Comparative Analysis of the Cuticular Wax Morphology, Composition and Biosynthesis in Two Kumquat Cultivars During Fruit Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3. Epicuticular and Intracuticular Wax Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

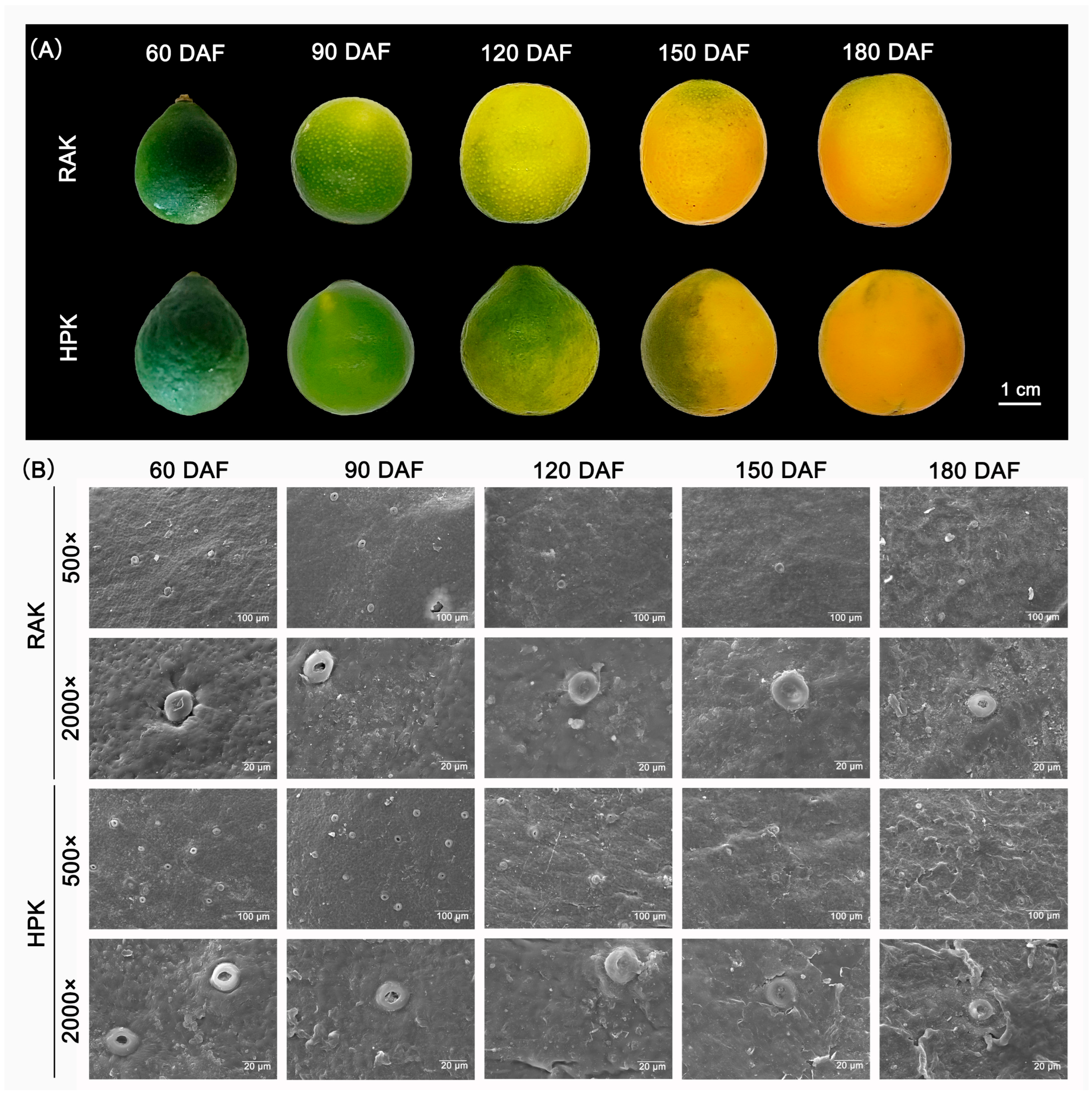

3.1. Crystal Morphology of HPK and RAK Fruit During Development

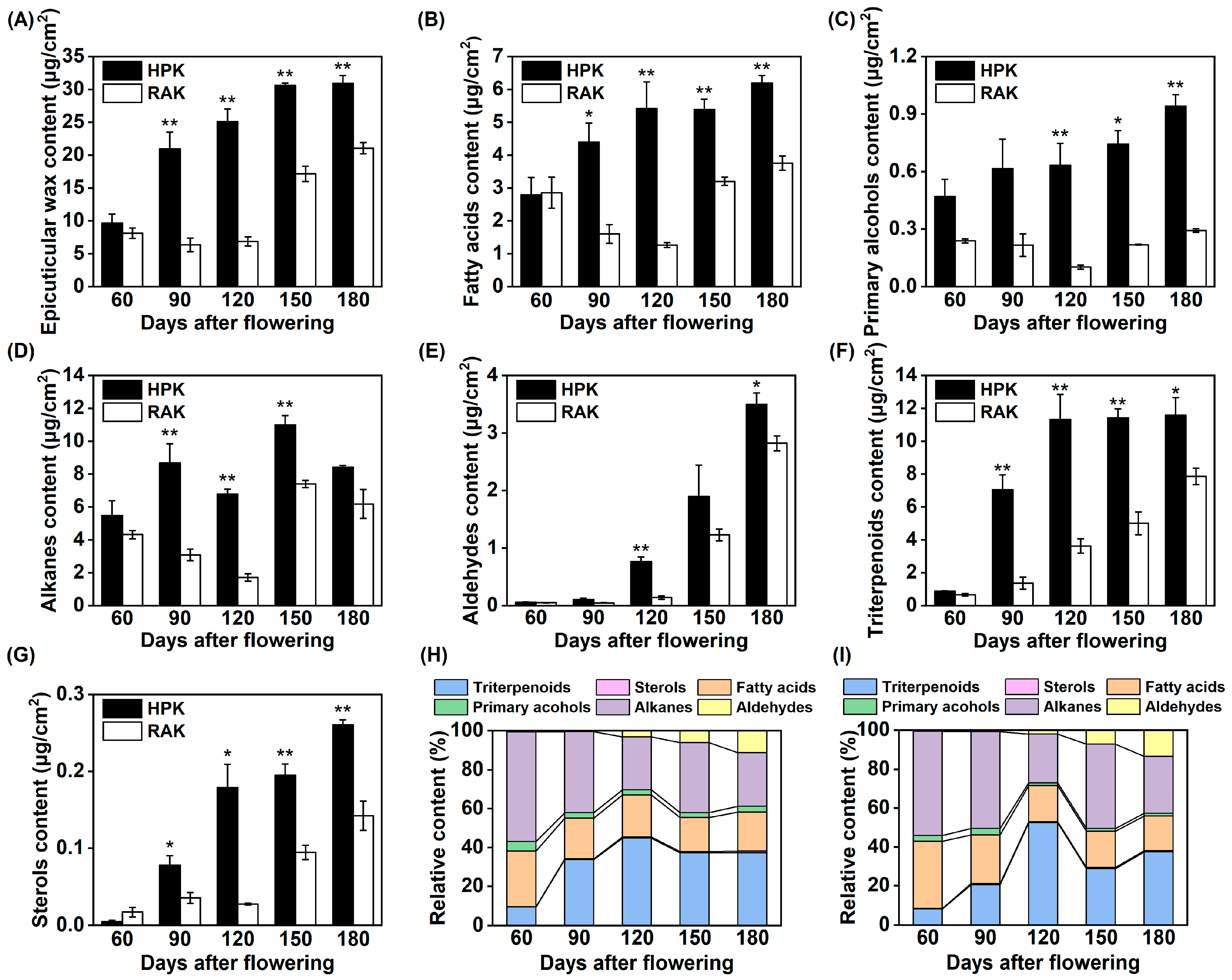

3.2. Changes in the Epicuticular Wax Compositions During Fruit Development

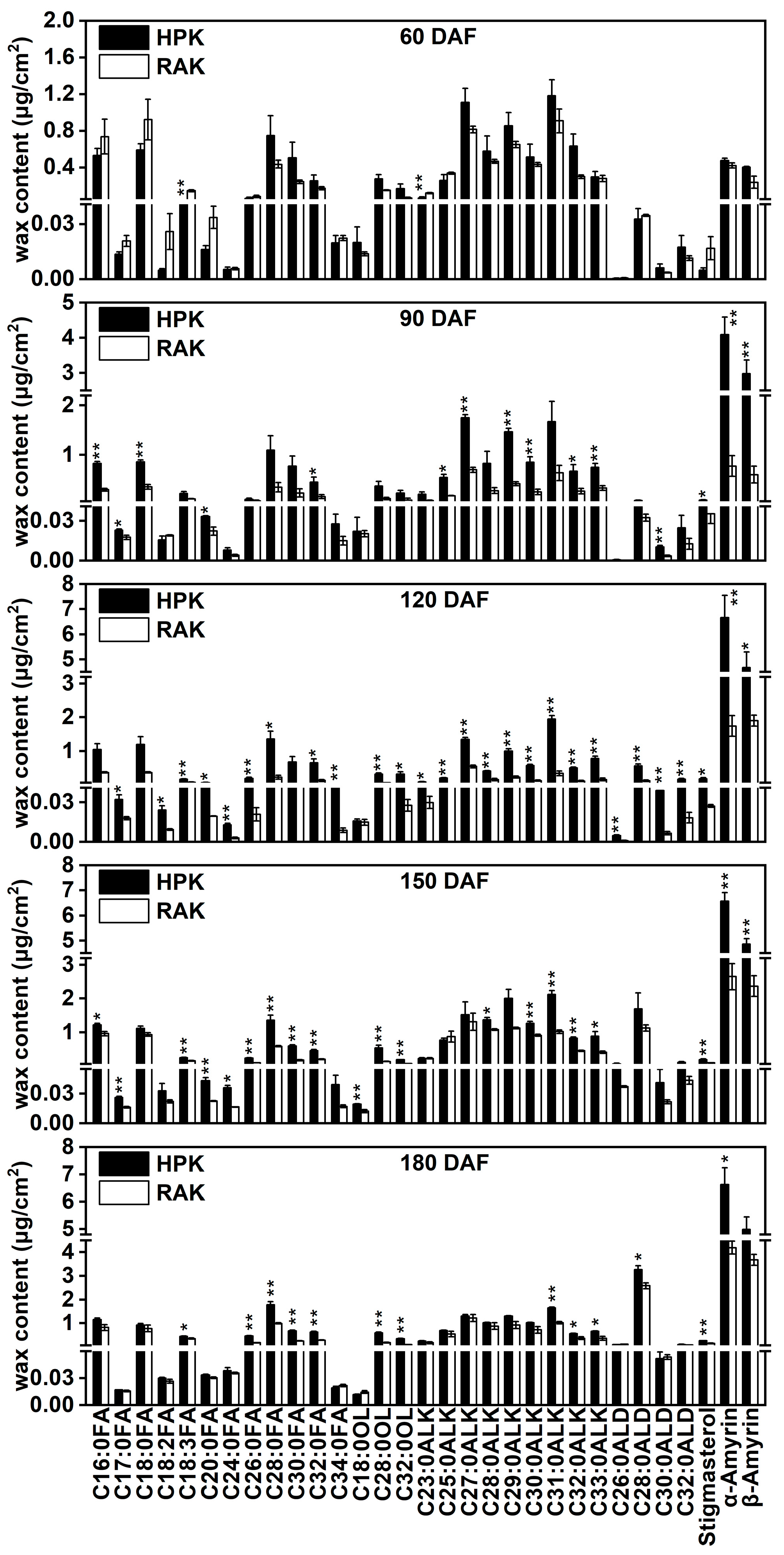

3.3. Changes in the Epicuticular Wax Constituents During Fruit Development

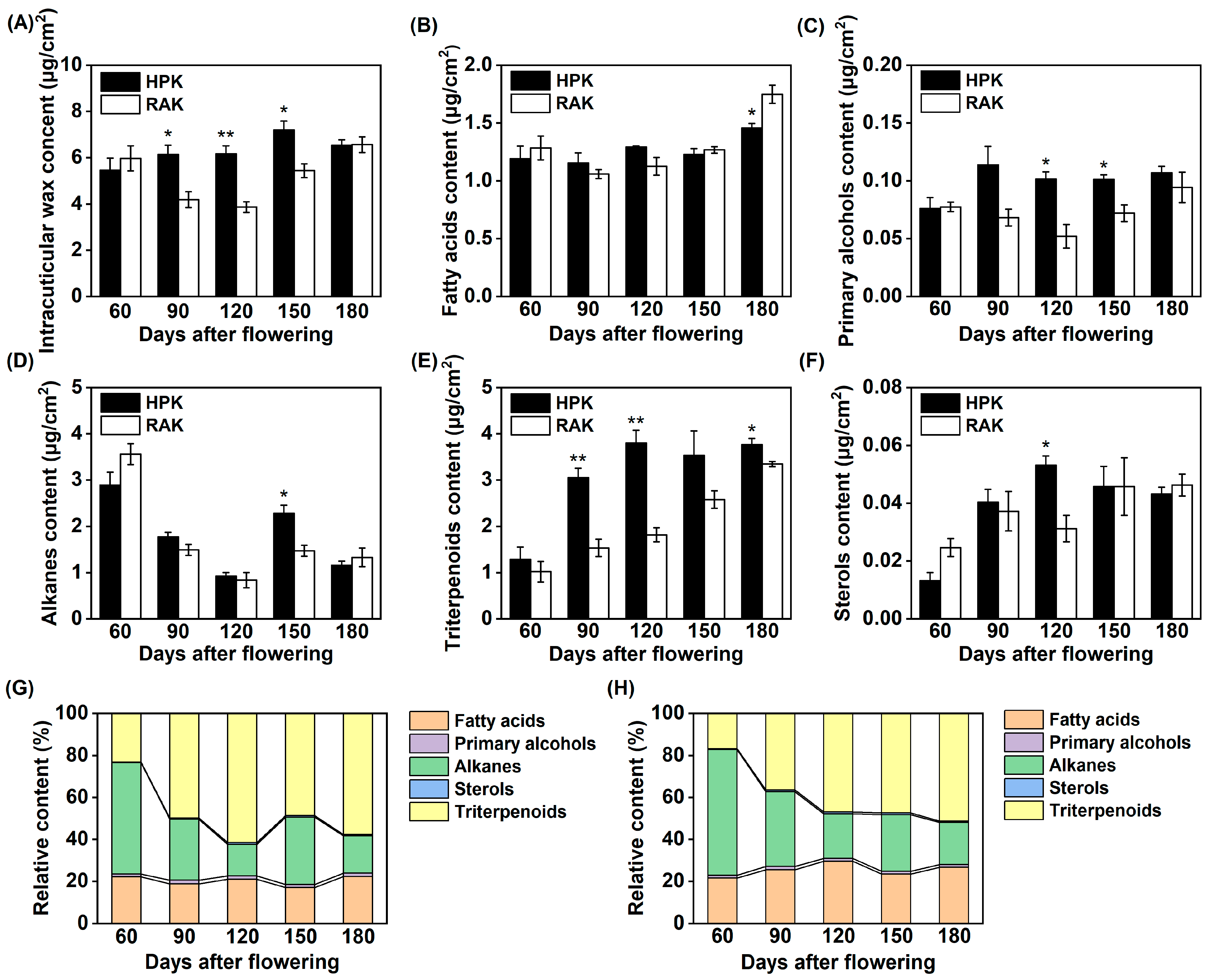

3.4. Changes in the Intracuticular Wax Compositions During Fruit Development

3.5. Changes in the Intracuticular Wax Constituents During Fruit Development

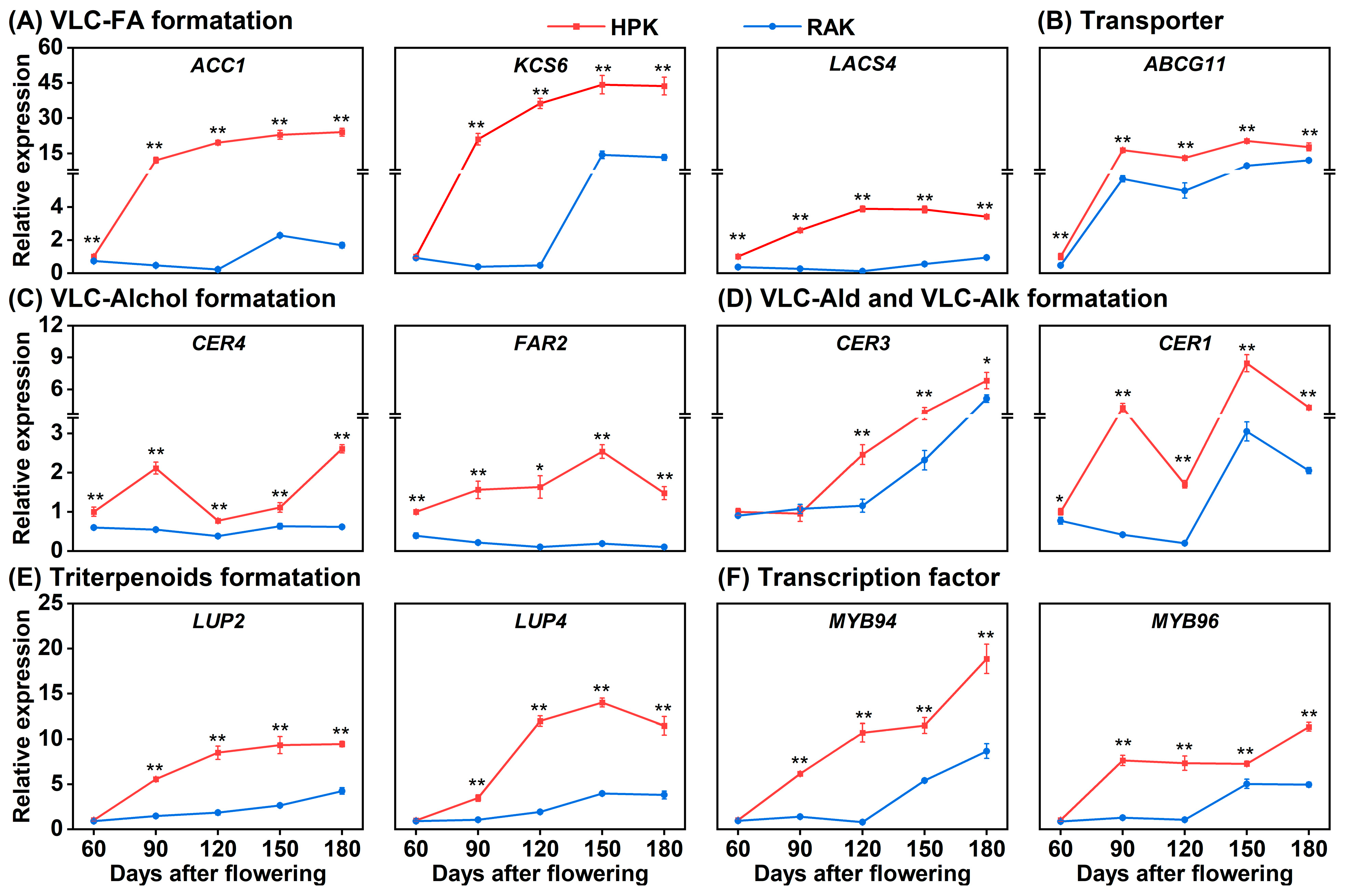

3.6. Expression Patterns of Genes Involved in Wax Formation During Fruit Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Chang, C. Interplays of cuticle biosynthesis and stomatal development: From epidermal adaptation to crop improvement. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25449–25461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, H.; Peng, Z.; Liu, R.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Fu, D. Composition, metabolism and postharvest function and regulation of fruit cuticle: A review. Food Chem. 2023, 411, 135449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Heredia, A.; Domínguez, E. The role of cuticle in fruit shelf-life. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 78, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeats, T.H.; Rose, J.K.C. The formation and function of plant cuticles. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.; Ensikat, H. The hydrophobic coatings of plant surfaces: Epicuticular wax crystals and their morphologies, crystallinity and molecular self-assembly. Micron 2008, 39, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, R.; Schäffer, S.; Riederer, M. Leaf cuticular waxes are arranged in chemically and mechanically distinct layers: Evidence from Prunus laurocerasus L. Plant Cell Environ. 2000, 23, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Buschhaus, C.; Jetter, R. Nanotubules on plant surfaces: Chemical composition of epicuticular wax crystals on needles of Taxus baccata L. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1808–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschhaus, C.; Jetter, R. Composition differences between epicuticular and intracuticular wax substructures: How do plants seal their epidermal surfaces? J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Z.; Bramlage, W.J. Developmental changes of cuticular constituents and their association with ethylene during fruit ripening in ‘Delicious’ apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2001, 21, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Fu, X.; Ali, M.; Song, Y.; Ding, J.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Yang, K.; et al. Transcriptome reveals insights into the regulatory mechanism of cuticular wax synthesis in developing apple fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Xie, L.; He, Y.; Luo, T.; Sheng, L.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; et al. Regulation of cuticle formation during fruit development and ripening in ‘Newhall’ navel orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) revealed by transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling. Plant Sci. 2016, 243, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zeng, Q.; Ji, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. A comparison of the ultrastructure and composition of fruits’ cuticular wax from the wild-type ‘Newhall’ navel orange (Citrus sinensis [L.] Osbeck cv. Newhall) and its glossy mutant. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.P.; Ohlrogge, J.B. A novel pathway for triacylglycerol biosynthesis is responsible for the accumulation of massive quantities of glycerolipids in the surface wax of bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) fruit. Plant. Cell. 2016, 28, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafolla-Arellano, J.C.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, H.; Jiao, C.; Ruiz-May, E.; Hernández-Oñate, M.A.; González-León, A.; Báez-Sañudo, R.; Fei, Z.; Domozych, D.; et al. Transcriptome analysis of mango (Mangifera indica L.) Fruit epidermal peel to identify putative cuticle-associated genes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peschel, S.; Franke, R.; Schreiber, L.; Knoche, M. Composition of the cuticle of developing sweet cherry fruit. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pensec, F.; Pączkowski, C.; Grabarczyk, M.; Woźniak, A.; Bénard-Gellon, M.; Bertsch, C.; Chong, J.; Szakiel, A. Changes in the triterpenoid content of cuticular waxes during fruit ripening of eight grape (Vitis vinifera) cultivars grown in the upper rhine valley. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7998–8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, N.; Tindjau, R.; Wong, D.C.J.; Matzat, T.; Haslam, T.; Song, C.; Gambetta, G.A.; Kunst, L.; Castellarin, S.D. Drought stress modulates cuticular wax composition of the grape berry. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3126–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Gagalova, K.K.; Gerbrandt, E.M.; Castellarin, S.D. Cuticular wax biosynthesis in blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.): Transcript and metabolite changes during ripening and storage affect key fruit quality traits. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, E.; López-Casado, G.; Cuartero, J.; Heredia, A. Development of fruit cuticle in cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Funct. Plant Biol. 2008, 35, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leide, J.; Hildebrandt, U.; Reussing, K.; Riederer, M.; Vogg, G. The developmental pattern of tomato fruit wax accumulation and its impact on cuticular transpiration barrier properties: Effects of a deficiency in a β-ketoacyl-coenzyme a synthase (LeCER6). Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz-Oron, S.; Mandel, T.; Rogachev, I.; Feldberg, L.; Lotan, O.; Yativ, M.; Wang, Z.; Jetter, R.; Venger, I.; Adato, A.; et al. Gene expression and metabolism in tomato fruit surface tissues. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Schulte, E.; Thier, H. Composition of the surface wax from tomatoes II. Quantification of the components at the ripe red stage and during ripening. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 219, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawełczyk, A.; żwawiak, J.; Zaprutko, L. Kumquat fruits as an important source of food ingredients and utility compounds. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Gu, Q. Identification of genes associated with soluble sugar and organic acid accumulation in ‘Huapi’ kumquat (Fortunella crassifolia Swingle) via transcriptome analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4321–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ren, J.; Zhou, S.; Duan, Y.; Zhu, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Xiang, S.; Xie, Z.; et al. Molecular regulation of oil gland development and biosynthesis of essential oils in Citrus spp. Science 2024, 383, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qiu, L.; Liu, D.; Kuang, L.; Hu, W.; Liu, Y. Changes in the crystal morphology, chemical composition and key gene expression of ‘Suichuan’ kumquat cuticular waxes after hot water dipping. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 293, 110753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, W.; Liu, D.; Qiu, L.; Kuang, L.; Song, J.; Huang, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y. Comparative analysis of the crystal morphology, chemical composition and key gene expression between two kumquat fruit cuticular waxes during postharvest cold storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 206, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhuang, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. Analysis of cuticular wax constituents and genes that contribute to the formation of ‘glossy Newhall’, a spontaneous bud mutant from the wild-type ‘Newhall’ navel orange. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 88, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, E.P.; Popopvsky, S.; Lohrey, G.T.; Lü, S.; Alkalai Tuvia, S.; Perzelan, Y.; Paran, I.; Fallik, E.; Jenks, M.A. Fruit cuticle lipid composition and fruit post-harvest water loss in an advanced backcross generation of pepper (Capsicum sp.). Physiol. Plant. 2012, 146, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, S.; Song, T.; Kosma, D.K.; Parsons, E.P.; Rowland, O.; Jenks, M.A. Arabidopsis CER8 encodes LONG-CHAIN ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE 1 (LACS1) that has overlapping functions with LACS2 in plant wax and cutin synthesis. Plant J. 2009, 59, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Maren, N.A.; Kosentka, P.Z.; Liao, Y.; Lu, H.; Duduit, J.R.; Huang, D.; Ashrafi, H.; Zhao, T.; Huerta, A.I.; et al. An optimized protocol for stepwise optimization of real-time RT-PCR analysis. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.A.; Procopiou, J. The cuticles of citrus species. Composition of leaf and fruit waxes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1975, 26, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Ou, S.; Shan, Y. Changes in cuticle compositions and crystal structure of ‘Bingtang’ sweet orange fruits (Citrus sinensis) during storage. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 2411–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Miao, J.; Zhang, B.; Duan, M.; Li, J.; Yue, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, H.G.; Xu, R.; Zhou, D.; et al. Cuticular wax metabolism of lemon (Citrus limon burm. F. Eureka) fruit in response to ethylene and gibberellic acid treatment. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 194, 112062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Lafuente, M.T. Relative humidity regimes modify epicuticular wax metabolism and fruit properties during navelate orange conservation in an ABA-dependent manner. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Yue, J.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Xu, R.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. Variations of membrane fatty acids and epicuticular wax metabolism in response to oleocellosis in lemon fruit. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weißinger, L.; Arand, K.; Bieler, E.; Kassemeyer, H.; Breuer, M.; Müller, C. Physical and chemical traits of grape varieties influence Drosophila suzukii preferences and performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 664636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogg, G.; Fischer, S.; Leide, J.; Emmanuel, E.; Jetter, R.; Levy, A.A.; Riederer, M. Tomato fruit cuticular waxes and their effects on transpiration barrier properties: Functional characterization of a mutant deficient in a very-long-chain fatty acid-ketoacyl-CoA synthase. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, B.P.; Grimm, E.; Finger, S.; Blume, A.; Knoche, M. Intracuticular wax fixes and restricts strain in leaf and fruit cuticles. New Phytol. 2013, 200, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisler, V.; Schreiber, L. Epicuticular wax on cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) leaves does not constitute the cuticular transpiration barrier. Planta 2016, 243, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, Y.; Patwari, P.; Stöcker, T.; Zeisler Diehl, V.; Steiner, U.; Campoli, C.; Grewe, L.; Kuczkowska, M.; Dierig, M.M.; Jose, S.; et al. Isolation and characterization of the gene HvFAR1 encoding acyl-CoA reductase from the cer-za.227 mutant of barley (Hordeum vulgare) and analysis of the cuticular barrier functions. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1903–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Hu, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Gu, Q.; Wei, Q. Metabolic profiling and gene expression analysis unveil differences in flavonoid and lipid metabolisms between ‘Huapi’ kumquat (Fortunella crassifolia Swingle) and its wild type. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 759968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthlott, W.; Neinhuis, C.; Cutler, D.; Ditsch, F.; Meusel, I.; Theisen, I.; Wilhelmi, H. Classification and terminology of plant epicuticular waxes. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1998, 126, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, H.; Liu, R.; Ma, Q.; Xu, J.; Chen, F.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, X. Comparative analysis of surface wax in mature fruits between Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu) and ‘Newhall’ navel orange (Citrus sinensis) from the perspective of crystal morphology, chemical composition and key gene expression. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, S.; Zhao, H.; Parsons, E.P.; Xu, C.; Kosma, D.K.; Xu, X.; Chao, D.; Lohrey, G.; Bangarusamy, D.K.; Wang, G.; et al. The glossyhead1 allele of ACC1 reveals a principal role for multidomain acetyl-coenzyme a carboxylase in the biosynthesis of cuticular waxes by arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Wu, Q.; Yang, L.; Hu, W.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y. Ectopic expression of CsKCS6 from navel orange promotes the production of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and increases the abiotic stress tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 564656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Haslam, T.M.; Sonntag, A.; Molina, I.; Kunst, L. Functional overlap of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. QTL analysis reveals the effect of CER1-1 and CER1-3 to reduce fruit water loss by increasing cuticular wax alkanes in citrus fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ayaz, A.; Zhao, H.; Lü, S. The plant fatty acyl reductases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Song, W.; Li, M.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Xue, Z. Natural products of pentacyclic triterpenoids: From discovery to heterologous biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1303–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimmappa, R.; Geisler, K.; Louveau, T.; O’Maille, P.; Osbourn, A. Triterpene biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 1, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Kim, H.U.; Suh, M.C. MYB94 and MYB96 additively activate cuticular wax biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 2300–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.; Wang, P.; Deng, X.; Xue, S.; et al. CsMYB96 confers resistance to water loss in citrus fruit by simultaneous regulation of water transport and wax biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, D.; Beisson, F.; Brigham, A.; Shin, J.; Greer, S.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Wu, X.; Yephremov, A.; Samuels, L. Characterization of Arabidopsis ABCG11/WBC11, an ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter that is required for cuticular lipid secretion. Plant J. 2007, 52, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Liu, D.; Hu, W.; Xiong, Z.; Kuang, L.; Song, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. Comparative Analysis of the Cuticular Wax Morphology, Composition and Biosynthesis in Two Kumquat Cultivars During Fruit Development. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121516

Huang Y, Qiu L, Liu D, Hu W, Xiong Z, Kuang L, Song J, Yang L, Liu Y. Comparative Analysis of the Cuticular Wax Morphology, Composition and Biosynthesis in Two Kumquat Cultivars During Fruit Development. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121516

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yingjie, Li Qiu, Dechun Liu, Wei Hu, Zhonghua Xiong, Liuqing Kuang, Jie Song, Li Yang, and Yong Liu. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of the Cuticular Wax Morphology, Composition and Biosynthesis in Two Kumquat Cultivars During Fruit Development" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121516

APA StyleHuang, Y., Qiu, L., Liu, D., Hu, W., Xiong, Z., Kuang, L., Song, J., Yang, L., & Liu, Y. (2025). Comparative Analysis of the Cuticular Wax Morphology, Composition and Biosynthesis in Two Kumquat Cultivars During Fruit Development. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121516