Abstract

Zephyranthes tubispatha is an Amaryllidaceae species with high ornamental potential, whose seed dispersal coincides with periods of high temperatures (HTs) and long photoperiods. While supraoptimal temperatures (>28 °C) have been shown to induce thermoinhibition, the effect of light on germination dynamics has not yet been explored. The aim was to study the effect of different exposure times to white light (WL) and different light qualities, as well as the interaction with HT, on seed germination. Changes in the endogenous levels of several phytohormones, responses to pharmacological treatments, and O2.− production in the embryo were analyzed to gain an understanding of the underlying physiological mechanisms. Our results suggest the presence of a negative photoblastic response of the high-irradiance (HIR) type. Fluridone (an ABA synthesis inhibitor) restored germination in light-exposed seeds to levels close to the dark control, highlighting the importance of ABA content for photoinhibition. The preincubation period at HT (33 °C) significantly influenced germination behavior and photosensitivity at optimal temperature (20 °C). Thermoinhibition depends on changes in phytohormone balance and/or sensitivity, rather than on their absolute concentration. Unlike thermoinhibition, photoinhibition was not associated with the suppression of O2.− production in the embryonic root pole, confirming that these environmental signals utilize different regulatory pathways.

1. Introduction

Zephyranthes tubispatha (L’Hér.) Herb. is a bulbous species of the Amaryllidaceae family, native of the American continent and highly represented in Central and Southern Chile, Southern Brazil, Paraguay, Southern Uruguay, and Argentina [1]. In the latter country, it can be predominantly found in the provinces of Corrientes, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Buenos Aires, either in undisturbed mountainous areas, as well as rural, urban, and peri-urban zones [1,2,3]. While its bulbs are of pharmacological interest due to the presence of alkaloids with antiviral and antitumoral properties [4], it is mainly regarded as a potential ornamental due to its attractive colorful flowers, its great adaptability to semi-arid zones, and the ecosystem services it provides [5,6,7].

Z. tubispatha presents several consecutive flowerings from the end of spring to the end of summer, so the dispersal of seeds may coincide with periods of high temperatures (HT) and long photoperiods. On the other hand, seedling emergence mostly occurs during autumn–winter conditions, with lower temperatures and short photoperiods. Previous work showed that maximum germination percentages are reached at temperatures between 7 and 25 °C, with almost null germination occurring at temperatures close to, and, particularly, higher than, 30 °C [8]. The rapid recovery of germination when seeds imbibed under high temperature (HT) are transferred to optimal thermal conditions (20 °C) indicates the presence of thermoinhibition [8]. Interestingly, seedlings produced by these seeds maintain both high vigor and high survival rates, even when seeds had been previously exposed to long thermoinhibitory periods [9]. The effectiveness of this mechanism has been interpreted as an adaptive strategy to increase the seed bank, while minimizing the germination of seeds dispersed during high-temperature periods. At the physiological level, these thermal responses have been shown to be partially regulated by changes in the sensitivity to ascorbic acid and H2O2, as well as the balance and/or sensitivity to ethylene (ET) and abscisic acid (ABA) [8].

Apart from the thermoinhibitory effect exerted by HT, preliminary work by our group indicates that germination rate in this species can be delayed in the presence of light (unpublished data). It is well known that light cues are also important to prevent germination under environmental conditions that are unfavorable for seedling establishment (e.g., [10]). Depending on germination responses to light, plants can be classified as positive photoblastic (light stimulates germination), negative photoblastic (light represses germination), or neutral photoblastic (germination does not depend on light cues) [11]. This classification considers responses to the entire spectrum of white light, regardless of wavelength-specific effects [12]. In photoblastic seeds, the germination response can vary depending on both the length of the photoperiod and the intensity and spectral quality of the incident light [13]. Both phytochrome B and A (phyB and phyA) have been shown to mediate light responses in photoblastic species (see [14] and references therein). However, while phyB is mostly involved in the classical red–far red reversible low-fluence responses (LFR), phyA would mediate both the very low fluence and the high-irradiance types of responses (VLFR and HIR, respectively). Interestingly, thermal reversion of active phytochrome (Pfr) to its inactive form (Pr) also enables it to function as a thermosensor, which may help to integrate light and temperature cues in the control of different developmental processes, including germination [15,16].

The suppression or retardation of seed germination in negative photoblastic seeds has been shown to depend mostly on phyA [17] and can be modulated by day length. For example, Mérai et al. [18,19] reported that certain accessions from Aethionema arabicum do not germinate under white light when supplied at long day conditions but can germinate in short days. This response would favor germination and seedling establishment in the spring, while it would repress germination in summer, when environmental conditions are more stressful for seedling establishment. Although germination dynamics of Z. tubispatha seeds might be under a similar kind of control by light cues, this has not been investigated. Moreover, to our knowledge, no study on the interaction between light and temperature on the germination responses of this species or closely related species have been undertaken. In this respect, further investigation of the underlying mechanisms that regulate germination by both high temperature and long photoperiods would provide information on which metabolic pathways are triggered in response to environmental signals that help to prevent germination under unfavorable conditions for seedling establishment.

It is widely accepted that the control of germination by light cues is associated with the modification of hormonal balance (see [12] and references therein). In positive photoblastic model species such as lettuce and Arabidopsis thaliana, light stimulates the production of gibberellic acid (GA) and diminishes the level of ABA by regulating the expression of key genes involved in their synthesis and/or degradation. Interestingly, in seeds of Aethionema arabicum (a negative photoblastic species from the Brassicaceae family), the photoinhibition of seed germination (PISG) also involves changes in the balance of ABA and GA; transcriptome comparisons of light- and dark-exposed seeds revealed that, upon light exposure, the expression of genes for key regulators undergo opposite changes, resulting in hormone regulation that is antagonistic to that found in A. thaliana [12]. Nevertheless, other phytohormones such as ET, jasmonate (JA), and methyl jasmonate (MeJa) may be involved in the control of germination in response to different environmental cues (e.g., [20,21,22,23]). Particularly, ET was shown to alleviate the inhibitory effect of high temperatures in different plant species, including Z. tubispatha (see [8,23] and references therein), although its role in mediating light responses has not been clearly elucidated.

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of different exposure times to white light, as well as different light qualities on the germination dynamics of Z. tubispatha seeds, and explored the interaction between high temperature and white light in modulating germination responses. On the other hand, we analyzed the changes in the endogenous levels of several phytohormones under specific thermal and light conditions to gain insight into the physiological mechanisms involved.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collection and General Germination Conditions

Ripe fruits were collected during the month of December in 2024 in the Sierras de Azul (S 37°8.254′ W 59°46.386′). The harvested fruits were manually processed and the seeds obtained were placed on brown paper to dry at room temperature (approximately 2 weeks). Once dry, seeds were kept in polyethylene tubes and double-bagged plastic bags and stored in a refrigerator (10 °C) until use.

All germination tests were conducted in Petri dishes with 30 seeds each, sown in triplicate on a layer of filter paper, four layers of paper towels, and 5 mL of distilled water or different pharmacological solutions (see below). To prevent water evaporation, the boxes were placed inside transparent plastic containers containing foam rubber soaked with water. The containers were covered with transparent or black plastic bags, depending on the illumination conditions required (see below). Germination was performed in culture chambers set at 20 °C or 33 °C, depending on the temperature treatment.

2.2. Germination Assays and Pharmacological Treatments

To evaluate the effect of light, germination was first conducted at an optimum temperature (20 °C), in seeds exposed to the following conditions:

(i) A single pulse of 0, 2, 6, or 12 h white light (WL), supplied after 12 h darkness (D) at the beginning of the assay, followed by darkness. Alternate warm- and cool-white LED strips were used as WL source.

(ii) Daily photoperiods of 24/0, 22/2, 18/6 or 12/12 h (D/WL).

(iii) Different light qualities (red = R, blue = B, or combined = R + B), supplied with LED lamps of narrow band emission spectra (R = 660 ± 20 nm; B = 450 ± 20 nm), set at 12 h photoperiod.

Average PAR values (µmol m−2 s−1) of the different illumination conditions, measured with a Li-250A Light Meter (Li-Cor, Lincoln, USA), were: 46.4 (WL), 37.7 (R), 16.2 (B), and 50.3 (R + B).

To evaluate the interaction between light and high temperature (HT) on germination dynamics, the following treatments were performed:

(i) Preincubation of the germination plates for 0, 9, or 25 days at supraoptimal temperature (HT = 33 °C), under darkness, and then transferred to 20 °C under darkness or a 12 h WL photoperiod.

(ii) Preincubation of the germination plates for 30 days at 33 °C with or without WL (12 h photoperiod) and then transfer to 20 °C, also under darkness or a 12 h WL photoperiod.

In addition, seeds were incubated at 20 °C in the darkness (D) or under a 12 h white light photoperiod (12 h D/WL) in the presence of 40 μM fluridone (Flu, an inhibitor of ABA synthesis) or 75 mg/mL ethephon (Et, an ethylene supplier) to pharmacologically modulate the endogenous levels of these phytohormones. For the same purpose, seeds were incubated at 33 °C under darkness (D) in the presence of 40 μM Flu added either at the beginning (t0) or after 25 days (t25) of incubation under HT. Since seeds do not germinate at HT, to facilitate graphical representation and comparisons among treatments, the cumulative germination data of the Flu t25 treatment were computed from the addition of the reagent. Germination was recorded within 8–30 h intervals, depending on the experiment, under dim green light. When indicated, the number of days to 10% germination (T10) and to 50% germination (T50) were used as estimators of germination beginning and germination rate, respectively.

2.3. Phytohormone Measurements

To gain insight into the physiological mechanism underlying the different germination responses observed, changes in the level of ABA, GA3, JA, and MeJA were evaluated under specific treatment conditions (see below), according to [24], with some modifications. Briefly, 50–100 mg of tissue previously pulverized with liquid N2 were weighed, homogenized with 500 µL of 1-propanol/H2O/concentrated HCl (2:1:0.002; v/v/v), and stirred for 30 min at 4 °C. Then, 1 mL of dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) was applied, stirred for 30 min at 4 °C, and centrifuged at 13,000× g for 5 min. The lower organic phase (approx. 1 mL) was collected in vials, which were evaporated in a gaseous N2 sequence. Finally, the residue was re-dissolved with 0.25 mL of 50% methanol (HPLC grade) containing 0.1% CH2Cl2 plus 50% water also containing 0.1% CH2Cl2, and stirred slightly with a vortex. The LC-MS Waters Xevo TQs Micro (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was equipped with a quaternary pump (Acquity UPLC H-Class, Waters), autosampler (Acquity UPLC H-Class, Waters), and a reversed-phase column (C18 Waters BEH 1.7 µm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters). The mobile solvent system was composed of water with 0.1% CH2O2 (A) and MeOH (B), with a flow of 0.25 mL/min. The initial gradient of B was maintained at 40% for 0.5 min, and then linearly increased to 100% at 3 min. For identification and quantification purposes, a mass spectrometer Xevo TQ-S micro from Waters (Milford, MA, USA) coupled to the abovementioned UPLC (LC-MS/MS) was used. The ionization source was used with electrospray (ESI), and the MassLynx Software (version 4.1) was used for data acquisition and processing. The mass spectra of the data were recorded in positive mode. The mass/charge ratio (m/z) for each metabolite were as follows: ABA: 263.0 > 153.0 and 263.0 > 219.0; JA: 209.1 > 59.0 and 209.1 > 165.1; GA3: 345.1 > 239 and 345.1 > 143; MeJA: 225.3 > 151.2 and 225.3 > 133.1. The phytohormone concentrations were calculated from calibration curves with linear adjustment, and the results were expressed as ng phytohormone/g fresh tissue.

The determinations were carried out on seed samples taken from seeds exposed to 20 °C in the presence or absence of light (12 h photoperiod), either at 12 h from sowing or at the time of germination beginning (IG) of the darkness control (D). On the other hand, seeds germinated in the darkness under thermoinhibitory conditions (33 °C) were sampled either at 12 h or at 120 h from sowing (see Supplementary Materials, Figure S1). Dry seeds were also tested to evaluate the initial concentration of phytohormones.

Given that changes in seed hydration level may hinder the comparison of phytohormone concentration between different treatments when expressed on a fresh weight basis, seed samples were weighed at the beginning and at the end of the treatment conditions evaluated, and phytohormone concentrations were then normalized to gram of non-hydrated (i.e., “dry seed”) weight.

2.4. Histochemical Detection of Superoxide Anion

To detect superoxide anion (O2.−) production, embryos and/or seedlings from 10 seeds, randomly sampled from selected treatments, were isolated and immediately stained for 20 min with a solution of 0.05% (w/v) nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) in the dark (modified from [8]). Samples were immediately rinsed with plenty of distilled water to stop the reaction and photographed under a binocular magnifying glass stereoscopic Arcano (AC 230 V 50 Hz).

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistical Tests

To characterize germination responses to the different treatments, cumulative germination percentage vs. sampling time was represented. One-way ANOVAs were performed to test for significant differences in T10 and T50 values as well as phytohormone concentrations. Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests were used to identify homogeneous groups. When necessary, data were Log transformed to meet ANOVA assumptions. In those cases where ANOVA assumptions could not be met, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was performed. Treatment differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05, unless otherwise indicated. All statistical analyses were performed with Infostat 2017 version [25].

3. Results

3.1. Responses to Light Treatments

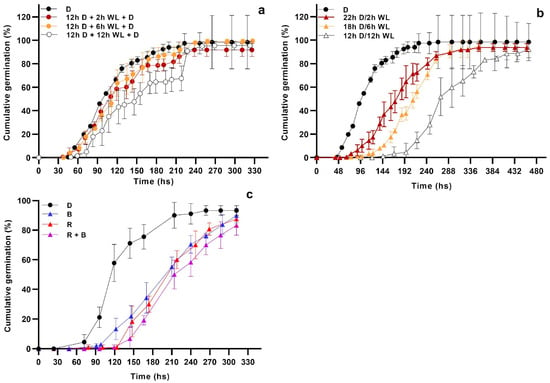

When seeds were exposed to a unique pulse of WL during the first day of the germination assay, no major effects on the germination dynamics were observed when compared to the darkness control (Figure 1a). The only exception was found for seeds that received a 12 h WL pulse, whose T50 was delayed by about 43.2 h with respect to the control (p < 0.05). On the contrary, the presence of 2 to 12 h WL photoperiods increasingly delayed the time to germination initiation and germination rate (Figure 1b). This negative effect was particularly marked in seeds exposed to the 12 h photoperiod, in which T10 and T50 were reached, on average, 143 and 113 h later, respectively, than in the dark control (p < 0.05 for both traits; Figure 1b). When the effect of light spectral quality was analyzed, it was observed that blue and red wavelengths (12 h photoperiod) exerted a similar delaying effect on the germination dynamics, either when supplied alone or combined (Figure 1c). Altogether these data suggest that a negative photoblastic response of the HIR type could be the underlying phenomenon.

Figure 1.

Cumulative germination at 20 °C of Z. tubispatha seeds exposed to (a) 12 h darkness (D) plus a single pulse of white light (WL) of different duration (0, 2, 6 or 12 h), at the first day of incubation; (b) daily photoperiods of 24/0, 22/2, 18/6 or 12/12 h (D/WL); (c) 12 h photoperiod with different light qualities: red (R), blue (B), and combined red + blue (R + B). Data are means ± standard deviation.

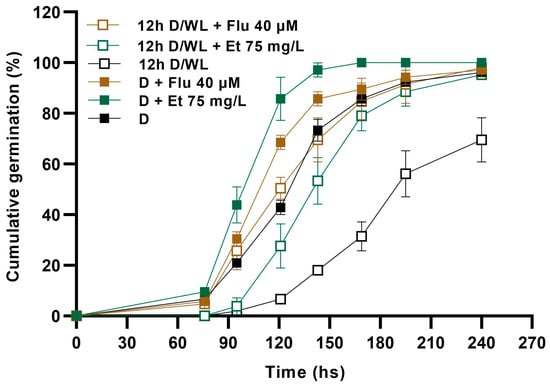

When we evaluated the effect of ethephon and fluridone supplementation on germination in the dark or under a 12 h photoperiod, we found that, while ethephon significantly accelerated seed germination both in the presence and absence of light, it was not able to fully restore the germination dynamics of light-exposed seeds to the level of those in treatment D (i.e., seeds exposed to darkness, without ethephon) (Figure 2). Moreover, under ethephon supply, there persisted an average difference of 42 h in T50 between seeds from both lighting conditions. In contrast, fluridone supply increased the germination rate in the presence of light to levels similar to those of the darkness control (i.e., without fluridone), and the average difference in T50 between the light and dark treatments in the presence of the reagent did not exceed 15 h (Figure 2). This indicates that ABA rather than ethylene synthesis would be particularly important for PISG in our experimental model.

Figure 2.

Cumulative germination of Z. tubispatha seeds in darkness (D) or under 12 h WL photoperiod (12 h D/WL), either in the absence or presence of 40 µm fluridone (Flu) or 75 mg/mL ethephon (Et). Data are means ± SD.

3.2. High Temperature and Light Interactions

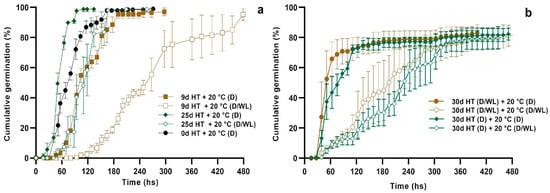

Under darkness conditions (D), the period of preincubation at supraoptimal temperature (33 °C) either delayed (9 days HT preincubation) or accelerated (25 days HT) seed germination at optimum temperature (20 °C), when compared to the control (0d HT) (Figure 3a, see also [8]). When seed germination at 20 °C was tested under a 12 h photoperiod (12 h D/WL), light sensitivity was significantly reduced as the period of preincubation at HT increased, with seeds from the 25d HT treatment showing a germination response close to that of the 0d HT darkness control (Figure 3a). Contrary to expected, the presence of a 12 h photoperiod during HT preincubation did not significantly alter the germination response at 20 °C, regardless of whether the latter was conducted either in darkness or in the presence of light (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Cumulative germination of Z. tubispatha seeds at optimum temperature (20 °C) under darkness (D) or 12 h photoperiod (D/WL) after (a) 0, 9, or 25 days preincubation at HT (33 °C) in the darkness, and (b) 30 days incubation at HT under darkness or 12 h photoperiod, and then transferred to optimum temperature, also under darkness or 12 h photoperiod. Data are means ± standard deviation.

Altogether, the present data suggest that, while temperature cues can markedly condition the germinative behavior of Z. tubispatha seeds, light signals would affect it only when temperature is within the optimal range for germination.

3.3. Effect of Temperature and Light Treatments on Phytohormone Levels

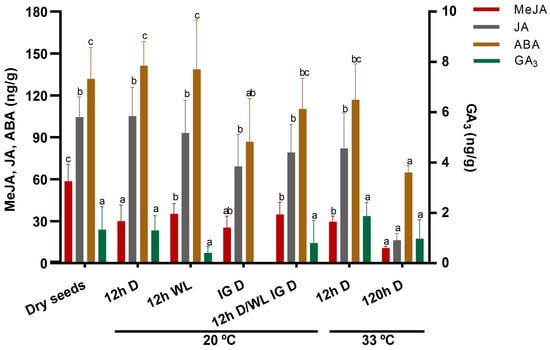

From the four phytohormones determined (ABA, GA3, JA, and MeJA), ABA was the most abundant, followed by JA and MeJA. Surprisingly, the concentration of GA3 was close to the limit of detection in most of the samples tested, making it very difficult to assess to what extent our treatment conditions affected its concentration (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean values of MeJA, JA, ABA (left Y axis), and GA (right Y axis) concentration in Z. tubispatha seeds. The determinations were carried out on seed samples taken from seeds exposed to 20 °C in the darkness (D) or presence of WL (12 h photoperiod), either at 12 h from sowing (treatments 12 h D and 12 h WL, respectively), or at the time of germination beginning (IG) of the darkness control, in both lightning conditions (treatments IG D and 12 h D/WL IG D, respectively). Dry seeds were also tested to evaluate the initial concentration of phytohormones. Statistically homogeneous groups are indicated with the same letter for each phytohormone.

No significant changes in ABA and JA content regarding their initial levels were observed after 12 h hydration at 20 °C, regardless of whether it was performed in darkness or in the presence of light (Figure 4, compare dry seeds with treatments 12 h D and 12 h WL). On the contrary, MeJA showed a significant decline in seeds hydrated under both illumination conditions, although this change was not sufficient to induce germination in either case. When seeds were sampled at the beginning of germination in darkness (treatment 20 °C IG D), the concentration of the three hormones decreased when compared to their initial levels (i.e., in dry seeds), with the difference being statistically significant for ABA and MeJA. Interestingly, in the samples taken at the same time from seeds exposed to a 12 h photoperiod, the concentration of all three hormones was higher than that present in seeds from the dark treatment (Figure 4, treatment 20 °C 12 h D/WL IG D). However, although germination had not yet begun in the light-exposed seeds, this difference regarding the darkness control did not turn out to be statistically significant for any of the phytohormones. On the other hand, it is worth noting that, while neither of the levels of ABA or JA in the light-exposed seeds significantly differed from those found in dry seeds, the concentration of MeJA was lower (p < 0.05); this suggests that, during the hydration period tested, its levels might be subjected to more precise regulation by light signals than those of ABA and JA.

The concentration of the studied phytohormones decreased as the period of incubation at HT (33 °C) increased (Figure 4, treatments 12 h and 120 h), reaching levels yet lower than those found in germinating seeds. This indicates that the inhibition of germination by supraoptimal temperatures does not depend merely on the absolute changes in the levels of these hormones, but that other factors, whether related to their metabolism or not, are also involved.

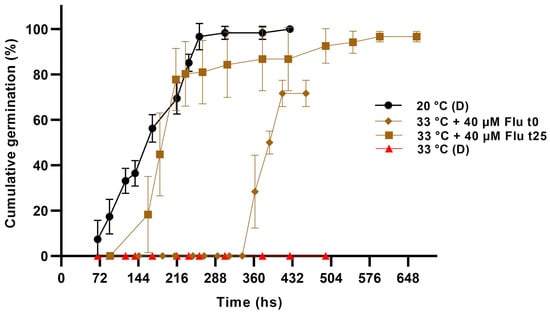

To further explore whether ABA metabolism is important for the inhibition of germination by HT, we added fluridone in the germination plates either at the beginning or after 25 days exposure to 33 °C, under darkness. As shown in Figure 5, when Flu was supplied from the beginning of incubation, germination was not induced until approximately 14 days had elapsed; meanwhile, when it was applied 25 days after exposure to HT, it was induced following a dynamic quite similar to that of seeds germinated at an optimal temperature.

Figure 5.

Cumulative germination of Z. tubispatha seeds at HT (33 °C) in the darkness (D), in the absence or presence of fluridone (Flu) supplied either at the beginning (t0), or at 25 days (t25) from sowing. Since seeds do not germinate at HT, cumulative germination data of the Flu t25 treatment were represented from the addition of the reagent. Germination at optimum temperature (20 °C) without preincubation at HT was included for control. Data are means ± SD.

Taken together, the current results support the idea that changes in ABA sensitivity and/or the relative balance with germination promoters during exposure to high temperatures may be involved in the control of the thermoinhibitory response.

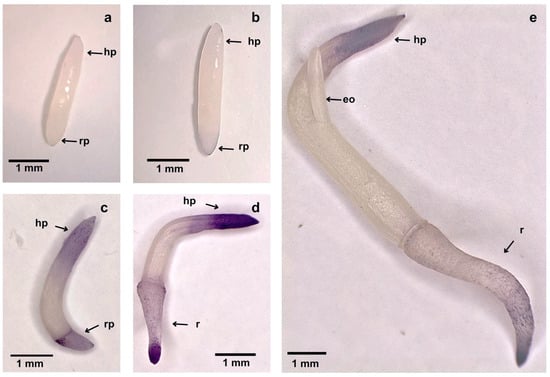

3.4. Alteration of Superoxide Anion Generation in the Embryo

NBT staining of the embryos revealed that HT markedly suppressed O2.− production, particularly in the radical pole (Figure 6a), a phenomenon usually associated with the inhibition of normal root growth (see discussion). When Flu was applied within the first five days after starting HT exposure, the inhibitory effect on O2.− generation by HT persisted in embryos sampled up to 7 days after Flu addition (Figure 6b). In contrast, when NBT staining was performed on embryos supplied with Flu after 25 d of HT exposure, superoxide production was rapidly restored, which coincided with the stimulation of seed germination and further seedling growth (Figure 6c–e).

Figure 6.

NBT staining of representative embryos from seeds sampled after (a) 12d HT (33 °C), (b) 12d HT, with fluridone being added at 5d HT, (c–e) 28, 30, and 34d HT, respectively, with fluridone being added at 25d HT. Nore: eo, eophyll; hp, haustorial pole; r, root; rp, root pole.

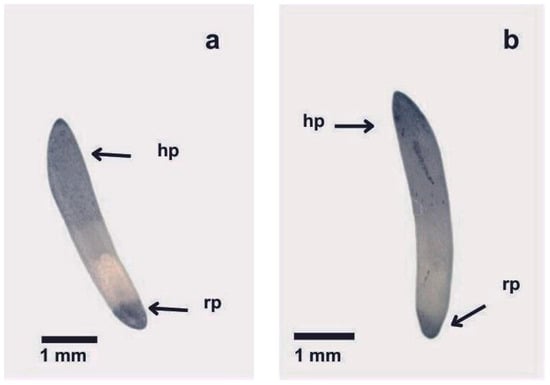

When NBT staining was performed on embryos sampled from photo-inhibited seeds, no major differences regarding color development were observed when compared with embryos sampled at the beginning of germination in darkness (Figure 7). To assess whether embryos from seeds exposed to light had a slower rate of superoxide anion generation than those from the darkness treatment, we repeated the staining with a 1:3 diluted NBT solution and observed color formation every 3–4 min. Although color development was slower with this solution, no clear differences in the degree of staining were detected over time between treatments (Figure S2). This indicates that, unlike thermoinhibition, PISG would not involve the suppression of ROS generation in the root pole of the embryo.

Figure 7.

NBT staining of representative embryos from seeds sampled (a) at the beginning of germination in darkness, and (b) at the same time lapse when exposed to 12 h WL photoperiod. Note: hp, haustorial pole; rp, root pole.

4. Discussion

4.1. Inhibition of Z. tubispatha Seed Germination by Light Cues May Involve a HIR Type of Response

Our data demonstrate that Z. tubispatha seeds have a negative response at high temperatures (HT) and when exposed to white light (WL). These conditions indicated thermoinhibition and photoinhibition. The thermoinhibition is considered to have adaptive value in species that adjust their activity to the winter season, typical of Mediterranean environments with dry summers and wet winters [26,27]. In addition, the photoinhibition of seed germination (PISG) is interpreted as a physiological adaptation to avoid germination on or near the soil surface, where conditions may be unsuitable for seedling establishment. PISG has been documented in several plant families, including amaryllidaceae, and is strongly associated with dark colored seeds of intermediate mass, often occurring in open, disturbed, or dry habitats, in mid-latitude seasonal or arid climates (reviewed in [28]). Most of these aspects agree with the characteristics of Z. tubispatha seeds and the environment in which they develop [1,6,9]. Numerous studies on the germinative behavior of species from model Amaryllidaceae genera such as Allium and Narcissus (e.g., [29,30,31,32,33,34]), as well as from lilioid relatives [35], report the presence of different degrees of PISG. Nevertheless, despite in most cases the responses have been associated with morphological seed attributes, ecological context, and life history traits, the underlying physiological mechanisms remain fairly unexplored.

The finding that white, red, and blue light inhibited Z. tubispatha germination to a similar extent, and that the effect was particularly evident when relatively long doses of irradiation were applied daily (e.g., Figure 1a–c), strongly suggests a HIR-type response [28]. This type of PISG has not been frequently reported, and contrasts with responses found in other species. For example, seed germination in the monocot grass Bromus sterilis was inhibited by exposure to white or red light for 8 h per day. Exposure to far-red light resulted in germination similar to, or less than, that of seeds maintained in darkness. Interestingly, germination could be markedly delayed by exposure to a single pulse of red light following inhibition in darkness, and this effect could be reversed by a single pulse of far-red light, indicating that phytochrome was regulating the response [36]. Although the effect of red-far red treatments could not be tested in our experimental model, the marked difference in the degree of inhibition observed when a single light pulse was given followed by continuous darkness, compared to when it was applied as a daily photoperiod, indicates that the regulation of the light response in Z. tubispatha differs from that of B. sterilis. In subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum ‘Seaton Park’), final germination was drastically reduced by blue and white light, with blue light being significantly more inhibitory than white light. Contrary to what we expected, red light exerted no effects, suggesting that cryptochromes rather than phytochromes were primarily involved [37]. Finally, in several monocot grasses, blue and far-red wavelengths can strongly inhibit germination; however, red light usually counteracts this effect [38,39,40], unlike what we observed in Z. tubispatha.

In a recent research with the CYP accession of Aethionema arabicum (a Brassicaceae from semi-arid habitats), Mérai et al. [17] found that white, blue, red, and far-red light exerted similar inhibitory effects on seed germination, and that the effect was consistent with a HIR type of response. In a forward genetic screen, a mutant—koyash2 (koy2)—that was defective in negative photoblastic germination was identified, which had a nonsense mutation in the gene encoding phytochrome A. The authors demonstrated that PHYA would control both VLFR promotion of germination in semi-dormant seeds, and HIR suppression of germination in nondormant seeds of this species. Gene expression analysis revealed that the PISG was associated with an induction and inhibition of ABA synthesis and degradation, respectively, while opposite trends were observed for genes involved in GA metabolism. In our experimental conditions, pharmacological suppression of ABA synthesis with Flu was able to restore germination of Z. tubispatha seeds in the presence of WL to levels quite similar to those of dark germinated controls (Figure 2). This is in agreement with the hypothesis that the maintenance of adequate ABA levels is required for PISG through HIR type of responses.

Regarding the involvement of GA, it does not seem to play a paramount role in our model system, given both the very low concentrations of GA3 found in the seeds and the absence of significant changes in its levels under the different conditions tested. In the model, species A. thaliana GA3 was less effective in controlling germination when compared to other forms such as GA4 or GA7-isolactone [41]; however, previous trials with Z. tubispatha showed that the exogenous addition of either GA3 or GA4+7 was insufficient to significantly suppress the thermoinhibitory effect of HT [8]. Furthermore, in the same work, we demonstrated the importance of ethylene as compared to GAs in the promotion of germination in this species. In the present research, ethephon supply was able to partially counteract the photoinhibitory effect of WL, suggesting that it also might contribute to the regulation of PISG. Mechanistically, ET was shown to induce germination under different environmental constraints by counteracting the effects of ABA and promoting endosperm rupture by influencing ABA sensitivity [22,42,43]. Ethylene’s action may be linked to tissue localization, as in certain model plant species the enzyme ACC-oxidase (ACO), critical for ET synthesis, was detected almost exclusively in the meristem, and eventually other embryo tissues, of germinating seeds [23,43,44]. Finally, of the remaining phytohormones evaluated, MeJA was the one that followed a similar trend to that of ABA, although the differences in MeJA content among light treatments were mostly not statistically significant (Figure 4). MeJA was shown to inhibit seed germination in several plant species, and its action would involve downregulation of ethylene synthesis (e.g., [45,46]). Nevertheless, in other species it can stimulate germination (e.g., [39]), so its role in the control of germination responses to environmental cues remains controversial. For example, as opposed to the present research, the inhibition of germination by light (and particularly blue wavelengths) in some crop species has been associated with the repression rather than the increment of MeJA production, which in turn would contribute to the maintenance of high ABA levels through the regulation of genes involved in ABA metabolism [39]. Clearly, further research is needed to better understand the role of this phytohormone in the control of germination in photoblastic species.

4.2. Exposure to High Temperatures Condition Germination Responses to Light Cues

As previously reported, germination of Z. tubispatha seeds is thermo-inhibited at temperatures higher than 28 °C [8], and short- or long-term HT incubation periods can delay or accelerate, respectively, germination dynamics after transfer to optimum temperature in the darkness (Figure 3a). In the present work, we found that, while the absence or presence of light during HT exposure did not significantly affect subsequent germinative behavior at optimum temperature, PISG markedly diminished as the period of preincubation at HT increased. Thermal override of light sensitivity has been frequently reported for typical photoblastic species (e.g., [47,48,49,50]). However, this is the first report, to our knowledge, showing that the period of imbibition under thermoinhibitory temperatures can modify the response to light cues at optimum temperature in negative photoblastic seeds.

In some species, temperature dictates whether a seed exhibits negative or neutral photoblastic behavior, providing the most direct link between the two environmental signals. For example, in the annual grass Coelachyrum brevifolium, which is negatively photoblastic, germination in the dark was significantly greater than in the light at lower and moderate temperature regimes (15/25 °C and 20/30 °C), but at higher temperature regimes (25/35 °C) the difference between light treatments was not significant, suggesting that seeds became neutrally photoblastic [51]. In Allium melananthum (an endemic species to southeast Spain), seed germination was hardly affected by temperature under darkness, but in alternating light/darkness regimes, it was suppressed at the extreme temperatures assayed (10 and 25 °C); meanwhile, under mild temperatures (15–20 °C), germination was allowed [34]. Unfortunately, the physiological mechanisms responsible for the observed responses were not assessed.

In positive photoblastic seeds such as Arabidopsis and lettuce, high temperature diminishes the response to light by stimulating the reversion of phyB from its active (Pfr) to its inactive (Pr) form. This suppression of Pfr formation was shown to inhibit the expression of genes involved in the downregulation of ABA/GA balance, thus preventing seed germination [48,49,51,52]. However, in these species, phyB not only acts as a thermosensor, but is also the key photoreceptor regulating photoblastic responses, which does not seem to be the case in Z. tubispatha seeds. Moreover, in Z. tubispatha ABA concentration decreased as the length of the incubation period at supraoptimal temperature increased (Figure 4). The fact that seeds with low ABA levels yet fail to germinate led previous studies to hypothesize that changes in ABA sensitivity, and/or the maintenance of a critical balance between ABA and germination promoter(s) in specific seed tissues, would be essential for thermoinhibition ([8] and references therein). In this context, ethephon (and in particular ethephon + GA, but not GA alone) was able to stimulate germination after a lag period of at least 7–9 days of exposure to HT [8], further supporting the notion that the regulation of the ABA/ethylene balance, probably in specific embryonic tissues, plays a key role in the control of germination by environmental cues in Z. tubispatha seeds.

4.3. ROS Generation at the Embryonic Root Pole Is Differently Affected by Thermoinhibitory or Photoinhibitory Signals

NBT staining of embryos from seeds exposed either to 12 h WL photoperiod or to supraoptimal temperatures revealed that, while the inhibition of seed germination by HT correlated to a marked decline in the production of superoxide anions, particularly at the root pole (Figure 6a), the delaying effect on germination rate exerted by light was not associated with the same phenomenon (Figure 7). This suggests that the mechanism of action differs between the two environmental signals, although in both cases changes in ABA metabolism and/or sensitivity appear to play a central controlling role. In thermo-inhibited seeds, Flu was able to restore O2.− production at the root pole only after several days of HT exposure. This response, in turn, coincided with the timing of germination induction by the reagent, supporting the hypothesis that the HT-generated alteration in ABA balance and/or sensitivity converges on the modulation of ROS production in particular embryonic tissues. The importance of ROS generation at the root pole in controlling seed germination and normal root growth has been demonstrated in this as well as other plant species (e.g., [8,53,54,55]). Particularly, the alteration of O2.− production may affect different regulatory networks, including the activation of Ca2+ and NO signaling cascades, the epigenetic modification of gene expression in different root zones, as well as the alteration of ET, ABA, and GA homeostasis itself. This latter phenomenon highlights the close interaction existing between phytohormone metabolism and signaling, and ROS homeostasis (reviewed in [56]). While the present results also demonstrate the existence of a close relationship between the alteration of phytohormone (and particularly ABA) metabolism and O2.− generation in the regulation of germination by HT in Z. tubispatha, new approaches will be necessary to have a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the action of light cues in this as well as other negative photoblastic species.

4.4. Integration of Thermal and Light Cues Would Favor Germination of Z. tubispatha Seeds Under Optimal Conditions

The dispersal of Z. tubispatha seeds coincides with long periods of high temperatures and photoperiod (spring–summer) and little rainfall. Germination would be hindered or delayed by thermoinhibition, so that the decrease in temperature towards autumn and the increase in rainfall create favorable conditions for germination, growth, and vegetative development of seedlings [9,57]. The delaying effect exerted by long photoperiods on germination induction and rate would help to prevent germination in summer periods when the maximum temperature falls below thermoinhibitory conditions due to local climate variations. Hence, the effectiveness of thermoinhibition along with PISG allows it to be interpreted as a finely tuned regulatory mechanism, where the interaction between adequate light and temperature cues contribute to favor germination and seedling establishment under optimal conditions for this species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121453/s1. Supplementary Figure S1. Experimental setup for the determination of phytohormones in Z. tubispatha seeds. Supplementary Figure S2. Diluted NBT staining of representative Z. tubispatha embryos from seeds exposed to darkness or 12 h WL photoperiod (sampling performed at germination beginning of the darkness control).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.A., H.F.C. and M.L.A.; methodology, M.C.A., H.F.C., M.L.A., M.G.T. and V.S.M.; validation, M.C.A., H.F.C. and M.L.A.; formal analysis, M.C.A., H.F.C., M.G.T. and V.S.M.; investigation, M.C.A., H.F.C. and M.L.A.; resources, M.C.A., H.F.C. and M.G.T.; data curation, M.C.A. and H.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F.C. and M.C.A.; writing—review and editing, H.F.C., M.C.A., M.L.A., M.G.T. and V.S.M.; visualization, M.C.A., H.F.C. and M.L.A.; supervision, M.C.A. and H.F.C.; project administration, M.C.A. and H.F.C.; funding acquisition, M.C.A. and H.F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present research was supported by the Universidad de Buenos Aires (Project UBACyT Mod. I, 20020170100331BA) and the Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (Project 03/A255).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Vilma Manfreda for her contribution to the research design and the Native Plants Greenhause of the Faculty of Agronomy (UNCPBA) for its contribution to carrying out some trials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roitman, G.; Hurrell, J.A. Habranthus. In Flora Rioplatense: Sistemática, Ecología y Etnobotánica de las Plantas Vasculares Rioplatenses; Hurrell, J.A., Ed.; LOLA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009; pp. 115–127. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Leuenberger, S.C. Amaryllidaceae. In Catálogo de las Plantas Vasculares de la República Argentina I; Zuloaga, F., Morrone, O., Eds.; Monographs in Systematic Botany from Missouri Botanical Garden; Missouri Botanical Garden: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1996; Volume 60, pp. 1–332. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino, M.; Farina, J.; Maceira, N. Flores de las Sierras de Tandilia. In Guía Para el Reconocimiento de las Plantas y Sus Visitantes Florales; Ediciones INTA: Balcarce, Argentina, 2017. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Chavarro, C.F.; Cabezas Gutiérrez, M.; Pulido Blanco, V.C.; Celis Ruiz, X.M. Amaryllidaceae: Potential Source of Alkaloids. Biological and Pharmacological Activities. Cienc. Agric. 2020, 17, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza, C.; Germain, P.; Zapperi, G.; Cuevas, Y.; Damiani, M.; Piovan, M.J.; Tizón, R.; Loydi, A. Plantas Nativas de Bahía Blanca y Alrededores: Descubriendo su Historia, Belleza y Magia, 2nd ed.; Tellus: Bahía Blanca, Argentina, 2016. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Streher, N.S. Fenologia da Floração e Biologia Reprodutiva em Geófitas Subtropicais: Estudos de Caso Com Espécies Simpátricas de Amaryllidaceae. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biología, Campinas, Brazil, 2016. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, S.; Rahman, M.; Hassan, M. Taxonomy and reproductive biology of the genus Zephyranthes Herb. (Liliaceae) in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 2018, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.C.; Manfreda, V.T.; Alcaraz, M.L.; Alemano, S.; Causin, H.F. Germination responses in Zephyranthes tubispatha seeds exposed to different thermal conditions and the role of antioxidant metabolism and several phytohormones in their control. Seed Sci. Res. 2022, 32, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.C.; Alcaraz, M.L.; Causin, H.F.; Manfreda, V.T. Aportes al conocimiento morfológico y fisiológico de la reproducción por semillas de Zephyranthes tubispatha (Amaryllidaceae). Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 2023, 58, 7. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Jurado, E.; Chapa-Vargas, L.; Ceroni-Stuva, A.; Dávila-Aranda, P.; Galíndez, G.; Gurvich, D.; León-Lobos, P.; Ordóñez, C.; Ortega-Baes, P.; et al. Seeds photoblastism and its relationship with some plant traits in 136 cacti taxa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 71, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mérai, Z.; Graeber, K.; Wilhelmsson, P.; Ullrich, K.K.; Arshad, W.; Grosche, C.; Tarkowská, D.; Turečková, V.; Strnad, M.; Rensing, S.A.; et al. A novel model plant to study the light control of seed germination. bioRxiv 2019. bioRxiv:470401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, T.L. Seed responses to light. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 2nd ed.; Fenner, M., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Takaki, M. New proposal of classification of seeds based on forms of phytochrome instead of photoblastism. R. Bras. Fisiol. Veg. 2001, 13, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legris, M.; Nieto, C.; Sellaro, R.; Prat, S.; Casal, J.J. Perception and signalling of light and temperature cues in plants. Plant J. 2017, 90, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, J.J.; Qüesta, J.I. Light and temperature cues: Multitasking receptors and transcriptional integrators. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mérai, Z.; Xu, F.; Hajdu, A.; Kozma-Bognár, L.; Dolan, L. Phytochrome A is required for light-inhibited germination of Aethionema arabicum seed. New Phytol. 2025, 247, 2134–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merai, Z.; Xu, F.; Musilek, A.; Ackerl, F.; Khalil, S.; Soto-Jimenez, L.M.; Lalatovic, K.; Klose, C.; Tarkowska, D.; Tureckova, V.; et al. Phytochromes mediate germination inhibition under red, far-red, and white light in Aethionema arabicum. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1584–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merai, Z.; Graeber, K.; Xu, F.; Dona, M.; Lalatovic, K.; Wilhelmsson, P.K.I.; Fernandez-Pozo, N.; Rensing, S.A.; Leubner-Metzger, G.; Mittelsten Scheid, O.; et al. Long days induce adaptive secondary dormancy in the seeds of the Mediterranean plant Aethionema arabicum. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 2893–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkies, A.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Beyond gibberellins and abscisic acid: How ethylene and jasmonates control seed germination. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbineau, F.; Xia, Q.; Bailly, C.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. Ethylene, a key factor in the regulation of seed dormancy. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Gantait, S.; Mitra, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, X. Role of ethylene crosstalk in seed germination and early seedling development: A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbineau, F. Ethylene, a signaling compound involved in seed germination and dormancy. Plants 2024, 13, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinari, G.; Finello, J.; Plaza Rojas, M.; Liberatore, F.; Robert, G.; Otaiza-Gonzalez, S.; Velez, P.; Theumer, M.; Agudelo-Romero, P.; Enet, A.; et al. Autophagy modulates growth and development in the moss Physcomitrium patens. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1052358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W.; InfoStat. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. 2018. Available online: http://www.infostat.com.ar (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Huo, H.; Bradford, K. Molecular and hormonal regulation of thermoinhibition of seed germination. In Advances in Plant Dormancy; Anderson, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Bakhshandeh, A.; Siadat, S.A.; Moradi-Telavat, M.R.; Andarzian, S.B. Quantification of thermoinhibition response of seed germination in different oilseed rape cultivars. Environ. Stress. Crop Sci. 2018, 11, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, A.; Skourti, E.; Mattana, E.; Vandelook, F.; Thanos, C.A. Photoinhibition of seed germination: Occurrence, ecology and phylogeny. Seed Sci. Res. 2017, 27, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, Y.; Kamenetsky, R.; Van Rooyen, M. A comparative study of seed germination of two Allium species from different habitats in the Negev Desert highlands. J. Arid. Environ. 1995, 29, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenetsky, R.; Gutterman, Y. Germination strategies of some Allium species of the subgenus Melanocrommyum from arid zone of Central Asia. J. Arid. Environ. 2000, 45, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.; Draper, D. Seed germination and longevity of autumn-flowering and autumn-seed producing Mediterranean geophytes. Seed Sci. Res. 2012, 22, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz Sanz, J.M.; Copete, M.A.; Ferrandis, P. Environmental Regulation of Embryo Growth, Dormancy Breaking and Germination in Narcissus alcaracensis (Amaryllidaceae), a Threatened Endemic Iberian Daffodil. Am. Midl. Nat. 2013, 169, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz Sanz, J.M.H.; Copete Carreño, E.; Copete Carreño, M.Á.; Ferrandis Gotor, P. Germination ecology of the endemic Iberian daffodil Narcissus radinganorum (Amaryllidaceae). Dormancy induction by cold stratification or desiccation in late stages of embryo growth. For. Syst. 2015, 24, e013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díaz, E.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.J.; Conesa, E.; Franco, J.A.; Vicente, M.J. Germination and morpho-phenological traits of Allium melananthum, a rare species from southeastern Spain. Flora 2018, 249, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelook, F.; Newton, R.J.; Carta, A. Photophobia in Lilioid monocots: Photoinhibition of seed germination explained by seed traits, habitat adaptation and phylogenetic inertia. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.R. An unusual effect of the far-red absorbing form of phytochrome: Photoinhibition of seed germination in Bromus sterilis L. Planta 1982, 155, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Soveral Dias, A.; Grenho, M.G.; Silva Dias, L. Effects of dark or of red, blue or white light on germination of subterranean clover seeds. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2016, 28, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Jacobsen, J.V.; Talbot, M.J.; White, R.G.; Swain, S.M.; Garvin, D.F.; Gubler, F. Grain dormancy and light quality effects on germination in the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, J.V.; Barrero, J.M.; Hughes, T.; Julkowska, M.; Taylor, J.M.; Xu, Q.; Gubler, F. Roles for blue light, jasmonate and nitric oxide in the regulation of dormancy and germination in wheat grain (Triticum aestivum L.). Planta 2013, 238, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.H.; Sechet, J.; Bailly, C.; Leymarie, J.; Corbineau, F. Inhibition of germination of dormant barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grains by blue light as related to oxygen and hormonal regulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkx, M.P.M.; Vermeer, E.; Karssen, C.M. Gibberellins in seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana: Biological activities, identification and effects of light and chilling on endogenous levels. Plant Growth Regul. 1994, 15, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.L.; Bakshi, A.; Binder, B.M. Loss of the ETR1 ethylene receptor reduces the inhibitory effect of far-red light and darkness on seed germination of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Ponnaiah, M.; Thanikathansubramanian, K.; Corbineau, F.; Bailly, C.; Nambara, E.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. Re-localization of hormone effectors is associated with dormancy alleviation by temperature and after-ripening in sunflower seeds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzelli, L.; Coraggio, I.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Ethylene promotes ethylene biosynthesis during pea seed germination by positive feedback regulation of 1-aminocyclo-propane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase. Planta 2000, 211, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kępczyńsk, I.J.; Bialecka, B.; Kępczyńska, E. Ethylene biosynthesis in Amaranthus caudatus seeds in response to methyl jasmonate. Plant Growth Regul. 1999, 28, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norastehnia, A.; Sajedi, R.; Nojavan-Asghari, M. Inhibitory effects of methyl jasmonate on seed germination in maize (Zea mays): Effect on α-amylase activity and ethylene production. Gen. Appl. Plant Physiol. 2007, 33, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, P.N.; Van Staden, J. Thermoinhibition of seed germination. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2003, 69, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.; Imamura, A.; Watanabe, A.; Nakabayashi, K.; Okamoto, M.; Jikumaru, Y.; Hanada, A.; Aso, Y.; Ishiyama, K.; Tamura, N.; et al. High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1368–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, B. Advance in the thermoinhibition of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) seed germination. Plants 2024, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Keblawy, A. Germination response to light and temperature in eight annual grasses from disturbed and natural habitats of an arid Arabian desert. J. Arid. Environ. 2017, 147, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskurewicz, U.; Sentandreu, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Glauser, G.; Lopez-Molina, L. The Arabidopsis endosperm is a temperature-sensing tissue that implements seed thermoinhibition through phyB. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, J.; Vaidya, A.; Cutler, S. Chemical disruption of ABA signaling overcomes high-temperature inhibition of seed germination and enhances seed priming responses. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causin, H.F.; Roqueiro, G.; Petrillo, E.; Láinez, V.; Pena, L.B.; Marchetti, C.F.; Gallego, S.M.; Maldonado, S.B. The control of root growth by reactive oxygen species in Salix nigra Marsh. seedlings. Plant Sci. 2012, 183, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailli, C. The signalling role of ROS in the regulation of seed germination and dormancy. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 3019–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ullah, F.; Zhou, D.-X.; Yi, M.; Zhao, Y. Mechanisms of ROS Regulation of Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Peng, J.; Li, F.; Ali, F.; Wang, Z. Regulation of seed germination: ROS, epigenetic, and hormonal aspects. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 71, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, F.Y.; O’Brien, L.K.; Truco, M.J.; Huo, H.; Sideman, R.; Hayes, R.; Bradford, K.J. Genetic variation for thermotolerance in lettuce seed germination is associated with temperature-sensitive regulation of ethylene response factor1 (ERF1). Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).