspectos Comunes y Específicos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Jaume I de Castellón, Escuela Superior de Tecnología y Ciencias Experimentales, Castellón de la Plana, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Reséndez, A.; Carda-Mendoza, V.; Reyes-Carrillo, J.L.; Vásquez-Arroyo, J.; Cano-Ríos, P. Rizobacterias promotoras del crecimiento vegetal: Una alternativa de biofertilización para la agricultura sustentable. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2018, 20, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Cote, R.; Gavilanes-Ruiz, M.; Cruz-Ortega, R.; Huante, P. Importancia agrobiotenológica de la enzima ACC desaminasa en rizobacterias, una revisión. Rev. Filotec. Mex. 2013, 36, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.S.; Chen, M.; Li, L.C.; Ma, Y.Z. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, S.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Herrera-Cabrera, É.B. Factores de transcripción involucrados en respuestas moleculares de las plantas al estrés osmótico. Rev. Filotec. Mex. 2013, 36, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Mahmood, T. Functional role of DREB and ERF transcription factors: Regulating stress-responsive network in plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Tian, L.; Hollingworth, J.; Brown, D.C.W.; Miki, B. Functional Analysis of Tomato Pti4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Guo, Z.H.; Hao, P.P.; Wang, G.M.; Jin, Z.M.; Zhang, S.L. Multiple regulatory roles of AP2/ERF transcription factor in angiosperm. Bot. Stud. 2017, 58, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrello, J.; Prasad, B.N.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Mila, I.; Zouine, M.; Latché, A.; Bouzayen, M. Functional analysis and binding affinity of tomato ethylene response factors provide insight on the molecular bases of plant differential responses to ethylene. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, L.; Latoszek-Green, M.; Brown, D.; Wu, K. Arabidopsis ERF4 is a transcriptional repressor capable of modulating ethylene and abscisic acid responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 58, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrello, J.; Jaimes-Miranda, F.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Tournier, B.; Khalil-Ahmad, Q.; Regar, F.; Latché, A.; Pech, J.C.; Bouzayen, M. Sl-ERF2, a tomato ethylene response factor involved in ethylene response and seed germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 54, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhou, Y.; Gross, R.; Xu, H.; et al. Overexpression of Pti4, Pti5, and Pti6 in tomato promote plant defense and fruit ripening. Plant Sci. 2021, 302, 110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.W.; Shao, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, A.J.; Xu, W.Q.; Wu, K.J.; Lou, Y.B.; Zhu, B.Z. Overexpression of SlERF1 tomato gene encoding an ERF-type transcription activator enhancer salt tolerance. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 58, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisha, V.; Dampanaboina, L.; Vadassery, J.; Mithöfer, A.; Kappara, S.; Ramanan, R. Overexpression of an AP2/ERF type transcription factor OsEREBP1 confers biotic and abiotic stress tolerance in rice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Molina, A. Ethylene response factor 1 mediates Arabidopsis resistance to the soilborne fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Platt-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.Q.; Yang, C.; Wildermuth, M.C.; Chakravarthy, S.; Loh, Y.T.; Yang, C.; He, X.; Han, Y.; Martin, G.B. Tomato Transcription Factors Pti4, Pti5, and Pti6 Activate Defense Responses When Expressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thara, V.K.; Tang, X.; Gu, Y.Q.; Martin, G.B.; Zhou, J.M. Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato induces the expression of tomato EREBP-like genes Pti4 and Pti45 independent of ethylene, salicylate and jasmonate. Plant J. 1999, 20, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthy, S.; Tuori, R.P.; D’Ascenzo, M.D.; Fobert, P.R.; Després, C.; Martin, G.B. The tomato transcription factor Pti4 regulates defense-related gene expression via GCC box and non-GCC box cis elements. Plant Cell 2013, 15, 3033–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tang, X.; Martin, G.B. The Pto kinase conferring resistance to tomato bacterial speck disease interacts with proteins that bind a cis-element of pathogenesis-related genes. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3207–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.; Chan, A.; Daly, M.; McPherson, J. Duplication of CaMV 35S promoter sequences creates a strong enhancer for plant genes. Science 1987, 236, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, G.C.; Flores-Vergara, M.A.; Krasnyanski, S.; Kumar, S.; Thompson, W.F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, N.K.; Ditterline, R.L.; Stout, R.G. Polymerase chain reaction used for monitoring multiple gene integration in Agrobacterium mediated transformation. Crop Sci. 1991, 31, 1686–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passricha, N.; Saifi, S.; Khatodia, S.; Tuteja, N. Assessing zygosity in progeny of transgenic plants: Current methods and perspectives. J. Biol. Methods 2016, 3, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.M.B. Uso de un Nuevo vector de transformación para incrementar la acumulación de trehalosa en Nicotiana tabacum. Bachelor’s Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Texta, M.G.; Ramírez-Trujillo, J.A.; Dantán-González, E.; Ramírez-Yáñez, M.; Suárez-Rodríguez, R. Endophytic Bacteria from the Desiccation-Tolerant Plant Selaginella lepidophylla and Their Potential as Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo, R.; Maldonado, R.; Ariza, D. Fluorescencia de la clorofila en cinco procedencias de Pinus halepenesis mil y su respuesta a estrés hídrico. Cuad. Soc. Esp. Cie. For. 2004, 17, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.A. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophyll a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 603, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Rinderle, U. The role of chlorophyll fluorescence in the detection of stress conditions in plants. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1988, 19, S29–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janero, D.R. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as diagnostic indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1990, 9, 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buegue, J.A.; Aust, S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 2, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoa, W.; Wang, L.; Zhou, B.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Jiang, T. Over-expression of poplar transcription factor ERF76 gene confers salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 198, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, A.E.; Bailey, S.J.; Weretilnyk, E. Responses to abiotic stresses. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2nd ed.; Buchanan, B., Gruissem, W., Jones, R.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Pondicherry, India, 2000; pp. 1158–1202. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa, R.; Acuña, R.; Acurio, K.; Castillo, A.; Cepeda, C.; Chavarry, C.; Correa, M.; de la Cruz, L.; García, M.; Huamaní, M.; et al. Respuestas fisiológicas de Hibiscos rosa-sinensis L. (Malvácea) en el cerro “El Agustino”, Lima, Perú. Biologist 2011, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto, S.M.; Núñez, B.A.; Pérez, L.R.R.; Hernández, R.O.A. Fisiología del estrés ambiental en plantas. Synthesis 2008, 48, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, H.-B.; Chu, L.Y.; Jaleei, C.A.; Zhao, C.X. Wáter-deficit stress-induced anatomical changes in higher plants. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2008, 333, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gómez, T.B.; Ramírez-Trujillo, J.A.; Ramírez-Yáñez, M.; Suárez-Rodríguez, R. Overexpression of SlERF3b and SlERF5 in transgenic tomato alters fruit size, number of seeds and promotes early flowering, tolerance to abiotic stress and resistance to Botrytis cinerea infection. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 179, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Q.; Yang, C.; Thara, V.K.; Zhou, J.; Martin, G.B. Pti4 is induced by ethylene and salicylic acid, and its product is phosphorylated by the Pto kinase. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfey, P.N.; Ren, L.; Chua, N.H. Tissue-specific expression from CaMV 35S enhancer subdomains in early stages of plant development. EMBO J. 1990, 9, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.; Covey, S.N.; Dale, P. Genetically modified plants and the 35S promoter: Assessing the risks and enhancing the debate. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2000, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zapata, P.J.; Serrano, M.; Pretel, M.T.; Amorós, A.; Botella, M.Á. Polyamines and ethylene changes during germination of different plant species under salinity. Plant Sci. 2004, 167, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, A.; Andrade, A.; Masciarelli, O.; Alemano, S.; Luna, V. Drought and salinity alter endogenous hormonal profiles at the seed germination phase. Seed Sci. Res. 2016, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaso, S.F.; Martínez, G.J.L.; Planelló, C.M. Hormonas vegetales: Desarrollo y respuesta de las plantas con flor al ambiente. In Fundamentos Básicos de Fisiología Vegetal y Animal; Martín, M.R., Martín, E., Eds.; Pearson Educación, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers, B.J.W.; Schuurmans, J.A.M.J.; Smeekens, S.C.M. Glucose delays seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2004, 218, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, H.M. Respuestas ecofisiológicas de plantas en ecosistemas de zonas con clima mediterráneo y ambientes de alta montaña. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2002, 75, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, A.; Ghanem, M.E.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Acosta, M.; Sánchez-Bravo, J.; Martínez, V.; Lutts, S.; Dodd, I.C.; Pérez-Alfocea, F. Hormonal changes in relation to biomass partitioning and shoot growth impairment in salinized tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 4119–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, A.K.; Maheswari, M.; Yadav, S.K.; Desai, S.; Bhanu, D.; Attal, N.B.; Venkateswarlu, B. Drought stress response in crops. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2014, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Harris, P.J.C. Photosynthesis under stressful environments: An overview. Photosynthetica 2013, 51, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valpuesta, V.; Berteli, F.; Pérez-Prat, E.; Corrales, E.; Narasimham, M.; Botella, M.; Bressan, R.; Pliego, F.; Hasegawa, P. Cambios metabólicos y de expresión génica en plantas superiores en respuesta al estrés salino. AgriScientia 1992, 9, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, R.R.; Raya, P.J.C.; Iturriaga, G. La trehalosa: Un azúcar osmoprotector con capacidad de señalización. Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 2015, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Elbein, A.D.; Pan, Y.T.; Pastuszak, I.; Carroll, D. New insights on trehalose: A multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castillo-Texta, M.G.; Álvarez-Gómez, T.B.; Ramírez-Yáñez, M.; Ramírez-Trujillo, J.A.; Suárez-Rodríguez, R. Overexpression of the SlPti4 Transcription Factor in Transgenic Tobacco Plants Confers Tolerance to Saline, Osmotic, and Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010114

Castillo-Texta MG, Álvarez-Gómez TB, Ramírez-Yáñez M, Ramírez-Trujillo JA, Suárez-Rodríguez R. Overexpression of the SlPti4 Transcription Factor in Transgenic Tobacco Plants Confers Tolerance to Saline, Osmotic, and Drought Stress. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo-Texta, Maria Guadalupe, Tania Belén Álvarez-Gómez, Mario Ramírez-Yáñez, José Augusto Ramírez-Trujillo, and Ramón Suárez-Rodríguez. 2026. "Overexpression of the SlPti4 Transcription Factor in Transgenic Tobacco Plants Confers Tolerance to Saline, Osmotic, and Drought Stress" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010114

APA StyleCastillo-Texta, M. G., Álvarez-Gómez, T. B., Ramírez-Yáñez, M., Ramírez-Trujillo, J. A., & Suárez-Rodríguez, R. (2026). Overexpression of the SlPti4 Transcription Factor in Transgenic Tobacco Plants Confers Tolerance to Saline, Osmotic, and Drought Stress. Horticulturae, 12(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010114