Abstract

Veraison represents a pivotal transition point in grape berry ripening, driven by a cascade of temporally coordinated physiological and molecular events. Studies have shown that the onset of veraison is initially triggered by a decline in cell turgor, regulated by osmotic potential and water status, which subsequently leads to fruit softening. This softening process is accompanied by extensive cell wall remodeling, establishing a structural basis for enhanced sugar influx. A rapid accumulation of sugars follows, acting not only as metabolic substrates but also as signaling molecules that synergize with abscisic acid (ABA) to activate transcriptional programs, including the induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis that drives skin color change. ABA accumulates at the early stages of veraison and functions as a key hormonal regulator initiating the ripening process. In contrast, auxin (IAA) and gibberellin (GA) levels decline prior to veraison, thereby releasing their inhibitory effects on ripening. Environmental factors such as water availability, light, and temperature significantly influence the timing and intensity of veraison by modulating hormonal signaling pathways. The initiation of grape berry ripening exemplifies a multilayered regulatory network that progresses through turgor signaling, hormonal regulation, metabolic reprogramming, and transcriptional activation, thereby providing a mechanistic framework for understanding non-climacteric fruit ripening. offering a mechanistic framework for understanding non-climacteric fruit ripening. This review provides an integrated perspective on the initiation mechanism of veraison, offering theoretical insights and practical implications for improving grape quality and vineyard management.

1. Introduction

Grape (Vitis vinifera) is a typical non-climacteric fruit, whose ripening is independent of ethylene accumulation and is primarily regulated by abscisic acid (ABA). The onset of ripening in grape berries coincides with a sharp increase in ABA levels, whereas ethylene shows only a slight and transient increase and does not drive the ripening process as it does in climacteric fruits; its precise signaling role in veraison initiation remains an open question [1,2]. The development of grape berries follows a characteristic double sigmoid growth curve, comprising two rapid growth phases (Stage I and Stage III) separated by a lag phase (Stage II) [3,4]. During Stage I, the berries undergo active cell division and expansion, while accumulating organic acids such as malic and tartaric acids, as well as phenolic precursors, maintaining a firm and green appearance [5]. Seed number, plant growth regulators, source-sink relationships, and environmental conditions largely determine the developmental dynamics during this stage. Water uptake is predominantly via the xylem, whereas the primary carbon resources required for metabolism are delivered through the phloem [1,6,7].

In most grape cultivars, the first rapid growth phase is followed by a lag phase (Stage II), during which berry enlargement slows, seed maturation progresses, and the berry undergoes metabolic preparations for the impending sugar accumulation, including a shift to phloem-dependent solute import and the activation of sugar transport mechanisms [8], and the duration of this phase varies among cultivars [1]. The onset of the second growth phase is marked by the occurrence of veraison, a critical transition point signifying the shift from berry development to ripening. The term “veraison” originates from the French word véraison, meaning “the beginning of ripening.” Hallmark features of this stage include a change in skin coloration (characterized by anthocyanin accumulation and a shift from green to red or purple in pigmented cultivars, and from green to translucent or golden-yellow in white cultivars), a rapid increase in sugar content, a decline in acidity, and major cell wall modifications. These include enhanced cell wall metabolism, elevated activity of key cell wall-modifying enzymes such as polygalacturonase (PG), pectin methylesterase (PME), expansins, and xyloglucan endotransglycosylases (XTHs), leading to reduced firmness and berry softening [9,10,11,12]. Moreover, the sugar-to-acid ratio, anthocyanin accumulation, and the formation of aroma precursors during veraison play a decisive role in determining the quality of both grapes and wine [13,14]. Given its decisive impact on final fruit and wine quality, understanding the mechanisms initiating veraison has become a major focus of current research.

Considerable progress has been made in recent years in comprehending the mechanics behind grape berry veraison. At the physiological level, the roles of turgor decline, changes in the activity of cell wall-modifying enzymes, and hormonal signaling, particularly abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene, have been extensively elucidated in the regulation of veraison-related events [2,15,16]. Berry softening, which is primarily caused by a substantial decrease in cell turgor, is the first physiological event that signals the start of veraison. This alteration occurs before skin coloring, volume growth, and sugar buildup. The initiation of softening relies on the early accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA) in both skin and flesh cells. Notably, this increase in ABA is not primarily attributed to the activation of biosynthetic genes such as VviNCED1/2, but rather to a marked reduction in ABA catabolites, including dihydrophaseic acid (DPA), suggesting that ABA accumulation may result from downregulated catabolism or enhanced import via the phloem. The rise in ABA levels promotes the expression of ABA-responsive factors (e.g., Grip55) and veraison-specific regulatory factors (e.g., Grip4), which further induce the coordinated upregulation of cell wall remodeling genes, including VviExp1, VviPME, VviPG, and VviXET. Additionally, ABA plays a central role in activating the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, as detailed in recent reviews that integrate hormonal control with metabolic profiling.

This results in decreased tissue elasticity, a loosening of the cell wall architecture, and eventually softening of the fruit. ABA also controls apoplastic water potential and aquaporin activity, which improves water outflow and lowers turgor pressure. Additionally, the early phase of veraison is characterized by a rapid downregulation of the auxin (IAA) signaling pathway, marking a hormonal shift from auxin to ABA dominance and redirecting the developmental program of the fruit. Together, these findings suggest that the initiation of veraison is orchestrated by ABA-mediated metabolic and signaling events, coupled with turgor loss and cell wall remodeling. This process serves as a physiological “switch” that establishes the foundation for subsequent sugar accumulation and anthocyanin biosynthesis [15,17,18]. While considerable progress has been made, key controversies remain regarding the hierarchical ordering of veraison-initiating signals. This review synthesizes recent research to systematically examine the initiation mechanisms of grape berry veraison, addressing current knowledge gaps and providing a theoretical framework for understanding non-climacteric fruit ripening.

2. Turgor Decline and Fruit Softening Initiate Veraison in Grapes

Grape berry development follows a well-characterized double sigmoid growth pattern, and the physiological shifts occurring at veraison have been extensively documented [19]. Historically, softening has only been considered a contemporaneous phenotypic change, with the commencement of grape berry veraison being ascribed to sugar accumulation and anthocyanin biosynthesis. However, Thomas et al. were the first to demonstrate that fruit softening and the decline in cell turgor pressure (P) occur prior to sugar accumulation and pigment synthesis, suggesting that softening may not be a consequence but rather a prerequisite indicator of ripening initiation [20]. Subsequently, Wada et al. and Matthews et al. further confirmed that softening is one of the earliest measurable physiological events during veraison by assessing fruit elastic modulus (E) and cell turgor pressure [21,22]. This series of studies was subsequently systematically validated by Castellarin et al., who formally proposed the hypothesis that fruit softening and turgor decline may constitute the initiating triggers of grape berry veraison. This study quantitatively measured the elastic modulus (E) and turgor pressure (P) of individual grape berries and employed a “boxing” treatment (a physical constraint to restrict berry expansion) to restrict berry expansion. The outcomes revealed that approximately 80% of fruit softening had occurred prior to the onset of sugar accumulation and anthocyanin synthesis, accompanied by significant declines in both E and P. Importantly, the transcriptional levels of several genes involved in cell wall modifications, including VviPME (encodes a pectin methylesterase), VviPG (encodes a polygalacturonase), and VviExp1 (encodes an expansin), were significantly upregulated following the drop in E below approximately 2 MPa in this system. This temporal correlation suggests that initial softening may result from passive cell wall loosening due to turgor loss, preceding active cell wall remodeling, though this interpretation requires validation across diverse cultivars and growing conditions [15].

Additionally, ABA concentrations rise in tandem with the early phases of softening, although the expression of the enzymes VviNCEDs that restrict the rate of ABA production is not increased. Instead, the rise in ABA levels is primarily accompanied by a reduction in its catabolite dihydrophaseic acid (DPA), suggesting that ABA accumulation may result from mechanisms such as decreased catabolism or enhanced import via the phloem or exogenous import. This result suggests that after turgor pressure and cellular tension decrease, ABA, a crucial ripening signal, is either released or carried into the berry. In turn, accumulated ABA induces the expression of multiple softening-related genes, such as VviExp1, VviPG, VviPME, and VviXET, which further promote cell wall loosening, suggesting a potential reinforcing feedback mechanism between ABA signaling and the softening process. This intimate interaction demonstrates how important ABA is for regulating berry softening and the subsequent ripening processes [15].

In conclusion, this hypothesis and its supporting experimental evidence overturn the traditional concept of “sugar-first, softening-later,” highlighting that changes in cellular hydraulic structure serve as a key signal initiating the fruit ripening program. Softening is not merely a physical phenomenon but functions as a “master switch” in the pre-veraison sequence, providing the necessary physiological conditions and temporal window for subsequent activation of sugar transport pathways, integration of pigment biosynthesis signals, and cellular metabolic remodeling. This new understanding offers a novel perspective for elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of grape berry ripening and lays a theoretical foundation for the study of ripening processes in non-climacteric fruits.

3. Sugar-Induced Initiation of Veraison in Grapes

During the initiation of grape berry veraison, as the fruit tissue softens and intercellular spaces expand, sugars transported via the phloem begin to accumulate substantially within the berries, primarily as glucose and fructose. Sugar accumulation coincides with fruit tissue softening, and while traditionally regarded as a ripening consequence, accumulating evidence suggests that reaching threshold levels may serve as a critical permissive signal for veraison activation. Pirie and Mullins were among the first to propose the role of sugar in promoting anthocyanin biosynthesis [23]. Subsequently, Hrazdina et al. and Keller et al. observed that in multiple grape cultivars, anthocyanin biosynthesis initiates once the fruit’s total soluble solids (TSS) reach approximately 9–10° Brix, independent of light exposure, nutrient status, or water availability. This finding suggests that sugar accumulation may serve as an intrinsic developmental timer in many cultivars, though the precise threshold exhibits genotypic variation influenced by environmental factors [24,25]. Recent studies have revealed that fruit softening occurs when total soluble solids (TSS) reach approximately 5° Brix; however, the expression of key anthocyanin biosynthetic genes such as VviUFGT and VviDFR, as well as pigment accumulation in the skin cells, only commences once sugar levels reach around 10° Brix. This 10° Brix sugar threshold is highly consistent with previous reports, suggesting that the anthocyanin biosynthesis program has a “sugar-dependent activation threshold.” [18]. Notably, interventions that impede sugar import into the fruit, such as phloem transport blockage, significantly suppress anthocyanin accumulation and veraison onset, even when fruit softening has occurred or ABA levels have increased. This further supports that sugar accumulation is a necessary prerequisite for triggering pigment biosynthesis, rather than merely providing energy and substrates for downstream processes [15]. Conversely, sugar accumulation requires ABA-mediated regulation of transcription factors to fully activate the ripening transcriptional program. ABA plays a crucial role in the activation of sugar import and transport systems; following softening, the phloem becomes the primary pathway for sugar influx into the berry. ABA signaling is associated with the induction of sucrose and hexose transporters, including VvSUC11/12 and VvHT2, potentially mediated through ABA-responsive elements in their promoters, thereby enhancing cellular capacity for sugar uptake and accumulation. This process not only provides energy substrates but also establishes a high-sugar signaling environment that, in synergy with ABA, upregulates the expression of key transcription factors, including VviMYBA1 and VviMYBA2, thereby initiating the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway [26,27].

Beyond transcriptional activation by hormones, the post-transcriptional regulation of key transcription factors also plays a critical role in fine-tuning anthocyanin biosynthesis. A recent study by Gao et al. identified a naturally occurring alternative splicing variant of VvMYBA1, designated VvMYBA1-L, in grape berries. This variant encodes a truncated protein that interacts with the full-length VvMYBA1. Instead of activating transcription, the VvMYBA1-L/VvMYBA1 heterodimer functions as a dominant-negative regulator, significantly suppressing the transactivation activity of VvMYBA1 on the promoters of key anthocyanin pathway genes, such as VvUFGT and VvDFR. This mechanism provides a novel molecular explanation for the lack of anthocyanin accumulation in the flesh of certain grape cultivars and highlights the intricate multi-level regulation of the veraison-associated coloration program [28].

At the molecular level, sugars function not only as metabolic substrates but also as signaling molecules that activate the transcription of ripening-related genes by regulating the expression and activity of multiple transcription factors. For example, exogenous application of glucose, sucrose, or fructose can induce the expression of key transcription factors such as VviMYBA1 and VviMYBA2 in detached grape berries, thereby promoting the transcriptional activation of structural genes like UFGT and initiating the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway [18]. Studies utilizing an established in vitro cultured berry system have demonstrated that high sugar concentrations can increase anthocyanin content and advance its biosynthesis, while the level of its precursor, phenylalanine, decreases under high sugar supply [29]. Furthermore, hexokinase (HXK) activity and calmodulin-dependent kinases may drive sugar-induced anthocyanin production [30]. Subsequent studies further demonstrated that in grape berry discs, sugar-induced anthocyanin accumulation depends on the phosphorylation activity of HXK [31]. Moreover, mannose—a poor metabolic substrate that is nevertheless efficiently phosphorylated by hexokinase (HXK)—can induce anthocyanin accumulation and F3H expression in grapes. In contrast, sugar analogs that are not substrates of HXK, such as 3-O-methylglucose and 6-deoxyglucose, fail to trigger anthocyanin accumulation, indicating that HXK-mediated sugar phosphorylation is essential for sugar-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis. Additionally, it has been demonstrated in apple that the glucose sensor HXK1 promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis by phosphorylating and stabilizing the transcription factor MdbHLH3. Under low-temperature conditions, MdbHLH3 binds to the promoters of DFR, UFGT, and Myb1, thereby enhancing anthocyanin accumulation [32,33]. In addition, sugars have been reported to regulate the expression levels of both structural genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis—including CHS, DFR, LDOX, and UFGT- as well as regulatory genes such as MYB [33,34,35]. In peach, transcriptomic and metabolomics analyses were performed on fruit flesh treated in vitro with glucose, sucrose, sorbitol, and fructose for 12 and 24 h. The results showed that sugar treatments significantly promoted the accumulation of cyanidin-3-O-(6-O-p-coumaroyl) glucosides and upregulated the expression of key genes in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, including PpDFR and PpUFGT. However, PpMYB10.1 and PpBL, the two major transcription factors previously associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis in peach, were not simultaneously upregulated. Instead, two MYB transcription factors (PpMYB6 and PpMYB44-like) and three bHLH transcription factors (PpbHLH35, PpbHLH51, and PpbHLH36-like) were significantly induced by sugar treatment. Subsequent dual-luciferase reporter assays demonstrated that these MYB transcription factors cooperatively interact with the bHLH proteins to activate the PpUFGT promoter [36]. These findings suggest that sugar signaling may promote anthocyanin biosynthesis and accumulation by activating specific transcription factors. Similarly, exogenous sucrose treatment in pear was found to significantly enhance anthocyanin accumulation in the fruit peel. This treatment also markedly induced the expression of genes related to anthocyanin biosynthesis and sugar transporter genes, indicating that sucrose may promote fruit coloration in pear by modulating both sugar metabolism and the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway [37]. Therefore, sugars may act as signaling molecules to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis, and this signaling function is closely associated with the phosphorylation activity of hexokinase (HXK).

In summary, the “threshold sensing” role of sugar accumulation extends beyond merely compensating for metabolic demands; it actively participates in orchestrating transcriptional activation and initiating pigment biosynthesis, thereby serving as a developmental “biological clock” that marks the transition of grape berries from the growth phase to the ripening phase. This highlights the central role of sugars as signaling molecules, elevating them from traditional “markers of ripening” to key “ripening inducers,” and offering a new perspective for understanding the maturation mechanisms of grapes and other non-climacteric fruits.

4. Hormonal Regulation Initiates Grape Veraison

Grape, as a typical non-climacteric fruit, undergoes veraison and maturation processes that do not rely on an ethylene burst but are instead governed by the synergistic and antagonistic interactions among multiple plant hormones. It is important to note that the precise timing of this ABA surge can vary considerably and is modulated by environmental factors and growing conditions. During the initiation of veraison, dynamic changes in hormone signaling not only act as developmental “triggers” but also precisely coordinate a series of key ripening events, including cell softening, sugar accumulation, and gene expression reprogramming. Coombe was the first to propose that the onset of grape fruit ripening, particularly veraison, is regulated by plant hormones, especially the accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA). He emphasized that, unlike climacteric fruits such as tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), where ethylene predominantly drives ripening initiation, grape ripening may be primarily controlled by non-ethylene hormones such as ABA [38]. Subsequently, Robinson and Davies systematically measured the levels of multiple hormones (ABA, IAA, GA, and ethylene) and the expression of hormone-related genes at different developmental stages of grape berries. They were the first to clearly propose and validate that a hormone signaling network dominated by abscisic acid (ABA), with auxin (IAA) and gibberellins (GA) acting as antagonistic factors, plays a central regulatory role in the initiation of grape veraison [39]. Their study laid the foundation for the hormonal regulation theory of grape ripening and provided theoretical support for subsequent investigations into the integration mechanisms between hormones and other signals, such as sugars and turgor pressure. Besides ABA, auxin (IAA), gibberellins (GA), ethylene, Jasmonic acid, brassinosteroids, and polyamines also participate in this complex regulatory network in a spatial-temporal manner, collectively determining the timing and progression of grape veraison initiation [40,41].

In the study by Robinson and Davies, abscisic acid (ABA) content in grape berries increased significantly 1–2 weeks prior to veraison, occurring simultaneously in both the skin and pulp. This rise in ABA preceded sugar accumulation and anthocyanin biosynthesis, and was synchronous with the fruit softening process, indicating a temporal advantage of ABA as the initiating signal. Furthermore, the expression of the ABA biosynthesis rate-limiting enzyme genes VviNCED1 and VviNCED2 also began to increase during the early stages of veraison. These findings reinforce the central role of ABA as the key signal triggering the onset of the veraison program [39]. Recent studies suggest that early ABA accumulation may involve multiple mechanisms, including potential hydrolysis of abscisic acid-glucose ester (ABA-GE) by β-glucosidases and suppression of catabolic flux, though the specific enzymatic players require further characterization, as indicated by the decline of its catabolite dihydrophaseic acid (DPA). These changes occur synchronously with the decrease in cell turgor pressure and fruit softening, suggesting a reciprocal causal relationship between ABA accumulation and softening processes that jointly initiate the maturation signaling cascade [15]. Additionally, exogenous ABA treatment has been shown to significantly accelerate the onset of grape veraison, increase anthocyanin content in the grape skin, and upregulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes such as CHS, UFGT, and MybA1 [42,43,44]. However, the effectiveness of exogenous ABA treatment in promoting grape berry veraison depends on the timing and concentration of application [45]. Early treatment or low concentrations fail to effectively induce fruit coloration. For instance, application of 400 mg/L ABA three weeks prior to veraison does not effectively initiate coloration, whereas treatment closer to veraison enhances sugar accumulation and color development. Additionally, low-concentration ABA treatments (5 mg/L) applied near veraison also fail to effectively trigger or promote the onset of veraison [46]. Similarly, a study on ‘Flame Seedless’ grapes demonstrated that ABA treatments at 75 mg/L and 150 mg/L had no significant effect on the initiation of fruit veraison or anthocyanin accumulation, whereas treatment with 300 mg/L ABA significantly accelerated veraison and enhanced anthocyanin accumulation [47]. Furthermore, studies have shown that two applications of 400 mg/L ABA after veraison can double anthocyanin content, whereas a single application has a weaker effect, indicating that both concentration and frequency of application jointly determine the treatment efficacy [45]. On the other hand, ABA can indirectly promote anthocyanin accumulation by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) [42]. The ABA receptor VlPYL1 is highly expressed in grape berry skin, and its overexpression significantly enhances ABA sensitivity, upregulating ABA signaling pathway genes and flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes, thereby promoting anthocyanin accumulation [48].

Auxin and ABA play antagonistic roles during grape berry maturation [49], indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) concentrations are high in flowers and young fruits but decline rapidly prior to veraison [49]; Auxin delays increases in fruit size, sugar accumulation, and anthocyanin content [50,51,52]. Application of naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) prior to veraison inhibits anthocyanin accumulation, and treatment with the auxin analog BTOA prior to veraison also delays ripening and alters gene expression [50,52]. Moreover, NAA application affects the natural decline of IAA in ripening berries, thereby delaying maturation and reducing the heterogeneity between immature and mature berries within the same cluster [53]. Exogenous auxin treatment applied before veraison significantly inhibits the onset of grape veraison, suppresses anthocyanin accumulation during veraison, and delays the ripening process [44]. Furthermore, studies have shown that exogenous auxin treatment delays grape berry veraison and ripening by modulating gene expression and altering cell wall metabolism [54]. Previous studies have shown that auxin (NAA) treatments applied closer to veraison are more effective at delaying the onset of veraison [55].

Gibberellin (GA) signaling also exhibits an inhibitory effect on grape veraison. Early application of GA in seedless grape berry development increases fruit size, thereby enhancing its economic value. In grapes, bioactive GA concentrations are relatively high during flowering and early fruit development but progressively decline throughout subsequent fruit maturation stages [56,57]. Pre-veraison application of gibberellin (GA) in grapevine was found to suppress fruit veraison and significantly reduce anthocyanin accumulation, indicating that GA treatment negatively regulates grape berry coloration and maturation [44]. Therefore, the decline in IAA and GA levels is thought to create a permissive ‘release window’ for ABA accumulation and signaling, creating a hormonal balance tipping point that switches the fruit from a repressive state to the maturation program, thereby driving the initiation of veraison in grape berries.

Meanwhile, grape veraison is negatively regulated by cytokinins. Fruit set and growth are influenced by cytokinins, which, like auxin, are abundant in the mesocarp of immature berries but quickly decrease before and around veraison, staying low until ripening and full maturation [57,58]. The dynamic changes in cytokinin levels correspond to their promotive role in early fruit cell division and inhibitory effect during fruit maturation. The Application of cytokinin analogs, such as forchlorfenuron (CPPU), in table grapes can optimize fruit size and increase yield; however, this treatment suppresses anthocyanin accumulation while promoting tannin content [59,60,61]. Exogenous application of the cytokinin forchlorfenuron (CPPU) to lychee fruit results in delayed coloration [62], suggesting that cytokinins may play an inhibitory role in the initiation of grape veraison.

Despite being a non-climacteric fruit, research has shown that a brief rise in endogenous ethylene may control fruit development and is linked to important ripening processes like the accumulation of anthocyanins, the generation of sugar, and the decrease in acidity [63,64]. Furthermore, exogenous ethylene treatment can enhance the expression of structural genes related to phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis, as well as their transcriptional regulators [65]. According to recent research, exogenous ethylene (ETH) accelerates the ripening process of grapes by causing their skin to turn from green to red and purplish-red [66]. Exogenous ethylene increases anthocyanin accumulation in grape berries by upregulating the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes [16,67]. Similar results have been reported in plums [68,69]and apples [70,71]. However, ethylene’s role in fruit ripening and coloration is complex and can have both positive and negative effects, depending on the species and regulatory context. For example, in tomato (S. lycopersicum) and red pear, ethylene inhibits anthocyanin accumulation, thereby hindering fruit coloration [72,73].

Jasmonates (JAs) are a class of lipid-derived plant hormones that can be metabolized into various derivatives, such as methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and jasmonoyl isoleucine (JA-Ile) [74]. Jasmonates play an important role in anthocyanin accumulation in plants [75]. Exogenous application of MeJA has been shown to induce anthocyanin accumulation in various fruits, including apple, grape, blueberry, and strawberry [76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. Pre-veraison spraying of MeJA in grapes promotes the initiation of fruit coloration [44]. In pear, postharvest MeJA treatment enhances UV-induced anthocyanin accumulation in the fruit [80]. Further studies indicate that JA-induced ubiquitination and degradation of JAZ proteins release the interaction between JAZ proteins and bHLH and MYB transcription factors, thereby freeing the transcriptional activity of the WD-repeat/bHLH/MYB complexes. These complexes subsequently activate their respective downstream signaling cascades to regulate anthocyanin accumulation [81,82].

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are polyhydroxylated steroid plant hormones that play key roles in cell division and elongation, vascular differentiation, flowering, pollen development, and photomorphogenesis. Brassinolide (BR) promotes grape berry ripening regulation; application of brassinolide enhances berry coloration and accelerates ripening, whereas treatment with brassinazole (BR biosynthesis inhibitor) delays berry maturation [57]. Additionally, it has been suggested that brassinolide may serve as the initial signal for grape berry ripening, possibly through the regulation of ethylene levels [53]. Pre-veraison treatment of wine grape berries with brassinosteroids (BR) significantly increased the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes such as CHS, ANS, UFGT, and MYBA1, and promoted skin color development [83]. Similarly, exogenous treatment with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) promoted fruit coloration in Vitis vinifera and increased the activity of the UFGT enzyme. EBR treatment also elevated the flavonoid and anthocyanin content in the pulp of ‘Yan73’ grapes [84]. Furthermore, studies have shown that exogenous 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) and light synergistically promote grape fruit coloration [85].

Furthermore, polyamines produced during malolactic fermentation primarily putrescine, histamine, and tyramine, also have a role in controlling the accumulation of anthocyanin. In grapevines, foliar administration of polyamine biosynthesis inhibitors decreased the amount of free polyamines while also preventing the buildup of anthocyanins and polyphenols [86]. Conversely, exogenous treatment of grapes with putrescine significantly increased anthocyanin content [87], indicating that polyamines may positively regulate grape fruit coloration.

It is interesting to note that sugars also work in concert with ethylene, cytokinins, and jasmonates (JA) to control the accumulation of anthocyanins. By upregulating biosynthetic genes, JA encourages the buildup of anthocyanins and collaborates with sucrose to facilitate this process [88,89]. In Eucalyptus and other perennial woody plants, cytokinins (CK) efficiently stimulate anthocyanin formation. CK controls this process in Eucalyptus by means of sugar signaling. When sugar famine is brought on by defoliation or shade, the CK-induced rise in leaf sugar content is dramatically inhibited, which prevents CK-induced anthocyanin synthesis. However, CK treatment greatly encourages sucrose accumulation in leaves. In vitro experiments further demonstrated that CK-induced anthocyanin synthesis in Eucalyptus depends on the presence of sugar [90]. In Arabidopsis, cytokinins enhance sugar-induced anthocyanin accumulation through a two-component signaling cascade involving type-B response regulators (ARR1, ARR10, and ARR12) [91]. And ethylene negatively regulates sugar-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Ethylene suppresses the expression of transcription factors that promote anthocyanin biosynthesis, such as GLABRA3, TRANSPARENT TESTA8, and PRODUCTION OF ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT1, while simultaneously promoting the expression of the negative R3-MYB regulator MYBL2. This leads to inhibition of sucrose- and light-induced anthocyanin accumulation. Additionally, the sugar transporter gene SUC1 acts as an integrator of sugar, light, and ethylene signals; ethylene inhibits sucrose-induced anthocyanin accumulation by repressing SUC1 expression [92,93].

5. Environmental Effects on the Initiation of Grape Veraison

5.1. Effects of Light on the Initiation of Grape Veraison

Light is one of the primary environmental elements that affects when grape color changes. Light conditions affect the production and build-up of anthocyanins. Specific light wavelengths activate different photoreceptors: red light is perceived by phytochromes and blue light by cryptochromes. Once activated, these photoreceptors regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis through phytochrome-interacting factors and other related transcription factors. In many cultivars, the combination of red and blue light has a synergistic effect [94,95]. Furthermore, the accumulation of glucose and anthocyanins is affected differently by different light wavelengths; red and blue light are thought to work best together to promote the accumulation of both substances [96]. Strong light promotes photosynthesis, increasing sugar accumulation and providing precursor substances for anthocyanin synthesis, while shading treatment significantly delays color change and reduces anthocyanin content [97]. Light not only directly affects the accumulation of sugars and anthocyanins but also indirectly influences grape quality by affecting fruit respiration and metabolic pathways. Insufficient light may lead to impaired sugar accumulation, thereby affecting the flavor and coloration of grapes [98]. At the same time, variations in light intensity can also affect the balance of organic acids and other metabolites in grape berries, thereby further influencing wine quality [99]. UV-B radiation promotes the buildup of anthocyanins and other phenolic compounds in the skin, accelerating coloration and contributing to berry ripening [100,101]. Therefore, under facility cultivation conditions, rational regulation of light intensity and wavelength is an important approach to improving grape quality.

5.2. The Influence of Temperature on the Initiation of Veraison

Temperature, as a vital environmental factor, greatly influences the start of veraison and fruit quality development by regulating physiological processes and molecular signaling networks. High-temperature conditions reduce the accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA), which leads to decreased expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes such as CHS, DFR, and ANS, as well as the key transcription factor MYBA1. Additionally, the activity of UFGT, an essential enzyme responsible for glycosylating anthocyanidins, is inhibited under heat stress, resulting in lower glycosylation efficiency. Furthermore, high temperature directly accelerates anthocyanin degradation through oxidative reactions that damage the anthocyanin structure [102,103,104,105,106]. Conversely, low temperatures significantly boost anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berries. Multiple studies have shown that cold conditions enhance anthocyanin production by increasing ABA levels and activating related genes [107]. For instance, in apples, low-temperature treatment markedly increased the expression of anthocyanin-related genes such as MdCHS and MdCHI and promoted anthocyanin accumulation [108]. Similarly, in red-skinned grapes, lower temperatures also stimulated the expression of key genes involved in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway [109,110].

5.3. Role of Water in Triggering Veraison

Water availability critically influences the onset of veraison by modulating physiological and molecular pathways. Mild to moderate water deficit (e.g., 50–70% of field capacity) can enhance grape coloration and quality [111]. This improvement is associated with a preferential allocation of photoassimilates to berries, potentially through the upregulation of sucrose transporter genes (e.g., SUC27), leading to accelerated sugar accumulation and providing substrate for anthocyanin synthesis. This process is often mediated by drought-induced accumulation of endogenous abscisic acid (ABA), which directly upregulates key anthocyanin biosynthetic genes such as UFGT, CHS, and F3H. Studies have shown that under prolonged water deficit, anthocyanin content can increase significantly (e.g., by 37–57% in Merlot) [112,113]. However, severe drought stress (<50% field capacity) can restrict sugar accumulation and degrade fruit quality by excessively limiting photosynthesis and overall berry development. Therefore, precision irrigation strategies, such as regulated deficit irrigation applied before veraison, can be used to promote earlier veraison and improve fruit quality. Exogenous ABA application before veraison can similarly mimic drought signals to advance veraison timing.

5.4. Regulatory Effects of Soil Nutrients on the Initiation of Grape Veraison

Nitrogen and potassium in the soil are closely related to grape veraison. Nitrogen promotes photosynthesis, providing carbon skeletons and energy. However, excessive nitrogen leads to vigorous vegetative growth (such as lush shoots and leaves), which competes with the fruit for photosynthetic products, delaying ripening and inhibiting veraison. Studies have shown that under high nitrogen conditions, the total sugar content in grapes decreases, acidity decline is delayed, and anthocyanin accumulation is hindered [114,115,116]. Excessive nitrogen reduces the supply of anthocyanin precursors by inhibiting the activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) [116]. Potassium (K), as an essential macronutrient, has a complex influence on anthocyanin accumulation in plants. Foliar application of potassium fertilizer on Kyoho grape leaves may accelerate anthocyanin accumulation by altering the transcription levels of flavonoid biosynthesis genes such as PAL, CYP73A, 4CL, CHS, F3H, and UFGT [117]. Similarly, foliar potassium application has been shown to promote anthocyanin accumulation in grape berries [118].

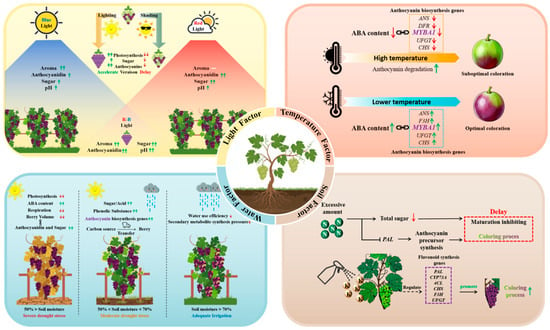

In summary, environmental factors modulate the onset of grape veraison through multiple interconnected pathways (Figure 1). Strategic management of these factors can help optimize berry ripening and final fruit quality.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic Diagram of Environmental Factors Affecting the Initiation of Grape Veraison.

6. The Epigenetic Perspective on Grape Veraison

In recent years, the role of epigenetic regulation in fruit ripening has attracted widespread attention [119]. Taking tomato as an example, its ripening process is accompanied by large-scale DNA demethylation across the genome. Studies have found that the DNA demethylase SlDML2 is essential for initiating the ripening program by mediating genome-wide demethylation. Specifically, SlHMGA3 promotes the transcription of SlDML2 by binding to the AT-rich region in its promoter. Subsequently, SlDML2 facilitates the demethylation of ripening-related transcription factor genes, ultimately activating the ethylene synthesis signaling pathway and thereby driving tomato fruit ripening [120,121].

This phenomenon of ripening-associated DNA demethylation is not an isolated case. A similar decrease in genomic methylation levels has also been observed during strawberry ripening. However, unlike in tomato, where it is driven by the upregulation of demethylase expression, the methylation changes in strawberry are primarily caused by a reduction in the activity of the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway [122]. This conclusion was validated by the finding that silencing FvAGO4, a key component of the RdDM pathway, led to early reddening and a precocious ripening phenotype in the fruit. Furthermore, application of the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine could induce premature ripening in strawberry, indicating that DNA methylation is a key regulatory factor in strawberry maturation [122].Although the underlying causes for the changes in methylation levels differ between these two typical model fruits, the related studies support the notion that genomic DNA hypomethylation is a crucial epigenetic event for initiating the fruit ripening process.

6.1. The Impact of DNA Methylation on Grape Veraison

In different plant species, diverse epigenetic regulatory mechanisms can mediate similar physiological functions. Xie et al. recently found that treating ‘Merlot’ grapes with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) reduced the CpG methylation level of genomic DNA, thereby regulating the expression of key ripening genes and ultimately accelerating the veraison process [123]. This finding was further confirmed by Guo et al. in ‘Kyoho’ grapes [124]. Additionally, Kong et al. revealed that another inhibitor, Zebularine, could promote anthocyanin accumulation by inducing localized demethylation at specific gene loci (such as the UFGT promoter) and integrating environmental signal responses [125].

Notably, Jia et al. reported contrasting results from 5-azaC treatment in ‘Kyoho’ grapes: the application significantly inhibited the veraison process and led to reduced levels of anthocyanin metabolites and downregulated expression of related genes [126]. This discrepancy could possibly be attributed to the dose-dependent effects of 5-azaC, which induce varying degrees of demethylation and consequently disrupt the balance between methylation and demethylation, or it be attributed to critical differences in experimental conditions, such as the timing of 5-azaC application, or the distinct genetic backgrounds of the plant materials used.

In a recent study, Kong et al. revealed that epiallelic variation in the promoter region of the grape MYBA1 transcription factor serves as a key mechanism underlying flesh color differences, whereby hypermethylation at this locus is stably inherited and suppresses anthocyanin synthesis. This finding elucidates the potential regulatory role of stable epigenetic marks in determining grape berry color [127].

As previously discussed, the central role of ABA in non-climacteric fruit ripening has been well-established. A recent study revealed that ABA can influence grape berry ripening and stress responses by modulating DNA methylation. Through whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis following exogenous ABA treatment in ‘Summer Black’ grape, Li et al. demonstrated that the expression of certain negative regulators of ABA signaling (e.g., D27-like and CARS) was downregulated due to hypermethylation of their promoters. Concurrently, the expression of several ripening-related genes (e.g., F3H and PGIPL1) was upregulated in association with promoter hypomethylation. Therefore, these findings suggest that ABA may induce grape fruit ripening by mediating methylation of fruit ripening-related genes [128].

6.2. Histone Modifications During Grape Veraison

Histone modifications represent a crucial category of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms during fruit ripening. These dynamic and reversible chemical modifications (e.g., acetylation, methylation) alter chromatin conformation, thereby precisely modulating the transcriptional activity of ripening-related genes [129]. However, compared to DNA methylation, histone modifications remain less explored in grape berries.

Recently, Jia et al. discovered that treatment of ‘Kyoho’ grapes and white strawberry fruits with the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA significantly promoted anthocyanin biosynthesis and upregulated the expression of related genes, including PAL, CHS, F3H, and MYBA1 [130]. Based on these findings, the researchers identified a key transcriptional repressor complex, VvHDAC19–VvERF4. Mechanistically, this complex suppresses transcription by reducing histone H3/H4 acetylation levels at the promoters of key anthocyanin biosynthesis genes (e.g., VvMYB5a), thereby inhibiting anthocyanin accumulation [130]. This study reveals that high levels of histone acetylation serve as a critical epigenetic factor promoting fruit coloration and ripening.

Beyond acetylation, histone methylation also plays a significant role in grape berry ripening. Cheng et al. found that treatment of ‘Kyoho’ grapes with the histone methyltransferase inhibitor MTA significantly induced the expression of VviJMJ21, a gene encoding a JmjC-family demethylase, and promoted early fruit ripening. Further mechanistic investigation demonstrated that the MADS-box transcription factor VviAGL6a directly binds to and activates the VviJMJ21 promoter, thereby orchestrating the early ripening process in grape berries [131].

Shang et al. systematically identified the H3K4 histone methyltransferase gene family in grapevine and characterized its expression patterns during fruit ripening and in response to postharvest reactive oxygen species (ROS) treatment. Their study revealed that VvH3K4-5 was significantly upregulated during berry ripening, with particularly pronounced expression differences in early-ripening cultivars, suggesting its role as a key candidate gene regulating grape berry maturation,. Further promoter activity analysis demonstrated that the promoter activity of VvH3K4-5 was markedly suppressed by H2O2, indicating that this gene may function as a target of ROS signaling and participate in fruit ripening regulation by modulating histone methylation states [132].

These findings collectively suggest that elevated levels of histone acetylation may cooperatively promote the fruit ripening process. Notably, previous studies on lysine methylation have predominantly focused on histones, while the functions of non-histone lysine methylation in plants remain poorly understood. Employing 4D label-free quantitative proteomics coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS), Pei et al. achieved the first systematic identification of non-histone lysine methylation in grapevine. Their research found that during grape berry ripening, the majority of genes encoding methylated proteins were significantly upregulated in at least one developmental stage, implying a potential regulatory role for this modification in the fruit maturation process [133].

Plant ASR (Abscisic acid, Stress, Ripening-induced) proteins were initially identified in tomato, where their expression is induced by fruit ripening and drought stress [119]. Further investigation by Atanassov et al. revealed that the grape ASR protein contributes to the maintenance of histone modifications and chromatin states. In VvMSA-silenced grape embryogenic cells, levels of H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 decreased, H3K9me2 increased, and H4K16ac was significantly reduced [134]. It should be noted, however, that this study did not directly validate the function of VvMSA in a fruit ripening model, and its specific regulatory mechanisms require further exploration [134].

7. Summary and Future Perspectives

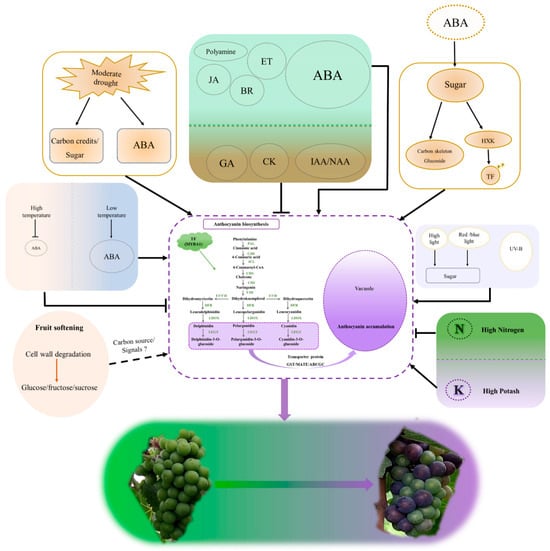

This review synthesizes current knowledge to propose an integrated model for veraison initiation, outlining a cascade of events: “turgor loss → hormonal shift (ABA dominance) → metabolic reprogramming → transcriptional activation.” This framework challenges the traditional “sugar-first” view by establishing berry softening as the initial trigger, which creates a permissive environment for subsequent ripening. We emphasize the central signaling roles of abscisic acid (ABA) and sugars while incorporating epigenetic regulation—specifically DNA methylation and histone modifications—as a crucial, emerging layer of control. This offers a more holistic understanding than previous reports. These insights provide direct practical value.

Based on the evidence discussed, we synthesize and present an integrated model of veraison initiation (Figure 2), which outlines a sequential cascade from turgor decline to transcriptional activation, offering a holistic framework for understanding ripening in non-climacteric fruits. The elucidated mechanisms support precision viticulture strategies, such as controlled irrigation and targeted hormone application, to manage veraison timing and improve fruit quality. Looking forward, this integrated perspective opens new research avenues. Deciphering the crosstalk between environmental signals, epigenetic modifications, and hormonal pathways will be key. Ultimately, this knowledge empowers the genetic improvement of grape varieties, enabling the development of cultivars with optimized ripening characteristics suitable for a changing climate.

Figure 2.

Model of the Triggering Mechanism for Grape Veraison.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-A.C., C.H. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-A.C. and C.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.-A.C., C.H., S.C., Z.L., G.L., F.X. and L.W.; supervision, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China, grant number 32202422 and Yunnan Provincial Key Research and Development Program, grant number 202403AP140029.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zenoni, S.; Savoi, S.; Busatto, N.; Tornielli, G.B.; Costa, F. Molecular regulation of apple and grape ripening: Exploring common and distinct transcriptional aspects of representative climacteric and non-climacteric fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 6207–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.; Almeida-Trapp, M.; Pimentel, D.; Soares, F.; Reis, P.; Rego, C.; Mithofer, A.; Fortes, A.M. The study of hormonal metabolism of Trincadeira and Syrah cultivars indicates new roles of salicylic acid, jasmonates, ABA and IAA during grape ripening and upon infection with Botrytis cinerea. Plant Sci. 2019, 283, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.L.; Xi, F.F.; Yu, Y.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, G.H.; Zhong, G.Y. Comparative RNA-Seq profiling of berry development between table grape ‘Kyoho’ and its early-ripening mutant ‘Fengzao’. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombe, B.G. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollat, N.; Carde, J.P.; Gaudillère, J.P.; Barrieu, F.; Diakou-Verdin, P.; Moing, A. Grape berry development: A review. Œno One 2002, 36, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, E.; Petrella, F.; Giovannozzi, M.; Piazzi, M.; Wilson, A.; Guidoni, S. Managing Vineyard Topography and Seasonal Variability to Improve Grape Quality and Vineyard Sustainability. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Eiras-Dias, J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Geros, H. Berry phenolics of grapevine under challenging environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18711–18739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Moltchanova, E.; Gerhard, D.; Trought, M.; Yang, L. Using Bayesian growth models to predict grape yield. OENO One 2020, 54, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anic, M.; Kontic, J.K.; Rendulic, N.; Carija, M.; Osrecak, M.; Karoglan, M.; Andabaka, Z. Evolution of Leaf Chlorophylls, Carotenoids and Phenolic Compounds during Vegetation of Some Croatian Indigenous Red and White Grape Cultivars. Plants 2024, 13, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, W.; Considine, J.A.; Considine, M.J. Influence of mixed and single infection of grapevine leafroll-associated viruses and viral load on berry quality. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balic, I.; Vizoso, P.; Nilo-Poyanco, R.; Sanhueza, D.; Olmedo, P.; Sepúlveda, P.; Arriagada, C.; Defilippi, B.G.; Meneses, C.; Campos-Vargas, R. Transcriptome analysis during ripening of table grape berry cv. Thompson Seedless. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, M.; Lacampagne, S.; Barsacq, A.; Gontier, E.; Petrel, M.; Mercier, L.; Courot, D.; Gény-Denis, L. Physical, Anatomical, and Biochemical Composition of Skins Cell Walls from Two Grapevine Cultivars (Vitis vinifera) of Champagne Region Related to Their Susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea during Ripening. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, A.; Uyak, C. Biochemical changes in some table grape cultivars throughout the ripening process. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2022, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.; Sarkhosh, A.; Habibi, F.; Gajjar, P.; Ismail, A.; Tsolova, V.; El-Sharkawy, I. Evaluation of Biochemical Juice Attributes and Color-Related Traits in Muscadine Grape Population. Foods 2021, 10, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Gambetta, G.A.; Wada, H.; Krasnow, M.N.; Cramer, G.R.; Peterlunger, E.; Shackel, K.A.; Matthews, M.A. Characterization of major ripening events during softening in grape: Turgor, sugar accumulation, abscisic acid metabolism, colour development, and their relationship with growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, M.; Rezk, A.; Obenland, D.; El-kereamy, A. Vineyard light manipulation and silicon enhance ethylene-induced anthocyanin accumulation in red table grapes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1060377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Davies, C. Molecular biology of grape berry ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2008, 6, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Montes, E.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, B.-M.; Shcherbatyuk, N.; Keller, M. Soft, Sweet, and Colorful: Stratified Sampling Reveals Sequence of Events at the Onset of Grape Ripening. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2020, 72, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, B.G.; McCarthy, M.G. Dynamics of grape berry growth and physiology of ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2000, 6, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.R.; Shackel, K.A.; Matthews, M.A. Mesocarp cell turgor in Vitis vinifera L. berries throughout development and its relation to firmness, growth, and the onset of ripening. Planta 2008, 228, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, H.; Shackel, K.A.; Matthews, M.A. Fruit ripening in Vitis vinifera: Apoplastic solute accumulation accounts for pre-veraison turgor loss in berries. Planta 2008, 227, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M.A.; Thomas, T.R.; Shackel, K.A. Fruit ripening inVitis viniferaL.: Possible relation of veraison to turgor and berry softening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2009, 15, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirie, A.; Mullins, M.G. Changes in Anthocyanin and Phenolics Content of Grapevine Leaf and Fruit Tissues Treated with Sucrose, Nitrate, and Abscisic Acid 1. Plant Physiol. 1976, 58, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrazdina, G.; Parsons, G.F.; Mattick, L.R. Physiological and Biochemical Events During Development and Maturation of Grape Berries. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1984, 35, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Hrazdina, G. Interaction of Nitrogen Availability During Bloom and Light Intensity During Veraison. II. Effects on Anthocyanin and Phenolic Development During Grape Ripening. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1998, 49, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Pfeiffer, A.; Sivilotti, P.; Degan, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Di Gaspero, G. Transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in ripening fruits of grapevine under seasonal water deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1381–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.T.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Esaka, M. Effects of plant hormones and shading on the accumulation of anthocyanins and the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in grape berry skins. Plant Sci. 2004, 167, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Tao, J. Anthocyanin accumulation in grape berry flesh is associated with an alternative splicing variant of VvMYBA1. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 195, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.W.; Meddar, M.; Renaud, C.; Merlin, I.; Hilbert, G.; Delrot, S.; Gomès, E. Long-term in vitro culture of grape berries and its application to assess the effects of sugar supply on anthocyanin accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4665–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitrac, X.; Larronde, F.; Krisa, S.; Decendit, A.; Deffieux, G.; Mérillon, J.M. Sugar sensing and Ca2+-calmodulin requirement in Vitis vinifera cells producing anthocyanins. Phytochemistry 2000, 53, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, H.; Pan, Q.; Zhan, J.; Huang, W. Sugars induce anthocyanin accumulation and flavanone 3-hydroxylase expression in grape berries. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 58, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.B.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhao, Q.; Yao, Y.X.; You, C.X.; Zhang, X.S.; Hao, Y.J. The bHLH transcription factor MdbHLH3 promotes anthocyanin accumulation and fruit colouration in response to low temperature in apples. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.G.; Sun, C.H.; Zhang, Q.Y.; An, J.P.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. Glucose Sensor MdHXK1 Phosphorylates and Stabilizes MdbHLH3 to Promote Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Apple. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollop, R.; Farhi, S.; Perl, A. Regulation of the leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase gene expression in Vitis vinifera. Plant Sci. 2001, 161, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payyavula, R.S.; Singh, R.K.; Navarre, D.A. Transcription factors, sucrose, and sucrose metabolic genes interact to regulate potato phenylpropanoid metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5115–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cao, K.; Wang, L.; Dong, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W. Two MYB and Three bHLH Family Genes Participate in Anthocyanin Accumulation in the Flesh of Peach Fruit Treated with Glucose, Sucrose, Sorbitol, and Fructose In Vitro. Plants 2022, 11, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Duan, R.; Han, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Xue, H. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Roles of Sucrose in Anthocyanin Accumulation in ‘Kuerle Xiangli’ (Pyrus sinkiangensis Yu). Genes 2022, 13, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, B.G. Research on development and ripening of the grape berry. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1992, 43, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Robinson, S.P. Differential screening indicates a dramatic change in mRNA profiles during grape berry ripening. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs encoding putative cell wall and stress response proteins. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, A.M.; Teixeira, R.T.; Agudelo-Romero, P. Complex Interplay of Hormonal Signals during Grape Berry Ripening. Molecules 2015, 20, 9326–9343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, C.; Davies, C. Hormonal control of grape berry development and ripening. Biochem. Grape Berry 2012, 1, 194–217. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Jiu, S.; et al. Exogenous Abscisic Acid Mediates Berry Quality Improvement by Altered Endogenous Plant Hormones Level in “Ruiduhongyu” Grapevine. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 739964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Edwards, E.J.; Duan, W.; Li, S.; Wang, L. The Synthesis and Accumulation of Resveratrol Are Associated with Veraison and Abscisic Acid Concentration in Beihong (Vitis vinifera × Vitis amurensis) Berry Skin. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wang, X.; Xuan, X.; Sheng, Z.; Jia, H.; Emal, N.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, C.; Fang, J. Characterization and Action Mechanism Analysis of VvmiR156b/c/d-VvSPL9 Module Responding to Multiple-Hormone Signals in the Modulation of Grape Berry Color Formation. Foods 2021, 10, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, R.; Roberto, S.R.; de Souza, R.T.; Borges, W.F.S.; Anderson, M.; Waterhouse, A.L.; Cantu, D.; Fidelibus, M.W.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Exogenous Abscisic Acid Promotes Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Increased Expression of Flavonoid Synthesis Genes in Vitis vinifera × Vitis labrusca Table Grapes in a Subtropical Region. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, S.; Loveys, B.; Ford, C.; Davies, C. The relationship between the expression of abscisic acid biosynthesis genes, accumulation of abscisic acid and the promotion ofVitis viniferaL. berry ripening by abscisic acid. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2009, 15, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppi, M.C.; Fidelibus, M.W.; Dokoozlian, N. Abscisic Acid Application Timing and Concentration Affect Firmness, Pigmentation, and Color of ‘Flame Seedless’ Grapes. HortScience 2006, 41, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, M.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Duan, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Characterization of the ABA Receptor VlPYL1 That Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation in Grape Berry Skin. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, C.; Keyzers, R.A.; Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. Sequestration of auxin by the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-1 in grape berry (Vitis vinifera L.) and the proposed role of auxin conjugation during ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3615–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, C.; Boss, P.K.; Robinson, S.P. Treatment of grape berries, a nonclimacteric fruit with a synthetic auxin, retards ripening and alters the expression of developmentally regulated genes. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, C.; Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. Acyl substrate preferences of an IAA-amido synthetase account for variations in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) berry ripening caused by different auxinic compounds indicating the importance of auxin conjugation in plant development. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4267–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliotto, F.; Corso, M.; Rizzini, F.M.; Rasori, A.; Botton, A.; Bonghi, C. Grape berry ripening delay induced by a pre-véraison NAA treatment is paralleled by a shift in the expression pattern of auxin-and ethylene-related genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthu, S.; O’Neil, S.T.; Di, Y.; Ansarolia, M.; Megraw, M.; Deluc, L.G. A comparative study of ripening among berries of the grape cluster reveals an altered transcriptional programme and enhanced ripening rate in delayed berries. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5889–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, S.; Tucker, M.R.; Tan, H.-T.; Burbidge, C.A.; Fasoli, M.; Böttcher, C.; Boss, P.K.; Pezzotti, M.; Davies, C. Auxin treatment of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) berries delays ripening onset by inhibiting cell expansion. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 103, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Böttcher, C.; Nicholson, E.L.; Burbidge, C.A.; Boss, P.K. Timing of auxin treatment affects grape berry growth, ripening timing and the synchronicity of sugar accumulation. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, G.M.; Davies, C.; Shavrukov, Y.; Dry, I.B.; Reid, J.B.; Thomas, M.R. Grapes on steroids. Brassinosteroids are involved in grape berry ripening. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, G.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Himelrick, D.G. Growth and developmental responses of seeded and seedless grape berries to shoot girdling. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2003, 128, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Böttcher, C. Other hormonal signals during ripening. In Fruit Ripening: Physiology, Signalling and Genomics; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Peppi, M.C.; Fidelibus, M.W. Effects of forchlorfenuron and abscisic acid on the quality of ‘Flame Seedless’ grapes. HortScience 2008, 43, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Mazzeo, A.; Netti, G.; Pacucci, C.; Matarrese, A.M.S.; Cafagna, I.; Mastrorilli, P.; Vezzoso, M.; Gallo, V. Girdling, Gibberellic Acid, and Forchlorfenuron: Effects on Yield, Quality, and Metabolic Profile of Table Grape cv. Italia. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 65, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, I.; Bahar, A.; Kaplunov, T.; Zutchi, Y.; Daus, A.; Lurie, S.; Lichter, A. Effect of the Cytokinin Forchlorfenuron on Tannin Content of Thompson Seedless Table Grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 65, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-S.; Luo, Y.-C.; Wang, S.-W.; Wang, H.-C.; Harpaz-Saad, S.; Huang, X.-M. Residue Analysis and the Effect of Preharvest Forchlorfenuron (CPPU) Application on On-Tree Quality Maintenance of Ripe Fruit in “Feizixiao” Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 829635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, C.; El-Kereamy, A.; Roustan, J.-P.; Latché, A.; Lamon, J.; Bouzayen, M. Ethylene seems required for the berry development and ripening in grape, a non-climacteric fruit. Plant Sci. 2004, 167, 1301–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tira-Umphon, A.; Roustan, J.-P.; Chervin, C. The stimulation by ethylene of the UDP glucose-flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) in grape tissues is independent from the MybA transcription factors. Vitis 2007, 4, 210–211. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.-Y.; Song, C.-Z.; Chi, M.; Wang, T.-M.; Zuo, L.-L.; Li, X.-L.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Xi, Z.-M. The effects of light and ethylene and their interaction on the regulation of proanthocyanidin and anthocyanin synthesis in the skins of Vitis vinifera berries. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 79, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Z. Light influences the effect of exogenous ethylene on the phenolic composition of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1356257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kereamy, A.; Chervin, C.; Roustan, J.-P.; Cheynier, V.; Souquet, J.-M.; Moutounet, M.; Raynal, J.; Ford, C.; Latché, A.; Pech, J.-C.; et al. Exogenous ethylene stimulates the long-term expression of genes related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berries. Physiol. Plant. 2003, 119, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganaris, G.A.; Vicente, A.R.; Crisosto, C.H.; Labavitch, J.M. Effect of delayed storage and continuous ethylene exposure on flesh reddening of ‘Royal Diamond’ plums. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 2180–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cui, X.; Niu, J.; Ma, F.; Li, P. Visible light regulates anthocyanin synthesis via malate dehydrogenases and the ethylene signaling pathway in plum (Prunus salicina L.). Physiol. Plant 2021, 172, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qiu, K.; Sun, W.; Yang, T.; Wu, T.; Song, T.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Tian, J. A long noncoding RNA functions in high-light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in apple by activating ethylene synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Wang, X.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Song, L.Q.; Zhao, L.L.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. EIN3-LIKE1, MYB1, and ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR3 Act in a Regulatory Loop That Synergistically Modulates Ethylene Biosynthesis and Anthocyanin Accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Lian, Z.; Qian, L.; Yan, S.; Cao, B.; Qiu, Z. Ethylene Inhibits Anthocyanin Biosynthesis by Repressing the R2R3-MYB Regulator SlAN2-like in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, R.; Yin, L.; Gao, L.; Strid, A.; Qian, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; et al. Ethylene mediates the branching of the jasmonate-induced flavonoid biosynthesis pathway by suppressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in red Chinese pear fruits. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1223–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, V.; Devoto, A. Jasmonate signalling network in Arabidopsis thaliana: Crucial regulatory nodes and new physiological scenarios. New Phytol. 2008, 177, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Cherono, S.; An, J.-P.; Allan, A.C.; Han, Y. Colorful hues: Insight into the mechanisms of anthocyanin pigmentation in fruit. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1718–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudell, D.R.; Mattheis, J.P.; Fan, X.; Fellman, J.K. Methyl Jasmonate Enhances Anthocyanin Accumulation and Modifies Production of Phenolics and Pigments in ‘Fuji’ Apples. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. JASHS 2002, 127, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; Blanch, G.P.; Ruiz del Castillo, M.L. Postharvest treatment with (−) and (+)-methyl jasmonate stimulates anthocyanin accumulation in grapes. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, J.; Shang, H.; Meng, X. Effect of methyl jasmonate on the anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity of blueberries during cold storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C.; Olías, R.; Olías, J.M. Effect of Methyl Jasmonate on in Vitro Strawberry Ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3733–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Yu, B.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Teng, Y. Isolation and Expression Analysis of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Genes from the Red Chinese Sand Pear, Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai cv. Mantianhong, in Response to Methyl Jasmonate Treatment and UV-B/VIS Conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 32, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premathilake, A.T.; Ni, J.; Shen, J.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y. Transcriptome analysis provides new insights into the transcriptional regulation of methyl jasmonate-induced flavonoid biosynthesis in pear calli. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Song, S.; Ren, Q.; Wu, D.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Fan, M.; Peng, W.; Ren, C.; Xie, D. The Jasmonate-ZIM-Domain Proteins Interact with the WD-Repeat/bHLH/MYB Complexes to Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Anthocyanin Accumulation and Trichome Initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1795–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, L.Y.; Zhang, Z.W.; Xi, Z.M.; Huo, S.S.; Ma, L.N. Brassinosteroids Regulate Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in the Ripening of Grape Berries. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 34, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.M.; Zhang, Z.W.; Huo, S.S.; Luan, L.Y.; Gao, X.; Ma, L.N.; Fang, Y.L. Regulating the secondary metabolism in grape berry using exogenous 24-epibrassinolide for enhanced phenolics content and antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3056–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, C.; Ruan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, J.; Xi, Z. Exogenous 24-Epibrassinolide Interacts with Light to Regulate Anthocyanin and Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis in Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.). Molecules 2018, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, J.; Mazur, R.; Trebichalsky, P.; Lacko-Bartosova, M.; Losak, T.; Musilova, J.; Chlebo, P.; Kovacik, P. Effect of a polyamine biosynthesis inhibitor on the quality of grape and red wine. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahirad, S.; Gohari, G.; Mahdavinia, G.; Jafari, H.; Kulak, M.; Fotopoulos, V.; Alcázar, R.; Dadpour, M. Foliar application of chitosan-putrescine nanoparticles (CTS-Put NPs) alleviates cadmium toxicity in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Sultana: Modulation of antioxidant and photosynthetic status. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Yan, F.; Hu, Z.; Wei, S.; Lai, J.; Chen, G. Accumulation of Anthocyanin and Its Associated Gene Expression in Purple Tumorous Stem Mustard (Brassica juncea var. tumida Tsen et Lee) Sprouts When Exposed to Light, Dark, Sugar, and Methyl Jasmonate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreti, E.; Povero, G.; Novi, G.; Solfanelli, C.; Alpi, A.; Perata, P. Gibberellins, jasmonate and abscisic acid modulate the sucrose-induced expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, Y.; Lin, K.; Wu, W.; Duan, L.; Wang, P.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Cytokinin promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis via regulating sugar accumulation and MYB113 expression in Eucalyptus. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpad154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K.; Shin, D.H.; Choi, S.B.; Yoo, S.D.; Choi, G.; Park, Y.I. Cytokinins enhance sugar-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 2012, 34, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Das, P.K.; Jeoung, S.C.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, W.J.; Park, Y.I.; Yoo, S.D.; Choi, S.B.; et al. Ethylene suppression of sugar-induced anthocyanin pigmentation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1514–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Oh, J.E.; Noh, H.; Hong, S.W.; Bhoo, S.H.; Lee, H. The ethylene signaling pathway has a negative impact on sucrose-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Res. 2011, 124, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Liu, L.J. Blue light photoreceptor cryptochrome 1 promotes wood formation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Populus. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 2044–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Warnasooriya, S.N.; Montgomery, B.L. Mesophyll-localized phytochromes gate stress- and light-inducible anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 9, e28013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, K.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, K. Effect of Supplementary Light with Different Wavelengths on Anthocyanin Composition, Sugar Accumulation and Volatile Compound Profiles of Grapes. Foods 2023, 12, 4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.C.; Chen, W.K.; Wang, Y.; Bai, X.J.; Cheng, G.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J.; He, F. Effect of the Seasonal Climatic Variations on the Flavonoid Accumulation in Vitis vinifera cvs. ‘Muscat Hamburg’ and ‘Victoria’ Grapes under the Double Cropping System. Foods 2021, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesser, M.; Martinez, S.C.; Eitle, M.W.; Warth, B.; Andre, C.M.; Schuhmacher, R.; Forneck, A. The ripening disorder berry shrivel affects anthocyanin biosynthesis and sugar metabolism in Zweigelt grape berries. Planta 2018, 247, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoi, S.; Shi, M.; Sarah, G.; Weber, A.; Torregrosa, L.; Romieu, C. Time-Resolved Transcriptomics of Single Vitis vinifera Fruits: Membrane Transporters as Switches of the Double Sigmoidal Growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3105–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Jordan, B.; Creasy, G.; Zhu, Y.F. UV-B Radiation Induced the Changes in the Amount of Amino Acids, Phenolics and Aroma Compounds in Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot Noir Berry under Field Conditions. Foods 2023, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, N.; Guan, L.; Dai, Z.W.; Wu, B.H.; Lauvergeat, V.; Gomes, E.; Li, S.H.; Godoy, F.; Arce-Johnson, P.; Delrot, S. Berry ripening: Recently heard through the grapevine. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4543–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitayama, M.; Hashizume, K. Loss of anthocyanins in red-wine grape under high temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, C.; Zenoni, S.; Fasoli, M.; Pezzotti, M.; Tornielli, G.B.; Filippetti, I. Selective defoliation affects plant growth, fruit transcriptional ripening program and flavonoid metabolism in grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, F.; Phillip, F.O.; Liu, H. Combined Metabolome and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Accumulation of Anthocyanins in Grape Berry (Vitis vinifera L.) under High-Temperature Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouot, J.C.; Smith, J.P.; Holzapfel, B.P.; Walker, A.R.; Barril, C. Grape berry flavonoids: A review of their biochemical responses to high and extreme high temperatures. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Goltsev, V.; Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Ma, F. Anthocyanin concentration depends on the counterbalance between its synthesis and degradation in plum fruit at high temperature. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Jeong, S.T.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Effects of Temperature on Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Grape Berry Skins. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, T.; Zhang, J.; Xing, Y.; Tian, J.; Yao, Y. ROS1 promotes low temperature-induced anthocyanin accumulation in apple by demethylating the promoter of anthocyanin-associated genes. Hortic Res. 2022, 9, uhac007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.K.; Maurya, N.K.; Goswami, S.; Bardhan, K.; Singh, S.K.; Prakash, J.; Pradhan, S.; Kumar, A.; Chinnusamy, V.; Kumar, P.; et al. Physio-biochemical and molecular stress regulators and their crosstalk for low-temperature stress responses in fruit crops: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1022167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Mu, L.; Yan, G.L.; Liang, N.N.; Pan, Q.H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.Q. Biosynthesis of anthocyanins and their regulation in colored grapes. Molecules 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Gucci, R.; D’Onofrio, C. The effect of regulated deficit irrigation on growth, yield, and berry quality of grapevines (cv. Sangiovese) grafted on rootstocks with different resistance to water deficit. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 41, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]