Abstract

Leaf color mutants are valuable resources for studying photosynthesis, pigment metabolism, and gene regulatory networks in plants. In this study, a naturally occurring sweetpotato albino mutant exhibiting a stable white-leaf phenotype across developmental stages was identified and compared with its green-leaf wild type to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying albinism. The mutant showed a dramatic 98.8% reduction in total chlorophyll content and a markedly decreased Fv/Fm value (0.59), indicating severe impairment of PSII efficiency. Integrated transcriptomic analysis identified 3520 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), while metabolomic profiling revealed 270 differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs). Genes involved in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis, chloroplast development, and photosynthetic electron transport were strongly repressed, including key regulators such as GLK1, PORA, and PORB. Metabolomic alterations were mainly enriched in flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, and amino acid-derived pathways, reflecting broad reprogramming of both primary and secondary metabolism. These changes were accompanied by severely disrupted chloroplast ultrastructure, suggesting a primary defect in plastid development. Collectively, the integrated multi-omics evidence provides a comprehensive understanding of the coordinated transcriptional and metabolic alterations driving the albino phenotype in sweetpotato and establishes this mutant as a potential model for studying the interplay between chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthesis, and secondary metabolism.

1. Introduction

In photosynthetic eukaryotes, chloroplasts play a central role in carbon fixation and energy transformations [1,2]. Leaf color mutants are valuable genetic resources for dissecting chloroplast development, photosynthetic physiology, pigment metabolism, and related regulatory networks. Although leaf color mutants have been extensively characterized in diploid model species (e.g., Oryza sativa [3], Arabidopsis thaliana [4]) and allotetraploid/allohexaploid crops (e.g., Brassica napus [5]). In contrast, leaf color mutagenesis remains virtually unexplored in autopolyploid species, particularly in autohexaploid crops. Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas, 2n = 6× = 90), a highly heterozygous autohexaploid lacking high quality reference genome, poses unique challenges due to high sequence redundancy and potential dosage effects on pigment- and chloroplast-related genes. Consequently, the genetic and molecular basis of leaf color mutations in sweetpotato remains largely unknown, highlighting a critical knowledge gap that our study aims to address. Extensive research has been carried out on pigment content metabolism [6], chloroplast development [7], photosynthetic physiology [8], genetic patterns [9], and gene cloning [10]. These studies provide crucial foundations for understanding the mechanisms underlying leaf color variation and related gene functions.

The direct causes of leaf color mutations are often associated with alterations in pigment content and proportion, chloroplast ultrastructure, and physiological or biochemical metabolism. Among these, chlorophyll metabolism plays a central role, as changes in its biosynthesis or degradation are closely related to color variation in both mutants and senescent leaves [11,12]. For instance, studies on Camellia sinensis have shown that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis, as well as chloroplast development, affect leaf coloration [13,14]. In Triticum aestivum, mutations in magnesium chelatase subunit H (CHLH) and β-carotene hydroxylase (BCH) have been identified as key determinants of yellow-green leaf phenotypes [15]. Similarly, in Cymbidium sinense, higher expression of chlorophyll degradation genes has been correlated with reduced chlorophyll levels and pale leaves [16]. Furthermore, altered expression of genes associated with flavonoid and carotenoid biosynthesis has been linked to yellow or variegated phenotypes in Lagerstroemia indica and Ginkgo biloba [17,18]. These findings highlight that leaf color formation is a complex process influenced by pigment biosynthesis and degradation, chloroplast development, and secondary metabolic pathways. Taken together, chloroplast development provides the structural basis for pigment accumulation, while defects in chloroplast biogenesis trigger retrograde signals that repress photosynthetic pigment synthesis and simultaneously activate secondary metabolic pathways, leading to diverse leaf color phenotypes.

Sweetpotato is a hexaploidy crop of global importance, is valued for its high nutritional content, wide adaptability, and multiple uses as food, feed, and industrial raw material. Beyond its agricultural significance, sweetpotato also serves as an ornamental plant, with silver- or gold-colored leaf variants contributing to its landscape and economic value. Leaf color mutants, particularly severe albino, yellow, or white-striped variants, despite being lethal or sub-lethal under field conditions and thus unfeasible for direct production, represent invaluable physiological and genetic tools. They enable precise dissection of chlorophyll biosynthesis, chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthetic efficiency, retrograde signaling, and dosage-dependent regulation of homoeologous genes in an autohexaploid background—processes that are difficult to study in green-leaf material due to functional redundancy. However, despite the importance of leaf color variation in sweetpotato, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying leaf-color variation in this species. In this study, we identified a naturally occurring sweetpotato leaf albino mutant characterized by a stable white-leaf phenotype throughout development. To uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying this distinct phenotype, we conducted integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses comparing the albino mutant with wild-type leaves. By combining pigment content determination, gene expression profiling, and metabolic pathway analysis, we aimed to identify key genes and metabolites associated with chlorophyll biosynthesis, chloroplast development, and secondary metabolism. This work provides novel insights into the regulatory mechanisms of leaf color variation in sweetpotato and contributes valuable resources for functional genomics and crop improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The plant materials used in this study were the ornamental sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) variety ‘Tricolor’ wild-type (WT) and albino mutant line. The albino mutant originated from the wild-type (WT) and differs primarily in leaf coloration (Figure 1). The albino phenotype was visually stable across multiple vegetative generations, presenting in leaves, stems, young shoots, and roots, showing no sectorial or tissue-specific variation. Both WT and mutant were maintained at the Xuzhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Xuzhou, China. The plants were cultivated in a greenhouse under controlled conditions: daytime temperature of 25 °C, nighttime temperature of 15 °C, relative humidity of 60–70%, and natural light exposure. All leaf samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Three biological replicates were prepared for each genotype.

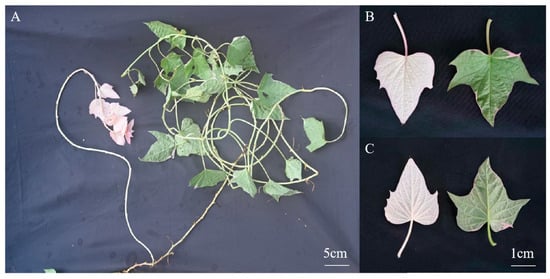

Figure 1.

Phenotypic comparison of the wild-type and a mutant plant exhibiting albinism. (A) An albino seedling, which originated from a somatic mutation on a single plant. (B,C) The adaxial (upper) and abaxial (lower) leaf surfaces of the mutant and wild-type plants, respectively. Scale bars: 5 cm (in (A)) and 1 cm (in (B,C)).

2.2. Measurement of SPAD, Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents

SPAD values were measured from 10 leaves using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta Corp., Solna, Sweden), with the average of three separate readings per leaf recorded. For pigment analysis, 0.2 g of fresh leaf tissue was extracted in 10 mL of 80% acetone at 4 °C for 24 h. The absorbance of the extracts was then measured spectrophotometrically at 663 nm, 645 nm, and 470 nm. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoid concentrations were calculated using standard equations. Both green (WT) and white (mutant) leaves were selected for chlorophyll and carotenoid analysis. The concentrations of these pigments were determined using the Holm equation and a previously described method [19]. Pigment contents were compared using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (n = 3). Given the near-absent chlorophyll in the albino mutant leaves, we confirmed that pigment levels were consistently below the reliable quantification threshold of the spectrophotometric method (approximately 0.05 mg/g FW for total chlorophyll and 0.02 mg/g FW for carotenoids when using 0.2 g tissue in 10 mL 80% acetone).

2.3. Microscopic and Ultrastructural Observation

Paraffin Sectioning: Leaf segments (2 mm × 5 mm) were fixed in FAA solution (formalin: acetic acid:70% ethanol, 1:1:18, v/v/v) for 24 h. Samples were dehydrated with a graded ethanol series, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (8 μm thick) were prepared using a rotary microtome (Slee, Nieder-Olm, Germany), stained with safranin and fast green, and sealed with neutral balsam. Images were captured using an fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX53, Olympus, Shinjuku, Japan).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Fresh leaf tissues (1 mm3) were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 12 h, rinsed with phosphate buffer, and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydration in graded ethanol, samples were embedded in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, then observed under a transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi HT7700, Hitachi Ltd., Chiyoda-ku, Japan). Chloroplast and subcellular structures were analyzed following the previous method [20].

2.4. Fast Chlorophyll Fluorescence (OJIP) Measurement

Dark-adapted leaves (30 min) were analyzed using a Handy PEA (Hansatech Instruments Ltd., King’s Lynn, UK). The OJIP transient (0–1 s) was recorded under a red-light pulse (3000 μmol photons m−2 s−1), measuring parameters such as Fo, Fj, Fi, and Fm. Derived indices, including Fv/Fm, Vj, and Vi, Performance Index (PI_ABS), absorbed light energy per reaction center (ABS/RC), dissipated energy per reaction center (DI0/RC) were automatically calculated by the instrument software PEA Plus (version 1.12, Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, UK) following the standard JIP-test equations. Measurements were conducted with three biological replicates, each including multiple leaves.

2.5. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

UHPLC-MS/MS analyses were performed using a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher, Bremen, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap Q ExactiveTMHF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) in (LCSW, Hangzhou, China). Samples were injected into a Hypesil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) using a 12 min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The eluents for the positive polarity mode were eluent A (0.1% FA in Water) and eluent B (Methanol). The eluents for the negative polarity mode were eluent A (5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0) and eluent B (Methanol). The solvent gradient was set as follows: 95% B, 0–0.5 min; 95–65% B, 0.5–7 min; 65–40% B, 7–8 min; 40% B, 8–9 min; 40–95% B, 9–9.1 min; 95% B, 9.1–12 min. The Q Exactive TM HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) was operated in positive/negative polarity mode with a spray voltage of 3.5 kV, capillary temperature of 320 °C, sheath gas flow rate of 35 psi, and aux gas flow rate of 10 L/min, S-lens RF level of 60, Aux gas heater temperature of 350 °C.

The raw data files obtained from UPLC-MS/MS were processed using Compound Discoverer 3.1 (CD3.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). CD3.1 was employed for tasks such as peak alignment, peak picking, and quantitation for each metabolite. To predict the molecular formula of the metabolites, peak intensities were normalized to the total spectral intensity and analyzed for additive ions, molecular ion peaks, and fragment ions. The peaks obtained were then compared with the mzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org/, accessed on 18 July 2024), mzVault, and MassList databases to ensure accurate qualitative and relative quantitative results. Statistical analyses were performed using R (v3.4.3), Python (v2.7.6) and CentOS (v6.6). In cases where the data did not follow a normal distribution, the area transformations method was applied as an attempt for normalization.

The metabolites were annotated using three databases: the KEGG pathway Database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html, accessed on 20 July 2024), the Human Metabolome Database (https://hmdb.ca/metabolites, accessed on 20 July 2024), and the LIPID MAPS Database (http://www.lipidmaps.org/, accessed on 20 July 2024). HMDB was used primarily for annotating primary metabolites and lipids, although it may have limitations for exclusively plant-specific metabolites. Principal component analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed using SIMCA software (v14.1). Statistical significance (p-value) was calculated using univariate analysis (t-test). Metabolites with a VIP (Variable Importance in Projection) score greater than 1, a p-value less than 0.05, and an absolute fold change of at least 2 were considered differential metabolites. Volcano plots based on the log2(FoldChange) and −log10(p-value) of metabolites were generated using ggplot2 in R to filter metabolites of interest. To evaluate the robustness of the OPLS-DA model and exclude overfitting given the high Q2 values, a 200-time permutation test was performed in SIMCA. The permuted R2 and Q2 intercepts were substantially lower than those of the original model, confirming its reliability.

2.6. RNA Extraction, Library Construction and Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and integrity of the extracted RNA were assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and checked using Rnase free agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration of the RNA was determined using NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Following the extraction of total RNA, mRNA was enriched using Oligo(dT) beads using the Ribo-Zero™ Magnetic Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA). The enriched mRNA was then fragmented into shorter fragments using a fragmentation buffer and reverse transcribed into cDNA using random primers. Subsequently, second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using DNA polymerase I, Rnase H, dNTPs, and buffer. The resulting cDNA fragments were purified using the QiaQuick PCR extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands), followed by end repair, addition of poly(A) tails, and ligation to Illumina sequencing adapters. The ligation products were size-selected using agarose gel electrophoresis, PCR amplified and ultimately sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China).

2.7. RNA-Seq Analysis

The raw reads underwent initial quality control using FastQC, a quality control tools for high throughput sequence data (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, accessed on 29 July 2024). The reads contained original reads with adapters or low-quality bases, which were further filtered using fastp (version 0.18.0) [21] to obtain high-quality clean reads. All subsequent analyses were based on the high-quality clean data. The clean reads were independently mapped to Taizhong 6 genome sequence [22] using the HISAT2 (v2.2.4) [23] with default settings. The number of reads uniquely mapped to each annotated gene were determined by FeatureCount v1.6.4 [24], and the number of read were converted to FPKM (fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) for gene expression quantification. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were performed using the DESeq2 R package (1.16.1) [25]. Genes with an FDR < 0.01 and |log2-fold change| > 2 was considered differentially expressed genes. GO and KEGG pathways enrichment analysis were performed using clusterProfiler v4.10.1 [26].

2.8. Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

To confirm the transcriptional patterns of the selected genes, three independent biological replicates were collected for each sample to ensure reproducibility. Total RNA was isolated using the Plant RNA Easy Fast Extraction Kit (TIANGEN, Biotech, Beijing, China, Cat. No. DP452), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized with the TranScript Uni One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was subsequently carried out using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara Bio, Shig, Japan) on a real-time detection system. Primer sequences were designed via Primer Premier 5.0 software and are provided in Table S1. The amplification protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s, with a final dissociation step at 95 °C for 15 s. IbActin was employed as the internal control for normalization. All reactions were performed in triplicate to minimize technical variation, and the relative expression levels of the candidate genes were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phenotypic, Physiological, and Structural Characterization of the Albino Leaf Mutant in Sweetpotato

A spontaneous albino leaf mutant was identified in sweetpotato, exhibiting pronounced phenotypic differences compared with the WT plants. As shown in Figure 1, the mutant displayed pale-white leaves and stems, in stark contrast to the green leaves and stems of WT plants, indicative of normal pigmentation. Detailed examination of leaf surfaces revealed that both the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of WT leaves were uniformly green, whereas the albino mutant leaves were entirely white, suggesting a severe deficiency in pigment accumulation.

To elucidate the physiological basis of this phenotype, chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were quantified in WT and mutant leaves (Table 1). In WT leaves, the SPAD value, a proxy for chlorophyll content, was 41.0 ± 1.62, with total chlorophyll (a + b) content measured at 107.6 ± 1.3 mg/100 g fresh weight (FW) and carotenoid content at 15.8 ± 0.1 mg/100 g FW. In contrast, the albino mutant exhibited a complete absence of SPAD signal (0), with chlorophyll (a + b) content significantly reduced to 1.3 ± 0.9 mg/100 g FW and carotenoid content decreased to 0.9 ± 0.05 mg/100 g FW, representing over a 15-fold reduction relative to WT. These results confirm that the albino mutant is severely impaired in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis, consistent with the observed loss of leaf pigmentation.

Table 1.

Pigment contents in leaves of sweet potato cultivars WT and mutant.

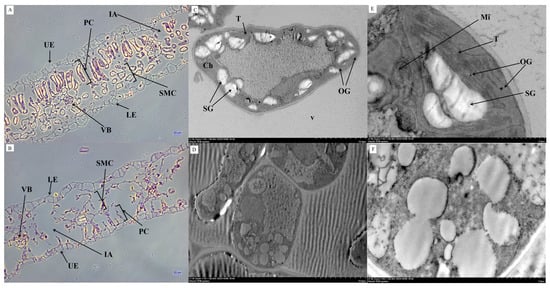

Microscopic observation revealed that WT leaves exhibited a typical dorsiventral structure, with densely packed palisade cells rich in chloroplasts and spongy mesophyll cells containing fewer but still visible chloroplasts. In contrast, the albino mutant maintained an intact tissue organization but lacked green pigmentation, and chloroplasts were barely visible within the mesophyll cells (Figure 2A,B). Transmission electron microscopy further showed that WT chloroplasts had intact double membranes, well-developed thylakoid stacks, and abundant plastoglobuli (Figure 2C,E). By contrast, mutant chloroplasts exhibited severe ultrastructural defects, including reduced stroma density, disorganized and vesiculated thylakoids, loss of grana–stroma continuity, and markedly fewer plastoglobuli (Figure 2D,F). These profound abnormalities strongly suggest that defective chloroplast biogenesis is a primary developmental defect rather than a secondary consequence of pigment loss, as the structural defects are consistent with early disruptions in plastid differentiation rather than degradation of previously functional chloroplasts. Thus, the ultrastructural evidence supports the conclusion that impaired chloroplast development underlies the pigment deficiency rather than resulting from it.

Figure 2.

Ultrastructural observation of wild-type and albino leaf mutant. (A,C,E) ultrastructure of CK. In (A), bar: 20 μm; (C), bar: 10 μm; (E), bar: 2 μm. (B,D,F) ultrastructure of T. In (B), bar: 20 μm; (D), bar: 10 μm; (F), bar: 2 μm. UE: upper epidermis; LE: lower epidermis; PC: palisade cells; SMC: spongy mesophyll cells; IA: intercellular air-space; VB: vascular bundle; Ch: chloroplast; T: thylakoid; SG: starch granule; Mi: mitochondrion; V: vacuole; OG: osmium granule.

To assess photosynthetic performance, we conducted Fast Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Induction (OJIP) analysis, with key parameters summarized in Table 2. The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII), represented by Fv/Fm, was significantly reduced in the mutant to 0.59 ± 0.01 compared to 0.84 ± 0.01 in WT, Fv/Fm decreased by 29.8% relative to WT. Additionally, the Fv/Fo and Fm/Fo ratios in the mutant were reduced to 1.44 and 2.44, respectively, suggesting a marked decline in the density and activity of PSII reaction centers. Significant increases in Vj and Vi parameters in the mutant indicate impaired electron transport from QA− to QB and a restricted plastoquinone (PQ) pool capacity. The notably low Fo value further corroborates a severe reduction in functional PSII reaction centers in the mutant. These OJIP signatures collectively reflect a severe impairment of PSII structure and photochemical activity, a physiological condition typically associated with broad suppression of photosystem assembly and light-harvesting processes. Such physiological characteristics provide an important functional context for understanding the molecular changes presented in subsequent sections of this study.

Table 2.

Parameters of fast chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics (RFU).

3.2. Identification of Differentially Accumulated Metabolites (DAMs)

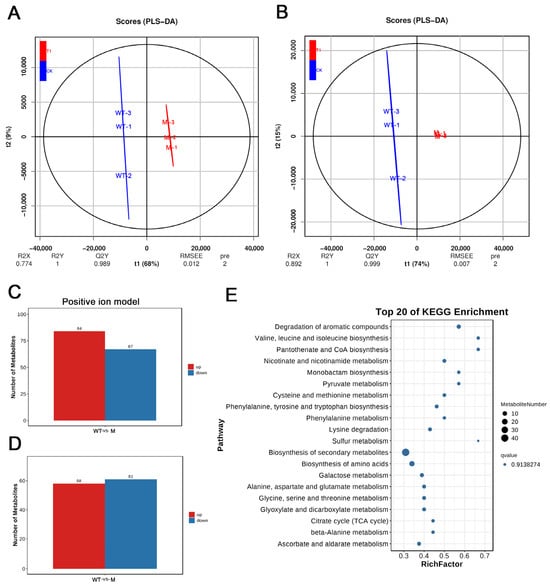

To conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the metabolic differences between the two leaves, we utilized liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to profile the metabolites of WT and mutant. The quality of the nontargeted metabolome data was deemed high, as indicated by the strong correlation observed among quality control (QC) samples and the results of principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure S1). In the positive ion mode (POS), the PCA score plots showed PC1 = 43.5% and PC2 = 14.3%. Similarly, in the negative ion mode (NEG), the PCA score plots showed PC1 = 47% and PC2 = 15.9%. PLS-DA is a multivariate statistical analysis method that utilizes supervised pattern recognition. Its extension, OPLS-DA, is a widely used statistical approach in metabolomics data analysis. OPLS-DA provides enhanced group separation, enabling a better understanding of the variables contributing to classification. In Figure 2A,B, the score plots of OPLS-DA based on WT-mutant are presented. In the positive ion mode (POS), the R2X, R2Y, and Q2Y values were 0.774, 1, and 0.989, respectively. In the negative ion mode (NEG), the corresponding values were 0.892, 1, and 0.999. The clear distinction between the WT and mutant components demonstrated significant differences in metabolite accumulation among the two genotypes.

After applying quality control procedures, a total of 1089 (569 in POS and 520 in NEG) metabolites were identified (Table S2). Among these, 270 differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) (151 POS and 119 NEG) were identified as significant based on criteria of |log2fold change| ≥ 1 and VIP ≥ 1 when comparing WT and mutant (Figure 3A,B, Table S3). Specifically, 84 metabolites were upregulated in the POS mode, while 67 were downregulated. In the negative (NEG) mode, 58 metabolites exhibited upregulation, while 61 metabolites showed downregulation. Notably, the metabolites that predominantly accumulated in the mutant included phenylalanine, Phenylacetaldehyde, Dl-ethionine, and others. Phenylalanine and phenylacetaldehyde are major intermediates in the phenylpropanoid pathway, and their elevated levels may reflect enhanced flux toward stress-responsive secondary metabolism due to impaired chloroplast function. Dl-ethionine, a toxic methionine analogue, is often associated with metabolic imbalance or stress, suggesting that amino acid metabolism may also be disrupted in the mutant. Conversely, Ginsenoside f3, Reserpine, Pheophorbide a, and several others were found to be accumulated in WT. Among these, pheophorbide a is a well-known chlorophyll-degradation intermediate, and its lower abundance in the mutant supports the conclusion that chlorophyll deficiency results primarily from impaired biosynthesis rather than accelerated degradation. To gain further insight into the differential metabolite pathways, we conducted Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis on all DAMs. Consequently, KEGG pathways related to ‘Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites’ and ‘Carbon metabolism’ were found to be significantly enriched among the DAMs (Figure 3C). These findings highlight substantial differences in metabolite accumulation between WT and mutant, which could contribute to the divergent levels of chlorophyll observed.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive metabolomic overview of wild-type vs. albino leaf mutant: PLS-DA, differential metabolite counts, and KEGG pathway enrichment. (A) Positive-ion PLS-DA score plot showing clear separation between wild-type and mutant albino leaf mutant. (B) Negative-ion PLS-DA score plot showing clear separation between wild-type and mutant albino leaf mutant. (C) Number of significantly altered metabolites detected in the positive-ion mode. (D) Number of significantly altered metabolites detected in the Negative-ion mode. (E) Top 20 enriched KEGG pathways of differential metabolites ranked by enrichment factor (bubble size) and −log10(p-value) (color intensity).

3.3. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) and Functional Analysis

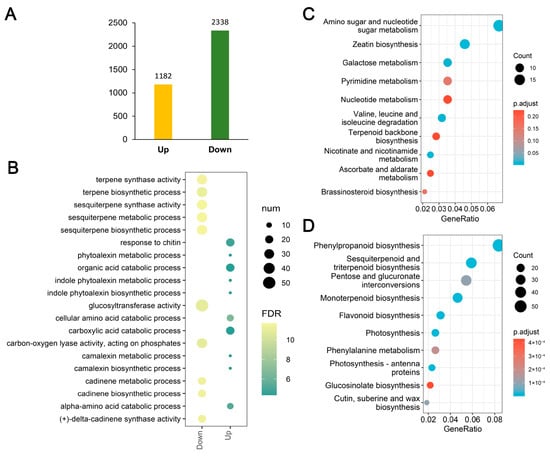

To further investigate the molecular basis underlying the albino phenotype, we performed RNA-sequencing analysis of WT and mutant leaves (Table S4). The transcriptome sequencing approach and analysis were described previously [27]. The high correlation observed among the biological replicates in WT and mutant types, as indicated by Pearson’s coefficient, instilled confidence in the reliability of the transcriptome data. (Figure S2). In total, 3520 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, including 1182 upregulated and 2338 downregulated genes (Figure 4A). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis indicated distinct functional tendencies between upregulated and downregulated genes. The upregulated DEGs were mainly enriched in processes such as organic acid catabolic process, camalexin metabolism, and glucosyltransferase activity, suggesting an activation of stress- and defense-related metabolic pathways. In contrast, the downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in terpene synthase activity, sesquiterpene biosynthetic process, and indole phytoalexin biosynthetic process, reflecting a broad suppression of secondary metabolite biosynthesis (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Transcriptomic analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (A) The number of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs. (B) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs. (C,D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs, respectively.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis further indicated that DEGs were significantly enriched in metabolic and biosynthetic pathways. Upregulated genes were mainly associated with amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, zeatin biosynthesis, and pyrimidine metabolism (Figure 4C). Conversely, downregulated genes were highly enriched in pathways critical for photosynthesis and pigment metabolism, including photosynthesis, photosynthesis–antenna proteins, flavonoid biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and glucosinolate biosynthesis (Figure 4D). Notably, the strong enrichment of photosynthesis-related pathways among the downregulated DEGs is consistent with the severe loss of chlorophyll and the defective chloroplast structures observed in the mutant.

3.4. Expression Analysis of Pigment Biosynthesis-Related Candidate Genes

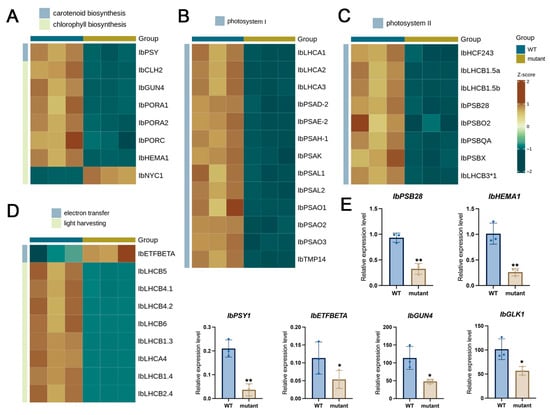

To elucidate the molecular basis underlying leaf albinism in the sweetpotato mutant, we analyzed the transcriptomic expression profiles of key genes involved in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis and degradation (Figure 5A). Compared with the WT, the majority of biosynthetic genes exhibited markedly reduced expression in the mutant, whereas several degradation-associated genes showed opposite or less pronounced changes, suggesting that a disrupted metabolic balance may contribute to the severe depletion of photosynthetic pigments.

Figure 5.

Expression analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to photosynthesis and pigment biosynthesis pathways in WT and mutant plants. (A) DEGs associated with carotenoid and chlorophyll biosynthesis. (B) DEGs encoding components of photosystem I. (C) DEGs encoding components of photosystem II. (D) DEGs involved in electron transfer and light harvesting including specific genes highlighted in a WT vs. mutant comparison. (E) qRT-PCR validation of six selected genes. Rows represent individual genes, and columns represent biological groups (WT and mutant). The color scale indicates Z-score normalized expression levels, with red representing up-regulation and blue representing down-regulation. * and ** indicate significant differences compared with WT at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively (Student’s t-test).

In the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway, several genes encoding rate-limiting or essential enzymes were strongly repressed. These included IbHEMA1 (glutamyl-tRNA reductase, IB15G03340), which catalyzes the first committed step in chlorophyll synthesis; IbGUN4 (IB11G11220), a key regulator of magnesium chelatase activity that facilitates Mg2+ insertion into protoporphyrin IX; and multiple isoforms of IbPORA/PORB (e.g., IB01G02810, IB13G17970, IB13G17960), which mediate protochlorophyllide reduction. Among these, IbPORA1 (IB01G02810) showed the most dramatic reduction in expression. Interestingly, the chlorophyll degradation–related genes IbCLH2 (IB14G27650) and IbNYC1 (IB07G06640) were also downregulated, implying that both chlorophyll synthesis and degradation were suppressed. This concurrent repression of degradative and biosynthetic components indicates not a selective block in a single pathway, but rather a global failure of plastid development, consistent with arrested chloroplast biogenesis rather than accelerated pigment breakdown. However, the more substantial repression of biosynthetic genes likely represents the primary cause of chlorophyll deficiency in the mutant.

Similarly, genes in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway were significantly downregulated. Notably, IbPSY1 (IB05G02210), encoding phytoene synthase—the enzyme catalyzing the first committed step of carotenoid formation—was strongly suppressed, which would impede the overall carotenoid accumulation. In addition, the transcription factor IbGLK1, a key regulator of chloroplast development and pigment biosynthetic gene expression, was significantly reduced in the mutant, potentially reinforcing the global repression of pigment metabolism. This reduction in IbGLK1, together with decreased expression of several chloroplast-associated transcriptional regulators, suggests that upstream regulatory impairment may contribute to the coordinated repression of pigment biosynthetic pathways.

3.5. Expression Trend Analysis of Photosynthesis-Related DEGs

To further explore how albinism affects photosynthetic capacity, we examined differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with the photosynthesis pathway (Figure 5B–D). A total of 30 genes were consistently downregulated, encompassing components of photosystem II (e.g., IbLHCB1.5a/b, IbPSB28, IbPSBO2, IbPSBQA, IbPSBX), photosystem I (e.g., IbLHCA1/2/3, IbPSAD2, IbPSAH1, IbPSAK, IbPSAL1/2, IbPSAO1/2/3), electron transfer chains (IbETFBETA), and light-harvesting complexes (IbLHCB4/5/6, IbLHCB1.3/1.4/2.4, IbLHCA4). The widespread repression of these photosynthetic genes indicates a systemic impairment of the photosynthetic machinery, which corresponds well with the physiological data showing a reduction in Fv/Fm (0.59) and a sharp decline in reaction center density in the mutant. Such coordinated suppression of photosystem-related genes is consistent with patterns reported in albino mutants of Hydrangea macrophylla and Cymbidium longibracteatum [28,29], where defects in chloroplast biogenesis similarly led to the global downregulation of photosystem I/II and light-harvesting complex genes.

To validate the transcriptome results, qRT-PCR analysis was performed for representative genes, including IbPSY1, IbPSB28, IbHEMA1, IbETFBETA, IbGUN4, and IbGLK1. Consistent with the RNA-seq data, all selected genes exhibited significantly lower expression levels in the mutant compared with the WT (Figure 5E), confirming the reliability of the transcriptomic analysis.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Chlorophyll and carotenoids are the primary pigments found in green leaves. Studies have shown that leaf color mutants often exhibit reduced levels of these pigments [30,31]. In this study, the identification and characterization of a spontaneous albino leaf mutant in sweetpotato provide valuable insights into the molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying chlorophyll deficiency and chloroplast development. Our results demonstrated that the albino phenotype was primarily driven by severe impairments in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis, defective chloroplast ultrastructure, and significant alterations in metabolic and transcriptional profiles. These findings align with previous studies on albino mutants in other plant species, such as rice and wheat, where disruptions in pigment biosynthesis and chloroplast development are central to the albino phenotype [15,32].

The albino mutant exhibited a complete loss of green pigmentation, with SPAD values dropping to zero and chlorophyll and carotenoid contents reduced by more than 15-fold relative to the wild type. This drastic reduction in photosynthetic pigments was consistent with observations in other albino mutants, where impaired chlorophyll biosynthesis resulted in a substantial loss of photosynthetic capacity [3,4]. The absence of chlorophyll and carotenoids not only eliminated the green coloration but also severely compromised photosynthetic efficiency, as evidenced by the reduced Fv/Fm ratio (0.59 vs. 0.81 in WT) and a >95% collapse of the Performance Index (PI_ABS) [5]. These severe OJIP impairments are directly attributable to the near-complete transcriptional repression of the entire photosynthetic apparatus, illustrating perfect coherence between physiological damage and gene expression.

Microscopic and ultrastructural analyses further revealed that the albino mutant retained normal leaf tissue organization but exhibited severe chloroplast defects, including disorganized thylakoids, reduced stroma density, and fewer plastoglobuli. These findings were consistent with reports on albino mutants in maize and pecan, where defective chloroplast development disrupts thylakoid membrane formation and pigment accumulation [33,34]. The observed ultrastructural abnormalities likely resulted from disrupted expression of genes involved in chloroplast biogenesis, such as GLK1, which was critical for chloroplast development and was significantly downregulated in the mutant [35].

Metabolomic analysis revealed significant differences in metabolite accumulation between the wild-type and albino mutant leaves, with 270 differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) identified. The enrichment of pathways related to “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” and “Carbon metabolism” suggested a metabolic reprogramming in the mutant, likely as a compensatory response to the loss of photosynthetic capacity. Upregulated metabolites, such as phenylalanine and phenylacetaldehyde, indicate an activation of stress-related pathways, which is consistent with the upregulation of stress- and defense-related genes observed in the transcriptomic analysis [36,37]. Conversely, the downregulation of metabolites like ginsenoside f3 and pheophorbide a, which are associated with chlorophyll metabolism, further supports the disruption of pigment biosynthesis pathways in the mutant [38]. These metabolic shifts closely resemble reprogramming patterns reported in various crops under abiotic stress. For example, drought or salinity often triggers enhanced accumulation of osmoprotectants and antioxidants to mitigate oxidative damage caused by impaired photosynthesis. A similar adaptive strategy has been documented in argan trees subjected to salinity stress, where increased levels of soluble carbohydrates, proline, and enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes (catalase and peroxidase) help alleviate oxidative stress [39].

The KEGG enrichment analysis of DAMs highlights the impact of albinism on secondary metabolite biosynthesis, a common feature in chlorophyll-deficient mutant [40]. For instance, the downregulation of flavonoid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways, as observed in the transcriptomic data, may contribute to the reduced accumulation of protective secondary metabolites, rendering the mutant more susceptible to environmental stresses [41]. These metabolic shifts underscore the interconnectedness of pigment biosynthesis, chloroplast function, and secondary metabolism, as previously reported in Arabidopsis albino mutants [42].

The transcriptomic analysis identified 3520 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with a notable downregulation of genes involved in photosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis. The dramatic decline in PSII efficiency revealed by OJIP analysis is underpinned by massive and coordinated repression of photosynthetic genes, including components of photosystem II (IbPSB28, IbPSBO2, IbPSBQA, IbPSBX), photosystem I (IbPSAD2, IbPSAH1, IbPSAK, IbPSAL1/2, IbPSAO1/2/3), electron-transfer chain (IbETFBETA), and nearly all light-harvesting complexes (IbLHCB1–6, IbLHCA1–4; log2FC −4.1 to −9.8). Thus, the OJIP-derived collapse of energy trapping and electron transport fluxes directly reflects the systemic transcriptional shutdown of the photosynthetic electron transport chain. The repression of key chlorophyll biosynthesis genes, such as HEMA1, HEMC, CHLI, ChLH, POR1, and CAO, is consistent with the observed loss of chlorophyll content and aligns with findings in other albino mutants [34,43]. For example, HEMA1, which encodes glutamyl-tRNA reductase, is a rate-limiting enzyme in the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway, and its downregulation has been linked to albinism in arabidopsis and tobacco [44,45]. Similarly, the drastic reduction in POR1 expression (log2FC = −5.51) likely impairs the conversion of protochlorophyllide to chlorophyllide, a critical step in chlorophyll synthesis [46]. The simultaneous downregulation of chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation genes further supports the interpretation that plastid development is globally impaired in the mutant. In typical pigment-deficiency mutants, degradative genes are often induced; here, their repression suggests that chloroplast maturation is arrested at an early stage, preventing normal establishment of plastid metabolic pathways.

As sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) is an autohexaploid (6×) species, its genome contains multiple highly similar homologous and paralogous copies. The currently available Taizhong 6 reference genome (with high-quality genome annotation) is a collapsed assembly representing essentially one haplotype set. When short RNA-seq reads are mapped to such a reference using HISAT2 with default parameters, reads originating from highly conserved paralogous genes may map ambiguously or be assigned to a single copy, potentially leading to conflated expression estimates and reduced ability to distinguish expression differences among paralogs. Although this limitation is common in current transcriptomic studies of sweet potato and does not invalidate the overall expression patterns reported here.

The downregulation of PSY, a key enzyme of abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis, suggests an increase in carotenoid degradation, which may exacerbate the loss of carotenoids in the mutant [30,47]. This imbalance between biosynthetic and degradative pathways is a hallmark of albino mutants and has been reported in wheat and tomato [47,48]. Additionally, the downregulation of GLK1, a transcription factor regulating chloroplast development, likely contributes to the defective chloroplast ultrastructure and reduced expression of photosynthesis-related genes [35]. The coordinated downregulation of photosynthesis-related DEGs, including those encoding photosystem II, photosystem I, and ATP synthase components, further explains the compromised photosynthetic performance in the mutant.

The albino phenotype of the sweetpotato mutant likely results from a genetic mutation affecting a key regulator of chloroplast development or pigment biosynthesis. While the exact mutation remains unidentified, the downregulation of GLK1 and other pigment biosynthesis genes suggests a disruption in the transcriptional regulatory network. Similar mechanisms have been reported in Arabidopsis, where mutations in genes like CLB6 or SIG6 lead to albinism by impairing chloroplast biogenesis [49]. The broad repression of chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthetic genes is likely influenced by upstream transcriptional control. The strong downregulation of IbGLK1, a known master regulator of chloroplast development, together with reduced expression of other chloroplast-associated regulators, suggests disruption of plastid–nucleus signaling. Such impairment could centrally suppress multiple pigment pathways simultaneously, providing a plausible upstream basis for the albino phenotype. To fully validate the proposed regulatory model, it is essential to identify the causal mutation through whole-genome resequencing, genetic mapping, or other high-resolution genomic approaches. Future studies should therefore prioritize precise mutation detection and subsequently assess its functional significance using CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing.

In addition to the global repression of pigment biosynthesis, our transcriptomic results revealed a marked activation of several defense-related metabolic pathways, including camalexin and indole-derived phytoalexins. This transcriptional reprogramming is consistent with a compensatory response to photo-oxidative stress. Because the albino mutant lacks functional chloroplasts capable of dissipating excess excitation energy, even low light conditions can generate elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The upregulation of these defense pathways therefore likely reflects an adaptive mechanism aimed at mitigating ROS accumulation and maintaining cellular redox homeostasis. Such compensatory activation of stress-related metabolism has also been reported in other chloroplast-defective mutants and stress-induced albino phenotypes, supporting the interpretation that defense pathway induction is a downstream consequence of chloroplast dysfunction rather than a primary cause of albinism.

Moreover, the metabolic and transcriptomic data suggest that the albino mutant may serve as a valuable model for studying the interplay between photosynthesis, secondary metabolism, and stress responses. The upregulation of stress-related pathways in the mutant indicates a compensatory mechanism that warrants further investigation, particularly in the context of abiotic stress tolerance [50]. Because chloroplast function is severely impaired while multiple secondary metabolic pathways remain active or even enhanced, this mutant provides a unique natural system for dissecting the dissociation between photosynthetic capacity and secondary metabolism. Such a model could help clarify how plants reallocate metabolic resources in the absence of functional chloroplasts and identify regulatory nodes that uncouple these processes. Additionally, comparative analyses with other albino mutants in sweetpotato or related species could elucidate conserved mechanisms underlying chlorophyll deficiency.

In conclusion, the albino leaf mutant in sweetpotato exhibits profound defects in chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis, chloroplast development, and photosynthetic function, driven by significant transcriptional and metabolic reprogramming. This study represents the first comprehensive integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses to investigate albino leaf formation in sweetpotato, a genetically complex hexaploid crop. By combining multi-omics approaches, our work provides an unprecedented systems-level perspective on the molecular basis of chloroplast failure and associated metabolic shifts. These findings contribute to our understanding of albinism in plants and highlight the potential of this mutant as a model for studying chloroplast biogenesis and metabolic regulation. Future research should aim to identify the genetic basis of the albino phenotype and explore its applications in improving sweetpotato resilience and productivity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121513/s1. Figure S1: Correlation analysis among metabolome samples. Figure S2: Correlation analysis among transcriptome samples. Table S1. Primers and sequences for qRT-PCR. Table S2. Summary of the 1089 detected metabolites with annotation. Table S3. Pairwise comparisons in the experiment for metabolomics. Table S4. Summary of RNA-seq reads statistics. Table S5. Pairwise comparisons in the experiment for transcriptomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D., Y.L., G.Z. and Q.C.; Methodology, X.D. and D.Z.; Software, L.Z. and D.Z.; Validation, X.D. and L.Z.; Formal analysis, X.D. and A.Z.; Investigation, Z.Z., R.Y., Y.W., J.W., Q.L. and T.N.; Resources, Z.Z.; Writing—original draft, X.D. and Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, X.D., Y.L., S.X., G.Z. and Q.C.; Visualization, X.D.; Supervision, X.D.; Project administration, Q.C.; Funding acquisition, Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the earmarked fund for the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1202702), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-10-GW01), the “JBGS” Project for the Revitalization of the Seed Industry in Jiangsu Province (JBGS [2021] 010), and the Project for the Protection of Taxa and Germplasm Resources.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-Seq data from this study were deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database under the accession number PRJCA047514.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Douzery, E.J.; Snell, E.A.; Bapteste, E.; Delsuc, F.; Philippe, H. The timing of eukaryotic evolution: Does a relaxed molecular clock reconcile proteins and fossils? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15386–15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, Y. Identification and fine mapping of qCTH4, a quantitative trait loci controlling the chlorophyll content from tillering to heading in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hered. 2012, 103, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Long, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Niu, M.; Zheng, M.; Wang, D.; Wan, J. A rice White-stripe leaf3 (wsl3) mutant lacking an HD domain-containing protein affects chlorophyll biosynthesis and chloroplast development. J. Plant Biol. 2016, 59, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Li, X.-P.; Razeghifard, R.; Anderson, J.M.; Niyogi, K.K.; Pogson, B.J.; Chow, W.S. The multiple roles of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-protein complexes define structure and optimize function of Arabidopsis chloroplasts: A study using two chlorophyll b-less mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, M.; He, J.; Xu, P.; Shao, M.; Chu, P.; Guan, R. Fine mapping of a dominant gene conferring chlorophyll-deficiency in Brassica napus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ping, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Yin, J. Genetic mapping and physiological analysis of chlorophyll-deficient mutant in Brassica napus L. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Li, F.; Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Fu, Y.; Liu, W. Newly identified CSP41b gene localized in chloroplasts affects leaf color in rice. Plant Sci. 2017, 256, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Wang, S.; Ling, Y.; Sang, X.; He, G. Characteristics of photosynthesis in two leaf color mutants of rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 2304–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, M.; Yuan, F.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Yi, C. Mutation of the light-induced yellow leaf 1 gene, which encodes a geranylgeranyl reductase, affects chlorophyll biosynthesis and light sensitivity in rice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sun, X.; Li, C.; Huan, R.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, F.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P.; Ma, F. Map-based cloning and characterization of the novel yellow-green leaf gene ys83 in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 111, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.M.; Carrion, C.A.; Costa, M.L.; Desel, C.; Kieselbach, T.; Funk, C.; Krupinska, K.; Guiamet, J. Extra-plastidial degradation of chlorophyll and photosystem I in tobacco leaves involving ‘senescence-associated vacuoles’. Plant J. 2019, 99, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-F.; Xu, Y.-X.; Ma, J.-Q.; Jin, J.-Q.; Huang, D.-J.; Yao, M.-Z.; Ma, C.-L.; Chen, L. Biochemical and transcriptomic analyses reveal different metabolite biosynthesis profiles among three color and developmental stages in ‘Anji Baicha’(Camellia sinensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Han, J.; Zhu, B.; Jia, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, R.; Deng, W.-W.; Zhang, Z.-Z. Significantly increased amino acid accumulation in a novel albino branch of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Planta 2019, 249, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yue, C.; Cao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Biochemical and transcriptome analyses of a novel chlorophyll-deficient chlorina tea plant cultivar. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shi, N.; An, X.; Liu, C.; Fu, H.; Cao, L.; Feng, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhang, L. Candidate genes for yellow leaf color in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and major related metabolic pathways according to transcriptome profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Yang, F.; Shi, S.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Huang, D.; Wang, C. Transcriptome characterization of Cymbidium sinense ‘Dharma’ using 454 pyrosequencing and its application in the identification of genes associated with leaf color variation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-x.; Yang, S.-b.; Lu, Z.; He, Z.-c.; Ye, Y.-l.; Zhao, B.-b.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Cytological, physiological, and transcriptomic analyses of golden leaf coloration in Ginkgo biloba L. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.a.; Ma, L.; Li, L.; Yang, R.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis discovers novel candidate genes related to leaf color in a Lagerstroemia indica yellow leaf mutant. Genes. Genom. 2015, 37, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, G. Chlorophyll mutations in barley. Acta Agric. Scand. 1954, 4, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Zeng, F.; Lei, S.; Chen, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wen, J.; Shen, J.; Ma, C.; Tu, J. Two duplicate CYP704B1-homologous genes BnMs1 and BnMs2 are required for pollen exine formation and tapetal development in Brassica napus. Plant J. 2010, 63, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Moeinzadeh, M.-H.; Kuhl, H.; Helmuth, J.; Xiao, P.; Haas, S.; Liu, G.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Z.; Fan, W. Haplotype-resolved sweet potato genome traces back its hexaploidization history. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. The Subread aligner: Fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Cheng, L.; Dai, C.; Gao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Kang, C. Gene expression profiling of the shoot meristematic tissues in woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; Qin, Z.; Deng, Y. Comparative physiology and transcriptome analysis reveals that chloroplast development influences silver-white leaf color formation in Hydrangea macrophylla var. maculata. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Q.-Q.; Zhuo, B.-P.; He, J.-R. Transcriptome analysis reveals genes associated with leaf color mutants in Cymbidium longibracteatum. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, B.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, G. Phenotype and transcriptome analysis reveals chloroplast development and pigment biosynthesis together influenced the leaf color formation in mutants of Anthurium andraeanum ‘Sonate’. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of a yellow-green leaf mutant in birch (Betula platyphylla × B. Pendula). Forests 2019, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wei, X.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, R.; Huang, J.; Xu, X. Fine mapping and identification of a novel albino gene OsAL50 that is required for chlorophyll biosynthesis and chloroplast development in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 103, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.; Robertson, D.; Bowen, C.; Anderson, I. Chloroplast ultrastructure in pigment-deficient mutants of Zea mays under reduced light. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1973, 45, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Wang, T.; Jia, Z.-H.; Guo, Z.-R.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Wang, G. Photosystem disorder could be the key cause for the formation of albino leaf phenotype in Pecan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, H.; Li, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J. Loss of GLK1 transcription factor function reveals new insights in chlorophyll biosynthesis and chloroplast development. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 3125–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, D.; Long, C. Different phenylalanine pathway responses to cold stress based on metabolomics and transcriptomics in Tartary buckwheat landraces. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F.; Cui, S. Transcriptome analysis reveals the crucial role of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in low temperature response in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus. Genes 2024, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-D.; Han, L.-S.; Li, G.-Y.; Yang, K.-L.; Shen, Y.-L.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J.-F.; Wang, E.-P. A Comparative Study of the Chemical Composition and Skincare Activities of Red and Yellow Ginseng Berries. Molecules 2024, 29, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hammou, R.; El Caid, M.B.; Harrouni, C.; Daoud, S. Germination enhancement, antioxidant enzyme activity, and metabolite changes in late Argania spinosa kernels under salinity. J. Arid. Environ. 2023, 219, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaba, M.; Ito, H.; Morita, R.; Iida, S.; Sato, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Kawasaki, S.; Tanaka, R.; Hirochika, H.; Nishimura, M. Rice NON-YELLOW COLORING1 is involved in light-harvesting complex II and grana degradation during leaf senescence. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, S.; Bertini, L.; Falconieri, G.S.; Baccelli, I.; Timperio, A.M.; Caruso, C. A metabolic profiling analysis revealed a primary metabolism reprogramming in Arabidopsis glyI4 loss-of-function mutant. Plants 2021, 10, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, P.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. Insights into the physiological, molecular, and genetic regulators of albinism in Camellia sinensis leaves. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1219335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormac, A.C.; Fischer, A.; Kumar, A.M.; Söll, D.; Terry, M.J. Regulation of HEMA1 expression by phytochrome and a plastid signal during de-etiolation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2001, 25, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-P.; Yao, Q.-H.; Wang, L.-J. Expression of yeast Hem1 controlled by Arabidopsis HemA1 promoter enhances leaf photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 4369–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Song, J.-Y.; Jung, Y.J.; Reinbothe, S.; Park, Y.-I.; Lee, S.Y.; Pai, H.-S. Cell growth defect factor1/chaperone-like protein of POR1 plays a role in stabilization of light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3944–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filyushin, M.; Shchennikova, A.; Kochieva, E. Circadian Regulation of Expression of Carotenoid Metabolism Genes (PSY2, LCYE, CrtRB1, and NCED1) in Leaves of Tomato Solanum lycopersicum L. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 518, 393–397. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Song, G.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Fan, Q.; Huang, C.; Sui, X.; Chu, X.; Guo, D. Cloning of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene (TaNCED1) from wheat and its heterologous expression in tobacco. Biol. Plant. 2014, 58, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Nava, M.d.; Gillmor, C.S.; Jiménez, L.F.; Guevara-García, A.; León, P. CHLOROPLAST BIOGENESIS genes act cell and noncell autonomously in early chloroplast development. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).