Abstract

Pepper (Capsicum annuum), a widely cultivated vegetable of significant economic importance globally, is frequently subjected to attacks from pathogens such as Ralstonia solanacearum, as well as high-temperature stress. However, the mechanisms by which pepper combats these stresses remain poorly understood. Herein, we reported that the expression of the leucine-rich repeat protein CaLRR13, which lacks a nucleotide-binding site (NBS), kinase domains, and a transmembrane region, was transcriptionally activated by both R. solanacearum inoculation and high-temperature stress. Through transient overexpression in the epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, we found that CaLRR13 localized in both the cytoplasm and the nuclei. Reducing the expression of CaLRR13 via virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) increased the sensitivity of pepper to R. solanacearum infection and high-temperature exposure, accompanied by reduced expression of immunity- and thermotolerance-related genes, including CaWRKY40, CaPR1, CaNPR1, CaDEF1, and CaHSP24. In contrast, transient overexpression of CaLRR13 in pepper leaves induced a like-hypersensitive response (HR) and enhanced the expression of the aforementioned immunity- and thermotolerance-related genes. Thus, we conclude that CaLRR13 plays a positive role in pepper immunity against R. solanacearum and thermotolerance, providing a new perspective on the crosstalk and management of plant responses to these two stresses.

1. Introduction

As sessile organisms, plants are inevitably exposed to various biotic and abiotic stresses throughout their lives. To survive, plants have evolved highly efficient and complex defense systems to perceive these stresses and initiate appropriate defense responses through a series of signal transduction and transcriptional regulation processes [1]. Plant immune responses to pathogens involve two interconnected layers: pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI). PTI is activated when pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the cell membrane recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs); although PTI can inhibit the expansion of pathogens, it is not sufficient for plant disease resistance. On the other hand, ETI is activated by intracellular NLRs (nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat proteins) upon directly or indirectly perceiving pathogen effectors and is crucial for incompatible plant–pathogen interactions and plant disease resistance [1,2,3]. This resistance, serving as the functional outcome of successful immunity, represents the heritable trait of limiting pathogen establishment and damage [4,5]. Despite their distinct nature, PTI and ETI share overlapping signaling components [6] and interact with each other in a “zig-zag-zig” model [7,8,9]. Bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum is a devastating soil-borne disease in solanaceous crops like pepper [8,9]. R. solanacearum infects plants through wounds in lateral roots or roots, colonizes vascular bundles, and blocks vascular bundles by secreting exopolysaccharides, thus preventing the transmission of water to the aboveground parts of the plant. R. solanacearum can cause disease in up to 250 plant species [10,11]. Research on identifying R. solanacearum PAMPs or effectors holds significant potential for examining plant immunity and breeding varieties with high levels of disease resistance. However, PTI-specific mechanisms in response to R. solanacearum remain poorly explored.

Plant immune receptors involved in pathogen recognition are broadly categorized into two groups based on structural features and subcellular localization: intracellular nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat proteins (NLRs) [12], and cell surface-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs primarily comprise two protein families: receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (RLPs) [7]. Among various internal repeat sequences in plant proteins, the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motif stands out as one of the most prevalent and well-characterized structural elements [13,14]. In PRR-mediated immunity, the extracellular LRR domain directly recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to activate pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [6,9]. Conversely, in NLR proteins, the C-terminal LRR domain [15] facilitates effector recognition [13,14,16,17] and regulates interactions between NLRs and other NBS-LRR-type resistance proteins, thereby coordinating effector-triggered immunity (ETI) signaling [18,19,20,21].

Beyond their immunological roles, LRR-containing proteins critically regulate plant growth and development, including cell division/expansion, reproductive processes, self-incompatibility, and abiotic stress responses [22,23,24,25,26]. For instance, the LRR receptor kinases BRI1 and BAK1 serve as core components in brassinosteroid (BR) signaling [27], highlighting the dual functionality of LRR domains in both defense and developmental pathways. Notably, LRR domains typically require synergistic interactions with other functional domains (kinase, transmembrane, or nucleotide-binding domains) to execute their biological roles [28]. A classic example is the FLS2 receptor in tomato, rice, and tobacco: its extracellular LRR recognizes bacterial flagellin, while the intracellular kinase domain activates downstream MAPK cascades, triggering ROS production, callose deposition, and defense gene expression to enhance disease resistance [29,30]. However, LRR-only proteins lacking these auxiliary domains remain poorly characterized in plant immunity systems.

Recent studies have identified a novel class of LRR proteins in plants that lack canonical functional domains such as kinase or nucleotide-binding domains (NBS) but possess transmembrane structures analogous to RLKs [31]. Termed extracellular LRR (eLRR) proteins due to their predominant plasma membrane localization [32,33], these proteins regulate immune responses through interaction networks. For instance, rice OsLRR1 interacts with OsHIR1 via the endosomal pathway to potentiate hypersensitive response (HR)-mediated pathogen containment [33,34]. In pepper, CaLRR1 was found to enhance immunity by interacting with PR10 [35], yet it suppresses disease resistance upon forming complexes with HIR1 or PR4b [36,37,38]. Another pepper eLRR protein, CaLRR51, positively regulates resistance to bacterial wilt [39]. Arabidopsis has been found to possess 44 LRR-only proteins. Of these, LRRop-1 functions by modulating abscisic acid (ABA) content in seeds to facilitate germination, thereby contributing to the ABA-mediated abiotic stress response [40]. Intriguingly, invertebrate genomes (amphioxus and sea urchin) encode numerous LRR-only proteins (over 500 in amphioxus and ~300 in sea urchin), which function as novel pattern recognition receptors in innate immunity [41,42,43,44]. However, no LRR-only proteins have been reported in pepper to date, and the molecular mechanisms underlying LRR-only mediated immune regulation remain poorly characterized.

Ralstonia solanacearum is one of the most devastating soil-borne bacterial pathogens infecting solanaceous plants, often leading to substantial yield losses. Pepper (Capsicum annuum), a globally significant solanaceous vegetable crop, is severely threatened by bacterial wilt caused by R. solanacearum. The virulence of R. solanacearum is multifactorial, and its type III secretion system (T3SS) is essential for pathogenicity; mutants defective in T3SS completely disable the pathogen from causing disease in the host plant [45]. Consequently, the recognition of T3SS-associated pathogen molecules (such as effectors or conserved structural components) by plant immune receptors represents a key molecular event in activating plant immunity and has become an important strategy in disease-resistant breeding. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in several systems: Field trials in Florida showed that the introducing of Arabidopsis EFR receptor gene into tomato significantly reduced bacterial wilt incidence [46]. The tomato SICORE receptor recognizes the CSP22Rsol peptide from R. solanacearum to activate immunity [47]. Furthermore, the nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptor pair RRS1/RPS4 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to R. solanacearum by specifically recognizing its T3SS effector, PopP2 [48]. However, despite these advances in other systems, the molecular mechanisms underlying pepper resistance to bacterial wilt, particularly the pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) response against R. solanacearum infection, remain poorly understood.

Consequently, our strategic approach is to enhance pepper resistance to bacterial wilt by identifying and utilizing similar receptor genes within the pepper genome. To this end, we interrogated a publicly available transcriptome dataset [49] from pepper plants subjected to the combined challenge of R. solanacearum infection under high-temperature and high-humidity conditions, and found that an LRR-only protein, CaLRR13 (Capana03g000525), was upregulated by R. solanacerum infection under this condition, and we further found that CaLRR13 is significantly induced by not only R. solanacearum inoculation but also high-temperature stress treatment, elucidating its possible involvement in pepper’s defense response to these two stresses. This speculation was further confirmed in the present study by its functional characterization; the results showed that CaLRR13 acts positively in pepper’s immune response to R. solanacearum and thermotolerance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Silico Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of CaLRR13

Gene identification and domain prediction: The CaLRR13 gene (Capana03g000525) was identified as a significantly upregulated transcript from a publicly available RNA-seq dataset of pepper plants challenged with Ralstonia solanacearum [49]. Its coding sequence (accession: XP_016562949.1) and corresponding amino acid sequence were retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 3 March 2019) using BLAST (online service) analysis. The protein domain and transmembrane domain architecture of CaLRR13 were predicted using NCBI’s Conserved Domain Database (CDD) [50] and the TMHMM Server v.2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/ accessed on 10 March 2019) [51], respectively.

Phylogenetic and sequence homology analysis: Full-length amino acid sequences of homology to CaLRR13 from Capsicum annuum, Solanum tuberosum, Solanum lycopersicum, Nicotiana tabacum, Coffea canephora, Vitis vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa were retrieved from the NCBI database. Multiple sequence alignment of the retrieved homologous amino acid sequences was performed using DNAMAN 8 software [52]. The sequence homology was quantified as percentage identity based on the alignment results.

Promoter cis-acting element analysis: A 1500 bp genomic DNA sequence upstream of the CaLRR13 translational start site (ATG) was defined as the promoter region. The identification of putative cis-acting regulatory elements was conducted using the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ accessed on 10 March 2019) [53].

2.2. Plant Materials and Cultivation

The plant materials, including the pepper inbred lines “HN42” (moderately resistant to Ralstonia solanacearum) [49] and “Zunla” [54] (moderately resistant to Ralstonia solanacearum), as well as Nicotiana benthamiana (for the subcellular localization analysis in this study), were provided by the pepper breeding group at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Fuzhou, Fujian province, China). Seeds were soaked, germinated, and sown in a 2:1 (v/v) potting mix: perlite substrate (80% moisture). Seedlings with fully expanded cotyledons were transferred to black plug trays (7 × 10 × 10 cm) and grown in a climate-controlled greenhouse (25 °C, 70% relative humidity, 60–70 mmol photons m−2 s−1, 16/8 h light/dark cycle).

2.3. High-Temperature Treatment of Pepper Plants

High-temperature treatment was conducted on eight-leaf-stage pepper plants by maintaining them at 42 °C with 80% relative humidity, whereas control plants were kept at 28 °C under identical humidity conditions.

2.4. Pathogens and R. solanacearum Inoculation

Eight-leaf-stage seedlings of pepper (Capsicum annuum) cultivar “HN42” were inoculated with Ralstonia solanacearum strain FJC100301 (a virulent strain isolated from pepper). Bacterial colonies were cultured in 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride medium, and the cultures were incubated in a Crystal IS-RDV1 incubator shaker at 28 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h, and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 to OD600 = 0.6. For leaf infiltration, 50 μL of bacterial suspension was injected into each site using a needle-free syringe. For root inoculation, 10 mL of bacterial suspension was applied through soil drenching per plant [55,56].

2.5. Vector Constructs

Vector assembly was performed using the Gateway® cloning system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). This process involves two distinct site-specific recombination reactions: the BP reaction, which is used to clone a PCR product into an entry vector, and the LR reaction, which transfers the insert from the entry vector into a destination vector.

To construct vectors for transient overexpression or subcellular localization assays, the full-length open reading frame of CaLRR13 (without a termination codon) was amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table S1). The 25 μL PCR reaction mixture contained 1× PCR buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.2 μM of each primer, 100 ng of cDNA template, and 1 U TaKaRa Taq DNA polymerase. Amplification was performed under the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 2 min; final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. The resulting PCR product was first cloned into the entry vector pDONR207 via a BP reaction and subsequently transferred into the destination vectors pEarlyGate201 or pEarlyGate103 via an LR reaction. To construct the vectors for the virus-induced gene silencing assay, the specific gene fragment within the coding sequence (CDS) of CaLRR13 was amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table S1). The fragment was then cloned into the entry vector pDONR207 through a BP reaction, and then transferred into the pTRV2 vector through an LR reaction.

2.6. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Assay

The Tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-mediated gene silencing system was employed to knock down CaLRR13. This system utilizes two vectors, pTRV1 and pTRV2. The specific 3′UTRs of CaLRR13 and PDS (phytoene desaturase, serving as the positive control) were cloned into the pTRV2 vector via Gateway® technology, generating recombinant constructs pTRV2:CaLRR13 and pTRV2:PDS (carrying the CaLRR13 and PDS genes, respectively), with the empty vector pTRV2:00 serving as a negative control. The recombinant plasmids (pTRV2:CaLRR13, pTRV2:PDS, pTRV2:00, and pTRV1) were individually transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 [56,57]. After culturing, bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation (2660× g, 28 °C, 10 min) and resuspended in induction buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2) to OD600 = 0.8. The pTRV1-containing Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspension was mixed 1:1 (v/v) with suspensions carrying pTRV2:CaLRR13, pTRV2:PDS, or pTRV2:00, followed by co-incubation at 28 °C with gentle shaking (60 rpm) for 3 h. The mixtures were then infiltrated into the cotyledons of 3- to 4-leaf-stage pepper seedlings. Inoculated plants were kept under dark conditions at 16 °C and 80% relative humidity for 56 h before transfer to standard growth conditions. Approximately 30 days post-inoculation, leaf whitening in the pTRV2:PDS-positive control plants confirmed the successful establishment of the TRV-mediated gene silencing system, enabling subsequent experimental analysis [49,55].

2.7. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression of CaLRR13 in Pepper Leaves

The Freeze–Thaw Method was used to transform the plasmids pEarlyGate201 and pEarlyGate103 (containing CaLRR13 without a stop codon) into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Following successful transformation, individual colonies were verified by PCR and subsequently cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium supplemented with gentamicin (50 μg/mL), kanamycin (50 μg/mL), and rifampicin (50 μg/mL) under standard growth conditions (28 °C, 200 rpm agitation for 24 h). The bacterial cultures were centrifuged (2660× g, 28 °C, 10 min), and the supernatant was discarded. The pellets were resuspended in induction suspension buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 μM Acetosyringone, pH 5.4) and adjusted to an OD600 = 0.8. After incubation in a shaking incubator (28 °C, 100 rpm) for 2 h, the bacterial suspensions were infiltrated into target leaf sites using a sterile disposable syringe.

2.8. The Subcellular Localization of CaLRR13

CaLRR13 (without a stop codon) was cloned into the pEarlyGate103 vector using Gateway® technology. The Agrobacterium-mediated transient overexpression assay was performed by infiltrating GV3101 cells harboring 35S:CaLRR13-GFP or 35S:GFP (as a control) into entire leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana or pepper plants using a needle-free sterile syringe. At 48 h post-infiltration (hpi), GFP fluorescence signals in the leaf tissues were monitored using a Leica confocal laser scanning microscope (bars = 50 μm).

2.9. Plant Total Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Leaves from transiently overexpressed pepper plants were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder. The powder was transferred to pre-chilled 2 mL tubes, and total proteins were extracted using ice-cold buffer [10% glycerol, 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, 10 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 2% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone]. The homogenate was vortexed, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged (15,320× g, 15 min, 4 °C) to collect the supernatant. For immunoprecipitation, the protein lysate was incubated with anti-GFP agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4 °C. Beads were magnetically captured and washed three times with TBST (Tris-buffered saline +0.05% Tween-20), and bound proteins were eluted in Laemmli buffer (95 °C, 5 min). Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST. Blots were probed with HRP-conjugated anti-GFP antibody (1:5000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), washed, and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) on a LAS4000 imager.

2.10. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Assay

Total RNA was isolated from pepper leaf tissues using TRIpure Reagent (Aidlab, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol, with genomic DNA removed by DNase I treatment. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using HiScript III RT SuperMix (+gDNA wiper, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a BIO-RAD CFX96 system (USA) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan), using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S2). Four independent biological replicates of each treatment were performed. Data were analyzed by the Livak method [55] and expressed as a normalized relative expression level (2−ΔΔCT) of the respective genes [58]. The relative transcript level of each sample was normalized by CaACTIN (GQ339766).

2.11. Colony-Forming Units (CFUs) and Disease Index Determination

Pepper leaves infected with Ralstonia solanacearum were sampled at 24 and 48 h post-inoculation (hpi), surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol, and aseptically punched with a sterile corn borer (6 discs per leaf). Discs were homogenized in 500 μL sterile water within 2 mL tubes, rinsed with an additional 500 μL sterile water, and serially diluted (10−3, 10−4, and 10−5). Aliquots (400 μL) of each dilution were spread on 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride medium, air-dried, sealed, and incubated at 28 °C for 2–3 days. CFUs were counted to quantify bacterial load. Concurrently, disease severity was scored (0: healthy; 4: total wilting) to calculate disease indices. Four biological replicates were analyzed for statistical validation.

2.12. Measurement of Ion Leakage Displayed by Conductivity

Ion leakage was measured as described previously [57] using a Mettler Toledo 326 conductivity meter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA). Pepper plants (6–8 leaf stage) were transiently overexpressed via Agrobacterium GV3101-mediated infiltration with 35S::GFP (as a control) or 35S::CaLRR13-GFP. Leaf discs (6 mm diameter) were collected at 24 and 48 h post-infiltration (hpi) and surface-washed with double-distilled water (ddH2O), and six uniform discs per leaf were incubated in 10 mL ddH2O within sealed 50 mL tubes for 1 h at 28 °C. Conductivity was measured to quantify ion leakage, reflecting membrane integrity. Four biological replicates were analyzed per treatment, and data were normalized to initial conductivity values.

2.13. Histochemical Staining Assay

Trypan blue staining was performed to visualize HR-like cell death in pepper leaves, following established protocols [59]. Briefly, leaf tissues were boiled in lactophenol–trypan blue solution (10% lactic acid, 10% phenol, 10% glycerol, 0.02% trypan blue) for 1 min, destained in chloral hydrate (2.5 g/mL) for 48 h, and photographed to document necrotic lesions. For H2O2 detection, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining was conducted as described [39]. Leaves were vacuum-infiltrated with DAB solution (1 mg/mL, pH 3.8) for 8 h, cleared in 95% ethanol at 65 °C for 2 h, and photographed. Brown polymerization products indicated H2O2 accumulation.

2.14. Imaging-PAM

A MINI-version of the Imaging-PAM (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) was used to measure the Fv/Fm and △F/Fm’ of CaLRR13-silenced pepper leaves. Plants were subjected to 15 min dark adaptation and then directly put into the instrument for testing, according to the methods of Li [60].

Eight-leaf-stage pepper plants subjected to virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of CaLRR13 and corresponding controls were exposed to combined high-temperature stress for 48 h. Following stress treatment, plants were dark-adapted for 15 min to fully open PSII reaction centers. Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, including Fv/Fm and ΔF/Fm’, were measured using a portable Imaging-PAM MINI system (Heinz Walz GmbH, Germany) according to established protocols [60].

2.15. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data obtained from the experiments were subjected to statistical analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) of four independent biological replicates. Significance analysis was performed using Fisher’s Protected least-significant-difference (LSD) test at significance levels of p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 in DPS software (version 9.5). Differences between means were considered statistically significant when p < 0.01 or p < 0.05, and these are denoted by different uppercase or lowercase letters in the figures. All figures were generated using SigmaPlot software (version 12.5).

3. Results

3.1. The Sequence Analysis of CaLRR13

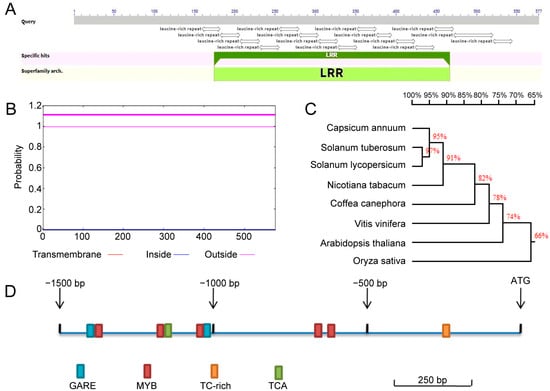

In the analysis of publicly available RNA-seq data from pepper plants challenged with R. solanacesrum infection [49], a significantly upregulated leucine-rich repeat (LRR) gene (Capana03g000525) was identified and designated CaLRR13 (XP_016562949.1). BLAST analysis from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 10 March 2019) database revealed that CaLRR13 has a coding sequence (CDS) of 1734bp, encoding a protein of 577 amino acids. The protein structure contains 17 leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motifs but lacks a signal peptide (SP) and kinase domain (Figure 1A). TMHMM software was employed to predict transmembrane domains, and the results indicated that the protein lacks transmembrane structures (Figure 1B). Through amino acid sequence homology alignment analysis, CaLRR13 was found to share high homology with Solanaceae plants such as Solanum tuberosum, Solanum lycopersicum, and Nicotiana tabacum. It also exhibited significant sequence homology with non-Solanaceae plants, including Coffea canephora, Vitis vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa, with homology levels of 97%, 95%, 91%, 82%, 78%, 74%, and 66%, respectively (Figure 1C). To further investigate the regulatory mechanisms of CaLRR13, cis-acting elements in the promoter region (1500 bp upstream) were predicted using the PlantCARE database. The analysis revealed the presence of multiple cis-acting elements associated with plant disease resistance and stress responses, including gibberellin-responsive elements (GARE), MYB-binding sites, TC-rich repeats (defense and stress-responsive elements), and salicylic acid-responsive elements (TCA) (Figure 1D). These findings suggest that CaLRR13 may play a role in the immune defense signaling pathways of pepper.

Figure 1.

The sequence of CaLRR13 relative to its orthologs in other plant species. (A) The domain(s) of CaLRR13 displayed using the BLAST results from the NCBI website. (B) Analysis of the transmembrane domain in the amino acid sequence of CaLRR13. (C) Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of CaLRR13 with its orthologs from other plant species, including Solanum tuberosum, Solanum lycopersicoides, Nicotiana tomentosiforms, Coffeacanephora, Vitis vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa (performed using DNAMAN8). (D) Distribution of cis elements in the CaLRR13 promoter.

3.2. Subcellular Localization and Transcriptional Profiling of CaLRR13 Under Ralstonia solanacearum Infection or High-Temperature Stress

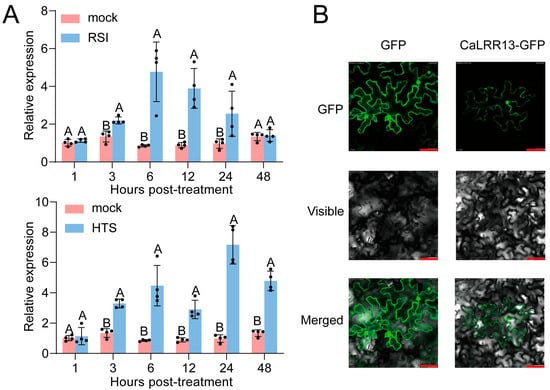

To further analyze the potential involvement of CaLRR13 in pepper’s response to R. solanacearum infection or heat stress, bacterial inoculation or high-temperature treatment was applied to pepper plants. Leaf samples were collected at various time points for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of CaLRR13 transcriptional expression levels. The results demonstrated that CaLRR13 expression in pepper leaves gradually increased during 1–12 h post-R. solanacearum infection, followed by attenuation at 24 h. Under heat stress, CaLRR13 expression showed a progressive upregulation, peaking at 48 h before exhibiting a slight decline (Figure 2A). These findings indicate that CaLRR13 expression was induced by both R. solanacearum infection and heat stress, suggesting its potential functional role in these stress responses. Additionally, to gain insights into the potential mechanism by which CaLRR13 mediates defense signaling, we investigated the subcellular localization of CaLRR13 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells through transient expression assays. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that CaLRR13 was distributed throughout the cell, with distinct localization observed in both the plasma membrane and nuclear compartments. Meanwhile, unlike the freely diffusible GFP control, CaLRR13-GFP displayed a discrete and specific subcellular localization (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Transcript levels of CaLRR13 under Ralstonia solanacearum infection or high-temperature stress and nuclear localization of CaLRR13 in N. benthamiana epidermal cells. (A) CaLRR13 transcript levels at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hpt in pepper “HN42” leaves under Ralstonia solanacearum infection or high-temperature stress, as determined by RT-qPCR, normalized to mock = 1. Data presented are the means ± standard error of four replicates. Different uppercase letters (A and B) above the bars indicate significant differences between means (p < 0.01), as calculated with Fisher’s protected t-test. (B) N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium cells containing 35S::CaLRR13-GFP (using 35S::GFP as a control). Subcellular localization of the CaLRR13-GFP fusion protein or control GFP was captured on a fluorescence confocal microscope at 24 hpi. Fluorescence images (left), bright-field images (middle), and the corresponding overlay images (right) of representative cells expressing GFP or CaLRR13-GFP fusion protein are shown; red bars = 50 µm.

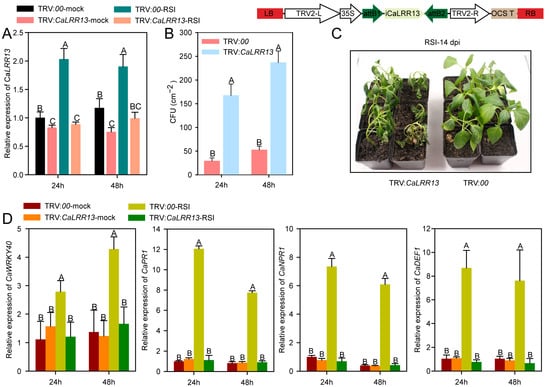

3.3. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) of CaLRR13 Compromises Pepper Resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum

To further investigate the disease resistance function of caLRR13, we employed virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) to knock down its expression in pepper. A specific fragment from the open reading frame (ORF) of caLRR13 was cloned into the pYL279 vector, while the empty vector (TRV:00) served as the control. VIGS assays were performed in pepper plants (HN42), and the expression level of the caLRR13 was validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Results showed that caLRR13 expression in TRV:caLRR13 plants was significantly downregulated compared to controls and did not exhibit induction upon ralstonia solanacearum infection (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

The effect of CaLRR13 knockdown on the response of pepper plants to R. solanacearum infection. (A) Relative transcript levels of CaLRR13 in TRV: CaLRR13 pepper plants challenged with R. solanacearum infection. (B) Effect of CaLRR13 knockdown on R. solanacearum growth, shown as colony-forming units (CFUs). (C) Bacterial wilt symptoms of pepper plants (CaLRR13-knockdown and control) challenged by R. solanacearum infection, at 14 dpi. (D) Relative transcript levels of the immunity-associated genes CaPR1, CaNPR1, CaDEF1, and CaWRKY40 in pepper plants (CaLRR13-knockedown and control) challenged by R. solanacearum infection, normalized to TRV:00-mock = 1. In (A,B,D), data are shown as the means ± standard error of four replicates. Different uppercase letters (A, B and C) above the bars indicate significant differences between means (p < 0.01) according to Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference (LSD) test.

Six randomly selected pepper plants from each of the TRV:CaLRR13 and TRV:00 plants were inoculated with R. solanacearum for bacterial growth analysis. Colony-forming unit (CFU) assays in leaves at 24 and 48 h post-inoculation revealed higher bacterial populations in CaLRR13-knockdown plants compared to controls (Figure 2B). Additionally, six CaLRR13-knockdown (TRV:CaLRR13) and control (TRV:00) plants were subjected to soil-drench inoculation with R. solanacearum to monitor disease progression. All CaLRR13-knockdown plants exhibited complete wilting within 14 days, whereas control plants remained asymptomatic (Figure 3C). Previous studies have demonstrated the critical roles of CaWRKY40, CaPR1, CaNPR1, and CaDEF1 in pepper disease resistance [57,61]. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of these defense-related genes in CaLRR13-knockdown and control plants after R. solanacearum infection. Results demonstrated that CaLRR13 knockdown significantly suppressed the induction of CaWRKY40, CaPR1, CaNPR1, and CaDEF1 expression during bacterial wilt infection compared to controls (Figure 3D). Collectively, these findings indicate that CaLRR13 knockdown markedly enhances pepper susceptibility to bacterial wilt and severely compromises disease resistance capacity.

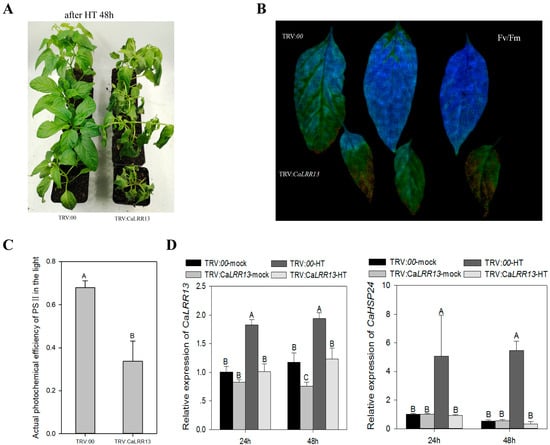

3.4. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing of CaLRR13 Reduces Pepper’s Tolerance to High Temperature

The transcriptional expression level of CaLRR13 is significantly induced by high temperature, suggesting its potential regulatory role in pepper’s response to heat stress. We subjected CaLRR13-knockdown plants and control plants to high-temperature (HT) treatment (42 °C) for 48 h, after which the CaLRR13-knockdown plants exhibited significantly reduced thermotolerance compared to the controls (Figure 4A). Using an Imaging-PAM chlorophyll fluorometer, we measured the maximum quantum yield Fv/Fm (reflecting the plant’s potential maximum photosynthetic capacity) and the actual quantum yield ΔF/Fm’ (reflecting real-time photosynthetic efficiency) of PSII in heat-stressed CaLRR13-knockdown and control plants. The results showed that both Fv/Fm and ΔF/Fm’ were significantly lower in CaLRR13-knockdown plants than in the controls (Figure 4B,C). Additionally, quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that the expression of the heat-responsive gene CaHSP24 [62] under high-temperature conditions was significantly reduced in CaLRR13-knockdown plants compared to the controls (Figure 4D). These findings demonstrate that CaLRR13 positively regulates the expression of CaHSP24 during high-temperature stress, thereby playing a critical role in enhancing pepper’s thermotolerance.

Figure 4.

Effect of CaLRR13 knockdown on the thermotolerance of pepper. (A) Phenotypic differences between CaLRR13-knockdown and non-knocked-down pepper plants under high-temperature treatment. (B,C) After the pepper plants with CaLRR13 knockdown and control pepper plants were treated with high temperature (HT), the pepper leaves were harvested directly on the living body to detect the kinetic parameters of chlorophyll fluorescence. (D) Detection of the relative expression of CaLRR13 and CaHSP24 in CaLRR13-knockdown and non-knocked-down leaves under HT by qRT-PCR; transcript levels of CaLRR13 and CaHSP24 normalized to TRV:00-mock at 24 hpi (set = 1). In (C,D), data are shown as the means ± standard error of four replicates. Different uppercase letters (A, B and C) above the bars indicate significant differences between means (p < 0.01) according to Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference (LSD) test. Meanwhile, in A and D: TRV:00-mock: CaLRR13 non-knockdown control plants at 28 °C and 80% RH; TRV:00-HT: CaLRR13 non-knockdown control plants under high temperature (42 °C and 80% RH); TRV:CaLRR13-mock: CaLRR13-knockdown plants at 28 °C and 80% RH; TRV:CaLRR13-HT: CaLRR13-knockdown plants under high temperature (42 °C and 80% RH).

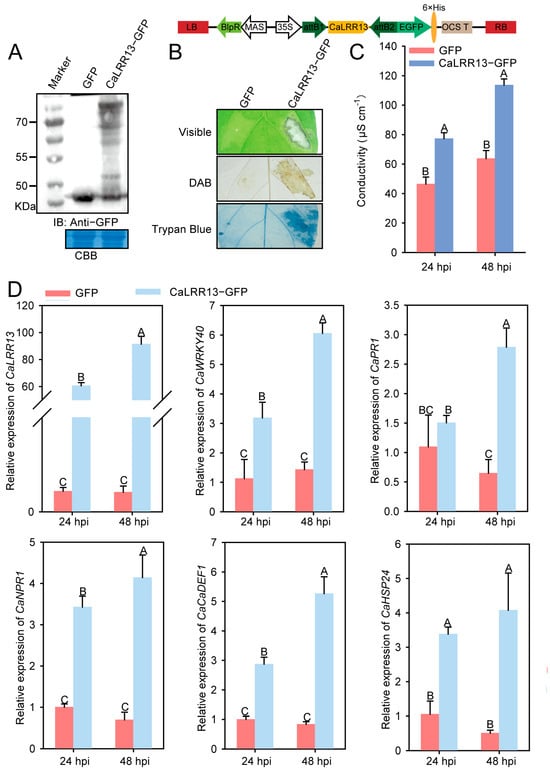

3.5. Transient Overexpression of CaLRR13 Activates Immune Responses and Upregulates CaHSP24

To further investigate the role of CaLRR13 in pepper immune responses, we performed transient overexpression assays in pepper leaves using Agrobacterium GV3101 harboring 35S::CaLRR13-GFP or the empty vector (35S::GFP). Western blot confirmed successful transient overexpression of CaLRR13 (Figure 5A). Compared to the empty vector control, CaLRR13-overexpressing leaves exhibited an enhanced like-hypersensitive response (HR), accompanied by intensified DAB staining (H2O2 accumulation) and trypan blue staining (cell death) at infiltration sites (Figure 5B). Additionally, CaLRR13 overexpression caused significantly elevated electrolyte leakage (Figure 5C), indicating aggravated membrane damage. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that transient overexpression of CaLRR13 not only upregulated its own expression but also significantly enhanced the transcript levels of immunity-related genes CaWRKY40, CaPR1, CaNPR1, and CaDEF1 and the thermotolerance-associated gene CaHSP24 (Figure 5D). These results suggest that CaLRR13 activation contributes to both immune responses and heat stress adaptation in pepper.

Figure 5.

The transient overexpression of CaLRR13 triggers the like-hypersensitive response (cell death) and the expression of immune-related genes or CaHSP24 in pepper leaves. (A) Western blot assay of CaLRR13 expression in pepper leaves by transient overexpression of CaLRR13-GFP at 48 hpi. α-GFP = anti-GFP antibody. (B) Transient overexpression of CaLRR13 can cause cell death, and the like-hypersensitivity phenotypes were shown by staining under white light, DAB staining, and trypan staining, using 35S::GFP as a control. (C) Quantitative measurement of electrolyte leakage caused by cell death using an ion conductivity meter. (D) The relative expression levels of defense-related genes (CaWRKY40, CaDEF1, CaNPR1, and CaPR1) and thermotolerance gene CaHSP24 by qRT-PCR at 24 and 48 hpi in pepper leaves infiltrated with A. tumefaciens GV3101 cells harboring 35S::CaLRR13-GFP or 35S::GFP. Transcript levels of CaLRR13 under different treatments at different time points were compared to that of the 35S::GFP agro-infiltrated leaves at 24 hpi, which was set to “1”. In (C,D), data presented are means ± SE of four replicates; different capital letters indicate significant differences between means (p < 0.01), as calculated with Fisher’s protected LSD test.

4. Discussion

Leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing proteins play crucial roles in plant growth, plant development, and enhancing resistance to both biotic and abiotic stresses [22,23,24,25,26]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which LRR-only proteins coordinate plant immune responses and abiotic stress tolerance remain poorly characterized. In this study, we provide evidence demonstrating that CaLRR13, a novel LRR-only protein identified in pepper, acts as a positive regulator in enhancing resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum and thermotolerance.

4.1. CaLRR13 as a Novel LRR-Only Protein with Dual Roles in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Adaptation

Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains are indispensable components of plant immune receptors, including receptor-like kinases (RLKs), receptor-like proteins (RLPs), and nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins. These domains play critical roles in pathogen recognition, receptor interaction, and signal transduction during both PTI and ETI [32,35]. In this study, we identified CaLRR13, a unique LRR-only protein, which exhibited significant upregulation under combined HTHH conditions during R. solanacearum infection, based on a publicly available RNA-seq analysis [49]. Promoter analysis of CaLRR13 revealed key cis-acting elements linked to stress responses, including MYB-binding sites (drought/defense), TC-rich repeats (defense/stress), and salicylic acid-responsive elements (TCA), suggesting its transcriptional regulation under biotic or abiotic stresses (Figure 1D). Expression profiling demonstrated that CaLRR13 is dynamically induced by both R. solanacearum infection (peaking at 12 hpi) and heat stress (maximal at 48 h), with synergistic upregulation under combined stresses (Figure 2A), aligning with its promoter regulatory elements. Structural characterization revealed that CaLRR13 contains 17 LRR repeats but lacks canonical domains such as kinase, transmembrane, or nucleotide-binding sites (NBSs) (Figure 1A,B), distinguishing it from typical RLKs or NBS-LRR proteins [63,64]. Recent studies have identified extracellular LRR (eLRR) proteins in plants, such as OsLRR1 in rice and CaLRR1 in pepper, which carry additional N-terminal signal peptides (SP) or leucine zipper (LZ) motifs [33,34]. However, CaLRR13 represents a distinct subclass of eLRR proteins due to its absence of SP or LZ structures, as reported for LRR-only proteins in Arabidopsis, amphioxus, and Chlamys farreri [40,41,43], suggesting a minimalist design for stress adaptation. Subcellular localization experiments revealed that CaLRR13 localizes to both the plasma membrane and the nucleus (Figure 2B), a pattern distinct from other eLRR proteins like OsLRR1 (endosome-associated) [33] or NtLRP1 (endoplasmic reticulum-localized) [64]. This dual localization implies multifunctional roles in pathogen sensing at the membrane and transcriptional regulation in the nucleus, a mechanism rarely reported for LRR-only proteins.

4.2. CaLRR13 as a Positive Regulator of Pepper Immunity Against Bacterial Wilt

The induction of CaLRR13 expression upon R. solanacearum infection (Figure 2A) and its functional validation through loss- and gain-of-function assays underscore its critical role in pepper immunity. Virus-induced gene knockdown of CaLRR13 significantly compromised resistance, as evidenced by increased bacterial colonization (Figure 3B), accelerated wilting (Figure 3C), and suppressed expression of defense-related genes CaWRKY40, CaPR1, CaNPR1, and CaDEF1 [57,61] (Figure 3D). Conversely, transient overexpression of CaLRR13 induced cell death consistent with a like-hypersensitive response, which was associated with elevated H2O2 accumulation and enhanced expression of immune genes (Figure 5B–D). These findings align with reports on other eLRR proteins, such as OsLRR1 and CaLRR1, which regulate immunity through protein–protein interaction [33,34]. The nuclear localization of CaLRR13 suggests a dual mechanism: membrane-associated recognition of pathogen-derived signals and transcriptional activation of defense pathways via interaction with WRKY or other transcription factors. This dual functionality bridges PTI and ETI signaling, reinforcing the “zig-zag-zig” model of plant immunity [8,32].

4.3. CaLRR13 Coordinates Thermotolerance and Stress Crosstalk

Beyond biotic stress, CaLRR13 emerged as a key player in pepper thermotolerance. Its transcription was robustly induced by high-temperature stress (Figure 2A), and silencing led to impaired photosynthetic efficiency (Figure 4B,C) and diminished expression of the heat shock gene CaHSP24 (Figure 4D). To our knowledge, this is the first report of an LRR-only protein directly regulating thermotolerance in plants. The co-induction of CaLRR13 under both heat and pathogen stress (Figure 2A) highlights its role as a molecular integrator of cross-stress adaptation—a trait critical for crops in climate-variable environments. Similar to stress-responsive genes like CaWRKY6, CabZIP63, CaCDPK15, and CaASR1 [56,59,65], CaLRR13 likely operates within a regulatory network that coordinates overlapping responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. Given pepper’s origin in tropical and subtropical regions, where high humidity and temperature favor R. solanacearum proliferation, the dual functionality of CaLRR13 may reflect an evolutionary adaptation to intertwined environmental challenges.

4.4. Mechanistic Insights: CaLRR13 as a Non-Canonical PRR

Although CaLRR13 lacks kinase or NBS domains, its function as a PRR likely depends on partnerships with other signaling components. We propose two mechanistic axes: (1) Membrane signaling: Analogous to OsLRR1, which interacts with OsHIR1 to activate defense [33], CaLRR13 may form complexes with RLKs (BAK1 orthologs) or RLPs to transduce pathogen signals. Its LRR domain could bind microbial patterns or host-derived DAMPs, triggering MAPK cascades and ROS bursts [9,30]. (2) Nuclear regulation: Nuclear-localized CaLRR13 might interact with transcription factors like WRKY40 [65] to amplify defense gene expression. The presence of SA- and GA-responsive cis-elements in its promoter (Figure 1D) further supports its integration into phytohormone networks [59,66,67]. This model aligns with small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) in Arabidopsis, which mediate protein interactions critical for cellular signaling [67]. The minimalist architecture of CaLRR13 challenges the dogma that PRRs require kinase domains, expanding the functional repertoire of LRR-only proteins as modular scaffolds in stress signaling.

5. Conclusions

CaLRR13 acts as a positive regulator in enhancing resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum and thermotolerance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121485/s1. Table S1: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., S.Y., and J.H.; methodology, J.H. and S.Y.; validation, J.H., Y.L., and Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.L. and Y.H.; investigation, J.H.; resources, S.H.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; visualization, J.H.; supervision, S.H. and S.Y.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was Supported by The Doctoral Research Initiation Fund of Zhangzhou Institute of Technology under grant number ZZYB2212, and the Young and Middle-aged Faculty Education Research Project (Science and Technology Category) of Fujian Provincial Education Department under grant number JAT231257.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark D. Curtis for kindly providing the Gateway destination vectors, and S. P. Dinesh-Kumar of the University of California, Davis for the pTRV1 and pTRV2 vectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HTHH | High Temperature and High Humidity |

| RSI | Ralstonia Solanacearum Infection |

References

- Zhang, Z.B.; Wu, Y.L.; Gao, M.H.; Zhang, J.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Y.N.; Ba, H.P.; Zhou, J.M.; Zhang, Y.L. Disruption of PAMP-induced MAP kinase cascade by a Pseudomonas syringae effector activates plant immunity mediated by the NB-LRR protein SUMM2. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zvereva, A.S.; Pooggin, M.M. Silencing and innate immunity in plant defense against viral and non-viral pathogens. Viruses 2012, 4, 2578–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.X.; Cao, Y.R.; Jansen Labby, K.; Bittel, P.; Boller, T.; Bent, A.F. Probing the Arabidopsis flagellin receptor: FLS2-FLS2 association and the contributions of specific domains to signaling function. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1096–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.P.; Nürnberger, T.; Joosten, M.H. Of PAMPs and effectors: The blurred PTI-ETI dichotomy. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Katagiri, F. Comparing signaling mechanisms engaged in pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Henty-Ridilla, J.L.; Staiger, B.H.; Day, B.; Staiger, C.J. Capping protein integrates multiple MAMP signalling pathways to modulate actin dynamics during plant innate immunity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, I.; Gilroy, E.M.; Armstrong, M.R.; Birch, P.R.J. The zig-zag-zig in oomycete-plant interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Staskawicz, B.J.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system: From discovery to deployment. Cell 2024, 187, 2095–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.F.; Wei, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.L.; Zhang, Y.; She, X.M.; Macho, A.P.; Ding, W.; Liao, B.S. Bacterial Wilt in China: History, Current Status, and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Vance, R.E.; Dangl, J.L. Intracellular innate immune surveillance devices in plants and animals. Science 2016, 354, aaf6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P.N.; Lawrence, G.J.; Ellis, J.G. Six amino acid changes confined to the leucine-rich repeat beta-strand/beta-turn motif determine the difference between the P and P2 rust resistance specificities in flax. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, P.N.; Lawrence, G.J.; Catanzariti, A.-M.; Teh, T.; Wang, C.-I.A.; Ayliffe, M.A.; Kobe, B.; Ellis, J.G. Direct protein interaction underlies gene-for-gene specificity and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8888–8893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, J.; Padmanabhan, M.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. Plant NB-LRR immune receptors: From recognition to transcriptional reprogramming. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.-F.; Williamson, V.M. Leucine-rich repeat-mediated intramolecular interactions in nematode recognition and cell death signaling by the tomato resistance protein Mi. Plant J. 2003, 34, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rairdan, G.J.; Moffett, P. Distinct domains in the ARC region of the potato resistance protein Rx mediate LRR binding and inhibition of activation. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffett, P.; Farnham, G.; Peart, J.; Baulcombe, D.C. Interaction between domains of a plant NBS-LRR protein in disease resistance-related cell death. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4511–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, J.; DeYoung, B.J.; Golstein, C.; Innes, R.W. Indirect activation of a plant nucleotide binding site-leucine-rich repeat protein by a bacterial protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, D.; DeYoung, B.J.; Innes, R.W. Structure-function analysis of the coiled-coil and leucine-rich repeat domains of the RPS5 disease resistance protein. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1819–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, S.; Mauch, S.; Shen, Q.-H.; Peart, J.; Devoto, A.; Casais, C.; Ceron, F.; Schulze, S.; Steinbiss, H.-H.; Shirasu, K.; et al. RAR1 positively controls steady state levels of barley MLA resistance proteins and enables sufficient MLA6 accumulation for effective resistance. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 3480–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tang, W.; Swain, J.D.; Green, A.L.; Jack, T.P.; Gan, S. Networking senescence-regulating pathways by using Arabidopsis enhancer trap lines. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, G.M.; Davies, C.; Shavrukov, Y.; Dry, I.B.; Reid, J.B.; Thomas, M.R. Grapes on steroids. Brassinosteroids are involved in grape berry ripening. Plant Physiol. 2005, 140, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divi, U.K.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid: A biotechnological target for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance. New Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.Q.; Zhu, W.J.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.S.; Yin, Y.H.; Ma, H.; Wang, X. Brassinosteroids control male fertility by regulating the expression of key genes involved in Arabidopsis anther and pollen development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6100–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkhadir, Y.; Jaillais, Y. The molecular circuitry of brassinosteroid signaling. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, J.Q.; Lease, K.A.; Doke, J.T.; Tax, F.E.; Walker, J.C. BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 2002, 110, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, G.H.; Li, J.; Gong, Z.; Wang, G.J.; Dong, L.L.; Zhang, H.Z.; Guo, G.H.; Su, M.; Wang, K.; et al. A wheat tandem kinase and NLR pair confers resistance to multiple fungal pathogens. Science 2025, 387, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boller, T.; Felix, G. A renaissance of elicitors: Perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gómez, L.; Felix, G.; Boller, T. A single locus determines sensitivity to bacterial flagellin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999, 18, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.Z.; Wang, G.X.; Zhou, J.-M. Receptor Kinases in Plant-Pathogen Interactions: More Than Pattern Recognition. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoorn, R.A.; Jones, J.D. The plant proteolytic machinery and its role in defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004, 7, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cheung, M.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lei, C.L.; Zhang, S.H.; Sun, S.S.; Lam, H.M. A novel simple extracellular leucine-rich repeat (eLRR) domain protein from rice (OsLRR1) enters the endosomal pathway and interacts with the hypersensitive-induced reaction protein 1 (OsHIR1). Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 1804–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cheung, M.Y.; Li, M.W.; Fu, Y.P.; Sun, Z.X.; Sun, S.M.; Lam, H.M. Rice hypersensitive induced reaction protein 1 (OsHIR1) associates with plasma membrane and triggers hypersensitive cell death. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.S.; Hwang, I.S.; Hwang, B.K. Requirement of the cytosolic interaction between PATHOGENESIS-RELATED PROTEIN10 and LEUCINE-RICH REPEAT PROTEIN1 for cell death and defense signaling in pepper. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1675–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Hwang, B.K. The hypersensitive induced reaction and leucine-rich repeat proteins regulate plant cell death associated with disease and plant immunity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 24, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Hwang, B.K. The leucine-rich repeat (LRR) protein, CaLRR1, interacts with the hypersensitive induced reaction (HIR) protein, CaHIR1, and suppresses cell death induced by the CaHIR1 protein. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.S.; Choi, D.S.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, D.S.; Hwang, B.K. Pathogenesis-related protein 4b interacts with leucine-rich repeat protein 1 to suppress PR4b-triggered cell death and defense response in pepper. Plant J. 2014, 77, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Xiao, Z.L.; Cai, H.Y.; Wang, C.Q.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, Y.P.; Zheng, Y.X.; Shen, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z.Q.; et al. A novel leucine-rich repeat protein, CaLRR51, acts as a positive regulator in the response of pepper to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, P.; Yong, S.Y.; Mohanty, B.; Kumar, P.P. An LRR-only protein regulates abscisic acid-mediated abiotic stress responses during rabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.F.; Yuan, S.C.; Guo, L.; Yu, Y.H.; Li, J.; Wu, T.; Liu, T.; Yang, M.Y.; Wu, K.; Liu, H.L.; et al. Genomic analysis of the immune gene repertoire of amphioxus reveals extraordinary innate complexity and diversity. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 1112–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.F.; Wang, X.; Yan, Q.Y.; Guo, L.; Yuan, S.C.; Huang, G.R.; Huang, H.Q.; Li, J.; Dong, M.L.; Chen, S.W.; et al. The evolution and regulation of the mucosal immune complexity in the basal chordate amphioxus. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 2042–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Guo, Y.; Yi, Q.L.; Song, L.S. An LRR-only protein representing a new type of pattern recognition receptor in Chlamys farreri. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015, 54, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Xin, L.S.; Wang, X.D.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.C.; Jia, Z.H.; Yue, F.; Wang, H.; Song, L.S. Two novel LRR-only proteins in Chlamys farreri: Similar in structure, yet different in expression profile and pattern recognition. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 59, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, C.A.; Barberis, P.A.; Demery, D.A. Transposon mutagenesis of pseudomonas solanacearum: Isolation of YN5-induced Avirulent Mutants. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1985, 131, 2449–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, S.; Iriarte, F.; Fan, Q.; da Silva, E.E.; Ritchie, L.; Nguyen, N.S.; Freeman, J.H.; Stall, R.E.; Jones, J.B.; Minsavage, G.V.; et al. Transgenic expression of EFR and Bs2 genes for field management of bacterial wilt and bacterial spot of tomato. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.L.; Caceres-Moreno, C.; Jimenez-Gongora, T.; Wang, K.K.; Sang, Y.Y.; Lozano-Duran, R.; Macho, A.P. The Ralstonia solanacearum csp22 peptide, but not flagellin-derived peptides, is perceived by plants from the Solanaceae family. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, C.; Huet, G.; Jauneau, A.; Camborde, L.; Trémousaygue, D.; Kraut, A.; Zhou, B.; Levaillant, M.; Adachi, H.; Yoshioka, H.; et al. A receptor pair with an integrated decoy converts pathogen disabling of transcription factors to immunity. Cell 2015, 161, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Cai, W.W.; Shen, L.; Wu, R.J.; Cao, J.S.; Tang, W.Q.; Lu, Q.L.; Huang, Y.; Guan, D.Y.; He, S.L. Solanaceous plants switch to cytokinin-mediated immunity against Ralstonia solanacearum under high temperature and high humidity. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 45, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.N.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.M.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, L.K.; Yang, X.L.; Yu, H.L.; Cao, Y.C.; Zhang, L.; Cai, C.C.; et al. The gap-free assembly of pepper genome reveals transposable-element-driven expansion and rapid evolution of pericentromeres. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, F.F.; Wang, Y.N.; She, J.J.; Lei, Y.F.; Liu, Z.Q.; Eulgem, T.; Lai, Y.; Lin, J.; Yu, L.; Lei, D.; et al. Overexpression of CaWRKY27, a subgroup IIe WRKY transcription factor of Capsicum annuum, positively regulates tobacco resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 150, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.Y.; Yang, S.; Yan, Y.; Xiao, Z.L.; Cheng, J.B.; Wu, J.; Qiu, A.L.; Lai, Y.; Mou, S.L.; Guan, D.Y.; et al. CaWRKY6 transcriptionally activates CaWRKY40, regulates Ralstonia solanacearum resistance, and confers high-temperature and high-humidity tolerance in pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3163–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.Q.; Wen, J.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, J.Z.; Shi, L.P.; Tang, Q.; et al. Pepper CabZIP63 acts as a positive regulator during Ralstonia solanacearum or high temperature-high humidity challenge in a positive feedback loop with CaWRKY40. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2439–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.F.; Shen, L.; Yang, S.; Guan, D.Y.; He, S.L. CaASR1 promotes salicylic acid- but represses jasmonic acid-dependent signaling to enhance the resistance of Capsicum annuum to bacterial wilt by modulating CabZIP63. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 6538–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.M.; Liu, B.B.; Wu, Y.; Zou, Z.R. Interactive effects of drought stresses and elevated CO2 concentration on photochemistry efficiency of cucumber seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Després, C.; Chubak, C.; Rochon, A.; Clark, R.; Bethune, T.; Desveaux, D.; Fobert, P.R. The Arabidopsis NPR1 disease resistance protein is a novel cofactor that confers redox regulation of DNA binding activity to the basic domain/leucine zipper transcription factor TGA1. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2181–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckathorn, S.A.; Poeller, G.J.; Coleman, J.S.; Hallberg, R.L. Nitrogen availability alters patterns of accumulation of heat stress-induced proteins in plants. Oecologia 1996, 105, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.W.; Hwang, B.K. Isolation, partial sequencing, and expression of pathogenesis-related cDNA genes from pepper leaves infected by Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.; Ghannam, A.; Erhardt, M.; de Ruffray, P.; Baillieul, F.; Kauffmann, S. NtLRP1, a tobacco leucine-rich repeat gene with a possible role as a modulator of the hypersensitive response. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.Q.; Cheng, W.; Wen, J.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, J.Z.; Shi, L.P.; Tang, Q.; et al. CaCDPK15 positively regulates pepper responses to Ralstonia solanacearum inoculation and forms a positive-feedback loop with CaWRKY40 to amplify defense signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, S.D.; Sasse, J.M. BRASSINOSTEROIDS: Essential Regulators of Plant Growth and Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 49, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.Y.; Li, L.; Lam, P.Y.; Chen, M.X.; Chye, M.L.; Lo, C. Sorghum extracellular leucine-rich repeat protein SbLRR2 mediates lead tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).