Abstract

Stem strength significantly influences ornamental plant output, ornamental value, and commodity prices. Lignin is a crucial component that confers mechanical strength to plant stems. In this study, an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor related to lignin synthesis was identified in Iris laevigata and named IlMYB86. The IlMYB86 protein is localized solely in the nucleus and functions as a transcriptional activator. Genetic transformation of IlMYB86 in tobacco resulted in taller plants with thicker stem diameter and increased stem pressure. In addition, the lignin content of the transgenic IlMYB86 tobacco plants increased, which was accompanied by the upregulation of 4CL and HCT, two key genes involved in lignin synthesis. Furthermore, IlMYB86 enhanced the photosynthetic capacity of transgenic tobacco by increasing the chlorophyll content, net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration rate. This study provides insight into the regulation of lignin biosynthesis, which could contribute to the molecular genetic engineering and breeding of ornamental plants.

1. Introduction

The stalk serves as the main supporting structure of the plant body, and the insufficient strength of the stalk seriously affects the yield and ornamental value of the plant. There is a close relationship between the chemical composition of plant stems, particularly the composition and content of cell walls, and stem strength. The plant cell wall is a dynamic network of several biopolymers and structural proteins, including cellulose, pectin, hemicellulose and lignin [1]. Lignin, in particular, is a crucial substance that affects the strength of plant stems, and its content is often a key indicator of lodging resistance. Previous studies in a variety of plants have shown that lignin is closely related to stem strength, with decreases in lignin content leading to reduced stem strength [2,3,4,5].

Lignin is a key structural component of plants, providing vascular integrity and mechanical strength [6]. It is a complex aromatic polymer formed by oxidative coupling of p-hydroxycinnamyl monomers and related compounds [7], consisting of three lignin monomers of guaiacyl, eugenyl and p-hydroxyphenyl [8]. The lignin biosynthesis pathway is generally described to involve three main pathways: the shikimic acid pathway, which produces phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan from glucose, a primary product of plant photosynthesis; the phenylpropanoid metabolism pathway, which converts phenylalanine to cinnamic acid and its acyl-CoA ester; and the reduction pathway, which converts cinnamoyl-CoA ester to lignin monomers [9,10,11]. These pathways involve a series of structural enzymes, including PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase), C4H (cinnamate-4-hydroxylase), 4CL (4-coumarate-CoA ligase), HCT (hydroxycinnamoyl transferase), C3H (coumarate 3-hydroxylase), CCoAOMT (caffeoyl-coenzyme A O-methyltransferases), F5H (ferulate 5-hydroxylase), COMT (caffeic acid O-methyltransferase), CCR (cinnamoyl-CoA reductase), and CAD (cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase) [12,13].

MYB transcription factors play a crucial role in regulating the lignin biosynthesis pathway during the growth and development of various plant species [14]. MYB46 and MYB83 have been identified as the main switches for lignin synthesis by regulating the expression of secondary wall biosynthesis genes to promote ectopic lignin deposition [15,16,17]. MYB58, MYB63, and MYB85, whose coding genes are direct targets of MYB46, function as direct transcriptional activators of lignin biosynthesis during secondary wall formation in Arabidopsis [18,19]. In contrast, some MYB transcription factors play a negative regulatory role in the biosynthesis of lignin. LlMYB1 is a repressor of the lignin biosynthesis pathway of Leucaena leucocephala that significantly decreases the transcript levels of lignin biosynthesis pathway genes and reduces lignin content when overexpressed [20]. The CmMYB8 protein in chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) negatively regulates both lignin and flavonoid synthesis, with its overexpression leading to the downregulation of several genes involved in these pathways, resulting in reduced lignin and flavonoid content [21]. Similarly, MYB6 interacts physically with KNAT7 to downregulate the expression levels of lignin biosynthetic genes, causing a dramatic reduction in lignin content in Populus tomentosa [22]. CfMYB25 from Cryptomeria fortunei Hooibrenk is also a transcriptional repressor, which negatively regulates lignin deposition [23]. These findings indicate that MYB transcription factors play important roles in lignin accumulation but differ in their positive or negative regulation.

I. laevigata is known for its distinctive flower shape, vibrant color, long stems, and strong lodging resistance, which significantly enhances its value and applicability as a cut flower. Improving plant stem strength through genetic engineering is highly effective, necessitating the exploration of relevant genetic resources. Here, we report that IlMYB86, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor in I. laevigata, regulates lignin biosynthesis. IlMYB86 protein is localized in the nucleus, and its overexpression in tobacco resulted in thicker, longer stems with enhanced compressive strength. In addition, the lignin content of the stems of the transgenic tobacco increased, accompanied by elevated expression of lignin synthesis-related genes. Moreover, the transfer of IlMYB86 leads to an increase in the chlorophyll content of tobacco and an increase in its photosynthetic capacity. This study provides a theoretical basis for the biosynthesis of lignin in I. laevigata and offers valuable resources for the molecular genetic engineering and breeding of other species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

I. laevigata plants were cultivated in the nursery of the School of Landscape Architecture, Northeast Forestry University. Seeds of Nicotiana tabacum were sterilized with 75% ethanol (LIRCON, Dezhou, China) on a super clean bench for 1 min, rinsed three times with sterile water, then disinfected with 2% NaClO (XiLONG, Shenzhen, China) for 10 min and rinsed five times with sterile water. Subsequently, they were placed on MS (Hope Bio-Technology, Qingdao, China) solid medium [24]. The plants were cultured at 25 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and were used for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation when they had 4-6 true leaves. The wild-type (WT), empty-vector (EV) line, transgenic tobacco and N. benthamiana plants were grown at 25 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and 60% relative humidity.

2.2. Gene Cloning and Bioinformatics

Total RNA was extracted from the flowers of I. laevigata plants using a Plant RNA Kit (OMEGA), and RNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with a Primer Script TM RT kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) and used as the DNA template. IlMYB86 was amplified using the KOD-Plus-Neo Kit (ToYoBo, Shanghai, China) with the primers IlMYB86-F and IlMYB86-R which were listed in Table S1. The amplified sequences were ligated to the T-Vector pMD19 (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α (WEIDI, Shanghai, China) for further sequencing.

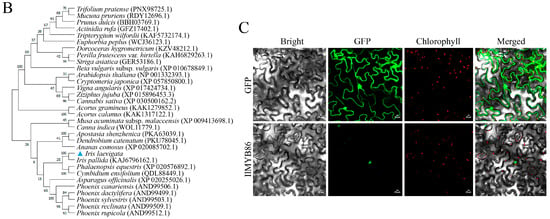

DNAMAN (version 9.0.1) was used to perform multiple protein sequence alignments of I. laevigata and other plants. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method using MEGA-X software (version 10.2.6) with a bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates. MYB86 protein sequences from other plants were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 22 December 2023). The experimental procedures were performed according to the instructions provided in the respective kits, and primer synthesis and sequencing were performed by RuiBiotech Inc. (Harbin, China).

2.3. Construction of Expression Vectors

IlMYB86 was cloned and inserted into pCAMBIA1300-GFP by homologous recombination. IlMYB86 was amplified with homologous arms by PCR using a KOD-Plus-Neo Kit (ToYoBo, Shanghai, China), and the homologous recombination primers pCAMBIA1300-F and pCAMBIA1300-R were listed in Table S1. Next, the SalI and BamHI enzymes (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) were selected for the linearization of the pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector, and the linearized product was recombined with the homologous arm amplification product using the ClonExpressII One-Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The recombinant pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP was transformed into E. coli DH5α (WEIDI, Shanghai, China) for sequencing. The positive binary pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP plasmid was subsequently transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (WEIDI, Shanghai, China). The experimental procedures were performed according to the instructions provided in the respective kits, and primer synthesis and sequencing were performed by RuiBiotech Inc. (Harbin, China).

2.4. Subcellular Localization

Subcellular localization was performed according to previously established methods [25]. A. tumefaciens containing pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP and the empty vector pCAMBIA1300-GFP were cultured and collected, and pCAMBIA1300-GFP was used as a control. Bacterial cells were resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 to an OD600 of 1.5, followed by the addition of acetosyringone to a final concentration of 200 µM. The bacterial solution was incubated for 3 h in the dark and then injected into the abaxial surface of N. benthamiana leaves using syringes. The injected N. benthamiana plants were cultured in the dark for 12 h, followed by 3 d in photoperiod. The expression of the MYB86-GFP fusion protein was observed via laser confocal microscopy (LSM800 with Airyscan, ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.5. Transformation of IlMYB86 in Tobacco

Transgenic lines were obtained by the Agrobacterium-mediated leaf disk transformation method [26]. A genomic DNA extraction kit (TianGen, Beijing, China) was used to extract the total DNA of the transformed tobacco plants, and positive plants were identified via PCR with homology arm primers (Table S1). The positive tobacco plants identified were the T0 generation, and their seeds were screened on MS media supplemented with 25 mg/L hygromycin B. Screening was repeated according to the above methods until T3 tobacco plants were obtained. Three overexpressing (OE) lines, designated OE-1, OE-2, and OE-3, were randomly selected for further experiments.

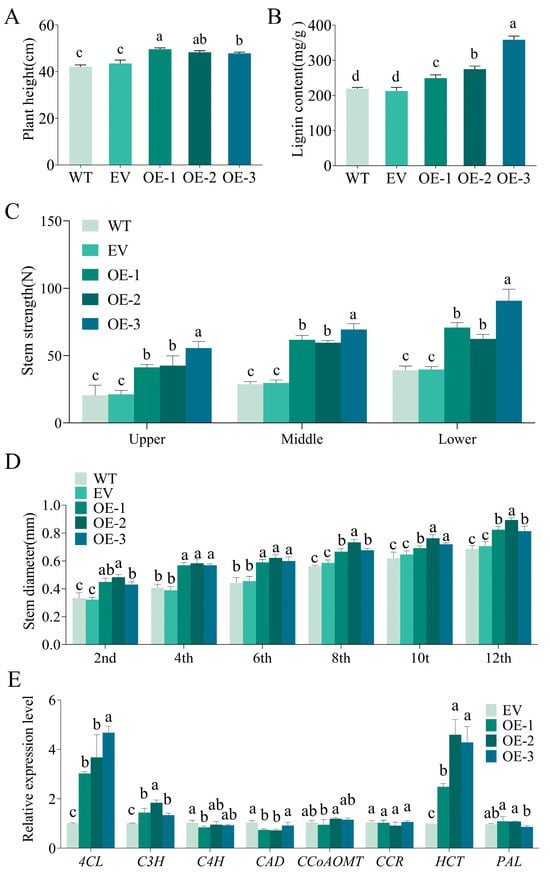

2.6. Phenotypic Data of the Transgenic IlMYB86 Tobacco Plants

WT, EV, and OE seedlings were transferred to soil and grown in a greenhouse under conditions of 25 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and 60% relative humidity. When these tobacco plants had grown for approximately 4 months (the stem scale of the plant was 11–13 nodes), their total stem length, and stem diameter were measured at different internodes. Using a double-sided blade, the stems of the 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th segments of tobacco stems of different strains were cut off (counting down from the top bud), and the stem diameter was measured at the cross-section with 0.01mm Vernier calipers. The compressive strength of the upper, middle, and lower stems of the tobacco plants was measured for the WT, EV and OE plants with a stem strength tester (Zhejiang TOP Cloud-agri Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). All measurements were independently repeated three times, with three biological replicates (individual plants) per line measured in each repeat. Data analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 26).

2.7. Physiological Data of the Transgenic IlMYB86 Tobacco Plants

The part of the tobacco stem that had been transplanted for 4 months was cut, completely dried in an oven at 60 °C, crushed into powder with a mortar and passed through a 40-mesh sieve. The lignin content (mg/g) of 3 mg of sample was measured using a Lignin Content Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The total chlorophyll content (mg/g) was measured using acetone extraction [26]. A portable photosynthesis meter (LI-6400, ecotek, Beijing, China) was used to measure the net photosynthetic rate (µmol/m2·s), stomatal conductance (µmol/m2·s), intercellular CO2 concentration (µmol CO2/mol), and transpiration rate (µmol/m2·s) of the WT and IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants at the seedling stage, preflowering stage and full flowering stage, following an established procedure [27]. The measurements were conducted at midday under the following conditions: a light intensity (photosynthetically active radiation, PAR) of 1000–2000 μmol·m−2·s−1, a temperature of 25 °C, and a 16/8 h light/dark cycle.

2.8. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription to cDNA were performed as described above for total RNA extraction and reverse transcription. NtTUBA was used as the reference transcript. RT-qPCR was performed using the SYBR Green I method. The specific experimental procedures were followed according to the instructions of the UltraSYBR Mixture (CWBIO, Beijing, China). The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method [28]. The quantitative primers used are listed in Table S1.

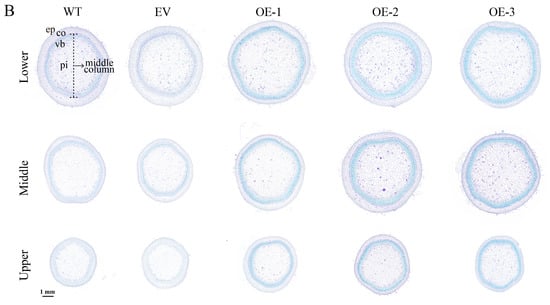

2.9. Anatomical Structure Studies of Tobacco Stems

Paraffin sections combined with aniline blue staining were used to observe the cross-sections of tobacco stems. The upper part (the stem segment of the 2nd–4th node from the top bud), the middle part (the stem segment of the 6th-8th node), and the lower part (the stem segment of the 10th–12th nodes) of the stems of the WT, EV and OE tobaccos were collected. The tissues were trimmed to 2–3 mm thickness, softened in a plant softening solution at 55 °C, and then processed through dehydration in a graded ethanol series, clearing in xylene, and infiltration with paraffin wax. Following embedding and solidification, the blocks were sectioned into 5 μm thick sections using a paraffin microtome (Zhejiang TOP Cloud-Agri Technology Co., Ltd.). Following deparaffinization and rehydration, the sections were stained with Safranin O, counterstained with Fast Green, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral balsam. Stained sections were examined and imaged under a microscope (Leica DM2255, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.10. Statistical Analyses

Excel (version 2021) was used for data recording and statistical analysis. The least significant difference method or one-way analysis of variance was used to test the confidence intervals (p < 0.05). Data analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26), and GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.0) was used to obtain the graphs.

2.11. Accession Numbers

Genes can be found with the following accession numbers: IlMYB86 (PP504912), NtTUBA (XM_016658252), NtPAL (NM_001325017), NtC4H (NM_001326168), Nt4CL (XM_075218837), NtC3H (NM_001326128), NtHCT (NM_001325623), NtCCoAOMT (NM_001425874), NtCCR (NM_001325978) and NtCAD (NM_001325758).

3. Results

3.1. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of IlMYB86

The full-length CDS of IlMYB86 was cloned and subsequently verified by sequencing (Figure S1). IlMYB86 contains a 1053 bp open reading frame encoding 350 amino acids (Figure S2) with a theoretical pI of 5.79 and a molecular weight of 38.73 kDa. Sequence alignment of IlMYB86 with other MYB86 genes revealed that IlMYB86 is a typical R2R3-MYB transcription factor that contains imperfect R2 and R3 repeats (Figure 1A). Phylogenetic analysis of the MYB86 proteins revealed that IlMYB86 shared 75.42% homology with the MYB86 protein of I. pallida (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis and subcellular localization of IlMYB86. (A) Sequence alignment of IlMYB86 with MYB86 proteins from orthologous plant proteins. The dark blue background color represents 100% homologous sequence, the pink background color represents ≥75% homologous sequence, the blue background color represents ≥50% homologous sequence. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of MYB86 proteins. The tree was constructed via the neighbor-joining method using MEGA-X software (version 10.2.6) with a bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates. The blue triangle indicates IlMYB86 from I. laevigata. (C) Subcellular localization of the IlMYB86 protein. The scale bar represents 20 μm.

3.2. IlMYB86-GFP Was Localized in the Nucleus

The recombinant vector pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP was constructed (Figure S3), verified by sequencing, introduced into A. tumefaciens (Figure S4), and transiently transformed into tobacco leaves. Laser confocal microscopy revealed that the fluorescence signal of the empty carrier pCAMBIA1300-GFP was present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, while the fluorescence signal of the IlMYB86 protein was localized solely in the nucleus (Figure 1C).

3.3. Influence of IlMYB86 Overexpression on Tobacco Phenotype

To further explore the biological role of IlMYB86, seven independent T0 transgenic tobacco lines were successfully generated (Figure S5), with a transformation efficiency of 46.67% (7 PCR-positive plants/15 regenerated antibiotic-resistant plantlets). Then, three lines (OE-1, OE-2, and OE-3) were randomly selected for subsequent tests (Figure 2A). Both WT and EV tobacco plants were used as controls. The transgenic plants were thicker than the WT and EV plants, so the phenotypic traits of the transgenic tobacco plants, including plant height, stem diameter, and stem strength, were measured, and the stem structure was observed.

Figure 2.

Phenotype and stem cross-sections of IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants. (A) Elevation of the WT, EV and three OE lines of tobacco. The scale bar is 20 cm. (B) Cross-sections of the upper, middle and lower stem parts of the WT, EV and three OE lines of tobacco. ep, epidermis; co, cortex; vb, vascular bundle; pi, pith. The scale bar represents 1 mm.

The plant height of the IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants was significantly bigger than that of the WT and EV plants, and there was no significant difference between the WT and EV plants (Figure 3A). The stem diameter of sections 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 of the transgenic tobacco plants from top to bottom were higher than those of the WT and EV plants (Figure 3D). Further measurement of stem strength revealed that the stem strength of the upper, middle and lower parts of the stems of the transgenic tobacco plants was significantly higher than that of the WT and EV plants (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Phenotypic data, lignin content and lignin biosynthesis pathway-related gene expression of IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants. (A) Plant heights of the WT, EV, and OE lines. (B) The lignin content of the WT, EV, and OE lines. (C) Stem strength of the upper, middle and lower parts of the WT, EV, and OE lines. (D) The stem diameter of sections 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 of the WT, EV, and OE lines from top to bottom. (E) Expression of genes encoding enzymes related to lignin synthesis in the EV and OE lines. Different letters on the bar chart represent significant differences, p < 0.05.

Paraffin sectioning technology and toluidine blue staining were used to observe the microstructure of cells in different stem parts of the transgenic tobacco, WT and EV plants. The cross-sections of the stems (Figure 2B) revealed that the basic structure of the transgenic IlMYB86 tobacco plants was the same as that of the WT and EV plants in the upper, middle and lower parts, which were composed of three parts: the epidermis, cortex (thick horn tissue and cortical thin cells) and middle column (vascular bundle and pith). However, the middle columns of the three IlMYB86 transgenic lines were shifted outward compared with those of the WT and EV plants.

3.4. Overexpression of IlMYB86 Promoted Lignin Synthesis and Related Gene Expression in Tobacco

Phenotypic data indicate that the ectopic expression of IlMYB86 resulted in thicker stems in transgenic tobacco, and further observation of the cross-section of the stem revealed that the middle column of the transgenic tobacco partially expanded. The tobacco column is composed of vascular bundles and pith, and the main component is lignin. Therefore, the lignin content of the three OE lines was measured, and it was found that the lignin content in the stems of the OE lines was significantly greater than that in the stems of the WT and EV lines (Figure 3B).

Due to the elevated lignin content, it was speculated that IlMYB86 may promote the expression of key enzyme-encoding genes involved in the lignin synthesis pathway in tobacco. RT‒qPCR was used to detect the expression levels of PAL, C4H, 4CL, C3H, HCT, CCoAOMT, CCR and CAD in the EV and three OE lines of tobacco, and it was found that the expression levels of 4CL and HCT were significantly increased in the three OE lines (Figure 3E), thus indicating that IlMYB86 may promote the expression of 4CL and HCT in tobacco.

3.5. Overexpression of IlMYB86 Promotes Chlorophyll Synthesis in Tobacco and Improves the Photosynthetic Ability of Transgenic Plants

To further explore whether the IlMYB86 gene is involved in the synthesis of other substances in tobacco, the chlorophyll content of EV and transgenic tobacco plants was determined. Surprisingly, the chlorophyll content in the three transgenic lines was greater than that in the EV (Figure 4A). These results suggest that IlMYB86 may affect the photosynthesis of tobacco by promoting an increase in chlorophyll content. Therefore, the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration rate of the EV and transgenic lines were measured at the seedling stage, preflowering stage, and full flowering stage, respectively. Compared with those of the EV plants, the intercellular CO2 concentration, net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate of the transgenic plants increased during the three tested periods (Figure 4B–E). The above experimental results showed that the overexpression of IlMYB86 increased the photosynthesis of tobacco.

Figure 4.

Chlorophyll content and various photosynthetic and transpiration rate indices of IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants. (A) The total chlorophyll content of the EV and OE lines. (B–E) The intercellular CO2 content, net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate of the EV and OE lines. S1: the seedling stage; S2: the preflowering stage; S3: the full-flowering stage. Different letters on the bar chart represent significant differences, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The stalk is the main supporting structure of the plant body, and its strength directly affects plant growth and development. Studies of a variety of plants revealed that stem strength was affected by the level of lignin accumulation [29,30,31,32,33]. The biosynthesis of lignin is influenced by key genes involved in its synthetic pathway as well as transcription factors such as those in the MYB family [34]. The flower stem of I. laevigata is long and resistant to lodging. Therefore, it is of great interest to identify MYB transcription factors related to lignin synthesis in I. laevigata and study their biological functions. However, the functional studies of MYB transcription factors involved in lignin biosynthesis in I. laevigata have not been reported.

In this study, we identified and characterized IlMYB86, a typical R2R3-type MYB transcription factor. Sequence analysis revealed its highest homology to the MYB86 protein of I. pallida. The IlMYB86 protein was localized only in the nucleus, indicating its ability to act as a transcription factor. Upon transferring IlMYB86 into tobacco plants, transgenic plants exhibited notable phenotypic changes. The transgenic tobacco plants exhibited increased height, thicker stem diameters, and enhanced stem pressure. Furthermore, the lignin content of IlMYB86 transgenic tobacco plants increased. Concurrently, the expression of 4CL and HCT, pivotal enzymes in lignin biosynthesis, was upregulated. Specifically, 4CL, situated at the terminal end of the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, regulates the metabolic flux of phenylpropanoid derivatives, thereby promoting lignin accumulation [35,36]. Conversely, HCT governs the distribution of mass flux to H, G, and S units in monolignol biosynthesis, thus influencing lignin content. Notably, reduced expression of HCT has been linked to decreased lignin content [37,38]. The coordinated upregulation of these two key genes suggests that IlMYB86 functions as a transcription factor that enhances lignin biosynthesis by activating the expression of the 4CL and HCT genes. This regulatory mode aligns with the mechanisms of other known lignin biosynthesis activators. For instance, EjODO1, a novel R2R3 MYB from Eriobotrya japonica, can trans-activate promoters of lignin biosynthesis genes, such as EjPAL1, Ej4CL1, and Ej4CL5, and transient overexpression triggers lignin biosynthesis [39]. PlMYB43, PlMYB83 or PlMYB103 can directly bind to the promoters of PlCOMT2 and/or PlLAC4 and activate their expression, leading to thickening of the secondary cell wall and increased lignin accumulation when overexpressed in tobacco [40]. In summary, our findings suggest that IlMYB86 acts as a positive regulator of lignin accumulation by promoting the expression of 4CL and HCT in independent transformed lines.

MYB transcription factors play a pivotal role in chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis in plants. For instance, the overexpression of the kiwifruit MYB7 gene in N. benthamiana promoted the accumulation of chlorophyll and increased the expression of the chlorophyll biosynthesis genes NbGGR and NbSGR1 [41]. Similarly, in A. thaliana, AtMYBS1 and AtMYBS2 can bind to and activate both photosynthetic genes and transcription factors involved in chloroplast biogenesis [42]. The transfer of IlMYB86 promoted chlorophyll synthesis in tobacco, suggesting that IlMYB86 may regulate chlorophyll biosynthesis. In addition, the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration rate of the IlMYB86 transgenic plants were measured at the seedling stage, preflowering stage, and full flowering stage, respectively. The results showed that the photosynthetic rate of the IlMYB86 transgenic plants was greater than that of the control plants during the three periods of the experiment. The net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration rate are common indicators reflecting the photosynthetic capacity of plants. Chlorophyll acts as a pigment for light energy harvesting and is transferred to reaction centers during photosynthesis [43]. The chlorophyll content reflects the photosynthetic capacity of plants, and the higher the chlorophyll content is, the greater the photosynthetic capacity. Although this study provides physiological evidence supporting the role of IlMYB86 in enhancing photosynthesis, the precise molecular mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. Future investigations will specifically focus on analyzing the expression levels of key photosynthetic pathway genes and conducting a detailed examination of chloroplast development, including both chloroplast number and ultrastructure, to provide deeper mechanistic insights into this regulatory process.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully identified and functionally characterized IlMYB86, a novel R2R3-MYB transcription factor from I. laevigata. We demonstrated that IlMYB86 localizes to the nucleus and acts as a transcriptional activator. Ectopic expression of IlMYB86 in tobacco not only enhanced stem mechanical strength by promoting lignin accumulation through the upregulation of key biosynthetic genes 4CL and HCT but also significantly improved photosynthetic capacity by increasing chlorophyll content and related physiological parameters. In summary, our study elucidates the regulatory role of IlMYB86 in lignin biosynthesis and provides valuable insights for molecular genetic engineering and breeding programs targeting ornamental plants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121514/s1, Figure S1: Cloning of IlMYB86; Figure S2: Full length CDS sequence and coding protein sequence of IlMYB86; Figure S3: Colony PCR of E. coli transformed with the recombinant vector pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP; Figure S4: Colony PCR of A. tumefaciens transformed with the recombinant vector pCAMBIA1300-IlMYB86-GFP; Figure S5: Positive validation gel plot of IlMYB86 transgenic T0 generation plants; Table S1: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. (Ling Wang); methodology, L.W. (Lei Wang), G.S., Y.Y., D.H. and L.Y.; software, L.W. (Lei Wang) and G.S.; validation, L.W. (Lei Wang), G.S. and L.W. (Ling Wang); formal analysis, L.W. (Lei Wang) and G.S.; investigation, L.W. (Lei Wang), G.S. and L.Y.; resources, L.W. (Ling Wang), L.W. (Lei Wang) and G.S.; data curation, L.W. (Lei Wang), G.S., Y.Y. and D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W. (Lei Wang) and G.S.; writing—review and editing, L.W. (Lei Wang), G.S. and L.W. (Ling Wang); visualization, Y.Y. and D.H.; supervision, L.W. (Ling Wang); project administration, L.W. (Ling Wang); funding acquisition, L.W. (Ling Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation of China, grant number 32573063.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rongpipi, S.; Ye, D.; Gomez, E.D.; Gomez, E.W. Progress and opportunities in the characterization of cellulose-an important regulator of cell wall growth and mechanics. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelker, S.L.; Lachenbruch, B.; Meinzer, F.C.; Strauss, S.H. Reduced wood stiffness and strength, and altered stem form, in young antisense 4CL transgenic poplars with reduced lignin contents. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begović, L.; Abičić, I.; Lalić, A.; Lepeduš, H.; Cesar, V.; Leljak-Levanić, D. Lignin synthesis and accumulation in barley cultivars differing in their resistance to lodging. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhao, M.; Xu, Q.; Li, F. Genetic enhancement of lodging resistance in rice due to the key cell wall polymer lignin, which affects stem characteristics. Breeding Sci. 2018, 68, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Luan, Y.; Xia, X.; Shi, W.; Tang, Y.; Tao, J. Lignin provides mechanical support to herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) stems. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Schuetz, M.; Roach, M.; Mansfield, S.D.; Ellis, B.; Samuels, L. Neighboring parenchyma cells contribute to Arabidopsis xylem lignification, while lignification of interfascicular fibers is cell autonomous. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3988–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholme, R.; Morreel, K.; Darrah, C.; Oyarce, P.; Grabber, J.H.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Metabolic engineering of novel lignin in biomass crops. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 978–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, A.K.; Davison, B.H.; Standaert, R.F.; Davis, M.F.; Smith, J.C.; Parks, J.M. Chemical factors that control lignin polymerization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Kamimura, N.; Sakamoto, S.; Nagano, S.; Takata, N.; Liu, S.; Goeminne, G.; Vanholme, R.; Uesugi, M.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Rerouting of the lignin biosynthetic pathway by inhibition of cytosolic shikimate recycling in transgenic hybrid aspen. Plant J. 2022, 110, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, T.; Feng, K.; Xie, M.; Barros, J.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Muchero, W.; Chen, J.-G. Phylogenetic occurrence of the phenylpropanoid pathway and lignin biosynthesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 704697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Amo, A.; Ahmed, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Phenylpropanoid pathway engineering: An emerging approach towards plant defense. Pathogens 2020, 9, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholme, R.; De Meester, B.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and its integration into metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q. Lignification: Flexibility, biosynthesis and regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.; Li, F.; Hou, Y. GhODO1, an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, positively regulates cotton resistance to Verticillium dahliae via the lignin biosynthesis and jasmonic acid signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 201, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratyusha, D.S.; Sarada, D.V.L. MYB transcription factors—Master regulators of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and diverse developmental and stress responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 2245–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, R.L.; Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.-H. MYB83 is a direct target of SND1 and Acts Redundantly with MYB46 in the regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 1950–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Richardson, E.A.; Ye, Z.-H. The MYB46 transcription factor is a direct target of SND1 and regulates secondary wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2776–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lee, C.; Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.-H. MYB58 and MYB63 are transcriptional activators of the lignin biosynthetic pathway during secondary cell wall formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y.; Fu, C.; Han, X.; He, H.; Zhao, Q. MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.; Kumar, S.; Khan, B.M. Over-expression of a subgroup 4 R2R3 type MYB transcription factor gene from Leucaena leucocephala reduces lignin content in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Song, A.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J.; Chen, F. CmMYB8 Encodes an R2R3 MYB transcription factor which represses lignin and flavonoid synthesis in chrysanthemum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lu, W.; Ran, L.; Dou, L.; Yao, S.; Hu, J.; Fan, D.; Li, C.; Luo, K. R2R3-MYB transcription factor MYB 6 promotes anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis but inhibits secondary cell wall formation in Populus tomentosa. Plant J. 2019, 99, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Hu, H. Transcriptome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of R2R3-MYB gene family during lignin biosynthesis in Chinese cedar (Cryptomeria fortunei Hooibrenk). Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 182, 114883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for the rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.A. Subcellular Localization of Transiently Expressed Fluorescent Fusion Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1069, 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, S.; Guan, C.; Kong, X.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Overexpressing the NAC transcription factor LpNAC13 from Lilium pumilum in tobacco negatively regulates the drought response and positively regulates the salt response. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.H. Secondary cell walls: Biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 95–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.; Thomas, S. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manga-Robles, A.; Santiago, R.; Malvar, R.A.; Moreno-González, V.; Fornalé, S.; López, I.; Centeno, M.L.; Acebes, J.L.; Álvarez, J.M.; Caparros-Ruiz, D.; et al. Elucidating compositional factors of maize cell walls contributing to stalk strength and lodging resistance. Plant Sci. 2021, 307, 110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Kong, F.; Liu, Q.; Lan, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ou, Q.; Chen, L.; Kessel, G.; Kempenaar, C.; et al. Maize basal internode development significantly affects stalk lodging resistance. Field Crop Res. 2022, 286, 108611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, L.; Shen, J.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Cheng, L.; Gui, J. The MPK6-LTF1L1 module regulates lignin biosynthesis in rice through a distinct mechanism from Populus LTF1. Plant Sci. 2023, 337, 111890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Lin, Z.; Shen, J.; Luo, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, L.; Gui, J. OsTCP19 coordinates inhibition of lignin biosynthesis and promotion of cellulose biosynthesis to modify lodging resistance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhu, Q. Auxin response factors fine-tune lignin biosynthesis in response to mechanical bending in bamboo. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, N.; Gao, C.; Qi, L.; Wang, C. The BpMYB4 transcription factor from Betula platyphylla contributes toward abiotic stress resistance and secondary cell wall biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 606062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, Z. Systematic analysis and expression profiles of the 4-Coumarate: CoA Ligase (4CL) gene family in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y. Two monolignoid biosynthetic genes 4-Coumarate:Coenzyme A Ligase (4CL) and p-Coumaric Acid 3-Hdroxylase (C3H) involved in lignin accumulation in pear fruits. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, N.; Qi, Q.; Li, S.; Ruan, B.; Jiang, X.; Gai, Y. Characterization and functional analysis of the Hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: Shikimate Hydroxycinnamoyl Transferase (HCT) gene family in poplar. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Ren, S.; Lu, M.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, R.; Lv, J. Preliminary study of cell wall structure and its mechanical properties of C3H and HCT RNAi transgenic poplar sapling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ge, H.; Zang, C.; Li, X.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.; Yin, X. EjODO1, a MYB transcription factor, regulating lignin biosynthesis in developing loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Lu, L.; Sheng, Z.; Zhao, D.; Tao, J. An R2R3-MYB network modulates stem strength by regulating lignin biosynthesis and secondary cell wall thickening in herbaceous peony. Plant J. 2023, 113, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampomah-Dwamena, C.; Thrimawithana, A.H.; Dejnoprat, S.; Lewis, D.; Espley, R.V.; Allan, A.C. A kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) R2R3-MYB transcription factor modulates chlorophyll and carotenoid accumulation. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangedakis, E.; Yelina, N.E.; Billakurthi, K.; Hua, L.; Schreier, T.; Dickinson, P.J.; Tomaselli, M.; Haseloff, J.; Hibberd, J.M. MYB-related transcription factors control chloroplast biogenesis. Cell 2024, 187, 4859–4876.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, T.; Fujita, Y. Regulation and evolution of chlorophyll metabolism. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).