Abstract

Embryo spots on potato seed enhance the efficiency of doubled haploid screening by facilitating selection. While the spots are known to involve anthocyanin accumulation, their genetic regulation remains unclear. Here, loci and genes regulating spot formation were investigated. An F1 population was generated by crossing the haploid inducer IVP101 (embryo-spotted male parent) with the diploid inbred line Y8 (non-spotted female parent). Subsequent BSA-seq of the extreme F1 pools mapped a locus to chromosome 10 (49.96–54.31 Mb). QTL mapping via a high-density genetic map of the F2 segregating population (derived from F1 selfing) identified four QTLs (on chromosomes 2, 5, 10, 11). These included the QTLs qSP10-1 (explaining 23.85% of phenotypic variance) and qSP11-1 (18.23%). qSP11-1 overlapped with the reported P locus encoding flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), whereas qSP10-1 confirmed the BSA-seq results. Integration of the BSA-seq and QTL mapping results narrowed the target gene locus to a 384.6 kb interval at the end of chromosome 10. Transcriptome sequencing of spotted vs. non-spotted F1 seed, together with gene expression profiling in the qSP10-1 interval, identified five differentially expressed candidate genes. These findings clarify the genetic basis of potato embryo spot formation and provide a reference for breeding and further research.

1. Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is an important tuber crop. The main currently cultivated varieties are autotetraploids (2n = 4x = 48) with highly heterozygous genomes [1]. In production, tetraploid main cultivars have narrow genetic background and low diversity, hindering the breeding of breakthrough varieties [2]. Potato germplasm resources encompass 107 wild relative species, four landrace (indigenous) cultivars, and modern varieties [3]. Among all tuber-bearing potato species, approximately three-quarters of the resources are diploid (2n = 24) [4]. These wild diploid resources are rich in genetic variation and possess a series of favorable traits including stress resistance, disease resistance, and insect resistance, serving as important genetic resources for broadening the genetic background of cultivated potatoes [5]. However, due to differences in ploidy levels and hybrid sterility, tetraploid cultivars cannot directly hybridize with diploid wild and cultivated species, resulting in difficulties in transferring the excellent traits of diploid potato species to tetraploid cultivars. To overcome the bottleneck in potato breeding, reducing tetraploids to doubled haploids (2n = 24) followed by hybridization with wild diploids to introduce and utilize excellent genes from wild species has become an important research direction [6]. Currently, various methods have been used to produce haploid and doubled haploid plants, such as in vitro anther and microspore culture, interspecific hybridization, hybridization with haploid inducer lines, and gene editing [7,8,9]. These technologies provide feasible approaches to accelerate the breeding process, and the early and accurate identification of doubled haploids is crucial for efficient screening of doubled haploids.

In potato, several doubled haploid inducer (HI) lines are available as pollen donors, such as “IVP101”, “IVP35”, “IVP48”, “phu1.22” (PI225682), and “PL4” (CIP596131.4). Among these, “IVP101” has been widely utilized and is a well-established inducer line [10,11,12,13]. These potato HI lines all carry dominant anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes, and the anthocyanins produced can form pigment bands at the embryo spots of seeds and stem nodes of seedlings [14]. The dominant anthocyanin marker they express (i.e., embryo spot) can be directly observed through seed morphology, facilitating the early identification of doubled haploids (without embryo spots) and true hybrids (with embryo spots). After hybridization with haploid inducer lines, the presence or absence of embryo spots is a key characteristic for identifying haploids; however, the genetic basis of these morphological markers remains unclear.

Anthocyanin biosynthesis is a complex pathway involving structural genes encoding pigment-synthesizing enzymes and transcription factors (TFs) that regulate their expression. In the tuber skin of tetraploid potato, anthocyanin biosynthesis is controlled by three genetic loci: D (Developer), P (Purple), and R (Red). Among these, P and R are structural genes encoding flavonoid-3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H) [15] and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) [16,17], respectively. The D locus, a regulatory gene, encodes the R2R3-MYB transcription factor StAN2, which modulates the expression of multiple anthocyanin structural genes in the tuber epidermis [18]. Similarly, in potato tuber flesh, two tandem R2R3-MYB transcription factors (StMYB200 and StMYB210) form a synergistic regulatory network with StbHLH1 to activate anthocyanin synthesis in parenchyma cells [19]. In floral tissues, a homologous gene of the anthocyanin 2 (AN2) gene family encoding an MYB transcription factor, designated StFlAN2, has been identified as the candidate gene for the F locus regulating flower color; introduction of StFlAN2 into white-flowering homozygous doubled haploid (DM) plants restored purple pigmentation [20]. Genetic studies have confirmed the epistatic effect of P over R [21]. The R locus (chromosome 2) and P locus (chromosome 11) are essential for red and purple pigmentation, respectively, across all potato tissues [22,23]. Biochemically, R encodes DFR and P encodes F3′5′H, as validated by molecular and enzymatic analyses [15,16,17,24,25].

The formation of embryonic spots in potato is regulated by the interaction of two genetic loci: P controls the synthesis of purple pigment, while B restricts pigment localization exclusively to the embryonic spot [23,26]. Consequently, the genes governing embryonic spot formation may exhibit pleiotropy: plants derived from spotted seeds display purple rings or bands on leaf blades, leaflet bases, stolon scale leaves, tuber eyebrows, and floral abscission zones [14]. The B locus was recently mapped to chromosome 10 (chr10, 48–60 Mb) via k-mer-based bulked segregant analysis [27]. Wang et al. [28] predicted a candidate gene at the B locus, which encodes an R2R3 MYB transcription factor and is highly expressed in the cotyledon base of spotted embryos yet undetectable in that of spotless embryos; however, its specific functional identity remains uncharacterized.

In this study, the classical inducer line IVP101 was used as the male parent, and an embryo spot-free diploid potato line as the female parent to construct F1 and F2 segregating populations. Through integrated analysis of bulked segregant analysis (BSA), QTL mapping using a high-density genetic map, and RNA-Seq, we aimed to identify loci and candidate genes controlling embryo spot formation. The signal on chromosome 11 overlapped with the position of the cloned P gene (F3′5′H) [15]. On chromosome 10, the candidate locus was narrowed down to a 384.6 Kb interval. Based on gene annotation, five candidate genes were screened and validated via qRT-PCR. These results will enhance our understanding of the genetic basis of embryo spot formation in potato and provide candidate targets for cloning and functional characterization of embryo spot-related genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Phenotypic Trait

Two diploid potato lines, IVP101 (male parent) and Y8 (female parent), were used as crossing parents in this study. Both materials were preserved and provided by the Joint Academy of Potato Science of Yunnan Normal University. IVP101 (StGp Phureja) is an inducer line widely utilized in potato distant hybridization, characterized by genomic heterozygosity, seeds with embryonic spots, purple-skinned and white-fleshed tubers, purple flowers, and stems rich in purple pigments. Y8 is an elite inbred line developed by the Joint Academy of Potato Science of Yunnan Normal University. It is characterized by seeds without embryonic spots, tubers with yellow skin and white flesh, white flowers, and green stems. F1 seeds were obtained via Y8 × IVP101 hybridization, sown in a greenhouse, and germinated to yield approximately 300 F1 plants. Two vigorously growing and highly self-fertile F1 plants were selected and designated as IYY30 and IYP31, respectively. Selfed seeds from these two F1 plants were randomly mixed and sown, ultimately generating an F2 genetic segregation population consisting of 174 lines.

F1 and F2 seeds were characterized based on the presence of purple seed spots. Spotted and nonspotted seeds were visually identified by recording the presence or absence of dark embryonic spots. Based on this simple visual assessment, each seed was assigned to one of two categories: Spotted (SP) or Nonspotted (NS).

2.2. DNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

For BSA-seq analysis, young leaf tissues were collected from 23 F1 seedlings derived from spotted seeds (producing spotted seeds after selfing) and 23 F1 seedlings derived from non-spotted seeds (producing non-spotted seeds after selfing), selected from approximately 300 F1 individuals. Genomic DNA was extracted from each sample, and equal amounts of DNA from each group were pooled to construct two libraries: the spotted embryo pool and non-spotted embryo pool for bulked segregant analysis sequencing (BSA-seq). Four samples were subjected to resequencing, including the parental lines IVP101 and Y8, as well as the two DNA pools (spotted and non-spotted). Library construction was performed using the Hieff NGS®DNA Library Prep Kit (YeasenBiotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Genomic DNA was extracted from young tissues of sequencing samples using the CTAB method. DNA concentration and purity were measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Qualified genomic DNA was fragmented by mechanical shearing via ultrasonication, followed by fragment purification, end repair, 3′-end adenylation, and ligation of sequencing adapters. Size selection was performed using agarose gel electrophoresis, and PCR amplification was conducted to generate sequencing libraries. Constructed libraries underwent quality control prior to sequencing; qualified libraries were sequenced on an Illumina platform. High-quality reads were filtered using the following criteria: (1) removal of adapter-contaminated reads; (2) exclusion of reads with >10% N content; (3) elimination of reads containing >50% bases with a Phred quality score <10.

2.3. Analysis of the BSA-Seq Data

Based on the alignment results of clean reads to the reference genome (DM8.1; www.bioinformaticslab.cn/pubs/dm8/, accessed on 10 April 2024) [29], redundant reads were filtered using Samtools (v1.9) [30] to ensure the accuracy of detection results. Subsequently, variant calling for SNPs and InDels was performed using the HaplotypeCaller algorithm (local haplotype assembly) in GATK (v3.8) (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk, accessed on 22 April 2024). Each sample was first processed to generate individual gVCFs, followed by population-level joint-genotyping. Final variant sets were obtained after hard filtering.

Euclidean Distance (ED) and SNP-index were calculated to identify genomic candidate regions associated with PSST. The ED algorithm is a method for detecting significantly divergent markers between two pools based on sequencing data and evaluating trait-associated genomic regions [31].

During analysis, SNPs with genotypic differences between the two pools were used to quantify base depth in each pool and compute ED values for individual loci. To eliminate background noise, raw ED values were subjected to power transformation [31]; in this study, the 5th power of raw ED was used as the association value for noise reduction. ED values were then fitted using the DISTANCE method.

2.4. QTL Mapping

Two vigorously growing F1 plants with high self-fertility (designated IYY30 and IYP31) were selected for self-pollination, ultimately generating an F2 genetic segregation population consisting of 174 lines. A genetic map containing 848,643 SNPs was constructed, and these SNPs were merged into 4464 filtered Bin markers. After linkage analysis, all Bin markers were assigned to 12 linkage groups (LG01–LG12), and the integrated genetic map spanned a total genetic distance of 1239.74 cM [32]. QTL IciMapping v4.2 software [33] was used for QTL analyses. The significance threshold value of the logarithm of odds (LOD) scores for QTL detection was 2.5; if the LOD ≥ 2.5, the site was considered to constitute a QTL for the trait, and the additive effect of each QTL and the contribution rate to the trait were calculated.

2.5. RNA Sequencing, Transcriptome Assembly, and Data Analysis

For accurate screening of candidate genes within the major QTL region, F1 seeds with and without embryonic spots, derived from the IVP101 × Y8 cross, were selected as experimental materials. Sample collection was performed following the method described by Wang et al. [28]; i.e., RNA was extracted from cotyledonary node regions collected from 1-week-old seedlings germinated from spotted or non-spotted seeds. Transcriptome sequencing were conducted by Wuhan MetWare Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China). mRNA was enriched using mRNA Capture Beads, followed by purification and heat-induced fragmentation. Fragmented mRNA was used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis in a reverse transcriptase mixture. During second-strand cDNA synthesis, end repair and dA-tailing were simultaneously performed. After adapter ligation, target fragments were purified and selected using Hieff NGS®DNA Selection Beads (YeasenBiotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), followed by PCR library amplification. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Novaseq X Plus platform. Transcriptome assembly was conducted using StringTie software (version 1.3.4d) [34]. Based on alignment results from HISAT2, transcript reconstruction was performed with StringTie, and gene expression levels across samples were quantified using RSEM software (version 1.2.22) [35]. Differential expression analysis between groups was performed using the DESeq2 package (version 1.10.1) in R language [36], with thresholds set at false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.01 and fold change ≥2. GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analyses were conducted using OmicShare tools (http://www.omicshare.com/tools, accessed on 12 August 2025), with FDR ≤ 0.05 considered significantly enriched.

2.6. Real-Time qPCR Analysis and Prediction of Conserved Protein Domains of Genes

Total RNA was extracted using the Plant RNA Kit (OMEGA, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using the All-in-One First-Strand Synthesis MasterMix (containing dsDNase). Remaining RNA was stored at −80 °C, and cDNA was stored at −20 °C for subsequent use.

Gene-specific primers were designed using the Primer 3 4.1.0 online tool, and synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., with EF-1-alpha as the reference gene (primer sequences in Table S1). qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Taq SYBR® Green qPCR Premix (Universal). The experiment included 3 independent biological replicates (n = 3) and 3 technical replicates per sample. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [37]. Six genes were selected, and correlation analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 based on the mean FPKM values and mean 2−ΔΔCt values of each gene in spotted and non-spotted embryo samples.

Candidate gene sequences were extracted based on the potato reference genome DM8.1. The DNA sequences were translated into amino acid sequences using the Open Reading Frame Finder tool from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/, accessed on 6 November 2025). Subsequently, the Conserved Domain Database Search (CD-Search) tool from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi, accessed on 6 November 2025) was utilized to retrieve the conserved domains of the amino acid sequences and examine their Protein classification.

3. Results

3.1. The Embryo Spot Trait Is Controlled by Two Genetic Loci

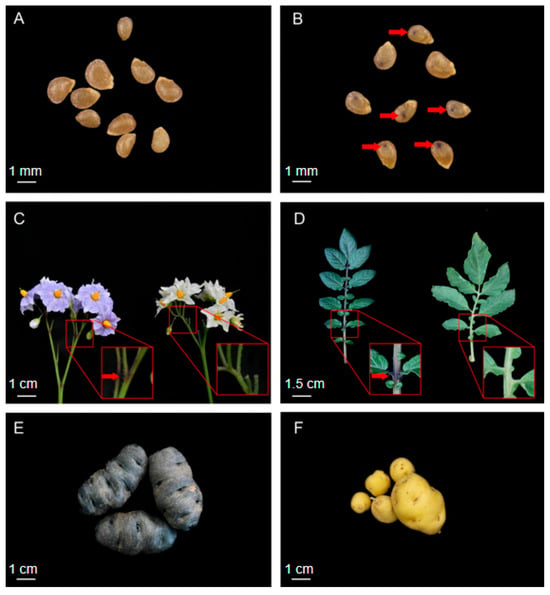

IVP101 carries a morphological marker that induces embryonic spotting in hybrid seeds when used as the male parent. The embryonic spot appears as a deep purple pigmentation at the cotyledon base, visible through the seed coat on both sides of the seed (Figure 1B). IVP101 also exhibits additional purple pigmentation traits: a purple floral abscission zone in inflorescences (Figure 1C), purple pigment accumulation at the petiole base, and purple tuber epidermis (Figure 1E). In contrast, Y8 (an advanced inbred line) produces non-spotted seeds (Figure 1A), lacks purple pigmentation in the floral abscission zone (Figure 1C) and petiole base (Figure 1D), and has a yellow tuber epidermis (Figure 1F). To investigate the genetic basis of the embryonic spot trait, the diploid inbred line Y8 (female parent) was crossed with IVP101 (male parent). F1 progeny from this cross exhibited a 1:1 segregation ratio (1195 spotted:1126 non-spotted; χ2 = 2.05, p = 0.15) for the embryonic spot phenotype. This ratio suggests that the locus controlling the trait is likely heterozygous in IVP101, as Y8 is highly homozygous and does not exhibit the embryonic spot trait. Selfing of IYP31 (a spotted F1 individual) produced seeds with a 9:7 segregation ratio (5845 spotted:4669 non-spotted; χ2 = 1.82, p = 0.18), indicating that the embryonic spot trait in this population is controlled by two independent genetic loci.

Figure 1.

Representative images of plants with and without embryonic spots. (A) Non-spotted and (B) spotted seeds. Red arrows indicate deep purple pigmentation at the embryonic cotyledon base. (C) Inflorescence pigmentation. Y8 inflorescences have green floral abscission zones and white flowers, whereas IVP101 inflorescences have purple floral abscission zones and purple flowers. (D) Leaf base pigmentation. Y8 has green leaf bases, while IVP101 has purple petiole bases with intense deep purple stripes. (E,F) Tuber pigmentation. Y8 has yellow tuber epidermis, whereas IVP101 has purple tuber epidermis.

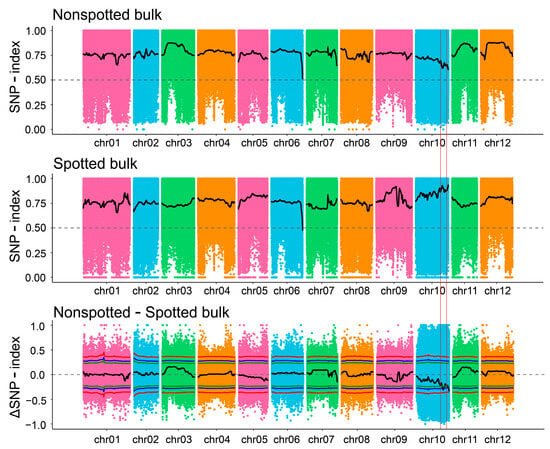

To identify genes controlling the embryonic spot trait, we performed BSA-seq analysis using the F1 segregating population. Sequencing generated 30.47 Gb of raw data for IVP101, 31.17 Gb for Y8, 34.49 Gb of reads for the spotted pool, and 30.79 Gb for the non-spotted pool (Table 1). Clean reads were aligned to the reference potato genome (DM8.1, http://www.bioinformaticslab.cn/pubs/dm8/, accessed on 10 April 2024) to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A total of 9,616,190 SNPs were detected via BSA-seq, including 6,003,585 transitions and 3,612,605 transversions. After quality filtering, 4,948,424 high-quality SNPs were retained. The ΔSNP-index was fitted using the DISTANCE method, and regions exceeding the association threshold were selected as trait-related intervals. At a 95% confidence level, three candidate regions were identified. Two closely linked and small intervals were discarded, retaining a single candidate interval on chr10 (49.96–54.31 Mb) (Figure 2, Table 2).

Table 1.

Sequence data of the parents and pools.

Figure 2.

Distribution of SNP-index association values across chromosomes.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of associated area information.

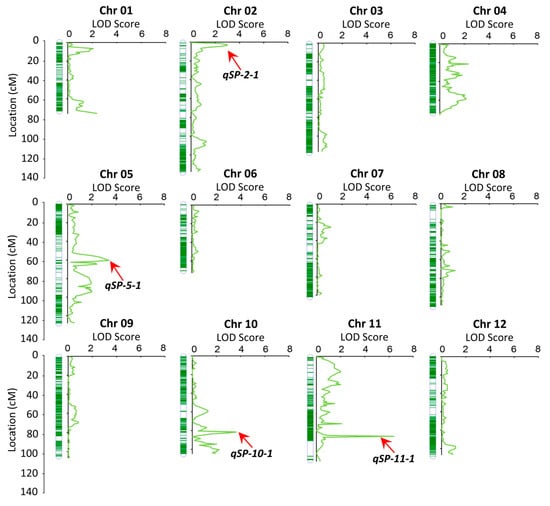

3.2. QTL Mapping of Embryo Spot Trait Using High-Density Genetic Map

To further validate and refine the candidate intervals, the present study, based on a high-density genetic map, employed the Inclusive Composite Interval Mapping (ICIM) method implemented in IciMapping v4.2 software, and identified a total of 4 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) distributed across 4 chromosomes (Table 3, Figure 3). Two major QTLs, designated qSP-10-1 and qS-11-1, explained 23.85% and 18.23% of the phenotypic variance (PVE), respectively. Notably, qS-11-1 colocalized with the previously reported P gene (DM8C11G21030; 41,514,416–41,520,754 bp). Furthermore, qSP-10-1 mapped within the chr10 interval (48–60 Mb) where the B locus was previously localized via k-mer-based bulked segregant analysis [27]. Collectively, QTL mapping using the high-density bin map confirmed that the embryonic spot trait is controlled by two major genes (B and P), with the B locus further refined to a 384.6 kb interval.

Table 3.

Detailed information of the mapped QTL.

Figure 3.

QTL mapping of the embryo spot trait in the F2 population was performed using a high-density genetic map. X-axis: LOD score; Y-axis: Genetic distance (centimorgan, cM). QTLs are labeled with their names (qSP2-1, qSP5-1, qSP10-1, qSP11-1).

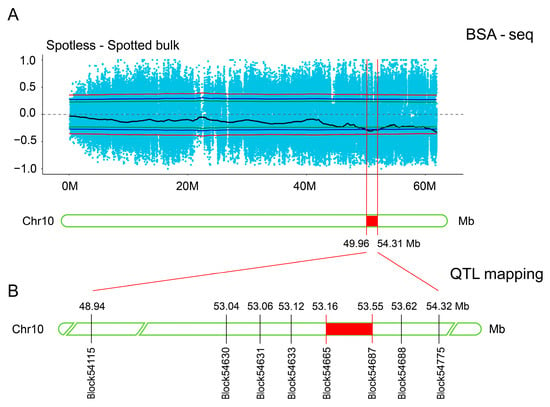

3.3. Further Mapping Analysis by Combining BSA-Seq with QTL Mapping

To dissect the genetic basis of the embryonic spot trait, two complementary populations were employed: BSA-seq analysis using the F1 segregating population, and QTL mapping with a high-density genetic map constructed from the F2 population. BSA-seq initially identified a trait-associated candidate interval on Chr10 (49.96–54.31 Mb). The F2 population, with its higher resolution and mapping efficiency, enabled fine-scale QTL mapping, which further narrowed the embryonic spot locus to a 384.6 kb interval on Chr10 (53.16–53.55 Mb; Block54665–Block54687; Figure 4B).These results demonstrate the efficacy of integrating BSA-seq for preliminary screening with high-resolution QTL mapping, successfully refining the trait-associated region from 49.96–54.31 Mb to 53.16–53.55 Mb. This approach highlights the utility of combining population genetic analyses with complementary mapping strategies in dissecting complex trait loci.

Figure 4.

Integration of BSA and QTL analyses refines the candidate interval to 384.6 kb. (A) candidate interval associated with the embryonic spot trait was identified on chromosome 10 (49.96–54.31 Mb) using BSA-seq. Blue scatter points represent sequencing data distribution, the black curve indicates the trend line, and the red vertical lines demarcate the interval. (B) QTL mapping further narrowed the candidate interval to 53.16–53.55 Mb. Note: The red shaded region on the chromosome indicates the jointly mapped interval.

3.4. Identification of Candidate Genes via RNA-Seq

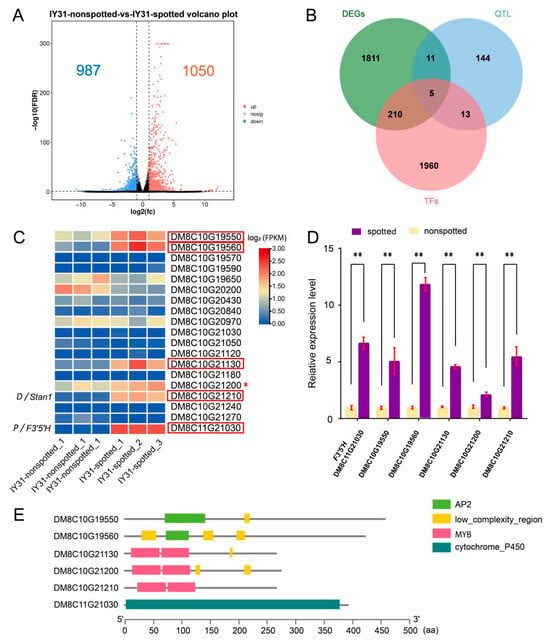

To further identify candidate genes within the refined interval, transcriptome sequencing was performed on spotted and non-spotted seeds, generating 38.15 Gb of raw reads (Table S2). Differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2 identified 2037 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with 1050 upregulated and 987 downregulated in spotted seeds (Figure 5A, Table S3). More highly expressed genes were observed in spotted seeds, which could be attributed to the fact that spotted seeds exhibit more complex physiological activities or metabolic processes than non-spotted seeds during seed development, thereby necessitating the involvement of more gene expression in regulatory processes.

Figure 5.

Analysis of candidate genes for embryonic spot formation. (A) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified by RNA sequencing. Orange and blue dots represent upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively; black dots represent genes with no expression change. (B) Candidate gene identification via integration of significant DEGs, QTL interval genes, and all transcription factors. (C) Expression heatmap of genes within and flanking the candidate interval based on transcriptome sequencing. Red boxes indicate the five significantly differentially expressed genes, including the P gene; asterisks (*) denote an additional MYB family member with a non-significantly differentially expressed FPKM value. (D) qRT-PCR was performed to validate the expression levels of five candidate genes and F3′5′H. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean from three replicates, and ** denote significance at p < 0.01 (t-test). (E) Prediction of protein conserved domains of five candidate genes and the F3′5′H gene.

Notably, transcription factors (TFs) play pivotal roles in plant pigment biosynthesis—e.g., the D locus controlling potato tuber skin color, F locus regulating flower color, and Pf locus influencing flesh pigmentation, all encode TFs. We prioritized TFs within the candidate interval and flanking regions, identifying 4 TFs highly expressed in spotted seeds (Figure 5B,C). Given the central role of MYB TFs in anthocyanin regulation, an additional non-differentially expressed MYB family member was included, resulting in 5 candidate genes: DM8C10G19550, DM8C10G19560, DM8C10G21130, DM8C10G21200, and DM8C10G21210 (Table 4, Figure 5E). Among them, two harbor the AP2 conserved domain and belong to the AP2/ERF family of transcription factors. Three other candidates contain the MYB conserved domain and are members of the MYB transcription factor family. Additionally, the f3′5′h gene (the P gene) possesses the cytochrome P450 conserved domain and is classified under the cytochrome P450 family of transcription factors (Figure 5E).

Table 4.

Detailed information of the five candidate genes.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) validated the expression patterns of these 5 candidates and the P gene (DM8C11G21030) (Figure 5D). The results obtained from qRT-PCR and RNA-seq were compared, and expression trends were consistent for all 6 genes in both analyses; Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was 0.8470 (Figure S1). All 6 genes exhibited significantly higher expression in spotted seeds, indicating their potential roles in embryonic spot formation during potato seed development.

The 2037 DEGs were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses (Table S4). For GO enrichment (Figure S2), in biological process (BP) categories (Figure S2C), DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways including response to chitin, carbohydrate metabolic process, and flavonoid metabolic process. KEGG enrichment analysis identified the top 20 enriched metabolic pathways (Figure S2D), including biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, steroid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis. The “flavonoid biosynthesis” pathway, a direct precursor of anthocyanin synthesis, further validated the functional relevance of flavonoid-related genes highlighted in GO enrichment, reinforcing its central role in embryonic spot pigmentation.

4. Discussion

The haploid induction system has been successfully applied in germplasm innovation and breeding practice for potato [13]. All reported haploid inducers, such as “IVP101”, “IVP35”, and “PL4”, share a common morphological marker—embryonic spots in seeds—which provides a visual criterion for rapidly identifying progeny with reduced chromosome numbers. Anthocyanin accumulation in potato is tightly regulated by transcription factors [38], with MYB family members acting as core regulators. The D locus, which controls tuber skin color, encodes the R2R3-MYB transcription factor StAN2, which drives anthocyanin deposition in the tuber epidermis [18]. Of particular note, the present study simultaneously employed this F2 population for QTL mapping of the tuber skin color trait, identifying a total of 13 loci. Intriguingly, two major-effect loci, qSC-10-3 and qSC-11-2, with phenotypic contribution rates exceeding 21%, were detected. Coincidentally, the intervals of these two loci, respectively, harbored the previously the genetically transformed/validated D and P locus (Table S5). This result further validates the reliability of the genetic map utilized and the QTL mapping outcomes. For flower pigmentation, the F locus is regulated by another R2R3-MYB transcription factor, StFlAN2 [20]. In tuber flesh, the Pf locus contains tandem R2R3-MYB genes (StMYB200/210) that form a synergistic regulatory network with StbHLH1 to modulate anthocyanin synthesis [19]. Additionally, the P locus encodes flavonoid-3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), a structural gene catalyzing purple anthocyanin formation via specific hydroxylation reactions [15]. In this study, embryonic spot formation appears to be part of a conserved transcription factor-mediated pigmentation network. Genetic analyses revealed that the embryonic spot trait is cooperatively controlled by two loci: a major-effect locus mapped to a 53.16–53.55 Mb interval on chromosome 10, which overlaps with the previously reported B locus [27], confirming its central role in regulating embryonic spot development. Furthermore, the qS-11-1 locus colocalized with the known P gene (DM8C11G21030; 41,514,416–41,520,754 bp), providing additional evidence supporting the two-locus regulatory model for the embryonic spot trait.

To dissect the genetic basis of embryo spots, this study employed a multi-step strategy involving BSA-seq-based initial mapping with the F1 population, quantitative trait locus (QTL) fine mapping using the F2 population, and candidate gene screening via transcriptome sequencing. This integrated strategy offers significant advantages over single methods. BSA-seq (bulked segregant analysis combined with whole-genome sequencing) is a powerful tool for preliminary mapping of major-effect loci [39]. In this study, two pools were constructed using 23 spotted and 23 non-spotted F1 individuals, and BSA-seq analysis identified a major associated region on chromosome 10 (49.96–54.31 Mb; Figure 2). The advantage of BSA-seq lies in its elimination of the need for large populations or high-density markers during the initial stage, thereby reducing both cost and time. By leveraging allelic frequency differences between the two pools, this study effectively excluded approximately 95% of the genome, focusing subsequent research efforts on an interval of approximately 4.3 Mb.

Generally, increasing marker density is an effective approach to improve QTL mapping resolution [40]. In this study, a high-density genetic map constructed via whole-genome resequencing was utilized, and QTL mapping was performed using inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM). The target locus on chromosome 10 was narrowed down to 384.6 Kb (53.16–53.55 Mb), designated as qSP-10-1, with a phenotypic variance explained (PVE) of up to 23.85% (Table 4). The use of an F2 population derived from F1 selfing (which accumulates more recombination events than the F1) improved mapping resolution, with the 384.6 kb interval representing an 11-fold reduction compared to the BSA-seq result, demonstrating the precision of high-density linkage mapping. Additionally, qSP-10-1 overlapped with the previously reported B locus [27], while the qS-11-1 locus coincided with the known P gene (DM8C11G21030, 41,514,416–41,520,754 bp), collectively validating the reliability of the mapping results.

Differential expression analysis is an effective strategy for investigating genes associated with specific traits [41]. To further narrow down the range of candidate genes, this study subsequently performed transcriptome sequencing on F1 seeds with and without embryo spots, identifying 2037 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Focusing on DEGs within the 384.6 Kb interval, five transcription factors (including three MYB family members) were selected and validated by qRT-PCR (Figure 5), with expression patterns consistent with RNA-seq data. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs highlighted flavonoid biosynthesis and secondary metabolic pathways (Figure S1), which are directly associated with anthocyanin synthesis. This functional context supports the biological plausibility of the candidates.

By integrating physical mapping (QTL), expression divergence (RNA-seq), and conserved transcription factor functions (homology to D, F, and Pf loci), we narrowed the candidate pool from hundreds of interval genes to five high-confidence transcription factors. In another study, Wang et al. [28] performed BSA-seq analysis using an F2 segregating population and mapped this locus to a 6.78 Mb interval (chr10: 52.37–59.15 Mb). Within this interval, they identified 26 transcription factors and further predicted DM8C10G21210 as a candidate gene at this locus contributing to embryo spot formation based on gene expression profile. In the present study, we combined BSA-seq of the F1 population and high-density genetic map of the F2 population for QTL mapping, narrowing the candidate interval of qSP-10-1 to 384.6 Kb. Within this interval and its flanking sequences, 18 transcription factors were screened (Figure 5C). Furthermore, based on the co-expression relationship between the target gene and F3′5′H (the P gene), we identified the final 5 most promising candidate genes using transcriptome sequencing analysis and qRT-PCR (Figure 5D). Among them, DM8C10G21210 encodes an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, which exhibited higher expression levels in spotted samples. Interestingly, this gene is identical to the candidate gene predicted by Wang et al. [28]. DM8C10G19550 and DM8C10G19560, belonging to the DREB2A-type transcription factor family, exhibited significantly higher mean expression levels in spotted samples compared to non-spotted counterparts, suggesting their potential association with embryonic spot development through transcriptional regulation. DM8C10G21130, an MYB family member (MYB113), showed a marked increase in expression from 0.362 (non-spotted) to 2.831 (spotted) and has been previously reported to regulate purple pigment accumulation in tuber skin [42], indicating potential pleiotropic functionality as an embryonic spot-controlling allele through allelic variation. Additionally, DM8C10G21200, encoding the MYBA1 transcription factor, displayed upregulated expression in spotted seeds, further supporting its role in the pigmentation regulatory network. Collectively, these transcription factors, characterized by their differential expression patterns and functional homology to known pigmentation regulators, represent promising candidates for deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying embryonic spot formation in potato. Although current evidence suggests their involvement in regulating embryonic spot formation, further functional validation of these genes is essential to elucidate their specific mechanisms and evaluate their potential utility in screening doubled haploid materials to accelerate potato inbred line development.

5. Conclusions

This study integrated BSA-seq, QTL mapping, and transcriptome sequencing to dissect the genetic regulatory mechanisms underlying embryo spot formation in potato. BSA-seq using the F1 population initially mapped the embryo spot-related locus to a 49.96–54.31 Mb interval on chromosome 10. QTL analysis via the F2 population identified 4 QTLs (on chromosomes 2, 5, 10, and 11), with qSP10-1 on chromosome 10 (23.85% phenotypic variance explained) and qSP11-1 on chromosome 11 (18.23% phenotypic variance explained) as major QTLs. Notably, qSP11-1 overlapped with the reported P locus encoding flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), while qSP10-1 was consistent with the BSA-seq result. Integrating mapping results fine-mapped the target gene to a 384.6 Kb terminal interval on chromosome 10, and combined with transcriptome sequencing, 5 differentially expressed candidate genes were screened. This study provides critical candidate gene resources for dissecting the molecular mechanism of embryo spots and lays an important theoretical foundation for optimizing the screening efficiency of potato doubled haploids using embryo spots and accelerating breeding programs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121483/s1, Table S1: Primers used for qRT-PCR; Table S2: Summary of reads mapping statistics; Table S3: Expression levels of all genes, gene annotation information, and differential gene analysis; Table S4: Enrichment results of the 2037 spotted_vs_non-spotted DEGs; Table S5: QTL mapping results of potato skin color. Figure S1. Comparison of the expression trends of the 6 selected genes using RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR; Figure S2. Transcriptome GO and KEGG enrichment analyses (Top 20). (A–C) GO terms (sorted by minimum q-value) for (A) cellular component (CC), (B) molecular function (MF), and (C) biological process (BP) categories. (D) KEGG pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., J.L. and J.Y.; methodology, J.Y. and C.L.; software, J.M.; validation, M.Y.; formal analysis, J.M. and M.Y.; investigation, J.M., M.Y., N.L., J.W. (Jiaji Wang), J.W. (Jiangqing Wang), T.Z., Z.H. and Z.L.; resources, J.Y. and J.L.; data curation, J.M., M.Y. and N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M., M.Y. and N.L.; writing—review and editing, J.Y. and C.L.; visualization, J.M. and J.Y.; supervision, C.L. and J.L.; project administration, J.Y. and C.L.; funding acquisition, J.Y. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yunnan Fundamental Research Project (No. 202301AT070072 of Jing Yang; No. 202301AS070010 of Canhui Li) and Yunnan Normal University Doctoral Research Startup Fund of Jing Yang.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSA-seq | Bulked segregant analysis-sequencing |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

| SP | Spotted |

| NS | Nonspotted |

| ED | Euclidean Distance |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| ICIM | Inclusive Composite Interval Mapping |

| QTLs | Quantitative trait locis |

| PVE | Phenotypic variance |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| BP | Biological process |

References

- Wang, F.; Xia, Z.; Zou, M.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Bao, Y.; Sun, H.; et al. The autotetraploid potato genome provides insights into highly heterozygous species. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.E.; Ramsay, G. Utilisation of the commonwealth potato collection in potato breeding. Euphytica 2005, 146, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, D.M.; Núñez, J.; Trujillo, G.; Herrera Mdel, R.; Guzmán, F.; Ghislain, M. Extensive simple sequence repeat genotyping of potato landraces supports a major reevaluation of their gene pool structure and classification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19398–19403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethke, P.C.; Halterman, D.A.; Jansky, S. Are we getting better at using wild potato species in light of new tools? Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 1241–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, D.M.; Ghislain, M.; Simon, R.; Jansky, S.H.; Gavrilenko, T. Systematics, Diversity, Genetics, and Evolution of Wild and Cultivated Potatoes. Bot. Rev. 2014, 80, 283–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G.M.; Braz, G.T.; Conway, M.; Crisovan, E.; Hamilton, J.P.; Laimbeer, F.P.E.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.; Newton, L.; Douches, D.S.; Jiang, J.; et al. Genome-wide Inference of Somatic Translocation Events During Potato Dihaploid Production. Plant Genome 2019, 12, 180079. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, C. The historical role of species from the Solanaceae plant family in genetic research. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 2281–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, M.; Chang, Y.; Han, Z.; Du, L.; Lin, Z.; Wang, K.; Ye, X. Development of a haploid inducer by editing HvMTL in barley. J. Genet. Genom. 2023, 50, 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Delzer, B.; Liang, D.; Szwerdszarf, D.; Rodriguez, I.; Mardones, G.; Elumalai, S.; Johnson, F.; Nalapalli, S.; Egger, R.; Burch, E.; et al. Elite, transformable haploid inducers in maize. Crop J. 2024, 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutten, R.C.B.; Scholberg, E.J.M.M.; Huigen, D.J.; Hermsen, J.G.T.; Jacobsen, E. Analysis of dihaploid induction and production ability and seed parent x pollinator interaction in potato. Euphytica 1993, 72, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloquin, S.J.; Gabert, A.C.; Rodomiro, O.J.A.O.B. Nature of ‘Pollinator’ Effect in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Haploid Production. Ann. Bot. 1996, 77, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breukelen, E.W.M.; Ramanna, M.S.; Hermsen, J.G.T. Parthenogenetic monohaploids (2n=x=12) from Solanum tuberosum L. and S. verrrucosum Schlechtd. and the production of homozygous potato diploids. Euphytica 1977, 26, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoez, B.; Santayana, M.; Aponte, M.; Henry, I.M.; Comai, L.; Eyzaguirre, R.; Lindqvist-Kreuze, H.; Bonierbale, M. PL-4 (CIP596131.4): An Improved Potato Haploid Inducer. Am. J. Potato Res. 2021, 98, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, J.G.T.; Verdenius, J.J.E. Selection from Solanum tuberosum group phureja of genotypes combining high-frequency haploid induction with homozygosity for embryo-spot. Euphytica 1973, 22, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.S.; Griffiths, H.M.; De Jong, D.M.; Cheng, S.; Bodis, M.; De Jong, W.S. The potato P locus codes for flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, W.D.D.; De Jong, D.M.; De Jong, H.; Kalazich, J.; Bodis, M. An allele of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase associated with the ability to produce red anthocyanin pigments in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 107, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; De Jong, D.; Griffiths, H.; Halitschke, R.; De Jong, W. The potato R locus codes for dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.S.; Griffiths, H.M.; De Jong, D.M.; Cheng, S.; Bodis, M.; Kim, T.S.; De Jong, W.S. The potato developer (D) locus encodes an R2R3 MYB transcription factor that regulates expression of multiple anthocyanin structural genes in tuber skin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 120, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhai, Z.; Pu, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, D.; et al. Two tandem R2R3 MYB transcription factor genes cooperatively regulate anthocyanin accumulation in potato tuber flesh. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimbeer, F.P.E.; Bargmann, B.O.R.; Holt, S.H.; Pratt, T.; Peterson, B.; Doulis, A.G.; Buell, C.R.; Veilleux, R.E. Characterization of the F Locus Responsible for Floral Anthocyanin Production in Potato. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 3871–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, H.D. Inheritance of anthocyanin pigmentation in the cultivated potato: A critical review. Am. Potato J. 1991, 68, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, K.S.; Long, D.H. The inheritance of colour in diploid potatoes. J. Genet. 1955, 53, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, E.S.; Long, D.H. The inheritance oe colour in diploid potatoes II. A three-factor linkage group. J. Genet. 1956, 54, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, H.J.; Jacobs, J.M.; van Dijk, J.; Stiekema, W.J.; Jacobsen, E. Identification and mapping of three flower colour loci of potato (S. tuberosum L.) by RFLP analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993, 86, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, H.; Jacobs, J.; van den Berg, P.; Stiekema, W.J.; Heredity, E.J. The inheritance of anthocyanin pigmentation in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and mapping of tuber skin colour loci using RFLPs. Heredity 1994, 73, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endelman, J.B.; Jansky, S.H. Genetic mapping with an inbred line-derived F2 population in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonsungsan, P.; Nganga, M.L.; Lieberman, M.C.; Amundson, K.R.; Stewart, V.; Plaimas, K.; Comai, L.; Henry, I.M. A k-mer-based bulked segregant analysis approach to map seed traits in unphased heterozygous potato genomes. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2024, 14, jkae035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Cheng, L.; Pan, J.; Ma, L.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chang, S.; Yuan, P. A 6.49-Mb inversion associated with the purple embryo spot trait in potato. Abiotech 2025, 6, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Dong, D.; Huang, S.; et al. The gap-free potato genome assembly reveals large tandem gene clusters of agronomical importance in highly repeated genomic regions. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.T.; Demarest, B.L.; Bisgrove, B.W.; Gorsi, B.; Su, Y.C.; Yost, H.J. MMAPPR: Mutation mapping analysis pipeline for pooled RNA-seq. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yao, C.; Miao, J.; Li, N.; Ji, F.; Hu, D.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, K.; Chen, A.; et al. Construction of a High-Density Genetic Map and QTL Mapping Analysis for Yield, Tuber Shape, and Eye Number in Diploid Potato. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, J.K. QTL IciMapping: Integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015, 3, 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Riveros-Loaiza, L.M.; Benhur-Cardona, N.; Lopez-Kleine, L.; Soto-Sedano, J.C.; Pinzón, A.M.; Mosquera-Vásquez, T.; Roda, F. Uncovering anthocyanin diversity in potato landraces (Solanum tuberosum L. Phureja) using RNA-seq. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeberger, K. Using next-generation sequencing to isolate mutant genes from forward genetic screens. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H. Fine-Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Body Weight and Abdominal Fat Traits: Effects of Marker Density and Sample Size. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, K.; Li, D.; Luo, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Yang, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Identification of stable QTLs and candidate genes involved in anaerobic germination tolerance in rice via high-density genetic mapping and RNA-Seq. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhao, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, J.; Song, B. StWRKY13 promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis in potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021, 49, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).