Decoupling Microbial Activity from Metabolite Action: A Comparative Assessment of EM Technology and Its Cell-Free Extract as Nature-Based Solutions for Plant Biostimulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mesocosm Set-Up

2.2. Microbial and Extract Inoculum

2.3. Plant Growth Parameters

2.4. Soil Samplings and Analyses

2.4.1. Culture-Based Analysis

2.4.2. Metabolomic Analyses

2.4.3. Metabarcoding Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.5.1. Plant and Soil Parameters

2.5.2. Metagenomic Soil Analysis

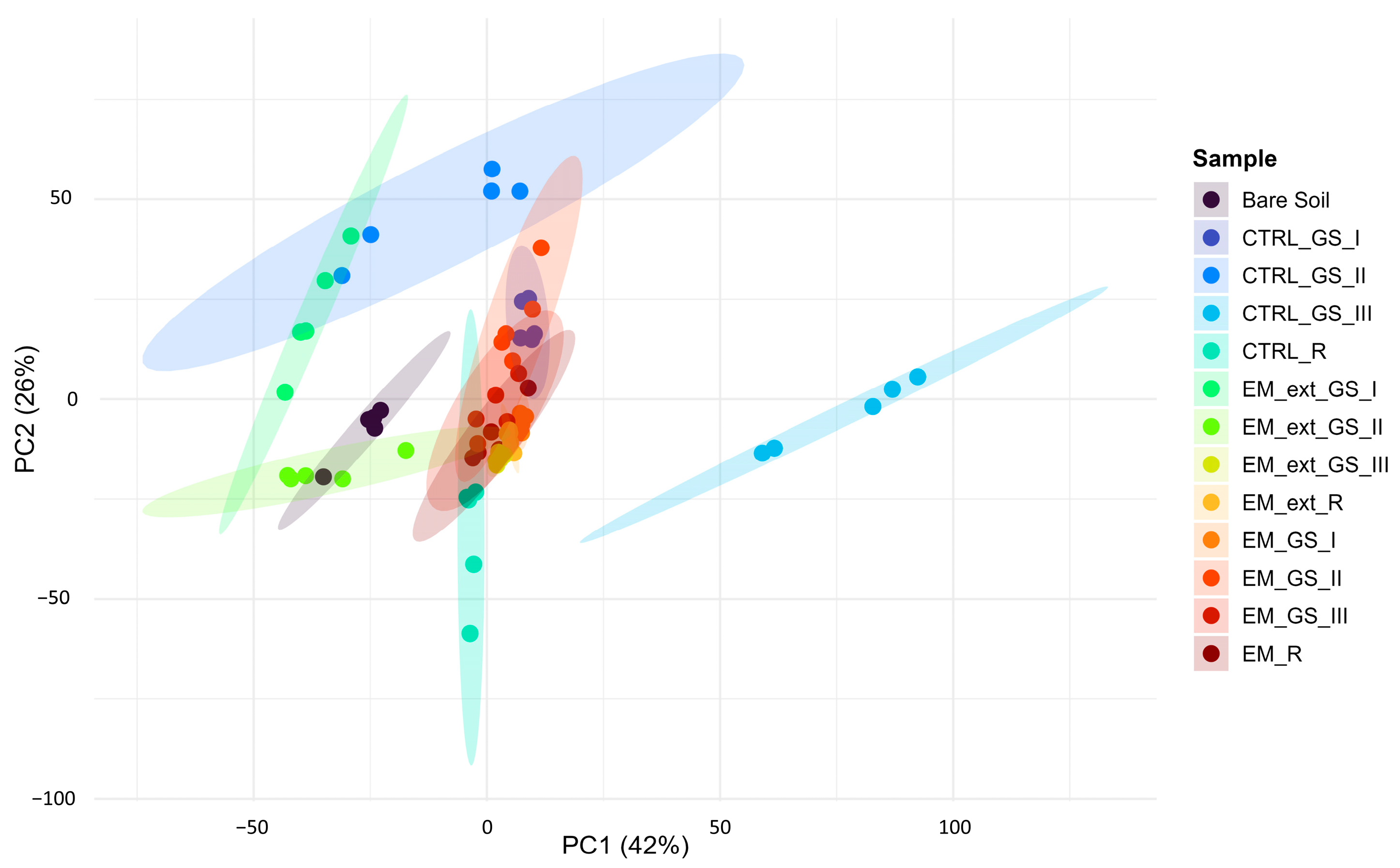

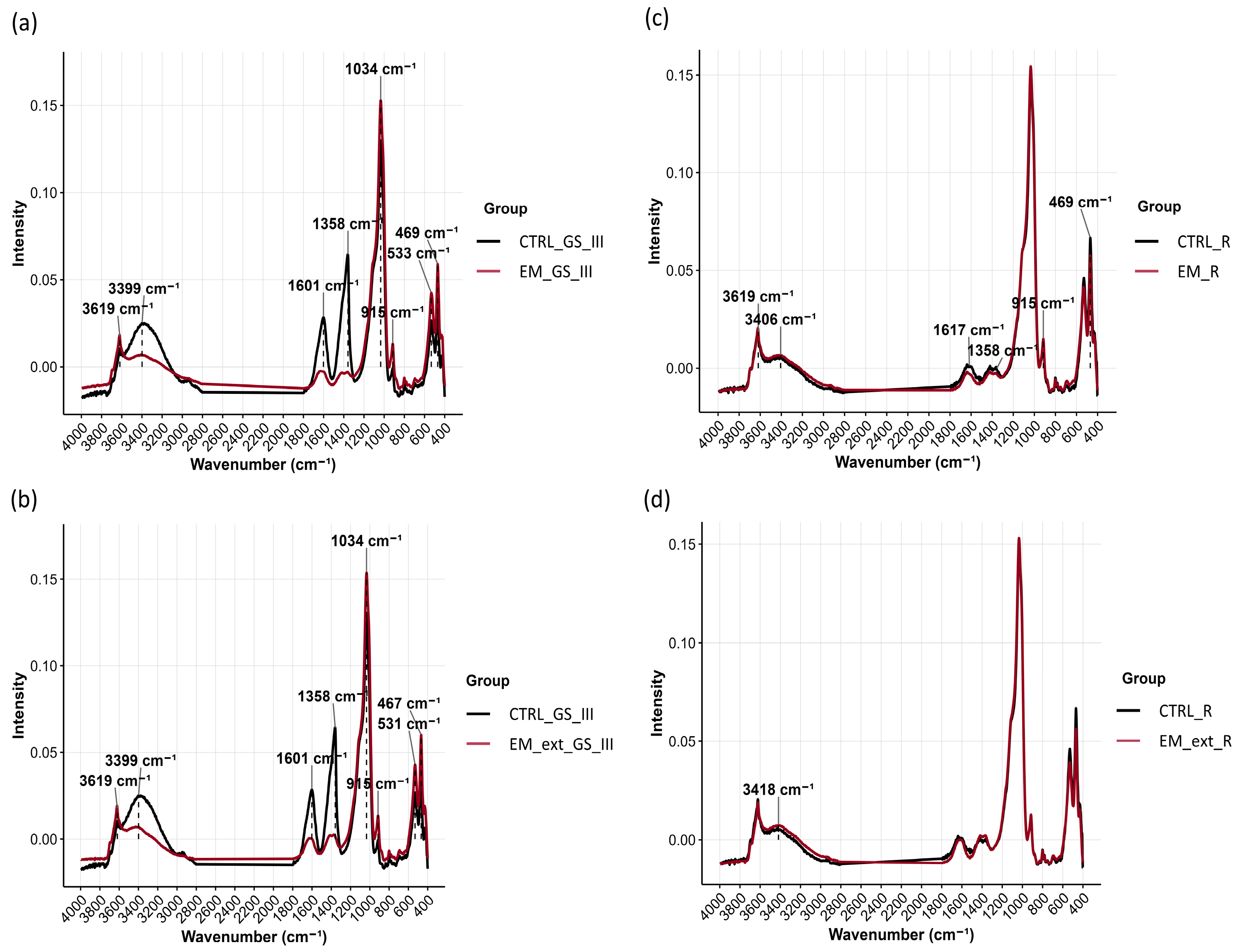

2.5.3. FTIR Spectral Data

3. Results

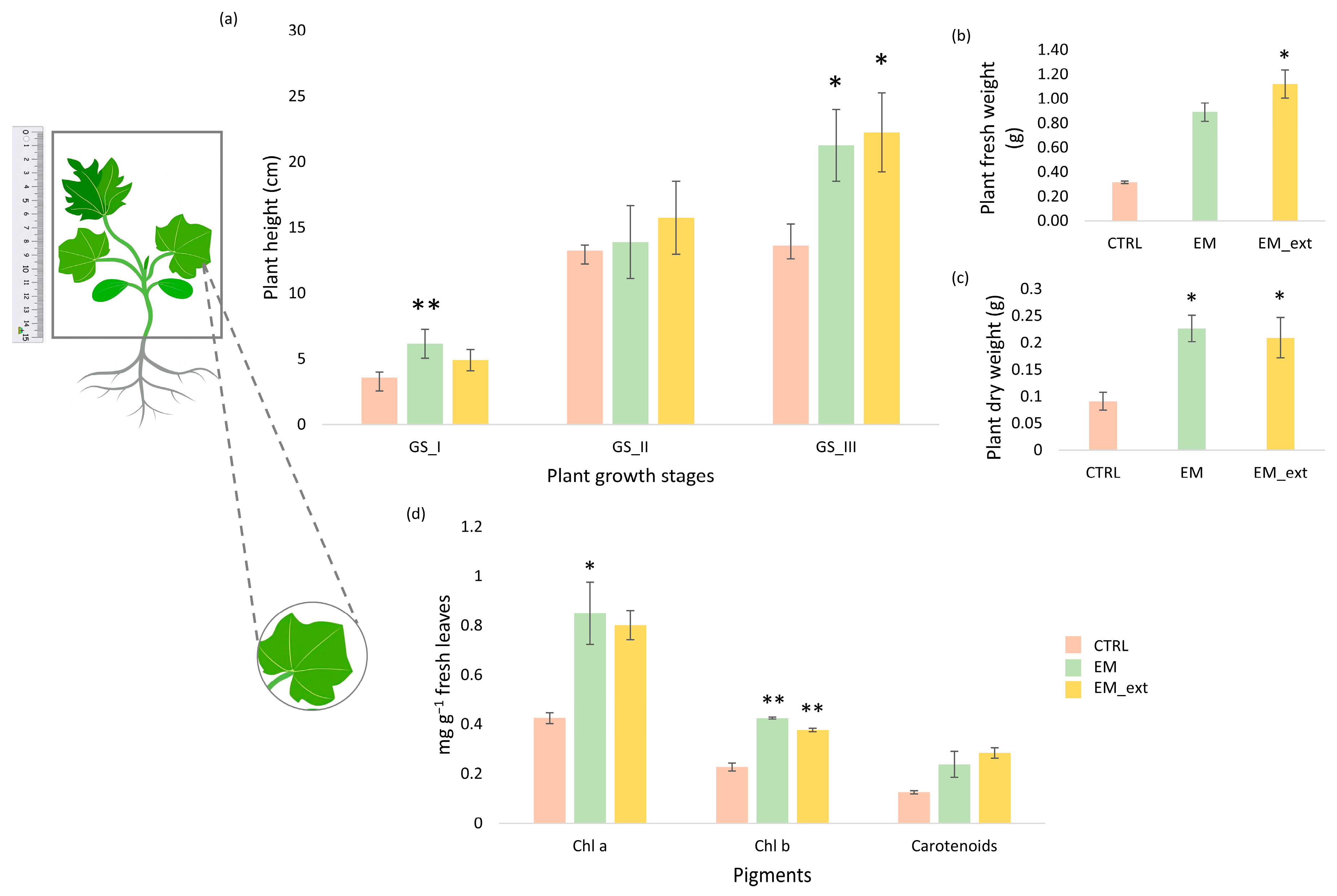

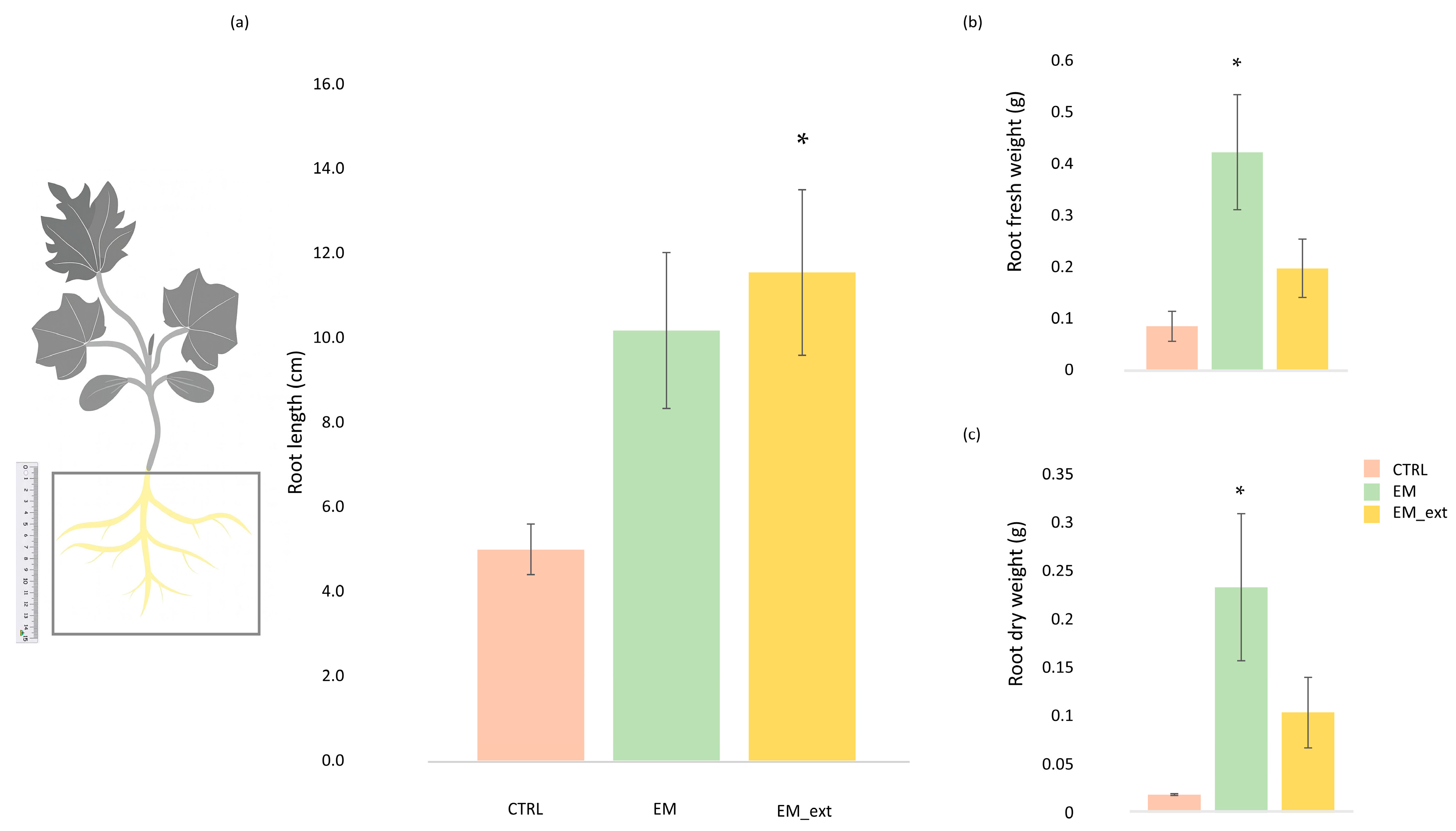

3.1. Impact of EM and EM Extract on Vegetative and Root Development of Zucchini Plants

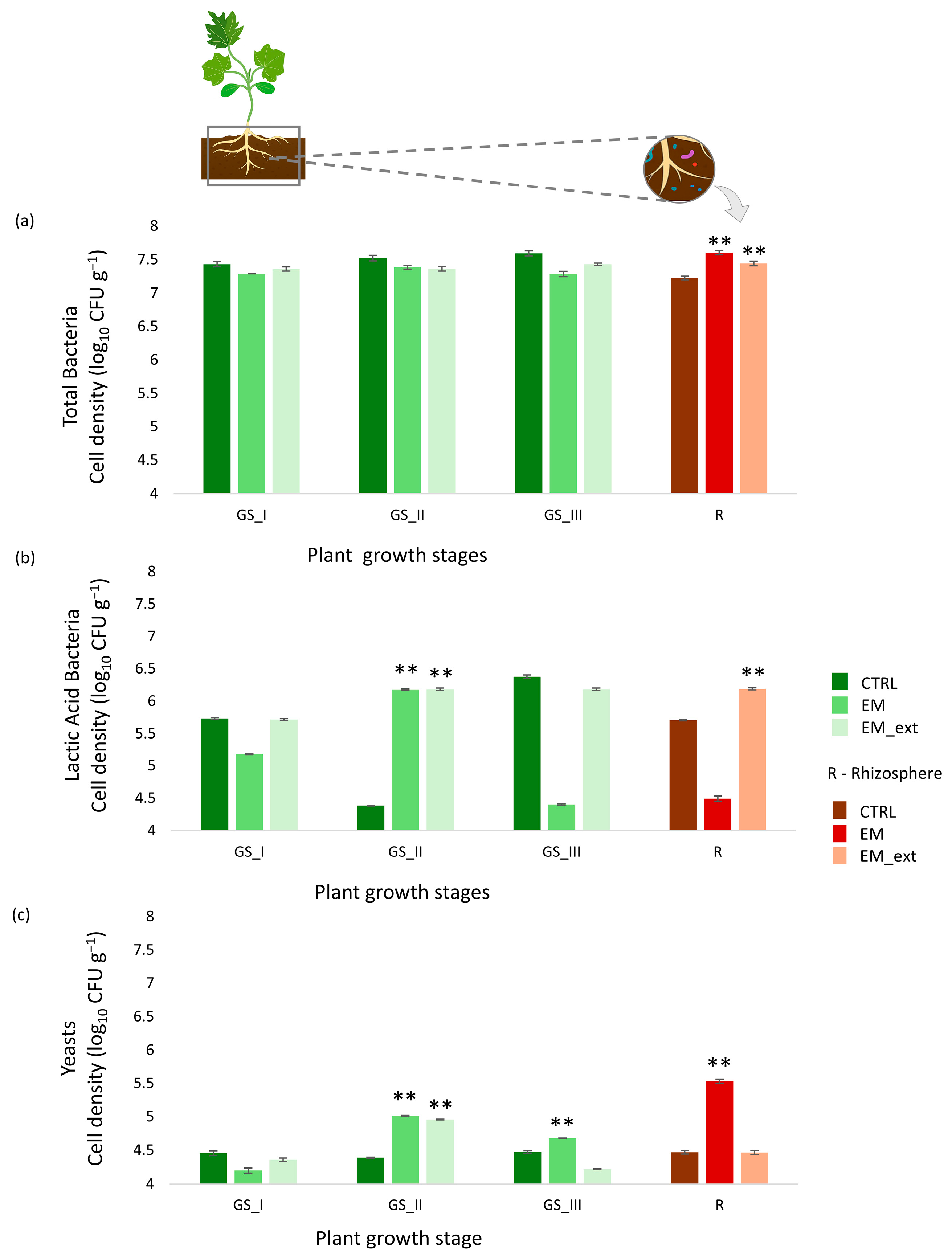

3.2. Dynamic of Microbial Cell Density in Soil and Rhizosphere Samples over Time

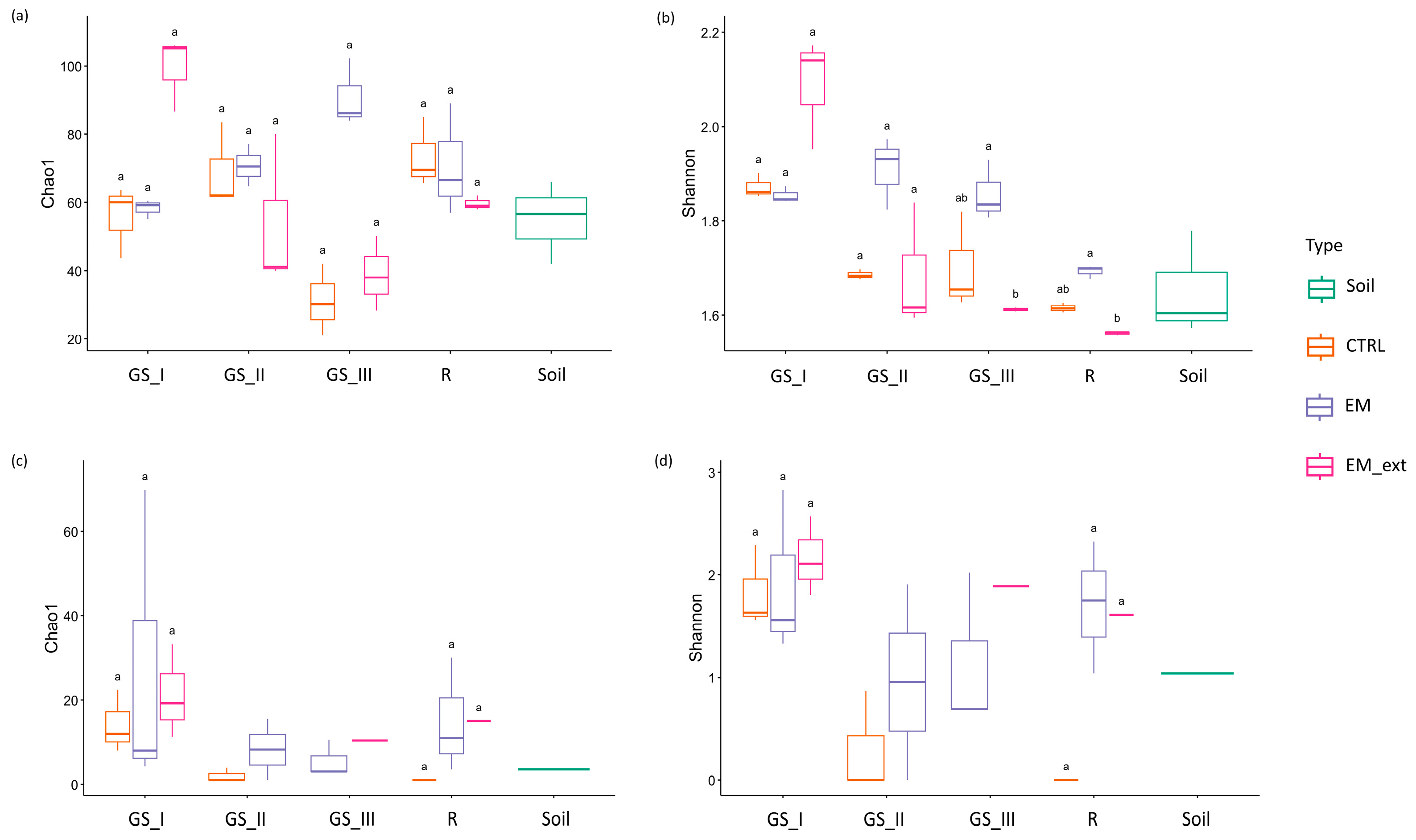

3.3. Metataxonomic Composition of Soil

3.4. Soil Meta-Metabolomic FTIR Profiling

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth and Physiological Responses to EM Treatments

4.2. Microbial Dynamic of Viable Cells in Soil Samples over Time

4.3. Impact of EM Treatments on Soil Microbiota Structure

4.4. EM Inoculation and Cell-Free Extract Alter Bulk and Rhizosphere Soil Metabolomic Profiles

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Effective Microorganism |

| EM Extract/EM_ext | Cell-free Effective Microorganisms extract |

| PGPR | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| BHI | Brain heart infusion medium |

| YPD | Yeast extract peptone dextrose medium |

| MRS | De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe medium |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CTRL | Control |

| GS_I | Plant Growth stage I—seedling emergence |

| GS_II | Plant Growth stage II—half growth |

| GS_III | Plant Growth stage III—advanced growth |

| R | Rhizosphere |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

References

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation agriculture as a sustainable system for soil health: A review. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikov, P.; Taboada, M.A.; Amanullah. Fertilizer use, soil health and agricultural sustainability. Agriculture 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Osemwegie, O.O.; Ibaba, A.L.; Daramola, F.Y.; Olaniyan, F.T.; Lewu, F.B.; Babalola, O.O. The importance of soil microorganisms in regulating soil health. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 55, 2636–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Kuai, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Hong, H. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms for soil health and ecosystem sustainability: A forty-year scientometric analysis (1984–2024). Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1546852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Niu, B. Microbial interactions within beneficial consortia promote soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. The role of beneficial microorganisms in soil quality and plant health. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, O.M.; Castrillo, G.; Paredes, S.H.; González, I.S.; Dangl, J.L. Understanding and exploiting plant beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimsi, K.A.; Manjusha, K.; Kathiresan, K.; Arya, H. Plant growth-promoting yeasts (PGPY), the latest entrant for use in sustainable agriculture: A review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxac088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, A.A.; Babalola, O.O. Fungi that promote plant growth in the rhizosphere boost crop growth. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoso, M.A.; Wagan, S.; Alam, I.; Hussain, A.; Ali, Q.; Saha, S.; Poudel, T.R.; Manghwar, H.; Liu, F. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on plant nutrition and root characteristics: Current perspective. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kaushal, G.; Borker, S.S.; Lepcha, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R. Physiological and genomic elucidation of cold-resilient rhizobacteria reveals plant growth promotion by siderophore optimization and enhanced biocontrol potential against fungal pathogens. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 44, 6953–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, S.A. Mechanisms of action and biocontrol potential of Trichoderma against fungal plant diseases: A review. Ecol. Complex. 2022, 49, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruspi, C.; Pierantoni, D.C.; Conti, A.; Scarponi, R.; Corte, L.; Cardinali, G. Plant Growth-Promoting Yeasts (PGPYs) as a sustainable solution to mitigate salt-induced stress on zucchini plant growth. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Hillel, D. Soils and global climate change: Challenges and opportunities. Soil Sci. 2000, 165, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 72, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, C.; Matschullat, J.; Zurba, K.; Zimmermann, F.; Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review. Geochemistry 2016, 76, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.P.; Singh, K.R.; Nagpure, G.; Mansoori, A.; Singh, R.P.; Ghazi, I.A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, J. Plant–soil–microbe: A tripartite interaction for nutrient acquisition and plant growth. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.; Lakshmanan, V.; Labbé, J.L.; Craven, K.D. Microbe to microbiome: A paradigm shift in the application of microorganisms for sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 622926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, E.; Gholamhosseini, M.; Yaghoubian, Y.; Pirdashti, H. Plant growth promoting microorganisms can improve germination, seedling growth and potassium uptake of soybean under drought and salt stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 90, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.; Sar, K.; Kumar Sahoo, B.; Mahapatra, P. Beneficial effect of effective microorganism on crop and soil: A review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 3070–3074. [Google Scholar]

- Prisa, D.; Jamal, A. Comprehensive analysis of effective microorganisms: Impacts on soil, plants, and the environment. Multidiscip. Rev. 2025, 8, 2025318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeagu, G.; Omotosho, A.; Suleiman, K. Effective microorganisms: A review of their products and uses. Nile J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 1, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.; Duttand, S.; Choudhary, P.; Mundra, S. Role of effective microorganisms (EM) in sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Acharya Narendar Deva, G.; Mahtab Rashid, M.; Nanda, S.; Kumar, G.; Rashid, M. Beneficial microorganisms for stable and sustainable agriculture. Biopestic. Int. 2021, 17, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Nuti, M. Ecosystem functions of microbial consortia in sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M.; Ballard, R.A.; Wright, D. Soil microbial inoculants for sustainable agriculture: Limitations and opportunities. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruspi, C.; Pierantoni, D.C.; Conti, A.; Favaro, L.; Antinori, M.E.; Puglisi, E.; Corte, L.; Cardinali, G. Beneficial effects of plant growth-promoting yeasts (PGPYs) on the early stage of growth of zucchini plants. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 39, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, D.; Magkana, P.; Yfantopoulos, D.; Kalozoumis, P.; Ntatsi, G. Growth and nutritional responses of zucchini squash to a novel consortium of six Bacillus sp. strains used as a biostimulant. Agronomy 2024, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, E.; Eris, A. Changes of micronutrients, dry weight, and chlorophyll contents in strawberry plants under salt stress conditions. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2005, 36, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebeneichler, S.C.; Barbosa, J.S.; Cruz, A.M.M.; Ramos, M.A.D.; Fernandes, H.E.; Nascimento, V.L. Comparison between extraction methods of photosynthetic pigments in Acacia mangium. Commun. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscini, L.; Corte, L.; Antonielli, L.; Rellini, P.; Fatichenti, F.; Cardinali, G. Influence of cell geometry and number of replicas in the reproducibility of whole cell FTIR analysis. Analyst 2010, 135, 2099–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, A.; Szymański, W.; Klimek, M. Impact of conventional agriculture on concentration and quality of water-extractable organic matter (WEOM) in surface horizons of Retisols. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 204, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Liang, M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Rhizobacteria protective hydrogel to promote plant growth and adaption to acidic soil. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artz, R.R.E.; Chapman, S.J.; Campbell, C.D. Substrate utilisation profiles of microbial communities in peat are depth dependent and correlate with whole soil FTIR profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2958–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyan, M.S.; Rasche, F.; Schulz, E.; Breulmann, M.; Müller, T.; Cadisch, G. Use of specific peaks obtained by DRIFTS to study organic matter composition in a Haplic Chernozem. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2012, 63, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Q.; Feng, Y.; Li, H. Effects of silicate-bacteria pretreatment on desiliconization of magnesite by reverse flotation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 544, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker, R.; Shmulevich, I.; Kenny, A.; Shaviv, A. Soil identification and chemometrics for direct determination of nitrate in soils using FTIR-ATR mid-infrared spectroscopy. Chemosphere 2005, 61, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltre, C.; Gregorich, E.G.; Bruun, S.; Jensen, L.S.; Magid, J. Repeated application of organic waste affects soil organic matter composition: Evidence from thermal analysis, FTIR-PAS, amino sugars and lignin biomarkers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 104, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, C.; Ma, F.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, J. Forensic soil analysis using LIBS and FTIR-ATR: Principles and case studies. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 310, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Wang, Q.; Abbasi, P.; Ma, Y. Deciphering chemical and microbial differences of healthy and Fusarium wilt-infected watermelon rhizosphere soils. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Qi, Y. Long-term effective microorganisms application promote growth and increase yields and nutrition of wheat in China. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 46, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, F.; Tomasz, K.; Justyna, K. Impact of effective microorganisms on yields and nutrition of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and microbiological properties of the substrate. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 7, 5756–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olle, M. The effect of effective microorganisms on the performance of tomato transplants. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 11, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Megali, L.; Schlau, B.; Rasmann, S. Soil microbial inoculation increases corn yield and insect attack. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommonaro, G.; Abbamondi, G.R.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A.; D’angelo, C.; Iodice, C.; De Prisco, R. Productivity and Nutritional Trait Improvements of Different Tomatoes Cultivated with Effective Microorganisms Technology. Agriculture 2021, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Qadri, T.A.; Khan, N. Bioactive metabolites of plants and microbes and their role in agricultural sustainability and mitigation of plant stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 159, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Scarafoni, A.; Pierce, S.; Castorina, G.; Vitalini, S. Soil application of effective microorganisms maintains leaf photosynthetic efficiency and improves seed yield and quality traits of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouphael, Y.; Formisano, L.; Ciriello, M.; Cardarelli, M.T.; Luziatelli, F.; Ruzzi, M.; Ficca, A.G.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Natural biostimulants as upscale substitutes to synthetic hormones for boosting tomato yield and fruits quality. Italus Hortus 2021, 28, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H.; Saka, A.K.; Uçan, U.; Akgün, İ.H.; Yalçı, H.K. Impact of effective micro-organisms (EM) on the yield, growth and bio-chemical properties of lettuce when applied to soil and leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesdeoca-Flores, D.; Alfayate-Casañas, C.; Hernández-Bolaños, E.; Hernández-González, M.; Estupiñan-Afonso, Z.; Abreu-Acosta, N. Effect of biofertilizers and rhizospheric bacteria on growth and root ultrastucture of lettuce. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2024, 65, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil microorganisms: Their role in enhancing crop nutrition and health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwat, S.M.; Matta, M.E. Environmental applications of effective microorganisms: A review of current knowledge and recommendations. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2021, 68, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, P.; Wierzchowski, P.S.; Dobrzyński, J.; Kulkova, I.; Wróbel, B.; Wiatkowski, M.; Kuriqi, A.; Skorulski, W.; Kabat, T.; Prycik, M.; et al. Effective microorganism water treatment method for rapid eutrophic reservoir restoration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 2377–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, N.S.; Jawan, R.; Chong, K.P. The potential of lactic acid bacteria in controlling plant diseases and stimulating plant growth: A mini review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1047945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi Khanghahi, M.; Strafella, S.; Filannino, P.; Minervini, F.; Crecchio, C.; Strafella, S. Importance of lactic acid bacteria as an emerging group of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in sustainable agroecosystems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzhevskaya, V.S.; Omelchenko, A.V.; Bugara, I.A.; Gusev, A.N.; Kryzhko, A.V.; Pashtetskiy, V.S. Influence of a microbial consortium of lactic acid bacteria and yeast on grain yield and quality of major crops. Agricult. Bull. Urals 2025, 25, 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, R.P.; Yamunasri, P.; Balachandar, D.; Murugananthi, D. Potentials of soil yeasts for plant growth and soil health in agriculture: A review. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytruk, O.; Yemets, A.; Dmytruk, K. Yeasts as biofertilizers and biocontrol agents: Mechanisms and applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wei, J.; Shao, X.; Yan, X.; Liu, K. Effective microorganisms improve vegetation and microbial community of degraded alpine grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franagal, J.; Ligęza, S.; Smal, H. Impact of effective microorganisms application on the physical condition of Haplic Luvisol. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande Pierantoni, D.; Conti, A.; Corte, L.; Tosti, G.; Benincasa, P.; Cardinali, G.; Guiducci, M. Microbial community dynamics in rotational cropping: Seasonality vs. crop-specific effects. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1675394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, S.; Groos, M.; Hannula, S.E.; Biere, A. Bioinoculant-induced plant resistance is modulated by resident soil microbial interactions. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiquia-Arashiro, S.; Li, X.; Pokhrel, K.; Kassem, A.; Abbas, L.; Coutinho, O.; Kasperek, D.; Najaf, H.; Opara, S. Applications of Fourier Transform-Infrared spectroscopy in microbial cell biology and environmental microbiology: Advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1304081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Rhizosphere size and shape: Temporal dynamics and spatial stationarity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Onaolapo, A.O.; Ibaba, A.L. Cell free supernatant for sustainable crop production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1549048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, R.J.L.; Baroja-Fernández, E.; López-Serrano, L.; Leal-López, J.; Muñoz, F.J.; Bahaji, A.; Férez-Gómez, A.; Pozueta-Romero, J. Cell-free microbial culture filtrates as biostimulants to enhance plant growth and activate beneficial microbiota. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1040515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Umer, M.J.; Hong, Y.; Jin, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Lu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, H. Soil derived metabolic profiling and their impact on the root growth in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnpuu, S.; Astover, A.; Tõnutare, T.; Penu, P.; Kauer, K. Soil organic matter qualification with FTIR spectroscopy under different soil types in Estonia. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 28, e00483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, A.; Poole, P. Role of root microbiota in plant productivity. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2167–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymański, W.; Bartos, A.; Klimek, M. Impact of agriculture on soil organic matter quantity and quality in Retisols: A case study from the Carpathian Foothills in Poland. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margenot, A.J.; Parikh, S.J.; Calderón, F.J. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for soil organic matter analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2023, 87, 1503–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Pan, Q.; Teng, P.; Yu, J.; Li, N. Soil organic matter stabilization along a black soil belt in Northeast China: An explanation using FTIR data. Catena 2023, 228, 107152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kong, L.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Lv, Y. Spectral characteristics changes as affected by inoculating microbial agents during composting. Soil Res. 2025, 63, SR24189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabugao, K.G.M.; Gushgari-Doyle, S.; Chacon, S.S.; Wu, X.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Bouskill, N.; Chakraborty, R. Natural organic matter transformations by microbial communities in subsurface ecosystems: Analytical techniques and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 864895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. The plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stojkov, K.; Conti, A.; Casagrande Pierantoni, D.; Scarponi, R.; Corte, L.; Cardinali, G. Decoupling Microbial Activity from Metabolite Action: A Comparative Assessment of EM Technology and Its Cell-Free Extract as Nature-Based Solutions for Plant Biostimulation. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121528

Stojkov K, Conti A, Casagrande Pierantoni D, Scarponi R, Corte L, Cardinali G. Decoupling Microbial Activity from Metabolite Action: A Comparative Assessment of EM Technology and Its Cell-Free Extract as Nature-Based Solutions for Plant Biostimulation. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121528

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojkov, Katarina, Angela Conti, Debora Casagrande Pierantoni, Roberto Scarponi, Laura Corte, and Gianluigi Cardinali. 2025. "Decoupling Microbial Activity from Metabolite Action: A Comparative Assessment of EM Technology and Its Cell-Free Extract as Nature-Based Solutions for Plant Biostimulation" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121528

APA StyleStojkov, K., Conti, A., Casagrande Pierantoni, D., Scarponi, R., Corte, L., & Cardinali, G. (2025). Decoupling Microbial Activity from Metabolite Action: A Comparative Assessment of EM Technology and Its Cell-Free Extract as Nature-Based Solutions for Plant Biostimulation. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121528