Abstract

A severe leaf blight disease was observed on Nageia fleuryi in Fuzhou, China, during 2022–2023, causing necrosis on more than 60% of young leaves in both urban and plantation trees. This study aimed to identify the causal agent of the disease. The pathogen was consistently isolated from symptomatic tissues, and pathogenicity tests confirmed its ability to reproduce the disease on detached leaves, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. The representative isolate ZB-2 produced gray, cottony colonies and curved, 3-septate conidia with a swollen third cell, morphologically resembling Curvularia pseudobrachyspora. Multilocus phylogenetic analyses based on ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α sequences placed ZB-2 firmly within the C. pseudobrachyspora clade, confirming its identity. This study constitutes the first global record of C. pseudobrachyspora as a pathogen of leaf blight on N. fleuryi.

1. Introduction

The fungal genus Curvularia belongs to the family Pleosporaceae within the order Pleosporales of Ascomycota, comprises over 230 species, which are commonly found as soil inhabitants, plant pathogens, or endophytes [1]. Morphological characterization continues to serve as an essential component in fungal identification, with multiseptate conidia and a distinctly curved cell of conidia being diagnostic characters of Curvularia. However, some species, such as C. cybopogonis, C. ryleyi, and C. protuberata, typically produce straight rather than curved conidia [2]. Moreover, many Curvularia species exhibit morphological similarities and overlapping conidial dimensions. And the genera Curvularia and Bipolaris often lack clear morphological distinctions. Consequently, phylogenetic analyses utilizing multilocus sequence data from rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), large subunit (LSU), and translation elongation factor 1-α (Tef1-α) genes have become powerful tools for accurately identifying Curvularia species [3].

Curvularia species are significant phytopathogens worldwide. For example, C. lunata, the type species of the genus, infects staple crops such as rice, maize, and wheat, as well as forage grasses and other members of the Poaceae family. These infections often result in substantial yield losses in agricultural and livestock production. In recent years, several new plant diseases caused by C. lunata have been reported, including tomato and mulberry blight, as well as leaf spot on lotus, corn, and banana [4,5,6].

Nageia fleuryi (Hickel) de Laub. 1987, a member of the family Podocarpaceae, is primarily distributed in China (Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Taiwan, and Yunnan provinces), and in parts of Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam [7,8]. It can grow up to 30 m in height, with a pyramidal crown, and is widely cultivated as an ornamental tree in landscaping [9,10]. Its wood is valued for the production of musical instruments and household tools, while extracts from the plant contain norditerpenoids and biflavones with notable cytotoxic activity [11]. Due to its significant value, the natural resources of N. fleuryi have been heavily exploited, leading to a substantial decline in wild populations. Although minor diseases such as anthracnose and sooty mold have been observed in natural populations, they have not caused serious damage.

However, in May and June 2022, a severe leaf blight was observed on N. fleuryi used for landscaping at the campus of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. Approximately 65% of the new leaves exhibited necrosis that expanded from the tips to cover up to half of the lamina. In June 2023, nearly all trees in a newly established N. fleuryi plantation at Lingshi Mountain showed similar symptoms, suggesting an emerging threat to this species in southeastern China. The objectives of this study were to (i) isolate and confirm the causal agent of the disease following Koch’s postulates; (ii) identify the species of the pathogen of leaf blight through morphological characteristics and gene phylogenetic analysis. Collectively, these results will provide a foundation for the diagnosis of N. fleuryi leaf blight.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Survey and Fungal Isolation

From May to June, the leaf blight disease of N. fleuryi was photographed using a Canon EOS M6 digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and samples were collected from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (26°05′08.5″ N 119°13′49.9″ E) in 2022 and Lingshi Mountain (25°39′59.5″ N, 119°13′11.4″ E) in 2023 (Figure 1A). The infected leaves were surface-sterilized sequentially in 75% alcohol (30 s) and 5% NaOCl (2 min), followed by rinsing and drying. Leaf tissues from lesion margins were cut into small pieces (5 × 5 mm) and placed in Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) supplemented with 50 mg/mL of ampicillin. The PDA plates were incubated at a constant temperature of 25 °C using a biochemical incubator (SPX-250, Ningbo Jiangnan Instrument Factory, Ningbo, China). Emerging hyphae were transferred to fresh PDA plates and incubated at 25 °C for purification. The isolates were preserved in 25% glycerol at −80 °C at the Institute of Forest Protection, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, for further study.

Figure 1.

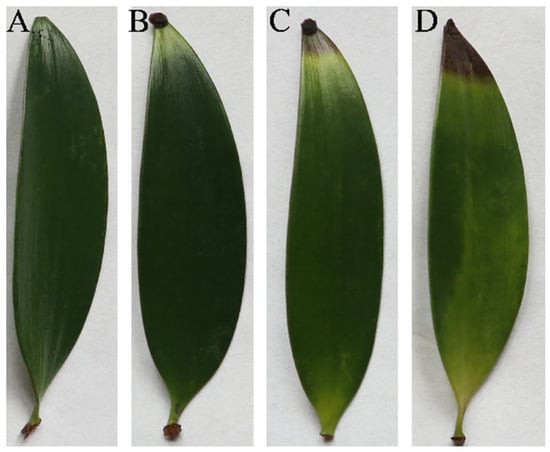

Naturally occurring leaf symptoms in Nageia fleuryi. (A) Different stages of infection (Lingshi Mountain). (B) Necrotic areas expanded toward the leaf base. (C) Fungal fruiting bodies. Scale bars = 4 mm.

2.2. Pathogenicity Tests

The pathogenicity of six isolates was evaluated on detached, surface-sterilized young leaves of N. fleuryi. PDA cultures were incubated at 25 °C for 5 days, and five PDA mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) were taken from the margins of each colony. Each plug was placed on the tip of a prepared leaf (one plug per leaf). PDA plugs without mycelia served as controls. After symptom development, the pathogens were reisolated from diseased tissues using the same method, and their morphology was compared with the original isolates to fulfill Koch’s postulates.

2.3. Morphological Identification

For colony morphology, representative isolate ZB-2 was selected and incubated on PDA for five days. Plugs were obtained with a sterile punch (Φ = 5 mm) from the colony margins, transferred to the center of the new PDA plates, and incubated at 25 °C. Colony growth, color, texture, and margin characteristics were recorded daily. The colony diameters were measured every 24 h by the crisscross method, and the colony growth rate was calculated.

For microscopic observations, conidial and conidiophore characteristics were examined and photographed under a light microscope (ECLIPSE E200 MV, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The size of the 100 conidia was measured, and the conidial color, septation, and cell morphology were recorded. Identification followed descriptions in Manamgoda et al. (2014) and Deng et al. (2002) [12,13].

2.4. DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA of the isolate ZB-2 was extracted using a Fungus DNA Kit (D3390, OMEGA, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The partial internal transcribed spacer (ITS), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and translation elongation factor 1-α (Tef1-α) genes were amplified using primers ITS1/ITS4 [14], Gpd1/Gpd2 [15], and EF1-983F/EF1-2218R [16], respectively. The primers were synthesized by Shangya Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Fuzhou, China), and stored at −20 °C. Gene fragments were amplified in a 25 μL reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL Rapid Taq Master Mix (P222, Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 1 μL template DNA (10 ng). The same PCR conditions were used for all primer sets. The amplification procedure was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a thermal cycler (S1000, Bio-Rad, Singapore).

PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis using 1% agarose at 120 V for 20 min to evaluate DNA quality, then purified using the EasyPure Fast Gel Extraction Kit (EG101, Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China), and cloned into the pMD18-T vector. Sequencing was performed by Shangya Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Fuzhou, China) using the Sanger method (ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The final sequences were deposited into NCBI GenBank and obtained the accession number (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of fungal strains used for phylogenetic analyses in this study.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

Multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) was performed using concatenated ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α sequences. Closely related sequences were retrieved from GenBank and selected for phylogenetic analysis. The accession numbers of all selected sequences used for phylogenetic analysis are listed in Table 1. Sequences were aligned using the MAFFT online service, edited with BioEdit (version 7.6.2.1), and concatenated in the order of ITS-GAPDH-Tef1-α. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA version 11.0 using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method. The stability of the branches was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replications.

3. Results

3.1. Symptom Description, Fungal Isolation, and Pathogenicity

At the early stage of infection, small brown lesions first appeared on the tips of young leaves. As the disease progressed, the necrotic areas gradually expanded toward the leaf base, and the affected tissues turned dark brown and shriveled (Figure 1B). In the late stage, approximately half of the leaf area was rotten, often accompanied by severe blight symptoms (Figure 1A). Numerous small black spots, corresponding to the fungal fruiting bodies, were visible on the abaxial surface of the diseased leaves (Figure 1C).

Five fungal isolates were isolated from the boundary between diseased and healthy tissues, and shared the same morphological characteristics. After inoculation with the representative strain ZB-2, typical leaf blight symptoms developed on N. fleuryi leaves under moist conditions. At approximately 3 days post-inoculation (dpi), slight chlorosis appeared at the leaf tips (Figure 2B). By 5 dpi, the chlorotic area gradually expanded downward along the leaf blade, and the tissue at the junction between healthy and diseased areas became yellowish-green (Figure 2C). At 8 dpi, the tips of the infected leaves turned dark brown and necrotic, with the necrotic area further enlarging toward the leaf base (Figure 2D). No symptoms were observed on control leaves inoculated with sterile PDA plugs (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Disease symptoms on detached Nageia fleuryi leaves inoculated with isolate ZB-2. (A) Healthy control leaf inoculated with sterile PDA plug. (B) Chlorosis appearing at leaf tips at 3 dpi. (C) Expansion of chlorotic area at 5 dpi. (D) Development of brown necrotic lesions at 8 dpi.

3.2. Morphological Characteristics of Pathogenic Fungus

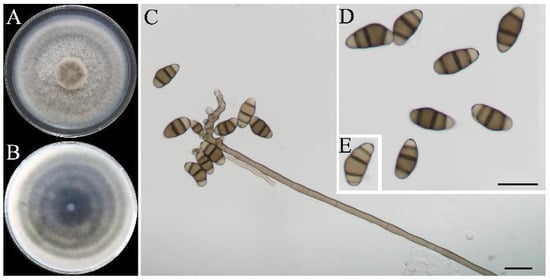

Colonies of ZB-2 on PDA reached the edge of a 9 cm Petri dish after incubation at 25 °C for 8–9 days. The colonies were cinereous to gray, fluffy to cottony, and convex with a papillate surface. The colony margin was irregular, circular, undulate, and rhizoid, and the reverse side appeared dark brown (Figure 3A,B). Conidiophores and conidia were observed on the PDA plates at 7 days post-inoculation. Conidiophores were macronematous, solitary, unbranched, septate, apically geniculate, pale brown, or brown (Figure 3C). Conidia solitary, broadly elliptical, curved (usually with the third cell from the base swollen), smooth, pale to mid brown, mostly 3-septate (occasionally 4-septate, Figure 3D,E), 21.5 ± 2.6 × 10.3 ± 1.2 um (n = 20). These morphological characteristics agree with the description of Curvularia pseudobrachyspora [17].

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics of isolate ZB-2. (A) Colony morphology (front view, 9 d on PDA); (B) colony morphology (reverse view, 9 d on PDA); (C) conidiophores and conidia; (D,E) solitary conidia. Scale bars = 20 um.

3.3. Molecular Identification

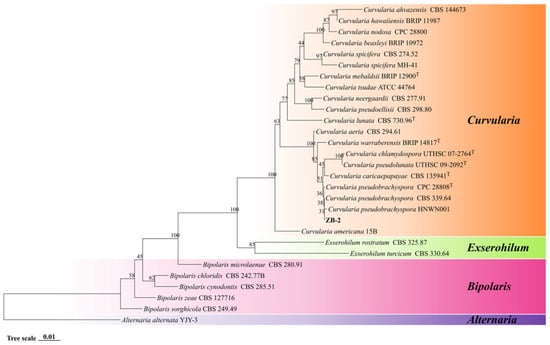

Partial sequences of ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α of ZB-2 were successfully sequenced and submitted to GenBank. The ITS sequence of ZB-2 showed 98% similarity with Curvularia pseudobrachyspora CPC 28808 (NR164423.1); GAPDH showed 100.0% identity to C. pseudobrachyspora strain PL2412 (PX088163.1), NCK0927 (LC802646.1), CBS 207.59 (MN688839.1), and Tef1-α showed 99.89% identity to C. pseudobrachyspora NCK0927 (LC802656.1).

The phylogenetic tree derived from concatenated sequences of ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α supported that ZB-2 belongs to C. pseudobrachyspora with high confidence (Figure 4). Combining morphological and phylogenetic data, ZB-2 was identified as C. pseudobrachyspora.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of combined ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α sequences based on the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method.

4. Discussion

This study identified Curvularia pseudobrachyspora as the causal agent of a newly emerging leaf blight disease on Nageia fleuryi in Fujian Province, southeastern China. Pathogenicity tests confirmed that the fungus consistently caused typical symptoms on detached leaves, and the same organism was reisolated, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. Morphological features combined with multilocus phylogenetic analysis of ITS, GAPDH, and Tef1-α sequences verified the identity of the pathogen as C. pseudobrachyspora. To our knowledge, this is the first report of C. pseudobrachyspora causing disease on N. fleuryi worldwide.

Members of the genus Curvularia are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions and are known to occur as saprobes, endophytes, or pathogens on a wide range of hosts [12,17]. Several Curvularia species, including C. lunata, C. geniculata, and C. eragrostidis, are important phytopathogens that cause leaf spot, blight, or seedling diseases on cereals, grasses, and ornamentals [18,19,20]. Although C. pseudobrachyspora has previously been reported primarily as a saprophytic species isolated from soil and plant debris [17,21], recent studies have demonstrated that it can act as a plant pathogen under certain conditions. In the past few years, C. pseudobrachyspora has been reported to cause leaf spot diseases on several unrelated host plants, including hemp (Cannabis sativa), banana (Musa acuminata), and coconut (Cocos nucifera) [22,23,24], indicating that this species possesses broader pathogenic potential than previously recognized. However, no published records report C. pseudobrachyspora infecting N. fleuryi. Therefore, our findings document the first confirmed occurrence of C. pseudobrachyspora as a foliar pathogen of N. fleuryi and expand the known host range of this species. This highlights the emerging importance of C. pseudobrachyspora as a pathogen capable of infecting phylogenetically diverse plant lineages.

The morphological characteristics of isolate ZB-2, including curved, 3-septate conidia with the third cell swollen, and geniculate conidiophores, matched well with the descriptions of C. pseudobrachyspora, but there are occasionally four septa in ZB-2, which were not in the C. pseudobrachyspora-type strain [17]. Therefore, accurate identification within Curvularia is challenging due to the overlapping morphological features among species. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis provided strong support for the placement of isolate ZB-2 in the C. pseudobrachyspora clade, confirming its taxonomic identity [25]. These results highlight the importance of integrating morphological and molecular data for reliable identification of Curvularia species associated with plant diseases [26,27,28]. Climatic conditions at the time when symptoms first appeared were not recorded during field inspections, and therefore no direct conclusions can be drawn regarding the influence of rainfall, humidity, or other environmental factors on disease development. Future studies incorporating continuous environmental monitoring and multi-season observations will be necessary to assess whether climatic variables contribute to the epidemiology of this newly identified leaf blight.

From a management perspective, integrated approaches that combine effective fungicides (e.g., DMI fungicides such as propiconazole and tebuconazole [29,30,31]) with proper pruning, sanitation, and environmental regulation (e.g., reducing excessive moisture) are crucial for lowering disease incidence and slowing the development of resistance [32,33,34]. Additionally, future studies should explore the epidemiology and infection biology of C. pseudobrachyspora—including its survival structures, dispersal routes, and potential alternative hosts—to improve the prediction and management of disease outbreaks. In conclusion, this study reports C. pseudobrachyspora as a new foliar pathogen of N. fleuryi in China. These findings provide a foundation for the diagnosis and management of C. pseudobrachyspora leaf blight and contribute to a better understanding of emerging Curvularia-induced diseases in ornamental conifers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Y., L.M., Y.L. (Yuyang Lan), and B.L.; methodology, Q.Z., P.Y., L.M., Y.L. (Yunqing Liang), and G.L.; software, P.Y., L.M., B.L., Y.L. (Yuyang Lan), Y.L. (Yunqing Liang), and Z.H.; validation, P.Y., W.X., and G.L.; investigation, L.M., Y.L. (Yuyang Lan), W.X., and Q.Z.; resources, Q.Z.; data curation, P.Y., L.M., B.L., and Z.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Y., L.M., and Y.L. (Yuyang Lan); writing—review and editing, Q.Z. and P.Y.; supervision, Q.Z.; project administration, Q.Z.; funding acquisition, Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University (KFB23052A), Fujian Forestry Science and Technology Programs (2024FKJ27), and Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2023J01435).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Shuaifei Chen (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University) for the technical support provided during fungal strain identification. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful work on our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marin-Felix, Y.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cai, L.; Chen, Q.; Marincowitz, S.; Barnes, I.; Bensch, K.; Braun, U.; Camporesi, E.; Damm, U.; et al. Genera of Phytopathogenic Fungi: GOPHY 1. Stud. Mycol. 2017, 86, 99–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manamgoda, D.S.; Rossman, A.Y.; Castlebury, L.A.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K. A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Re-Appraisal of the Genus Curvularia (Pleosporaceae): Human and Plant Pathogens. Phytotaxa 2015, 212, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Asaf, S.; Ahmad, W.; Jan, R.; Bilal, S.; Khan, I.; Khan, A.L.; Kim, K.-M.; Al-Harrasi, A. Diversity, Lifestyle, Genomics, and Their Functional Role of Cochliobolus, Bipolaris, and Curvularia Species in Environmental Remediation and Plant Growth Promotion under Biotic and Abiotic Stressors. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.Q.; Sun, X.T. First Report of Curvularia lunata Causing Leaf Spot on Lotus in China. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aroca, T.; Doyle, V.; Singh, R.; Price, T.; Collins, K. First Report of Curvularia Leaf Spot of Corn, Caused by Curvularia lunata, in the United States. Plant Health Prog. 2018, 19, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdElfatah, H.-A.S.; Sallam, N.M.A.; Mohamed, M.S.; Bagy, H.M.M.K. Curvularia lunata as New Causal Pathogen of Tomato Early Blight Disease in Egypt. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3001–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Hill, R.S.; Liu, J.; Biffin, E. Diversity, Distribution, Systematics and Conservation Status of Podocarpaceae. Plants 2023, 12, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Tian, S. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Nageia fleuryi (Hickel) de Laub. (Podocarpaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2022, 7, 1294–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Zou, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Fu, S.; Yang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhou, J. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of the Genus Nageia. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2024, 18, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Kodrul, T.M. First Fossil Record of the Genus Nageia (Podocarpaceae) in South China and Its Phytogeographic Implications. Plant Syst. Evol. 2010, 285, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Wu, X.-D.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.-P.; Zhao, Q.-S. Three New Abietane Diterpenoids from Podocarpus fleuryi. Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manamgoda, D.S.; Rossman, A.Y.; Castlebury, L.A.; Crous, P.W.; Madrid, H.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K.D. The Genus Bipolaris. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 79, 221–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, T. Axonomic Studies of Bipolaris (Hyphomycetes) from China I. Mycosystema 2002, 21, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Berbee, M.L.; Pirseyedi, M.; Hubbard, S. Cochliobolus Phylogenetics and the Origin of Known, Highly Virulent Pathogens, Inferred from ITS and Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Gene Sequences. Mycologia 1999, 91, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E. A Beauveria Phylogeny Inferred from Nuclear ITS and EF1-α Sequences: Evidence for Cryptic Diversification and Links to Cordyceps Teleomorphs. Mycologia 2005, 97, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Felix, Y. New Species and Records of Bipolaris and Curvularia from Thailand. Mycosphere 2017, 8, 1556–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; An, X.; Jin, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, T. Integrated High-Throughput Sequencing, Microarray Hybridization and Degradome Analysis Uncovers MicroRNA-Mediated Resistance Responses of Maize to Pathogen Curvularia lunata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Htun, A.A.; Aung, S.L.L.; Sang, H.; Deng, J.; Tao, Y. Fungal Species Associated with Tuber Rot of Foshou Yam (Dioscorea Esculenta) in China. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.P.; Crous, P.W.; Shivas, R.G. Cryptic Species of Curvularia in the Culture Collection of the Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium. Mycokeys 2018, 35, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinandez, H.S.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Udayanga, D.; Munasinghe, M.S.; Castlebury, L.A. Molecular Phylogeny and Morphology Reveal Two New Graminicolous Species, Curvularia aurantia sp. nov. and C. vidyodayana sp. nov. with New Records of Curvularia spp. from Sri Lanka. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2023, 12, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.V.; Wang, N.-Y.; Coburn, J.; Desaeger, J.; Peres, N.A. First Report of Curvularia pseudobrachyspora Causing Leaf Spot on Hemp (Cannabis Sativa) in Florida. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Peng, J.; Zeng, F.; Xie, Y.; Xie, P.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, X. First Report of Curvularia pseudobrachyspora Causing Leaf Spot on Banana in China. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 104, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabagi, A.M.; Zakari, M.S. Curvularia pseudobrachyspora Leaf Spot Disease of Coconut. Niger. J. Bot. 2025, 38, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S.; Maurya, A.; Rajawat, M.V.S.; Sharma, P.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Roy, M.; Saxena, A.K.; Singh, H.V. Multi-Gene Phylogenetic Approach for Identification and Diversity Analysis of Bipolaris maydis and Curvularia lunata Isolates Causing Foliar Blight of Zea mays. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-J.; Amenyogbe, M.K.; Chen, S.-Q.; Rashad, Y.M.; Deng, J.-X.; Luo, H. Morphological and Phylogenetic Analyses Reveal Two Novel Species of Curvularia (Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae) from Southern China. Mycokeys 2025, 120, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Prakash, O.; Sonawane, M.S.; Nimonkar, Y.; Golellu, P.B.; Sharma, R. Diversity and Distribution of Phenol Oxidase Producing Fungi from Soda Lake and Description of Curvularia lonarensis Sp. Nov. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z.-F.; Cheng, W.; Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde4, K.D.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. Diseases of Cymbopogon citratus (Poaceae) in China: Curvularia nanningensis sp. nov. Mycokeys 2020, 63, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Yang, C.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, L. Pathogenic Characteristics, Biological Characteristics and Drug Control Test of Pathogen Causing Rhombic-Spot of Phyllostachys heteroclada. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2021, 49, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, N.; Sun, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, J. Talaromyces funiculosus, a Novel Causal Agent of Maize Ear Rot and Its Sensitivity to Fungicides. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3978–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, F.; Chaisiri, C.; Zhu, Y.-T.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, M.-K.; Li, X.-C.; Yin, L.-F.; Yin, W.-X.; Luo, C.-X. Sensitivity of Venturia carpophila from China to Five Fungicides and Characterization of Carbendazim-Resistant Isolates. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3990–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Khan, M.; Khan, I. Phytopathological management through bacteriophages: Enhancing food security amidst climate change. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 51, kuae031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Li, C.-H.; Ali, Q.; Zhao, W.; Chi, Y.-K.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, F.; Yu, X.-Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, J.-T.; et al. Bacterial and Fungal Biocontrol Agents for Plant Disease Protection: Journey from Lab to Field, Current Status, Challenges, and Global Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ons, L.; Bylemans, D.; Thevissen, K.; Cammue, B.P.A. Combining Biocontrol Agents with Chemical Fungicides for Integrated Plant Fungal Disease Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).