Biostimulants in Fruit Crop Production: Impacts on Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

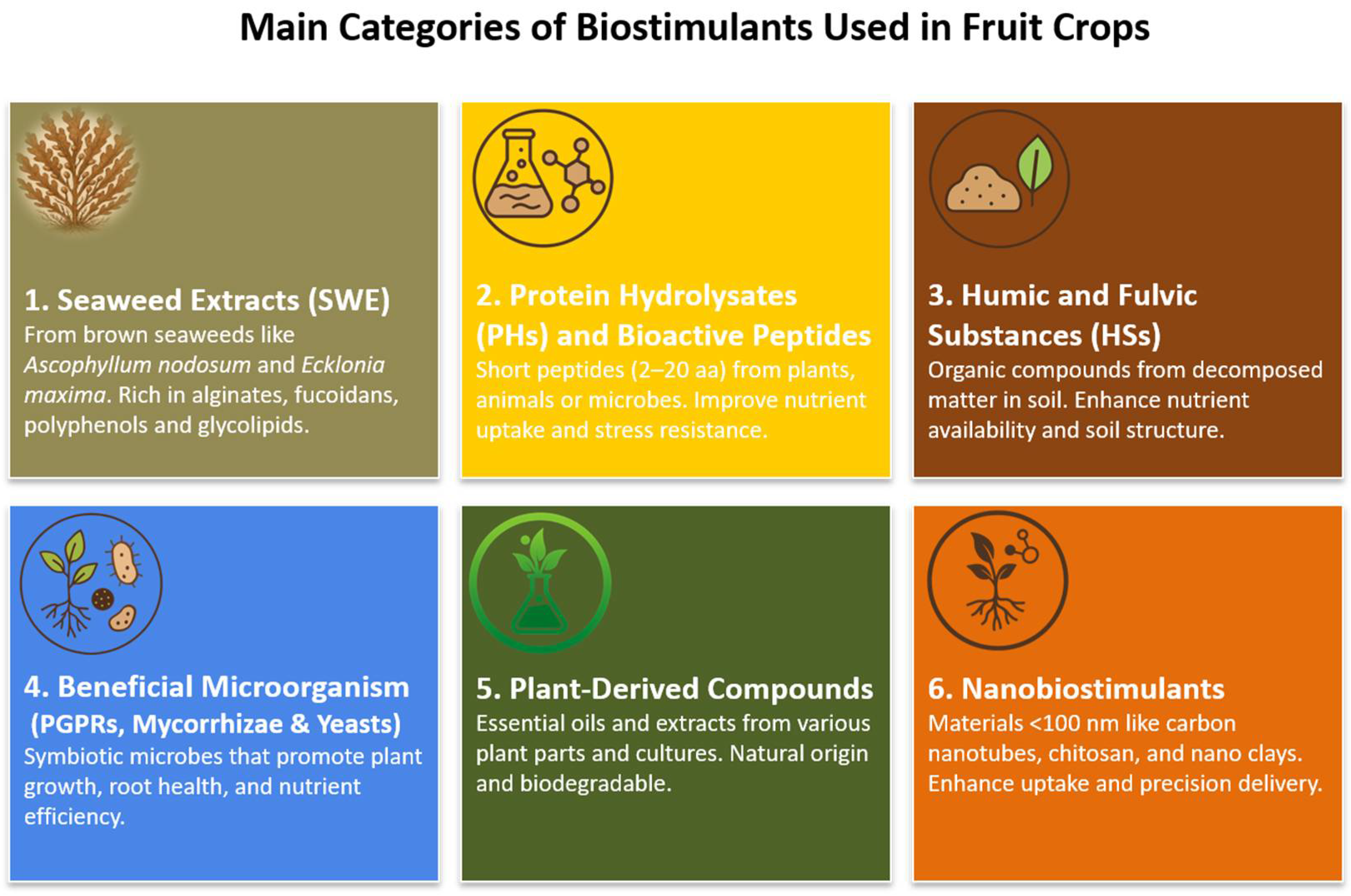

2. Categories of Biostimulants Used in Fruit Crops

2.1. Seaweed Extracts (SWE)

2.2. Protein Hydrolysates (PHs) and Bioactive Peptides

2.3. Humic and Fulvic Substances (HSs)

2.4. Beneficial Microorganisms (PGPRs, Mycorrhizae and Yeast)

2.5. Plant-Derived Compounds (Essential Oils, Botanical Extracts)

2.6. Nanobiostimulants

3. Modes of Action of Biostimulants in Fruit Crops

3.1. Stimulation of Vegetative and Root Growth

3.2. Endogenous Growth Hormone Signaling and Modulation

3.3. Improvement of Nutrient Use Efficiency

3.4. Activation of Antioxidant Defense System

3.5. Effects on Rhizosphere Microbiota and Soil Health

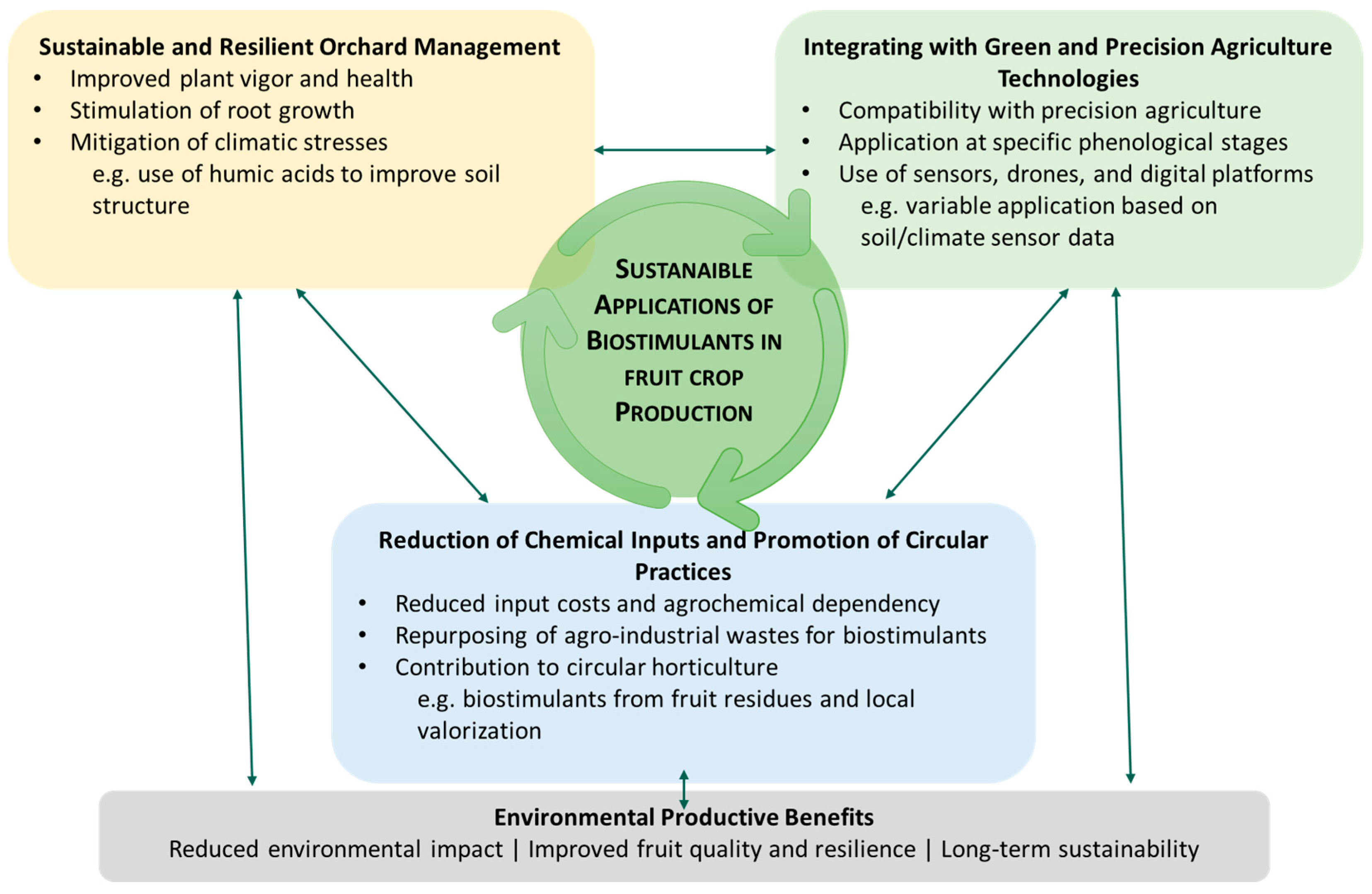

4. Sustainable Applications of Biostimulants in Fruit Crops Production

4.1. Role in Sustainable and Resilient Agricultural Management

4.2. Integration with Green and Precision Agriculture Technologies

4.3. Contribution to Reducing Chemical Inputs, Enhancing Circular Practices and Sustainability

5. Limitations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Estravis-Barcala, M.; Mattera, M.G.; Soliani, C.; Bellora, N.; Opgenoorth, L.; Heer, K.; Arana, M.V. Molecular Bases of Responses to Abiotic Stress in Trees. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3765–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Aini, N.; Kuang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liang, Z. Sensing, Adapting and Thriving: How Fruit Crops Combat Abiotic Stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5584–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Testen, A.L.; Jacobs, J.M.; Ivey, M.L.L. Mitigating Emerging and Reemerging Diseases of Fruit and Vegetable Crops in a Changing Climate. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hao, D.; Jin, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, T.; Su, Y. Internal Ammonium Excess Induces ROS-Mediated Reactions and Causes Carbon Scarcity in Rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gechev, T. Genomics Control of Biostimulant-Induced Stress Tolerance and Crop Yield Enhancement. Plant J. 2025, 123, e70382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant Biostimulants: Definition, Concept, Main Categories and Regulation. Biostimulants Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Tilbury, L.; Daridon, B.; Sukalac, K. General Principles to Justify Plant Biostimulant Claims. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltazar, M.; Correia, S.; Guinan, K.J.; Sujeeth, N.; Bragança, R.; Gonçalves, B. Recent Advances in the Molecular Effects of Biostimulants in Plants: An Overview. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Van Gerrewey, T.; Geelen, D. A Meta-Analysis of Biostimulant Yield Effectiveness in Field Trials. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 836702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, S.; Oliveira, I.; Meyer, A.S.; Gonçalves, B. Biostimulants to Improved Tree Physiology and Fruit Quality: A Review with Special Focus on Sweet Cherry. Agronomy 2022, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009; European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying Down Rules on the Making Available on the Market of EU Fertilising Products and Amending. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019.

- Sujeeth, N.; Petrov, V.; Guinan, K.J.; Rasul, F.; O’Sullivan, J.T.; Gechev, T.S. Current Insights into the Molecular Mode of Action of Seaweed-Based Biostimulants and the Sustainability of Seaweeds as Raw Material Resources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergosien, N.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Connan, S.; Hennequart, F.; Brébion, J. Mini-Review: Brown Macroalgae as a Promising Raw Material to Produce Biostimulants for the Agriculture Sector. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchev, P.; van der Meer, T.; Sujeeth, N.; Verlee, A.; Stevens, C.V.; Van Breusegem, F.; Gechev, T. Molecular Priming as an Approach to Induce Tolerance against Abiotic and Oxidative Stresses in Crop Plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 40, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidbakhshfard, M.A.; Sujeeth, N.; Gupta, S.; Omranian, N.; Guinan, K.J.; Brotman, Y.; Nikoloski, Z.; Fernie, A.R.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. A Biostimulant Obtained from the Seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum Protects Arabidopsis thaliana from Severe Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Biostimulants Industry Council. Recent Insights into the Mode of Action of Seaweed-Based Plant Biostimulants; EBIC: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guinan, K.J.; Sujeeth, N.; Copeland, R.B.; Jones, P.W.; O’Brien, N.M.; Sharma, S.; Prouteau, P.F.J.; O’Sullivan, J.T. Discrete Roles for Extracts of Ascophyllum nodosum in Enhancing Plant Growth and Tolerance to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Acta Hortic. 2013, 1009, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Basile, B. Rate and Timing of Application of Biostimulant Substances to Enhance Fruit Tree Tolerance toward Environmental Stresses and Fruit Quality. Agronomy 2022, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, F.; Gupta, S.; Olas, J.J.; Gechev, T.; Sujeeth, N.; Mueller-Roeber, B. Priming with a Seaweed Extract Strongly Improves Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staykov, N.S.; Angelov, M.; Petrov, V.; Minkov, P.; Kanojia, A.; Guinan, K.J.; Alseekh, S.; Fernie, A.R.; Sujeeth, N.; Gechev, T.S. An Ascophyllum nodosum-Derived Biostimulant Protects Model and Crop Plants from Oxidative Stress. Metabolites 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestili, F.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Pucci, A.; Bonini, P.; Canaguier, R.; Colla, G. Protein Hydrolysate Stimulates Growth in Tomato Coupled with N-Dependent Gene Expression Involved in N Assimilation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Canaguier, R.; Svecova, E.; Cardarelli, M. Biostimulant Action of a Plant-Derived Protein Hydrolysate Produced through Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Hoagland, L.; Ruzzi, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Biostimulant Action of Protein Hydrolysates: Unraveling Their Effects on Plant Physiology and Microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malécange, M.; Sergheraert, R.; Teulat, B.; Mounier, E.; Lothier, J.; Sakr, S. Biostimulant Properties of Protein Hydrolysates: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Agyei, D.; Jeevanandam, J.; Danquah, M.K. Bio-Active Peptides: Role in Plant Growth and Defense. In Natural Bio-Active Compounds: Volume 3: Biotechnology, Bioengineering, and Molecular Approaches; Akhtar, M.S., Swamy, M.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-981-13-7438-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, K. Sulfated Peptides: Key Players in Plant Development, Growth, and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1474111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurartieri, M.; Lucchi, A.; Cavani, L. Effects of the Rate of Protein Hydrolysis and Spray Concentration on Growth of Potted Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) Plants. Acta Hortic. 2002, 594, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrado, J.; Escudero-Gilete, M.L.; Friaza, V.; García-Martínez, A.; González-Miret, M.L.; Bautista, J.D.; Heredia, F.J. Enzymatic Vegetable Extract with Bio-Active Components: Influence of Fertiliser on the Colour and Anthocyanins of Red Grapes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2310–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Kyriacou, M.C.; De Pascale, S. Foliar Applications of a Legume-Derived Protein Hydrolysate Elicit Dose-Dependent Increases of Growth, Leaf Mineral Composition, Yield and Fruit Quality in Two Greenhouse Tomato Cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 226, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggio, F.; Trevisan, S.; Manoli, A.; Ruperti, B.; Quaggiotti, S. Systematic Investigation of the Effects of a Novel Protein Hydrolysate on the Growth, Physiological Parameters, Fruit Development and Yield of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L., cv Sauvignon Blanc) under Water Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, A.V.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Buffagni, V.; Senizza, B.; Pii, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Lucini, L. Foliar Application of Different Vegetal-Derived Protein Hydrolysates Distinctively Modulates Tomato Root Development and Metabolism. Plants 2021, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, O.Y.A.; Chang, J.; Li, J.; van Lith, W.; Kuramae, E.E. Unraveling the Impact of Protein Hydrolysates on Rhizosphere Microbial Communities: Source Matters. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 196, 105307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peli, M.; Ambrosini, S.; Sorio, D.; Pasquarelli, F.; Zamboni, A.; Varanini, Z. The Soil Application of a Plant-Derived Protein Hydrolysate Speeds up Selectively the Ripening-Specific Processes in Table Grape. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, A.G.; Danchenko, N.N.; Demin, V.V.; Artemyeva, Z.S.; Kogut, B.M. Humic Substances: Hypotheses and Reality (a Review). Eurasian Soil Sci. 2021, 54, 1826–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffia, A.; Oliva, M.; Marra, F.; Mallamaci, C.; Nardi, S.; Muscolo, A. Humic Substances: Bridging Ecology and Agriculture for a Greener Future. Agronomy 2025, 15, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampong, K.; Thilakaranthna, M.S.; Gorim, L.Y. Understanding the Role of Humic Acids on Crop Performance and Soil Health. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 848621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoun, A.M.M.A.; El-Enin, M.M.A.; Mancy, A.G.; Sheta, M.H.; Shaaban, A. Integrative Soil Application of Humic Acid and Foliar Plant Growth Stimulants Improves Soil Properties and Wheat Yield and Quality in Nutrient-Poor Sandy Soil of a Semiarid Region. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y. The Impact of Humic Acid Fertilizers on Crop Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency: A Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wu, G.; Chen, X.; Gruda, N.; Li, X.; Dong, J.; Duan, Z. Dose-Dependent Application of Straw-Derived Fulvic Acid on Yield and Quality of Tomato Plants Grown in a Greenhouse. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 736613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, R.; Jiang, Z.; Li, H.; Xue, X. The Combined Application of Urea and Fulvic Acid Regulates Apple Tree Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism and Improves Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Zhu, S. Potassium Fulvic Acid Alleviates Salt Stress of Citrus by Regulating Rhizosphere Microbial Community, Osmotic Substances and Enzyme Activities. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1161469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xue, X.; Nie, P.; Lu, N.; Wang, L. Fulvic Acid Alleviates Cadmium-Induced Root Growth Inhibition by Regulating Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Carbon–Nitrogen Metabolism in Apple Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1370637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.T.; Patti, A.F.; Little, K.R.; Brown, A.L.; Jackson, W.R.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Chapter Two—A Meta-Analysis and Review of Plant-Growth Response to Humic Substances: Practical Implications for Agriculture. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 124, pp. 37–89. ISBN 0065-2113. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, H.U.; Allevato, E.; Vaccari, F.P.; Stazi, S.R. Biochar Aged or Combined with Humic Substances: Fabrication and Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment-a Review. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Rana, K.L.; Yadav, N.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, A.; Meena, V.S.; Singh, B.; Chauhan, V.S.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Saxena, A.K. Rhizospheric Microbiomes: Biodiversity, Mechanisms of Plant Growth Promotion, and Biotechnological Applications for Sustainable Agriculture. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Agricultural Sustainability: From Theory to Practices; Kumar, A., Meena, V.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 19–65. ISBN 978-981-13-7553-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.; Gao, D.; Wu, F. Common Mycorrhizal Network: The Predominant Socialist and Capitalist Responses of Possible Plant–Plant and Plant–Microbe Interactions for Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1183024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fernández, M.; Cordero-Bueso, G.; Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Cantoral, J.M. Culturable Yeasts as Biofertilizers and Biopesticides for a Sustainable Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2021, 10, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Adl, S.M. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and Their Action Mechanisms in Availability of Nutrients to Plants. In Phyto-Microbiome in Stress Regulation; Kumar, M., Kumar, V., Prasad, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 147–203. ISBN 978-981-15-2576-6. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, M.; Bodhankar, S.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, P.; Singh, J.; Nain, L. PGPR Mediated Alterations in Root Traits: Way toward Sustainable Crop Production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 618230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.F.; Nakabonge, G.; Ssekandi, J.; Founoune-Mboup, H.; Apori, S.O.; Ndiaye, A.; Badji, A.; Ngom, K. Roles of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soil Fertility: Contribution in the Improvement of Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties of the Soil. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 723892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choińska, R.; Piasecka-Jóźwiak, K.; Chabłowska, B.; Dumka, J.; Łukaszewicz, A. Biocontrol Ability and Volatile Organic Compounds Production as a Putative Mode of Action of Yeast Strains Isolated from Organic Grapes and Rye Grains. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castoria, R.; De Curtis, F.; Lima, G.; De Cicco, V. β-1,3-Glucanase Activity of Two Saprophytic Yeasts and Possible Mode of Action as Biocontrol Agents against Postharvest Diseases. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997, 12, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimotho, R.N.; Maina, S. Unraveling Plant–Microbe Interactions: Can Integrated Omics Approaches Offer Concrete Answers? J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 1289–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabar, S.A.; Kotroczó, Z.; Takács, T.; Biró, B. Evaluating the Efficacy of Selected Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms in Optimizing Plant Growth and Soil Health in Diverse Soil Types. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Siraj, M.; Zaman, W. Molecular Communication of Microbial Plant Biostimulants in the Rhizosphere under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorente, S.E.; Martí-Guillén, J.M.; Pedreño, M.Á.; Almagro, L.; Sabater-Jara, A.B. Higher Plant-Derived Biostimulants: Mechanisms of Action and Their Role in Mitigating Plant Abiotic Stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, J.; Carvalho, A.; Rodrigues, M.Â.; Correia, C.M.; Lima-Brito, J. Assessing the Effect of Plant Biostimulants and Nutrient-Rich Foliar Sprays on Walnut Nucleolar Activity and Protein Content (Juglans regia L.). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudu, C.K.; Dey, A.; Pandey, D.K.; Panwar, J.S.; Nandy, S. Chapter 8—Role of Plant Derived Extracts as Biostimulants in Sustainable Agriculture: A Detailed Study on Research Advances, Bottlenecks and Future Prospects. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Singh, H.B., Vaishnav, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 159–179. ISBN 978-0-323-85579-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-García, A.I.; de la Hoz, K.S.; Zalacain, A.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Effect of Vine Foliar Treatments on the Varietal Aroma of Monastrell Wines. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglia, D.; Pezzolla, D.; Gigliotti, G.; Torre, L.; Bartucca, M.L.; Del Buono, D. The Opportunity of Valorizing Agricultural Waste, through Its Conversion into Biostimulants, Biofertilizers, and Biopolymers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jíménez-Arias, D.; Morales-Sierra, S.; Silva, P.; Carrêlo, H.; Gonçalves, A.; Ganança, J.F.; Nunes, N.; Gouveia, C.S.S.; Alves, S.; Borges, J.P.; et al. Encapsulation with Natural Polymers to Improve the Properties of Biostimulants in Agriculture. Plants 2023, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Ortega-Ortíz, H.; Morales-Díaz, A.B.; González-Morales, S.; Morelos-Moreno, Á.; Cabrera-De la Fuente, M.; Sandoval-Rangel, A.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. Nanoparticles and Nanomaterials as Plant Biostimulants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, A.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Sathyanarayanan, H.; Gnanajothi, K.; T, S. Nanomaterials as Potential Plant Growth Modulators: Applications, Mechanism of Uptake, and Toxicity: A Comprehensive Review. BioNanoScience 2025, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Parveen, M.; Naz, G.; Sharif, H.M.A.; Nazim, M.; Aslam, S.; Hussain, A.; Rahimi, M.; Alamer, K.H. Enhancing Physio-Biochemical Characteristics in Okra Genotypes through Seed Priming with Biogenic Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized from Halophytic Plant Extracts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakham, W.; Sarmah, A.K.; Maensiri, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Nanopriming Technology for Enhancing Germination and Starch Metabolism of Aged Rice Seeds Using Phytosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Manikandan, S.K.; Hasnain, M.; Klironomos, J.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; El-Keblawy, A. Halophyte-Derived Nanoparticles and Biostimulants for Sustainable Crop Production under Abiotic Stresses. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, D.; Mazo, C.H.; Bauer, C.M.; da Silva Gomes, L.; Teodoro, E.B.; Mazzarino, L.; da Rocha Veleirinho, M.B.; Moura e Silva, S.; Maraschin, M. A Novel Biostimulant from Chitosan Nanoparticles and Microalgae-Based Protein Hydrolysate: Improving Crop Performance in Tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesaheb, K.S.; Subramanian, S.; Boominathan, P.; Thenmozhi, S.; Gnanachitra, M. Bio-Stimulant in Improving Crop Yield and Soil Health. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 458–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Subahan, G.M.; Sharma, S.; Singh, G.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, U.; Kumar, V. Enhancing Horticultural Sustainability in the Face of Climate Change: Harnessing Biostimulants for Environmental Stress Alleviation in Crops. Stresses 2025, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ugurlar, F. Non-Microbial Biostimulants for Quality Improvement in Fruit and Leafy Vegetables. In Growth Regulation and Quality Improvement of Vegetable Crops: Physiological and Molecular Features; Ahammed, G.J., Zhou, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 457–494. ISBN 978-981-96-0169-1. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, A.; Ali, M.; Qadir, M.; Karthikeyan, R.; Singh, Z.; Khangura, R.; Di Gioia, F.; Ahmed, Z.F. Enhancing Crop Resilience by Harnessing the Synergistic Effects of Biostimulants against Abiotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1276117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Franzoni, G.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants Application in Horticultural Crops under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Joel, J.M.; Puthur, J.T. Biostimulants: The Futuristic Sustainable Approach for Alleviating Crop Productivity and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Abou Jaoudé, R.; Ficca, A.G.; Ruzzi, M. Effect of Microbial Plant Biostimulants on Fruit and Vegetable Quality: Current Research Lines and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1251544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longnecker, N. Nutrient Deficiencies and Vegetative Growth; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994; pp. 137–172. ISBN 978-1-003-21025-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, Y.-L. Regulation of Cell Division and Expansion by Sugar and Auxin Signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, N.R.; Bhatt, A.; Suleiman, M.K. Physiology of Growth and Development in Horticultural Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 1-040-11626-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, A.K.; Montessoro, P.D.; Fusaro, A.F.; Araújo, B.G.; Hemerly, A.S. Plant CDKs—Driving the Cell Cycle through Climate Change. Plants 2021, 10, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, J.G.; Thaker, V.S. Cyclin Dependent Kinases and Their Role in Regulation of Plant Cell Cycle. Biol. Plant. 2011, 55, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterisi, S.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Buffagni, V.; Zuluaga, M.Y.A.; Ciriello, M.; Formisano, L.; El-Nakhel, C.; Cardarelli, M.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; et al. Unravelling the Biostimulant Activity of a Protein Hydrolysate in Lettuce Plants under Optimal and Low N Availability: A Multi-Omics Approach. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marowa, P.; Ding, A.; Kong, Y. Expansins: Roles in Plant Growth and Potential Applications in Crop Improvement. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Qi, D.; Fang, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Genome-Wide Characterization of the Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase Family Genes and Their Response to Plant Hormone in Sugar Beet. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant Biostimulants to Enhance Abiotic Stress Resilience in Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P. Can Biostimulants Enhance Plant Resilience to Heat and Water Stress in the Mediterranean Hotspot? Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Hu, S.; Jiang, L. Vacuole Biogenesis in Plants: How Many Vacuoles, How Many Models? Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembada, A.A.; Faizal, A.; Sulistyawati, E. Photosynthesis Efficiency as Key Factor in Decision-Making for Forest Design and Redesign: A Systematic Literature Review. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostocki, A.; Wieczorek, D.; Pipiak, P.; Ławińska, K. Use of Biostimulants in Energy Crops as a New Approach for the Improvement of Performance Sequestration CO2. Energies 2024, 17, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, W.F.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Gornik, K.; Ali, H.M.; Salem, M.Z. Vegetative Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality of Guava (Psidium guajava L.) cv. Maamoura as Affected by Some Biostimulants. Bioresources 2021, 16, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nephali, L.; Piater, L.A.; Dubery, I.A.; Patterson, V.; Huyser, J.; Burgess, K.; Tugizimana, F. Biostimulants for Plant Growth and Mitigation of Abiotic Stresses: A Metabolomics Perspective. Metabolites 2020, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.M.; Sultana, F.; Khan, S.; Nayeema, J.; Mostafa, M.; Ferdus, H.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Mostofa, M.G. Carrageenans as Biostimulants and Bio-Elicitors: Plant Growth and Defense Responses. Stress Biol. 2024, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, W.F.A.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Głuszek, S.; Górnik, K.; Anjum, M.A.; Saleh, A.A.; Abada, H.S.; Awad, R.M. Effect of Some Biostimulants on the Vegetative Growth, Yield, Fruit Quality Attributes and Nutritional Status of Apple. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppelsa, S.; Kelderer, M.; Casera, C.; Bassi, M.; Robatscher, P.; Matteazzi, A.; Andreotti, C. Foliar Applications of Biostimulants Promote Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Strawberry Plants Grown under Nutrient Limitation. Agronomy 2019, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saif, A.M.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Saad, R.M.; Mosa, W.F.A. Amino Acids as Safe Biostimulants to Improve the Vegetative Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality of Peach. BioResources 2024, 19, 5978–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.F.; Górnik, K.; Ayoub, A.; Abada, H.S.; Mosa, W.F.A. Performance of Mango Trees under the Spraying of Some Biostimulants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.F.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Mosa, W.F.A. The Role of Some Biostimulants in Improving the Productivity of Orange. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.K.; Layek, J.; Yadav, A.; Das, S.K.; Rymbai, H.; Mandal, S.; Sahana, N.; Bhutia, T.L.; Devi, E.L.; Patel, V.B.; et al. Improvement of Rooting and Growth in Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) Cuttings with Organic Biostimulants. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubser, J.; Le Maitre, N.C.; Claassens, A.P.; Coetzee, B.; Kossmann, J.; Hills, P.N. BC204, a Citrus-Based Plant Extract, Stimulates Plant Growth in Arabidopsis thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum through Regulation and Signaling. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alonso, A.; Yepes-Molina, L.; Guarnizo, A.L.; Carvajal, M. Modification of Gene Expression of Tomato Plants through Foliar Flavonoid Application in Relation to Enhanced Growth. Genes 2023, 14, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, L.; Figueroa, C.R.; Valdenegro, M. Recent Advances in Hormonal Regulation and Cross-Talk during Non-Climacteric Fruit Development and Ripening. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtalakshmi, M.; Saraswathy, S.; Muthulakshmi, S.; Venkatesan, K.; Anitha, T. A Review on Exploring the Efficiency of Plant Hormones on Fruitfulness of Perishables. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.; Lubyanov, A.; Yakhin, I.; Brown, P. Biostimulants in Plant Science: A Global Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, A.R.d.C.; Ambrósio, A.d.S.; Resende, A.d.J.R.; Santos, B.R.; Nadal, M.C. From Cell Division to Stress Tolerance: The Versatile Roles of Cytokinins in Plants. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 94, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, J.; Truba, M.; Vasileva, V. The Impact of Auxin and Cytokinin on the Growth and Development of Selected Crops. Agriculture 2023, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Wilkinson, E.G.; Sageman-Furnas, K.; Strader, L.C. Auxin and Abiotic Stress Responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 7000–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhuang, S.; Zhang, W. Advances in Plant Auxin Biology: Synthesis, Metabolism, Signaling, Interaction with Other Hormones, and Roles under Abiotic Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, J.-J.; Zhang, J.-Z. Aux/IAA Gene Family in Plants: Molecular Structure, Regulation, and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, D.; Chang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, Y. Advances in the Study of Auxin Early Response Genes: Aux/IAA, GH3, and SAUR. Crop J. 2024, 12, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-B.; Xie, Z.-Z.; Hu, C.-G.; Zhang, J.-Z. A Review of Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yahaya, B.S.; Li, J.; Wu, F. Enigmatic Role of Auxin Response Factors in Plant Growth and Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1398818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtaczka, P.; Ciarkowska, A.; Starzynska, E.; Ostrowski, M. The GH3 Amidosynthetases Family and Their Role in Metabolic Crosstalk Modulation of Plant Signaling Compounds. Phytochemistry 2022, 194, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Gray, W.M. SAUR Proteins as Effectors of Hormonal and Environmental Signals in Plant Growth. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stortenbeker, N.; Bemer, M. The SAUR Gene Family: The Plant’s Toolbox for Adaptation of Growth and Development. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J. Mining and Evolution Analysis of Lateral Organ Boundaries Domain (LBD) Genes in Chinese White Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri). BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Hou, Z.; Liao, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Su, W.; Cai, Z.; Fang, Y.; Aslam, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of LBD Transcription Factor Genes in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Křeček, P.; Skůpa, P.; Libus, J.; Naramoto, S.; Tejos, R.; Friml, J.; Zažímalová, E. The PIN-FORMED (PIN) Protein Family of Auxin Transporters. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovrizhnykh, V.; Mustafin, Z.; Bagautdinova, Z. The Auxin Signaling Pathway to Its PIN Transporters: Insights Based on a Meta-Analysis of Auxin-Induced Transcriptomes. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2021, 25, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant Properties of Seaweed Extracts in Plants: Implications towards Sustainable Crop Production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Cytokinins. Arab. Book 2014, 12, e0168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E.; Street, I.H.; Kieber, J.J. Cytokinin and the Cell Cycle. SI Cell Signal. Gene Regul. 2014, 21, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cortijo, S.; Korsbo, N.; Roszak, P.; Schiessl, K.; Gurzadyan, A.; Wightman, R.; Jönsson, H.; Meyerowitz, E. Molecular Mechanism of Cytokinin-Activated Cell Division in Arabidopsis. Science 2021, 371, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skylar, A.; Hong, F.; Chory, J.; Weigel, D.; Wu, X. STIMPY Mediates Cytokinin Signaling during Shoot Meristem Establishment in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Development 2010, 137, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, G.; Tian, W.; Ling, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, T.; Sang, X.; Zhu, X.; He, G.; et al. The WOX9-WUS Modules Are Indispensable for the Maintenance of Stem Cell Homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2024, 120, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Lai, N.; Kisiala, A.B.; Emery, R.J.N. Isopentenyltransferases as Master Regulators of Crop Performance: Their Function, Manipulation, and Genetic Potential for Stress Adaptation and Yield Improvement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Prakash, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. Killing Two Birds with a Single Stone—Genetic Manipulation of Cytokinin Oxidase/Dehydrogenase (CKX) Genes for Enhancing Crop Productivity and Amelioration of Drought Stress Response. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 941595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Ortiz, S.; Balderas-Ruíz, K.A.; López-Bucio, J.S.; López-Bucio, J.; Flores, C.; Galindo, E.; Serrano-Carreón, L.; Guevara-García, Á.A. A Bacillus velezensis Strain Improves Growth and Root System Development in Arabidopsis Thaliana through Cytokinin Signaling. Rhizosphere 2023, 28, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Camba, R.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N.; Vielba, J.M. Plant Development and Crop Yield: The Role of Gibberellins. Plants 2022, 11, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Y.; Song, R.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Gao, J. The Roles of Gibberellins in Regulating Leaf Development. Plants 2023, 12, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.; Ori, N. Mechanisms of Cross Talk between Gibberellin and Other Hormones. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbussche, F.; Fierro, A.C.; Wiedemann, G.; Reski, R.; Van Der Straeten, D. Evolutionary Conservation of Plant Gibberellin Signalling Pathway Components. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C. Understanding Gibberellic Acid Signaling—Are We There Yet? Growth Dev. 2008, 11, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C. Gibberellin Signaling in Plants—The Extended Version. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 2, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.; Imran, F.; Iqbal Khan, R.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Rafique, T.; Jameel Khan, M.; Taban, S.; Danish, S.; Datta, R. Gibberellic Acid Induced Changes on Growth, Yield, Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase and Peroxidase in Fruits of Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.). Horticulturae 2020, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.A.; Zakari, S.A.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, L.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, F. Abiotic Stresses Intervene with ABA Signaling to Induce Destructive Metabolic Pathways Leading to Death: Premature Leaf Senescence in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhilasha, A.; Choudhury, S.R. Molecular and Physiological Perspectives of Abscisic Acid Mediated Drought Adjustment Strategies. Plants 2021, 10, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. Core Components of Abscisic Acid Signaling and Their Post-Translational Modification. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 895698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, K.; Zhou, H.; Yan, X.; Zhan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Song, C.-P. ABI5 Modulates Seed Germination via Feedback Regulation of the Expression of the PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA Receptor Genes. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Miao, Y.; Guo, H. Leaf Senescence: Progression, Regulation, and Application. Mol. Hortic. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E. Ethylene and the Regulation of Plant Development. BMC Biol. 2012, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Khan, N.A.; Ferrante, A.; Trivellini, A.; Francini, A.; Khan, M.I.R. Ethylene Role in Plant Growth, Development and Senescence: Interaction with Other Phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alvi, A.F.; Khan, N.A. Role of Ethylene in the Regulation of Plant Developmental Processes. Stresses 2024, 4, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M.; Poel, B.V. de 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Oxidase (ACO): The Enzyme That Makes the Plant Hormone Ethylene. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alvi, A.F.; Saify, S.; Iqbal, N.; Khan, N.A. The Ethylene Biosynthetic Enzymes, 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate (ACC) Synthase (ACS) and ACC Oxidase (ACO): The Less Explored Players in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Formisano, L.; Ciriello, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Luziatelli, F.; Ruzzi, M.; Ficca, A.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Natural Biostimulants as Upscale Substitutes to Synthetic Hormones for Boosting Tomato Yield and Fruits Quality. Italus Hortus 2021, 28, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Morais, M.C.; Sequeira, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Guedes, F.; Silva, A.P.; Aires, A. Quality Preservation of Sweet Cherry cv. “staccato” by Using Glycine-Betaine or Ascophyllum nodosum. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, T.; Silva, A.P.; Ribeiro, C.; Carvalho, R.; Aires, A.; Vicente, A.A.; Gonçalves, B. Ecklonia maxima and Glycine–Betaine-Based Biostimulants Improve Blueberry Yield and Quality. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, M.; El Chami, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Ciriello, M.; Bonini, P.; Erice, G.; Cirino, V.; Basile, B.; Corrado, G.; Choi, S.; et al. Plant Biostimulants as Natural Alternatives to Synthetic Auxins in Strawberry Production: Physiological and Metabolic Insights. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1337926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishchala; Sharma, A.; Banyal, A.; Shivandu, S.K.; Sharma, I. Use of Biostimulants in Fruit Crop Enhancement. Biot. Res. Today 2024, 6, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Nardi, S.; Cardarelli, M.; Ertani, A.; Lucini, L.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Protein Hydrolysates as Biostimulants in Horticulture. Biostimulants Hortic. 2015, 196, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, G.; Petry, C.; Silveira, D.; Trentin, T.; Turmina, A.; Chiomento, J. Use of Biostimulants in Fruiting Crops’ Sustainable Management: A Narrative Review. Laddee 2023, 4, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasković, I.; Popović, L.; Pongrac, P.; Polić Pasković, M.; Kos, T.; Jovanov, P.; Franić, M. Protein Hydrolysates—Production, Effects on Plant Metabolism, and Use in Agriculture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Jiménez, J.L.; de Barros Montebianco, C.; Olivares, F.L.; Canellas, L.P.; Barreto-Bergter, E.; Rosa, R.C.C.; Vaslin, M.F.S. Passion Fruit Plants Treated with Biostimulants Induce Defense-Related and Phytohormone-Associated Genes. Plant Gene 2022, 30, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.-E.; Teo, W.F.; Teoh, E.Y.; Tan, B.C. Microbiome Engineering and Plant Biostimulants for Sustainable Crop Improvement and Mitigation of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Discov. Food 2022, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, M.; Xie, X. Cross-Talks between Macro- and Micronutrient Uptake and Signaling in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giehl, R.F.H.; Wirén, N. von Root Nutrient Foraging. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Ahmadi, S.H.; Amelung, W.; Athmann, M.; Ewert, F.; Gaiser, T.; Gocke, M.I.; Kautz, T.; Postma, J.; Rachmilevitch, S.; et al. Nutrient Deficiency Effects on Root Architecture and Root-to-Shoot Ratio in Arable Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1067498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, A.; Srinivasan, R. The Role of Plant Roots in Nutrient Uptake and Soil Health. Plant Sci. Arch. 2021, 6, 5–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Li, S. Root Penetration Ability and Plant Growth in Agroecosystems. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 183, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Rayirath, U.P.; Subramanian, S.; Jithesh, M.N.; Rayorath, P.; Hodges, D.M.; Critchley, A.T.; Craigie, J.S.; Norrie, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed Extracts as Biostimulants of Plant Growth and Development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, D.C.; Birthal, P.S.; Kumara, T.M.K. Biostimulants for Sustainable Development of Agriculture: A Bibliometric Content Analysis. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughunth, R.J.; Velmurugan, S.; Mohanalakshmi, M.; Vanitha, K. A Review of Seaweed Extract’s Potential as a Biostimulant to Enhance Growth and Mitigate Stress in Horticulture Crops. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L.; Aguiar, N.O.; Jones, D.L.; Nebbioso, A.; Mazzei, P.; Piccolo, A. Humic and Fulvic Acids as Biostimulants in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural Uses of Plant Biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Pradhan, B.; Kumar, V.; Singh, H.; Nath, D.; Kamat, D.; Kumar, M. Exploring the Role of Biostimulants in Sustainable Agriculture. Curr. Sci. 2025, 128, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Ding, M.; Xu, F.; Yan, F.; Kinoshita, T.; Zhu, Y. Plasma Membrane H+-ATPases in Mineral Nutrition and Crop Improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 978–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L. Physiological Responses to Humic Substances as Plant Growth Promoter. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.H.; Rehman, H.M.; Akhtar, T.; Alsamadany, H.; Hamooh, B.T.; Mujtaba, T.; Daur, I.; Al Zahrani, Y.; Alzahrani, H.A.S.; Ali, S.; et al. Humic Substances: Determining Potential Molecular Regulatory Processes in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, L.; Tomasi, N.; Cesco, S.; Varanini, Z.; Pinton, R. Humic Substances Contribute to Plant Iron Nutrition Acting as Chelators and Biostimulants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi, S.; Schiavon, M.; Francioso, O. Chemical Structure and Biological Activity of Humic Substances Define Their Role as Plant Growth Promoters. Molecules 2021, 26, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibara, I.; Miwa, K. Strategies for Optimization of Mineral Nutrient Transport in Plants: Multilevel Regulation of Nutrient-Dependent Dynamics of Root Architecture and Transporter Activity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 2027–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Giehl, R.F.H.; von Wirén, N. Nutrient–Hormone Relations: Driving Root Plasticity in Plants. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Müller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. The Use of Biostimulants for Enhancing Nutrient Uptake. Adv. Agron. 2015, 130, 141–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoulati, A.; Ouahhoud, S.; Taibi, M.; Ezrari, S.; Mamri, S.; Merah, O.; Hakkou, A.; Addi, M.; Maleb, A.; Saalaoui, E. Harnessing Biostimulants for Sustainable Agriculture: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratore, C.; Espen, L.; Prinsi, B. Nitrogen Uptake in Plants: The Plasma Membrane Root Transport Systems from a Physiological and Proteomic Perspective. Plants 2021, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.-L.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; Qi, W.; Yang, K.-J.; Su, Y.-H. Function and Regulation of Ammonium Transporters in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Mao, C. Phosphate Uptake and Transport in Plants: An Elaborate Regulatory System. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragel, P.; Raddatz, N.; Leidi, E.O.; Quintero, F.J.; Pardo, J.M. Regulation of K+ Nutrition in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H. Sulfate Transport Systems in Plants: Functional Diversity and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Regulatory Coordination. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4075–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connorton, J.M.; Balk, J.; Rodríguez-Celma, J. Iron Homeostasis in Plants—A Brief Overview. Metallomics 2017, 9, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.H.; Usman, K.; Rizwan, M.; Al Jabri, H.; Alsafran, M. Functions and Strategies for Enhancing Zinc Availability in Plants for Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1033092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decros, G.; Baldet, P.; Beauvoit, B.; Stevens, R.; Flandin, A.; Colombié, S.; Gibon, Y.; Pétriacq, P. Get the Balance Right: ROS Homeostasis and Redox Signalling in Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanović, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Natić, M.; Kuča, K.; Jaćević, V. The Significance of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: A Concise Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 552969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N.; Saqib, S.; Ullah, F.; Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W. The Key Roles of ROS and RNS as a Signaling Molecule in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.; Schnug, E. Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidant Responses and Implications from a Microbial Modulation Perspective. Biology 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants through Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Signaling, and Scavenging during Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, H. Multiple Roles of MAP Kinases in Plant Signal Transduction. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.J.; Yun, B.-W.; Loake, G.J. Oxidative Burst and Cognate Redox Signalling Reported by Luciferase Imaging: Identification of a Signal Network That Functions Independently of Ethylene, SA and Me-JA but Is Dependent on MAPKK Activity. Plant J. 2000, 24, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D.; Sunkar, R. Drought and Salt Tolerance in Plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005, 24, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbriggen, M.D.; Carrillo, N.; Hajirezaei, M.-R. ROS Signaling in the Hypersensitive Response. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Mogami, J.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-Dependent and ABA-Independent Signaling in Response to Osmotic Stress in Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, F.; Takahashi, F.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Cellular Phosphorylation Signaling and Gene Expression in Drought Stress Responses: ABA-Dependent and ABA-Independent Regulatory Systems. Plants 2021, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huchzermeyer, B.; Menghani, E.; Khardia, P.; Shilu, A. Metabolic Pathway of Natural Antioxidants, Antioxidant Enzymes and ROS Providence. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Anjum, N.A.; Gill, R.; Yadav, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M.; Mishra, P.; Sabat, S.C.; Tuteja, N. Superoxide Dismutase—Mentor of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10375–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of Proline under Changing Environments. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic Acid-a Potential Oxidant Scavenger and Its Role in Plant Development and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Anee, T.I.; Fujita, M. Glutathione in Plants: Biosynthesis and Physiological Role in Environmental Stress Tolerance. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R. Physicochemical, Antioxidant Properties of Carotenoids and Its Optoelectronic and Interaction Studies with Chlorophyll Pigments. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.; Hussain, S.; Hussain, N.; Kakar, K.; Shah, J.; Zaidi, S.H.R.; Jan, M.; Zhang, K.; Khan, M.; Imtiaz, M. Tocopherol as Plant Protector: An Overview of Tocopherol Biosynthesis Enzymes and Their Role as Antioxidant and Signaling Molecules. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2022, 44, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Marenkova, T.V.; Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M. Antioxidants of Non-Enzymatic Nature: Their Function in Higher Plant Cells and the Ways of Boosting Their Biosynthesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, P.; Alseekh, S.; Ivanova, V.; Gechev, T. Biostimulant-Based Molecular Priming Improves Crop Quality and Enhances Yield of Raspberry and Strawberry Fruits. Metabolites 2024, 14, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanojia, A.; Lyall, R.; Sujeeth, N.; Alseekh, S.; Martínez-Rivas, F.J.; Fernie, A.R.; Gechev, T.S.; Petrov, V. Physiological and Molecular Insights into the Effect of a Seaweed Biostimulant on Enhancing Fruit Yield and Drought Tolerance in Tomato. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; Dong, Y. Seaweed-Based Biostimulants Improves Quality Traits, Postharvest Disorders, and Antioxidant Properties of Sweet Cherry Fruit and in Response to Gibberellic Acid Treatment. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, A.; Lops, F.; Disciglio, G.; Lopriore, G. Effects of Plant Biostimulants on Fruit Set, Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality Attributes of ‘Orange Rubis®’ Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Cultivar in Two Consecutive Years. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 239, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Khan, A.S.; Basra, S.M.A.; Malik, A.U. Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract, Potassium and Zinc Influence Yield and Fruit Quality of ‘Kinnow’ Mandarin. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppelsa, S.; Kelderer, M.; Casera, C.; Bassi, M.; Robatscher, P.; Andreotti, C. Use of Biostimulants for Organic Apple Production: Effects on Tree Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality at Harvest and during Storage. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet, J.M.; Campos, F.; Yenush, L. Editorial: Ion Homeostasis in Plant Stress and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 618273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Arias, D.; García-Machado, F.J.; Morales-Sierra, S.; García-García, A.L.; Herrera, A.J.; Valdés, F.; Luis, J.C.; Borges, A.A. A Beginner’s Guide to Osmoprotection by Biostimulants. Plants 2021, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbon, E.H.; Liberman, L.M. Beneficial Microbes Affect Endogenous Mechanisms Controlling Root Development. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL Boukhari, M.E.; Barakate, M.; Bouhia, Y.; Lyamlouli, K. Trends in Seaweed Extract Based Biostimulants: Manufacturing Process and Beneficial Effect on Soil-Plant Systems. Plants 2020, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickan, B.S.; Alsharmani, A.R.; Solaiman, Z.M.; Leopold, M.; Abbott, L.K. Plant-Dependent Soil Bacterial Responses Following Amendment with a Multispecies Microbial Biostimulant Compared to Rock Mineral and Chemical Fertilizers. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 550169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, T.; Mei, X.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Dong, C.; Jiang, G.; Lin, J.; Xu, Y.; et al. Bio-Organic Fertilizer Promotes Pear Yield by Shaping the Rhizosphere Microbiome Composition and Functions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e03572-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novello, G.; Bona, E.; Nasuelli, M.; Massa, N.; Sudiro, C.; Campana, D.C.; Gorrasi, S.; Hochart, M.L.; Altissimo, A.; Vuolo, F.; et al. The Impact of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria-Based Biostimulant Alone or in Combination with Commercial Inoculum on Tomato Native Rhizosphere Microbiota and Production: An Open-Field Trial. Biology 2024, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, P.; Qin, S. Responses of Soil Microbial Communities to a Short-Term Application of Seaweed Fertilizer Revealed by Deep Amplicon Sequencing. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 125, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, F.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Wu, M.; Zhan, J.; Chen, X.; Mao, Z. Effects of Seaweed Fertilizer on the Growth of Malus Hupehensis Rehd. Seedlings, Soil Enzyme Activities and Fungal Communities under Replant Condition. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2016, 75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Yang, L. Waste Seaweed Compost and Rhizosphere Bacteria Pseudomonas koreensis Promote Tomato Seedlings Growth by Benefiting Properties, Enzyme Activities and Rhizosphere Bacterial Community in Coastal Saline Soil of Yellow River Delta, China. Waste Manag. 2023, 172, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.-S.; He, X.-H.; Zou, Y.-N.; Liu, C.-Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y. Arbuscular Mycorrhizas Alter Root System Architecture of Citrus Tangerine through Regulating Metabolism of Endogenous Polyamines. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 68, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-S.; Huang, Y.-M.; Li, Y.; Nasrullah; He, X.-H. Contribution of Arbuscular Mycorrhizas to Glomalin-Related Soil Protein, Soil Organic Carbon and Aggregate Stability in Citrus Rhizosphere. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2014, 16, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, N.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Liao, H.; et al. Microbial and Organic Manure Fertilization Alters Rhizosphere Bacteria and Carotenoids of Citrus reticulata Blanco ‘Orah’. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, B.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Soppelsa, S.; Andreotti, C. Appraisal of Emerging Crop Management Opportunities in Fruit Trees, Grapevines and Berry Crops Facilitated by the Application of Biostimulants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 267, 109330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.S.; Sharma, S.; Rana, N.; Sharma, U. Sustainable Production through Biostimulants under Fruit Orchards. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Rana, N.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, U.; Almutairi, K.F.; Avila-Quezada, G.D.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Gudeta, K. Seaweed Extract as a Biostimulant Agent to Enhance the Fruit Growth, Yield, and Quality of Kiwifruit. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, I.Z.; Ahmed, M.; McSorley, G.; Dunlop, M.; Lucas, I.; Hu, Y. An Overview of Biostimulant Activity and Plant Responses under Abiotic and Biotic Stress Conditions. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2024, 4, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Chhabra, R. Biostimulants: Paving Way towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2024, 36, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rana, V.S.; Pawar, R.; Lakra, J.; Racchapannavar, V. Nanofertilizers for Sustainable Fruit Production: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1693–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, R.; Sousa, A.; Viencz, T.; Botelho, R. Fruit Set and Yield of Apple Trees cv. Gala Treated with Seaweed Extract of Ascophyllum nodosum and Thidiazuron. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2019, 41, e-072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydlik, P.; Zydlik, Z.; Kafkas, N.E. The Effect of the Foliar Application of Biostimulants in a Strawberry Field Plantation on the Yield and Quality of Fruit, and on the Content of Health-Beneficial Substances. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioli, T.; Mattner, S.W.; Hepworth, G.; McClintock, D.; McClinock, R. Effect of Seaweed Extract Application on Wine Grape Yield in Australia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureta Ovalle, A.; Atenas, C.; LarraÃ-n, P. Application of an Ecklonia maxima Seaweed Product at Two Different Timings Can Improve the Fruit Set and Yield in “Bing” Sweet Cherry Trees. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 28 February 2019; pp. 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- İmrak, B.; Kafkas, N.E.; Çömlekçioğlu, S.; Bilgin, Ö.F.; Gölcü, A.E.; Burgut, A.; Attar, Ş.H.; Küçükyumuk, C.; Küçükyumuk, Z. A Comparative Study of Dormex® and Biostimulant Effects on Dormancy Release, Productivity, and Quality in ‘Royal Tioga®’ Sweet Cherry Trees (Prunus avium L.). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.K.; Guo, B.; Leskovar, D.I. Biostimulants Alleviate Heat Stress in Organic Hydroponic Tomato Cultivation: A Sustainable Approach. HortScience 2025, 60, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommila, T.; Palonen, P. The Effect of Relative Humidity and the Use of Algae-Based Biostimulants on Fruit Set, Yield and Fruit Size of Arctic Bramble (Rubus arcticus). Agric. Food Sci. 2024, 33, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioli, T.; Villalta, O.N.; Hepworth, G.; Farnsworth, B.; Mattner, S.W. Effect of Seaweed Extract on Avocado Root Growth, Yield and Post-Harvest Quality in Far North Queensland, Australia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, A.; Frabboni, L.; Disciglio, G. Vegetative and Reproductive Responses Induced by Organo-Mineral Fertilizers on Young Trees of Almond cv. Tuono Grown in a Medium-High Density Plantation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira, M.; Romero, A.; del Castillo, N. Efficacy of Manvert Foliplus (Complete Biostimulant) in Two Hazelnut Cultivars in Tarragona, Spain. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 20 November 2018; pp. 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Souza-Da Costa, B.; Moreno-Simunovic, Y. Strategies for the Improvement of Fruit Set in Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Carménère’ through Different Foliar Biostimulants in Two Different Locations. Ciênc. Téc Vitiv 2018, 33, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.; Ashraf, M.; Tomar, C.S. Effect of Foliar Application of Nutrients and Biostimulant on Growth, Phenology and Yield Attributes of Pecan Nut cv. “Western Schley”. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Colavita, G.M.; Spera, N.; Blackhall, V.; Sepulveda, G.M. Effect of Seaweed Extract on Pear Fruit Quality and Yield. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 31 October 2011; pp. 601–607. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, D.; Rawat, M.; Kumar Mashkey, V.; Sharma, V.; Kundu, P. Estimation of Seaweed Extract and Micronutrient Potential to Improve Net Returns by Enhancing Yield Characters in Tomato Using Correlation Analysis. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 13, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.; Oliveira, I.; Ribeiro, C.; Vilela, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Gonçalves, B. Exploring the Role of Biostimulants in Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Fruit Quality Traits. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Jafari, A.; Shirmardi, M. The Effect of Seaweed Foliar Application on Yield and Quality of Apple cv. ‘Golden Delicious’. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, M.; González, A.; Romero, I. Effect of Seaweed Extracts (Ascophyllum nodosum) on Yield and Nut Quality in Hazelnut. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 31 October 2023; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Liang, D.; Xia, H.; Pang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Pu, C.; Wang, J.; Lv, X. Biostimulants Promote the Accumulation of Carbohydrates and Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins in ‘Yinhongli’ Plum. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1074965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Vázquez, I.; Calderón Zavala, G.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.D.L. Bioregulators and Biostimulants on Development, Growth and Fruit Yield of Blueberry cv. Biloxi. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2023, 46, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasingha, R.; Perera, A.; Baghalian, K.; Gerofotis, C. Amino Acid-Based Biostimulants and Microbial Biostimulants Promote the Growth, Yield and Resilience of Strawberries in Soilless Glasshouse Cultivation. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, N. Improvement in Plant Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality with Biostimulant Treatment in Organic Strawberry Cultivation. HortScience 2024, 59, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diánez, F.; Santos, M.; Carretero, F.; Marín, F. Biostimulant Activity of Trichoderma saturnisporum in Melon (Cucumis melo). HortScience 2018, 53, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, A.; Izzo, L.; Ciervo, A.; Ledenko, I.; Cepparulo, M.; Piscitelli, A.; Di Vaio, C. Optimizing Apricot Yield and Quality with Biostimulant Interventions: A Comprehensive Analysis. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rätsep, R.; Arus, L.; Kaldmäe, H.; Kahu, K. The Effect of Foliar Applications of Biostimulants on Leaf Chlorophyll and Fruit Quality in Organically Grown Black Currant (Ribes nigrum L.). In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 2 December 2021; pp. 721–726. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Payan, J.P. Response of “Banilejo” Mango to Foliar Applications of a Biostimulant Based on Free Amino Acids and Potassium. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 25 March 2015; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, A.; Samant, D.; Dash, D.K.; Dash, S.N.; Mishra, K.N. Influence of Ascophyllum nodosum Extract, Homobrassinolide and Triacontanol on Fruit Retention, Yield and Quality of Mango. J. Environ. Biol. 2021, 42, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, N.; Maghrebi, M.; Serio, G.; Gentile, C.; Bunea, V.V.; Vigliante, I.; Boitte, C.; Garabello, C.; Contartese, V.; Bertea, C.M.; et al. Seaweed and Yeast Extracts as Sustainable Phytostimulant to Boost Secondary Metabolism of Apricot Fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1455156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça Júnior, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Júnior, R.; Negreiros, A.; Bettini, M.; Freitas, C.; França, K.; Gomes, T. Seaweed Extract Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) on the Growth of Watermelon Plants. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2019, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaf, S.; Althaus, B.; Kunz, A.; Blanke, M. Reflective Materials and Biostimulants for Anthocyanin Synthesis and Colour Enhancement of Apple Fruits: Visualization, Abaxial and Adaxial Leaf Light Reflection. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 30 September 2022; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, K.; Selby-Pham, J. Strawberry Field Trial in Australia Demonstrates Improvements to Fruit Yield and Quality Control Conformity, from Application of Two Biostimulant Complexes. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2024, 53, 3124–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, R.P.; Distefano, M.; Steingass, C.B.; May, B.; Giuffrida, F.; Schweiggert, R.; Leonardi, C. Boosting Cherry Tomato Yield, Quality, and Mineral Profile through the Application of a Plant-Derived Biostimulant. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan-Algul, Y.; Mutlu-Durak, H.; Kutman, U.B.; Yildiz Kutman, B. Biostimulant Extracts Obtained from the Brown Seaweed Cystoseira barbata Enhance the Growth, Yield, Quality, and Nutraceutical Value of Soil-Grown Tomato. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petoumenou, D.G.; Patris, V.-E. Effects of Several Preharvest Canopy Applications on Yield and Quality of Table Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Crimson Seedless. Plants 2021, 10, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganugi, P.; Caffi, T.; Gabrielli, M.; Secomandi, E.; Fiorini, A.; Zhang, L.; Bellotti, G.; Puglisi, E.; Fittipaldi, M.B.; Asinari, F.; et al. A 3-Year Application of Different Mycorrhiza-Based Plant Biostimulants Distinctively Modulates Photosynthetic Performance, Leaf Metabolism, and Fruit Quality in Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1236199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-García, S.; Berríos, P.; Temnani, A.; Espinosa, P.J.; Monllor, C.; Pérez-Pastor, A. Combined Use of Biostimulation and Deficit Irrigation Improved the Fruit Quality in Table Grape. Plants 2025, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinescu, M.; Mazilu, I.; Chitu, E.; Plăiașu, F.; Paraschiv, M. Biostimulators Effect on Growth and Fruiting Processes of Two Sweet Cherry Cultivars Grafted on Gisela 3 Rootstock. Fruit Grow. Res. 2024, 40, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, B.; Brown, N.; Valdes, J.M.; Cardarelli, M.; Scognamiglio, P.; Mataffo, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Plant-Based Biostimulant as Sustainable Alternative to Synthetic Growth Regulators in Two Sweet Cherry Cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, B.B.; Vultaggio, L.; Iacuzzi, N.; La Bella, S.; De Pasquale, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Ntatsi, G.; Virga, G.; Sabatino, L. Iodine Biofortification and Seaweed Extract-Based Biostimulant Supply Interactively Drive the Yield, Quality, and Functional Traits in Strawberry Fruits. Plants 2023, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltaniband, V.; Brégard, A.; Gaudreau, L.; Dorais, M. Biostimulants Promote Plant Development, Crop Productivity, and Fruit Quality of Protected Strawberries. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di-Vaio, C.; Cirillo, A.; Cice, D.; El-Nakhel, C.; Rouphael, Y. Biostimulant Application Improves Yield Parameters and Accentuates Fruit Color of Annurca Apples. Agronomy 2021, 11, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattner, S.W.; Villalta, O.N.; McFarlane, D.J.; Islam, M.T.; Arioli, T.; Cahill, D.M. The Biostimulant Effect of an Extract from Durvillaea potatorum and Ascophyllum nodosum Is Associated with the Priming of Reactive Oxygen Species in Strawberry in South-Eastern Australia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1789–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppelsa, S.; Kelderer, M.; Testolin, R.; Zanotelli, D.; Andreotti, C. Effect of Biostimulants on Apple Quality at Harvest and after Storage. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.F.; Alharbi, A.R.; Abdelaziz, M.E.; Mosa, W.F.A. Salicylic Acid and Chitosan Effects on Fruit Quality When Applied to Fresh Strawberry or during Different Periods of Cold Storage. BioResources 2024, 19, 6057–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papantzikos, V.; Stournaras, V.; Mpeza, P.; Patakioutas, G. The Effect of Organic and Amino Acid Biostimulants on Actinidia deliciosa ‘Hayward’ Cultivation: Evaluation of Growth, Metabolism, and Kiwifruit Postharvest Performance. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogas, V.; Bravos, N.; Hussain, S.B. Preharvest Foliar Application of Si–Ca-Based Biostimulant Affects Postharvest Quality and Shelf-Life of Clementine Mandarin (Citrus clementina Hort. Ex Tan). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Petropoulos, S.A. Editorial for the Special Issue on Plant Biostimulants in Sustainable Horticulture and Agriculture: Development, Function, and Applications. Plants 2024, 13, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunitha, C.; Madhavi, M.; Sandhyarani, M.; Jasmitha, M.; Srinivasulu, B.; Kum, P.P. Role of Biostimulants in Fruit Crops: A Review. Pharma Innov. J. 2022, 11, 2041–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Cao, C.; Li, X.; Kan, Z. Precision Fertilization and Irrigation: Progress and Applications. AgriEngineering 2022, 4, 626–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leogrande, R.; El Chami, D.; Fumarola, G.; Di Carolo, M.; Piegari, G.; Elefante, M.; Perrelli, D.; Dongiovanni, C. Biostimulants for Resilient Agriculture: A Preliminary Assessment in Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassu, A.; Deidda, A.; Mercenaro, L.; Virgillito, B.; Gambella, F. Multisensor Analysis for Biostimulants Effect Detection in Sustainable Viticulture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.; Laudicina, V.A.; Vallone, M.; Catania, P. Application of Precision Agriculture for the Sustainable Management of Fertilization in Olive Groves. Agronomy 2023, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Pádua, L.; Sousa, J.J.; Fernandes-Silva, A. Advancements in Remote Sensing Imagery Applications for Precision Management in Olive Growing: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraju, M.; Chenniappan, P.; Ramalingam, K.; Pazhanivelan, S.; Kaliaperumal, R. Smart Farming: Internet of Things (IoT)-Based Sustainable Agriculture. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-Andreu, J.; Juárez, M.; Jordá, J.; Bermúdez, D. Improvement of Iron Uptake in Table Grape by Addition of Humic Substances. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morard, P.; Eyheraguibel, B.; Morard, M.; Silvestre, J. Direct Effects of Humic-like Substance on Growth, Water, and Mineral Nutrition of Various Species. J. Plant Nutr. 2010, 34, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, G.; Cellini, A.; Masia, A.; Simoni, A.; Francioso, O.; Gessa, C. In Vitro Treatment with a Low Molecular Weight Humic Acid Can Improve Growth and Mineral Uptake of Pear Plantlets during Acclimatization. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 20 December 2010; pp. 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-Andreu, J.; Juárez, M.; Jordá, J.; Bermúdez, D. Humic Substances and Amino Acids Improve Effectiveness of Chelate FeEDDHA in Lemon Trees. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Pan, L.; Zipori, I.; Mao, J.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Jing, Y.; Chen, H. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhanced the Growth, Phosphorus Uptake and Pht Expression of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Plantlets. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechri, B.; Tekaya, M.; Guesmi, A.; Hamadi, N.B.; Khezami, L.; Soltani, T.; Attia, F.; Chehab, H. Enhancing Olive Tree (Olea europaea) Rhizosphere Dynamics: Co-Inoculation Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plant Growth- Promoting Rhizobacteria in Field Experiments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, J.M.; Madejón, E.; Madejón, P.; Cabrera, F. The Response of Wild Olive to the Addition of a Fulvic Acid-Rich Amendment to Soils Polluted by Trace Elements (SW Spain). J. Arid Environ. 2005, 63, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, G.; Celano, G.; Dichio, B.; Xiloyannis, C. Effects of Soil-Protecting Agricultural Practices on Soil Organic Carbon and Productivity in Fruit Tree Orchards. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 21, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Rouphael, Y. Foliar Applications of Protein Hydrolysate, Plant and Seaweed Extracts Increase Yield but Differentially Modulate Fruit Quality of Greenhouse Tomato. HortScience 2017, 52, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaretti, A.; Montegiove, N.; Calzoni, E.; Leonardi, L.; Emiliani, C. Protein Hydrolysates: From Agricultural Waste Biomasses to High Added-Value Products (Minireview). AgroLife Sci. J. 2020, 9, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- García-García, A.L.; García-Machado, F.J.; Borges, A.A.; Morales-Sierra, S.; Boto, A.; Jiménez-Arias, D. Pure Organic Active Compounds against Abiotic Stress: A Biostimulant Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 575829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikula, K.; Konieczka, M.; Taf, R.; Skrzypczak, D.; Izydorczyk, G.; Moustakas, K.; Kułażyński, M.; Chojnacka, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Tannery Waste as a Renewable Source of Nitrogen for Production of Multicomponent Fertilizers with Biostimulating Properties. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8759–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.; Pal, P.; Singh, A.K. Chapter 4—Role of Protein Hydrolysates in Plants Growth and Development. In Biostimulants in Plant Protection and Performance; Husen, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 61–72. ISBN 978-0-443-15884-1. [Google Scholar]

- Arancon, N.Q.; Edwards, C.A.; Lee, S.; Byrne, R. Effects of Humic Acids from Vermicomposts on Plant Growth. ICSZ 2006, 42, S65–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Domínguez, J. The Use of Vermicompost in Sustainable Agriculture: Impact on Plant Growth and Soil Fertility. In Soil Nutrients; Nova Science Pub Inc: Hauppauge, New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-61324-785-3. [Google Scholar]

- Caixeta, L.; Neves, R.; Lima, C.; Zandonadi, D. Vermicompost Biostimulants: Nutrients and Auxin for Root Growth. In Proceedings of the 16 World Fertilizer Congress of CIECA, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1 January 2014; pp. 256–258. [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli, F.; Carullo, D.; Farris, S.; Ferrante, A.; Bacenetti, J.; Ventura, V.; Frisio, D.; Borin, S. Food Waste-Derived Biomaterials Enriched by Biostimulant Agents for Sustainable Horticultural Practices: A Possible Circular Solution. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 928970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Payan, J.P.; Stall, W. Papaya (Carica papaya) Response to Foliar Treatments with Organic Complexes of Peptides and Amino Acids. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 2003, 116, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Viti, R.; Bartolini, S.; Vitagliano, C. Growth Regulators on Pollen Germination in Olive. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, 1 December 1990; pp. 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Payan, J.P.; Stall, W. Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis) Transplant Production Is Affected by Selected Biostimulants. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 2004, 117, 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gurav, R.G.; Jadhav, J.P. A Novel Source of Biofertilizer from Feather Biomass for Banana Cultivation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4532–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachhab, N.; Sanzani, S.M.; Adrian, M.; Chiltz, A.; Balacey, S.; Boselli, M.; Ippolito, A.; Poinssot, B. Soybean and Casein Hydrolysates Induce Grapevine Immune Responses and Resistance against Plasmopara viticolai. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boselli, M.; Bahouaoui, M.A.; Lachhab, N.; Sanzani, S.M.; Ferrara, G.; Ippolito, A. Protein Hydrolysates Effects on Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L., cv. Corvina) Performance and Water Stress Tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 258, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.; Naira, A.; Moieza, A. Effect of Plant Biostimulants on Fruit Cracking and Quality Attributes of Pomegranate cv. Kandhari Kabuli. Sci. Res. Essays 2013, 8, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Oliveira, I.; Queirós, F.; Ribeiro, C.; Ferreira, L.; Luzio, A.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Preharvest Application of Seaweed Based Biostimulant Reduced Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Cracking. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 29, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saa, S.; Olivos-Del Rio, A.; Castro, S.; Brown, P.H. Foliar Application of Microbial and Plant Based Biostimulants Increases Growth and Potassium Uptake in Almond (Prunus dulcis [Mill.] D. A. Webb). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Queirós, F.; Ferreira, H.; Morais, M.C.; Afonso, S.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Foliar Application of Calcium and Growth Regulators Modulate Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Tree Performance. Plants 2020, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Santos, M.; Glińska, S.; Gapińska, M.; Matos, M.; Carnide, V.; Schouten, R.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Effects of Exogenous Compound Sprays on Cherry Cracking: Skin Properties and Gene Expression. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 2911–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Gonçalves, B.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I. The Role of Biostimulants as Alleviators of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Grapevine: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.; Afonso, S.; Pinto, L.; Vieira, S.; Vilela, A.; Silva, A.P. Preliminary Evaluation of the Application of Algae-Based Biostimulants on Almond. Plants 2022, 11, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serapicos, M.; Afonso, S.; Gonçalves, B.; Silva, A.P. Exogenous Application of Glycine Betaine on Sweet Cherry Tree (Prunus avium L.): Effects on Tree Physiology and Leaf Properties. Plants 2022, 11, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, S.; Oliveira, I.; Guedes, F.; Meyer, A.S.; Gonçalves, B. Glycine Betaine and Seaweed-Based Biostimulants Improved Leaf Water Status and Enhanced Photosynthetic Activity in Sweet Cherry Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1467376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Correia, S.; Baltazar, M.; Pereira, S.; Ferreira, H.; Bragança, R.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I.; Gonçalves, B. Foliar Application of Nettle and Japanese Knotweed Extracts on Vitis vinifera: Consequences for Plant Physiology, Biochemical Parameters, and Yield. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; De Lorenzis, G.; Ricciardi, V.; Baltazar, M.; Pereira, S.; Correia, S.; Ferreira, H.; Alves, F.; Cortez, I.; Gonçalves, B.; et al. Exploring Seaweed and Glycine Betaine Biostimulants for Enhanced Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Properties, and Gene Expression of Vitis vinifera cv. “Touriga Franca” Berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Nanda, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B.N.; Mukherjee, A. Seaweed Extracts: Enhancing Plant Resilience to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1457500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovetto, E.I.; La Spada, F.; Aloi, F.; Riolo, M.; Pane, A.; Garbelotto, M.; Cacciola, S.O. Green Solutions and New Technologies for Sustainable Management of Fungus and Oomycete Diseases in the Citrus Fruit Supply Chain. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 106, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.S.S.; Fleming, C.; Selby, C.; Rao, J.R.; Martin, T. Plant Biostimulants: A Review on the Processing of Macroalgae and Use of Extracts for Crop Management to Reduce Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]